Abstract

Objective

The incidence rate of Parkinson’s disease (PD) is growing rapidly owing to the ageing population. We investigated the mortality rates and causes of death in South Korean patients with PD.

Design

We investigated a national cohort using the nationwide insurance database.

Setting

Korean Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service—National Sample Cohort database.

Participants

We included 3510 participants ≥60 years of age who were diagnosed with PD between 2002 and 2013, as well as 14 040 matched controls.

Interventions

None

Primary and secondary outcome measures

A stratified Cox proportional hazards model was used to evaluate patients with PD who were matched 1:4 with non-PD control subjects adjusted for age, sex, income and region of residence. The causes of death were grouped into 12 classifications.

Results

The adjusted HR for mortality in the PD group was 2.09 (95% CI 1.94 to 2.24, p<0.001). Subgroup analysis according to age (<70 years, 70–79 years, and ≥80 years) and sex revealed that patients with PD showed higher adjusted HRs for mortality across all subgroups. Mortalities caused by metabolic, mental, neurologic, circulatory, respiratory, and genitourinary diseases, as well as trauma, were more common in the PD group than in the control group, with the highest OR observed in patients with neurologic disease.

Conclusions

We demonstrated that PD in South Korean patients ≥60 years of age was associated with increased mortality in both sexes regardless of age.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, mortality, Korean

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our study data set encompassed 1 125 691 subjects registered over a 12-year period in a national insurance database.

The study encompassed all registered patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) who visited outpatient clinics, were hospitalised or both at least twice.

The patients were not restricted to only those who were hospitalised.

The patients with PD were matched 1:4 with control subjects based on age, group, sex, income group, regions of residence and medical histories.

We were unable to determine the severity of PD, and some confounding factors (eg, smoking status, alcohol consumption and obesity) were not adjusted for.

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder, and is characterised by the four cardinal motor signs: tremor at rest, bradykinesia, rigidity and postural instability, as well as other non-motor clinical manifestations.1 2 Despite the remarkable symptom-relieving benefits provided by levodopa over the past 30 years, recent studies have demonstrated that the mortality rates among PD patients remain higher than in individuals without PD.3 4 PD is one of the fastest growing diseases in terms of prevalence, disability and mortality; the rapidly ageing population has contributed to an increase in crude PD prevalence rates.5 As such, a better understanding of the rates and causes of mortality in patients with PD is important to better estimate the social burden and medical care costs.6

Even though PD is associated with increased mortality in general, previous studies show inconsistent data, with mortality rates ranging from 0.80 to 3.50.2 Some studies performed in the post-levodopa era even reported ‘super-normal’ survival rather than increased mortality among PD patients.2 Furthermore, the causes of death in patients with PD remain unclear.7 The heterogeneity observed in studies of mortality as related to PD could be caused by the variable methodology and patient selection criteria. Different studies tend to be hospital/pharmaceutical trial/community-based, and thus yield results that are not very representative of the general population.6

According to the Global Burden of Disease, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study of 2016, the death rate, prevalence and disability-adjusted life-years of patients with PD varied depending on ethnicity and/or geography.5 Among high-income Asia Pacific countries, South Korea showed the highest percentage change in age-standardised mortality rates between 1990 and 2016 (24.6%) compared with Brunei (17.9%), Japan (10.2%) and Singapore (11.3%), even though the percentage change in the age-standardised rates of prevalence during the same time period (21.0%) was similar to that of Japan (21.3%).5 Thus, analyses focused on a particular ethnic/geographic group is important to estimate the social burden of PD and the patient management plan in each country. However, a large cohort-based investigation of PD-related mortality rates and causes of death in South Korea has never been performed.

To better understand the natural courses and prognoses of patients with PD, and to provide valuable information on planning the distribution of health resources, we investigated the mortality rates and causes of death in patients with PD using a representative PD population in South Korea. We performed a large-scale longitudinal follow-up study, with a maximum follow-up duration of 12 years, using national cohort data.

Materials and methods

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved.

Study population and data collection

The requirement for written informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board.

This national cohort study relied on data from the Korean Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA) national sample cohort. The Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) selects samples directly from the entire population database to prevent non-sampling errors. Approximately 2% of the samples (1 million) were selected from the entire Korean population (50 million). These selected data were classified into 1476 levels (age (18 categories), sex (2 categories) and income level (41 categories)) using randomised stratified systematic sampling methods via proportional allocation to represent the entire population. After data selection, the appropriateness of the sample was verified by a statistician who compared the data from the entire Korean population to the sample data. The details of the methods used to perform these procedures are provided by the NHIS Service.8 The cohort database included (i) personal information, (ii) health insurance claim codes (procedures and prescriptions), (iii) diagnostic codes using the International Classification of Disease, 10th edition (ICD-10), (iv) death records from the Korean National Statistical Office (using the Korean Standard Classification of Disease), (v) socioeconomic data (residence and income) and (vi) medical examination data for each participant over a period ranging from 2002 to 2013.

Because all Korean citizens are recognised by a 13-digit resident registration number from birth to death, exact population statistics can be determined using this database. It is mandatory for all Koreans to enrol in the NHIS. All Korean hospitals and clinics use the 13-digit resident registration number to record individual patients in the medical insurance system. Therefore, the risk of overlapping medical records is minimal, even if a patient relocates to another geographical region. Moreover, all medical treatments in Korea can be tracked without exception using the HIRA system. In Korea, a notice of death must legally be delivered to an administrative entity before a funeral can be held. Causes and dates of death are recorded by medical doctors on death certificates.

Participant selection

From among 1 125 691 individuals with 114 369 638 medical claim codes, we included participants who visited a clinic or hospital for PD-related reasons between 2002 and 2013 (n=4169). PD was categorised using ICD-10 codes (PD: G20). For accurate diagnoses, we only selected participants who visited outpatient clinics, were hospitalised or both at least twice because of PD. The control participants were extracted from 1 121 522 participants who had no diagnoses of PD between 2002 and 2013.

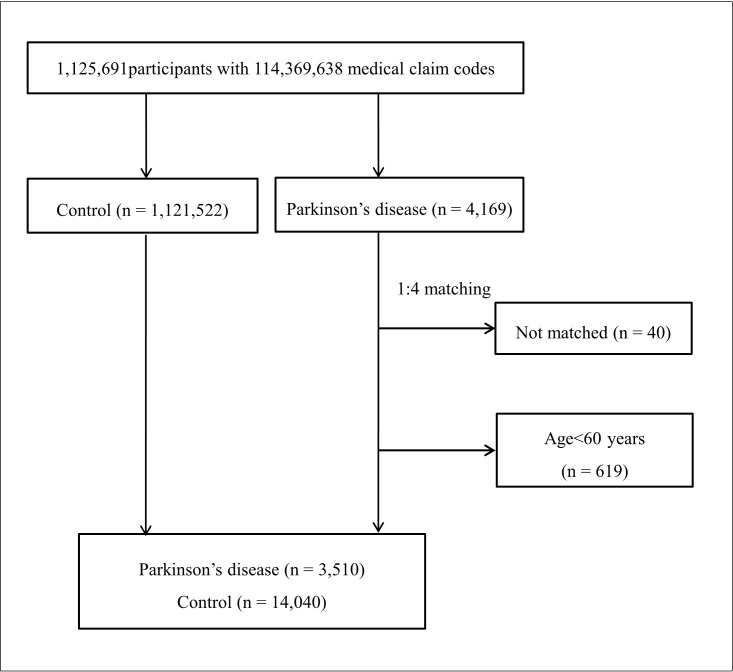

Participants with PD were matched 1:4 with the control group. The matches were adjusted for age group, sex, income, region of residence and medical histories of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidaemia. We set the index date as that of the first visit to a clinic or a hospital for PD during the study period in the PD group; participants from the control group were also followed from the same index date as their matched counterparts with PD. To prevent selection bias, participants in the control group were sorted using a random number, and were then selected in descending order. It was assumed that the matched control participants were involved at the same time of each matched PD participant; therefore, participants in the control group who died before the time of involvement of the matched PD participant were excluded. Forty PD participants for whom we could not identify a sufficient number of matching participants were also excluded, as were 619 participants who were diagnosed with PD while under the age of 60 years since the prevalence of PD is relatively low in younger individuals.9 Ultimately 3510 PD participants matched 1:4 with 14 040 control participants were included (figure 1).

Figure 1.

A schematic illustration of the participant selection process that was used in this study. Of the 1 125 691 total participants, 4169 with Parkinson’s disease (PD) were selected. Participants with PD were matched 1:4 with a control group comprising individuals not diagnosed with PD. Ultimately, 3510 participants with PD and 14 040 control participants were included.

Variables

Age groups were classified by 5-year intervals into six age groups: 60–64, 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84 and 85+years old. The income groups were initially divided into 41 classes (one health aid class, 20 self-employment health insurance classes and 20 employment health insurance classes). These groups were re-categorised into 11 classes (class 1 (lowest income) to class 11 (highest income)). Regions of residence were divided into 16 areas according to the administrative district. These regions were regrouped into urban (Seoul, Busan, Daegu, Incheon, Gwangju, Daejeon, and Ulsan) and rural (Gyeonggi, Gangwon, Chungcheongbuk, Chungcheongnam, Jeollabuk, Jeollanam, Gyeongsangbuk, Gyeongsangnam, and Jeju) areas.

The causes of death were classified according to the Korean standard classification of diseases, developed by the WHO based on the ICD, into 12 classifications: (i) infection (certain infections and parasitic diseases, A00–B99); (ii) neoplasm (neoplasms, C00–D48); (iii) metabolic disease (endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases, E00–E90); (iv) mental disease (mental and behavioural disorders, F00–F99); (v) neurologic disease (diseases of the nervous system, G00–G99); (vi) circulatory disease (diseases of the circulatory system, I00–I99); (vii) respiratory disease (diseases of the respiratory system, J00–J99); (viii) digestive disease (diseases of the digestive system, K00–K93); (ix) muscular disease (diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue, M00–M99); (x) genitourinary disease (diseases of the genitourinary system, N00–N99); (xi) abnormal finding (symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings ‘not elsewhere classified’, R00–R99); and (xii) trauma (injury, poisoning, and certain other consequences of external causes, S00–T98). We also added one more category: (xiii) others (diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs and certain disorders involving the immune mechanism, D50–D89; diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, L00–L99). The Charlson comorbidity index was used for 17 comorbidities as a continuous variable (0 (no comorbidity) through 29 (multiple comorbidities))10 ].

Statistical analyses

The χ2 or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the general characteristics of participants in the PD and control groups, as well as to compare their mortality rates according to the cause of death. The false discovery rate was used to adjust for incorrect rejections of the null hypothesis.

To determine HRs for mortality as a function of PD, a stratified Cox proportional hazards model, both crude (simple) and adjusted for the Charlson comorbidity index, was used. Age, sex, income and region of residence were stratified. Two-tailed p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS software V.21.0 (IBM).

Results

The mean follow-up duration was 49.6 months (SD=37.3 months) in the PD group and 57.3 (SD=40.6) months in the matched control group.

Age, sex, income level and region of residence were matched between the PD and control groups (table 1). The mortality rate was significantly higher in the PD group than that in the control group (34.6% [1,214/3,510] and 19.0% [2,661/14,040], respectively, p<0.001).

Table 1.

General characteristics of the participants

| Characteristics | Total participants | ||

| Parkinson’s disease (n, %) | Control (n, %) | P-value | |

| Age (years old) | 1.000 | ||

| 60–64 | 388 (11.1) | 1552 (11.1) | |

| 65–69 | 660 (18.8) | 2640 (18.8) | |

| 70–74 | 903 (25.7) | 3612 (25.7) | |

| 75–79 | 835 (23.8) | 3340 (23.8) | |

| 80–84 | 498 (14.2) | 1992 (14.2) | |

| 85+ | 226 (6.4) | 904 (6.4) | |

| Sex | 1.000 | ||

| Male | 1336 (38.1) | 5344 (38.1) | |

| Female | 2174 (61.9) | 8696 (61.9) | |

| Income | 1.000 | ||

| 1 (lowest) | 325 (9.3) | 1300 (9.3) | |

| 2 | 283 (8.1) | 1132 (8.1) | |

| 3 | 145 (4.1) | 580 (4.1) | |

| 4 | 154 (4.4) | 616 (4.4) | |

| 5 | 179 (5.1) | 716 (5.1) | |

| 6 | 190 (5.4) | 760 (5.4) | |

| 7 | 251 (7.2) | 1004 (7.2) | |

| 8 | 256 (7.3) | 1024 (7.3) | |

| 9 | 383 (10.9) | 1532 (10.9) | |

| 10 | 584 (16.6) | 2336 (16.6) | |

| 11 (highest) | 760 (21.7) | 3040 (21.7) | |

| Region of residence | 1.000 | ||

| Urban | 1467 (41.8) | 5868 (41.8) | |

| Rural | 2043 (58.2) | 8172 (58.2) | |

| *CCI score | <0.001† | ||

| 0 | 325 (9.3) | 3049 (21.7) | |

| 1 | 132 (3.8) | 659 (4.7) | |

| 2 | 240 (6.8) | 1173 (8.4) | |

| ≥3 | 2813 (80.1) | 9159 (65.2) | |

| Death | 1214 (34.6) | 2661 (19.0) | <0.001† |

*CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index (calculated without including pulmonary disease).

†χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Significance at p<0.05.

The crude and adjusted HRs for mortality in the PD group were 2.29 (95% CI 2.13 to 2.45, p<0.001) and 2.09 (95% CI 1.94 to 2.24, p<0.001), respectively (table 2). When categorising patients according to age (<70 years, 70–79 years and ≥80 years) and sex, PD patients in all the subgroups showed higher crude and adjusted HRs for mortality than did the control patients.

Table 2.

Cox proportional hazards analyses of mortality due to Parkinson’s disease

| Characteristics | HR (95% CI) | |||

| Crude* | P-value | Adjusted*† | P-value | |

| Total participants (n=17 550) | ||||

| Parkinson’s disease | 2.29 (2.13 to 2.45) | <0.001‡ | 2.09 (1.94 to 2.24) | <0.001‡ |

| Control | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Age <70 years old, men (n=2115) | ||||

| Parkinson’s disease | 3.04 (2.45 to 3.77) | <0.001‡ | 2.77 (2.23 to 3.45) | <0.001‡ |

| Control | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Age <70 years old, women (n=3125) | ||||

| Parkinson’s disease | 4.11 (3.24 to 5.21) | <0.001‡ | 3.32 (2.60 to 4.25) | <0.001‡ |

| Control | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Age 70–79 years old, men (n=3280) | ||||

| Parkinson’s disease | 2.27 (1.96 to 2.63) | <0.001‡ | 2.07 (1.78 to 2.41) | <0.001‡ |

| Control | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Age 70–79 years old, women (n=5410) | ||||

| Parkinson’s disease | 2.41 (2.10 to 2.78) | <0.001‡ | 2.22 (1.92 to 2.55) | <0.001‡ |

| Control | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Age≥80 years old, men (n=1285) | ||||

| Parkinson’s disease | 1.53 (1.25 to 1.88) | <0.001‡ | 1.47 (1.20 to 1.82) | <0.001‡ |

| Control | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Age≥80 years old, women (n=2335) | ||||

| Parkinson’s disease | 1.83 (1.55 to 2.17) | <0.001‡ | 1.73 (1.46 to 2.05) | <0.001‡ |

| Control | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

*Stratified model for age, sex, income and region of residence.

†Model adjusted for the Charlson Comorbidity Index.

‡Cox proportional hazard regression model; significance at p<0.05.

Analysis of mortality rates according to the cause of death revealed an OR for overall mortality of 2.26 (95% CI 2.08 to 2.45, p<0.001) in the PD group (table 3); the detailed data are presented in online supplementary table 1. Mortalities caused by metabolic disease, mental diseases, neurologic disease, circulatory disease, respiratory disease, genitourinary disease and trauma were higher in the PD group than in the control group (the false discovery rate-adjusted p-value was <0.05 for each). The OR for mortality was highest for neurologic disease (20.87, 95% CI 16.05 to 27.14, p<0.001); among these neurologic diseases, extrapyramidal and movement disorders were the most common (294/328, 89.6%). Mortalities caused by infection, neoplasm, digestive disease, muscular disease, and other causes were not significantly different between the PD and control groups.

Table 3.

Comparison of mortality rates between the Parkinson’s disease and control patient groups according to the cause of death

| Cause of death | Total participants | |||||

| Parkinson’s disease (total n=3510) | Control (total n=14 040) | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |||

| No of died individual* | † | No of died individual* | † | |||

| All of death | 1214 (34.6) | 100.0 | 2661 (19.0) | 100.0 | 2.26 (2.08 to 2.45) | <0.001‡ |

| Infection | 23 (0.7) | 1.9 | 74 (0.5) | 2.8 | 1.25 (0.78 to 1.99) | 0.375 |

| Neoplasm | 151 (4.3) | 12.4 | 667 (4.8) | 25.1 | 0.90 (0.75 to 1.08) | 0.283 |

| Metabolic disease | 76 (2.2) | 6.2 | 161 (1.1) | 6.1 | 1.91 (1.45 to 2.51) | <0.001‡ |

| Mental diseases | 33 (0.9) | 2.7 | 49 (0.3) | 1.8 | 2.71 (1.74 to 4.22) | <0.001‡ |

| Neurologic disease | 328 (9.3) | 27.0 | 69 (0.5) | 2.6 | 20.87 (16.05 to 27.14) | <0.001‡ |

| Circulatory disease | 277 (7.9) | 22.8 | 705 (5.0) | 26.5 | 1.62 (1.40 to 1.87) | <0.001‡ |

| Respiratory disease | 97 (2.8) | 8.0 | 248 (1.8) | 9.3 | 1.58 (1.25 to 2.01) | <0.001‡ |

| Digestive disease | 30 (0.9) | 2.5 | 88 (0.6) | 3.3 | 1.37 (0.90 to 2.07) | 0.139 |

| Muscular disease | 8 (0.2) | 0.7 | 15 (0.1) | 0.6 | 2.14 (0.91 to 5.04) | 0.076 |

| Genitourinary disease | 25 (0.7) | 2.1 | 50 (0.4) | 1.9 | 2.01 (1.24 to 3.25) | 0.004‡ |

| Trauma | 64 (1.8) | 5.3 | 154 (1.1) | 5.8 | 1.68 (1.25 to 2.25) | 0.001‡ |

| Others | 102 (2.9) | 8.4 | 381 (2.7) | 14.3 | 1.07 (0.86 to 1.34) | 0.533 |

*Calculated as the proportion of the number of deaths among all participants with/without mortality.

†Calculated as the proportion of the number of deaths among participants with mortality.

‡χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Significance at false discovery rate-adjusted p<0.05.

bmjopen-2019-029776supp001.pdf (80.6KB, pdf)

Discussion

Our findings were consistent with those of previous studies, most of which found higher mortality rates in patients with PD with HRs ranging from 1.2 to 2.4.11 12 However, most such studies were performed in Western countries, and data from Asian patients have rarely been reported. A recent study in China found that the standardised mortality rate of patients with PD was 0.62 (95% CI 0.32 to 1.07), implying that the 5-year mortality ratio of patients with PD was not significantly higher than that of the general urban Chinese population.2 However, we cannot compare their results to ours given their different study design; the Chinese study comprised 157 PD patients who were referred to—or diagnosed at—a particular tertiary hospital. To our knowledge, ours is the first study to demonstrate that mortality rates are higher in Korean PD patients using a national cohort, and is also the largest study of its kind to date. The adjusted HR of our study (2.09) was relatively higher than in previous studies considering that most reported HRs fall between 1.2 and 2.4; however, this is of little relevance owing to the major heterogeneity among the study methodologies. Nevertheless, our data still show that the mortality of patients with PD is higher than that in control populations despite recent advances in the treatment of this disease. This indicates that, while current treatment modalities relieve motor symptoms, they do not necessarily improve mortality rates and/or the life expectancies of patients with PD.

Our subgroup analyses showed that patients with PD had higher mortality rates across all age groups and in both sexes. Previous studies have produced similar data, demonstrating that PD is a risk factor for increased mortality regardless of age and sex.11 12 The adjusted HRs were relatively high in patients with PD aged <70 years (2.77 in men and 3.32 in women) but were relatively low in patients with PD aged 70–79 years (2.07 in men and 2.22 in women) and even lower in patients with PD aged >80 years (1.47 in men and 1.73 in women). This phenomenon could be attributed to the death rates themselves increasing in both the control and PD groups as individuals age, which dilutes the impact of PD on the mortality rate of older individuals. A previous literature review by Ishihara et al on the estimated life expectancies of UK and European individuals with PD showed that, as the age of PD onset increased, the standardised mortality ratio dropped gradually from 7.3 in men and 6.7 in women in their twenties to 2.5 in both men and women in their nineties.11 However, this finding may be controversial, as a systematic review and meta-analysis by Macleod et al found that, in 15 of 17 studies, older age either at onset or recruitment was associated with increased mortality.12 This discrepancy could be related to the differing ethnicities of subjects in these studies, as well as the involved countries’ economic statuses, study populations and research methods. The differences in adjusted HRs between men and women were not notable in any of the age groups.

In our study, patients with PD died more frequently of certain diseases and of trauma than their counterparts in the control population. Neurologic diseases (particularly extrapyramidal and movement disorders) were the most common causes of death, implying that PD features themselves were most responsible for death among PD patients in South Korea. Such studies of the outcomes of PD patients are scarce. In a study of mortality among 211 levodopa-treated patients with PD in the UK, Morgan et al showed that the most common cause of death was PD itself (52.6%).3 They interpreted this to indicate that, even though levodopa might improve motor symptoms such as tremor, bradykinesia, and rigidity, it did not slow disease progression.13 As the PD progressed, levodopa-resistant motor symptoms (speech/swallowing impairment, gait and balance problems) and non-motor symptoms (autonomic dysfunction, mood disorders, cognitive impairment, sleep disorders and psychosis) become more prevalent and may contribute to the increased morbidity and mortality.14 Although our study cohort was not necessarily confined to levodopa-treated subjects, it is highly likely that a significant proportion of our patients were being treated with levodopa, as we only selected patients who were treated ≥2 times for PD. Our findings are different from those of other groups that described pneumonia to be the most common cause of death in PD patients.15–18 The most likely explanation for this difference could be the varying methods of patient recruitment: we recruited our subjects based on their PD treatment history regardless of whether they were hospitalised; therefore, the cause of death among our patients, that is neurologic disease that may have included PD itself, may also reflect patients having died of other (perhaps natural) causes while afflicted with PD. However, the causes of death in hospitalised or nursing home-bound PD patients may have had a greater likelihood of being reported as pneumonia because of their orthostatic lability. Furthermore, our indication that PD-group patients did not necessarily die of pneumonia is true insofar as being compared with the control group, and is not a general statement, since we calculated the ORs of the cause of mortality. The significance of other causes of death such as cancer and circulation-impeding ischaemic heart disease remains controversial1 2 15–19; the ORs for these conditions were not significant in our study. Nevertheless, our most important findings include (i) the overall death rate was higher in the PD group than that in the control group, and (ii) metabolic disease, mental diseases, neurologic disease, circulatory disease, respiratory disease, genitourinary disease and trauma are common causes of death in PD patients in addition to PD itself. Our findings ought to be valuable for PD patient caregivers in both hospital and community settings.

An interesting observation was that the proportion of female patients with PD was higher than that of their male counterparts (table 1). No studies have investigated the sex ratio of patients with PD in Korea to date, so we had no records to compare our results to. However, this observation should be interpreted considering the prevalence of PD among each of the sexes in Korea, the prevalence of PD in different age groups and the different life expectancies of men and women in Korea. A recent large-scale study utilising the NHIS—National Sample Cohort database by Lee et al found that the prevalence of PD in Korea was slightly higher among women (47.4 per 100 000 population) than among men (35.4 per 100 000 population) in 2004; these rates gradually increased to 167.3 and 117.7 per 100 000 population, respectively, in 2013.20 Lee et al’s study also found that the prevalence of PD dramatically increased with age; the PD rates in 2004 were 8.1 and 310.9 per 100 000 population among 40–49- and ≥80-year-old subjects, respectively, and had risen to 20.9 and 1226.3 per 100 000 population, respectively, in 2013. The proportion of individuals in our overall cohort who had PD was different from those in the above-mentioned studies because, as stated in Materials and Methods, we used different criteria in selecting PD patients to ensure their actual diagnosis with the disease. Moreover, the life expectancy of men in Korea is shorter than that of women (74.65 vs 81.48 years, respectively, in 2004 and 80.01 vs 86.04 years, respectively, in 2017).21 Shin et al reported that the rates of death among individuals ≥80 years of age were 29.5% for men and 58.0% for women.22

Taken together, we can speculate that the relatively high proportion of women in both the general and PD patient populations in Korea (particularly older age groups, which have a higher prevalence of PD and longer life expectancy) could have resulted in a higher proportion of women with the disease than men. This reasoning is supported by the relatively high number of patients with PD in the older age groups as shown in tables 1 and 2. Our results not only confirm that there were relatively high numbers of patients with PD in the 80–84- and ≥85 year age groups but also show that the male-to-female ratio among patients with PD who are <70 years was higher than that in patients 70–79 years; those ≥80 years showed the lowest male-to-female ratio. Further studies regarding the male/female proportions among patients with PD in different age groups would be helpful to clarify these patterns.

A limitation of our study was that we were unable to determine the severity of PD. In the same context, we did not stratify patients by their hospitalisation histories, disease durations or the presence of mental illness, which may have skewed the mortality data. Furthermore, some confounding factors that can influence mortality, such as smoking status, alcohol consumption and obesity, were not adjusted for.23–25 Another limitation of our study was that the cause of death may not have encompassed all the different types of illnesses and complications that contributed to the death of a patient with PD. We retrieved the causes of death from death certificates, which only list a single condition. This may have resulted in the underestimation of other illnesses that contributed to the death of the patient. Nevertheless, the cause of death reported on a death certificate was the most probable from among the multiple illnesses that may have contributed to the death of the patient; hence, our data ought to be representative in this regard.

Despite these limitations, our data are nevertheless robust because we used a representative, large-scale sample from a cohort database comprising over 1 million subjects over a 12-year follow-up period. Another strength of our study is that our approach minimised the risk of recall bias or missing information, as the data set was based on claims made to the compulsory HIRA nationwide health insurance system. We chose matched controls adjusted for the potential confounding factors of age, sex, income and region of residence. Our subjects’ comorbidity data were consistent with those of previous epidemiologic studies in the Korean population, which was further evidence of our study’s reliability.26 27

Conclusion

We performed the largest study on the risk of mortality in South Korean PD patients with clearly defined inclusion criteria. We found that PD increased the risk of mortality regardless of age and sex. Common causes of death in patients with PD included metabolic, mental, neurologic, circulatory, respiratory and genitourinary diseases as well as trauma; the highest OR observed was for neurologic disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a research grant (NRF-2015-R1D1A1A01060860) from the National Research Foundation of Korea.

Footnotes

SS and MK contributed equally.

Contributors: HGC composed the manuscript, J-SL provided neurologists’ perspectives, YKL reviewed the result and SS and MK designed and supervised the study.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The ethics committee of Hallym University approved the use of these data (approval number 2014-I148).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: The data used for this study are available from the Korea National Health Insurance Sharing Service (https://nhiss.nhis.or.kr) subject to their requirements and fees.

References

- 1. Doi Y, Yokoyama T, Nakamura Y, et al. . How can the National burden of Parkinson's disease comorbidity and mortality be estimated for the Japanese population? J Epidemiol 2011;21:211–6. 10.2188/jea.JE20100149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang G, Li X-J, Hu Y-S, et al. . Mortality from Parkinson’s disease in China: Findings from a five-year follow up study in Shanghai. Can J Neurol Sci 2015;42:242–7. 10.1017/cjn.2015.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Morgan JC, Currie LJ, Harrison MB, et al. . Mortality in levodopa-treated Parkinson's disease. Parkinsons Dis 2014;2014:426976 10.1155/2014/426976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. CLarke CE. Mortality from Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;68:254–5. 10.1136/jnnp.68.2.254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. GBD 2016 Parkinson's Disease Collaborators Global, regional, and national burden of Parkinson's disease, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Neurol 2018;17:939–53. 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30295-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Lau LML, Schipper CMA, Hofman A, et al. . Prognosis of Parkinson disease: risk of dementia and mortality: the Rotterdam study. Arch Neurol 2005;62:1265–9. 10.1001/archneur.62.8.1265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pennington S, Snell K, Lee M, et al. . The cause of death in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2010;16:434–7. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2010.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. The National health insurance sharing service of Korea, 2014. Available: https://nhiss.nhis.or.kr/bd/ab/bdaba022eng.do [Accessed November 1, 2018].

- 9. Driver JA, Logroscino G, Gaziano JM, et al. . Incidence and remaining lifetime risk of Parkinson disease in advanced age. Neurology 2009;72:432–8. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000341769.50075.bb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. . Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge Abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:676–82. 10.1093/aje/kwq433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ishihara LS, Cheesbrough A, Brayne C, et al. . Estimated life expectancy of Parkinson's patients compared with the UK population. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2007;78:1304–9. 10.1136/jnnp.2006.100107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Macleod AD, Taylor KSM, Counsell CE. Mortality in Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2014;29:1615–22. 10.1002/mds.25898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Olanow CW. The scientific basis for the current treatment of Parkinson's disease. Annu Rev Med 2004;55:41–60. 10.1146/annurev.med.55.091902.104422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rascol O, Payoux P, Ory F, et al. . Limitations of current Parkinson's disease therapy. Ann Neurol 2003;53 Suppl 3:S3–S15. 10.1002/ana.10513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hobson P, Meara J. Mortality and quality of death certification in a cohort of patients with Parkinson’s disease and matched controls in North Wales, UK at 18 years: a community-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e018969 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018969 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. D'Amelio M, Ragonese P, Morgante L, et al. . Long-Term survival of Parkinson's disease: a population-based study. J Neurol 2006;253:33–7. 10.1007/s00415-005-0916-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fall P-A, Saleh A, Fredrickson M, et al. . Survival time, mortality, and cause of death in elderly patients with Parkinson's disease. A 9-year follow-up. Mov Disord 2003;18:1312–6. 10.1002/mds.10537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beyer MK, Herlofson K, Arsland D, et al. . Causes of death in a community-based study of Parkinson's disease. Acta Neurol Scand 2001;103:7e11 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2001.00191.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ben-Shlomo Y, Marmot MG. Survival and cause of death in a cohort of patients with parkinsonism: possible clues to aetiology? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiat 1995;58:293–9. 10.1136/jnnp.58.3.293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee JE, Choi J-kyu, Lim HS, et al. . The prevalence and incidence of Parkinson′s disease in South Korea: a 10-year nationwide population–based study. J Korean Neurol Assoc 2017;35:191–8. 10.17340/jkna.2017.4.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Khang Y-H, Bahk J, Lim D, et al. . Trends in inequality in life expectancy at birth between 2004 and 2017 and projections for 2030 in Korea: multiyear cross-sectional differences by income from national health insurance data. BMJ Open 2019;9:e030683 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Korea S, Shin HY, et al. , Vital Statistics Division, . Cause-of-death statistics in 2016 in the Republic of Korea. J Korean Med Assoc 2018;61:573–84. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ma C, Liu Y, Neumann S, et al. . Nicotine from cigarette smoking and diet and Parkinson disease: a review. Transl Neurodegener 2017;6:18 10.1186/s40035-017-0090-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bettiol SS, Rose TC, Hughes CJ, et al. . Alcohol consumption and Parkinson's disease risk: a review of recent findings. J Parkinsons Dis 2015;5:425–42. 10.3233/JPD-150533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen J, Guan Z, Wang L, et al. . Meta-Analysis: overweight, obesity, and Parkinson's disease. Int J Endocrinol 2014;2014:203930 10.1155/2014/203930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim DJ. The epidemiology of diabetes in Korea. Diabetes Metab J 2011;35:303–8. 10.4093/dmj.2011.35.4.303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee H-Y, Park JB. The Korean Society of hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension in 2013: its essentials and key points. Pulse 2015;3:21–8. 10.1159/000381994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-029776supp001.pdf (80.6KB, pdf)