Abstract

Background & objectives:

High-altitude pulmonary oedema (HAPE) continues to challenge the healthcare providers at remote, resource-constrained settings. High-altitude terrain itself precludes convenience of resources. This study was conducted to evaluate the rise in peripheral capillary saturation of oxygen (SpO2) by the use of a partial rebreathing mask (PRM) in comparison to Hudson's mask among patients with HAPE.

Methods:

This was a single-centre, randomized crossover study to determine the efficiency of PRM in comparison to Hudson's mask. A total of 88 patients with HAPE referred to a secondary healthcare facility at an altitude of 11,500 feet from January to October 2013 were studied. A crossover after adequate wash-out on both modalities was conducted for first two days of hospital admission. All patients with HAPE were managed with bed rest and stand-alone oxygen supplementation with no adjuvant pharmacotherapy.

Results:

The mean SpO2 on ambient air on arrival was 66.92±10.8 per cent for all patients with HAPE. Higher SpO2 values were achieved with PRM in comparison to Hudson's mask on day one (86.08±5.15 vs. 77.23±9.09%) and day two (89.94±2.96 vs. 83.39±5.93%). The difference was more pronounced on day one as compared to day two.

Interpretation & conclusions:

Mean SpO2 values were found to be significantly higher among HAPE patients using PRM compared to those on Hudson's mask. Further studies to understand the translation of this incremental response in SpO2 to clinical benefits (recovery times, mortality rates and hospital stay) need to be undertaken.

Keywords: Environmental illness, high-altitude pulmonary oedema, occupational health, oxygen delivery systems, oxygen therapy

With increasing tourism and military deployment worldwide in high-altitude areas (HAAs), the incidence of high-altitude illnesses (HAIs) is increasing. Also contributing to this increased rate is the faster transportation by air to HAA, decreasing the period of acclimatization. Hypobaric hypoxia is the underlying pathophysiological crux for all HAIs1. The management of these diseases revolves around descent from altitude and/or effective oxygen supplementation therapy2. While numerous oxygen delivery systems are used in clinical practice, the efficacy of each system is dictated by the delivered fraction of oxygen in inspired air (FiO2). Devices which provide high FiO2 achieve higher blood oxygenation.

A literature search showed several reviews on various oxygen delivery systems in both physiological and pathological conditions3,4,5,6. Two groups of investigators also studied the effect of oxygen demand systems in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases7,8. No similar study has been found specifically for the treatment of HAI. Therefore, this study was undertaken to determine the rise in peripheral capillary saturation of oxygen (SpO2) by using a partial rebreathing mask (PRM) in comparison to Hudson's mask among patients of high-altitude pulmonary oedema (HAPE).

Material & Methods

A single-centre, interventional randomized crossover study design was formulated to determine the efficiency of PRM in comparison to Hudson's mask in patients with HAPE. This study was conducted at a secondary-level General Hospital situated in Leh, India, which is at an elevation of 3500 m above the sea level. The approval was taken from the 14 Corps Medical Institutional Ethics Committee.

A total of 104 patients were screened during a period of 10 months between January and October 2013. The Lake Louise criteria9 for HAPE, i.e. the presence of at least two pulmonary signs among wheezing or rales in at least one lung field, tachycardia, central cyanosis, tachypnoea, and any two pulmonary symptoms among cough, weakness or decreased exercise performance, chest tightness or congestion, dyspnoea at rest, were used to screen patients. All consecutive patients with positive chest X-ray (CXR) for HAPE during the study period were included. Uniformity for clinical severity was maintained in all patients using scoring criteria of Vock et al10. Other inclusion criteria followed were previously healthy subjects aged >18 yr with no known co-morbidities and willingness to participate.

Exclusion criteria were highlanders with HAPE, fresh diagnosis of other co-morbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus), simultaneous presence of high-altitude cerebral oedema (HACE) and withdrawal of informed consent.

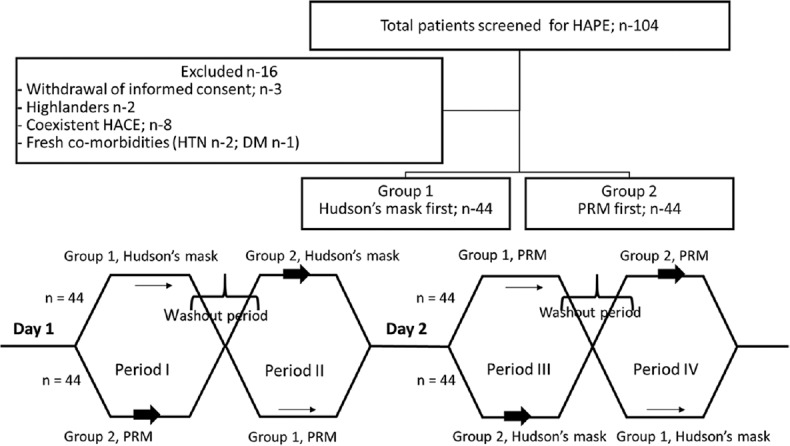

Of the total number of patients screened, 88 patients with HAPE were included in the study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Consort diagram and crossover design of the study. HAPE, high-altitude pulmonary oedema; HACE, high-altitude cerebral oedema; PRM, partial rebreathing mask; HTN, hypertension; DM, diabetes mellitus.

Study protocol: The patients were allocated to two interventional groups based on the first used oxygen delivery system (group 1 Hudson's mask first and group 2 PRM first). Patients in each interventional group were crossed over after an adequate wash-out period. Patients were selected by alphabetic randomization, in which all individuals with given first names starting from A to M were randomized to group 1 and N to Z were randomized to group 2. Four hourly clinical monitoring by vital parameters (pulse, blood pressure, SpO2) was done in intensive care centre settings. Any patient with clinical deterioration in either interventional group was treated as per clinical status.

Day one: First, peripheral capillary saturation of oxygen (SpO2) on ambient air at admission was recorded for all patients. Group 1 patients were treated with oxygen delivered via Hudson's mask and group 2 patients with PRM. After four hours of initial therapy, the patients were switched to the other modality of oxygen delivery for the next four hours, after either a wash-out interval of 30 min or a decline in SpO2 levels, whichever was earlier. Finally, patients from group 1 were continued on Hudson's mask till the next day and group 2 patients with PRM.

Day two: On the next day of treatment, baseline SpO2 levels were taken after either a wash-out period of 30 min in which no oxygen supplementation was given or a decline in SpO2 levels, whichever was earlier. The sequence of delivery modalities was then switched. Group 1 patients were now started with PRM and group 2 with Hudson's mask. Each system was followed by the other with intervening wash-out period as described earlier. For every treatment modality, SpO2 recorded at the end of four hours of continuous use of either Hudson's mask or PRM was used for statistical analysis (Fig. 1).

Statistical analysis: Statistical analysis was carried out using R Core Team (2017). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing11. Bland-Altman plot was drawn to compare oxygen delivery through the PRM and Hudson's mask. For analysis, a P≤0.05 was set to be statistically significant.

Results & Discussion

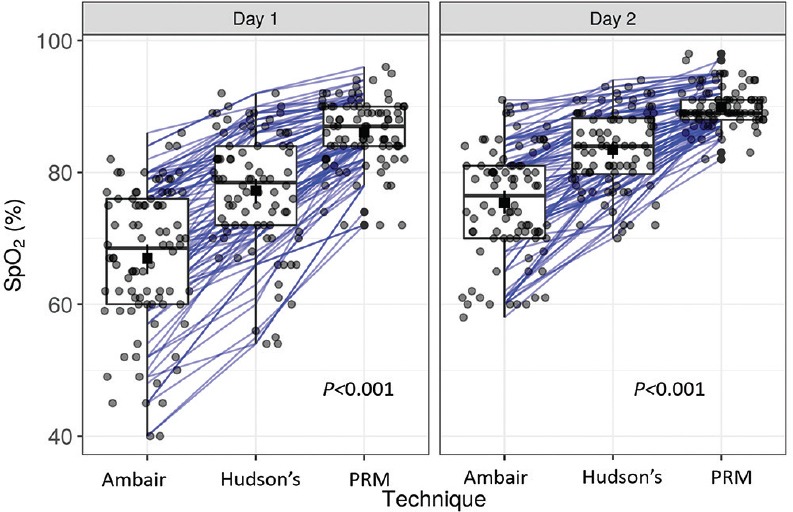

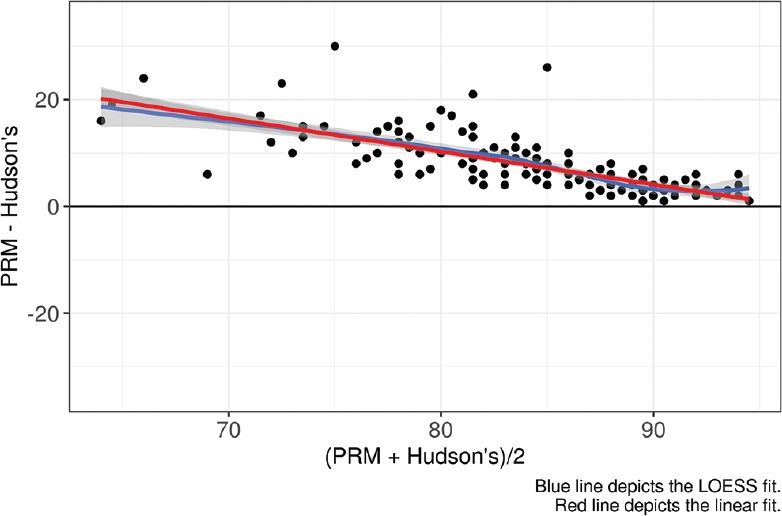

The mean SpO2 on ambient air, on arrival, was 66.92±10.8 per cent for all patients with HAPE. Mean SpO2 values were found to be higher in patients using PRM on both days one and two, as shown in the Table. Boxer plots for mean SpO2 levels are as shown in Fig. 2. Bland-Altman analysis (Fig. 3)showed that PRM had greater SpO2 across all ranges of SpO2 values. The difference between PRM and Hudson's mask at average SpO2 of 80 per cent was 10.27 per cent [95% confidence interval (CI): 9.62-10.92]. With each one per cent increase in average SpO2, the difference decreases by 0.62 per cent (95% CI: −0.71 to −0.53%). The difference decreased at higher SpO2 concentrations.

Table.

Mean SpO2 on days one and two using different oxygen delivery systems

| Oxygen delivery system | SpO2 (%), mean±SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Day one | Day two | |

| Ambient air | 66.92±10.8 | 75.41±8.45 |

| Hudson’s mask | 77.23±9.09 | 83.39±5.93 |

| PRM | 86.08±5.15 | 89.94±2.96 |

SD, standard deviation; PRM, partial rebreathing mask; SpO2, peripheral capillary saturation of oxygen

Fig. 2.

Boxer plot with different oxygen delivery systems on days one and two. Square dots with bars, Mean with 95% confidence interval. SpO2, Peripheral capillary oxygen saturation; Ambair, ambient air; Hudson's, Hudson's mask; PRM, partial rebreathing mask.

Fig. 3.

Bland-Altman analysis for Hudson's mask versus partial rebreathing mask (PRM).

The partial pressure of oxygen (PO2) is the driving force for the diffusion of oxygen molecules from inspired air to alveolar air, then into the blood and ultimately into the cells and mitochondria. This is known as the oxygen cascade12. The PO2 in inspired air (PIO2) is given by the equation13:

PIO2= FiO2× (Pb − 47 mmHg),

where Pb is barometric pressure, and 47 mmHg is vapour pressure of H2O at 37°C.

The proportion of air comprised of oxygen (FiO2, 20.94%) remains constant at the highest altitude up to upper troposphere. The alveolar vapour pressure of water is also constant at 47 mmHg. Hence, the PIO2 and thus the oxygen cascade are directly affected by barometric pressure (Pb)12.

Pb diminishes exponentially with increasing altitude. Other variables which decrease Pb include lower temperature, inclement weather during winter and high latitude. Although the effect of these variables upon Pb is not nearly as significant as altitude, it becomes physiologically substantial at elevations over approximately 2800 m (as in our scenario throughout Leh region)14. Therefore, diminished PIO2 at high altitude is the direct result of low Pb. As PIO2 decreases, so does the partial pressure of alveolar oxygen (PAO2), arterial PO2 (PaO2) and SpO2 resulting in tissue hypoxia. This form of hypoxia is hypobaric hypoxia, and represents the initial cause of HAI.

Treatment modalities for HAI in general and HAPE in particular, have seen a sea change in the last decade. While drugs such as calcium channel blockers and diuretics were the chief weapon of the treatment arsenal, more and more research is now pointing to oxygen therapy as being the superior alternative. A randomized controlled trial suggested that HAPE could be adequately treated by oxygen therapy and bed-rest alone, in situations where descent was not possible and pharmacological agents showed no added advantage15.

The Hudson's mask is a simple facemask that has been described as a variable performance oxygen delivery system16. Concentration of up to 60 per cent can be achieved with moderate oxygen flow rates (6-10 l/min). These are most commonly used due to wide availability and ease of use. The use of non-rebreather masks to achieve greater FiO2 has also been studied17,18. A low-flow device, the partial rebreather mask, can deliver 40-70 per cent oxygen at flow rates of 6-10 l/min19. The oxygen flow should keep the reservoir bag at least one-third to one-half full on inspiration20. Our study showed superior results with a PRM which could be explained by the delivery of higher FiO2 due to the use of a reservoir.

Our study was limited by the inclusion of only male patients, and therefore, the data cannot be generalized to females. Clinical outcomes (recovery times, days of hospitalization and mortality) were also not correlated with the improved SpO2 levels.

In conclusion, our study showed the PRM to be consistently superior to conventional devices such as the Hudson's mask, in the delivery of higher flow rates and maintenance of higher SpO2 for quicker clinical recovery. The SpO2 for patients on PRM was consistently higher on day one and two as compared to those on Hudson's mask.

Footnotes

Financial support & sponsorship: None.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.West JB. High-altitude medicine. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:1229–37. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201207-1323CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stream JO, Grissom CK. Update on high-altitude pulmonary edema: Pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment. Wilderness Environ Med. 2008;19:293–303. doi: 10.1580/07-WEME-REV-173.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bethune DW, Collis JM. An evaluation of oxygen therapy equipment. Experimental study of various devices on the human subject. Thorax. 1967;22:221–5. doi: 10.1136/thx.22.3.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brotfain E, Zlotnik A, Schwartz A, Frenkel A, Koyfman L, Gruenbaum SE, et al. Comparison of the effectiveness of high flow nasal oxygen cannula vs. standard non-rebreather oxygen face mask in post-extubation intensive care unit patients. Isr Med Assoc J. 2014;16:718–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fairfield JE, Goroszeniuk T, Tully AM, Adams AP. Oxygen delivery systems – A comparison of two devices. Anaesthesia. 1991;46:135–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1991.tb09360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horio Y, Takihara T, Niimi K, Komatsu M, Sato M, Tanaka J, et al. High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy for acute exacerbation of interstitial pneumonia: A case series. Respir Investig. 2016;54:125–9. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braun SR, Spratt G, Scott GC, Ellersieck M. Comparison of six oxygen delivery systems for COPD patients at rest and during exercise. Chest. 1992;102:694–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.102.3.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuhrman C, Chouaid C, Herigault R, Housset B, Adnot S. Comparison of four demand oxygen delivery systems at rest and during exercise for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2004;98:938–44. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hackett P, Oelz O. The Lake Louise consensus on the quantification of altitude illness. Burlington, YT: QueenCity Printers Inc; 1992. pp. 327–30. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vock P, Brutsche MH, Nanzer A, Bärtsch P. Variable radiomorphologic data of high altitude pulmonary edema. Features from 60 patients. Chest. 1991;100:1306–11. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.5.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: [Google Scholar]

- 12.Treacher DF, Leach RM. Oxygen transport-1. Basic principles. Br Med J. 1998;317:1302–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7168.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hess D, MacIntyre NR, Galvin WF, Mishoe SC. High-altitude pulmonary edema in the children and young adults of leadville, colorado. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:1269–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197712082972309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scoggin CH, Hyers TM, Reeves JT, Grover RF. High-altitude pulmonary edema in the children and young adults of leadville, colorado. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:1269–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197712082972309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yanamandra U, Nair V, Singh S, Gupta A, Mulajkar D, Yanamandra S, et al. Managing high-altitude pulmonary edema with oxygen alone: Results of a randomized controlled trial. High Alt Med Biol. 2016;17:294–9. doi: 10.1089/ham.2015.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bersten A. Oh's intensive care manual. 7th ed. UK: Butterworth Heinemann Elsevier; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curran D, Bennett A. Non-rebreathing masks. Am J Emerg Med. 1987;5:350. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(87)90375-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jevon P. Respiratory procedures. Part 1 – Use of a non-rebreathing oxygen mask. Nurs Times. 2007;103:26–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bateman NT, Leach RM. ABC of oxygen. Acute oxygen therapy. BMJ. 1998;317:798–801. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7161.798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kallstrom TJ American Association for Respiratory Care (AARC) AARC clinical practice guideline: Oxygen therapy for adults in the acute care facility-2002 revision & update. Respir Care. 2002;47:717–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]