Abstract

With depression being the psychiatric disorder incurring the largest societal costs in developed countries, there is a need to gather evidence on the role of nutrition in depression, to help develop recommendations and guide future psychiatric health care. The aim of this systematic review was to synthesize the link between diet quality, measured using a range of predefined indices, and depressive outcomes. Medline, Embase and PsychInfo were searched up to 31st May 2018 for studies that examined adherence to a healthy diet in relation to depressive symptoms or clinical depression. Where possible, estimates were pooled using random effect meta-analysis with stratification by observational study design and dietary score. A total of 20 longitudinal and 21 cross-sectional studies were included. These studies utilized an array of dietary measures, including: different measures of adherence to the Mediterranean diet, the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) and Alternative HEI (AHEI), the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension, and the Dietary Inflammatory Index. The most compelling evidence was found for the Mediterranean diet and incident depression, with a combined relative risk estimate of highest vs. lowest adherence category from four longitudinal studies of 0.67 (95% CI 0.55–0.82). A lower Dietary Inflammatory Index was also associated with lower depression incidence in four longitudinal studies (relative risk 0.76; 95% CI: 0.63–0.92). There were fewer longitudinal studies using other indices, but they and cross-sectional evidence also suggest an inverse association between healthy diet and depression (e.g., relative risk 0.65; 95% CI 0.50–0.84 for HEI/AHEI). To conclude, adhering to a healthy diet, in particular a traditional Mediterranean diet, or avoiding a pro-inflammatory diet appears to confer some protection against depression in observational studies. This provides a reasonable evidence base to assess the role of dietary interventions to prevent depression. This systematic review was registered in the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews under the number CRD42017080579.

Subject terms: Depression, Physiology

Introduction

Depression, characterized by low mood, loss of interest or pleasure in life, and disturbed sleep or appetite, affects over 300 million people globally [1], which represents a global prevalence of 7% for women and 4% for men [2]. Depression is a leading cause of disease burden and a major contributor to global disability [3]. According to the World Health Organization, depressive and anxiety disorders cost the global economy $1 trillion in lost productivity each year [4].

Despite significant developments, conventional treatment is effective only in one in three cases of mood disorder [5]. Moreover, the condition is often recurrent, with relapse apparent in 50% of cases [6]. In this context, identifying modifiable risk factors to guide intervention strategies to prevent mood disorders and decrease their severity would appear to have value. A range of demographic, biological, genetic and behavioral determinants for depression have been proposed [7–10]. Of the latter, habitual diet has been increasingly examined as a potential independent predictor of disease risk (e.g., [11]) and the dietary intake of specific nutrients such as n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, B vitamins, zinc, and magnesium have been implicated in brain function [9, 12–15]. The neurological pathways potentially affecting depression risk that can be modulated by nutritional intake are related to inflammation, oxidative stress, neuroplasticity, mitochondrial function, and the gut microbiome [9].

The major challenge in understanding the role of diet in the etiology of chronic disease, including depression, is the characterization of this complex exposure. One approach is the identification of dietary patterns in the population under study by statistical modeling such as factor analysis (empirically-derived dietary patterns). These dietary patterns closely match the dietary habits of the studied population but do not necessarily reflect an optimal diet and are hardly replicable to other populations. In contrast to these a posteriori methods, a priori methods generate dietary indices based on existing knowledge of what constitutes a “healthy” diet (hypothesis-oriented dietary patterns). Based on a limited set of specific food groups, rather than specific nutrients, dietary indices reflecting adherence to an ideal diet can be very useful for clinicians to communicate with patients. Recent reviews have shown that healthy dietary patterns are associated with a decreased risk of depression or depressive disorders [16–20], but these are not universal findings [16]. Additionally, comparability of the studies is hampered by the variability in methodology and combination of estimates obtained using both hypothesis-oriented and data-driven dietary patterns. There is only one review of literature using a priori defined scores based on adherence to a traditional Mediterranean diet in relation to depression [21]. However, no formal comparison of the Mediterranean diet score exists with other widely used diet quality scores as, to the best of our knowledge, there is no exhaustive review of all a priori diet quality indices.

Accordingly, we provide a systematic review of studies assessing whether adherence to various dietary guidelines or traditional dietary patterns is associated with depressive symptoms and depression. For each dietary index we conducted a meta-analysis of results from observational studies. With the relationship likely to be bidirectional—mood can induce changes in eating behavior—only longitudinal studies can clarify the direction of the association. We therefore stratified our results according to study design.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses statement [22] and was registered in the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (# CRD42017080579 at www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO).

Search strategy

We used a four-pronged approach to identifying relevant publications. First, we searched Medline, Embase and PsychINFO via Ovid (http://www.ovid.com) for articles published since their inception (1946) to 31st May 2018. The following keywords and index terms were used (“depression” or “depress* symptom*”) AND (“diet*”) AND (“index*” or “score*” or “pattern*” or “quality”). The search was limited to articles published in the English language and to full-text articles (conference abstracts were not considered). Second, we scrutinized the reference sections of the retrieved articles and systematic reviews. Third, we contacted experts in the field. Fourth, we searched our own files. The search was conducted in parallel by two authors (TA and CL) with any disagreements resolved by a third (AB).

Study selection

To be included in this systematic review, articles had to meet the following criteria: (1) Exposure: comprehensive dietary assessment (food frequency questionnaire, 24-h diet recall, food record, diet history) and use of an a priori dietary score or index; (2) Outcome: clinical depression assessed by the study staff, medical records or self-reported clinician-diagnosed (e.g., “Have you ever been diagnosed with depression by a medical doctor?”), depressive symptoms assessed by validated scales/questionnaires (such as the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale, CES-D), and defined according to validated cutoffs of these scales (i.e., cutoff of 16 for the 20-item CES-D scale) and the use of anti-depressive drugs considered only when it was combined to clinical depression or depressive symptoms assessment; (3) Design: observational study (cross-sectional, cohort, case-control); (4) Population: general free-living populations without any age limit that includes outpatients (individuals not hospitalized for physical or mental health reasons) and non-institutionalized individuals. If the study had any of the following characteristics, it was excluded: (1) Exposure: no measure of whole diet (e.g., dietary screeners or individual questions) or use of a posteriori dietary patterns; (2) Outcome: bipolar disorders, overall mood states, psychosocial stressors or perceived stress; (3) Design: intervention studies; (4) Population: pregnant or lactating women, inpatient/hospitalized populations.

Data extraction

After study selection, the following information was extracted from each retrieved article: first author’s surname, journal, year published, geographical location, study design, follow-up time (if applicable), sex and mean age, sample size, number of cases, dietary assessment tool, dietary score used (range and mean score), assessment of depression, depressive symptoms scale and threshold used (if symptoms), modeling strategy, confounders used, main findings including odds ratios or hazard/risk ratios and their standard errors/confidence intervals. When a study provided several estimates, we chose to use those from the most complex model (that is, the one including the largest number of confounders).

Quality and risk of bias assessment

We adapted the Newcastle-Ottawa checklist [23] to assess whether cohorts were representative of the wider population (as opposed to a selected occupational group, for instance), if diet was ascertained by means of a validated dietary assessment tool (e.g., FFQ), if the dietary score used was validated, whether follow-up was sufficient to preclude reverse causation (≥5 years), and if appropriate statistical adjustment was made (age, sex, smoking, physical activity, body mass index, total energy intake). If at least four of the five of the above criteria was met, the study was considered of high quality and to be at low risk of bias.

Statistical analysis

For each dietary score (exposure variable), we conducted separate meta-analyses dependent on study design (cross-sectional vs. longitudinal). We combined the results of the studies that presented analyses with the dietary score as a categorical variable, computing forest plots and combined odds, hazard or risk ratios for depression for the healthiest compared to the least healthy category. When the dietary score was analyzed as a continuous variable (four studies [24–27]), the estimates were not included in the calculation of the combined results. Estimates (beta and standard error) from studies that used depressive symptoms (outcome) as a continuous variable were converted into log odds ratios by multiplying by a factor 1.81 and then exponentiated [28]. We used random-effect meta-analysis models to account for potential heterogeneity and assessed heterogeneity by the I2 statistic [29]. Potential for publication bias was examined using contour-enhanced funnel plots where asymmetry and absence of studies in areas of non-significance suggest the presence of reporting bias [30]. We also calculated the Egger and Begg test for small study effect. Stata version 14 (StataCorp, TX, USA) was used for the statistical analyses.

Code availability

The Stata commands metan, confunnel and metabias were used. All codes used to generate the meta-analysis results can be obtained from the authors upon request.

Sensitivity analyses

As results are stratified by dietary index and by study design, further stratification can lead to only one association estimate in some strata. Therefore, we only present the sensitivity analyses results in the subgroups that contain the majority of studies. To test the impact of outcome definition (clinical depression vs. depressive symptoms), of age of the participants, of geographical region (high vs. low-middle income countries) and of study quality, we performed sensitivity analyses by variously excluding: the studies using clinical depression as they were a minority; studies on adolescents; studies performed in low-middle income countries; and studies of low quality. Finally, a study using the Mediterranean diet was identified that used psychological distress as a marker of depression [31], so we also performed a sensitivity analysis by excluding this study for a more strict assessment of depression.

Results

In Supplemental Fig. 1 we depict the process of study selection. The search yielded 3272 records (after exclusion of duplicates), of which 3058 were excluded after title and abstract screening. Out of the 214 full-text articles assessed for eligibility, we retained 51 that we scrutinized for methodological quality. The articles excluded are listed by reason of exclusion in Supplemental material. A total of ten articles were dropped after methodological quality check, comprising the presentation of only unadjusted comparisons between groups and no further statistical modeling in six studies [32–37], or no measure of whole diet in a further four [38–41]. This yielded a total 41 articles for this systematic review: 20 longitudinal and 21 cross-sectional studies.

The majority of studies were on generally healthy participants. Two studies involved participants at high risk of knee osteoarthritis [42, 43] and one included participants with a history of myocardial infarction [44]. Ten analyses used a Mediterranean diet score [25–27, 31, 43, 45–49], seven the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) or the Alternative Healthy Eating Index (AHEI) [48, 50–55], four a Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet score [56–59], nine the Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) [42, 60–67], and 15 a variety of scores such as adherence to national dietary guidelines or general “diet quality” [44, 46, 51, 68–79]. The components included in each of the main diet scores (Mediterranean, HEI, AHEI, DASH) are summarized in Supplemental Table 1. One study simultaneously captured three scores, a Mediterranean diet score, the HEI, and a pro-vegetarian dietary pattern [48], another compared the Mediterranean diet score with the Australian Recommended Food Score [46], and a last one compared the AHEI with three other scores [51].

We graded 32 analyses as being of high quality (scoring four or five) [25–27, 31, 42, 45, 46, 48, 49, 51, 55–58, 60–67, 69, 71–75, 77, 79], whereas 12 studies had a low quality score of three or less [43, 44, 47, 48, 50, 52–54, 59, 70, 76, 78], of which the majority (nine) were cross-sectional studies.

Mediterranean diet

Adherence to a traditional Mediterranean diet was measured by four different indices: the original Mediterranean Diet Score (MDS) [25, 31, 46, 48] developed by Trichopoulou and colleagues [80], the relative Mediterranean diet score (rMED) [45], the alternative Mediterranean diet score (aMED) [26, 27, 43] or the Mediterranean Style Dietary Pattern Score (MSDPS) [49]. The MDS and rMED include nine items: five beneficial (fruit, vegetable, legumes, cereals, fish), two considered detrimental (meat, dairy), one component on fat (mono-unsaturated fatty acids/saturated fatty acids [MDS] or olive oil intake [rMED]) and one component on moderate alcohol intake. The MDS ranges from zero to nine points: one point is allocated if the intake is above the median, zero if below (or inversely for detrimental items). The rMED is based on tertiles as cutoffs, therefore ranges 0–18. The aMED scores from zero (lower adherence) to five (better adherence) on 11 components (same as MDS, adding poultry [detrimental] and potatoes [beneficial]), so the total score ranges 0–55. The MSDPS comprises 13 components (same as aMED, adding sweets and eggs), each scored continuously from 0 to 10 and the total score is standardized, ranging 0–100.

The study characteristics are given in Table 1. There were two reports from the same study (the Spanish Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra, SUN [47, 48]), so we included the one with the longest follow-up (8.5 years) [48]. In total, we considered data from six cohort studies comprising samples drawn from France [45], Australia [31, 46], Spain [48], the UK [25] and the US [27] (average 9.1 years of follow-up). There were three cross-sectional studies (the US [43], Greece [26] and Iran [49]).

Table 1.

Characteristics of observational studies that examined the associations between healthy dietary indices and depressive outcomes

| Author, year | Country | Design follow-up | Population, age | N, n cases | Dietary assessment | Dietary score | Depression assessment | Model | Adjustment | OR, HR or RR, or β coefficients |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediterranean diet | ||||||||||

| Adjibade 2017 [45] | France | Cohort 12.6 years | Adults SUVIMAX, 1994–2007, Men 52.1 years, women 47.6 years | Men 2031, 69 cases; women 1492, 103 cases | ~10, 24-hDR over 2 years | rMED | Follow-up: Q. Men CES-D-20 ≥ 17; women CES-D-20 ≥ 23. Baseline: Q, A. Exclusion depressive symptoms (same CES-D cutoffs) or antidepressant use. | Logistic regression | Age, sex, intervention group, education, marital status, socio-professional status, energy intake, number of 24-h dietary records, interval between CES-D measurements, smoking status, physical activity, BMI | Men OR T3 vs. T1 0.58; 95% CI 0.29, 1.13, continuous OR 0.91; 95% CI 0.83, 0.99. Women OR T3 vs. T1 0.95; 95% CI 0.57, 1.59, continuous OR 0.99; 95% CI 0.91, 1.06 |

| Hodge 2013 [31] | Australia | Cohort 11 years | Adults Melbourne Collaborative cohort study 1990–2007, 50–69 years | 8660, 731 cases | 121-item FFQ | MDS with olive oil | Follow-up: Q. K10 ≥ 20. Baseline: A. Exclusion antidepressant or anxiolytics use. | Logistic regression | Physical activity, education, smoking, history of arthritis, asthma, kidney, energy intake, SES | OR score 7–9 vs. 0–3: 0.72; 95% CI 0.54, 0.95 |

| Sanchez Villegas 2009 [47] | Spain | Cohort 4.4 years | Adults SUN, 37.5 years | 10,094, 480 cases | 136-item FFQ | MDS | Follow-up: C, A. Self-reported doctor diagnosis or habitual use of antidepressant. Baseline: C, A. Exclusion antidepressant use or previous clinical diagnosis | Cox proportional hazards model | Age, sex, BMI, smoking, physical activity, vitamin supplements, energy intake, chronic disease at baseline | OR score 6–9 vs. 0–2: 0.58; 95% CI 0.44, 0.77 |

| Sanchez Villegas 2015 [48] | Spain | Cohort 8.5 years | Adults SUN, 37.5 years | 15,093, 1051 cases | As above | As above | As above | As above | As above | OR score 6–9 vs. 0–2: 0.70; 95% CI 0.58, 0.85 |

| Lai 2016 [46] | Australia | Cohort 12 years | Adults ALSWH, 50–54 years | 9280 | DQES | MDS | Follow-up and baseline: Q. CES-D-10 continuous Adjustment for baseline depression (no exclusion) | Linear mixed model with time-varying covariates | Area of residence, marital status, income, education, physical activity, smoking, baseline self-reported physician depression diagnosis, antidepressant use | Q5 vs. Q1, β = −0.48; 95% CI −0.74, −0.21 |

| Skarupski 2013 [27] | US | Cohort 7.2 years | Adults CHAP Chicago, 73.5 years | 3502 | 139-item FFQ | aMED | Follow-up: Q. CES-D-10 continuous. Baseline: Q. Exclusion of CES-D-10 ≥ 4 | Generalized estimating equations | Age, sex, race, education, income, widowhood, energy intake, BMI | Slope over time is positive in T1 but negative in T3, slope difference between T3 and T1 β = −0.03, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001 |

| Winpenny 2018 [25] | UK | Cohort 3 years | Adolescents ROOTS, 14 years | 603 | 4 day diet diary | MDS | Follow-up and baseline: Q. MFQ-33, continuous. Adjustment for baseline score (no exclusion) | Linear regression | Sex, SES, smoking, alcohol, physical activity, sleep, friendship quality, self-esteem, family functioning, medication use, % body fat, baseline MFQ score | Beta 1 SD MDS 0.35; 95% CI −0.04, 0.74 |

| Veronese 2016 [43] | US | Cross-sectional | Adults Osteoarthritis initiative, 61.3 years. Patients at high-risk of osteoarthritis | 4470 | 70-item FFQ | aMED | Q. CES-D-20 ≥ 16 | Logistic regression | Age, sex, race, BMI, education, smoking, annual income, Charlson comorbidity index, analgesic drugs use, total energy intake | OR Q4–5 vs. Q1–3 0.82; 95% CI 0.65, 1.04 |

| Mamplekou 2010 [26] | Greece | Cross-sectional | Adults MEDIS, 74 years | 1190, 246 cases | FFQ | aMED | Q. GDS-15 > 10 | Logistic regression | Age, sex, education, BMI, physical activity, hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia | OR 1 unit increase 1.03; 95% CI 0.98, 1.09 |

| Tehrani 2018 [49] | Iran | Cross-sectional | Adolescents Tehran, 16.2 years | 263 | 168-item FFQ | MSDPS | Q. DASS-21 ≥ 10 on the depression subscale | Logistic regression | Age, BMI, energy intake, physical activity, ethnicity, parents’ education level and total family income | OR Q5 vs. Q1 0.41; 95% CI 0.17, 0.97 |

| Healthy Eating Index HEI/Alternative Eating Index AHEI | ||||||||||

| Adjibade 2018 [51] | France | Cohort 5.9 years | Adults NutriNet-Santé, 2009–2018, 18–86 years Men 53.0 years, women 45.5 years | 26,225, 2166 cases | ~8, 24-hDR over the first 2 years | AHEI-2010 | Follow-up: Q. Men CES-D-20 ≥ 17; women CES-D-20 ≥ 23. Baseline: Q, A. Exclusion depressive symptoms (same CES-D cutoffs) or antidepressant use. | Cox proportional hazards model | Age, sex, marital status, educational level, occupational categories, household income, residential area, energy intake without alcohol, number of 24hs and inclusion month, smoking, physical activity, BMI, health events during follow-up | HR T3 vs. T1 0.96; 95% CI 0.86, 1.07 .HR per 1 SD increase 0.98; 95% CI 0.94, 1.03 |

| Akbaraly 2013 [55] | UK | Cohort 5 years | Adults Whitehall II 1991–2009, 61 years | Men 3155, 164 cases; women 1060, 96 cases | 127-item FFQ | AHEI | Follow-up: Q, A. Recurrent (at both phase 7 and 9) depressive symptoms CES-D-20 ≥ 16 or antidepressant use. Baseline: A. Exclusion antidepressant use (phase 3 or 5) | Logistic regression | Age, sex, ethnicity, energy intake, SES, retirement, living alone, smoking, physical activity, CAD, diabetes, hypertension, HDL cholesterol, lipid-lowering drugs, central obesity, cognitive impairment | OR T3 vs. T1 Men 0.95; 95% CI 0.64, 1.42. Women 0.36; 95% CI 0.20, 0.64 |

| Sanchez Villegas 2015 [48] | Spain | Cohort 8.5 years | Adults SUN, 37.5 years | 15,093, 1051 cases | 136-item FFQ | AHEI-2010 | Follow-up: C, A. Self-reported doctor diagnosis or habitual use of antidepressant. Baseline: C, A. Exclusion antidepressant use or previous clinical diagnosis | Cox proportional hazards model | Age, sex, BMI, smoking, physical activity, vitamin supplements, energy intake, chronic disease at baseline | HR Q5 vs. Q1 0.72; 95% CI 0.59, 0.88 |

| Loprinzi 2014 [52] | US | Cross-sectional | Adults NHANES 2005–2006, 20–85 years | 2574, 118 cases | Two 24-hDR | HEI 2005 | Q. PHQ-9 ≥ 10 | Logistic regression | Age, gender, ethnicity, BMI, PIR, presence of comorbidities | OR > 60 percentile vs. below 0.51; 95% CI 0.27, 0.93 |

| Rahmani 2017 [53] | Iran | Cross-sectional | Adults Iranian soldiers, 24 years | 246, 39 cases | FFQ | AHEI-2010 | Q. DASS-21 > 21 on the depression subscale (severe depression) | Logistic regression | Age, energy intake, BMI, physical activity, education, marital status, smoking, SES, family size | OR Q4 vs. Q1 0.12; 95% CI 0.02, 0.58 |

| Saneei 2016 [54] | Iran | Cross-sectional | Adults Iranian adults, 36.3 years | Men 1403, 321 cases; women 1960, 688 cases | 106-item FFQ | AHEI-2010 | Q. Iranian HADS-21 ≥ 8 | Logistic regression | Age, sex, energy intake, BMI, physical activity, smoking, marital status, educational level, family size, house possession, self-reported diabetes, current use of antipsychotic medications, dietary supplements | OR Q4 vs. Q1 Men 0.70; 95% CI 0.44, 1.11. Women 0.51; 95% CI 0.36, 0.71 |

| Beydoun 2010 [50] | US | Cross-sectional | Adults HANDLS, 47.9 years | 734, 21.2% men and 32.1% women | Two, 24-hDR | HEI-2005 | Q. CES-D-20 ≥ 16 | Linear regression | Age, ethnicity, marital status, education, poverty status, smoking status, illicit drug use, and BMI | Men β = −0.045 SE = 0.024 p = 0.06. Women β = −0.083, SE = 0.023, p < 0.001 |

| Dietary approaches to stop hypertension DASH | ||||||||||

| Perez Cornago 2017 [58] | Spain | Cohort 8 year | Adults SUN, 37.5 years | 14,051, 113 cases | 136-item FFQ | Dixon Mellen Fung Gunther | Follow-up: C, A. Self-reported doctor diagnosis or habitual use of antidepressant. Baseline: C, A. Exclusion antidepressant use or previous clinical diagnosis | Cox proportional hazards model | Sex, smoking, physical activity, energy intake, living alone, unemployment, marital status, baseline hypertension, weight change, personality traits | HR Dixon 3–9 vs.. ≤ 2, 1.47; 95% CI 0.95, 2.3 HR Mellen Q2–Q5 vs. Q1, 0.68; 0.45, 1.04 HR Fung Q2–Q5 vs. Q1, 0.63; 95% CI 0.41, 0.95 HR Gunther Q2–Q5 vs. Q1, 1.01; 95% CI 0.63, 162 |

| Meegan 2017 [57] | Ireland | Cross-sectional | Adults Cork&Kerry Diabetes and Heart Disease Study, 59.8 years | 2040, 302 cases | 127-item EPIC FFQ | Fung | Q. CES-D-20 ≥ 16 | Logistic regression | Age, sex, BMI, smoking, physical activity, alcohol, antidepressant use, history of depression | OR > median vs. below 1.06; 95% CI 0.69, 1.63 |

| Valipour 2017 [59] | Iran | Cross-sectional | Adults SEPAHAN, 36 years | 1712 men; 2134 women 1108 total cases | 106-item FFQ | Fung modified (deciles, different items) | Q. HADS-D-21 ≥ 8 | Logistic regression | Age, sex, energy intake, marital status, socioeconomic status, smoking, physical activity, chronic disease, antidepressant use, supplement use, pregnant or lactating, frequent spice consumers, BMI | OR ≥ 51 vs. ≤ 40: men 1.08; 95% CI 0.73, 1.6, women 0.96; 95% CI 0.72, 1.28 |

| Khayyatzadeh 2017 [56] | Iran | Cross-sectional | Adolescents Iranian girls, 12–18 years | 535, 172 cases | 168-item FFQ | Fung | Q. Persian version of BDI-21 > 16 | Logistic regression | Age, energy intake, mother job status, passive smoker, menstruation, parent death, parent divorce, physical activity, BMI, SES, education | OR Q4 vs. Q1 0.47; 95% CI 0.23, 0.92 |

| Dietary Inflammatory Index DII | ||||||||||

| Akbaraly 2016 [61] | UK | Cohort 5 years | Adults Whitehall II 2002–2009, 61 years | Men 3178, 166 cases; Women 1068, 99 cases | 127-item FFQ | DII | Follow-up: Q, A. Recurrent (phase 7 and 9) depressive symptoms CES-D-20 ≥ 16 or antidepressant use. Baseline: A. Exclusion antidepressant use (phase 3 or 5) | Logistic regression | Age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, occupation, smoking, alcohol, energy intake, physical activity, CVD risk factors | OR T1 vs. T3 men 0.96; 95% CI 0.60, 1.54. Women 0.35; 95% CI 0.18, 0.68 |

| Adjibade 2017 [60] | France | Cohort 12.6 years | Adults SUVIMAX, 1994–2007, Men 52.1, Women 47.6 | Men 2031, 69 cases; Women 1492, 103 cases | ~10 24-hDR over 2 years | DII | Follow-up: Q. Men CES-D-20 ≥ 17; women CES-D-20 ≥ 23. Baseline: Q, A. Exclusion depressive symptoms (same CES-D cutoffs) or antidepressant use. | Logistic regression | Age, sex, intervention group, education, marital status, socio-professional status, energy intake, number of 24-h DR, interval between the two CES-D measurements, smoking, physical activity, BMI | OR Q1 vs. Q4 men 0.43; 95% CI 0.19, 0.99. Women 1.39; 0.75, 2.56 |

| Sanchez Villegas 2015 [67] | Spain | Cohort 8.5 years | Adults SUN, 37 years | 15,093, 1051 cases | 136-item FFQ | DII | Follow-up: C, A. Self-reported doctor diagnosis or habitual use of antidepressant. Baseline: C, A. Exclusion antidepressant use or previous clinical diagnosis | Cox proportional hazards model | Age, sex, energy intake, prevalence of disease, BMI, smoking, physical activity, vitamin supplement, CVD, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia at baseline | HR Q1 vs. Q5 0.68; 95% CI 0.54, 0.85 |

| Shivappa 2016 [65] | Australia | Cohort 9 years | Adults ALSWH 2001–2013, 52 years | 6438, 1156 cases | 101-item FFQ | DII | Follow-up: Q. CES-D-10 ≥ 10 Baseline: Q. Exclusion history depressive symptoms CES-D-10 ≥ 10 survey 1 to 3. | Relative risk (log-binomial or Poisson) | Energy intake, education, marital status, menopause status, night sweats and major personal illness or injury, smoking, physical activity, BMI, depression diagnosis or treatment | RR Q1 vs. Q4 0.81; 95% CI 0.69, 0.96 |

| Shivappa 2018 [42] | US | Cohort 8 years | Adults Osteoarthritis initiative, 61.4 years Patients at high-risk of osteoarthritis | 3608, 837 cases | 70-item FFQ | DII | Follow-up: Q. CES-D-20 > 16. Baseline: Q. Exclusion prevalent depressive symptoms CES-D-20 > 16 | Cox proportional hazards model | Age, sex, race, BMI, education, smoking, income, physical activity, Charlson co-morbidity index, CES-D at baseline, statin use, NSAIDS or cortisone use | HR Q1 vs. Q4 0.81; 95% CI 0.65, 0.99 |

| Wirth 2017 [66] | US | Cross-sectional | Adults NHANES III, 2005–2012, 46.9 years | Men 9322, 595 cases; women 9553, 1053 cases | Two 24-hDR | DII | Q. PHQ-9 ≥ 10 | Logistic regression | Race, education, marital status, perceived health, current infection status, smoking family member, smoking status, past cancer, diagnosis, arthritis, age, average nightly sleep duration | OR Q1 vs. Q4 Men 0.92; 95% CI 0.61, 1.37. Women 0.77; 95% CI 0.60, 1.00 |

| Bergman 2017 [62] | US | Cross-sectional | Adults NHANES III, 2007–2012, 20–80 years | 11,592, 939 cases | Two 24-hDR | DII | Q. PHQ-9 ≥ 10 | Logistic regression | Age, sex, ethnicity, poverty income ratio, employment, health insurance, education, marital status, BMI, smoking, physical activity, sedentary time, vitamin supplements use, energy intake, menopause, comorbidity (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, CVD, respiratory illness, cancer) | OR Q1 vs. Q5 0.44; 95% CI 0.31, 0.63 |

| Philipps 2017 [63] | Ireland | Cross-sectional | Adults Cork&Kerry Diabetes and Heart Disease Study, 50–69 years | 1992 | 127-item EPIC FFQ | DII | Q. CES-D-20 ≥ 16 | Logistic regression | Age, sex, BMI, physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption, antidepressant use and history of depression | OR T1 vs. T3 men 1.28; 95% CI 0.61, 2.78. Women 0.45; 95% CI 0.23, 0.87 |

| Shivappa 2017 [64] | Iran | Cross-sectional | Adolescents Iranian adolescent girls, 15–18 years | 299, 84 cases | 168-item FFQ | DII | Q. DASS-21 > 9 | Logistic regression | Age, total energy intake, physical activity, marital status, income, smoking, BMI, chronic disease | OR T1 vs. T3 0.29; 95% CI 0.11, 0.75 |

| Other diet quality indices | ||||||||||

| Collin 2016 [69] | France | Cohort 13 years | Adults SUVIMAX, 49.5 years | 3328, 340 cases | ~10, 24-hDR over 2 years | mPNNS-GS French guidelines | Outcome: Q. chronic depressive symptoms defined as CES-D-20 ≥ 16 at baseline and follow up. Baseline: A. Exclusion of antidepressant use. | Logistic regression | Age, sex, energy intake, education, marital status, tobacco, supplementation group, number of 24 h DR, baseline BMI and physical activity | OR Q4 vs. Q1 0.51; 95% CI 0.35, 0.73 |

| Adjibade 2018 [51] | France | Cohort 5.9 years | Adults NutriNet-Santé, 2009–2018, 18–86 years. Men 53.0 years, women 45.5 years | 26,225, 2166 cases | ~8, 24-hDR over the first 2 years | mPNNS-GS French guidelines | Follow-up: Q. Men CES-D-20 ≥ 17; women CES-D-20 ≥ 23 Baseline: Q, A. Exclusion depressive symptoms (same CES-D cutoffs) or antidepressant use. | Cox proportional hazards model | Age, sex, marital status, educational level, occupational categories, household income, residential area, energy intake without alcohol, number of 24hs and inclusion month, smoking, physical activity, BMI, health events during follow-up | HR T3 vs. T1 0.80; 95% CI 0.72, 0.90. HR per 1 SD increase 0.92; 95% CI 0.87, 0.96 |

| PANDiet | HR T3 vs. T1 0.88; 95% CI 0.79, 0.98. HR per 1 SD increase 0.95; 95% CI 0.91, 0.99 | |||||||||

| DQI-I | HR T3 vs. T1 0.79; 95% CI 0.70, 0.88. HR per 1 SD increase 0.91; 95% CI 0.87, 0.95 | |||||||||

| Lai 2017 [77] | Australia | Cohort 9 years | Adults ALSWH, Women 45–50 years | 7877, 2841 cases | DQES | ARFS | Follow-up: Q. CES-D-10 ≥ 10. Baseline: A. Exclusion self-report depression | Logistic regression | Area of residence, marital status, income, education, smoking, physical activity, anxiety/nervous disorder | OR T3 vs. T1 0.94; 95% CI 0.83, 1.00 |

| Lai 2016 [46] | Australia | Cohort 12 years | Adults ALSWH, Women 45–50 years | 11,046 | DQES | ARFS | Follow-up and baseline: Q. CES-D-10 continuous Adjustment for baseline depression (no exclusion) | Linear mixed model | Area of residence, marital status, income, education, smoking, physical activity, self-reported physician diagnosis and use of antidepressants | Q5 vs. Q1 β = −0.23; 95% CI −0.47, 0.01 |

| Espana Romero 2013 [70] | US | Cohort 6.1 years | Adults Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study, 47 years | 5110, 641 cases | 3 day food record | AHA diet goals. 4 items: F&V, fish, sodium, wholegrain | Follow-up: Q. CES-D-30 ≥ 8. Baseline: C. Exclusion previous mental disorder | Logistic regression | Age, sex, baseline year, heavy alcohol intake, other ideal components: smoking, BMI, physical activity, total cholesterol, blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose | OR ideal (3–4) vs. poor (0–1) 0.58; 95% CI 0.37, 0.92 |

| Gall 2016 [71] | Australia | Cohort 5 years | Adults Childhood Determinants of Adult Health (CDAH), 31.7 years | 1233, 203 cases | 127-item FFQ | Australian Dietary Guideline Index | C. Composite International Diagnostic Interview diagnosis of major depression. Outcome: first episode vs. no new episode (may include history of mood disorder before baseline) | Log multinomial regression | Age, sex, education, physical health related quality of life, history of CVD or diabetes, oral contraceptive use, area-level SES, social support, parental status | RR Q4 vs. Q1–Q3: 0.71; 95% CI 0.39, 1.3 |

| Sanchez Villegas 2015 [48] | Spain | Cohort 8.5 years | Adults SUN, 37.5 years | 15,093, 1051 cases | 136-item FFQ | Pro-vegetarian food pattern | Follow-up: C, A. Self-reported doctor diagnosis or habitual use of antidepressant. Baseline: C, A. Exclusion antidepressant use or previous clinical diagnosis | Cox proportional hazards model | Age, sex, BMI, smoking, physical activity, vitamin supplements, energy intake, chronic disease at baseline | HR Q5 vs. Q1 0.78; 95% CI 0.64, 0.93 |

| Voortman 2017 [79] | Netherlands | Cohort 13.5 years | Adults Rotterdam Study, 64.1 years | 6217, 1686 cases | 389-item FFQ | Dutch Dietary Guidelines 2015 | Follow-up: C, A. Self-reported history of depression, psychiatric examination (CES-D + semi-structured clinical interview), medical records, antidepressant. Baseline: C. Exclusion prevalent disease | Cox proportional hazards model | Cohort, age, sex, education, employment, smoking, physical activity and energy intake | HR Q5 vs. Q1 0.89; 95% CI 0.76, 1.04 |

| Jacka 2010 [75] | Australia | Cross-sectional | Adults Geelong Osteoporosis Australia, Women 20–94 years | 1046, 60 cases | 74-item FFQ | ARFS | C. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR | Logistic regression | Age, socioeconomic status, education, physical activity, alcohol, smoking, energy intake | OR z-score, 0.85; 95% CI 0.62, 1.13 |

| Q. GHQ-12 continuous | Linear regression | As above | β = −0.08; 95% CI −0.14, -0.01 | |||||||

| Jacka 2011 [74] | Norway | Cross-sectional | Adults Hordaland Health study 1997, 46–74 years | Men 2477, 230 cases. Women 3254, 281 | 169-item FFQ | DQS 6 items | Q. HADS-D-7 ≥ 8 | Logistic regression | Age, income, education, physical activity, smoking, alcohol, energy intake | OR z-score Men 0.83; 95% CI 0.70, 0.99. Women 0.71; 95% CI 0.59, 0.84 |

| Sakai 2017 [78] | Japan | Cross-sectional | Three-generation Study of Women on Diets and Health, Adolescenst 18 years. Adults 47.9 years | Adolescent 3963, 871 cases. Adults 3833, 643 cases | DHQ | Japanese DQS 7 items | Q. CES-D-20 ≥ 23 | Logistic regression | BMI, smoking, medication use, self-reported stress, dietary reporting status, physical activity, energy intake | OR Q5 vs. Q1 Adolescents 0.67; 95% CI 0.49, 0.92. Adults 0.55; 95%CI 0.4, 0.75 |

| Gomes 2017 [72] | Brazil | Cross-sectional | Adults Pelotas, 60 years+ | Men 508, 50 cases. Women 870, 161 cases | FFQ | EDQ-I | Q. Brazilian GDS-10 ≥ 5 | Logistic regression | Age, marital status, education, economic class, leisure time physical activity, current smoking, alcohol intake | OR T1 vs. T3 Men 3.78; 95% CI 1.35, 10.57. Women 2.13; 95%CI 1.35, 3.33 |

| Huddy 2016 [73] | Australia | Cross-sectional | Adults Melbourne InFANT Extend Program, Women 19–45 years | 437, 151 cases | 137-item FFQ | Australian Dietary Guideline Index | Q. CES-D-10 ≥ 10 | Linear regression | Age, education, smoking, physical activity, television viewing, sleep quality, BMI | 1 point increase β = −0.034; 95%CI −0.056, −0.012 |

| Kronish 2012 [76] | US | Cross-sectional | Adults REGARDS 2003–2007, 65 years | 20,093, 1959 cases | 109-item FFQ | 5 items: fish, F&V, sodium, sugar, fiber/carb | Q. CES-D-4 ≥ 4 | Poisson regression | Age, race, sex, region of residence, income, education | Prevalence ratio < 2 vs. ≥ 2 1.08; 95% CI 1.06, 1.10 |

| Rius-Ottenheim 2017 [44] | Netherlands | Cross-sectional | Adults Alpha Omega, 72.2 years Patients with a history of myocardial infarction | 2171 | 203-item FFQ | DHNaFS DUNaFS | Q. GDS-15 continuous | Linear regression | Age, sex, education, marital status, physical activity, BMI, high alcohol use, smoking, antidepressants use, family history of depression, self-rated health, chronic disease, treatment group | continuous, β = −0.108 p < 0.001; continuous, β = −0.002 p = 0.93 |

Country: UK United Kingdom, US United States of America

Study: ALSWH Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health, HANDLS Healthy Aging in Neighborhoods of Diversity across the Life Span; InFANT Infant Feeding, Activity, and Nutrition Trial, MEDIS MEDiterranean ISlands study, NHANES National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, REGARDS Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke, ROOTS adolescents from Cambridgeshire and Suffolk recruited through secondary schools, SEPAHAN Studying the Epidemiology of Psycho-Alimentary Health and Nutrition, SUN Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra, SUVIMAX Supplementation en Vitamines et Mineraux study

Dietary instrument: 24h DR 24-hour dietary recall, DHQ diet history questionnaire, DQES dietary questionnaire for epidemiological studies, FFQ food frequency questionnaire

Dietary score: MDS Mediterranean Diet Score, rMED relative Mediterranean Diet Score, aMED alternative Mediterranean Diet Score, AHEI Alternative Healthy Eating Index, HEI Healthy Eating Index, DASH Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension, DII, Dietary Inflammatory Index, mPNNS-GS modified score to the French dietary guidelines (PNNS-Guideline Score), AHA, American Heart; Association, ARFS Australian Recommended Food Score, DGI, Dietary Guidelines Index, DQI-I, Diet Quality Index International, DQS diet quality score, DHNaFS Dutch Healthy Nutrient and Food Score, DUNaFS Dutch Undesirable Nutrient and Food Score, EDQ-I Elderly Dietary Quality Index, PANDiet Diet Quality Index based on the probability of adequate nutrient intake

Depression assessment: Q questionnaire, C clinical, A antidepressant use, BDI Beck Depression Inventory, CES-D Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (followed by number of items in the scale), DASS Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale, DSM-IV-TR Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, GDS Geriatric Depression Scale, GHQ-12 General Health Questionnaire 12 items, HADS(-D) Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Depression subscale), K10 Kessler Psychological Distress Scale, MFQ Moods and Feelings Questionnaire (range 0–66), PHQ-9 Patient Health Questionnaire 9 item depression module

Adjustment: BMI body mass index, CAD coronary artery disease, CVD cardiovascular disease, HDL high-density lipoprotein, PIR poverty-to-income ratio, SES socioeconomic status

Measure of association: OR odds ratio, HR hazard ratio, RR risk ratio, 95% CI 95% confidence interval, T tertile, Q4 quartile, Q5 quintile

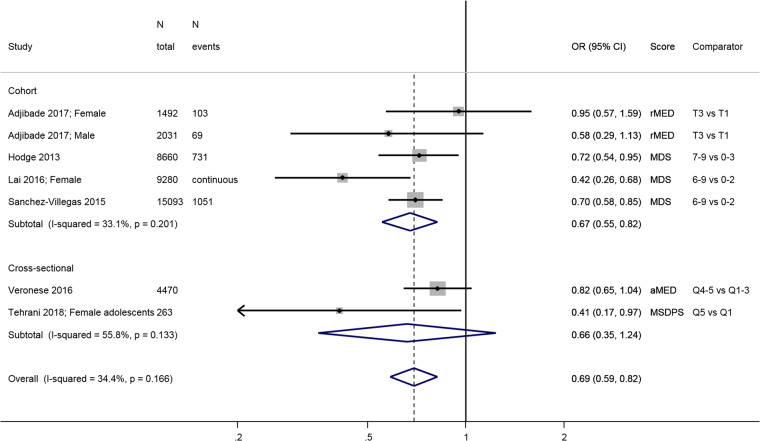

The combined estimate from four longitudinal studies [31, 45, 46, 48] shows that people in the highest category of adherence to a Mediterranean diet have lower odds/risk of incident depressive outcomes, with an overall estimate of 0.67; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.55, 0.82 compared to people with lowest adherence (Fig. 1). The estimate from two studies [25, 27] were produced using linear models or generalized estimating equation and therefore not comparable to the other studies: one showed a significant inverse association over time [27], and the other study, on adolescents, found no significant association [25]. The three cross-sectional studies yielded inconsistent results.

Fig. 1.

Meta-analysis of studies investigating the association between a traditional Mediterranean diet and depressive outcomes. Estimates are ORs, RRs or HRs of depression for people with highest adherence compared to lowest adherence (categories or quantiles specified). MDS Mediterranean diet score, rMED relative MDS, aMED alternative MDS, T tertile, Q quintile

Healthy Eating Index (HEI)

There were three longitudinal cohort studies (United Kingdom [55], Spain [48], and France [51]) with an average 6.5 years follow-up) and four cross-sectional studies (US [50, 52] and Iran [53, 54]) that used either the HEI-2005 [50, 52], the original AHEI [55] or the AHEI-2010 [48, 51, 53, 54] (Table 1). The HEI-2005 is based on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005, ranges 0–100 and has 12 components, each scoring five or ten points: total fruit, whole fruit, total vegetables, dark green and orange vegetables and legumes, total grains, whole grains, dairy, meat and beans, oils, saturated fat, sodium, empty calories. The AHEI includes nine components, each with a score of up to ten points except multivitamin use (vegetables, fruit, nuts and soy protein, ratio of white to red meat, cereal fiber, trans fat, polyunsaturated-to-saturated fat ratio, duration of multivitamin use, and alcohol), for a total score ranging 2.5 to 87.5. Finally, the AHEI-2010 comprises 11 items (vegetables, fruit, nuts and legumes, red/processed meat, whole grains, trans fat, long-chain (n-3) fatty acids, polyunsaturated fat, alcohol, sugar-sweetened beverages and fruit juice, and sodium) and ranges 0–110.

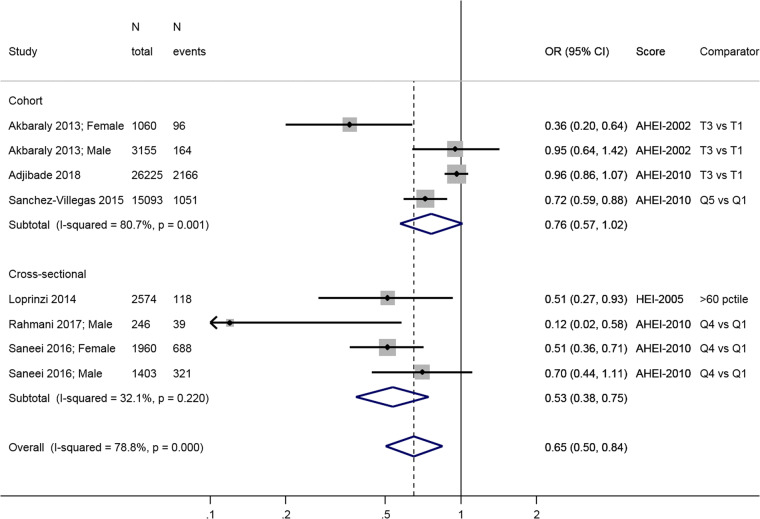

The three longitudinal studies [48, 51, 55] show a lower risk of incident depression in the high diet score category compared to low (0.76; 95% CI: 0.57, 1.02), but this association is only borderline significant at the conventional level (Fig. 2). There was large heterogeneity in the estimates of these three studies (I2 = 80.7%, p = 0.001). Overall, the cross-sectional studies show an inverse association between HEI-2005 or AHEI-2010 and prevalence of depression: OR = 0.53; 95% CI: 0.38, 0.75, with no apparent heterogeneity (I2 = 32.1%, p = 0.22) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis of studies investigating the association between HEI/AHEI and depressive outcomes. Estimates are ORs, RRs, or HRs of depression for people with highest adherence compared to lowest adherence (categories or quantiles specified). HEI healthy eating index, AHEI Alternatative Heatlhy Eating Index, T tertile, Q5 quintile, Q4 quartile, 60pctile 60th percentile

Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH)

Four studies [56–59] used the DASH diet score developed by Fung and colleagues [81] or a modified version (Table 1). It comprises eight components relative to food group intakes (negative: sweet beverages, meat, sodium; positive: fruit, vegetables, legumes and nuts, wholegrain, low-fat dairy), scores of one to five correspond to sex-specific quintiles, and the total sum score ranges 8–40.

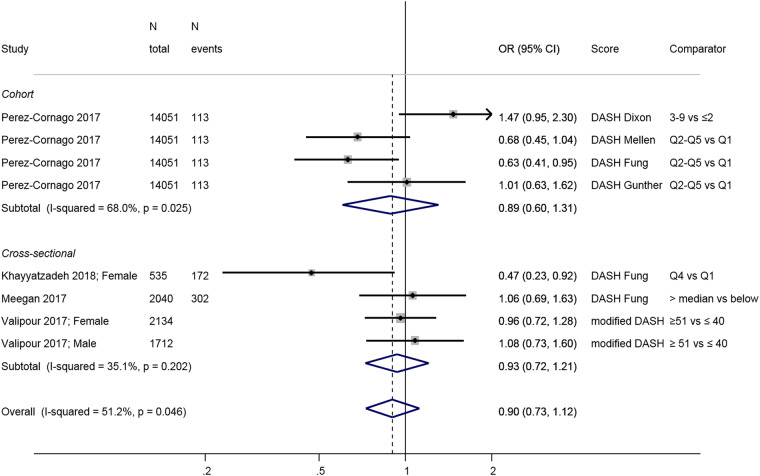

Investigators in the only longitudinal study, the Spanish SUN cohort [58], compared the Fung DASH diet score to three other DASH scores [82–84] which use different scoring system or include nutrient intakes, and found a significant negative association with depression incidence only when using the Fung score; the other DASH scores were not associated with clinical depression (Fig. 3). Results from cross-sectional studies reveal no association with the exception of an Iranian study of adolescent girls [56] that found an inverse association between DASH and depressive symptoms. Overall, the link between adherence to a DASH diet and depression has been little studied and results are inconclusive, particularly in adults.

Fig. 3.

Meta-analysis of studies investigating the association between a DASH diet and depressive outcomes. Estimates are ORs, RRs, or HRs of depression for people with highest adherence compared to lowest adherence (categories or quantiles specified). DASH dietary approaches to stop hypertension, T tertile, Q5 quintile, Q4 quartile

Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII)

The DII is a literature-derived, population-based index that aims to quantify the overall effect of diet on inflammatory potential based on the individual inflammatory effects of up to 45 food parameters [85]. We found five cohort studies from the UK [61], the US [42], France [60], Australia [65] and Spain [67] and four cross-sectional studies from the US [62, 66], Ireland [63] and Iran [64] (Table 1).

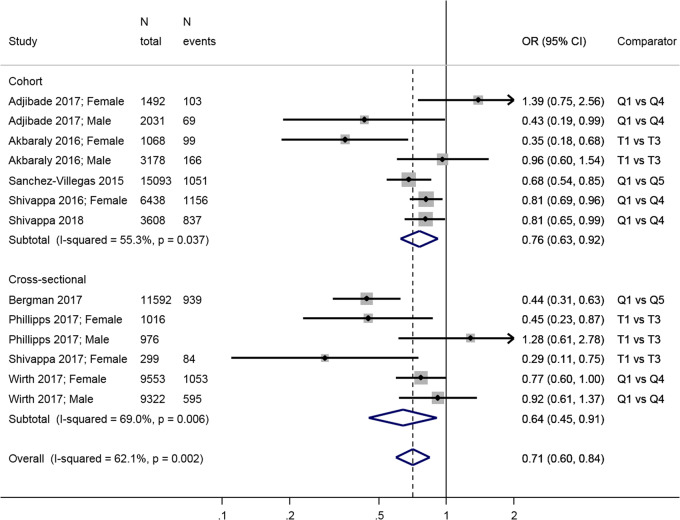

Comparing the least inflammatory to the most inflammatory diet, there was a combined inverse association in both longitudinal (overall HR = 0.76; 95% CI: 0.63, 0.92) and cross-sectional (overall OR = 0.64; 95% CI: 0.45, 0.91) (Fig. 4) analyses. There was significant heterogeneity in the results from both longitudinal (I2 = 55.3%, p = 0.04) and cross-sectional studies (I2 = 69.0%, p = 0.006), in particular due to differences between estimates in men and women, with three studies showing a negative association in women but no relationship in men [61, 63, 66]; another study found the reverse [60].

Fig. 4.

Meta-analysis of studies investigating the association between the Dietary Inflammatory Index DII and depressive outcomes. Estimates are ORs, RRs, or HRs of depression for people with lowest adherence compared to highest adherence (categories or quantiles specified). T tertile, Q5 quintile, Q4 quartile

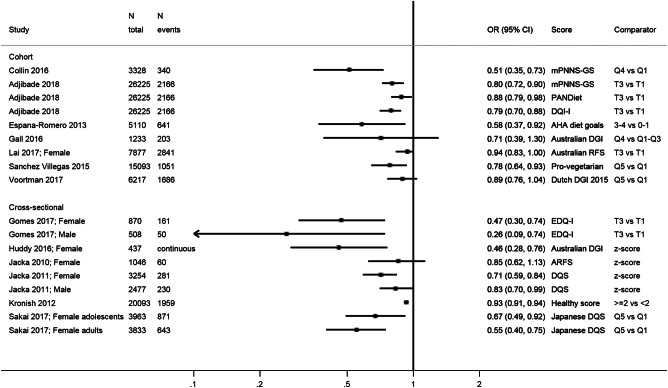

Other dietary indices

A variety of other scores were used to describe adherence to national dietary guidelines [44, 46, 51, 69, 71, 73, 75, 77, 79], to the American Heart Association recommendations [70], and pro-vegetarian [67] or general “diet quality” scores [2, 72, 74, 76, 78] (Table 1). Owing to an absence of comparability, we show all estimates on a summary plot (Fig. 5) but do not provide an overall estimate. We observed a trend towards an inverse association between higher diet quality and depression.

Fig. 5.

Summary of studies investigating the association between various other diet quality scores and depressive outcomes. mPNNS-GS modified score of adherence to the French dietary guidelines (PNNS), AHA American Heart Association, (A)RFS (Australian) Recommended Food Score, DGI Dietary Guidelines Index, DQI-I Diet Quality Index International, DQS Diet quality score, EDQ-I Elderly Dietary Quality Index, PANDiet Diet Quality Index Based on the Probability of Adequate Nutrient Intake, T tertile, Q5 quintile, Q4 quartile

Risk of bias

We present the contour-enhanced funnel plots for the four main dietary scores on Supplemental Fig. 2. There was little evidence of publication bias as evidenced by visual inspection of the plots: estimates from the included studies are distributed equally around the overall estimate for each index used, and studies with both significant and non-significant estimates were included. Egger’s test for small study effects was significant only for the studies using the HEI or AHEI (p = 0.01), but the Begg test was non-significant (p = 0.39). All tests for small study effects were non-significant for Mediterranean, DASH and DII.

Sensitivity analyses

Regarding outcome definition, when analyzing only studies on depressive symptoms outcomes (that is, excluding studies using clinical depression as outcome), the results remained similar for the MDS and DII (Supplemental Figs. 3 and 5 respectively), but the overall estimate for the HEI /AHEI based on three prospective studies was substantially attenuated (Supplemental Fig. 4): 0.74; 95% CI: 0.47, 1.18. Results on clinical depression all come from the Spanish SUN cohort, which showed strong prospective associations with the MDS, HEI, and DII scores [48, 67] but not consistent with different DASH scores [58]. In addition, Supplemental Figure 6 shows that for all other dietary scores, significant negative associations were reported with depressive symptoms, whereas the three studies that used clinical depression report non-significant associations [71, 75, 79]. Regarding study quality, all cross-sectional studies using HEI/AHEI were judged of low quality; therefore, when limiting the evidence to high quality studies, this dietary score only shows a weak overall estimate from three cohort studies. When assessing the differences by geographical region, we found that studies in middle-income country were all conducted in Iran. Two of them, carried out in adults, assessed the cross-sectional association between the HEI and depressive symptoms and reported similar estimates to those observed in an Irish cross-sectional study using the HEI score too. In addition, three Iranian studies were carried out on adolescents and found significant inverse associations between Mediterranean diet, DASH and DII scores and depressive symptoms. The global estimates between each of these dietary scores and depressive symptoms were not altered after excluding studies conducted in adolescents as illustrated in Supplemental Figure 7, 8 and 9, showing results for the Mediterranean diet, DASH, and DII scores respectively. Finally, having excluded the study using psychological distress [31], the overall results of the association between a Mediterranean diet and depressive outcomes remained essentially unchanged (Supplemental Figure 10).

Discussion

Main findings

By focusing on dietary indices, this systematic review is the first to provide an exhaustive overview of the evidence linking a wide range of comparable a priori diet quality indices and depressive outcomes. From analyses of longitudinal studies, there is a robust association between both higher adherence to a Mediterranean diet and lower adherence to a pro-inflammatory diet and a lower risk of depression. While there are fewer studies, the same trend seems apparent for indices such as the Healthy Eating Index and several other country-specific dietary guidelines scores.

Comparison with the literature

According to recent reviews, the available evidence suggests an inverse association between healthy or prudent dietary patterns and depression, despite some inconsistent results and heterogeneity in the methods used to define healthy dietary patterns [16–20]. The beneficial effect of the Mediterranean diet has been reviewed in 2013 [21] but these studies were, with one exception, cross-sectional. The addition of recent longitudinal studies reinforces the previous review in concluding that highest compared to lowest adherence to a Mediterranean diet is associated with lower risk of incident depressive outcome. A unique feature of the present review is the inclusion and comparison of a wide range of a priori dietary scores. We found that the measures of adherence to dietary guidelines that have been commonly studied in relation to other chronic diseases and mortality, HEI and AHEI [86–88], also show encouraging results in relation to depression; however, more longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the direction of the associations.

Biological mechanisms

As summarized in Supplemental Table 1, the dietary scores share common elements: higher fruits, vegetables, and nut intake, lower intakes of pro-inflammatory food items such as processed meats and trans fats, and alcohol in moderation. To date, a number of factors have been proposed to cause diet-induced damage to the brain, including oxidative stress, insulin resistance, inflammation, and changes in vascularization, as all these factors can be modified by dietary intake and have been associated with occurrence of depression [89]. Moreover, recent human studies [90] support extensive pre-clinical research [91], suggesting an impact of diet on the hippocampus. Fruit, vegetables, nuts, and wine in moderation have been associated with better metabolic health outcomes [92, 93], which share a common etiology with depression [94]. Those foods have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Protection against oxidation can reduce neuronal damage due to oxidative stress [17]. Systemic inflammation can affect the brain by active transport of cytokines through the brain endothelium or activation of vagal fibers, and also plays a role in the regulation of emotions through mechanisms involving neurotransmitters including serotonin, dopamine, noradrenaline, and glutamate [60]. Our results show a consistent association between an inflammatory diet (measured by the DII) and incident depressive outcomes, which supports the hypothesis that avoiding pro-inflammatory foods in favor to anti-inflammatory diet might contribute to prevent incidence of depression and depressive symptoms. Finally, an extensive body of evidence now points to the microbiome-gut-brain axis as playing a key role in neuropsychiatry, and to the primacy of diet as a factor modulating this axis [95].

Limitations

With depression being the psychiatric disorder incurring the largest societal costs in Europe, our study is part of an effort to gather evidence on the role of nutrition in depression, to help develop recommendations and guide future psychiatric health care. Recent reviews [16–19] paved the way and our results come to complement the previous studies by focusing on dietary indices that can have a direct application in clinical settings.

However, there are various methodological considerations that need to be taken into account when interpreting the results of this meta-analysis. First, despite defining strictly our outcome of interest to unipolar depression or depressive symptoms, there was heterogeneity across studies: most used questionnaires, in particular the CES-D, although differing versions, and some questionnaires were only used in a single study (MFQ [25], BDI [56]). Only a minority of studies examined clinical depression [48, 58, 67, 71, 75, 79], assessed by clinical interview or self-reported physician diagnosis, complemented by the use of anti-depressants. Therefore, the accuracy of the prevalence or incidence may differ from one study to another. Moreover, depressive symptoms may be transient and are potentially reversible, whereas diagnosed depression is of greater severity, although they can also be reversible and transient. Our results show that most studies focused on depressive symptoms, but there is a lack of evidence for clinical depression. The only studies included in the present review that used formal diagnosis of depression as an outcome are from the SUN cohort, which showed strong and robust associations with four different dietary indices [48, 67] except for DASH scores [58], and three other studies that found no significant association with the Australian [71, 75] or with the Dutch [79] dietary guidelines scores. The meta-analysis conducted by Molendijk et al. found that there was no overall association between adherence to healthy dietary patterns and incidence of depression using a formal diagnosis as outcome [16], but this review included only three studies, one of which used internalizing disorder (not specifically depression) in children as outcome, so the comparability of these three estimates is problematic.

Second, even under the same diet index name, the operationalization differed between studies depending on the dietary data available and how they were collected. It is common for large observational studies to collect self-reported dietary data with imperfect instruments such as food frequency questionnaires. These are associated with substantial measurement error, which can reduce the ability to detect associations [96]. Moreover, the majority of studies assessed diet at a single time point and did not take into account possible changes in diet quality over time that may be concomitant to the development of depressive symptoms. Furthermore, most studies compare extreme categories, e.g., top vs. bottom, but some used tertiles, others quartiles, or quintiles, making the comparisons less straightforward. In contrast to other meta-analyses [16, 17], we presented global estimates of studies assessing the same dietary score, analyzed as categorical variable, and did not include studies assessing dietary scores as continuous variables, in order to provide more homogeneous results and an accurate quantification of the diet-depression relationship. Additionally, by presenting separate estimates according to the cross-sectional and longitudinal design of studies with long-term follow-up that should preclude reverse causality, and finding comparable results in both designs for most indices, our study provides support for an effect of overall diet on depression outcomes.

Third, we only included studies that used statistical adjustment (as opposed to simple mean comparisons between groups for instance). However, given the heterogeneity in the assessment of covariates, the comparability between studies is limited. All studies took age, sex (when relevant), energy intake and sociodemographic factors into account and the majority also included lifestyle factors and cardiometabolic markers; however, many of these used heterogeneous measures: some only adjusted for BMI, whereas others had a full cardiometabolic profile (blood pressure, cholesterol, diabetes, etc.). Also, a few studies did not include smoking nor physical activity [27, 52, 71, 76], which are common correlates to diet quality and therefore the “effect” of diet quality observed in these studies may be a proxy of a healthy overall lifestyle. However, most studies do adjust for other health behaviors and the weight of the data suggests that the relationship between diet quality and depression is independent of other health behaviors, as well as income, education, and body weight. The majority of longitudinal analyses investigated incident depression, i.e., excluded prevalent depression at baseline, except three that only adjusted for baseline symptoms/use of antidepressants [25, 46, 71]. Some cross-sectional studies included anti-depressant use or history of depression as covariates [44, 54, 57, 59, 63, 78], but no clear trend was observed in terms of effect size or significance of the estimates produced when comparing these with the studies that did not.

Fourth, the vast majority of the studies included in this systematic review were conducted in high income countries (Australia, France, Greece, Ireland, Japan, Netherlands, Norway, Spain, UK, US), with only seven studied in low-and-middle income countries (Brazil [72] and Iran [49, 53, 54, 56, 59, 64]. Hence, the generalizability of the findings to low-and-middle income countries is limited. Moreover, we did not want to include an age limit and our systematic review includes three studies on adolescents [25, 49, 64]. Psychological disorders may express differently during adolescence as opposed to later in life, but the exclusion of those studies did not change the overall results and conclusions. Therefore, considering all the above limitations, extra care should be applied when using and interpreting the meta-analysis estimates.

Conclusions

Our review shows that there is observational evidence to suggest that both adhering to a healthy diet, in particular a traditional Mediterranean diet, and avoiding a pro-inflammatory diet is associated with reduced risk of depressive symptoms or clinical depression. That the majority of recovered studies were cross-sectional in design, with the problem of reverse causality being acute in the context of diet and depression, there is a clear need for more prospective studies. Moreover, while recent intervention studies provide preliminary evidence [97, 98], further well-powered clinical trials are required to assess the role of dietary patterns in the prevention of onset, severity, and recurrence of depressive episodes.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgments

Funding:

MK is supported by the Medical Research Council (MRC K013351), NordForsk, and the Academy of Finland (311492). The funding bodies had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author contributions

CL and TA conducted the searches and data extraction. AB was responsible for resolving any discordance. CL and TA drafted the manuscript. CL conducted the statistical analysis. FJ, ASV, GDB, MK, and AB were responsible for interpreting the results and critically revising the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Felice Jacka has received: (1) competitive Grant/Research support from the Brain and Behaviour Research Institute, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), Australian Rotary Health, the Geelong Medical Research Foundation, the Ian Potter Foundation, The University of Melbourne; (2) industry support for research from Meat and Livestock Australia, Woolworths Limited, the A2 Milk Company, Be Fit Foods; (3) philanthropic support from the Fernwood Foundation, Wilson Foundation, the JTM Foundation, the Serp Hills Foundation, the Roberts Family Foundation, the Waterloo Foundation and; (4) travel support and speakers honoraria from Sanofi-Synthelabo, Janssen Cilag, Servier, Pfizer, Network Nutrition, Angelini Farmaceutica, Eli Lilly and Metagenics. Felice Jacka has written two books for commercial publication. All other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

The original online version of this article was revised: Following publication of this article, Camille Lassale contacted the journal to request an addition to the ‘Conflict of Interest’ declaration.

Change history

11/21/2018

This article was originally published under standard licence, but has now been made available under a CC BY 4.0 license. The PDF and HTML versions of the paper have been modified accordingly.

Change history

3/4/2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41380-021-01056-7

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41380-018-0237-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Depression fact sheet 2018 [Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/.

- 2.Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C, Chey T, Jackson JW, Patel V, et al. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis 1980-2013. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:476–93. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Disease GBD, Injury I, Prevalence C. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1211–59. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Mental health in the workplace 2017 [Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/world-mental-health-day/2017/en/.

- 5.van Zoonen K, Buntrock C, Ebert DD, Smit F, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Beekman AT, et al. Preventing the onset of major depressive disorder: a meta-analytic review of psychological interventions. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:318–29. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burcusa SL, Iacono WG. Risk for recurrence in depression. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:959–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Black CN, Bot M, Scheffer PG, Cuijpers P, Penninx BW. Is depression associated with increased oxidative stress? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;51:164–75. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang L, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Liu L, Zhang X, Li B, et al. The effects of psychological stress on depression. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13:494–504. doi: 10.2174/1570159X1304150831150507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marx Wolfgang, Moseley Genevieve, Berk Michael, Jacka Felice. Nutritional psychiatry: the present state of the evidence. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2017;76(4):427–436. doi: 10.1017/S0029665117002026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schuch Felipe B., Vancampfort Davy, Firth Joseph, Rosenbaum Simon, Ward Philip B., Silva Edson S., Hallgren Mats, Ponce De Leon Antonio, Dunn Andrea L., Deslandes Andrea C., Fleck Marcelo P., Carvalho Andre F., Stubbs Brendon. Physical Activity and Incident Depression: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2018;175(7):631–648. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17111194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akbaraly TN, Brunner EJ, Ferrie JE, Marmot MG, Kivimaki M, Singh-Manoux A. Dietary pattern and depressive symptoms in middle age. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195:408–13. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.058925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomez-Pinilla F. Brain foods: the effects of nutrients on brain function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:568–78. doi: 10.1038/nrn2421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bourre JM. Effects of nutrients (in food) on the structure and function of the nervous system: update on dietary requirements for brain. Part 1: micronutrients. J Nutr Health Aging. 2006;10:377–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bourre JM. Effects of nutrients (in food) on the structure and function of the nervous system: update on dietary requirements for brain. Part 2: macronutrients. J Nutr Health Aging. 2006;10:386–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bloch MH, Hannestad J. Omega-3 fatty acids for the treatment of depression: systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:1272–82. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molendijk M, Molero P, Ortuno Sanchez-Pedreno F, Van der Does W, Martinez-Gonzalez MA. Diet quality and depression risk: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Affect Disord. 2017;226:346–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lai JS, Hiles S, Bisquera A, Hure AJ, McEvoy M, Attia J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary patterns and depression in community-dwelling adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:181–97. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.069880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khalid S, Williams CM, Reynolds SA. Is there an association between diet and depression in children and adolescents? A systematic review. Br J Nutr. 2016;116:2097–108. doi: 10.1017/S0007114516004359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y, Lv MR, Wei YJ, Sun L, Zhang JX, Zhang HG, et al. Dietary patterns and depression risk: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2017;253:373–82. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rahe C, Unrath M, Berger K. Dietary patterns and the risk of depression in adults: a systematic review of observational studies. Eur J Nutr. 2014;53:997–1013. doi: 10.1007/s00394-014-0652-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Psaltopoulou T, Sergentanis TN, Panagiotakos DB, Sergentanis IN, Kosti R, Scarmeas N. Mediterranean diet, stroke, cognitive impairment, and depression: a meta-analysis. Ann Neurol. 2013;74:580–91. doi: 10.1002/ana.23944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–5. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beydoun MA, Wang Y. Pathways linking socioeconomic status to obesity through depression and lifestyle factors among young US adults. J Affect Disord. 2010;123:52–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winpenny Eleanor M, van Harmelen Anne-Laura, White Martin, van Sluijs Esther MF, Goodyer Ian M. Diet quality and depressive symptoms in adolescence: no cross-sectional or prospective associations following adjustment for covariates. Public Health Nutrition. 2018;21(13):2376–2384. doi: 10.1017/S1368980018001179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mamplekou E, Bountziouka V, Psaltopoulou T, Zeimbekis A, Tsakoundakis N, Papaerakleous N, et al. Urban environment, physical inactivity and unhealthy dietary habits correlate to depression among elderly living in eastern Mediterranean islands: the MEDIS (MEDiterranean ISlands Elderly) study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2010;14:449–55. doi: 10.1007/s12603-010-0091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skarupski KA, Tangney CC, Li H, Evans DA, Morris MC. Mediterranean diet and depressive symptoms among older adults over time. J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;17:441–5. doi: 10.1007/s12603-012-0437-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chinn S. A simple method for converting an odds ratio to effect size for use in meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2000;19:3127–31. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20001130)19:22<3127::AID-SIM784>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sterne JA, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JP, Terrin N, Jones DR, Lau J, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d4002. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hodge A, Almeida OP, English DR, Giles GG, Flicker L. Patterns of dietary intake and psychological distress in older Australians: benefits not just from a Mediterranean diet. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25:456–66. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212001986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Exebio JC, Zarini GG, Exebio C, Huffman FG. Healthy Eating Index scores associated with symptoms of depression in Cuban-Americans with and without type 2 diabetes: a cross sectional study. Nutr J. 2011;10:135. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-10-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Forsyth AK, Williams PG, Deane FP. Nutrition status of primary care patients with depression and anxiety. Aust J Prim Health. 2012;18:172–6. doi: 10.1071/PY11023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hernandez-Galiot A, Goni I. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet pattern, cognitive status and depressive symptoms in an elderly non-institutionalized population. Nutr Hosp. 2017;34:338–44. doi: 10.20960/nh.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuczmarski MF, Cremer Sees A, Hotchkiss L, Cotugna N, Evans MK, Zonderman AB. Higher Healthy Eating Index-2005 scores associated with reduced symptoms of depression in an urban population: findings from the Healthy Aging in Neighborhoods of Diversity Across the Life Span (HANDLS) study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:383–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quehl R, Haines J, Lewis SP, Buchholz AC. Food and mood: diet quality is inversely associated with depressive symptoms in female university students. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2017;78:124–8. doi: 10.3148/cjdpr-2017-007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tangney CC, Young JA, Murtaugh MA, Cobleigh MA, Oleske DM. Self-reported dietary habits, overall dietary quality and symptomatology of breast cancer survivors: a cross-sectional examination. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;71:113–23. doi: 10.1023/A:1013885508755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bertoli S, Spadafranca A, Bes-Rastrollo M, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Ponissi V, Beggio V, et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet is inversely related to binge eating disorder in patients seeking a weight loss program. Clin Nutr. 2015;34:107–14. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacka FN, Kremer PJ, Leslie ER, Berk M, Patton GC, Toumbourou JW, et al. Associations between diet quality and depressed mood in adolescents: results from the Australian Healthy Neighbourhoods Study. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2010;44:435–42. doi: 10.3109/00048670903571598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jacka FN, Rothon C, Taylor S, Berk M, Stansfeld SA. Diet quality and mental health problems in adolescents from East London: a prospective study. Social Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48:1297–306. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0623-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pagliai Giuditta, Sofi F., Vannetti F., Caiani S., Pasquini G., Molino Lova R., Cecchi F., Sorbi S., Macchi C. Mediterranean Diet, Food Consumption and Risk of Late-Life Depression: The Mugello Study. The journal of nutrition, health & aging. 2018;22(5):569–574. doi: 10.1007/s12603-018-1019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shivappa N, Hebert JR, Veronese N, Caruso MG, Notarnicola M, Maggi S, et al. The relationship between the dietary inflammatory index (DII) and incident depressive symptoms: a longitudinal cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2018;235:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Veronese N, Stubbs B, Noale M, Solmi M, Luchini C, Maggi S. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with better quality of life: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104:1403–9. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.136390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rius-Ottenheim N, Kromhout D, Sijtsma FPC, Geleijnse JM, Giltay EJ. Dietary patterns and mental health after myocardial infarction. PLoS ONE [Electron Resour] 2017;12:e0186368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adjibade M, Assmann KE, Andreeva VA, Lemogne C, Hercberg S, Galan P, et al. Prospective association between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and risk of depressive symptoms in the French SU.VI.MAX cohort. Eur J Nutr. 2017;10:10. doi: 10.1007/s00394-017-1405-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lai JS, Oldmeadow C, Hure AJ, McEvoy M, Byles J, Attia J. Longitudinal diet quality is not associated with depressive symptoms in a cohort of middle-aged Australian women. Br J Nutr. 2016;115:842–50. doi: 10.1017/S000711451500519X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanchez-Villegas A, Delgado-Rodriguez M, Alonso A, Schlatter J, Lahortiga F, Serra Majem L, et al. Association of the Mediterranean dietary pattern with the incidence of depression: the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra/University of Navarra follow-up (SUN) cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:1090–8. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanchez-Villegas A, Henriquez-Sanchez P, Ruiz-Canela M, Lahortiga F, Molero P, Toledo E, et al. A longitudinal analysis of diet quality scores and the risk of incident depression in the SUN Project. BMC Med. 2015;13:197. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0428-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tehrani AN, Salehpour A, Beyzai B, Farhadnejad H, Moloodi R, Hekmatdoost A, et al. Adherence to Mediterranean dietary pattern and depression, anxiety and stress among high-school female adolescents. Mediterr J Nutr Metab. 2018;11:73–83. doi: 10.3233/MNM-17192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beydoun MA, Fanelli Kuczmarski MT, Beydoun HA, Shroff MR, Mason MA, Evans MK, et al. The sex-specific role of plasma folate in mediating the association of dietary quality with depressive symptoms. J Nutr. 2010;140:338–47. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.113878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adjibade Moufidath, Lemogne Cédric, Julia Chantal, Hercberg Serge, Galan Pilar, Assmann Karen E., Kesse-Guyot Emmanuelle. Prospective association between adherence to dietary recommendations and incident depressive symptoms in the French NutriNet-Santé cohort. British Journal of Nutrition. 2018;120(3):290–300. doi: 10.1017/S0007114518000910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Loprinzi PD, Mahoney S. Concurrent occurrence of multiple positive lifestyle behaviors and depression among adults in the United States. J Affect Disord. 2014;165:126–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.04.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rahmani J, Milajerdi A, Dorosty-Motlagh A. Association of the Alternative Healthy Eating Index (AHEI-2010) with depression, stress and anxiety among Iranian military personnel. J R Army Med Corps. 2017;15:15. doi: 10.1136/jramc-2017-000791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saneei P, Hajishafiee M, Keshteli AH, Afshar H, Esmaillzadeh A, Adibi P. Adherence to Alternative Healthy Eating Index in relation to depression and anxiety in Iranian adults. Br J Nutr. 2016;116:335–42. doi: 10.1017/S0007114516001926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Akbaraly TN, Sabia S, Shipley MJ, Batty GD, Kivimaki M. Adherence to healthy dietary guidelines and future depressive symptoms: evidence for sex differentials in the Whitehall II study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97:419–27. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.041582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Khayyatzadeh SS, Mehramiz M, Mirmousavi SJ, Mazidi M, Ziaee A, Kazemi-Bajestani SMR, et al. Adherence to a Dash-style diet in relation to depression and aggression in adolescent girls. Psychiatry Res. 2017;259:104–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.09.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meegan AP, Perry IJ, Phillips CM. The association between dietary quality and dietary guideline adherence with mental health outcomes in adults: a cross-sectional analysis. Nutrients. 2017;9:05. doi: 10.3390/nu9030238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Perez-Cornago A, Sanchez-Villegas A, Bes-Rastrollo M, Gea A, Molero P, Lahortiga-Ramos F, et al. Relationship between adherence to Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet indices and incidence of depression during up to 8 years of follow-up. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20:2383–92. doi: 10.1017/S1368980016001531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]