Abstract

Objectives

We compared long-term outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) with and without a secondary precipitant.

Design and setting

Retrospective cohort study based on Danish nationwide registries.

Participants

Patients with AF with and without secondary precipitants (1996–2015) were matched 1:1 according to age, sex, calendar year, CHA2DS2-VASc score and oral anticoagulation therapy (OAC), resulting in a cohort of 39 723 patients with AF with a secondary precipitant and the same number of patients with AF without a secondary precipitant. Secondary precipitants included alcohol intoxication, thyrotoxicosis, myocardial infarction, surgery and infection in conjunction with AF.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome in this study was thromboembolic events. Secondary outcomes included AF rehospitalisation and death. Long-term risks of outcomes were examined by multivariable Cox regression analysis.

Results

The most common precipitants were infection (55.0%), surgery (13.2%) and myocardial infarction (12.0%). The 5-year absolute risk of thromboembolic events (taking death into account as a competing risk) in patients with AF grouped according to secondary precipitants were 8.3% (alcohol intoxication), 8.5% (thyrotoxicosis), 12.1% (myocardial infarction), 11.6% (surgery), 12.2% (infection), 10.1% (>1 precipitant) and 12.3% (no secondary precipitant). In the multivariable analyses, AF with a secondary precipitant was associated with the same or an even higher thromboembolic risk than AF without a secondary precipitant. One exception was patients with AF and thyrotoxicosis: those not initiated on OAC therapy carried a lower thromboembolic risk the first year of follow-up than matched patients with AF without a secondary precipitant and no OAC therapy.

Conclusions

In general, AF with a secondary precipitant was associated with the same thromboembolic risk as AF without a secondary precipitant. Consequently, this study highlights the need for more research regarding the long-term management of patients with AF associated with a secondary precipitant.

Keywords: secondary precipitant, reversible atrial fibrillation, recurrence

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study was based on high-quality nationwide registries with many years of follow-up.

Complete follow-up was possible.

Only associations could be drawn because of the retrospective and non-randomised design.

Atrial fibrillation with and without a secondary precipitant was defined from diagnosis codes at discharge.

We had no data on ECGs at discharge.

Introduction

The aetiology of atrial fibrillation (AF) remains partly unknown. Studies have shown that an inflammatory reaction inside the atria always precipitate AF.1 However, in clinical practice, AF may occur as an isolated event or together with a secondary precipitant. AF is associated with a fivefold increased risk of ischaemic stroke, and detailed treatment strategies regarding stroke prophylaxis in patients with AF occurring without secondary precipitants exist in both European and American treatment guidelines.2–5 In contrast, there is no consensus regarding stroke prophylaxis in patients with AF occurring with a secondary precipitant. Previous guidelines stated that AF occurring secondary to another precipitant usually will terminate without recurrence.2 In current guidelines, however, this statement has been omitted, and the need for data regarding AF associated with a secondary precipitant highlighted.4 5 Studies investigating long-term outcomes in AF associated with a secondary precipitant are sparse and data differentiating between different secondary precipitants and taking oral anticoagulation (OAC) therapy into account are missing.

To address this lack in current knowledge, we aimed to compare long-term outcomes including thromboembolic events, AF rehospitalisation and death in patients with AF with a secondary precipitant (including alcohol, intoxication, thyrotoxicosis, myocardial infarction, surgery and infection) and patients with AF without a secondary precipitant. Further, we were able to differentiate between patients receiving and not receiving stroke prophylaxis with OAC therapy.

Materials and methods

Data sources

In Denmark, healthcare is tax financed and with equal availability regardless of socioeconomic status. Date of birth, date and cause of death, emigration and immigration status, diagnosis and surgery codes, and so on, from all hospital contacts fulfilled prescriptions of medicine, and several other parameters are registered in different nationwide registries. Since all Danish citizens are provided a unique personal identifier code at birth (or immigration), data from the registries can be crosslinked on an individual level. We linked data from the following registries: The Danish Civil Registration System,6 The Danish National Patient Registry (diagnoses were registered in terms of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) system (ICD-8 until 1994 and in terms of ICD-10 thereafter)),7 The Danish Register of Causes of Death8 and the Danish National Registry of Medicinal Statistics (medicines were registered according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system (ATC)).9

Study population

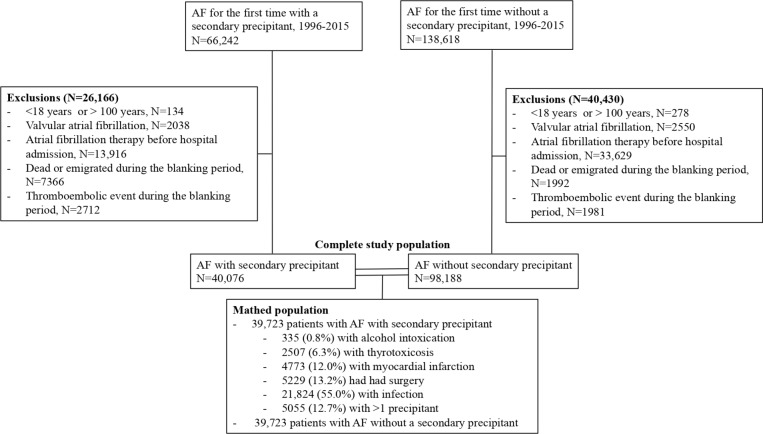

The patient selection is depicted in figure 1. We included all Danes diagnosed and admitted to a Danish hospital with AF for the first time between 1996 and 2015. Patients<18 years or >100 years and those with valvular AF (defined as AF without: rheumatic valve disease of aortic valve or mitral valve or prosthetic heart valve (any valve)) were excluded. Since there was a possibility that some of the patients had been diagnosed with AF at their general practitioner before their hospital admission, we excluded those who previously had fulfilled a prescription of antiarrhythmic therapy or rate-controlling drugs (including amiodarone, flecainide and digoxin) and those who had fulfilled a prescription of OAC therapy up to 100 days before their hospital admission. Further, patients who died or had a thromboembolic event during the hospital admission or a constructed blanking period of 4 weeks from hospital discharge to the index date were excluded.

Figure 1.

Patient selection. AF, atrial fibrillation.

Patients were grouped in those with and without a secondary precipitant. Patients who had a diagnosis of one of the following precipitants from their AF hospital admission were defined as patients with a secondary precipitant: alcohol intoxication, thyrotoxicosis, myocardial infarction and infection. Also, patients who were diagnosed with AF after, but during the same hospital admission they received surgery, were defined as having AF with a secondary precipitant. We restricted the population of patients with AF without a secondary precipitant to patients with AF without a diagnosis of a secondary precipitant from their hospital admission. Patients with AF with and without a secondary precipitant were matched 1:1 by incidence density sampling according to age (allowing a difference of up to 2 years), sex, calendar year (allowing a difference up to 2 years), CHA2DS2-VASc group (0, 1–2, >2) and OAC therapy status at the index date. Consequently, each case was matched with a control diagnosed at the same time and in the same age with AF. Further, the control had the same sex and was categorised in the same CHA2DS2-VASc group as the case. These patients comprised the study population. We used a previously described function to perform the match.10

Long-term outcomes

The index date was defined 4 weeks from AF hospital discharge. Initiation of OAC therapy and antiarrhythmic and rate controlling drugs was assessed during this blanking period from discharge to index date. Patients were followed from the index date and until the first event of the following: an outcome of interest, death, 5 years from the index date, emigration or 30 June 2015. The primary outcome of interest was thromboembolic events (a composite of ischaemic stroke, transient ischaemic attack and systemic thrombosis or embolism) while secondary outcomes included AF rehospitalisation and all-cause death. AF rehospitalisation was defined as a hospitalisation with AF as the primary discharge diagnosis. The diagnoses of AF, ischaemic stroke and myocardial infarction have been validated in the Danish registries with positive predictive values of 93%, 97% and 100%, respectively.11 12

Statistics

Kaplan-Meier curves for death were drawn and cumulative incidences of thromboembolic events (with incorporated competing risk of death) calculated using the Aalen Johansen estimator. The log-rank test and Grey’s test were used to test for differences in the cumulative incidence of long-term outcomes. Cox regression analyses were performed to calculate HRs of long-term outcomes in patients with AF with and without a secondary precipitant according to OAC therapy at the index date. All analyses were performed on the matched population. The multivariate models were adjusted for other potential confounders than the matching criteria (including comorbidities at the index date (including peripheral artery disease, heart failure, hypertension, prior thromboembolic event, ischaemic heart disease, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, prior bleeding event, cancer) and antiarrhythmic and rate-controlling therapy during the blanking period (amiodarone, digoxin, flecainide)). The analyses took matching variables into account and each group of patients with AF with a secondary precipitant was compared with its respective matches from the matching procedure. The models were tested for the assumption of proportional hazards. For specification of diagnosis codes and ATC codes, see online supplementary table 1. A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed in SAS statistical software V.9.4 or R.13

bmjopen-2018-028468supp001.pdf (206.1KB, pdf)

Other analyses

Analyses of long-term outcomes were also performed on a non-matched population including all patients available before the matching (figure 1). To account for changes in OAC therapy status over time, we did a sensitivity analysis not stratifying patients with regard to their OAC therapy status at the index date, but instead adjusting for OAC therapy status as a time-dependent variable. Consequently, new initiations and discontinuations were taking into account. The method used has been used and described previously.14–16

Patient and public involvement

This was a retrospective study based on administrative registries. Patients and the public were not involved in the development of the study.

Results

Study population

As shown in figure 1, the most common secondary precipitant was infection (21 824 patients, 55.0%). Further, 335 (0.8%) patients had a concurrent alcohol intoxication, 2507 (6.3%) had thyrotoxicosis, 4773 (12.0%) had acute myocardial infarction, 5229 (13.2%) had underwent surgery and 5055 (12.7%) had >1 precipitant. Of those with >1 precipitant, 4788 (94.7%) patients had two secondary precipitants, while 267 (5.3%) had three or four secondary precipitants. Infection and surgery were the most common combination of secondary precipitants. The patients with >1 precipitant were grouped in one group, and were not included in the other groups of patients with AF with a secondary precipitant. During the blanking period, 14% of the patients with AF and a secondary precipitant and 2% of the patients with AF without a secondary precipitant died, while 5% and 2%, respectively, had a thromboembolic event. These patients were excluded before the matching.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the matched study population are shown in table 1. In general, patients with AF with a secondary precipitant had more comorbidities than patients with AF without a secondary precipitant. Baseline characteristics of the non-matched population according to OAC therapy at the index date are shown in online supplementary tables 2 and 3. Especially, those with AF and myocardial infarction, surgery, infection and >1 precipitant were older, had more comorbidities, and higher risk scores for stroke and bleeding compared with patients with AF without a secondary precipitant. Among the patients with AF with a secondary precipitant (non-matched study population), 9.9% with alcohol intoxication, 43.9% with thyrotoxicosis, 27.2% with myocardial infarction, 21.9% with surgery, 27.1% with infection and 21.4% with >1 precipitant received OAC therapy at the index date, respectively. Among patients with AF without a secondary precipitant, 38.5% received OAC therapy at the index date. In general, for patients with AF with and without a secondary precipitant, those initiated on OAC therapy suffered from less cancer, chronic kidney disease, peripheral artery disease, and had fewer previous bleeding events than those not initiated on OAC therapy. On the other hand, they were more likely to suffer from stroke risk factors (including diabetes, heart failure, ischaemic heart disease and hypertension) than those not initiated on OAC therapy. During the first year after the index date, 9.9% and 17.3% of patients with AF with and without a secondary precipitant, respectively, had a new hospital admission with AF. One year after the index date, 19.8% and 32.7% of the patients with AF with and without a secondary precipitant, respectively, were in OAC therapy and 22.3% and 21.8% of the patients with AF with and without a secondary precipitant, respectively, were in antiarrhythmic therapy.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the matched population

| Alcohol intoxication group | Thyrotoxicosis group | Myocardial infarction group | Surgery group | Infection group | >1 precipitant group | |||||||

| secondary precipitant: | + n=335 |

− n=335 |

+ n=2507 |

−n=2507 | + n=4773 |

− n=4773 |

+ n=5229 |

− n=5229 |

+ n=21 824 |

− n=21 824 |

+ n=5055 |

− n=5055 |

| Demographics | ||||||||||||

| Age, median (IQR) | 59 (49–66) | 59 (49–66) | 73 (63–81) | 73 (63–81) | 77 (69–83) | 77 (69–83) | 75 (67–82) | 75 (67–82) | 79 (71–86) | 79 (71–86) | 76 (68–83) | 76 (68–83) |

| Male, n (%) | 276 (82.4) | 276 (82.4) | 521 (20.8) | 521 (20.8) | 2705 (56.7) | 2705 (56.7) | 2724 (52.1) | 2724 (52.1) | 10 370 (47.5) | 10 370 (47.5) | 2676 (52.9) | 2676 (52.9) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Cancer | 16 (4.8) | 29 (8.7) | 288 (11.5) | 296 (11.8) | 586 (12.3) | 688 (14.4) | 1349 (25.8) | 882 (16.9) | 4341 (19.9) | 3571 (16.4) | 958 (19.0) | 807 (16.0) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 11 (3.3) | 8 (2.4) | 61 (2.4) | 49 (2.0) | 289 (6.1) | 233 (4.7) | 352 (6.7) | 198 (3.8) | 1564 (7.2) | 748 (3.4) | 431 (8.5) | 212 (4.2) |

| COPD* | 28 (8.4) | 23 (6.9) | 234 (9.3) | 221 (8.8) | 619 (13.0) | 565 (11.8) | 665 (12.7) | 520 (9.9) | 4696 (21.5) | 2093 (9.6) | 914 (18.1) | 519 (10.3) |

| Diabetes | 26 (7.8) | 18 (5.4) | 189 (7.5) | 159 (6.3) | 575 (12.0) | 556 (11.6) | 503 (9.6) | 423 (8.1) | 2167 (9.9) | 1737 (8.0) | 498 (9.9) | 554 (11.0) |

| Heart failure | 24 (7.2) | 18 (5.4) | 445 (17.8) | 388 (15.5) | 1660 (34.8) | 1076 (22.5) | 966 (18.5) | 851 (16.3) | 5109 (23.4) | 3709 (17.0) | 1574 (31.1) | 925 (18.3) |

| Hypertension | 64 (19.1) | 78 (23.3) | 1309 (52.2) | 1249 (49.8) | 3290 (68.9) | 3204 (67.1) | 2484 (47.5) | 2695 (51.5) | 10 445 (47.9) | 11 475 (52.6) | 2694 (53.3) | 3007 (59.5) |

| IHD† | 43 (12.8) | 53 (15.8) | 333 (13.3) | 455 (18.1) | 4773 (100) | 1604 (33.6) | 1753 (33.5) | 1332 (25.5) | 4696 (21.5) | 5069 (23.2) | 3072 (60.8) | 1423 (28.2) |

| PAD‡ | 7 (2.1) | 8 (2.4) | 78 (3.1) | 83 (3.3) | 375 (7.9) | 293 (6.1) | 468 (9.0) | 233 (4.5) | 1392 (6.4) | 932 (4.3) | 448 (8.9) | 269 (5.3) |

| Prior bleeding event | 81 (24.2) | 42 (12.5) | 243 (9.7) | 249 (9.9) | 722 (15.1) | 715 (15.0) | 1267 (24.2) | 833 (15.9) | 4319 (19.8) | 3463 (15.9) | 1171 (23.2) | 811 (16.0) |

| Prior thromboembolic event | 24 (7.2) | 24 (7.2) | 138 (5.5) | 183 (7.3) | 483 (10.1) | 698 (14.6) | 571 (10.9) | 570 (10.9) | 2651 (12.1) | 2278 (10.4) | 603 (11.9) | 635 (12.6) |

| Risk scores | ||||||||||||

| CHA2DS2-VASc§ | ||||||||||||

| Median (IQR) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | 4 (3–5) | 3 (3–4) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | 4 (2–5) | 3 (2.4) |

| 0 | 158 (47.2) | 158 (47.2) | 405 (16.2) | 405 (16.2) | 0 | 0 | 391 (7.5) | 391 (7.5) | 1328 (6.1) | 1328 (6.1) | 269 (5.3) | 269 (5.3) |

| 1–2 | 118 (35.2) | 118 (35.2) | 530 (3.0) | 530 (3.0) | 670 (14.0) | 670 (14.0) | 1406 (26.9) | 1406 (26.9) | 5148 (23.6) | 5148 (23.6) | 1005 (19.9) | 1005 (19.9) |

| ≥3 | 59 (17.6) | 59 (17.6) | 1572 (62.7) | 1572 (62.7) | 4103 (86.0) | 4103 (86.0) | 3432 (65.6) | 3432 (65.6) | 15 348 (70.3) | 15 348 (70.3) | 3781 (74.8) | 3781 (74.8) |

| HAS-BLED¶ | ||||||||||||

| Median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 1 (0–2) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 3 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 355 (14.2) | 331 (13.2) | 134 (2.8) | 76 (1.6) | 289 (5.5) | 381 (7.3) | 1003 (4.6) | 1147 (5.2) | 208 (4.1) | 242 (4.8) |

| 1–2 | 232 (69.3) | 155 (46.3) | 1460 (58.2) | 1440 (57.4) | 2552 (53.5) | 2863 (54.8) | 2863 (54.8) | 2935 (56.1) | 12 130 (55.6) | 12 129 (55.6) | 2422 (47.9) | 2638 (52.2) |

| ≥3 | 103 (30.8) | 52 (15.5) | 692 (27.6) | 736 (29.4) | 2145 (6.7) | 2077 (6.5) | 2077 (39.7) | 1913 (36.6) | 8691 (39.8) | 8548 (39.2) | 2425 (48.0) | 2175 (43.0) |

| Pharmacotherapy, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| OAC** therapy, n (%) | 33 (9.9) | 33 (9.9) | 1100 (43.9) | 1100 (43.9) | 1311 (27.5) | 1311 (27.5) | 1150 (22.0) | 1150 (22.0) | 5985 (27.4) | 5985 (27.4) | 1087 (21.5) | 1087 (21.5) |

| Amiodarone | 3 | 6 (1.8) | 33 (1.3) | 62 (2.5) | 359 (7.5) | 158 (3.3) | 443 (8.5) | 163 (3.1) | 617 (2.8) | 574 (2.6) | 418 (8.3) | 154 (3.0) |

| Digoxin | 49 (14.6) | 29 (8.7) | 1000 (39.9) | 916 (36.5) | 1207 (25.3) | 1502 (31.5) | 1089 (20.8) | 1285 (24.6) | 7973 (36.5) | 6286 (28.8) | 1184 (23.4) | 1223 (24.2) |

| Flecainide | 0 (0) | 3 | 13 (0.5) | 29 (1.2) | 9 (0.2) | 32 (0.7) | 12 (0.2) | 52 (1.0) | 40 (0.2) | 156 (0.7) | 6 (0.1) | 27 (0.5) |

*COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

†IHD, ischaemic heart disease.

‡PAD, peripheral artery disease.

§CHA2DS2-VASc: Risk score for stroke: congestive heart failure/LV function, hypertension, age 65–74 years, age >74 years (two points), diabetes, stroke/transientischaemic attack/systemic embolism (two points), vascular disease, sex category (female).

¶HAS-BLED: Risk score for bleeding: hypertension, abnormal renal/liver function, history of stroke, history of bleeding, internationalnormalised ratio (left out due to missing data), age >65 years, drug consumption with antiplatelet agents/non-steroidal inflammatory drugs, alcohol abuse.

**OAC, oral anticoagulation.

Long-term outcomes

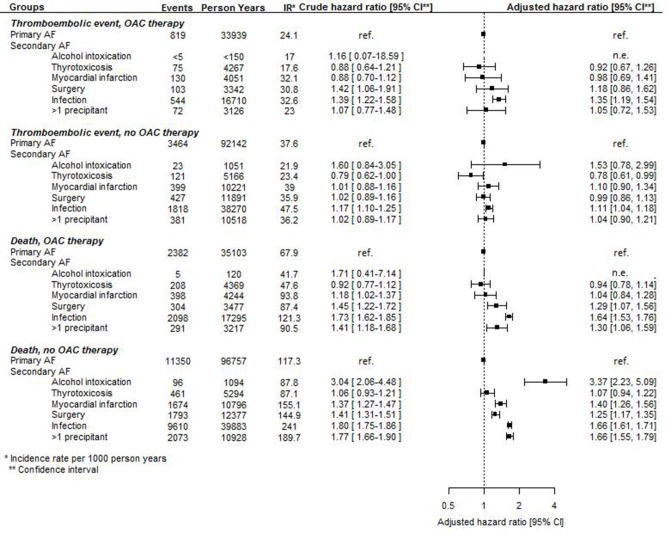

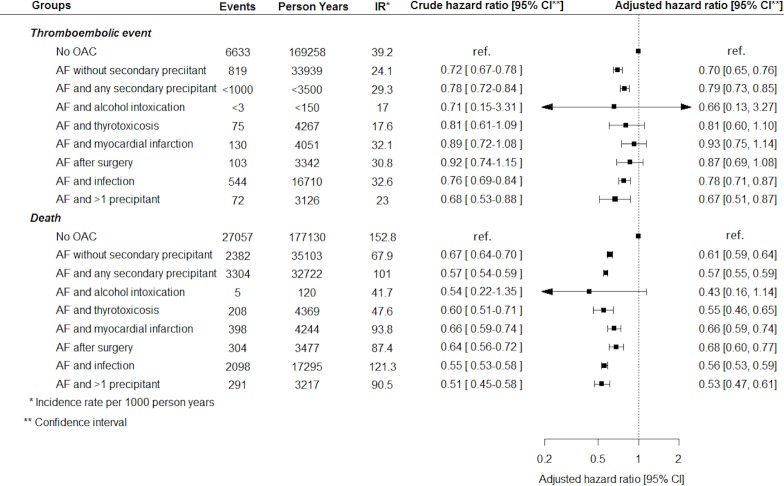

Number of events, incidence rates and crude and adjusted HRs of thromboembolic events and death in patients with AF with a secondary precipitant compared with patients with AF without a secondary precipitant initiated and not initiated on OAC therapy at the index date are presented in figure 2. With few exceptions, AF with a secondary precipitant was associated with the same thromboembolic risk as AF without a secondary precipitant. Regardless of OAC therapy status at the index date, AF with infection was associated with a significantly increased risk of thromboembolic events compared with AF without a secondary precipitant. Among those not initiated on OAC therapy, AF with thyrotoxicosis was associated with a significantly lower risk of thromboembolic events compared with AF without a secondary precipitant. In those initiated on OAC therapy, no differences in thromboembolic risk were observed between patients with AF and thyrotoxicosis and patients with AF without a secondary precipitant. All subgroups of AF with a secondary precipitant were associated with a significantly lower risk of AF rehospitalisation compared with AF without a secondary precipitant (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Number of events, incidence rates, and crude and adjusted HRs of long-term outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) with and without a secondary precipitant. OAC, oral anticoagulation.

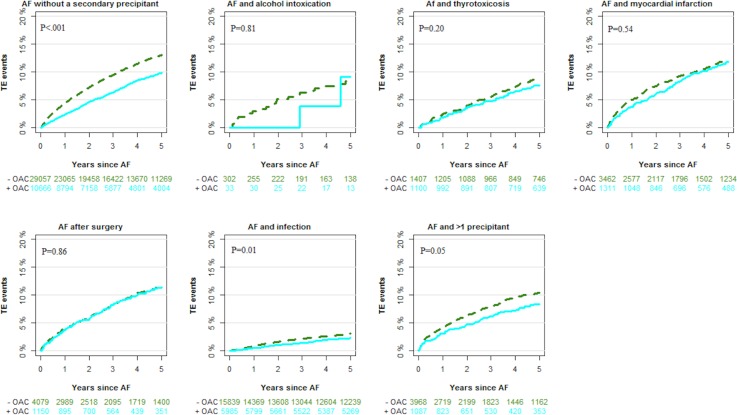

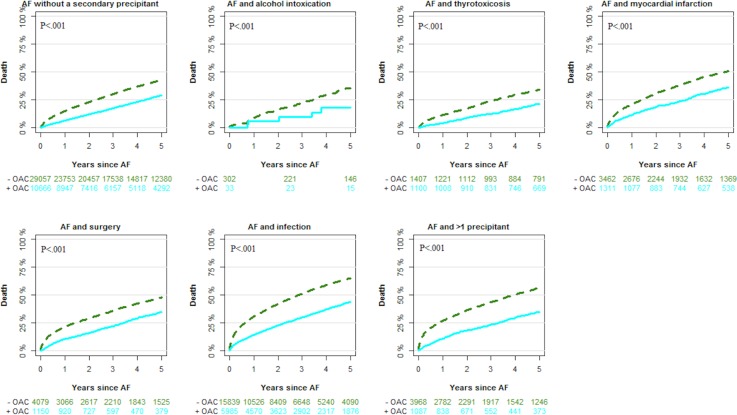

Figures 3 and 4 depict cumulative incidences of thromboembolic events and death in patients with AF with and without a secondary precipitant. During follow-up, the cumulative incidence of thromboembolic events (taking death as an competing risk into account) according to the type of secondary precipitant was 8.3% (alcohol intoxication), 8.5% (thyrotoxicosis), 12.1% (myocardial infarction), 11.6% (surgery), 12.2% (infection), 10.1% (>1 precipitant) and 12.3% (no secondary precipitant). The cumulative incidence of AF rehospitalisation was 19.6% (alcohol intoxication), 30.8% (thyrotoxicosis), 27.2% (myocardial infarction), 14.8% (surgery), 20.9% (infection), 19.3% (>1 precipitant) and 34.4% (no secondary precipitant) (not included in the figures).

Figure 3.

Cumulative incidence of thromboembolic (TE) events outcomes by secondary precipitant and oral anticoagulation (OAC) therapy at the index date. AF, atrial fibrillation.

Figure 4.

Cumulative incidence of death events outcomes by secondary precipitant and oral anticoagulation (OAC) therapy at the index date. AF, atrial fibrillation.

OAC therapy initiation compared with no OAC therapy initiation was associated with a lower thromboembolic risk in patients with AF with and without a secondary precipitant, although the results did not reach statistical significance in patients with AF with alcohol intoxication, thyrotoxicosis, myocardial infarction and surgery as secondary precipitants (figure 5).

Figure 5.

Adjusted HRs of long-term outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) initiated versus not initiated on oral anticoagulation (OAC) therapy (stratified according to type of AF).

Other analyses

The long-term risk of thromboembolic events for patients with AF with and without a secondary precipitant in the non-matched population was comparable to the risks found in the main analysis, except that AF with thyrotoxicosis reached statistical significance and hence was associated with a significantly lower risk of thromboembolic events (HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.95 for those initiated on OAC therapy and HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.92 for those not initiated on OAC therapy). Further, among those initiated on OAC therapy, AF after surgery was associated with an increased risk of thromboembolic events (HR 1.23, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.50).

The sensitivity analysis, adjusting for OAC therapy status as a time-dependent variable, revealed results similar to those found in the main analysis (online supplementary figure 1).

Discussion

We examined long-term outcomes in patients with AF with and without a secondary precipitant. The study had two main findings: first, AF with different secondary precipitants was in general associated with the same thromboembolic risk as AF without a secondary precipitant. Second, OAC initiation rates differed significantly according to type of secondary precipitant. Further, OAC therapy versus no OAC therapy was associated with a lower thromboembolic risk in those with AF and infection and >1 precipitant while no significant risk reduction was seen for patients with AF with the other secondary precipitants.

Thromboembolic risk

Despite lower rehospitalisation rates with AF, AF with a secondary precipitant was in general associated with the same thromboembolic risk as AF without a secondary precipitant. AF with thyrotoxicosis was associated with a lower thromboembolic risk compared with AF without a secondary precipitant. In contrast, AF with infection was associated with an increased thromboembolic risk compared with AF without a secondary precipitant. This is in accordance with previous findings.17–19 In two previous studies, Lubitz et al and Fauchier et al examined long-term outcomes in patients with AF secondary to a reversible precipitant compared with patients with AF without a secondary precipitant. In both studies, AF secondary to a reversible precipitant was associated with the same thromboembolic risk as AF without secondary precipitants. However, both studies were smaller and with patients included before 2012 and 2010, respectively.20 21 In summary, our results together with previous studies suggest that AF with a secondary precipitant in general, and maybe with the exception of AF with thyrotoxicosis, may be considered as similar to AF without a secondary precipitant with respect to thromboembolic risk.

OAC therapy

OAC therapy showed a tendency towards a lower thromboembolic risk in patients with AF and a secondary precipitant, but did only reach statistical significance for patients with AF and infection and >1 precipitant. Recently, Quon et al examined risk of thromboembolic events and bleeding in patients with AF and acute coronary syndrome, acute pulmonary disease and infection according to OAC therapy status after discharge. In that study, OAC therapy was not associated with a lower risk of thromboembolic events in patients with AF and the before-mentioned precipitants. However, the analyses on long-term outcomes were based on logistic regression analysis, and did therefore not include survival time in the model. Since patients with AF with a secondary precipitant in our study seemed to die at a higher rate than patients with AF without a secondary precipitant, the time perspective is crucial when studying long-term outcomes in this setting.22 Studies with a clinical randomised design would be able to show whether patients with AF with a secondary precipitant benefit from OAC therapy on the same terms as patients with AF without a secondary precipitant.

OAC treatment rates

The non-matched population allowed us to describe trends in OAC therapy initiation in patients with AF with and without a secondary precipitant. In patients with AF without a secondary precipitant, 38.5% of the patients were initiated on OAC therapy at the index date. This is in accordance with previous findings, taking into account that our study period went back to 1996 when treatment rates were lower than today.23 24 In 2017, Chean et al assessed current practice of AF among critically ill patients with new-onset AF. The study was based on questionnaires answered by members of the Intensive Care Society in UK. The results revealed that 63.8% of the respondents would not regularly anticoagulate critically ill patients with new-onset AF. We found important differences in OAC therapy initiation rates in patients with AF with a secondary precipitant according to the type of precipitant. Patients with alcohol intoxication had the lowest initiation rate of OAC therapy (9.9%). Almost 50% of this patient group had a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 and hence no indication for OAC therapy. Further patients with alcohol abuse may have poor compliance and increased bleeding risk.25 Consequently, there may be caution among physicians in prescribing OACs for this patient group. In 2011, Traube and colleagues reviewed the literature with respect to thromboembolic risk in patients with AF and thyrotoxicosis. They concluded that OAC therapy should be initiated for those patients who did not have any contraindications for treatment.26 This could explain the high OAC treatment initiation rates in this patient group (43.9%).

Limitations

First of all, this study was a retrospective registry-based study and hence no causative relationships can be drawn. Our definition of AF with a secondary precipitant was based on diagnosis codes from hospital admissions with AF and a reversible precipitant. Both diagnoses were registered at the discharge date, and therefore we may have included patients in the group of AF with a secondary precipitant who developed AF before the secondary precipitant (eg, patients admitted with AF who developed infection during their hospital stay), and thereby should have been classified as patients with AF without a secondary precipitant. Moreover, we had no access to patient files, and we did not know the duration of AF or whether the patients were discharged in sinus rhythm or with AF. Also, no data were available with regard to the physicians’ considerations when choosing between OAC therapy and no OAC therapy, patients compliance and measurements of international normalised ratio and time in therapeutic range for warfarin users.

The retrospective, registry-based nature of this study also precluded consideration of the specific impact of the molecular causes of both acute and chronic AF, including inflammatory activation and impaired nitric oxide (NO) availability and signalling. For example, specific patterns and extent of inflammatory activation associated with intercurrent infection could not be determined, and while impaired NO antiaggregatory effect occurs in acute AF27 and increased plasma concentrations of asymmetric dimethylarginine, which inhibits enzymatic generation of NO, predict thromboembolic risk in AF,28 neither of these parameters were measured in the current study. However, this study was based on a nationwide cohort of patients with many years of follow-up and data from high-quality registries. It reveals unexpected results that should be considered in future treatment guidelines for patients with AF and a secondary precipitant.

Conclusion

In this study, we found that patients with AF and a secondary precipitant carried a similar associated thromboembolic risk as those with AF without a secondary precipitant. Current guidelines lack data on this subject and our results suggest that AF in relation to known triggers may be considered as AF in general.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: The study idea was conceived by AG, TK and ELF. Study design was developed by all authors. Data analyses were made by AG. AG drafted the first version of the paper and all authors participated in the critical discussions and interpretation of findings. All authors have participated in the revisions of the draft and have approved the final version.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: AG: none. TK: consultant fees from BMS, Astra Zeneca, Roche, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bayer, MSD. JBO: speaker for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, and AstraZeneca. Consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim and Novo Nordisk. Funding for research from Bristol-Myers Squibb and The Capital Region of Denmark, Foundation for Health Research. ANB: none. JHB: none. GHG: research grants from Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca and Boehring Ingelheim. CT-P: consultant fees and research funding from Bayer and Biotronic. LK: none. ELF: has previously received research funding from Janssen and Janssen and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Approval from the Research Ethics Committee System is not required in retrospective registry-based studies in Denmark. The Danish Data Protection Agency approved use of data for this study (ret.no: 2007-58−0015/GEH-2014–013 I-Suite no: 02731).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: This study was based on deidentified data about the entire Danish population. No data are available.

References

- 1. Procter NEK, Stewart S, Horowitz JD. New-onset atrial fibrillation and thromboembolic risk: cardiovascular syzygy? Heart Rhythm 2016;13:1355–61. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fuster V, Rydén LE, Cannom DS, et al. . 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused updates incorporated into the ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of cardiology Foundation/American heart association Task force on practice guidelines. Circulation 2011;123:e269–367. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318214876d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lip GYH, Lane DA. Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. JAMA 2015;313:1950–62. 10.1001/jama.2015.4369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, et al. . 2016 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J 2016;37:2893–962. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al. . 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2014;130:e199–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pedersen CB. The Danish civil registration system. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7_suppl):22–5. 10.1177/1403494810387965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish national patient register. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7_suppl):30–3. 10.1177/1403494811401482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Helweg-Larsen K. The Danish register of causes of death. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7_suppl):26–9. 10.1177/1403494811399958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wallach Kildemoes H, Toft Sørensen H, Hallas J. The Danish national prescription registry. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7_suppl):38–41. 10.1177/1403494810394717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Locally Written SAS Macros - Division of Biomedical Statistics and Informatics - Mayo Clinic Research [Internet]. Mayo Clinic. [cited 2017 May 3]. Available: http://www.mayo.edu/research/departments-divisions/department-health-sciences-research/division-biomedical-statistics-informatics/software/locally-written-sas-macros

- 11. Rix TA, Riahi S, Overvad K, et al. . Validity of the diagnoses atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter in a Danish patient registry. Scand Cardiovasc J 2012;46:149–53. 10.3109/14017431.2012.673728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Krarup L-H, Boysen G, Janjua H, et al. . Validity of stroke diagnoses in a national register of patients. Neuroepidemiology 2007;28:150–4. 10.1159/000102143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [Internet]. [cited 2017 Sep 19]. Available: https://www.R-project.org/

- 14. Olesen JB, Lip GYH, Kamper A-L, et al. . Stroke and bleeding in atrial fibrillation with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2012;367:625–35. 10.1056/NEJMoa1105594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lamberts M, Lip GYH, Hansen ML, et al. . Relation of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to serious bleeding and thromboembolism risk in patients with atrial fibrillation receiving antithrombotic therapy: a nationwide cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2014;161:690–8. 10.7326/M13-1581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fosbøl EL, Gislason GH, Jacobsen S, et al. . The pattern of use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) from 1997 to 2005: a nationwide study on 4.6 million people. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2008;17:822–33. 10.1002/pds.1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gundlund A, Kümler T, Olesen JB, et al. . Comparative thromboembolic risk in atrial fibrillation patients with and without a concurrent infection. Am Heart J 2018;204:43–51. 10.1016/j.ahj.2018.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Walkey AJ, Hammill BG, Curtis LH, et al. . Long-Term outcomes following development of new-onset atrial fibrillation during sepsis. Chest 2014;146:1187–95. 10.1378/chest.14-0003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Adderley NJ, Nirantharakumar K, Marshall T. Risk of stroke and transient ischaemic attack in patients with a diagnosis of resolved atrial fibrillation: retrospective cohort studies. BMJ 2018;361:k1717 10.1136/bmj.k1717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lubitz SA, Yin X, Rienstra M, et al. . Long-term outcomes of secondary atrial fibrillation in the community: the Framingham heart study. Circulation 2015;131:1648–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fauchier L, Clementy N, Bisson A, et al. . Prognosis in patients with atrial fibrillation and a presumed “temporary cause” in a community-based cohort study. Clin Res Cardiol 2017;106:202–10. 10.1007/s00392-016-1040-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Quon MJ, Behlouli H, Pilote L. Anticoagulant use and risk of ischemic stroke and bleeding in patients with secondary atrial fibrillation associated with acute coronary syndromes, acute pulmonary disease, or sepsis. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2017:500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gadsbøll K, Staerk L, Fosbøl EL, et al. . Increased use of oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation: temporal trends from 2005 to 2015 in Denmark. Eur Heart J 2017;38:ehw658 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gundlund A, Xian Y, Peterson ED, et al. . Prestroke and poststroke antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation: results from a nationwide cohort. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e180171 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roth JA, Bradley K, Thummel KE, et al. . Alcohol misuse, genetics, and major bleeding among warfarin therapy patients in a community setting. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2015;24:619–27. 10.1002/pds.3769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Traube E, Coplan NL. Embolic risk in atrial fibrillation that arises from hyperthyroidism: review of the medical literature. Tex Heart Inst J 2011;38:225–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Procter NEK, Ball J, Liu S, et al. . Impaired platelet nitric oxide response in patients with new onset atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol 2015;179:160–5. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.10.137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Horowitz JD, De Caterina R, Heresztyn T, et al. . Asymmetric and symmetric dimethylarginine predict outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:721–33. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.05.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-028468supp001.pdf (206.1KB, pdf)