Abstract

Leukemia stem cells (LSCs) are responsible for therapeutic failure and relapse of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. As a result of the interplay between LSCs and bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs), cancer cells may escape from chemotherapy and immune surveillance, thereby promoting leukemia progress and relapse. The present study identified that the crosstalk between LSCs and BM-MSCs may contribute to changes of immune phenotypes and expression of hematopoietic factors in BM-MSCs. Furthermore, Illumina Genome Analyzer/Hiseq 2000 identified 7 differentially expressed genes between BM-MSCsLSC and BM-MSCs. The Illumina sequencing results were further validated by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Following LSC simulation, 2 genes were significantly upregulated, whereas the remaining 2 genes were significantly downregulated in MSCs. The most remarkable changes were identified in the expression levels of lumican (LUM) gene. These results were confirmed by western blot analysis. In addition, decreased LUM expression led to decreased apoptosis, and promoted chemoresistance to VP-16 in Nalm-6 cells. These results suggest that downregulation of LUM expression in BM-MSCs contribute to the anti-apoptotic properties and resistance to chemotherapy in LSCs.

Keywords: leukemia stem cell, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, lumican, Illumina sequencing

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common malignancy of childhood cancer. Treatment of pediatric ALL is effective as chemotherapy results in the treatment of >80–85% ALL pediatric patients (1–4). Nevertheless, a total of 20–30% of pediatric patients will ultimately relapse and succumb to the disease. Residual leukemia stem cells (LSCs) are chemoresistant cells, which are able to escape from immune surveillance. These abilities may be responsible for therapeutic failure and relapse of ALL (5). LSCs may be regulated by bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs), which in turn may improve the survival of LSCs by providing the necessary cytokines and cell contact-mediated signals. For instance, previous experimental data indicated that LSCs accumulated in close association with BM-MSCs, which might regulate their proliferation, differentiation and chemoresistance (6). Therefore, it is critical to further understand the association between LSCs and BM-MSCs.

The finding of ‘donor cell leukemia’ (DCL) confirms the important role of the hematopoietic microenvironment in hematopoietic stem cell regulation (7). BM-MSCs, an important component of the BM environment, act as hematopoietic regulators through producing cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules and extracellular matrix molecules. BM-MSCs are also considered as a major source for the secretion of the homeostatic chemokine, stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) also known as C-X-C motif chemokine 12 (CXCL12), which serves a critical role as a homing signal of circulating HSCs, and in the regulation of immune responses (8). However, whether LSC may influence the hematopoietic microenvironment remains poorly studied. In the present study, CD34+ cells were isolated from Nalm-6 cells and used as LSCs in further experiments. CD34 protein is used as a surface marker to identify hematopoietic stem cells and LSCs (9). Subsequently, the effect of LSCs stimulation on immunophenotype and expression of hematopoietic genes in BM-MSCs was evaluated. A gene sequencing method was used to detect the changes of gene expression levels in MSCs induced by LSCs.

Materials and methods

Cell cultures

The human pre-B cell leukemia Nalm-6 cell line, was supplied by The American Type Culture Collection and was cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 100 U/ml penicillin G and 100 mg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Human BM-MSCs were purchased from ScienCell Research Laboratories, Inc. and cultured in low-glucose DMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10%, 100 U/ml penicillin G and 100 mg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator.

CD34 positive B-lineage LSCs enrichment

CD34 protein was used as a surface marker to identify LSCs in Nalm-6. CD34 positive cells were isolated from Nalm-6 cells through immunomagnetic bead-positive selection using a CD34+ MicroBead kit (Miltenyi Biotech, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions to a purity of 90–96% as determined by flow cytometry. Purity was confirmed by flow cytometry with anti-CD34 (dilution 1:10, phycoerythrin-labeled; cat. No. 550761; BD Pharmingen) and was >95% in all experiments.

Co-culture of LSCs with BM-MSCs

To study the effect of Nalm-6 cell stimulation on BM-MSCs, LSCs were co-cultured with an adherent monolayer of BM-MSCs at a 10:1 ratio for 24–72 h. To perform co-culture experiments, continuous culture of BM-MSCs was maintained and plated at a concentration of 1×105 cells/well, 24 h before adding LSC cells at a concentration of 1×106 cells/well. Although LSCs are constantly interacting with stroma, these lymphocytes do not adhere to plastic or to BM-MSCs. Co-cultured LSCs were carefully separated from BM-MSCs monolayer by pipetting with ice-cold PBS, leaving the adherent BM-MSCs layer undisturbed. Subsequently, BM-MSCs were trypsinized and used for transcriptome sequencing, and pharmacological and biochemical end points.

Detection of BM-MSCs immune-phenotype using flow cytometry

BM-MSCs and BM-MSCsLSC were collected and treated with 0.25% trypsin. The cells were individually stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate or phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-marker monoclonal antibodies in 100 µl PBS for 15 min at room temperature or for 30 min at 4°C, as recommended by the manufacturer. The antibodies used were specific for the human antigens, CD29 (cat. No. 557332), CD31 (cat. No. 560983), CD34 (Cat. 550761), CD44 (Cat. 562818), CD45 (cat. No. 560975), CD73 (cat. No. 562430), CD90 (cat. No. 561970), and CD105 (cat. No. 560839; all at 1:10; all from BD Pharmingen). Cells were analyzed on a flow cytometry system (Guava easyCyte8HT; EMD Millipore) with the Guava Incyte software (version 2.8; EMD Millipore). Positive cells were counted and the signals for the corresponding immunoglobulin isotypes were compared.

Transcriptome sample preparation and sequencing

Total RNA was isolated from BM-MSCs using TRIzol® (Ambion, RNA Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's procedures. RNA integrity was assessed using the RNA6000 Pico assay kit on the Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Sequencing libraries were generated using the Illumina TruSeq™ RNA sample preparation kit (Illumina, Inc.) following the manufacturer's recommendations and 4 index codes were added to attribute sequences to each sample. The clustering of the index-coded samples was performed on a cBot Cluster Generation system using TruSeq PE Cluster kit v3-cBot-HS (Illumina, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After cluster generation, the library preparations were sequenced on an Illumina Hiseq2000 platform and 100 bp paired-end reads were generated.

Sequencing data analysis

Quality control: Raw data (raw reads) in the fastq format were firstly processed through in-house perl script. Differential expression analysis of two conditions/groups (two biological replicates per condition) was performed using the DESeq R package (version 1.10.1) (10). DESeq provides statistica1 routines for determining differentia1 expression in digital gene expression data using a model based on the negative binomial distribution. The resulting P-values were adjusted using the Benjamini and Hochberg approach for controlling the fake discovery rate. Genes with an adjusted P-value <0.05 found by DESeq were assigned as differentially expressed. Differential expression analysis of two conditions was performed using the DEGSeq R package (version 1.12.0) (11). The P-values were adjusted using the Benjamini and Hochberg method. Corrected P-value of <0.005 and 1og 2 (fold-change) of 1 were set as the threshold for significantly differential expression.

RNA isolation and reverse-transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

RT-qPCR analysis was performed to confirm the expression profiles obtained from RNA sequencing. Total cellular RNA was isolated from BM-MSCs and BM-MSCsLSC using TRIzol® (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) as per the manufacturer's protocol. Nucleotide sequences of primers used for PCR analysis are listed in Table I. For each set of primers, a gradient PCR was performed to determine the optimal annealing temperature. Optimal annealing temperature was determined using 1°C increments in 12 different wells. The thermocycling conditions were as follows: 10 min at 95°C for initial denaturation; and 35 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 30 sec. cDNA purified from BM-MSCs were used as template. A high annealing temperature was used to prevent or limit non-specific binding. qPCR was performed using an ABI 7500 PCR system (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and SYBR-Green I dye (Toyobo Life Science). Serial dilutions of cDNA samples (between 1:10 and 1:1,000) were analyzed to determine efficiency and dynamic range of the PCR, using GAPDH as endogenous control. Each gene expression relative to β-actin was determined using the 2−∆ΔCq method (12), where ∆Cq=(Cqtarget gene-Cqβ-actin). Total RNA (0.2 µg) was reverse transcribed in a 20 µl reaction mixture containing the following components: 1X RT buffer, deoxynucleotide triphosphate mix (5 mM each), RNase inhibitor (10 U/µl RNaseOut; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and 4 units Omniscript reverse transcriptase (Qiagen GmbH). Each sample was reversed transcribed for 30 min at 38°C. By optimizing the annealing temperature, the thermocycling conditions of PCR were as follows: 10 min at 95°C for initial denaturation; and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 2 min. Successful amplification was determined by the presence of a single dissociation peak on the thermal melting curve. Data were analyzed with the sequence detection software (version 1.4; Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Results are expressed as the normalized fold expression for each gene. Reported data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Table I.

Primer sequences for quantitative PCR.

| Name | Sequence (5′-3′) | Product size, bp |

|---|---|---|

| GAPDH-F | GACAGTCAGCCGCATCTTCT | 104 |

| GAPDH-R | GCGCCCAATACGACCAAATC | |

| IL-1α-F | GACGCCCTCAATCAAAGTATAATTC | 89 |

| IL-1α-R | TCAAATTTCACTGCTTCATCCAGAT | |

| IL-1β-F | GCGGCATCCAGCTACGAAT | 80 |

| IL-1β-R | GTCCATGGCCACAACAACTG | |

| IL-10-F | GCCTTGTCTGAGATGATCCAGTT | 85 |

| IL-10-R | TCACATGCGCCTTGATGTCT | |

| IL-6-F | GCAAAGAGGCACTGGCAGAA | 93 |

| IL-6-R | GGCAAGTCTCCTCATTGAATCC | |

| IL-7-F | AACCAGCTGCAGAGATCACC | 86 |

| IL-7-R | CTCACCGCCCATAGTCACTC | |

| IL-11-F | ACATGAACTGTGTTTGCCGC | 104 |

| IL-11-R | GTCTGGGGAAACTCGAGGG | |

| SCF-F | TCGATGACCTTGTGGAGTGC | 84 |

| SCF-R | TAAAGAGCCTGGGTTCTGGG | |

| IL-3-F | GACTCCAAGCTCCCATGACC | 116 |

| IL-3-R | GTCCAGCAAAGGCAAAGGTG | |

| G-CSF-F | TTGACTCCCGAACATCACCG | 128 |

| G-CSF-R | CAAGGCAAATGTCCAGGCAC | |

| SDF-1-F | AGATTGTAGCCCGGCTGAAG | 134 |

| SDF-1-R | GTGGGTCTAGCGGAAAGTCC | |

| LIF-F | TGGGCCAATTTGTGGAGAGG | 115 |

| LIF-R | TATCTGCCAGGAACAGTGCG | |

| TRIB3-F | GAGACTCGCAGCGGAAGTG | 139 |

| TRIB3-R | CTCAGAGCCTCCAGGGCA | |

| SLC7A5-F | TCATCATCCGGCCTTCATCG | 134 |

| SLC7A5-R | GAGCAGCAGCACGCAGA | |

| WSB1-F | GTCAACGAGAAAGAGATCGTGAG | 152 |

| WSB1-R | ACTGTGCGATGTCCTTGTGA | |

| NKTR-F | GGAGCAGAGGATGGTACAGC | 139 |

| NKTR-R | GTGTAGGACCTGGATCGACTG | |

| LUM-F | CCGTCCTGACAGAGTTCACAG | 111 |

| LUM-R | TGGCAAATGGTTTGAATCCTTACTG | |

| OGT-F | GCTGCTGCCCTTGTACTACT | 150 |

| OGT-R | ACGTTTCGTTGGTTCTGTGC | |

| LENG8-F | CGAAGGATCCTGGTTGACAGT | 135 |

| LENG8-R | CAGCCACCATGCTGTACTGA |

F, forward; R, reverse; IL, interleukin; SCF, SKP1-CUL1-F protein; G-CSF, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor; LIF, leukemia inhibitory factor; SDF-1, stromal cell-derived factor 1; SLC7A5, solute carrier family 7 member 5; TRIB3, tribbles pseudokinase 3; WSB1, WD repeat and SOCS box containing 1; NKTR, natural killer cell triggering receptor; LUM, lumican; OGT, O-linked N-acteylglucosamine (GlcNAc) transferase; LENG8, leukocyte receptor cluster member 8.

Recombinant plasmid construction and transfection

To study the effects of the overexpression and downregulation of the lumican (LUM) gene, pcDNA3.1-LUM and 3 small interfering RNA (siRNA) sequences targeting LUM were designed and synthesized (Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd.). The nucleotide sequences of the 3 groups were as follows: Group 329 (the number represents the starting position of the different siRNA cleavages on the mRNA sequence), 5′-CTGCTTTAAGAATTAACGAAAGC-3′, group 437, 5′-CAGTGGCCAGTACTATGATTATGAT-3′, and group 467, 5′-CCTATCAATTTATGGGCAATCATCA-3′. For construction of the expression plasmid, the Lumican inserts were isolated by PCR amplification (Novoprotein) from a cDNA library (GeneChem, Inc.) and digested with the restriction endonucleases EcoRI and BglII (MBI Fermentas; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and linked into the pcDNA3.1 expression plasmids (Bio-Asia Company) with T4 DNA ligase (TransGen Biotech, Co., Ltd.). The ligation products were transformed into competent Escherichia coli DH5α (TransGen Biotech, Co., Ltd.) and then selected using the kanamycin resistance method. Recombinant plasmids were sequenced (ABI Prism 3100 DNA Sequencer; Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and confirmed to contain the entire coding sequence of LUM.

The cells were seeded into 6-well plates and cultured to 70% confluence for siRNA transfection (25 nM) and plasmid transfection, respectively, for 24 h. Transfection was performed using Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's protocol, and the culture medium was replaced after 6 h of incubation. After 72 h of transfection, the cells were counted and subjected to cell cycling and apoptosis assay, and western blot analysis. The untransfected cells were considered to be blank control, and the cells transfected with scrambled siRNA (5′-CATCATAAGTCACGTACTGTAGTGT-3′) were considered as the negative controls (NCs) for the downregulation experiments. The cells transfected with Lipofectamine only (Mock) or pcDNA3.1 (empty vector) were considered as the control for the upregulation experiments. Cells transfected with the BLOCK-iT™ Alexa Fluor® Red Fluorescent Control (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) were used to determine the transfection efficiency of siRNA.

Cell cycling analysis of BM-MSCs-LUM+/- to Nalm-6 cells

The experiment was divided into 4 groups: Normal nalm-6 cells, nalm-6+normal BM-MSCs, nalm-6+BM-MSCs-cDNA3.1- LUM, and nalm-6+BM-MSCs-LUM-437 groups. After co-culture for 24 h, a total of 1×106 nalm-6 cells collected from each group and were washed three times with PBS and resuspended in 50 µl PBS. Resuspended cells were added, dropwise, into a tube containing 1 ml ice cold 70% ethanol while vortexing at medium speed. The tubes were frozen at −20°C for 3 h prior to staining. Afterwards, the cells were washed and treated with propidium iodide (PI) staining kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After 30 min of incubation at room temperature in the dark, cell suspension samples were transferred into 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes and analyzed using a flow cytometry system (Guava easyCyte8HT; EMD Millipore) and Guava Incyte software (version 2.8; EMD Millipore). Results were expressed as the percentage of cells in each cell cycle phase, and error bars represented standard error of the mean (SEM).

Cell apoptosis assay

Nalm-6 cell apoptosis was determined using flow cytometry with AnnexinV/PI double staining (Cat. 556547, BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The cells were grouped into the different groups as aforementioned. A total of 1×105 cells from each group were collected by centrifugation (800 × g, 5 min, at 4°C) and washed with PBS. Cells were resuspended in PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) and 1% FBS, mixed with the Annexin V and PI reagent, and subsequently incubated for 20 min at room temperature in the dark. Analyses were performed using a Guava easyCyte 8HT flow cytometer (EMD Millipore), and the data were analyzed using Guava Incyte software (version 2.8; EMD Millipore) Results were expressed as the percentage of apoptotic cells, and error bars represented SEM.

Cytotoxicity assay of VP-16

The effect of BM-MSCs- LUM+/- on the sensitivity of the Nalm-6 cell line to VP-16 (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) was evaluated using Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) assay. The experiment was divided into 5 groups: VP-16+Nalm-6 cells (control group), VP-16 + Nalm-6 cells + normal BM-MSCs (group 1), VP-16 + Nalm-6 + BM-MSCs-LUM-329 (group 2), VP-16 + Nalm-6 + BM-MSCs-LUM-437 (group 3)., and VP-16 + Nalm-6 + BM-MSCs-cDNA3.1-LUM (group 4) The cells treated with only 0.9% normal saline were used as VP-16 blank controls. In brief, the Nalm-6 cells were cultivated at a density of 2×104 cells/well in 96-well culture plates, groups 2, 3, 4, and 5 were pre-layered with BM-MSCs as the feeder cells. Nalm-6 cells were treated with various concentrations of VP-16 (0, 0.05, 0.1 and 0.5 µg/ml). After 48 h of culture, the cytotoxicity of the treatments was determined using CCK-8 dye according to the manufacturer's instructions. The generated formazan was determined using a model 450 microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) at an optical density of 570 nm to determine cell viability. Survival rate (SR) was calculated using the following equation: SR (%)=(A Test/A Control) ×100%.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SEM from three separate experiments. Data were analyzed using the Student's t-test for comparison between two groups or Tukey's post-hoc tests for comparison among multiple groups as appropriate. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 17.0; SPSS, Inc.).

Results

LSCs regulate the phenotype and the expression of hematopoietic factors in BM-MSCs

Following LSCs simulation for 24–72 h, the expression levels of cell surface proteins on BM-MSCs were evaluated by flow cytometry. The results showed that there were no significant differences in the expression of surface markers observed except for CD44 and CD105, CD44 was significantly upregulated and CD105 was downregulated (Table II).

Table II.

Effect of LSCs on the immunophenotype positive expression rate of BM-MSCs.

| Phenotype | BM-MSC | BM-MSCLSC |

|---|---|---|

| CD29 | 94.36±5.17 | 96.42±3.85 |

| CD31 | 2.86±0.69 | 2.14±1.02 |

| CD34 | 0.86±0.35 | 0.92±0.44 |

| CD44 | 80.30±5.10 | 89.07±6.50b |

| CD45 | 4.29±2.43 | 3.39±0.78 |

| CD73 | 95.21±5.99 | 94.32±3.45 |

| CD90 | 91.30±3.73 | 95.46±2.67 |

| CD105 | 67.14±5.52 | 62.20±7.80a |

P=0.00827

P=0.00208. n=12. BM-MSC, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells; LSCs, leukemia stem cells.

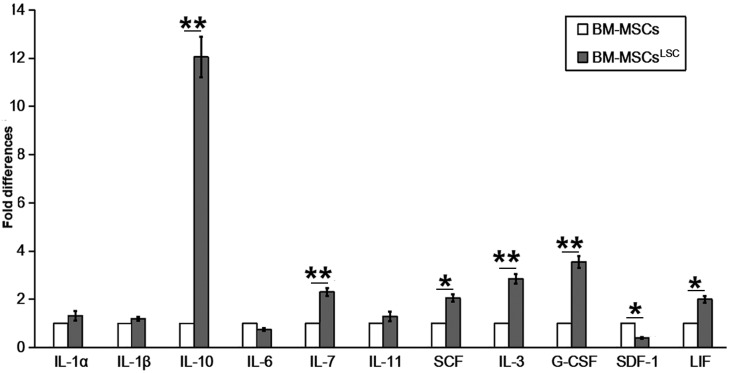

mRNA levels of hematopoietic factors were evaluated in BM-MSCs following co-culture with LSCs for 24–72 h. In contrast to SDF-1 and interleukin (IL)-6, which had reduced levels, the majority of hematopoietic factors, including IL-10, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), IL-3, IL-7,stem cell factor (SCF), IL-11, IL-1α, IL-1β and leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) showed increased expression in BM-MSCsLSC compared with BM-MSCs group (Fig. 1). The expression levels of IL-3, IL-7, IL-10 and G-CSF in BM-MSCsLSC group were significantly higher compared with BM-MSCs group (P<0.01). The results of SCF and LIF were also higher in the BM-MSCsLSC group (P<0.05). Collectively, these results suggest that the crosstalk of LSCs and BM-MSCs result in changes in the expression of hematopoietic factors in the BM microenvironment.

Figure 1.

Altered expression of hematopoietic related factors in BM-MSCsLSC. Although expression of SDF-1 and IL-6 mRNA was downregulated, the expression levels of the other hematopoietic factors (particularly IL-3, IL-7, IL-10 and G-CSF) were upregulated in BM-MSCsLSCs, compared with BM-MSCs. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. BM-MSCs, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells; LSC, leukemia stem cell; IL, interleukin; SCF, SKP1-CUL1-F protein; G-CSF, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor; LIF, leukemia inhibitory factor; SDF-1, stromal cell-derived factor 1.

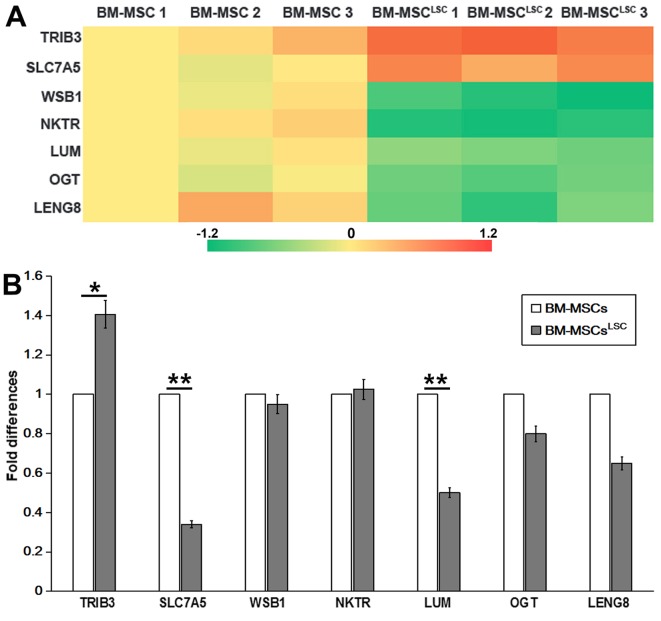

Differentially expressed genes in BM-MSCLSC

Illumina Genome Analyzer/Hiseq 2000 was performed to identify differentially expressed genes between BM-MSCsLSC and BM-MSCs. The data revealed significant upregulation of 2 genes [solute carrier family 7 member 5 (SLC7A5) and tribbles pseudokinase 3 (TRIB3)] and significant downregulation of 5 genes [WD repeat and SOCS box containing 1, natural killer cell triggering receptor (NKTR), LUM, O-linked N-acteylglucosamine (GlcNAc) transferase and leukocyte receptor cluster member 8 (LENG8)] in BM-MSCs after LSC simulation for 24–72 h (Table III). RT-qPCR analysis was performed to confirm the expression profiles obtained by RNA sequencing. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. As revealed in Fig. 2, TRIB3 and NKTR was upregulated, while SLC7A5, LUM and LENG8 were downregulated in BM-MSCsLSC compared with BM-MSCs group. The expression of TRIB3 in BM-MSCsLSC group were higher than that in BM-MSCs group (P<0.05). The expression levels of SLC7A5 and LUM in BM-MSCsLSC group were significantly lower than those in BM-MSCs group (P<0.01). Notably, the results of PCR revealed a decrease in SLC7A5, which was inconsistent with the results from RNA sequencing, therefore SLC7A5 was not chosen as the target for further experiments. The reduced expression levels of LUM were consistent with the results from the Illumina sequencing data. Therefore, LUM was selected for further experiments.

Table III.

Different expressed genes selected by deep sequencing technology.

| Associated gene name | Description | log2.fold-change | P-value | q value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRIB3 | Tribbles pseudokinase 3 | 0.87604 | 1.10×10−05 | 0.004136 |

| SLC7A5 | Solute carrier family 7 member 5 | 0.64000 | 1.32×10−05 | 0.004891 |

| WSB1 | WD repeat and SOCS box containing 1 | −1.04450 | 1.01×10−06 | 0.000490 |

| NKTR | Natural killer-tumor recognition sequence | −1.07880 | 4.57×10−05 | 0.014561 |

| LUM | Lumican | −0.63497 | 4.05×10−06 | 0.001739 |

| OGT | O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) transferase | −0.78956 | 1.47×10−05 | 0.005309 |

| LENG8 | Leukocyte receptor cluster member 8 | −0.84921 | 7.65×10−05 | 0.021334 |

SLC7A5, solute carrier family 7 member 5; TRIB3, tribbles pseudokinase 3; WSB1, WD repeat and SOCS box containing 1; NKTR, natural killer cell triggering receptor; LUM, lumican; OGT, O-linked N-acteylglucosamine (GlcNAc) transferase; LENG8, leukocyte receptor cluster member 8.

Figure 2.

Detection of differentially expressed genes as assessed by Illumina sequencing and RT-qPCR. (A) Heat map showing 7 differently expressed genes selected by Illumina sequencing data. (B) Differentially expressed genes in BM-MSCsLSCs, compared with that in BM-MSCs, were validated by RT-qPCR. The relative expression was normalized to BM-MSCs. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. BM-MSCs, bone marrow-mesenchymal stem cells; LSCs, leukemia stem cells; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; SLC7A5, solute carrier family 7 member 5; TRIB3, tribbles pseudokinase 3; WSB1, WD repeat and SOCS box containing 1; NKTR, natural killer cell triggering receptor; LUM, lumican; OGT, O-linked N-acteylglucosamine (GlcNAc) transferase; LENG8, leukocyte receptor cluster member 8.

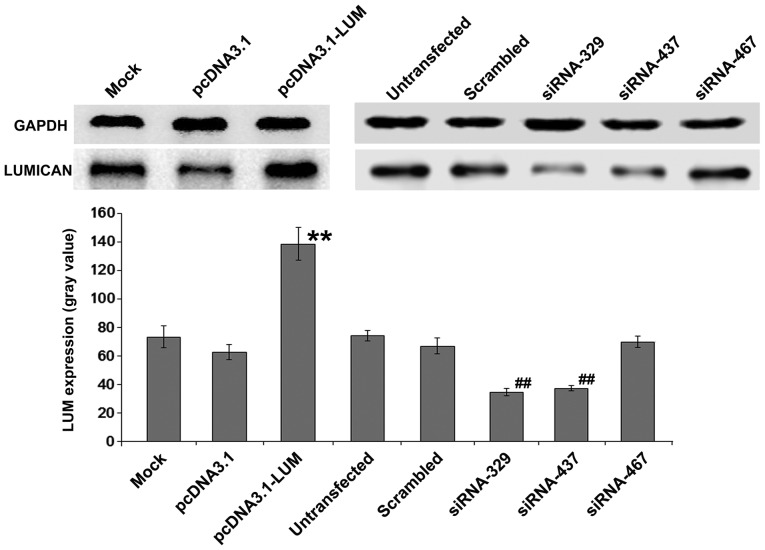

Up or downregulation of LUM in BM-MSCs

Whether changes in LUM expression of BM-MSCs could serve a critical a role in Nalm-6 cells was also evaluated. BM-MSCs were transfected with pcDNA3.1-LUM vector or siRNAs (siRNA329, siRNA437 and siRNA467). After colony selection for 2 weeks, expression of LUM in transfected BM-MSCs was confirmed by western blotting (Fig. 3). The results revealed that expression of LUM in LUM-transfected BM-MSCs (Lum) was >2-fold increase compared with that in mock and pcDNA3.1-transfected cells (P<0.01). By contrast, in siRNA329 and siRNA437-transfected BM-MSCs (siLUM), LUM mRNA transcripts were downregulated, compared with untransfected BM-MSCs and scrambled siRNA-transfected BM-MSCs (Fig. 3). siRNA329 and siRNA437 were utilized further to inhibit the expression of LUM. Transfection efficiency was ~43%.

Figure 3.

Western blot analysis of LUM expression. **P<0.01 vs. mock group; ##P<0.01 vs. untransfected group. LUM, lumican; siRNA, small interfering RNA.

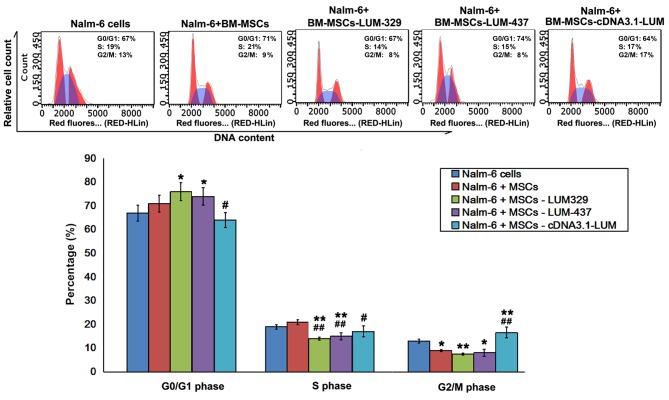

Effect of LUM downregulation on cell cycle distribution in Nalm-6 cells

Flow cytometry analysis revealed that the fraction of cells in G0/G1 phase increased, and the proportion of cells in G2/M phase decreased in Nalm-6 + BM-MSCs group compared with Nalm-6 cells group. Compared with Nalm-6 cells group, there was a significant increase in the percentage of cells in G0/G1 phase in the Nalm-6+BM-MSCs-LUM-329 and Nalm-6+BM-MSCs-LUM-437 (P<0.05) and a significant decrease in the S phase (P<0.01) and G2/M phase (P<0.01, 0.05). However, increasing LUM expression (Nalm-6+BM-MSCs-cDNA3.1-LUM group) decreased the percentage of cells in G0/G1 and S phase (both P<0.05), but increased the percentage of cells in G2/M phase compared with Nalm-6+BM-MSCs group (P<0.01; Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Effects of LUM on cell cycle distribution in Nalm-6 cells. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. Nalm-6 cells group; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 vs. Nalm-6+BM-MSCs group. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (n=6). BM-MSCs, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells; LUM, lumican.

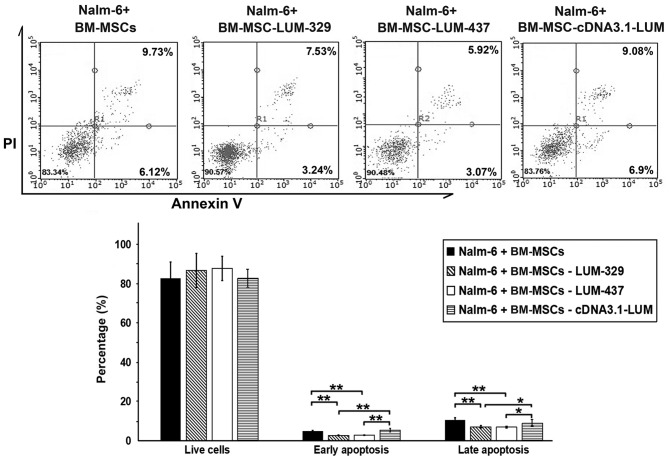

Downregulation of LUM decreases apoptosis in Nalm-6 cells

To determine whether LUM expression affects the apoptosis of Nalm-6 cells, the cells were stained with Annexin V/PI after 24 h of co-culture. The percentage of cells in both early and late apoptosis were significantly decreased in the LUM-silenced group (Nalm-6+BM-MSCs-LUM-329 and Nalm-6+BM-MSCs-LUM-437 group) compared with the Nalm-6+BM-MSCs group (P<0.01; Fig. 5). Compared with Nalm-6+BM-MSCs group, the numbers of apoptotic cells remained unchanged in Nalm-6+BM-MSCs-cDNA3.1-LUM group.

Figure 5.

Effects of LUM on apoptosis of Nalm-6 cells. Flow cytometry analysis results demonstrated that the proportion of total apoptotic cells decreased in the Nalm-6 cells of the BM-MSCs-LUM-329 and 437 groups compared with Nalm-6+BM-MSCs group. Compared with Nalm-6+BM-MSCs group, total apoptotic cells remained unchanged in BM-MSCs-cDNA3.1-LUM group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (n=6). BM-MSCs, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells; LUM, lumican; PI, propidium iodide.

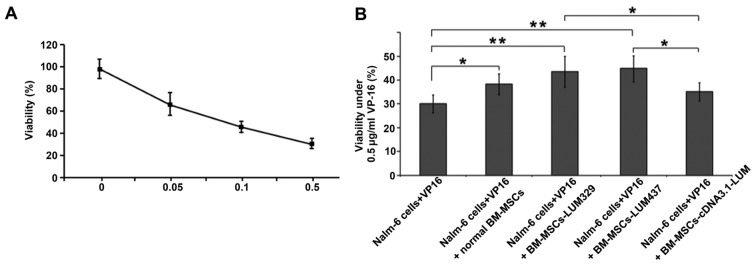

Downregulation of LUM decreases the sensitivity of Nalm-6 cells to VP-16

Whether changes in LUM expression may affect the sensitivity of Nalm-6 cells to VP-16, a chemotherapy medication used for the treatment of various types of cancer was also assessed. LUM-expressing BM-MSCs and LUM-silencing BM-MSCs were treated with VP-16 and CCK-8 was used to assess cytotoxicity. Treatment with VP-16 displayed cytotoxicity in BM-MSCs in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6A). Coculture with BM-MSCs (Nalm-6+VP16+normal BM-MSCs group) increased the cell viability compared with the Nalm-6 + VP16 group (P<0.05). Silencing of LUM (Nalm-6+BM-MSCs-LUM-329 and Nalm-6+BM-MSCs-LUM-437 group) also increased the cell viability compared with the Nalm-6 + VP16 group (P<0.01). In contrast, Nalm-6+BM-MSCs-cDNA3.1-LUM group reduced the cell viability compared with Nalm-6 + VP16 + normal BM-MSCs group, but this effect was not significant (P>0.05; Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Effects of LUM on the sensitivity of Nalm-6 cells to VP-16. (A) Single VP-16 treatment induced cytotoxicity in a dose-dependent manner (0, 0.05, 0.1 and 0.5 µg/ml). (B) The viability of Nalm-6 cells co-cultured with normal BM-MSCs, BM-MSCs-LUM-329, BM-MSCs-LUM-437 or BM-MSCs-cDNA3.1-LUM was determined by Cell Counting Kit-8. Downregulation of LUM expression (Nalm-6+BM-MSCs-LUM-329 and Nalm-6+BM-MSCs-LUM-437 group) increased the cell viability compared with the Nalm-6 + VP16 group. In contrast, Nalm-6+BM-MSCs-cDNA3.1-LUM group reduced the cell viability compared with Nalm-6 + VP16 + normal BM-MSCs group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (n=6 experiments). BM-MSCs, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells; LUM, lumican.

Discussion

In the present study, it was demonstrated that Nalm-6 cell derived CD34+ LSCs significantly upregulated CD44 expression and altered the expression of different hematopoietic factors in BM-MSCs following co-culture. LUM was downregulated in BM-MSCsLSC as assessed by Illumina Genome Analyzer/Hiseq 2000 and RT-qPCR. In addition, a recombinant eukaryotic expression plasmid or siRNA were used to overexpress or inhibit the expression of the lumican gene. The results suggest that downregulated LUM expression in BM-MSCs contribute to the anti-apoptotic properties and resistance to chemotherapy in Nalm-6 cells.

CD44 is a widely distributed cell-surface glycoprotein involved in lymphocyte adhesion to the vascular endothelium and extracellular matrix proteins (13). As a major receptor of hyaluronic acid (HA) (14), CD44 participates in diverse cellular processes during tumorigenesis, including cell transformation, proliferation, metastasis and apoptosis (5,15,16). CD44 is required for LSCs to efficiently lodge in and home to the BM niche in AML, and anti-CD44 antibodies may modify the fate of the LSCs via inducing differentiation (6). In addition, CD44-HA crosstalk mediates LSC apoptosis resistance by initiating signal transductions and cooperating with multidrug resistance genes (17). The results of the present study demonstrated that CD44 expression of BM-MSCs was significantly increased after LSC simulation. Therefore, LSCs may induce MSCs to express increased levels of CD44. This results in LSCs staying closer to MSCs for longer periods of time, thus additional shelter from stromal cells. On the other hand, it can create a microenvironment promoting the proliferation of LSCs and prevent the damage caused by chemotherapeutic drugs, thus contributing to relapse of ALL.

An intricate network of cytokine and cytokine receptors is involved in the crosstalk between LSCs and BM-MSCs, which may deregulate normal hematopoiesis and offer a selective growth advantage to LSCs in leukemia. SDF-1/CXCL12, is critical for the homing of hematopoietic cells to the BM through its receptor, CXCLR4 (18). Specific antagonists, which may block the interaction between CXCL12 and CXCR4, may disrupt the adhesion of malignant cells to the BM microenvironment and adipose tissue, rendering them more susceptible to chemotherapy (19). Due to the effects of SDF-1 on the pathophysiological procedure of leukemia, it was hypothesized that SDF-1 mRNA may be upregulated in BM-MSCs following co-culture with LSCs. Unexpectedly, it was found that SDF-1 mRNA was downregulated in BM-MSCs after LSC simulation. A previous study found that CXCL12 expression in BM-MSCs was reduced in BCR-ABL mice and CML patients (20). Maksym et al (21) reported that CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling was deregulated in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes and leukemia. Hematopoietic factors, including IL-10, IL-1α and IL-7 may promote progression of lymphoid malignancies and may be associated with clinical prognosis. Excessive production of SCF impairs normal BM niches and mediates the engraftment of CD34+ cells into the malignant niche. The SCF/c-kit-R pathway may be utilized as a therapeutic target for leukemia (22). These findings are consistent with the results of the present study. In accordance with previous studies (23–28), the results of the present study demonstrated reduced SDF-1 and IL-6 levels, and increased IL-10, G-CSF, IL-3, IL-7, SCF, IL-11, IL-1α, IL-1β and LIF levels after LSC-BM-MSCs co-culture for 24–72 h.

LUM is a member of the small leucine-rich proteoglycan family (29) and its overexpression has been reported in melanoma (30), breast (31), colorectal (32), uterine (33) and pancreatic cancer (34). In melanoma, decreased LUM expression correlates with increased tumor growth and progression (35,36), and increased LUM expression impedes tumor cell migration and invasion by directly interacting with the α2β1 integrin (37) and decreasing phosphorylated focal adhesion kinase phosphorylation (38). A previous study unambiguously linked LUM with pancreatic carcinoma cell metabolism and identified the LUM/epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)/Akt/hypoxia-inducible factor-1 α (HIF-1α) signaling pathway as a mechanism by which LUM may inhibit pancreatic cancer cell survival and proliferation (39). LUM enhances the internalization of EGFR from the cell membrane into the cytoplasm, resulting in autophosphorylation and subsequent internalization (40). The PI3K/Akt-mediated signaling pathway is a major downstream pathway of EGFR (41). LUM downregulates HIF-1α expression and activity through the EGFR/Akt signaling pathway. LUM may decrease glucose consumption, lactate production and intracellular ATP level and induce apoptosis through downregulation of HIF-1α (25). Using the Illumina Genome Analyzer/Hiseq 2000, it was identified that the expression of LUM was decreased in BM-MSCsLSC. Additionally; decreased LUM expression led to decreased apoptosis and promoted chemoresistance to VP-16 in Nalm-6 cells, indicating that LSCs can alter the expression of key genes of BM-MSCs to promote leukemia survival. Decreased expression of LUM may also promote angiogenesis by interfering with α2β1 integrin and downregulating matrix metalloproteinase-14 expression (42). It is worth noting that only depletion for LUM in BM-MSCs significantly affected the cell cycle, apoptosis and drug resistance to Nalm-6, while overexpression of LUM did not show a significant effect compared with the blank control group. This may be due to the fact that the corresponding receptors on LSC have not increased accordingly.

In summary, the present study revealed that ALL cells may generate an abnormal inhibitory microenvironment for normal hematopoietic cells. Downregulation of LUM in BM-MSCs decreased apoptosis in Nalm-6 cells and the sensitivity of Nalm-6 cells to VP-16. However, the mechanism by which LUM interacts with other factors during the occurrence and development of leukemia remains unclear. These potential interactions should be further investigated in future studies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81473484), The Shenzhen Science and Technology Research and Development Fund (grant no. JCYJ20160331173652555) and The Shandong Province Major Scientific Research Projects (grant no. 2017GSF218015).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

RW and DL conceptualized the study and designed the protocol. DL performed the literature search. LL and QS performed the experiments. All authors analyzed and interpreted the data. ZY performed the experiments and drafted the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Silverman LB, Gelber RD, Dalton VK, Asselin BL, Barr RD, Clavell LA, Hurwitz CA, Moghrabi A, Samson Y, Schorin MA, et al. Improved outcome for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Results of Dana-Farber consortium protocol 91-01. Blood. 2001;97:1211–1218. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.5.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conter V, Aricó M, Valsecchi MG, Rizzari C, Testi A, Miniero R, Di Tullio MT, Lo Nigro L, Pession A, Rondelli R, et al. Intensive BFM chemotherapy for childhood ALL: Interim analysis of the AIEOP-ALL 91 study. Associazione Italiana Ematologia Oncologia Pediatrica. Haematologica. 1998;83:791–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaynon PS, Steinherz PG, Bleyer WA, Ablin AR, Albo VC, Finklestein JZ, Grossman NJ, Novak LJ, Pyesmany AF, Reaman GH, et al. Improved therapy for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and unfavorable presenting features: A follow-up report of the Childrens cancer group study CCG-106. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:2234–2242. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.11.2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arico M, Valsecchi MG, Conter V, Rizzari C, Pession A, Messina C, Barisone E, Poggi V, De Rossi G, Locatelli F, et al. Improved out-come in high-risk childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia defined by prednisone-poor response treated with double Berlin-Frankfurt-Muenster protocol II. Blood. 2002;100:420–426. doi: 10.1182/blood.V100.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin YH, Yang-Yen HF. The osteopontin-CD44 survival signal involves activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:46024–46030. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105132200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dick JE, Bhatia M, Gan O, Kapp U, Wang JC. Assay of human stem cells by repopulation of NOD/SCID mice. Stem Cells. 1997;15(Suppl 1):S199–S207. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530150826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiseman DH. Donor cell leukemia: A review. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:771–789. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juarez J, Bradstock KF, Gottlieb DJ, Bendall LJ. Effects of inhibitors of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 on acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells in vitro. Leukemia. 2003;17:1294–1300. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang Z, Wu D, Lin S, Li P. CD34 and CD38 are prognostic biomarkers for acute B lymphoblastic leukemia. Biomark Res. 2016;4:23. doi: 10.1186/s40364-016-0080-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCarthy DJ, Chen Y, Smyth GK. Differential expression analysis of multifactor RNA-Seq experiments with respect to biological variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:4288–4297. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, Feng Z, Wang X, Wang X, Zhang X. DEGseq: An R package for identifying differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:136–138. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisterer W, Bechter O, Hilbe W, van Driel M, Lokhorst HM, Thaler J, Bloem AC, Günthert U, Stauder R. CD44 isoforms are differentially regulated in plasma cell dyscrasias and CD44v9 represents a new independent prognostic parameter in multiple myeloma. Leuk Res. 2001;25:1051–1057. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2126(01)00075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niitsu N, Iijima K. High serum soluble CD44 is correlated with a poor outcome of aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Leuk Res. 2002;26:241–248. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2126(01)00122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aruffo A, Stamenkovic I, Melnick M, Underhill CB, Seed B. CD44 is the principal cell surface receptor for hyaluronate. Cell. 1990;61:1303–1313. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90694-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bourguignon LY, Zhu H, Shao L, Zhu D, Chen YW. Rho-kinase (ROK) promotes CD44v3, 8–10-ankyrin interaction and tumor cell migration in metastatic breast cancer cells. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1999;43:269–287. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1999)43:4<269::AID-CM1>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khaldoyanidi SK, Goncharova V, Mueller B, Schraufstatter IU. Hyaluronan in the healthy and malignant hematopoietic microenvironment. Adv Cancer Res. 2014;123:149–189. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800092-2.00006-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuhn NZ, Tuan RS. Regulation of stemness and stem cell niche of mesenchy-mal stem cells: Implications in tumorigenesis and metastasis. J Cell Physiol. 2010;222:268–277. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Rhenen A, Moshaver B, Kelder A, Feller N, Nieuwint AW, Zweegman S, Ossenkoppele GJ, Schuurhuis GJ. Aberrant marker expression patterns on the CD34+CD38-stem cell compartment in acute myeloid leukemia allows to distinguish the malignant from the normal stem cell compartment both at diagnosis and in remission. Leukemia. 2007;21:1700–1707. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang B, Ho YW, Huang Q, Maeda T, Lin A, Lee SU, Hair A, Holyoake TL, Huettner C, Bhatia R. Altered microenvironmental regulation of leukemic and normal stem cells in chronic myelogenous leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:577–592. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maksym RB, Tarnowski M, Grymula K, Tarnowska J, Wysoczynski M, Liu R, Czerny B, Ratajczak J, Kucia M, Ratajczak MZ. The role of stromal-derived factor-1-CXCR7 axis in development and cancer. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;625:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.04.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsiftsoglou AS, Bonovolias ID, Tsiftsoglou SA. Multilevel targeting of hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal, differentiation and apoptosis for leukemia therapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;122:264–280. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fouillard L, Francois S, Bouchet S, Bensidhoum M, Elm'selmi A, Chapel A. Innovative cell therapy in the treatment of serious adverse events related to both chemo-radiotherapy protocol and acute myeloid leukemia syndrome: The infusion of mesenchymal stem cells post-treatment reduces hematopoietic toxicity and promotes hematopoietic reconstitution. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2013;14:842–848. doi: 10.2174/1389201014666131227120222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lapalombella R. Interleukin-6 in CLL: Accelerator or brake? Blood. 2015;126:697–698. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-06-650804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jafarzadeh N, Safari Z, Pornour M, Amirizadeh N, Forouzandeh Moghadam M, Sadeghizadeh M. Alteration of cellular and immune-related properties of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and macrophages by K562 chronic myeloid leukemia cell derived exosomes. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:3697–3710. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang X, Tu H, Yang Y, Wan Q, Fang L, Wu Q, Li J. High IL-7 levels in the bone marrow microenvironment mediate imatinib resistance and predict disease progression in chronic myeloid leukemia. Int J Hematol. 2016;104:358–367. doi: 10.1007/s12185-016-2028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Supper E, Tahir S, Imai T, Inoue J, Minato N. Modification of gene expression, proliferation, and function of OP9 Stroma cells by Bcr-Abl-expressing leukemia cells. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0134026. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wetzler M, Talpaz M, Lowe DG, Baiocchi G, Gutterman JU, Kurzrock R. Constitutive expression of leukemia inhibitory factor RNA by human bone marrow stromal cells and modulation by IL-1, TNF-alpha, and TGF-beta. Exp Hematol. 1991;19:347–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chakravarti S, Stallings RL, Sundarraj N, Cornuet PK, Hassell JR. Primary structure of human lumican (Keratan Sulfate Proteoglycan) and localization of the gene (LUM) to chromosome 12q21.3-q22. Genomics. 1995;27:481–488. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeanne A, Untereiner V, Perreau C, Proult I, Gobinet C, Boulagnon-Rombi C, Terryn C, Martiny L, Brézillon S, Dedieu S. Lumican delays melanoma growth in mice and drives tumor molecular assembly as well as response to matrix-targeted TAX2 therapeutic peptide. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7700. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07043-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karamanou K, Franchi M, Piperigkou Z, Perreau C, Maquart FX, Vynios DH, Brézillon S. Lumican effectively regulates the estrogen receptors-associated functional properties of breast cancer cells, expression of matrix effectors and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Sci Rep. 2017;7:45138. doi: 10.1038/srep45138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Wit M, Carvalho B, Delis-van Diemen PM, van Alphen C, Beliën JAM, Meijer GA, Fijneman RJA. Lumican and versican protein expression are associated with colorectal adenoma-to-carcinoma progression. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174768. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naito Z, Ishiwata T, Kurban G, Teduka K, Kawamoto Y, Kawahara K, Sugisaki Y. Expression and accumulation of lumican protein in uterine cervical cancer cells at the periphery of cancer nests. Int J Oncol. 2002;20:943–948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li X, Kang Y, Roife D, Lee Y, Pratt M, Perez MR, Dai B, Koay EJ, Fleming JB. Prolonged exposure to extracellular lumican restrains pancreatic adenocarcinoma growth. Oncogene. 2017;36:5432–5438. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brézillon S, Venteo L, Ramont L, D'Onofrio MF, Perreau C, Pluot M, Maquart FX, Wegrowski Y. Expression of lumican, a small leucine-rich proteoglycan with antitumour activity, in human malignant melanoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:405–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2007.02437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vuillermoz B, Khoruzhenko A, D'Onofrio MF, Ramont L, Venteo L, Perreau C, Antonicelli F, Maquart FX, Wegrowski Y. The small leucine-rich proteoglycan lumican inhibits melanoma progression. Exp Cell Res. 2004;296:294–306. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zéltz C, Brézillon S, Käpylä J, Eble JA, Bobichon H, Terryn C, Perreau C, Franz CM, Heino J, Maquart FX, Wegrowski Y. Lumican inhibits cell migration through α2β1 integrin. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:2922–2931. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brézillon S, Radwanska A, Zeltz C, Malkowski A, Ploton D, Bobichon H, Perreau C, Malicka-Blaszkiewicz M, Maquart FX, Wegrowski Y. Lumican core protein inhibits melanoma cell migration via alterations of focal adhesion complexes. Cancer Lett. 2009;283:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li X, Truty MA, Kang Y, Chopin-Laly X, Zhang R, Roife D, Chatterjee D, Lin E, Thomas RM, Wang H, et al. Extracellular lumican inhibits pancreatic cancer cell growth and is associated with prolonged survival after surgery. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:6529–6540. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Q, Villeneuve G, Wang Z. Control of epidermal growth factor receptor endocytosis by receptor dimerization, rather than receptor kinase activation. EMBO Rep. 2005;6:942–948. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Balakrishnan S, Mukherjee S, Das S, Bhat FA, Raja Singh P, Patra CR, Arunakaran J. Gold nanoparticles-conjugated quercetin induces apoptosis via inhibition of EGFR/PI3K/Akt-mediated pathway in breast cancer cell lines (MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231) Cell Biochem Funct. 2017;35:217–231. doi: 10.1002/cbf.3266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Niewiarowska J, Brézillon S, Sacewicz-Hofman I, Bednarek R, Maquart FX, Malinowski M, Wiktorska M, Wegrowski Y, Cierniewski CS. Lumican inhibits angiogenesis by interfering with α2β1 receptor activity and downregulating MMP-14 expression. Thromb Res. 2011;128:452–457. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.