Abstract

Purpose

The DANish LIFE course (DANLIFE) cohort is a prospective register-based study set up to investigate the complex life course mechanisms linking childhood adversities to health and well-being in childhood, adolescence and young adulthood including cumulative and synergistic actions and potentially sensitive periods in relation to health outcomes.

Participants

All children born in Denmark in 1980 or thereafter have successively been included in the cohort totalling more than 2.2 million children. To date, the study population has been followed annually in the nationwide Danish registers for an average of 16.8 years with full data coverage in the entire follow-up period. The information is currently updated until 2015.

Findings to date

DANLIFE provides information on a wide range of family-related childhood adversities (eg, parental separation, death of a parent or sibling, economic disadvantage) with important psychosocial implications for health and well-being in childhood, adolescence and young adulthood. Measurement of covariates indicating demographic (eg, age, sex), social (eg, parental education) and health-related factors (eg, birth weight) has also been included from the nationwide registers. In this cohort profile, we provide an overview of the childhood adversities and covariates included in DANLIFE. We also demonstrate that there is a clear social gradient in the exposure to childhood adversities confirming clustering of adverse experiences within individuals.

Future plans

DANLIFE provides a valuable platform for research into early life adversity and opens unique possibilities for testing new research ideas on how childhood adversities affect health across the life course.

Keywords: life course, register, childhood adversities, adverse childhood experience, social disadvantage

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The DANish LIFE course (DANLIFE) cohort provides an unselected data source for investigation of the effects of a wide range of objectively measured childhood adversities on health outcomes in childhood, adolescence and young adulthood.

DANLIFE includes all children born in Denmark in 1980 or thereafter totalling more than 2.2 million children in the latest update in 2015. Such population size allows for the assessment of new research ideas addressing rare outcomes and complex mechanisms such as cumulative and synergistic actions and potentially sensitive periods.

The unique identification number given to all Danish residents enables linkage of information from any Danish register or existing (non-register-based) cohort study to DANLIFE, providing opportunities to answer a wide range of research questions.

The measures of childhood adversities and health-related outcomes in DANLIFE are solely register-based and may be vulnerable to misclassification.

Introduction

The fact that many adulthood diseases have roots in earlier life is by now quite well documented and hardly debatable. The life course approach to studying health, which has increasingly been gaining attention in the past two decades, acknowledges the long-term biological, psychosocial and behavioural processes that operate across the life span, linking earlier life exposures to health in later life.1 These processes are extremely complex and far from being fully elucidated, but a growing amount of evidence suggests that in early life, when the brain and the physiological systems are not fully mature, exposure to psychosocial adversities may be particularly detrimental for future health and developmental trajectories. Advances in neuroscience, molecular biology and epigenetics have put forward an intriguing hypothesis that adverse events experienced early in life, when the human stress response system is still under development, may produce long-lasting alterations in the way the brain and the body respond to stress.2 3 These alterations, which can be traced not only on the behavioural but also on the epigenetic level,4 are, on one hand, an adaptation to a stressful environment; on the other hand, they may have long-lasting costs to future mental health and the normal regulation of the metabolic and cardiovascular systems, leading to physical health consequences.5

Given that childhood may constitute a sensitive period for a whole range of exposures, including the exposure to stress, the timing of these exposures is central to life course epidemiology. Furthermore, researchers in child development have long argued that while exposure to a single risk factor hardly ever causes enduring harm, experience of multiple risk factors often has consequences for health.6 7 Thus, research of adversity needs to account for the accumulation of stressors from different domains as well and across the life span.8 9 The empirical testing of the hypotheses regarding the exact timing of exposures as well as the cumulative and interactive effects of stressors requires large data materials with frequent repeated measures over time. The DANish LIFE course (DANLIFE) cohort is a large-scale repeated-measure dataset established to provide information on how childhood adversities affect health across the life course.

There exist a number of birth cohorts and other longitudinal studies with rich repeated information, which provide a valuable platform for life course research on early life adversities and health.10–13 The DANLIFE cohort is different from the existing datasets in several key ways and thus provides new opportunities within this research area. DANLIFE utilises data from nationwide registers covering all children born in Denmark since 1980. Because the data are exclusively register-based, the DANLIFE sample is unselected, thus solving the problem of selection bias that observational studies are prone to. Furthermore, using the national registers ensures a very large sample size. The population covered by DANLIFE totals more than 2.2 million children. Thus, the cohort provides strong statistical power needed to test hypotheses involving complex interactions.

Using register-only information has its limitation in that the psychosocial measures available are not very detailed. However, as we explain below, due to the unique Civil Registration System (CRS) available in Denmark, it is also possible to link DANLIFE to other existing (non-register-based) studies of Danish participants or invite DANLIFE participants for more assessments. All register-based data on major life events, social adversity and health outcomes are routinely collected and continuously updated for all children included in the cohort. The precise recording of timing of the information in DANLIFE enables the assessment of temporality between exposures, outcomes and covariates as well as identification of potentially critical and sensitive periods of exposure to childhood adversities. The cohort was specifically set up to test hypotheses on complex life course mechanisms including:

Investigating whether specific childhood adversities act independently, cumulatively or synergistically on clinical health outcomes across life stages.

Identifying potentially sensitive periods (eg, infancy, childhood, adolescence, early adulthood) for childhood adversities in relation to health outcomes.

DANLIFE is placed at a secure server at Statistics Denmark. Access to Danish administrative and health registers is granted by Statistics Denmark and The Danish Health Data Authorities. Data are provided for research purposes in an anonymous and secure form.

Cohort description

Study population

All children born in Denmark in 1980 or thereafter to mothers who had a Civil Personal Registration (CPR) number at the time of birth have been identified in the Danish CRS14 and have successively been included in DANLIFE. The CPR number is a unique 10-digit number all Danish residents are given at birth or upon immigration, as are non-resident persons who become members of the Danish Labour Market Supplementary Pension Fund or pay taxes in Denmark.14 The CPR number permits exact linkage on individual level between national administrative, clinical and health research registries in Denmark14 and thus provides an opportunity for country-wide population-based studies on public health matters by covering information such as drug prescriptions, hospitalisations, income and employment15 (figure 1). Some register-based information can have missing data, for example, children of immigrated parents will have missing data on parental education if their parents completed their education abroad. Since the data from CRS provided to DANLIFE are updated annually and include the population on the 1st of January each year, children who are live-born but die or emigrate within the same calendar year are not included in the data from CRS. Children who died or emigrated in their first year of life were instead identified in the Danish Medical Birth Registry (MBR) (n=13 756). MBR includes all children born in Denmark to mothers with residence in Denmark at the time of birth.16 Immigrants not born in Denmark are not included in DANLIFE because no information on childhood adversities is available for immigrants prior to immigration. Valid and continuously updated information on many socioeconomic, demographic and health-related factors from the Danish nationwide registers was provided by Statistics Denmark and the Danish Health Data Authorities to DANLIFE.

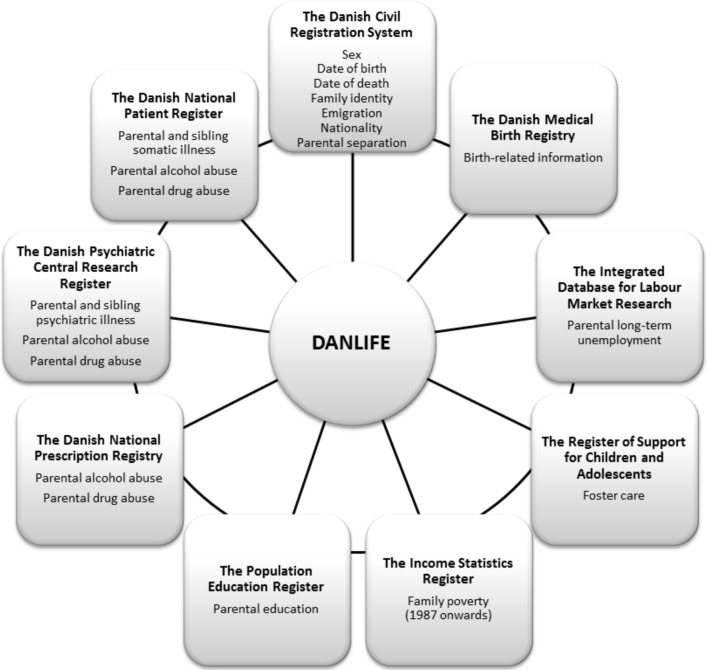

Figure 1.

Nationwide Danish registers linked on individual level in the DANish LIFE course (DANLIFE) cohort using the Civil Personal Registration number and the information they provided to the cohort.

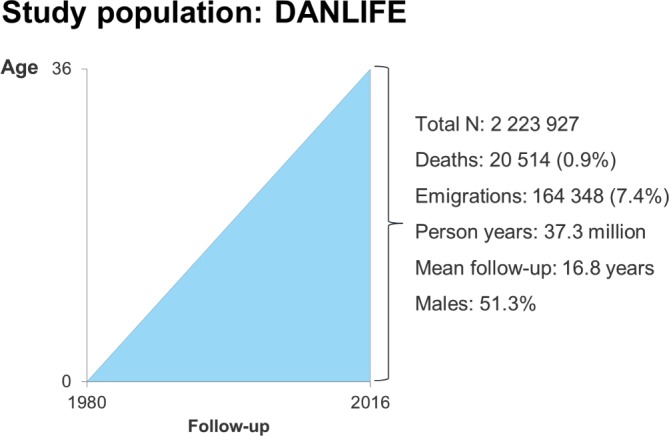

The study participants have been followed until emigration, death or the end of follow-up. The information is currently updated until the 31st of December 2015, but we will continue with annual updates when the data become available. The current version of DANLIFE includes 2 223 927 individuals followed for an average of 16.8 years corresponding to more than 37 million person-years (figure 2). Individuals emigrating during follow-up (n=164 348; 7.4%) are censored at the date of emigration and are not re-entered into the cohort if ever returning to Denmark, since there would be an information gap in the period the person spent outside of Denmark. Censoring on date of death was possible using information from CRS (n=20 514; 0.9%). Studies based on Danish registers do not require informed consent or involvement by the population nor is an ethical approval by the Danish National Committee on Health Research Ethics required.

Figure 2.

Characteristics of the DANish LIFE course (DANLIFE) cohort and follow-up period.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design of this register-based cohort.

Family linkage

The CPR numbers of the parents in DANLIFE have been retrieved from the child’s first year of life from CRS supplemented by information from MBR. The parents registered in CRS are the legal parents, and biological parents can therefore not be distinguished from adoptive parents.14 However, the number of children who are born in Denmark and adopted is approximately 1%.17 The parents registered in MBR are assumed to be the biological parents.16 The CPR numbers of the parents were used to identify siblings as persons linked to the same mother and father and to identify twins as persons born to the same mother on the same day (+/−1 day). The CPR number of the parents can also be used to identify siblings who only share one parent. The linkage to parents and siblings in DANLIFE enables identification of exposure to a range of family-related childhood adversities, such as severe illness in the family. The family linkage also enables identification of family history of specific diseases through linkage to the Danish National Patient Registry.18 Children with missing information on both parents in both CRS and MBR were not included in the DANLIFE cohort (n=3103), since it would be impossible to identify the siblings of these children as well as the exposure to most of the family-related childhood adversities.

Data sources

The registers combined in DANLIFE are updated for research purposes once a year (figure 1). Information comes from nine registers: CRS captures sex, date of birth, date of death, family identifier, emigration, nationality and parental separation;19 MBR captures birth-related information;16 20 the Integrated Database for Labour Market Research captures parental long-term unemployment;21 the Register of Support for Children and Adolescents captures foster care; the Income Statistics Register captures family poverty (only from 1987 and onwards);22 the Population Education Register captures parental education;23 the Danish National Prescription Registry captures drug prescriptions,24 which we use to identify parental alcohol and drug abuse; the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register captures admissions due to psychiatric diagnoses,25 which we use to identify parental and sibling psychiatric illness and parental alcohol and drug abuse; and the Danish National Patient Register captures hospital admissions with diagnose codes,18 which we use to identify parental and sibling somatic illness and parental alcohol and drug abuse.

To date, DANLIFE includes information from the 1st of January 1980 until the 31st of December 2015 and will continue to be updated as children are born and registered. The continuity of the Danish registries provides full data coverage in the entire follow-up period, except for information on family poverty, which is based on the household equivalised disposable income, which was only available from 1987 onwards. Most factors have been specified with an exact date such as date of birth, emigration, death, highest attained education and all somatic and psychiatric diagnoses registered in the National Patient Registry.18 Information on personal income and transfer payments,22 labour market affiliation21 and parental separation14 are registered across a given calendar year, and the timing of these adversities is therefore set to the year of occurrence (table 1). Since the objective of DANLIFE is to enable assessment of the effects of adversities experienced in childhood on health and well-being, we restricted the exposure period to 0–18 years of age. The exposure period can easily be altered to accommodate research projects with alternative objectives.

Table 1.

Definition and timing of the childhood adversities included in the DANish LIFE course (DANLIFE) cohort

| Adversity | Definition | Date |

| Foster care | Being placed in out-of-home care | Date of placement |

| Parental psychiatric illness | A parent’s admission for at least 1 day with an International Classification of Diseases (ICD) version 8 (ICD-8) or version 10 (ICD-10) diagnostic code related to psychiatric illness. ICD-8 codes: psychoses (290–299 except 291); neuroses, personality disorders and other nonpsychotic mental disorders (300–309 except 303–304); and mental retardation (310-315); ICD-10 codes: mental, behavioural and neurodevelopmental disorders (F00–F99 except F10–F19) | Date of diagnosis |

| Parental somatic illness | A parent diagnosed with one of the ICD-8 codes included in the Charlson comorbidity index38 in the period 1980–1993 or the ICD-10 codes included in the updated version of the Charlson comorbidity index39 in the period 1994–2015 | Date of diagnosis |

| Parental death | Death of a parent | Date of death |

| Sibling psychiatric illness | A sibling’s admission for at least 1 day with an ICD-8 or ICD-10 code related to psychiatric illness. ICD-8 codes: psychoses (290–299); neuroses, personality disorders and other nonpsychotic mental disorders (300–309); and mental retardation (310–315); ICD-10 codes: mental, behavioural and neurodevelopmental disorders (F00–F99) | Date of diagnosis |

| Sibling somatic illness | A sibling diagnosed with one of the following somatic illnesses related to mortality in children aged 0–18 years (ICD-8/ICD-10 codes): malignant neoplasm (140–199/C00–C96); congenital anomalies of the heart and circulatory system (746–747/Q20–Q28); congenital anomalies of the nervous system (743/Q00–Q07); cerebral palsy (343–344/G80–G83); epilepsy (345/G40–G41); cardiomyopathy (425/I42–I43); congenital disorders of lipid metabolism (272/E75) | Date of diagnosis |

| Sibling death | Death of a sibling | Date of death |

| Parental alcohol abuse | A parent diagnosed with an illness related to alcohol abuse or receiving a prescription of a drug used in treatment of alcohol addiction. ICD-8 codes: alcoholic psychosis (291); alcoholism (303); alcoholic cirrhosis of the liver (571.09); alcoholic steatosis of the liver (571.10); ICD-10 codes: alcohol psychosis and abuse syndrome (F10); alcoholic polyneuropathy (G62.1); alcoholic cardiomyopathy (I42.6); alcoholic-induced acute (K85.2) and chronic (K86.0) pancreatitis; alcoholic liver disease (K70); alcoholic gastritis (K29.2); Anatomical Theraputic Chemical (ATC) Classification System codes: drugs used in alcohol dependence (N07BB) | Date of diagnosis/prescription |

| Parental drug abuse | A parent diagnosed with an illness related to drug abuse or receiving a prescription of a drug used in treatment of drug addiction. ICD-8 codes: drug dependence (304); ICD-10 codes: opioids (F11); cannabinoids (F12); sedatives/hypnotics (F13); cocaine (F14); other stimulants (F15); hallucinogens (F16); other and multiple drugs (F18–F19); ATC codes: drugs used in opioid dependence (N07BC) | Date of diagnosis/prescription |

| Parental separation | Separation of the parents | Year of separation |

| Parental long-term unemployment | A parent being unemployed for at least 12 months within two consecutive years | First year of unemployment |

| Poverty | Family income below 50% of the median national family income in a given year, in three consecutive years | Third consecutive year of poverty |

Childhood adversities and covariates

The uniqueness of DANLIFE lies within the definition and construction (eg, death of siblings needs to be constructed using a family identifier) of measures of selected childhood adversities with important psychosocial implications for health and well-being in childhood, adolescence and young adulthood. In childhood, the family environment plays a crucial role for development and well-being. At the same time, a straining family environment, and the social circumstances in which it takes place, may be major sources of stress in children.8 26–29 Two aspects of family environment that have been shown to be important sources of stress in children are unstable family dynamics with lack of responsive caregiving2 30 31 and loss or the threat of loss within the family.29 31–33 Material deprivation in the family is also a source of stress in children as it may affect parenting skills and family climate, as well as the availability of social and material resources, such as high-quality housing, proximity of good schools and recreation areas.34–36 The linkage between child, parents and siblings in DANLIFE enables measurement of a range of childhood adversities that are likely to affect the family dynamics and quality of caregiving (ie, parental separation, being placed in foster care, parental psychiatric illness, sibling psychiatric illness and parental alcohol or drug abuse); indicate loss or the threat of loss, within the family (ie, parental somatic illness, sibling somatic illness and death of a parent or a sibling) and material deprivation (ie, family poverty and parental long-term unemployment). Table 1 provides an overview of the adversities included in DANLIFE.

An important and growing field within the life course framework is the assessment of mediation and interaction.1 The following covariates for confounding, mediation and interaction assessment have been incorporated in DANLIFE so far: sex (male, female), age at any given time (based on date of birth), birth order, birth weight (in grams), parental age at any given time (based on date of birth), ethnicity (Danish, non-Danish if at least one parent has a nationality other than Danish) and parental highest attained education at the time of birth (low <9 years, ie, mandatory education in Denmark; middle 10–12 years, ie, youth education and vocational education and high >12 years). In Denmark, ≤9 years of schooling is equivalent to basic education mandatory by law, 10–12 years of schooling is equivalent to high school in the USA and >12 years of schooling is any additional schooling (eg, university). The definitions of the covariates can be altered to accommodate specific research objectives. In principle, the CPR number enables the inclusion of information on exposures, outcomes and covariates from any Danish register or any other study on Danish participants, which has recorded CPR numbers, into the DANLIFE cohort given granted permission from the authorities responsible for data security. An overview of the nationwide registers that have been linked in DANLIFE and which specific adversities and covariates each register has provided information on is shown in figure 1. Information from several registers has been combined to define the adversities representing parental alcohol and drug abuse (table 1 and figure 1).

Findings to date

DANLIFE is a newly established dataset, and no results based on its data have therefore been published to date but several studies investigating the effect of childhood adversities on health outcomes such as cardiovascular disease, type 1 diabetes and all-cause mortality are ongoing. Here, we present findings regarding the prevalence of adversities among Danes and the social gradient in the exposure to adversities. These findings are summarised in table 2. Table 2 gives an overview of the exposure to the specific childhood adversities in the total study population of more than 2.2 million children. Parental separation was the most frequently experienced adversity during follow-up (29%) followed by parental long-term unemployment (25%). In this large study population, several thousand had experienced even the rarest adversities (ie, sibling death and sibling psychiatric illness). Table 2 further shows a clear social gradient in the exposure to childhood adversities in DANLIFE. The proportions of children exposed to the specific childhood adversities are consistently increasing with decreasing levels of maternal education measured at the time of birth. The gradient is strong for the adversities reflecting family poverty, parental unemployment, and parental alcohol and drug abuse. The social gradient is also pronounced for parental separation where as many as 40% of the children born to mothers with a low level of education have experienced separation compared with only 19% of the children born to mothers with a high level of education. The social gradient is evident for all childhood adversities included in the cohort.

Table 2.

Exposure to specific childhood adversities according to maternal educational level

| Adversity | Total | Maternal education*† | ||||||

| High | Middle | Low | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Total | 2 223 927 | 100.0 | 714 718 | 32.1 | 869 775 | 39.1 | 571 161 | 25.7 |

| Foster care | 66 069 | 3.0 | 4120 | 0.6 | 13 087 | 1.5 | 45 936 | 8.0 |

| Parental psychiatric illness | 89 014 | 4.0 | 15 501 | 2.2 | 30 072 | 3.5 | 40 953 | 7.2 |

| Parental somatic illness | 270 529 | 12.2 | 71 529 | 10.0 | 103 317 | 11.9 | 89 314 | 15.6 |

| Parental death | 55 759 | 2.5 | 11 605 | 1.6 | 19 083 | 2.2 | 23 453 | 4.1 |

| Sibling psychiatric illness | 18 213 | 0.8 | 4133 | 0.6 | 6287 | 0.7 | 7294 | 1.3 |

| Sibling somatic illness | 56 911 | 2.6 | 15 793 | 2.2 | 22 170 | 2.5 | 17 694 | 3.1 |

| Sibling death | 10 543 | 0.5 | 2516 | 0.4 | 4001 | 0.5 | 3679 | 0.6 |

| Parental alcohol abuse | 146 186 | 6.6 | 22 798 | 3.2 | 49 422 | 5.7 | 70 640 | 12.4 |

| Parental drug abuse | 40 248 | 1.8 | 4707 | 0.7 | 11 622 | 1.3 | 22 694 | 4.0 |

| Parental separation | 638 879 | 28.7 | 136 615 | 19.1 | 259 465 | 29.8 | 230 359 | 40.3 |

| Parental long-term unemployment | 558 534 | 25.1 | 80 636 | 11.3 | 201 602 | 23.2 | 259 686 | 45.5 |

| Family poverty‡ | 99 457 | 5.4 | 13 655 | 1.9 | 34 421 | 4.0 | 46 338 | 8.1 |

We used strata by maternal education as the majority of Danish children live with their mother (85%).40

*Missing information on maternal education, n=68 273 (3.1%). Immigrated women who completed their education abroad will have missing information on education.

†High: >12 years; middle: 10–12 years; low: ≤9 years.

‡From 1987 onwards, total n=1 846 564.

The accumulation of childhood adversities in DANLIFE is presented in table 3. Almost half of the study population did not experience any childhood adversities during follow-up and almost 10% had experienced three or more adversities. The well-known clustering of social disadvantage within individuals can also be seen in table 3. More than 60% of the children born to mothers with a high level of education at the time of birth have not experienced any adversities during follow-up compared with only 25% of the children born to mothers with a low level of education. Accordingly, only 3.5% of the children born to highly educated mothers have experienced three or more adversities compared with 20% of the children born to mothers with a low educational level. This is also reflected in the average number of adversities experienced during follow-up among children born to mothers with a high (0.5), middle (0.9) and low (1.5) level of education.

Table 3.

Accumulation of childhood adversities according to maternal educational level

| Adversities | Total | Maternal education*† | ||||||

| High | Middle | Low | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Total | 2 223 927 | 100.0 | 714 718 | 32.1 | 869 755 | 39.1 | 571 161 | 25.7 |

| 0 | 1 035 594 | 46.6 | 449 025 | 62.8 | 400 264 | 46.0 | 147 138 | 25.8 |

| 1 | 651 608 | 29.3 | 181 006 | 25.3 | 276 572 | 31.8 | 179 500 | 31.4 |

| 2 | 324 057 | 14.6 | 59 621 | 8.3 | 127 221 | 14.6 | 129 297 | 22.6 |

| 3+ | 212 668 | 9.6 | 25 066 | 3.5 | 65 718 | 7.6 | 115 266 | 20.2 |

| Mean no. adversities | 0.5 | 0.9 | 1.5 | |||||

We used strata by maternal education as the majority of Danish children live with their mother (85%).40

*Missing information on maternal education, n=68 273 (3.1%). Immigrated women who completed their education abroad will have missing information on education.

†High: >12 years; middle: 10–12 years; low: ≤9 years.

Strengths and limitations

The main strengths of DANLIFE include the unselected sample and the large sample size. The unselected sample ensures unbiased estimates of the effects of adversity on clinical outcomes, and the large sample size and linkage to medical registers give the possibility to study very rare health outcomes, including possibilities for interaction analyses, which tend to require a lot of statistical power. Yearly updated information provides higher time resolution than most available birth cohorts and allows for estimation of exposure trajectories (eg, moving in and out of poverty) and rather precise timing of exposures, which is crucial for investigation of critical and sensitive periods. Finally, information about exposures and outcomes that comes from registers is more objective than questionnaire-based data, as they are not subject to recall bias and other types of biases that are associated with self-reporting (eg, participants’ personality affecting their over-reporting of symptoms).37

The DANLIFE sample is still very young, with a maximum age of 36 years, and therefore quite healthy. Even though many diseases will not be manifested until a later age, we still observe more than 20 000 deaths and a considerable number of clinical outcomes such as cardiovascular disease, type 1 diabetes and subtypes of cancer in the DANLIFE sample. Thus, the large sample size provides a unique opportunity to evaluate effects of childhood adversities on clinical health outcomes in early adult life, which is a severely understudied area due to lack of statistical power and few cases in previous life course studies.

On the other hand, defining exposures and outcomes based on registers has important trade-offs. With respect to outcomes, only clinical diagnoses are available for investigation. This for example means that only severe mental health problems resulting in hospital admission will be captured in the data. Similarly, many relevant exposures related to family dynamics and sensitive care cannot be measured using registers. Furthermore, those measures that can be defined via registers are crude and may be vulnerable to misclassification. To illustrate, the effects of parental separation on children’s well-being may be modified by a large number of circumstances, such as the extent to which parents are able to collaborate postdivorce and the shared custody arrangement. It may also be important whether parents enter new relationships once their marriage is dissolved. This information can only to a very limited degree be obtained via registers. As an example of possible misclassification, parental psychiatric illness, which may be severe enough to affect the family functioning, but not severe enough to result in hospitalisation, will not be captured in registers. However, the limitations concerning crude or incomplete measures can be overcome if DANLIFE data are combined with more precise questionnaire-based measures: because the CPR number is available for all participants, it is possible to link DANLIFE to other, non-register-based cohort studies of Danish participants or to invite a subsample of those who are in the DANLIFE cohort for a more detailed assessment. Thus, DANLIFE provides a valuable platform for research into early life adversity and opens a lot of unique possibilities for testing new research ideas.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the researchers in the Psychosocial Epidemiology Research Group at the Department of Public Health, University of Copenhagen, who have been involved in discussing the theoretical framework of the DANLIFE cohort. We thank professor Ulrik Becker at the National Institute of Public Health, University of Southern Denmark, for valuable advice on the use of Danish registers regarding alcohol and drug misuse.

Footnotes

Contributors: JB, ND and NHR were involved in the conception and design of the study. JB and AR were responsible for data management and analyses. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and have critically revised and approved the final version.

Funding: This work was supported by The Innovation Fund Denmark (grant number 5189-00083B) and Helsefonden (grant number 17-B-0102).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Access to DANLIFE is available through collaborative agreements and granted access to the Danish registers by Statistics Denmark and The Danish Health Data Authorities. Please contact Professor Naja Hulvej Rod (nahuro@sund.ku.dk) for further information.

Collaborators: Access to the Danish register data must be granted by Statistics Denmark and The Danish Health Data Authorities and is therefore not open access. Access to the established DANLIFE cohort is available to other investigators through collaborative agreements and a secured access. Please contact Professor Naja Hulvej Rod (nahuro@sund.ku.dk) for further information.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Ben-Shlomo Y, Cooper R, Kuh D. The last two decades of life course epidemiology, and its relevance for research on ageing. Int J Epidemiol 2016;45:973–88. 10.1093/ije/dyw096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ganzel BL, Morris PA. Allostasis and the developing human brain: explicit consideration of implicit models. Dev Psychopathol 2011;23:955–74. 10.1017/S0954579411000447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, et al The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics 2012;129:e232–46. 10.1542/peds.2011-2663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Babenko O, Kovalchuk I, Metz GA. Epigenetic programming of neurodegenerative diseases by an adverse environment. Brain Res 2012;1444:96–111. 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.01.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ellis BJ, Del Giudice M. Beyond allostatic load: rethinking the role of stress in regulating human development. Dev Psychopathol 2014;26:1–20. 10.1017/S0954579413000849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rutter M. Protective factors in children’s responses to stress and disadvantage. Ann Acad Med Singapore 1979;8:324–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rutter M. Stress, coping and development: some issues and some questions. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1981;22:323–56. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1981.tb00560.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Evans GW, Li D, Whipple SS. Cumulative risk and child development. Psychol Bull 2013;139:1342–96. 10.1037/a0031808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y, Lynch J, et al. Life course epidemiology. J Epidemiol Community Health 2003;57:778–83. 10.1136/jech.57.10.778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wadsworth M, Kuh D, Richards M, et al. Cohort Profile: The 1946 National Birth Cohort (MRC National Survey of Health and Development). Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:49–54. 10.1093/ije/dyi201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Power C, Elliott J. Cohort profile: 1958 British birth cohort (National Child Development Study). Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:34–41. 10.1093/ije/dyi183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Elliott J, Shepherd P. Cohort Profile: 1970 British Birth Cohort (BCS70). Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:836–43. 10.1093/ije/dyl174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Connelly R, Platt L. Cohort Profile: UK Millennium Cohort Study (MCS). Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:1719–25. 10.1093/ije/dyu001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish Civil Registration System as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol 2014;29:541–9. 10.1007/s10654-014-9930-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thygesen LC, Ersbøll AK. Danish population-based registers for public health and health-related welfare research: introduction to the supplement. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):8–10. 10.1177/1403494811409654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bliddal M, Broe A, Pottegård A, et al. The Danish Medical Birth Register. Eur J Epidemiol 2018;33:27–36. 10.1007/s10654-018-0356-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Christensen K, Schmidt MM, Vaeth M, et al. Absence of an environmental effect on the recurrence of facial-cleft defects. N Engl J Med 1995;333:161–4. 10.1056/NEJM199507203330305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schmidt M, Schmidt SA, Sandegaard JL, et al. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol 2015;7:449–90. 10.2147/CLEP.S91125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pedersen CB. The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):22–5. 10.1177/1403494810387965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Knudsen LB, Olsen J. The Danish Medical Birth Registry. Dan Med Bull 1998;45:320–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Petersson F, Baadsgaard M, Thygesen LC. Danish registers on personal labour market affiliation. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):95–8. 10.1177/1403494811408483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Baadsgaard M, Quitzau J. Danish registers on personal income and transfer payments. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):103–5. 10.1177/1403494811405098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jensen VM, Rasmussen AW. Danish education registers. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):91–4. 10.1177/1403494810394715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pottegård A, Schmidt SA, Wallach-Kildemoes H, et al. Data Resource Profile: The Danish National Prescription Registry. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:798–798f. 10.1093/ije/dyw213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mors O, Perto GP, Mortensen PB. The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):54–7. 10.1177/1403494810395825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Troxel WM, Matthews KA. What are the costs of marital conflict and dissolution to children’s physical health? Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2004;7:29–57. 10.1023/B:CCFP.0000020191.73542.b0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gottman JM, Katz LF. Effects of marital discord on young children’s peer interaction and health. Dev Psychol 1989;25:373–81. 10.1037/0012-1649.25.3.373 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Evans GW, Kim P. Childhood poverty and health: cumulative risk exposure and stress dysregulation. Psychol Sci 2007;18:953–7. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.02008.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lewandowski LA. Needs of children during the critical illness of a parent or sibling. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am 1992;4:573–85. 10.1016/S0899-5885(18)30605-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tarullo AR, Gunnar MR. Child maltreatment and the developing HPA axis. Horm Behav 2006;50:632–9. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Luecken LJ, Lemery KS. Early caregiving and physiological stress responses. Clin Psychol Rev 2004;24:171–91. 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Luecken LJ, Appelhans BM. Early parental loss and salivary cortisol in young adulthood: the moderating role of family environment. Dev Psychopathol 2006;18:295–308. 10.1017/S0954579406060160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. van Andel HW, Jansen LM, Grietens H, et al. Salivary cortisol: a possible biomarker in evaluating stress and effects of interventions in young foster children? Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2014;23:3–12. 10.1007/s00787-013-0439-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Evans GW, Kim P. Childhood Poverty, Chronic Stress, Self-Regulation, and Coping. Child Dev Perspect 2013;7:43–8. 10.1111/cdep.12013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Miller GE, Chen E, Parker KJ. Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. Psychol Bull 2011;137:959–97. 10.1037/a0024768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Chen E, et al. Childhood socioeconomic status and adult health. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010;1186:37–55. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05334.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Coughlin SS. Recall bias in epidemiologic studies. J Clin Epidemiol 1990;43:87–91. 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90060-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Christensen S, Johansen MB, Christiansen CF, et al. Comparison of Charlson comorbidity index with SAPS and APACHE scores for prediction of mortality following intensive care. Clin Epidemiol 2011;3:203–11. 10.2147/CLEP.S20247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:676–82. 10.1093/aje/kwq433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Publikation: Børn og deres familier. 2018. https://www.dst.dk/da/Statistik/Publikationer/VisPub?cid=31407 (cited 8 Apr 2019).