Abstract

Background:

Patients with low back pain (LBP) are often treated with non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAID) and skeletal muscle relaxants (SMR). We compared functional outcomes and pain among acute LBP patients randomized to a one week course of ibuprofen + placebo versus ibuprofen + one of three SMRs: baclofen, metaxalone, or tizanidine.

Methods:

This was a randomized, double-blind, parallel group, 4-arm study conducted in two urban emergency departments (ED). Patients with non-radicular LBP for <=two weeks were eligible if they had a score >5 on the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), a 24-item inventory of functional impairment due to LBP. All participants received 21 tablets of ibuprofen 600mg, to be taken TID, as needed. Additionally, they were randomized to baclofen 10mg, metaxalone 400mg, tizanidine 2mg, or placebo. Participants were instructed to take one or two of these capsules, TID, as needed. All participants received a 10 minute educational session. The primary outcome was improvement on the RMDQ between ED discharge and 1week later. Secondary outcomes included pain intensity one week after ED discharge (severe, moderate, mild, or none).

Results:

320 patients were randomized. One week later, the mean RMDQ score of patients randomized to placebo improved by 11.1(95%CI:9.0,13.3), baclofen improved by 10.6 (95%CI:8.6,12.7), metaxalone improved by 10.1 (95%CI:8.0,12.3) and tizanidine improved by 11.2 (95%CI:9.2, 3.2). At one week follow-up, 30% (95%CI: 21, 41%) of placebo patients reported moderate/severe LBP versus 33% (95%CI: 24, 44%) of baclofen, 37% (95%CI: 27, 48%) of metaxalone and 33% (95%CI: 23, 44%) of tizanidine patients.

Conclusion:

Adding baclofen, metaxalone, or tizanidine to ibuprofen does not appear to improve functioning or pain any more than placebo + ibuprofen one week after an ED visit for acute LBP.

Background

Low back pain (LBP) is exceedingly common, with a global point prevalence of 18%.(1) Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are considered first line pharmacological treatment.(2, 3) NSAIDs alone often provide inadequate analgesia for patients with symptoms of sufficient severity to warrant an emergency department (ED) visit, as 1/3 of these patients who receive NSAIDs alone report moderate or severe LBP one week later.(4)

Importance

Skeletal muscle relaxants (SMR) are commonly used to treat LBP both in the ED(5) and in ambulatory practice,(6) often in combination with NSAIDs. Evidence supporting efficacy of SMRs in this role is generally of lower quality.(2, 7) Previous clinical trials similarly indicate that use of naproxen, in combination with cyclobenzaprine,(8) orphenadrine,(9) methocarbamol,(9) or diazepam(10) does not improve LBP outcomes among ED patients any more than naproxen alone. In this study, we sought to determine whether there is any benefit from combining three other commonly used SMRs--baclofen, metaxalone, or tizanidine--with an NSAID.

Goal of this investigation

In this randomized, 4-arm clinical trial conducted among a population of ED patients with acute, functionally-impairing, non-radicular LBP, we wished to determine whether a daily regimen of ibuprofen plus baclofen, metaxalone, or tizanidine would provide greater relief of LBP than ibuprofen plus placebo one week after an ED visit, as measured by improvement on the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ). The RMDQ is a 24-item inventory of functional impairment due to LBP, commonly used in LBP clinical research. (11)

Methods

Study design and setting

This was a randomized, double-blind, parallel group, comparative effectiveness study, in which we enrolled patients during an ED visit for musculoskeletal LBP, and then followed them by telephone two and seven days later. Every patient received standard-of-care therapy, consisting of ibuprofen and a LBP education session. Patients were randomized to placebo, baclofen, metaxalone, or tizanidine. This study was registered online at http://clinicaltrials.gov, identifier: NCT03068897. The Albert Einstein College of Medicine Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved the protocol and provided continuing oversight. All participants provided written informed consent. This trial is reported in accordance with CONSORT guidelines.

This study was performed in the two academic EDs of Montefiore Medical Center (Bronx, NY) with a combined annual census of 180,000 adult visits. Salaried, full-time, bilingual (English and Spanish) technician-level research associates, staffed both EDs 24 hours per day, seven days per week during the study period.

Selection of participants

We enrolled adults aged 18-64 who presented to one of our EDs primarily for management of acute, non-radicular, non-traumatic, musculoskeletal LBP, defined as pain originating between the lower border of the scapulae and the upper gluteal folds. Participants were required to have had LBP for no longer than 2 weeks. If they had prior episodes of back pain, they could not have had it as frequently as once per month. Participation required functional impairment due to LBP, which we defined as a baseline score of > 5 on the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (http://www.rmdq.org).

Patients were excluded from participation if they were unavailable for follow-up, if they were pregnant or breast-feeding, using medication for a chronic pain syndrome, which we defined as use of any analgesic medication on a daily or near-daily basis, or for allergy to, intolerance of, or contraindication to any of the investigational medications.

Interventions

Patients were randomized in a 1:1:1:1 ratio to one of these four medication regimens:

-

1)

The control arm: Ibuprofen 600mg + placebo, orally, both every 8 hours as needed

-

2)

The baclofen arm: Ibuprofen 600mg+ baclofen 10- 20mg, orally, both every 8 hours as needed

-

3)

The metaxalone arm: Ibuprofen 600mg+ metaxalone 400- 800mg, orally, both every 8 hours as needed

-

4)

The tizanidine arm: Ibuprofen 600mg+ tizanidine 2- 4mg, orally, both every 8 hours as needed

In an effort to maximize effectiveness while minimizing side effects, patients were instructed to take one ibuprofen plus one or two muscle relaxant capsules every 8 hours as needed. If one capsule of the muscle relaxant afforded sufficient relief, there was no need for the patient to take the second. However, if the participant did not experience sufficient relief within 60 minutes of taking one investigational medication capsule, they were instructed to take the second. All study participants were given a seven day supply of ibuprofen and the muscle relaxant or placebo.

The pharmacist performed randomization in blocks of 8 based on a sequence generated at http://randomization.com. Ibuprofen was not masked. Metaxalone, tizanidine, baclofen, and placebo were masked by placing tablets into identical capsules, which were then packed with scant amounts of lactose and sealed. Research personnel presented participants with two bottles of medication capsules. The bottle containing the ibuprofen was labeled in a typical manner. The second bottle, containing the muscle relaxant or placebo was labeled as investigational medication. Thus the investigators, clinicians, participants and research associates/ outcome assessors were blinded to treatment received. Patients were instructed to take the medications only as needed for LBP.

Research personnel provided each participant with a 10-minute educational intervention. This was based on NIAMS’s Handout on Health: Back Pain information webpage (available at https://www.niams.nih.gov/health-topics/back-pain). Research personnel reviewed each section of the information sheet with the study participant and elicited questions.

Measurements

We used the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), a validated 24-item LBP functional scale recommended for use in LBP research to measure LBP functional impairment (12) (http://www.rmdq.org). To measure pain, we used an ordinal pain scale on which participants described their pain as severe, moderate, mild, or none. To determine how often participants experienced LBP after enrollment in the study, we asked them to describe their pain frequency using the words “always”, “usually”, “sometimes”, “rarely”, or “not-at-all”. At baseline, we recorded participants’ age, sex, work status, and RMDQ score, the duration of the current episode of LBP, frequency of previous episodes of LBP, and presence of depression, utilizing a two-item screening instrument from the Patient Health Questionnaire depression module.(13)

Outcomes

The primary outcome for this study was improvement in RMDQ between the baseline ED visit and the one week follow-up (RMDQ baseline - RMDQ 1 week ). Secondary outcomes included severity and frequency of pain at 48 hours and one week, requirement of medication for LBP at each of these time points, and an assessment of how long it took patients to return to work or usual activities. We also assessed side effects by asking, “Did you have any side effects from the medications you were taking?” and recording their dichotomous responses. We also determined, by asking participants, how often they visited any healthcare provider during the week after ED discharge.

Analysis.

We report baseline characteristics, including age, sex, work status, baseline RMDQ, duration and history of LBP, and results of depression screen as mean (SD), median (IQR) or percent, as appropriate. For the primary outcome, improvement in RMDQ between baseline and one week later, we performed an intention-to-treat analysis among all patients for whom primary outcome data were available. We report these results as means with 95%CI. We considered between-group differences statistically significant if the 95%CI of the difference did not cross zero. Secondary outcomes are reported as rates.

We based the sample size calculation on a minimum clinically important difference of five units on the RMDQ, a within group standard deviation of 8.9 estimated from an earlier study (8), a standard alpha of 0.05 and a beta of 0.20. Using these criteria we determined the need for 50 subjects in each arm. To account for protocol violations, patients lost-to-follow-up, and non-adherence to the investigational medication regimen,(8, 9) we enrolled 80 patients in each arm.

Results

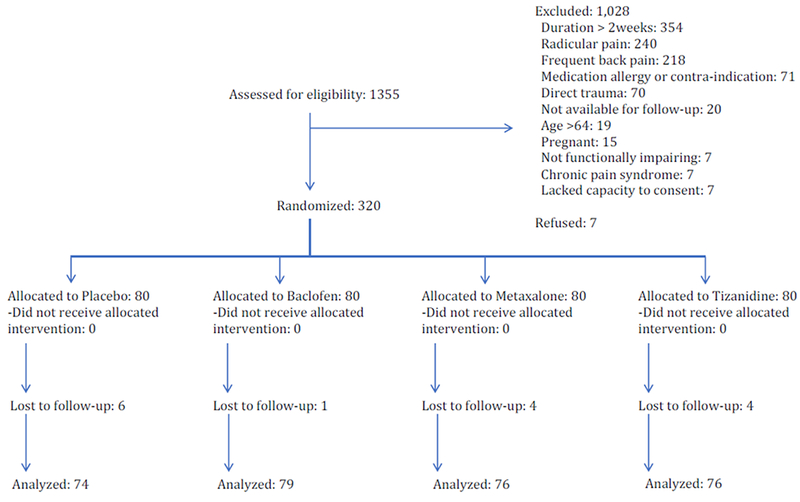

Enrollment commenced in May, 2017 and concluded in July, 2018. During these 15 months, 1,355 patients were screened for participation and 320 were enrolled (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics are reported in Table 1. In general, patients reported a substantial amount of baseline functional impairment—the median RMDQ score among all participants at enrollment was 19 (IQR: 15, 23).

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Variable | Ibuprofen + placebo (n=80) | Ibuprofen + baclofen (n=80) | Ibuprofen + metaxalone (n= 80) | Ibuprofen + tizanidine (n=80) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age in years (SD) | 39 (11) | 39 (12) | 37 (10) | 40 (11) |

| Sex | ||||

| Men | 44 (55%) | 57 (71%) | 44 (55%) | 42 (53%) |

| Women | 36 (45%) | 23 (29%) | 36 (45%) | 38 (48%) |

| Work status | ||||

| Unemployed | 6 (8%) | 10 (13%) | 5 (6%) | 6 (8%) |

| Student | 1 (1%) | 2 (3%) | 2 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| <30 hours/ week | 8 (10%) | 5 (6%) | 13 (16%) | 6 (8%) |

| ≥30 hours/ week | 65 (81%) | 63 (79%) | 60 (75%) | 68 (85%) |

| Median RMDQ at time of ED visit (IQR) | 20 (15, 23) | 20 (16, 23) | 18 (15, 22) | 19 (15, 22) |

| Actual RMDQ score at time of ED visit | ||||

| <10 | 5 (6%) | 5 (6%) | 5 (6%) | 1 (1%) |

| 10-19 | 35 (44%) | 30 (38%) | 43 (54%) | 45 (56%) |

| 20-24 | 40 (50%) | 45 (56%) | 32 (40%) | 34 (43%) |

| Median duration of low back pain prior to presentation to ED in hours (IQR) | 72 (24, 96) | 72 (24, 114) | 48 (24, 83) | 48 (24, 72) |

| Previous episodes of low back pain | ||||

| Never before | 15 (19%) | 15 (19%) | 22 (28%) | 21 (26%) |

| Few times before | 52 (65%) | 52 (65%) | 47 (59%) | 45 (56%) |

| At least once/ year | 13 (16%) | 13 (16%) | 11 (14%) | 14 (18%) |

| Depression screen positive1 | 3 (4%) | 2 (3%) | 4 (5%) | 3 (4%) |

Values are n (%) unless otherwise stated.

RMDQ: Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire. This is a 24 item instrument measuring low back pain related functional impairment. On this instrument, 0 represents no low back pain related functional impairment and 24 represents maximum functional impairment.

1. Patients were asked two screening questions from the Patient Health Questionnaire: a) Before your back pain began, how often were you bothered by little pleasure or interest in doing things? And b) Before your back pain began, how often were you bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless? Patients who responded to either question “More than half the days” or “Nearly every day” were considered to screen positive for depression.

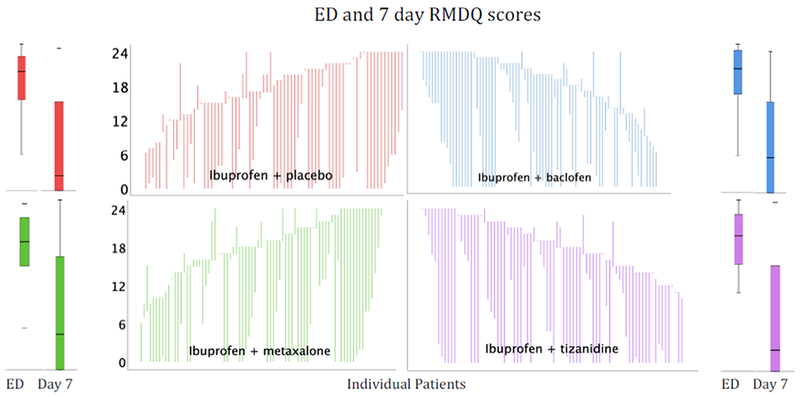

Overall, one week after ED discharge, participants reported a mean improvement in RMDQ score of 10.8 (95%CI: 9.8, 11.8). There were no clinically important nor statistically significant differences among the study arms (Table 2 and Figure 2). Any functional impairment (RMDQ>0) was reported by 189/ 305 (62%, 95%CI: 56, 67%) of participants, while 141/ 305 (46%, 95%CI: 41, 52%) reported substantial functional impairment (RMDQ>5). Secondary outcomes one week (Table 2) and 48 hours (Table 3) after ED discharge did not reveal clinically important differences among the study arms. Overall, 166/ 312 (53%, 95%CI: 48, 59%) of participants reported moderate or severe pain at 48 hours and 101/ 304 (33%, 95%CI: 28, 39%) reported moderate or severe pain at one week. Use of medication for LBP was reported by 285/ 312 (91%, 95%CI: 88, 94%) of participants at 48 hours and 192/ 304 (63%, 95%CI: 58, 68%) of participants at one week.

Table 2.

One-week outcomes

| Outcome variable | Ibuprofen + placebo (n=80) | Ibuprofen + baclofen (n=80) | Ibuprofen + metaxalone (n=80) | Ibuprofen+ Tizanidine (n=80) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean improvement in RMDQ1 between baseline and one week (95%CI) | 11.1 (9.0, 13.3) | 10.6 (8.6, 12.7)2 | 10.1 (8.0, 12.3)3 | 11.2 (9.2, 13.2)4 |

| missing | 6 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Median absolute RMDQ1 score (IQR) | 3 (0, 15) | 6 (0, 16) | 5 (0, 16) | 3 (0, 15) |

| missing | 6 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Worst low back pain during previous 24 hours | ||||

| Mild/ none | 51 (70%) | 53 (67%) | 48 (63%) | 51 (67%) |

| Moderate/ Severe | 22 (30%) | 26 (33%) | 28 (37%) | 25 (33%) |

| missing | 7 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Frequency of low back pain during previous 24 hours | ||||

| Never/ rarely | 39 (53%) | 38 (48%) | 33 (43%) | 45 (59%) |

| Sometimes | 22 (30%) | 20 (25%) | 19 (25%) | 13 (17%) |

| Frequently/ always | 12 (16%) | 21 (27%) | 24 (32%) | 18 (24%) |

| missing | 7 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Use of medication for low back pain during the 24 hours prior to one week follow-up | ||||

| No medications | 27 (37%) | 30 (38%) | 27 (36%) | 28 (37%) |

| Used medications | 46 (63%) | 49 (62%) | 49 (64%) | 48 (63%) |

| missing | 7 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Median days until usual activities (IQR) | 2 (2, 7) | 4 (2, >7)5 | 3 (2, 7) | 3 (2, 7) |

| missing | 7 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

RMDQ: Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire. This is a 24 item instrument measuring low back pain related functional impairment. On this instrument, 0 represents no low back pain related functional impairment and 24 represents maximum functional impairment.

95%CI for the 0.5 difference between the ibuprofen+ placebo arm and the ibuprofen+ baclofen arm: −2.4, 3.4

95%CI for the 1.0 difference between the ibuprofen+ placebo arm and the ibuprofen+ metaxalone arm: −2.0, 4.0

95%CI for the 0.1 difference between the ibuprofen+ placebo arm and the ibuprofen+ tizanidine arm : −2.8, 3.0

>25% of patients had not yet returned to usual activities prior to the 7 day follow-up

Figure 2.

This figure depicts baseline and 7 day RMDQ scores. The Y axis indicates the 0-24 RMDQ scores—higher scores indicate worse functional outcomes. Median and interquartile range of ED (baseline) and 7 day (follow-up) RMDQ data are depicted in the box and whisker plots. In these graphs, the median is represented by a horizontal line, the inter-quartile range by the box, and the complete range of data by the whiskers. The high-low graphs depict the baseline and 7 day RMDQ score for every individual. These data are sorted by baseline RMDQ score so upward spikes represent patients who worsened.

Table 3.

48 hour outcomes

| Outcome variable | Ibuprofen + placebo (n=80) | Ibuprofen + baclofen (n=80) | Ibuprofen + metaxalone (n=80) | Ibuprofen+ tizanidine (n=80) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worst low back pain during previous 24 hours | ||||

| Mild/ none | 29 (38%) | 41 (52%)1 | 35 (45%)2 | 41 (53%)3 |

| Moderate/ Severe | 48 (62%) | 38 (48%) | 43 (55%) | 37 (47%) |

| missing | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Frequency of low back pain during previous 24 hours | ||||

| Never/ rarely | 16 (21%) | 22 (28%) | 19 (24%) | 19 (24%) |

| Sometimes | 32 (42%) | 27 (34%) | 31 (40%) | 35 (45%) |

| Frequently/ always | 29 (38%) | 30 (38%) | 28 (36%) | 24 (31%) |

| missing | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Use of medication for low back pain during the 24 hours prior to 48 hour follow-up | ||||

| No medications | 5 (6%) | 7 (9%) | 7 (9%) | 8 (10%) |

| Used medications | 72 (94%) | 72 (91%) | 71 (91%) | 70 (90%) |

| missing | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Resumed work or usual activities | ||||

| Yes | 36 (47%) | 40 (51%) | 32 (41%) | 36 (46%) |

| No | 41 (53%) | 39 (49%) | 46 (59%) | 42 (54%) |

| missing | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

95%CI for the 14% difference between the ibuprofen+ placebo arm and the ibuprofen+ baclofen arm: −1, 30%

95%CI for the 7% difference between the ibuprofen+ placebo arm and the ibuprofen+ metaxalone arm: −8, 23%

95%CI for the 15% difference between the ibuprofen+ placebo arm and the ibuprofen+ tizanidine arm: −1, 30%

Use of additional healthcare resources during the week after ED discharge was uncommon and comparable among the study arms (Table 4). Overall, 33/ 304 (11%, 95%CI: 8, 15%) visited any healthcare provider, of whom the majority were primary care providers.

Table 4.

Use of Additional Healthcare Resources

| Outcome variable | Ibuprofen + placebo (n=80) | Ibuprofen + baclofen (n=80) | Ibuprofen + metaxalone (n=80) | Ibuprofen+ tizanidine (n=80) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visited any healthcare provider after ED visit | 12 (16%) | 7 (9%)3 | 5 (7%)4 | 9 (12%)5 |

| Subsequent ED visit | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Primary care | 8 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| MD specialist1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Physical therapy | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Complementary therapy2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| missing | 7 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

Spine surgeon, pain management

Massage

95%CI for the 8% rounded difference between the ibuprofen+ placebo arm and the ibuprofen+ baclofen arm: −3, 18%

95%CI for the 10% rounded difference between the ibuprofen+ placebo arm and the ibuprofen+ metaxalone arm: 0, 20%

95%CI for the 5% rounded difference between the ibuprofen+ placebo arm and the ibuprofen+ tizanidine arm: −7, 16%

Side effects were reported by 24/283 (8%, 95%CI: 6, 12%) participants (Table 5). These did not differ among the study arms. None were serious.

Table 5.

Side effects

| Side event | Ibuprofen + placebo (n=80) | Ibuprofen + baclofen (n=80) | Ibuprofen + metaxalone (n=80) | Ibuprofen+ tizanidine (n=80) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any side event | ||||

| No | 62 (93%) | 66 (90%) | 64 (91%) | 67 (92%) |

| Yes | 5 (7%) | 7 (10%) | 6 (9%) | 6 (8%) |

| missing | 13 | 7 | 10 | 7 |

Side effects reported by patients in the ibuprofen + placebo group: Drowsiness (2), headache, nausea, diarrhea, urinary complaint

Side effects reported by patients in the ibuprofen + baclofen group: Dizziness (2), drowsiness (4), nausea (3), headache, diplopia, muscle spasm (2)

Side effects reported by patients in the ibuprofen + metaxalone group: Constipation, drowsiness (2), dry mouth, abdominal pain, dizziness, vaginal bleeding

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to determine the impact of missing data on the primary outcome. In this analysis, we assumed no improvement in the RMDQ in the placebo arm and a median improvement (11 RMDQ points) in each of the active arms. This had no meaningful impact on the primary outcome—the between group difference in improvement in RMDQ was <1.0 among all groups.

Data on frequency of use of the study medications are presented in the Appendix.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. First, the doses of medication we used in this study were not based on prior dose-finding studies, which we could not find in the published literature. We hoped to overcome this limitation by using a patient-centered self-titration mechanism, in which patients who required more medication could take a second pill. Still, it is possible that we under-dosed some or all of the investigational medications. Second, this study was conducted in two urban EDs. It is unclear whether or not these results can be generalized to other clinical arenas. It is quite possible that LBP outcomes are associated with access to care.

Discussion

In this ED-based, randomized, double-blind, comparative effectiveness study, combining each of three commonly-used muscle relaxants with ibuprofen did not improve one week functional outcomes more than ibuprofen + placebo among ED patients with acute, functionally-impairing LBP. While most of these patients with non-radicular LBP enjoyed good pain and functional outcomes one week after the ED visit, about 1/3 reported moderate or severe pain, ¼ reported frequent LBP, and nearly 1/2 reported substantial functional impairment. Among this ED cohort, only 11% accessed the healthcare system during the week after the ED visit.

When considered as a class, monotherapy with SMRs has generally outperformed placebo with regard to short-term pain relief among patients with acute LBP.(14) However, while baclofen, metaxalone, and tizanidine, are frequently used for back pain, there is not a robust literature supporting efficacy for patients with acute LBP. We identified only one such study of baclofen: In a randomized, placebo- controlled study of baclofen for acute LBP, 200 patients were randomized to monotherapy with baclofen 80mg/ day or to placebo.(15) Although outcomes at four and ten days favored baclofen, these were of marginal clinical importance. We identified two identically-designed, randomized, placebo- controlled studies of metaxalone 3200mg/ day among patients with acute or acute exacerbations of chronic LBP. These demonstrated substantial benefit, with effects sizes of nearly 50% with regard to symptomatic improvement.(16) Each of these studies enrolled 100 patients. Randomized studies of tizanidine versus placebo or combinations of tizanidine + NSAIDs versus NSAIDs alone did not consistently demonstrate that use of tizanidine resulted in tangible benefits for patients with acute LBP (Appendix table).

The results of this study are similar to other studies of ED patients with acute, non-radicular LBP: adding SMRs (8, 9), diazepam (10), or opioids (8) to NSAIDs does not improve short or long-term functional or pain outcomes. Despite standard of care treatment, a large subset of these patients continue to suffer moderate or severe pain and functional impairment one week after the ED visit.(4) It is becoming increasingly apparent that currently available medication is an inadequate remedy for patients with acute, functionally impairing LBP. It is still uncertain whether or not non-medical therapies such as spinal manipulation, physical therapy, massage, or stretching help acute LBP patients treated concurrently with NSAIDs.(17, 18)

In conclusion, when compared to ibuprofen plus placebo, adding baclofen, metaxalone, or tizanidine to ibuprofen does not improve functioning or pain one week after an ED visit for acute LBP.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This publication was supported in part by the Harold and Muriel Block Institute for Clinical and Translational Research at Einstein and Montefiore grant support (UL1TR001073)

Appendix Data

Frequency of use of ibuprofen

| Frequency of use | Placebo | Baclofen | Metaxalone | Tizanidine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 3 (4%) |

| Only once | 4 (5%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (3%) | 6 (8%) |

| Sometimes | 15 (21%) | 8 (11%) | 10 (14%) | 7 (10%) |

| Daily | 16 (22%) | 15 (21%) | 16 (22%) | 15 (21%) |

| >=Twice/ daily | 38 (52%) | 48 (66%) | 45 (61%) | 42 (58%) |

| Missing | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 |

Frequency of use of investigational medication (placebo, baclofen, metaxalone or tizanidine)

| Frequency of use | Placebo | Baclofen | Metaxalone | Tizanidine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 4 (5%) | 6 (8%) |

| Only once | 6 (8%) | 3 (4%) | 4 (5%) | 6 (8%) |

| Sometimes | 12 (16%) | 8 (11%) | 10 (14%) | 13 (17%) |

| Daily | 19 (26%) | 18 (24%) | 24 (33%) | 17 (23%) |

| >=Twice/ daily | 36 (49%) | 45 (60%) | 31 (42%) | 33 (44%) |

| Missing | 6 | 5 | 7 | 5 |

Appendix table.

Efficacy of tizanidine for back pain

| Author, year | Indication | N (primary outcome data) | Dose of Tizanidine | Comparator | Primary outcome | Secondary outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ketenci, 2005(19) | LBP <72 hours + spasm | 58 | 6mg in the evening+ placebo in AM | Placebo BID | Less pain at rest at day 3 and 7 in tizanidine group | Less rescue medication in tizanidine group. “Good/excellent efficacy” comparable in placebo and tizanidine |

| Berry, 1988(20) | Recent onset LBP | 96 | 4mg TID | Placebo | No differences between groups in pain scores at day 3 or day 7 | Some secondary outcomes favored tizanidine |

| Berry, 1988(21) | Recent onset LBP | 98 | 4mg TID + ibuprofen 400mg TID | Placebo + ibuprofen 400mg TID | No clinically significant differences between groups in pain scores at day 3 or 7 | Fewer patients who received the combination reported moderate or severe pain at 3 days |

| Pareek, 2009(22) | LBP ≤30 days | 185 | 2mg BID + aceclofenac 100mg BID | Placebo + aceclofenac 100mg BID | Combination marginally more clinically effective at day 3, substantially more clinically effective at day 7, as measured by improvement on 0-10 pain scale. | Substantially more patients report “good or excellent response”to combination (NNT=2) |

| Lepisto, 1979(23) | Acute muscle spasms of back | 28 | 2mg TID | Placebo | No between group difference in pain | Physician rated tizanidine better |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, March L, Brooks P, Blyth F, et al. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(6):2028–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, Skelly A, Weimer M, Fu R, et al. Systemic Pharmacologic Therapies for Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(7):480–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA, Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of P. Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(7):514–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman BW, Conway J, Campbell C, Bijur PE, John Gallagher E. Pain One Week After an Emergency Department Visit for Acute Low Back Pain Is Associated With Poor Three- month Outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2018;25(10):1138–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedman BW, Chilstrom M, Bijur PE, Gallagher EJ. Diagnostic testing and treatment of low back pain in United States emergency departments: a national perspective. Spine. 2010;35(24):E1406–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo X, Pietrobon R, Curtis LH, Hey LA. Prescription of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and muscle relaxants for back pain in the United States. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29(23):E531–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roelofs PD, Deyo RA, Koes BW, Scholten RJ, van Tulder MW Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs for low back pain: an updated Cochrane review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(16):1766–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman BW, Dym AA, Davitt M, Holden L, Solorzano C, Esses D, et al. Naproxen With Cyclobenzaprine, Oxycodone/Acetaminophen, or Placebo for Treating Acute Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1572–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman BW, Cisewski D, Irizarry E, Davitt M, Solorzano C, Nassery A, et al. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Naproxen With or Without Orphenadrine or Methocarbamol for Acute Low Back Pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman BW, Irizarry E, C. S, Khankel N, Zapata J, Zias E, et al. Diazepam is no better than placebo when added to naproxen for acute low back pain. Annals of emergency medicine. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roland M, Fairbank J. The Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire and the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire. Spine. 2000;25(24):3115–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deyo RA, Battie M, Beurskens AJ, Bombardier C, Croft P, Koes B, et al. Outcome measures for low back pain research. A proposal for standardized use. Spine. 1998;23(18):2003–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two- item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Tulder MW, Touray T, Furlan AD, Solway S, Bouter LM, Cochrane Back Review G. Muscle relaxants for nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the cochrane collaboration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28(17):1978–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dapas F, Hartman SF, Martinez L, Northrup BE, Nussdorf RT, Silberman HM, et al. Baclofen for the treatment of acute low-back syndrome. A double-blind comparison with placebo. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1985;10(4):345–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fathie K A Second Look at a Skeletal Muscle Relaxant: A Double-Blind Study of Metaxalone. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 1964;6:677–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, Skelly A, Hashimoto R, Weimer M, et al. Nonpharmacologic Therapies for Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(7):493–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rothberg S, Friedman BW. Complementary therapies in addition to medication for patients with nonchronic, nonradicular low back pain: a systematic review. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(1):55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ketenci A, Ozcan E, Karamursel S. Assessment of efficacy and psychomotor performances of thiocolchicoside and tizanidine in patients with acute low back pain. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59(7):764–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berry H, Hutchinson DR. A multicentre placebo-controlled study in general practice to evaluate the efficacy and safety of tizanidine in acute low-back pain. J Int Med Res. 1988;16(2):75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berry H, Hutchinson DR. Tizanidine and ibuprofen in acute low-back pain: results of a double-blind multicentre study in general practice. The Journal of international medical research. 1988;16(2):83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pareek A, Chandurkar N, Chandanwale AS, Ambade R, Gupta A, Bartakke G. Aceclofenac- tizanidine in the treatment of acute low back pain: a double-blind, double-dummy, randomized, multicentric, comparative study against aceclofenac alone. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2009;18(12):1836–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lepisto P A comparative trial of DS 103-282 and placebo in the treatment of acute skeletal muscle spasms due to disorders of the back. Current Therapeutic Research. 1979;26(4):454–9. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.