Abstract

The tumor suppressor CYLD is a deubiquitinating enzyme that suppresses polyubiquitin-dependent signaling pathways, including the proinflammatory and cell growth–promoting NF-κB pathway. Missense mutations in the CYLD gene are present in individuals with syndromes such as multiple familial trichoepithelioma (MFT), but the pathogenic roles of these mutations remain unclear. Recent studies have shown that CYLD interacts with a RING finger domain protein, mind bomb homologue 2 (MIB2), in the regulation of NOTCH signaling. However, whether MIB2 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that acts on CYLD is unknown. Here, using the cell-free–based AlphaScreen and pulldown assays to detect protein-protein interactions, along with immunofluorescence assays and murine Mib2 knockout cells and animals, we demonstrate that MIB2 promotes proteasomal degradation of CYLD and enhances NF-κB signaling. Of note, arthritic inflammation was suppressed in Mib2-deficient mice. We further observed that the ankyrin repeat in MIB2 interacts with the third CAP domain in CYLD and that MIB2 catalyzes Lys-48–linked polyubiquitination of CYLD at Lys-338 and Lys-530. MIB2-dependent CYLD degradation activated NF-κB signaling via tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) stimulation and the linear ubiquitination assembly complex (LUBAC). Mib2-knockout mice had reduced serum interleukin-6 (IL-6) and exhibited suppressed inflammatory responses in the K/BxN serum-transfer arthritis model. Interestingly, MIB2 significantly enhanced the degradation of a CYLDP904L variant identified in an individual with MFT, although the molecular pathogenesis of the disease was not clarified here. Together, these results suggest that MIB2 enhances NF-κB signaling in inflammation by promoting the ubiquitin-dependent degradation of CYLD.

Keywords: ubiquitin, inflammation, NF-kappa B (NF-KB), autoimmunity, cellular immune response, CYLD, mind bomb homologue 2 (MIB2), mind bomb E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 2, multiple familial trichoepithelioma (MFT), protein array, NF-κB pathway

Introduction

NF-κB is a transcription factor complex that regulates the expression of various human genes involved in numerous important biological processes, including inflammatory and immune responses, proliferation, and cell development (1, 2). Activation of NF-κB occurs in response to various signals, including cytokines, injury, viral infection, and stress. Inappropriate activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway promotes autoimmune diseases, chronic inflammation, and various cancers (3–7). Under basal conditions, NF-κB is maintained in an inactive form as a result of its interaction with the inhibitory protein, IκB. Activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway is typically initiated by extracellular stimuli. These stimuli are recognized by cell surface receptors and are transmitted into the cell through the use of adaptor signaling proteins, which initiate a signaling cascade. The signaling cascade culminates in the phosphorylation of IκB kinase (IKK)3 after the upstream factors of IKKγ/NEMO and RIP1 are ubiquitinated. Activated IKK then phosphorylates the IκB subunit of the NF-κB–IκB complex in the cytoplasm. After the phosphorylated IκB is ubiquitinated and degraded by proteasome, the NF-κB proteins are released and the free NF-κB dimer is then transported into the nucleus and induces the expression of its target genes (8, 9). Ubiquitination is therefore an important regulatory mechanism in the NF-κB signaling cascade.

Ubiquitination is a posttranslational modification of proteins that forms a part of the energy-dependent protein degradation mechanism that acts via the proteasome. It is known to be involved in the control of various kinds of biological phenomena, including the cell cycle, signal transduction, and transcriptional regulation (10, 11). Ubiquitin consists of 76 amino acids and contains a posttranslational modification site where it is attached to a substrate protein. Ubiquitination is carried out in three steps, activation, conjugation, and ligation, performed by ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugation enzymes (E2), and ubiquitin ligases (E3), respectively (10, 11). Recent studies have shown that the type of ubiquitin linkage formed determines the subsequent biological effect of the ubiquitination event (12). In particular, it has been shown that a Lys-48–linked polyubiquitin chain is involved in degradation by the proteasome, whereas a Lys-63–linked and Met-1–linked linear polyubiquitin chains are involved in the regulation of signal transduction such as NF-κB activation pathway (13–15). In addition, these polyubiquitin chains are deconjugated by specific deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), suggesting that linkage-dependent signaling is a reversible response (16). Cylindromatosis (CYLD), having DUB activity, is a tumor suppressor that plays a key role in proliferation and cell death (17). CYLD was originally identified as a gene that is mutated in familial cylindromatosis, a genetic mutation that causes the development of cancerous skin appendages, called cylindromas (17). Mutations in the CYLD gene are found in individuals with numerous syndromes, including Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, familial cylindromatosis, and multiple familial trichoepithelioma (MFT), which are all characterized as having a variety of skin appendage neoplasms (18). At least nine missense mutations in CYLD have been found in these diseases. The nonsense mutations are known to cause disease as a result of CYLD deficiency; however, the role of the missense mutations remains unclear. Moreover, down-regulation of CYLD occurs in various types of human cancers, including melanoma and colon and lung cancers, in promoting tumorigenesis (17, 19–22).

CYLD has important roles in the regulation of NF-κB signaling (17). CYLD negatively regulates the NF-κB signaling pathway by removing Lys-63–linked and linear polyubiquitin chains from NEMO and RIP1 (23, 24). The function of the CYLD protein is itself regulated by posttranslational modification. In particular, a reduction in CYLD protein levels by ubiquitination leads to constitutive NF-κB activation and the induction of cancer. Importantly, constitutive NF-κB activation has been observed in cervical head and neck cancers (25). Recently, mind bomb homologue 2 (MIB2)/skeletrophin has been identified as a CYLD-interacting protein. MIB2 is an E3 ligase, which targets the intracellular region of Jagged-2 (JAG2), a NOTCH family ligand, thereby regulating the NOTCH signaling pathway (26). On the other hand, MIB2 also controls Bcl10-dependent NF-κB activation (27, 28). However, cellular functions of MIB2 on CYLD-mediated NF-κB regulation remain elusive. Here, we report that MIB2 directly mediates the degradation of CYLD through a ubiquitin-dependent pathway. Subsequently, MIB2 promotes activation of the canonical NF-κB pathway leading to inflammatory response. Furthermore, MIB2 significantly enhances degradation of the missense CYLDP904L variant found in multiple familial trichoepitheliomas.

Results

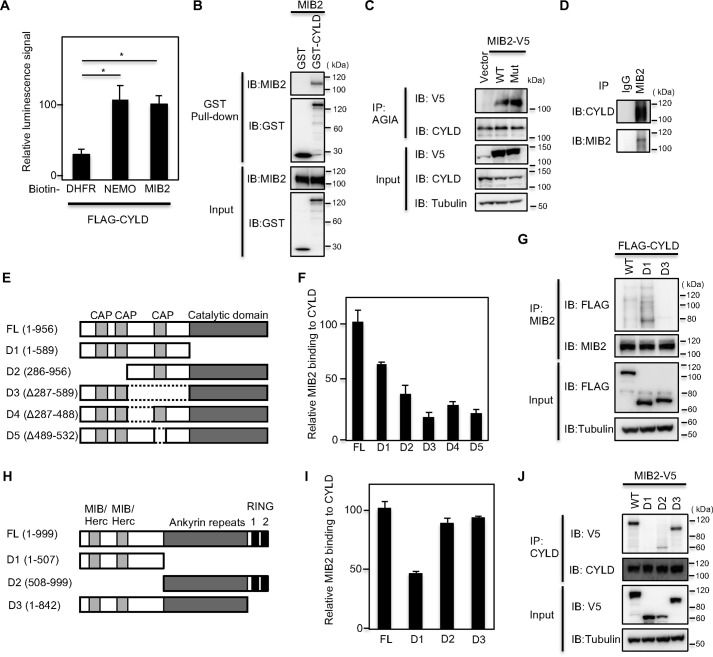

MIB2 interacts with CYLD

A recent report showed the interaction between MIB2 and CYLD using co-immunoprecipitation from cell extracts (26). To confirm this interaction in vitro, we used the wheat cell–free–based AlphaScreen method as the protein-protein interaction detection system, as we have reported recently (29). NEMO protein is well-known to be an interaction partner of CYLD (30), and for this reason we used it as a positive control for this experiment. As expected, in the AlphaScreen assay, NEMO interacted with CYLD (see the middle bar in Fig. 1A). Importantly, MIB2 also interacted with CYLD, producing a very similar signal to that seen with NEMO (right-hand bar), indicating that MIB2 interacts with CYLD in vitro. To confirm this interaction, we also performed a GST-pulldown experiment using a GST-CYLD fusion protein and MIB2. Similar to the data in Fig. 1A, MIB2 was shown to interact with GST-CYLD (Fig. 1B), indicating that CYLD forms a distinct complex with MIB2. Next, to confirm this interaction in cells, we used the AGIA-tag system because it is a highly sensitive tag based on a rabbit mAb (31). AGIA-tagged CYLD was transfected into HEK293T cells with WT MIB2 or a catalytically inactive form (Mut). Both WT and Mut-MIB2 proteins were co-immunoprecipitated with AGIA-CYLD protein (Fig. 1C), suggesting that MIB2 interacts with CYLD in cells. Furthermore, we also observed that endogenous MIB2 could interact with endogenous CYLD in HEK293T cells by immunoprecipitation using an anti-MIB2 antibody (Fig. 1D). Taken together, these data suggest that MIB2 directly interacts with CYLD in cells.

Figure 1.

MIB2 interacts with CYLD. A, determination of CYLD-MIB2 interaction by AlphaScreen. FLAG-CYLD and biotinylated DHFR, NEMO, or MIB2 were synthesized by using a wheat cell–free system, and their interactions were analyzed by AlphaScreen. Mean ± S.E. (n = 4). Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA. *, p < 0.01. B, determination of CYLD-MIB2 interaction by pulldown assay. GST pulldown assay was carried out using control GST or GST-CYLD fusion proteins on Sepharose beads followed by incubation with MIB2. C, analysis of CYLD-MIB2 interaction in cells. Immunoprecipitation using an anti-AGIA antibody was performed from extracts of HEK293T cells transfected with V5-tagged MIB2 and AGIA-tagged CYLD. The presence of MIB2 in the immunoprecipitate was evaluated by immunoblotting with the respective antibody. The MIB2 mutant (Mut) used contained a CS mutation in the two RING domains. D, determination of endogenous CYLD-MIB2 interaction. Immunoprecipitation using either control IgG or anti-MIB2 antibody was performed from HEK293T cell extracts. The endogenous interaction of MIB2 with CYLD was evaluated by immunoblotting with an anti-CYLD antibody. E, schematic representation of full-length CYLD (FL), along with its various deletion mutants (D1–D5). F, identification of CYLD-binding region in vitro. The AlphaScreen analysis was performed between MIB2 and CYLD or its deletion mutants. Biotinylated MIB2, or FLAG-CYLD FL and its various deletion mutants, were synthesized by using wheat cell–free system, and then were used. G, identification of CYLD-binding region in cell. HEK293T cells expressing endogenous MIB2 were transfected with the indicated FLAG-tagged CYLD constructs and the interaction between CYLD and MIB2 was determined by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. H, schematic representation of full-length MIB2 (FL), along with its various deletion mutants (D1–D3). I, identification of MIB2-binding region in vitro. The AlphaScreen signals between CYLD and MIB2 or its deletion mutants. Biotinylated CYLD or FLAG-MIB2 FL and its various deletion mutants were used. J, identification of MIB2-binding region in cell. HEK293T cells expressing endogenous CYLD were transfected with the indicated V5-tagged MIB2 constructs, and the interaction between CYLD and MIB2 was determined by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies.

CYLD contains three CAP domains and a catalytic domain (Fig. 1E). To identify the region in CYLD that interacts with MIB2, we generated five deletion mutants of CYLD and expressed them as N-terminally FLAG-tagged proteins. All of the recombinant CYLD mutant proteins and the MIB2 protein were produced using the cell-free system and the protein-protein interactions were analyzed using an AlphaScreen similar to the experiment described in Fig. 1A. The data indicated that three mutants, namely D3 (Δ287–589), D4 (Δ287–488), and D5 (Δ489–532) had reduced binding compared with the other two deletion mutants, D1 (1–589) and D2 (286–589) (Fig. 1F). To confirm the identification of the CYLD region that bound to MIB2 in cells, full-length CYLD and the two D1 and D3 mutants were overexpressed in cells. Immunoprecipitation using an anti-MIB2 antibody showed that the D3 mutant could not be co-immunoprecipitated with MIB2, whereas full-length CYLD and the D1 mutant were co-immunoprecipitated (Fig. 1G), suggesting that MIB2 principally interacts with the third CAP domain (amino acids 287–589) in the central region of CYLD.

MIB2 has five conserved domains, two MIB/Herc domains, an ankyrin repeat domain, and two RING domains (Fig. 1H). To identify the region in MIB2 that interacts with CYLD, we generated three deletion mutants of MIB2. An in vitro AlphaScreen assay (Fig. 1I) and a cell-based assay (Fig. 1J) revealed that CYLD interacts with the ankyrin repeat region of MIB2. Next, we examined the cellular localization of both CYLD and MIB2 by immunofluorescence. The data revealed that both CYLD and MIB2 were co-localized in the cytoplasm (Fig. S1A). Interestingly, the RING domains-deleted mutant of MIB2 (MIB2ΔRING) was not localized in the cytoplasm, but instead was found to be localized in the nucleus (Fig. S1B) Therefore the interaction between CYLD and MIB2ΔRING could not be confirmed in the cells. Taken together, these results indicated that MIB2 interacts with CYLD both in vitro and in cells.

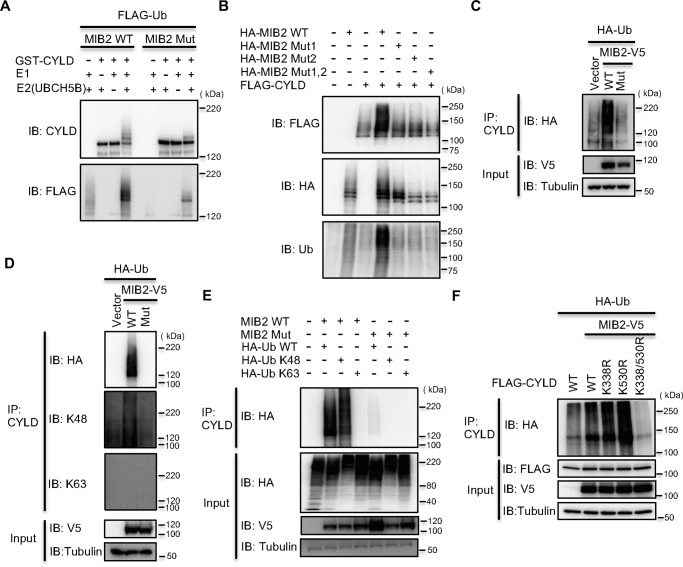

MIB2 ubiquitinates CYLD via a Lys-48–linked polyubiquitin chain

MIB2 possesses RING-type E3 ligase activity (26, 28), and a recent study has shown that MIB2 enhances NF-κB activation by its auto-ubiquitination through Lys-63–linked ubiquitination with a nondegradative polyubiquitin chain (28). In addition, CYLD has been shown to be a negative regulator of NF-κB signaling (23, 30). From these two lines of evidence, we considered the possibility that MIB2 ubiquitinates CYLD through Lys-48–linked ubiquitination with a degradative polyubiquitin chain, but not through the Lys-63–linked ubiquitination. We therefore assessed whether MIB2 can directly ubiquitinate CYLD using an in vitro ubiquitination assay with purified recombinant GST-CYLD and WT MIB2 or a catalytically inactive MIB2 mutant. The ubiquitination assay showed that WT MIB2 could efficiently ubiquitinate CYLD (MIB2 WT, left panel in Fig. 2A), whereas the catalytically inactive form (MIB2 Mut, right panel in Fig. 2A) could not. Because MIB2 has two RING domains, the conserved cysteine residue in each RING domain was mutated to serine (CS mutation), with Mut1 and Mut2 being the first and second RING CS mutants, respectively. Both Mut1 and Mut2 had a lower level of ubiquitination of CYLD compared with WT MIB2, although the double mutant (Mut1, 2) completely lacked ubiquitination activity (Fig. 2B), suggesting that both of the RING domains in MIB2 function in the ubiquitination of CYLD.

Figure 2.

MIB2 ubiquitinates CYLD via Lys-48–linked polyubiquitin chain. A, analysis of CYLD ubiquitination by MIB2 in vitro. In vitro ubiquitination assay was performed using recombinant GST-CYLD as a substrate in the presence of FLAG-tagged ubiquitin, E1 (UBE1), E2 (UbcH5B), recombinant His-tagged WT MIB2 (MIB2 WT) and catalytically inactive MIB2 (MIB2 Mut) in various combinations as indicated. B, identification of RING domains of MIB2 indispensable for CYLD ubiquitination. In vitro ubiquitination assay was performed using recombinant HA-tagged WT MIB2 (MIB2 WT), a MIB2 RING1 mutant (Mut1), a MIB2 RING2 mutant (Mut2), and a RING1/RING2 double mutant of MIB2 (Mut1, 2) in various combinations as indicated. C, analysis of CYLD ubiquitination by MIB2 in cell. MIB2 was expressed in HEK293T cells along with HA-ubiquitin. Ubiquitination of the endogenous CYLD was evaluated by immunoprecipitation of CYLD using an anti-CYLD antibody followed by anti-HA immunoblotting. Vector: mock pcDNA3.2, Mut: catalytically inactive form. D, identification of the type of polyubiquitination chain of MIB2 for CYLD ubiquitination using specific antibody. V5-tagged WT or catalytically inactive MIB2 (Mut) was expressed in HEK293T cells along with HA-tagged WT ubiquitin (Ub). Cells were treated with MG132 (10 μm) for 6 h and the level of CYLD ubiquitination was evaluated by immunoprecipitation of CYLD using an anti-CYLD antibody followed by immunoblotting with anti-HA, anti–Lys-48 (K48) Ub, or anti–Lys-63 (K63) Ub antibodies. E, determination of the type of polyubiquitination chain of MIB2 for CYLD ubiquitination using ubiquitin mutants. FLAG-tagged CYLD was co-transfected with either control, WT MIB2, or catalytically inactive MIB2 (Mut), along with either HA-tagged WT, Lys-48, or Lys-63 ubiquitin (Ub). Cells were treated with MG132 (10 μm) for 6 h and the level of CYLD ubiquitination was evaluated by immunoprecipitation of CYLD using an anti-CYLD antibody, followed by anti-HA immunoblotting. F, identification of CYLD-ubiquitination site by MIB2. WT MIB2 was expressed in HEK293T cells along with HA-ubiquitin and either WT CYLD or three CYLD mutants (K338R, K530R, and K338/530R). Ubiquitination of the overexpressed CYLD was evaluated by immunoprecipitation of CYLD using an anti-FLAG antibody followed by anti-HA immunoblotting.

Next, we attempted to confirm ubiquitination in cultured cells. HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with FLAG-tagged CYLD and either V5-tagged WT MIB2 or a catalytically inactive MIB2 (containing a CS mutation in both RING domains) along with HA-tagged ubiquitin. Following immunoprecipitation with anti-CYLD antibody and immunoblotting by anti-HA antibody, we detected significant ubiquitination of CYLD when it was co-expressed with WT MIB2, but not with the catalytically inactive mutant (Fig. 2C, IB: HA). In order to identify the type of polyubiquitin chain conjugated to CYLD by MIB2, we used specific antibodies, which are capable of detecting either Lys-48– or Lys-63–linked polyubiquitin, as well as ubiquitin mutants lacking the ubiquitination sites except for Lys-48 or Lys-63. Ubiquitination of CYLD was detected using the specific antibody against Lys-48–linked polyubiquitin (IB: Lys-48 panel in Fig. 2D), whereas it was not found using the anti–Lys-63 polyubiquitin antibody (IB: Lys-63 panel). In the same manner, a cell-based ubiquitination assay using HA-tagged single lysine ubiquitin mutants at Lys-48 or Lys-63 clearly showed that ubiquitination of CYLD was detected using Lys-48–ubiquitin (HA-Ub Lys-48), but not Lys-63–ubiquitin (HA-Ub Lys-63) (Fig. 2E). Taken together, these data indicate that MIB2 mediates Lys-48–linked polyubiquitination of CYLD.

To identify a ubiquitination site(s) on CYLD, a LC-MS/MS analysis was performed on K-ϵ-GG antibody immunoprecipitates of MIB2-ubiquitinated CYLD. This MS analysis showed that Lys-338 and Lys-530 in CYLD were ubiquitinated (Fig. S2). To confirm these findings, we constructed three mutants of CYLD lacking these ubiquitination sites namely K338R, K530R, and the double mutant K338/530R4 and transfected them into cells. As a result, CYLD containing the double mutation was not ubiquitinated, whereas the single mutants were ubiquitinated by MIB2 (Fig. 2F). These data indicate that MIB2-dependent ubiquitination of CYLD occurs at both Lys-338 and Lys-530. Interestingly, these two ubiquitination sites are located in the MIB2 interaction domain (287–589) (Fig. 1, E–G) and have been highly conserved among the CYLD orthologs (Fig. S3), suggesting that CYLD may be regulated by MIB2 through the ubiquitination of these lysines in many species.

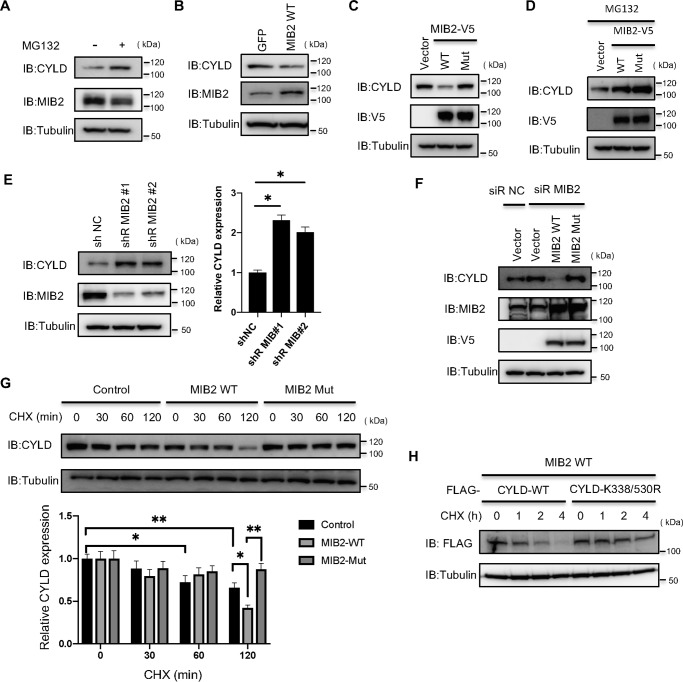

MIB2 regulates CYLD protein stability through polyubiquitination

Next, we investigated whether the Lys-48–linked polyubiquitination of CYLD by MIB2 induces CYLD degradation. The endogenous CYLD protein in HeLa cells endogenously expressing the MIB2 protein was stabilized by treatment with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Fig. 3A), suggesting that CYLD is degraded by the 26S proteasome. To test whether the destabilization of CYLD depends on MIB2, we established stable cell lines constitutively expressing MIB2 or GFP. As a result, the level of the endogenous CYLD protein decreased following constitutive expression of MIB2 compared with that of the negative control (GFP) (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, HeLa cells were transiently co-transfected with CYLD and either V5-tagged WT MIB2 or the catalytically inactive MIB2 mutant (containing CS mutations, Mut1,2, in both RING domains). Co-expression of CYLD and MIB2 WT resulted in a remarkable decrease in the level of CYLD, whereas no decrease in CYLD was seen in the presence of the catalytically inactive MIB2 mutant (Fig. 3C). This MIB2-dependent decrease in CYLD was completely recovered following treatment of the cells with MG132 (Fig. 3D), suggesting that MIB2-dependent ubiquitination of CYLD induces its degradation by the proteasome.

Figure 3.

MIB2 regulates CYLD protein stability by polyubiquitination. A, analysis of CYLD expression level by MG132 treatment. Protein expression levels of CYLD and MIB2 were analyzed in MG132-treated HeLa cells. B, analysis of CYLD expression level by constitutively overexpressed MIB2. HeLa cells stably expressing GFP or MIB2 were analyzed for the expression levels of CYLD and MIB2 by immunoblotting with their respective antibodies. C, determination of CYLD protein levels by overexpressed MIB2. CYLD were transiently transfected with plasmids encoding either V5-tagged WT MIB2 (WT) or a catalytically inactive mutant MIB2 (Mut) in HeLa cells. The expression level of CYLD was determined by immunoblotting with an anti-CYLD antibody. D, determination of CYLD protein levels by overexpressed MIB2 in MG132-treated cells. V5-tagged WT or Mut MIB2 was expressed in HeLa cells along with CYLD. Cell lysates were prepared after 6 h with 10 μm MG132 and analyzed by immunoblotting using an anti-CYLD antibody. E, analysis of CYLD expression level by MIB2 knockdown. HeLa cells stably expressing a control shRNA or one of two MIB2 shRNAs were analyzed for their expression of CYLD and MIB2 by immunoblotting with their respective antibodies. These quantified data were statistically analyzed and shown as a bar graph. Mean ± S.E.M. (n = 3). Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA. *, p < 0.05. F, analysis of CYLD stabilization depending on the MIB2 in MIB2 knockdown cells. After transfection with a control or a MIB2 siRNA, HeLa cells transiently expressing CYLD were transfected with plasmids encoding V5-tagged WT MIB2 or siRNA-resistant mutant. G, stabilization of CYLD protein by MIB2. HeLa cells transiently expressing CYLD were transfected with plasmids encoding V5-tagged WT MIB2 (MIB2 WT) or a catalytically inactive mutant (MIB2 Mut). After 22 h of transfection, the cells were treated with CHX and harvested at the indicated times. The expression levels of CYLD were determined by anti-CYLD immunoblotting. As control, mock pcDNA3.2 was transfected. These quantified data were statistically analyzed and shown as a bar graph. Mean ± S.E.M. (n = 3). Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01. H, role of MIB2-mediated ubiquitination sites of CYLD on its stability. HeLa cells transiently expressing V5-tagged WT MIB2 were transfected with plasmids encoding WT CYLD or CYLD-K338/530R mutant. After 22 h of transfection, cells were treated with CHX and harvested at the indicated times.

To test whether the expression level of endogenous MIB2 affects the stability of CYLD, two MIB2-specific siRNAs were used to repress MIB2 expression in cells. Both MIB2-specific siRNAs dramatically increased the level of CYLD protein compared with the negative control (Fig. 3E). To confirm this result, an MIB2 siRNA-resistant gene was designed and was transiently transfected in HeLa cells. The data showed that the expression of CYLD was dramatically decreased following expression of the siRNA-resistant MIB2 gene (Fig. 3F), although there was no change in cells expressing MIB2 mutant compared with the control, suggesting that MIB2 expression decreases the levels of CYLD. Furthermore, using a cycloheximide chase experiment, co-expression with CYLD of V5-tagged WT MIB2, but not the catalytically inactive MIB2, led to a decrease in the half-life of the CYLD protein (Fig. 3G). We also examined the half-life of the CYLD-K338/530R mutant that lacks the two ubiquitination sites using the same cycloheximide chase experiment. The data revealed that the ubiquitination mutant was stabilized even though MIB2 was overexpressed in the cells (Fig. 3H), suggesting that the CYLD destabilization depends on ubiquitination by MIB2. Taken together, these results indicate that MIB2 decreases the stability of CYLD in cells. A recent study has shown that that β-TRCP from the SCF (Skp-Cullin1-F-box protein) complex (SCFβ-TRCP), known to be a cullin-based E3 ligase, degrades CYLD by ubiquitination and promotes osteoclast differentiation (32). Therefore, we examined whether CYLD degradation by MIB2 is related to the activity of β-TRCP. Knockdown of the β-TRCP protein had no effect on MIB2-dependent CYLD destabilization (Fig. S4), suggesting that MIB2 degrades CYLD in a β-TRCP-independent manner.

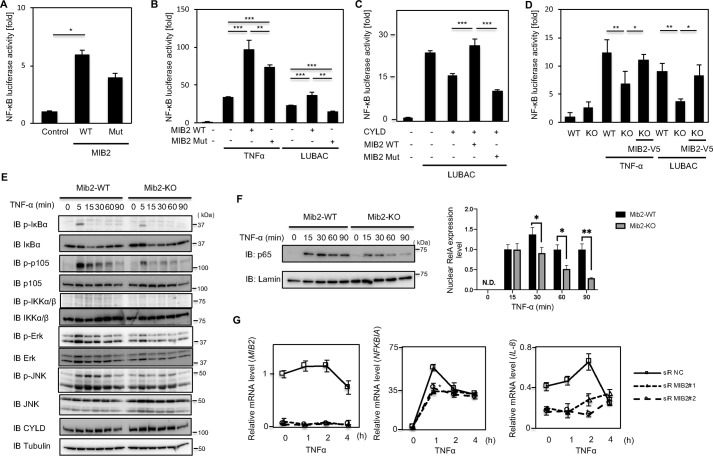

MIB2 enhances NF-κB signaling

A recent study has reported that MIB2 is required for the Bcl10-dependent activation of NF-κB (28). In addition, CYLD has been reported to be involved in the canonical NF-κB signaling pathway (33). We therefore tested whether the expression of MIB2 affects NF-κB signaling. To investigate this, we used a reporter gene containing luciferase under the control of the NF-κB-promoter. Overexpression of MIB2 enhanced NF-κB activation compared with the empty vector as a negative control (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, overexpression of MIB2 in LUBAC- or TNFα-stimulated cells also enhanced NF-κB activation (Fig. 4B). Next, to confirm whether this MIB2-dependent NF-κB activation depended on CYLD, CYLD was co-transfected with MIB2, and the effect on NF-κB–driven luciferase activity was examined. Although the expression of CYLD alone inhibited LUBAC-stimulated NF-κB activation, co-transfection of CYLD with MIB2 rescued the NF-κB activity (Fig. 4C). Moreover, we investigated whether knockout of MIB2 affects NF-κB activation. To analyze the effect of MIB2, Mib2-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells were isolated from homozygous Mib2 KO embryos. As expected, Mib2 expression levels in these cells were consistent with genotype (Fig. S5). NF-κB activity was decreased in both LUBAC- and TNFα-stimulated MEF cells (Fig. 4D). We also investigated whether proteins in the NF-κB pathway were affected by Mib2 knockout using MEFs. In TNFα-stimulated Mib2-deficient MEFs, the phosphorylation of both IκBα and p105 were remarkably decreased compared with TNFα-stimulated WT MEFs. Furthermore, the activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and c-Jun N-terminal kinase were also suppressed in a similar fashion in these Mib2-deficient MEFs (Fig. 4E). The appearance of p65 (RelA) in the nucleus following TNFα stimulation was also dramatically attenuated in these Mib2-deficient MEFs (Fig. 4F). MIB2 knockdown in HeLa cells also decreased the mRNA levels of several NF-κB target genes including NFKBIA(IκBα), TNFAIP3, and IL-8 (Fig. 4G). Taken together, these results suggest that MIB2-dependent CYLD degradation induces constitutive activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway. Interestingly, although the inactive form of MIB2 did not stimulate the activation of the NF-κB reporter following its co-expression with CYLD (Fig. 4C), its overexpression alone induced NF-κB activation (Fig. 4, A and B). These results suggest that the MIB2-CYLD interaction inhibits NF-κB activation when CYLD expression is low level.

Figure 4.

MIB2 enhances NF-κB signaling. A, analysis of NF-κB activity by overexpressed MIB2 under basal conditions. HEK293T cells were transfected with either WT MIB2 (WT), or a catalytically inactive MIB2 (Mut), along with a luciferase reporter containing the NF-κB promoter. Data from each luciferase assay shown are derived from three independent experiments. B, analysis of NF-κB activity by overexpressed MIB2 in HEK293T cells stimulated by TNFα and LUBAC. In LUBAC stimulation, NF-κB promoter activities were measured in HEK293T cells transfected with either WT or Mut MIB2, along with HOIP/HOIL-1L. In TNFα stimulation, the NF-κB promoter activities in HEK293T cells transfected with either WT or Mut MIB2 were measured following stimulation with TNFα for 4 h. C, analysis of NF-κB activity by co-expressed CYLD and MIB2. The NF-κB promoter activities were measured in HEK293T cells transfected with either WT or Mut MIB2, along with CYLD and HOIP/HOIL-1L. D, analysis of NF-κB activity in Mib2-deficient MEF cell. The NF-κB promoter activities induced by TNFα or LUBAC stimulation were measured in WT or Mib2-deficient MEF cells (KO). MIB2-V5 indicates transfection of human MIB2. Cells were treated with TNFα for 4 h or transfected with HOIP/HOIL-1L for TNFα or LUBAC stimulation, respectively. A, mean ± S.E. (n = 4). B–D, mean ± S.E. (n = 3). Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. E, analysis of phosphorylated NF-κB proteins in Mib2-deficient MEF cell. NF-κB–related proteins in extracted from either WT (Mib2-WT) or Mib2-deficient (Mib2-KO) MEF cells were analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. “p-” denotes phosphorylated protein. F, analysis of nuclear p65 proteins in Mib2-deficient MEF cells. Nuclear p65 was extracted from either WT (Mib2-WT) or Mib2-deficient (Mib2-KO) MEF cells. G, quantitative PCR analyses of NF-κB target genes in HeLa cells. After cells were transiently transfected with a control siRNA or one of two MIB2-targeted siRNAs they were treated with TNFα for the indicated times before quantitative PCR analysis. Mean ± S.E. (n = 3). Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA. *, p < 0.05 versus control.

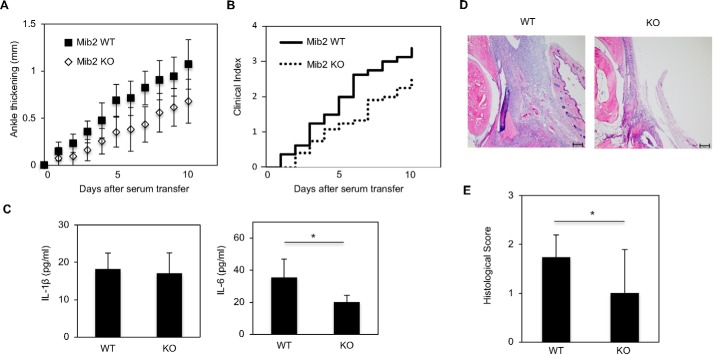

Mib2-KO mice showed suppression of the inflammatory response in the K/BxN serum-transfer arthritis model

As shown in Fig. 4, MIB2 enhances NF-κB signaling by inducing the degradation of CYLD. Next, we investigated the phenotype of Mib2-deficient mice under conditions of chronic inflammation, because constitutive NF-κB signaling is known to drive inflammation (34). The K/BxN arthritis model is known to share many features in common with human rheumatoid arthritis. In addition, the K/BxN serum-transfer arthritis (STA) model is a murine model in which rheumatoid arthritis, as well as other arthritic conditions, are known to occur (35). Accordingly, we investigated inflammation in the Mib2-KO mice using the K/BxN STA model. Mice were injected twice with K/BxN serum on day 0 and day 2, after which ankle thickness in the mice was measured over a period of 10 days. As a result, compared with Mib2-WT mice, Mib2-KO mice had a remarkable suppression of the inflammatory arthritis induced by the K/BxN serum transfer, as evidenced by the reduced ankle thickness (Fig. 5A). We also evaluated and scored the inflammation using a scale from 0 to 4 (36). In keeping with the ankle thickness data, the Mib2-KO mice showed a significantly lower clinical score compared with the WT mice (Fig. 5B). After 10 days, the serum levels of the inflammatory cytokine IL-6 were significantly decreased in KO mice compared with WT mice, whereas there were no differences in the IL-1β serum levels (Fig. 5C), suggesting that the Mib2-deficient suppression of inflammatory arthritis depends on NF-κB signaling. In addition, a pathological diagnosis and histological analysis showed that there were reduced histological scores in Mib2-KO mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 5, D and E). These in vivo data therefore suggest that MIB2 plays a role as an enhancer of inflammation driven by NF-κB signaling.

Figure 5.

The inflammatory response to K/BxN arthritis is suppressed in Mib2-KO mice. A and B, arthritis was induced in either Mib2-WT or KO mice by i.p. injection of K/BxN serum on day 0 and day 2. Ankle thickness (A) and clinical score (B) were recorded daily for 10 days. Ankle thickness was measured in millimeters using a caliper. C, measurement of the levels of IL-6 and IL-1β by ELISA in mouse serum following sacrifice of the animals. D, representative images of arthritis in the Mib2-WT and KO mice at day 10 by H&E staining. Original magnification, 40×. Scale bar: 200 μm. E, evaluation of the histological score based on H&E staining. The histological score was evaluated in a blinded fashion. C and E, mean ± S.E. (n = 7). Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA. *, p < 0.05.

Unfortunately, commercially available anti-CYLD antibodies could not detect mouse Cyld protein in the tissues of Mib2-KO mice.

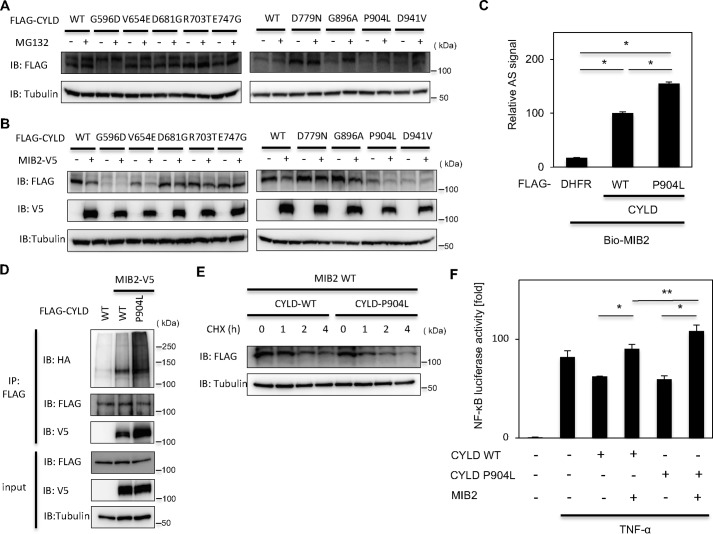

The CYLDP904L mutation found in MFT is predominantly degraded in a MIB2-dependent manner

Several reports have indicated that germline mutations in CYLD are related to Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, familial cylindromatosis, and MFT (18). Currently, 19 nonsense and 9 missense mutations in CYLD have been found in these diseases (Fig. S6). Although the nonsense mutations cause disease as a result of CYLD deficiency, the role of these missense mutations in disease remains unclear. We therefore investigated whether these mutations affect the MIB2-dependent degradation of CYLD. The missense mutants were introduced into FLAG-tagged CYLD and expressed in HeLa cells, with and without MG132 (Fig. 6A). As a result of this analysis, G896A and P904L were found to be stabilized by MG132 treatment, suggesting these two mutants are degraded by the proteasome. Next, we analyzed the degradation of all the FLAG-tagged CYLD missense mutants following co-expression in HEK293T cells. As a result, the degradation of two mutants, namely V654E and P904L, were significantly enhanced by MIB2 co-expression (Fig. 6B). From these two experiments, we focused on the P904L mutant. Surprisingly, the interaction between MIB2 and CYLDP904L was increased compared with WT CYLD using the AlphaScreen system (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, the MIB2-dependent ubiquitination of CYLDP904L was dramatically enhanced in cells (Fig. 6D), and the protein stability of the CYLDP904L variant was dramatically decreased (Fig. 6E). Following TNFα treatment, NF-κB activation was enhanced following the co-expression of MIB2 and CYLDP904L (Fig. 6F), suggesting the efficient degradation of CYLDP904L by MIB2 than that of normal one. Taken together, these results suggest that the CYLDP904L mutation in MFT is predominantly degraded in an MIB2-dependent manner.

Figure 6.

MIB2-mediated enhanced degradation of CYLD is involved in a pathogenesis of trichoepithelioma. A, analysis of expression levels of CYLD mutants in MG132-treated cells. HeLa cells were transfected with either WT FLAG-tagged CYLD or the indicated FLAG-tagged CYLD mutants, and the CYLD expression levels were analyzed by immunoblotting with an anti-FLAG antibody in cells treated with or without MG132. B, analysis of expression levels of CYLD mutants by overexpressed MIB2. HeLa cells transiently expressed either WT FLAG-tagged CYLD or the indicated FLAG-tagged CYLD mutants were transfected in the presence or absence of V5-tagged WT MIB2. The expression levels of the CYLD proteins were determined by anti-FLAG immunoblotting. C, determination of interaction between CYLD-P904L mutant and MIB2 by AlphaScreen. Interactions between biotinylated MIB2 (Bio-MIB2) and either FLAG-tagged WT CYLD or CYLD-P904L mutant were analyzed by AlphaScreen. D, analysis of ubiquitination of CYLD-P904L mutant by MIB2 in cell. The ubiquitination of overexpressed CYLD was evaluated by immunoprecipitation of CYLD using an anti-FLAG antibody followed by anti-HA immunoblotting. PL denotes P904L mutant of CYLD. E, destabilization of CYLD-P904L mutant by MIB2. HeLa cells transiently expressing MIB2 were transfected with plasmids encoding either FLAG-tagged WT MIB2 or the P904L mutant. After 20 h of transfection, cells were treated with CHX and harvested at the indicated times. The CYLD expression levels were determined by anti-FLAG immunoblotting. F, effects of CYLD-P904L mutant and MIB2 on TNFα-induced NF-κB activation in HEK293T cells. NF-κB promoter activities were measured in HEK293T cells transfected with either WT CYLD or the P904L mutant CYLD along with MIB2 in the presence or absence of TNFα. C and F, mean ± S.E. (n = 3). Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA. *, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01.

Discussion

In this study, we found that a deubiquitinating enzyme CYLD is degraded through ubiquitination by an E3 ubiquitin ligase MIB2. Because many signal transduction pathways are modulated by E3 ligase-dependent ubiquitination, the deubiquitination performed by DUB is a key regulator of these signaling pathways (37–41). The main enzymatic function of CYLD is to deubiquitinate two types of polyubiquitination chains, referred to as Lys-63– and linear-linked chains. These two polyubiquitin chains are found in the components of various important signaling cascades, including the NF-κB pathway, the antiviral response, and the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, and interestingly CYLD has been shown to be involved in the regulation of these pathways (25, 42, 43). On the other hand, it has been reported that MIB2 enhances the NF-κB pathway on Bcl3-dependent antiviral response signaling pathway by ubiquitinating TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) through a Lys-63–linked polyubiquitin chain (28, 44). In this study, because CYLD is a key player in NF-κB signaling, we focused mainly on this signaling pathway, and showed that MIB2 negatively regulates CYLD function in the signaling pathway. These findings indicate the possibility that MIB2 is involved in other CYLD-related signaling pathways but this remains to be addressed.

The NF-κB signaling cascade is intimately involved in the inflammatory response (1, 2). In a previous report, no notable phenotype was observed in Mib2-knockout mice (45). Accordingly, we used the K/BxN STA model in the Mib2-deficient mice to explore the role of MIB2 in the inflammation response. As shown in Fig. 5, a biological role for MIB2 in the inflammatory response is suggested whereby it acts to induce the degradation of CYLD. Because CYLD is known to be a negative regulator of inflammation (25), its degradation through an MIB2-dependent mechanism suggests that a role for MIB2 in modulating the inflammatory response is not unreasonable. The next question that needs to be asked is “How is MIB2 expression regulated?”

TNFα treatment induces the formation of a TNFR signaling complex I (TNF-RSC) containing RIP1 and TRADD that are involved in NF-κB activation (46). In addition, a recent study has shown that LUBAC directly recruits CYLD to the TNF-RSC (47) and RIP1 recruits MIB2 to the TNF-RSC (48). These results suggest that both MIB2 and CYLD are involved in TNF-RSC. Actually they were co-immunoprecipitated with RIP1 (Fig. S7). Very recently, it was reported that RIP1 is ubiquitinated by MIB2 (48). Furthermore, RIP1 ubiquitination is decreased by CYLD (49). As this study shows, MIB2 degrades CYLD. Taken together, these studies suggest that MIB2 can regulate RIP1 ubiquitination by directly its E3 ubiquitin activity and CYLD degradation.

CYLD functions as a tumor suppressor in cylindromas and trichoepithelioma (17). Currently, nine missense mutations in CYLD have been found (50–58). However, the biological role of these missense mutations is unclear. Numerous cases of trichoepithelioma have been found to contain the CYLDP904L mutation (Fig. S6). In this study, we found that the CYLDP904L-MIB2 interaction was stronger than the interaction between WT CYLD and MIB2, and furthermore the CYLDP904L variant is efficiently degraded in a MIB2-dependent manner. MIB2 mainly interacts with D3 (287–589) region of CYLD (Fig. 1, E–G) and a position of Pro-904 seems not close to D3 region. To understand the effect of P904L mutation in CYLD on MIB2 interaction and MIB2-dependent ubiquitination, further analysis will be required. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first evidence of an alteration in biological function among the known missense mutations in CYLD. Our study also suggests that screening for stronger proteins interactions among the missense CYLD mutations may be a useful approach to understand the role of other missense CYLD mutations.

Experimental procedures

Plasmids

Full-length MIB2 and CS mutant [Mut (quadruple mutant C876S/C879S/C955S/C958S)] were cloned into pcDNA3.2/V5 dest or pEU-His vectors using the Gateway cloning system (Invitrogen). FLAG-tagged CYLD, FLAG-tagged NEMO, myc-tagged HOIP, and HA-His–tagged HOIL-1L in pcDNA3.2 vector were described previously (59). The CYLD plasmid was cloned into the GST-pEU vector using the Gateway cloning system. CYLD and MIB2 mutants were generated by site-directed mutagenesis using a PrimeSTAR Mutagenesis Basal Kit. FLAG- or biotin-labeled CYLD, DHFR, NEMO, or MIB2 for use in the AlphaScreen were generated using “split-primer PCR.” Lentivirus-based GFP and MIB2 plasmids were generated using restriction enzyme digestion of a CS II-CMV-MCS-IRES2-Bsd vector. HA-tagged WT ubiquitin, Lys-48, and Lys-63 were a kind gift from Dr. Atsuo T. Sasaki, Cincinnati, OH.

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used in this study: Rabbit polyclonal anti-CYLD (used at 1:1000 dilution), a specific anti–Lys-48–linked polyubiquitin chain antibody, a specific anti–Lys-48–linked polyubiquitin chain antibody, and anti–β-TRCP (all used at 1:1000 dilution) were from Cell Signaling Technology; anti-MIB2 (used at 1:1000 dilution) was from Bethyl Laboratories; anti-NEMO (used at 1:1000 dilution) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; mouse polyclonal anti-CYLD (used at 1:1000 dilution) and anti-FLAG M2 (used at 1:2000 dilution) were from Sigma; anti-V5 (used at 1:5000 dilution) was from Invitrogen; anti-tubulin (used at 1:1000 dilution) was from Sigma; and the rat polyclonal anti–HA-HRP conjugate (used at a 1:4500 dilution) was from Roche.

Cell lines

HEK293T and HeLa cells were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in DMEM (Nissui) supplemented with 10% FBS (Sigma), 2 mm l-glutamine (Gibco), and antibiotics (100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin) (Gibco). Lentiviruses expressing GFP or MIB2 were generated according to a standard transfection protocol. After transmission of the transgene, a pool of HeLa cells resistant to blasticidin S (10 μg/ml) (Invitrogen) was generated and used in subsequent experiments. HeLa cells constitutively expressing GFP or MIB2 were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mm l-glutamine, and antibiotics (100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin).

MEFs were isolated from E13.5 embryos and cultured in high-glucose DMEM, GlutaMax, pyruvate (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1× MEM nonessential amino acids, 55 μm 2-mercaptoethanol (Gibco), and 1× antibiotic-antimycotic (Gibco) based on previous reports (60).

In vitro binding assays using the AlphaScreen technology

In vitro binding assays were performed as described previously using an AlphaScreen IgG (protein A) detection kit (Perkin Elmer) (29). Briefly, 10 μl of detection mixture containing 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.2 mm DTT, 5 mm MgCl2, 5 μg/ml anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma), 1 mg/ml BSA, 0.1 μl streptavidin-coated donor beads, and 0.1 μl anti-IgG acceptor beads were added to each well of a 384-well OptiPlate followed by incubation at 26 °C for 1 h. Luminescence was detected using the AlphaScreen detection program.

Cell transfections, immunoprecipitation, and immunoblotting

HEK293T and HeLa cells were transfected with various plasmids using the TransIT-LT1 transfection reagent (Mirus) according to the manufacturer's protocol. HEK293T and HeLa cells were transfected with a control siRNA, or an siRNA against MIB2 or β-TRCP using LipofectamineTM RNAi MAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For the phosphorylated NF-κB assay, cells were treated with TNFα (20 ng/ml). For immunoprecipitation, cells were lysed with lysis buffer (150 mm NaCl, 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mm EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100) containing a proteasome inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitors. After 2 μg of the indicated antibodies were bound to either protein A or protein G-Dynabeads (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 min at room temperature, they were incubated with whole-cell lysates overnight at 4 °C. The immunocomplexes were washed three times with the wash buffer provided in the Dynabeads kit. Immunoblotting was carried out following standard protocols. Briefly, proteins in whole-cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto a PVDF membrane by semi-dry blotting. After blocking with 5% milk/TBST, the membrane was incubated with the appropriate primary antibodies followed by a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody.

Protein purification

Purification of GST-tagged protein was carried using Protemist® DT II according to the manufacturer's protocol (CellFree Sciences Co. Ltd). Crude GST-tagged recombinant protein (6 ml) produced by the cell-free reaction was precipitated with GSH SepharoseTM 4B (GE Healthcare). Recombinant proteins were eluted with Elution Buffer A containing 10 mm reduced GSH, 50 mm Tris-HCl pH 8.0 and 50 mm NaCl. Purification of His-tagged proteins was also carried out using Protemist® DT II. Crude His-tagged recombinant protein (6 ml) produced by the cell-free reaction was precipitated with Ni Sepharose (GE Healthcare). The recombinant proteins were eluted with elution Buffer B including 500 mm imidazole, 20 mm Na-phosphate pH 7.5 and 300 mm NaCl.

In vitro ubiquitination assay

The in vitro ubiquitination assay was performed as described previously (61). The assay was carried out in a 20-μl reaction mixture containing 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.2 mm DTT, 5 mm MgCl2, 10 μm zinc acetate, 3 mm ATP, 1 mg/ml BSA, 2.5 μm FLAG-tagged ubiquitin, 50 nm E1 (Boston Biochem), 300 nm UbcH5b (Enzo Life Sciences), and 1 μl of purified recombinant CYLD and MIB2 for 3 h at 30 °C.

MS analysis

The MS analysis was performed as described previously (62). Briefly, HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated FLAG-CYLD construct along with V5-tagged MIB2 and HA-Ub. Forty-eight h after transfection, the whole-cell lysate was immunoprecipitated using an anti-FLAG antibody. Proteins were eluted using a FLAG peptide (Sigma). The eluted proteins were reduced in 5 mm Tris (2-carboxy-ethyl) phosphine hydrochloride for 30 min at 50 °C, and alkylated with 10 mm methylmethanethiosulfonate. Following this, the alkylated proteins were digested overnight at 37 °C using 1 μg trypsin. Ubiquitinated proteins were enriched using the PTMScan ubiquitin remnant motif (K-ϵ-GG) kit (5562, Cell Signaling Technology) prior to LC-MS/MS analysis. Desalted tryptic digests were analyzed by nanoLC (Easy-nLC 1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled to a Q Exactive Plus (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Proteome Discoverer 1.4 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to generate peak lists and analyze data.

RNA interference

Negative control (siRNA NC) siRNA and siRNAs against MIB2 (siRNA #1, 5′-GAACCUGCGUGUAGCAGUCGCUGGU-3′; siRNA #2, 5′-CCUCACGGAGGUGCCAAACAUCGAU3′), and β-TRCP (siRNA, 5′-GAACUAUAAAGGUAUGGAAtt-3′) were purchased from Invitrogen.

The lentivirus-mediated RNAi analysis was performed as described previously (63). The following sequences were selected as RNAi targets: MIB2 (shRNA MIB2#1, 5′-GATCCGGAGGTGCCAAACATCGATGTTTCAAGAGAACATCGATGTTTGGCACCTCCTTTTTG-3′, shRNA MIB2#2, 5′-GATCCCTAGCTGTGAGAAAGATTCTTTCAAGAGAAGAATCTTTCTCACAGCTAGCTTTTTG-3′), no-target (LacZ) (shRNA NC, 5′-GACTACACAAATCAGCGAT-3′). After construction of the shRNA expression plasmids by insertion of the respective double strand oligonucleotides, the lentivirus particles were generated using a standard transfection protocol. HeLa cells infected with lentiviruses expressing shRNA NC, shRNA MIB2#1 or shRNA MIB2#2 were used 5 days later.

Protein turnover analysis

All the turnover analyses were carried out using HeLa cells. Cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids. The following days, cells were treated with 100 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) for the indicated times.

Reporter assays using TNFα and LUBAC

All reporter assays were performed using a Dual-Luciferase Assay Kit (Promega). Cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids including LUBAC and reporters together with the pRL-TK reporter. Twenty h after transfection, the cells were treated with TNFα (20 ng/ml).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total cellular RNA was extracted from HeLa cells using a RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) and was reverse transcribed using a Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche). The following primer sets were designed using the Assay Design Center software (Roche): MIB2 (forward: 5′-CTTCGACCGCACGAGACC-3′, reverse: 5′-CTGAAAATGCCCCTTAGTG-3′); IκBα (forward: 5′-GTCAAGGAGCTGCAGGAGAT-3′, reverse: 5′-ATGGCCAAGTGCAGGAAC-3′); A20 (forward: 5′-GCAACAACAAGTATTCCTACACCA-3′, reverse: 5′-GGGAGAGCTTGTCAAACAGC-3′); and IL-8 (forward: 5′-GAGCACTCCATAAGGCACAAA-3′, reverse: 5′-ATGGTTCCTTCCGGTGGT-3′). Gene expression was normalized to ACTB (Roche).

Mib2 knockout mouse

The Mib2 knockout first mice (C57BL/6NTac-Mib2tm1a(EUCOMM)Wtsi/IcsOrl) were obtained from The European Mouse Mutant Archive (64) and the floxed mice were generated by crossing with ACTB-FLPe mice (The Jackson Laboratory). Then, systemic knockout mice were generated by crossing Mib2 flox mice and CMV-Cre mice, kindly provided by Prof. P. Chambon (65). Heterozygous knockout mice (Mib2+/−) were mated, and WT littermates (Mib2+/+) and homozygous knockout littermates (Mib2−/−) were obtained and are referred to as WT and KO, respectively. All mice were housed in a specific pathogen–free facility under climate-controlled conditions with a 12-h light/dark cycle and were provided with water and a standard diet (MF, Oriental Yeast, Japan) ad libitum. Animal experiments were approved by the Animal Experiment Committee of Ehime University (approval number 37A1-1/16) and were performed in accordance with the Guidelines of Animal Experiments of Ehime University.

K/BxN STA

STA was induced by the transfer of sera obtained from arthritic K/BxN mice, which spontaneously develop arthritis. K/BxN mice were generated by the crossing of NOD mice (Japan SLC, Inc., Shizuoka, Japan) with KRN transgenic mice, kindly provided by Drs. C. Benoist and D. Mathis (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) (66). K/BxN serum was harvested, pooled, and stored at −80 °C.

Eight- to 12-week-old male mice were used for K/BxN STA (n = 7). For STA induction, 100 μl of serum was injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) into these mice on day 0 and day 2, respectively.

The severity of arthritis in the limb was scored daily from day 0 to day 10. Evaluation of arthritis severity was performed as described previously (36): 0 = no evidence of erythema and swelling; 1 = erythema and mild swelling confined to the tarsals or ankle joint; 2 = erythema and mild swelling extending from the ankle to the tarsals; 3 = erythema and moderate swelling extending from the ankle to metatarsal joints; 4 = erythema and severe swelling encompass the ankle, foot, and digits, or ankylosis of the limb. Paw thickness was measured daily with a digital caliper.

Histological evaluation

Mice were euthanized at 10 days after K/BxN STA, and the ankle joints were cut and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by decalcification with 0.5 m EDTA-PBS. Following this, the samples were embedded with paraffin and sectioned into 5-μm thickness, which were stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Histological score was evaluated in a sample-blind manner. The histological severity of arthritis was graded using a scale of 0 to 3 for each ankle sections, where 0 = noninflamed, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe.

Immunofluorescent staining

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 5 min at room temperature, and then permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min. After blocking with 5% calf serum in TBST for 1 h, cells were incubated with a primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. After washing with TBST, cells were incubated with the appropriate Alexa Fluor 488– and/or 555–conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes) for 1 h at room temperature. Nuclei were counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. After a final wash with TBST, coverslips were mounted with anti-fade. Fluorescence images were acquired with the LSM710 laser scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss).

Bioinformatics analysis

CYLD sequence of the following 11 biological species were based on the NCBI GenBankTM: Homo sapiens (NP_001035814.1), Mus musculus (NP_001121643.1), Rattus norvegicus (NP_001017380.1), Bos taurus (NP_001039882.1), Xenopus tropicalis (NP_001116960.1), Macaca mulatta (XP_014981594.1), Canis lupus familiaris (XP_005617624.1), Pan troglodytes (XP_016785309.1), Gallus gallus (XM_015292398.2), Cricetulus griseus (XP_016829680.1) and Danio rerio (XP_005169076.1). Multiple-sequence alignment and the sequence logos were performed using Clustal Omega (67) and WebLogo3 (68), respectively.

Statistical analyses

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a post hoc Tukey's test was performed using KaleidaGraph software. Statistical significance was accepted at p < 0.05.

Author contributions

A. U., F. T., and T. S. conceptualization; A. U. software; A. U., F. T., and T. S. funding acquisition; A. U., Y. I., F. T., and T. S. validation; A. U., K. K., C. T., Y. Y., N. S., S. Y., M. H., and T. K. investigation; A. U., Y. I., F. T., and T. S. methodology; A. U., F. T., and T. S. writing-original draft; K. K., H. T., C. T., M. M., K. S., S. H., Y. I., F. T., and T. S. data curation; K. S., S. H., Y. I., F. T., and T. S. supervision; Y. I., F. T., and T. S. formal analysis; Y. I., F. T., and T. S. writing-review and editing; F. T. and T. S. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Applied Protein Research Laboratory of Ehime University, and Chie Furukawa for technical assistance. We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Atsuo Sasaki (Cincinnati, OH) for kindly providing HA-tagged ubiquitin WT, Lys-48, and Lys-63 plasmids. We thank Dr. Natsuki Matsushita (Ehime University Graduate School of Medicine) for kindly providing the CS II-CMV-GFP-IRES-Bsd-H1 vector. We also acknowledge RIKEN for kindly providing the CS II-CMV-MCS-IRES2-Bsd vector.

This work was mainly supported by the Platform Project for Supporting Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (Basis for Supporting Innovative Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (BINDS)), Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) Grants JP17am0101077, 18am0101077, and 19am0101077 (to T. S.); Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (MEXT) Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas JP25117719 and JP16H06579 (to T. S.); and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Research Fellow JP15J03774 (to A. U.). This work was also partially supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grants JP15J03774 (to A. U.), JP16K18570 (to H. T.), JP16H04729 (to T. S.), and 19H03218 (to T. S.), and by the Takeda Science Foundation. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Figs. S1–S7.

K338/530R is the double mutant K338R/K530R.

- IKK

- IκB kinase

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- CHX

- cycloheximide

- CYLD

- cylindromatosis

- DUB

- deubiquitinating enzyme

- FL

- full length

- MEF

- mouse embryo fibroblast

- MFT

- multiple familial trichoepithelioma

- MIB2

- mind bomb homologue 2

- STA

- serum-transfer arthritis

- IB

- immunoblotting.

References

- 1. Hayden M. S., and Ghosh S. (2004) Signaling to NF-κB. Genes Dev. 18, 2195–2224 10.1101/gad.1228704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Karin M., and Greten F. R. (2005) NF-κB: Linking inflammation and immunity to cancer development and progression. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5, 749–759 10.1038/nri1703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bassères D. S., and Baldwin A. S. (2006) Nuclear factor-κB and inhibitor of κB kinase pathways in oncogenic initiation and progression. Oncogene 25, 6817–6830 10.1038/sj.onc.1209942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Karin M., Cao Y., Greten F. R., and Li Z.-W. (2002) NF-κB in cancer: From innocent bystander to major culprit. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 301–310 10.1038/nrc780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Luo J.-L., Kamata H., and Karin M. (2005) IKK/NF-κB signaling: Balancing life and death—a new approach to cancer therapy. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 2625–2632 10.1172/JCI26322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grivennikov S. I., Greten F. R., and Karin M. (2010) Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 140, 883–899 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pikarsky E., Porat R. M., Stein I., Abramovitch R., Amit S., Kasem S., Gutkovich-Pyest E., Urieli-Shoval S., Galun E., and Ben-Neriah Y. (2004) NF-κB function as a tumor promoter in inflammation-associated cancer. Nature 431, 461–466 10.1038/nature02924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alkalay I., Yaron A., Hatzubai A., Orian A., Ciechanover A., and Ben-Neriah Y. (1995) Stimulation-dependent IκBα phosphorylation marks the NF-κB inhibitor for degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 10599–10603 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sethi G., Sung B., and Aggarwal B. B. (2008) Nuclear factor-κB activation: From bench to bedside. Exp. Biol. Med. 233, 21–31 10.3181/0707-MR-196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hershko A., and Ciechanover A. (1998) The ubiquitin system. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 425–479 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kerscher O., Felberbaum R., and Hochstrasser M. (2006) Modification of proteins by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 22, 159–180 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010605.093503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pickart C. M. (2001) Mechanisms underlying ubiquitination. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biochem. 70, 503–533 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Johnston J. A., Ward C. L., and Kopito R. R. (1998) Aggresomes: A cellular response to misfolded proteins. J. Cell Biol. 143, 1883–1898 10.1083/jcb.143.7.1883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mukhopadhyay D., and Riezman H. (2007) Proteasome-independent functions of ubiquitin in endocytosis and signaling. Science 315, 201–205 10.1126/science.1127085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Deng L., Wang C., Spencer E., Yang L., Braun A., You J., Slaughter C., Pickart C., and Chen Z. J. (2000) Activation of the IκB kinase complex by TRAF6 requires a dimeric ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme complex and a unique polyubiquitin chain. Cell 103, 351–361 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00126-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nijman S. M. B., Luna-Vargas M. P. A., Velds A., Brummelkamp T. R., Dirac A. M. G., Sixma T. K., and Bernards R. (2005) A genomic and functional inventory of deubiquitinating enzymes. Cell 123, 773–786 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Trompouki E., Hatzivassiliou E., Tsichritzis T., Farmer H., Ashworth A., and Mosialos G. (2003) CYLD is a deubiquitinating enzyme that negatively regulates NF-κB activation by TNFR family members. Nature 424, 793–796 10.1038/nature01803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Young A. L., Kellermayer R., Szigeti R., Tészás A., Azmi S., and Celebi J. T. (2006) CYLD mutations underlie Brooke-Spiegler, familial cylindromatosis, and multiple familial trichoepithelioma syndromes. Clin. Genet. 70, 246–249 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00667.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Massoumi R., Kuphal S., Hellerbrand C., Haas B., Wild P., Spruss T., Pfeifer A., Fässler R., and Bosserhoff A. K. (2009) Down-regulation of CYLD expression by Snail promotes tumor progression in malignant melanoma. J. Exp. Med. 206, 221–232 10.1084/jem.20082044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bignell G. R., Warren W., Seal S., Takahashi M., Rapley E., Barfoot R., Green H., Brown C., Biggs P. J., Lakhani S. R., Jones C., Hansen J., Blair E., Hofmann B., Siebert R., et al. (2000) Identification of the familial cylindromatosis tumor suppressor gene, Nat. Genet. 25, 160–165 10.1038/76006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brummelkamp T. R., Nijman S. M. B., Dirac A. M. G., and Bernards R. (2003) Loss of the cylindromatosis tumor suppressor inhibits apoptosis by activating NF-κB activation. Nature 424, 797–801 10.1038/nature01811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bowen S., Gill M., Lee D. A., Fisher G., Geronemus R. G., Vazquez M. E., and Celebi J. T. (2005) Mutations in the CYLD gene in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, familial cylindromatosis, and multiple familial trichoepithelioma: Lack of genotype-phenotype correlation. J. Invest. Dermatol. 124, 919–920 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23688.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sun S.-C. (2010) CYLD: A tumor suppressor deubiquitinatase regulating NF-κB activation and diverse biological processes. Cell Death. Differ. 17, 25–34 10.1038/cdd.2009.43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tokunaga F. (2013) Linear ubiquitination-mediated NF-κB regulation and its related disorders. J. Biochem. 154, 313–323 10.1093/jb/mvt079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Massoumi R. (2010) Ubiquitin chain cleavage: CYLD at work. Trends Biochem. Sci. 35, 392–399 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rajan N., Elliott R. J. R., Smith A., Sinclair N., Swift S., Lord C. J., and Ashworth A. (2014) The cylindromatosis gene product, CYLD, interacts with MIB2 to regulate Notch signaling. Oncotarget 5, 12126–12140 10.18632/oncotarget.2573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Takeuchi T., Adachi Y., and Ohtsuki Y. (2005) Skeletrophin, a novel ubiquitin ligase to the intracellular region of Jagged-2, is aberrantly expressed in multiple myeloma. Am. J. Pathol. 166, 1817–1826 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62491-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stempin C. C., Chi L., Giraldo-Vela J. P., High A. A., Häcker H., and Redecke V. (2011) The E3 ubiquitin ligase mind bomb-2 (MIB2) protein controls B-cell CLL/lymphoma 10 (Bcl10)-dependent NF-κB activation. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 37147–37157 10.1074/jbc.M111.263384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Takahashi H., Uematsu A., Yamanaka S., Imamura M., Nakajima T., Doi K., Yasuoka S., Takahashi C., Takeda H., and Sawasaki T. (2016) Establishment of a wheat cell-free synthesized protein array containing 250 human and mouse E3 ubiquitin ligases to identify novel interaction between E3 ligases and substrate proteins. PLoS One 11, e0156718 10.1371/journal.pone.0156718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kovalenko A., Chable-Bessia C., Cantarella G., Israël A., Wallach D., and Courtois G. (2003) The tumor suppressor CYLD negatively regulates NF-κB signaling by deubiquitination. Nature 424, 801–805 10.1038/nature01802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yano T., Takeda H., Uematsu A., Yamanaka S., Nomura S., Nemoto K., Iwasaki T., Takahashi H., and Sawasaki T. (2016) AGIA tag system based on a high affinity rabbit monoclonal antibody against human dopamine receptor D1 for protein analysis. PLoS One 11, e0156716 10.1371/journal.pone.0156716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wu X., Fukushima H., North B. J., Nagaoka Y., Nagashima K., Deng F., Okabe K., Inuzuka H., and Wei W. (2014) SCFβ-TRCP regulates osteoclastogenesis via promoting CYLD ubiquitination. Oncotarget 5, 4211–4221 10.18632/oncotarget.1971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schlicher L., Wissler M., Preiss F., Brauns-Schubert P., Jakob C., Dumit V., Borner C., Dengjel J., and Maurer U. (2016) SPATA2 promotes CYLD activity and regulates TNF-induced NF-κB signaling and cell death. EMBO Rep. 17, 1485–1497 10.15252/embr.201642592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Aggarwal B. B., Shishodia S., Sandur S. K., Pandey M. K., and Sethi G. (2006) Inflammation and cancer: How hot is the link? Biochem. Pharmacol. 72, 1605–1621 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ditzel H. J. (2004) The K/BxN mouse: A model of human inflammatory arthritis. Trends Mol. Med. 10, 40–45 10.1016/j.molmed.2003.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brand D. D., Latham K. A., and Rosloniec E. F. (2007) Collagen-induced arthritis. Nat. Protoc. 2, 1269–1275 10.1038/nprot.2007.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Inn K.-S., Gack M. U., Tokunaga F., Shi M., Wong L.-Y., Iwai K., and Jung J. U. (2011) Linear ubiquitin assembly complex negatively regulates RIG-I- and TRIM25-mediated type I interferon induction. Mol. Cell 41, 354–365 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.12.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Izzi L., and Attisano L. (2004) Regulation of the TGFβ signaling pathway by ubiquitin-mediated degradation. Oncogene 23, 2071–2078 10.1038/sj.onc.1207412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hu H., and Sun S. C. (2016) Ubiquitin signaling in immune response. Cell Res. 26, 457–483 10.1038/cr.2016.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Reyes-Turcu F. E., Ventii K. H., and Wilkinson K. D. (2009) Regulation and cellular roles of ubiquitin-specific deubiquitinating enzymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 363–397 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.082307.091526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Clague M. J., Coulson J. M., and Urbé S. (2012) Cellular functions of the DUBs. J. Cell Sci. 125, 277–286 10.1242/jcs.090985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Reiley W., Zhang M., and Sun S.-C. (2004) Negative regulation of JNK signaling by the tumor suppressor CYLD. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 55161–55167 10.1074/jbc.M411049200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Friedman C. S., O'Donnell M. A., Legarda-Addison D., Ng A., Cárdenas W. B., Yount J. S., Moran T. M., Basler C. F., Komuro A., Horvath C. M., Xavier R., and Ting A. T. (2008) The tumor suppressor CYLD is a negative regulator of RIG-I-mediated antiviral response. EMBO Rep. 9, 930–936 10.1038/embor.2008.136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ye J. S., Kim N., Lee K. J., Nam Y. R., Lee U., and Joo C. H. (2014) Lysine 63-linked TANK-binding kinase 1 ubiquitination by mindbomb E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 2 is mediated by the mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein. J. Virol. 88, 12765–12776 10.1128/JVI.02037-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Koo B.-K., Yoon M.-J., Yoon K.-J., Im S.-K., Kim Y.-Y., Kim C.-H., Suh P.-G., Jan Y. N., and Kong Y.-Y. (2007) An obligatory role of mind bomb-1 in notch signaling of mammalian development. PLoS One 2, e1221 10.1371/journal.pone.0001221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zinngrebe J., Montinaro A., Peltzer N., and Walczak H. (2014) Ubiquitin in the immune system. EMBO Rep. 15, 28–45 10.1002/embr.201338025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Draber P., Kupka S., Reichert M., Draberova H., Lafont E., de Miguel D., Spilgies L., Surinova S., Taraborrelli L., Hartwig T., Rieser E., Martino L., Rittinger K., and Walczak H. (2015) LUBAC-recruited CYLD and A20 regulate gene activation and cell death by exerting opposing effects on linear ubiquitin in signaling complexes. Cell Rep. 13, 2258–2272 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Feltham R., Jamal K., Tenev T., Liccardi G., Jaco I., Domingues C. M., Morris O., John S. W., Annibaldi A., Widya M., Kearney C. J., Clancy D., Elliott P. R., Glatter T., Qiao Q., Thompson A. J., Nesvizhskii A., Schmidt A., Komander D., Wu H., Martin S., and Meier P. (2018) Mind bomb regulates cell death during TNF signaling by suppressing RIPK1's cytotoxic potential. Cell Rep. 23, 470–484 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Moquin D. M., McQuade T., and Chan F. K.-M. (2013) CYLD deubiquitinates RIP1 in the TNFα-induced necrosome to facilitate kinase activation and programmed necrosis. PLoS One 8, e76841 10.1371/journal.pone.0076841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zuo Y.-G., Xu Y., Wang B., Liu Y.-H., Qu T., Fang K., and Ho M. G. (2007) A novel mutation of CYLD in a Chinese family with multiple familial trichoepithelioma and no CYLD protein expression in the tumor tissue. Br. J. Dermatol. 157, 818–821 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08081.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kazakov D. V., Zelger B., Rütten A., Vazmitel M., Spagnolo D. V., Kacerovska D., Vanecek T., Grossmann P., Sima R., Grayson W., Calonje E., Koren J., Mukensnabl P., Danis D., and Michal M. (2009) Morphologic diversity of malignant neoplasms arising in preexisting spiradenoma, cylindroma, and spiradenocylindroma based on the study of 24 cases, sporadic or occurring in the setting of Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 33, 705–719 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181966762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Almeida S., Maillard C., Itin P., Hohl D., and Huber M. (2008) Five new CYLD mutations in skin appendage tumors and evidence that aspartic acid 681 in CYLD is essential for deubiquitinase activity. J. Invest. Dermatol. 128, 587–593 10.1038/sj.jid.5701045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sima R., Vanecek T., Kacerovska D., Trubac P., Cribier B., Rutten A., Vazmitel M., Spagnolo D. V., Litvik R., Vantuchova Y., Weyers W., Pearce R. L., Pearn J., Michal M., and Kazakov D. V. (2010) Brooke-Spiegler syndrome: Report of 10 patients from 8 families with novel germline mutations: evidence of diverse somatic mutations in the same patient regardless of tumor type. Diagn. Mol. Pathol. 19, 83–91 10.1097/PDM.0b013e3181ba2d96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hu G., Önder M., Gill M., Aksakal B., Öztas M., Gürer M. A., Tok J., and Çelebi M. D. (2003) A novel missense mutation in CYLD in a family with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. J. Invest. Dermatol. 121, 732–734 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12514.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wang F.-X., Yang L.-J., Li M., Zhang S.-L., and Zhu X.-H. (2010) A novel missense mutation of CYLD gene in a Chinese family with multiple familial trichoepithelioma. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 302, 67–70 10.1007/s00403-009-1003-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. España A., García-Amigot F., Aguado L., and García-Foncillas J. (2007) A novel missense mutation in the CYLD gene in a Spanish family with multiple familial trichoepithelioma. Arch. Dermatol. 143, 1209–1210 10.1001/archderm.143.9.1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lv H. L., Huang Y. J., Zhou D., Du Y. F., Zhao X. Y., Liang Y. H., Quan C., Zhang H., Zhou F. S., Gao M., Zhou L., Yang S., and Zhang X. J. (2008) A novel missense mutation of CYLD gene in a Chinese family with multiple familial trichoepithelioma. J. Dermatol. Sci. 50, 143–146 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2007.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zheng G., Hu L., Huang W., Chen K., Zhang X., Yang S., Sun J., Jiang Y., Luo G., and Kong X. (2004) CYLD mutation causes multiple familial trichoepithelioma in three Chinese families. Hum. Mutat. 23, 400 10.1002/humu.9231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tokunaga F., Nishimasu H., Ishitani R., Goto E., Noguchi T., Mio K., Kamei K., Ma A., Iwai K., and Nureki O. (2012) Specific recognition of linear polyubiquitin by A20 zinc finger 7 is involved in NF-κB regulation. EMBO J. 31, 3856–3870 10.1038/emboj.2012.241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hyun T. S., Li L., Oravecz-Wilson K. I., Bradley S. V., Provot M. M., Munaco A. J., Mizukami I. F., Sun H., and Ross T. S. (2004) Hip1-related mutant mice grow and develop normally but have accelerated spinal abnormalities and dwarfism in the absence of HIP1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 4329–4340 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4329-4340.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Takahashi H., Nozawa A., Seki M., Shinozaki K., Endo Y., and Sawasaki T. (2009) A simple and high-sensitivity method for analysis of ubiquitination and polyubiquitination based on wheat cell-free protein synthesis. BMC Plant Biol. 9, 39 10.1186/1471-2229-9-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Yoshida Y., Saeki Y., Murakami A., Kawawaki J., Tsuchiya H., Yoshihara H., Shindo M., and Tanaka K. (2015) A comprehensive method for detecting ubiquitinated substrates using TR-TUBE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 4630–4635 10.1073/pnas.1422313112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Shimizu K., Uematsu A., Imai Y., and Sawasaki T. (2014) Pctaire1/Cdk16 promotes skeletal myogenesis by inducing myoblast migration and fusion. FEBS Lett. 588, 3030–3037 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.05.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Skarnes W. C., Rosen B., West A. P., Koutsourakis M., Bushell W., Iyer V., Mujica A. O., Thomas M., Harrow J., Cox T., Jackson D., Severin J., Biggs P., Fu J., Nefedov M., de Jong P. J., Stewart A. F., and Bradley A. (2011) A conditional knockout resource for the genome-wide study of mouse gene function. Nature 474, 337–342 10.1038/nature10163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Dupé V., Davenne M., Brocard J., Dollé P., Mark M., Dierich A., Chambon P., and Rijli F. M. (1997) In vivo functional analysis of Hoxa-1 3′ retinoic acid response element (3′RARE). Development 124, 399–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kouskoff V., Korganow A.-S., Duchatelle V., Degott C., Benoist C., and Mathis D. (1996) Organ-specific disease provoked by systemic autoimmunity. Cell 87, 811–822 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81989-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sievers F., Wilm A., Dineen D., Gibson T. J., Karplus K., Li W., Lopez R., McWilliam H., Remmert M., Söding J., Thompson J. D., and Higgins D. G. (2011) Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7, 539 10.1038/msb.2011.75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Crooks G. E., Hon G., Chandonia J.-M., and Brenner S. E. (2004) WebLogo: A sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 14, 1188–1190 10.1101/gr.849004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.