Abstract

Objective

To examine the relationship between sense of coherence (SOC) and physical health–related quality of life in patients with chronic illnesses by focusing on the mediating role of the mental component of quality of life.

Design

Cross-sectional survey design.

Setting

Secondary care; three departments of an Italian university hospital.

Methods

The participants (n=209) in the study were adult (≥18 years) outpatients with a chronic pathology (eg, diabetes, thyroid disorders or cancer) at any phase in the care trajectory (eg, pre-treatment, undergoing treatment, follow-up care). They agreed to participate in the study after providing their informed consent. Data were collected using a structured self-reporting questionnaire. Data analysis was carried out using SPSS, and mediation analysis was performed via PROCESS macro.

Results

The SOC score of the study sample was equivalent to that of the general population (mean difference=−2.50, 95% CI −4.57 to 0.00). Correlation analysis showed that SOC was mainly correlated to the mental component (MCS) (r=0.51, p<0.01) of quality of life and then to the physical component (PCS) (r=0.35, p<0.01). Mediation analysis showed that SOC was directly related to MCS (p<0.001, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.99) but not to PCS (p=0.42, 95% CI −0.27 to 0.12). In turn, MCS was directly related to PCS (p<0.001, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.01). The indirect effect of SOC on PCS through MCS was significant (0.71, p<0.001, bootstrap 95% CI 0.54 to 0.91), thus supporting the mediating role of the mental component of quality of life.

Conclusion

The indirect effect suggests that SOC is a marker of quality of life, especially of the mental component. The findings show that SOC is a psychological process that impacts patients’ mental health status, which in turn affects physical health. Better knowledge of a person’s SOC and how it affects his/her quality of life may help to plan tailoring interventions to strengthen SOC and improve health-related quality of life.

Keywords: Chronic patient, Health, Mediating role, Quality of life, Sense of Coherence

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The sample is not representative of all chronic pathologies and future studies should expand data collection to obtain more data from patients with different diseases and look at the transferability of the results.

The study’s cross-sectional design does not allow us to draw conclusions regarding the causal relationships between variables. Prospective designs are needed to examine the long-term connections between sense of coherence (SOC) and quality of life.

SOC may be a marker of mental health–related quality of life, which in turn influences physical quality of life.

Better knowledge of a person’s sense of coherence and how it affects his/her quality of life may help to better plan tailoring interventions.

The efforts of health professionals in health promotion activities could be addressed to strengthen SOC.

Introduction

Salutogenesis is a concept focusing on factors that promote health and well-being instead of focusing on those that cause disease.1 The salutogenic approach involves the interaction between the individual, community and environment, in which the resources of individuals and communities are committed to strengthening health and well-being.2 The concept relies on using resources (eg, economic, social, healthy lifestyles, self-esteem, experience, knowledge resources, etc) and also on the ability to identify and (re)use resources in a health-promoting way.

According to Antonovsky, life is a chaos in which individuals constantly have to cope with change. People are exposed to different sources of stress (eg, family illness, family changes such as divorce, changes in the workplace such as organisational changes or unemployment, etc) that may lead them away from positive healthy conditions towards negative conditions of illness, and vice versa. This approach goes beyond the traditional dichotomy of health and disease and instead considers them a continuum in people’s lives.3 Some individuals manage to achieve good health despite their exposure to stressors. This depends on whether they are able to deal with, overcome or avoid the tension generated by stressors (eg, stressful events) effectively by identifying and (re)using resources.4 The ability to identify and (re)use resources to effectively cope with stressful events and promote health would positively influence one’s own health condition.1 It can be explained by the sense of coherence concept,5 6 which is an underlying resource enabling effective coping strategies that forms the basis of the salutogenic model.

Sense of coherence concept

Sense of coherence (SOC) is a dispositional orientation that allows individuals to be more resilient to stressors in daily life, stay well and improve their health. It includes three components: comprehensibility, manageability and meaningfulness.6 7 The sense of comprehensibility refers to the degree to which life events make sense and are understandable for people. An individual who understands what is happening is more able to face difficult situations. The sense of manageability is the extent to which people perceive that they have sufficient available (internal and external) resources to satisfy their needs. Having control helps people to live better and healthier. Finally, the sense of meaningfulness represents the source of motivation, namely the extent to which people feel that life has emotional meaning and the problems faced are seen as challenges rather than hindrances. Attributing meaning to events increases people’s motivation to make an effort to face life.

Therefore, SOC is an overall orientation that conveys a feeling of trust because stressors are predictable, that resources to face challenges are available and that the challenges are worth the individual’s effort because they have meaning for him/her.4 8 However, despite the importance of considering the different components of SOC, Antonovsky4 9 strongly highlights the indivisibility of the construct. The literature indicates that SOC is related to an individual’s ability to identify and (re)use resources from his/her internal (eg, cognitive, emotional and behavioural strategies) or external (eg, social support, social fairness, relationships, outdoor life, culture) environment to cope with difficulties and maintain good health.10–13 According to Antonovsky,4 6 individuals with high SOC perceive stressors as challenges, and thus anticipate events and the resources available to modify their perception of life and move from a condition of illness to one of health. High SOC strengthens resilience and promotes an individual state of well-being.1 4

Salutogenic approach and health-related quality of life

The literature suggests that the salutogenic model promotes health, improves resilience and fosters positive physical and mental health conditions.14 15 Langeland et al 16 show that SOC predicted life satisfaction in patients with mental health problems. Eriksson and Lindström,7 in their systematic review, indicate that SOC is associated with quality of life in different patient populations.

Health-related quality of life is a multidimensional concept encompassing the physical, mental and social aspects of an individual’s health and his/her relationship to the environment.17–19

It focuses on the impact of illness and treatment on quality of life and reflects how people respond to the physical and psychological effects of illness, which can influence life satisfaction.20

Health-related quality of life can be measured by two main components: physical (eg, physical functioning, role limitations due to physical problems, bodily pain and general health) and mental (eg, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health). As coping strategies to overcome difficulties and maintain good health involve psychological processes focused on cognitive and behavioural efforts21 that require willingness and motivation, it is likely that SOC is more closely linked to the mental than the physical component of quality of life. A recent study has shown that mental health plays a mediating role in the association between physical disease and self-reported health.22 Moreover, other studies show a strong relationship between SOC and the mental component of health-related quality of life in patients with different chronic illnesses.11 23 Nevertheless, it is not clear how SOC affects the physical component. It is likely that resilience entails emotional effort and is directly related to mental quality of life that, in turn, is related to physical quality of life.

As there is still uncertainty regarding the relationship mechanisms between SOC and health,24 this study aims to examine the relationship between SOC and physical health–related quality of life in patients with chronic illness by focusing on the mediating role of the mental component of quality of life.

Methods

Study design

This is a cross-sectional study to investigate the association between SOC and physical health–related quality of life through the mediating role of mental component.

Setting

Research was carried out in three departments (eg, Endocrinology, Diabetology and Oncology) of a southern Sardinia university hospital in Italy, after being approved by the health director of the hospital.

Patient involvement

Participants were recruited during the check-up consultation and approached in the waiting room. The inclusion criteria used in recruitment were (1) patients had a chronic pathology such as diabetes, a thyroid disorder, cancer and so on at any phase in the care trajectory (eg, pre-treatment, undergoing treatment, follow-up care); (2) patients were adults (≥18 years); and (3) patients agreed to participate in the study after providing informed consent.

Written and oral information on the purpose of the study was provided to each participant. Participation was voluntary and subject to informed consent for all outpatients agreeing to the study. Participants were also informed that they could interrupt their participation at any time without any prejudice.

Data collection

Patient data were collected between May and September 2018 using a structured self-reporting questionnaire. All the patients completed the questionnaire independently, and then returned it directly to the researchers.

Instruments

The questionnaire consisted of two sections. The first regarded patient demographics, including information such as gender, age, education, employment, type of pathology, time of onset of illness, medications and medical history (including surgery and possible complications related to the disease). The physician completed this part of the questionnaire via patient interviews. The second part of the questionnaire was self-administered and concerned validated scales regarding the study variables (eg, SOC and health-related quality of life). The first and second parts of the questionnaire were then matched via a coding scheme to guarantee the patients’ privacy.

To measure SOC, we used the Italian version of Antonovsky’s SOC-13 original scale,6 validated by Sardu et al.25 The scale includes 13 items with a 7-point Likert scale.

To measure health-related quality of life, the Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36) of Apolone and Mosconi26 was used, based on the original version by Ware and Sherbourne.27 The scale includes a total of 36 items that assess eight health domains: physical functioning (PF; 10 items), role physical (RP; 4 items), bodily pain (BP; 2 items), general health (GH; 5 items), vitality (VT; 4 items), social functioning (SF; 2 items), role emotional (RE; 3 items) and mental health (MH; 5 items). Finally, one single item measures the change in patients’ general health status over the past year.

As shown by Schroder et al,28 the eight domains can be combined into two main components: physical component summary (PCS), which includes the PF, RP, BP and GH domains, and mental component summary (MCS), which includes the VT, SF, RE and MH domains. In our study, we used this combined measure to assess health-related quality of life and its association with SOC.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was carried out by using SPSS V.20.0. Missing values (from 5% to 10%) were randomly distributed throughout the sample (Missing Completely at Random test: χ2 (202)=218.2, p>0.05) and were treated using the EM algorithm (Expectation-Maximisation), as suggested by Schafer and Graham.29 The significance of the sample size was calculated using statistical power analysis. Mean values were used to perform analyses. SOC of the study sample was compared with that of the general population to examine if SOC is a stable factor. Descriptive analyses were performed for the study variables and bivariate analysis was conducted using Pearson’s correlation. SOC was identified as the independent variable (X), PCS was the outcome variable (Y) and MCS was the mediator variable (M). Demographic variables such as gender and age were considered as control variables. Levene’s test was computed to examine the homogeneity of variances in the sample subgroups (eg, for both gender and pathology) for the independent variable. To examine the indirect effect of X on Y through M, mediation analysis was performed via PROCESS macro30 using Model 4 (simple mediation). Mediation analysis allows the relationship between independent (SOC) and the dependent (PCS) variables through a mediating variable (MCS) to be examined. A mediator (or intervening variable) transfers the effect of an independent variable to a dependent variable. The mediator produces variation in the predicted variable and itself is caused by the predictor variable.31 In our research, we assume that MCS intervenes in the relationship between SOC and PCS. Simple mediation is a conventional model used to explore mediating effect and allows one mediator to be added to the regression model at a time30 (figure 1). The bootstrapping procedure to measure indirect effect was carried out and CIs (95%) were calculated with 5000 bias-corrected bootstrapped random resamples of the data with replacement.32 Control variables such as age and gender were introduced in the model as covariates.

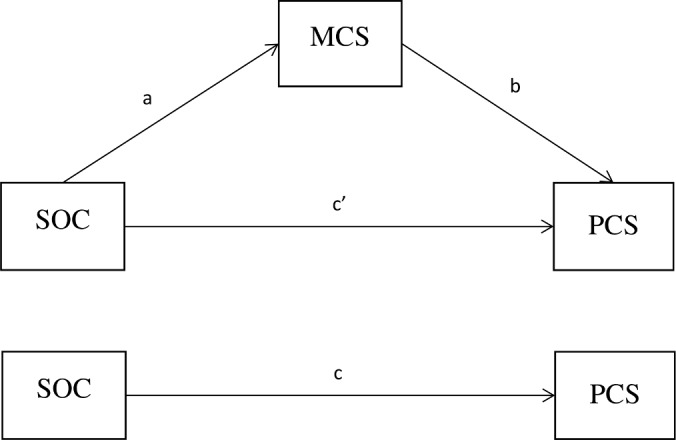

Figure 1.

Conceptual diagram for mediation analysis. Indirect effect of sense of coherence (SOC) on physical component summary (PCS) through mental component summary (MCS)=ab. Direct effect of SOC on PCS=c′. Total effect of SOC on PCS=c.

Results

A minimum total sample size of 209 individuals (general population n=913) was required for a statistical power of 90% at the p<0.05 level of significance. Thus, a total of 209 (71 men and 138 women) outpatients with three different pathologies were recruited. Patients were affected by diabetes (n=71 patients, 37 men and 34 women), thyroid disorders (n=77 patients, 9 men and 68 women) and cancer (n=61 patients, 25 men and 36 women).

Table 1 shows the mean scores and SD for the SOC measure.

Table 1.

Sense of coherence (SOC) scores for the general population and the study sample

| Variable | N | SOC score | SD |

| General population* | 913 | 60.3 | 13.6 |

| Study sample | 209 | 62.8 | 14.5 |

| Men | 71 | 61.7 | 15.2 |

| Women | 138 | 63.4 | 14.1 |

| Patients with diabetes | 71 | 61.3 | 14.6 |

| Patients with a thyroid disorder | 77 | 61.8 | 15.5 |

| Patients with cancer | 61 | 65.9 | 12.8 |

*From the study by Sardu et al. 25

If we compare SOC scores, we can say that the SOC value in the study sample is equivalent to that of the general population25 (mean difference=−2.50, 95% CI −4.57 to 0.00). Regarding the study sample, Levene’s test for equality of variances shows that the SOC scores are equal for both men and women (F=0.63, p=0.43; mean difference=−1.68, 95% CI −2.50 to 5.85), as well as for the different pathology subgroups (F=2.02, p=0.13; mean difference for patients with diabetes and cancer=−4.65, 95% CI −10.72 to 1.42; mean difference for patients with diabetes and a thyroid disorder=−0.50, 95% CI −6.24 to 5.24; mean difference for patients with a thyroid disorder and cancer=−4.15, 95% CI −10.13 to 1.83). As there is no significant difference in the average SOC scores of the sample subgroups, we considered the sample as a whole.

Table 2 shows mean values, SD and correlations for all the variables. The results are in line with the theoretical purpose insofar as they show that SOC is mainly correlated to MCS (r=0.51) and then to PCS (r=0.35). Moreover, the correlation between MCS and PCS was 0.74.

Table 2.

Means, SD and Pearson’s correlations for the study variables

| Variable | M | SD | SOC | PCS | MCS |

| SOC | 62.8 | 14.5 | 1 | ||

| PCS | 62.2 | 26.2 | 0.35** | 1 | |

| MCS | 58.5 | 22.7 | 0.51** | 0.74** | 1 |

n=209. **P<0.01 (two-tailed).

MCS, mental component summary; PCS, physical component summary; SOC, sense of coherence.

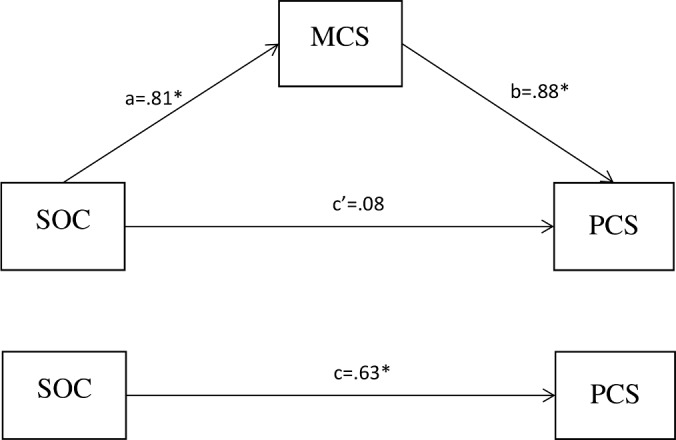

As expected, the results from Model 4 indicate that SOC is directly and positively related to MCS (β=0.81, p<0.001, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.99) but not to PCS (β=−0.08, p=0.42, 95% CI −0.27 to 0.12). In turn, MCS is positively and directly related to PCS (β=0.88, p<0.001, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.01). Among the control variables, gender and age are not significantly related to both MCS (β=3.63, p=0.21, 95% CI −2.09 to 9.35; β=−3.05, p=0.27, 95% CI −8.47 to 2.37) and PCS (β=0.56, p=0.83, 95% CI −4.63 to 5.75; β=0.97, p=0.70, 95% CI −3.94 to 5.88), respectively. The indirect effect of SOC on PCS through MCS is significant (table 3 and figure 2). The model explains 55% of the variance in the outcome variable.

Table 3.

Mediation analysis of MCS on SOC–PCS relationship

| Model | Path coefficient | SE | Bias corrected bootstrap 95% CI | |

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||

| SOC on MCS (path a) | 0.81* | 0.09 | 0.62 | 0.99 |

| MCS on PCS (path b) | 0.88* | 0.06 | 0.76 | 1.01 |

| Total effect of SOC on PCS (path c) | 0.63* | 0.12 | 0.40 | 0.87 |

| Direct effect of SOC on PCS (path c′) | −0.08 | 0.10 | −0.27 | 0.12 |

| Indirect effect of SOC on PCS (path ab) | 0.71* | 0.09 | 0.54 | 0.91 |

n=209. *P<0.001.

MCS, mental component summary; PCS, physical component summary; SOC, sense of coherence.

Figure 2.

Statistical diagram for mediation analysis. Indirect effect of sense of coherence (SOC) on physical component summary (PCS) through mental component summary (MCS) (ab)=0.71, p<0.001. *P<0.001.

Discussion

The aim of the study was to examine the relationship between SOC and quality of life in patients with a chronic illness and analyse the mediating role of the mental component of quality of life. The sample’s descriptive characteristics confirmed that SOC is a stable factor regardless of the person’s health status. In fact, the recruited patients with different pathologies had an average SOC score comparable with that of the general population. Furthermore, the results showed that SOC scores were equal for the different pathologies and there did not appear to be any differences in terms of gender. According to the literature, SOC tends to be lower in women than men, but usually these differences were very slight, probably due to social factors.10 25

The correlation analysis showed that SOC was more strongly correlated to MCS than PCS and the indirect effect analysis highlighted the mediating role of MCS. In other words, SOC is not directly related to PCS but rather indirectly through the mediation of MCS. In line with the previous studies, these findings support the idea that SOC is a psychological process that is related to patients’ mental health status,11 23 which is positively associated with their physical health. This indirect effect is the additional value of this study. However, our findings are in line with SOC being a predictor of quality of life and confirm previous research on the association between SOC and health-related quality of life.33 34

As expected, gender was not significantly related to the model outcomes. This means that whether a person is male or female does not contribute to explaining the relationship to both MCS and PCS. Similarly, age was not related to both MCS and PCS. Although previous research showed that both mental and physical health–related quality of life are lower in elderly people,35 this result supports our findings by showing that age and gender are not confounders in our study.

Implications for public health and communities

The results of this study can help to address the efforts of health professionals in health promotion activities for people with chronic pathologies. Better knowledge of a person’s SOC and how it affects quality of life may help to better plan tailoring interventions. The indirect effect found suggests that SOC is a marker of quality of life, especially of the mental component, which in turn influences the physical component. In this sense, high SOC may strengthen patients’ mental health status on the one hand, but on the other hand, low SOC may result in poor outcomes in terms of quality of life.

Previous studies found that SOC is a stable entity in adulthood.36 37 Although research showed that SOC may increase with age, reaching its highest levels at older ages,13 the study supports that age is not a confounder in our model, as it was not significantly related to both the MCS and PCS components of quality of life. However, recent studies have suggested that SOC could be strengthened in health promotion activities38 39 by using an approach that includes reflection and mindfulness (for additional information regarding the interventions see Kabat-Zinn’s work).40 Sometimes people possess sufficient resources to move to a more healthy state41 but are unable to identify and use them, and therefore perceive their health condition as incomprehensible, unmanageable and unmeaningful. Health professionals can contribute to empowering people to reflect on the available resources and on how to mobilise them to use them successfully.24 They can facilitate people’s reflection on difficult situations by looking uncritically at the present, rather than thinking about possible future problems.24 38 These interventions could contribute to increasing levels of SOC and improving quality of life. However, because of the reciprocal influence between SOC and resources,1 the interventions at individual level should be combined with interventions to strengthen external resources. Recent developments on future directions for the concept of salutogenesis42 suggest that interventions should involve communities in identifying life demands and life opportunity to promote health, making decisions and creating shared visions on desired change processes. Specific interventions regard re-orienting professional leadership towards citizen empowerment to better respond to emerging challenges, giving priority to local strategies to improve community cohesion and enable stakeholders (citizens, professionals and policy-makers) an effective community action, creating supportive environments for health, and develop advocacy competencies to allow citizens and health professionals to influence political decisions.

Limitations

This study has a few limitations that should be addressed in future research. Its first weakness is its small sample size. However, statistical power analysis shows that our sample is representative of the general population. While we are aware that our sample is not representative of all chronic pathologies, one future aim of this study is to continue collecting data to obtain more data on different diseases and look at the transferability of the results.

Second, the data were collected using a quantitative approach. Future studies could supplement this method by using a qualitative approach including interviews or focus groups to better understand how people experience the health–illness continuum in their daily lives.

Another limitation is the cross-sectional design used, which did not allow us to draw conclusions regarding the causal relationships between variables. Future studies should use prospective designs to examine the long-term connections between SOC and quality of life and between possible tailoring interventions and SOC levels.

Finally, further studies would need to examine other possible covariates such as social/family support to analyse if and how it contributes to improving both SOC and quality of life.43

However, despite these limitations, our findings offer a basis on which to develop future research in the area, and suggest that the salutogenic approach may support mental health–related quality of life among chronic patients.

Conclusion

SOC was more strongly correlated to MCS than PCS and indirectly affected PCS through the mediation of MCS. The findings underscore that SOC is a psychological process that impacts patients’ mental health status, which in turn affects physical health. Our study would back the importance of gathering additional evidence on the mediating role of the mental component of quality of life.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MG and PC conceived and designed the study, conducted the data analysis, drafted the manuscript and performed a critical revision of the manuscript. MC drafted the manuscript. AC, GL, VM, MP, FT, GZ and SD collected data and contributed to drafting and editing the manuscript. PO, EM, EC and FB contributed to drafting and editing the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was conducted according to the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the AOUCA Independent Ethics Committee of Southern Sardinia, Italy (Prot. NP/2018/1635).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Antonovsky A. Health, stress and coping. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vaandrager L, Kennedy L. Chapter 17. The application of salutogenesis in communities and neighborhoods : Mittelmark MB, Sagy S, Eriksson M, The handbook of salutogenesis. Cham (CH): Springer, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Antonovsky A. The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promot Int 1996;11:11–18. 10.1093/heapro/11.1.11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Antonovsky A. Unraveling the mystery of health—how people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 5. McCubbin HI, Thompson EA, Thompson AI, et al. The sense of coherence: an historical and future perspective. Israeli J Med Sci 1996;32:170–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Antonovsky A. The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Soc Sci Med 1993;36:725–33. 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90033-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eriksson M, Lindström B. Antonovsky's sense of coherence scale and its relation with quality of life: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007;61:938–44. 10.1136/jech.2006.056028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Eriksson M. Chapter 11. The sense of coherence in the salutogenic model of health : Mittelmark MB, Sagy S, Eriksson M, The handbook of salutogenesis. Cham (CH): Springer, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Antonovsky A. The sense of coherence: development of a research instrument. Newsletter research report. Schwartz Research Center for Behavioral Medicine. 1 Tel Aviv University, 1983: 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lindström B, Eriksson M. Salutogenesis. J Epidemiol Community Health 2005;59:440–2. 10.1136/jech.2005.034777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kristofferzon M-L, Engström M, Nilsson A. Coping mediates the relationship between sense of coherence and mental quality of life in patients with chronic illness: a cross-sectional study. Qual Life Res 2018;27:1855–63. 10.1007/s11136-018-1845-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Greimel E, Kato Y, Müller-Gartner M, et al. Internal and external resources as determinants of health and quality of life. PLoS One 2016;11:e0153232 10.1371/journal.pone.0153232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Langeland E, Vinje HF, Mittelmark MB, et al. Chapter 28. The application of salutogenesis in mental healthcare settings : Mittelmark MB, Sagy S, Eriksson M, et al., The handbook of salutogenesis. Cham (CH): Springer, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lindström B, Eriksson M. Contextualizing salutogenesis and Antonovsky in public health development. Health Promot Int 2006;21:238–44. 10.1093/heapro/dal016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lindström B, Eriksson M. The Hitchhiker’s guide to salutogenesis. Salutogenic pathways to health promotion. 2nd edn Helsinki: Folkhalsan Research Center, Health Promotion Research and the IUHPE Global Working Group on Salutogenesis, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Langeland E, Wahl AK, Kristoffersen K, et al. Sense of coherence predicts change in life satisfaction among home-living residents in the community with mental health problems: a 1-year follow-up study. Qual Life Res 2007;16:939–46. 10.1007/s11136-007-9199-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hays RD, Reeve BB. Measurement and modeling of health-related quality of life : Killewo J, Heggenhougen HK, Quah SR, Epidemiology and demography in public health. San Diego: Academic Press, 2010: 195–205. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Karimi M, Brazier J. Health, health-related quality of life, and quality of life: what is the difference? Pharmacoeconomics 2016;34:645–9. 10.1007/s40273-016-0389-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. WHO The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment. Field trial version for adults. Administration manual. Paper presented at WHO. Geneva, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lin X-J, Lin I-M, Fan S-Y. Methodological issues in measuring health-related quality of life. Tzu Chi Med J 2013;25:8–12. 10.1016/j.tcmj.2012.09.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lorem GF, Schirmer H, Wang CEA, et al. Ageing and mental health: changes in self-reported health due to physical illness and mental health status with consecutive cross-sectional analyses. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013629 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moen VP, Eide GE, Drageset J, et al. Sense of coherence, disability, and health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional study of rehabilitation patients in Norway. Arch Phys Med Rehab. In Press 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Super S, Wagemakers MAE, Picavet HSJ, et al. Strengthening sense of coherence: opportunities for theory building in health promotion. Health Promot Int 2016;31:869–78. 10.1093/heapro/dav071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sardu C, Mereu A, Sotgiu A, et al. Antonovsky's Sense of Coherence Scale: cultural validation of SOC questionnaire and socio-demographic patterns in an Italian population. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health 2012;8:1–6. 10.2174/1745017901208010001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Apolone G, Mosconi P. The Italian SF-36 health survey: translation, validation and norming. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1025–36. 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00094-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schröder A, Oernboel E, Licht RW, et al. Outcome measurement in functional somatic syndromes: SF-36 summary scores and some scales were not valid. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:30–41. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychol Methods 2002;7:147–77. 10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Publications, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Galletta M, Portoghese I, Penna MP, et al. Turnover intention among Italian nurses: the moderating roles of supervisor support and organizational support. Nurs Health Sci 2011;13:184–91. 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00596.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mackinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behav Res 2004;39:99–128. 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moen VP, Eide GE, Drageset J, et al. Sense of coherence, disability, and health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional study of rehabilitation patients in Norway. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2019;100:448–57. 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Helvik A-S, Engedal K, Selbæk G. Sense of coherence and quality of life in older in-hospital patients without cognitive impairment—a 12 month follow-up study. BMC Psychiatry 2014;14:82 10.1186/1471-244X-14-82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Agrawal R, D’Silva C. Assessment of quality of life in normal individuals using the SF36 questionnaire. Int J Cur Res Rev 2017;9:43–7. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Feldt T, Leskinen E, Kinnunen U, et al. Longitudinal factor analysis models in the assessment of the stability of sense of coherence. Pers Individ Dif 2000;28:239–57. 10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00094-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schnyder U, Büchi S, Sensky T, et al. Antonovsky's sense of coherence: trait or state? Psychother Psychosom 2000;69:296–302. 10.1159/000012411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kähönen K, Näätänen P, Tolvanen A, et al. Development of sense of coherence during two group interventions. Scand J Psychol 2012;53:523–7. 10.1111/sjop.12020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Forsberg KA, Björkman T, Sandman PO, et al. Influence of a lifestyle intervention among persons with a psychiatric disability: a cluster randomised controlled trial on symptoms, quality of life and sense of coherence. J Clin Nurs 2010;19:1519–28. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03010.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin Psychol-Sci Pr 2003;10:144–56. 10.1093/clipsy.bpg016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. van Woerkum C, Bouwman L. 'Getting things done': an everyday-life perspective towards bridging the gap between intentions and practices in health-related behavior. Health Promot Int 2014;29:278–86. 10.1093/heapro/das059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bauer GF, Roy M, Bakibinga P, et al. Future directions for the concept of salutogenesis: a position article. Health Promot Int 2019:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wiesmann U, Hannich H-J. The contribution of resistance resources and sense of coherence to life satisfaction in older age. J Happiness Stud 2013;14:911–28. 10.1007/s10902-012-9361-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.