Abstract

Objective:

To asses laboratory syphilis testing policies and practices among laboratories in the Americas.

Methods:

Laboratory directors or designees from PAHO member countries were invited to participate in a structured, electronically-delivered survey between March and August, 2014. Data on syphilis tests, algorithms, and quality control (QC) practices were analyzed, focusing on laboratories receiving specimens from antenatal clinics (ANCs).

Results:

Surveys were completed by 69 laboratories representing 30 (86%) countries. Participating laboratories included 36 (52%) national or regional reference labs and 33 (48%) lower-level laboratories. Most (94%) were public sector facilities and 71% reported existence of a national algorithm for syphilis testing in pregnancy, usually involving both treponemal and non-treponemal testing (72%). Less than half (41%) used rapid syphilis tests (RSTs); and only seven laboratories representing five countries reported RSTs were included in the national algorithm for pregnant women. Most (83%) laboratories serving ANCs reported using some type of QC system; 68% of laboratories reported participation in external QC. Only 36% of laboratories reported data to national/local surveillance. Half of all laboratories serving ANC settings reported a stockout of one or more essential supplies during the previous year (median duration, 30 days).

Conclusion:

Updating laboratory algorithms, improving testing standards, integrating data into existing surveillance, and improved procurement and distribution of commodities may be needed to ensure elimination of MTCT of syphilis in the Americas.

Keywords: Americas region, Antenatal care, Congenital syphilis, Rapid testing, Syphilis testing

1. Background

Syphilis infection during pregnancy is often devastating, resulting in severe adverse pregnancy outcomes in more than half of untreated cases [1]. Adverse perinatal outcomes caused by maternal syphilis infection can be prevented through the screening of pregnant women and by providing prompt treatment for those testing positive [2,3]. Furthermore, syphilis screening and treatment is recognized as one of the most highly cost-effective public health interventions [4], recommended as part of essential antenatal care (ANC) globally [5]. Despite this, preventable congenital syphilis infections continue to occur because pregnant women—especially those who are poor or living in rural settings—are often not screened according to national guidelines [6–8]. The most commonly used serologic screening tests for syphilis require specialized reagents and equipment and trained technicians—a laboratory capacity typically unavailable outside larger hospital or reference laboratories in most low- and middle-income countries [9]. However, globally, many pregnant women receive ANC at lower-level facilities without such laboratory capacity [6–8]. To date, little has been reported in the Americas region regarding the current state of laboratory-based syphilis testing, including the types of tests available, algorithms used, or testing quality.

Mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of syphilis is a significant public health concern worldwide, including in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). In 2008, WHO estimated that, globally, 250 000 infants were born with congenital syphilis [10]. In the same year, more than one-third of the estimated 106 500 pregnant women infected with syphilis in LAC countries were not appropriately treated, resulting in approximately 33 000 adverse pregnancy outcomes [10,11]. In 2010, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) member countries approved the Strategy and Plan for Action for this first regional initiative supporting dual elimination, including country-level commitment to reducing incidence of congenital syphilis to 0.5 cases or less (including stillbirths) per 1000 live births [12]. Reaching the congenital syphilis elimination goals requires countries to achieve programmatic targets of routine syphilis screening (target, 95% of all pregnancies) and treatment (target, 95% treatment of women testing positive) [11,13]. Regional PAHO progress reports have documented consistent increases in regional syphilis testing coverage: by 2014, at least nine of the 35 PAHO member states had reported data suggesting achievement of program elimination targets for both syphilis and HIV [14]. Nonetheless, several countries have continued to lag on coverage of syphilis screening during pregnancy [14], indicating that reaching the ANC testing coverage targets continues to be difficult for many countries. New diagnostics, such as point-of-care (treponemal) rapid syphilis tests (RSTs), may be more practical and effective than traditional diagnostics in ANC settings where rapid treatment is critical [6,15].

The aim of the present survey study was to assess the syphilis testing practices of laboratories in PAHO member countries to understand the syphilis testing algorithms, types of diagnostic tests, and testing practices and standards currently applied by laboratories in countries within the region of the Americas.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Survey recruitment, design, and administration

A descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted among countries in the Americas to explore syphilis laboratory testing practices in reference centers and clinical settings where syphilis testing typically occurs. Laboratory directors were contacted by e-mail and invited to participate in the survey based on an established contact list with PAHO support. The sampling goal of the study was to at least include the national or regional reference laboratory for each country and, if possible, lower-level laboratories that conducted syphilis testing. There was no limit to the number of participating laboratories per country.

A structured questionnaire was developed by a panel of technical laboratory and program experts from PAHO Headquarters and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and was pilot tested by three laboratory directors in charge of syphilis testing to assure its utility, validity, and reliability. The final questionnaire consisted of the following sections: respondents’ positions; type of laboratory; syphilis testing practices, including use of RSTs; barriers to implementation of RSTs; syphilis testing algorithms used; test volume and turn-around times; number of staff available to perform syphilis testing; training of staff; procurement, distribution, stockouts, and funding; other quality assurance (QA) and quality control (QC) procedures, including external QA; participation in national, regional, or local surveillance systems; and perceived needs to improve syphilis testing. In this survey, an RST was defined as a finger-prick, whole blood syphilis test that could be performed onsite at a clinical encounter by a trained health provider who may not be a trained laboratory technician and/or specialist. Respondents were informed that the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) should not be considered an RST. Laboratory-based tests discussed included nontreponemal tests (RPR and venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test) and treponemal tests (chemiluminescence immunoassays, enzyme immunoassay [EIA], fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption [FTA-ABS], Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay, Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay [TPPA]). Classification of LAC sub-regions (Central America, Caribbean, Andean, and Southern Cone) was made in the manner of previous PAHO reports [16].

2.2. Survey administration and statistical analysis

The survey was administered electronically between March and August, 2014, using SurveyMonkey (Palo Alto, CA, USA) via an online web link. Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Descriptive analyses were performed to determine proportions and percentage of responses between national or regional reference laboratories and local, municipal, district, or hospital laboratories (i.e. lower-level laboratories) overall and by subregions. Frequencies of laboratory characteristics, syphilis test types, and testing algorithms were calculated for all laboratories and by laboratory type (national/regional or lower-level laboratory). Subanalyses of barriers to RST implementation and stockouts of testing supplies were conducted only for laboratories receiving specimens from ANC settings and/or pregnant women.

3. Results

A total of 69 laboratorians from 30 (86%) of the 35 PAHO member states completed the survey (Table 1). Participating institutions were fairly equally distributed between larger national or regional reference laboratories (n = 36, 52%) and lower-level or local laboratories (n = 33, 48%) comprised of maternity hospital laboratories, private or public hospitals, and other primary or local health clinics. Most (94%) participating laboratories were public. Of the participating laboratories, 54 (78%) reported receiving specimens for syphilis testing from ANCs.

Table 1.

| Variables | All | North | Central | Caribbean | Andean | Southern Cone |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of eligible countries | 35 | 2 | 8 | 15 | 5 | 5 |

| Response rate | 30 (86) | 2 (100) | 8 (100) | 10 (67) | 5 (100) | 5 (100) |

| Number of participating laboratories | 69 | 2 | 22 | 15 | 16 | 14 |

| Type of facility | 69 | 2 | 22 | 15 | 16 | 14 |

| National/Regional Reference lab | 36 (52) | 2 (100) | 12 (55) | 9 (60) | 7 (38) | 6 (43) |

| District/Local/Hospital lab | 33 (48) | 0 (0) | 10 (45) | 6 (40) | 9 (62) | 8 (57) |

| Public laboratory | 65 (94) | 2 (100) | 20 (91) | 14 (93) | 16 (100) | 13 (93) |

| Private laboratoryc | 3 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (9) | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 (7) |

| Participants’ job title | 69 | 2 | 22 | 15 | 16 | 14 |

| Laboratory Supervisor/Manager | 31 (45) | 2 (100) | 7 (32) | 8 (53) | 8 (50) | 6 (43) |

| Laboratory Technologist | 26 (38) | 0 (0) | 12 (55) | 3 (20) | 6 (37) | 5 (36) |

| Researcher | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Program Manager/Coordinator | 11 (16) | 0 (0) | 3 (13) | 3 (20) | 2 (13) | 3 (21) |

Values are given as number (percentage).

Based on reference of PAHO’s list of regional countries, Mexico was included in Central, and Brazil included in Southern Cone [14].

Missing = 1.

3.1. Types and use of syphilis tests and testing algorithms applied

The most common non-treponemal test used was the RPR, reported by 62% of laboratories (Table 2); 25 (39%) laboratories (46% of national/regional; 32% of lower-level) reported using only the RPR for non-treponemal testing, 20 (31%) used only the VDRL test for non-treponemal testing (30% of national/regional; 32% of lower-level laboratories), and 14 (22%) performed both RPR and VDRL. Four (6%) did not conduct any non-treponemal syphilis testing. For treponemal serological tests, FTA-ABS was the most commonly used single test by both national/regional (47%) and lower-level (33%) laboratories. Twenty-two laboratories (32%; 25% of national/regional and 39% of lower-level) reported that they used no laboratory-based treponemal test, although four of these reported using an RST.

Table 2.

Types of syphilis tests among various laboratories.a

| Type of laboratory | Region | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of test | All (n = 69) | National/Regional (n = 36) | Lower-level (n = 33) | North (n = 2) | Central (n = 22) | Caribbean (n = 15) | Andean (n = 16) | Southern Cone (n = 14) |

| Non-treponemal test (n = 64)b | ||||||||

| RPR only | 25 (39) | 15 (46) | 10 (32) | 1 (50) | 8 (44) | 9 (60) | 7 (47) | 0 (0) |

| VDRL only | 20 (31) | 10 (30) | 10 (32) | 0 (0) | 7 (39) | 2 (13) | 2 (13) | 9 (64) |

| Both | 14 (22) | 4 (12) | 10 (32) | 0 (0) | 29 (11) | 3 (20) | 5 (33) | 4 (29) |

| None | 4 (6) | 3 (9) | 1 (4) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | 1 (7) | 1 (7) |

| Otherc | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Laboratory-based treponemal test (n = 69) | ||||||||

| FTA-ABS only | 11 (16) | 5 (14) | 6 (18) | 0 (0) | 4 (18) | 1 (6) | 3 (19) | 3 (22) |

| TPPA only | 5 (7) | 4 (11) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 3 (18) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) |

| TPHA only | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (7) |

| EIA only | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 3 (9) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (7) |

| CIA only | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| None | 22 (32) | 9 (25) | 13 (39) | 0 (0) | 10 (44) | 6 (42) | 5 (30) | 1 (7) |

| Multiple treponemal tests | 25 (36) | 18 (50) | 7 (22) | 2 (100) | 4 (18) | 4 (28) | 7 (45) | 8 (57) |

| Rapid treponemal test (n =54) | ||||||||

| Overall | ||||||||

| Yes | 28 (41) | 16 (44) | 12 (36) | 1 (50) | 9 (41) | 2 (13) | 8 (50) | 8 (57) |

| No | 41 (49) | 20 (56) | 21 (64) | 1 (50) | 13 (49) | 13 (87) | 8 (50) | 6 (43) |

| ANC settings | ||||||||

| Yes | 25 (36) | 13 (36) | 12 (36) | 0 (0) | 9 (41) | 2 (13) | 7 (44) | 7 (50) |

| No | 29 (64) | 23 (64) | 21 (64) | 2 (100) | 13 (59) | 13 (87) | 9 (56) | 7 (50) |

Abbreviations: ANC, antenatal care; CIA, chemiluminescence immunoassays; EIA, enzyme immunoassay; FTA-ABS, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption; RPR, rapid plasma reagin; TPHA, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination; TPPA, Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay; VDRL, venereal disease research laboratory.

Values are given as number (percentage).

Missing = 5.

One laboratory reported using Unheated Serum Reagent.

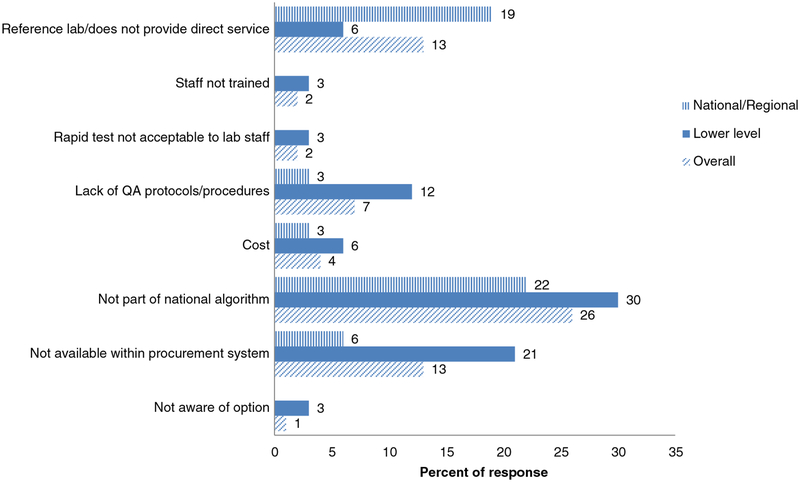

Of the 69 reporting laboratories, less than half (41%) reported using an RST. This was marginally lower compared with laboratories providing testing for ANCs, of which 46% reported using an RST. Use of RSTs was slightly less common among lower-level laboratories (36%) than national/regional laboratories (44%). Among the subregions, the Caribbean had the lowest use of RSTs (13%) and the Southern Cone had the highest (57%). The reported reasons for laboratories not using RSTs varied (Fig. 1), with approximately one-fourth (26%) of the respondents indicating that this was because RSTs were not included in their national algorithm. Other reasons reported were that the tests were not included in the procurement system (13%) and that the institutions were national/reference laboratories that did not provide direct services to patients (13%). When asked about acceptable settings for RST implementation, the majority (59%) of respondents thought mobile outreach programs for at-risk populations was an acceptable setting, followed by ANCs (46%), HIV clinics (49%), sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinics (51%), and primary healthcare clinics (46%). All of the 25 laboratories conducting RSTs in ANC clinics reported that the test was conducted by trained laboratory personnel; however, only 3% of lower-level facilities using RSTs reported that the test was also performed by trained health providers.

Fig. 1.

Reasons for not using rapid syphilis tests reported by laboratories. Note: Rapid tests were not performed by 41 institutions, including 20 national/regional laboratories and 21 lower-level laboratories.

Overall, 71% (49) of respondents, representing laboratories from all 30 participating countries reported the existence of a recommended national algorithm for syphilis testing in pregnant women (Table 3). For 13% of laboratories, respondents reported that there was no such national algorithm; for the remaining 16%, respondents were unaware of whether a national algorithm existed for pregnant women. Only seven laboratories representing five countries reported their syphilis testing algorithm for ANC clinics included an RST (five laboratories used only an RST, one used an RST with reactive tests confirmed by a non-treponemal test, and one used a treponemal test confirmed by an RST).

Table 3.

Syphilis testing algorithms used for pregnant women reported by all laboratories serving antenatal clinics (ANC), HIV programs (HIV), sexually transmitted infection/genitourinary medicine programs (STI).a

| Reported syphilis testing algorithms | ANC (n = 54) | HIV (n = 47) | STI (n = 53) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RPR or VDRL with ALL tests followed by a laboratory-based treponemal test (e.g. TPHA, TPPA, FTA-ABS, EIA, CIA) | 5 (9) | 1 (2) | 2 (4) |

| RPR or VDRL with REACTIVE tests followed by a laboratory-based treponemal testing (e.g. TPHA, TPPA, FTA-ABS, EIA, CIA) | 28 (52) | 5 (11) | 5 (9) |

| RPR or VDRL with reactive tests followed by a rapid treponemal test | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 4 (8) |

| RPR or VDRL only | 2 (4) | 26 (55) | 26 (49) |

| Laboratory-based treponemal test (TPPA, FTA-ABS, EIA, CIA) with reactive tests followed by an RPR or VDRL | 4 (7) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Rapid treponemal test with reactive tests followed by RPR or VDRL | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Laboratory-based treponemal test only (e.g. TPHA, TPPA, FTA-ABS, EIA, CIA) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) |

| Rapid treponemal test only | 5 (9) | 6 (13) | 8 (15) |

| Other | 4 (7) | 2 (4) | 1 (2) |

| No algorithm or don’t know | 4 (7) | 3 (6) | 5 (9) |

Abbreviations: CIA, chemiluminescence immunoassays; EIA, enzyme immunoassay; FTA-ABS, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption; RPR, rapid plasma reagin; TPHA, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination; TPPA, Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay; VDRL, venereal disease research laboratory.

Values are given as number (percentage).

When asked which types of clinical programs their laboratory supported, 78% (81% of national/regional; 76% of lower-level) reported receiving samples from ANC programs. Additionally, 77% received samples from STI programs, 68% from HIV programs, and 45% from other primary healthcare clinics. The most common algorithm used for ANC specimens (52%) was a non-treponemal screening test with reactive tests confirmed by a laboratory-based treponemal test (Table 3). Approximately half (46%) of laboratories serving ANC programs used RSTs in some capacity (45% of national/regional; 48% of lower-level). Fifty-five percent of laboratories serving HIV programs and 49% of laboratories serving STI programs, compared with 4% of laboratories serving ANC programs, used only RPR or VDRL tests (i.e. non-treponemal tests without confirmatory testing).

3.2. Quality of syphilis testing and service integration

Respondents reported a median number of five laboratory staff (range, 0–30) who performed syphilis testing (any type) at their facility; and all 69 laboratories reported that the health personnel performing the tests had received training in syphilis testing. Linking syphilis testing with HIV testing in training programs was reported by 34% of all laboratories and by 39% of those who processed specimens from ANC programs.

Overall, 80% of laboratories reported using some sort of a standard QA/QC procedure, including 83% of laboratories serving ANC clinics; 92% of national/regional laboratories and 67% of lower-level laboratories reported they had QA/QC programs. Most laboratories (81%) performed daily serologic testing using controls (87% of laboratories serving ANCs). Somewhat fewer laboratories (68%; 83% of national/regional; 52% of lower-level) reported participation in an external QA program at least annually. Less than half (49%) reported conducting routine on-site observations of laboratory testing performed in the laboratories. Only 13 countries (out of 30) reported having national proficiency testing programs.

Of the 69 participating laboratories, 48% could provide syphilis testing results within a day, whereas 4% of surveyed laboratories required more than seven days. Among these, 2% were laboratories receiving samples from ANC clinics (3% of national/regional; no lower-level). The 54 laboratories receiving samples from ANC clinics reported that they tested a median of 327 samples (range, 1–43 000) per month (national/regional laboratories median, 238; range, 3–43 000; lower-level laboratories median, 550; range, 1–40 000). The turn-around times for test results were relatively rapid (median, 12 hours; range, 1–168 hours), with only one institution reporting that testing required more than seven days after receipt of the sample. For surveillance reporting, 36% of laboratories reported data to a national, state, or provincial communicable disease or maternal and child health surveillance program (including HIV). When asked about funding sources, 43% of laboratories reported receiving funding from a national STI program or integrated STI/HIV program in their countries, whereas 29% were funded by local provincial programs and 26% by a national HIV program.

Overall, half of all laboratories receiving specimens from ANC settings reported a stockout of one or more of the essential supplies needed for syphilis testing during the previous year (Table 4). During the 12 months preceding the survey, at least one stockout was reported by 55% of laboratories performing the VDRL test, 46% of laboratories performing EIA, and 30% of the laboratories conducting the RPR test. Additionally, 26% of laboratories conducting RPR tests reported stockouts of the RPR cards. Other essential supplies often unavailable were pipette tips (14%), gloves (17%), dressing gowns (13%), and glass syringes. Of note, there were many instances of missing data (i.e. no response to questions about stockouts), therefore, the actual rates may have been much higher. For example, among respondent laboratories conducting the RPR test, 10 out of 14 (71%) experienced shortage of RPR reagents, 6 out of 9 (67%) for VDRL reagents, and 6 out of 8 (75%) for EIA reagents.

Table 4.

Proportion of laboratories supporting antenatal services (n = 54) with stockouts of re-agents or supplies during the previous year.a

| Type of reagent or supply | Stockout | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Don’t know/not reported | |

| Reagent | |||

| RPR (n = 33) | 10 (30) | 4 (12) | 19 (58) |

| VDRL (n = 11) | 6 (55) | 3 (27) | 2 (18) |

| TPPA (n = 13) | 3 (23) | 3 (23) | 7 (54) |

| TPHA (n = 17) | 3 (18) | 3 (18) | 11 (64) |

| FTA-ABS (n = 24) | 5 (21) | 1 (4) | 18 (75) |

| EIA (n = 13) | 6 (46) | 2 (15) | 5 (39) |

| CIA (n = 2) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) |

| Rapid treponemalb (n = 25) | 5 (20) | 2 (8) | 18 (72) |

| Supplies | |||

| RPR cards (n = 33) | 8 (24) | 23 (70) | 2 (6) |

| Pipettes (n = 54) | 7 (13) | 44 (81) | 3 (6) |

| Gloves (n = 54) | 9 (17) | 43 (80) | 2 (3) |

| Other (n = 54) | 5 (9) | 35 (65) | 14 (26) |

| At least one item stockout (n = 54) | 27 (50) | 27 (50) | 0 (0) |

Abbreviations: CIA, chemiluminescence immunoassays; EIA, enzyme immunoassay; FTA-ABS, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption; RPR, rapid plasma reagin; TPHA, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination; TPPA, Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay; VDRL, venereal disease research laboratory.

Values are given as number (percentage).

Test kits or buffer.

4. Discussion

The results of this survey of syphilis testing policies and practices among laboratories in the Americas region included data from 30 (86%) member states. Some areas of adequate capacity were identified: all 30 countries reported having national or regional reference laboratory capacity for syphilis testing. Additionally, at least one laboratory from each of the 30 reporting countries indicated the existence of a national algorithm for syphilis testing in ANC services. All responding laboratories had available staff trained in syphilis testing and most reported familiarity with basic QC strategies (e.g. use of standard operating procedures and daily controls). The turn-around times reported by the laboratories tended to be short.

The survey results also identified several service gaps and areas of concern. Less than half of the laboratories used RSTs, some to confirm positive non-treponemal test results, but most (including lower-level clinics where RSTs are most useful) within a traditional testing algorithm (non-treponemal test followed by a laboratory-based treponemal confirmatory test). Further, a handful of national or regional laboratories were using either a treponemal or a non-treponemal test alone, limiting the diagnostic accuracy of their syphilis test results. Additionally, of the laboratories using laboratory-based treponemal tests, many continued to use the FTA-ABS test despite the more cost-effective, less subjective, and higher-throughput consuming alternative tests available (e.g. TPPA, EIAs).

Relatively few laboratories serving lower-level health facilities were using RSTs in ANC settings, despite these greatly simplifying procedures and improving services in such settings. Most laboratories reported that testing was performed primarily by laboratory staff and not by health providers. The WHO promotes a qualitative non-treponemal screening test with confirmatory rapid treponemal tests as an efficient strategy in ANC clinics connected to laboratories [17]. In ANC settings without laboratories, a rapid treponemal screening test performed by a health provider could allow syphilis-infected women to be identified and a first dose of penicillin to be administered at the clinic visit, thus ensuring prompt treatment of the fetus [17]. In these cases, sending out a blood sample to a laboratory for a non-treponemal test would support the syphilis diagnosis and the provision of additional treatment for the woman and her partner. This approach would be more cost-effective and have a higher efficacy in protecting the fetus against adverse outcomes [18] while minimizing the risks of syphilis complications for both the patient and her sexual partner [19].

The most commonly reported reason for the lack of RST use was that tests were not included in national algorithms, suggesting an opportunity for updating national and/or regional guidance [20]. Additional reasons included RSTs not yet forming part of the procurement systems and QA protocols not having been developed; these barriers can all be addressed through national programs. Very few respondents indicated that these tests were unacceptable or that cost was prohibitive.

Although all laboratories reported using some type of QA strategy, most were primarily focused on basic QC (e.g. using daily controls and standard operating procedures) and training. Additionally, half of all laboratories reported a stockout (average 30 days) of at least one essential item required for syphilis testing during the previous year, suggesting that several country-level procurement systems are inadequate. Among the essential items reported as unavailable were pipettes, gloves, and RPR cards—all of which are basic items. Given these findings, PAHO is currently working with partners to explore potential means for regional support around QA and procurement systems. This may entail partnering with other agencies, e.g. the WHO/PAHO Collaborating Centre at CDC on external quality control of syphilis testing or with Brazil on south-to-south technical support [21].

The present study has some limitations. Although there was a high response rate among PAHO member states, many of the reporting laboratories were national or regional reference laboratories and their responses may not reflect the experiences of laboratories providing services at lower-level health facilities where ANC services are typically offered. Further, the participating lower-level laboratories may not be representative of similar laboratories in their countries. Moreover, the survey respondents (laboratory staff) may not have been familiar with details regarding specific questions on program issues (e.g. turnaround times for test results or whether other health providers offered syphilis testing) or national policy (e.g. the algorithms reported may not be the actual algorithms used in the national strategies). Despite these limitations, this is the first situational analysis addressing syphilis testing practices in the Americas, providing important data on the current syphilis testing practices and perceived needs of the region’s laboratories.

These survey results should encourage countries to work with PAHO and its partners in the areas identified as gaps, such as ensuring quality of testing through external QA or other strategies and procurement of essential supplies to help limit stockouts and reduce program costs. In addition, it is hoped that these results will lead to more in-depth study in areas such as operational research on the causes of stockouts and on how specific program changes (e.g. adoption of new algorithms, use of RSTs, bulk procurement options, decentralization of services, task shifting) actually affect the coverage of syphilis screening and treatment in ANC and other clinical services. Such field studies, even if conducted by only one or a few countries, could provide better evidence of benefit to other countries in the region.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the participating laboratories for providing information through the survey, and staff of the ministries of health of the region and PAHO country offices for their support. Special thanks to Jorge Mathieu (PAHO-Washington, DC) who assisted in tool design and data collection. FP is funded through a secondment to PAHO from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Gomez GB, Kamb ML, Newman LM, Mark J, Broutet N, Hawkes SJ. Untreated maternal syphilis and adverse outcomes of pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ 2013;91(3):217–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Blencowe H, Cousens S, Kamb M, Berman S, Lawn JE. Lives Saved Tool supplement: detection and treatment of syphilis in pregnancy to reduce syphilis-related stillbirths and neonatal mortality. BMC Public Health 2011;11(Suppl. 3):S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hawkes S, Matin N, Broutet N, Low N. Effectiveness of interventions to improve screening for syphilis in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2011;11(9):684–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kahn JG, Jiwani A, Gomez GB, Hawkes SJ, Chesson HW, Broutet N, et al. The cost and cost-effectiveness of scaling up screening and treatment of syphilis in pregnancy: a model. PLoS One 2014;9(1):e87510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hossain M, Broutet N, Hawkes S. The elimination of congenital syphilis: a comparison of the proposed World Health Organization action plan for the elimination of congenital syphilis with existing national maternal and congenital syphilis policies. Sex Transm Dis 2007;34(Suppl. 7):S22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].García PJ, Cárcamo CP, Chiappe M, Valderrama M, La Rosa S, Holmes KK, et al. Rapid syphilis tests as catalysts for health systems strengthening: a case study from Peru. PLoS One 2013;8:e66905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Peeling RW, Mabey D, Fitzgerald DW, Watson-Jones D. Avoiding HIV and dying of syphilis. Lancet 2004;364:1561–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sánchez-Gómez A, Grijalva MJ, Silva-Aycaguer LC, Tamayo S, Yumiseva CA, Costales JA, et al. HIV and syphilis infection in pregnant women in Ecuador: prevalence and characteristics of antenatal care. Sex Transm Infect 2014;90(1):70–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mabey D, Sollis KA, Kelly HA, Benzaken AS, Bitarakwate E, Changalucha J, et al. Point-of-care tests to strengthen health systems and save newborn lives: the case of syphilis. PLoS Med 2012;9(6):e1001233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Newman L, Kamb M, Hawkes S, Gomez G, Say L, Seuc A, et al. Global estimates of syphilis in pregnancy and associated adverse outcomes: analysis of multinational antenatal surveillance data. PLoS Med 2013;10(2):e1001396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Organizacion Panamericana de la Salud. Iniciativa regional para la eliminacion de la transmission maternoinfantil del VIH y de la sifilis congenital en America Latina y el Caribe: documento conceptual. Montevideo: CLAP/MR; 2009. http://www.unicef.org/lac/Documento_Conceptual_-_Eliminacion_de_la_transmision_maternoinfantil_del_VIH_y_de_la_sifilis_congenita(2).pdf. [In Spanish]. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Pan American Health Organization. Strategy and plan of action for the elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and congenital syphilis 50th Directing Council, 62nd Session of the Regional Committee. CD50.R12. Washington, DC: PAHO; 2010. http://new.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2010/CD50.R12-e.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Pan American Health Organization. 2010 Situation analysis: elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV/congenital syphilis. Washington, DC: PAHO; 2011. http://www.paho.org/clap/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=165:2010-situation-analysis-elimination-of-mother-to-child-transmission-hiv%2Fcongenital-syphilis&Itemid=234&lang=es. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Pan American Health Organization. 2012 Progress report: elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and congenital syphilis in the Americas. Washington, DC: PAHO; 2013. http://www.paho.org/hq./index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_download&gid=21836&Itemid=270. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kay NS, Peeling RW, Mabey DC. State of the art syphilis diagnostics: rapid point-of-care tests. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2014;1:63–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Pan American Health Organization. Health situation in the Americas: basic indicators, 2014. Washington, DC: PAHO; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sexually Transmitted Diseases Diagnostics Initiative, TDR, UNICEF/UNDP/World Bank/World Health Organization. The use of rapid syphilis tests. Geneva: WHO; 2006. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/rtis/TDR_SDI_06_1/en/. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Martinez G, Mainero L, Serruya S, Duran P. Gestational syphilis and stillbirth in Latin America and the Caribbean. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2015;128(3):241–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Galvao TF, Silva MT, Serruya SJ, Newman LM, Klausner JD, Pereira MG, et al. Safety of benzathine penicillin for preventing congenital syphilis: a systematic review. PLoS One 2013;8:e56463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Perez F, Hoover K, Juarez S, Salamanca R, Ramos G, Karem K, et al. Informing policy and program decision for scaling up syphilis and HIV testing through a Joint Technical Mission (#WP164). Program and Abstracts of the 2014 STD Prevention Conference, June 9–12, 2014, Atlanta, GA; 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/stdconference/2014/2014-std-prevention-conference-abstracts.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Benzaken AS, Bazzo ML, Galban E, Pinto IC, Nogueira CL, Golfetto L, et al. External quality assurance with dried tube specimens (DTS) for point-of-care syphilis and HIV tests: experience in an indigenous populations screening programme in the Brazilian Amazon. Sex Transm Infect 2014;90(1):14–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]