Abstract

Introduction

An increasing proportion of cancer surgeries are ambulatory procedures requiring a stay of 1 day or less in the hospital. Providing patients and their caregivers with ongoing, real-time support after discharge aids delivery of high-quality postoperative care in this new healthcare environment. Despite abundant evidence that patient self-reporting of symptoms improves quality of care, the most effective way to monitor and manage this self-reported information is not known.

Methods and analysis

This is a two-armed randomised, controlled trial evaluating two approaches to the management of patient-reported data: (1) team monitoring, symptom monitoring by the clinical team, with nursing outreach if symptoms exceed normal limits, and (2) enhanced feedback, real-time feedback to patients about expected symptom severity, with patient-activated care as needed.

Patients with breast, gynaecologic, urologic, and head and neck cancer undergoing ambulatory cancer surgery (n=2750) complete an electronic survey for up to 30 days after surgery that includes items from a validated instrument developed by the National Cancer Institute, the Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE). Information provided to patients in the Enhanced Feedback group is procedure-specific and based on updated PRO-CTCAE data from previous patients. Qualitative interviews are also performed. The primary study outcomes assess unplanned emergency department visits and symptom-triggered interventions (eg, nursing calls and pain management referrals) within 30 days, and secondary outcomes assess the patient and caregiver experience (ie, patient engagement, patient anxiety and caregiver burden).

Ethics and dissemination

This study is approved by the Institutional Review Board at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. The relationships between the study team and stakeholders will be leveraged to disseminate study findings. Findings will be relevant in designing future coordinated care models targeting improved healthcare quality and patient experience.

Trial registration number

Keywords: surgery, oncology, quality in health care, health informatics, patient-reported outcomes

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is a large randomised, controlled trial that will help determine an effective mechanism for patient-reported data collection and symptom monitoring after ambulatory surgery.

Optimal integration of self-reported symptom data into healthcare systems has the potential to improve surgical outcomes and enhance patient-clinician communication.

Patient engagement is a major driver of study design, implementation and future dissemination, as this study includes former patients and caregivers as members of the core study team.

The study population consists largely of patients with high health and computer literacy, which may be a potential threat to external validity.

While the use of electronic patient-reported symptom monitoring, the control arm of this study, is not standard for most patients undergoing postoperative care worldwide and may limit the immediate generalisability of the results, this study may provide important guidance for the development of such systems in the future.

Introduction

Increasing numbers of surgical procedures, including major cancer procedures (eg, mastectomies, hysterectomies and prostatectomies), are being performed as short-stay (one midnight) or ambulatory surgeries.1–3 Although there are many advantages to shorter hospital stays, this model adds complexities to the delivery of high-quality, patient-centred care, particularly for cancer patients and their caregivers, who are often still struggling with a new cancer diagnosis. Patients often leave the surgical centre while experiencing symptoms that were previously attended to by the healthcare team.4 Managing symptoms at home can be challenging for patients and caregivers who may have difficulty distinguishing normal and expected symptoms from potentially serious adverse events (SAEs).5 Without information and risk awareness, patients may delay seeking care, with severe consequences, or they may experience unnecessary anxiety and seek unnecessary care.6 In focus groups and interviews conducted to inform the design of the current study, patients and caregivers conveyed feelings of stress and reported feeling unprepared to interpret and monitor postoperative symptoms.

Patient-reported outcome (PRO) measurement is rapidly becoming a standard of care throughout medicine that can aid in monitoring symptom burden. However, the best way to integrate and act on patient-reported data is unclear.7 There is abundant and broad evidence that PRO data can improve communication with the clinical team, symptom control, quality of life and patient satisfaction.8–10 One large randomised trial comparing routine collection of PROs with usual care during chemotherapy showed that among patients who received the PRO intervention, quality of life improved (34% vs 18%), and these patients were less likely to be seen in the emergency department (34% vs 41%; p=0.02) or hospitalised (45% vs 49%; p=0.08).7 Although progress has been made to better understand how symptom data might be best incorporated into clinical care among non-surgical patients, little work has been done among patients having surgery. Routine monitoring of symptoms in surgical patients, with outreach by the clinical team when severity exceeds an expected range, may identify problems at an earlier stage and avoid or minimise adverse events. Providing patients with feedback about expected symptom severity and allowing them to activate care as needed may allow for the identification of these adverse events before they progress, while also decreasing patient anxiety and unplanned care, such as unnecessary visits to the emergency department. It is unknown whether providing this kind of feedback to patients would affect care patterns and patient outcomes. This evidence gap provides motivation for the design of the current study as well as the selection of its outcome measures.

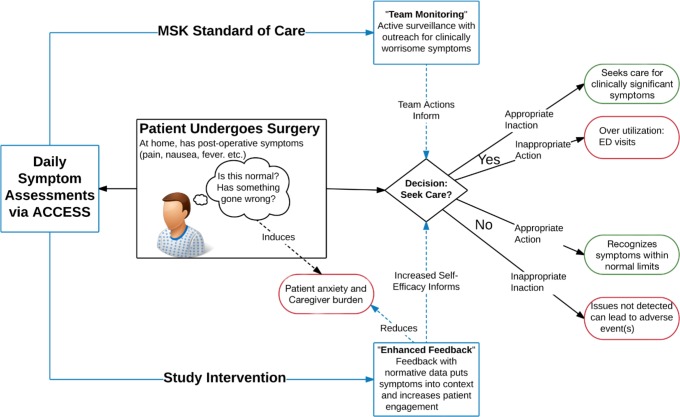

This randomised controlled trial will assess two approaches to the management of patient-reported symptoms and their potential impact in decreasing emergency department visits, patient anxiety and caregiver burden up to 30 days after ambulatory cancer surgery. One approach is called team monitoring, in which symptoms are monitored by the clinical team, with nursing outreach if symptoms exceed normal limits. The second approach is called enhanced feedback, which provides patients with real-time feedback about expected symptom severity, with patient-activated care as needed. The study aligns with the Institute of Medicine’s goal of determining how to deliver an ideal patient care experience that is safe, effective, efficient, patient-centred, timely and equitable.11–13

The study model (figure 1) is predicated on the hypothesis that daily, patient-driven symptom reporting with normative data feedback about expected symptom burden relative to previous patient reports (enhanced feedback) will increase patients’ self-efficacy14 and their confidence that they can manage their symptoms during the recovery period.15 This has been shown to be a predictor of decreased symptoms and better physical function.15 16 On the basis of this model, patients may avoid unnecessary emergency department visits by better understanding expected symptoms and by achieving more efficient and effective communication with their healthcare team.

Figure 1.

Study conceptual model. ACCESS, ambulatory cancer care electronic symptom self-reporting; ED, emergency department; MSK, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

The study will garner important information for incorporating PROs into postoperative care and aiding in the development of tailored perioperative care pathways for patients with cancer. The key lessons learnt may be used to support the implementation of strategies for population health management for non-cancer treatments that can also cause burdensome symptoms. Utilising a similar patient-reporting mechanism may benefit smaller outpatient facilities that do not have the personnel resources necessary to provide intensive monitoring of patient symptoms. It is expected that this study will also be highly relevant in designing coordinated care models targeting improved healthcare value, such as the Oncology Care Model and the Perioperative Surgical Home.

Methods and analysis

Study design

This is a parallel group randomised, controlled trial with 1:1 procedure-stratified randomisation between two arms, team monitoring and enhanced feedback. The study design follows Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) standards, including patient engagement, research methods, data integrity and analysis (including stratification by surgical procedure), handling of missing data and heterogeneity of treatment effect.

Patient and public involvement

The study team recruited a group of committed stakeholders that include clinicians, researchers, hospital leadership and advocates from patient and caregiver support groups, as well as former patients and caregivers who join the team as patient partners. The patient partners have been engaged since the beginning of study development, and they offer their experiences to help inform the design, conduct and dissemination of the research. The patient partners and study stakeholders contributed to the development of data collection tools (including the enhanced feedback reports given to patients) and to the creation of study information sheets, recruitment letters and qualitative interview guides. They also helped to refine recruitment initiatives that ensured minimal burden to participants, which resulted in increased enrolment over the first year of recruitment. Through their engagement, the study will ultimately be more patient-centred and will lead to a greater application of results by the larger healthcare community.

Objectives and scientific aims

The primary study outcome is to determine if providing enhanced reporting to patients regarding their symptoms will impact potentially avoidable urgent care and emergency department visits (ie, those that do not result in hospital admission) up to 30 days after ambulatory cancer surgery. In addition, we will examine readmissions and symptom-triggered interventions (pain management referrals, nursing calls) up to 30 days after ambulatory cancer surgery. Secondary outcomes include patient engagement, patient anxiety and caregiver burden, using validated PRO measures and qualitative interviews.

Cohort 1: team monitoring

Team monitoring is the current standard of care for patients at the Josie Robertson Surgical Center (JRSC) at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK). Patients report their symptoms via an electronic questionnaire called the Recovery Tracker, delivered through an in-house informatics platform known as the ambulatory cancer care electronic symptom self-reporting (ACCESS) system. The healthcare team receives portal-secure message alerts if patients report symptoms above a specified threshold and contact the patient by phone during business hours. Given the need for real-time feedback for some symptoms, patients who report very severe symptoms receive a bold red alert instructing them to immediately call the office (or the call team outside business hours) or seek medical attention. The response thresholds (ie, when to give which alert) for each question are set individually and have been refined based on feedback from the clinical teams (ie, surgeons and office practice nurses). For example, mild-moderate pain 3 days after surgery is expected, but moderate shortness of breath 3 days after surgery is not expected and potentially concerning.

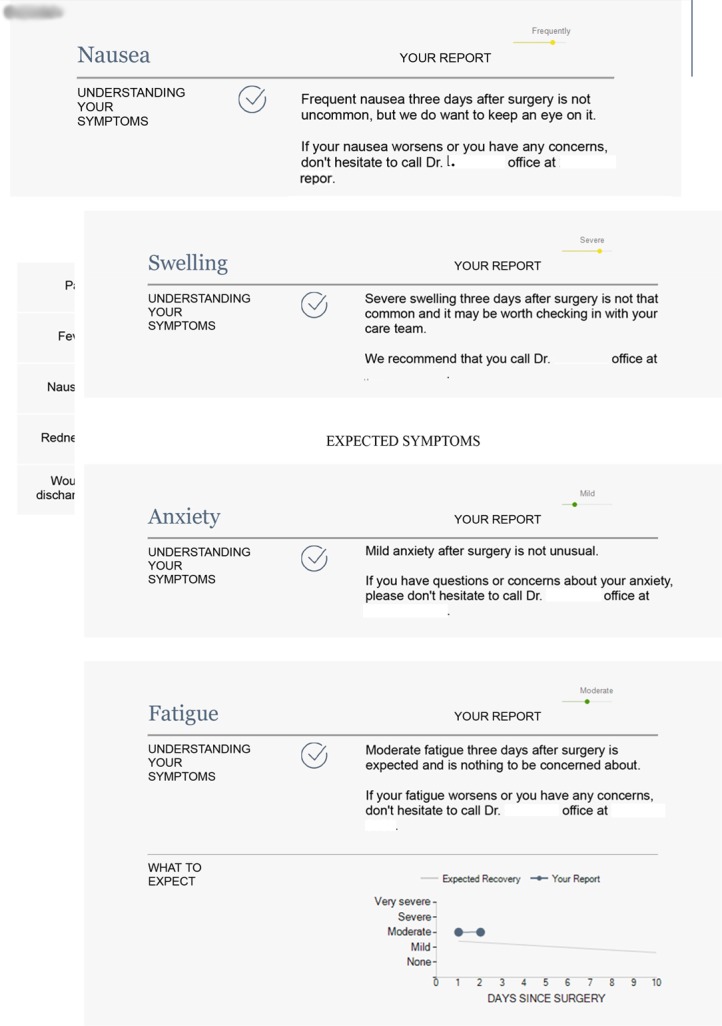

Cohort 2: enhanced feedback

In the enhanced feedback cohort, the ACCESS system provides tailored normative data visualisations that offer context and education to patients regarding expected symptom severity (figure 2). This enhanced feedback report was generated using an iterative rapid application development process by the research team in collaboration with MSK surgeons and nurses, former patients and caregivers, the study’s patient partners and patient advocates from cancer support groups. Details regarding the optimisation of the feedback report are described elsewhere.17

Figure 2.

Example of enhanced feedback report.

The feedback report consists of periodically updated PRO data from previous patients that are stratified by surgical procedure and postoperative date. As a result, patients can see their recovery trajectories relative to others who have undergone the same procedure. Care is ‘patient-activated’, in that patients use the information about expected symptoms to decide whether they should call the care team, for instance, if they experience symptoms that are more severe or more prolonged than expected. Similar to the team monitoring cohort, patients who report very severe symptoms are instructed to immediately contact their physician’s office, and the care team receives an alert. Alerts to the clinical team can only be monitored during business hours, so for care after hours, all patients must call the doctor on call.

Participants, setting and recruitment

Patients older than 18 years who are scheduled for ambulatory cancer surgery at the JRSC at MSK are eligible for study participation. Disease types include breast, gynaecologic, urologic, and head and neck cancers or benign tumours. Patients must be able to access a computer, tablet or mobile phone to complete the electronic surveys. Caregivers of eligible patients are also eligible for study participation; they must be older than 18 years, be willing to provide an email address and have access to a computer, tablet or mobile phone to complete electronic surveys. A total of 2750 patients and 1375 caregivers will be recruited for this study over a period of 3 years. Enrolment began in August 2017 and is projected to end in September 2019.

Eligible patients receive written educational materials that describe the study via the MyMSK patient portal, email or a letter mailed to their home. The study team then attempts to contact patients by phone before surgery to obtain their verbal consent to participate in the study. If the study team is unable to contact the patient prior to the day of surgery, the patient is approached at one of their clinic appointments or in the waiting room when they arrive for surgery. At the time of consent, patients are also asked to identify a caregiver who will be actively involved in their recovery. If permitted by the patient, the study team obtains the caregiver’s contact information to invite them to participate in the study as well.

Randomisation is implemented through the MSK Clinical Research Database, a fully secure, password-protected database that ensures full allocation concealment. It will be performed within 1 week of the patient’s surgical visit. Randomisation is stratified by procedure (eg, breast: mastectomy (with or without sentinel and axillary nodal dissection), tissue expander placement or other; gynaecologic: laparoscopic or robotic procedure, laparotomy or other; urologic: laparoscopic or robotic prostatectomy, laparoscopic or robotic partial or total nephrectomy, laparotomy or other; head and neck: thyroidectomy) and will be implemented by randomly permuted blocks of random length. The trial will not be blinded, as it relies on patient knowledge (ie, how a patient’s scores compare with other patients’ scores) as a key part of the intervention.

Study measures and data collection

The ACCESS System and Recovery Tracker

The ACCESS system is designed to enable real-time postoperative symptom monitoring. Patients undergoing surgery at the JRSC, an ambulatory surgery centre at MSK, are invited to complete the Recovery Tracker through the MyMSK patient portal. The interface was built with a responsive design, so patients can complete the Recovery Tracker via computers, tablets or mobile phones. Patients are prompted to report on 11 items adapted from a validated symptom assessment instrument, the National Cancer Institute (NCI)’s Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE),18 three additional surgical symptom questions and two questions about seeking urgent care or a doctor during the first 10 days after surgery. Over the following 20 days, patients have the option to complete additional surveys on demand, but they are not prompted to do so. Patients, caregivers, nurses, surgeons and anaesthesiologists participated in the selection of these items. See table 1 for the study assessment schedule.

Table 1.

Study assessment schedule

| Item | No of items | Preoperative time point | Postoperative time point | |||

| Preoperative (day of consent – POD1) |

POD 1–10 | POD14 (+7/–3 days) |

POD30 (±10 days) |

POD60 (±14 days) |

||

| Patient | ||||||

| Recovery Tracker (including PRO-CTCAE symptoms and anxiety items, and additional questions) | 20 | Daily | Available to complete, if desired (POD11–30) | |||

| Emergency department visits | X | |||||

| Readmission | X | |||||

| Adverse events | X | |||||

| Patient activation measure | 10 | X | X | X | ||

| Patient interviews | X | |||||

| Caregiver | ||||||

| Caregiver reaction assessment and demographics* | 24 | X | X | |||

| Caregiver interviews | X | |||||

*Caregiver demographics collected include date of birth, sex, race/ethnicity, education level, employment status, relationship to patient and basic caregiving information. Demographic information is collected at POD14 (+7/–3 days).

POD, postoperative day; PRO-CTCAE, Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events.

Emergency department visits and adverse events

The study team will evaluate the frequency of urgent care centre visits, readmissions and symptom-triggered interventions (eg, pain management referrals, nursing calls triggered by alerts generated by the ACCESS system or initiated by the patient) for 30 days after surgery. These data are available as structured fields in the MSK enterprise data warehouse and will be audited through chart review of randomly selected patient records.

Patient engagement, patient anxiety and caregiver burden

Patient engagement is evaluated preoperatively, as well as at 14 days (window of 11–21 days) and 60 days (window of 46–74 days) postoperatively using the Patient Activation Measure (PAM), a validated PRO measure developed to assess the engagement of patients in their care.19 This measure was selected because it evaluates a key concept of interest in the study, was rigorously developed with qualitative and quantitative methods and has strong psychometric properties. The PAM yields only a total score that will be used in the analysis. Patients are sent the PAM through the MyMSK patient portal. Patient anxiety is measured daily for 10 days following surgery using three PRO-CTCAE anxiety questions on the Recovery Tracker.

Caregiver burden is evaluated postoperatively at 14 and 60 days (with similar windows) using the Caregiver Reaction Assessment (CRA). The CRA is designed to assess the impact of caregiving on disrupted schedules, self-esteem and financial and health problems.20 It was selected because it is well-targeted to the outcomes of interest and was developed among partners of patients with cancer.21 Caregivers are sent the CRA and a brief demographic questionnaire through REDCap, a secure web application for building and managing online surveys and databases.

Qualitative patient and caregiver interviews

Patient engagement and caregiver burden are also being evaluated using qualitative interviews, with a sample of each of the randomised cohorts. Qualitative interviews are conducted in a subsample of patients and their caregivers throughout the study. Patients and their caregivers from both randomised cohorts are selected, with the goal to interview a heterogeneous patient sample. Participants selected for qualitative interviews represent a range of procedure types and ages. The interviews will continue until data saturation is reached (ie, no new themes identified). It is anticipated that data saturation will be reached after approximately 30 patient and 30 caregiver interviews.

Data analysis

Sample size and power calculations were based on the primary outcome, the difference in emergency department visits without admission, between the enhanced feedback and team monitoring arms. Based on current MSK data, we expect that for every 1000 eligible patients treated surgically at JRSC, 69 patients will make emergency department visits. We also estimate that of these 69 patients, 28 will require readmission, and hence 41 will have visited the emergency department unnecessarily. The majority of such unnecessary visits are related to concerns about symptoms, which might be avoided if patients have a better understanding of expected symptom severity. Using a traditional alpha of 5% and an event rate of 4.1% in the control group, a sample size of 2750 will provide a power of 85% to detect a 50% relative risk reduction.

The primary analysis will compare, between groups, the proportion of patients with at least one emergency department visit without admission within 30 days of surgery by logistic regression with randomisation strata as covariates. A difference between proportions will be calculated along with a 95% CI by applying the OR from the regression to the event rate in the control group. A similar statistical approach will be taken for the proportion of patients referred to pain management and unplanned clinic visits. For nursing follow-up calls, phone referrals and rates of adverse events, we will use both a binary approach (eg, at least one nursing call vs no nursing call) and an analysis of count data using negative binomial regression with randomisation strata as covariates. For all binary endpoints, an event will be counted only if it occurs within 30 days of surgery.

For the endpoints of patient engagement and caregiver burden, linear regression with randomisation strata as covariates for each subscale separately will be performed. For all analyses, an estimate of the difference between groups along with a 95% CI and a two-sided p value for the null hypothesis of no difference between groups will be reported. For the endpoint of patient anxiety, daily anxiety scores will be entered as a continuous outcome variable into a longitudinal mixed effects model with time, treatment and treatment-by-time interaction as predictors and randomisation strata as covariates. As all data are collected after randomisation, both the treatment term and the treatment-by-time interaction term are indicators of a treatment effect.

In exploratory analysis, the mean of each PRO-CTCAE item (0–4 scale) will be compared between groups during the 10-day postoperative daily reporting period using the same longitudinal mixed-effects model described above for anxiety with time, treatment and treatment-by-time interaction as predictors and randomisation strata as covariates. All available data will be used in these models. This likelihood-based approach to the analysis of longitudinal PRO data provides valid estimates of intervention effects in the presence of ignorable missing data and is known to be robust to non-ignorable missing data if covariates and previous values of the outcome explain much of the missingness.

Supplemental analysis will also employ longitudinal mixed-effects ordinal logistic models to compare ordinal PRO-CTCAE scores between arms. Qualitative interviews will be recorded and transcribed verbatim. The data will be coded using a line-by-line approach, where all concepts will be labelled by major and minor themes. Coding will take place as soon as possible after an interview so that findings can inform subsequent interviews in an iterative fashion. Codes (ie, patient quotations) and their major and minor themes will be organised and analysed using NVivo qualitative analysis software (QSR International). Patient characteristics (eg, age, disease condition, procedure) will also be incorporated into the qualitative database to help identify groups that might experience the system differently (eg, elderly patients or those with lower education levels).

Approach to missing data, data safety, monitoring and quality assurance

Baseline characteristics between those with and those without missing data will also be compared to assess for bias. The rate of missing data is expected to be low. The main threat to data completion involves the caregiver and patient questionnaires obtained at 2 weeks and 2 months, respectively. In addition to automated electronic reminders, a research assistant follows up with patients who have missing data. Routine data quality reports are generated to assess missing data and inconsistencies. Accrual rates and accuracy of assessments are monitored periodically throughout the study period. Data are available immediately when a patient or caregiver completes a survey, which allows for follow-up collection of missing and incorrect data as needed.

Death, life-threatening events and adverse events that result in inpatient hospitalisation (other than for planned procedures or admissions) are classified as SAEs. All SAEs are reviewed by the Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (DSMC) annually. The DSMC also monitors the study for safety and study conduct to ensure that study conduct, accrual and participant data collection are adequate.

Ethics and dissemination

Participants are informed of their right to refuse or withdraw at any point during the study without compromising medical and other care. They are also assured that all information collected during study participation is considered confidential. Though there are minimal risks to participants, they are instructed to immediately contact their physician’s office or seek medical attention if they experience distress when they complete the surveys.

The routine collection of PROs creates new pathways to enhance patient-centred care by fostering more effective patient-clinician communication, education and expectation setting, and improved patient outcomes. Although data collection is currently underway to answer the main study questions, this study has also opened new doors to patient engagement in clinical research. By creating dynamic partnerships with former patients and caregivers, the study team will ensure that findings are understandable not only to scientific and healthcare audiences but to patients, caregivers and their advocates. The study team is committed to the rapid dissemination and implementation of study results, which will be presented at relevant scientific conferences and will be published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal. Findings will also be disseminated to other NCI-designated Cancer Centers by presenting at the Comprehensive Cancer Center Consortium for Quality Improvement. Further, the American College of Surgeons has recently embarked on the development of a national-scale PROs initiative, into which this system could be embedded.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge their Patient Partners and study stakeholders, who have contributed significantly to the study design, choice of outcomes and ACCESS system development.

Footnotes

Contributors: JC, LT, BAS, AV, DS, PS and ALP contributed to the conception of the study. CS, LT, JSA, JC, EB, MM, DS, PS, AV, BAS and ALP participated in the design of the study. CS, LT, JSA, JC, EB, MM, DS, PS, AV, BAS and ALP read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: Research reported in this publication is funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (IHS-1602-34355). This research is also funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Disclaimer: The statements in this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee.

Competing interests: CS, LKT, JSA, JC, MM, DS, PS, AV, BAS, AP declare that they have no competing interests. EB declares the following: Employer: University of North Carolina; Research funding: NCI, PCORI; Editorial Board: Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA); Consultant on research projects: Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Research Triangle Institute; Scientific advisor: Sivan Healthcare, Self Care Catalysts, Carevive.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved, as described in the text, in May 2017 (with subsequent minor amendments) by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Institutional Review Board (approval number 17-293). Please see the full Institutional Review Board-approved protocol included with submission.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Hollenbeck BK, Dunn RL, Suskind AM, et al. . Ambulatory surgery centers and outpatient procedure use among Medicare beneficiaries. Med Care 2014;52:926–31. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hollenbeck BK, Dunn RL, Suskind AM, et al. . Ambulatory surgery centers and their intended effects on outpatient surgery. Health Serv Res 2015;50:1491–507. 10.1111/1475-6773.12278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cullen KA, Hall MJ, Golosinskiy A. Ambulatory surgery in the United States, 2006. Natl Health Stat Report 2009;11:1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Apfelbaum JL, Chen C, Mehta SS, et al. . Postoperative pain experience: results from a national survey suggest postoperative pain continues to be undermanaged. Anesth Analg 2003;97:534–40. 10.1213/01.ANE.0000068822.10113.9E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Basch E, Iasonos A, McDonough T, et al. . Patient versus clinician symptom reporting using the National cancer Institute common terminology criteria for adverse events: results of a questionnaire-based study. Lancet Oncol 2006;7:903–9. 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70910-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sprigg N, Machili C, Otter ME, et al. . A systematic review of delays in seeking medical attention after transient ischaemic attack. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2009;80:871–5. 10.1136/jnnp.2008.167924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. . Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. JCO 2016;34:557–65. 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kotronoulas G, Kearney N, Maguire R, et al. . What is the value of the routine use of patient-reported outcome measures toward improvement of patient outcomes, processes of care, and health service outcomes in cancer care? A systematic review of controlled trials. JCO 2014;32:1480–501. 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.5948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Valderas JM, Kotzeva A, Espallargues M, et al. . The impact of measuring patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: a systematic review of the literature. Qual Life Res 2008;17:179–93. 10.1007/s11136-007-9295-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Velikova G, Booth L, Smith AB, et al. . Measuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient well-being: a randomized controlled trial. JCO 2004;22:714–24. 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goeschel C. Crossing the quality chasm: who will lead? Mich Health Hosp 2002;38:12–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gold KS. Crossing the quality chasm: creating the ideal patient care experience. Nurs Econ 2007;25:293–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Madhok R. Crossing the quality chasm: lessons from health care quality improvement efforts in England. Proc 2002;15:77–83. Discussion 83–4 10.1080/08998280.2002.11927816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lev EL. Bandura's theory of self-efficacy: applications to oncology. Sch Inq Nurs Pract 1997;11:21–37. Discussion 39–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Foster C, Grimmett C, May CM, et al. . A web-based intervention (restore) to support self-management of cancer-related fatigue following primary cancer treatment: a multi-centre proof of concept randomised controlled trial. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:2445–53. 10.1007/s00520-015-3044-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brown CT, van der Meulen J, Mundy AR, et al. . Defining the components of a self-management programme for men with uncomplicated lower urinary tract symptoms: a consensus approach. Eur Urol 2004;46:254–63. Discussion 263 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ancker JS, Stabile C, Carter J, et al. . Informing, reassuring, or alarming? balancing patient needs in the development of a postsurgical symptom reporting system. Proceedings of the American medical informatics association annual symposium 2018. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18. Basch E, Reeve BB, Mitchell SA, et al. . Development of the National cancer Institute's patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO-CTCAE). J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106:dju244 10.1093/jnci/dju244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, et al. . Development of the patient activation measure (PAM): Conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res 2004;39:1005–26. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Given CW, Given B, Stommel M, et al. . The caregiver reaction assessment (cra) for caregivers to persons with chronic physical and mental impairments. Res Nurs Health 1992;15:271–83. 10.1002/nur.4770150406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nijboer C, Triemstra M, Tempelaar R, et al. . Measuring both negative and positive reactions to giving care to cancer patients: psychometric qualities of the caregiver reaction assessment (cra). Soc Sci Med 1999;48:1259–69. 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00426-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.