Abstract

As a dynamic post-translational modification, O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) modification (i.e., O-GlcNAcylation) of proteins regulates many biological processes involving cellular metabolism and signaling. However, O-GlcNAc site mapping, a prerequisite for site-specific functional characterization, has been a challenge since its discovery. Herein we present a novel method for O-GlcNAc enrichment and site mapping. In this method, the O-GlcNAc moiety on peptides was labeled with UDP–GalNAz followed by copper-free azide–alkyne cycloaddition with a multifunctional reagent bearing a terminal cyclooctyne, a disulfide bridge, and a biotin handle. The tagged peptides were then released from NeutrAvidin beads upon reductant treatment, alkylated with (3-acrylamidopropyl)trimethylammonium chloride, and subjected to electron-transfer dissociation mass spectrometry analysis. After validation by using standard synthetic peptide gCTD and model protein α-crystallin, such an approach was applied to the site mapping of overexpressed TGF-β-activated kinase 1/MAP3K7 binding protein 2 (TAB2), with four O-GlcNAc sites unambiguously identified. Our method provides a promising tool for the site-specific characterization of O-GlcNAcylation of important proteins.

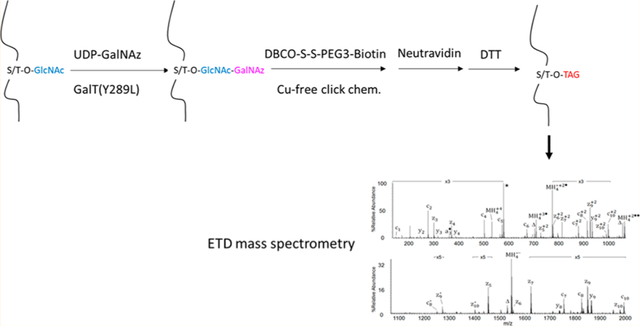

Graphical Abstract

As a dynamically regulated post-translational modification (PTM), O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) modification occurs on serine and threonine residues of proteins.1,2 After over 30 years’ endeavor, O-GlcNAcylation has been found on a myriad of proteins localized in the cytosol, nucleus, and mitochondria.3–5 O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) adds the O-GlcNAc moiety onto target proteins, while O-GlcNAcase removes it. Protein O-GlcNAcylation plays important roles in almost all biochemical processes examined (e.g., DNA transcription, mRNA translation, protein turnover, regulation of cellular responses to hyperglycemia and starvation/fasting, and stress protection). Besides serving as a nutrient sensor integrating cellular metabolism, protein O-GlcNAcylation is a crucial mediator in multiple signaling pathways.

Although much progress has been made to study O-GlcNAc, its site mapping is still a challenging task by using standard mass spectrometric methods.6–8 On one hand, the GlcNAc moiety easily falls off from the peptide backbone in collisionally activated dissociation (CAD) mass spectrometry (MS), which is commonly employed in traditional mass spectrometers, leading to largely failed assignment of modification sites. This approach has been demonstrated successfully by combination with techniques that can convert the glycosidic bond to a CAD-stable covalent bond (e.g., by using β-elimination followed by Michael addition with dithiothreitol (BEMAD), O-GlcNAc modified peptides can be converted to the corresponding DTT-substituted peptides).9–12 In contrast, the recently introduced electron-transfer dissociation (ETD) preserves the labile moiety onto peptides, enabling facile and direct assignment of modification sites.13 On the other hand, enrichment is often a perquisite step prior to the mass spectrometric analysis, as a result of the severe ion suppression by non-O-GlcNAc peptides.6,8 To this end, several enrichment approaches have been developed to facilitate O-GlcNAc detection by mass spectrometry. Lectins (e.g., Ricinus communis agglutinin I (RCA I) and wheat germ agglutinin (WGA)) have been used in the enrichment of O-GlcNAc peptides.14–18 To improve the enrichment efficiency, long columns packed with WGA resin were used to retard the retention of O-GlcNAc peptides, with the retained fraction usually subjected to several rounds of further enrichment with the same column. Although suffering from relatively low affinity, O-GlcNAc-specific antibody enrichment has also been used to pull down O-GlcNAc proteins.19–21 It is still a challenging task to map the sites on putative target proteins. Recently, it has been demonstrated feasible to perform enrichment at the O-GlcNAc peptide level with several newly developed antibodies.22,23 However, the enrichment efficiency of the proposed method is still to be further validated. Moreover, the integration of chemoenzymatic labeling, streptavidin enrichment, and MS analysis has been exploited as an efficient approach for O-GlcNAc site mapping.24–27 In this approach, using a GalT mutant (GalTl), the O-GlcNAc moiety of peptides is specifically labeled with GalNAc analogues (e.g., azido-substituted form) that enable selective biotinylation (usually by using copper-catalyzed azido–alkyne-mediated click chemistry). After being captured by streptavidin/NeutrAvidin beads, O-GlcNAc-tagged peptides can be released and analyzed by mass spectrometry. As an alternative, cell-culture-based metabolic labeling (by feeding cells with peracetylated azido/alkyne analogues) has also been coupled with click-chemistry-based enrichment and mass spectrometry for O-GlcNAc site mapping.28–31 Of note, although relatively more chemical reaction steps are required, approaches integrating chemoenzymatic or metabolic labeling with click chemistry provide higher affinity and specificity toward O-GlcNAc proteins/peptides.

Our previous work for O-GlcNAc site mapping by using chemoenzymatic labeling, copper-catalyzed click chemistry, and UV cleavage has been a success.25–27 Aiming to further simplify the experimental procedures and improve the enrichment robustness, we present a method for O-GlcNAc site mapping by combining chemoenzymatic labeling, copper-free click chemistry, reductive cleavage, and ETD-MS analysis. Specifically, the O-GlcNAc moiety on peptides is labeled with UDP–GalNAz followed by copper-free azide–alkyne cycloaddition with a multifunctional reagent bearing a terminal cyclooctyne, a disulfide bridge, and a biotin handle. The tagged peptides are then released from NeutrAvidin beads upon reductant treatment, alkylated with (3-acrylamidopropyl)trimethylammonium chloride, and subjected to ETD-MS analysis. After being tested with a standard synthetic peptide gCTD and model protein α-crystallin, this method was then applied to the O-GlcNAc site mapping of overexpressed TAB2, a crucial scaffold protein involved in multiple cellular signal pathways. Our results demonstrate that such a method will be a useful addition to the toolbox for the comprehensive characterization of O-GlcNAc sites of important proteins.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials.

α-Crystallin was ordered from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Overexpressed GFP–TAB2 was immuno-purified from HEK293A cells by Chromotek GFP-Trap agarose beads (Allele Biotech, CA). The SDS–PAGE gel band corresponding to GFP–TAB2 was cut out and digested.32 gCTD (YSPTgSPS, gS = O-GlcNAcylated Ser) and other chemicals and procedures are described in detail in Supplementary Methods.

Chemoenzymatic Labeling, Copper-Free Click Chemistry, Reductive Cleavage, and Derivatization of O-GlcNAc Peptides.

α-Crystallin was reduced with DTT, alkylated with iodoacetamide, digested with trypsin, and desalted with a C18 column, as described previously.33 O-GlcNAc peptides from α-crystallin and TAB2 were enriched with a combination of chemoenzymatic labeling, copper-free click chemistry, and a reductive cleavage approach (Figure l). Specifically, gCTD, α-crystallin digest, and TAB2 digest in 100 μ/L of 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.9) were chemoenzymatically labeled by incubating overnight with UDP–GalNAz (25 μL; Life Technologies) and GalT1 mutant (15 μL; Life Technologies) in the presence of 22 μL of MgCl2 (Life Technologies) at 4 °C, according to the manufacturer instructions and our previous papers.25–27 Calf intestine phosphatase (20 U; New England Biolabs) was then added and incubated for 3 h at room temperature. Excess UDP– GalNAz was removed by desalting with a C18 spin column (Nest Group). Copper-free click chemistry was performed in 15 μL of PBS and 4 μL of 1 mM DBCO–S–S–PEG3–biotin (predissolved in DMSO; Click Chemistry Tools LLC) for 2 h at room temperature. NeutrAvidin beads were added with gentle shaking for 2 h. After an extensive wash, the resin was treated with 20 mM DTT for 30 min at 37 °C, with the released peptides desalted with a C18 spin column. The peptides were immediately derivatized with 3-acrylamidopropyl)trimethylammonium chloride (APTA, 500 mM) for 2 h in the dark.34 After being desalted with a C18 spin column and dried with a Speed Vac, peptides were analyzed by MALDI-TOF or LC/MS/MS.

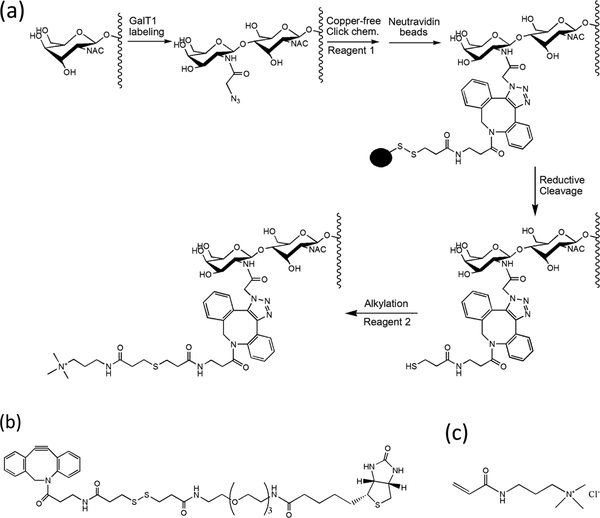

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic for the enrichment of O-GlcNAc peptides with chemoenzymatic labeling, copper-free click chemistry, and reductant-cleavable DBCO–S–S–PEG3–biotin. (b,c) The structures of Reagent 1 (i.e., DBCO–S–S–PEG3–biotin) and Reagent 2 (i.e., APTA).

MALDI-TOF Analysis of Tagged gCTD.

A Voyager time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Perseptive Biosystems) with a 337 nm nitrogen laser was used to monitor the O-GlcNAc tagging steps. In brief, a saturated solution of 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB) in acetonitrile/water (1:1, v/v) was used as the matrix. A 0.5 μL aliquot of sample from each step in the gCTD enrichment procedure was mixed with an equal volume of the matrix solution, which was then loaded on a sample plate. Mass spectra were obtained with the mass spectrometer operated in linear mode.

LC/MS/MS Analysis of Enriched O-GlcNAc Peptides.

For reversed-phase liquid chromatography tandem MS (LC/MS/MS) analysis, a fraction of the enriched O-GlcNAc peptides was pressure-loaded onto a precolumn (360 μm o.d. × 75 μm i.d. fused silica capillary) packed with 7 cm of C18 reverse-phase resin (5 μm diameter, 120 Å pore size, Reprosil-Pur, Dr. Maisch GmbH, Germany). The precolumn was desalted by rinsing with 0.1 M acetic acid, followed by connecting it to an analytical column (360 μm o.d. × 50 μm i.d.) packed with 12 cm of C18 reverse-phase resin (3 μm. diameter, 120 Å pore size, Reprosil-Pur) and equipped with an electrospray emitter tip.35 The peptides were eluted at a flow rate of 60 nL/min using the following gradient: 0–60% B for 60 min, 60–100% B for 5 min, 100% B for 5 min (solvent A: 0.1 M acetic acid in water; solvent B: 70% acetonitrile and 0.1 M acetic acid in water). Full MS (MS1) analyses were acquired in high-resolution Fourier transform mass analyzers (Orbitrap XL or Orbitrap Elite) in LTQ-Orbitrap hybrid instruments (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany), whereas MS2 spectra were acquired in linear ion traps of an LTQ-Orbitrap using collisionally activated dissociation (CAD) and front end ETD.36 MS analyses were completed using a method consisting of one high-resolution MS1 scan (resolving power of 60 000 at m/z 400) followed by 10 data-dependent low-resolution MS2 scans (5 for CAD and 5 for ETD) acquired in the LTQ ion trap. Data-dependence parameters were set as follows: repeat count of 2, repeat duration of 15 s, exclusion list duration of 20 s. ETD MS2 parameters were set as follows: 35 ms reaction time, 3 m/z precursor isolation window, charge state rejection “on” for +1 and unassigned charge state precursor ions, 5 × 105 FTMS full automated gain control target, 1 × 104 ITMSn automated gain control target, 2 × 105 reagent ion target with azulene as the electron-transfer reagent.

Mass Spectrometric Data Analysis.

In-house developed software was used to generate peak lists and to remove charge reduction species.35 The Open Mass Spectrometry Search Algorithm (OMSSA, version 2.1.8) was utilized to search c-and z-type fragment ions present in ETD-MS/MS spectra against a database containing the target protein (either human TAB2 (NCBI accession number Q9NYJ8) or bovine α-crystallin A chain (accession number P02470) and B chain (accession number P02510)). Database searches used trypsin as enzyme specificity (allowing three missed cleavages) and included the following variable modifications: carbamidomethyl on Cys, oxidation on Met, and tagged HexNAc (+981.4 Da) on Ser and Thr. A precursor mass tolerance of ±0.01 Da was used for MS1 data, and a fragment ion mass tolerance of ±0.35 Da was used for MS2 data. All identified peptide sequences were manually validated by inspection of the accurate precursor mass and the corresponding ETD spectra.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Development of an O-GlcNAc Site-Mapping Method Integrating Chemoenzymatic Labeling, Copper-Free Click Chemistry, Reductive Cleavage, and Derivatization.

The whole procedure is shown in Figure 1a. Chemoenzymatic labeling represents a powerful approach for the activation of the “chemically inert” O-GlcNAc moiety.24–27 Indeed, the O-GlcNAc moiety (rather than others) is specifically labeled with GalNAz by GalT1. The tagged GalNAz selectively reacts with alkyne-containing reagents via the copper-catalyzed azide–alkyne [3 + 2] cycloaddition (i.e., Cu+-catalyzed click chemistry).24–27 In comparison to the traditional copper-catalyzed click chemistry, copper-free click chemistry has gained huge popularity in recent years,37,38 mainly because of the simplified reaction system (e.g., no Cu+-producing components needed) and largely quickened reaction dynamics. Moreover, the copper-free click chemistry has recently been shown applicable to the investigation of the O-GlcNAc status of proteins in cells fed with peracetylated azidogalactosamine (Ac4GalNAz) for imaging.39,40 To facilitate O-GlcNAc site mapping, a multifunctional reagent (Reagent 1, DBCO–S–S–PEG3–biotin) has been adopted in the current study (Figure 1b). The cyclooctyne moiety of the reagent renders selective reactivity toward GalNAz, while the biotin handle allows capture of tagged O-GlcNAc peptides onto NeutrAvidin beads. More importantly, the disulfide bond of the reagent enables mild release by reducing agents (e.g., DTT) The released peptides are then derivatized by APTA(Figure 1c), an alkylating reagent that imparts a permanent positive charge, increasing the charge state of peptides (>2), which benefits ETD analysis.

Validation of the Method with Standard O-GlcNAc Peptides and Proteins.

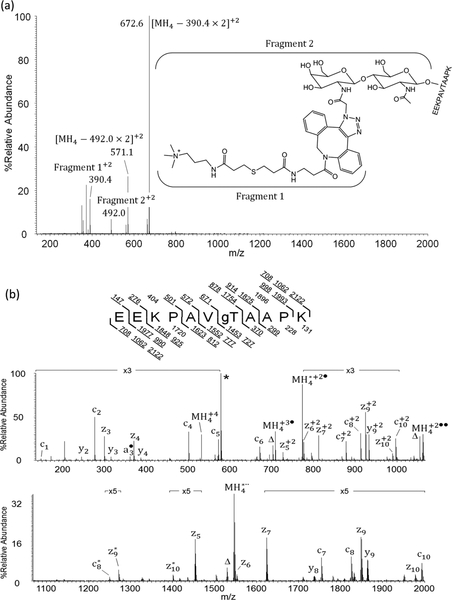

gCTD, a synthetic O-GlcNAc peptide (YSPTgSPS), was used to test the feasibility of our approach, with each step monitored by MALDI-TOF (Supporting Figure S1a–d). The GlcNAc peptide was tagged by GalNAz after GalT1 labeling, with a mass addition of 244.0 Da (Supporting Figure S1b). The further tagging with DBCO–S–S–PEG3–biotin and subsequent release with DTT gave a mass addition of 364.3 Da (Supporting Figure S1c). The derivatization by APTA yielded an additional 169.7 Da (Supporting Figure S 1d). In total, a mass increase of 981.4 Da was added onto the Ser/Thr residue of modified peptides. The enrichment approach was validated with α-crystallin, a protein with an extremely low abundance of O-GlcNAc peptides.41 After tryptic digestion, O-GlcNAc peptides were tagged with GalNAz followed by enrichment and derivatization, with the final product analyzed by both CAD and ETD-MS/MS using an LTQ–Orbitrap mass spectrometer. Shown in Figure 2a is the CAD spectrum recorded on [M+4H]+4 ions at m/z 531.5 from EEKPAVgTAAPK of α-crystallin. Note that the signals labeled as Fragment 1 and Fragment 2 are cleaved fragments at the glycosidic linkage in CAD, serving as diagnostic oxonium ions. Figure 2b shows the ETD spectrum recorded on [M+4H]+4 ions for the same peptide, with predicted fragment ions of types c and z shown above and below the inset, while those ions observed are underlined. As expected, the tag was well retained on the peptide fragments, allowing direct assignment of the O-GlcNAc site based on ETD fragment ions. The tagged form of another O-GlcNAc peptide (AIPVgSREEKPSSAPSS) of α-crystallin was also observed (data not shown).

Figure 2.

(a) CAD and (b) ETD-MS/MS spectra of the [MH4]+4 ions (m/z 531.5) of O-GlcNAc peptide EEKPAVgTAAPK (gT = O-GlcNAcylated Thr) enriched from α-crystallin. In the CAD spectrum (a), two +2 charged signature fragment ions at m/z 390.4 and 492.0 result from cleavage at the two sugar ketal linkages and confirm the presence of the tagged O-GlcNAc moiety. In the ETD spectrum (b), the predicted monoisotopic singly and selected average mass doubly charged c- and z-type fragment ion masses as well as the average mass of the precursor and charge-reduced precursor ions are listed above and below the peptide sequence, respectively. Observed c- and z-type fragment ions are underlined within the peptide sequence and allowed for the O-GlcNAc site localization at Thr. Unreacted precursor and charge-reduced precursor ions are labeled as MH4, and the ions resulting from neutral losses are labeled as Δ. The peak labeled with * correspond to the singly charged signature fragment ion, C30H39O3N7S+; dissociated from the modified tag upon ETD. Other ions with superscript * correspond to species due to loss of the signature fragment from other assigned ions.

O-GlcNAcylation of Endogenous TAB2.

TAB2, the binding protein 2 of TGF-α-activated kinase 1 (TAK1), is an upstream adaptor protein in the IL-1 signaling pathway and others in the regulation of multiple cellular processes (including inflammation).42–44 Although previous work found one O-GlcNAc site (i.e., T456) of TAB2,17,45 in total, four O-GlcNAc sites (i.e., S166, S350, S354, T456) were unambiguously identified from GFP-tagged TAB2 after in-gel digestion, enrichment, and ETD-MS/MS analysis in this study (Table 1). Next, we validated the O-GlcNAcylation of TAB2 both in vitro and in vivo (Supporting Figure S2). By exploiting the in vitro OGT labeling assay, the unglycosylated recombinant TAB2 protein (purified from E. coli) was found glycosylated by OGT in the cell-free system (Supporting Figure S2a), showing that TAB2 is a direct substrate for protein O-GlcNAcylation. Also, we confirmed the physiological interaction between TAB2 and OGT in cells by using coimmunoprecipitation (Supporting Figures S2b,c). In addition, treating cells with TMG, a specific inhibitor to O-GlcNAcase, increased the overall O-GlcNAcylation of TAB2. Meanwhile, treating cells with Ac4-S-GlcNAc, an inhibitor to OGT, decreased the O-GlcNAcylation, demonstrating a dynamical response of O-GlcNAcylation of TAB2 toward the pharmaceutical inhibition of O-GlcNAc cycling (Supporting Figure S3). These results indicate that O-GlcNAcylation of TAB2, which is tightly regulated, might be an important player controlling the activity of IL-1 signaling pathway and others. Ongoing site-specific mutation analysis will facilitate elucidation of functional roles of TAB2 O-GlcNAcylation.

Table 1.

O-GlcNAcylated Peptides and Sites of Endogenous TAB2a

| peptide sequence | AA start-stop | major charge state | OMSSA search | experimental m/z error (ppm) | manual verification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTSgSLSQQTPR | 163–173 | +3 | yes | 1 | 13 c- and z-ions in ETD |

| TSgSTSSSVNSQTLNR | 348–362 | +3 | yes | 2 | 13 c- and z-ions in ETD |

| TSgSTSSgSVNSQTLNR | 348–362 | +4 | no | 2 | 7 c- and z-ions, weak ETD |

| VVVgTQPNTK | 453–461 | +3 | yes | 1 | 12 c- and z-ions in ETD |

gS, O-GlcNAcylated Ser; gT, O-GlcNAcylated Thr.

CONCLUSION

In summary, here we present a refined method for O-GlcNAc site mapping by combining chemoenzymatic labeling, copper-free click chemistry, and ETD-MS analysis. Different from previous work,25–27,45 this procedure employs a novel reductant-cleavable biotin tag that allows for reliable and efficient release of the enriched O-GlcNAc peptides from the solid affinity support. The released peptides can be derivatized by –SH reactive reagents (e.g., APTA herein), allowing for the addition of positive charges and thus better fragment efficiency when subjected to ETD. Besides being used for the comprehensive site mapping of individual proteins, this method is directly applicable for complex samples, with which a cancer O-GlcNAc proteomics project is undergoing. Last but not least, peptides enriched with this method can also be subjected to BEMAD for CAD/HCD-based O-GlcNAc site mapping if an ETD-based mass spectrometer is not available (as exemplified in Zeiden, Q.; Ma, J.; Hart, G.W. Manuscript in preparation). It should be noted that, performing O-GlcNAc enrichment using chemoenzymatic labeling and click chemistry usually requires strong understanding of each reaction step and thus chemical expertise of investigators. However, the method herein with improved simplicity and robustness shall be facilely adopted by more biomedical laboratories for their research on the site-specific functional elucidation of biological functions of O-GlcNAc protein(s). Taken together, we believe this method will provide a useful tool to the repertoire for efficient site-specific characterization of important O-GlcNAcylated proteins individually and globally.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Hart lab for their great help. Stimulating discussions from sister laboratories of the NHLBI-Johns Hopkins Cardiac Proteomics Center and NHLBI-Program of Excellence in Glycosciences Center at Johns Hopkins are also appreciated. Research reported in this publication was supported by NIH N01-HV-00240, P01HL107153, R01DK61671, and R01GM116891 (to G.W.H.), NIH GM037537 (to D.F.H.), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NCSF) 81772962 (to Z.L.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.anal-chem.8b05688.

Additional Information as noted in text (PDF)

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): Dr. Hart receives a share of royalty received by the university on sales of the CTD 110.6 antibody, which are managed by the Johns Hopkins University.

REFERENCES

- (1).Torres CR; Hart GW J. Biol. Chem 1984, 259, 3308–3317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Holt GD; Hart GW J. Biol Chem 1986, 261, 8049–8057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Hart GW; Slawson C; Ramirez-Correa GA; Lagerlof O Annu. Rev. Biochem 2011, 80, 825–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Banerjee PS; Ma J; Hart GW Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2015, 112, 6050–6055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Ma J; Liu T; Wei AC; Banerjee P; O’Rourke B; Hart GW J. Biol. Chem 2015, 290, 29141–29153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Wang Z; Hart GW Clin. Proteomics 2008, 4, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Zachara NE; Vosseller K; Hart GW Curr. Protoc Protein Sci. 2011, 12.8.1–12.8.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Ma J; Hart GW Clin. Proteomics 2014, 11, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Wells L; Vosseller K; Cole RN; Cronshaw JM; Matunis MJ; Hart GW Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2002, 1, 791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Vosseller K; Hansen KC; Chalkley RJ; Trinidad JC; Wells L; Hart GW; Burlingame AL Proteomics 2005, 5, 388–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Overath T; Kuckelkorn U; Henklein P; Strehl B; Bonar D; Kloss A; Siele D; Kloetzel PM; Janek K Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2012, 11, 467–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Ma J; Banerjee P; Whelan SA; Liu T; Wei AC; Ramirez-Correa G; McComb ME; Costello CE; O’Rourke B; Murphy A; Hart GW J. Proteome Res. 2016, 15, 2254–2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Syka JE; Coon JJ; Schroeder MJ; Shabanowitz J; Hunt DF Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2004, 101, 9528–9533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Haynes PA; Aebersold R Anal. Chem 2000, 72, 5402–5410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Chalkley RJ; Thalhammer A; Schoepfer R; Burlingame AL Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2009, 106, 8894–8899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Trinidad JC; Barkan DT; Gulledge BF; Thalhammer A; Sali A; Schoepfer R; Burlingame AL Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2012, 11, 215–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Nagel AK; Schilling M; Comte-Walters S; Berkaw MN; Ball LE Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2013, 12, 945–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Nagel AK; Ball LE Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2014, 13, 3381–3395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Wang Z; Pandey A; Hart GW Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2007, 6, 1365–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Zachara NE; Molina H; Wong KY; Pandey A; Hart GW Amino Acids 2011, 40, 793–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Lee A; Miller D; Henry R; Paruchuri VD; O’Meally RN; Boronina T; Cole RN; Zachara NE J. Proteome Res. 2016, 15, 4318–4336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Teo CF; Ingale S; Wolfert M; Elsayed GA; Nöt LG; Chatham JC; Wells L; Boons GJ Nat. Chem. Biol 2010, 6, 338–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Zhao P; Viner R; Teo CF; Boons GJ; Horn D; Wells LJ Proteome Res. 2011, 10, 4088–4104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Khidekel N; Ficarro SB; Clark PM; Bryan MC; Swaney DL; Rexach JE; Sun YE; Coon JJ; Peters EC; Hsieh–Wilson LC Nat. Chem. Biol 2007, 3, 339–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Wang Z; Udeshi ND; O’Malley M; Shabanowitz J; Hunt DF; Hart GW Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2010, 9, 153–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Wang Z; Udeshi ND; Slawson C; Compton PD; Sakabe K; Cheung WD; Shabanowitz J; Hunt DF; Hart GW Sci. Signaling 2010, 3, ra2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Alfaro JF; Gong CX; Monroe ME; Aldrich JT; Clauss TR; Purvine SO; Wang Z; Camp DG 2nd; Shabanowitz J; Stanley P; Hart GW; Hunt DF; Yang F; Smith RD Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2012, 109, 7280–7285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Vocadlo DJ; Hang HC; Kim EJ; Hanover JA; Bertozzi CR Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2003, 100, 9116–9121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Boyce M; Carrico IS; Ganguli AS; Yu S–H; Hangauer MJ; Hubbard SC; Kohler JJ; Bertozzi CR Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2011, 108, 3141–3146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Woo CM; Iavarone AT; Spiciarich DR; Palaniappan KK; Bertozzi CR Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 561–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Qin K; Zhu Y; Qin W; Gao J; Shao X; Wang YL; Zhou W; Wang C; Chen X ACS Chem. Biol 2018, 13, 1983–1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Shevchenko A; Tomas H; Havli J; Olsen JV; Mann M Nature Protoc. 2007, 1, 2856–2860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Ramirez–Correa GA; Ma J; Slawson C; Zeidan Q; Lugo–Fagundo NS; Xu M; Shen X; Gao WD; Caceres V; Chakir K; DeVine L; Cole RN; Marchionni L; Paolocci N; Hart GW; Murphy AM Diabetes 2015, 64, 3573–3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Vasicek L; Brodbelt JS Anal. Chem 2009, 81, 7876–7884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Udeshi ND; Compton PD; Shabanowitz J; Hunt DF; Rose KL Nat. Protoc 2008, 3, 1709–1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Earley L; Anderson LC; Bai DL; Mullen C; Syka JE; English AM; Dunyach JJ; Stafford GC Jr.; Shabanowitz J; Hunt DF; Compton PD Anal. Chem 2013, 85 (17), 8385–8390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Jewett JC; Sletten EM; Bertozzi CR J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 3688–3690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Debets MF; van Berkel SS; Dommerholt J; Dirks AT; Rutjes FP; van Delft FL Acc. Chem. Res 2011, 44, 805–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Kim EJ; Kang DW; Leucke HF; Bond MR; Ghosh S; Love DC; Ahn JS; Kang DO; Hanover JA Carbohydr. Res 2013, 377, 18–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Teo CF; Wells L Anal. Biochem 2014, 464, 70–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Roquemore EP; Dell A; Morris HR; Panico M; Reason AJ; Savoy LA; Wistow GJ; Zigler JS; Earles BJ; Hart GW J. Biol. Chem 1992, 267, 555–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Takaesu G; Kishida S; Hiyama A; Yamaguchi K; Shibuya H; Irie K; Ninomiya–Tsuji J; Matsumoto K Mol. Cell 2000, 5, 649–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Sakurai H Trends Pharmacol. Sci 2012, 33, 522–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Liu Q; Busby JC; Molkentin JD Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 11, 154–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Parker BL; Gupta P; Cordwell SJ; Larsen MR; Palmisano GJ Proteome Res. 2011, 10, 1449–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.