Abstract

Context

Overtraining syndrome (OTS) and related conditions cause decreased training performance and fatigue through an imbalance among training volume, nutrition, and recovery time. No definitive biochemical markers of OTS currently exist.

Objective

To compare muscular, hormonal, and inflammatory parameters among OTS-affected athletes, healthy athletes, and sedentary controls.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Laboratory.

Patients or Other Participants

Fifty-one men aged 18 to 50 years (14 OTS-affected athletes [OTS group], 25 healthy athletes [ATL group], and 12 healthy sedentary participants [NCS group]), with a body mass index of 20 to 30.0 kg/m2 (sedentary) or 20 to 33.0 kg/m2 (athletes), recruited through social media. All 39 athletes performed both endurance and resistance sports.

Main Outcome Measure(s)

We measured total testosterone, estradiol, insulin-like growth factor 1, thyroid-stimulating hormone, free thyronine, total and fractioned catecholamines and metanephrines, lactate, ferritin, creatinine, creatine kinase, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, lipid profile, hemogram, and testosterone : estradiol, testosterone : cortisol, neutrophil : lymphocyte, platelet: lymphocyte, and catecholamine : metanephrine ratios. Each parameter was statistically analyzed through 3-group comparisons, and whenever P < .05, pairwise comparisons were performed (OTS × ATL, OTS × NCS, and ATL × NCS).

Results

Neutrophils and testosterone were lower in the OTS group than in the ATL group but similar between the OTS and NCS groups. Creatine kinase, lactate, estradiol, total catecholamines, and dopamine were higher in the OTS group than in the ATL and NCS groups, whereas the testosterone : estradiol ratio was lower, even after adjusting for all variables. Lymphocytes were lower in the ATL group than in the OTS and NCS groups. The ATL and OTS groups trained with the same intensity, frequency, and types of exercise.

Conclusions

At least in males, OTS was typified by increased estradiol, decreased testosterone, overreaction of muscle tissue to physical exertion, and immune system changes, with deconditioning effects of the adaptive changes observed in healthy athletes.

Keywords: sports endocrinology, metabolism, hormonal physiology

Key Points

Compared with sex-, age-, and body mass index-matched nonathlete controls, healthy athletes displayed multiple differences, including higher levels of testosterone and lymphocytes, an increased neutrophil : lymphocyte ratio, a paradoxically lower resting lactate level, and increased nocturnal urinary catecholamines (most not previously described), which are likely novel beneficial adaptive processes that athletes undergo.

Although healthy athletes demonstrated multiple beneficial adaptations, athletes affected by overtraining syndrome (OTS) showed a loss of these adaptations and exacerbations of muscular parameters and nocturnal urinary catecholamines. These findings may be responsible for the hallmark of OTS: an unexplained decrease in performance.

The testosterone : estradiol ratio was reduced by approximately 50% in OTS-affected athletes compared with healthy athletes and sedentary controls, showing a pathologic increase in estradiol, probably from enhanced aromatase activity.

Overtraining syndrome (OTS) is an emerging disorder1 resulting from excessive training load combined with inadequate recovery and poor sleep quality that leads to decreased performance and fatigue. It can be considered a dysfunctional adaptation (maladaptation) to overabundant exercise with insufficient rest that causes perturbations of multiple body systems (neurologic, endocrinologic, immunologic) and changes in mood.1–3 However, factors such as social or personal problems may also contribute to overtraining states. Chronic exposure to these factors can create a tissue environment that induces aberrant inflammatory, neurologic, metabolic, and hormonal responses as a consequence of long-term energy deprivation.1

Overtraining syndrome is 1 of 3 overtraining states, alongside functional overreaching (FOR) and nonfunctional overreaching (NFOR).4 Overreaching is an accumulation of training load that leads to decreased performance; recovery requires days to weeks, and if followed by appropriate rest, can lead to increased performance.2,5 Whereas FOR describes a short, reversible decrease in performance associated with acute symptoms, followed by improved performance after recovery,1 NFOR describes a short decrease in performance (but longer than that of FOR), with complete recovery after correction of the imbalance. In contrast, OTS describes a long-term (weeks to years) decrease in performance that can be accompanied by psychiatric or psychological disturbances.1,3 If overreaching is extreme and combined with additional stressors, OTS may result.2 Many consider overreaching and overtraining to lie along the same continuum.2,3,6 Indeed, differentiation of NFOR and OTS is clinically difficult and often possible only after a period of complete rest, when partial recovery may indicate a diagnosis of OTS1,6; unique characteristics are exhibited in each individual, and it is unlikely that affected athletes can be accurately classified into particular substates.

Changes in metabolic, immunologic, muscle, inflammatory, and hormonal responses have been reported in OTS-affected individuals and investigated as biomarkers of OTS.1,3,5,7–12 According to the latest guideline,1 of the potential markers, only creatine kinase (CK) tends to be higher; stimulated lactate is lower, and hormonal responses to exercise are blunted in OTS. Regarding basal hormone levels, contradictory results have been reported for nocturnal urinary catecholamines (NUCs), whereas basal testosterone, insulin-like growth factor 1, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, thyroid-stimulating hormone, adrenocorticotropic hormone, cortisol, and prolactin levels are mostly normal in OTS,4,8,13,14 showing a poor correlation with OTS. The underlying reasons for these findings remain unclear.

Finally, although our collective understanding of OTS has improved, much remains unknown about the mechanisms underlying its pathophysiology, tools for early identification and diagnosis, and approaches to prevention and treatment. Meanwhile, the diagnosis of OTS is difficult and based on clinical and exclusion criteria.1,3 Given the multiple physical and psychological consequences of OTS (particularly on long-term psychological well-being, as athletes with severe manifestations of OTS may never fully recover) and the increasing incidence of this syndrome, the condition must be recognized, diagnosed, and managed appropriately.

Owing to the lack of evidence regarding the biomarkers and pathophysiology of OTS, we conducted the Endocrine and Metabolic Responses on Overtraining (EROS) study, in which we compared basal hormonal profiles; responses to functional tests; muscular, inflammatory, and immunologic markers; body metabolism and composition; and eating, sleeping, and psychological characteristics. Comparisons were performed among 3 groups: OTS-affected athletes (OTS group), healthy athletes (ATL group), and healthy nonactive control participants (NCS group). The objective of studying 3 groups, including 2 control groups, was to determine whether any observed differences were due to dysfunction from OTS or the loss of adaptive changes to exercise (deconditioning) as an effect of OTS. In this study, termed the EROS-BASAL study, we evaluated muscular, hormonal, and basic inflammatory parameters to identify biomarkers of OTS. The other results have been presented in the EROS-HPA axis,15 EROS-STRESS,16 and EROS-PROFILE17 arms of the EROS study.

METHODS

Participant Selection

For the EROS study, we recruited athletes and healthy sedentary individuals through social media and performed a preliminary analysis of candidates regarding age and approximate body weight, height, and body mass index (BMI), which were then verified.

Detailed criteria for all participants, all athletes (OTS and ATL groups), and OTS candidates are shown in Table 1. Participants were required to be male, between 18 and 50 years old, without known medical conditions, and not taking any drug or hormone. Sedentary controls had to fulfill the initial inclusion criteria; to have not undertaken any physical activity, including walking, cycling, or swimming, for at least 3 years; and to lack a history of exercise. For all athletes, we required a minimum amount of physical activity to avoid misleading results from participants who, despite being physically active, performed insufficient exercise to cause exercise-induced adaptions. For the ATL group, we also required progressive improvement in performance retrospectively based on previous sport-specific performance tests, to avoid including athletes who were not currently under an intensive and progressive training program.

Table 1.

Clinical Inclusion Criteria for the Endocrine and Metabolic Responses on Overtraining (EROS) Study

| All Participants |

All Athletes |

Athletes With Overtraining Syndrome |

| Male sex | Exercise at least 4 times/wk | Underperformance of at least 10% of previous performance as verified by a certified sports coach or loss of at least 20% of time to fatigue |

| 18–50 years old | Exercise >300 min/wk | Prolonged underperformance that could not be explained by conditions that could lead to reduced performance (eg, infection, inflammation, hormonal dysfunction [the primary cause of decreased performance], and psychosocial or psychiatric conditions) |

| BMI = 20–32.9 kg/m2 (athletes)BMI = 20–29.9 kg/m2 (sedentary controls) | Moderate-to-vigorous training intensity (based on the Talk Test) | Persistent fatigue (>2 wk), as a subjective feeling, further confirmed by the Profile of Mood Scales fatigue and vigor subscales |

| No previous psychiatric disorders | Continuous training in their sport(s) for at least 6 mon | (Self-reported) Increased sense of effort in training relative to before overtraining syndrome |

| No use of centrally acting drugs | No interruption of >30 d | Average dietary caloric intake above the predicted basal metabolic rate (evaluated by a 7-d nutritional record, with calorie and macronutrient account, using Nutro [version 1.0; Associação Brasileira de Nutrologia, São Paulo, Brazil]) |

| No hormonal therapy in the preceding 6 mo | Designated an athlete by a professional coach | Exclusion of emotional and social concerns by the evaluation of financial, professional, familial, or conjugal problems |

| Decreased self-reported sleep quality compared with previous sleep quality |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index.

For participants suspected of having OTS, the criteria recommended by the 2013 joint guidelines on OTS from the European College of Sport Science and American College of Sports Medicine and other authors1,2 were precisely applied to exclude other dysfunctions and confirm OTS, including sport-specific tests, also detailed in Table 1.

Regarding the OTS substates, to evaluate whether affected athletes presented with FOR, NFOR, or OTS, we questioned them on their time to full recovery (when a few weeks are sufficient for full recovery, FOR or NFOR is more likely than OTS). When athletes presented with underperformance for less than 2 weeks, they were followed. If they improved, OTS was excluded; if underperformance persisted for 2 weeks, OTS was considered.

Participants underwent biochemical evaluations to exclude confounding disorders (Table 2), and some markers were used as part of the present study.

Table 2.

Biochemical Inclusion Criteria for the Endocrine and Metabolic Responses on the Overtraining (EROS) Study

| Measure |

Range Required for Inclusion |

Diseases Excluded by the Criteria |

Assay Method |

| Total testosterone | >200 ng/dL | Hypogonadism | Chemiluminescence assay |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone | <5 μIU/mL | Primary hypothyroidism | Chemiluminescence assay |

| Creatinine (and calculated estimated glomerular filtration rate) | <1.5 mg/dL (>60 mL/min) | Renal impairment | Jaffe enzymatic assay |

| Creatine kinase | <5000 U/L | Rhabdomyolysis, other myositis | Calorimetric activity assay; International Federation of Clinical Chemistry |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | <25 mm/h | Inflammation and other disorders (high negative predictive value) | Automated spontaneous sedimentation method |

| Ultrasensitive C-reactive protein | <3 mg/dL | Infections, inflammation, cardiovascular risk | Latex-intensified immunoturbidimetry |

| Hematocrit | 36%–54% | Anemia from several causes, polycythemia | Automated assay |

| Neutrophils | 1000–9000/mm3 | Infections, aplasia, neutropenic disorders | Automated assay |

| Alanine aminotransferase | <50 U/L | Liver dysfunctions | Calorimetric activity assays |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | <50 U/L | Liver dysfunctions, myolysis | Calorimetric activity assays |

| Vitamin B12 | >180 pg/mL | Neuropsychiatric symptoms from vitamin B12 deficiency | Chemiluminescence assay |

| Fasting glucose | <100 mg/dL | Prediabetes and diabetes | Enzymatic assay of hexokinase |

Procedures

For the athletes (the OTS and ATL groups), the type(s) of sport(s) performed, time since starting the sport(s), training intensity, duration of training per week (minutes), and number of rest days per week were recorded based on standardized tests to determine baseline characteristics.

As part of the EROS-BASAL arm of the present study, we compared the basal fasting levels of the following parameters among the 3 groups: serum total testosterone; estradiol (chemiluminescence assay); serum insulin-like growth factor 1 (chemiluminescence assay); serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (electrochemiluminescence assay); serum free thyronine (electrochemiluminescence assay); lactate (enzymatic assays); ferritin; erythrocyte sedimentation rate; C-reactive protein (CRP); creatinine; CK; high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides (calorimetric enzymatic assays) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (Friedewald equation); hematocrit, mean corpuscular volume, and numbers of neutrophils, lymphocytes, eosinophils, and platelets (automated assays); and nocturnal 12-hour urinary catecholamines and metanephrines (calorimetric enzymatic assays).

In athletes, all biochemical data were collected between 36 and 48 hours after the last training session, and tests were conducted after the same length of time since the previous training for consistency. It is noteworthy that the tests were performed immediately after the selection process, with less than 5 days between recruitment, application of clinical and biochemical inclusion and exclusion criteria, and collection of basal biochemical data; the full process (for the other arms of the EROS study) was performed in less than 10 days to prevent changes in the current states of the athletes. All concentrations were determined using commercially available, standardized, and validated assay kits in a laboratory. We calculated the testosterone : estradiol, testosterone : cortisol, neutrophil : lymphocyte, platelet : lymphocyte, and catecholamine : metanephrine ratios and compared them among the groups. No minimums were set for the markers analyzed. The interassay and intra-assay coefficients of variability for all of the biochemical markers were <3.5% and <3%, respectively.

For further information on the design, material, and methods, we have provided the raw data from the study in a repository (https://osf.io/bhpq9/).

Statistical Analysis

The methodologic prerequisites for the study of OTS markers as recommended by the latest guidelines1 were fulfilled. Using SPSS (version 21.0; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY), we performed nonparametric analysis-of-variance tests (Kruskal-Wallis tests) when the data were nonnormally distributed and 1-way analyses of variance when the data were normally distributed. Post hoc adjusted Dunn, Dunnett T3, and Tukey tests were conducted when the differences were statistically significant among the 3 groups (P < .05), according to the normality criteria. The results were presented as means and standard deviations when normally distributed and as medians and confidence intervals when nonnormally distributed.

RESULTS

Participants' Baseline and Training Characteristics

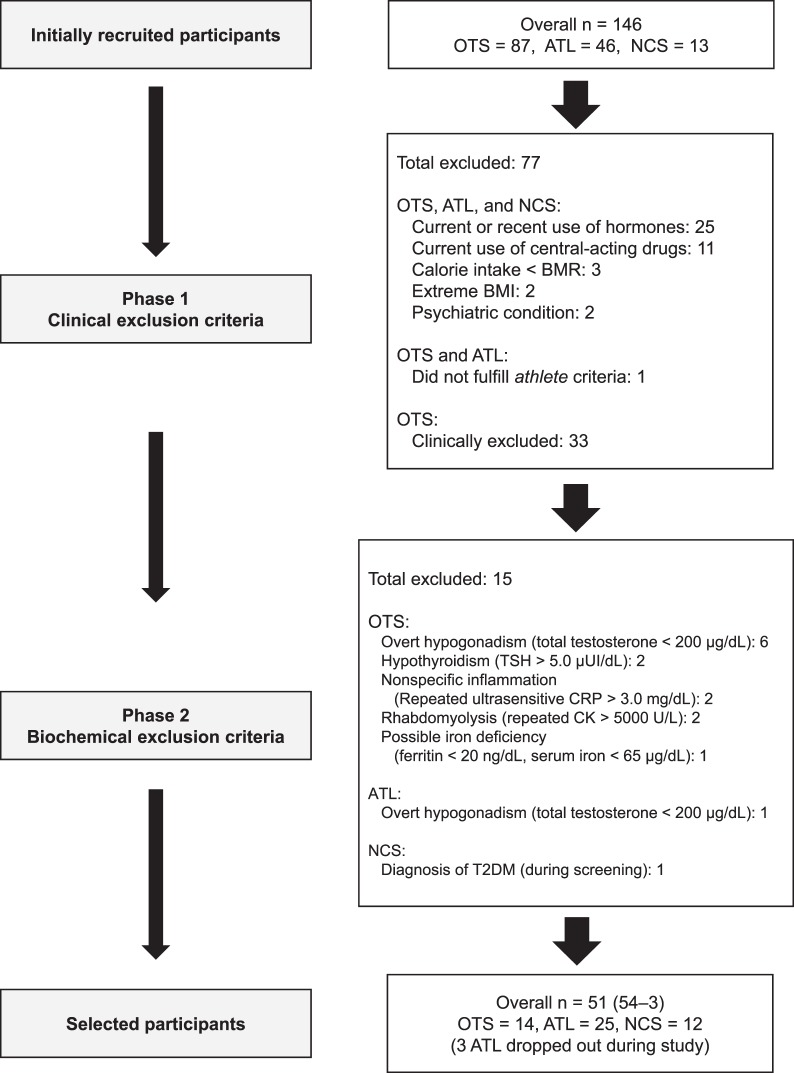

Of the 146 participants initially recruited, 51 were eligible for inclusion (34.2%; OTS = 14, ATL = 25, NCS = 12). A flowchart depicting the inclusion and exclusion process is shown in the Figure.

Figure.

Flowchart depicting the inclusion and exclusion process. Abbreviations: ATL, healthy athletes; BMI, body mass index; BMR, basal metabolic rate; CK, creatine kinase; CRP, C-reactive protein; NCS, nonactive healthy control; OTS, overtraining syndrome; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

The mean age (OTS = 30.6 ± 4.6 years, ATL = 32.7 ± 5.0 years, NCS = 33.2 ± 8.7 years) and mean BMI (OTS = 26.7 ± 2.0 kg/m2, ATL = 24.9 ± 2.1 kg/m2, and NCS = 25.0 ± 3.7 kg/m2) were statistically similar among the groups. The athletes reported a similar mean duration of training per week (OTS = 574.3 ± 204.4 minutes, ATL = 550 ± 180.2 minutes), number of training days per week (OTS = 5.36 ± 0.5 days, ATL = 5.46 ± 0.66 days), and training intensity (scale of 0–10: OTS = 8.79 ± 0.80, ATL = 8.76 ± 1.16); duration of training per week was evaluated against a formal schedule that all athletes followed strictly, whereas intensity of training was based on formal sport-specific scales. Importantly, the recruitment of participants with OTS may be challenging, as they are not usually followed with specific tests for quantifying the volume and intensity of their training. For a study on naturally occurring OTS, we considered the amount of information regarding the baseline and training characteristics sufficient, particularly when compared with the general lack of information in previous studies on OTS.1,15 All 39 athletes performed both endurance and resistance activities, including the high-intensity functional training regimen CrossFit in 78.6% (11 of 14) and 96% (24 of 25) of the OTS and ATL groups, respectively.15–17

The characteristics of OTS presented by the affected participants are detailed in Table 3. Given the lack of specific performance tests for diagnosing OTS, the different patterns of the tests performed by each affected athlete, and the complexity of the sports performed by all the athletes, the results of each athlete's specific tests before and during OTS are not described here. All affected athletes were diagnosed with OTS rather than FOR or NFOR because of their prolonged and incomplete recoveries. Indeed, all athletes selected for the OTS group could be clearly classified as OTS, regardless of the different classifications among OTS, FOR, and NFOR,1 as they reported that they maintained training despite the possible diagnosis of overreaching. The persistence of the underperformance and other symptoms after 2 to 3 weeks in the absence of confounding disorders is the best way to diagnose OTS, as most authors consider OTS as part of a continuum of overreaching. Moreover, OTS-affected athletes had an average period of underperformance and symptoms of 44 days, and none had a period of underperformance and fatigue shorter than 3 weeks, which allowed OTS to be diagnosed in all the athletes.

Table 3.

Features of the Athletes Affected by Overtraining Syndrome (OTS)

| Parameter |

OTS-Affected Athletes (n = 14) |

| Fatigue lasting more than 2 wk | 100 |

| Mean duration of fatigue, d | 44.3 ± 23 |

| Performance fully recovered by the time of the study, % | 0 |

| Increased intensity and volume of training in the last 3 months, % | 100 |

| Training monotony, % | 14.30 |

| Increased frequency of infections, % | 21.40 |

| Sleep disturbance started or worsened with OTS, % | 42.90 |

| Increased effort for same training load, % | 100 |

| Increased sensitivity to heat or cold, % | 42.90 |

| Profile of Mood States | |

| Fatigue subscale (0–28; the higher, the worse) | |

| >14, % | 85.70 |

| Mean score | 19.9 ± 6.1 |

| Vigor subscale (0–28; the lower, the worse) | |

| <14, % | 85.70 |

| Mean score | 9.9 ± 5.6 |

| Specific tests performed (coach verified), % of athletes (No.) | |

| Pace (compared with previous pace) | 100 (14) |

| Volume of training | 92.8 (13) |

| Highest speed or intensity achieved | 21.4 (3) |

| Maximum strength at a 1-repetition maximum strength test | 14.3 (2) |

| Maximum number of repetitions for the same weight lifted | 7.1 (1) |

Biochemical and Hormonal Analyses

The biochemical values are provided as means and standard deviations (Table 4) and as medians and confidence intervals (Table 5). Hormonal levels are shown in Table 6. Compared with the ATL group, the OTS group had higher levels of estradiol, lactate, CK, total NUC, and urinary nocturnal dopamine. In contrast, total testosterone, neutrophils, and the testosterone : estradiol ratio were lower in the OTS group. Compared with the NCS group, the ATL group displayed lower levels of lactate, hematocrit, lymphocytes, and eosinophils but higher levels of creatinine (creatinine levels became similar after adjusting for muscle mass) and CK and a higher platelet : lymphocyte ratio.

Table 4.

Basal Biochemical Levels

| Mean ± SD |

||||

| Parameter |

Athletes With Overtraining Syndrome |

Healthy Athletes |

Sedentary Controls |

Normal Range |

| No. of participants | 14 | 25 | 12 | |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.11 ± 0.14 | 1.14 ± 0.17b | 1.01 ± 0.1 | 0.7–1.3 |

| Hematocrit, % | 44.5 ± 2.3 | 44.1 ± 2.5c | 46.4 ± 2.4 | 38–50 |

| Mean corpuscular volume, fL | 86.5 ± −2.5 | 87.5 ± 4.8 | 88.3 ± 3.9 | 80–96 |

| Neutrophils, /mm3 | 2986 ± 761a | 3809 ± 1431 | 3186 ± 847 | 1500–6000 |

| Lymphocytes, /mm3 | 2498 ± 487 | 2154 ± 640c | 2820 ± 810 | 800–4000 |

| Platelets, ×103/mm3 | 248 ± 53 | 235 ± 38 | 225 ± 63 | 150–450 |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, mg/dL | 113 ± 17 | 117 ± 69 | 104 ± 17 | <130 |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, mg/dL | 53.9 ± 6.4 | 60.7 ± 14.4 | 51.5 ± 8.7 | >45 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 91 ± 32 | 94 ± 46 | 152 ± 87 | <150 |

| Neutrophil : lymphocyte ratio | 1.23 ± 0.34a | 2 ± 1.28c | 1.27 ± 0.73 | e |

| Platelet : lymphocyte ratio | 104.1 ± 34.2 | 119.1 ± 43.4d | 82.4 ± 19.5 | e |

| Vitamin B12, pg/mL | 517 ± 233 | 553 ± 188 | 442 ± 155 | 180–900 |

Difference between the overtraining and healthy athlete groups (P < .05).

Difference between the healthy athlete and sedentary control groups (P < .01).

Difference between the healthy athlete and sedentary control groups (P < .05).

Difference between the healthy athlete and sedentary control groups (P < .005).

Normal range not established.

Table 5.

Basal Biochemical Levels

| Median (95% Confidence Interval) |

||||

| Parameter |

OTS Athletes |

Healthy Athletes |

Sedentary Controls |

Normal Range |

| No. of participants | 14 | 25 | 12 | |

| Lactate, nmol/L | 1.11 (0.79, 2.13)a | 0.78 (0.47, 1.42)c | 1.17 (0.57, 1.57) | 0.5–2 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | 194.1 (68.2, 416.6) | 168 (61.5, 374.6) | 229.4 (90.5, 540.4) | 20–350 |

| Creatine kinase, U/L | 569 (126, 3012)b | 347 (92, 780)d | 105 (80, 468)e | f |

| Eosinophils, /mm3 | 155 (58, 509) | 107 (31, 364)c | 193 (51, 549) | <500 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/dL | 0.1 (0.03, 2.55) | 0.06 (0.02, 0.46) | 0.08 (0.02, 0.23) | <3 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, mm/h | 2.5 (1.6, 12) | 2 (2, 12.4) | 2 (1.5, 6) | <15 |

Abbreviation: OTS, overtraining syndrome.

Difference between the OTS and healthy athlete groups (P < .01).

Difference between the OTS and healthy athlete groups (P < .05).

Difference between the healthy athlete and sedentary control groups (P < .05).

Difference between the healthy athlete and sedentary control groups (P < .01).

Difference between the OTS and sedentary control groups (P < .001).

Range not applicable to athletes.

Table 6.

Basal Hormone Levels

| Mean ± SDa |

||||

| Parameter |

Overtraining Syndrome Athletes |

Healthy Athletes |

Sedentary Controls |

Normal Range |

| No. of participants | 14 | 25 | 12 | |

| Total testosterone, ng/dL | 422.6 ± 173.2b | 540.3 ± 171.4e | 405.9 ± 156.3 | 240–840 |

| Estradiol, pg/mL | 40.1 ± 10.8b | 29.8 ± 13.9 | 25.7 ± 11.2f | <40 |

| Insulin-like growth factor-1, ng/mL | 185 ± 44 | 177 ± 51 | 184 ± 59 | 100–250 |

| Free thyronine, pg/ml | 3.2 ± 0.6 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 2.3–4.2 |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone, μIU/mL | 2.3 ± 1 | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 1.8 ± 0.9 | 0.5–4.5 |

| Total catecholamines, μg/12 h | 257 ± 166c | 175 ± 69 | 133 ± 54g | 100–400 |

| Testosterone : estradiol ratio | 10.8 ± 3.7d | 20.8 ± 9.9 | 20.3 ± 13g | h |

| Testosterone : cortisol ratio | 39.3 ± 19.8 | 45 ± 15.8 | 39.6 ± 21.3 | h |

| Catecholamine : metanephrine ratio, ×100 | 104.0 ± 57.3 | 92.2 ± 60.4 | 65.5 ± 23.0g | h |

| Noradrenaline, μg/12 h | 27.4 ± 10.5 | 22.3 ± 12.7 | 17.4 ± 9.1g | 10–70 |

| Epinephrine, μg/12 h | 31.7 ± 6.1 | 21 ± 9.8 | 20.6 ± 7.9 | 0–15 |

| Dopamine, μg/12 h | 227 ± 159c | 149 ± 60 | 114 ± 45f | 70–280 |

| Total metanephrines, μg/12 h | 276 ± 156 | 222 ± 80 | 221 ± 107 | 150–450 |

| Metanephrine, μg/12 h | 46.1 ± 31.1 | 44.9 ± 27.2 | 41.7 ± 25.4 | 20–100 |

| Normetanephrine, μg/12 h | 93.5 ± 48.3 | 86.6 ± 41.6 | 90.8 ± 48.2 | 40–200 |

| Urinary volume, mL/12 h | 1152 ± 438 | 1154 ± 761 | 1045 ± 656 | 400–2000 |

Except epinephrine, which is median (95% confidence interval).

Difference between the OTS and healthy athlete groups (P < .01).

Difference between the OTS and healthy athlete groups (P < .05).

Difference between the OTS and healthy athlete groups (P < .001).

Difference between the healthy athlete and sedentary control groups (P < .05).

Difference between the OTS and sedentary control groups (P < .01).

Difference between the OTS and sedentary control groups (P < .05).

Normal range not established.

Levels were generally similar between the OTS and NCS groups except for a lower testosterone : estradiol ratio and higher estradiol, CK, total NUC, and catecholamine : metanephrine ratio in the OTS group.

DISCUSSION

Overall and consistent with our findings in the other arms of the EROS study,15–17 the OTS athletes appeared more similar to sedentary individuals than to healthy athletes, reflecting relative (compared with the expected results in athletes) but not actual dysfunctions (compared with the general population). Athletes tended to have a lower hematocrit than sedentary participants, which contradicts the findings of one study18 that revealed an increased hematocrit in OTS participants, although this was either not mentioned or no differences were observed in other studies.1 This may have resulted from better hydration among athletes than non–physically active participants, because athletes tend to be more aware of healthy habits.

In addition, we found that the OTS group had a reduced number of neutrophils, which had not previously been noted. Conversely, we observed an increased number of lymphocytes in the OTS group compared with the ATL and NCS groups, which contradicts the findings of an earlier study.19 The combination of increased lymphocytes and decreased neutrophils reinforces the theory that a compromised immune system may contribute to the pathophysiology of OTS and related states.1,19,20 The novel immunologic findings may be due to the larger number of participants with naturally occurring OTS (rather than FOR or NFOR) in our study, which may have led to more significant differences. Both neutrophils and lymphocytes may represent markers of OTS or a loss of conditioning.

The neutrophil : lymphocyte ratio is increasingly recognized for its prognostic value in cardiovascular disease, infection, inflammatory diseases, and several types of cancer21,22; an increased neutrophil : lymphocyte ratio was shown to predict a poorer prognosis,21 although a normal range is yet to be determined. However, the unprecedented finding of an increased neutrophil : lymphocyte ratio in the absence of any abnormalities may suggest an additional adaptive process that occurs in response to training. Furthermore, a decreased neutrophil : lymphocyte ratio in OTS-affected athletes, when compared with healthy athletes, may indicate either a loss of a theoretical beneficial adaption to sports or a protective role in OTS.

The levels of creatine kinase (an enzyme produced mostly by the muscles1) were expectedly lower in sedentary individuals compared with athletes. However, increased CK levels were observed in participants with OTS, likely resulting from exacerbated oxidative stress and muscle damage and prolonged and incomplete muscle recovery, with consequent relative atrophic and functionally impaired muscle.1 This is possibly a maladaptation of OTS in response to a chronic depletion of energy and mechanisms of repair,1 which corroborates theories of dysfunctional muscle responses to exercise during OTS as part of the underperformance.1–3,6 This hypothesis is reinforced by the paradoxically reduced muscle mass; aberrant overconsumption of proteins or amino acids; average intake of calories, proteins, and carbohydrates approximately 2 times lower than that of healthy athletes; and worse sleep in OTS, as shown in the EROS-PROFILE arm of our study.17

Lactate is widely produced in the organism, typically released after exhaustive exercises and in smaller amounts during mild to moderate activities and while at rest. Levels are exponentially proportional to the level of activity, as well as the size of the muscles used for the movements.2,6 Clinically, it is used as a prognostic factor for critical illnesses but has also been proposed as a prognostic factor in chronic disorders and even in healthy participants in an inverse correlation,19–21,23,24 wherein increased lactate clearance has been found to be beneficial.25 We observed a paradoxical reduction in resting basal lactate levels in the ATL group compared with the NCS group, as we would expect increased levels reflecting previous intense muscle stimulation in healthy athletes, even after 36 to 48 hours of resting. This unexpected finding may reflect an increased rate of lactate clearance rather than decreased lactate production. Lactate is a physiological product of muscle stimulation, which may be an additional beneficial conditioning effect of training, in which increased clearance may induce faster recovery and allow a shorter interval between sessions.23 However, not only was the reduction in resting basal lactate lost when OTS was present, but lactate levels also seemed to rise with OTS, likely owing to the impaired muscle recovery, similar to the increased CK levels. Moreover, a high level of lactate in muscle tissue likely impairs performance, which may be an additional underlying mechanism of OTS, and decreased lactate clearance in OTS requires a prolonged interval between training sessions, which is also observed in OTS. Our results apparently contradict previous findings1,3 that lactate levels were reduced in OTS, although the previous authors evaluated lactate levels at postexercise (submaximal and maximal lactate levels) instead of during rest periods; the former does not allow analysis of the lactate clearance and dynamic metabolism.

Despite the use of ferritin and CRP as markers of OTS3,6,19 (irrespective of the lack of studies showing consistent correlations between these markers and the condition1), we failed to demonstrate differences in ferritin, CRP, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate levels between healthy and OTS athletes. These observations reinforce the fact that classical clinical inflammation does not contribute to OTS. However, we did not evaluate other specific inflammatory markers described as altered in OTS, including interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-10, and tumor necrosis factor α.1,24–27 Moreover, impaired glucose transporter type 4 signaling in the myocytes, caused by an increase in some cytokines in the muscle tissue,26,27 may be an additional mechanism to explain the dysfunctional muscular metabolism, as demonstrated by increases in both lactate and CK levels.

In terms of hormonal changes, the chronic increase in testosterone levels observed in healthy athletes practicing mixed strength and endurance exercises25 was assumed to be an additional beneficial conditioning effect that could lead to optimal muscle hypertrophy and function, improved sports performance and overall mood states,17 increased metabolic rate (even at rest),17 and enhanced metabolic pathways, as endogenous testosterone may improve glucose, lipid, and amino acid metabolism.28 Conversely, OTS was associated with reduced testosterone, also previously described,27 which may lead to impaired muscle recovery, decreased muscle mass, reduced basal metabolic rate, and less fat oxidation.17

Estradiol has recently been shown to play beneficial roles in males with respect to bone mass, libido, humor, and body composition29 when accompanied by a simultaneous increase in testosterone. The simultaneous increase results from increased hypothalamic-pituitary stimulation (through gonadotropin-releasing hormone and luteinizing hormone), leading to elevated testosterone and a consequent natural increase in aromatase activity as a protective mechanism to prevent excessive testosterone, resulting in a proportional increase in estradiol. Conversely, during OTS, increased estradiol in the absence of increased testosterone or even with a paradoxical decrease was observed and suggests an abnormally increased level of aromatase enzyme, which is unlikely to be stimulated physiologically, centrally, or via testosterone. This leads to a decreased testosterone : estradiol ratio, which may reflect an antianabolic state rather than providing benefits. The hypothesized increased aromatase activity in OTS is supported by the fact that enhanced gonadotrophic axis stimulation observed in healthy athletes, compared with sedentary individuals, is maintained in OTS. Because lower testosterone levels in OTS are not due to a lack of central (gonadotrophic) stimulation, we hypothesized that reduced testosterone levels are a consequence of increased conversion to estradiol.

The testosterone : cortisol ratio, an alleged marker of the anabolic : catabolic state ratio, has been used as a marker of OTS when reduced by at least 30%, despite the lack of evidence regarding its association with OTS.1,8 In this study, the testosterone : cortisol ratio did not differ between the OTS and ATL groups, which refutes the utility of this ratio as a marker of OTS. Indeed, despite the acute catabolic effects of cortisol, its chronic actions include proximal but not diffuse muscle atrophy, and it has anabolic effects on visceral and central fat, leading to weight gain instead of weight loss in chronic hypercortisolism states.30 Moreover, simultaneous cortisol and testosterone regulation is unlikely, as they are products of different hypothalamus-pituitary axes. Therefore, use of the testosterone : cortisol ratio for evaluating the chronic anabolic : catabolic state is inappropriate. Compared with the testosterone : cortisol ratio, the testosterone : estradiol ratio better predicts the anabolic : catabolic state, as the testosterone conversion to estradiol requires only 1 enzyme and can directly respond to any demand.

Elevated NUC levels may reflect an adaptation to exercise. Nonetheless, the observed elevation seems to be exacerbated during OTS, which reinforces previous findings.1,8 Also, relatively less conversion of catecholamines into metanephrines (their metabolites) was found in OTS compared with healthy athletes and sedentary individuals, as demonstrated by the higher catecholamine : metanephrine ratio in the OTS group. In this case, instead of a deconditioning process, exacerbation of catecholamines and their reduced conversion to metanephrines may be a compensatory attempt to maintain performance during training and minimal functioning of the organism, despite the chronic depletion of energy and mechanisms of repair1 that are present in OTS.

The plausibility of the overall normal results found in OTS, though different from ATL, is based on the adaptive, conditioning, and optimizing biochemical processes that athletes usually undergo.15–17 These adaptive changes observed in healthy athletes led to differences not only compared with OTS athletes but also when compared with healthy sedentary participants. Consequently, the EROS study provided data not only for OTS but also for the physiological changes that occur in response to sports, in the absence of dysfunction, by allowing us to investigate a healthy sedentary control group that was sex, age, and BMI matched.

The main limitations of our study were that, unlike previous reports, our athletes performed both strength and endurance exercises. The results might have been different if we had compared athletes who exclusively practiced endurance exercises, similar to most earlier studies. Moreover, because only men were evaluated, it is unclear whether our findings are applicable to women. The number of participants, although larger than in many previous studies,1,8 was not substantially large.

CONCLUSIONS

Overtraining syndrome affects the immunologic, musculoskeletal, and adrenergic systems, as well as likely increasing aromatase activity, but did not result in inflammatory changes as shown on the basic inflammatory panel, at least in males. The OTS-affected male athletes lost beneficial changes that typically occur in athletes, but they did not show absolute dysfunction; rather, their results were similar to those of sedentary participants.

REFERENCES

- 1.Meeusen R, Duclos M, Foster C, et al. European College of Sport Science. American College of Sports Medicine Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of the overtraining syndrome: joint consensus statement of the European College of Sport Science and the American College of Sports Medicine. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(1):186–205. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318279a10a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kreher JB, Schwartz JB. Overtraining syndrome: a practical guide. Sports Health. 2012;4(2):128–138. doi: 10.1177/1941738111434406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rietjens GJ, Kuipers H, Adam JJ, et al. Physiological, biochemical and psychological markers of strenuous training-induced fatigue. Int J Sports Med. 2005;26(1):16–26. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-817914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hug M, Mullis PE, Vogt M, Ventura N, Hoppeler H. Training modalities: over-reaching and over-training in athletes, including a study of the role of hormones. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;17(2):191–209. doi: 10.1016/s1521-690x(02)00104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nederhof E, Zwerver J, Brink M, Meeusen R, Lemmink K. Different diagnostic tools in nonfunctional overreaching. Int J Sports Med. 2008;29(7):590–597. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-989264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kentta G, Hassmen P, Raglin JS. Training practices and overtraining in Swedish age-group athletes: association with training behavior and psychosocial stressors. Int J Sports Med. 2001;22(6):460–465. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-16250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slivka DR, Hailes WS, Cuddy JS, Ruby BC. Effects of 21 days of intensified training on markers of overtraining. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(10):2604–2612. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e8a4eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cadegiani FA, Kater CE. Hormonal aspects of overtraining syndrome: a systematic review. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 2017;9:14. doi: 10.1186/s13102-017-0079-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coutts AJ, Reaburn P, Piva TJ, Rowsell GJ. Monitoring for overreaching in rugby league players. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2007;99(3):313–324. doi: 10.1007/s00421-006-0345-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meeusen R, Nederhof E, Buyse L, Roelands B, De Schutter G, Piacentini MF. Diagnosing overtraining in athletes using the two-bout exercise protocol. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44(9):642–648. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.049981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meeusen R, Piacentini MF, Busschaert B, Buyse L, De Schutter G, Stray-Gundersen J. Hormonal responses in athletes: the use of a two bout exercise protocol to detect subtle differences in (over)training status. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2004;91(2–3):140–146. doi: 10.1007/s00421-003-0940-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urhausen A, Gabriel HH, Kindermann W. Impaired pituitary hormonal response to exhaustive exercise in overtrained endurance athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30(3):407–414. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199803000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elloumi M, El Elj N, Zaouali M, et al. IGFBP-3, a sensitive marker of physical training and overtraining. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(9):604–610. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.014183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fry AC, Kraemer WJ, Ramsey LT. Pituitary-adrenal-gonadal responses to high-intensity resistance exercise overtraining. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1998;85(6):2352–2359. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.6.2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cadegiani FA, Kater CE. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis functioning in overtraining syndrome: findings from Endocrine and Metabolic Responses on Overtraining Syndrome (EROS)—EROS-HPA Axis. Sports Med Open. 2017;3(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s40798-017-0113-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cadegiani FA, Kater CE. Hormonal and prolactin response to a non-exercise stress test in athletes with overtraining syndrome: results from the Endocrine and Metabolic Responses on Overtraining Syndrome (EROS)—EROS-STRESS. J Sci Med Sport. 2018;21(7):648–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2017.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cadegiani FA, Kater CE. Body composition, metabolism, sleep, psychological and eating patterns of overtraining syndrome: results of the EROS study (EROS-PROFILE) J Sports Sci. 2018;36(16):1902–1910. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2018.1424498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aïssa Benhaddad A, Bouix D, Khaled S, et al. Early hemorheologic aspects of overtraining in elite athletes. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 1999;20(2):117–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lakier Smith L. Cytokine hypothesis of overtraining: a physiological adaption to excessive stress? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(2):317–331. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200002000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith LL. Overtraining, excessive exercise, and altered immunity: is this a T helper-1 versus T helper-2 lymphocyte response? Sports Med. 2003;33(5):347–364. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200333050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forget P, Khalifa C, Defour JP, Latinne D, Van Pel MC, De Kock M. What is the normal value of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio? BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s13104-016-2335-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suh B, Shin DW, Kwon HM, et al. Elevated neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and ischemic stroke risk in generally healthy adults. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0183706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farrell JW, III, Lantis DJ, Ade CJ, Cantrell GS, Larson RD. Aerobic exercise supplemented with muscular endurance training improves onset of blood lactate accumulation. J Strength Cond Res. 2018;32(5):1376–1382. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000001981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joro R, Uusitalo A, DeRuisseau KC, Atalay M. Changes in cytokines, leptin, and IGF-1 levels in overtrained athletes during a prolonged recovery phase: a case-control study. J Sports Sci. 2017;35(23):2342–2349. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2016.1266379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lomax M. The effect of three recovery protocols on blood lactate clearance after race-paced swimming. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26(10):2771–2776. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318241ded7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayes LD, Sculthorpe N, Herbert P, Baker JS, Spagna R, Grace FM. Six weeks of conditioning exercise increases total, but not free testosterone in lifelong sedentary aging men. Aging Male. 2015;18(3):195–200. doi: 10.3109/13685538.2015.1046123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiao W, Chen P, Dong J. Effects of overtraining on skeletal muscle growth and gene expression. Int J Sports Med. 2012;33(10):846–853. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1311585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foresta C, Ferlin A, Lenzi A, Montorsi P, Italian Study Group on Cardiometabolic Andrology The great opportunity of the andrological patient: cardiovascular and metabolic risk assessment and prevention. Andrology. 2017;5(3):408–413. doi: 10.1111/andr.12342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bilha SC, Branisteanu D, Buzduga C, et al. Body composition and circulating estradiol are the main bone density predictors in healthy young and middle-aged men. J Endocrinol Invest. 2018;41(8):995–1003. doi: 10.1007/s40618-018-0826-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delivanis DA, Iñiguez-Ariza NM, Zeb MH, et al. Impact of hypercortisolism on skeletal muscle mass and adipose tissue mass in patients with adrenal adenomas. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2018;88(2):209–216. doi: 10.1111/cen.13512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]