Abstract

The Great Amazon Reef (GARS) is an extensive mesophotic reef ecosystem between Brazil and the Caribbean. Despite being considered as one of the most important mesophotic reef ecosystems of the South Atlantic, recent criticism on the existence of a living reef in the Amazon River mouth was raised by some scientists and politicians. The region is coveted for large-scale projects for oil and gas exploration. Here, we add to the increasing knowledge about the GARS by exploring evolutionary aspects of the reef using primary and secondary information on radiocarbon dating from carbonate samples. The results obtained demonstrate that the reef is alive and growing, with living organisms inhabiting the GARS in its totality. Additional studies on net reef growth, habitat diversity, and associated biodiversity are urgently needed to help reconcile economic activities and biodiversity conservation.

Subject terms: Stratigraphy, Sedimentology, Marine biology

Introduction

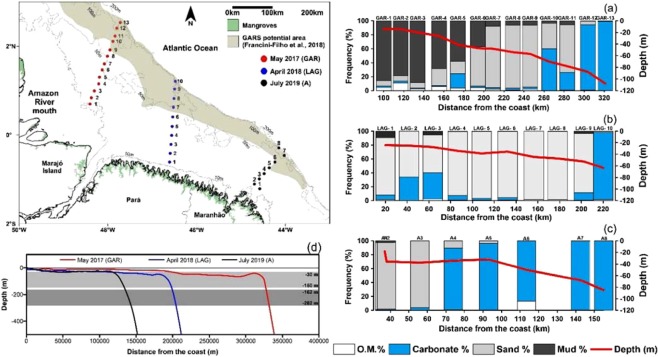

Although described 40 years ago by1, the Great Amazon Reef (GARS; northern limit of the Brazilian Province) was only recently recognized as an extensive and diverse reef system in the Amazon continental margin, between Brazil and the Caribbean2–5 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Location of the study area, sectors as defined by Moura et al. (2016), and samples analysed in this study. Source of information for samples: Red cross8, Brown triangle3, Black cross37, Yellow dot (this paper).

The GARS is currently considered as one of the most important mesophotic reef ecosystems of the South Atlantic6. It is composed by a mosaic of shallow patch reefs (50–70 m), mesophotic reefs (30–220 m depth), large living rhodolith beds and more complex living hard bottoms (formed mainly by fused calcareous algae) inhabited by a diverse reef biota, including threatened and commercially important species4. Biogenic reefs (patch reefs, platforms and walls) are mostly composed by crustose calcareous algae, with sparse areas covered by scleractinian corals, particularly Madracis decactis4.

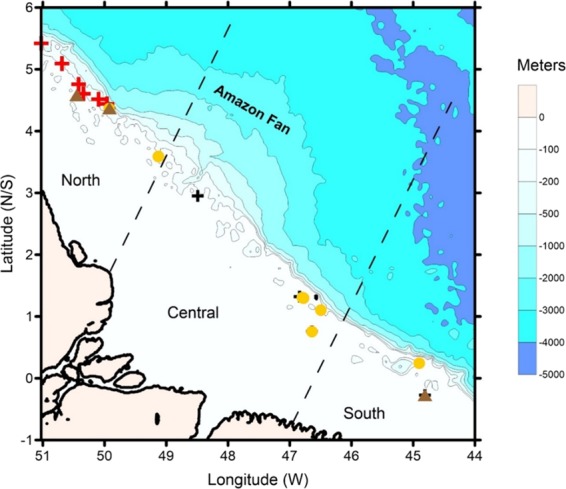

Despite its plausible socio-ecological importance, the GARS is highly threatened by the expansion of oil and gas exploration projects in the region. In 2018, the existence of the GARS itself started to be questioned by a few scientists7, as well as by industrial sectors and politicians in favour of oil exploration in the region. The main argument is that there are no large biogenic structures built by living corals and/or other reef-building organisms (e.g., calcareous algae), particularly in the northern portion of the GARS, due to larger influx of sediments from the Amazon River across the continental shelf7, which may have led to a relict reef environment, developed during MIS28. Because of such scepticism, a more detailed description of the GARS was provided by4. These authors showed that the GARS is composed of large and extensive biogenic structures build mainly by living calcareous algae (“coralline algal frameworks,” cf9.) (Fig. 2). More recently10, have demonstrated that there is enough light for photosynthetic organisms to thrive in the area of the GARS.

Figure 2.

(A) a complex reef emerging >4 m in height from the bottom formed by living crustose coralline algae and covered with black corals (elongated white structures). (B) Fractures evidencing carbonatic platforms sparsely covered by rhodoliths and sponges and (C) a patch reef covered with the scleractinian coral Madracis decactis (black arrows). Photos taken by R.B.F.F.

The older dating ages used in7 were published by8 and would correspond to the oolites present in the Northern Sector. However11, argued that these oolite samples were displaced from their original place of formation and highlighted one should be very careful when using these dated oolite samples to infer reef age and accretion7. also stated that the Amazon shelf is mostly covered by muds, a condition which would impede the development of carbonate reefs. Indeed, the inner and middle parts of the Amazon shelf are mostly covered by muds12,13, while the outer shelf is covered by coarser sediments and consolidated substrates, as reported by13 and confirmed by the images reported by4.

The predominance of terrigenous sediments, particularly in the inner and mid-shelf portions of the Amazonian shelf, is not a limiting factor for the existence of biogenic reefs, as there is enough light available for photosynthetic organisms across most of the Amazon shelf, even in the north sector10. Another example of turbid-water reefs include the most extensive coral reefs in the SW Atlantic (Abrolhos Bank, central Brazilian coast), which are surrounded mostly by siliciclastic sediments14,15. Brazilian biogenic reef ecosystems are recognised for being well adapted to high turbidity levels due to terrestrial input (via large rivers discharge) and sediment resuspension14,16.

The GARS is located mostly at the middle, and outer shelf of the Foz do Amazonas and Pará-Maranhão marginal sedimentary basins within a depth range of 70 to 220 m4. The area is substantially influenced by the Amazon River, with a mean annual water discharge on the order of 6.0 1012 m3 and annual suspended-sediment load on the order of 1.2 109 tons17, affecting all physical and chemical aspects of the water column (e.g., salinity, light availability, pH, dissolved nutrients) over the shelf including the GARS. Most of the sediment travels north in a plume driven by the northwest-flowing North Brazil and Guiana Currents, which are forced by local wind patterns18.

The Amazon River plume has a very dynamic character and even though it is generally driven to the northwest, seasonal variations of winds and currents on the shelf lead to some southeastward expansion of the plume, as a result of displacements caused by the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), with substantial rainfall and NE Trade Winds between January and June. In contrast, between July and December rainfall is reduced, and SE Trade Winds prevail19. There are four distinct zones based on light regimes reaching the bottom, three of them with constant light regimes (dark coastal zone under the permanent influence of the plume; dim-light zone in the deeper northern shelf and high-light zone in the shallower southern shelf) and one zone with seasonal changes in benthic light regimes (northern mid-to-outer shelf)10.

Waves reach the region mainly from the east and northeast, because of the NE-SE trade winds, with dominant offshore wave heights between 1 and 3 m. The most energetic waves approach the region between December and March, with strong NE Trade Winds offshore20. Besides the oceanic currents and waves, tidal water level variation and tidal currents are also substantial in the area, with tidal amplification on the shelf resulting in macrotidal conditions at the coast21.

In this paper, we aim to summarise published and unpublished radiocarbon dating from carbonate samples from the GARS in order to: 1) evaluate its modern or relict nature and 2) contribute to the understanding of its evolution by proposing a theoretical model from the end of Marine Isotope Stage 2 until modern ages.

Results

Table 1 summarizes the radiocarbon ages presented in this work.

Table 1.

Summary of the radiocarbon data used in this work.

| Sample | Sector | Latitude (N/S) | Longitude (W) | Depth (m) | Lab Number | Material | Conventional Age (BP) | Calibrated Age (Median Probability) BP | 95% range (cal BP) | Fraction Modern Carbon | D14C (‰) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V-18-18-Top | North | 5.420 | −51.027 | 150 | Oolite | 20090 ± 600 | 23710 | 22405–25205 | Not available | Not available | Milliman & Barretto (1975) | |

| V-18-18-Bottom | North | 5.420 | −51.027 | 150 | Oolite | 38000 | 41864 | 40020–43350 | Not available | Not available | Milliman & Barretto (1975) | |

| X-236 | North | 5.091 | −50.690 | 133 | Oolite | 17010 ± 400 | 20037 | 19025–20995 | Not available | Not available | Milliman & Barretto (1975) | |

| G209 | North | 4.757 | −50.419 | 109 | Oolite | 14470 ± 400 | 17045 | 15950–18060 | Not available | Not available | Milliman & Barretto (1975) | |

| G210 | North | 4.604 | −50.343 | 104 | Oolite | 14310 ± 250 | 16845 | 16150–17545 | Not available | Not available | Milliman & Barretto (1975) | |

| 1921 | North | 4.513 | −50.097 | 146 | Oolite | 17170 ± 1240 | 20276 | 17350–23265 | Not available | Not available | Milliman & Barretto (1975) | |

| G211 | North | 4.440 | −49.960 | 191 | Oolite | 21250 ± 400 | 25063 | 24145–25885 | Not available | Not available | Milliman & Barretto (1975) | |

| N01 | North | 4.370 | −49.920 | 120 | Carbonate | 12620 ± 30 | 14105 | 13975–14225 | Not available | Not available | Moura et al.3 | |

| C01-Surface | North | 4.580 | −50.450 | 80 | Carbonate | 4480 ± 25 | 4680 | 4570–4790 | Not available | Not available | Moura et al.3 | |

| C02-Core | North | 4.580 | −50.450 | 80 | Carbonate | 6950 ± 30 | 7115 | 7005–7210 | Not available | Not available | Moura et al.3 | |

| S01 | South | −0.270 | −44.810 | 23 | Carbonate | Modern | Modern | Not available | Not available | Moura et al.3 | ||

| N01 | North | 4.370 | −49.920 | 120 | Oolite | 12100 | Not available | Not available | Not available | Vale et al.37 | ||

| N01 | North | 4.370 | −49.920 | 120 | Bivalve shell | 13480 | Not available | Not available | Not available | Vale et al.37 | ||

| N12 | North | 4.370 | −49.920 | 120 | Coral polyp | 14680 | Not available | Not available | Not available | Vale et al.37 | ||

| R14 | North | 2.950 | −48.490 | 95 | Bryozoan | 2460 | Not available | Not available | Not available | Vale et al.37 | ||

| R14 | North | 2.950 | −48.490 | 95 | CCA | 2050 | Not available | Not available | Not available | Vale et al.37 | ||

| R17 | Central | 1.320 | −46.840 | 55 | Bryozoan | 680 | Not available | Not available | Not available | Vale et al.37 | ||

| R17 | Central | 1.320 | −46.840 | 55 | Hydrocoral | 560 | Not available | Not available | Not available | Vale et al.37 | ||

| R07 | Central | 0.760 | −46.640 | 50 | CCA | 1300 | Not available | Not available | Not available | Vale et al.37 | ||

| R07 | Central | 0.760 | −46.640 | 50 | CCA | 510 | Not available | Not available | Not available | Vale et al.37 | ||

| R07 | Central | 0.760 | −46.640 | 50 | CCA | 1040 | Not available | Not available | Not available | Vale et al.37 | ||

| R07 | Central | 0.760 | −46.640 | 50 | CCA | 580 | Not available | Not available | Not available | Vale et al.37 | ||

| N18 | South | −0.270 | −44.810 | 23 | Hydrocoral | Modern | Modern | Not available | Not available | Vale et al.37 | ||

| NB3/1 FT59 | North | 3.590 | −49.127 | 95 | Beta-516488 | Sponge | Modern | Modern | 1.0342 ± 0.0039 | 34.18 ± 3.86 | This work | |

| NB3/1 FT52 | North | 3.590 | −49.127 | 95 | Beta-516487 | Rhodolith | Modern | Modern | 1.0188 ± 0.0038 | 18.85 ± 3.81 | This work | |

| NB2/1 FT55 | North | 4.368 | −49.926 | 120 | Beta-524179 | CCA | Modern | Modern | 1.0113 ± 0.0038 | 11.27 ± 3.78 | This work | |

| NB3/1 FT52 | North | 3.590 | −49.127 | 95 | Beta-524180 | Rhodolith | 50 ± 30 | Modern | 0.9938 ± 0.0037 | −6.21 ± 3.71 | This work | |

| NB6/1 UFRJ14 | Central | 1.300 | −46.779 | 55 | Beta-524181 | Rhodolith | Modern | Modern | 1.0406 ± 0.0039 | 40.64 ± 3.89 | This work | |

| NB6/1 UFRJ13/FT31 | Central | 1.300 | −46.779 | 55 | Beta-524182 | Rhodolith | Modern | Modern | 1.0290 ± 0.0038 | 29.05 ± 3.84 | This work | |

| NB6/1 FT14 | South | 1.305 | −46.797 | 60 | Beta-516486 | Sponge | 940 ± 30 | 540 | 490–610 | 0.8896 ± 0.0033 | −110.43 ± 3.32 | This work |

| NB7/1 FT29 | South | 1.103 | −46.495 | 100 | Beta-516490 | Rhodolith | 170 ± 30 | Modern | 0.9791 ± 0.0037 | −20.94 ± 3.66 | This work | |

| NB8/1 FT50 | South | 0.756 | −46.642 | 40 | Beta-524183 | Rhodolith | Modern | Modern | 1.0227 ± 0.0038 | 22.66 ± 3.82 | This work | |

| NB10/2 FT08 | South | 0.246 | −44.901 | 23 | Beta-524184 | Rhodolith | 270 ± 30 | Modern | 0.9669 ± 0.0036 | −33.05 ± 3.61 | This work |

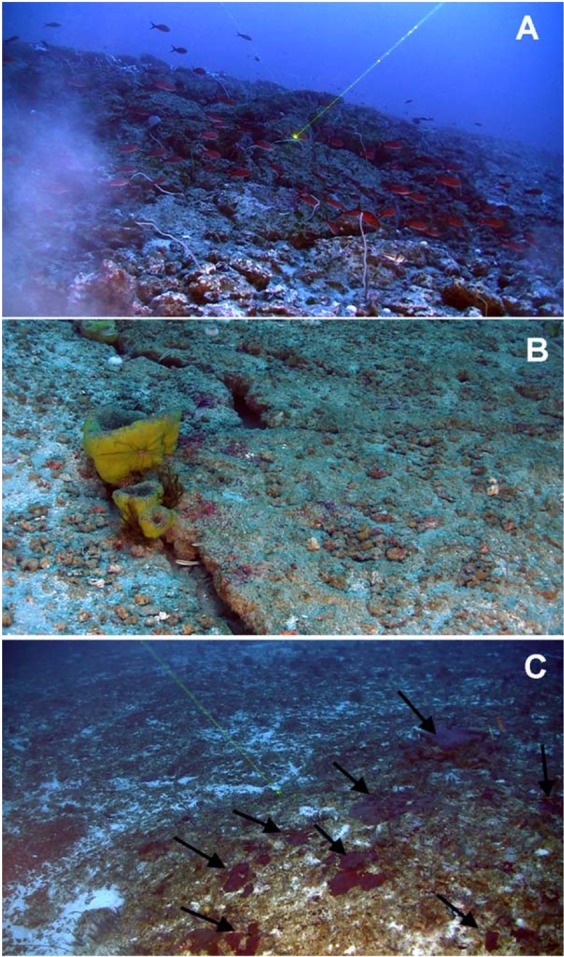

Radiocarbon ages can be divided into three main groups (Fig. 3):

-

i.

Contains samples exclusively from the northern sector, at water depths between 104 and 150 meters, encompassing samples with ages from the MIS2, as defined by22, with three exceptions, the first corresponding to an age of ca. 41,800 cal BP, and two others, with ages corresponding to the Younger Dryas, as delimited by23. The oldest ages correspond to the dating of oolites, published by8;

-

ii.

Encompasses samples from the North and Central sectors, and presents a period from ca. 7,100 cal BP (Mid-Holocene), to historical ages (non-modern radiocarbon ages). Water depth from these samples varies from 50 to 95 meters, and;

-

iii.

Corresponds to samples with modern radiocarbon ages, as defined by24 and contains samples from the three sectors. The water depth range of these samples varies from 23 to 100 meters; the shallowest samples are located in the Southern sector.

Figure 3.

Bathymetric distribution of the samples dated, associated with a general sea-level curve25. The possible age of the onset of the GARS, based in our revision, is shown with a black arrow. The grey area shows the time gap, referred to on the Discussion.

Discussion

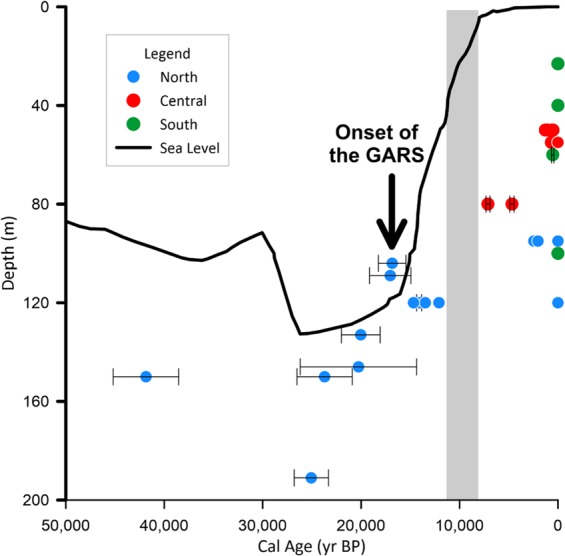

Cross-shelf profiles of sediment samples obtained between 2017 and 2019 show that the morphology and the sedimentary characteristics from the central and southern sectors of the GARS support the ages compiled here (Fig. 4). Considering the mesophotic depth range of 30 to 150 m, local depths and the sea level variation25, the area of the potential occurrence of mesophotic reefs during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) was rather narrow and restricted to the continental slope. As sea level rose quickly from LGM towards Mid-Holocene, there was a period of restriction of areas within the mesophotic depth range, before the drowning of the shelf.

Figure 4.

Bottom sedimentary characteristics and morphology of three profiles at the Amazon shelf stressing the carbonatic-siliciclastic sedimentation contrast (a–c) and the mesophotic depth range in contrast to the bottom morphology and present (light grey) and LGM (deep grey) sea level (d).

The bathymetric profile from the central sector shows a substantially wider shelf, within a deeper outer shelf (Fig. 4), favouring reef development during Mid-Holocene. On the other hand, the distance from the Amazon River mouth and the shallowness of the shelf at the south favoured relatively shallow reef development there, with shallow reefs expanding their occurrence towards the central sector. A recent study focusing on fisheries in the Amazon River mouth suggests that reef structures may occur in areas that are much shallower than previously anticipated26.

A recent review of the formation of oolites27 confirms the intertidal and shallow subtidal formation of most of the marine oozes but emphasizes the complexity of the biogeochemical processes involved in their formation. When comparing the position of the oolites dated by8 with the sea-level change curve (Fig. 3), we agree with the observations by11 about the lack of reliability of oolite materials as indicators of ancient shores on the Amazon margin.

In this sense, we state that the MIS2 and MIS 3 ages, presented by8 and used by7 as for the onset of the GARS cannot be used for an evolutionary model for the reef system. Assuming that the oldest ages must be analysed with care, the first reliable dating to be considered for the GARS correspond to the samples, located on the Northern sector, that lie between 14,680 and 12,100 cal BP, at a water depth of 120 meters, in synchronicity with the Heinrich H128.

Considering these ages and the sea-level curve shown in Fig. 225, we propose a model of the evolution of GARS throughout the Late Quaternary, comprising three major phases:

-

i.

We could assume that a first phase of the development of the reef occurred at water depths between 50 and 100 meters, approximately, right in the central range of mesophotic reef ecosystems29. This phase would occur at the end of the Pleistocene, between ca 14,700 and 12,100 cal BP;

-

ii.

After the first phase, there is a gap in radiocarbon ages, corresponding to the interval between 12,100 and 7,100 cal BP, followed by the beginning of the occurrence of reef material in the Central sector. This gap roughly corresponds in time to the acceleration of the sea-level rise after the Younger Dryas (Melt Water Pulse 1B)30,31. Further, the time of the gap also follows the period when the Amazon River sediment load was developing a prominent plume, whereas during the previous period the sea-level was close to the shelf break and most of the Amazon sediment was transported into the deep sea by way of the Amazon Submarine Canyon and smaller channels32. Within the strong plume development, light penetration in the water column would be strongly attenuated, impairing the reef development. This process attenuated as the sea-level rise went on and the Amazon River plume moved landward and northwestwards.

-

iii.

Finally, modern ages are found in samples from the three sectors, indicating the spread of the reef complex, from Northwest to Southeast. Also, reef constituents are found in areas as shallow as 20 meters (in the southern sector), and as deep as 220 meters4.

Our radiocarbon dating study is coherent with previous studies performed on rhodoliths from the Pacific and the Atlantic oceans where metagenomics demonstrated that the majority of living material corresponds to microbes (bacteria) capable of growing in a variety of extreme environmental conditions for carbonate precipitation33,34. Also, it was clear from these previous studies, that rhodoliths have a fraction of living carbonate cryptofauna and/or epifauna, including Foraminifera (Homotrema rubrum), Polychaeta (encrusting calcareous tubes), Bryozoa, and Mollusca (Vermetidae) phyla33.

The GARS is considered an ecotone of biodiversity between Brazil and the southern Caribbean, possibly acting as an ecological corridor between the South and North Atlantic. It comprises a high diversity of habitats and large areas dominated by healthy reef-building organisms (mostly crustose calcareous algae)4. Reef growth and high structural complexity are presently concentrated in the central and southern sectors, which are shallower and with higher light incidence over the bottom wealth. Net reef growth estimates (i.e. considering both, reef accretion and erosion) are scarce even for shallow reefs. Only recently, this question started to be addressed for mesophotic reefs35,36. Similar studies are urgently needed for the GARS, particularly considering its ecological importance and the threats posed by large scale oil and gas exploration in the region4.

Conclusions

The analysis of previously published and new radiocarbon data from the GARS allowed us to recognize a Northwest-Southeast growing trend of the reef complex. Older ages correspond to samples from the northern sector, in areas located below the present plume of the Amazon River. These ages refer to the carbonates that sustained the reef during MIS2 and to the beginning of the last deglacial. After a gap, occurred between ca. 12,100 and 7,100 cal BP, the reef extended to the Central and Southern sector of the area. This gap corresponds to the time interval of acceleration of sea-level rise and plume development, after the Younger Dryas (Melt Water Pulse 1B).

Modern radiocarbon ages, obtained in rhodoliths and sponges, are present in the three sectors, indicating that differently than suggested, living organisms inhabit the GARS in its totality.

Methods

As a convention, in this work, we keep the same proposal of three sectors (North, Central, and South) as stated by3. Besides our new radiocarbon data, we gathered dating information from other sources3,8,37 in order to evaluate the modern or relict character of the reef complex. When available, all of the conventional radiocarbon datings were recalibrated using software Calib 7.138, using the Marine13 calibration curve39 and a global reservoir effect. Ages published in37 are presented “as is” (only calibrated ages, without the 2σ interval), since we did not have access to the original data. We also dated ten other samples (Table 1) of carbonates from different marine organisms from the three sectors at Beta Analytic (Miami, USA).

In order to compare our data with sea-level changes, and due to a lack of a reliable Late Quaternary sea-level curve for northern Brazil, we used the global curve proposed by22.

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), via the IODP/CAPES-Brasil program, as well as by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq). M.M.M., E.S., C.E.R., F.T. and N.E.A are CNPq Research Fellows.

Author Contributions

M.M. de M., E.S., F.T. and N.E.A. designed the study. M.M. de M., E.S., J.D.G. and N.E.A. performed the analyses. M.M. de M., E.S., R.B.F.F. and N.E.A. wrote the paper, with input and revision from all authors (M.M.M., E.S., R.B.F.F., C.E.R., F.T., J.D.G. and N.E.A.).

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Collette, B. B. & Rützler, K. In Third International Reef Symposium Vol. Proceedings 305–310 (Rosenstiel School of Marine Sciences, Miami, 1977).

- 2.Cordeiro RTS, Neves BM, Rosa-Filho JS, Pérez CD. Mesophotic coral ecosystems occur offshore and north of the Amazon River. Bulletin of Marine Science. 2015;91:491–510. doi: 10.5343/bms.2015.1025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moura RL, et al. An extensive reef system at the Amazon River mouth. Science Advances. 2016;2:e1501252–e1501252. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Francini-Filho, R. B. et al. Perspectives on the Great Amazon Reef: Extension, Biodiversity, and Threats. Frontiers in Marine Science5, 10.3389/fmars.2018.00142 (2018).

- 5.Francini-Filho, R. B. et al. In Mesophotic Coral Ecosystems Coral Reefs of the World (ed. Loya, Y.) Ch. Chapter 10, 163–198 (Springer, 2019).

- 6.Soares MDO, Tavares TCL, Carneiro PBDM, Beger M. Mesophotic ecosystems: Distribution, impacts and conservation in the South Atlantic. Diversity and Distributions. 2018 doi: 10.1111/ddi.12846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Figueiredo, A. G. In 49 Congresso Brasileiro de Geologia (ed. Sociedade Brasileira de Geologia) 1 (Sociedade Brasileira de Geologia, Rio de Janeiro, 2018).

- 8.Milliman JD, Barretto HT. Relict magnesian calcite oolite and subsidence of the Amazon shelf. Sedimentology. 1975;22:137–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3091.1975.tb00288.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosence DWJ. Coralline algal reef frameworks. Journal of the Geological Society. 1983;140:365–376. doi: 10.1144/gsjgs.140.3.0365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Omachi CY, et al. Light availability for reef-building organisms in a plume-influenced shelf. Continental Shelf Research. 2019;181:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.csr.2019.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar N, Damuth JE, Gorini MA. Relict magnesian calcite oolite and subsidence of the Amazon shelf. Sedimentology. 1977;24:143–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3091.1977.tb00124.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nittrouer CA, et al. The geological record preserved by Amazon shelf sedimentation. Continental Shelf Research. 1996;16:817–841. doi: 10.1016/0278-4343(95)00053-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nittrouer CA, Sharara MT, deMaster DJ. Variations of sediment texture on the Amazon continental shelf. Journal of Sedimentary Research. 1983;53:179–191. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leão, Z. M. A. N. & Ginsburg, R. N. In 8th International Coral Reef Symposium Vol. 2 1767–1772 (University of Panama, Panama City, 1997).

- 15.Francini-Filho RB, et al. Dynamics of coral reef benthic assemblages of the Abrolhos Bank, eastern Brazil: inferences on natural and anthropogenic drivers. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coni, E. O. C. et al. Modeling abundance, growth, and health of the solitary coral Scolymia wellsi (Mussidae) in turbid SW Atlantic coral reefs. Marine Biology164, 10.1007/s00227-017-3090-4 (2017).

- 17.Meade RH, Dunne T, Richey JE, DE M Santos U, Salati E. Storage and remobilization of suspended sediment in the lower Amazon river of Brazil. Science. 1985;228:488–490. doi: 10.1126/science.228.4698.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lentz Steven J. The Amazon River Plume during AMASSEDS: Subtidal current variability and the importance of wind forcing. Journal of Geophysical Research. 1995;100(C2):2377. doi: 10.1029/94JC00343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asp NE, et al. Sediment dynamics of a tropical tide-dominated estuary: Turbidity maximum, mangroves and the role of the Amazon River sediment load. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 2018;214:10–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2018.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pianca C, Mazzini PLF, Siegle E. Brazilian offshore wave climate based on NWW3 reanalysis. Brazilian Journal of Oceanography. 2010;58:53–70. doi: 10.1590/s1679-87592010000100006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beardsley Robert C., Candela Julio, Limeburner Richard, Geyer W. Rockwell, Lentz Steven J., Castro Belmiro M., Cacchione David, Carneiro Nelson. The M2tide on the Amazon Shelf. Journal of Geophysical Research. 1995;100(C2):2283. doi: 10.1029/94JC01688. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lisiecki LE, Raymo ME. A Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18O records. Paleoceanography. 2005;20:n/a-n/a. doi: 10.1029/2004PA001071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barker S, et al. Interhemispheric Atlantic seesaw response during the last deglaciation. Nature. 2009;457:1097–1102. doi: 10.1038/nature07770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Follett CL, Repeta DJ, Rothman DH, Xu L, Santinelli C. Hidden cycle of dissolved organic carbon in the deep ocean. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:16706–16711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407445111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rohling EJ, et al. Sea-level and deep-sea-temperature variability over the past 5.3 million years. Nature. 2014;508:477–482. doi: 10.1038/nature13230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marceniuk, A. P. et al. The bony fishes (Teleostei) caught by industrial trawlers off the Brazilian North coast, with insights into its conservation. Neotropical Ichthyology17, 10.1590/1982-0224-20180038 (2019).

- 27.Diaz MR, Eberli GP. Decoding the mechanism of formation in marine ooids: A review. Earth-Science Reviews. 2019;190:536–556. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2018.12.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hemming, S. R. Heinrich events: Massive late Pleistocene detritus layers of the North Atlantic and their global climate imprint. Reviews of Geophysics42, 10.1029/2003rg000128 (2004).

- 29.Rocha LA, et al. Mesophotic coral ecosystems are threatened and ecologically distinct from shallow water reefs. Science. 2018;361:281–284. doi: 10.1126/science.aaq1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bard E, Hamelin B, Delanghe-Sabatier D. Deglacial meltwater pulse 1B and Younger Dryas sea levels revisited with boreholes at Tahiti. Science. 2010;327:1235–1237. doi: 10.1126/science.1180557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abdul NA, Mortlock RA, Wright JD, Fairbanks RG. Younger Dryas sea level and meltwater pulse 1B recorded in Barbados reef crest coralAcropora palmata. Paleoceanography. 2016;31:330–344. doi: 10.1002/2015pa002847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Milliman, J. D., Summerhayes, C. P. & Barretto, H. T. Quaternary Sedimentation on the Amazon Continental Margin: A Model. Geological Society of America Bulletin86, 10.1130/0016-7606(1975)86<610:Qsotac>2.0.Co;2 (1975).

- 33.Cavalcanti GS, et al. Physiologic and metagenomic attributes of the rhodoliths forming the largest CaCO3 bed in the South Atlantic Ocean. ISME J. 2014;8:52–62. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cavalcanti GS, et al. Rhodoliths holobionts in a changing ocean: host-microbes interactions mediate coralline algae resilience under ocean acidification. BMC Genomics. 2018;19:701. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-5064-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weinstein DK, Smith TB, Klaus JS. Mesophotic bioerosion: Variability and structural impact on U.S. Virgin Island deep reefs. Geomorphology. 2014;222:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.geomorph.2014.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weinstein DK, et al. Coral growth, bioerosion, and secondary accretion of living orbicellid corals from mesophotic reefs in the US Virgin Islands. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2016;559:45–63. doi: 10.3354/meps11883. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vale NF, et al. Structure and composition of rhodoliths from the Amazon River mouth, Brazil. Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 2018;84:149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jsames.2018.03.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.CALIB 7.1 [WWW program] at, http://calib.org, accessed 2018-12-31 (2018).

- 39.Reimer PJ, et al. IntCal13 and Marine13 Radiocarbon Age Calibration Curves 0–50,000 Years cal BP. Radiocarbon. 2016;55:1869–1887. doi: 10.2458/azu_js_rc.55.16947. [DOI] [Google Scholar]