Abstract

Infections and inflammatory processes have been associated with the development of schizophrenia and affective disorders; however, no study has yet systematically reviewed all available studies on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) immune alterations. We aimed to systematically review the CSF immunological findings in schizophrenia spectrum and affective disorders. We identified all studies investigating CSF inflammatory markers in persons with schizophrenia or affective disorders published prior to March 23, 2017 searching PubMed, CENTRAL, EMBASE, Psychinfo, and LILACS. Literature search, data extraction and bias assessment were performed by two independent reviewers. Meta-analyses with standardized mean difference (SMD) including 95% confidence intervals (CI) were performed on case-healthy control studies. We identified 112 CSF studies published between 1942–2016, and 32 case-healthy control studies could be included in meta-analyses. Studies varied regarding gender distribution, age, disease duration, treatment, investigated biomarkers, and whether recruitment happened consecutively or based on clinical indication. The CSF/serum albumin ratio was increased in schizophrenia (1 study [54 patients]; SMD = 0.71; 95% CI 0.33–1.09) and affective disorders (4 studies [298 patients]; SMD = 0.41; 95% CI 0.23–0.60, I2 = 0%), compared to healthy controls. Total CSF protein was elevated in both schizophrenia (3 studies [97 patients]; SMD = 0.41; 95% CI 0.15–0.67, I2 = 0%) and affective disorders (2 studies [53 patients]; SMD = 0.80; 95% CI 0.39–1.21, I2 = 0%). The IgG ratio was increased in schizophrenia (1 study [54 patients]; SMD = 0.68; 95% CI 0.30–1.06), whereas the IgG Albumin ratio was decreased (1 study [32 patients]; SMD = −0.62; 95% CI −1.13 to −0.12). Interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels (7 studies [230 patients]; SMD = 0.55; 95% CI 0.35–0.76; I2 = 1%) and IL-8 levels (3 studies [95 patients]; SMD = 0.46; 95% CI 0.17–0.75, I2 = 0%) were increased in schizophrenia but not significantly increased in affective disorders. Most of the remaining inflammatory markers were not significantly different compared to healthy controls in the meta-analyses. However, in the studies which did not include healthy controls, CSF abnormalities were more common, and two studies found CSF dependent re-diagnosis in 3.2–6%. Current findings suggest that schizophrenia and affective disorders may have CSF abnormalities including signs of blood-brain barrier impairment and inflammation. However, the available evidence does not allow any firm conclusion since all studies showed at least some degree of bias and vastly lacked inclusion of confounding factors. Moreover, only few studies investigated the same parameters with healthy controls and high-quality longitudinal CSF studies are lacking, including impact of psychotropic medications, lifestyle factors and potential benefits of anti-inflammatory treatment in subgroups with CSF inflammation.

Subject terms: Diagnostic markers, Schizophrenia, Depression

Introduction

Immunological mechanisms in mental disorders have become an area of significant interest [1], and several studies have associated infections and autoimmune diseases with an increased risk of specifically schizophrenia and affective disorders [2–4]. Studies have also shown increased levels of peripheral pro-inflammatory markers [5–11] and genes involved in regulation of the immune system in both schizophrenia and depression [12]. Furthermore, beneficial effects of anti-inflammatory treatment have been found in depression [13] and subgroups with psychotic disorders [14].

However, knowledge is sparse regarding the prevalence of abnormal immunological findings in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of people with severe mental disorders. CSF is the biological material closest to the brain that can be easily assessed and lumbar puncture is a routine procedure in neurological but not (yet) in psychiatric practice. Nonetheless, CSF studies have revealed increased CSF/serum albumin ratio in individuals with schizophrenia and affective disorders [6, 15–25] indicating increased blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability. Other studies found elevated CSF cell count [15, 16, 20, 26, 27], IgG index [16, 21], and the presence of oligoclonal bands [15, 16, 18, 20, 21] which could be indicators of inflammation and intrathecal immunoglobulin production. Also, a meta-analysis found several specific infectious agents to be associated with schizophrenia; however, most studies were based on blood and not CSF, and control groups consisted typically of non-healthy subjects [28]. Another meta-analysis found increased CSF levels of interleukin 1β (IL-1β), IL-6, and IL-8 in patients with severe mental disorders [29]. Despite these intriguing findings, no systematic review has hitherto gathered all the knowledge on infectious and inflammatory CSF abnormalities among patients with severe mental disorders.

Hence, most knowledge on the role of the immune system in mental disorders stems from studies on severe mental disorders, i.e., schizophrenia and affective disorders. Therefore, we aimed to conduct the first systematic review of all CSF studies examining inflammatory markers and infections in persons with schizophrenia spectrum or affective disorders, including meta-analyses of studies with healthy controls. Furthermore, we included the potential clinical implications of a CSF test, risk of adverse events and risk of bias.

Methods

The study protocol was a priori uploaded on PROSPERO (ID: CRD42017058938) and is available as online supplementary file.

Study selection and search method

In this systematic review we included studies investigating inflammatory markers and infections in the CSF of persons with schizophrenia spectrum disorders or affective disorders, fulfilling the following criteria:

Investigation of CSF markers related to inflammation or infections as defined under our primary outcomes.

Inclusion of persons diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum or affective disorders according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) or International Classification of Diseases (ICD) or similar classifications that might have been used before DSM and ICD implementation.

Publications in peer-reviewed journals.

Publications in English.

Studies from all time periods with study subjects in all ages, sexes, and races were included. We included both studies without controls and studies with healthy or non-healthy control groups, but only studies with healthy controls were used for the meta-analysis. The search was performed until March 23, 2017 using PubMed, CENTRAL, EMBASE, Psychinfo, and LILACS with medical subject headings (MESH) or similar when possible or text word terms: ((psychosis OR psychotic syndrome OR psychotic OR psychotic symptoms OR schizophrenia OR schizophreniform disorder OR schizoaffective OR depression OR major depressive disorder OR bipolar disorder) AND (cerebrospinal fluid OR CSF) AND (blood-brain barrier OR inflammation OR infection OR albumin OR protein OR cell count OR immunoglobulin OR IgG OR oligoclonal bands OR interleukins OR cytokine OR autoimmune disease OR autoimmunity OR immunology OR immune system OR psychoneuroimmunology OR lymphocyte OR macrophage OR C-reactive protein OR autoantibodies OR T cells OR complement)). Reference lists of relevant reviews were searched for additional studies. Two investigators (SO and SWB) examined titles and abstracts to remove irrelevant reports and examined full texts to determine compliance with inclusion criteria.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

Basic CSF findings: cell count, total protein, albumin, and albumin ratio.

CSF inflammatory markers: immunoglobulins, oligoclonal bands, and cytokines.

Specific CSF antibodies: antibodies directed against infectious agents as an indicator of preceding or current infection and auto-antibodies.

Secondary outcomes

Correlation between CSF findings and serum findings, psychotropic medication, and psychiatric symptoms, respectively.

Change in diagnosis following CSF analyses.

Adverse events in relation to lumbar puncture, e.g., headache.

Data extraction and bias assessment

Two authors (SO and OKF) extracted data using a pre-piloted structured form not blinded to study results, author names or institutions. This included bibliographical data and participant description. Authors were contacted by e-mail in case of missing details with a reminder sent in case of no response. Two authors (SO and OKF) conducted bias assessment according to the Newcastle-Ottawa criteria for case–control studies as suggested by the Cochrane collaboration (eMethods).

Statistical analysis

The primary analyses were conducted using RevMan 5.0. When fixed-effects analysis and the random-effects analysis resulted in similar results, only findings from the random effects analysis were reported, but in case of discrepancies both results were reported. We conducted analysis using the standardized mean difference (SMD) since we expected differences in assays. SMD is the mean difference in outcome between cases and controls divided by the pooled standard deviation (SD) giving the result of a unit free effect size. By convention, SMD effect sizes of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 are considered small, medium and large effect sizes. Our conclusions were based on the SMD even though we also present results from mean difference. The chi-squared test for heterogeneity will be used to provide an indication of between-trial heterogeneity. In addition, the degree of heterogeneity observed in the results was quantified using the I2 statistic, which can be interpreted as the percentage of variation observed between the trials attributable to between trial differences rather than sampling error (chance).

Post-hoc analyses

First, since CSF analysis techniques have improved over time, we performed sensitivity analyses on studies published after the year 2000. Second, we divided patients with psychosis into acute (inpatient treatment) and chronic (recruited in an outpatient setting) psychosis and performed analyses if there were at least two studies in each group, i.e., acute versus chronic.

Results

Search results and study characteristics

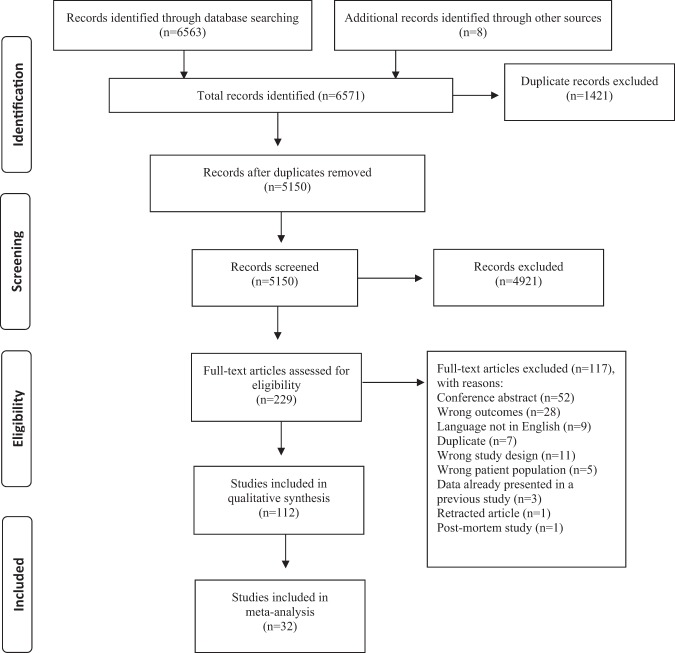

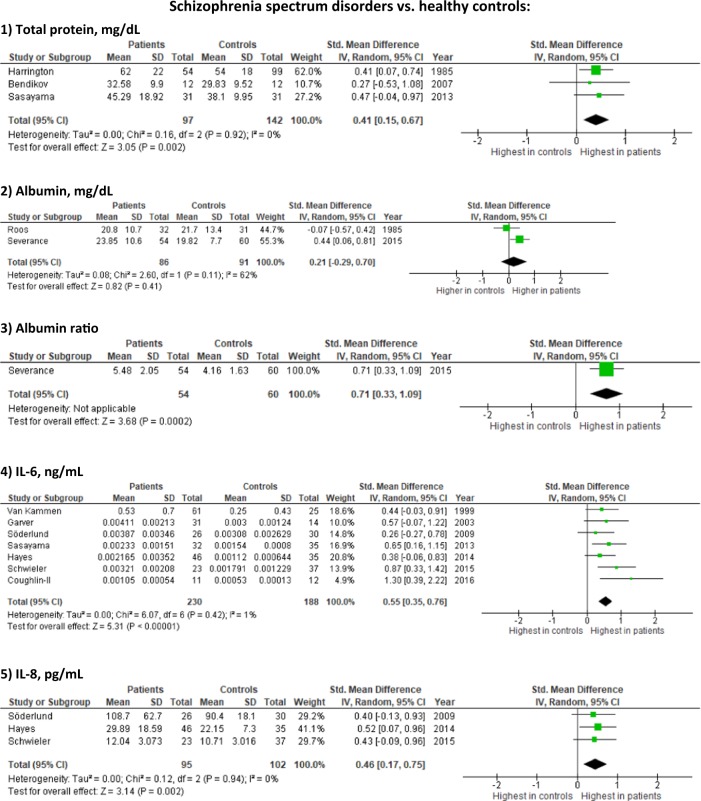

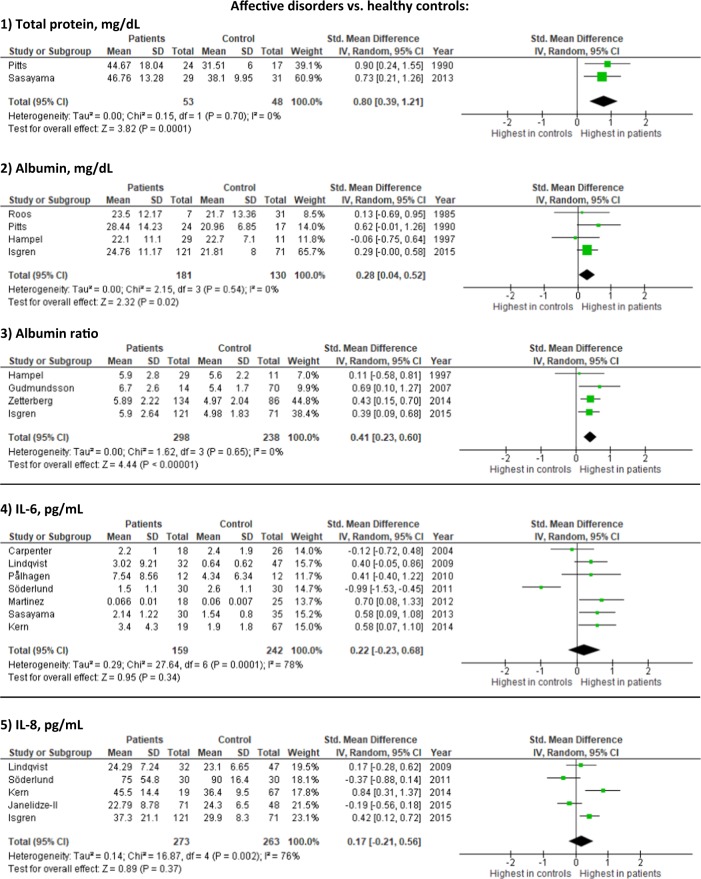

We identified 6571 studies (Fig. 1), of which 229 were assessed for full-text inspection. A total of 112 studies investigated CSF immune-related alterations, out of which 38 studies included control groups consisting solely of healthy controls. Data from 32 studies had data necessary for conducting meta-analyses, either published or send to us by the authors. Study characteristics are described in Table 1. Briefly, studies varied regarding gender distribution, age, disease duration, treatment, investigated biomarkers, and whether recruitment happened consecutively or based on clinical indication. In the following sections, the meta-analysis results are presented first (the findings on each specific CSF marker are shown in Table 2 and eTable 1 with forest plots in Figure 2 and eFigure 1) followed by a summary of the remaining CSF studies without healthy controls. Additional analyses only including studies published after the year 2000 supported the primary analyses (eFigure 2). The study characteristics, baseline data, and results for studies without controls or with non-healthy controls are shown in eTables 2 and 3, while results from the studies combining cases with schizophrenia spectrum and affective disorders are presented in the Results.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of literature search and study selection

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics from CSF studies with healthy control subjects

| Studies included in the meta-analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia spectrum disorders | |||||||

| Study | Case subjects | Healthy control subjects | Outcome and results included in meta-analysis | CSF study method | |||

| N, diagnosis (diagnostic tool) | No. (%) of males/mean age (year) | Psychotropic medication status | N | No. (%) of males/mean age (year) | |||

| Roos [112]a | 32, schizophrenia (SADS and PSE) | NA/NA | No medication for ≥ 2 weeks | 31 | NA/NA | Albumin, IgG and IgG-albumin ratio | Isoelectric focusing (IEF) |

| Harrington [113] | 54, schizophrenia (DSM-3) | Male/female ratio = 1.8/35 | Two cases without medication | 99 | Male/female ratio = 1.13/41 | Total protein | Two-dimensional electrophoresis |

| Kirch [25]b | 46, schizophrenia (DSM-3) | 31 (67)/29.9 | Some cases without medication ≥ 4 weeks | 20 | 16 (80)/54.1 | IgG index. ↑Albumin ratio in 10 cases (22%) and 1 control (5%) p = 0.08). ↔ No correlation albumin ratio or IgG with antipsychotic treatment |

Patient samples: rate nephelometry Control values: radial immunodiffusion |

| El-Mallakh [79] | 27, schizophrenia, schizoaffect (DSM-3-R) | 20 (74)/31.6 | Some cases did not receive medication for 4–6 weeks | 11 | 9 (82)/30.3 | IL-1alpha and IL-2 ↔ No correlation between IL-2 and PSAS scores | ELISA |

| Licinio [34] | 10, schizophrenia (DSM-3-R) | 10 (100)/38.5 | No medication ≥ 2 weeks | 10 | 10 (100)/35.1 |

IL-1alpha and IL-2 cell count normal in cases and controls |

ELISA |

| Katila [35] | 14, schizophrenia (DSM-3-R) | 9 (64)/42.8 | All patients received medication | 9 | 5 (56)/38.3 | IL-1beta, normal cell count, IL-6: undetectable in cases and controls ↔ No correlation between serum and CSF IL-1beta | ELISA |

| Rapaport [114] | 60, schizophrenia (DSM-3-R) | 34 (57)/29 | All patients received medication | 21 | 11 (52)/27 | IL-1alpha and IL-2 | Competitive enzyme immunoassay |

| Vawter [115] | 44, schizophrenia (NA) | 34 (77)/34.5 | NA | 19 | 13 (68)/30.2 | TGF-beta1, TGF-beta2 | ELISA |

| Van Kammen [82] | 61, schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (DSM-3-R) | 61 (100)/38.1 | All patients received medication | 25 | 25 (100)/35.0 |

IL-6 No correlation between CSF IL-6 and measures of psychosis |

ELISA |

| Nikkilä [44] | 19, schizophrenia (DSM-4) for (11 for neopterin, 8 for MIP-1) |

Neopterin: 5 (45)/31 MIP-1 alpha: 5 (63)/34 |

No medication ≥ 3 months | 10/8 |

Neopterin: 7 (70)/34 MIP-1 alpha: 5 (63)/31 |

Neopterin and MIP-1 alpha. Infection markers, albumin ratio: normal in cases and controls. ↔ No correlation between neopterin or MIP-1 alpha and BPRS symptoms | Radioimmunoassay |

| Garver [80] | 31, schizophrenia (DSM-4) | 28 (90)/34.1 | No medication for 2–7 days | 14 | 10 (71)/32.9 |

IL-6 Non-significant trend for IL-6 inversely correlated with SAPS scale |

Sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| Bendikov [116] | 12, schizophrenia (DSM-4) | 7 (58)/38.9 | 10 cases received medication | 12 | 7 (58)/40.5 | Total protein | Western blot analysis |

| Söderlund [90] | 26, schizophrenia (DSM-4) | 26 (100)/27.5 | 25 cases received medication | 30 | 30 (100)/25.4 | IL-1beta, IL-6, IL-8. IL-2, IL-4, GM-CSF, IFN-gamma, TNF-alpha, IL-5, IL-10: not detectable or only in low concentration. ↔ No correlation IL-1β, IL-6 or IL-8 and antipsychotic dose | Sandwich-immunoassay-based protein-array system |

| Sasayama [84]a | 32, schizophrenia (DSM-4) | 20 (63)/40.8 | Most cases received medication | 35 | 21 (60)/41.3 | IL-6, cell count and total protein. ↔ No correlation between serum and CSF IL-6 and antipsychotic dose or PANSS symptoms | ELISA |

| Hayes [117] | 46, schizophrenia (DSM-4) | 36 (78)/25.8 | No medication | 35 | 21 (60)/26.4 | IL-6, IL-6R, IL-8, C3, MCP-2, and TNFR2 | ELISA |

| Schwieler [85] | 23, schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder (DSM-4) | 15 (65)/median men = 37, women = 35 | All cases received medication | 37 | 23 (62)/men: median 24; women: median 23 |

IL-6, IL-8. IFN-gamma, IL-1beta, IL-4: undetectable IL-2, IL-10, IL-18, TNF-alpha, IFN-alpha-2a: only detected in limited number of CSF samples ↔ No correlation IL-6 or IL-8 and symptoms (GAF, BPRS) |

Electrochemiluminescence detection Liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry |

| Severance [118]c | 105, schizophrenia (DSM-4) | 67 (64)/28.62 | 75 cases without medication | 61 | 30 (49)/27.16 | Albumin, albumin ratio, IgG, IgG ratio, IgG index | ELISA |

| Coughlin [102]d | 14, schizophrenia (DSM-4) | 11 (79)/24.1 | 2 cases without treatment for 1 month | 16 | 9 (56)/24.9 | IL-6. Correlation between CSF and plasma IL-6 within the total study population and the patient cohort alone | V-Plex Custom Human Biomarkers kit |

| Affective disorders | |||||||

| Roos [112]a | 7, depression (SADS and PSE) | NA | No medication ≥ 2 weeks | 31 | NA | Albumin, IgG and IgG-albumin ratio | Isoelectric focusing (IEF) |

| Pitts [46]e | 24, Affective disorders (DSM-3-R) | 13 (54)/37.5 | Most patients received medication | 17 | 8 (47)/29.8 | Total protein and albumin. Normal cell count in cases and controls ↔ No correlation total protein and depressive symptoms (HAMD) | Protein electrophoresis |

| Hampel [119] | 29, MDD (DSM-3-R and ICD-10) | 9 (31)/71.6 | NA | 11 | 6 (55)/72.8 | Albumin, albumin ratio, IgG, and IgG ratio | Immunonephelometric |

| Hampel [120]f | 29, MDD (DSM-3-R and ICD-10) | 9 (31)/71.6 | NA | 11 | 6 (55)/72.8 | IgG index and oligoclonal bands | Isoelectric focusing (IEF) |

| Carpenter [121] | 18, unipolar depression (DSM-4) | 9 (50)/38.3 | No major psychotropic drugs for ≥ 3 weeks | 26 | 12 (46)/32.7 | IL-6 | ELISA |

| Gudmundsson [89] | 14, MDD and dysthymia (DSM-3-R) | 0 (0)/NA | NA | 70 | 0 (0)/NA | Albumin ratio ↔ No correlation between biomarker levels and psychotropic medication | ELISA |

| Lindqvist [8]g | 32, MDD or depression NOS (DSM-3) | NA/NA | No medication for 16 days (mean) | 47 | 40 (85)/37 | IL-1 beta, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-alpha | ELISA |

| Pålhagen [122] | 12, depression (DSM-3/4) | 7 (58)/62.7 | No antidepressants | 12 | 12(100)/29.4 | IL-6 | Mass fragmentographic method |

| Söderlund [123] | 30, bipolar disorder type 1 or 2 (DSM-4) | 30 (100)/43.2 | 2 cases without medication | 30 | 30 (100)/25.4 | IL-1 beta, IL-6, and IL-8. IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, GM-CSF, IFN-γ, TNF–α: undetectable or close to the detection limit of the assay | Immunoassay-based protein array multiplex system |

| Martinez [124] | 18, MDD (DSM-3-R) | 8 (44)/40.4 | No medication for 2 weeks | 25 | 13 (52)/29.9 | IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-alpha | ELISA |

| Janelidze [81]g | 75, MDD, dysthymia, depression NOS or bipolar (DSM-3-R) | NA/NA | No medication for 14.7 days (mean) | 43 | 36 (84)/38.8 | IP-10, Eotaxin, MIP-1b, MCP-1, MCP-4 and TARC | Ultra-sensitive chemokine multiplex immunoassay |

| Sasayama [84]a | 30, MDD (DSM-4) | 19 (63)/42.7 | Most subjects received medication | 35 | 21 (60)/41.3 | IL-6, cell count and protein. ↔ No correlation CSF and serum IL-6, IL-6 and antidepressant dose or HAMD-21 symptoms | ELISA |

| Kern [77]h | 19, Major and minor depression (DSM-4) | 0 (0)/72.8 | 5 cases received antidepressant medication | 67 | 0 (0)/72.4 |

IL-6, IL-8. No correlation CSF IL-6 and MADRS symptoms (p = 0.450) Higher CSF IL-8 correlated with higher MADRS scores (p = 0.003) |

Human Pro-inflammatory II 4-Plex Assay Ultra- Sensitive Kit |

| Zetterberg [88] | 134, bipolar, schizoaffective manic type, cyclothymia (DSM-4) | 54 (40)/36 (28–50) = median (IQR) | NA | 86 | 38 (44)/34 (28–46) = median (IQR) |

Albumin ratio. ↔ No correlation between albumin ratio and psychotropic medication, apart from antipsychotic medication. Higher albumin ratio in those treated with antipsychotic medication compared to those treated with other psychotropic medication |

Immunonephelometry |

| Isgren [86] | 121, bipolar spectrum disorder (DSM-4-TR) | 47 (38.8)/36.0 | Most cases received medication | 71 | 26 (36.6)/32.0 | Albumin ratio, albumin, and IL-8. Correlation IL-8 with lithium and antipsychotic. ↔ No correlation IL-8 and other drugs or psychiatric symptoms (CGI, MADRS, YMRS) | Immunoassays |

| Janelidze [87]g | 71, MDD, depr NOS, dysthymia (DSM-3-R) | NA/NA | No medication for 15 days (mean) | 48 | 39 (81)/38 | IL-8. ↔ No correlation IL-8 and MADRS symptoms (p > 0.05) | ELISA |

| Studies not included in the meta-analysis | |||||||

| Ueno [125]i | 139, schizophrenia (NA) | 83 (60)/Range 12–67 | NA | 6 | NA | Lower total protein in cases, no information regarding statistical difference to controls | Polarographic method and paper electrophoresis |

| Deutsch [43] | 19, schizophrenia, 11, depression (NA) | NA/33.6, 48.1 and 63.8 | NA | 6 | NA/30.5 | ↔ Total protein: no difference between cases and controls after adjustment for age (p > 0.10) | Liquid scintillation spectrometry |

| Preble [126] | 65, MDD, schizophrenia spectrum, bipolar, schizotypal personality disorder, (DSM-3) | NA | NA | 20 | NA |

Interferon: not present in cases or controls CMV IgM: present in 9 cases (13.8%) |

ELISA |

| Pazzaglia [27]j | 240, bipolar disorder or unipolar recurrent depression (DSM-3) | 95 (40)/ NA | No medication ≥ 2 weeks | 55 | 34 (62)/ NA | ↑Cell count in 3 cases (1.25%), normal in controls. ↑Total protein in cases compared with controls. ↔ No correlation total protein and psychiatric symptoms (Bunney-Hamburg Rating Scale) | DuPont ACA discrete clinical analyzer |

| Stübner [62] | 20, MDD (DSM-3-R and ICD-10) | 7 (35)/67.3 | 1 case without medication | 20 | 12 (60)/65.8 | ↓IL-6 and sIL-6r in cases compared with controls (p < 0.001) ↔ sgp130: no difference between cases and controls (p = 0.152) | ELISA |

| Leweke [36] | 85, schizophrenia anti-psychotic naïve: 36k, first psychotic episode; 10 prior antipsychotic treatment; 39 inpatients medicated (DSM-4) | 28 (78), 8 (80) and 30 (77)/29.1, 33.7 and 30.5 | According to group | 73 | 52 (71)/28.0 |

Cell count, albumin ratio, oligoclonal bands, IgG index: normal in cases ↑CMV (p < 0.0033) and toxoplasma gondii (p < 0.001) IgG in cases from group 1 compared with controls ↔ CMV and toxoplasma IgG for group 2 + 3 and HSV-1 IgG for all groups did not differ from controls |

ELISA |

| Coughlin [127] | 15, schizophrenia (NA) | 11 (73)/21.9 | 1 case without medication | 15 | 12 (80)/23.6 | ELISA | |

NA not available, MDD major depressive disorder, DSM diagnostics and statistics manual, ICD International Classification of Diseases, PSE present stata examination, SADS schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia, HAMD Hamilton depression score, MADRS Montgomery and Aasberg depression rating scale, YMRS young mania rating scale, CGI, clinical global impression scale, PSAS psychiatric symptom assessment scale, BPRS brief psychiatric rating scale, PANSS positive and negative symptom scale, SAPS scale for assessment of positive symptoms, GAF global assessment of functioning, IL interleukin, IFN interferon, TNF tumor necrosis factor, Ig immunoglobulin, TGF transforming growth factor, GM-CSF granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, MIP macrophage inflammatory protein, MCP monocyte chemoattractant protein, IP inducible protein, CMV cytomegalovirus, HSV Herpes simplex virus

aThe study included both cases with psychosis and affective disorders and is thus shown in the table twice

bData on 24 of the 46 cases is presented in Kirch et al. [21], but that study is not included in the meta-analysis

cSome analyses were performed on a smaller subsample

dOnly 11 cases and 12 controls underwent LP

eOnly 13 patients and 8 controls were included in the albumin analyses

fSame patients as in Hampel [119], only new results included in the meta-analysis

gPatients were examined after a suicide attempt

hThe cases were included from the same original cohort used in Gudmundsson [89], however with the investigation of other CSF outcomes

iSome analyses were only performed in subgroups of the cases

j125 patients and 8 controls had >1 medication-free LP and in these cases, mean values were used for most analyses

k2 cases from group 1 did not have available CSF samples

Table 2.

CSF immune related markers in patients with schizophrenia spectrum or affective disorders compared to healthy controls

| CSF Marker | Studies | Cases | Control | SMD | 95% CI | p-value | I 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia vs healthy controls | |||||||

| Cell count | 1 | 32 | 31 | 0.19 | −0.31 to 0.68 | 0.46 | NA |

| Total protein | 3 | 97 | 142 | 0.41 | 0.15 to 0.67 | 0.002 | 0% |

| Albumin | 2 | 86 | 91 | 0.21 | −0.29 to 0.70 | 0.41 | 62% |

| Albumin ratio | 1 | 54 | 60 | 0.71 | 0.33 to 1.09 | 0.0002 | NA |

| IgG | 2 | 86 | 91 | −0.12 | −0.93 to 0.69 | 0.77 | 85% |

| IgG Ratio | 1 | 54 | 60 | 0.68 | 0.30 to 1.06 | 0.0004 | NA |

| IgG/Albumin ratio | 1 | 32 | 31 | −0.62 | −1.13 to −0.12 | 0.02 | NA |

| IgG Index | 2 | 100 | 80 | 0.25 | −0.07 to 0.56 | 0.13 | 7% |

| IL-1 alpha | 3 | 72 | 33 | −0.16 | −0.91 to 0.60 | 0.68 | 43% |

| IL-1 Beta | 2 | 40 | 39 | −0.13 | −4.96 to 4.71 | 0.96 | 98% |

| IL-2 | 3 | 97 | 42 | 0.18 | −0.49 to 0.85 | 0.60 | 64% |

| IL-6 | 7 | 230 | 188 | 0.55 | 0.35 to 0.76 | <0.00001 | 1% |

| IL-6R | 1 | 46 | 35 | −0.24 | −0.68 to 0.20 | 0.28 | NA |

| IL-8 | 3 | 95 | 102 | 0.46 | 0.17 to 0.75 | 0.002 | 0% |

| Neopterin | 1 | 11 | 10 | −0.05 | −0.91 to 0.81 | 0.91 | NA |

| MIP-1 alfa | 1 | 8 | 8 | −0.70 | −1.72 to 0.32 | 0.18 | NA |

| C3 | 1 | 46 | 35 | 0.00 | −0.44 to 0.44 | 1.00 | NA |

| MCP-2 | 1 | 46 | 35 | 0.26 | −0.18 to 0.71 | 0.24 | NA |

| TNFR2 | 1 | 46 | 35 | 0.06 | −0.38 to 0.50 | 0.78 | NA |

| TGFB1 | 1 | 44 | 19 | 0.29 | −0.25 to 0.83 | 0.29 | NA |

| TGFB2 | 1 | 44 | 19 | −0.14 | −0.68 to 0.40 | 0.61 | NA |

| Affective Disorders vs healthy controls | |||||||

| CSF Marker | Studies | Cases | Control | Mean ES | 95% CI | p-value | I 2 |

| Cell count | 1 | 29 | 31 | 0.40 | −0.11 to 0.91 | 0.13 | NA |

| Total protein | 2 | 53 | 48 | 0.80 | 0.39 to 1.21 | 0.0001 | 0% |

| Albumin | 4 | 181 | 130 | 0.28 | 0.04 to 0.52 | 0.02 | 0% |

| Albumin ratio | 4 | 298 | 238 | 0.41 | 0.23 to 0.60 | <0.00001 | 0% |

| IgG | 2 | 36 | 42 | −0.22 | −0.75 to 0.32 | 0.43 | 0% |

| IgG Ratio | 1 | 29 | 11 | 0.33 | −0.37 to 1.02 | 0.36 | NA |

| IgG/Albumin ratio | 1 | 7 | 31 | −0.56 | −1.39 to 0.28 | 0.19 | NA |

| IgG Index | 1 | 29 | 11 | 0.22 | −0.48 to 0.91 | 0.54 | NA |

| IL-1 | 1 | 18 | 25 | 0.61 | −0.01 to 1.23 | 0.05 | NA |

| IL-1 Beta | 2 | 62 | 77 | 0.80 | −0.99 to 2.59 | 0.38 | 96% |

| IL-6 | 7 | 159 | 242 | 0.22 | −0.23 to 0.68 | 0.34 | 78% |

| IL-8 | 5 | 273 | 263 | 0.17 | −0.21 to 0.56 | 0.37 | 76% |

| TNF-alpha | 2 | 50 | 72 | 0.24 | −0.12 to 0.61 | 0.19 | 0% |

| Eotaxin-1 | 1 | 75 | 43 | −0.33 | −0.71 to 0.04 | 0.08 | NA |

| IP-10 | 1 | 75 | 43 | −0.17 | −0.55 to 0.20 | 0.37 | NA |

| MIP-1B | 1 | 75 | 43 | −0.26 | −0.64 to 0.12 | 0.17 | NA |

| MCP-1 | 1 | 75 | 43 | −0.28 | −0.65 to 0.10 | 0.15 | NA |

| MCP-4 | 1 | 75 | 43 | −0.76 | −1.15 to −0.37 | 0.0001 | NA |

| TARC | 1 | 75 | 43 | −0.57 | −0.95 to −0.19 | 0.004 | NA |

Fig. 2.

Forest plots on selected results from studies investigating immune-related CSF markers in schizophrenia spectrum and affective disorders (the remaining forest plots are shown in eFigure 1)

Bias assessment

All studies included in the meta-analysis showed at least some degree of bias (eTable 4). The majority of studies were biased concerning the actual case definition (16/32), representativeness of cases (28/32), random selection of controls (20/32), comparability between cases and controls (21/32) and ascertainment of exposure (27/32).

Primary outcomes

CSF cell count, total protein, albumin, and albumin ratio

Schizophrenia spectrum disorders

In the meta-analysis comparing to healthy controls, total protein (3 studies [97 patients]; SMD: 0.41; 95% CI 0.15–0.67; I2 = 0%) and albumin ratios (1 study [54 patients]; SMD: 0.71; 95% CI 0.33–1.09) were elevated, whereas albumin and cell counts were not significantly increased.

Across all CSF studies, cell counts ranged from normal [18, 19, 23, 30–36] to increased levels in up to 3.4% of the cases [20, 26] with no difference comparing to neurological controls [37]. Total protein levels varied from normal [18, 22, 30, 31] to increased in up to 42.2% of cases [6, 20, 26, 38, 39], with no difference in the studies comparing to neurological, psychiatric, surgical or healthy controls [32, 40–43]. Albumin levels ranged from normal [18, 22, 30, 31] to increased in up to 16% of cases [6, 24, 39], with no difference in the studies comparing with psychiatric controls [40] or a combined group of healthy and psychiatric controls [38]. The albumin ratio ranged from normal [36, 37, 44, 45] to increased in up to 53% of the cases [6, 19–25], with no difference in the studies comparing to healthy controls [25] or a combined group of healthy and psychiatric controls [38].

Affective disorders

In the meta-analysis comparing to healthy controls, cell count was not significantly increased, whereas total protein levels (2 studies [53 patients]; SMD: 0.80; 95% CI 0.39–1.21, I2 = 0%), albumin (4 studies [181 patients]; SMD = 0.28; 95% CI 0.04–0.52, I2 = 0) and albumin ratio were increased (4 studies [298 patients]; SMD = 0.41; 95% CI 0.23–0.60, I2 = 0).

Across all CSF studies, cases had normal [18, 46] or increased cell counts in up to 13.1% [15, 16, 27], with no difference in the studies comparing to neurological controls [15, 47]. Total protein ranged from normal [18, 47, 48] to increased levels in up to 36.6% of cases [16, 27, 49], with no difference in the studies comparing to psychiatric or neurological controls [16, 40, 47]. Albumin was not different compared to somatically ill or psychiatric controls [40, 50]. The albumin ratio was increased in up to 44% of cases [15–18] but with no difference in the studies comparing with neurological controls [15, 16].

CSF immunoglobulins

Schizophrenia spectrum disorders

In the meta-analysis comparing to healthy controls, IgG/albumin ratio was decreased (1 study [32 patients]; SMD = −0.62; 95% CI −1.13 to −0.12), IgG ratio was increased (1 study [54 patients]; SMD = 0.68; 95% CI 0.30–1.06), whereas IgG levels and the IgG index were not significantly increased.

In the other CSF studies, immunoglobulins were increased in 3% of the cases [51], whereas IgG and the IgG index were normal [19, 22, 36, 50] or increased in up to 33% [6, 19, 21, 24, 52] of cases, respectively. In the studies comparing with surgical, neurological or a combined group of psychiatric and healthy controls, the IgG ratio, IgG, IgA and IgM were decreased [32, 53] or not different in cases [22, 38, 50]. Oligoclonal bands were absent in some reports [18, 36, 54] but present in up to 12.5% of cases in others [20, 21]. An intrathecal immunoglobulin synthesis was observed in none [18] to 7.2% of cases [20].

Affective disorders

In the meta-analysis, IgG levels, the IgG/albumin ratio, the IgG ratio and the IgG index were not significantly different compared to healthy controls.

In studies not included in the meta-analysis IgG was present in all cases [55], with increased levels of IgG [49] but within normal range IgG ratio [16]; however, the IgG index was significantly higher in cases in the one study comparing with neurological controls [16]. IgM was not present in cases [49, 55] while IgA was present in 23.3% [49, 55]. Oligoclonal bands were found in up to 12.5% of cases [15, 16, 18] with no difference in the studies comparing to neurological controls [15, 16]. Intrathecal immune response was present in none [18] to 30% of cases and significantly increased in the study comparing with neurological controls [16].

CSF interleukins

Schizophrenia spectrum disorders

In the meta-analysis comparing to healthy controls, IL-8 (3 studies [95 patients]; SMD = 0.46; 95% CI 0.17–0.75; I2 = 0%) and IL-6 (7 studies [230 patients]; SMD = 0.55; 95% CI 0.35–0.76; I2 = 1%) were significantly increased. In a post-hoc analysis, we found that IL-6 was significantly elevated in acute psychosis (SMD = 0.46; 95% CI 0.22–0.71; I2 = 1%) and chronic psychosis (SMD = 0.75; 95% CI 0.39 to 1.12; I2 = 0%) with the between-group difference being not significant (p = 0.20) (eFigure 3). The levels of IL-1alpha, IL-1beta and IL-2 were not statistically different from healthy controls.

In the studies not included in the meta-analysis, the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4 and IL-10 were present in 64 and 14% of cases, respectively. Concerning pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-2 was detected in 95%, IL-5 in 40%, IFN-gamma in 14%, TNF-beta in 41%, and TNF-alpha in 50% of cases [7]. Other studies found no difference to neurological controls in levels of IL-2, IL-6, and TNF alpha [33] or decreased levels of IL-1beta, sIL-2r [33], and TNF-alpha [56] compared to neurological and surgical controls. Interferon was reported to be absent [31] or present in up to 59% of cases [57–60] but with no difference in the study comparing to psychiatric controls [60].

Affective disorders

In the meta-analysis comparing to healthy controls, IL-1, IL-1beta, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-alpha were not significantly increased (Table 2, Fig. 2 and eFigure 1).

The studies comparing neurological [47, 61] and healthy [62] controls that were not included in the meta-analysis, showed that cases had decreased or unchanged levels of IL-6 [61–63], decreased levels of sIL-6r [62] and sIL-2r [47], increased levels of IL-1beta [61, 63], and unchanged levels of TNF-alpha [61] and sgp130 [62]. Moreover, a wide range of inflammatory markers were found to be similar in psychiatric patients compared to neurological controls (eTable 1) [63]. IL-7, IL-12, or granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) were not detected [63].

Specific CSF antibodies

Schizophrenia spectrum disorders

One study with healthy controls found increased CMV and toxoplasma gondii IgG in antipsychotic naïve cases [36], but the data were not suitable for meta-analysis. Other studies found that CMV antibodies [48, 64–68] were either undetectable [48, 64–68] or present (in up to 18.5% of cases; 43,66,67), but this was not different from surgical [32] or psychiatric and healthy controls [38, 69]. HSV-1 or 2 antibodies were undetectable in one [19] but detectable in the other studies (present in up to 69% of cases) [48, 57–59, 64, 67, 70], but without difference in the studies comparing to neurological, surgical controls, psychiatric or healthy controls [30, 32, 36, 38].

Studies found antibodies in cases against mumps in 2.9% [64] (but decreased compared with surgical controls [32]), VZV in 5.7% [64], tick-borne encephalitis virus in 7.3%, orbivirus lipovnik in up to 2.9%, choriomeningitis virus in 5.3% [57], and nucleotide sequences homologous to those of known retroviruses in 20% of cases [71], whereas others did not find CSF antibodies against infectious agents [19, 30, 39, 64, 66, 72, 73]. There was no difference in the levels of antibodies towards measles [32], rubella [30, 32], VZV [32], adenovirus [32], vaccinia [38], or influenza [38] between cases and surgical [30, 32], psychiatric or healthy controls [38].

Antibodies against neuronal cell surface antigens were detected in up to 2.4% and against intracellular onconeural antigens in up to 2.1% of cases but none against intracellular synaptic antigens in cases [20]. Others found anti-brain antibodies in 48.1% of cases [74], with a study finding dopamine IgG in 100% of cases and significantly elevated compared to the 41% of neurological controls [22]. No difference of antibodies against myelin basic protein and glial fibrillary acidic protein was observed compared to surgical controls [31].

Affective disorders

Studies found CSF antibodies against toxoplasma gondii in 52.5% [16], HSV in up to 85%, EBV in up to 60% [16, 48], CMV in 3% [72] and BDV in up to 50% [16, 45] of cases. Others found no antibodies against measles [48], CMV [48], or treponema pallidum [73] in cases. There were no antibodies against intracellular antigens or neuronal cell surface antigens [75, 76].

Secondary outcomes

Correlation between CSF findings and psychiatric symptoms

Correlations have been found between albumin and IgG with SANS scores [6], and higher IL-8 levels with higher MADRS scores [77]. However, most authors reported no correlation between psychiatric symptoms and the following CSF findings: total protein [27, 46], impairment of the BBB [51], IL-1alpha [78], IL-1beta [61], IL-2 [78, 79], IL-6 [80–85], sIL-6r [24], IL-8 [85–87], IL-10 [83], IL-15 [63], TNF-alpha [56], neopterin [44], MIP-1alpha [44], MCP-1 [63], and lymphocyte activational stage [40].

Correlation between CSF findings and psychotropic medication

A total of 17 studies investigated the association between medication and CSF findings. CSF analysis in patients on antipsychotic medication revealed a tendency towards normalization of the CSF cytological alterations [37]. There was a correlation between higher albumin ratio and IL-1alpha with antipsychotic treatment [78, 88], IL-8 and the use of lithium or antipsychotics but not the use of other psychotropic medication [86]. However, most studies found no correlation between antipsychotic or antidepressant medication and CSF levels of IgG, IgM, IgA [53], IgG index [25], total protein [73], albumin ratio [88, 89], CMV IgM [45], lymphocytic profile [23], IL-1 beta, IL-2, sIL-2r, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF alpha [33, 78, 84, 85, 90], or impairment of the BBB [19, 21, 25, 51, 91].

Change of diagnosis after CSF analyses

Two studies reported that 3.2% (N = 5/155) [92], respectively, 6% (N = 4/63) [93] of patients with initial diagnoses of affective [93] or schizophrenia spectrum disorders [92, 93] received a revised diagnosis following CSF analyses, including infections and autoimmune disorders.

Adverse events after lumbar puncture

Only one study reported on adverse events related to the lumbar puncture and found that mild to moderate adverse events (mostly headaches or local pain at the puncture site) occurred in 10.3% of the cases; 1.3% experienced severe post-lumbar puncture headache with nausea [92].

Discussion

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis of the available evidence from eight decades on immune-related CSF investigations in schizophrenia and affective disorders, including previously unpublished data acquired from contacts to the study authors. Our meta-analysis pointed towards BBB impairment with increased albumin ratio and total protein in schizophrenia and affective disorders, and increased levels of albumin in affective disorders. The increased IgG CSF/serum ratio (and a non-significantly increased IgG index) in schizophrenia might suggest intrathecal IgG production. Moreover, IL-6 and IL-8 levels were increased in schizophrenia but not significantly increased in affective disorders. However, all studies included in the meta-analysis showed at least some degree of bias, specifically concerning representativeness of cases and ascertainment of exposure.

The major limitation was the small number of studies with healthy controls; hence, the largest meta-analysis included 4 studies with 302 cases. Several meta-analyses were based on one study. The remaining part of the systematic review consisted of studies with non-healthy control groups or without a control group lowering the reliability. Second, detailed study protocols were commonly unavailable, case groups were often unsystematically identified and consisted of various diagnostic categories with variable disease duration, severity and age of onset, making it difficult to apply the results to specific patient groups. Third, CSF analysis varied according to sampling time points and sensitivity of the cytokine assays, and many studies did not disclose the number of samples above the detection limit. In addition, assays have developed over time and hence studies used different techniques, and particularly the broad spectrum of new and more sensitive methods has been emphasized by several studies [94, 95]. Fourth, the majority of studies were cross-sectional. Fifth, we could not perform meta-analyses on studies investigating the importance of psychotropic medication nor could we identify longitudinal studies investigating psychotropic medication. Furthermore, studies with healthy controls examining a broad range of immune-related CSF markers were lacking. Sixth, we only included articles written in English and geographic biases might occur as clinicians may be more likely to perform lumbar punctures in areas where infections with treatable infectious agents are prevalent. Seventh, several studies did not match on important factors such as age or gender (eTable 4) and did not control for important confounders such as BMI, smoking or diet. These confounding factors have been shown to largely influence the associations between at least peripheral inflammatory markers and depression [96], which need to be considered in future studies also for CSF inflammatory markers. Finally, we had no knowledge regarding longitudinal data relating to clinical state and severity of the disorder or response to medications.

The major findings in our meta-analysis were increased albumin ratios and total protein suggestive of BBB leakage or dysfunction. Supporting this, studies have found an increased albumin ratio in up to 53% with schizophrenia spectrum disorders [6, 19–25] and 44% with affective disorders [15–18]. An impaired BBB may leave the brain more vulnerable to harmful substances in the blood, including immune components. It might also be an indicator of inflammation within the central nervous system (CNS), which is also indicated by the non-significantly increased CSF cell counts.

Our meta-analysis reveals evidence for intrathecal IgG production in a subset of psychiatric patients [20, 93] and oligoclonal bands were increased in up to 12.5% of cases [15, 16, 18, 20, 21], which may indicate acute or chronic inflammation, an “immunological scar” from previous inflammation of brain tissue, immunoglobulin production or a local B cell immune response in certain subgroups of patients [97].

Interleukins are produced by the immune system and regulate many aspects of inflammation and the immune response. The present meta-analyses showed increased levels of IL-6 and IL-8 in schizophrenia spectrum disorders, whereas in affective disorders all cytokines levels were non-significantly increased. Other recent meta-analyses revealed evidence of increased CSF levels of IL-1β in schizophrenia and bipolar disorders and increased levels of IL-6 and IL-8 in schizophrenia and depression [29, 98]. IL-6 stimulates CRP production by hepatocytes, and IL-8 primarily induces chemotaxis and phagocytosis. Increased levels of several peripheral cytokines have also been reported for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression [99–101]. Although CSF cytokine levels reflect CNS inflammation more precisely, peripheral IL-6 can reach the CNS through the choroid plexus or because of increased BBB permeability [102].

The studies on CSF antibodies could not be included in meta-analyses. Nonetheless, studies found antibodies against CNS tissue in up to 100% [20, 22, 74] and HSV-1 antibodies in up to 69% of cases with schizophrenia spectrum disorders [48, 57–59, 64, 70], but the results for most of the other infectious agents were rather conflicting. Antibodies against HSV [16, 48], Toxoplasma gondii [16] and EBV [16, 48] had the strongest associations with affective disorders. Furthermore, studies without healthy controls have found signs of CNS pathology in up to 41% of cases [93].

Antipsychotic medication has been found to increase BBB permeability in animal studies [103] and affect immune cells in the CNS [23, 104–106], highlighting the importance of evaluating the effect of psychotropic medication when analyzing CSF; however, the evidence for antidepressants is conflicting [107, 108]. Cross-sectional studies mostly found no association between CSF parameters and psychotropic medication apart from a correlation between a higher albumin ratio [88], higher IL-1alpha [78], and IL-8 [86] with antipsychotic treatment, and none of the studies investigating this aspect longitudinally.

Concerning associations with clinical symptomatology, the only CSF parameters that correlated with symptom scores were IL-8 (depression) [77], respectively albumin and IgG (schizophrenia) [6]. Increased inflammatory blood markers (e.g., CRP and IL-6) correlated with greater overall symptom severity in patients with depression, in particular with neuro-vegetative symptoms (e.g., sleep, appetite) [109–111]. However, only few studies explored associations between CSF markers and symptom severity or correlations between immune markers in serum vs. CSF, and we found conflicting results regarding correlation between IL-6 levels in CSF and serum [84, 102].

Conclusion and perspectives

The present systematic review and meta-analysis suggests that subgroups of patients with schizophrenia spectrum or affective disorders may have CSF pathology with signs of BBB impairment, intrathecal antibody synthesis and elevated levels of inflammatory markers, autoantibodies and immunoglobulins. However, CSF findings varied greatly and important confounders were often not accounted for limiting any firm conclusions regarding CSF pathology in patients with depression or schizophrenia. Therefore, future studies should be longitudinal with systematic and standardized collection of CSF samples over time in larger study populations with healthy control subjects. Preferably, these studies should include newly diagnosed patients who are naive to psychotropic drugs, with CSF measurements prior to and at several time points after psychotropic drug initiation, with adjustments for variables that can affect the immune-related markers, e.g., smoking and BMI. CSF and peripheral immune markers, in combination with peripheral blood tests and brain scans, might aid in future trials on immune-modulating add-on treatment for subgroups of mental disorders. Finally, the emerging role of the immune system and CNS inflammation in mental disorders necessitates improved imaging methods, better methods for sampling small amounts of CSF using small needles and guided insertions and identification of brain derived proteins in blood. Adverse events after lumbar puncture was rare and 3.2–6% of patients received a revised (somatic) diagnosis following CSF analysis, suggesting that lumbar puncture can be an important supplemental diagnostic examination in psychiatric patient’s potentially influencing treatment.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The present study was partly funded by the Independent Research Fund Denmark (grant number 7025-00078B) and by an unrestricted grant from The Lundbeck Foundation (grant number R268-2016-3925). The sponsor had no role in the acquisition of the data, interpretation of the results or the decision to publish the findings.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41380-018-0220-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Benros ME, Mortensen PB, Eaton WW. Autoimmune diseases and infections as risk factors for schizophrenia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1262:56–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benros ME, Waltoft BL, Nordentoft M, Østergaard SD, Eaton WW, Krogh J, et al. Autoimmune diseases and severe infections as risk factors for mood disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:812. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wium-Andersen MK, Ørsted DD, Nordestgaard BG. Elevated C-reactive protein and late-onset bipolar disorder in 78 809 individuals from the general population. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208:138–45. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.150870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eaton WW, Pedersen MG, Nielsen PR, Mortensen PB. Autoimmune diseases, bipolar disorder, and non-affective psychosis. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12:638–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00853.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nikkila H, Müller K, Ahokas A, Miettinen K, Andersson LC, Rimón R. Abnormal distributions of T-lymphocyte subsets in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with acute schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1995;14:215–21. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(94)00039-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Müller N, Ackenheil M. Immunoglobulin and albumin content of cerebrospinal fluid in schizophrenic patients: Relationship to negative symptomatology. Schizophr Res. 1995;14:223–8. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(94)00045-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mittleman BB, Castellanos FX, Jacobsen LK, Rapoport JL, Swedo SE, Shearer GM. Cerebrospinal fluid cytokines in pediatric neuropsychiatric disease. J Immunol. 1997;159:2994–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindqvist D, Janelidze S, Hagell P, Erhardt S, Samuelsson M, Minthon L, et al. Interleukin-6 is elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid of suicide attempters and related to symptom severity. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:287–92. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howren MB, Lamkin DM, Suls J. Associations of depression with C-reactive protein, IL-1, and IL-6: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med [Internet] 2009;71:171–86. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181907c1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haapakoski R, Mathieu J, Ebmeier KP, Alenius H, Kivimäki M. Cumulative meta-analysis of interleukins 6 and 1β, tumour necrosis factor α and C-reactive protein in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;49:206–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khandaker GM, Pearson RM, Zammit S, Lewis G, Jones PB. Association of serum interleukin 6 and C-reactive protein in childhood with depression and psychosis in young adult life: a population-based longitudinal study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:1121–8. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ripke S, Neale BM, Corvin A, Walters JTR, Farh KH, Holmans Pa, et al. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511:421–7. doi: 10.1038/nature13595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Köhler O, Benros ME, Nordentoft M, Farkouh ME, Iyengar RL, Mors O, et al. Effect of anti-inflammatory treatment on depression, depressive symptoms, and adverse effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:1381–91. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akhondzadeh S, Tabatabaee M, Amini H, Ahmadi Abhari SA, Abbasi SH, Behnam B. Celecoxib as adjunctive therapy in schizophrenia: a double-blind, randomized and placebo-controlled trial. Schizophr Res. 2007;90:179–85. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuld A, Uhr M, Pollmächer T. Oligoclonal bands and specific antibody indices in human narcolepsy. Somnologie. 2004;8:71–4. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stich O, Andres TA, Gross CM, Gerber SI, Rauer S, Langosch JM. An observational study of inflammation in the central nervous system in patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17:291–302. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zachrisson OCG, Balldin J, Ekman R, Naesh O, Rosengren L, Ågren H, et al. No evident neuronal damage after electroconvulsive therapy. Psychiatry Res. 2000;96:157–65. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(00)00202-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bechter K, Herzog S, Behr W, Schüttler R. Investigations of cerebrospinal fluid in Borna disease virus seropositive psychiatric patients. Eur Psychiatry. 1995;10:250–8. doi: 10.1016/0924-9338(96)80302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bauer K, Kornhuber J. Blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier in schizophrenic patients. Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 1987;236:257–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00380949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Endres D, Perlov E, Baumgartner A, Hottenrott T, Dersch R, Stich O, et al. Immunological findings in psychotic syndromes: a tertiary care hospital’s CSF sample of 180 patients. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:476. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirch DG, Kaufmann CA, Papadopoulos NM, Martin B, Weinberger DR. Abnormal cerebrospinal fluid protein indices in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1985;20:1039–46. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(85)90002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergquist J, Bergquist S, Axelsson R, Ekman R. Demonstration of immunoglobulin G with affinity for dopamine in cerebrospinal fluid from psychotic patients. Clin Chim Acta. 1993;217:129–42. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(93)90159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nikkilä HV, Müller K, Ahokas A, Rimón R, Andersson LC. Increased frequency of activated lymphocytes in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with acute schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2001;49:99–105. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00218-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Müller N, Dobmeier P, Empl M, Riedel M, Schwarz M, Ackenheil M. Soluble IL-6 receptors in the serum and cerebrospinal fluid of paranoid schizophrenic patients. Eur Psychiatry. 1997;12:294–9. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(97)84789-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirch DG, Alexander RC, Suddath RL, Papadopoulos NM, Kaufmann CA, Daniel DG, et al. Blood-CSF barrier permeability and central nervous system immunoglobulin G in schizophrenia. J Neural Transm. 1992;89:219–32. doi: 10.1007/BF01250674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruetsch W, Bahr M, Skobba J, Dieter W. The group of dementia praecox patients with an increase of the protein content of the cerebrospinal fluid. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1942;95:669–79. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pazzaglia PJ, Post RM, Rubinow D, Kling Ma, Huggins TS, Sunderland T. Cerebrospinal fluid total protein in patients with affective disorders. Psychiatry Res. 1995;57:259–66. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02704-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arias I, Sorlozano A, Villegas E, Luna J, de D, et al. Infectious agents associated with schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2012;136:128–36. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang AK, Miller BJ Meta-analysis of cerebrospinal fluid cytokine and tryptophan catabolite alterations in psychiatric patients: comparisons between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression. Schizophr Bull. 2017; http://watermark.silverchair.com/api/watermark?token=AQECAHi208BE49Ooan9kkhW_Ercy7Dm3ZL_9Cf3qfKAc485ysgAAAigwggIkBgkqhkiG9w0BBgggIVMIICEQIBADCCAgoGCSqGSIb3DQEHATAeBglghkgBZQMEAS4wEQQMEH01BKZZ8m-rh_TXAgEQgIIB22UkgfAIyiJWMQdFvpNMM9erz3gA6UB93lP9uMxq_uFtJ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Rimon R, Nishmi M, Halonen P. Serum and CSF antibody levels to herpes simplex type 1, measles and rubella viruses in patients with schizophrenia. Ann Clin Res. 1978;10:291–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rimon RH, Halonen P, Lebon P, Heikkilä L, Frey H, Karhula P, et al. Antibrain antibodies and Interferon in the Serum and the Cerebrospinal Fluid of Patients with Schizophrenia1. Adv Biol Psychiatry. 1983;12:161–7. [Google Scholar]

- 32.King DJ, Cooper SJ, Earle JAP, Martin SJ, McFerran NV, Wisdom GB. Serum and CSF antibody titres to seven common viruses in schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1985;147:145–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.147.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barak V, Barak Y, Levine J, Nisman B, Roisman I. Changes in interleukin-1 beta and soluble interleukin-2 receptor levels in CSF and serum of schizophrenic patients. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 1995;6:61–9. doi: 10.1515/jbcpp.1995.6.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Licinio J, Seibyl JP, Altemus M, Charney DS, Krystal JH. Elevated CSF levels of interleukin-2 in neuroleptic-free schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1408–10. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.9.1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katila H, Hurme M, Wahlbeck K, Appelberg B, Rimon R. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid interleukin-1 beta and interleukin-6 in hospitalized schizophrenic patients. Neuropsychobiology. 1994;30:20–3. doi: 10.1159/000119130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leweke FM, Gerth CW, Koethe D, Klosterkötter J, Ruslanova I, Krivogorsky B, et al. Antibodies to infectious agents in individuals with recent onset schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;254:4–8. doi: 10.1007/s00406-004-0481-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nikkilä HV, Müller K, Ahokas A, Miettinen K, Rimón R, Andersson LC. Accumulation of macrophages in the CSF of schizophrenic patients during acute psychotic episodes. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1725–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.11.1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Albrecht P, Boone E, Torrey EF, Hicks JT, Daniel N. Raised cytomegalovirus-antibody level in cerebrospinal fluid of schizophrenic patients. Lancet. 1980;2:769–72. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)90386-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Torrey E, Albrecht P, Behr D. Permeability of the blood-brain barrier in psychiatric patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142:657–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.5.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoerster SJ, Hillman F, Bohls S, Lara F, Thurman N. Cerebrospinal fluid in mental diseases (a study using paper electrophoresis) Dis Nerv Syst. 1963;24:357–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Selecki B, Todd P, Westwood A, Kraus J. Cerebro-spinal fluid and serum protein profiles in deteriorated epileptics, mental defectives with epilepsy, and schizophrenics. Med J Aust. 1964;2:751–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shanmugam A. A study of cerebrospinal fluid proteins in schizophrenia. J Indian Med Assoc. 1971;57:206–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deutsch SI, Mohs RC, Levy MI, Rothpearl AB, Stockton D, Horvath T, et al. Acetylcholinesterase activity in CSF in schizophrenia, depression, Alzheimer’s disease and normals. Biol Psychiatry. 1983;18:1363–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nikkilä HV, Ahokas A, Wahlbeck K, Rimón R, Andersson LC. Neopterin and macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha in the cerebrospinal fluid of schizophrenic patients: no evidence of intrathecal inflammation. Neuropsychobiology. 2002;46:169–72. doi: 10.1159/000067805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Torrey E, Yolken R, Winfrey J. Cytomegalovirus antibody in cerebrospinal fluid of schizophrenic patients detected by enzyme immunoassay. Science. 1982;216:892–4. doi: 10.1126/science.6281883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pitts AF, Carroll BT, Gehris TL, Kathol RG, Samuelson SD. Elevated CSF protein in male patients with depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1990;28:629–37. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(90)90401-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levine J, Barak Y, Chengappa K, Rapoport A, Antelman S, Barak V. Low CSF soluble interleukin 2 receptor levels in acute depression. Short Commun J Neural Transm. 1999;106:1011–5. doi: 10.1007/s007020050219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gotlieb-Stematsky T, Zonis J, Arlazoroff A, Mozes T, Sigal M, Szekely AG. Antibodies to Epstein-Barr virus, herpes simplex type 1, cytomegalovirus and measles virus in psychiatric patients. Arch Virol. 1981;67:333–9. doi: 10.1007/BF01314836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kumar A, Tewari SC, Lal N, Trivedi JK, Bahuguna LM. A study of abnormal CSF total proteins and immunoglobulins levels in patients of depression. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1986;30:103–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leonardi A, Cocito L, Tabaton M, Bartolini A, Roccatagliata G. CSF and serum IgG and albumin in schizophrenics. IRCS. Med Sci. 1982;10:812–3. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Axelsson R, Martensson E, Alling C. Impairment of the blood-brain barrier as an aetiological factor in paranoid psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;141:273–81. doi: 10.1192/bjp.141.3.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tiwari SG, Lal N, Trivedi JK, Sayeed J, Bahauguna LM. Immunoglobulin patterns in schizophrenic patients. Indian J Psychiatry. 1984;26:223–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Delisi LE, Weinberger DR, Potkin S, Neckers LM, Shiling DJ, Wyatt RJ. Quantitative determination of immunoglobulins in CSF and plasma of chronic schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1981;139:513–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.139.6.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schwarz MJ, Ackenheil M, Riedel M. Norbert Müller. Blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier impairment as indicator for an immune process in schizophrenia. Neurosci Lett. 1998;253:201–3. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00655-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tiwari SG, Lal N, Trivedi JK, Chaturvedi UC, Varma SL, Bahauguna LM. Immunoglobulins and viral antibodies in depressive patients. Indian J Psychiatry. 1990;32:318–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhu H, Wang D, Liu X. The reduction of CSF tumor necrosis factor alpha levels in schizophrenia: no correlations with psychopathology and coincident metabolic characteristics. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:2869–74. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S113549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Libíková H, Breier S, Kocisová M, Pogády J, Stünzner D, Ujházyová D. Assay of interferon and viral antibodies in the cerebrospinal fluid in clinical neurology and psychiatry. Acta Biol Med Ger. 1979;38:879–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Libíkowa H, Stancek D, Wiedermann V, Hasto J, Breier S. Psychopharmaca and electroconvulsive therapy in relation to viral antibodies and interferon. Exp Clin Study Arch Immunol Ther Exp. 1977;25:641–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Libíková H, Pogady J, Rajcani J, Skodacek I, Ciampor F, Kocisova M. Latent herpesvirus hominis 1 in the central nervous system of psychotic patients. Acta Virol. 1979;23:231–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roy A, Pickar D, Ninan P, Hooks J, Paul SM. A search for interferon in the CSF of chronic schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142:269. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.2.269a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Levine J, Barak Y, Chengappa K, Rapoport A, Rebey M, Barak V. Cerebrospinal cytokine levels in patients with acute depression. Neuropsychobiology. 1999;40:171–6. doi: 10.1159/000026615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stübner S, Schön T, Padberg F, Teipel SJ, Schwarz MJ, Haslinger A, et al. Interleukin-6 and the soluble IL-6 receptor are decreased in cerebrospinal fluid of geriatric patients with major depression: No alteration of soluble gp130. Neurosci Lett. 1999;259:145–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00916-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hestad KA, Engedal K, Whist JE, Aukrust P, Farup PG, Mollnes TE, et al. Patients with depression display cytokine levels in serum and cerebrospinal fluid similar to patients with diffuse neurological symptoms without a defined diagnosis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:817–22. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S101925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Srikanth S, Ravi V, Poornima KS, Shetty KT, Gangadhar BN, Janakiramaiah N. Viral antibodies in recent onset, nonorganic psychoses: correspondence with symptomatic severity. Biol Psychiatry. 1994;36:517–21. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)90615-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rimon R, Ahokas A, Palo J. Serum and cerebrospinal fluid antibodies to cytomegalovirus in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1986;73:642–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1986.tb02737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sierra-Honigmann AM, Carbone KM, Yolken RH. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) search for viral nucleic acid sequences in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;166:55–60. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Torrey EF, Peterson MR, Brannon WL, Carpenter WT, Post RM, Van Kammen DP. Immunoglobulins and viral antibodies in psychiatric patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;132:342–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.132.4.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shrikhande S, Hirsch SR, Coleman JC, Reveley MA, Dayton R. Cytomegalovirus and schizophrenia. A test of a viral hypothesis. Br J Psychiatry. 1985;146:503–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.146.5.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van Kammen DP, Mann L, Scheinin M, van Kammen WB, Linnoila M. Spinal fluid monoamine metabolites and anti-cytomegalovirus antibodies and brain scan evaluation in schizophrenia. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1984;20:519–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bartova L, Rajcani J, Pogady J. Herpes simplex virus antibodies in the cerebrospinal fluid of schizophrenic patients. Acta Virol. 1987;31:443–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Karlsson H, Bachmann S, Schroder J, McArthur J, Torrey EF, Yolken RH. Retroviral RNA identified in the cerebrospinal fluids and brains of individuals with schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:4634–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061021998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Deuschle M, Bode L, Heuser I, Schmider J, Ludwig H. Borna disease virus proteins in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with recurrent depression and multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1998;352:1828–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)79891-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Samuelson SD, Winokur G, Pitts AF. Elevated cerebrospinal fluid protein in men with unipolar or bipolar depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1994;35:539–44. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)90100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pandey RS, Gupta AK, Chaturvedi UC. Autoimmune model of schizophrenia with special reference to antibrain antibodies. Biol Psychiatry. 1981;16:1123–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Endres D, Dersch R, Hottenrott T, Perlov E, Maier S, van Calker D, et al. Alterations in cerebrospinal fluid in patients with bipolar syndromes. Front Psychiatry. 2016;7:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Endres D, Perlov E, Dersch R, Baumgartner A, Hottenrott T, Berger B, et al. Evidence of cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities in patients with depressive syndromes. J Affect Disord. 2016;198:178–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kern S, Skoog I, Börjesson-Hanson A, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Östling S, et al. Higher CSF interleukin-6 and CSF interleukin-8 in current depression in older women. Results from a population-based sample. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;41:55–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McAllister CG, Van Kammen DP, Rehn TJ, Miller AL, Gurklis J, Kelley ME, et al. Increases in CSF levels of interleukin-2 in schizophrenia: effects of recurrence of psychosis and medication status. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1291–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.9.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.El-Mallakh RS, Suddath RL, Wyatt RJ. Interleukin-1 alpha and interleukin-2 in cerebrospinal fluid of schizophrenic subjects. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1993;17:383–91. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(93)90072-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Garver DL, Tamas RL, Holcomb JA. Elevated interleukin-6 in the cerebrospinal fluid of a previously delineated Schizophrenia subtype. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1515–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Janelidze S, Ventorp F, Erhardt S, Hansson O, Minthon L, Flax J, et al. Altered chemokine levels in the cerebrospinal fluid and plasma of suicide attempters. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:853–62. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Van Kammen DP, McAllister-Sistilli CG, Kelley ME, Gurklis JA, Yao JK. Elevated interleukin-6 in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1999;87:129–36. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(99)00053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yao JK, Sistilli CG, Van Kammen DP. Membrane polyunsaturated fatty acids and CSF cytokines in patients with schizophrenia. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fat Acids. 2003;69:429–36. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2003.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sasayama D, Hattori K, Wakabayashi C, Teraishi T, Hori H, Ota M, et al. Increased cerebrospinal fluid interleukin-6 levels in patients with schizophrenia and those with major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:401–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schwieler L, Larsson MK, Skogh E, Kegel ME, Orhan F, Abdelmoaty S, et al. Increased levels of IL-6 in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with chronic schizophrenia—significance for activation of the kynurenine pathway. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2015;40:126–33. doi: 10.1503/jpn.140126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Isgren A, Jakobsson J, Pålsson E, Ekman CJ, Johansson AGM, Sellgren C, et al. Increased cerebrospinal fluid interleukin-8 in bipolar disorder patients associated with lithium and antipsychotic treatment. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;43:198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Janelidze S, Suchankova P, Ekman A, Erhardt S, Sellgren C, Samuelsson M, et al. Low IL-8 is associated with anxiety in suicidal patients: genetic variation and decreased protein levels. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;131:269–78. doi: 10.1111/acps.12339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zetterberg H, Jakobsson J, Redsäter M, Andreasson U, Pålsson E, Ekman CJ, et al. Blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier dysfunction in patients with bipolar disorder in relation to antipsychotic treatment. Psychiatry Res. 2014;217:143–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gudmundsson P, Skoog I, Waern M, Blennow K, Pálsson S, Rosengren L, et al. The relationship between cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers and depression in elderly women. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:832–8. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180547091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Söderlund J, Schröder J, Nordin C, Samuelsson M, Walther-Jallow L, Karlsson H, et al. Activation of brain interleukin-1β in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:1069–71. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Brettschneider J, Claus A, Kassubek J, Tumani H. Isolated blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier dysfunction: Prevalence and associated diseases. J Neurol. 2005;252:1067–73. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0817-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kranaster L, Koethe D, Hoyer C, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Leweke FM. Cerebrospinal fluid diagnostics in first-episode schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;261:529–30. doi: 10.1007/s00406-011-0193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bechter K, Reiber H, Herzog S, Fuchs D, Tumani H, Maxeiner HG. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis in affective and schizophrenic spectrum disorders: Identification of subgroups with immune responses and blood–CSF barrier dysfunction. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44:321–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Reiber H, Peter JB. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis: disease related data patterns and evaluation progams. J Neurol Sci. 2001;184:101–22. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(00)00501-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wildemann B, Oschmann P, Reiber H. Laboratory diagnosis in neurological disorders. 2010.

- 96.Powell TR, Gaspar H, Chung R, Keohane A, Gunasinghe C, Uher R, et al. Assessing 42 inflammatory markers in 321 control subjects and 887 major depressive disorder cases: BMI and other confounders and overall predictive ability for current depression. Biorxiv. 2018 doi: 10.1101/327239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wright Ben L. C., Lai James T. F., Sinclair Alexandra J. Cerebrospinal fluid and lumbar puncture: a practical review. Journal of Neurology. 2012;259(8):1530–1545. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6413-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Miller BJ, Buckley P, Seabolt W, Mellor A, Kirkpatrick B. Meta-analysis of cytokine alterations in schizophrenia: Clinical status and antipsychotic effects. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70:663–71. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Goldsmith DR, Rapaport MH, Miller BJ. A meta-analysis of blood cytokine network alterations in psychiatric patients: comparisons between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2016; http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/mp.2016.3%5Cnhttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26903267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 100.Potvin S, Stip E, Sepehry AA, Gendron A, Bah R, Kouassi E. Inflammatory cytokine alterations in Schizophrenia: a systematic quantitative review. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:801–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Liu H, Sham L, Reim EK, et al. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:446–57. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Coughlin JM, Wang Y, Ambinder EB, Ward RE, Minn I, Vranesic M, et al. In vivo markers of inflammatory response in recent-onset schizophrenia: a combined study using [(11)C]DPA-713 PET and analysis of CSF and plasma. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6:e777. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Saija A, Princi P, Imperatore C, De Pasquale R, Costa G. Ageing influences haloperidol‐induced changes in the permeability of the blood‐brain barrier in the rat. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1992;44:450–2. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1992.tb03644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Heiser P, Enning F, Krieg J, Vedder H. Effects of haloperiodol, clozapine and olanzapine on the survival of human neuronal and immune cells in vitro. J Psychopharmacol. 2007;21:851–6. doi: 10.1177/0269881107077221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hirata-Hibi M, Higashi S, Tachibana T, Watanabe N. Stimulated lymphocytes in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39:82–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290010058011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Torrey EF, Upshaw YD, Suddath R. Medication effect on lymphocyte morphology in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1989;2:385–90. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(89)90031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Elmorsy E, Al-Ghafari A, Almutairi FM, Aggour AM, Carter WG. Antidepressants are cytotoxic to rat primary blood brain barrier endothelial cells at high therapeutic concentrations. Toxicol Vitr. 2017;44:154–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2017.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lee JY, Kim HS, Choi HY, Oh TH, Yune TY. Fluoxetine inhibits matrix metalloprotease activation and prevents disruption of blood-spinal cord barrier after spinal cord injury. Brain. 2012;135:2375–89. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Krogh J, Benros ME, Jørgensen MB, Vesterager L, Elfving B, Nordentoft M. The association between depressive symptoms, cognitive function, and inflammation in major depression. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;35:70–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Yoon HK, Kim YK, Lee HJ, Kwon DY, Kim L. Role of cytokines in atypical depression. Nord J Psychiatry. 2012;66:183–8. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2011.611894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Köhler-Forsberg O, Buttenschøn HN, Tansey KE, Maier W, Hauser J, Dernovsek MZ, et al. Association between C-reactive protein (CRP) with depression symptom severity and specific depressive symptoms in major depression. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;62:344–50. http://ac.els-cdn.com.ep.fjernadgang.kb.dk/S0889159117300624/1-s2.0-S0889159117300624-main.pdf?_tid=5870ce64-9611-11e7-b44a-00000aab0f01&acdnat=1505038870_96534e22a803f45c0f79d9afbfc1f299 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 112.Roos R, Davis K, Meltzer H. Immunoglobulin studies in patients with psychiatric diseases. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42:124–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790250018002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Harrington MG, Merril CA, Tone EF. Differences in cerebrospinal fluid proteins between patients with schizophrenia and normal persons. Clin Chem. 1985;31:722–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rapaport MH, McAllister CG, Pickar D, Tamarkin L, Kirch DG, Paul SM. CSF IL-1 and IL-2 in medicated schizophrenic patients and normal volunteers. Schizophr Res. 1997;25:123–9. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(97)00008-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Vawter MP, Dillon-Carter O, Issa F, Wyatt RJ, Freed WJ. Transforming growth factors beta 1 and beta 2 in the cerebrospinal fluid of chronic schizophrenic patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1997;16:83–7. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(96)00143-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bendikov I, Nadri C, Amar S, Panizzutti R, De Miranda J, Wolosker H, et al. A CSF and postmortem brain study of d-serine metabolic parameters in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2007;90:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hayes LN, Severance EG, Leek JT, Gressitt KL, Rohleder C, Coughlin JM, et al. Inflammatory molecular signature associated with infectious agents in psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:963–72. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Severance EG, Gressitt KL, Alaedini A, Rohleder C, Enning F, Bumb JM, et al. IgG dynamics of dietary antigens point to cerebrospinal fluid barrier or flow dysfunction in first-episode schizophrenia. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;44:148–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hampel H, Kötter HU, Möller HJ. Blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier dysfunction for high molecular weight proteins in Alzheimer disease and major depression. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;11:78–87. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199706000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Hampel H, Kotter HU, Padberg F, Korschenhausen DA, Moller HJ Oligoclonal bands and blood--cerebrospinal-fluid barrier dysfunction in a subset of patients with Alzheimer disease: comparison with vascular dementia, major depression, and multiple sclerosis. [Internet]. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 1999;9–19. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med4&NEWS=N&AN=10192637 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 121.Carpenter LL, Heninger GR, Malison RT, Tyrka AR, Price LH. Cerebrospinal fluid interleukin (IL)-6 in unipolar major depression. J Affect Disord. 2004;79:285–9. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00460-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]