Abstract

Background

Diabetes mellitus frequently coexists with heart failure (HF), but few studies have compared the associations between diabetes mellitus and cardiac remodeling, quality of life, and clinical outcomes, according to HF phenotype.

Methods and Results

We compared echocardiographic parameters, quality of life (assessed by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire), and outcomes (1‐year all‐cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and HF hospitalization) between HF patients with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus in the prospective ASIAN‐HF (Asian Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure) Registry, as well as community‐based controls without HF. Adjusted Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess the association of diabetes mellitus with clinical outcomes. Among 5028 patients with HF and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF; EF <40%) and 1139 patients with HF and preserved EF (HFpEF; EF ≥50%), the prevalences of type 2 diabetes mellitus were 40.2% and 45.0%, respectively (P=0.003). In both HFrEF and HFpEF cohorts, diabetes mellitus (versus no diabetes mellitus) was associated with smaller indexed left ventricular diastolic volumes and higher mitral E/e′ ratio. There was a predominance of eccentric hypertrophy in HFrEF and concentric hypertrophy in HFpEF. Patients with diabetes mellitus had lower Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire scores in both HFpEF and HFrEF, with more prominent differences in HFpEF (P interaction<0.05). In both HFpEF and HFrEF, patients with diabetes mellitus had more HF rehospitalizations (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.05–1.54; P=0.014) and higher 1‐year rates of the composite of all‐cause mortality/HF hospitalization (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.05–1.41; P=0.011), with no differences between HF phenotypes (P interaction>0.05).

Conclusions

In HFpEF and HFrEF, type 2 diabetes mellitus is associated with smaller left ventricular volumes, higher mitral E/e′ ratio, poorer quality of life, and worse outcomes, with several differences noted between HF phenotypes.

Clinical Trial Registration

URL: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Unique identifier: NCT01633398.

Keywords: diabetes mellitus, diabetic cardiomyopathy, echocardiography, heart failure, preserved left ventricular function

Subject Categories: Heart Failure; Diabetes, Type 2; Echocardiography

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is associated with smaller left ventricular volumes and higher mitral E/e′ ratio in patients with heart failure.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus impacts negatively on quality of life and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with heart failure.

Distinct differences are noted between heart failure phenotypes.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Primary prevention and treatment interventions are needed to tackle this twin scourge of disease.

Introduction

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus has increased worldwide during the past 3 decades, with the largest projected increases occurring in Asia.1 Diabetes mellitus increases the risk of developing heart failure (HF), and patients with both conditions are known to have particularly poor outcomes.2

Most previous studies of diabetes mellitus and HF have focused on Western populations, and data on the relationship between diabetes mellitus and HF phenotypes in Asia are lacking.2 Knowledge gleaned from Western cohorts may not be readily extrapolated to Asians, particularly in light of recent studies showing distinct differences between Asians and white populations.3, 4

The effect of diabetes mellitus on cardiac remodeling is uncertain, with studies showing potential development of either dilated or restrictive left ventricular (LV) phenotypes with diabetes mellitus.5 Data on how LV remodeling patterns with diabetes mellitus differ between patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) versus those with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) are scarce. We are not aware of any prior study having concurrent comparative echocardiographic findings in normal controls, patients with HFpEF, and patients with HFrEF with and without diabetes mellitus.

Using data from the multinational ASIAN‐HF (Asian Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure) Registry and community‐based controls without HF, we aim to examine the association between type 2 diabetes mellitus and the key domains of cardiac remodeling, quality of life (QoL), and clinical outcomes, in patients with both HFpEF and HFrEF. In addition, we aim to study the interactions between diabetes mellitus and HF phenotype on these domains.

Methods

The study data and materials used to conduct the research cannot be made available to other researchers, for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure, because of the legal restrictions imposed by multinational jurisdictions.

Study Population

Details of the ASIAN‐HF Registry have been published in detail.6 In brief, the ASIAN‐HF Registry is a prospective, observational, multinational registry of Asian patients, aged >18 years, with symptomatic HF (at least one documented episode of decompensated HF in the previous 6 months that resulted in a hospital admission or equivalent treatment). Eligible patients were enrolled from 46 medical centers across 11 Asian regions using uniform protocols and standardized procedures, with all data captured in an electronic database. Data collection included demographic variables, clinical symptoms, functional status, QoL scores, cardiovascular history, and clinical risk factors. Patients in the ASIAN‐HF Registry were recruited in 2 stages: those with HFrEF were enrolled between October 2012 and December 2015, overlapping with recruitment of those with HFpEF, between September 2013 and October 2016. Recruitment of patients with HFpEF started later than the recruitment of patients with HFrEF, for funding reasons. However, the delay was only 1 year. Hence, we do not anticipate substantial shifts in epidemiological features or treatment of patients with HFrEF or HFpEF during this year to bias regional patterns of multimorbidity, although this cannot be entirely excluded.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus was defined as the presence of the clinical diagnosis (fasting plasma glucose ≥7 mmol/L, random plasma glucose ≥11.1 mmol/L, or glycated hemoglobin ≥6.5%) or a self‐reported history of diabetes mellitus and/or receiving antidiabetic therapy at baseline. Transthoracic echocardiography and 12‐lead electrocardiography were performed by protocol at baseline. Patients with HFrEF were defined as those with EF <40%, whereas patients with HFpEF were defined as those with an EF ≥50% on baseline echocardiography. In addition to history of HF decompensation within 6 months and presence of typical symptoms and signs of HF, 99.5% of patients with HFpEF had echocardiographic evidence for diastolic dysfunction (E/e′ ≥13, E′ medial/lateral <9 ms, left atrial (LA) enlargement, or LV hypertrophy [LVH]).7 Patients were followed up for the outcomes of death and hospitalization, which were independently adjudicated by a clinical end point committee using prespecified criteria.6

Community‐based controls without HF (n=965, 84 with diabetes mellitus) were recruited as part of the control arm of the SHOP (Singapore Heart Failure Outcomes and Phenotypes) study.8 Controls were free‐living adults without HF, identified from the general community of Singapore, using random sampling by door‐to‐door census of all residents in 5 designated precincts of Singapore. Controls underwent a detailed clinical examination as well as echocardiography. Both patients and controls provided informed consent, and ethics approvals were obtained from the local Institutional Review Board of each participating center.

Echocardiography

The echocardiography protocol has been published.6 Briefly, echocardiography was performed at each center according to international guidelines, with a core laboratory providing detailed imaging protocols, training, oversight, and quality assurance, ensuring the accuracy and reproducibility of results.6 Echocardiographic parameters captured included LV dimensions and volume, LVEF, wall thickness, LA volumes, and LV mass. These were indexed to body surface area and measured according to published guidelines.9 Relative wall thickness (RWT) was calculated as follows: (2×diastolic posterior wall thickness)/diastolic LV internal diameter. LVH was defined as indexed LV mass index >115 g/m2 in men and >95 g/m2 in women.9 Normal cardiac geometry was defined as having no LVH and an RWT ≤0.42. Abnormal LV geometry was categorized as concentric remodeling (no LVH and RWT >0.42), eccentric hypertrophy (LVH and RWT ≤0.42), and concentric hypertrophy (LVH and RWT >0.42), as per guidelines.9

Health‐Related QoL

The Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) was used to assess the health‐related QoL. The KCCQ is a 23‐item, self‐administered questionnaire assessing the domains of physical function, symptoms, social function, self‐efficacy and knowledge, and QoL; it is validated in multiple HF‐related disease states and in several languages.10 An overall summary score can be derived from each domain, with scores ranging from 0 to 100 (higher scores indicate better health status).10 Non–English‐speaking participants used certified versions of the KCCQ translated into their native languages.10

Outcomes

The principal outcomes evaluated were all‐cause mortality and the composite of all‐cause mortality or HF hospitalization, each at 1 year. Secondary outcomes included cardiovascular mortality and HF hospitalization at 1 year. Causes of cardiovascular death were further subclassified as attributable to sudden cardiac death (SCD), HF, acute myocardial infarction, stroke, other or presumed cardiovascular death.

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were performed separately in patients with HFrEF and HFpEF. Descriptive statistics were used to present baseline characteristics in patients with and without diabetes mellitus and included means and SDs, numbers and percentages, or medians and interquartile ranges. Correspondingly, differences between patients with and without diabetes mellitus were compared by Student t test, χ2 test, or Wilcoxon rank sum test, as appropriate. Multivariable logistic regression was performed to identify independent demographic and clinical associates of diabetes mellitus, including variables significant on univariable analysis and a priori selection of variables based on clinical significance. These variables included the following: age, sex, ethnicity, regional income, heart rate, body mass index (BMI), chronic kidney disease, hypertension, history of coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, prior stroke, and peripheral arterial disease. KCCQ scores were similarly adjusted for demographic factors, clinical variables, and medications and presented as adjusted (marginal) means and associated SEMs. Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess the association of diabetes mellitus with clinical outcomes and further adjusted for confounders in the overall group. No violation of the proportionality hazards assumption for Cox models was observed with the use of statistical tests and graphical diagnostics (based on the Schoenfeld residuals). Competing risks of death were accounted for in the analysis of HF hospitalizations. The time to outcome in Cox regression was defined as the time from baseline visit to the event of interest (eg, death or hospitalization for HF) and censored at the last visit or 1 year, whichever was earlier. Cox models were adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, regional income, enrollment type, HF group, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, BMI, history of coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, peripheral arterial disease, chronic kidney disease, retinopathy, neuropathy, obstructive pulmonary disease, and use of HF medications.

The associations of QoL, echocardiographic features, and outcomes with diabetes mellitus were tested for interactions to assess if these relationships differed between HFrEF and HFpEF. Interaction analyses were also performed between diabetes mellitus and the following: (1) ethnicity as a factor variable, (2) BMI as a continuous variable, and (3) national income level as a factor variable for the respective outcomes, where national income level was as defined by the World Health Organization (lower: Indonesia, Philippines, and India; middle: China, Thailand, and Malaysia; higher: Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan). Stratified analyses were performed if interactions were significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata, version 14.0 (StataCorp). P≤0.05 was considered statistically significant; all tests were performed 2 sided.

Results

Prevalence of Diabetes Mellitus

Of a total of 6167 patients in the ASIAN‐HF Registry, 5028 had HFrEF (mean age, 60.0±13.1 years; 78.2% men; LVEF, 27.3±7.1%) and 1139 had HFpEF (mean age, 68.7±12.3 years; 50.3% men; LVEF, 61.0±7.2%). The prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus was higher in those with HFpEF (45.0%) compared with those with HFrEF (40.2%) (P=0.003), and the average duration of diabetes mellitus was longer in those with HFpEF (12.0±8.3 years) compared with those with HFrEF (9.8±8.2 years) (P<0.001). In both HFrEF and HFpEF, patients with diabetes mellitus were more likely to be from Southeast Asia and the high‐income regions (Table 1). Prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus was lowest in China (at 22.8%) and highest in Singapore (at 58.2%) and Hong Kong (at 56.9%). Among 965 community‐based controls without HF (mean age, 57.3±10.3 years; 48.7% men), 8.7% (n=84) had diabetes mellitus.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

| Characteristics | HFrEF | HFpEF | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Diabetes Mellitus | No Diabetes Mellitus | Total | Diabetes Mellitus | No Diabetes Mellitus | P Value | ||

| No. | 5028 | 2021 | 3007 | … | 1139 | 513 | 626 | … |

| Duration of diabetes mellitus | … | 9.8 (8.2)a | … | … | … | 12.0 (8.3)b | … | … |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age, y | 60.0 (13.1) | 61.9 (10.9) | 58.8 (14.3) | <0.001 | 68.7 (12.3) | 69.4 (10.8) | 68.1 (13.4) | 0.081 |

| Women | 1095 (21.8) | 425 (21.0) | 670 (22.3) | 0.290 | 566 (49.7) | 262 (51.1) | 304 (48.6) | 0.400 |

| Ethnicity | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Chinese | 1513 (30.1) | 618 (30.6) | 895 (29.8) | 579 (50.8) | 271 (52.8) | 308 (49.2) | ||

| Indian | 1567 (31.2) | 649 (32.1) | 918 (30.5) | 275 (24.1) | 102 (19.9) | 173 (27.6) | ||

| Malay | 790 (15.7) | 391 (19.3) | 399 (13.3) | 124 (10.9) | 89 (17.3) | 35 (5.6) | ||

| Japanese | 523 (10.4) | 161 (8.0) | 362 (12.0) | 117 (10.3) | 37 (7.2) | 80 (12.8) | ||

| Korean | 304 (6.0) | 91 (4.5) | 213 (7.1) | 35 (3.1) | 6 (1.2) | 29 (4.6) | ||

| Thai | 167 (3.3) | 58 (2.9) | 109 (3.6) | 4 (0.4) | 4 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Filipino | 46 (0.9) | 13 (0.6) | 33 (1.1) | 4 (0.4) | 3 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | ||

| Indigenous | 105 (2.1) | 34 (1.7) | 71 (2.4) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Others | 13 (0.3) | 6 (0.3) | 7 (0.2) | |||||

| Geographical region | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Northeast Asia | 1605 (31.9) | 511 (25.3) | 1094 (36.4) | 531 (46.6) | 209 (40.7) | 322 (51.4) | ||

| South Asia | 1361 (27.1) | 493 (24.4) | 868 (28.9) | 220 (19.3) | 62 (12.1) | 158 (25.2) | ||

| Southeast Asia | 2062 (41.0) | 1017 (50.3) | 1045 (34.7) | 388 (34.1) | 242 (47.2) | 146 (23.3) | ||

| Economic development | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Low income | 1721 (34.2) | 616 (30.5) | 1105 (36.8) | 239 (21.0) | 72 (14.0) | 167 (26.7) | ||

| Middle income | 1155 (23.0) | 424 (21.0) | 731 (24.3) | 73 (6.4) | 45 (8.8) | 28 (4.5) | ||

| High income | 2152 (42.8) | 981 (48.5) | 1171 (38.9) | 827 (72.6) | 396 (77.2) | 431 (68.9) | ||

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||||

| NYHA | 0.036 | 0.140 | ||||||

| Class I | 588 (12.8) | 242 (13.2) | 346 (12.5) | 153 (16.3) | 62 (13.9) | 91 (18.6) | ||

| Class II | 2406 (52.3) | 938 (51.3) | 1468 (53.0) | 556 (59.3) | 265 (59.3) | 291 (59.4) | ||

| Class III | 1324 (28.8) | 555 (30.3) | 769 (27.7) | 202 (21.6) | 107 (23.9) | 95 (19.4) | ||

| Class IV | 282 (6.1) | 94 (5.1) | 188 (6.8) | 26 (2.8) | 13 (2.9) | 13 (2.6) | ||

| Shortness of breath on exertion | 3770 (75.0) | 1485 (73.6) | 2285 (76.0) | 0.050 | 683 (60.0) | 334 (65.1) | 349 (55.8) | 0.001 |

| Shortness of breath at rest | 926 (18.4) | 399 (19.8) | 527 (17.5) | 0.046 | 135 (11.9) | 72 (14.0) | 63 (10.1) | 0.039 |

| Reduction in exercise tolerance | 3531 (70.3) | 1376 (68.2) | 2155 (71.7) | 0.008 | 673 (59.1) | 334 (65.1) | 339 (54.2) | <0.001 |

| Nocturnal cough | 923 (18.4) | 374 (18.5) | 549 (18.3) | 0.820 | 148 (13.0) | 77 (15.0) | 71 (11.3) | 0.067 |

| Orthopnea | 1135 (22.6) | 492 (24.4) | 643 (21.4) | 0.013 | 174 (15.3) | 94 (18.3) | 80 (12.8) | 0.010 |

| Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea | 955 (19.0) | 404 (20.0) | 551 (18.3) | 0.140 | 120 (10.5) | 61 (11.9) | 59 (9.4) | 0.180 |

| Elevated jugular venous pressure | 777 (15.5) | 377 (18.7) | 400 (13.3) | <0.001 | 118 (10.4) | 71 (13.8) | 47 (7.5) | >0.001 |

| S3 present | 501 (10.0) | 199 (9.8) | 302 (10.1) | 0.810 | 23 (2.0) | 10 (1.9) | 13 (2.1) | 0.880 |

| Peripheral edema | 1186 (23.6) | 582 (28.8) | 604 (20.1) | <0.001 | 374 (32.9) | 213 (41.6) | 161 (25.7) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary rales present | 839 (16.7) | 405 (20.0) | 434 (14.4) | <0.001 | 175 (15.4) | 105 (20.5) | 70 (11.2) | <0.001 |

| Hepatomegaly | 277 (5.5) | 112 (5.5) | 165 (5.5) | 0.940 | 28 (2.5) | 10 (1.9) | 18 (2.9) | 0.320 |

| Hepatojugular reflux positive | 436 (8.7) | 198 (9.8) | 238 (7.9) | 0.021 | 71 (6.2) | 43 (8.4) | 28 (4.5) | 0.007 |

| LV ejection fraction, % | 27.3 (7.1) | 27.4 (7.1) | 27.2 (7.1) | 0.300 | 61.0 (7.2) | 60.9 (7.3) | 61.1 (7.2) | 0.650 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 118.3 (20.1) | 120.9 (20.2) | 116.6 (19.8) | <0.001 | 132.2 (22.1) | 135.2 (22.2) | 129.8 (21.7) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 72.4 (12.6) | 72.3 (12.3) | 72.4 (12.8) | 0.690 | 72.5 (12.9) | 71.3 (12.2) | 73.5 (13.4) | 0.004 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 79.6 (16.2) | 80.2 (16.0) | 79.2 (16.3) | 0.029 | 76.1 (15.2) | 76.3 (13.9) | 76.0 (16.2) | 0.770 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.9 (5.1) | 25.5 (4.9) | 24.4 (5.2) | <0.001 | 27.1 (6.0) | 28.4 (6.1) | 26.0 (5.8) | <0.001 |

| BMI categories, kg/m2 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 320 (6.7) | 77 (4.0) | 243 (8.5) | 29 (3.2) | 3 (0.7) | 26 (5.3) | ||

| Normal (18.5–23) | 1501 (31.3) | 538 (27.9) | 963 (33.6) | 194 (21.3) | 67 (16.1) | 127 (25.7) | ||

| Overweight (23–27.5) | 1844 (38.4) | 774 (40.1) | 1070 (37.3) | 325 (35.8) | 140 (33.7) | 185 (37.4) | ||

| Obese (≥27.5) | 1134 (23.6) | 542 (28.1) | 592 (20.6) | 361 (39.7) | 205 (49.4) | 156 (31.6) | ||

| eGFR, mL/min /1.73 m2 | 65.9 (27.8) | 60.9 (27.8) | 69.4 (27.3) | <0.001 | 61.5 (28.8) | 53.9 (27.4) | 68.6 (28.2) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||||

| Chronic kidney disease (eGFR [mL/min/1.73 m2] <60) | 1745 (44.0) | 884 (53.3) | 861 (37.4) | <0.001 | 461 (50.2) | 268 (60.8) | 193 (40.5) | <0.001 |

| Ischemic cause of HF | 2348 (46.7) | 1244 (61.6) | 1104 (36.8) | <0.001 | 350 (30.9) | 194 (38.0) | 156 (25.0) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 2580 (51.3) | 1375 (68.1) | 1205 (40.1) | <0.001 | 811 (71.2) | 438 (85.4) | 373 (59.6) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 2498 (49.7) | 1301 (64.4) | 1197 (39.8) | <0.001 | 335 (29.5) | 208 (40.5) | 127 (20.4) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 910 (18.1) | 327 (16.2) | 583 (19.4) | 0.004 | 326 (28.6) | 133 (25.9) | 193 (30.8) | 0.068 |

| Prior stroke | 325 (6.5) | 173 (8.6) | 152 (5.1) | <0.001 | 95 (8.3) | 47 (9.2) | 48 (7.7) | 0.360 |

| Liver disease | 168 (3.3) | 64 (3.2) | 104 (3.5) | 0.570 | 23 (2.0) | 13 (2.5) | 10 (1.6) | 0.260 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 167 (3.3) | 107 (5.3) | 60 (2.0) | <0.001 | 23 (2.0) | 16 (3.1) | 7 (1.1) | 0.016 |

| Microvascular complications | ||||||||

| Nephropathy | … | 298 (14.8) | … | … | … | 113 (22.0) | … | … |

| Retinopathy | … | 187 (9.3) | … | … | … | 64 (12.5) | … | … |

| Neuropathy | … | 117 (5.8) | … | … | … | 47 (9.2) | … | … |

| COPD | 418 (8.3) | 158 (7.8) | 260 (8.7) | 0.290 | 104 (9.1) | 50 (9.7) | 54 (8.6) | 0.510 |

| Smoking, ever | 2267 (45.1) | 942 (46.6) | 1325 (44.1) | 0.077 | 259 (22.8) | 120 (23.4) | 139 (22.2) | 0.620 |

| Alcohol, ever | 1467 (29.2) | 564 (27.9) | 903 (30.0) | 0.100 | 170 (15.0) | 81 (15.9) | 89 (14.2) | 0.440 |

| Medications | ||||||||

| ACEI or ARB | 3705 (75.2) | 1439 (72.3) | 2266 (77.2) | <0.001 | 669 (66.8) | 327 (69.1) | 342 (64.7) | 0.130 |

| β Blockers | 3798 (77.1) | 1542 (77.5) | 2256 (76.9) | 0.610 | 676 (67.5) | 326 (68.9) | 350 (66.2) | 0.350 |

| Diuretics | 4038 (82.0) | 1693 (85.1) | 2345 (79.9) | <0.001 | 709 (70.8) | 356 (75.3) | 353 (66.7) | 0.003 |

| MRA | 2878 (58.4) | 1079 (54.2) | 1799 (61.3) | <0.001 | 214 (21.4) | 76 (16.1) | 138 (26.1) | <0.001 |

| Antidiabetic medications | … | 1307 (66.5) | … | … | … | 335 (68.4) | … | … |

| Metformin | … | 692 (35.2) | … | … | … | 154 (31.4) | … | … |

| Sulfonylureas | … | 705 (35.9) | … | … | … | 170 (34.7) | … | … |

| Gliptins | … | 227 (11.6) | … | … | … | 76 (15.5) | … | … |

| α‐Glucosidase inhibitors | … | 134 (6.8) | … | … | … | 24 (4.9) | … | … |

| Meglitinides | … | 24 (1.2) | … | … | … | 8 (1.6) | … | … |

| Insulins | … | 327 (16.6) | … | … | … | 103 (21.0) | … | … |

Data are given as number (percentage) or mean (SD). ACEI indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; bpm, beats per minute; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; HFpEF, HF with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, HF with reduced ejection fraction; LV, left ventricular; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Duration of diabetes mellitus reported in n=1339 patients with HFrEF.

Duration of diabetes mellitus reported in n=344 patients with HFpEF.

Baseline Correlates of Diabetes Mellitus

In HFrEF, but not HFpEF (Table 1), patients with diabetes mellitus were older than those without diabetes mellitus. In both HFpEF and HFrEF, patients with diabetes mellitus had a higher prevalence of overweight/obesity than those without diabetes mellitus. Obesity was more prevalent in those with HFpEF and diabetes mellitus than in those with HFrEF and diabetes mellitus (49.4% versus 28.1%; P<0.001). Of note, 31.9% of patients with HFrEF (versus 16.8% of patients with HFpEF) with diabetes mellitus were either normal weight or underweight. In both HFrEF and HFpEF, patients with diabetes mellitus also had a higher prevalence of chronic kidney disease, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and peripheral arterial disease, and were more likely to present with signs and symptoms of HF, compared with those without diabetes mellitus. Yet, compared with patients without diabetes mellitus, those with diabetes mellitus were less likely to be prescribed a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (in HFrEF and HFpEF) and an angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin II receptor blocker (in HFrEF), but more likely to be given diuretics and as likely to be prescribed β‐blockers (in HFrEF and HFpEF). For anti–diabetes mellitus therapy, the most commonly used medications in both HFrEF and HFpEF were metformin, a sulfonylurea, insulin, and a dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitor. Table 2 shows the variables independently correlated with diabetes mellitus in HFrEF and HFpEF. In HFrEF, positive correlates included the following: older age, Indian or Malay ethnicity, dwelling in a middle‐/high‐income region, higher BMI, presence of chronic kidney disease, hypertension, coronary artery disease, peripheral arterial disease, and prior stroke. In contrast, patients of Japanese or Korean descent (versus Chinese) and those with atrial fibrillation were negatively associated with diabetes mellitus in HFrEF. Independent correlates of diabetes mellitus in HFpEF included the following: Indian or Malay ethnicity, dwelling in a high‐income region, higher BMI, and presence of chronic kidney disease, hypertension, or coronary artery disease.

Table 2.

Clinical Correlates of Diabetes Mellitus

| Variable | HFrEF | HFpEF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI)a | P Value | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI)a | P Value | |

| Age, y | 1.011 (1.004–1.017) | 0.002 | 0.999 (0.984–1.016) | 0.745 |

| Women | 1.10 (0.92–1.32) | 0.297 | 0.99 (0.71–1.39) | 0.953 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Chinese | 1.00 (Reference) | ··· | 1.00 (Reference) | ··· |

| Indian | 2.86 (2.13–3.84) | <0.001 | 1.98 (0.96–4.13) | 0.066 |

| Malay | 1.96 (1.54–2.51) | <0.001 | 2.53 (1.39–4.60) | 0.002 |

| Japanese/Korean | 0.66 (0.53–0.82) | <0.001 | 0.64 (0.39–1.05) | 0.076 |

| Economic development | ||||

| Low income | 1.00 (Reference) | ··· | 1.00 (Reference) | ··· |

| Middle income | 1.64 (1.22–2.21) | 0.001 | 1.66 (0.52–5.32) | 0.393 |

| High income | 3.01 (2.28–3.97) | <0.001 | 3.06 (1.39–6.73) | 0.005 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 1.008 (1.003–1.013) | 0.001 | 0.999 (0.988–1.011) | 0.928 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 1.042 (1.027–1.058) | <0.001 | 1.051 (1.020–1.083) | 0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.48 (1.27–1.72) | <0.001 | 1.86 (1.32–2.61) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 2.32 (2.00–2.69) | <0.001 | 2.64 (1.72–4.06) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 2.21 (1.89–2.57) | <0.001 | 1.92 (1.33–2.76) | 0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.78 (0.65–0.95) | 0.012 | 0.76 (0.53–1.10) | 0.149 |

| Prior stroke | 1.34 (1.01–1.76) | 0.039 | 0.66 (0.37–1.19) | 0.167 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 1.87 (1.27–2.76) | 0.002 | 2.88 (0.71–11.7) | 0.139 |

Bpm indicates beats per minute; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

Adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, regional income, heart rate, body mass index, chronic kidney disease, hypertension, history of coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, prior stroke, and peripheral arterial disease.

Diabetes Mellitus and Cardiac Remodeling

Among controls without HF, diabetes mellitus was associated with thicker LV walls, smaller indexed LV end‐diastolic and end‐systolic volumes, higher E/e′ ratio, and greater prevalence of abnormal LV geometry (concentric LV remodeling, concentric hypertrophy, and eccentric hypertrophy), compared with those without diabetes mellitus (Table 3).

Table 3.

Echocardiographic Findings by Diabetic Status

| Variable | HFrEF | HFpEF | Controls | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes Mellitus | No Diabetes Mellitus | P Value | Diabetes Mellitus | No Diabetes Mellitus | P Value | Diabetes Mellitus | No Diabetes Mellitus | P Value | |

| Echocardiographic characteristics | |||||||||

| LV ED dimension, mm | 60 (55–66) | 62 (56–69) | <0.001 | 47 (43–52) | 47 (44–53) | 0.230 | 47 (45–49) | 47 (44–50) | 0.860 |

| LV ES dimension, mm | 51 (45–57) | 53 (46–60) | <0.001 | 30 (27–34) | 30 (27–34) | 0.520 | 28 (26–30) | 28 (25–31) | 0.550 |

| Indexed LV ED volume, mL/m2 | 91 (73–114) | 103 (82–129) | <0.001 | 50 (39–65) | 55 (43–72) | 0.003 | 48 (43–58) | 54 (45–64) | <0.001 |

| Indexed LV ES volume, mL/m2 | 65 (49–84) | 74 (55–98) | <0.001 | 21 (16–31) | 23 (16–33) | 0.130 | 17 (15–22) | 20 (16–24) | 0.014 |

| LV ejection fraction | 28 (22–33) | 28 (22–33) | 0.340 | 60 (55–65) | 60 (55–65) | 0.650 | 63 (61–66) | 64 (61–67) | 0.880 |

| E/e′ ratio | 20.4 (15.0–28.0) | 17.0 (12.7–24.5) | <0.001 | 16.7 (13.1–21.8) | 14.3 (10.9–18.2) | <0.001 | 11.0 (9.2–12.9) | 9.2 (7.7–11.2) | <0.001 |

| IVSD, mm | 9.0 (8.0–11.0) | 9.0 (8.0–10.0) | <0.001 | 11.0 (9.5–12.0) | 10.0 (9.0–12.0) | <0.001 | 10.0 (8.5–11.0) | 9.0 (8.0–10.0) | <0.001 |

| PWTD, mm | 9.0 (8.0–10.8) | 9.0 (8.0–10.0) | 0.230 | 11.0 (9.0–12.0) | 10.0 (9.0–12.0) | 0.003 | 9.0 (8.0–10.0) | 8.0 (7.0–9.0) | <0.001 |

| Indexed LV mass, g/m2 | 128 (104–155) | 135 (110–170) | <0.001 | 102 (83–128) | 102 (85–130) | 0.520 | 84 (76–99) | 79 (67–93) | 0.001 |

| Relative wall thickness | 0.31 (0.26–0.37) | 0.30 (0.25–0.35) | <0.001 | 0.44 (0.38–0.53) | 0.43 (0.36–0.50) | <0.001 | 0.40 (0.34–0.43) | 0.36 (0.31–0.41) | <0.001 |

| Indexed LAV, mL/m2 | 39 (27–51) | 37 (23–53) | 0.032 | 31 (21–44) | 39 (27–54) | <0.001 | 26 (22–31) | 27 (23–30) | 0.750 |

| LVH, n (%) | 1014 (66.4) | 1716 (73.5) | <0.001 | 154 (46.4) | 168 (47.7) | 0.730 | 20 (24.1) | 93 (10.6) | <0.001 |

| Increased RWT (>0.42), n (%) | 217 (13.7) | 232 (9.6) | <0.001 | 250 (60.1) | 230 (51.1) | 0.008 | 28 (33.3) | 171 (19.5) | 0.003 |

| LV geometry, n (%) | 0.034 | <0.001 | |||||||

| No remodeling | 455 (29.8) | 562 (24.1) | <0.001 | 88 (26.5) | 103 (29.3) | 46 (55.4) | 647 (73.7) | ||

| Concentric remodeling | 57 (3.7) | 58 (2.5) | 90 (27.1) | 81 (23.0) | 17 (20.5) | 138 (15.7) | |||

| Concentric hypertrophy | 153 (10.0) | 163 (7.0) | 103 (31.0) | 88 (25.0) | 10 (12.0) | 33 (3.8) | |||

| Eccentric hypertrophy | 861 (56.4) | 1553 (66.5) | 51 (15.4) | 80 (22.7) | 10 (12.0) | 60 (6.8) | |||

Data are given as median (interquartile range) for continuous variables. ED indicates end diastolic; ES, end systolic; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; IVSD, interventricular septal thickness in diastole; LAV, left atrial volume; LV, left ventricular; LVH, LV hypertrophy; PWTD, posterior wall thickness in diastole; RWT, relative wall thickness.

Among patients with HFrEF, diabetes mellitus (versus no diabetes mellitus) was associated with smaller indexed LV end‐diastolic and end‐systolic volumes, a higher E/e′ ratio, but similar LV wall thickness. These associations persisted after correcting for age, sex, ethnicity, and hypertension (P<0.001 for indexed LV end‐diastolic and end‐systolic volumes and E/e′ ratio; P=0.434 for LV wall thickness). The most common LV geometry present in patients with HFrEF was eccentric hypertrophy. There were no significant interactions between income level (P=0.526), ethnicity (P=0.580), or BMI (P=0.195) with diabetes mellitus on its association with LV geometry.

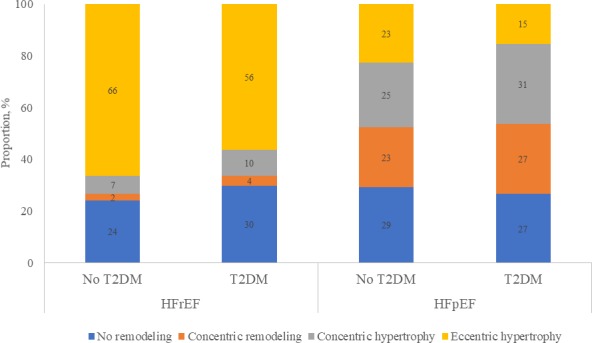

Among patients with HFpEF, diabetes mellitus (versus no diabetes mellitus) was also associated with a thicker LV wall, smaller indexed LV end‐diastolic volumes, and higher mitral E/e′ ratio but smaller indexed LA volumes. These associations persisted after adjusting for the confounders above (P=0.037, P=0.017, P=0.029, and P=0.002 for LV wall thickness, indexed LV end‐diastolic volumes, E/e′ ratio, and indexed LA volume, respectively). The predominant geometry was concentric hypertrophy. There were no significant interactions between income level (P=0.567), ethnicity (P=0.763), or BMI (P=0.197) with diabetes mellitus on its association with LV geometry (Table 3 and Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Left ventricular geometry by heart failure (HF) type and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). HFpEF indicates HF with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, HF with reduced ejection fraction.

Diabetes Mellitus and Health‐Related QoL

Compared with those without diabetes mellitus, patients with diabetes mellitus in both HF phenotypic groups had worse QoL (lower physical limitation score, symptom burden and total symptom score, social limitation, and clinical summary and overall summary KCCQ scores) (Table 4). There were significant interactions between diabetes mellitus and HF phenotype for physical limitation score (P interaction=0.002), QoL score (P interaction=0.001), social limitation (P interaction=0.001), clinical summary score (P interaction=0.006), and overall summary score (P interaction=0.001), indicating that the extent to which diabetes mellitus affected these QoL domains differed by HF phenotype. For the clinical and overall summary scores, scores were lower in those with diabetes mellitus (compared with those without diabetes mellitus) in both HFrEF and HFpEF, with more prominent differences in HFpEF.

Table 4.

KCCQ Scores by Diabetic Status

| Quality‐of‐Life Domains | P interaction (Diabetes Mellitus×HF Group) | HFrEF | HFpEF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes Mellitus | No Diabetes Mellitus | P Value | Diabetes Mellitus | No Diabetes Mellitus | P Value | ||

| Physical limitation score | 0.002 | 66.5 (0.6) | 68.8 (0.5) | 0.007 | 70.6 (1.2) | 77.8 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Symptom stability score | 0.048 | 63.1 (0.7) | 63.6 (0.6) | 0.597 | 56.4 (1.4) | 59.3 (1.3) | 0.139 |

| Symptom frequency score | 0.141 | 66.6 (0.7) | 69.4 (0.5) | 0.001 | 68.0 (1.5) | 73.0 (1.3) | 0.014 |

| Symptom burden score | 0.054 | 70.1 (0.6) | 72.2 (0.5) | 0.015 | 75.1 (1.2) | 80.0 (1.1) | 0.004 |

| Total symptom score | 0.081 | 68.3 (0.6) | 70.8 (0.5) | 0.003 | 71.6 (1.3) | 76.5 (1.1) | 0.005 |

| Self‐efficacy score | 0.050 | 64.3 (0.7) | 64.8 (0.5) | 0.584 | 65.4 (1.4) | 68.4 (1.3) | 0.124 |

| Quality‐of‐life score | 0.001 | 55.8 (0.6) | 56.7 (0.5) | 0.259 | 64.4 (1.2) | 69.8 (1.1) | 0.001 |

| Social limitation score | 0.001 | 59.8 (0.8) | 63.1 (0.7) | 0.003 | 70.2 (1.6) | 79.5 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| Overall summary score | 0.001 | 62.8 (0.6) | 65.0 (0.4) | 0.004 | 69.1 (1.1) | 75.8 (1.0) | <0.001 |

| Clinical summary score | 0.006 | 67.5 (0.6) | 69.9 (0.4) | 0.001 | 70.9 (1.1) | 77.0 (1.0) | <0.001 |

Data are presented as adjusted mean (SE). Adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, regional income, hypertension, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, ejection fraction, obstructive pulmonary disease, atrial fibrillation, peripheral arterial disease, coronary artery disease, educational status, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers, β blockers, and diuretics. HF indicates heart failure; HFpEF, HF with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, HF with reduced ejection fraction; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire.

Diabetes Mellitus and Clinical Outcomes

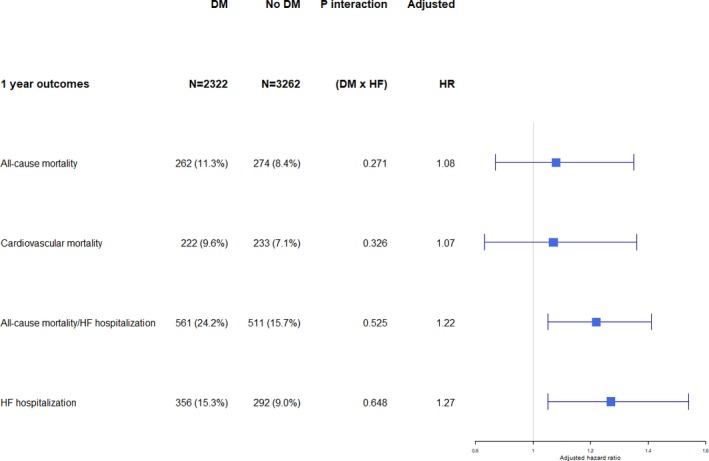

Of 6167 patients, 5584 (90.5%) had outcome data available, whereas 583 (9.5%) were lost to follow‐up. Compared with patients without diabetes mellitus, those with type 2 diabetes mellitus had a higher 1‐year composite of all‐cause mortality/HF hospitalizations (hazard ratio [HR], 1.63; 95% CI, 1.45–1.84; P<0.001; and adjusted HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.05–1.41; P=0.011) on univariable and multivariable analysis, respectively. There was higher 1‐year overall mortality (HR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.16–1.62; P<0.001), but this association was attenuated in multivariable analysis (adjusted HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.87–1.35; P=0.473). For secondary outcomes, the findings for cardiovascular mortality were similar to the above results on overall mortality. However, patients with diabetes mellitus (versus no diabetes mellitus) had a higher risk of HF rehospitalization at 1 year (adjusted HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.05–1.54; P=0.014). HF phenotype did not modify these relationships (P interaction>0.05). SCD and HF death were the most common modes of cardiovascular death among those with diabetes mellitus (26.3% for SCD death, and 20.1% for HF death), as well as those without diabetes mellitus (30.6% SCD death, and 26.0% for HF death), with no difference between phenotypes (P interaction>0.05) (Table 5 and Figure 2.

Table 5.

Clinical Outcomes

| 1‐y Outcomes | No. (%) of Events | Crude Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | P interaction (DM×HF Group) | Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI)a | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DM (N=2322) | No DM (N=3262) | ||||||

| All‐cause mortality | 262 (11.3) | 274 (8.4) | 1.37 (1.16–1.62) | <0.001 | 0.271 | 1.08 (0.87–1.35) | 0.473 |

| HFrEF | 235/1849 | 242/2680 | … | … | … | ||

| HFpEF | 27/473 | 32/582 | … | … | … | ||

| Cardiovascular mortality | 222 (9.6) | 233 (7.1) | 1.36 (1.13–1.64) | 0.001 | 0.326 | 1.07 (0.83–1.36) | 0.603 |

| HFrEF | 203/1849 | 210/2680 | … | … | … | ||

| HFpEF | 19/473 | 23/582 | … | … | … | ||

| All‐cause mortality/HF hospitalizations | 561 (24.2) | 511 (15.7) | 1.63 (1.45–1.84) | <0.001 | 0.525 | 1.22 (1.05–1.41) | 0.011 |

| HFrEF | 491/1849 | 451/2680 | … | … | … | ||

| HFpEF | 70/473 | 60/582 | … | … | … | ||

| HF hospitalizations | 356 (15.3) | 292 (9.0) | 1.79 (1.53–2.09) | <0.001 | 0.648 | 1.27 (1.05–1.54) | 0.014 |

| HFrEF | 306/1849 | 260/2680 | … | … | … | ||

| HFpEF | 50/473 | 32/582 | … | … | … | ||

DM indicates diabetes mellitus; HF, heart failure; HFpEF, HF with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, HF with reduced ejection fraction.

DM, adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, regional income, enrollment type, HF group, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, body mass index, history of coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, peripheral arterial disease, chronic kidney disease, retinopathy, neuropathy, obstructive pulmonary disease, and use of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers, betablockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, and diuretics.

Figure 2.

Survival by type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) status for various outcomes at 1 year. HF indicates heart failure; HR, hazard ratio.

Discussion

We provide the first multinational prospective data from Asia describing the association between diabetes mellitus and key aspects of HF, including cardiac remodeling, QoL, and clinical outcomes, among patients with HFpEF and HFrEF. Our main findings were as follows: (1) The prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus was high among Asian patients with HF, especially those with HFpEF, with notable regional variation. Different correlates of diabetes mellitus were noted for both HFpEF and HFrEF. (2) Type 2 diabetes mellitus was associated with smaller indexed LV diastolic volumes and higher LV filling pressure (higher mitral E/e′ ratio) compared with patients without diabetes mellitus, in both HFrEF and HFpEF. However, there were differences in cardiac remodeling, with predominance of eccentric hypertrophy in HFrEF and concentric hypertrophy in HFpEF. (3) Compared with patients without diabetes mellitus, those with diabetes mellitus had worse QoL, with the difference more prominent in HFpEF than HFrEF, at least for some KCCQ domains. (4) Type 2 diabetes mellitus was associated with a higher risk of the composite outcome of all‐cause mortality or HF hospitalization at 1 year, driven mainly by a higher rate of HF hospitalization. The relationships between diabetes mellitus and outcome were similar in HFrEF and HFpEF.

Cardiac Remodeling

Among controls without HF, diabetes mellitus was associated with greater LV wall thickness and abnormal LV cardiac remodeling. Similar findings have been described in several population‐based studies.11 Several explanatory mechanisms have been postulated, including the prohypertrophic effects of insulin, insulin growth factor‐1, and insulin resistance.12 In the initial insulin‐resistant phase of diabetes mellitus, circulating insulin levels are increased. Insulin is known to directly stimulate cardiomyocyte growth13 and indirectly via binding to the insulin growth factor‐1 receptor.14 Insulin growth factor‐1 itself is known to stimulate the growth of cardiac myocytes through induction of cardiac protein synthesis.15 We also found greater LV diastolic dysfunction (higher mitral E/e′ ratio) in controls with diabetes mellitus compared with those without diabetes mellitus, consistent with other non‐HF diabetic cohorts.16 Increased LV thickness and stiffness, resulting from lipotoxicity17 and myocardial deposition of collagen and advanced glycation end products,16 may explain this finding.

We found differences in diabetic cardiac remodeling between patients with HFrEF and HFpEF. Although there were smaller indexed LV end‐diastolic volumes and higher LV filling pressures in patients with versus without diabetes mellitus in both HF phenotypes, diabetes mellitus was associated with preserved LV wall thickness and a predominantly eccentric hypertrophy phenotype in HFrEF, in contrast to LV wall thickening and a predominantly concentric hypertrophy phenotype in HFpEF. Consistent with our findings, patients with HFrEF and diabetes mellitus (versus no diabetes mellitus) in the STICH (Surgical Treatment for Ischemic Heart Failure) trial had higher E/E′ ratios and smaller LV volumes18; however, patients with HFpEF and diabetes mellitus (versus no diabetes mellitus) in the I‐PRESERVE (Irbesartan in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction) trial had higher E/E′ ratios, thicker LV walls, and more LVH.19 Unlike our study, no prior studies have concomitantly included both HF types or controls without HF from the same population.

As recently described,5, 20 the mechanisms by which diabetes mellitus affects cardiac structure in HFrEF and HFpEF differ. In HFrEF, diabetes mellitus causes increased cardiac cell death with its attendant fibrosis. Cell death occurs as a result of several pathways, including lipotoxicity and deposition of advanced glycation end products.5, 20 Lipotoxicity may occur from the accumulation of triglycerides in the cardiac cells or the toxic effects of excess circulating fatty acids.17, 20 Advanced glycation end products foster inflammation, immune cell infiltration, and subsequent apoptosis.21 Intense replacement fibrosis follows cell death because of the stimulation of protein kinase C activity in fibroblasts by hyperglycemia.20 In HFpEF, cardiac cell hypertrophy and stiffness may occur because of hyperinsulinemia13, 14 as well as endothelial dysfunction resulting from coronary microvascular disease seen in diabetes mellitus22 with downstream lack of cGMP in the myocardium.20 This has been corroborated by histological findings from LV endomyocardial biopsies in which increased fibrosis and deposition of advanced glycation end products were found in HFrEF, whereas increased cardiomyocyte resting tension was observed in HFpEF.23 The cardiac autonomic neuropathy seen in diabetes mellitus, resulting from parasympathetic denervation and increased sympathetic tone with high circulating catecholamines,24 has also been shown to cause the increased LV wall stress, LVH, and concentric remodeling25 seen in HFpEF.

In all 3 groups, diabetes mellitus appears to confer relative “protection” from LV dilatation with diabetes mellitus, albeit by different mechanisms (namely, from insulin signaling and LVH in HFpEF versus cell death from lipotoxicity and its attendant fibrosis in HFrEF). This is also seen in the left atria of patients with HFpEF. The smaller LA volumes in HFpEF with diabetes mellitus are potentially caused by the similar inward remodeling of LA in the presence of diabetes mellitus as with the LV. This is consistent with the lower atrial fibrillation rates we found in patients with diabetes mellitus in our study as well as other published cohorts.26 In BENEFICIAL (A Double‐Blind, Placebo‐Controlled, Randomized Trial Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of Alagebrium [ALT‐711] in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure), alagebrium (an advanced glycation end products cross‐link breaker) was associated with a trend toward LV dilatation in patients with HFrEF (albeit nonsignificant), in contrast to a reduction in LV end‐diastolic diameter in those receiving placebo, suggesting a role of AGE cross‐links in protecting against LV dilation.27 There was also a trend toward worse exercise tolerance in patients with HFrEF receiving alagebrium.27 Beyond HF, the phenomenon of negative remodeling with diabetes mellitus has also been described in other cardiovascular domains. Epidemiologically, there exist not only strong links of an inverse correlation between diabetes mellitus and abdominal aorta dilation but also slower aneurysm enlargement and fewer repairs for rupture in patients with diabetes mellitus.28, 29 This paradoxically protective effect of diabetes mellitus against aortic aneurysms, despite increased atherosclerosis, may in part be explained by AGE cross‐linking because alagebrium therapy was associated with aortic dilatation in elderly hypertensive dogs.30 Furthermore, in coronary atherosclerosis, the expected positive (outward) compensatory remodeling to maintain coronary blood flow in the presence of obstruction is absent in diabetes mellitus, with many studies showing a predominance of maladaptive negative (inward) remodeling.31, 32

Health‐Related QoL

There is increasing recognition of the importance of patient‐centered outcomes in HF. In both HFrEF and HFpEF, patients with diabetes mellitus had worse scores in most KCCQ domains, compared with those without diabetes mellitus. In a small study of 325 patients with HFpEF and HFrEF, diabetes mellitus was similarly associated with poorer QoL, as measured by the Minnesota Living With Heart Failure Questionnaire.33 The difference between patients with and without diabetes mellitus was more prominent across domains in HFpEF compared with HFrEF. This could be because either diabetes mellitus did not materially influence the already low QoL scores in the generally more symptomatic patients with HFrEF or diabetes with its attendant systemic inflammatory effects plays a greater role in HFpEF than HFrEF.

Clinical Outcomes

The attenuated association between diabetes mellitus and the risk of all‐cause mortality at 1 year is consistent with prior studies. In the EFFECT (Enhanced Feedback for Effective Cardiac Treatment) study, in which half of the cohort consisted of patients with HFrEF, diabetes mellitus predicted 1‐year mortality in univariable, but not in multivariable, analysis.34 Likewise, in the OPTIMIZE‐HF (Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure) Registry, in which approximately half the cohort had HFrEF, diabetes mellitus did not predict 90‐day mortality.35 A similar lack of effect of diabetes mellitus on in‐hospital mortality was seen in ADHERE (Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry).36 However, diabetes mellitus was associated with significantly higher mortality in studies with longer follow‐up.37 The CHARM (Candesartan in Heart Failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity) study found diabetes mellitus to be a significant predictor of mortality, regardless of EF, over a median follow‐up of 38 months.37 In the I‐PRESERVE trial in patients with HFpEF, with a median follow‐up of 4.1 years, diabetes mellitus was associated with higher mortality.38 The finding that diabetes mellitus is not independently predictive of death in the present study and other short‐term studies, but is with longer‐term follow‐up, suggests that short‐term mortality in patients with HF and diabetes mellitus may be determined more by comorbidities and less by diabetes mellitus itself; however, over longer‐term follow‐up, the deleterious effects of diabetes mellitus may become more apparent. Although there was no significant correlation with short‐term mortality, we found that diabetes mellitus was significantly associated with HF hospitalizations at 1 year, regardless of HF phenotype. Likewise, in the OPTIMIZE‐HF Registry, diabetes mellitus predicted rehospitalization.35 In the CHARM study, diabetes mellitus predicted increased HF hospitalizations in both HFpEF and HFrEF cohorts. These increased hospitalizations result in increased morbidity and costs, lending further evidence to the deleterious effects of diabetes mellitus in this fragile HF population and the need for adequate prevention, screening, and management of diabetes mellitus.

We found that the most common causes of cardiovascular deaths in patients with HF were the same in those with or without diabetes mellitus (namely, SCD, followed by HF‐related events). This is consistent with outcomes in the I‐PRESERVE38 trial. Patients with HF and diabetes mellitus were not receiving optimal medical therapy for HF or diabetes mellitus. The uptake of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists was lower in patients with diabetes mellitus than in those without, despite good safety data and proven benefits. Uptake of metformin was fairly low, despite current guidelines that recommend metformin as the first‐line agent unless contraindicated as well as good safety data of metformin in HF. Furthermore, the use of dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitors was not uncommon (>10%), despite safety concerns of increased cardiovascular events and HF hospitalizations. ASIAN‐HF Registry enrollment occurred before the widespread availability of sodium‐glucose cotransporter‐2 inhibitors in Asia, and it would be interesting to examine more recent trends in antidiabetic therapy. We have previously shown that HF guideline‐directed medical therapies were underused in our Asian patients, emphasizing the need for a multipronged approach to increase patient/physician education and targeted public health strategies to improve access and availability to these therapies for better patient outcomes in Asia.39

Limitations

First, we acknowledge the potential for selection bias with inclusion of predominantly academic investigators. Treatments and outcomes reported may, therefore, reflect the best practice in each region. Second, the lack of uniform screening using glycated hemoglobin or oral glucose tolerance tests may have led to underdiagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Thus, we have likely underestimated the true burden of diabetes mellitus and its associated adverse outcomes in our Asian countries. Furthermore, the lack of glycemic control data (glycated hemoglobin) and proteinuria data in the registry did not allow for assessment of diabetes mellitus control as well as complete range of microvascular complications on outcomes. We did, however, include other microvascular complications, like nephropathy, retinopathy, and neuropathy. Third, this was a predominantly Asian cohort and excluded subjects with midrange ejection fraction (EF 40%–49%), which may potentially affect the generalizability of the results. Finally, the observational nature of our study precludes conclusions on causality. Despite adjustment for multiple variables, unaccounted confounders may potentially influence the results. Nevertheless, our results about the relationship between diabetes mellitus and LV remodeling may be regarded as hypothesis generating.

Conclusions

Among patients with HFrEF and HFpEF, type 2 diabetes mellitus is associated with smaller indexed LV diastolic volumes, higher LV filling pressures, poorer QoL, and worse cardiovascular outcomes, with several differences noted between HF phenotypes.

Sources of Funding

The ASIAN‐HF (Asian Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure) Registry is supported by grants from the National Medical Research Council Singapore, Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) Biomedical Research Council's Asian Network for Translational Research and Cardiovascular Trials program, Boston Scientific Investigator Sponsored Research Program, and Bayer. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the article; and decision to submit the article for publication.

Disclosures

Dr Lam is supported by a Clinician Scientist Award from the National Medical Research Council (NMRC) Singapore. Dr Lam has received research support from Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Vifor Pharma; and has consulted for Bayer, Novartis, Takeda, Merck, Astra Zeneca, Janssen Research & Development, LLC, and Menarini. She has served on the Clinical Endpoint Committee for DC Devices. Dr Richards is supported by a Senior Translational Research award from NMRC Singapore; holds the New Zealand Heart Foundation Chair of Cardiovascular Studies; has received research support from Boston Scientific, Bayer, Astra Zeneca, Medtronic, Roche Diagnostics, Abbott Laboratories, Thermo Fisher, and Critical Diagnostics; and has consulted for Bayer, Novartis, Merck, Astra Zeneca, and Roche Diagnostics. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. The ASIAN‐HF Investigators.

Acknowledgments

The contributions of all site investigators and clinical coordinators are acknowledged.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e013114 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013114.)

References

- 1. Yoon KH, Lee JH, Kim JW, Cho JH, Choi YH, Ko SH, Zimmet P, Son HY. Epidemic obesity and type 2 diabetes in Asia. Lancet. 2006;368:1681–1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. From AM, Leibson CL, Bursi F, Redfield MM, Weston SA, Jacobsen SJ, Rodeheffer RJ, Roger VL. Diabetes in heart failure: prevalence and impact on outcome in the population. Am J Med. 2006;119:591–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bank IEM, Gijsberts CM, Teng TK, Benson L, Sim D, Yeo PSD, Ong HY, Jaufeerally F, Leong GKT, Ling LH, Richards AM, de Kleijn DPV, Dahlstrom U, Lund LH, Lam CSP. Prevalence and clinical significance of diabetes in Asian versus white patients with heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5:14–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cooper LB, Yap J, Tay WT, Teng TK, MacDonald M, Anand IS, Sharma A, O'Connor CM, Kraus WE, Mentz RJ, Lam CS. Multi‐ethnic comparisons of diabetes in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: insights from the HF‐ACTION trial and the ASIAN‐HF registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20:1281–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Seferovic PM, Paulus WJ. Clinical diabetic cardiomyopathy: a two‐faced disease with restrictive and dilated phenotypes. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1718–1727, 1727a–1727c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lam CS, Anand I, Zhang S, Shimizu W, Narasimhan C, Park SW, Yu CM, Ngarmukos T, Omar R, Reyes EB, Siswanto B, Ling LH, Richards AM. Asian sudden cardiac death in heart failure (ASIAN‐HF) registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:928–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tromp J, Teng THK, Tay WT, Hung CL, Narasimhan C, Ngarmukos T, Reyes E, Siswanto B, Yu C, Zhang S, Yap J, MacDonald M, Leineweber K, Richards AM, Zile M, Anand I, Lam CSP. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in Asia. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;21:23–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Santhanakrishnan R, Ng TP, Cameron VA, Gamble GD, Ling LH, Sim D, Leong GK, Yeo PS, Ong HY, Jaufeerally F, Wong RC, Chai P, Low AF, Lund M, Devlin G, Troughton R, Richards AM, Doughty RN, Lam CS. The Singapore heart failure outcomes and phenotypes (SHOP) study and prospective evaluation of outcome in patients with heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (PEOPLE) study: rationale and design. J Card Fail. 2013;19:156–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor‐Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Goldstein SA, Kuznetsova T, Lancellotti P, Muraru D, Picard MH, Rietzschel ER, Rudski L, Spencer KT, Tsang W, Voigt JU. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16:233–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Green CP, Porter CB, Bresnahan DR, Spertus JA. Development and evaluation of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: a new health status measure for heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1245–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eguchi K, Boden‐Albala B, Jin Z, Rundek T, Sacco RL, Homma S, Di Tullio MR. Association between diabetes mellitus and left ventricular hypertrophy in a multiethnic population. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:1787–1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Phillips RA, Krakoff LR, Dunaif A, Finegood DT, Gorlin R, Shimabukuro S. Relation among left ventricular mass, insulin resistance, and blood pressure in nonobese subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:4284–4288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hill DJ, Milner RD. Insulin as a growth factor. Pediatr Res. 1985;19:879–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Straus DS. Growth‐stimulatory actions of insulin in vitro and in vivo. Endocr Rev. 1984;5:356–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ito H, Hiroe M, Hirata Y, Tsujino M, Adachi S, Shichiri M, Koike A, Nogami A, Marumo F. Insulin‐like growth factor‐I induces hypertrophy with enhanced expression of muscle specific genes in cultured rat cardiomyocytes. Circulation. 1993;87:1715–1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Patil VC, Patil HV, Shah KB, Vasani JD, Shetty P. Diastolic dysfunction in asymptomatic type 2 diabetes mellitus with normal systolic function. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2011;2:213–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bayeva M, Sawicki KT, Ardehali H. Taking diabetes to heart—deregulation of myocardial lipid metabolism in diabetic cardiomyopathy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000433 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. MacDonald MR, She L, Doenst T, Binkley PF, Rouleau JL, Tan RS, Lee KL, Miller AB, Sopko G, Szalewska D, Waclawiw MA, Dabrowski R, Castelvecchio S, Adlbrecht C, Michler RE, Oh JK, Velazquez EJ, Petrie MC. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with and without diabetes in the Surgical Treatment for Ischemic Heart Failure (STICH) trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17:725–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kristensen SL, Mogensen UM, Jhund PS, Petrie MC, Preiss D, Win S, Kober L, McKelvie RS, Zile MR, Anand IS, Komajda M, Gottdiener JS, Carson PE, McMurray JJ. Clinical and echocardiographic characteristics and cardiovascular outcomes according to diabetes status in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: a report from the I‐Preserve Trial (Irbesartan in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction). Circulation. 2017;135:724–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Paulus WJ, Dal Canto E. Distinct myocardial targets for diabetes therapy in heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Basta G, Schmidt AM, De Caterina R. Advanced glycation end products and vascular inflammation: implications for accelerated atherosclerosis in diabetes. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;63:582–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kibel A, Selthofer‐Relatic K, Drenjancevic I, Bacun T, Bosnjak I, Kibel D, Gros M. Coronary microvascular dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. J Int Med Res. 2017;45:1901–1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van Heerebeek L, Hamdani N, Handoko ML, Falcao‐Pires I, Musters RJ, Kupreishvili K, Ijsselmuiden AJ, Schalkwijk CG, Bronzwaer JG, Diamant M, Borbely A, van der Velden J, Stienen GJ, Laarman GJ, Niessen HW, Paulus WJ. Diastolic stiffness of the failing diabetic heart: importance of fibrosis, advanced glycation end products, and myocyte resting tension. Circulation. 2008;117:43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dimitropoulos G, Tahrani AA, Stevens MJ. Cardiac autonomic neuropathy in patients with diabetes mellitus. World J Diabetes. 2014;5:17–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pop‐Busui R, Cleary PA, Braffett BH, Martin CL, Herman WH, Low PA, Lima JAC, Bluemke DA; DCCT/EDIC Research Group . Association between cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy and left ventricular dysfunction: DCCT/EDIC study (Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:447–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tan ESJ, Tay WT, Teng THK, Sim D, Leong GKT, Yeo DPS, Ong HY, Jaufeerally F, Ng TP, Poppe K, Lund M, Devlin G, Troughton R, Ling LH, Richards AM, Doughty RN, Lam CSP. Ethnic differences in atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure from Asia‐Pacific. Heart. 2018;105:842–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hartog JW, Willemsen S, van Veldhuisen DJ, Posma JL, van Wijk LM, Hummel YM, Hillege HL, Voors AA; BENEFICIAL Investigators . Effects of alagebrium, an advanced glycation endproduct breaker, on exercise tolerance and cardiac function in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:899–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. De Rango P, Farchioni L, Fiorucci B, Lenti M. Diabetes and abdominal aortic aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2014;47:243–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lederle FA. The strange relationship between diabetes and abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;43:254–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shapiro BP, Owan TE, Mohammed SF, Meyer DM, Mills LD, Schalkwijk CG, Redfield MM. Advanced glycation end products accumulate in vascular smooth muscle and modify vascular but not ventricular properties in elderly hypertensive canines. Circulation. 2008;118:1002–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reddy HK, Koshy SK, Wasson S, Quan EE, Pagni S, Roberts AM, Joshua IG, Tyagi SC. Adaptive‐outward and maladaptive‐inward arterial remodeling measured by intravascular ultrasound in hyperhomocysteinemia and diabetes. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2006;11:65–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nicholls SJ, Tuzcu EM, Kalidindi S, Wolski K, Moon KW, Sipahi I, Schoenhagen P, Nissen SE. Effect of diabetes on progression of coronary atherosclerosis and arterial remodeling: a pooled analysis of 5 intravascular ultrasound trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fujita B, Lauten A, Goebel B, Franz M, Fritzenwanger M, Ferrari M, Figulla HR, Kuethe F, Jung C. Impact of diabetes mellitus on quality of life in patients with congestive heart failure. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:1171–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lee DS, Austin PC, Rouleau JL, Liu PP, Naimark D, Tu JV. Predicting mortality among patients hospitalized for heart failure: derivation and validation of a clinical model. JAMA. 2003;290:2581–2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Greenberg BH, Abraham WT, Albert NM, Chiswell K, Clare R, Stough WG, Gheorghiade M, O'Connor CM, Sun JL, Yancy CW, Young JB, Fonarow GC. Influence of diabetes on characteristics and outcomes in patients hospitalized with heart failure: a report from the Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE‐HF). Am Heart J. 2007;154:277.e1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yancy CW, Lopatin M, Stevenson LW, De Marco T, Fonarow GC. Clinical presentation, management, and in‐hospital outcomes of patients admitted with acute decompensated heart failure with preserved systolic function: a report from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE) Database. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:76–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. MacDonald MR, Petrie MC, Varyani F, Ostergren J, Michelson EL, Young JB, Solomon SD, Granger CB, Swedberg K, Yusuf S, Pfeffer MA, McMurray JJ; CHARM Investigators . Impact of diabetes on outcomes in patients with low and preserved ejection fraction heart failure: an analysis of the Candesartan in Heart failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM) programme. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1377–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zile MR, Gaasch WH, Anand IS, Haass M, Little WC, Miller AB, Lopez‐Sendon J, Teerlink JR, White M, McMurray JJ, Komajda M, McKelvie R, Ptaszynska A, Hetzel SJ, Massie BM, Carson PE. Mode of death in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction: results from the Irbesartan in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction Study (I‐Preserve) trial. Circulation. 2010;121:1393–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Teng THK, Tromp J, Tay WT, Anand I, Ouwerkerk W, Chopra V, Wander G, Yap J, MacDonald M, Xu C, Shimizu W, Richards AM, Lam C. Prescribing patterns of evidence‐based heart failure pharmacotherapy and outcomes in the ASIAN‐HF registry: a cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e1008–e1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. The ASIAN‐HF Investigators.