Abstract

Introduction:

There is keen interest in elucidating the biological mechanisms underlying recent failures of BACE1 inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease trials.

Methods:

We developed a highly sensitive and specific immunoassay for BACE1 in cell lines and iPSC-derived human neurons to systematically analyze the effects of 8 clinically-relevant BACE1 inhibitors.

Results:

Seven of 8 inhibitors elevated BACE1 protein levels. Among protease inhibitors tested, the elevation was specific to BACE1 inhibitors. The inhibitors did not increase BACE1 transcription but extended the protein’s half-life. BACE1 elevated at concentrations below the IC50 for Aβ.

Discussion:

Elevation of BACE1 by 7 of 8 BACE1 inhibitors raises new concerns about advancing such β-secretase inhibitors for AD. Chronic elevation could lead to intermittently uninhibited BACE1 when orally-dosed inhibitors reach trough levels, increasing substrate processing. Compounds like roburic acid that lower Aβ by dissociating β/γ secretase complexes are better candidates because neither inhibit β- and γ-secretase nor increase BACE1.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, β-secretase, BACE1 inhibitor, amyloid β-protein, protein homeostasis

Introduction

The devastating personal impact and growing societal burden of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has led to intense efforts to develop small- and large-molecule therapeutics to modify the disease course. Large-molecule approaches focus principally on monoclonal antibodies intended to clear the amyloid β-protein (Aβ) or the tau protein, accumulation of which can compromise neuronal form and function [1]. Antibody infusions can result in cerebral toxicity, the resultant need for close patient monitoring, and ultimately the logistical challenge of infusing a global AD population. Oral small-molecule approaches are therefore highly desirable, and these have focused to date on inhibiting the β- and γ-secretases which cleave APP to generate Aβ. Most current efforts focus on inhibitors of BACE1 (β-site APP cleaving enzyme-1), which is highly expressed in neurons and is the rate-limiting step in Aβ production. Heterogeneous Aβ peptides are ultimately generated and secreted into interstitial fluid and can accumulate as potentially neurotoxic oligomers and fibrilar amyloid plaques in the brain [2,3]. Pharmacological inhibition of BACE1 has become of great interest to the scientific and medical community [4].

BACE1 is a single-transmembrane aspartyl protease mainly expressed in the central nervous system and concentrated in neuronal presynaptic terminals. The luminal active site of BACE1 cleaves the distal ectodomain of APP, resulting in secretion of a large soluble extracellular fragment called sAPPβ. Subsequent intramembrane cleavage of the remaining C-terminal stub of APP (C99) by the presenilin/γ-secretase complex releases the APP intracellular domain (AICD) into the cytoplasm and Aβ peptides of varying length into the extracellular fluid. Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–43 peptides are highly prone to oligomerization and amyloid formation. Since the initial identification of BACE1 in 1999 [2,3,5,6], it has become the prime drug target for chronically reducing Aβ production in brain. However, despite achieving strong target engagement and up to 80% CSF Aβ reductions, BACE1 inhibitors used in clinical trials on mild-to-moderate AD patients have failed to demonstrate significant slowing of cognitive decline [5]. Moreover, recent detailed analysis of such trials has revealed modest but significant cognitive worsening in patients receiving certain BACE1 inhibitors [7–9]. Considering these disappointing results, it is important to understand BACE1 inhibitor action and its adverse effects in much more detail.

Here, we systematically analyzed the properties of eight BACE inhibitors, 7 of which have already been used in human trials. Unexpectedly, 7 of the 8 inhibitors substantially increased BACE1 protein levels in cells. The most potent compound, AZD3293, was shown to increase the level by prolonging the half-life of BACE1 in a mammalian cell line, in rat primary cortical neurons, and in iPSC-derived human neurons (iNs). In addition, 5 other BACE inhibitors were similarly shown to prolong the half-life of BACE1 in cells. We find that a significant elevation in BACE1 levels consistently accompanies the lowering of Aβ production by several BACE1 inhibitors used in clinical trials. Our results suggest that prolonged increases in total BACE1 protein during chronic dosing could contribute to observed neurological side effects by intermittently augmenting BACE1 proteolytic processing of numerous single-transmembrane substrates important for proper neuronal signaling, in particular when brain levels of the inhibitor fall to trough levels during intermittent oral dosing.

Results

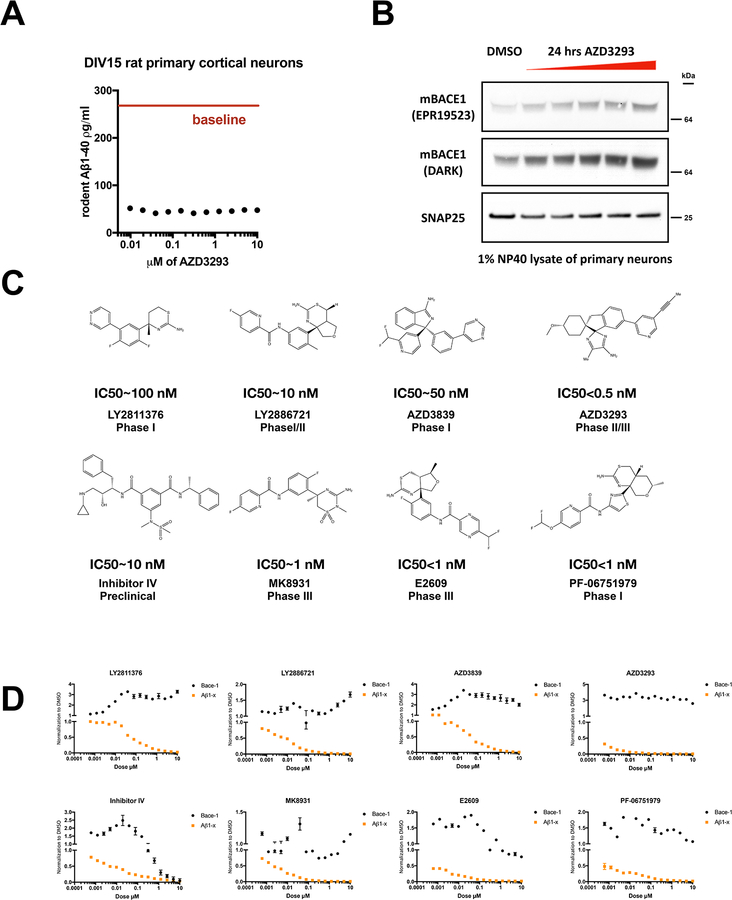

The β-secretase inhibitor AZD3293 increases BACE1 protein levels in rat cortical neurons

BACE1 has emerged as a prime drug target for chronically reducing the levels of Aβ in human brain. AZD3293 (Lanabecestat, AstraZeneca) is a potent BACE1 inhibitor (IC50 = 0.6 ± 0.04 nM) [10,11]. We developed a highly sensitive sandwich immunoassay for rodent Aβ1–40 with a linear standard curve and a lower limit of quantification (LLoQ) on synthetic Aβ1–40 peptide of 2.92 pg/ml (0.7 pM) (Fig. S1A). Treatment of rat primary cortical neurons (DIV15) for 24 hr with AZD3293 at increasing doses (9.7 nM to 10 μM) suppressed up to 80% of endogenous rat Aβ secretion by the cells alreadyat the lowest dose tested (Fig. 1A). We examined by immunoblot BACE1 protein levels in 1% NP40 lysates of the same neurons treated with increasing doses from 625 nM to 10 μM vs. vehicle-only control (DMSO), using SNAP25 as an unchanged neuronal protein control. AZD3293 caused a dose-dependent increase in BACE1 levels (Fig. 1B). To confirm this unexpected finding and further investigate the mechanism behind the robust elevation of BACE1 protein upon AZD3293 treatment, we developed a highly sensitive and specific ELISA on the MesoScale (MSD) platform that quantifies human BACE1 protein (Fig. S1B). The LLoQ of this assay is ~190 pg/ml, and it does not recognize recombinant BACE2 at all (Fig. S1B). We proceeded to use human cells to study the relationship between BACE1 inhibition and BACE1 protein level.

Figure 1. BACE1 inhibitors increase cellular levels of BACE1.

(A) Aβ1–40 in conditioned media measured by ELISA after 24 h treatment of DIV15 rat primary cortical neurons with AZD3293 (doses from 4.9 nM to 10 μM) (n=3, means +/− SD; error bars too small to see). Red solid line: Aβ1–40 level with plain DMSO treatment. (B) Intracellular BACE1 was measured by immunoblot after 24 h treatment of DIV15 rat primary cortical neurons with AZD3293 (doses from 625 nM to 10 μM); SNAP25 serves as a loading control. (C) Structures, IC50s for Aβ1-x and clinical trial phases for eight BACE1 inhibitors. (D) Extracellular Aβ1-x and intracellular BACE1 were quantified by ELISA after 24 h treatment of HEK293-sw cells with the indicated BACE1 inhibitors (doses from 0.6 nM to 10 μM). All values are normalized to DMSO treatment (n=2, means +/− SD; some error bars too small to see).

Seven BACE1 inhibitors upregulate BACE1 protein levels in a human cell line

Numerous inhibitors of BACE1, including AZD3293, have been considered for human use, and seven have progressed into Phase 2 or 3 clinical trials [12,13]. We tested seven clinical candidates, along with the first reported non-peptidic BACE1 inhibitor, called inhibitor IV. Their structures, IC50s for Aβ1-x, and clinical trial phases are provided in Fig. 1C. Human HEK-293 cells stably expressing the “Swedish” FAD mutant KM670/671NL (sw) APP but only endogenous β- and γ-secretases were treated for 24 h with each of the eight BACE1 inhibitors over a wide range of concentrations (Fig. 1D). We observed robust, dose-dependent reductions of Aβ1-x levels (a surrogate for total Aβ) in the conditioned media, demonstrating the potency of these inhibitors. Unexpectedly, we found that seven out of eight inhibitors significantly elevated cellular BACE1 protein levels to varying degrees, as quantified by our home-brew BACE1 ELISA that we optimized on the MSD platform. While seven out of eight compounds variably elevated BACE1 protein levels, one of them, AZD3293, markedly increased BACE1 to 360% of vehicle at the lowest dose tested (0.6 nM), and the high elevation persisted virtually throughout the dose curve, revealing a particularly sensitive response of cellular BACE1 to this compound. Moreover, we tried to use even lower doses for AZD3293, as 0.6 nM is already higher than its IC50 for Aβ1-x in our cells. As shown in Fig. S1C, we tested AZD3293 from 0.58 fM to 10 μM, and we observed that 0.9 pM could barely inhibit Aβ generation (10% inhibition) but already caused a clear increase in intracellular BACE1 levels (50% elevation). Inhibitor IV is noteworthy as it showed a bell-shaped curve for cellular BACE1 levels as its dosage increased (Fig. 1D). A similarly striking finding was that at a 10 nM dose, LY2811376 could barely inhibit Aβ generation but already caused a clear increase in intracellular BACE1 (Fig. 1D), which suggested non-synchronized effects of this BACE1 inhibitor. To assess whether an inhibitor selective for BACE1 would also elevate the protease, we examined the recently developed PF-06751979 that is reported to have good BACE1 selectivity (BACE1 IC50=7.3 nM; BACE2 IC50=193 nM [14]). We observed a similar elevation of BACE1 protein. MK8931 had little or no effect on BACE1 levels despite its dose-dependent inhibition of Aβ production. To confirm the BACE1 ELISA findings, we immunoblotted cell lysates for BACE1 and found a similar increase in protein level upon treatment with AZD3293 (Fig. S1D). As expected, no BACE1 protein was detected in the conditioned media of cells treated with BACE1 inhibitors vs. vehicle (DMSO) alone (data not shown), ruling against gross cytotoxicity under our experimental conditions.

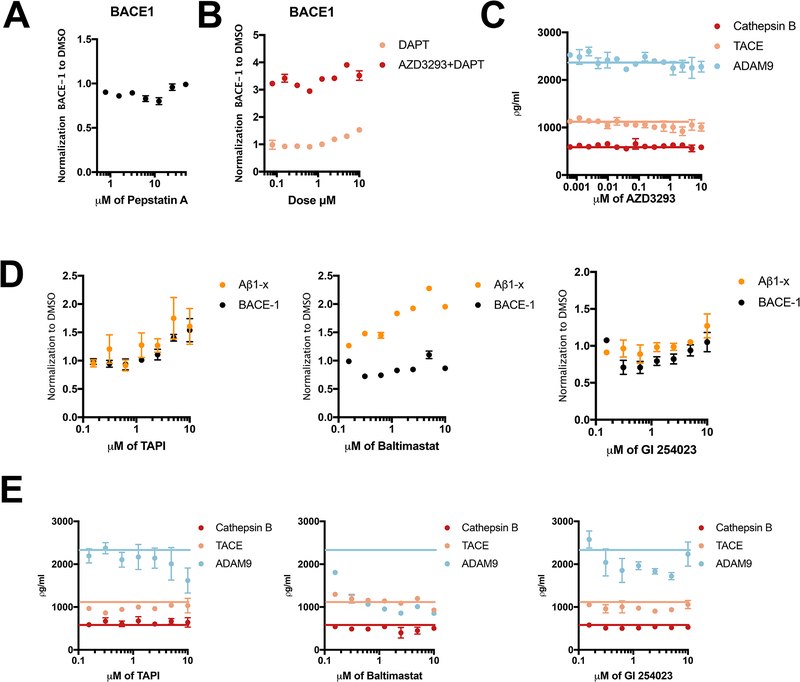

Upregulation of BACE1 protein levels upon inhibition of BACE1 is unique and specific

We asked whether the cellular BACE1 elevation might result from aspartyl protease inhibition per se. We tested a broad-spectrum aspartyl protease inhibitor, Pepstatin A, as to whether general inhibition of aspartyl proteases leads to a similar effect. Doses ranging from 780 nM to 50 μM did not alter BACE1 cellular levels (Fig. 2A). Next, we tested DAPT, a potent inhibitor of the intramembrane aspartyl protease, γ-secretase, to test whether its inhibition led to a similar effect. Only the highest dosage tested (10 μM) elevated BACE1 protein level by ~50% vs. plain DMSO; doses <5 uM had no significant effect (Fig. 2B). In accord, there was no difference between co-treating cells with DAPT plus AZD3293 vs. with AZD3293 alone (Fig. 2B). We then asked whether the elevation of BACE1by AZD3293 was specific to the BACE1 protease: could AZD3293 change the cellular levels of two matrix metalloproteinases (ADAM9, TACE) or the cysteine protease Cathepsin B. AZD3293 had no effect on the three proteases tested (Fig. 2C). Conversely, we examined three matrix metalloproteinases inhibitors, TAPI, GI 254023X and Batimastat, for any effects on BACE1. GI-254023X and Batimastat had no effect on BACE1 levels, but TAPI increased the BACE1 level at high doses of 2.5, 5 and 10 μM (Fig. 2D). However, the IC50s of TAPI for endogenous and overexpressed sAPPα generation are reported to be 1.2 and 0.92 μM, respectively [15], so TAPI’s elevation of BACE1 levels occurs well above its IC50. Next, we investigated whether inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases (TAPI, GI 254023X and Batimastat) could change the cellular levels of two matrix metalloproteinases or the cysteine protease Cathepsin B. We quantified ADAM-9, TACE and Cathepsin B protein levels in HEK cell lysates by ELISA (Fig. 2E). The three metalloprotease inhibitors did not significantly change the cellular levels of TACE or Cathepsin B. Regarding ADAM-9, Batimastat significantly reduced ADAM-9 protein levels at all doses beginning as low as 156 nM, while GI 254023X produced lowering of ADAM9 only at certain doses (Fig. 2E). Therefore, 7 out of 8 BACE1 inhibitors substantially elevate BACE1 protein levels, and among the other classes of protease inhibitors we tested, only TAPI did this but only modestly and at doses well above its IC50. These data support the specificity of the effect of BACE1 inhibitors in elevating BACE1 levels.

Figure 2. The elevated cellular level of BACE1 is specific to BACE1 inhibitor treatment.

(A) Intracellular BACE1 were measured by ELISA after 24 h treatment of HEK293-sw cells with Pepstatin A (doses from 790 nM to 50 μM). All values are normalized to DMSO treatment (n=3, means +/− SD; some error bars too small to see). (B) Cellular BACE1 was measured by ELISA after 24 h treatment of HEK293-sw cells with DAPT or else DAPT plus AZD3293 (doses from 78 nM to 10 μM). All values are normalized to DMSO treatment (n=2, means +/− SD; some error bars too small to see). (C) Cellular Cathepsin B, TACE, and ADAM9 were measured by ELISA after 24 h treatment of HEK293-sw cells with AZD3293 (doses from 0.6 nM to 10 μM) (n=2, means +/− SD; some error bars too small to see). Blue, orange and red lines: Cathepsin B, TACE, and ADAM9 levels with plain DMSO treatment, respectively. (D) Extracellular Aβ1-x and intracellular BACE1 were measured by ELISA after 24 h treatment of HEK293-sw cells with different compounds; all values normalized to DMSO treatment (n=2, means +/− SD; some error bars too small to see). (D) Cellular Cathepsin B, TACE, and ADAM9 were measured by ELISA after 24 h treatment of HEK293-sw cells with different compounds. Blue, orange and red lines: Cathepsin B, TACE, and ADAM9 levels with plain DMSO treatment, respectively.

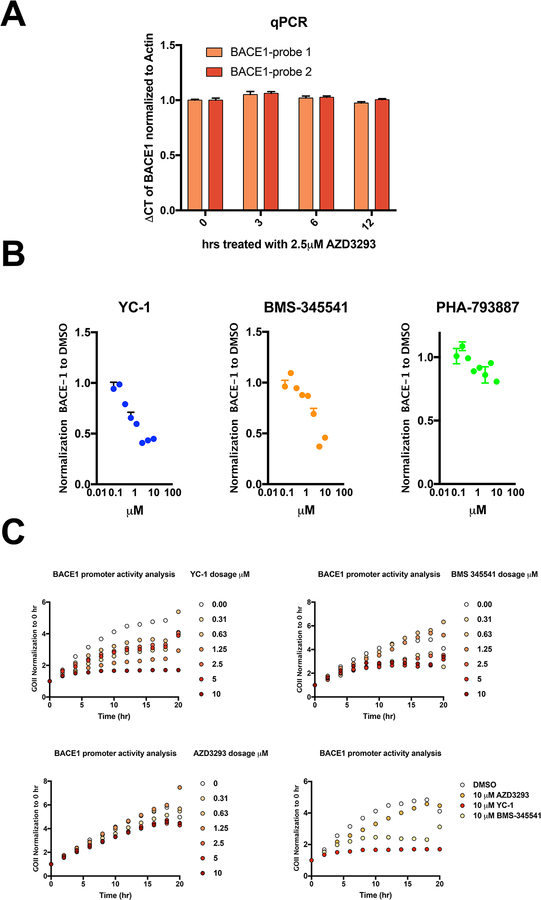

AZD3293 does not change BACE1 transcription

To further explore the clear evidence that BACE1 inhibitors can increase intracellular BACE1 protein levels, we investigated the mechanism of this unexpected finding. First, we suspected that AZD3293 would increase the transcription of BACE1 mRNA, as BACE1 was known to be regulated by diverse transcription factors [16], including SP-1, HIF-1α, NF-kappaB and cdk5/P25. Taking into consideration that a change in the mRNA might occur rapidly, we treated HEK293-sw cells with AZD3293 at 2.5 μM, a dose that markedly increases cellular BACE1 protein, for 3, 6 or 12 hr. Total RNA was extracted from cells treated with AZD3293 vs. just DMSO, followed by reverse transcription. qPCR was used to quantify mRNA of BACE1, and β-actin served as a control for normalization. AZD3293 treatment at all time points did not change levels of BACE1 mRNA after carefully testing two independent sets of qPCR probes for BACE1 (Fig. 3A). To confirm this finding, we constructed and transfected into HEK293 cells a plasmid containing the open reading frame of GFP under the regulation of the 5’UTR of the human BACE1 gene (−1471 to +152 bp; transcription start site is designated +1, which is 457 bp from the translation start site) and monitored the promoter activity (GFP reporter) in real time using a live-cell automated imaging system (IncuCyte by Sartorius). To validate this assay, we first confirmed that two compounds, YC-1 and BMS-345541, which target HIF-1α and NF-kappaB signaling respectively, dose-dependently reduced BACE1 protein levels, with PHA-793887 (a potent CDK inhibitor) as a negative control (Fig. 3B). Then we transiently expressed the BACE1 5’UTR-GFP reporter construct in HEK293-sw cells in a 96-well format and followed treatment over time with increasing doses of YC-1, BMS-345541 or AZD3293 vs. vehicle (DMSO) alone. GFP signals from the cells were captured every hour up to 20 hr, and the normalized GFP intensity was calculated from each well. As expected, we observed increasing GFP expression over time in just DMSO, and YC-1 or BMS-345541 treatments could each dose-dependently suppress this time-dependent rise in GFP intensity (Fig. 3C, upper panels). In contrast, AZD3293 treatment did not change the BACE1-driven GFP expression vs. DMSO alone (Fig. 3C, lower panels), confirming the negative qPCR results.

Figure 3. BACE1 inhibitors do not change BACE1 transcription level.

(A) BACE1 mRNA levels were measured by qPCR using two different probes after 0, 3, 6 and 12 h treatment of HEK293-sw cells with 2.5 μM AZD3293. (B) Cellular BACE1 was quantified by ELISA after 24 h treatment of HEK293-sw cells with the indicated compounds (doses from 78 nM to 10 μM). All values are normalized to DMSO treatment (n=2, means +/− SD; some error bars too small to see). (C) BACE1 promoter activity was measured by a GFP reporter during 20 h treatment of HEK293-sw cells with different compounds (IncuCyte automated live-cell imaging).

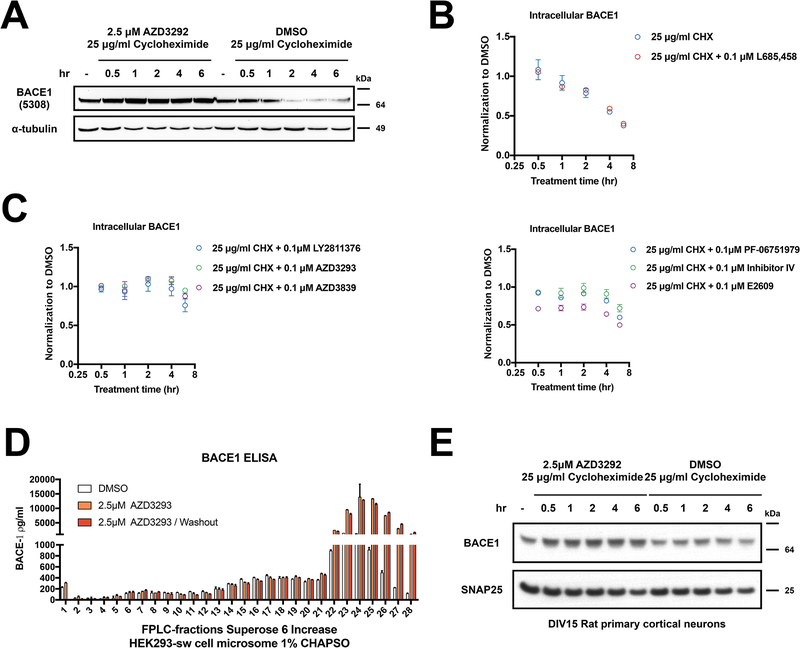

AZD3293 extends the half-life of the BACE1 protein

Next, we asked whether AZD3293 acted by stabilizing BACE1 protein from degradation. A cycloheximide (CHX) chase assay (used to block new protein synthesis) indicated that 1) the half-life of endogenous BACE1 is around 2–4 hr, as estimated in HEK-293 cells conditioned in DMSO vs. CHX (25 μg/ml); and 2) co-treatment with CHX and 2.5 μM AZD3293 revealed stabilization of the endogenous BACE1 protein from degradation, as assessed by western blot (Fig. 4A). To better quantify the effects of BACE1 inhibitors on BACE1 protein stability, we used our BACE1 ELISA and treated HEK-293 cells with CHX plus one of six BACE1 inhibitors, each at the low dose of 0.1 μM, or else with L685,458 (a γ-secretase inhibitor) as a negative control. We observed similar declines of BACE1 levels with CHX alone and CHX plus L685,458 over 6 hours of treatment (Fig. 4B), confirming the ~4 hr half-life of BACE1 and showing that another aspartyl protease inhibitor (L685,458) had no effect on it. Co-treating the cells with CHX plus each of the six BACE1 inhibitors showed that BACE1 was strongly stabilized by LY2811376, AZD3293 and AZD3839 compared to CHX alone (Fig. 4C, left panel), and it was moderately stabilized by PF-06751979, Inhibitor IV and E2609 (Fig. 4C, right panel). We conclude that all BACE inhibitors tested increased cellular BACE1 levels by stabilizing the protein from degradation. To further validate this finding, we tested whether AZD3293 could enhance the stability of exogenous BACE1. Here we overexpressed wild-type BACE1 transiently in HEK-293 cells and treated the cells with increasing doses of AZD3293. As shown in Fig. S2A, all doses elevated the BACE1 protein levels 1.5–2 fold. The ELISA-measured absolute level of this exogenously-expressed BACE1 (~1.2 μg/ml) was ~2000 times that of endogenous BACE1 (~500 pg/ml) in HEK-293 cells, so it is surprising that AZD3293 could still stabilize an already very high cellular level of BACE1. To further explore the nature of this increase in BACE1 protein, we fractionated microsomes of 1% CHAPSO-solubilized HEK-293 cell lysatesby size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) after treating the cells with AZD3293 (2.5 μM) for 24 hr (vs. just DMSO vehicle), using a Superose 6 Increase gel filtration column. Each SEC fraction was lyophilized and used to measure BACE1 levels by ELISA (Fig. 4D). Treating the cells with AZD3293 for 24 hr increased BACE1 protein levels by a striking 4–15 fold in the low MW (<150 kDa) SEC fractions #23–28, without changing them in the high MW (>670 kDa) fractions #6–13 (all as compared to treating with vehicle alone). The BACE1 elevating effect of AZD3293 remainedeven after removing and washing out the compound for 24 hr (Fig. 4D). Next, we performed subcellular fractionation of cell homogenates by ultracentrifugation on a discontinuous iodixanol gradient (Fig. S2B). We found a high AZD3293-mediated accumulation of BACE1 in EEA1+ and Rab11a+ fractions, which thus are enriched in endosomes. Placing these last two findings in context, we recently documented in cultured cells, mouse brain and human brain the existence of an endogenous, proteolytically active HMW β/γ secretase complex of ~5 MDa that can mediate sequential cleavages of holo-APP substrate to generate cellular Aβ [17]. We also documented a low MW (<150 kDa) pool of BACE1 that lacks γ-secretase and therefore cannot contribute to Aβ generation [17]. The AZD3293-induced increase in BACE1 occurred selectively in this LMW pool of the protease (Fig. 4D). Moreover, AZD3293 did not noticeably alter the subcellular distribution of BACE1 (Fig. S2B). Thus, a BACE1 inhibitor appears to increase the pool of non-Aβ generating BACE1 localized in part to endosomes. Next, we tested AZD3293 effects on BACE1 stability in rat primary cortical neurons (DIV 15) using the same CHX chase assay. The half-life of BACE1 was longer in the primary neurons, where 6 hr of CHX treatment alone decreased cellular BACE1 levels by only ~20%. However, AZD3923 co-treatment with CHX did stabilize BACE1 protein levels in the primary neurons (Fig. 4E).

Figure 4. BACE1 inhibitors extend BACE1 half-life.

(A) Cellular BACE1 levels were measured by immunoblot after treatment of HEK293-sw cells with 25 μg/ml cycloheximide together with either DMSO or 2.5 μM AZD3293 for 0.5, 1, 2, 4 and 6 h. α-Tubulin serves as loading control. (B-C) Cellular BACE1 levels were measured by ELISA after treatment of HEK293-sw cells with 25 μg/ml cycloheximide together with either DMSO or 0.1 μM L685,458 (negative control) or else 0.1 μM of six different BACE1 inhibitors (LY2811376, AZD3839, AZD3293, PF −06751979, Inhibitor IV, E2609) for 0.5, 1, 2, 4 and 6 h. (n=3; means +/− SD) (D) BACE1 ELISA of FPLC fractions from HEK293-sw cells treated with AZD3293 for 24 h or else AZD3293 for 24 h followed by another 24 h wash out with medium only (n=2; means +/− SD). (E) Cellular BACE1 level were measured by immunoblot after treatment of rat primary cortical neurons (DIV15) with 25 μg/ml cycloheximide plus DMSO or 2.5 μM AZD3293 for 0.5, 1, 2, 4 and 6 h. SNAP25 serves as loading control.

β-secretase inhibitors upregulate BACE1 protein levels in iPSc-derived human neurons

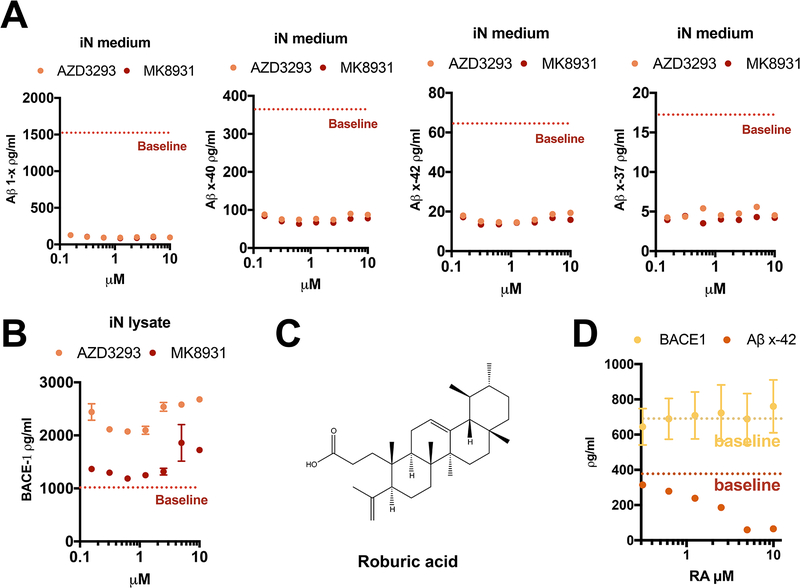

Next, we asked whether the elevation of BACE1 by its inhibitors could be observed in human neurons. We treated iPSC-derived, neurogenin-induced wildtype human neurons (iNs) at DIV 23 with AZD3293 or MK8931; these two compounds had shown similar potency for decreasing Aβ production in HEK293 cells (Fig. 1D). In the human neurons, we assayed six different Aβ peptides, using novel Aβ assays that we developed for this study. Both inhibitors decreased the peptides Aβ1-x, Aβx-37, Aβx-38, Aβx-40 and Aβx-42 by >90%, beginning at even the lowest dose tested (Fig. 5A). Aβx-43 could only be detected in the medium of the DMSO-treated cells (12.0 ± 2.6 pg/ml, mean +/− SD, n=3) and became undetectable after treatment with either inhibitor (not shown). AZD3293 elevated human neuronal BACE1 protein levels robustly, while MK8931 only had an effect at high doses (Fig. 5B). Thus, augmentation of BACE1 protein levels by β-secretase inhibitors is shared by rat primary cortical neurons, human HEK cells and wildtype human neurons. Recently, we examined a group of natural triterpenoids, including roburic acid (RA), that can serve as novel Aβ-reducing reagents by disrupting the newly identified HMW β/γ secretase complex, without inhibiting either β or γ secretase proteolytic activity [17]. In accord with this report, increasing doses of RA from 312.5 nM to 10 μM decreased Aβx-42 secretion from iNs without changing the neuronal BACE1 level (Fig. 5D). Further screening of compounds such as RA will be an alternative approach to bypass the known liabilities of secretase inhibition, including BACE1 inhibitors and γ-secretase inhibitors.

Figure 5. Roburic acid decreases Aβ generation from human neurons without alteration of BACE1 levels.

(A, B) Extracellular Aβs (A) and intracellular BACE1 (B) were measure by ELISA after 24 h treatment of neurogenin-induced human neurons with AZD3293 or MK8931 (dosages from 150 nM to 10 μM; n=2, means +/− SD; some error bars too small to see). Red dotted line: Aβ1-x level with plain DMSO treatment. (C) Structure of roburic acid. (D) Extracellular Aβ x-42 and intracellular BACE1 were measure by ELISA after 24 h treatment of iN cells with roburic acid (dosages from 312 nM to 10 μM) or DMSO (n=2, means +/− SD; some error bars too small to see). Yellow and red dotted lines: BACE1 and Aβ x-42 levels with plain DMSO treatment, respectively.

Discussion

Despite efforts to address the specificity of BACE1 inhibitors in treating AD, even the most advanced compounds have not achieved optimal on-target specificity for lowering Aβ. The problem arises from the similarity between the proteolytic sites of BACE1 and many other human aspartic proteases. There has been progress in addressing the issue of non-selective inhibition of cathepsin D and E and BACE2 but not yet on the non-selective inhibition of processing of BACE1 substrates besides APP, which are known to be important for diverse biological functions [18,19]. Among the BACE1 inhibitors entered into Phase III or Phase II/III clinical trials, it has been shown that 1) AZD3293 inhibits BACE1 and BACE2 with equal potency; 2) MK8931 inhibits BACE2 more potently than BACE1, which is supported by the trial data on altered hair color (a BACE2 inhibition phenotype) [20]; and 3) the inhibition of APP processing does not spare other critical BACE1 substrates such as Sez6 [21]. Of great concern is the cognitive worsening revealed recently in some BACE1 inhibitor trials[7–9]. Its origin is unclear, but it may be consistent with in-depth analyses of BACE1 knock-out mice that have notable neurological phenotypes which include but are not limited to seizures, schizophreniform behavior, cognitive dysfunction and impaired axonal organization [22–25].

Conceptually, therapeutic BACE1 inhibition attempts to decrease newly generated Aβ monomers to lower Aβ oligomer formation over time and thus lessen neuronal and glial cytotoxicity and slow cognitive decline. However, targeting the rate-limit enzyme that normally generates Aβ may not efficiently slow or reverse the growth of established plaques [26]. Moreover, even initiating treatment earlier than prodromal AD may be ineffective, since monomer lowering may not correct a decades-long dyshomeostasis of Aβ and could also lead to gradual accrual of adverse effects. Our analysis of 8 BACE1 inhibitors strongly support the latter concern, as we observed a surprising and unwanted effect with almost all BACE1 inhibitors we tested: they increase cellular BACE1 protein levels by extending the half-life of BACE1 itself. Beyond the reported side effects potentially arising from inhibition of BACE2 or decreased physiological processing of other BACE1 substrates, our new findings show that potent BACE1 inhibitors increase the stability of the protease, suggesting that chronic BACE1 inhibition could elevate the protease so that the usual peaks and valleys of tissue levels of an orally dosed inhibitor could permit intermittent over-processing of BACE1 substrates.

Our experiments show that AZD3293 is a highly potent BACE1 inhibitor that can suppress up to 80% of endogenous Aβ1–40 production by rat primary cortical neurons (DIV15) while simultaneously increasing BACE1 protein levels in the neurons. We confirmed that upregulation of BACE1 by AZD3293 occurs in wild-type human neurons. Testing the additional 7 BACE1 inhibitors, we observed robust reductions of Aβ1-x levels (a proxy for total Aβ) in the conditioned media, confirming the potency of these inhibitors. But the inhibitors unexpectedly and significantly elevated cellular BACE1 protein levels to varying degrees. Moreover, while 7 out of 8 compounds elevated BACE1 protein levels, one inhibitor, AZD3293, markedly increased its levels to 360% of vehicle already at the lowest dose tested (0.6 nM), and this high elevation persisted virtually throughout the dose curve, revealing a particularly sensitive response of cellular BACE1 to this compound. We have confirmed this surprising phenomenon in HEK293-sw cells, rat primary neurons and human neurons. Mechanistically, we initially focused on AZD3293 and found it increased BACE1 protein level by extending the half-life of BACE1, as seen by CHX chase assays. We ruled out AZD3293 elevation of BACE1 transcription through qPCR, a BACE1 promoter activity assay, and a test of AZD3293 effects on exogenously expressed BACE1 lacking the cognate promoter and enhancer sequences. Thus, BACE1 elevation by AZD3293 occurs by stabilizing the enzyme at the protein level, and we showed this is a general class effect by quantifying the prolonged half-life of BACE1 by 5 other BACE inhibitors using cycloheximide chase assays. Intriguingly, when cell lysates were fractioned under non-denaturing conditions, the increased BACE1 protein occurred in LMW biochemical fractions, which we recently showed lack PS/γ-secretase complexes and thus cannot contribute to Aβ production [17]. The increasing levels of BACE1 are of special concern; excess BACE1 that is intermittently uninhibited could both generate additional Ab from APP and excessively processmany BACE1 substrates involved, for example, in sodium channel function [27], synaptic formation [28] and immunity [29].

In light of the reported clinical failures of semagacestat [30], a γ-secretase inhibitor, and verubecestat [20], a β-secretase inhibitor, inhibition of the secretases for prolonged treatment of AD will be highly challenging. There remain substantial uncertainties about the enzymology during the high-affinity bindings of inhibitors to the secretases. For example, semagacestat was shown retrospectively to actually increase intracellular accumulation of the longer Aβ43, 45 and 46 peptides rather than inhibiting γ-secretase [31]. It is difficult to choose a safe dosage when BACE1 inhibitors act as potentially neurotoxic agents. However, we believe that other small molecule therapies directed at Aβ are still important and attractive for prevention and treatment of AD. In particular, recent developments in the field of γ-secretase modulators (GSMs) are promising, including the oral GSMs BPN-15606 (IC50 ~7 nM for Aβ42) [32], PF-06442609 (IC50 ~6 nM) [33], and Compounds 30, 44, 45 (IC50s as low as 4.9 nM) [34]. Allosteric modulation of γ-secretase by GSMs will not alter the endo-proteolytic activity of γ-secretase and therefore will not impair signaling mediated by the intracellular domains of many α- β- and γ-secretase substrates but rather will shift APP cleavage to decrease longer, more amyloidogenic Aβ peptides (Aβ43, 42 and 40) and increase shorter, less aggregation prone peptides (Aβ37 and 38). This precise targeting of longer Aβ species by GSMs is likely to be both safer and more effective in lessening Aβ oligomerization and plaque formation. And as a distinct new small-molecule approach, we recently discovered a natural triterpenoid, roburic acid, that lowers Aβ42 and Aβ43 by a) modulating γ-secretase activity similar to a GSM, and b) decreasing the generation of all Aβ peptides by partially dissociating a high MW β/γ secretase complex that generates cellular Aβ, without inhibiting either secretase [17]. Based on these properties, we and others will now screen for additional natural compounds that have one or both of these mechanisms.

In summary, in the context of previous studies on BACE1 physiological functions and the adverse effects of BACE1 inhibitors in recent trials, our new finding that numerous BACE1 inhibitors significantly elevate cellular levels of the protease further complicates the advance of β-secretase inhibition as a chronic treatment for Alzheimer’s disease.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

LY2886721, LY2811376, AZD3293, AZD3839, MK-8931, Pepstatin A, TAPI-1, Batimastat and DAPT were from Selleckchem; E2609 was from Sun-Shine Chemical; PF-06751979 was from MedChemExpree; β-secretase inhibitor IV was from Millipore; GI 254023X was from TOCRIS; Roburic acid was from Aobious; synthetic β-amyloid peptides are all from Anasepc; and recombinant human BACEl and BACE2 protein was from R&D system.

Cell Culture

Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK) cells were maintained in standard medium: Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium plus 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 100 units/ml penicillin. For our HEK293/sw-APP cell line, which overexpresses FAD-mutant human swAPP, standard medium was supplemented with G418. For the Neurogenin 2-iN (iN) differentiation, iPSCs were differentiated following a published protocol [35]. Cultures were treated with doxycycline (2 mg/mL) on day 1 to induce differentiation, fed with a series of medium changes, treated at day 23 and harvested at day 24. Primary cortical neuronal cultures were prepared from Wistar rat embryos (E18).

Microsome preparations from cultured cells

For microsomes from cultured cells, the cells were first Dounce-homogenized with a tight pestle in TBS containing no detergent with 15 strokes, followed by passage through a 27.5-gauge needle four times. Samples were then centrifuged at 1,000 x g followed by a 100,000-x g ultracentrifuge spin to pellet microsomes, which were solubilized in 50 mM Hepes buffer, 150 mM NaCl containing 1% CHAPSO for 60 min, followed by another 100,000-x g spin to collect the final supernatant.

Electrophoresis and WB

Samples were loaded onto 4–12% Bis-Tris gels using MES-SDS running buffer (Invitrogen), transferred to PVDF membranes, and probed for various proteins using standard WB. The resultant blots were detected by ECL and signals were captured by the iBright system (Invitrogen) or film. The antibodies used to detect specific antigens were: for mouse BACE1, EPR19523 (rabbit, Abcam); for human BACE1, MAB5308, (mouse, Millipore, RRID: AB_95207); for SNAP-25, 610366, (mouse, BD, RRID: AB_397752); and for α-tubulin, T5168 (mouse, Sigma, RRID: AB_477579).

RNA extraction and qPCR

Total RNA was extracted with Trizol reagent. mRNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using WarmStart® RTx Reverse Transcriptase. qPCR was done with Powerup SYBR green master mix. 2 sets of primers for BACE1 were used, set (1) 5’-TGATCATTGTGCGGGTGGAGA- 3’ and 5’-TGATGCGGAAGGACTGGTTGGTAA- 3’; set (2) 5’-ACTCCCTGGAGCCTTTCTTTG- 3’ and 5’-ACTTTCTTGGGCAAACGAAGGTTGGTG- 3’. Primers for actin were used for normalization of mRNA amount: 5’-AGAGCTACGAGCTGCCTGAC- 3’ and 5’-AGCACTGTGTTGGCGTACAG- 3’.

SEC

Microsomes isolated from cultured cells were solubilized in 1% CHAPSO (350 μl total volume), injected onto a Superose 6 Increase 10/300 column (24-ml bed volume) and run on a fast protein liquid chromatography system (AKTA; GE Healthcare) in 50 mM Hepes buffer, 150 mM NaCl with 0.25% CHAPSO, pH7.4. 500-μl fractions were collected for downstream experiments. Columns were calibrated with Gel Filtration Standard (Bio-rad), which ranges from 1,350 to 670,000 Da.

ELISA

Conditioned culture medium and cell lysate were diluted with 1% BSA in wash buffer (TBS supplemented with 0.05% Tween). For our home-made MSD electrochemiluminescence platform, each well of an uncoated 96-well multi-array plate (Meso Scale Discovery, #L15XA-3) was coated with 30 L of a PBS solution containing capture antibody (3 μg/ml 266 for all human Aβ ELISAs, 3 μg/ml M3.2 for rodent Aβ ELISAs, and 7.2 μg/ml MAB931 for BACE1 ELISA) and incubated at room temperature (RT) overnight followed by blocking with 5% BSA in wash buffer for 1h at RT with shaking at >300 rpm. A detection antibody solution was prepared with biotinylated detection antibody, 100 ng/mL Streptavidin Sulfo-TAG (Meso Scale Discovery, #R32AD-5), and 1% BSA diluted in wash buffer. Following the blocking step, 50 μL/well of the sample, followed by 25 μL/well of detection antibody solution were incubated for 2 h at room temperature with shaking at >300 rpm, washing wells with wash buffer between incubations. The plate was read and analyzed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The antibodies used to detect specific antigens were for Aβ (1–37 specific), D2A6H, (rabbit, CST): for Aβ (1–38 specific), 67B8, (mouse, SYSY, RRID: AB_11043334); for hAβ (l-40 specific), HJ-2, (mouse, homemade); for mAβ (l-40 specific), 805901, (rabbit, Biolegend); for hAβ (1–42 specific), 21Fl2, (mouse, homemade); for hAβ (1–43 specific), 18584, (rabbit, IBL, RRID: AB_2341377); and for BACE1 BAF931 (goat, R&D system). For TACE, Cathepsin B and ADAM9, commercial ELISAs from R&D Systems were used according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Performance of rodent Aβ1–40 and BACE1 immunoassays. (A) Standard curve of rodent Aβ1–40 assay; green dotted line: LLoQ. (B) Standard curve of BACE1 assay; green dotted line: LLoQ. (C) Extracellular Aβ1-x peptides and cellular BACE1 levels were measured by ELISA after 24 h treatment of HEK293-sw cells with AZD3293 (doses from 0.58 fM to 10 μM). All values are normalized to DMSO treatment alone (n=2, means +/− SD; most error bars are too small to see). (D) Cellular BACE1 levels were measured by immunoblot after 24 h treatment of HEK293-sw cells with 2.5 μM AZD3293 or DMSO; α-Tubulin serves as loading control (n=3; means +/− SD; unpaired Student’s t-test: **, P<0.01.

Figure S2. AZD3293 does not alter BACE1 subcellular distribution. (A) Cellular BACE1 levels were measure by ELISA after 24 h treatment of HEK293-sw cells transiently overexpressing BACE1 with AZD3293 (dosages from 150 nM to 10 μM). All values are normalized to DMSO treatment alone (n=3; means +/− SD). (B) Immunoblots of BACE1, EEA1, Rab11a and APP from iodixanol fractions after 24 h treatment of HEK293-sw cells with 2.5 μM AZD3293 or DMSO.

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Systematic review: Recent research suggests that several BACE1 inhibitors can worsen cognitive functions in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients. The biological mechanisms are largely unknown.

Interpretation: Using highly sensitive assays and systematic evaluation of 8 clinically-relevant BACE1 inhibitors, we find that 7 BACE1 inhibitors elevate levels of BACE1 in cells. These BACE1 elevation effects are specific and unique for BACE1 inhibitors and act by extending BACE1 half-life.

Future directions: Future studies should investigate compounds like roburic acid, which reduce Aβ generation by partially dissociating a high MW β/γ secretase complex that generates cellular Aβ without inhibiting either secretase.

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Ramalingam and M. Liao for providing rat cortical neurons and iN cells. We are grateful to members of the Selkoe laboratory for helpful discussions.

This work was funded by NIH grants R01 AG06173 (DJS), P01 AG015379 (MSW and DJS) and R03 AG063046 (LL).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interests

DJS is a director and consultant to Prothena Biosciences. The other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Quantification and statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 7 software. Statistical details of experiments are described in the text and/or figure legends.

References

- [1].Selkoe DJ, Hardy J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol Med 2016;8:595–608. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Vassar R, Bennett BD, Babu-Khan S, Kahn S, Mendiaz EA, Denis P, et al. β-Secretase cleavage of Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor protein by the transmembrane aspartic protease BACE. Science (80- ) 1999;286:735–41. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Yan R, Blenkowski MJ, Shuck ME, Miao H, Tory MC, Pauley AM, et al. Membrane-anchored aspartyl protease with Alzheimer’s disease β- secretase activity. Nature 1999. doi: 10.1038/990107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Yan R, Vassar R. Targeting the β secretase BACE1 for Alzheimer’s disease therapy. Lancet Neurol 2014;13:319–29. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70276-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sinha S, Anderson JP, Barbour R, Basi GS, Caccaveffo R, Davis D, et al. Purification and cloning of amyloid precursor protein β-secretase from human brain. Nature 1999. doi: 10.1038/990114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lin X, Koelsch G, Wu S, Downs D, Dashti A, Tang J. Human aspartic protease memapsin 2 cleaves the beta -secretase site of beta -amyloid precursor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bump in the Road or Disaster? BACE Inhibitors Worsen Cognition. AlzForum 2018. https://www.alzforum.org/news/conference-coverage/bump-road-or-disaster-bace-inhibitors-worsen-cognition. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Egan MF, Kost J, Voss T, Mukai Y, Aisen PS, Cummings JL, et al. Randomized Trial of Verubecestat for Prodromal Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med 2019;380:1408–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Henley D, Raghavan N, Sperling R, Aisen P, Raman R, Romano G. Preliminary Results of a Trial of Atabecestat in Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med 2019;380:1483–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1813435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Eketjäll S, Janson J, Kaspersson K, Bogstedt A, Jeppsson F, Fälting J, et al. AZD3293: A Novel, Orally Active BACE1 Inhibitor with High Potency and Permeability and Markedly Slow Off-Rate Kinetics. J Alzheimer’s Dis 2016. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sakamoto K, Matsuki S, Matsuguma K, Yoshihara T, Uchida N, Azuma F, et al. BACE1 Inhibitor Lanabecestat (AZD3293) in a Phase 1 Study of Healthy Japanese Subjects: Pharmacokinetics and Effects on Plasma and Cerebrospinal Fluid Aβ Peptides. J Clin Pharmacol 2017;57:1460–71. doi: 10.1002/jcph.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ghosh AK, Cárdenas EL, Osswald HL. The design, development, and evaluation of BACE1 inhibitors for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Top. Med. Chem, 2017. doi: 10.1007/7355_2016_16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Cummings J, Lee G, Mortsdorf T, Ritter A, Zhong K. Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline: 2017. Alzheimer’s Dement Transl Res Clin Interv 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].O’Neill BT, Beck EM, Butler CR, Nolan CE, Gonzales C, Zhang L, et al. Design and Synthesis of Clinical Candidate PF-06751979: A Potent, Brain Penetrant, β-Site Amyloid Precursor Protein Cleaving Enzyme 1 (BACE1) Inhibitor Lacking Hypopigmentation. J Med Chem 2018. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Slack BE, Ma LK, Seah CC. Constitutive shedding of the amyloid precursor protein ectodomain is up-regulated by tumour necrosis factor-alpha converting enzyme. Biochem J 2001;357:787–94. doi: 10.1042/bj3570787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sambamurti K, Kinsey R, Maloney B, Ge Y-W, Lahiri DK. Gene structure and organization of the human beta-secretase (BACE) promoter. FASEB J 2004;18:1034–6. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1378fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Liu L, Ding L, Rovere M, Wolfe MS, Selkoe DJ. A cellular complex of BACE1 and γ- secretase sequentially generates Aβ from its full-length precursor. J Cell Biol 2019:1–25. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201806205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hemming ML, Elias JE, Gygi SP, Selkoe DJ. Identification of β-secretase (BACE1) substrates using quantitative proteomics. PLoS One 2009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kuhn PH, Koroniak K, Hogl S, Colombo A, Zeitschel U, Willem M, et al. Secretome protein enrichment identifies physiological BACE1 protease substrates in neurons. EMBO J 2012;31:3157–68. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Egan MF, Kost J, Tariot PN, Aisen PS, Cummings JL, Vellas B, et al. Randomized Trial of Verubecestat for Mild-to-Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1691–703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zhu K, Xiang X, Filser S, Marinković P, Dorostkar MM, Crux S, et al. Beta-Site Amyloid Precursor Protein Cleaving Enzyme 1 Inhibition Impairs Synaptic Plasticity via Seizure Protein 6. Biol Psychiatry 2018;83:428–37. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ou-Yang MH, Kurz JE, Nomura T, Popovic J, Rajapaksha TW, Dong H, et al. Axonal organization defects in the hippocampus of adult conditional BACE1 knockout mice. Sci Transl Med 2018;10. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aao5620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hitt B, Riordan SM, Kukreja L, Eimer WA, Rajapaksha TW, Vassar R. β-Site amyloid precursor protein (APP)-cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1)-deficient mice exhibit a close homolog of L1 (CHL1) loss-of-function phenotype involving axon guidance defects. J Biol Chem 2012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.415505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hitt BD, Jaramillo TC, Chetkovich DM, Vassar R. BACE1−/−mice exhibit seizure activity that does not correlate with sodium channel level or axonal localization. Mol Neurodegener 2010. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-5-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ohno M, Sametsky EA, Younkin LH, Oakley H, Younkin SG, Citron M, et al. BACE1 Deficiency Rescues Memory Deficits and Cholinergic Dysfunction in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuron 2004. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00810-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Peters F, Salihoglu H, Rodrigues E, Herzog E, Blume T, Filser S, et al. BACE1 inhibition more effectively suppresses initiation than progression of β-amyloid pathology. Acta Neuropathol 2018;135:695–710. doi: 10.1007/s00401-017-1804-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kim DY, Carey BW, Wang H, Ingano LAM, Binshtok AM, Wertz MH, et al. BACE1 regulates voltage-gated sodium channels and neuronal activity. Nat Cell Biol 2007. doi: 10.1038/ncb1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Willem M, Fleck D, Galante C, Haass C, van Bebber F, Schmid B, et al. Dual Cleavage of Neuregulin 1 Type III by BACE1 and ADAM17 Liberates Its EGF-Like Domain and Allows Paracrine Signaling. J Neurosci 2013. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.3372-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lichtenthaler SF, Dominguez DI, Westmeyer GG, Reiss K, Haass C, Saftig P, et al. The cell adhesion protein P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 is a substrate for the aspartyl protease BACE1. J Biol Chem 2003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303861200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Doody RS, Raman R, Farlow M, Iwatsubo T, Vellas B, Joffe S, et al. A Phase 3 Trial of Semagacestat for Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med 2013. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1210951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Tagami S, Yanagida K, Kodama TS, Takami M, Mizuta N, Oyama H, et al. Semagacestat Is a Pseudo-Inhibitor of γ-Secretase. Cell Rep 2017;21:259–73. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wagner SL, Rynearson KD, Duddy SK, Zhang C, Nguyen PD, Becker A, et al. Pharmacological and Toxicological Properties of the Potent Oral γ -Secretase Modulator BPN-15606. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2017. doi: 10.1124/jpet.117.240861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Pettersson M, Johnson DS, Humphrey JM, Butler TW, Am Ende CW, Fish BA, et al. Design of pyridopyrazine-1,6-dione γ-secretase modulators that align potency, MDR efflux ratio, and metabolic stability. ACS Med Chem Lett 2015;6:596–601. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Pettersson M, Johnson DS, Rankic DA, Kauffman GW, Am Ende CW, Butler TW, et al. Discovery of cyclopropyl chromane-derived pyridopyrazine-1,6-dione γ-secretase modulators with robust central efficacy. Medchemcomm 2017;8:730–43. doi: 10.1039/c6md00406g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Muratore CR, Zhou C, Liao M, Fernandez MA, Taylor WM, Lagomarsino VN, et al. Cell-type Dependent Alzheimer’s Disease Phenotypes: Probing the Biology of Selective Neuronal Vulnerability. Stem Cell Reports 2017;9:1868–84. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Performance of rodent Aβ1–40 and BACE1 immunoassays. (A) Standard curve of rodent Aβ1–40 assay; green dotted line: LLoQ. (B) Standard curve of BACE1 assay; green dotted line: LLoQ. (C) Extracellular Aβ1-x peptides and cellular BACE1 levels were measured by ELISA after 24 h treatment of HEK293-sw cells with AZD3293 (doses from 0.58 fM to 10 μM). All values are normalized to DMSO treatment alone (n=2, means +/− SD; most error bars are too small to see). (D) Cellular BACE1 levels were measured by immunoblot after 24 h treatment of HEK293-sw cells with 2.5 μM AZD3293 or DMSO; α-Tubulin serves as loading control (n=3; means +/− SD; unpaired Student’s t-test: **, P<0.01.

Figure S2. AZD3293 does not alter BACE1 subcellular distribution. (A) Cellular BACE1 levels were measure by ELISA after 24 h treatment of HEK293-sw cells transiently overexpressing BACE1 with AZD3293 (dosages from 150 nM to 10 μM). All values are normalized to DMSO treatment alone (n=3; means +/− SD). (B) Immunoblots of BACE1, EEA1, Rab11a and APP from iodixanol fractions after 24 h treatment of HEK293-sw cells with 2.5 μM AZD3293 or DMSO.