Abstract

Background and Purpose:

In this study, we aim to investigate the association of CT-based markers of cerebral small vessel disease (CSVD) with functional outcome and recovery after intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH).

Methods:

CT scans of patients in the Ethnic and Racial Variations of Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ERICH) study were evaluated for the extent of leukoaraiosis and cerebral atrophy using visual rating scales. Poor functional outcome was defined as a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) of 3 or higher. Multivariable logistic and linear regression models were used to explore the associations of CSVD imaging markers with poor functional outcome at discharge, and, as a measure of recovery, change in mRS from discharge to 90 days post-stroke.

Results:

After excluding in-hospital deaths, data from 2344 patients, 583 (24.9%) with good functional outcome (mRS of 0–2) at discharge and 1761 (75.1%) with poor functional outcome (mRS of 3–5) at discharge, were included. Increasing extent of leukoaraiosis (P for trend = 0.01) and only severe (grade 4) global atrophy (OR 2.02, 95% CI 1.22–3.39, P = 0.007) were independently associated with poor functional outcome at discharge. Mean [SD] mRS change from discharge to 90-day follow up was 0.57 [1.18]. Increasing extent of leukoaraiosis (P for trend = 0.002) and severe global atrophy (β[SE] −0.23[0.115], P = 0.045) were independently associated with less improvement in mRS from discharge to 90 days post-stroke.

Conclusions:

In ICH survivors, the extent of CSVD at the time of ICH is associated with poor functional outcome at hospital discharge and impaired functional recovery from discharge to 90 days post-stroke.

Keywords: cerebral small vessel disease, intracerebral hemorrhage, stroke, cerebrovascular disease/stroke, leukoaraiosis, cerebral atrophy, computerized tomography (CT)

INTRODUCTION

Cerebral small vessel disease (CSVD) is a chronic and cumulative brain disease that affects the smallest cerebral blood vessels, such as deep perforating arterioles, venules and capillaries (1). Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) frequently occurs when blood vessels affected by CSVD rupture as a result of diminished microvascular integrity (2). The pathologic burden of CSVD is thought to be reflected by several neuroimaging markers, such as leukoaraiosis, cerebral microbleeds, and brain atrophy (3). Leukoaraiosis is the most well-studied surrogate marker for CSVD, and its extent typically progresses with age and accumulation of vascular risk factors (4). Because CSVD is a chronic and progressive cerebrovascular disease and affects the brain diffusely, its impact on brain function is likely to exceed that of the acute stroke alone. Hence, the extent to which individuals suffer from CSVD has been related to worse clinical outcomes in both ischemic (5–7) and hemorrhagic (8–10) stroke. In addition, it has been hypothesized that CSVD affects post-stroke neuroplasticity and hampers cerebral network reorganization essential to post-stroke recovery (11). Indeed, several clinical studies in ischemic stroke patients have demonstrated that the extent of leukoaraiosis is associated with poor functional recovery over time (7, 12, 13), but no such studies have been undertaken for ICH.

Given the high burden of disability and functional dependence among ICH survivors, it would be helpful to increase our understanding of the factors at play in determining an individual’s potential for functional recovery in order to inform treatment decisions and rehabilitation efforts. The current study attempts to investigate the influence of two CT-based CSVD markers, leukoaraiosis and brain atrophy, on functional outcome and recovery among a racially balanced cohort of ICH survivors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Study protocol

The present study is a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data of ICH patients enrolled in the Ethnic and Racial Variations in Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ERICH) study, a multi-center study of spontaneous ICH with 41 sites among 19 recruiting centers throughout the United States. The study enrolled spontaneous ICH patients over 18 years old, and of self-reported white, black, or Hispanic race/ethnicity. Patients with non-spontaneous causes of ICH (i.e. due to vascular malformations, aneurysms, tumors, or hemorrhagic conversion of recent ischemic stroke) were excluded. Informed consent was obtained from all patients or their legally authorized representative. All protocols were approved by the institutional review boards of participating centers. A detailed methodology of the ERICH study has been published previously (14).

Study population and collection of clinical variables

Adult patients with spontaneous ICH who were admitted to a medical facility that participated in the ERICH project between 2010 and 2015 were consented and enrolled in the study. Exclusion criteria for the current analysis are: 1) unavailable or unreliable baseline CT scan (e.g., due to poor imaging quality), 2) severe hydrocephalus, large midline shift and/or increased intracranial pressure, 3) primary IVH, 4) multiple intracranial bleeds, 5) no ICH identifiable, 6) in-hospital death, 7) modified Rankin Scale (mRS) at discharge not available.

Clinical characteristics and demographics were prospectively collected through abstraction of the hospital chart, as well as through interviews with patients or their surrogates by trained study investigators. Primary outcome variables (mRS scores) were collected at discharge and at different time points during follow up through telephone interviews with patients or their surrogates.

Imaging acquisition and interpretation

Primary ICH was diagnosed using non-contrast CT scans, performed on admission. Baseline CT’s were used to obtain ICH location and ICH volume using semi-automated computerized volumetric analysis (Alice software, Parexel Corporation, Waltham, MA). Trained investigators blinded to clinical data (SUV, AM, MJ) reviewed all axial scans to determine 1) extent of leukoaraiosis, 2) extent of cerebral atrophy and 3) the Graeb Score, as a measure of IVH severity (15). A visual rating scale was used to grade the extent of periventricular leukoaraiosis, as previously described (16). Anterior and posterior periventricular leukoaraiosis were graded from 0 to 2, summing up to a total score ranging from 0 to 4. Cerebral atrophy was graded using a similar visual rating scale, assessing the extent of atrophy in central and cortical brain regions, again resulting in a total atrophy score ranging from 0 to 4 (8). Leukoaraiosis and cerebral atrophy scores were both rated on the contralateral side of the ICH and were treated as ordinal variables in the analyses. The interrater agreement between the three trained investigators who rated the scans was determined by calculating an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), which was good for all measurements of CSVD markers (anterior leukoaraiosis: 0.78, 95% CI 0.63–0.87; posterior leukoaraiosis: 0.81, 95% CI 0.68–0.89; central atrophy: 0.87, 95% CI 0.79–0.93; cortical atrophy: 0.84, 95% CI 0.72–0.91). The ICC remained high throughout the study. The ICC for the Graeb score was also good (0.95, 95% CI 0.90–0.98).

Statistical analysis

Frequency, mean [SD], and median [IQR] were used to describe categorical and continuous baseline variables. Baseline differences between patients with good (mRS 0–2) or poor (mRS 3–5) functional outcome at hospital discharge were analysed using chi-square tests for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables. A binary logistic regression model, adjusted for predictors of poor functional outcome (gender, age, race/ethnicity, premorbid functional status, GCS on admission, ICH volume and the Graeb Score), was used to determine the association between CSVD markers and functional outcome at discharge. In addition to the binary outcome of good vs. poor discharge mRS, we also modeled discharge mRS as an ordinal response variable. We used mediation analyses to examine whether ICH volume and the IVH Graeb Score mediated the associations between CSVD markers and mRS at discharge.

In order to measure recovery of post-stroke functional status among ICH survivors, the difference between mRS at discharge and mRS at first follow up (90 days post-stroke) was calculated as a recovery parameter (12), such that increasing negative values of the recovery parameter indicate increasing extent of functional decline and increasing positive values indicate increasing extent of functional improvement. A linear-by-linear association test was used to test whether this variable was associated with increasing extent of leukoaraiosis and atrophy. The recovery parameter was then used as an outcome variable in multivariable linear regression models, which was adjusted for potential confounders as well as for mRS at discharge. In all analyses, the absence of leukoaraiosis and cerebral atrophy (score 0) were taken as reference categories. All multivariable models were adjusted for clinically relevant variables shown to be significant (p<0.10) in univariate analysis, and that remained significant predictors after building the multivariable model. In addition, demographic variables (age, gender, race-ethnicity) were incorporated in all models. All analyses were performed using R software (R Studio, version 1.1.383).

RESULTS

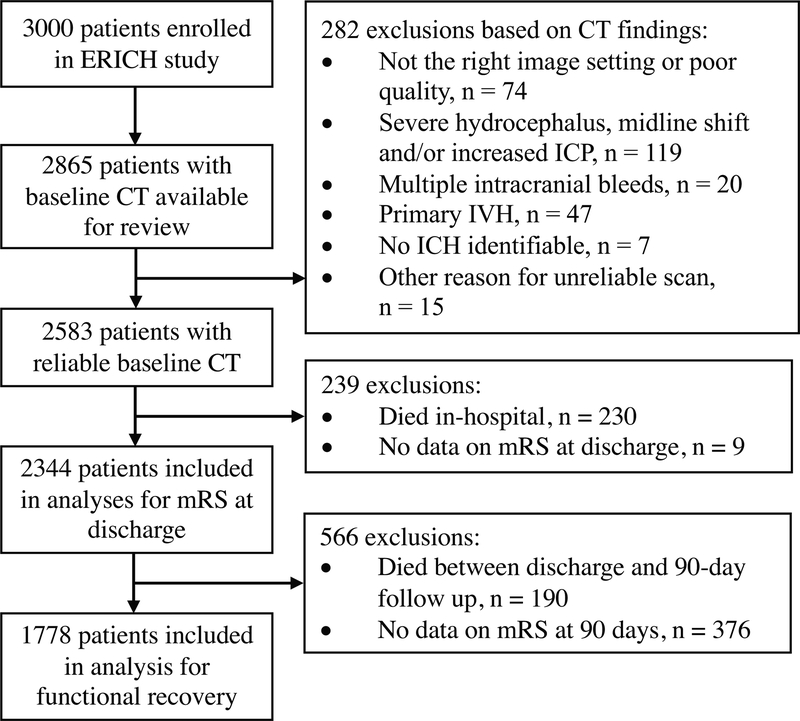

Out of the complete ERICH cohort of 3000 patients, 2865 patients had a CT scan available for review. Of these, 282 patients were excluded based on CT findings and an additional 239 patients were excluded because of in-hospital death (n = 230) of missing data on mRS at discharge (n = 9). A flow chart of the inclusion process is depicted in figure 1. Among the 2344 patients (Table 1) who met our inclusion criteria, 583 (24.9%) patients had good functional outcome at discharge (mRS of 0–2), and 1761 (75.1%) had poor functional outcome (mRS of 3–5). Patients with good functional outcome were younger (p < 0.001), less frequently had a history of hypertension (p = 0.008), diabetes (p = 0.04), or dementia (p < 0.001), and were more likely to have good premorbid functional status (p < 0.001). Furthermore, they had a higher median Glasgow Coma Scale score on admission (P < 0.001), smaller ICH volume (p <0.001), lower rates of IVH presence (p < 0.001), lower IVH Graeb score (p < 0.001), and less frequently had a non-lobar ICH location (p = 0.002). Patients with good functional outcome had a lower burden of CSVD imaging characteristics (all P < 0.001). Baseline differences between patients with good and poor functional outcome at discharge are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1: Flow chart of patient inclusion.

Abbreviations: ERICH, Ethnic and Racial Variations of Intracerebral Hemorrhage; CT, computed tomography; mRS, modified Rankin Scale score; ICP, increased intracranial pressure; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage.

Table 1:

baseline characteristics stratified by functional outcome at hospital discharge.

| Variables | Good functional outcome (discharge mRS 0–2) (n = 583) | Poor functional outcome (discharge mRS 3–5) (n= 1761) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | |||

| Male gender, n (%) | 360 (61.7) | 1036 (58.8) | 0.232 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 58.1 (12.9) | 62.4 (14.6) | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White, n (%) | 562 (31.9) | 171 (29.3) | 0.487 |

| Black, n (%) | 609 (34.6) | 206 (35.3) | |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 590 (33.5) | 206 (35.3) | |

| Clinical variables | |||

| History of hypertension, n (%) | 450 (77.7) | 1437 (82.8) | 0.008 |

| History of stroke, n (%) | 106 (18.2) | 380 (21.6) | 0.089 |

| History of diabetes, n (%) | 143 (24.8) | 512 (29.5) | 0.036 |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 28.3 [24.4, 33.5] | 27.6 [24.0, 32.2] | 0.034 |

| History of smoking, n (%) | 245 (44.1) | 733 (46.2) | 0.420 |

| History of hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 172 (30.8) | 556 (33.9) | 0.185 |

| History of dementia, n (%) | 12 (2.1) | 110 (6.2) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol use, n (%) | 246 (43.2) | 653 (39.7) | 0.149 |

| Premorbid mRs ≤ 2, n (%) | 576 (99.3) | 1592 (90.6) | <0.001 |

| Pre-admission medication | |||

| Warfarin use, n (%) | 31 (5.3) | 158 (9.0) | 0.006 |

| Antiplatelet use, n (%) | 143 (24.5) | 492 (27.9) | 0.121 |

| Admission variables | |||

| GCS in ED, median (IQR) | 15 [15, 15] | 14 [11, 15] | <0.001 |

| SBP, mean (SD) | 185 (69.4) | 187 (50.8) | 0.360 |

| DBP, mean (SD) | 109 (83.5) | 106 (59.3) | 0.385 |

| Length of hospital stay (days), median (IQR) | 5 [3, 7] | 11 [6, 20] | <0.001 |

| ICH characteristics | |||

| Non-lobar ICH location, n (%) | 377 (64.7) | 1258 (71.4) | 0.002 |

| ICH volume, mL, median (IQR) | 4.32 [1.50, 10.1] | 12.19 [4.95, 27.1] | <0.001 |

| IVH presence, n (%) | 121 (20.8) | 746 (42.4) | <0.001 |

| IVH Graeb score | <0.001 | ||

| 0, n (%) | 462 (79.2) | 1007 (57.3) | |

| 1–3, n (%) | 68 (11.7) | 320 (18.2) | |

| 4–6, n (%) | 33 (5.7) | 281 (16.0) | |

| >6, n (%) | 20 (3.4) | 148 (8.4) | |

| CSVD imaging | |||

| Leukoaraiosis | <0.001 | ||

| Grade 0, n (%) | 291 (50.3) | 692 (39.7) | |

| Grade 1, n (%) | 91 (15.7) | 319 (18.3) | |

| Grade 2, n (%) | 109 (18.8) | 292 (16.8) | |

| Grade 3, n (%) | 45 (7.8) | 190 (10.9) | |

| Grade 4, n (%) | 43 (7.4) | 249 (14.3) | |

| Global atrophy | <0.001 | ||

| Grade 0, n (%) | 193 (33.2) | 579 (33.4) | |

| Grade 1, n (%) | 105 (18.1) | 225 (13.0) | |

| Grade 2, n (%) | 191 (32.9) | 472 (27.3) | |

| Grade 3, n (%) | 57 (9.8) | 205 (11.8) | |

| Grade 4, n (%) | 35 (6.0) | 250 (14.4) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; mRS, modified Rankin Scale score; GCS, Glasgow Coma Score; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage.

Functional outcome at discharge

In univariate analyses, increasing grades of leukoaraiosis and cerebral atrophy were associated with poor functional outcome at discharge (both P for trend < 0.001). After adjusting for confounders, leukoaraiosis grade 1 (OR 1.57, 95% CI 1.16–2.14, P = 0.004), 3 (OR 1.57 95% CI 1.06–2.37, P = 0.028) and 4 (OR 1.82, 95% CI 1.21–2.77, P = 0.005) were independently associated with poor functional outcome at discharge, and only severe (grade 4) global atrophy (OR 2.02, 95% CI 1.22–3.39, P = 0.007) was associated with poor functional outcome at discharge. Some (grade 1) atrophy was associated with good functional outcome at discharge in univariate analyses, but became non-significant after adjusting for confounders (table 2). ICH volume and the Graeb score did not mediate associations between CSVD markers and mRS at discharge.

Table 2:

unadjusted and adjusted odds ratio’s for association between CSVD markers and poor functional outcome at discharge.

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | P for trend | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | P for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leukoaraiosis | <0.001 | 0.014 | ||||

| Grade 0 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Grade 1 | 1.47 (1.13–1.94) | 0.005 | 1.57 (1.16–2.14) | 0.004 | ||

| Grade 2 | 1.13 (0.87–1.46) | 0.37 | 1.09 (0.81–1.48) | 0.56 | ||

| Grade 3 | 1.78 (1.26–2.55) | 0.001 | 1.57 (1.06–2.37) | 0.03 | ||

| Grade 4 | 2.44 (1.73–3.50) | <0.001 | 1.82 (1.21–2.77) | 0.005 | ||

| Global atrophy | <0.001 | 0.004 | ||||

| Grade 0 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Grade 1 | 0.71 (0.54–0.95) | 0.02 | 0.82 (0.59–1.14) | 0.25 | ||

| Grade 2 | 0.82 (0.65–1.04) | 0.10 | 0.81 (0.60–1.10) | 0.17 | ||

| Grade 3 | 1.20 (0.86–1.69) | 0.29 | 1.11 (0.73–1.70) | 0.63 | ||

| Grade 4 | 2.38 (1.63–3.56) | <0.001 | 2.02 (1.22–3.39) | 0.007 |

Abbreviations: mRS, modified Rankin Scale score; GCS, Glasgow Coma Score; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage.

Binary logistic regression for analyses of mRs at discharge, adjusted for gender, age, race/ethnicity, premorbid functional status, GCS on admission, ICH volume and the Graeb Score. Models examining leukoaraiosis were adjusted for global atrophy and the other way around.

Functional recovery from discharge to 3 months post-stroke

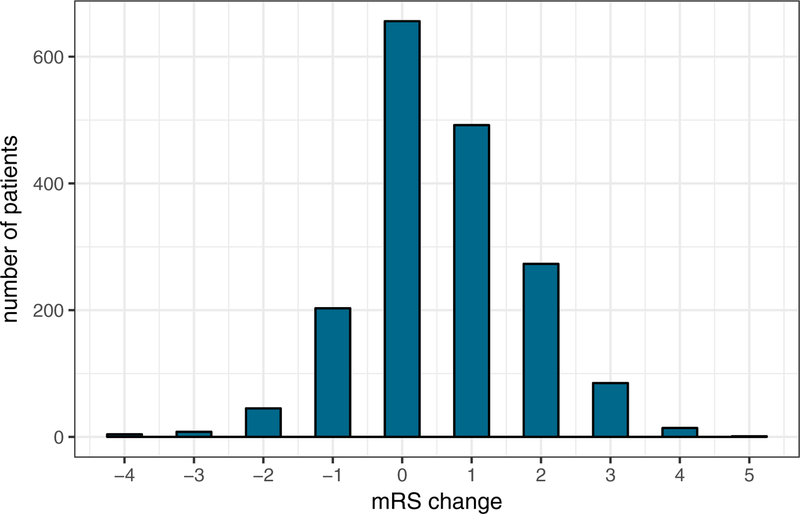

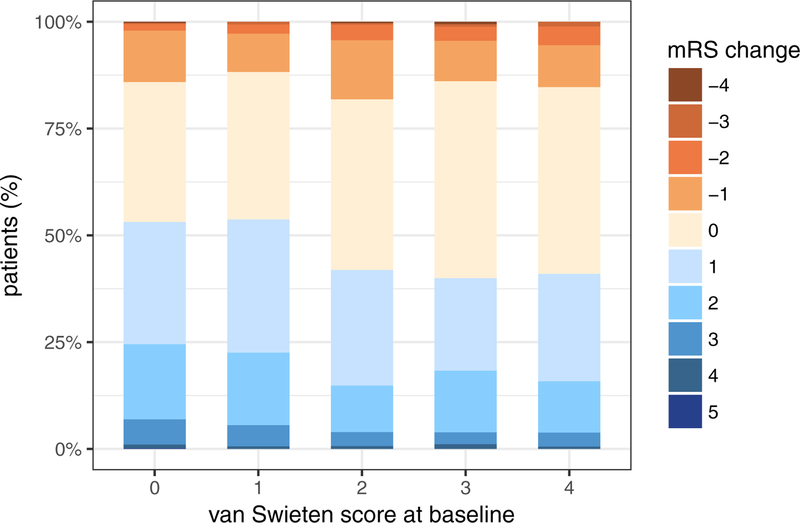

A total of 1778 patients had available data on mRS at discharge and at 90 days post-stroke (figure 1). Of these, 866 patients (48.7%) experienced improvement (recovery parameter ≥ 1), 653 patients (36.7%) experienced no improvement or decline (recovery parameter = 0), and 259 patients (14.6%) declined (recovery parameter ≤ −1). As the van Swieten score increased, the percentage of patients with mRS improvement decreased (53.1%, 53.7%, 41.9%, 40.0%, 41.0%, unadjusted P for trend < 0.001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Graphical summary of results related to functional recovery between discharge and 90 days post-stroke.

Top: distribution of mRS change from discharge to 90 days post-stroke; bottom: frequency distribution of the recovery parameter in patients with different degrees of leukoaraiosis at baseline (P for trend < 0.001).

Using the recovery parameter (see Methods section) as the outcome variable in univariate linear models, van Swieten scores 2 (P < 0.001), 3 (P = 0.009), and 4 (P = 0.002) were significantly associated with less recovery of function, and they remained significant after adjusting for confounders (β[SE] −0.20[0.075], P = 0.007; β[SE] −0.25[0.094], P = 0.009; β[SE] −0.22[0.098], P = 0.024 for van Swieten score 2, 3, and 4, respectively; P for trend 0.002). Only severe global atrophy was associated with less recovery after adjusting for confounders (β[SE] −0.23[0.115], P = 0.045) (Table 3).

Table 3:

Association between CSVD markers and difference between mRs at discharge and mRs at 90 days post-stroke (recovery parameter) and percentage change in the recovery parameter by increasing degrees of leukoaraiosis and atrophy (n = 1778).

| Unadjusted β (SE) | P value (P for trend) | Change in recovery parameter (%) | Adjusted β (SE) | P value (P for trend) | Change in recovery parameter (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leukoaraiosis | (<0.001) | (0.002) | ||||

| Grade 0 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| Grade 1 | −0.02 (0.08) | 0.846 | −1.98% | −0.01 (0.07) | 0.942 | −0.99% |

| Grade 2 | −0.31 (0.08) | 0.001 | −26.7% | −0.20 (0.08) | 0.007 | −18.1% |

| Grade 3 | −0.25 (0.10) | 0.009 | −22.1% | −0.25 (0.11) | 0.009 | −22.1% |

| Grade 4 | −0.30 (0.10) | 0.002 | −25.9% | −0.22 (0.10) | 0.024 | −19.7% |

| Global atrophy | (0.005) | (0.076) | ||||

| Grade 0 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| Grade 1 | −0.17 (0.09) | 0.053 | −15.6% | −0.03 (0.08) | 0.734 | −2.96% |

| Grade 2 | −0.16 (0.07) | 0.020 | −14.8% | −0.01 (0.07) | 0.870 | −0.99% |

| Grade 3 | −0.18 (0.10) | 0.071 | −16.5% | −0.05 (0.11) | 0.615 | −4.88% |

| Grade 4 | −0.32 (0.10) | 0.002 | −27.4% | −0.23 (0.11) | 0.046 | −20.5% |

Abbreviations: mRS, modified Rankin Scale score; GCS, Glasgow Coma Score; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage.

Multivariable linear models were adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, stroke history, GCS on admission, mRS at discharge, premorbid functional status, and ICH volume. Models examining leukoaraiosis were adjusted for atrophy and the other way around.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we attempted to assess the contribution of pre-existing CSVD to functional recovery between hospital discharge and 90 days after an ICH has occurred. This approach is based on the assumption that the effects of long-standing CSVD on functional outcome post-ICH can, albeit imperfectly, be distinguished from the effects of the acute ICH itself, by focusing on recovery of function, most of which is expected to occur within the first 90 days after stroke (17). Although a number of previous studies have investigated the effects of leukoaraiosis and atrophy on functional outcome after ICH (8, 9, 10), the novelty of the current study lies in our examination of change in mRS between discharge and 90 days post-stroke as a recovery parameter.

Hence, we were able to demonstrate that ICH survivors with moderate-to-severe leukoaraiosis were likely to experience less improvement of functional outcome over time. These findings are in line with the results from similar studies for ischemic stroke, which demonstrated that leukoaraiosis is associated with impaired post-stroke recovery by investigating the change in National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) (7, 13) or mRS (7, 12). Our study therefore adds to the growing body of literature suggesting that the extent of CSVD affects recovery in stroke patients (13, 18). Efficient post-stroke recovery entails re-organization of brain networks (19), which might be compromised in brains with advanced leukoaraiosis (11). In addition, the severity of leukoaraiosis is associated with post-stroke cognitive decline (20) and depression (21) and these secondary phenomena are likely to synergistically contribute to unfavorable recovery.

Although we did not find a true dose-dependent effect of increasing severity of leukoaraiosis on the extent of change in mRS (i.e., the coefficients for leukoaraiosis grades 2, 3 and 4 were similar in our regression models), this could be explained by the fact that once leukoaraiosis becomes visible on CT, it is already well-advanced. By that point, the microvascular architecture of vessels affected by CSVD is diffusely compromised, even in areas where leukoaraiosis is not (yet) visible on CT (22). Hence, a ceiling effect might be reached once leukoaraiosis becomes visible on CT as a grade 2 or higher, beyond which the added effect of additional leukoaraiosis has less of an impact on post-stroke recovery.

Importantly, in our analyses, leukoaraiosis remained independently associated with less functional recovery after adjusting for age. This finding indicates that the burden of leukoaraiosis may represent a certain degree of brain fragility, and its addition to chronological age determines an individual’s capacity of post-stroke recovery more accurately than chronological age by itself (13). While the extent of leukoaraiosis on CT alone should not be used to identify patients at high risk for impaired recovery, it will increase the accuracy of such predictions when used in combination with variables that are known to influence recovery, such as age, premorbid functional status and ICH-related variables. Together, this information can help guide therapeutic decisions, rehabilitative approaches and counselling.

Several studies have investigated the relationship between CSVD and functional outcome at 90-days among ICH survivors (8, 23, 24), but the effects of pre-existing CSVD on (sub)acute functional outcome post-ICH have not been investigated extensively. It might be tempting to hypothesize that (sub)acute outcome is mostly determined by the severity of the acute ICH itself, i.e., hematoma volume and intraventricular extension of the hematoma, as these markers represent short-term injury mechanisms and are established predictors of poor outcome and mortality (25, 26). In this study, we demonstrate that even in the subacute phase following ICH, at hospital discharge, pre-existing CSVD affects functional outcome. These associations were independent of ICH features, thus disentangling the contributions of chronic (CSVD) and acute (ICH volume and severity of IVH) brain damage on functional outcome.

Unlike leukoaraiosis, cerebral atrophy is not traditionally regarded as a core feature of CSVD on neuroimaging, but it has been suggested that brain atrophy occurs secondary to the white matter damage found in patients with CSVD and it can be used as a surrogate marker for CSVD progression (27, 28). Whereas leukoaraiosis has repeatedly been shown to predict worse outcome post-stroke, previous studies have reported conflicting results on the association between atrophy and outcome following ICH (9, 29). Mild atrophy might be protective by allowing more space in the brain and limit the damage of a space-occupying lesion by preventing increased intracranial pressure and herniation (30, 31). However, severe global atrophy (grade 4) was associated with poor functional outcome at discharge in our study, indicating that atrophy may be protective to some level, but at a certain degree, severe neurodegeneration offsets the protective effect of mild atrophy. Similarly, in our analysis of recovery of function, only severe cerebral atrophy was independently associated with less recovery after adjusting for confounders and leukoaraiosis. Nevertheless, our results indicate that overall, white matter tract disruption seems more important than global cerebral neurodegeneration in determining individual recovery potential.

The present study has several limitations and strengths. Strengths include our large sample size and multicenter, prospective study design as well as our racially balanced study population. Compared with previous similar studies, this feature of our study design improves generalizability of the study results. In addition, our method of taking the difference in mRS as a recovery estimate may be more informative than examining functional status at a given time point post-stroke, since it is calculated for each individual patient and it provides information on the change in functional status over time.

The major limitation of this study is the fact that our recovery parameter, which we use as a surrogate measure for neurologic recovery, is a crude measure of functional recovery and it does not truly represent neurologic recovery. Advanced imaging techniques and differentiated outcome measures may be more suitable to investigate how CSVD affects brain plasticity and hinders cerebral network reorganization that is essential to recovery. Moreover, we cannot exclude the possibility of misclassification of CSVD phenotypes given the CT-based visual rating scales for leukoaraiosis and atrophy, which are less accurate than MRI-based measures. Nonetheless, our interrater agreement for both leukoaraiosis and atrophy grading was good. Moreover, we feel that, given the wide availability of CT scanners and the fact that head CT scans are routinely made in the setting of acute stroke (32), this offers the potential for a quick assessment of leukoaraiosis and atrophy in those patients. Furthermore, since we only measured functional recovery at two time points, we cannot exclude the possibility that recovery has continued to occur beyond 90 days after ICH. Hence, it remains uncertain whether the extent of recovery or the rate of recovery is limited in patients with a high burden of CSVD, which depends on whether these patients will eventually recover to the same degree as those with a low burden of CSVD. Lastly, selection bias could have occurred due to exclusion of patients presenting with severe hydrocephalus or a large midline shift on baseline CT-scan, or requiring immediate intervention. The results of this study might not be generalizable to patients with a severe ICH.

SUMMARY

We demonstrated that moderate-to-severe leukoaraiosis reduces the extent of recovery in ICH survivors in the period between hospital discharge and 90-days post-stroke. The question of whether CSVD impairs recovery from ICH or whether the ICH aggravates compensated neurologic and functional deficits caused by CSVD remains to be elucidated. Future studies are needed to investigate how chronic CSVD interacts with post-ICH injury and recovery mechanisms and results in a reduced recovery potential in ICH survivors in the first 90 days post-stroke.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by the NIH National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (K23NS086873, U01NS069763, R01NS059727 and R01NS103924). CJM, DW and JR report NIH funding. MLJ is supported by the National University of Singapore, NIH and NICO. CDA is supported by R01NS103924, K23NS086873, AHA 18SFRN34250007. SUV is supported by the Jo Kolk Study Fund and KF Hein Fund. SM is supported by the AHA/ASA fellowship (18POST34080063).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

CDA reports consulting for ApoPharma, Inc. JR reports consulting for Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer and New Beta Innovation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pantoni L Cerebral small vessel disease: from pathogenesis and clinical characteristics to therapeutic challenges. The Lancet Neurology. 2010;9:689–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young VG, Halliday GM, Kril JJ. Neuropathologic correlates of white matter hyperintensities. Neurology. 2008;71:804–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gouw AA, Seewann A, van der Flier WM, Barkhof F, Rozemuller AM, Scheltens P, et al. Heterogeneity of small vessel disease: a systematic review of MRI and histopathology correlations. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2011;82:126–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Debette S, Markus HS. The clinical importance of white matter hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2010;341:c3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oksala NK, Oksala A, Pohjasvaara T, Vataja R, Kaste M, Karhunen PJ, et al. Age related white matter changes predict stroke death in long term follow-up. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2009;80:762–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inzitari D, Pracucci G, Poggesi A, Carlucci G, Barkhof F, Chabriat H, et al. Changes in white matter as determinant of global functional decline in older independent outpatients: three year follow-up of LADIS (leukoaraiosis and disability) study cohort. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2009;339:b2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryu WS, Woo SH, Schellingerhout D, Jang MU, Park KJ, Hong KS, et al. Stroke outcomes are worse with larger leukoaraiosis volumes. Brain. 2017;140:158–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato S, Delcourt C, Heeley E, Arima H, Zhang S, Al-Shahi Salman R, et al. Significance of Cerebral Small-Vessel Disease in Acute Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke. 2016;47:701–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwon SM, Choi KS, Yi HJ, Ko Y, Kim YS, Bak KH, et al. Impact of brain atrophy on 90-day functional outcome after moderate-volume basal ganglia hemorrhage. Sci Rep. 2018;8:4819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caprio FZ, Maas MB, Rosenberg NF, Kosteva AR, Bernstein RA, Alberts MJ, et al. Leukoaraiosis on magnetic resonance imaging correlates with worse outcomes after spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2013;44:642–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forster A, Griebe M, Ottomeyer C, Rossmanith C, Gass A, Kern R, et al. Cerebral network disruption as a possible mechanism for impaired recovery after acute pontine stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;31:499–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Held V, Szabo K, Bazner H, Hennerici MG. Chronic small vessel disease affects clinical outcome in patients with acute striatocapsular stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;33:86–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onteddu SR, Goddeau RP Jr., Minaeian A, Henninger N. Clinical impact of leukoaraiosis burden and chronological age on neurological deficit recovery and 90-day outcome after minor ischemic stroke. J Neurol Sci. 2015;359:418–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woo D, Rosand J, Kidwell C, McCauley JL, Osborne J, Brown MW, et al. The Ethnic/Racial Variations of Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ERICH) study protocol. Stroke. 2013;44:e120–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graeb DA, Robertson WD, Lapointe JS, Nugent RA, Harrison PB. Computed tomographic diagnosis of intraventricular hemorrhage. Etiology and prognosis. Radiology. 1982;143:91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Swieten JC, Hijdra A, Koudstaal PJ, van Gijn J. Grading white matter lesions on CT and MRI: a simple scale. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1990;53:1080–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jang SH, Park JW, Choi BY, Kim SH, Chang CH, Jung YJ, et al. Difference of recovery course of motor weakness according to state of corticospinal tract in putaminal hemorrhage. Neurosci Lett. 2017;653:163–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ay H, Arsava EM, Rosand J, Furie KL, Singhal AB, Schaefer PW, et al. Severity of leukoaraiosis and susceptibility to infarct growth in acute stroke. Stroke. 2008;39:1409–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Meer MP, Otte WM, van der Marel K, Nijboer CH, Kavelaars A, van der Sprenkel JW, et al. Extent of bilateral neuronal network reorganization and functional recovery in relation to stroke severity. J Neurosci. 2012;32:4495–4507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molad J, Kliper E, Korczyn AD, Ben Assayag E, Ben Bashat D, Shenhar-Tsarfaty S, et al. Only White Matter Hyperintensities Predicts Post-Stroke Cognitive Performances Among Cerebral Small Vessel Disease Markers: Results from the TABASCO Study. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2017;56:1293–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He JR, Zhang Y, Lu WJ, Liang HB, Tu XQ, Ma FY, et al. Age-Related Frontal Periventricular White Matter Hyperintensities and miR-92a-3p Are Associated with Early-Onset Post-Stroke Depression. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. 2017;9:328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Sullivan M, Summers PE, Jones DK, Jarosz JM, Williams SC, Markus HS. Normal-appearing white matter in ischemic leukoaraiosis: a diffusion tensor MRI study. Neurology. 2001;57:2307–2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sykora M, Herweh C, Steiner T. The Association Between Leukoaraiosis and Poor Outcome in Intracerebral Hemorrhage Is Not Mediated by Hematoma Growth. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;26(6):1328–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Won YS, Chung PW, Kim YB, Moon HS, Suh BC, Lee YT, et al. Leukoaraiosis predicts poor outcome after spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage. Eur Neurol. 2010;64:253–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young WB, Lee KP, Pessin MS, Kwan ES, Rand WM, Caplan LR. Prognostic significance of ventricular blood in supratentorial hemorrhage: a volumetric study. Neurology. 1990;40:616–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Broderick JP, Brott TG, Duldner JE, Tomsick T, Huster G. Volume of intracerebral hemorrhage. A powerful and easy-to-use predictor of 30-day mortality. Stroke. 1993;24:987–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nitkunan A, Lanfranconi S, Charlton RA, Barrick TR, Markus HS. Brain atrophy and cerebral small vessel disease: a prospective follow-up study. Stroke. 2011;42:133–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wardlaw JM, Smith C and Dichans M. Mechanisms of sporadic cerebral small vessel disease: inshights from neuroimaging. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12:483–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herweh C, Prager E, Sykora M, Bendszus M. Cerebral atrophy is an independent risk factor for unfavorable outcome after spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2013;44:968–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beck C, Kruetzelmann A, Forkert ND, Juettler E, Singer OC, Kohrmann M, et al. A simple brain atrophy measure improves the prediction of malignant middle cerebral artery infarction by acute DWI lesion volume. Journal of neurology. 2014;261:1097–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee SH, Oh CW, Han JH, Kim CY, Kwon OK, Son YJ, et al. The effect of brain atrophy on outcome after a large cerebral infarction. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2010;81:1316–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ginde AA, Foianini A, Renner DM, Valley M, Camargo CA Jr. Availability and quality of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging equipment in U.S. emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:780–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.