Abstract

Parry-Romberg syndrome is a rare disorder with progressive hemifacial atrophy of unknown etiology. We reported 2 cases of progressive hemifacial atrophy with different neurological manifestations from Kuwait. The first case was a 14-year-old boy who initially presented with recurrent transient stroke-like episodes followed by focal seizures and hemifacial atrophy. Magnetic resonance imaging showed significant white matter changes and cerebral hemiatrophy. The second case was a 7-year-old girl who presented with complex partial seizures and hemifacial atrophy, her magnetic resonance imaging scan showed minimal changes in the hemiatrophy of the temporal cerebral lobe. Both patients’ disease activity was well controlled with immunosuppressive therapy and anticonvulsants. Parry-Romberg syndrome should be considered in any child with unexplained neurological symptoms.

Parry-Romberg syndrome is an uncommon acquired neurocutaneous disorder that is characterized by progressive unilateral atrophy of the face. The trunk and limb involvement is rare.1,2 Parry (1825) and Romberg (1846) described the syndrome initially and subsequently in 1871; Eulenberg coined the term progressive facial hemiatrophy.3 It usually manifests in late childhood or adolescent period of life and slowly progresses over up to 20 years and then stabilizes.1 The etiology is unknown and possible etiologies includes viral, genetic, autoimmunity and altered autonomic imbalance that could lead to facial atrophy and cerebral atrophy.4

The disease is more common in females and approximate incidence of the disease per year is 3/100000. The neurological manifestation can occur quite early in the natural history and the mean age at onset of the neurological symptoms was 20.9 (1.5-73 years).5 Neurological symptoms may occur earlier than the skin lesions and it is not correlated with facial atrophy.6 The hemifacial atrophy can be accompanied by focal neurological deficit such as hemiplegic migraine7 and rarely ischemic stroke.8

Parry-Romberg syndrome mainly affects one side of the face including skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, cartilage, and bone leading to the hemifacial atrophy. Sometimes hyperpigmentation or depigmentation, alopecia also noted.3 Current evidence suggests that a 1-2 year course of methotrexate is the most effective treatment for inducing prolonged remission.

Case Report

Case 1: Patient information

. A 14-year-old Kuwaiti boy who presented at the age of 10 years with recurrent, transient stroke-like attacks. He felt numbness and heaviness on the right side and difficulty using his right hand for 15-20 minutes. There was no loss of consciousness or speech disturbance, although he experienced mild headache in the left frontotemporal area for 5 minutes. After 3 months, the patient started to have right focal seizures without loss of consciousness lasting approximately 3-4 minutes. The seizure frequency was 2-3 episodes per month.

Clinical findings

Neurological examination was normal and there was no focal neurological deficit. Two years later, he developed darkening of the left side of his face that progressed to hemiatrophy with hardening of the skin of the forehead, cheek and nose, as well as alopecia on the left side of scalp (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Area of depression that involved the region near his hairline (A). With depression of his left nostril with some alopecia involving the left frontal scalp (B).

Figure 2.

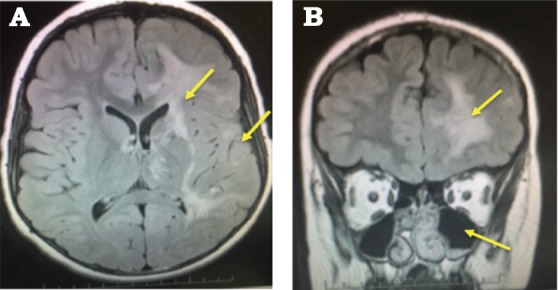

A) Signal hyperintensities of the left white matter and cerebral atrophy. B) Coronal section shows shrinkage of the left orbit and maxillary sinus enlargement

Diagnostic assessment

His complete hemogram, liver function test and renal function test revealed normal values. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and c-reactive protein (CRP) were normal. Also the C3, C4 normal. ANA, P-ANCA, C-ANCA, anti- phospholipid AB, anti- cardiolipin AB and Von willebrand factor antigen were negative.

Serum angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) level and serum homocysteine level normal. Lactate, ammonia, urine organic acid screen, and blood amino acid revealed no significant abnormality. Hyper coagulation screen normal. Gene test for mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like, myoclonic epilepsy with ragged red fibers were negative. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) values are normal except mild increase in the CSF protein 48 mg/dL (normal value 15-45mg/dL). Immunoglobulin oligoclonal bands absent.

An electroencephalogram (EEG) showed focal cerebral dysfunction in the left anterior quadrant and epileptiform abnormalities in the left parasagittal area.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain scan revealed increased signal intensities in the left hemisphere, mainly in the frontal lobe, with multiple areas of microhemorrhages and calcifications (Figure 3). Magnetic Resonance Angiography and magnetic resonance venography were normal.

Figure 3.

A) left-sided atrophy with hyperpigmentation, b) area of alopecia on frontal scalp

Therapeutic intervention

His seizures were well controlled with oxcarbazepine. His disease activity was well controlled with a course of prednisolone for one year then phased out. Methotrexate also started together and he is taking it until now.

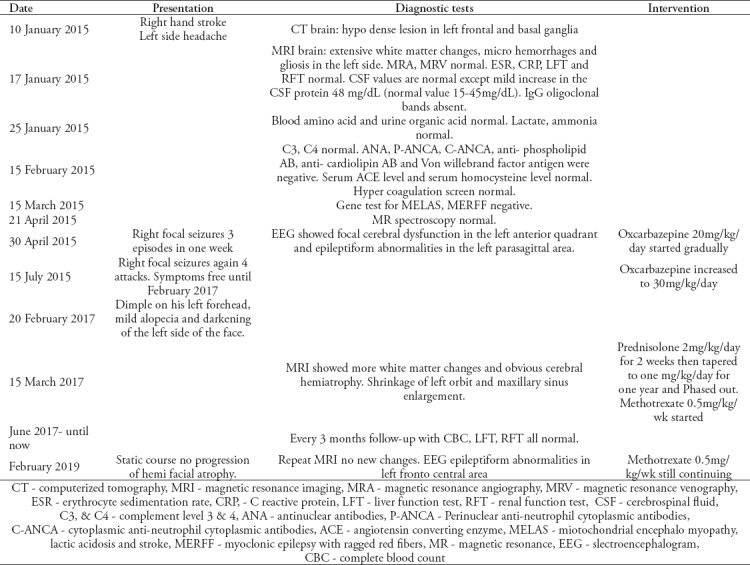

Table 1.

Timeline of a 14 year old boy normal birth history and development. He started having symptoms from the age of 10 years. No family history of any neurological illness.

Follow-up and outcomes

He is seizure free for more than 3 years and follow-up MRI showed static course and no progression of hemi facial atrophy.

Case 2: Patient information

A 7-year-old Kuwaiti girl started to have right focal seizures with secondary generalization at the age of 5 years. Her seizures were initially controlled with an anticonvulsant for one year and then she started to have frequent seizures (2-3 episodes per week). Her birth history and development was normal. There was family history of epilepsy with her mother and her school performance was average.

Clinical findings

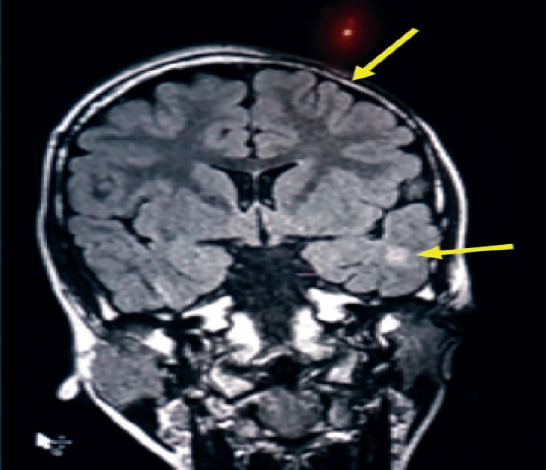

She was found to have hyperpigmentation and hardening of the skin in addition to alopecia over the left side of her face. With time, hemiatrophy of the face started to become more obvious (Figure 3). Her neurological examination was normal and there was no focal neurological deficit.

Diagnostic assessment

complete hemogram, liver function test and renal function test revealed normal values. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and CRP were normal, also C3, C4 were normal. ANA, P-ANCA, C-ANCA were negative. Electroencephalogram showed spike wave activity over the left centro temporal area. The computed tomography brain scan showed left temporal lobe calcification. The MRI showed hemiatrophy of the left cerebral hemisphere with signal intensity in the left temporal lobe (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Hemiatrophy of the left side with abnormal signal in the subcortical left temporal region and left periventricular area.

Therapeutic intervention

Her seizure activity initially was controlled with sodium valproate for one year and then she started to have frequent seizures which were controlled with oxcarbazepine and levetiracetam. She was also treated with prednisolone for one year and phased out and methotrexate was started along with prednisolone and still going on.

Follow-up and outcomes

Her seizures were well controlled with anticonvulsant and disease activities stable confirmed with follow-up MRI. Periodic complete blood count and liver functions test were normal.

Discussion

As per the Stone et al9 global survey of 205 patients on Parry-Romberg syndrome only 11% of the patients had epilepsy and median age of on set was 10 years. Both of our patients started symptoms at in the first decade of life and also had seizures.

Case 1 had fewer seizures but more MRI changes than case 2. Case 2 had more skin changes and seizures but fewer MRI changes than case 1. Patient 1 had mild enophthalmos and sinus enlargement on the left side, which has been reported in Parry-Romberg syndrome.

Though few cases of Parry-Romberg syndrome had been reported from the Middle East region9 most of them were adult except as case from Egypt 11 year old boy and most of the cases reported with hemifacial atrophy none of the cases were reported with neurological manifestation like epilepsy, stroke like episode and typical MRI brain changes.5

The study carried out by Vix J et al,5 showed MRI brain abnormalities were noted in 75% of patients. Cerebral atrophy was noted in only 20.5% of the patients along with skin changes and CT brain calcification noted in 12% of the patients. Our cases showed similar findings supporting the classical neuroimaging finding of Parry-Romberg syndrome. Electroencephalogram is abnormal in 48% of his study and our cases both had EEG changes.5 Cerebrospinal fluid protein was mildly elevated in our case 1 suggestive of inflammatory process which is unusal according to Vix et al,5 but in other studies mildly elevated protein is noted.2

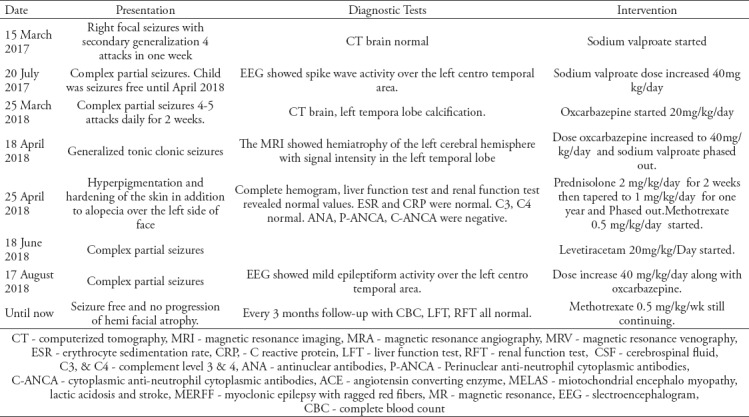

Table 2.

Timeline of a 7 year old girl normal birth history and development. she started having symptoms from the age of 5 years. No family history of any neurological illness.

Guerrerosantos et al,10 classified Parry-Romberg syndrome into 4 types: type 1 & 2 (mild) involvement of the skin and soft tissue of the face, type 3 & 4(severe) involvement of bone and cartilage.

The common neurological manifestations includes trigeminal neuralgia, migraine, facial paresthesia, and seizures.2 Occasionally vascular malformations and intracranial aneurysms are observed. Skin biopsies may reveal epithelial and dermal tissue atrophy resembling linear scleroderma.

There is no definitive cure for Parry-Romberg syndrome and multidisciplinary team approach is needed for management. The active stage of the disease may be treated with corticosteroids and immunosuppressant therapies. Milder types (1 & 2) treated with autologous fat graft and severe types(3& 4) needed surgical reconstruction once disease is stabilized.2

In conclusion, Parry-Romberg syndrome is a rare acquired neurocutaneous disorder with progressive unilateral facial atrophy of unclear etiology. We report 2 cases of Parry-Romberg syndrome with different neurological manifestations from the Kuwait though cases has been reported with Middle East without neurological symptoms. Skin examination is essential in any patient with unexplained neurological symptoms. Localized scleroderma can be accompanied by neurological symptoms. Active disease can be managed with immunosuppressant.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Madasamy R, Jayanandan M, Adhavan UR, Gopalakrishnan S, Mahendra L. Parry Romberg syndrome:A case report and discussion. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2012;16:406–410. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.102498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aydın H, Yologlu Z, Sargın H, Metin MR. Parry-Romberg syndrome. Physical, clinical, and imaging features. Neurosciences (Riyadh) 2015;20:368–371. doi: 10.17712/nsj.2015.4.20150142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Kehdy J, Abbas O, Rubeiz N. A review of Parry-Romberg syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:769–784. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trisal D, Kumar N, Dembla G, Sundriyal D. Parry-Romberg syndrome:uncommon but interesting. BMJ Case Rep 2014. 2014 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-201969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vix J, Mathis S, Lacoste M, Guillevin R, Neau JP. Neurological manifestations in Parry-Romberg syndrome:2 case reports. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1147. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lis-Święty A, Brzezińska-Wcisło L, Arasiewicz H. Neurological abnormalities in localized scleroderma of the face and head:a case series study for evaluation of imaging findings and clinical course. Int J Neurosci. 2017;127:835–839. doi: 10.1080/00207454.2016.1244823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amaral TN, Marques Neto JF, Lapa AT, Peres FA, Guirau CR, Appenzeller S. Neurologic involvement in scleroderma en coup de sabre. Autoimmune Dis 2012. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/719685. 719685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanzato N, Matsuzaki T, Komine Y, Saito M, Saito A, Yoshio T, et al. Localized scleroderma associated with progressing ischemic stroke. J Neurol Sci. 1999;163:86–89. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00267-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stone J. Parry-Romberg syndrome:a global survey of 205 patients using the Internet. Neurology. 2003;61:674–676. doi: 10.1212/wnl.61.5.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guerrerosantos J, Guerrerosantos F, Orozco J. Classification and treatment of facial atrophy in Parry-Romberg disease. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2007;31:424–434. doi: 10.1007/s00266-006-0215-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]