Abstract

Ancillary tests can be used for the diagnosis of brain death in cases wherein uncertainty exists regarding the neurological examination and apnoea test cannot be performed. Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography (TCD) is a useful, valid, non-invasive, portable, and repeatable ancillary test for the confirmation of brain death. Despite its varying sensitivity and specificity rates with regard to the diagnosis of the brain death, its clinical use has steadily increased in the intensive care unit because of its numerous superior properties. The use of TCD as an ancillary test for the diagnosis of brain death and cerebral circulatory arrest is discussed in the current review.

Keywords: Ancillary test, brain death, ultrasonography, Doppler, intensive care unit

Introduction

Brain death is the irreversible loss of clinical functions of the brain and brainstem. In the historical course, brain death was first defined by Mollaret and Goulon in 1959. In the definition in a group of patients under mechanical ventilator support, the term ‘Le coma de passe’ was used in the same way as in the current definition. They have determined in this group of patients the absence of spontaneous respiration, deep coma status, lack of reflexes, low blood pressure and loss of activity in electroencephalography (EEG).

As a result of the developments in organ transplantation, interest in brain death has increased, and organ transplantation from the donor who had brain death in 1963 for the first time has caused the need for regulation in the diagnosis and detection of brain death. The Harvard Report was first published in 1968 and was widely accepted in the medical field. Finally, in 2010, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) published an updated evidence-based guideline to detect brain death. In the AAN guideline, additional testing is recommended to confirm brain death in cases where neurological evaluation is not possible. Similarly, in our country, the regulation of organ and tissue transplant services published in 2012 recommended a ancillary test that evaluates brain circulation in cases where apnoea test is not performed (1–6).

Cerebral blood flow or neural functions are evaluated with the ancillary tests used in the diagnosis of brain death. Tests used to evaluate neural activity are EEG and evoked potentials. The main limitations of the tests in which neural activity is evaluated include artefacts and being influenced from metabolic changes and drugs. Cerebral angiography used to evaluate cerebral blood flow is accepted as the gold standard method in the diagnosis of brain death. The main disadvantages of this method are the need to get the patient out of the intensive care unit and the use of contrast agent (4–8).

Transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasonography, a method used to evaluate cerebral blood flow by ultrasonography, is non-invasive, can be performed at bedside, repeatable and does not require opaque substances; therefore, it is a reliable method for detecting cerebral circulatory arrest (Table 1) (1, 3, 5, 8, 9).

Table 1.

Confirmatory tests used to determine brain death

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| EEG | Applicable at bedside | Risk of electrical interference in intensive care settings |

| Non-invasive, no risk | False positive result | |

| Affected by metabolic changes and hypothermia | ||

| Cerebral angiography | Gold standard for the diagnosis of brain death | Invasive, needs contrast agents |

| Variable criteria for brain death detection | ||

| Available in a limited number of centres | ||

| MR angiography | Do not need contrast agents | Not practical for critically ill patient |

| Variable criteria for brain death | ||

| Limited number of studies | ||

| CT angiography | Available in many hospitals | Needs contrast agents |

| Variable criteria for brain death detection | ||

| Transcranial Doppler | Applicable at bedside | Acoustic window inadequacy |

| Non-invasive, no risk | ||

| Evoked potentials | Applicable at bedside | Reflects only the specific region of the brain |

| Non-invasive, no risk | High sensitivity, low specificity | |

EEG: electroencephalography; MR: magnetic resonance; CT: computed tomography

Historical course of TCD in the diagnosis of brain death

The first ultrasonography examination for brain death was performed for extracranial arteries. Yoneda et al. (10) performed Doppler ultrasonography for extracranial arteries in patients diagnosed with brain death and monitored systolic peaks and back and forth spectra in the main and internal carotid arteries. Doppler examination of intracranial arteries became possible in 1982 when Rune Aaslid presented TCD to clinical use. The basal arteries of the brain were examined, and the flow velocities were monitored dynamically by TCD. Currently, TCD is used as a confirmatory method not only in the detection of brain death but also in the diagnosis and follow-up of increased intracranial pressure and in the diagnosis of cerebral vasospasm, sepsis and associated encephalopathy (9, 11).

Conditions required before the TCD examination for the diagnosis of cerebral circulatory arrest

The prerequisites determined before the neurological examination in the diagnosis of brain death should be provided. Similarly, some prerequisites must be provided to determine the cerebral circulatory arrest correctly by TCD ultrasonography. These prerequisites are: (1) coma that causes permanent loss of cerebral functions and the cause of the coma have been shown, (2) intoxication, serious hypotension, metabolic conditions and hypothermia should be excluded and (3) absence of cerebral functions should be evaluated by two experienced physicians. After these prerequisites were met, the patient should be in the supine position, haemodynamically stable (mean arterial pressure 70 mm Hg or blood pressure >90/50 mmHg and PaCO2 35–45 mmHg), heart rate >60 beats min−1 and peripheral oxygen saturation >95% during the TCD examination (1, 3, 5, 12).

TCD application technique

In clinical practice, the most commonly used probe in TCD ultrasound examinations are low-frequency (2.0–3.5 MHz) sector probes (13). High-frequency Doppler probes are not useful in the examination of extracranial vascular structures, because high-frequency sound waves cannot penetrate the skull sufficiently (Figure 1) (14).

Figure 1.

Low-frequency colour TCD ultrasound probe

TCD ultrasound examination should be performed from acoustic windows where sound waves can easily pass through the skull. These acoustic windows are the thinnest parts of the skull bone. Acoustic windows used in the TCD application are transorbital, transtemporal and suboccipital windows (14). Even though each acoustic window has advantages for different arteries and indications, detailed TCD examination should include the evaluation of all acoustic windows, and the blood flow velocities of the arteries forming the Willis polygon should be examined (13). Some criteria are used to define the basal arteries of the brain that constitute the Willis polygon in the TCD: (1) direction of Doppler probe and depth of insonation, (2) blood flow approaching or moving away from the Doppler probe and (3) evaluation of the response of blood flow to carotid compression in cases where it is not possible to distinguish between the anterior and posterior blood circulation (14).

Transorbital acoustic window

After the energy is reduced to 10%, the probe is placed in the upper eyelid with the patient’s eye closed, and the inferior and median examination is performed through the eyeball. Through the transorbital acoustic window, the ophthalmic artery and the internal carotid siphon can be examined. The ophthalmic artery is observed at a depth of 3–5 cm, the siphon of the internal carotid artery is observed at a depth of 6–7 cm and a flow approaching the Doppler probe is seen (1, 5, 14, 15).

Transtemporal acoustic window

The examination is made above the arcus zygomaticus through the squamous part of the temporal bone between the external auditory canal and the orbital area. It is divided into three parts as the anterior, middle and posterior. However, in clinical practice, usually only one window can be used. After the Doppler probe is placed in the transtemporal window, the anatomical points used to determine the vascular structures forming the Willis polygon are the sphenoid bone, the petrous part of the temporal bone and the cerebral peduncles. In the transtemporal window, the middle cerebral artery blood flow is at a depth of 3–7 cm approaching towards the probe, the anterior cerebral artery blood flow is at a depth of 6–8 cm towards the probe and the blood flow of the posterior cerebral artery is at a depth of 6–7.5 cm approaching towards the probe. The middle cerebral artery is the most frequently evaluated artery in clinical practice by TCD ultrasonography and can be easily visualised on the transtemporal acoustic window immediately above the zygomatic arch (1, 4, 14, 15).

Suboccipital acoustic window

The patient should be in the sitting position, the head is slightly flexed and the vertebral artery and the basilar artery flow are observed at a depth of 6–10 cm as the flow away from the probe in the medial of the mastoid protrusion (1, 14, 15).

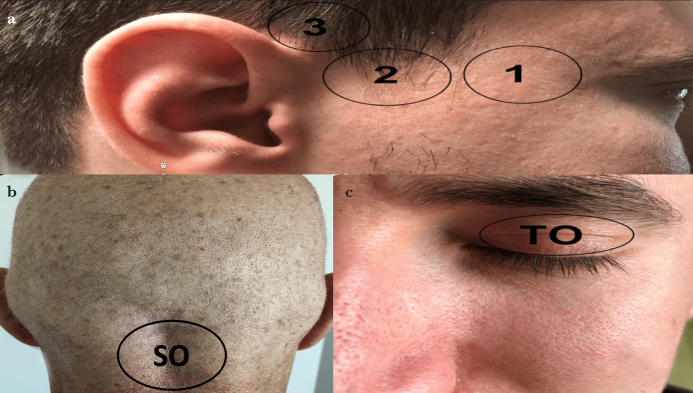

To determine the cerebral circulatory arrest by TCD, both the anterior system from the bilateral transtemporal acoustic windows and the posterior system from the suboccipital acoustic window should be evaluated. If evaluation from the bilateral transtemporal windows and suboccipital window cannot be performed, the evaluation is considered to be suboptimal (Figure 2).

Figure 2. a–c.

Acoustic windows used in TCD ultrasound examination. (a) The transtemporal acoustic window is examined just above the arcus zygomaticus between the external auditory canal and the orbital area. It is divided into three parts: (1) anterior, (2) medial and (3) posterior. (b) The suboccipital window examination is made from the immediate medial of the mastoid bone. (c) In the transorbital window, while the eyes of the patient are closed, the ultrasound probe is placed on the patient’s upper eyelid

SO: suboccipital; TO: transorbital

Detection of brain death through the transorbital acoustic window is not routinely recommended. Current signals of ophthalmic artery and extracranial internal carotid artery can cause false positive results (12).

TCD ultrasonography for the diagnosis of cerebral circulatory arrest

Cerebral circulatory arrest results from the cessation of the cerebral blood flow due to the increased intracranial pressure that blocks the cerebral perfusion. The first use of TCD for the diagnosis of cerebral circulatory arrest was in 1974, and TCD has been shown to be a useful method in many studies in the ensuing years (1, 3, 10, 16, 17). During the development of cerebral circulatory arrest, there are four stages in the evaluation of cerebral blood flow with TCD, and each has characteristic flow patterns (1, 3).

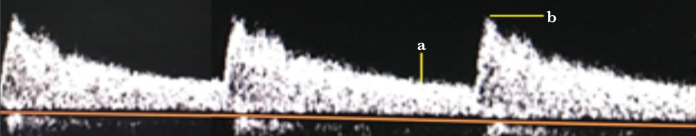

In the case of normal intracranial pressure (ICP), a single-phase flow is observed in systole and diastole towards the brain in the TCD spectra (Figure 3). When ICP starts to increase due to any reason, there is a decrease in end-diastolic blood flow rate (EDV) in the TCD. EDV becomes zero when ICP comes up to diastolic blood pressure, and when the ICP is above diastolic blood pressure, the brain receives blood only in systole. In this case, systolic flow seen in the TCD spectra is called as ‘systolic peak’. Since the cerebral perfusion pressure is still higher than the ICP, there is still a clear forward flow (Figure 4).

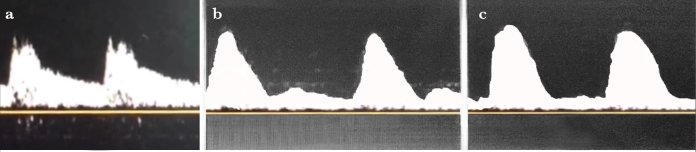

When ICP continues to increase progressively, systolic peak duration is shortened in the TCD spectra; thereafter, diastolic back flow is observed. The spectra of systolic forward and diastolic backward flows in TCD ultrasonography is called as ‘oscillating flow’. In the oscillating flow pattern, when the currents are equalised above and below the zero line, the forward net current is zero, the ICP has exceeded the cerebral perfusion pressure and the cerebral circulation has stopped (Figure 5).

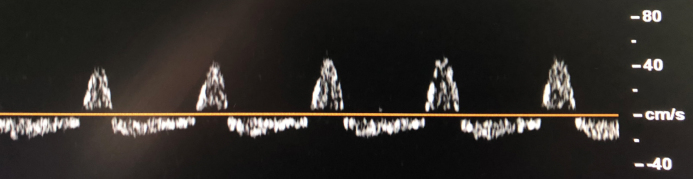

As the ICP continues to increase and approaches the systolic blood pressure, the diastolic reverse current disappears, and isolated ‘systolic spikes’ are monitored in the TCD (Figure 6).

In the case of very high ICP, the amplitudes of the systolic spikes are gradually decreasing, and in the case of complete cessation of blood flow in the intracranial basal arteries, the signal cannot be received in the TCD. To consider the failure to receive a signal in the TCD as a cessation of cerebral circulation, it is necessary that TCD should be performed again by the same clinician at the same clinical conditions after an interval of at least 30 min (Figure 7).

Figure 3. a, b.

Normal TCD spectra with systolic peaks (a) and end-diastolic flow (b) in TCD ultrasonography. In the case of normal cerebral perfusion with normal ICP, TCD shows a single-phase current in systole and diastole

Figure 4. a–c.

TCD ultrasonography spectra. (a) In cases where ICP is normal, there is a single-phase flow in systole and diastole in the TCD. (b) When the ICP begins to increase, the flow rate at the end of the diastole begins to decrease. (c) When ICP is equal to the diastolic blood pressure, systolic peaks are monitored in the TCD spectra

Figure 5.

Flow showing oscillation in TCD ultrasonography. Oscillating current forward in the systole and backward in the diastole in the TCD

Figure 6.

Systolic spikes in TCD ultrasonography. When ICP approaches systolic blood pressure, diastolic reverse flow disappears, and systolic spikes are observed in the TCD

Figure 7.

No signal is obtained in TCD ultrasonography when blood flow is stopped completely in intracranial arteries

The specific spectra seen in the TCD in cerebral circulatory arrest are oscillating flow, systolic spike and absence of signal in the TCD. When oscillatory flow waves are monitored in the TCD spectra, the systolic forward flow should be equal to the diastolic backward flow, and the net flow must be zero to be able to conclude that the cerebral circulation has stopped. Systolic spikes are TCD spectra <200 ms and slower than 50 cm s−1. In the TCD ultrasonography, it is necessary to exclude the problems of ultrasonographic conduction to mention about flow signal loss (1, 3, 4, 14).

TCD ultrasonography in the diagnosis of brain death

Although cerebral angiography evaluating cerebral blood flow in the diagnosis of brain death is considered to be the gold standard method, owing to its limitations, such as the need of getting the patient out of the intensive care unit, the use of contrast agents and the lack of reproducibility, TCD ultrasonography is the frequently preferred method. The most common cause of this condition is that the TCD is non-invasive, does not require radiopaque agent and is a reproducible method. With TCD ultrasonography, cerebral blood flow can be easily evaluated at the bedside particularly in critical patients and does not pose any risk to the patient (1, 3, 12, 16, 18).

In many studies, it has been shown that TCD is a useful and valid method in the diagnosis of cerebral circulation arrest and brain death and can be used to determine the appropriate time for cerebral angiography in determining brain death (1, 18–22).

In the TCD ultrasound evaluation report of the AAN published in 2004, it was stated that the sensitivity of TCD in the diagnosis of cerebral circulatory arrest and brain death was 91%–100%, and the specificity was 97%–100%. In addition, it is suggested that TCD may be useful in evaluating cerebral circulatory arrest associated with brain death with an evidence of level IIA (16).

Poularas et al. (20) compared cerebral angiography with TCD in the determination of brain death and determined the TCD’s specificity in the diagnosis of brain death to be 100%, the sensitivity in the first 3 h of the diagnosis to be 75% and in repeated measurements to be 100%. They also found the correlation of TCD and cerebral angiography to the diagnosis of brain death to be 100%.

The first meta-analysis that evaluated the position of TCD ultrasonography in verifying brain death was made by Monteiro et al. (23) in 2006. In this meta-analysis, 10 studies and 684 cases between 1980 and 2004 were evaluated. When high-quality studies were evaluated, the sensitivity of TCD was found to be 95% and the specificity was found to be 99%, and TCD correctly showed fatal brain injury in all cases. It was also stated that TCD could be used to determine the appropriate time for cerebral angiography in the diagnosis of brain death.

Orban et al. (24) evaluated the effect of TCD on the time interval between the clinical diagnosis of brain death and its conformation with angiography and showed that TCD significantly reduces the time between the clinical diagnosis of brain death and the validation of brain death by angiography; thus, the TCD can be used to determine the appropriate time for cerebral angiography.

In 2016, Chang et al. (18) examined 1671 cases in 22 studies between 1987 and 2014 in the meta-analysis that evaluated the efficacy of TCD ultrasonography in the diagnosis of brain death. In this meta-analysis, TCD was found to have a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 98% in the diagnosis of brain death as a confirmatory test, and TCD has been shown to be a highly reliable confirmatory test for the diagnosis of brain death.

Limitations of TCD ultrasonography

The two most important limitations of TCD ultrasonography are it is an operator-dependent, experience-requiring application and has acoustic window insufficiency due to the thickness and porosity of the skull bone in 10%–20% of cases. It should also be kept in mind that the Willis polygon has a variation of 50%.

Especially in the acute phase of subarachnoid haemorrhage or in sudden increases in ICP caused by recurrent bleeding, waveforms compatible with brain death are observed temporarily in the TCD. In such cases, it is recommended to perform a complete TCD examination including the anterior and posterior systems and to repeat the examination after 30 min. In patients who had decompressive surgery, blood flow can be observed in cerebral arteries even if brain death is diagnosed clinically. A similar condition is observed in anoxic encephalopathy after cardiac arrest. In these cases, TCD may fail to diagnose brain death and may lead to delay in the diagnosis of brain death. For this reason, cerebral angiography is recommended instead of TCD for the detection of brain death especially in patients who had decompressive surgery with cerebral blood flow but is not functional (Table 2) (3, 5, 12, 14, 17).

Table 2.

Advantages and disadvantages of TCD ultrasonography in the detection of brain death.

| Advantages |

| Applicable at bedside, portable method |

| Flow velocities of intracranial arteries can be evaluated as non-invasive |

| A technique that can be easily repeated and continuously make measurement |

| It does not require contrast agents and is a cheaper method than other methods |

| It is not affected by drugs that suppress the central nervous system |

|

|

| Disadvantages |

| An application that requires experience |

| Acoustic window inadequacy is present in 10%–20% of cases |

| False negative result in anoxic patients and those who had decompressive surgery |

| False positive result |

| Vascular structures forming the Willis polygon show variation in 50% of cases |

Conclusion

TCD ultrasonography, which is one of the ancillary tests needed in cases where neurological examination cannot be performed adequately in the clinical diagnosis of brain death and evaluates cerebral blood flow, is distinguished by being a bedside applicable, non-invasive, reproducible method. Moreover, even if there are some limitations, the appropriate time for cerebral angiography, which is the gold standard method for the diagnosis of brain death, can be easily determined with TCD, and the use of resources in vain is prevented. It is inevitable that intensive care specialists will gradually increase the use of TCD ultrasonography in the diagnosis of brain death in the near future due to its advantages.

Footnotes

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept - U.S.K., M.H., B.B.; Design - M.H., B.B.; Supervision - İ.C., B.B.; Resources - B.B., U.S.K.; Materials - M.H., U.S.K.; Data Collection and/or Processing - U.S.K., M.H.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - İ.C., B.B., M.H.; Literature Search - U.S.K., M.H., B.B.; Writing Manuscript - U.S.K., M.H.; Critical Review - İ.C., B.B.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

References

- 1.Volz KR. Intcranial Cerebral Evaluation. In: Rumack CM, Levine D, editors. Diagnostic Ultrasound. Philadelphia, USA: Elsevier; 2018. pp. 983–1005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mollaret P, Goulon M. The depassed coma (preliminary memoir) Rev Neurol. 1959;101:3–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Escudero D, Otero J, Quindos B, Vina L. Transcranial Doppler ultrasound in the diagnosis of brain death. Is it useful or does it delay the diagnosis? Med Intensiva. 2015;39:244–50. doi: 10.1016/j.medin.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Çil O, Görkey Ş. Beyin ölümü kriterlerinin tarihsel gelişimi ve kadavradan organ nakline etkisi. Marmara Med J. 2014;27:69–74. doi: 10.5472/MMJ.2013.02947.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ünal A, Dora B. Beyin ölümü tanısında destekleyici bir test olarak transkranial doppler ultrasonografisi. Türk Beyin Damar Hastalıkları Dergisi. 2012;18:49–58. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Organ ve doku alınması, saklanması, aşılanması ve nakli hakkında kanun. Kanun Numarası 2238 Resmi Gazete 3.6: 1979-16655 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erdoğan A. Yoğun bakım ünitelerinde beyin ölümünün teşhisi. SDÜ Tıp Fak Derg. 2014;21:158–62. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kramer AH. Ancillary testing in brain death. Semin Neurol. 2015;35:125–38. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1547541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robba C, Cardim D, Sekhon M, Budohoski K, Czosnyka M. Transcranial Doppler: a stethoscope for the brain-neurocritical care use. J Neuro Res. 2018;96:720–30. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoneda S, Nishimoto A, Nukada T, Kuriyama Y, Katsurada K. To-and-fro movement and external escape of carotid arterial blood in brain death cases. A Doppler ultrasonic study. Stroke. 1974;5:707–13. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.5.6.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aaslid R, Markwalder TM, Nornes H. Noninvasive transcranial Doppler ultrasound recording of flow velocity in basal cerebral arteries. J Neurosurg. 1982;57:769–74. doi: 10.3171/jns.1982.57.6.0769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ducrocq X, Hassler W, Moritake K, Newell DW, von Reutern GM, Shiogai T, et al. Consensus opinion on diagnosis of cerebral circulatory arrest using Doppler-sonography: Task Force Group on cerebral death of the Neurosonology Research Group of the World Federation of Neurology. J Neurol Sci. 1998;159:145–50. doi: 10.1016/S0022-510X(98)00158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bathala L, Mehndiratta MM, Sharma VK. Transcranial doppler: Technique and common findings (Part 1) Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2013;16:174–9. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.112460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Purkayastha S, Sorond F. Transcranial Doppler ultrasound: technique and application. Semin Neurol. 2012;32:411–20. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1331812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Andrea A, Conte M, Cavallaro M, Scarafile R, Riegler L, Cocchia R, et al. Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography: From methodology to major clinical applications. World J Cardiol. 2016;8:383–400. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v8.i7.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sloan MA, Alexandrov AV, Tegeler CH, Spencer MP, Caplan LR, Feldmann E, et al. Assessment: transcranial Doppler ultrasonography: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2004;62:1468–81. doi: 10.1212/WNL.62.9.1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wijdicks EF, Varelas PN, Gronseth GS, Greer DM American Academy of Neurology. Evidence based guideline update: determining brain death in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2010;74:1911–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e242a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang JJ, Tsivgoulis G, Katsanos AH, Malkoff MD, Alexandrov AV. Diagnostic Accuracy of Transcranial Doppler for Brain Death Confirmation: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2016;37:408–14. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Freitas GR, André C. Sensitivity of transcranial Doppler for confirming brain death: a prospective study of 270 cases. Acta Neurol Scand. 2006;113:426–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poularas J, Karakitsos D, Kouraklis G, Kostakis A, De Groot E, Kalogeromitros A, et al. Comparison Between Transcranial Color Doppler Ultrasonography and Angiography in the Confirmation of Brain Death. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:1213–7. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.02.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lovrencic-Huzjan A, Vukovic V, Gopcevic A, Vucic M, Kriksic V, Demarin V. Transcranial Doppler in brain death confirmation in clinical practice. Ultraschall Med. 2011;32:62–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1245237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, Liu S, Xun F, Liu Z, Huang X. Use of Transcranial Doppler Ultrasound for Diagnosis of Brain Death in Patients with Severe Cerebral Injury. Med Sci Monit. 2016;22:1910–5. doi: 10.12659/MSM.899036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monteiro LM, Bollen CW, van Huffelen AC, Ackerstaff RG, Jansen NJ, van Vught AJ. Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography to confirm brain death: a meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:1937–44. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0353-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orban JC, El-Mahjoub A, Rami L, Jambou P, Ichai C. Transcranial Doppler shortens the time between clinical braindeath and angiographic confirmation: a randomized trial. Transplantation. 2012;94:585–8. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182612947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]