Abstract

Background & Aims:

Inflammation, injury, and infection upregulate expression of the tryptophan metabolizing enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) in the intestinal epithelium. We studied the effects of cell-specific IDO1 expression in the epithelium at baseline and during intestinal inflammation in mice.

Methods:

We generated transgenic mice that overexpress fluorescence-tagged IDO1 in the intestinal epithelium under control of the villin promoter (IDO1-TG). We generated intestinal epithelial spheroids from mice with full-length Ido1 (controls), disruption of Ido1 (KO mice), and IDO1-TG and analyzed them for stem cell and differentiation markers by real-time PCR, immunoblotting, and immunofluorescence. Some mice were gavaged with enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (E2348/69) to induce infectious ileitis, and ileum contents were quantified by PCR. Separate sets of mice were given dextran sodium sulfate or 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid to induce colitis; intestinal tissues were analyzed by histology. We utilized published datasets GSE75214 and GDS2642 of RNA expression data from ilea of healthy individuals undergoing screening colonoscopies (controls) and patients with Crohn’s disease.

Results:

Histologic analysis of small intestine tissues from IDO1-TG mice revealed increases in secretory cells. Enteroids derived from IDO1-TG intestine had increased markers of stem, goblet, Paneth, enteroendocrine, and tuft cells, compared with control enteroids, with a concomitant decrease in markers of absorptive cells. IDO1 interacted non-enzymatically with the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) to inhibit activation of Notch1. Intestinal mucus layers from IDO1-TG mice were 2-fold thicker than mucus layers from control mice, with increased proportions of Akkermansia muciniphila and Mucispirillum schaedleri. Compared to controls, IDO1-TG mice demonstrated an 85% reduction in ileal bacteria (P=0.03) when challenged with enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, and were protected from immune infiltration, crypt drop-out, and ulcers following administration of dextran sodium sulfate or 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid. In ilea of Crohn’s disease patients, increased expression of IDO1 correlated with increased levels of MUC2, LYZ1 and AHR but reduced levels of SLC2A5.

Conclusions:

In mice, expression of IDO1 in the intestinal epithelial promotes secretory cell differentiation and mucus production; levels of IDO1 are positively correlated with secretory cell markers in ilea of healthy individuals and Crohn’s disease patients. We propose that IDO1 contributes to intestinal homeostasis.

Keywords: kynurenine, metabolism, organoids, microbiome, ulcerative colitis

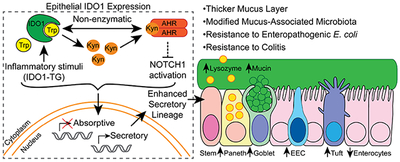

Graphical Abstract

Lay Summary:

The intestinal protein IDO1 mediates a response that protects against inflammation.

INTRODUCTION

The intestinal epithelium provides a critical physical and immunological barrier between the host and its external environment (i.e., luminal contents) to maintain homeostasis.1 Barrier disruption and alterations of the intestinal microbial composition characterize inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) Crohn’s Disease and ulcerative colitis.1, 2 Resolution of barrier disruptions and microbial dysbiosis is required to restore tissue homeostasis and resolve inflammation related symptoms. Defining the mechanisms that restore epithelial homeostasis is necessary to understanding inflammatory disease pathophysiology and may provide avenues for new IBD therapies.

Secretory epithelial cells, including goblet, Paneth and enteroendocrine cells, have important roles in maintaining mucosal homeostasis. Most notably, these cells contribute to epithelial barrier integrity by producing and secreting mucus and antimicrobial peptides.3–5 Additionally, Paneth cells maintain the stem cell niche by providing Wnt ligands and other growth factors.6 Goblet cells loss is observed in IBD, which may perpetuate ongoing barrier disruption and contribute to disease chronicity.7 Therefore, a better understanding of mechanisms that promote epithelial restitution and healing in response to inflammatory stimuli is needed.

Host and microbial tryptophan (Trp) metabolism is emerging as a critical regulator of mucosal homeostasis.8, 9 Gut microbes metabolize Trp to a variety of indole compounds that promote intestinal homeostasis by activating the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR).9 The host enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1), which is the first enzyme in Trp metabolism on the kynurenine (Kyn) pathway, is perhaps most relevant in the context of homeostasis. Inflammatory cytokines and TLR ligands upregulate IDO1, and IDO1 overexpression occurs in multiple pathologies including human and animal models of IBD, infection and diverticulosis.8, 10–12 In many contexts, IDO1 correlates with reduced disease severity, while genetic ablation or pharmacologic inhibition of IDO1 increases disease severity.8, 11, 13

Several cell types and mechanisms reduce disease severity via IDO1. IDO1 expression in antigen presenting cells induces regulatory T cells and limits T effector cell responses.14–16 Even though the functional role of IDO1 expression in intestinal epithelial cells in human IBD and animal models of colitis remains poorly elucidated,10,11,13 we have demonstrated that intact IDO1 activity is associated with enhanced proliferation in crypts adjacent to dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced ulcerations and correlated with reduced ulcer severity and recovery time.11, 17 These data lead us to hypothesize that epithelial IDO1 interacts directly or indirectly with signaling pathways that promote mucosal healing. In the current study, we developed a mouse with transgenic overexpression of IDO1 in the intestinal epithelial cells and employed in vitro and in vivo modeling as well as human specimens to define the functional impact of IDO1 activity on the intestinal epithelium.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

All procedures were approved by the Washington University animal studies committee and adhere to the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines. Wildtype (WT) and Ido1 knockout (KO) mice were originally purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and maintained in-house. Mouse line pVil-EGFP/IDO1 was generated by the Washington University Mouse Genetics Core facility. Animals are age- and sex-matched for each experiment, using co-housed littermates as WT controls.

Cell Culture and Reagents.

Primary mouse intestinal stem cell lines were generated as previously described using 1–2cm of tissue from terminal ileum and mid colon of each genotype.18 Briefly, tissue was minced and digested with type I collagenase, filtered, embedded in Matrigel and maintained in 50% L-WRN conditioned medium with 10μM Y-27632 and 10μM SB 431542 (50% CM) supplemented with 350μM Trp at 37°C, 5% CO218. Experimental details can be found in Supplemental Methods.

RNA and Protein Quantification.

RNA was extracted from whole tissue or spheroid culture and quantified by real-time PCR using methods and primers described in supplementary methods. Protein was extracted from enteroids liberated from Matrigel with Corning Cell Recovery Solution, then lysed with 1x cell lysis solution supplemented with Halt protease/phosphatase inhibitors and homogenized with Takara BioMasher tubes. Lysates were sonicated and quantified by BCA assay. Proteins were resolved on a 4-12% gradient gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane via an iBlot 2 apparatus. Active lysozyme was detected in stool with EnzChek Lysozyme Assay Kit as per manufacturer’s instructions.19

Histology and Immunofluorescence.

Animals were injected with 120 mg/kg 5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine (BrdU) before sacrifice. Ileum and colon sections were fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin or embedded unfixed in Tissue-Tek® O.C.T. Compound and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Enteroids were removed from Matrigel and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by embedding in Tissue-Tek® O.C.T. Compound and frozen in liquid nitrogen. For mucus layer quantification tissues were immersed in methacarn fixative (60% methanol, 30% acetic acid, 10% chloroform) and fixed for 24h at 4C, followed by 3 washes with 100% ethanol before processing for histology as outlined above. Primary and secondary antibody treatments were performed as outlined for enteroids. Additional details are in Supplemental Methods.

Microbial Analysis.

Mucus-associated microbiota (PBS washes) or luminal contents were collected and stored at −80C. Microbial gDNA was isolated using QIAamp® Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit as per manufacturer’s protocol. Microbial populations were characterized using qRT-PCR with primers specific for muciniphilic bacteria as previously described.20–23 Further experimental details are in Supplemental Methods.

Enterocolitis Models.

Eight to 12-week-old animals were subjected to one of three enterocolitis models based on previous literature: gavage of ~2 × 108-9 cfu Escherichia coli E2348/69 and harvest after 3 days24; 3-4% DSS in drinking water for 4–5 followed by drinking water for 3-6 days before harvest as described in figure legends11; or an enema containing 2.5% 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS) in 50% ethanol and harvest after 3 days.11, 25 Further experimental details are in Supplemental Methods.

Human Microarray Data.

Datasets GSE7521412 and GDS264226 were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus website. Log2 expression data from ileum biopsy samples were sorted by health status (Control or CD) and disease status (control, active, and inactive). Three outliers were removed from all analyses based on low levels of the epithelial marker villin. Comparisons of mean gene expression between groups and correlation statistics were performed using Graphpad Prism 5.

Statistics.

All in vitro experiments were performed at least in triplicate and data presented represents mean ± standard deviation. Histology data from genotypes were combined and data presented represents mean ± standard deviation. Chi-square goodness-of-fit test was used to test for normal distribution, then replicate data were subjected to appropriate statistic tests (Student’s t test with Welch’s correction when indicated, Mann-Whitney, one- or two-way analysis of variance, Fisher’s exact) using Graphpad Prism 5. All authors had access to the study data, and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

RESULTS

Generation and Validation of a Transgenic Mouse with Overexpression of IDO1 in the Intestinal Epithelium.

The coding sequence of IDO1 was cloned in-frame with enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) in an expression vector under the control of the villin promoter, thereby directing its expression to the intestinal epithelium (Fig. 1A).27 Human and mouse IDO1 are structurally and functionally similar.28 Use of human IDO1 facilitated distinction between endogenous (murine) and transgenic (human) IDO1 expression. Pairing IDO1 to the villin promoter enables assessment of the sufficiency of epithelial IDO1 expression as a mechanism affecting mucosal healing.

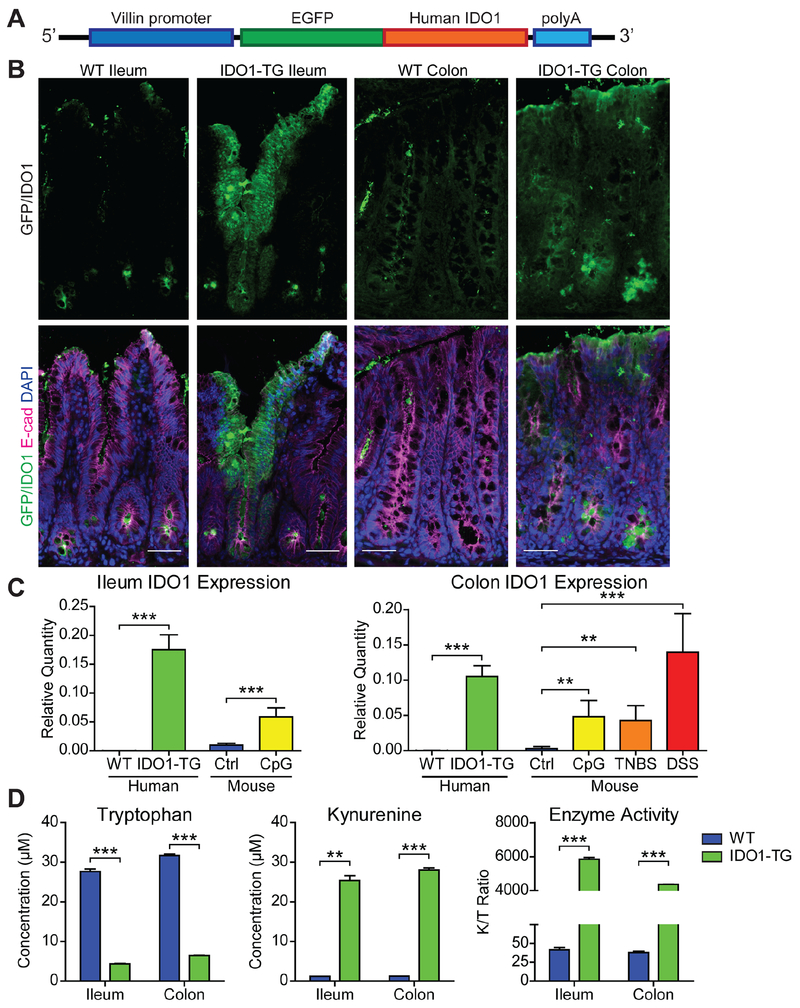

Figure 1: IDO1-TG mice overexpress functional IDO1 in the intestinal epithelium.

A) Transgenic mouse line pVil-EGFP/hIDO1 (IDO1-TG) schematic. B) Representative indirect immunofluorescence images showing the EGFP fluorescence as a surrogate marker for IDO1 expression (Top) and with epithelial cells marker E-cadherin (E-cad) staining (Bottom). Bar = 50μm. C) HuIDO1 RNA is detectable in whole tissue from transgenic mouse ileum and colon, and is comparable to endogenous IDO1 expression levels produced in response to models of inflammation: immunostimulatory DNA (CpG), TNBS, and DSS. RNA relative abundances were calculated relative to Gapdh levels from N=3-5 mice. D) Enzymatic activity of IDO1-TG was confirmed by measuring the Tryptophan and Kynurenine in spheroid culture medium. Representative data from two independent experiments. **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001 by Student’s t-test.

We generated transgenic mice (termed IDO1-TG) by pronuclear injection of this construct, and putative founders were mated to WT animals. This new mouse model was validated in several ways. Immunofluorescence imaging for EGFP and E-cadherin confirmed epithelial expression of the IDO1 construct in intestine and colon (Fig. 1B), and bulk intestinal RNA subjected to quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) using specific primers confirmed human IDO1 RNA expression (Fig. 1C). RNA expression levels were comparable to those seen in response to inflammatory stimuli (unmethylated CpG DNA) as well as colitis models (TNBS and DSS).11, 17 IDO1 protein was detectable by immunoblot in both the ileum and colon to comparable extents (relative to β-actin; Fig. S1B). To validate transgene activity, we generated enteroid and colonoid cell lines from WT and IDO1-TG mice as previously described.18, 29 Human IDO1 RNA was only detectable in IDO1-TG spheroids (Fig. S1A). We then tested the culture media supernatants (48 hrs) by HPLC to detect Kyn pathway metabolites.30 The ratio of concentration of Kyn to Trp was significantly greater for IDO1-TG enteroids than for WT (Fig. 1D). Supernatant concentrations of 3-hydroxykynurenine, arachidonic acid, picolinic acid, and quinolinic acid were comparable in IDO1-TG and WT enteroids (Fig. S1C–F). Taken together, these data demonstrate that transgenic IDO1 is expressed and enzymatically active in the intestinal epithelium of IDO1-TG mice.

IDO1 Enhances Secretory Cell Lineage Differentiation in the Intestinal Epithelium in vivo.

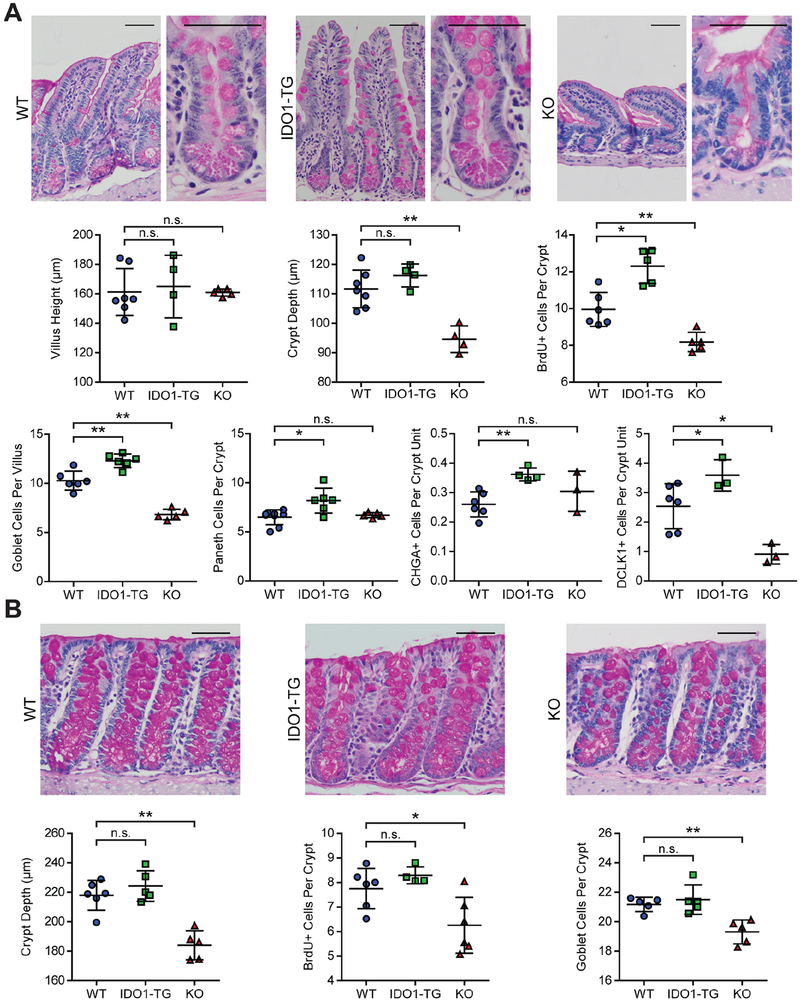

We next sought to characterize the impact of high IDO1 expression on intestinal morphology and epithelial cell composition using IDO1-TG, previously generated KO31 and WT littermate controls. We stained histological tissue sections from small intestine and colon with hematoxylin and eosin or periodic acid-Schiff stain (PAS) to examine tissue morphology and polysaccharide-rich cells, respectively. IDO1 overexpression did not alter the villus height or crypt depth in the terminal ileum, but crypt depth was reduced in KO mice (Fig. 2A and Fig. S2A). BrdU incorporation was 30% greater in the ileal crypts of IDO1-TG mice and 15% lower in KO mice, indicating IDO1 activity enhances epithelial proliferation. The densities of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) positive cells, which indicate apoptosis, were negligible for both WT and IDO1-TG (data not shown). PAS-positive goblet and Paneth cells were proportionally increased in IDO1-TG relative to WT. Chromogranin A (CHGA)-expressing enteroendocrine cells were increased to a similar extent (46.4%) in IDO1-TG mice compared to WT mice, as were Doublecortin like kinase 1 (DCLK1)-positive tuft cells (41.4% increase). While goblet and tuft cells were significantly reduced (33.6% and 64.1% respectively) in KO mice, there was no change in Paneth or enteroendocrine cells. Crypt depth, goblet cell number, and proliferation were not increased in the colon of IDO1-TG, but were reduced KO mouse colons (Fig. 2B and Fig. S2B).

Figure 2: IDO1 expression promotes intestinal secretory cell differentiation in vivo.

Representative images of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections stained with PAS stain identifying secretory cells of the ileum (A) and colon (B) of WT, IDO1-TG, and KO mice. H&E or PAS stained sections were used to quantify crypt metrics, goblet and Paneth cells. CHGA and DCLK1 immunohistochemistry was used to quantify enteroendocrine and tuft cells respectively. Data is presented as mean ± standard deviation from N=3–6 mice/genotype from at least two experimental replicates. Bars in micrographs = 50μm. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01 by Mann-Whitney test. n.s., not significant.

IDO1 Enhances Differentiation of Secretory Lineages in Enteroid Cultures.

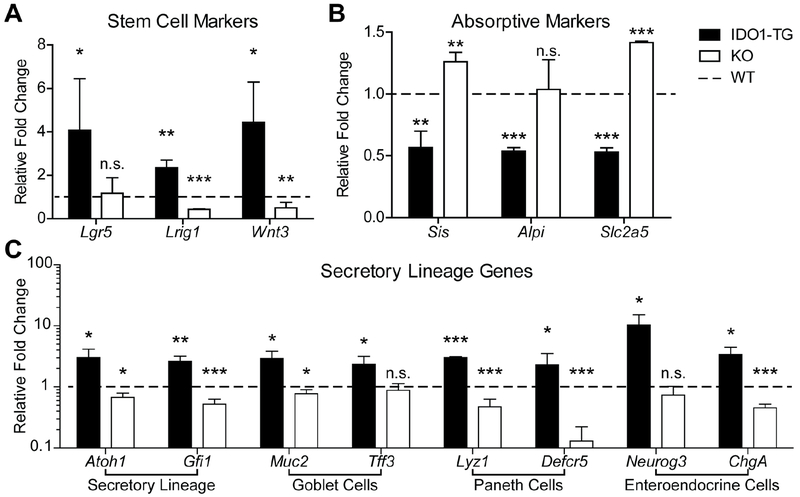

Next, we assessed expression of genes associated with stemness and differentiation in WT, IDO1-TG, and KO enteroids.18, 29 Upon differentiation, bulk enteroids from IDO1-TG mice maintained higher mRNA expression levels of the stem cell markers Lgr5 and Lrig1, as well as the Wnt pathway ligand Wnt3 (Fig. 3A). Differentiated IDO1-TG enteroids also exhibited reduced expression of the absorptive enterocyte markers Sis, Alpi, and Slc2a5 (Fig. 3B). Consistent with observations from histology tissues, IDO1-TG enteroids expressed significantly more goblet cell-associated genes Muc2 and Tff3, Paneth cell-associated genes Lyz1 and Defcr5, and enteroendocrine cell-associated genes Neurog3 and ChgA (Fig. 3C).3–5 Atonal homologue 1 (Atoh1, also known as Math1), the transcription factor required for commitment to the secretory cell lineage, was also upregulated, as was its downstream effector Gfi1 (Fig. 3C).32 On the contrary, stem cell and secretory cell gene expression was similar between WT and IDO1-TG colonoids (Fig. S3). Thus, the in vitro data are consistent with the in vivo observations (Fig. 2). Taken together, these data indicate IDO1 acts specifically in the epithelium to promote the formation of secretory cells in the small intestine at the most proximal steps in cell fate commitment.

Figure 3: IDO1 expression promotes secretory lineage differentiation in vitro.

Enteroids were derived from the ileum of WT, IDO1-TG and KO mice and examined for expression of (A) stem cell, (B) enterocyte, and (C) secretory lineage markers. qRT-PCR data presented as fold change relative to WT differentiated state. Data represents mean ± standard deviation from at least three independent experiments. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001 by Student’s t-test. n.s., not significant.

To confirm the role of IDO1 in epithelial cell differentiation, KO enteroids were also assessed for stem, absorptive, and secretory cell markers after differentiation. Enteroids that lack IDO1 expression exhibited reduced relative abundance of Lrig1 and enhanced relative abundances of Sis and Slc2a5 (Fig. 3A,B, white bars). KO enteroids also exhibited reduced relative abundances of Atoh1 and Gfi1, which was reflected by a reduction in the majority of secretory cell markers (Fig. 3C, white bars). Taken together, these data indicate IDO1 expression decides epithelial cell fate at the onset of intestinal epithelial cell differentiation.

One role of small intestinal Paneth cells is to maintain the stem cell niche via secretion of Wnt ligands.6 To test whether the increase in stem cell markers in IDO1-TG is related to the enhanced Wnt ligands, WT and IDO1-TG enteroids were differentiated in the presence of porcupine inhibitor, which blocks the processing and secretion of Wnt ligands.33 Inhibition of Wnt ligand secretion reduced Lgr5 expression levels in both WT and IDO1-TG enteroids, but did not alter expression of Lrig1 (Fig. S4). This suggests that the presence of enhanced Wnt signaling in IDO1-TG works in concert with other active signaling pathways to produce the observed phenotype.

IDO1 Enhances Secretory Cell Type and Activity in vitro.

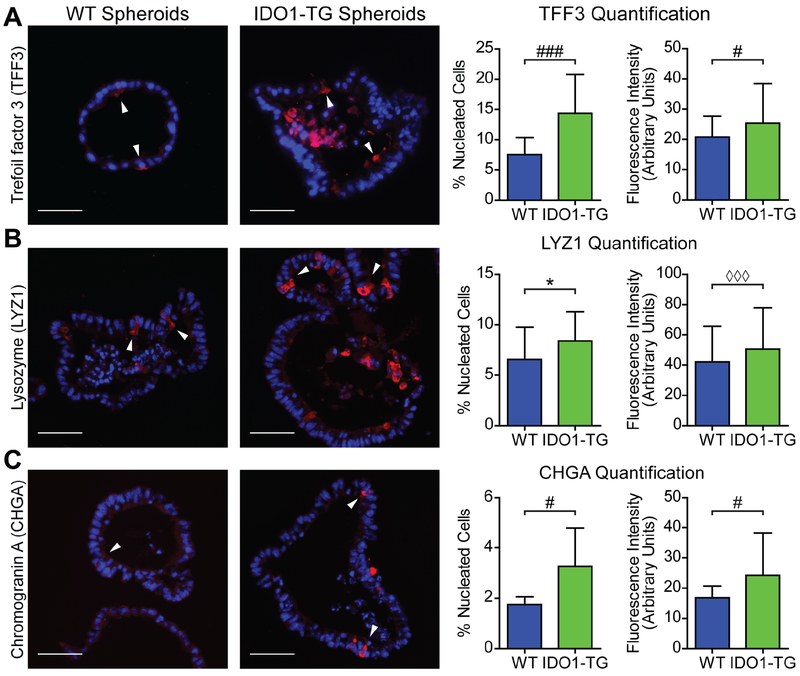

The expression of specific secretory cell markers was confirmed in WT and IDO1-TG enteroids by immunofluorescence. Both WT and IDO1-TG enteroids contained cells that stained positive for TFF3, LYZ1, and CHGA, which are markers for goblet, Paneth, and enteroendocrine cells, respectively (Fig. 4A–C). When these cells were quantified, differentiated enteroids from IDO1-TG demonstrated significantly greater numbers of goblet, Paneth, and enteroendocrine cells compared to WT. In addition to a greater number of secretory cells, the mean fluorescence of positive cells was more intense in IDO1-TG enteroids. Together, these data confirm IDO1 expression enhances differentiation along the secretory lineage in an epithelial cell-autonomous fashion in vitro, and demonstrates IDO1 expression increases production of secretory products by these cells.

Figure 4: IDO1-TG spheroids exhibit increased secretory cells in number and fluorescence intensity.

Enteroids from WT and IDO1-TG mice were analyzed by immunofluorescence after 48h in differentiation medium. Representative immunofluorescence images, quantification of positive cells (number of positive cells per total nucleated cells) and fluorescence intensity using markers of (A) goblet cells (TFF3), (B) Paneth cells (LYZ1), and (C) enteroendocrine cells (CHGA). Data represents mean ± standard deviation from two independent experiments. Bars in micrographs = 50μm.*, P<0.05 by Student’s t-test; #, P<0.05; ###, P<0.001 by Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction; ◊◊◊, P<0.001 by Mann-Whitney test.

Epithelial IDO1 Enhances Secretory Lineage via Interaction with the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor.

We next explored the molecular mechanism by which IDO1 enhances secretory cell function. To examine the role of Trp metabolism in this phenotype, we inhibited IDO1 enzymatic function with 1-methyl-L-tryptophan or Epacadostat.34 While Muc2 expression was again greater in IDO1-TG enteroids, neither inhibitor reduced the expression of Muc2 (Fig. 5A). Paradoxically, exogenous Kyn decreased Muc2 expression in WT enteroids, while increasing its expression in KO enteroids (Fig. 5B). These data indicate IDO1 enzymatic activity and kynurenine contribute to secretory lineage differentiation at baseline. However, non-enzymatic IDO1 functions may be the principal drivers of this phenotype in states of high epithelial IDO1 expression, such as inflammation and in the IDO1-TG model.

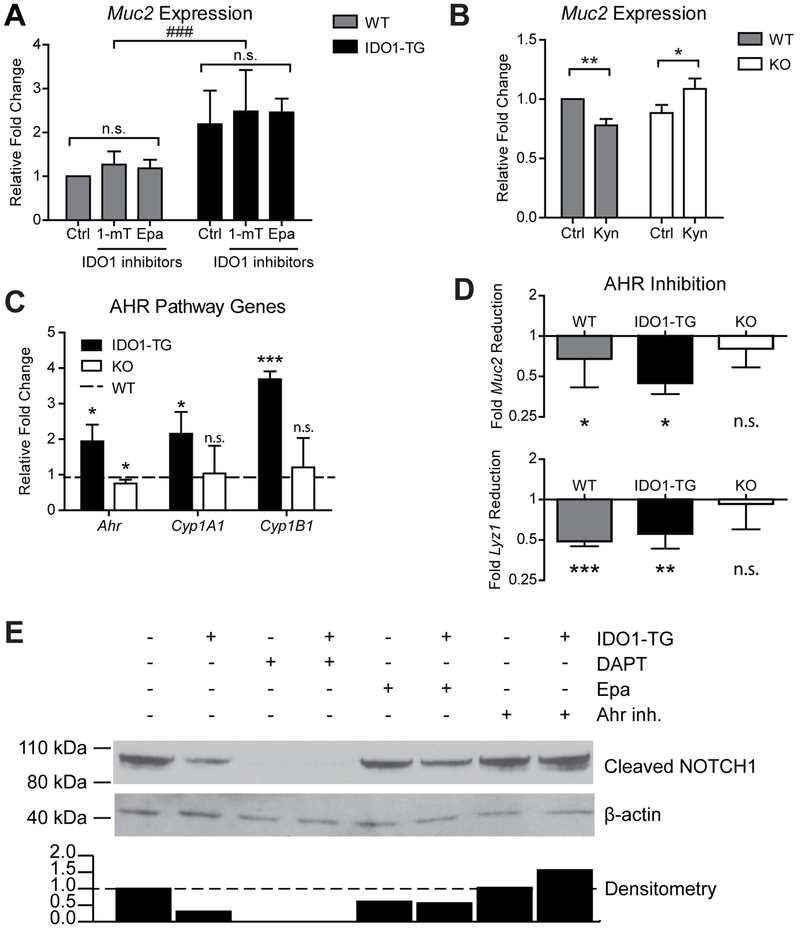

Figure 5: IDO1 interacts with AHR to enhance secretory lineage differentiation by inhibiting Notch signaling.

A) Muc2 expression in enteroids differentiated in the presence of two metabolic inhibitors of IDO1, 1-methyl-L-tryptophan (1-mT, 500μM) and Epacadostat (Epa, 5μM). B) Muc2 expression in enteroids differentiated in the presence of IDO1 metabolite-L-Kynurenine (Kyn, 100μM). C) Expression of Ahr and two transcriptional targets, Cyp1a1 and Cyp1b1. Data presented as fold change relative to WT. D) Reduction in Muc2 and Lyz1 expression in enteroids differentiated in the presence of CH-223191, a specific inhibitor of AHR (20μM), relative to untreated enteroids. qPCR data represents mean ± standard deviation from at least 3 independent experiments. E) Immunoblot of protein from undifferentiated WT (−) and IDO1-TG (+) spheroids cultured in the presence of DAPT (10uM), Epa (5μM), or CH-223191 (20μM). Densitometry of immunoblot is displayed below. Data is representative of 3 independent experiments. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001 by Student’s t-test; ###, P<0.001 by one-way ANOVA.

We next asked if non-enzymatic IDO1 functions contribute to the observed phenotype. IDO1 has a non-enzymatic signaling interaction with AHR16, 35, and we found that expression of AHR and two of its downstream transcriptional targets Cyplal and Cyplb1 were increased in IDO1-TG enteroids while remaining unchanged or modestly reduced in KO enteroids (Fig. 5C).35, 36 We further examined the impact of AHR activity using the AHR antagonist CH-22319135 which reduced IDO1-mediated Muc2 expression (Fig. 5D). These data show IDO1 enhances secretory cell lineage differentiation at least in part through direct signaling interaction with AHR.

Epithelial IDO1 Modulates Notch Signaling via AHR.

Notch signaling is involved in maintaining stem cells and promotes differentiation towards absorptive over secretory lineage.37 Therefore, we interrogated this pathway as a potential molecular target of IDO1-mediated AHR signaling. We found relative abundances of transcripts encoding the Notch receptors, ligands and target genes were variably altered in IDO1-TG enteroids (Fig. S4B,C). Expression of the Notch effector Hes1 remained unchanged while the Paneth cell-specific effector Hes538 was upregulated. These data illustrate that IDO1-mediated modulation of Notch signaling favors maintenance of Paneth cells, an important component of the stem cell niche.

IDO1-TG enteroids exhibited a reduction in the activated form of NOTCH1 (Fig. 5E). NOTCH1 activation was completely eliminated in WT and IDO1-TG enteroids by adding a γ-secretase inhibitor N-[N-(3,5-Difluorophenacetyl)-L-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester (DAPT).18 The observed difference in NOTCH1 activation between WT and IDO1-TG was maintained during IDO1 inhibition, but was normalized in the presence of AHR antagonism. Taken together, these data demonstrate that IDO1 inhibits NOTCH1 signaling in an AHR-dependent, non-enzymatic manner. As inhibition of Notch signaling skews differentiation towards secretory cell lineages,18, 29 this is a possible mechanism of enhanced secretory cells in IDO1-TG.

IDO1 Increases Secretory Cell Function in vivo.

We then sought to identify functional differences in epithelial physiology related to IDO1. Ileal tissue from WT and IDO1-TG animals was fixed with methacarn to preserve mucus layer integrity and processed for MUC2 immunofluorescence. Using this method, the mucus appeared as a region of MUC2-positivity apical to the villi, and exhibited regions of continuity across several villi (Fig. 6A). Quantitatively, IDO1-TG mice exhibited a 2.0-fold thicker mucus layer than WT mice (Fig 6B). To assess the function of Paneth cells in vivo, we measured lysozyme activity in WT and IDO1-TG stool extracts.19 Stool extracts from IDO1-TG mice had slightly increased lysozyme activity (Fig. 6C). These data indicate the enhanced secretory cell differentiation has physiological effects in IDO1-TG mice.

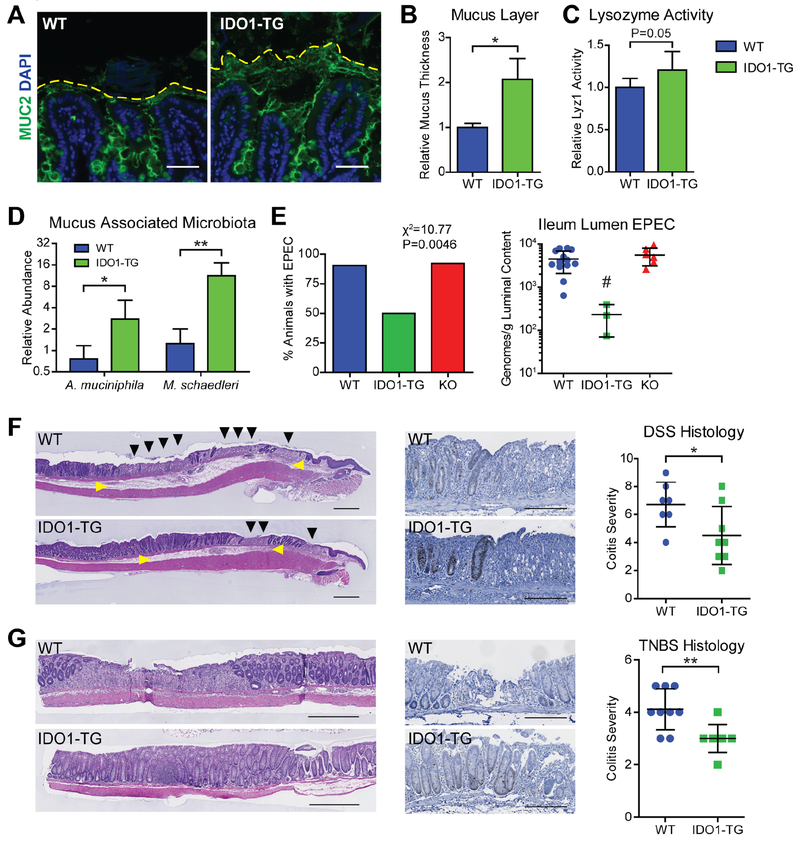

Figure 6: IDO1 expression enhances mucus barrier and modulates microbiota.

A) Representative immunofluorescence micrographs of methacarn-fixed WT and IDO1-TG ileum tissue depicting the preserved mucus layers. Bar=50μm. B) Quantification of the mucus layers measured from the top of the villi to the periphery of the MUC2-positive region. C) Lysozyme activity was measured from stool extracts from WT and IDO1-TG mice. D) qPCR using species-specific primers was used to quantify muciniphilic bacteria in the ileum mucus-associated microbiota from WT and IDO1-TG mice. Abundance was calculated relative to bacterial gene rpolB. E) Presence (left) and quantification (right) of enteropathogenic E. coli E2348/69 (EPEC) in the ileum of WT, IDO1-TG, and KO mice on day 3 normalized to luminal content and inoculation quantity. F,G) Representative micrographs of colon tissue from WT and IDO1-TG mice treated with 3% DSS in drinking water for 5 days followed by 3 days of water (F) or 2.5% TNBS in 50% ethanol and harvested after 3 days (G) stained with H&E. Representative micrograph of Ki67-positive cells in the peri-ulcer region of WT and IDO1-TG mice (center); Colitis severity as scored from histological sections. N=3-10 mice per genotype in at least two independent experiments. Bar = 500μm (G, left) or 200μm. Black triangle: epithelial ulceration; yellow triangle: edema. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01 by Student’s t test; #, P<0.05 by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test.

IDO1 Augments Mucus Layer and Modulates Mucus Associated Microbiota.

The effect of an enhanced mucus layer on the resident ileum microbiota was assessed by species-specific qPCR directed towards select mucophilic bacterial species.20–23 IDO1-TG mice maintained 3.0-fold greater quantities of Akkermansia muciniphila and 11.3-fold greater quantities of Mucispirillum schaedleri compared to WT mice (Fig. 6D).21

There are few animal models of ileal Crohn’s Disease, with most relying on genetic aberration to elicit pathology. Thus, we employed enteropathogenic E. coli to model infectious ileitis. WT, IDO1-TG, and KO mice were challenged with ~2.0×108-9 colony forming units (cfu) of E. coli E2348/69 by gavage, and after 3 days the bacterial burden in ileum contents was quantified by qPCR.24 The majority of WT and KO mice had E2348/69 detectable in the ileum, compared to only 50% of IDO1-TG mice (Fig. 6E, left). WT animals also demonstrated greater density of E2348/69 in the luminal contents of the ileum than IDO1-TG animals, while KO mice had comparable densities (Fig. 6E, right). Together, these data demonstrate that IDO1-mediated enhancement of the secretory lineage augments the mucus layer and modulates commensal and pathogenic bacterial microbiota.

Epithelial IDO1 is Protective in Colitis Models.

We further evaluated the physiologic significance of epithelial IDO1 in two mouse models of IBD. In the DSS colitis model of epithelial damage, IDO1-TG mice exhibited less extensive mucosal ulcerations and mucosal edema with highly proliferative crypts at the ulcer margin and reduced histologic disease severity (Fig. 6F). Similarly, disease severity (ulcers, lamina propria immune cell infiltration and crypt loss) in the immune mediated TNBS model of colitis was reduced in IDO1-TG mice (Fig. 6G). These data indicate that epithelial IDO1 expression is sufficient to reduce colitis severity in these animal models of human IBD.

Secretory Cell Markers Correlate with IDO1 Expression in Human Biopsies from Healthy and Crohn’s Disease Patients.

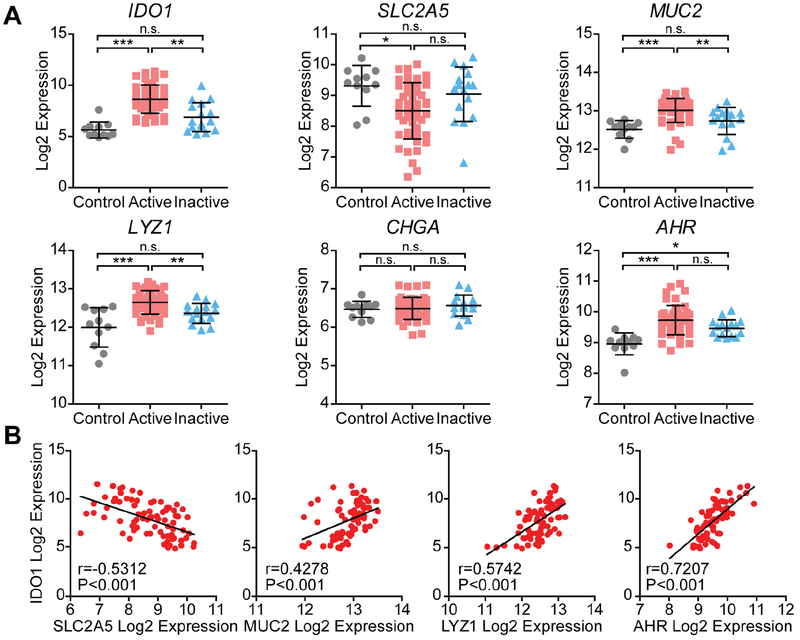

IDO1 is one of the most upregulated genes in human IBD,8, 10–12 so we next studied its role in human tissues. We compared gene expression profiles from the ilea of healthy individuals undergoing screening colonoscopies (control), patients with active Crohn’s Disease (active), and patients with Crohn’s Disease in remission (inactive).12 In this context, expression of IDO1 was significantly upregulated in the active samples compared to control and inactive samples (Fig. 7A). Concurrently, the absorptive cell marker SLC2A5 was reduced in the active samples. In contrast, goblet and Paneth cell markers MUC2 and LYZ1, respectively, were in greatest relative abundance in the active samples, with the latter also upregulated in the tissue from patients with inactive disease. No difference was observed in enteroendocrine marker CHGA.

Figure 7: IDO1 expression correlates with reduced absorptive and enhanced secretory cell markers in human ileum from control and Crohn’s disease.

A) Ileal RNA expression data from healthy control patients (Control), Crohn’s disease patients with active inflammation (Active), and Crohn’s disease patients without active inflammation (inactive). Log2 expression values for each gene were grouped according to disease state. Data represents mean ± standard deviation. B) Log2 expression values of select enterocyte (SLC2A5), goblet (MUC5B), and Paneth cell (LYZ1) markers, and AHR was assessed for correlation with IDO1 expression. n.s., not significant; *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001 by nonparametric one-way ANOVA with Dunn’s multiple comparison test.

Expression of AHR was greatest in the active state, and expression was significantly greater in both the active and inactive state than in the control state. The expression of these cell type markers was also tested for correlation with IDO1 expression within all samples (Fig. 7B). Expression of SLC2A5 was negatively correlated, while MUC2, LYZ1, and AHR were positively correlated with IDO1. These findings were confirmed in an additional published dataset (Fig. S5).26 These data reveal IDO1 expression is associated with reduced expression of absorptive cell markers, and is associated with at least a partial increase in secretory cell markers in the ilea of human patients.

DISCUSSION

The immune-metabolic enzyme IDO1 is highly upregulated in the gut epithelium during inflammation, injury, and infection.9, 12–14 In this study, we use in vitro and in vivo modeling to demonstrate that high epithelial IDO1 expression steers cellular differentiation towards secretory lineages, modulates mucin-associated microbiota, and reduces colitis severity. These findings increase our understanding of the pro-homeostasis functions for intestinal IDO1, which is already well recognized for the ability to shape adaptive mucosal immunity.11, 14 We also identify AHR as an effector of IDO1-mediated impact on epithelial differentiation, and provide evidence indicating that IDO1 and AHR interact through kynurenine-dependent and kynurenine-independent mechanisms. The findings identifying an IDO1-AHR signaling axis in the intestinal epithelium may have implications for therapies targeting infectious and inflammatory conditions.

Prior studies of IDO1 have examined its impact on disease models using a global genetic knockout mouse and/or inhibitors such as 1-methyl-DL-tryptophan, which has activities beyond IDO1 inhibition.39 Several of these reports indicate that IDO1 activity promotes intestinal homeostasis, controls infection, and reduces inflammatory disease severity.11, 14, 25, 40, 41 These and other studies also link IDO1 activity to IL-10 signaling (a pro-homeostatic cytokine) in the intestinal epithelium and mucosa.40–42 Other studies have shown that IDO1 knockout mice exhibit resistance to experimental colitis (Citrobacter rodentium and DSS) and implicate mechanisms of altered host-microbial signaling.43, 44 In contrast to the Shon et al study showing resistance to DSS colitis43, we found that germline KO mice exhibited greater colitis severity and delayed epithelial healing during the recovery phase of DSS (Figure S6). These data suggest the following about the cell specific roles of IDO1 in the intestine: at baseline, IDO1 expressing non-epithelial cells (CD103+ dendritic cells and macrophages) promote homeostasis through regulating adaptive immune cell responsiveness and potentially having paracrine effects on the epithelium through kynurenine production.14–16 In the setting of intestinal injury, inflammation, and in some infections, epithelial IDO1 is then highly upregulated. Upon overexpression, epithelial IDO1 works synergistically through enzymatic and non-enzymatic signaling to limit ongoing epithelial damage, promote epithelial regeneration, and shape microbial interactions and responsiveness.

IDO1-TG mice were protected from both ileal (EPEC) and colonic (colitis models) pathology. In the homeostatic state, proliferation and secretory cell differentiation was enhanced in the ileum of IDO1-TG mice and decreased in the colon and ileum of KO mice. Noting these differences, the role of IDO1 in the epithelium is likely context and tissue dependent as well as shaped signals occurring concurrent with inflammation and injury. In the small intestine, the enhanced stem cell markers in IDO1-TG may be explained by the presence of Paneth cells, a small intestine-specific secretory lineage known to support the stem cell niche.6 In support of this, blocking the secretion of Paneth cell-derived Wnt ligands reduced Lgr5 expression in vitro (Figure S4). Interestingly, crypt metrics were not different in IDO1-TG mice despite the observed increase in BrdU+ cells. This discrepancy is likely explained by enhanced cell turnover and extrusion.45 Differences in goblet cells may not be detected at baseline in the colon as this cell type is already highly represented in the colon versus the small intestine and further upregulation by IDO1 may not be possible. Finally, although we did not observe significant differences in mRNA or protein expression, villin promoter activity is known to be greater in the ileum than colon and may account for the pronounced phenotype in the ileum. Together, our data illustrate the importance of IDO1, not only as an upstream activator of AHR, but also as a regulator of the intestinal stem cell niche.

While previous work has focused on the role of AHR in primary immune cells, there is expanding evidence for a role in the epithelium.35, 41, 42 Our data provide evidence that IDO1 and AHR function via an epithelial cell-intrinsic mechanism to inhibit Notch signaling and direct secretory cell differentiation (Fig. 3–5). A similar association was recently suggested in a colon cancer cell line.46 IDO1 has been shown to interact with AHR through both a Kyn-dependent and Kyn-independent mechanism.14–16, 35 While the addition of Kyn to KO enteroids restored Muc2 expression to WT levels, neither WT nor KO enteroids achieved the enhanced Muc2 expression observed in IDO1-TG enteroids (Fig. 5B). Moreover, enzymatic inhibitors did not normalize Muc2 expression in IDO1-TG organoids. While it is possible enzymatic inhibition was incomplete, another potential explanation for this observation is direct signaling by the phosphorylated form of IDO1, a mechanism that has been reported in dendritic cells.35 Thus, while some minimal level of IDO1 enzymatic activity may support baseline secretory lineage differentiation, a non-enzymatic function of IDO1 may augment this phenotype in the setting of high epithelial IDO1 such as during inflammation. In summary, our findings uncover the capacity of IDO1 and AHR to interact and modulate differentiation of the normal intestinal epithelium.

Tryptophan metabolites play important roles in host-microbial crosstalk. Several recent studies demonstrate how indoles, derived from diet and microbial metabolism of tryptophan, shape host immune responses.9 Herein, we demonstrate IDO1 expression in the host epithelium modulates mucus-associated microbiota and augments resistance to pathogen adherence. To demonstrate this we modeled enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) infection, a pathogen that binds intestinal epithelial cells and is an important cause of infectious diarrhea,24 IDO1-TG mice demonstrated a reduced burden of EPEC, while KO mice did not differ from WT mice. This suggests that IDO1 expression may not be protective against infection at baseline, but is an inducible protective mechanism in the stimulated state. Further studies are needed to demonstrate the efficacy of this pathway in the context of other infectious disorders and chronic models of colitis.

Our data demonstrating enhanced A. muciniphila populations in the ileum of IDO1-TG mice is intriguing, as this organism has been suggested to enhance mucosal wound healing.21 These mucolytic bacteria are significantly reduced in histologically normal intestine of IBD patients compared to healthy controls.22 A. muciniphila also reduces disease activity in mouse models of epithelial damage.47 However, the role of mucus consuming microbiota in human IBD needs further elucidation. For example, one recent study demonstrated that limiting colonization of A. muciniphila protected against IL10−/− colitis48 while another identified Mucispirillum schaedleri as a trigger of inflammation in susceptible hosts, illustrating that the role of these mucolytic organisms can be context-specific.49 Further studies will be needed to clarify these complex host-microbial relationships.

Finally, we found transcriptional evidence for activation of the IDO1 pathway in the affected ileum of Crohn’s Disease patients. Genes regulating the epithelial barrier function of the intestine are dysregulated in IBD and likely contribute to pathogenesis.12 Mucosal healing is a key endpoint in treatment of chronic IBD and requires epithelial restitution. To date, no therapies exist that specifically target the epithelium in IBD. Our study illuminates IDO1 upregulation as a potential target for the treatment of infectious and inflammatory intestinal disorders.

The current study has certain limitations. We show that IDO1 overexpression increases proliferation in mice and expression of stem cell genes in mouse enteroids. However, the nteraction of IDO1, Notch, and the stem-cell state is complex. The ligand, receptor and effector RNA data (Fig S4) is intriguing as it may reflect changes in the stem cell niche including Paneth cells. IDO1 is also overexpressed in the neoplastic epithelium where it interacts with neoplastic signaling pathways (PI3K/Akt) and correlates with poor prognosis in subset of CRC patients.50–52 AHR also has recognized roles in cancer.53 Future studies should be extended to human tissues, and examine the mechanisms and impact of IDO1 overexpression on colon and small intestinal stem cell state/fate, in chronic colitis models, and in tumorigenesis.

In summary, we found that IDO1 promotes secretory cell differentiation and mucus production in the normal intestinal epithelium and implicate a mechanism involving the interaction of IDO1 with AHR and Notch signaling. These findings further highlight the important roles for tryptophan metabolism in mucosal homeostasis including host-microbial interactions and may have implications for a spectrum of intestinal inflammatory and infectious diseases.

Supplementary Material

What you need to know:

BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT:

Indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase (IDO1), a metabolic enzyme, is highly upregulated in the intestinal epithelium during inflammation, injury, and infection. We studied how IDO1 affects epithelial cell differentiation and intestinal inflammation in mice.

NEW FINDINGS:

IDO1 promotes secretory cell differentiation and mucus production in the intestinal epithelium, regulates the microbiota, and reduces epithelial damage. IDO1 interacts with the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) to inhibit activation of Notch1. Levels of IDO1 are increased in ileal tissues from patients with Crohn’s disease and correlate with levels of aryl hydrocarbon receptor and secretory cell markers.

LIMITATIONS:

This study was performed in mice and human tissues and cells. Further studies are required in humans.

IMPACT:

Epithelial IDO1 is important in the response to intestinal injury and might be used in treatment of inflammatory bowel disease and intestinal infections.

Acknowledgments.

We thank Dr. Thaddeus Stappenbeck and Dr. Ta-Chiang Liu for discussion and assistance with the Paneth cell quantification. We thank Dr. Rodney Newberry for manuscript critique and acknowledge Dr. S. Santhanam.

Grant support: DK077653 (PIT and DMA), DK109384 (MAC), DK109081 (KLV), Mucosal Immunology Studies Team Young Investigator Award (MAC), Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation Daniel H Present Senior Research Award (Ref. 370763 to MAC), and philanthropic support from the Givin’ it all for Guts Foundation (https://givinitallforguts.org/, MAC) and the Lawrence C. Pakula MD IBD Research, Innovation, and Education Fund (MAC and DMA). Histology services were provided by the Washington University Digestive Disease Research Core Center and supported by grant P30DK052574. Slide imaging was supported by Shared Instrumentation Grant NCRR 1S10RR027552.

Abbreviations:

- AHR

aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- Cfu

colony forming unit

- CHGA

Chromogranin A

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- DAPT

N-[N-(3,5-Difluorophenacetyl)-L-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester

- DCLK1

Doublecortin like kinase 1

- DSS

dextran sulfate sodium

- E2348/69

Escherichia coli E2348/69

- EGFP

enhanced green fluorescent protein

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- IBD

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- IDO1

Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1

- Kyn

kynurenine

- KP

Kynurenine Pathway

- PAS

periodic acid-Schiff stain

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- TEER

trans-epithelial electric resistance

- TNBS

2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid

- TUNEL

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP Nick-End Labeling

- WT

wildtype

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest:

DMA: No conflicts to disclose. BC: No conflicts to disclose. MI: No conflicts to disclose. AT: No conflicts to disclose. ND: No conflicts to disclose. KLV: No conflicts to disclose. NS, No conflicts to disclose. CKL: No conflicts to disclose. GJG: No conflicts to disclose. PIT: Serves as a consultant to, a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of, and a holder of equity in MediBeacon, a company that is developing technology to detect intestinal permeability and is the potential recipient of royalty payments from this technology. He is also a consultant to Takeda Pharmaceuticals. MAC: received investigator-initiated research funding from Incyte Corporation, maker of Epacadostat, an IDO1 inhibitor in clinical trials.

Contributor Information

David M Alvarado, Division of Gastroenterology, Washington University School of Medicine, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri, USA.

Baosheng Chen, Division of Gastroenterology, Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, USA.

Micah Iticovici, Division of Gastroenterology, Washington University School of Medicine, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri, USA.

Ameet I Thaker, Department of Pathology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas, USA.

Nattalie Dai, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri, USA.

Kelli L VanDussen, Department of Pathology and Immunology, Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, USA.

Nurmohammad Shaikh, Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, & Nutrition, Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, USA.

Chai K Lim, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Macquarie University, Australia.

Gilles J Guillemin, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Macquarie University, Australia.

Phillip I Tarr, Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, & Nutrition, Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, USA.

Matthew A Ciorba, Division of Gastroenterology, Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, USA.

References

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship.

- 1.Sturm A, Dignass AU. Epithelial restitution and wound healing in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2008;14:348–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martini E, Krug SM, Siegmund B, et al. Mend Your Fences: The Epithelial Barrier and its Relationship With Mucosal Immunity in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;4:33–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johansson ME, Hansson GC. Mucus and the goblet cell. Dig Dis 2013;31:305–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganz T Paneth cells--guardians of the gut cell hatchery. Nat Immunol 2000; 1:99–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bjerknes M, Cheng H. Neurogenin 3 and the enteroendocrine cell lineage in the adult mouse small intestinal epithelium. Dev Biol 2006;300:722–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sato T, van Es JH, Snippert HJ, et al. Paneth cells constitute the niche for Lgr5 stem cells in intestinal crypts. Nature 2011;469:415–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moehle C, Ackermann N, Langmann T, et al. Aberrant intestinal expression and allelic variants of mucin genes associated with inflammatory bowel disease. J Mol Med (Berl) 2006;84:1055–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nikolaus S, Schulte B, Al-Massad N, et al. Increased Tryptophan Metabolism Is Associated With Activity of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology 2017;153:1504–1516 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agus A, Planchais J, Sokol H. Gut Microbiota Regulation of Tryptophan Metabolism in Health and Disease. Cell Host Microbe 2018;23:716–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferdinande L, Demetter P, Perez-Novo C, et al. Inflamed intestinal mucosa features a specific epithelial expression pattern of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2008;21:289–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma Ciorba, EE Bettonville, KG McDonald, et al. Induction of IDO-1 by immunostimulatory DNA limits severity of experimental colitis. J Immunol 2010;184:3907–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vancamelbeke M, Vanuytsel T, Farre R, et al. Genetic and Transcriptomic Bases of Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Dysfunction in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017;23:1718–1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta NK, Thaker AI, Kanuri N, et al. Serum analysis of tryptophan catabolism pathway: correlation with Crohn’s disease activity. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012;18:1214–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matteoli G, Mazzini E, Iliev ID, et al. Gut CD103+ dendritic cells express indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase which influences T regulatory/T effector cell balance and oral tolerance induction. Gut 2010;59:595–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen NT, Kimura A, Nakahama T, et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor negatively regulates dendritic cell immunogenicity via a kynurenine-dependent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:19961–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pallotta MT, Orabona C, Volpi C, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase is a signaling protein in long-term tolerance by dendritic cells. Nat Immunol 2011;12:870–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thaker AI, Rao MS, Bishnupuri KS, et al. IDO1 metabolites activate beta-catenin signaling to promote cancer cell proliferation and colon tumorigenesis in mice. Gastroenterology 2013;145:416–25 e1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.VanDussen KL, Marinshaw JM, Shaikh N, et al. Development of an enhanced human gastrointestinal epithelial culture system to facilitate patient-based assays. Gut 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riba A, Olier M, Lacroix-Lamande S, et al. Paneth Cell Defects Induce Microbiota Dysbiosis in Mice and Promote Visceral Hypersensitivity. Gastroenterology 2017;153:1594–1606 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nava GM, Friedrichsen HJ, Stappenbeck TS. Spatial organization of intestinal microbiota in the mouse ascending colon. ISME J 2011;5:627–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alam A, Leoni G, Quiros M, et al. The microenvironment of injured murine gut elicits a local pro-restitutive microbiota. Nat Micro 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Png CW, Linden SK, Gilshenan KS, et al. Mucolytic bacteria with increased prevalence in IBD mucosa augment in vitro utilization of mucin by other bacteria. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:2420–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gomes-Neto JC, Mantz S, Held K, et al. A real-time PCR assay for accurate quantification of the individual members of the Altered Schaedler Flora microbiota in gnotobiotic mice. J Microbiol Methods 2017;135:52–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Savkovic SD, Villanueva J, Turner JR, et al. Mouse model of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli infection. Infect Immun 2005;73:1161–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gurtner GJ, Newberry RD, Schloemann SR, et al. Inhibition of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase augments trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid colitis in mice. Gastroenterology 2003;125:1762–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu F, Dassopoulos T, Cope L, et al. Genome-wide gene expression differences in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis from endoscopic pinch biopsies: insights into distinctive pathogenesis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2007;13:807–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blanc V, Xie Y, Luo J, et al. Intestine-specific expression of Apobec-1 rescues apolipoprotein B RNA editing and alters chylomicron production in Apobec1 −/− mice. J Lipid Res 2012;53:2643–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Austin CJ, Astelbauer F, Kosim-Satyaputra P, et al. Mouse and human indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase display some distinct biochemical and structural properties. Amino Acids 2009;36:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moon C, VanDussen KL, Miyoshi H, et al. Development of a primary mouse intestinal epithelial cell monolayer culture system to evaluate factors that modulate IgA transcytosis. Mucosal Immunol 2014;7:818–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma Sofia, MA Ciorba, K Meckel, et al. Tryptophan Metabolism through the Kynurenine Pathway is Associated with Endoscopic Inflammation in Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2018;24:1471–1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baban B, Chandler P, McCool D, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression is restricted to fetal trophoblast giant cells during murine gestation and is maternal genome specific. J Reprod Immunol 2004;61:67–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shroyer NF, Wallis D, Venken KJ, et al. Gfi 1 functions downstream of Math1 to control intestinal secretory cell subtype allocation and differentiation. Genes Dev 2005;19:2412–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miyoshi H, VanDussen KL, Malvin NP, et al. Prostaglandin E2 promotes intestinal repair through an adaptive cellular response of the epithelium. EMBO J 2017;36:5–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beatty GL, O’Dwyer PJ, Clark J, et al. Phase I study of the safety, pharmacokinetics (PK), and pharmacodynamics (PD) of the oral inhibitor of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO1) INCB024360 in patients (pts) with advanced malignancies. J Clin Oncol 2013;31 (Abstract 3025). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bessede A, Gargaro M, Pallotta MT, et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor control of a disease tolerance defence pathway. Nature 2014;511:184–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang L, Savas U, Alexander DL, et al. Characterization of the mouse Cyp1B1 gene. Identification of an enhancer region that directs aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated constitutive and induced expression. J Biol Chem 1998;273:5174–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.VanDussen KL, Carulli AJ, Keeley TM, et al. Notch signaling modulates proliferation and differentiation of intestinal crypt base columnar stem cells. Development 2012; 139:488–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Es JH, Jay P, Gregorieff A, et al. Wnt signalling induces maturation of Paneth cells in intestinal crypts. Nat Cell Biol 2005;7:381–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Opitz CA, Litzenburger UM, Opitz U, et al. The indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) inhibitor 1-methyl-D-tryptophan upregulates IDO1 in human cancer cells. PLoS One 2011. ;6:e19823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coquerelle C, Oldenhove G, Acolty V, et al. Anti-CTLA-4 treatment induces IL-10-producing ICOS+ regulatory T cells displaying IDO-dependent anti-inflammatory properties in a mouse model of colitis. Gut 2009;58:1363–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zelante T, Iannitti RG, Cunha C, et al. Tryptophan catabolites from microbiota engage aryl hydrocarbon receptor and balance mucosal reactivity via interleukin-22. Immunity 2013;39:372–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lanis JM, Alexeev EE, Curtis VF, et al. Tryptophan metabolite activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor regulates IL-10 receptor expression on intestinal epithelia. Mucosal Immunol 2017;10:1133–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shon W-J, Lee Y-K, Shin JH, et al. Severity of DSS-induced colitis is reduced in Ido1-deficient mice with down-regulation of TLR-MyD88-NF-kB transcriptional networks. Scientific Reports 2015;5:17305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harrington L, Srikanth CV, Antony R, et al. Deficiency of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase enhances commensal-induced antibody responses and protects against Citrobacter rodentium-induced colitis. Infect Immun 2008;76:3045–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bullen TF, Forrest S, Campbell F, et al. Characterization of epithelial cell shedding from human small intestine. Lab Invest 2006;86:1052–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park JH, Lee JM, Lee EJ, et al. Kynurenine promotes the goblet cell differentiation of HT-29 colon carcinoma cells by modulating Wnt, Notch and AhR signals. Oncol Rep 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kang CS, Ban M, Choi EJ, et al. Extracellular vesicles derived from gut microbiota, especially Akkermansia muciniphila, protect the progression of dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. PLoS One 2013;8:e76520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seregin SS, Golovchenko N, Schaf B, et al. NLRP6 Protects Il10(−/−) Mice from Colitis by Limiting Colonization of Akkermansia muciniphila. Cell Rep 2017;19:2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caruso R, Mathes T, Martens EC, et al. A specific gene-microbe interaction drives the development of Crohn’s disease-like colitis in mice. Sci Immunol 2019;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferdinande L, Decaestecker C, Verset L, et al. Clinicopathological significance of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 expression in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2012;106:141–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Santhanam S, Alvarado DM, Ciorba MA. Therapeutic targeting of inflammation and tryptophan metabolism in colon and gastrointestinal cancer. Transl Res 2016;167:67–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bishnupuri KS, Alvarado DM, Khouri AN, et al. IDO1 and Kynurenine Pathway Metabolites Activate PI3K-Akt Signaling in the Neoplastic Colon Epithelium to Promote Cancer Cell Proliferation and Inhibit Apoptosis. Cancer Res 2019;79:1138–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xie G, Raufman JP. Role of the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor in Colon Neoplasia. Cancers (Basel) 2015;7:1436–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.