Abstract

Background:

High-dose (HD) tigecycline regimen is increasingly used in infectious diseases, however its efficacy and safety versus low-dose (LD) is still unclear.

Methods:

A systematic review and meta-analysis was performed; PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, clinicalTrials.gov, Wanfang, VIP, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), were searched using terms “tigecycline” AND “dose” up to October 31, 2018. Eligible studies were randomized trials or cohort studies comparing mortality, clinical response, microbiological eradication and safety of different tigecycline dose regimens for any bacterial infection. The primary outcome was mortality, and the secondary outcomes were clinical response rate, microbiological eradiation rate and adverse events (AEs). Meta-analysis was done with random-effects model, with risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) calculated for all outcomes.

Results:

Of 951 publications retrieved, 17 studies (n = 1041) were pooled in our meta-analysis. The primary outcome was available in 11 studies, and the RR for mortality was 0.67 (95% CI 0.53–0.84, P < .001). Clinical response (RR 1.46, 95% CI 1.30–1.65, P < .001) and microbiological eradication rate (RR 1.61, 95% CI 1.35–1.93, P < .001) were both higher in HD than in LD tigecycline regimen. However, non-Chinese study subgroup presented no statistical significance between HD and LD regimen, RR for mortality, clinical response and microbiological eradication were 0.79 (95% CI 0.56–1.14, P = .21), 1.35 (95% CI 0.96–1.92, P = .26), 1.00 (95% CI 0.22–4.43, P = 1.00), respectively. AEs did not differ between HD and LD tigecycline (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.80–1.26, P = .97).

Conclusion:

HD tigecycline regimen reduced mortality meanwhile improved clinical efficacy and should be considered in serious infections caused by multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant (MDR/XDR) bacteria.

Keywords: clinical response, high dose, meta-analysis, mortality, tigecycline

1. Introduction

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) to current available antibiotics is increasing. Resistant pathogens such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacter species, Enterococcus faecium and Staphylococcus aureus account for the majority of nosocomial infections which challenged the prognostic of infection diseases. Infections with resistant pathogens are associated with increased mortality, morbidity, and length and cost of hospital stay. Classic agents used to treat these pathogens have become powerless and new antibiotics available might have already become targets for bacterial mechanisms of resistance.[1,2] Therefore, development of new antibiotics with high potency, stability against the mechanisms of resistance, and favorable pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) characteristics has become an urgent priority.

Tigecycline is a glycylcycline antibiotic with broad-spectrum activity against nearly all Gram-positive, Gram-negative (except Proteus sp. and Pseudomonas aeruginosa), atypical, anaerobic, as well as MDR pathogens.[3,4] Tigecycline was first approved by the FDA in 2005. Its FDA approved uses include complicated skin/skin structure infections, complicated intra-abdominal infections, and community-acquired bacterial pneumonia.[4]

Due to its low potential for resistance and broad spectrum activity, tigecycline is increasingly used for treatment of MDR infections.[5] However, several studies have reported on the treatment failures of standard dose tigecycline therapy (100 (IV) ×1 followed by 50 mg (IV) q12 h), for example, in a phase 3 study, the cure rates for patients with hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) treated with tigecycline at the approved dose were lower than those seen with patients treated with imipenem/cilastatin (47.9% vs 70.1%, respectively).[6] A meta-analysis of Phase 3 and 4 clinical trials also demonstrated an increase in all-cause mortality in standard dose tigecycline treated patients especially with ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) compared to controls.[7] From the point of its PK/PD characteristics, tigecycline is initially concluded to display linear pharmacokinetics,[8] however, closer evaluation supports non-linear pharmacokinetics, which may be further utilized to optimize the therapeutic dosing regimen.[9] A higher dose tigecycline was proposed for serious infections caused by MDR pathogens,[10,11] and some centers have implemented clinically but with unequal outcome.[12–14] To date there has not been a meta-analysis performed on studies investigating high-dose (HD) vs low-dose (LD) tigecycline, whether HD regimen is beneficial still remains obscure.

Therefore, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to compare the efficacy and safety of HD with LD tigecycline regimens in treating serious infections.

2. Methods

2.1. Data source and searches

An extensive search of PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, clinicalTrials.gov, as well as Wanfang, VIP, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) up to October 31, 2018 were performed. The search terms applied to all databases was as follows: “tigecycline” AND “dose”. The reference lists of the all relevant articles were manually searched to find further potentially eligible studies. No language restrictions were imposed.

2.2. Study selection

Studies that compared HD tigecycline vs LD tigecycline for the treatment of any bacterial infections were considered eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis. Studies published as both conference abstracts/posters and full-text articles were included. Studies including overlapped patient populations, the latest published studies were included. Cohort studies only reporting on the outcomes of patients receiving HD tigecycline without comparing with LD regimen were excluded. Case reports, clinical studies reporting on PK/PD outcomes as well as studies reporting none of the following outcomes were also excluded: mortality, clinical response rate (as defined in individual studies), microbiological eradication rate and adverse events (AEs).

2.3. Data extraction and outcomes

Two reviewers (JHG and ZQS) independently did the search, applied predefined inclusion & exclusion criteria and extracted the data. For all outcomes, data were extracted for the available largest patient population evaluated. The following data were extracted from every study: name of the first author, year of publication, study design and period, country, number of patients, site of infection, causative pathogen, dosing regimen of tigecycline, concomitant antibiotic treatment administered. In addition, outcomes such as mortality, clinical response rate, microbiological eradication rate and AEs according to different tigecycline doses were recorded. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality, secondary outcomes including treatment response, microbiological eradication and AEs.

2.4. Statistical analyses

The meta-analysis was done with random-effects models in Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program] (Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014). Mantel-Haenszel model with random effects was used because of the obvious heterogeneity across the studies included in the meta-analysis (e.g., different site or severity of infections, concomitant antibiotic treatment, and time to test of cure visit).[15] For all outcomes, pooled risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated according to the Mantel-Haenszel method. Heterogeneity in the results of the studies was assessed using the χ2 test for heterogeneity and the I2 measure of inconsistency.[16] For outcomes of mortality and AEs, RR <1 favors HD-regimen of tigecycline, and for clinical response rate and microbiological eradication rate, RR >1 favors HD-regimen. Subgroup analyses were done by country, type of infection and, for the outcome of AEs, by systems/manifestation. All subgroup and sensitivity analyses were pre-specified, with the exception of 1 sensitivity analysis excluding 2 studies with different HD or LD regimen.

This is a meta-analysis, which does not need to be approved by the institutional review board or Ethics committee.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of included studies

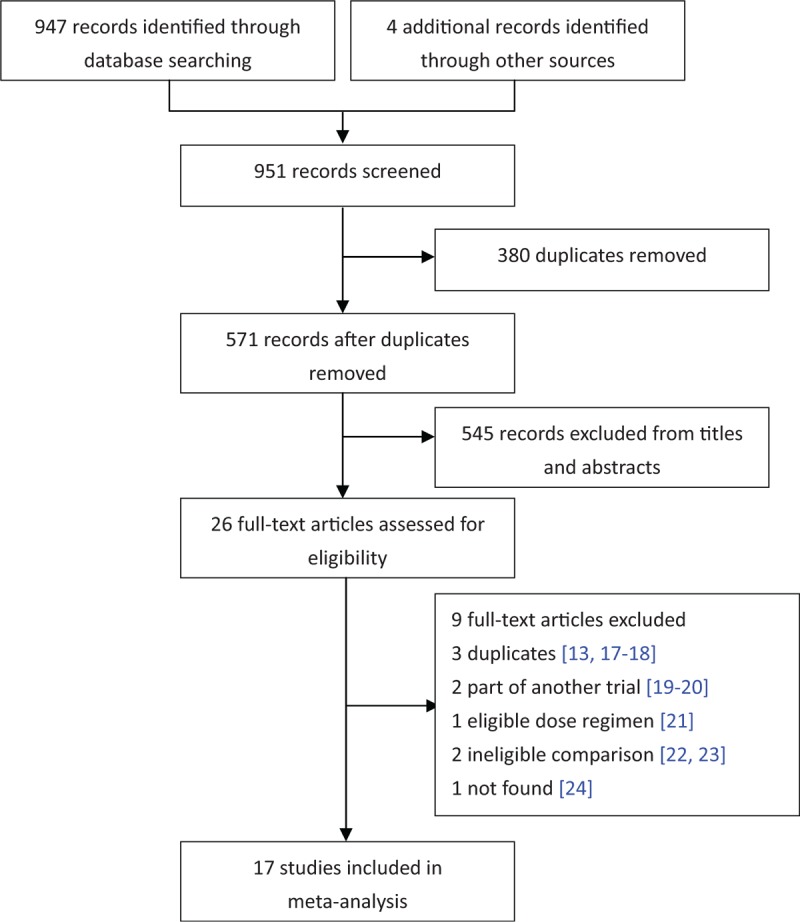

Figure 1 presents the overall search protocol. 951 potential articles were identified, 26 studies met the inclusion & exclusion criteria according to information in the title and abstract were assessed for eligibility, of which 9 were excluded.[13,17–24] Seventeen studies[12,14,25–39] with a total of 1041 patients were included in the meta-analysis: 16 single-center study and one multi-center study.[12] 3 random controlled trial,[12,34,36] among which one was a phase 2 double-blind study,[12] one described the randomization method,[34] while the other without any detail illustration,[36] 3 prospective cohort study[25,28,32] and 11 retrospective cohort study. Studies covered several different countries, including Italy (2 studies[25,26]), Spain (2 studies[27,39]), Brazil (1 study[28]), China (11studies, 3 published in English,[14,31,35] and 8 in Chinese) and one international multicenter.[12]

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection.

The HD and LD regimen in most studies were 100 mg every 12 hours and 50 mg every 12 hours respectively, except one[12] compared 100 mg every 12 hours vs 75 mg every 12 hours and one[33] compared 75 mg every 12 hours vs 50 mg every 12 hours. At least 1 concomitant systemic antibiotic was applied in 14 trials, 2 trials[32,36] without concomitant antibiotic treatment and one[39] did not refer to concomitant antibiotics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

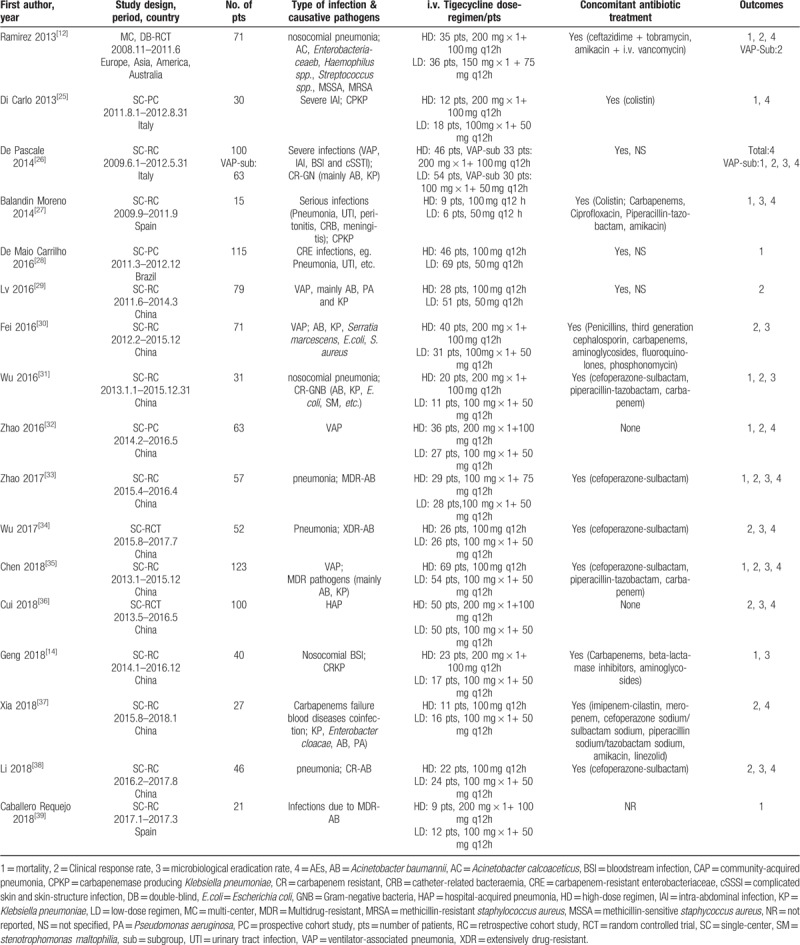

3.2. All-cause mortality

Eleven studies[12,14,25–28,31–33,35,39] reporting mortality were included for analysis. All-cause mortality for patients treated with HD tigecycline was significantly lower than LD (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.53–0.84, 11 studies, 629 patients) without significant heterogeneity (P = .30, I2 = 15%). Subgroup analyses by country showed similar result in Chinese study (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.41–0.75), while studies in other countries presented no significant difference (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.56–1.14) (Fig. 2A). Compared with LD regimen, all-cause mortality significantly decreased in HD regimen for subgroup of VAP (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.45–0.83), nosocomial pneumonia (RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.22–0.81) and intra-abdominal infection (RR 0.14, 95% CI 0.02–0.92), while bloodstream infection subgroup showed no statistical significance (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.43–1.09) (Fig. 2B). Sensitivity analysis excluding two different dose regimen studies[12,33] was consistent (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.53–0.87).

Figure 2.

A. All-cause mortality. The analysis is subcategorized by country. RR < 1.0 suggests decreased mortality with HD tigecycline treatment. B. All-cause mortality. The analysis is subcategorized by infection type. RR < 1.0 suggests decreased mortality with HD tigecycline treatment. BSI = bloodstream infection, HD = high-dose, IAI = intra-abdominal infection, LD = low-dose, RR = risk ratio, VAP = ventilator-associated pneumonia.

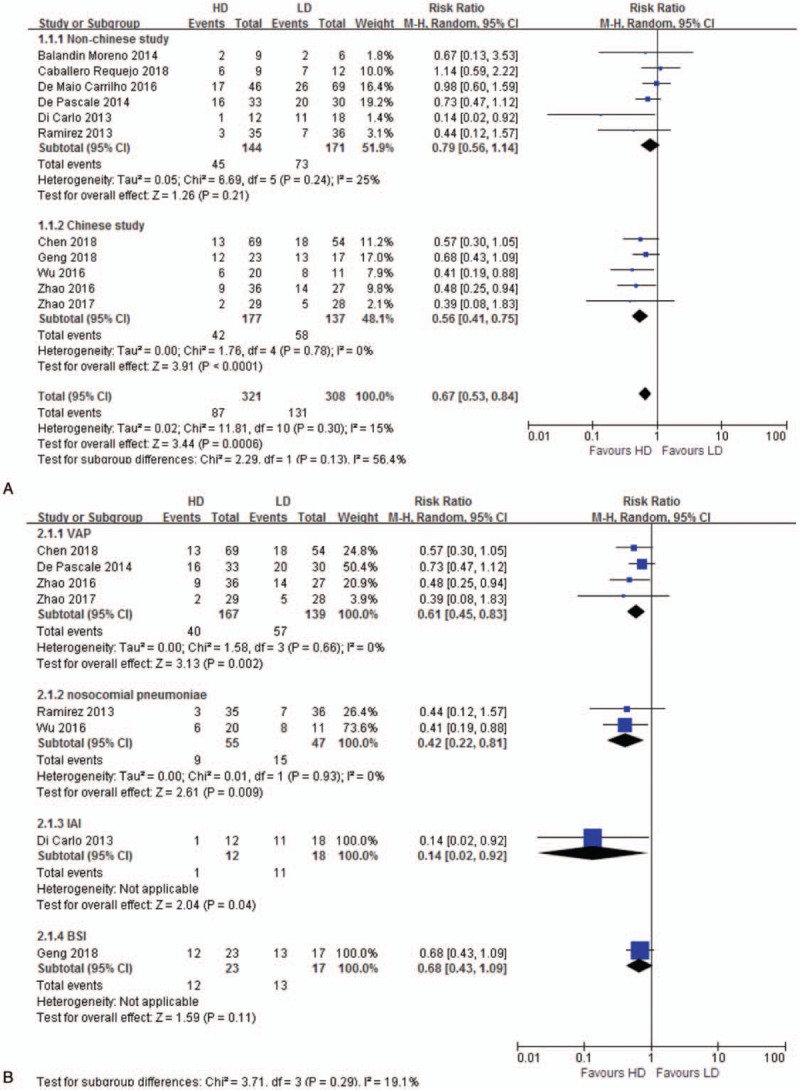

3.3. Clinical response rate

Twelve studies[12,26,29–38] reporting clinical response rate were included for analysis. Clinical response rate of HD regimen was significantly higher than LD (RR 1.46, 95% CI 1.30–1.65, 12 studies, 755 patients) without significant heterogeneity (P = .37, I2 = 8%). Subgroup analyses by country showed similar result in Chinese study (RR 1.49, 95% CI 1.30–1.70), while studies in other countries presented a negative result (RR 1.35, 95% CI 0.96–1.92) (Fig. 3A). Clinical response rate of HD regimen in subgroup of VAP (RR 1.55, 95% CI 1.32–1.82) and nosocomial pneumonia (RR 1.40, 95% CI 1.19–1.64) increased significantly than LD regimen (Fig. 3B). Sensitivity analysis excluding 2 different dose regimen studies[12,33] was consistent (RR 1.53%, 95% CI 1.34–1.76).

Figure 3.

A. Clinical response. The analysis is subcategorized by country. RR > 1.0 suggests increased clinical response with HD tigecycline treatment. B. Clinical response. The analysis is subcategorized by infection type. RR > 1.0 suggests increased clinical response with HD tigecycline treatment. HD = high-dose, LD = low-dose, RR = risk ratio, VAP = ventilator-associated pneumonia.

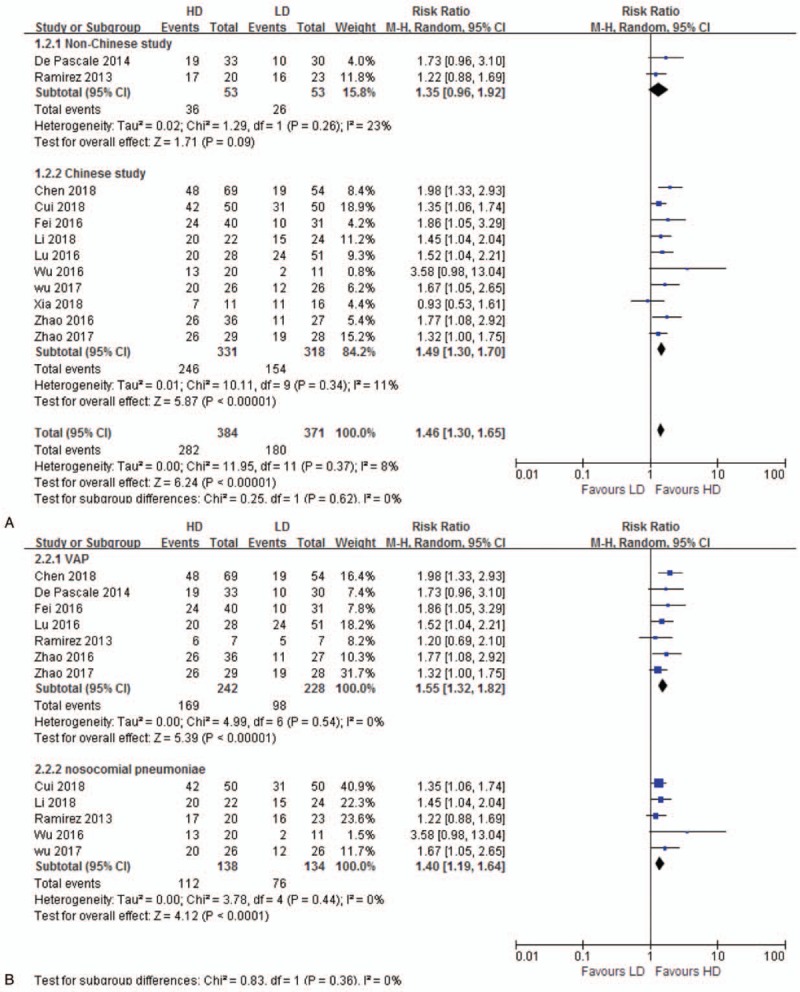

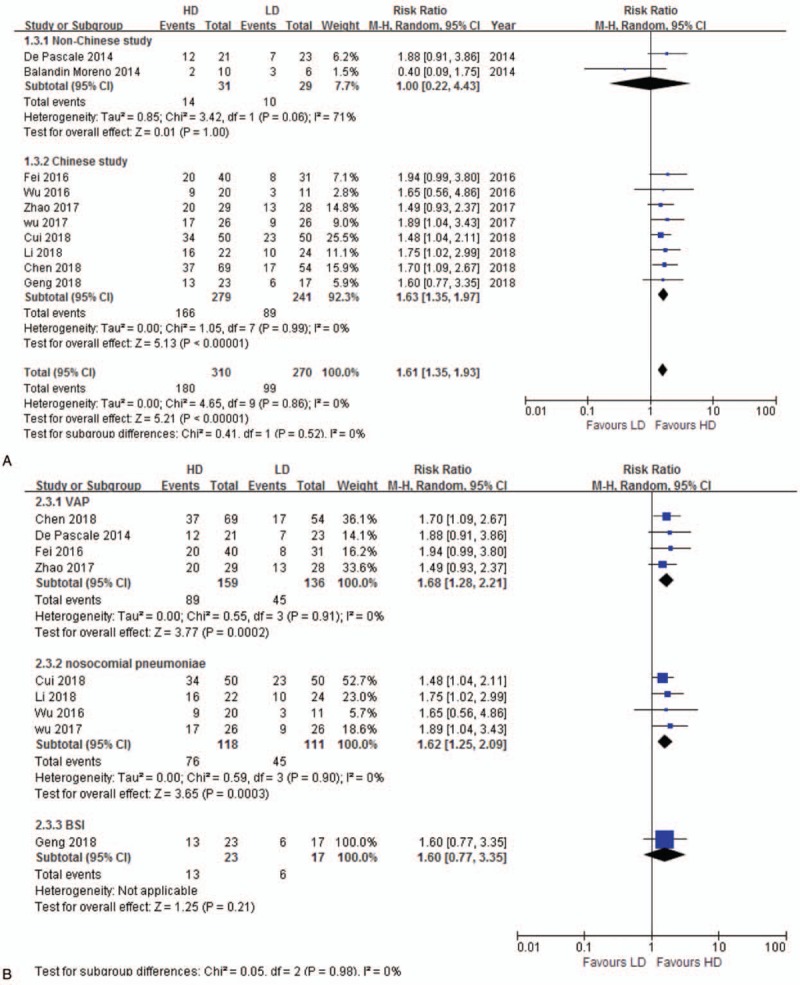

3.4. Microbiological eradication rate

Ten studies[14,26,27,30,31,33–36,38] reported microbiological eradication rate were included for analysis. Microbiological eradication rate of HD regimen was significantly higher than LD (RR 1.61, 95% CI 1.35–1.93, 10 studies, 580 patients) without significant heterogeneity (P = .86, I2 = 0%). Subgroup analyses by country showed similar result in Chinese study (RR 1.63, 95% CI 1.35–1.97), while studies in other countries presented a negative result (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.22–4.43) (Fig. 4A). HD tigecycline had a higher microbiological eradication efficiency in subgroup of VAP (RR 1.68, 95% CI 1.28–2.21) and nosocomial pneumonia (RR 1.62, 95% CI 1.25–2.09), but bloodstream infection subgroup showed no statistical significance (RR 1.60, 95% CI 0.77–3.35) (Fig. 4B). Sensitivity analysis excluding one different dose regimen study[33] was consistent (RR 1.63% 95% CI 1.35–1.99). There existed a high heterogeneity in non-Chinese subgroup analysis (P = .06, I2 = 71%), which might be induced by the opposite clinical result of the 2 included studies.[26,27]

Figure 4.

A. Microbiological eradication. The analysis is subcategorized by country. RR > 1.0 suggests increased microbiological eradication with HD tigecycline treatment. B. Microbiological eradication. The analysis is subcategorized by infection type. RR > 1.0 suggests increased microbiological eradication with HD tigecycline treatment. BSI = bloodstream infection, HD = high-dose, LD = low-dose, RR = risk ratio, VAP = ventilator-associated pneumonia.

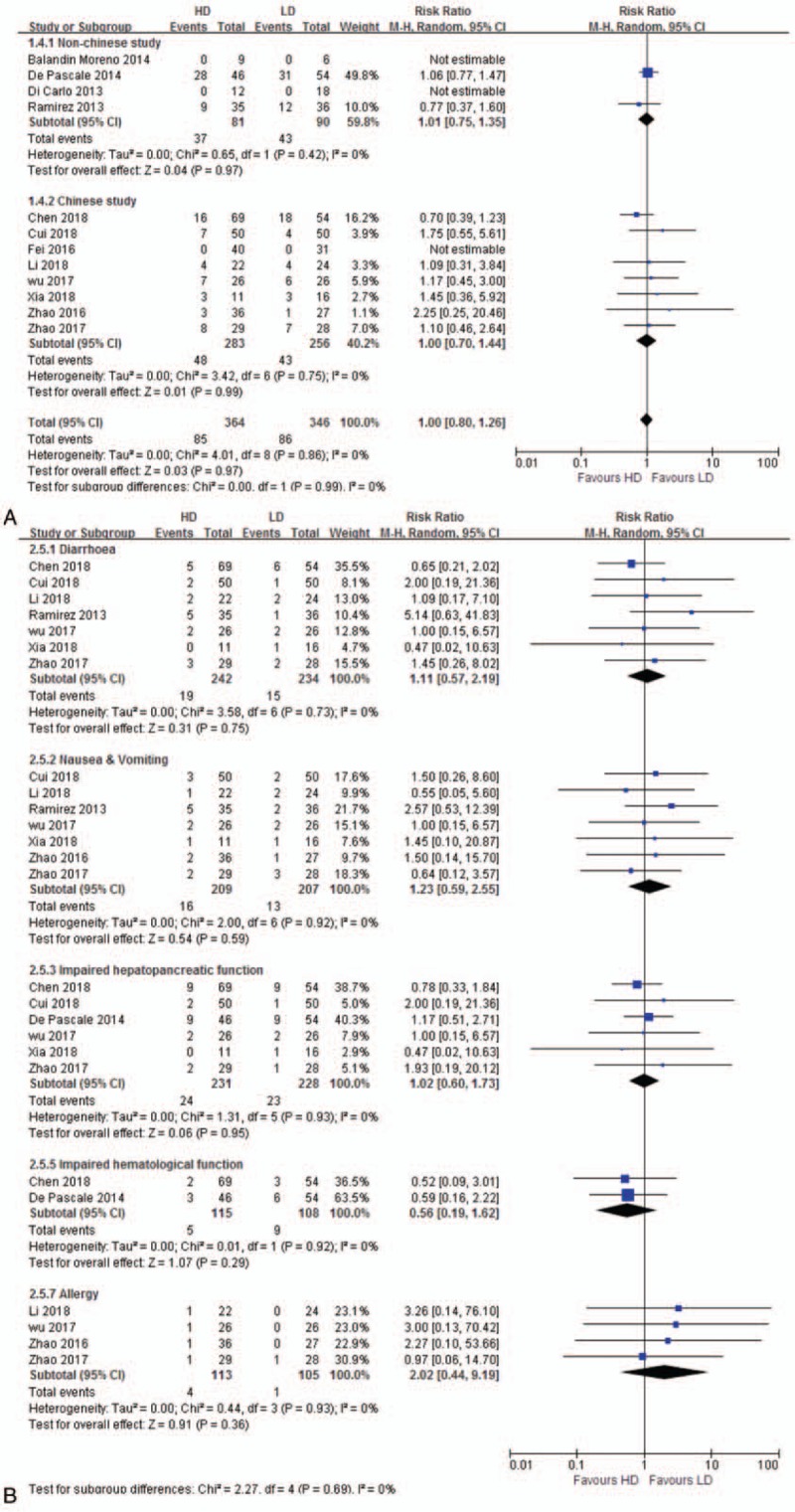

3.5. AEs

Twelve studies[12,25–27,30,32–38] reported AEs were included for analysis. Averse events between HD and LD regimen was similar (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.80–1.26, 12 studies, 710 patients) without significant heterogeneity (P = .86, I2 = 0%). Subgroup analyses by country showed similar result in both Chinese study (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.70–1.44) and non-Chinese study (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.75–1.35) (Fig. 5A). Sensitivity analysis excluding 2 different dose regimen studies[12,33] was consistent (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.80–1.32). Further analysis showed that there was no difference between HD and LD in allergy, diarrhea, nausea/vomiting, hepatopancreatic, and hematological toxicity (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

A. Adverse events. The analysis is subcategorized by country. RR > 1.0 suggests more adverse events with HD tigecycline treatment. B. Adverse events. The analysis is subcategorized by manifestation. RR > 1.0 suggests more adverse events with HD tigecycline treatment. HD = high-dose, LD = low-dose, RR = risk ratio .

4. Discussion

Recently, the increasing risk of MDR/XDR organisms propelled the use of tigecycline either in approved indications or off-label uses and high-dose regimen was resorted to be an approach for serious infections. We conducted a meta-analysis of all available studies comparing high and low dose tigecycline regimen. The pre-defined primary outcome was all-cause mortality. We found a statistically significant decrease in all-cause mortality with HD tigecycline. The RR for mortality was 0.67, denoting a 33% decrease in mortality, the 95% CI ranging between a 16% and 47% increase, different infection type presented no discrepancy. Pooled analysis of non-Chinese study also showed a mortality decrease by 21% but without significant difference.

We found a statistically significant increase of clinical response and microbiological eradication efficiency with HD vs LD tigecycline. Although no significant difference was observed in non-Chinese subgroup, the trend of improved efficacy (RR >1) was consistent. We speculated that the non-significant advantage of HD regimen might due to the different situation of bacterial resistance between Chinese and non-Chinese countries.

FDA stated a “black box” warning[40] of higher mortality with tigecycline than comparators based on data from one meta-analysis.[7] Recent meta-analyses also suggested increased risk of death in patients receiving tigecycline compared with other antibiotics, particularly in patients with VAP.[41,42] Further interpretation considered the increased death probably was ascribed to decreased clinical and microbiological efficacy.[7] Knowledge on PK/PD of tigecycline has been questioned and updated during recent years[21,43–45] Many studies and experts suggested dose adjustment of tigecycline based on the indication, pathogens and their susceptibility, PK targets and etc.[46,47] A higher dose regimen might be a solution to treat infections caused by pathogens for which therapeutic options are currently lacking.[48] PK/PD relationships for efficacy evaluation suggested treatment failure of tigecycline for HAP was related to a low fAUC0–24: MIC.[49] A double-blind randomized study of patients with HAP/VAP compared 2 different doses of tigecycline. Numerically higher efficacy values were observed with the high dose regimen.[12] Other case series studies reported the use of HD tigecycline in infections caused by carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae with a favorable result.[50] The results observed in our meta-analysis are consistent with the above findings.

In our meta-analysis, HD tigecycline did not elevated the risk of AEs, however a minor increase was seen in non-Chinese subgroup analysis (RR >1) with no statistical significance. Other systematic analysis indicated more AEs with HD tigecycline.[51] Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea are still the most common AEs,[40,52] nevertheless, reports on tigecycline related coagulopathy and hypofibrinogenemia are increasing;[53–55] Tigecycline could change series of coagulation parameters, including prolonged prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, thrombin time, and decreased fibrinogen, especially obvious in patients receiving higher dose.[56–59] Tigecycline induced coagulation disorders usually could be reversed after promptly discontinuation. Routine strict monitoring of coagulation parameters in patients receiving tigecycline, particularly when given at high dose and/or will last for a longer duration.

Limitations of our analysis include missing data of a negative results study,[24] we tried to obtain detail data by contacting with the author for several times but failed. Only one high-quality RCT study and 3 prospective cohort studies were available, others were all retrospective cohort studies. Most available studies were from European and China, with the latter predominating. Additionally, in most included studies, tigecycline was used in combination with other systematic antibiotics, and concomitant antibiotics were various.

5. Conclusions

HD tigecycline regimen was safe and effective in patients with serious infections caused by MDR/XDR pathogens. It should be a choice for serious infections with closely monitoring of AEs. Furthermore, well-designed studies especially RCTs from more different countries are required to establish the effectiveness and safety of HD tigecycline.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Hai Yu, Zhiqiang Sun, Guangjun Liu.

Data curation: Jinhong Gong, Guantao Du, Ying Lin, Zhiqiang Sun.

Formal analysis: Jinhong Gong, Jingjing Shang, Zhiqiang Sun.

Funding acquisition: Jinhong Gong, Dan Su, Jingjing Shang.

Methodology: Jinhong Gong, Zhiqiang Sun, Guangjun Liu.

Validation: Dan Su, Zhiqiang Sun, Guangjun Liu.

Writing – original draft: Jinhong Gong.

Writing – review & editing: Hai Yu, Zhiqiang Sun.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AEs = adverse events, CI = confidence intervals, HAP = hospital-acquired pneumonia, HD = high-dose, LD = low-dose, MDR = Multidrug-resistant, PK/PD = pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic, RR = risk ratios, VAP = ventilator-associated pneumonia, XDR = extensively drug-resistant.

How to cite this article: Gong J, Su D, Shang J, Yu H, Du G, Lin Y, Sun Z, Liu G. Efficacy and safety of high-dose tigecycline for the treatment of infectious diseases. Medicine 2019;98:38(e17091).

This work was supported by the Sci & Tech Development Foundation of Nanjing Medical University (NMUB2018061).

All authors declared that there was no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Kanj SS, Kanafani ZA. Current concepts in antimicrobial therapy against resistant gram-negative organisms: extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, and multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mayo Clinic Proc 2011;86:250–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Eckmann C, Dryden M. Treatment of complicated skin and soft-tissue infections caused by resistant bacteria: value of linezolid, tigecycline, daptomycin and vancomycin. Eur J Med Res 2010;15:554–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zhanel GG, Homenuik K, Nichol K, et al. The glycylcyclines: a comparative review with the tetracyclines. Drugs 2004;64:63–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Stein GE, Babinchak T. Tigecycline: an update. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2013;75:331–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ni WT, Han YL, Liu J, et al. Tigecycline treatment for carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Freire AT, Melnyk V, Kim MJ, et al. Comparison of tigecycline with imipenem/cilastatin for the treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2010;68:140–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Yahav D, Lador A, Paul M, et al. Efficacy and safety of tigecycline: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011;66:1963–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Meagher AK, Ambrose PG, Grasela TH, et al. The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile of tigecycline. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41Suppl 5:S333–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Barbour A, Schmidt S, Ma B, et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of tigecycline. Clin Pharmacokinet 2009;48:575–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bassetti M, Peghin M, Pecori D. The management of multidrug-resistant enterobacteriaceae. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2016;29:583–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Poulakou G, Bassetti M, Righi E, et al. Current and future treatment options for infections caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens. Future Microbiol 2014;9:1053–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ramirez J, Dartois N, Gandjini H, et al. Randomized phase 2 trial to evaluate the clinical efficacy of two high-dosage tigecycline regimens versus imipenem-cilastatin for treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013;57:1756–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].De Pascale G, Montini L, Spanu T, et al. High-dose tigecycline use in severe infections [abstract P80]. In: 33rd International Symposium on Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine, Brussels, Belgium. Crit Care 2013;17Suppl 2:S29. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Geng TT, Xu X, Huang M. High-dose tigecycline for the treatment of nosocomial carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infections. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e9961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Barza M, Trikalinos TA, Lau J. Statistical considerations in meta-analysis. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2009;23:195–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2003;327:557–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gandjini H, McGovern PC, Yan JL, et al. Clinical efficacy of two high tigecycline dosage regimens vs. imipenem/cilastatin in hospital-acquired pneumonia: Results of a randomised phase II clinical trial. Clin Microbiol Infec 2012;18Suppl 3:64.22862799 [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lou Y, Shi XY. Clinical study of high dose tigecycline on ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by multi-drug resistant gram-negative bacilli. Chin J Emerg Med 2015;24:1267–71. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Balandin Moreno B, Fernandez Simon I, Romera Ortega MA, et al. Clinical experience with tigecycline in intensive care unit [abstract]. In: 24th Annual Congress of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM), Berlin, Germany. Intens Care Med 2011;37Suppl 1:S266. [Google Scholar]

- [20].De Pascale G, Montini L, Bernini V, et al. Tigecycline use in critically ill patients. Do we need higher doses? [abstract]. In: 25th Annual Congress of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM), Lisbon, Portugal. Intens Care Med 2012;38Suppl 1:S82. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Baron J, Cai S, Klein N, et al. Once daily high dose tigecycline is optimal: Tigecycline PK/PD parameters predict clinical effectiveness. J Clin Med 2018;7:e49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gao HH, Yao ZL, Li Y, et al. Safety and effectiveness of high dose tigecycline for treating patients with acute leukemia after ineffctiveness of carbapenems chemotherapy combinating with febrile neutropenia: retrospective study. Zhongguo Shi Yan Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi 2018;26:684–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zang HL, Wang SC, Cheng H. Clinical effect of high dose tigecycline on ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by multi-drug resistant bacteria. Zhongguo Yi Yao 2018;13:380–2. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Jesus R, Pablo PH, Esther V, et al. Analysis of treatment failure with standard and high dose of tigecycline in critically ill patients with multidrug-resistant bacteria. Eur J Clin Pharm 2017;19:93–9. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Di Carlo P, Gulotta G, Casuccio A, et al. KPC - 3 Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 clone infection in postoperative abdominal surgery patients in an intensive care setting: Analysis of a case series of 30 patients. BMC Anesthesiol 2013;13:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].De Pascale G, Montini L, Pennisi MA, et al. High dose tigecycline in critically ill patients with severe infections due to multidrug-resistant bacteria. Crit Care 2014;18:R90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Balandin Moreno B, Fernandez Simon I, Pintado Garcia V, et al. Tigecycline therapy for infections due to carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in critically ill patients. Scand J Infect Dis 2014;46:175–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].de Maio Carrilho CMD, de Oliveira LM, Gaudereto J, et al. A prospective study of treatment of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections and risk factors associated with outcome. BMC Infect Dis 2016;16:629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].LV XC, Cai GL, Xu QH. Observation of the clinical efficacy of tigecycline for treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill elderly patients. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2016;96:535–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Fei M, Zhang M, Cai W. Efficacy and safety of high dose tigecycline in treatment of patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chin J Clin Infect Dis 2016;9:416–21. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wu XM, Zhu YF, Chen QY, et al. Tigecycline therapy for nosocomial pneumonia due to carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteria in critically ill patients who received inappropriate initial antibiotic treatment: a retrospective case study. Biomed Res Int 2016;2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Zhao GY. Clinical study on tigecycline for the treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill elderly patients. Zhongguo Ji Xu Yi Xue Jiao Yu 2016;8:119–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Zhao ZH, Wang XL, Ma ZQ. Clinical study on off-label use of tigecycline combined with cefoperazone and sulbactam in the treatment of pneumonia caused by multidrug-resistant acinetobacter baumannii. J China Pharm 2017;28:201–4. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Wu YH, Yang YY, Gao XH. The clinical analysis of different doses of tigecycliue in the treatment of severe pneumonia caused by extensively-drug resistant acinetobacter baumannii. Zhongguo Wei Sheng Biao Zhun Guan Li 2017;8:104–7. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Chen ZH, Shi XY. Adverse events of high-dose tigecycline in the treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia due to multidrug-resistant pathogens. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e12467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Cui N, Yang LZ, Yu ZB, et al. Comparative effects among different doses of tigecycline and imipenem cilastatin in treating hospital acquired pneumonia. Zhongguo Yao Ye 2018;27:62–4. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Xia L, Bao J, Xia RX. Efficacy and safety of salvage tigecycline in severe infection with haematological disorders. Anhui Yi Xue 2018;39:1109–11. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Li ZH, Zhang H, Gao YQ. Study on tigecycline in the treatment of pneumonia patients with carbapenems-resistant acinetobacter baumannii. Zhongguo shi yong yi kan 2018;45:99–101. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Caballero Requejo C, Gil Candel M, Gallego Munoz C, et al. High dosage of tigecycline in multidrug resistant acinetobacter baumannii: Use analysis during an outbreak. Eur J Hosp Pharm Sci Pract 2018;25Suppl 1:A179–80. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Inc. WP. TYGACIL (tigecycline) for injection for intravenous use (highlights of prescribing information). Available at: http://labelingpfizercom/ShowLabelingaspx?id=491 Accessed October 31, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Prasad P, Sun J, Danner RL, et al. Excess deaths associated with tigecycline after approval based on noninferiority trials. Clin Infect Dis 2012;54:1699–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Cai Y, Wang R, Liang BB, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness and safety of tigecycline for treatment of infectious disease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011;55:1162–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Xie J, Wang TT, Sun JY, et al. Optimal tigecycline dosage regimen is urgently needed: results from a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic analysis of tigecycline by Monte Carlo simulation. Int J Infect Dis 2014;18:62–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Cunha BA, Baron J, Cunha CB. Once daily high dose tigecycline - pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic based dosing for optimal clinical effectiveness: dosing matters, revisited. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2017;15:257–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Deitchman AN, Singh RSP, Derendorf H. Nonlinear protein binding: not what you think. J Pharm Sci 2018;107:1754–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Giamarellou H, Poulakou G. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluation of tigecycline. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2011;7:1459–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Borsuk-De Moor A, Rypulak E, Potrec B, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of high-dose tigecycline in patients with sepsis or septic shock. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018;62:e02273–2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Xie J, Roberts JA, Alobaid AS, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of tigecycline in critically ill patients with severe infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017;61:e00345–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Bhavnani SM, Rubino CM, Hammel JP, et al. Pharmacological and patient-specific response determinants in patients with hospital-acquired pneumonia treated with tigecycline. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012;56:1065–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Sbrana F, Malacarne P, Viaggi B, et al. Carbapenem-sparing antibiotic regimens for infections caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae in intensive care unit. Clin Infect Dis 2013;56:697–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Xu L, Wang YL, Du S, et al. Efficacy and safety of tigecycline for patients with hospital-acquired pneumonia. Chemotherapy 2016;61:323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Rello J. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, safety and tolerability of tigecycline. J Chemother 2005;17Suppl 1:12–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Sabanis N, Paschou E, Gavriilaki E, et al. Hypofibrinogenemia induced by tigecycline: a potentially life-threatening coagulation disorder. Infect Dis (Lond) 2015;47:743–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Bourneau-Martin D, Crochette N, Drablier G, et al. Hypofibrinogenemia complicated by hemorrhagic shock following prolonged administration of high doses of tigecycline [Abstract]. In: 20th Annual Meeting of French Society of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 37th Pharmacovigilance Meeting, 17th APNET Seminar, 14th CHU CIC Meeting. France Fundam Clin Pharmacol 2016;30Suppl 1:29. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Yilmaz Duran F, Yildirim H, Sen EM. A lesser known side effect of tigecycline: hypofibrinogenemia. Turk J Haematol 2018;35:83–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Pieringer H, Schmekal B, Biesenbach G, et al. Severe coagulation disorder with hypofibrinogenemia associated with the use of tigecycline. Ann Hematol 2010;89:1063–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Zhang Q, Zhou SM, Zhou J. Tigecycline treatment causes a decrease in fibrinogen levels. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015;59:1650–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Routsi C, Kokkoris S, Douka E, et al. High-dose tigecycline-associated alterations in coagulation parameters in critically ill patients with severe infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2015;45:90–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Wu XQ, Zhao P, Dong L, et al. A case report of patient with severe acute cholangitis with tigecycline treatment causing coagulopathy and hypofibrinogenemia. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e9124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]