Abstract

Introduction

The recommendations of most health organisations encourage mothers to keep exclusive breast feeding during the first 6 months and combining breast feeding with complementary feeding at least during the first and second years, due to the numerous immunologic, cognitive developmental and motor skill benefits that breast feeding confers. Although the influence of breast feeding on motor development during childhood has been studied, the findings are inconsistent, and some studies have even reported no effect. This manuscript presents a protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis, with the aim of reviewing the relationship between breast feeding and motor skill development in children in terms of duration, exclusivity or non-exclusivity of breast feeding.

Methods and analysis

The search will be conducted using Medline (via PubMed), EMBASE, Web of Science and Cochrane Library from inception to December 2019. Observational studies (cross-sectional and follow-up studies) written in English or Spanish that investigate the association between breast feeding and motor development in children will be included. This systematic review and meta-analysis protocol follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols. The Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies and The Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for longitudinal studies will be used to assess the quality of included studies. The effect of breast feeding on motor skill development will be calculated as the primary outcome. Subgroup analyses will be carried out based on the characteristics of motor skill development and the population included.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval is not required because the data used will be obtained from published studies, and there will be no concerns about privacy. The findings from this study will be relevant information regarding the association of breast feeding with motor development in children and could be used encourage to improve breastfeeding rates. The results will be published in a peer-reviewed journal.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42018093706.

Keywords: breastfeeding, motor development, motor skills, children

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This review will present a comprehensive and standardised methodology, according to an established framework, to identify relevant studies that analyse the effect of breast feeding on motor skills.

Analysis of different sources of heterogeneity and the assessment of risk of bias of the included studies will be performed independently by two researchers.

To identify studies that aim to determine the association between breast feeding and motor development, an exhaustive literature search will be carried out.

This study could be limited by the quality of available studies, insufficient methodological rigour and statistical heterogeneity.

Different methods used for measuring breast feeding and motor development from observational studies may be another limitation to the quality of evidence of this study.

Introduction

The first 2 years of a child’s life is a critical period for health, growth and development, all of which are affected by nutritional status. It is well documented that breast feeding provides many important health benefits to children and mothers and is considered the gold standard in infant feeding.1 2

The WHO recommends exclusive breast feeding for the first 6 months of life as an ideal feed and continuation of breast feeding for at least the first and second years, which is also supported by many health organisations.1–6 However, the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition differs in the recommendation of the age when complementary feed should be included because of the risk of food allergies.7 The World Health Assembly, as part of its Global Strategy for the Feeding of Infants and Young Children, encouraged member States to promote exclusive breast feeding for 6 months as a global public health recommendation, which provides many benefits to babies, reduces the risk of diseases and helps to promote good physical and cognitive growth.8 9

However, the rates of breast feeding at 6 months remain low in Europe, and even in countries where initial rates are high, there is a marked decrease by the sixth month.10 11 Early cessation of breast feeding and the introduction of solids before 4 months could have considerable adverse effects on children and women’s health.12–15 Therefore, it is important to elucidate what are the reasons behind the failure to achieve the recommendations, and there is a need for greater efforts to disseminate the benefits of breast feeding and to create a social environment that could favour it.

Although infant development is a process that is influenced by several factors, breast feeding in the first months of life is a key determinant for optimal growth and adequate cognitive and motor development. Additionally, breast feeding provides quality nutrient improvement (higher proportion of unsaturated fatty acids), prevents gastrointestinal infection and decreases the risk of diseases later in life, such as allergies, asthma, obesity and celiac disease.2 3 7 9 12 16–19

Thus, motor development and cognitive function represent indicators of overall development during the first years. Motor development allows the acquisition of skills that will contribute to a child’s full participation in activities, avoiding sedentary behaviours, and will help to establish a direct and active relationship with the environment.20 21Although consistent evidence of the positive effects of extended breast feeding on cognitive function has been reported,22 few studies have focused on motor development. The relationship between motor development and breast feeding is difficult to analyse because incomplete control for confounders is reported in the current literature, even when various assessments of motor milestones are considered across studies. To date, no clear associations between the duration of breastfeeding and motor development have been reported.23–26

The purpose of this study protocol was to provide a clear methodology to review the effects of breastfeeding practices on motor development in children in terms of duration and exclusive or non-exclusive breast feeding.

Objective

The aim of this protocol study was to present an objective and transparent methodology to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to increase knowledge and understanding of the associations between the duration and exclusivity of breast feeding and motor development in children aged 0–10 years.

Methods and analysis

The methodology of this protocol was reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses Protocols.27 The ‘Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE): a Proposal for Reporting’,28 the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) and the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 29 will be used to report and guide the review methods.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria for study selection

Studies will be retrieved from the literature by searching for studies that measure the effects of breastfeeding duration and type (exclusivity, even if it is little, or no exclusive breast feeding), and report any type of measure of motor development. To be included, studies will be required to meet the following criteria: (1) children aged 0–10 years; (2) exposure, breast feeding in terms of duration and type (exclusivity or non-exclusivity) and any reported type of measure; (3) motor development outcome, measured using standardised tests; and (4) studies written in English or Spanish.

Studies will be excluded when: (1) they include infants born in multiple pregnancies, with congenital infections or special circumstances requiring intensive care or hospitalisation during the neonatal period; (2) they include children with mental disorders or any detected delay in communication, cognition or motor skills; (3) breast milk has been supplemented, (4) they are multiple publications derived from a single study; and (5) they do not adjust for confounding variates such as socioeconomic status and home environment.

Search methods for the identification of studies

Search strategy

The literature search will be conducted in Medline(via PubMed), EMBASE (via Scopus), Web of Science and Cochrane Library from inception to December 2019. Searches for unpublished studies will be conducted at OPEN GRAY, ProQuest dissertations & Thesis Global, Theseo, Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (NDLTD) and Google Scholar. A search of ClinicalTrials.gov and EudraCT clinical trial records will also be conducted. The searches will be reviewed immediately prior to the final analysis in order to identify further potential studies. Study records will be managed using the Mendeley reference manager.

The following search terms will be combined: breastfeeding, feeding, ‘exclusive breastfeeding’, breastfed, ‘breast suckling’, suckling, ‘motor skill’, ‘psychomotor performance’, ‘motor development’, ‘psychomotor development’, ‘development milestones’, children, child, infant, childhood (table 1). Previous reviews and meta-analyses, as well as the reference lists of the selected studies, will be screened to complete the literature search.

Table 1.

Search strategy for Medline database

| Breastfeeding OR feeding OR ‘exclusive breastfeeding’ OR breastfed OR ‘breast suckling’ OR ‘suckling’ |

AND | ‘motor skills’ OR ‘psychomotor performance’ OR ‘motor development’ OR ‘psychomotor development’ OR ‘motor development milestones’ |

AND | children OR child OR infant OR childhood |

Selection of studies and data extraction

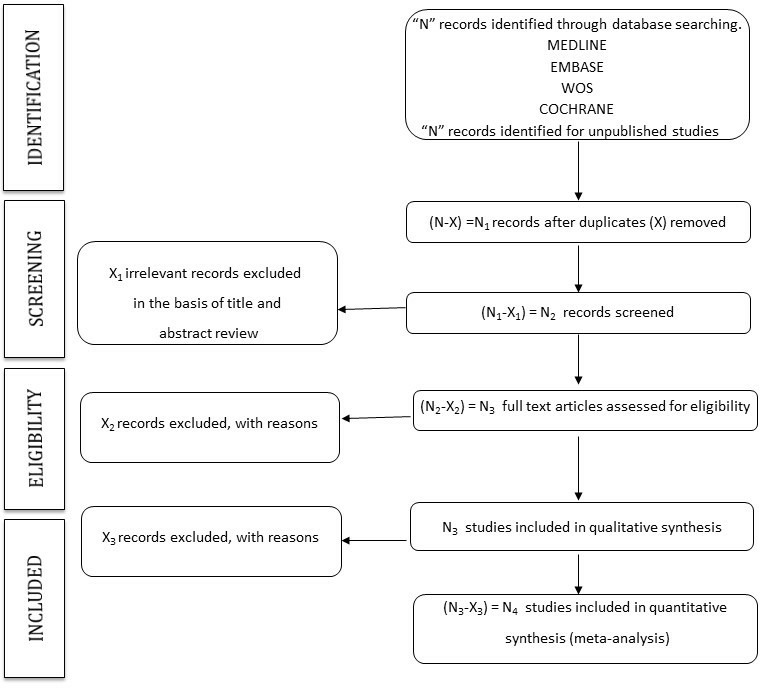

Two researchers will screen all relevant titles and abstracts of the retrieved publications to identify eligible studies. Inclusion and exclusion criteria will be applied to full texts to identify all potentially eligible articles. Inconsistencies in data collection will be solved by consensus. A third reviewer will be consulted when disagreements persist. The process of identifying, screening and including/excluding articles will be illustrated using the PRISMA27 flowchart (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram of identification, screening, eligibility and inclusion of studies. WoS, Web of Science.

Finally, information about the main characteristics of the identified studies will be extracted, including the following data: (1) first author’s name; (2) publication year; (3) country; (4) study design; (5) characteristics of the study population (sample size, age of children at evaluation, gender and number of participants in each group); (6) breastfeeding category (as defined in table 2) and (7) test used for assessment of motor development (table 2). The authors of the included studies will be contacted to request for any missing data.

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review and/or meta-analysis

| Reference | Country | Study design | Population | Breast feeding | MD outcome | |||

| Sample size | Sample age | Categories | n | Tool | Measurement | |||

| First author′s name and year of publication | Country | Design of the study | Number of participants | Age of participants (years) | Duration: periods of exclusive breast feeding/any breast feeding | Number of participants in each breastfeeding category | Instrument used to measure MD | Mean value (SD) |

MD, motor development.

Assessment of risk of bias

Two independent researchers will be blinded to the authors, titles and years of publication of the included studies to evaluate the risk of bias of each included study. The Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies from The Joanna Briggs Institute will be used.30 This tool evaluates the risk of bias according to eight items that could be scored as ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘unclear’ or ‘not applicable’.

The Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale31 will be used to assess the risk of bias of longitudinal studies, including case–control and cohort studies. This tool evaluates the risk of bias according to eight items, which could be grouped in three categories: selection, comparability and exposure or outcome (for case–control and cohort studies, respectively). Each study can be awarded one star for each item within the selection and exposure categories and a maximum of two stars in the comparability category.

Any disagreements over the assessment of quality will be solved by consensus. A third researcher will be consulted if a consensus is not reached.

Statistical analysis

After data extraction, the reviewers will determine whether meta-analysis is possible. At least four studies addressing the association between breast feeding and motor development will be required in order to conduct the meta-analysis. If meta-analysis is possible, STATA V.15 software will be used. The standardised mean difference will be calculated for each study reporting the association between breastfeeding category and motor development using Cohen’s d index.32 To compute the pooled effect size estimates with 95% CIs fixed-effects models33 will be used in the case of no heterogeneity; otherwise, random-effects models34 35 will be used. We will compare the level of motor development in children who have been exclusively breast fed or breast fed for any length of time, as a reference group, with the motor development of those who have never been breast fed. If possible, a comparison between children breast fed for at least 6 months and children breast fed for less than 6 months will also be carried out.

We also will provide further information on the main confounders for our research. Some confounders we will require in order to get full points of the quality assessment of the published studies are social class, mother’s and father’s education level, maternal age, home stimulation and maternal smoking during pregnancy.

Heterogeneity will be assessed by computing the I2 statistic.36 The values of I2 will be considered as follows: 0%–40% might not be important, 30%–60% may represent moderate heterogeneity, 50%–90% may represent substantial heterogeneity and 75%–100% represents considerable heterogeneity.

Linear meta-analysis regression models will be used to explore whether covariates could be associated with the magnitude of the effect and could explain the observed statistical heterogeneity.36 Finally, publication bias will be evaluated using a funnel plot according to the method proposed by Sterne et al.37 When a meta-analysis is not feasible, we will perform a narrative synthesis.

Subgroup analysis and metaregression

If enough studies are available, subgroup analysis will be conducted. Several meta-regressions will be performed on study and sample characteristics including the type of motor development assessment (ie, gross or fine motor), gender, age of study participants, birth weight, breastfeeding classification (never, less than 6 months or more than 6 months) and aspects related to motor. If possible, the method of breast milk feeding will be investigated by subgroup analysis. Furthermore, the design and risk of bias scores of the studies will be considered for additional subgroup analysis. Additional potential moderating variables may be identified after reviewing the literature.

Sensitivity analysis

We will perform sensitivity analysis by removing studies one by one from the main analysis to assess the robustness of the findings.

Patient and public involvement

Existing databases will be used for the purpose of this study. Patients and the public will not be involved in the design of this study. This review will assess the effect of breast feeding on motor developmental outcomes in infants. Insights provided by this study could be used in clinical practice to ameliorate outcomes, specifically, motor development of children in the population.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to present an objective and transparent methodology to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis investigating whether the duration of breast feeding is associated with motor development.

Many studies have examined whether breast feeding in early life, a critical phase of development, could affect later cognitive function and motor development in children.20–22 Infant development is a complex process that encompasses several factors allowing the acquisition of skills that will contribute to the child’s full participation in activities and help to establish a direct relationship with the environment.20

Motor function is an accepted indicator of development during the first years of life.38–40 It directly contributes to and reflects the relationship that the child establishes with the physical and social environments. In addition, motor development plays an important role in other areas of development, such as physical growth and cardiorespiratory fitness, the latter being a powerful and effective indicator of cardiovascular health.41–43 Poor motor development performance may incline children towards activity avoidance and sedentary behaviours, which are linked to increased risk of chronic disease in adulthood.44

There is considerable evidence about the long-term and short-term benefits of breast feeding for infant health.16–19 However, no consensus has been reached about the effects of breast feeding on motor development, and the results and conclusions of existing studies are controversial.21 25 26 The complexity of child development makes it difficult to evaluate these effects, and certain aspects of infant development are influenced by psychosocial and socioeconomic factors, which could contribute to some of the observed differences. The scientific evidence regarding the benefits of breast feeding in terms of motor development outcomes is weak, and the strength of this association is controversial because most studies lack adequate control for potential confounders. Furthermore, previous studies have measured infant development using different standardised tests.

Potential limitations of this research could include publication bias, information bias, inclusion of articles in English and Spanish only, analysis of cross-sectional studies as this does not allow a causal association to be evaluated (breast feeding always precedes motor development), poor statistical analysis and inadequate reporting of methods and findings of the primary studies. To overcome these limitations, the systematic review and meta-analysis will be conducted and reported by two independent reviewers, and a third researcher will be consulted if inconsistencies exist in data collection or consensus is not reached. However, despite these strategies, it is not possible to ensure the lack of risk of bias. Furthermore, existing guidelines, the MOOSE statement, PRISMA and Cochrane Collaboration Handbook recommendations will be followed.

To summarise, we will carry out a systematic review and meta-analysis with the objective of reviewing existing literature on the relationship between breast feeding and motor development. Despite the fact that some aspects of motor development appear to be controversial, if this study confirms the positive effects of breastfeeding on motor skill development, it could encourage greater interest in breastfeeding within the areas of public and child health.

The lack of evidence on the effect of breast feeding and motor skill development highlights the need for guidelines or recommendations based on rigorous and updated reviews summarising the available scientific evidence, to be used in daily practice in order to improve the quality and effectiveness of interventions. The findings of this review could lead to an improvement in the health status and development of children worldwide.

Ethics and dissemination

The data included in this project will be provided by the original studies; therefore, ethical approval and informed consent of patients will not be required.

This protocol provides a clear and structured procedure to extract relevant information on the association of breast feeding with motor skills. This study will have clinical and public health implications, because it could provide support for recommendations on breast feeding, which might help to prevent low rates of breast feeding and early abandonment. Suggestions for future research will be made according to the findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis, and evidence-based recommendations to improve breastfeeding rates will be offered. Finally, longitudinal studies will be needed to confirm if the duration effect of breast feeding is better associated with children’s motor development.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: BN-P and MH-L designed the study and were the main coordinators of the study. BN-P was the principal investigator and guarantor. DPP-C, CA-B, CB-M, VM-V and BN-P conducted the study. MH-L, DPP-C and VM-V gave statistical and epidemiological support. MH-L wrote the article with the support of CB-M, VM-V and BN-P. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study has been funded by FEDER funds.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. World Health Organization/UNICEF Global strategy for infant and young child feeding. Geneva: WHO, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kramer MS, Kakuma R, Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group . Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev 2012;47(6 Suppl). 10.1002/14651858.CD003517.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization Infant and young child feeding. Geneva: WHO, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Organización Panamericana de la Salud Principios de Orientación para La Alimentación complementaria del niño amamantado. Washington DC: PAHO, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kleinman RE, Greer FR. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition : Complementary feeding. pediatric nutrition. 7th edn Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2014: 123. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Infant Feeding Guidelines From birth to 12 months, 2015. Available: www.gov.wales [Accessed 28 May 2018].

- 7. Fewtrell M, Bronsky J, Campoy C, et al. Complementary feeding: a position paper by the European Society for paediatric gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition (ESPGHAN) Committee on nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2017;64:119–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization 65ª Asamblea Mundial de la Salud. plan de aplicación integral sobre nutrición materna, del lactante Y del niño pequeño. OMS, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vestergaard M, Obel C, Henriksen TB, et al. Duration of breastfeeding and developmental milestones during the latter half of infancy. Acta Paediatr 1999;88:1327–32. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1999.tb01045.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tasas de inicio y duración de la Lactancia Materna en España y otros países Comité de Lactancia Materna de la Asociación Española de Pediatría. Lactancia Materna en cifras, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rius JM, Ortuño J, Rivas C, et al. Factores asociados al abandono precoz de la lactancia materna en Una región del este de España. Anales de Pediatría 2014;80:6–15. 10.1016/j.anpedi.2013.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smith HA, Becker GE, Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group . Early additional food and fluids for healthy breastfed full-term infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;96 10.1002/14651858.CD006462.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chowdhury R, Sinha B, Sankar MJ, et al. Breastfeeding and maternal health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr 2015;104(Suppl 1):96–113. 10.1111/apa.13102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. European Food Safety Authority Panel on dietetic products NAD: scientific opinion on the appropriate age for introduction of complementary feeding of infants. Eur Food Safet Authority J 2009;7. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Quasen W, Fenton TR, Friel JK. Age of introduction of first complementary feeding for infants: a systematic review. BMC Pediatr 2015;107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Horta BL, Victoria CG. Short-Term effects of breastfeeding a systematic review of benefits of breastfeeding on diarrhoea and pneumonia mortality. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Horta BL, Victoria CG. Long-Term effects of breastfeeding: a systematic review. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Umer A, Hamilton C, Edwards RA, et al. Association between breastfeeding and childhood cardiovascular disease risk factors. Matern Child Health J 2019;23:228–39. 10.1007/s10995-018-2641-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Horta BL, de Lima NP. Breastfeeding and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Diab Rep 2019;19:1 10.1007/s11892-019-1121-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pollitt E, Caycho T. Desarrollo motor como indicador del desarrollo infantil durante Los primeros DOS años de vida. Revista de Psicología 2010;28:381–409. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Michels KA, Ghassabian A, Mumford SL, et al. Breastfeeding and motor development in term and preterm infants in a longitudinal US cohort. Am J Clin Nutr 2017;106:1456–62. 10.3945/ajcn.116.144279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Anderson JW, Johnstone BM, Remley DT. Breast-Feeding and cognitive development: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 1999;70:525–35. 10.1093/ajcn/70.4.525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thorsdottir I, Gunnarsdottir I, Kvaran MA, et al. Maternal body mass index, duration of exclusive breastfeeding and children's developmental status at the age of 6 years. Eur J Clin Nutr 2005;59:426–31. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chiu W-C, Liao H-F, Chang P-J, et al. Duration of breast feeding and risk of developmental delay in Taiwanese children: a nationwide birth cohort study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2011;25:519–27. 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2011.01236.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sacker A, Quigley MA, Kelly YJ. Breastfeeding and developmental delay: findings from the millennium cohort study. Pediatrics 2006;118:e682–9. 10.1542/peds.2005-3141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dee DL, Li R, Lee L-C, et al. Associations between breastfeeding practices and young children's language and motor skill development. Pediatrics 2007;119(Suppl 1):S92–S98. 10.1542/peds.2006-2089N [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group.. JAMA 2000;283:2008–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org. John Wiley & Sons, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, et al. Chapter 7: systematic reviews of etiology and risk. in: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer′s manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017. Available: https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/

- 31. Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of Nonrandomised studies in Metaanalyses. Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lipsey M, Wilson D. Practical meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Leonard T, Duffy JC. A Bayesian fixed effects analysis of the Mantel-Haenszel model applied to meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:2295–312. 10.1002/sim.1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. DerSimonian R, Kacker R. Random-effects model for meta-analysis of clinical trials: an update. Contemp Clin Trials 2007;28:105–14. 10.1016/j.cct.2006.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, et al. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Method 2010;1:97–111. 10.1002/jrsm.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–58. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sterne JAC, Egger M, Smith GD. Systematic reviews in health care: investigating and dealing with publication and other biases in meta-analysis. BMJ 2001;323:101–5. 10.1136/bmj.323.7304.101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rigby MJ, Köhler LI, Blair ME, et al. Child health indicators for Europe: a priority for a caring Society. Eur J Public Health 2003;13(3 Suppl):38–46. 10.1093/eurpub/13.suppl_1.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Köhler L, Rigby M. Indicators of children's development: considerations when constructing a set of national child health indicators for the European Union. Child Care Health Dev 2003;29:551–8. 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2003.00375.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. The WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study (MGRS) Rationale, planning, and implementation. Available: http://www.who.int/childgrowth/mgrs/fnu/en/index.html [Accessed 15 Jun 2018].

- 41. Artero EG, Ortega FB, España-Romero V, et al. Longer breastfeeding is associated with increased lower body explosive strength during adolescence. J Nutr 2010;140:1989–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ortega FB, Ruiz JR, Castillo MJ, et al. Physical fitness in childhood and adolescence: a powerful marker of health. Int J Obes 2008;32:1–11. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kodama S, Saito K, Tanaka S, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a quantitative predictor of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in healthy men and women: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2009;301:2024–35. 10.1001/jama.2009.681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lucas BR, Elliott EJ, Coggan S, et al. Interventions to improve gross motor performance in children with neurodevelopmental disorders: a meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr 2016;16:193 10.1186/s12887-016-0731-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.