Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to determine the fatal drowning burden and associated risk factors in Southern Bangladesh.

Settings

The survey was conducted in 39 subdistricts of all 6 districts of the Barisal division, Southern Bangladesh.

Participants

All residents (for a minimum 6 months prior to survey) of the Barisal division, Southern Bangladesh.

Intervention/methods

A cross-sectional, divisionally representative household survey was conducted in all six districts of the Barisal division between September 2016 and February 2017, covering a population of 386 016. Data were collected by face-to-face interview with adult respondents using handheld electronic tablets. International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-v. 10 (ICD-10) Chapter XX: External causes of morbidity and mortality codes for drowning, W65–W74, X36–X39, V90, V92, X71 or X92, were used as the operational definition of a drowning event.

Results

The overall fatal drowning rate in Barisal was 37.9/100 000 population per year (95% CI 31.8 to 43.9). The highest fatal drowning rate was observed among children aged 1–4 years (262.2/100 000/year). Mortality rates among males (48.2/100 000/year) exceeded that for females (27.9/100 000/year). A higher rate of fatal drowning was found in rural (38.9/100 000/year) compared with urban areas (29.3/100 000/year). The results of the multivariable logistic regression identified that the factors significantly associated with fatal drowning were being male (OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.2 to 2.3), aged 1–4 years (OR 3.0, 95% CI 1.4 to 6.4) and residing in a household with four or more children (four or more children OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.1 to 2.9; and five or more children OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.2 to 3.7).

Conclusion

Drowning is a public health problem, especially for children, in the Barisal division of Southern Bangladesh. Male gender, children 1–4 years of age and residing in a household with four or more children were associated with increased risk of fatal drowning events. The Barisal division demands urgent interventions targeted at high-risk groups identified in the survey.

Keywords: drowning, fatal drowning, mortality, injury, risk factor, Bangladesh

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A key strength of this study was the large divisionally representative sample of Barisal division in Bangladesh, to guide contextual implementation of effective interventions.

The study used multiple methods for quality control, of significance are the learnings from use of electronic data capture system with low access to internet.

Limitations included the cross-sectional nature of the study which may have introduced recall bias. Although the proportion of refusals was small (2%), collecting data on reasons for non-participation could have added to the strength of the study.

Under-reporting in overall mortality rates is a concern for children under 5 years and may have contributed to an underestimate of the true mortality in this age group.

Introduction

An estimated 322 149 annual drowning deaths occur globally, making fatal drowning a major global health problem.1 Half of all drowning fatalities occur in people under the age of 25, with children aged between 1 and 4 years being the most vulnerable. More than 90% of drowning incidents take place in low-income and middle-income countries where men, women and children have a higher exposure to the risks associated with open water.2 According to the 2012 WHO Global Health Estimates, the global mortality rate from drowning was 5.2 per 100 000 population, with the highest rate observed in the African region (7.9 per 100 000 population) followed by South-East Asia region (7.4 per 100 000 population).2

In 2005, the first Bangladesh Health and Injury Survey (BHIS) identified drowning as the leading cause of death among children 1–17 years, with approximately 17 000 children dying each year.3 In 2016, the BHIS was carried out for the second time and again drowning was found to be the main cause of injury deaths among children aged 1–4 and 5–9 years. According to the 2016 BHIS, every day 40 children (aged between 0 and 17 years) lost their life due to drowning and this was the highest among all injury fatalities. Among adults (aged 18 years or more), there were 13 deaths from drowning per day and this was the sixth leading cause of injury death in that age category.4 The 2011 Bangladesh Demographic Health Survey found that while the risk of dying from other conditions, such as vaccine preventable communicable diseases, had significantly decreased, fatalities from drowning among children aged 1–4 years rose alarmingly from 19.0% in 2004 to 43.0% in 2011.5

Bangladesh is a highly disaster prone country, ranked sixth in the 2015 World Risk Report.6 It is especially vulnerable to cyclones and frequent flooding which claim many lives each year.7 Since the country is intersected by many rivers, drowning during inland water transport accidents is also common.8

The 2005 BHIS identified that the highest mortality rate due to drowning occurred in the Pirojpur district of Barisal division in Bangladesh.3 Geographically, the Barisal division is located in the central southern region of Bangladesh where several large rivers converge; with a land mass of 13 644.85 km² and a population of 8 147 000. As a low lying, coastal division, Barisal is vulnerable to natural hazards and the effects of climate change. All six districts under this division are regularly affected by water-related hazards.9

Considering these factors, Project Bhasa, a Comprehensive Drowning Reduction Strategy, was designed to reduce fatal drowning and morbidity utilising evidence-based interventions. As part of this initiative, a baseline survey was conducted to determine the burden and context of fatal drowning in the Barisal division of Southern Bangladesh.

Methods

The Bhasa baseline survey was a population-based cross-sectional survey representative to the Barisal division, one of the country’s eight divisions. Geographically, the division is located in the central southern region of Bangladesh where several large rivers converge. The survey was conducted between September 2016 and February 2017 in 39 subdistricts of all six districts (Barguna, Barisal, Bhola, Jhalokathi, Patuakhali and Pirojpur) of the division. The survey covered 95 063 households comprising 386 016 population in the selected subdistricts and used a multistage stratified cluster sampling method. The sampling frame for subdistricts was designed to give a probability of selection proportional to population. Household sampling was conducted using the WHO Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) approach.10

Measures

The operational definition of injury mortality used in this study was in accordance with ICD-10 Chapter XX: External causes of morbidity and mortality, recording intent and mechanism of injury.11 It was defined as, ‘any death occurred due to external harm resulting from a fall, burn, cut, transportation, suffocation, drowning, machine/tool injury, electrocution, animal injury, blunt object injury, poisoning, suicide and violence’. Drowning was described as ‘the process of experiencing respiratory impairment from submersion or immersion in liquid’.12 Drowning deaths were included if the cause was any of the following external cause codes from ICD-10 Chapter XX: External causes of morbidity and mortality: codes W65–W74 (unintentional drowning), X36–X39 (exposure to forces of nature—water related), V90 (drowning or submersion due to accident to watercraft), V92 (drowning and submersion due to accident on board watercraft, without accident to watercraft), X71 (intentional self-harm by drowning and submersion) or X92 (assault by drowning and submersion while in bath tub).11 13

Information on all fatal injuries was collected over a 2-year recall period, from the day of survey. While there is a potential issue of recall bias, previous literature from verbal autopsy reporting cause of death has shown high validity and sensitivity for up to 3 years for causes of death involving injury.14 For all cases of fatal drowning, additional information was collected on potential risk factors. These included sociodemographic characteristics, access to water and pre-event risk factors (eg, location and type of water body, activity of the person prior to drowning, person accompanying prior to drowning, accompanying person’s age), event (eg, time and season of drowning) and postdrowning events (eg, time of rescue, person rescued, action taken after rescue). Information was gathered on knowledge, attitudes and practices related to drowning, drowning prevention and disaster preparedness. Finally, data were also collected on all mortality and all causes of injury mortality.

Data collection and procedures

Data were collected using a pretested structured questionnaire by 50 trained data collectors. Information was gathered from household heads, mothers or any residing adults aged 18 years or older through face-to-face interviews after obtaining written informed consent. Each selected respondent provided information of all household members including children. Each day data collectors visited 25–30 households to collect information. Non-participation due to refusal was 2.0%. To ensure data quality, responsible supervisors randomly re-surveyed 2.0% of the households. An electronic data capturing tool using the REDCap application was used on tablets for data collection.15

Statistical analysis

In this study, to estimate mortality rates, weights were created for the survey data to appropriately adjust for differences in probability of selection and response rates according to age and sex. The probability of selection based on sampling information (number of upazilas that are the subdistricts of a division and number of villages) was calculated and then adjusted to the age and sex distribution from the 2011 Bangladesh Population and Housing Census. All data were analysed using SAS V.9.4 with SAS/STAT V.14.2.

While analysing mortality rates (per 100 000/population) for fatal drowning and for percentage for other variables, the Taylor series method was used. This incorporated the survey weights and the other features of the survey design (stratification by district and cluster sampling of villages). Multivariable logistic regression was used to examine associations between various sociodemographic factors with fatal drowning. Due to electronic data capture and in-built internal validity checks, missing data were minimised with only 1.01%; 977 records were excluded due to missing data. Denominator population data were based on Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, accommodating for a growth rate of 1.37 from the 2011 census.16

Patient and public involvement statement

This is a community-based household survey. Community leaders were consulted for filed implementation of the survey, and their input sought on the tool for capturing contextually relevant data.

Results

A total of 95 063 households were visited, of which 92 616 household representatives (97.4%) completed the survey. Males and females were equally represented among the sampled population (49.1% vs 50.9%) and over one-third (37.2%) of the population were children under 18 years. A total of 4128 deaths were reported in the 2-year recall period, giving an overall mortality rate of 5.3/100 000 population per year (data not shown).

Drowning burden and mortality rates

Drowning accounted for 6.6% of deaths across all age group; however, among children aged 1–4 years, drowning was the cause of more than one-third of all deaths (35.1%). One in 10 deaths among infants (<1 year) and children aged 5–9 years were a result from drowning (data not shown). In the 2-year recall period, there were 285 fatal drownings across all ages, giving an all-age drowning mortality rate of 37.9/100 000 population per year (95% CI 31.8 to 43.9). All fatal drownings were reported to be unintentional. Fatal drowning rates were consistently higher among males compared with females across all ages except among those aged 10–14 years where a higher rate was observed among females. However, this higher rate among girls aged 10–14 years old was not statistically significant.

The highest fatal drowning rates were in children aged 1–4 years at 262.2/100 000 per year (95% CI 216.4 to 308.0) followed by infants (88.6/100 000) then children aged 5–9 years (65.1/100 000). In early adolescence (10–14 years), fatal drowning rates decreased but increased again in early adulthood (18–24 years) and among those aged 60 years and over where higher rates of fatal drownings were observed (table 1).

Table 1.

Drowning deaths and mortality rates by age and sex in the Barisal division, Bangladesh

| Sex | Male | Female | All persons | National rate both sex BHIS 2016* |

|||||||

| Age (years) | Numerator (Denominator) | Rate (per 100 000/year) | 95% CI (LL, UL) |

Numerator (Denominator) | Rate (per 100 000/year) | 95% CI (LL, UL) |

Numerator (Denominator) | Rate (per 100 000/year) | 95% CI (LL, UL) |

Rate (per 100 000/year) | 95% CI (LL–UL) |

| <1 | 7 (3389) | 142.9 | 22.9, 263.0 | 3 (3380) | 34.8 | 0, 81.9 | 10 (6769) | 88.6 | 25.4, 151.9 | 53.3 | 2.8–345.8 |

| 1–4 | 96 (14 147) | 325.3 | 252.6, 398.0 | 74 (14 192) | 199.8 | 143.1, 256.5 | 170 (28 339) | 262.2 | 216.4, 308.0 | 71.7 | 31.4–154.8 |

| 5–9 | 31 (21 454) | 78.7 | 48.9, 108.4 | 21 (20 640) | 51.8 | 25.1, 78.4 | 52 (42 094) | 65.1 | 42.4, 87.9 | 28.1 | 9.0–77.3 |

| 10–14 | 5 (23 085) | 9.3 | 0, 18.8 | 9 (22 765) | 28.2 | 6.7, 49.8 | 14 (45 850) | 18.9 | 7.2, 30.5 | 3.2 | 0.0–36.2 |

| 15–17 | 6 (11 094) | 21.1 | 2.8, 39.3 | 0 (9240) | – | – | 6 (20 334) | 11.2 | 1.5, 20.9 | 5.6 | 0.0–63.5 |

| 18–24 | 8 (17 688) | 24.1 | 0, 52.9 | 6 (24 638) | 10.8 | 1.3, 20.4 | 14 (42 326) | 17.2 | 2.9, 31.5 | – | |

| 25–39 | 6 (41 449) | 5.2 | 0, 10.9 | 1 (49 676) | 1.2 | 0, 3.5 | 7 (91 125) | 3.1 | 0.1, 6.1 | 2.5 | 0.1–16.2 |

| 40–59 | 4 (36 444) | 8.1 | 0, 18.2 | 2 (35 568) | 3.1 | 0, 7.4 | 6 (72 012) | 5.6 | 0.1, 11.1 | 8.6 | 1.9–30.3 |

| 60+ | 5 (20 226) | 22.3 | 3.6, 40.9 | 1 (160 52) | 3.1 | 0, 9.1 | 6 (36 278) | 12.6 | 2.9, 22.2 | 8.8 | 0.5–56.9 |

| Total | 168 (188 976) | 48.2 | 38.9, 57.4 | 117 (196 151) | 27.9 | 21, 34.9 | 285 (385 127) | 37.9 | 31.8, 43.9 | 11.7 | 7.1– 19.0 |

*Rahman A, Chowdhury SM, Mashreky SR, Linnan M, Rahman AKMF. (2016) Report on Bangladesh Health and Injury Survey, DGHS, CIPRB, Dhaka.

BHIS, Bangladesh Health and Injury Survey.

Fatal drowning rates were higher in rural areas compared with urban areas of the subdistrict (38.9/100 000 vs 29.3 per 100 000) and across all age groups except in infancy (<1 year) and early adulthood (18–24 years) where drowning fatality rates were higher in urban areas (table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution rates of fatal drowning by age and region of residence in the Barisal division, Bangladesh

| Age (years) | Rural | Urban* |

| Rate per 100 000 (95% CI) | Rate per 100 000 (95% CI) | |

| <1 (infant)* | 79.8 (13.6 to 145.9) | 160.9 (0.0 to 438.2) |

| 1–4 | 277.2 (225.7 to 328.6) | 135.4 (40.8 to 230.0) |

| 5–9 | 68.9 (43.4 to 94.3) | 31.5 (0.0 to 66.1) |

| 10–14 | 18.9 (6.4 to 31.3) | 18.5 (0.0 to 51.8) |

| 15–17 | 11.5 (0.7 to 22.3) | 8.6 (0.0 to 25.3) |

| 18–24 | 11.0 (3.3 to 18.6) | 65.7 (0.0 to 177.4) |

| 25–39 | 3.5 (0.2 to 6.9) | 0 |

| 40–59 | 6.3 (0.1 to 12.4) | 0 |

| 60+ | 13.9 (3.2 to 24.6) | 0 |

| Total | 38.9 (32.6 to 45.3) | 29.3 (6.5 to 52.1) |

*The event rate for infants and urban areas are very small, reporting very wide confidence interval.

Drowning by distance of water body from households, type of water body, activity, seasonality and time of the day

Across all age categories, about three-quarters of fatal drowning events occurred within 100 metres of the households. However, among adolescents aged 15–17 years and adults aged 40 years and above over 20.0% of drowning deaths occurred at a distance of over two kilometres (data not shown).

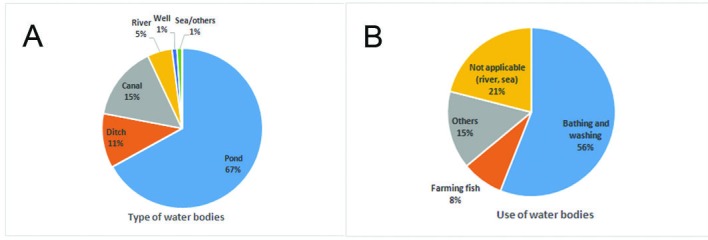

The majority (98.0%) of drowning deaths took place in the community, while less than 1.0% were related to disasters or while using water transportation. Over three-quarters of drowning deaths occurred in ponds and ditches (figure 1A), and over half were in outdoor water bodies primarily used for bathing and washing (56.0%) (figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Distribution of fatal drowning by type of water bodies (A) and their use (B).

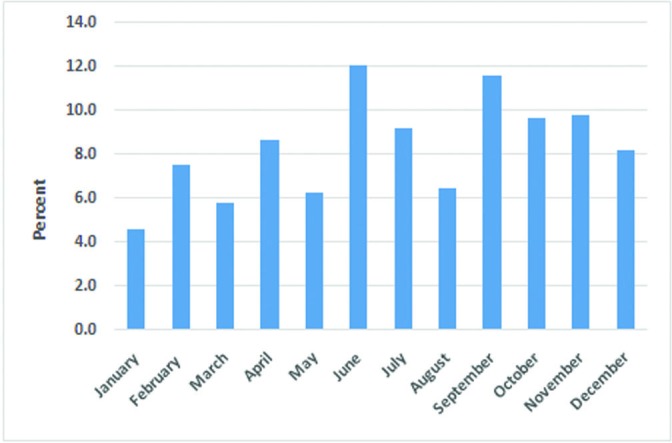

Drowning occurred throughout the year; however, fatalities peaked during the monsoon season particularly in the months of June and September which accounted for nearly one-quarter (23.7%) of all drowning deaths (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of fatal drowning by time of the year in Barisal division, Bangladesh.

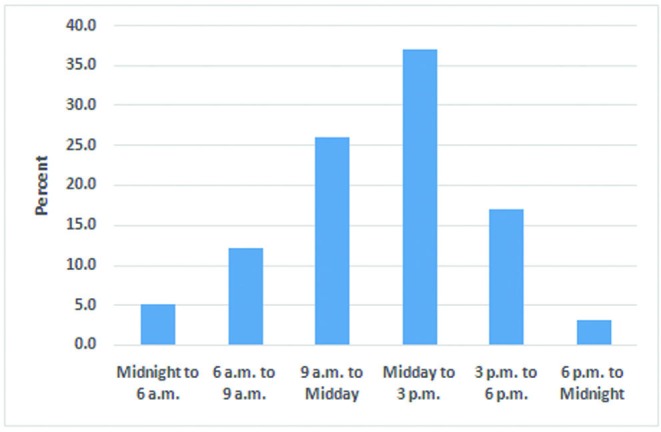

Almost all fatal drownings occurred between the daylight hours of 6 a.m. and 6 p.m., with two-thirds (63.0%) taking place between the hours of 9 a.m. and 3 p.m. (figure 3). Among children aged 1–4 years, most fatal drownings occurred between the hours of 12 p.m. and 4 p.m. (58.0%), which was followed by 8 a.m. to 12 p.m. (31.0%) (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Distribution of fatal drowning by time of the day in Barisal division, Bangladesh.

Person accompanying prior to drowning event

Almost two-thirds (62.3%) of drowned individuals were not accompanied by anyone during the drowning incident, while 15.0% were accompanied by a friend or colleague (data not shown).

Individual involved in rescue

During fatal drownings, neighbours or bystanders (43.0%) were the individuals most often involved in the rescue, followed by mothers (21.2%).

Factors associated with fatal drowning

Univariate analyses for fatal drowning showed that children aged 1–4 years had three times higher odds of fatally drowning compared with those aged under 1 years. Similarly, households with four or more children had almost two times higher odds of experiencing a drowning fatality than households with one child. After adjustment, the factors that remained associated with fatal drowning were age, with children aged 1–4 years at three times higher odds than those aged less than 1 year. Being male also significantly increased the odds of drowning fatalities by almost 70.0%. The number of children in the household was also significantly associated with fatal drowning and increased with increasing number of children (table 3).

Table 3.

Sociodemographic factors associated with drowning mortality

| Characteristic | Univariate | Multivariable | ||||||

| OR | LCL | UCL | P value | OR | LCL | UCL | P value | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 1.7 | 1.3 | 2.3 | 0.0004 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 2.3 | 0.0007 |

| Female | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Age group (years) | ||||||||

| <1 | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 1–4 | 3.0 | 1.4 | 6.3 | <0.0001 | 3.0 | 1.4 | 6.4 | <0.0001 |

| 5–9 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 1.6 | . | 0.7 | 0.3 | 1.5 | |

| 10–14 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.6 | . | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.5 | . |

| 15–17 | 0.1 | 0.04 | 0.4 | . | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.3 | . |

| 18–24 | 0.2 | 0.08 | 0.5 | . | 0.097 | 0.030 | 0.313 | . |

| 25–39 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | . | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.09 | . |

| 40–59 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | . | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.13 | . |

| 60 + | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.4 | . | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | . |

| Maternal education | ||||||||

| None | 1.9 | 0.4 | 8.2 | |||||

| 1–5 years | 2.8 | 0.7 | 11.4 | 0.3372 | . | . | . | . |

| 6–8 years | 2.5 | 0.6 | 10.6 | . | . | . | . | . |

| 9–12 years | 2.1 | 0.5 | 8.8 | . | . | . | . | . |

| 13–17 years | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Wealth quintile | . | . | . | . | . | |||

| Q1 (Lowest) | 1.5 | 0.9 | 2.5 | 0.5147 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 2.2 | 0.8396 |

| Q2 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 2.2 | . | 1.1 | 0.6 | 2.0 | . |

| Q3 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 2.1 | . | 1.2 | 0.7 | 1.9 | . |

| Q4 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 2.1 | . | 1.1 | 0.6 | 2.0 | . |

| Q5 (Highest) | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| No. of children in household* | ||||||||

| 1 | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 2 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 0.6273 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 0.0026 |

| 3 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 1.5 | . | 1.2 | 0.8 | 1.8 | . |

| 4 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 2.1 | . | 1.8 | 1.1 | 2.9 | . |

| 5+ | 1.4 | 0.8 | 2.4 | . | 2.1 | 1.2 | 3.7 | . |

*Number of household with no children was very small to draw plausible inference.

LCL, lower confidence limit; UCL, upper confidence limit.

Discussion

The mortality and morbidity reporting systems in Bangladesh are poor.17 To inform a large-scale drowning prevention strategy, we conducted a cross-sectional household survey to provide otherwise unavailable epidemiological data on drowning in the Barisal division. Our study found a mortality rate from drowning of 37.9 per 100 000 per year across all ages in the Barisal division, which is more than three times greater than the national rate reported in 2016 (11.7/100 000/year).4 The number of water bodies, including rivers, lakes, ponds and ditches in this division is far higher than in other parts of the country. For both males and females, fatal drowning rates were high in infancy, peaked at 1–4 years of age, then fell rapidly through middle childhood and adolescence, and remained relatively low throughout adulthood. This pattern of fatal drowning rates across the age groups in this study is consistent with another recent national survey.4

Previous studies identified nearby ponds, ditches and canals as the most common location of fatal drowning among children in Bangladesh.3 17–20 In the Barisal region, most households are surrounded by water bodies. Similar to previous studies, this study revealed that the majority of childhood drowning deaths occurred in ponds, ditches and canals situated within only 100 metres of their residences. Children were often with other siblings (children) or unaccompanied at the time of drowning. Lack of supervision in younger children is a major risk factor. Attentiveness and continuity are essential characteristics of the hierarchical model of supervision.21 Proximity to the water exacerbates risk; however, among adults, a considerable proportion of drowning fatalities occurred at a distance of two kilometres from their houses. It is possible that these deaths occurred in rivers where individuals were engaged in activities such as fishing or boating.

Drowning deaths in Barisal occurred year-round but most frequently during the monsoon season (June–October); this is similar to findings reported in prior studies.18 22–24 It is also notable that in the dry season (November–December), the fatal drowning rates remained relatively high in Barisal. This is likely because most natural water bodies including those close to households are tidal and are subject to two high tides each day. This can increase the risk of exposure especially among children playing in water bodies. Previous studies have also reported over 90% of fatal drowning events occurred in daylight hours.17 25

Fatal drowning was strongly and significantly associated with sex, with males having over 1.5 times the odds of death from drowning. This may be related to male’s greater propensity for risk-taking behaviours and increased exposure to high-risk situations.26 It may also reflect existing traditional gender roles in Bangladesh, with young boys more likely to be out playing unsupervised, whereas girls would be at home helping with household activities. This points to the need to place specific emphasis on targeting boys within drowning prevention programme. Age was also significantly related to fatal drowning with those in the age group of 1–4 years having the greatest risk of drowning. This age group has consistently been found to be at greater risk of drowning in Bangladesh and other South-East Asian and Western Pacific countries2 18 27 and may be related to challenges to achieve adult supervision, the inability to swim in this age group and other behavioural factors.18 We did not find any significant association between the level of mother’s education and fatal drowning risk. The socioeconomic status of our study population was fairly homogeneous and no associations were reported across the socioeconomic groups. A higher number of children in the household increased the risk of drowning events. Households with four or five children in the family were common place. In these circumstances, parents may find it difficult to adequately supervise all of them. These findings support the need for programmes that can assist families with supervision.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The study was strengthened by steps taken to ensure the data quality of data. Field supervisors were recruited and trained, and they observed 10.0% of interviews conducted by the data collectors. They also checked 10.0% of the collected data, and reinterviewed 2.0% of the households. In addition, field level research officers and managers were appointed to recheck all data for inconsistencies. If inconsistency was detected, the respective data collector was asked to revisit the household to collect correct information.

Another strength was that the study used external cause codes of fatal drowning from the ICD-10 that provided a more representative data on the true burden of fatal drowning. In addition to unintentional external cause of drowning codes, watercraft and flood-related drowning, and intentional self-harm by drowning codes were also included. Studies have suggested to include these later codes (drowning from watercraft, flood related and intentional self-harm) to obtain more representative magnitude of fatal drowning.28 29 Intentional drownings particularly suicides are culturally stigmatised in Bangladesh. Household surveys thus are not the best source of data for determining intent of drowning. However, given the high burden among children, intent has little implications on the study findings.

Given that the mortality burden is highest in children aged under 5 years, it should be noted that under-reporting in overall mortality rates is an issue in this age group because of poor birth/vital registration systems, so our results may have underestimated the true burden. This is likely to affect data on children aged under 1 year to a greater extent. However, given that a 2-year recall period was used in this survey, the fatal drowning rates are likely to be conservative. Although the proportion of refusals was small (2%), collecting data on reasons for non-participation could have added to the strength of the study.

One of the major challenges in this study was to use the electronic data capturing system with an intent to review and manage data as the survey progressed. Each data collector was given a tablet loaded with REDCap application, and a sim was inserted in the device to obtain wireless internet connection. However, in the remote locations, the internet connectivity was very poor and initially the data collectors could not upload their collected data from the site of data collection. To resolve this issue, an offline data collection system was created in the software. Each day after data collection in the afternoon, the data collectors returned to their field office to get a high-quality Wi-Fi connection to upload their data. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first survey using an offline application for electronic data capture (REDcap) in the region. The survey was huge, with over 250 variables collecting information on multiple drowning events in each household. With English and Bangla translations, the screen size of a handheld Android device posed challenge for accuracy in data entry, which was mitigated by division of the survey into multiple sections/tools and optimising the font size. Bilingual presentation was essential, as statistical programmes are primarily compatible with English only.

The environmental context presented issues that needed consideration, for example, access to electricity for charging of devices, access to internet or recharging the power banks. Some of these learnings that have since led to enhanced features within the REDcap application including synchronising of autogenerated identification on an offline application, preventing data loss or the duplication of data. It was due to the success of using electronic data capture and utilising internal validity checks that the high quality and completeness of the dataset was achieved.

The survey was purposively conducted in Barisal division, which is one of the eight divisions of Bangladesh. In previous national injury surveys, the highest drowning mortality rate among children was observed in the Pirojpur district of Barisal division.3 Considering this high rate, the Barisal division was selected for Project Bhasa.

Conclusion

The study findings highlight the very high magnitude of drowning deaths in the Barisal division. Sociodemographic factors including being male, aged 1–4 years and having five or more children in households were associated with increased risk of fatal drowning. The findings further demonstrate that drowning is predominantly a problem that affects children in Bangladesh. The Barisal division demands urgent interventions targeted at high-risk groups identified here. Project Bhasa aims to provide evidence-based interventions, including community daycare for children under 5 years old to ensure adult supervision during day time and the provision of swimming instruction and school water safety education to children aged 5 years and over, to reduce drowning. It is expected that the project will generate knowledge to assist with drowning reduction efforts both nationally and other similar settings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was a part of Project Bhasa—a Comprehensive Drowning Reduction Strategy. We thank Royal National Lifeboat Institution, UK, The George Institute for Global Health, Australia and the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS), Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh for their support in the study. We gratefully acknowledge Professor AHM Enayet Hussain, Additional Director General, DGHS, MoHFW to Chair the National Steering Committee for the Project Bhasa and also for providing all necessary administrative support to accomplish the baseline survey. We also would like to thank Steve Wills and Ashim Kumar Saha for their contribution during data collection.

Footnotes

Contributors: AR participated in the design, implementation and supervision of field work and analysis and wrote the paper. JJ contributed on project design, data analysis and writing of the paper. KB and MJH contributed on project design, implementation, data management and supervision of field work and writing of the paper. DR contributed on project design and writing of the paper. TA and KR were involved in data management and analysis and contributed to the writing of the paper. RI and FR conceived the study and supervised throughout and contributed to the writing of the paper. RI and FR are the guarantors.

Funding: The research was funded by Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI), UK. One of the coauthors of this paper, Dan Ryan, works for the RNLI. He contributed in designing the study and was also involved in writing the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study received ethical approvals from the ethical review committee of the Centre for Injury Prevention and Research, Bangladesh (CIPRB), Bangladesh and the Human Ethics Committee of the University of Sydney, Australia. The ethics approval numbers were CIPRB/ERC/2016/12 and USyd HREC-2016/606, respectively.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1. World Health Organisation, Global Health Estimates 2016: deaths by cause, age, sex, by country and by region, 2000-2016. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organisation, Global report on drowning: preventing a leading killer. Geneva, Switzerland: The World Health Organisation (WHO), 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rahman A, et al. Bangladesh health and injury survey report on children. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS), Ministry of Health & Family Welfare (MOHFW), Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh, Institute of Child & Mother Health (ICMH), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), The Alliance for Safe Children (TASC), 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rahman A, et al. Bangladesh Health and Injury Survey. Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS), Ministry of Health & Family Welfare (MOHFW), Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh, Centre for Injury Prevention and Research, Bangladesh: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. NIPORT, Mitra and Associates, and ICF International Bangladesh demographic and health survey 2011. Maryland, USA: NIPORT, Mitra and Associates, and ICF International: Dhaka, Bangladesh and Calverton, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6. UNU-EHS and Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft World risk report 2015. Berlin: Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft (Alliance Development Works) and United Nations University – Institute for Environment and Human Security (UNU-EHS), 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Department of Disaster Management Bangladesh, Disaster report 2013. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Department of Disaster Management, Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Azad A. Riverine passenger vessel disaster in Bangladesh: options for mitigation and safety. Dhaka, Bangladesh: BRAC University, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9. IWM Policy brief: local level hazard maps for flood, storm, surge and salinity. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Institute of Water Modelling (IWM), 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harris DR, Lemeshow S. Evaluation of the epi survey methodology for estimating relative risk. World Health Stat Q 1991;44:107–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Health Organisation, International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems 10th revision (ICD-10). Geneva, Switzerland: The World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12. van Beeck EF, Branche CM, Szpilman D, et al. A new definition of drowning: towards documentation and prevention of a global public health problem. Bull World Health Organ 2005;83:853–6. doi:/S0042-96862005001100015 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Passmore JW, Smith JO, Clapperton A. True burden of drowning: compiling data to meet the new definition. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot 2007;14:1–3. 10.1080/17457300600935148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Serina P, Riley I, Hernandez B, et al. What is the optimal recall period for verbal autopsies? validation study based on repeat interviews in three populations. Popul Health Metr 2016;14 10.1186/s12963-016-0105-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics Bangladesh statistics 2017. Dhaka: Ministry of Planning, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rahman A, Alonge O, Bhuiyan A-A, et al. Epidemiology of drowning in Bangladesh: an update. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14:488–11. 10.3390/ijerph14050488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rahman A, Mashreky SR, Chowdhury SM, et al. Analysis of the childhood fatal drowning situation in Bangladesh: exploring prevention measures for low-income countries. Inj Prev 2009;15:75–9. 10.1136/ip.2008.020123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ahmed MK, Rahman M, van Ginneken J. Epidemiology of child deaths due to drowning in Matlab, Bangladesh. Int J Epidemiol 1999;28:306–11. 10.1093/ije/28.2.306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hyder AA, Arifeen S, Begum N, et al. Death from drowning: defining a new challenge for child survival in Bangladesh. Inj Control Saf Promot 2003;10:205–10. 10.1076/icsp.10.4.205.16779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Saluja G, Brenner R, Morrongiello BA, et al. The role of supervision in child injury risk: definition, conceptual and measurement issues. Inj Control Saf Promot 2004;11:17–22. 10.1076/icsp.11.1.17.26310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rahman F, Bose S, Linnan M, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of an injury and drowning prevention program in Bangladesh. Pediatrics 2012;130:e1621–8. 10.1542/peds.2012-0757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Linnan M. Child mortality and injury in Asia: survey results and evidence, in Innocenti working paper 2007-06, special series on child injury No. 3. Florence: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, 2007: 64–87. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rahman F, Andersson R, L S. Health impact of injuries: a population-based epidemiological investigation in a local community of Bangladesh. J Safety Res 1998;29:213–22. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hossain M, Mani KKC, Sidik SM, et al. Socio-Demographic, environmental and caring risk factors for childhood drowning deaths in Bangladesh. BMC Pediatr 2015;15:114 10.1186/s12887-015-0431-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Croft JL, Button C. Interacting factors associated with adult male drowning in New Zealand. PLoS One 2015;10:e0130545 10.1371/journal.pone.0130545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yang L, Nong Q-Q, Li C-L, et al. Risk factors for childhood drowning in rural regions of a developing country: a case-control study. Inj Prev 2007;13:178–82. 10.1136/ip.2006.013409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Peden AE, Franklin RC, Mahony AJ, et al. Using a retrospective cross-sectional study to analyse unintentional fatal drowning in Australia: ICD-10 coding-based methodologies verses actual deaths. BMJ Open 2017;7:e019407 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cenderadewi M, Franklin RC, Peden AE, et al. Pattern of intentional drowning mortality: a total population retrospective cohort study in Australia, 2006-2014. BMC Public Health 2019;19:207 10.1186/s12889-019-6476-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.