Abstract

Scrub typhus is largely ignored in India particularly during outbreaks of viral fever. The disease course is often complicated leading to fatalities in the absence of treatment. However, if diagnosed early and a specific treatment is initiated, the cure rate is high. We report here five cases of scrub typhus to highlight the fact that high clinical suspicion for such a deadly disease is an absolute necessity.

Keywords: Acute febrile illness, chikungunya, dengue, mortality, scrub typhus

Scrub typhus is an acute undifferentiated febrile illness caused by the bacterium Orientia tsutsugamushi, which belongs to the family Rickettsiaceae. It is transmitted by the larval stage of trombiculid mite (chigger)1. The clinical presentation often mimics other common febrile illnesses such as dengue virus infection and chikungunya. This disease is grossly under-reported and under-diagnosed owing to the misconception that scrub typhus is only a concern in heavily forested areas. Associated complications in severe cases include hepatitis, myocarditis, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), multiorgan dysfunction syndrome (MODS), disseminated intravascular clotting with shock and several neurological manifestations2,3. Scrub typhus if not treated early may have a mortality rate of up to 30-35 per cent4,5,6. We report here five cases of scrub typhus with fatal outcome due to multiorgan dysfunction presented to the department of Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee and written informed consent was taken from all patients.

In September 2016, a 21 yr old male patient, resident of Delhi (State in central India), with no prior co-morbidities presented with fever for 10 days and progressive shortness of breath and altered sensorium for two days. It was followed by the second case of a 16 yr old female patient, resident of Uttarakhand (State in north India), who presented with a history of fever, altered sensorium, shortness of breath, arthralgia and decreased urine output for 10 days. The third case was a 30 yr old female patient, resident of Bihar (State in east India), with a history of fever associated with vomiting and pain in the abdomen for 11 days. The series of fatalities continued with two more cases in November 2016. A 24 yr old male patient, resident of Delhi, with no prior co-morbidities presented with a history of fever associated with headache, myalgia and generalized swelling of the body for eight days. In the same month, a 62 yr old female patient, resident of Haryana (State in north India), was referred from a private hospital with a history of fever for six days. She also had abdominal pain, dyspnoea and altered sensorium for one day. All these five patients succumbed to multiple organ dysfunctions. The clinical features and routine laboratory investigations of all these five patients are given in the Table.

Table.

Clinical, haematological, biochemical and microbiological details of the five cases of scrub typhus

| Clinical/laboratory parameters | Reference range | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complications | - | ARDS, shock, myocarditis | AKI, ARDS | Transaminitis, AKI | AKI, ARDS | ARDS, AKI |

| Treatment | - | Ceftriaxone, artesunate, doxycycline | Ceftriaxone, azithromycin, doxycycline | Ceftriaxone, piperacillin-tazobactam, doxycycline | Levofloxacin, cefoperazone-sulbactam, doxycycline | Ceftriaxone, amikacin, doxycycline |

| Death (day post-admission) | - | Second day | Third day | Fifth day | Third day | Second day |

| Haemoglobin (g/dl) | 12.0-16.0 | 11.2 | 4.9 | 7.9 | 9.9 | 9.8 |

| TLC (per µl) | 4500-11,000 | 9800 | 3500 | 14,700 | 11,600 | 9800 |

| Platelet count (per µl) | 150,000-400,000 | 26,000 | 20,000 | 30,000 | 40,000 | 8000 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.3-1.0 | 0.4 | 2.4 | 5.3 | 4.4 | 2.5 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.0-0.4 | - | - | - | 3.7 | 3.5 |

| ALP (IU/l) | 30-100 | 296 | 403 | 396 | 449 | 226 |

| ALT (IU/l) | 0-50 | 70 | 95 | 108 | 277 | 966 |

| AST (IU/l) | 0-50 | 149 | 315 | 290 | 483 | 2160 |

| Total protein (g/dl) | 6.0-8 | - | 4.6 | 5.1 | 5.6 | - |

| Urea (mg/dl) | 20-50 | 147 | 93 | 256 | 169 | 165 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | <1.2 | 5.7 | 3.9 | 7.7 | 4.7 | 4.1 |

| Sodium (mmol/l) | 135-145 | 145 | 113 | 135 | 143 | 137.1 |

| Potassium (mmol/l) | 3.4-5 | 5.7 | 3.4 | 3.95 | 5.5 | 4.81 |

| CRP (mg/l) | <8.0 | - | - | - | 129.22 | 100 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 0-25 | - | - | - | 40 | 55 |

| IFA titre‡ | ||||||

| Kato | ≥64 | 512 | 512 | 512 | 512 | 256 |

| Karp | ≥64 | 512 | 256 | 256 | 256 | 256 |

| Boryong | ≥64 | 512 | 512 | 512 | 512 | 256 |

| Gilliam | ≥64 | 512 | 256 | 512 | 512 | 256 |

| IgM ELISA$ (OD) | ≥0.89 | 2.89 | 2.85 | 1.28 | 3.12 | 1.512 |

| RFA IgM | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| Nested PCR (56 kDa)* | 483 bp | + | - | + | + | - |

| qPCR (47 kDa)* | 118 bp | + | - | + | + | - |

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; AKI, acute kidney injury; TLC, total leucocyte count; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; IFA, immunofluorescent antibody assay; OD, optical density; RFA, rapid flow assay

Since these patients presented during the ongoing chikungunya outbreak in Delhi, serological tests were done first to rule out chikungunya and dengue followed by leptospirosis, malaria, enteric fever, hepatitis and scrub typhus to rule out other differentials. Scrub typhus IgM rapid flow assay (InBios International, Inc., Washington, USA) and ELISA (InBios) were positive for all five patients. This was confirmed by indirect immunofluorescent antibody assay (IFA) (Fuller Laboratories, Fullerton, USA) which is considered gold standard. Predetermined cut-offs for ELISA and IFA in New Delhi were used7. The whole blood sample was subjected to nested PCR targeting 56 kDa antigen and real-time PCR assay (qPCR) targeting 47 kDa antigen. DNA was extracted from 200 μl of whole blood using the QIAmp blood minikit (Qiagen GmBh, Germany). DNA amplification was performed by nested format and qPCR using conditions described by Furuya et al8 and Jiang et al9, respectively.

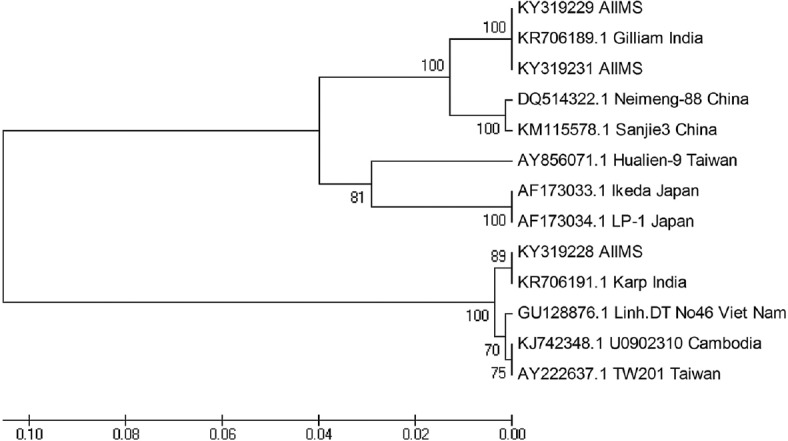

Of these five patients, three were found to be positive by both nested PCR targeting 56 kDa antigen and real-time PCR targeting 47 kDa antigen (Table). PCR product was sequenced and deposited in NCBI GenBank under accession numbers - KY319228, KY319229 and KY319231. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool analysis (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) revealed homology with O. tsutsugamushi. Phylogenetic tree was drawn, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the tree. The evolutionary history was inferred using the UPGMA method10. The optimal tree was constructed with the sum of branch length=0.29878659. The evolutionary distances were computed using the maximum composite likelihood method11. Phylogenetic analyses involved 13 nucleotide sequences and were conducted in Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis software, version 4.0 (MEGA4, USA) (https://www.megasoftware.net/mega4/). Of the three sequences, two were clustered close (100%) to Gilliam and one isolate (89%) with Karp genotype (Figure).

Figure.

Phylogenetic analysis of Orientia tsutsugamushi clinical isolates. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree.

There have been concerns in the recent times regarding the specificity of IFA and the current gold standard for diagnosis of scrub typhus. The molecular assays like PCR have good specificity, but these are usually positive only in the first week of disease during the period of rickettsemia. The sensitivity of PCR beyond the first week of illness is low. Most of the patients presented late to the hospital explaining the negativity of PCR in two patients. Although Lim et al12 described scrub typhus infection criteria (STIC) using a combination of culture, PCR assays and IFA IgM for diagnosis of scrub typhus, yet its applicability and feasibility in resource-limited setting remained questionable. Three of our five patients met the STIC criteria. The other two patients could not meet the criteria because we could not perform all the recommended tests or dilutions due to feasibility issues. Besides, all five patients met the Indian criteria for diagnosis of scrub typhus13.

There have been reports of emergence/re-emergence of scrub typhus in locations where it was previously unknown14. Although scrub typhus is known to be endemic in India, the suspicion and identification of this disease have been neglected for long. Similar seasonal prevalence (post-monsoon period) of other febrile diseases and overlapping clinical manifestations also contribute to misdiagnosis. During 2016, there was an upsurge in the total number of cases where scrub typhus was suspected. A total of 317 samples were tested between August and November 2016 at the time of ongoing chikungunya outbreak15, of which 34 were found to be positive by IFA and ELISA (13 PCR positive) including these five fatal cases.

The mortality due to scrub typhus depends on the geographical location, pathogenic strain involved and various host factors such as age, immune status and the co-morbidities. In a systemic review by Taylor et al16, higher mortality was seen in patients over 30 yr of age and was highest among patients over 60 yr. The presence of specific clinical symptoms, namely myocarditis, haemorrhagic, neurological or pulmonary symptoms may also contribute to the higher mortality among patients. Among the cases we report here, it was worth noting that four patients were under 30 yr of age and none of them had the presence of eschar, but all had multiple complications (cardiological, pulmonary or neurological), which might have contributed to their unfortunate outcome. Doxycycline is universally the drug of choice for treatment of scrub typhus irrespective of the day of presentation. However, it might be ineffective if the treatment is delayed. In our case, all patients were referred late and were already in MODS which could not be reversed inspite of initiation of effective treatment.

In conclusion, scrub typhus need to be included in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with acute febrile illness even in the absence of characteristic eschar. High index of clinical suspicion should be kept, particularly during viral outbreaks where the diagnosis can be missed. Timely diagnosis and appropriate management can prevent fatal outcomes associated with scrub typhus.

Acknowledgment

Authors acknowledge Dr S.K. Sharma, former Head, department of Medicine and other faculty members and residents of the department of Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, for providing valuable information for this study.

Footnotes

Financial support & sponsorship: None.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Pai R, Chaudhry R, Gupta N, Sryma PB, Biswas A, Dey AB. Tricky typhus ticks two: A report of two sisters from North India presenting with acute respiratory distress syndrome due to scrub typhus. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2016;34:244–6. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.176847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chrispal A, Boorugu H, Gopinath KG, Chandy S, Prakash JA, Thomas EM, et al. Acute undifferentiated febrile illness in adult hospitalized patients: The disease spectrum and diagnostic predictors – An experience from a tertiary care hospital in South India. Trop Doct. 2010;40:230–4. doi: 10.1258/td.2010.100132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varghese GM, Trowbridge P, Janardhanan J, Thomas K, Peter JV, Mathews P, et al. Clinical profile and improving mortality trend of scrub typhus in South India. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;23:39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. WHO recommended surveillance standards. 2nd ed. Geneva: WHO; 2012. No. WHO/CDS/CSR/ISR/99.2. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffith M, Peter JV, Karthik G, Ramakrishna K, Prakash JA, Kalki RC, et al. Profile of organ dysfunction and predictors of mortality in severe scrub typhus infection requiring intensive care admission. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2014;18:497–502. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.138145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson CN, Blacksell SD, Paris DH, Arjyal A, Karkey A, Dongol S, et al. Undifferentiated febrile illness in Kathmandu, Nepal. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;92:875–8. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta N, Chaudhry R, Thakur CK. Determination of cutoff of ELISA and immunofluorescence assay for scrub typhus. J Glob Infect Dis. 2016;8:97–9. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.188584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furuya Y, Yoshida Y, Katayama T, Yamamoto S, Kawamura A., Jr Serotype-specific amplification of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi DNA by nested polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1637–40. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.6.1637-1640.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang J, Chan TC, Temenak JJ, Dasch GA, Ching WM, Richards AL. Development of a quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction assay specific for Orientia tsutsugamushi. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;70:351–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sneath PHA, Sokal RR. Numerical Taxonomy: The Principles and Practice of Numerical Classification. San Francisco: WF Freeman & Co; 1973. 573 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tamura K, Nei M, Kumar S. Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11030–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404206101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim C, Paris DH, Blacksell SD, Laongnualpanich A, Kantipong P, Chierakul W, et al. How to determine the accuracy of an alternative diagnostic test when it is actually better than the reference tests: A re-evaluation of diagnostic tests for scrub typhus using Bayesian LCMs. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0114930. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rahi M, Gupte MD, Bhargava A, Varghese GM, Arora R. DHR-ICMR guidelines for diagnosis & management of rickettsial diseases in India. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141:417–22. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.159279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker DH. Scrub typhus – Scientific neglect, ever-widening impact. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:913–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1608499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Global alert and response (GAR): Chikungunya in India. Geneva: WHO; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor AJ, Paris DH, Newton PN. A systematic review of mortality from untreated scrub typhus (Orientia tsutsugamushi) PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]