Abstract

Introduction:

Healthy food incentives matching Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits spent on fruits and vegetables subsidize increased produce consumption among low-income individuals at risk of food insecurity and diet-related disease. Yet many eligible participants do not use these incentives, in part due to limited awareness. This study examined the acceptability and impact of a primary care-based informational intervention on facilitators and barriers to use of the statewide SNAP incentive program Double Up Food Bucks (DUFB).

Methods:

Focus groups (n=5) were conducted April-June 2015 among a purposive sample (n=26) of SNAP-enrolled adults from a Michigan health clinic serving low-income patients. All had participated in a waiting room-based informational intervention about DUFB; none had used DUFB before the intervention. Groups were stratified by DUFB use/non-use during the 6-month intervention period. Results were analyzed in 2016-2017 through an iterative content analysis process.

Results:

Participants reported the waiting room intervention was acceptable and a key facilitator of first-time DUFB use. Motivators for DUFB use included: 1) eating more healthfully; 2) stretching SNAP benefits; 3) higher-quality produce at markets; and 4) unique market environments. Remaining barriers included: 1) lack of transportation; 2) limited market locations/hours; and 3) persistent confusion regarding incentive use among a small number of participants.

Discussion:

Low-income patients who utilized an informational intervention about DUFB reported numerous benefits from participation. Yet logistical barriers remained for a subset of patients. Improving geographical accessibility and ease of SNAP incentive redemption may further improve dietary quality and food security among vulnerable populations.

Introduction

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) healthy food incentives matching SNAP funds spent on fruits and vegetables (FV) can help reduce cost-related barriers to food access. Studies demonstrate that incentives increase FV purchase and consumption in low-income communities,1-7 and suggest that incentive adoption nationally would lead to long-term reductions in diet-related disease.8,9 One SNAP incentive, Double Up Food Bucks (DUFB), is currently accepted at >250 farmers markets (FM) and grocery stores across Michigan and is available in >23 states.

Lack of awareness and understanding limit use of DUFB and other SNAP incentives.1,5,6,10-12 To address these barriers, a longitudinal, mixed methods, quasi-experimental trial was conducted evaluating a waiting room-based intervention promoting DUFB use among low-income primary care patients. The qualitative portion, reported here, examined participants’ motivations for using DUFB; facilitators/barriers to DUFB use; and intervention acceptability.

Methods

Study Sample and Design

Methods for the quantitative phase are described elsewhere.5 Briefly, 177 SNAP-enrolled adults recruited from a primary care clinic serving a low-income, racially/ethnically diverse population were enrolled in a waiting room-based informational intervention encouraging DUFB use at local FM.a DUFB use and FV consumption were measured through 4 surveys (August 2014-January 2015). The intervention was associated with an almost 4-fold increase in DUFB use and significant increases in FV consumption.5

Using an explanatory sequential mixed methods design,13 focus groups were conducted using phenomenal variation sampling14,15 to further explore quantitative results. Participants sampled had not previously used DUFB, and over the study period either never used DUFB, used DUFB once, or used DUFB multiple times. Written informed consent was provided. This study was approved by the University of Michigan Medical School IRB (HUM00076630).

Focus groups were conducted at the intervention site; childcare was provided. Quantitative phase findings informed development of the semi-structured focus group guide, which was revised after piloting. Questions pertained to food shopping practices, barriers/facilitators to buying FV, perceptions regarding the intervention, and DUFB experiences.

Data collection

Participants were stratified into focus groups based on self-reported frequency of DUFB use (never, once, or multiple times). Sociodemographic characteristics and pre-intervention FM and DUFB use were obtained during the quantitative phase.

Focus groups were conducted April-June 2015 by 1 of 2 experienced moderators who lived and/or worked in the community. A member of the study team (AJC) assisted and took notes at all groups. Groups were conducted in English, took 60-75 minutes, and were audio recorded. Healthful snacks were provided, and participants were compensated $25. Following each group, study team members debriefed about questions meriting revision and topics warranting further exploration in future groups.

Data Analysis

Recordings were transcribed verbatim and deidentified. Using Dedoose version 7.0.23, transcripts were analyzed using conventional content analysis.16 All transcripts were read by 2 study members (AJC, KEO), and major patterns within and across focus groups identified. After independently coding each transcript, codes were compared and discrepancies discussed until consensus was reached. Using an iterative process, codes were clustered under categories, and categories incorporated into more abstract themes.

Results

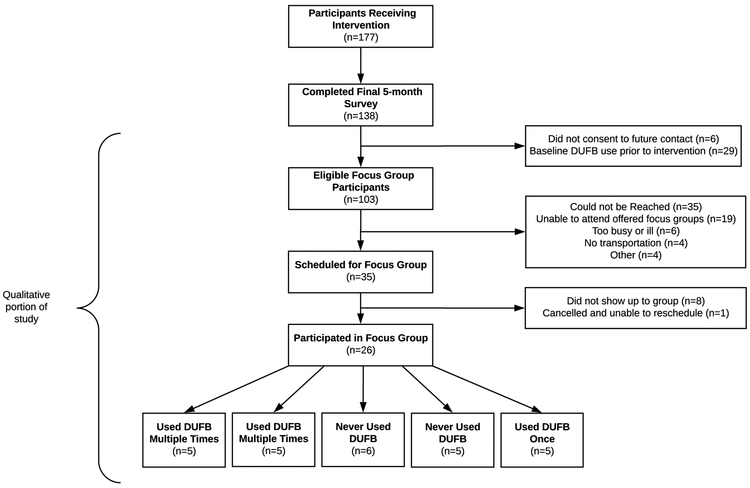

Study flow and participant characteristics are reported in Figure 1 and Table 1, respectively. Table 2 highlights participants’ perceptions of the intervention, facilitators of and motivations for using DUFB, and barriers to DUFB use.

Figure 1:

Study Flow Diagram

Table 1:

Pre-Intervention Baseline Self-Reported Characteristics of Focus Group Participants

| Characteristics | Focus Group Participants (n=26) |

|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 20(77) |

| Relationship to patient, n (%) | |

| Self | 17 (65) |

| Family member | 7 (27) |

| Other | 2 (8) |

| Age, median (IQR) | 45.5 (33-52) |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 17 (65) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 7 (27) |

| Other | 3 (12) |

| Marital Status, n (%) | |

| Single/divorced/separated/widowed | 22 (85) |

| Married/partnered | 4 (15) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| < 12 | 4 (15) |

| HS graduate/GED | 8 (31) |

| Some college | 13 (50) |

| College degree | 1 (4) |

| Employment, n (%)a | |

| Working for pay | 4 (15) |

| Unemployed | 5 (19) |

| Disabled | 13 (50) |

| Retired/homemaker/student | 5 (19) |

| ≥ 1 Children in household, n (%) | 11 (42) |

| Annual Income < $25,000, n (%) | 13 (50) |

| Federal Food Assistance, n (%)a | |

| SNAP | 26 (100) |

| WIC | 5 (19) |

| Worried about having enough money to buy food in the past year, n (%) | |

| Always or usually | 8 (31) |

| Sometimes | 12 (46) |

| Daily servings of fruit and vegetables, mean (SD) | 3.46 (1.75) |

| Shopped at a farmers market in the past year, n (%) | 22 (85) |

| Self health assessment fair or poor, n (%) | 13 (50) |

| ≥1 household member with following health conditions, n (%)a | |

| Diabetes | 8 (31) |

| Hypertension | 17 (66) |

| High cholesterol | 6 (23) |

| Obesity | 16 (62) |

Totals sum to >100% because of option to check more than one category GED, General Educational Development test; HS, high school; IQR, interquartile range; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

Table 2:

Perceptions of the Waiting Room Intervention and Facilitators, Motivators, and Barriers to Use of Double Up Food Bucks (DUFB) at the Farmers Market Following the Intervention, by Participant Self-reported DUFB Use

| Themes | Supporting Quotes |

|---|---|

| Perceptions of clinic waiting room as setting for intervention | |

| Location Effective and Well Received, but Many Surprised | “I think this was an ideal place. I mean people are usually thinking about their health when they come to a clinic.”Female, Multiple Uses “It was nice, something to do while you were waiting for the doctor.” Female, Single Use “It was kind of a smart strategy because you catch people and there’s always people in the waiting room…it was just kind of unexpected to hear about food at the hospital” Male, Single Use “A little unexpected hearing [about DUFB] where we heard it from but it was very helpful and very appreciated” Male, Never Used “I liked [the intervention] a lot…once I got going with [DUFB], I found it to be very helpful…I think it [providing information about DUFB] should continue…because I don’t think as many people know about [DUFB] as they should…I think if a lot more people knew about it a lot more people would be interested in the program.” Female, Single Use |

| Facilitators and Motivators for using DUFB at the Farmers Market | |

| Increased DUFB Awareness | |

| First learned about DUFB from the intervention | “[The intervention] was helpful because I wouldn’t have been in the [DUFB] program if I wasn’t in the doctor’s office that day.” Female, Multiple Uses “[The intervention] told us how [DUFB] would work at the FM. [Study staff] gave me a list of different sites where the FM were.” Female, Never Used |

| DUFB awareness facilitated first FM use | “I never went to the FM before [DUFB]…This actual piece here [DUFB] calls me to go to the FM…I mean I’ve seen them down there…but yeah, I hadn’t patronized prior to finding out about this program.” Female, Multiple Uses “If it wasn’t for [DUFB], I wouldn’t have took that chance of going to the FM…I passed by it a thousand times and never stopped. But when the program offered some help, you know, some Double Up…It got me sold“ Male, Single Use |

| Health Imperative | |

| Drive to eat better due to preexisting health condition | “I’m a diabetic so I can’t just eat prepackaged foods all the time. I got to make something that’s right because I was a bad diabetic and I had a lot of problems with my feet and they told me if I don’t get my act together, they were starting to pull out the hacksaw so I’m a little more serious about getting the right food.” Male, Never Used “I’ve never been as conscious until my health took a turn and I had to really be conscious as to [eat healthy]. I had to…I [used to] buy frozen and canned FV because everything got so instant in our house.” Female, Multiple Uses “[Eating healthier is] a high priority because like I mentioned, I'm a diabetic, so is my son, so we into counting the carbs.” Male, Single Use |

| Want to eat better to maintain health | “[I]t’s really a top priority for me in terms of acquiring FV because it does make me feel good. It rejuvenates my body.” Female, Never Used “I'm starting to try to buy more FV now than I used to because I haven’t been eating enough of them so I'm starting to buy more now to try to eat healthier—and lose weight.” Male, Single Use “I appreciate the Double Up program because it helped me change my eating habits…the Double Up program helped me find more FV to eat healthier and I started…juicing it and I loved it and I’ve stuck with it now. I eat all FV where I wouldn’t eat it before.” Male, Single Use |

| Desire to care for future generations | “[Buying FV is a] high priority for me. I’m a grand-daddy for the first time and my grandbaby, he just turned one. He eats all his FV because we provide that for him…And I'm looking out for him too. And I'm glad. I’m blessed I got him. He make me eat right to be here a little longer.” Male, Single Use |

| Financial Benefit | |

| DUFB financial incentive motivated FM use | “That was the first time I went to the FM and I think the reason for me going was [DUFB] offered me some benefits…if I spend an amount of money.” Male, Single Use “I never would have went to [the FM] if it hadn’t been for this program [DUFB].” Female, Multiple Uses |

| DUFB helped alleviate financial strain | “I felt like I hit the lottery when I started [using DUFB].” Female, Multiple Uses “When I went to the FM [and used DUFB I was able to] buy more fruits and vegetables. The grocery stores, sometimes they are more expensive and sometimes their vegetables ain’t as good.” Male, Single Use “[DUFB enables me] to go get what I need when I need it.” Female, Multiple Uses |

| Used DUFB to buy more produce and try new foods | “My food stamps got cut so [DUFB] actually came in handy getting double the food for the price…I try to keep the FV [in my diet] so that pretty much helped a lot because I was able to get more for less. That was a big help.” Female, Multiple Uses “I eat salads and stuff and a couple years ago I didn’t do that so it changed me. Like I said, it started with the Double Up because I got more food for my buck and it was healthy food.” Male, Single Use “Sometimes [the FM has] something unusual and it makes me more likely to want to try it because [DUFB] is an incentive to buy something new.” Male, Multiple Uses |

| DUFB helped stretch existing SNAP benefits | “I was basically being paid to go [to the FM]…I just went there hoping I could find some things I would normally pay [for] out of pocket in the grocery store…and use my money for something else, hold on to it as long as I can and pay for bills and other food.” Female, Multiple Uses “[DUFB] was like the money I didn’t have to spend on FV and then I could spend [more of my SNAP benefits] on breads or more meat or more important food that we need for the household. Not to say the FV aren’t [important] but you tend to, you want to make sure your family can eat a meal overall rather than just fruits and stuff. So that kind of opened up that window to be able to use [DUFB] on fruits…and then still get what you need as far as household stuff.That was a really big deal.” Female, Multiple Uses |

| Higher Quality Produce | |

| FM produce fresher and lasted longer | “A lot of products sits on the shelf at the [grocery] store and [FM produce] probably just been picked maybe out the garden 3-4 days before it got there. You can’t beat that. And it’s better tasting. You can tell the difference between something that’s fresh and something that ain’t too fresh.” Female, Multiple Uses “Some of the grocery stores that I go to, some of the produce is just not good, you know. You think you get fresh, but it’s old! I open up things and it’s rotten and different things where I had better quality with the FM, its usually fresh food at the market.” Female, Single Use “The FV lasted longer in the fridge when I got them from the FM.” Female, Single Use |

| Preferred organic produce more readily found at FM | “One of the reasons I go [to the FM] is for fresher FV and maybe not with pesticides or GMO seeds.” Male, Multiple Uses “Just comparing [the grocery store] with the FM… [the] FM is untouchable to me…I mean everything is fresh, organically grown and it’s local.” Male, Single Use |

| Enjoyed FM Shopping Experience | |

| Relationships with Farmers | “We talk to the farmers and ask them, ‘How do you cook this at home? What do we do with this?’ We ask other people out there, ‘What can we do with this?’” Female, Multiple Uses “[The farmers] are very friendly…they seem very willing to give you a great deal and they are very friendly with you.” Female, Used Once [You can] talk to the [farmers] about where [their FV] came from and they can tell you what’s in and what’s not and you can decide. Female, Used Once |

| Social Environment | “It’s very exciting to know what the farmer’s do there. The activities they have for the kids, sometimes they have hay rides and all that stuff. You know, it makes it welcoming for people there. How they grow their crops, how they harvest produce and all that stuff.” Female, Used Once “Sometimes they have…music serenading you [and it] make[s] it so much [more] pleasant.” Female, Used Once |

| Barriers to using DUFB at the Farmers Market | |

| Unforeseen Complexity of DUFB | |

| Confusion related to first-time use | “I didn’t know exactly [how to use DUFB at the FM]—and I’m trying to—[my family is] asking me questions and I’m not exactly sure. I just said I know you got to get some coins or something like that and they are like, no, they don’t have coins and all this and they are looking at me stupid and I’m looking stupid so—until you go through the process, you really don’t know.” Male, Multiple Uses “I think once you go through the process, you understand better but just like anything else, until you do it, you are not clear on everything.” Male, Single Use |

| Study inadvertently introduced confusion for some | “I haven’t used [DUFB] because to be honest with you, every time I went to the FM, I actually left my [study voucher] at the house.” Female, Never Used “Even when I was using [DUFB], I still didn’t know that it was available to as many people as it was. I thought it was only available for people that talked to the person upstairs…I thought I only got in it because I was happened to be at the clinic when they happened to be there. Female, Multiple Uses |

| Lack of Transportation and Limited Farmers Market Hours | “The biggest barrier is the hours, the days [of the FM]. Sometimes when I have a ride they are not open and they won’t be open.” Female, Single Use “I feel like it would be more convenient if they would put [FM] closer to a local grocery store where everybody is shopping anyway. So that way, it won’t be a problem with the transportation, you know, or finding them.” Female, Never Used |

| Limited Variety | “[The FM need] more varieties like what the stores have. Some days you’ll come and they’ll have certain things. Some days they won’t.” Male, Multiple Uses |

| Concerns for Food Waste | “I notice now that I don’t buy…fresh vegetables, I go to [the grocery store] and I buy frozen, cut-up mixed vegetables and that lasts a lot longer.” Female, Never Used |

DUFB, Double Up Food Bucks; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; FVs, Fruits and vegetables; FM, Farmers markets

Reported facilitators, motivators, and barriers to DUFB use were generally similar across focus group strata—differences primarily related to whether participants overcame barriers encountered. Although many were initially surprised to discuss FV in a health clinic, participants across groups found the waiting room an acceptable and effective setting for the intervention, with several stating they wanted provision of DUFB information to continue beyond the study period. Participants consistently expressed increased awareness and understanding of DUFB, with many motivated to visit a FM for the first time because of the incentive.

The desire to eat more healthfully was a key theme across focus groups irrespective of DUFB use. Participants spoke with urgency about managing diet-related diseases, and FV were a priority in food purchasing decisions. The opportunity to double SNAP dollars strongly motivated DUFB use, and participants used the incentive both to increase the amount of produce purchased and to stretch existing SNAP benefits for other necessities.

Participants using DUFB consistently reported FM had higher quality FV than other retailers and appreciated the opportunity to build relationships with farmers. They reported trusting farmers to honestly discuss growing practices and that some farmers gave them additional deals. A social, family-friendly environment further motivated return visits.

Although participants across focus groups felt DUFB appeared straightforward during the intervention, several reported that DUFB redemption was unexpectedly complicated at the first FM visit. Common sources of confusion included where to redeem SNAP benefits/obtain DUFB coins and distinguishing among various FM incentives. While most participants were able to navigate these barriers, others were not. The intervention inadvertently introduced confusion for a small number of participants; some mistakenly thought DUFB was limited to study participants or that the study-specific voucher was DUFB.

While the intervention targeted informational barriers to DUFB use, some participants also cited sometimes insurmountable difficulties with transportation and inconvenient FM hours/locations. Some participants were frustrated by seasonal limitations of FM produce and that FM lacked the one-stop shopping efficiency of grocery stores with larger, more predictable inventory. A few participants were concerned about FV spoilage and food waste.

Discussion

A brief waiting room-based informational intervention among SNAP-enrolled patients—associated with significant increases in incentive use and FV consumption5—was broadly acceptable and improved program awareness and understanding. Reducing the risk or progression of diet-related disease was a key motivator for using DUFB. Consistent with prior work, additional drivers of FM incentive use included the ability to stretch SNAP benefits,17-19 the perception of higher-quality produce,17,18,20 and the unique FM environment.17-20 While the intervention largely addressed informational barriers to DUFB use, additional barriers reported here and elsewhere included lack of transportation,20 inability to one-stop-shop,19,20 and inconvenient FM locations and hours.19-21 Some participants reported ongoing confusion related to DUFB redemption.

This study uniquely explored experiences of both DUFB users and non-users following the intervention. The authors had hypothesized that non-DUFB users would be less motivated and/or face greater barriers to incentive use, but reported motivators for/barriers to using DUFB were similar across focus group strata. Participants primarily differed in whether they were able to overcome encountered barriers.

Although all participants expressed understanding how to use DUFB when the intervention was delivered, a small subset of focus group participants reported persistent confusion. This likely speaks, in part, to an underlying complexity of incentive programs. FM signage and staff were sufficient to help many participants navigate DUFB. Others desired additional dedicated onsite assistance, especially when using SNAP/DUFB for the first time.

While participants reported the waiting room was an effective setting for the intervention, many expressed surprise discussing FV in a health clinic, echoing a known disconnect between evidence-based practice recommendations and usual care.22-28 Renewed efforts are needed to ensure clinics and providers are equipped to offer support for diet and lifestyle modification,28 including resources to address food insecurity and other unmet social needs.

Table 3 presents key implications and opportunities for clinicians, FM/incentive programs, policy makers, and other stakeholders.

Table 3:

Key Implications and Opportunities for Stakeholders

| Stakeholder | Key Learnings and Opportunities for Improving Healthy Food Incentive Access and Use |

|---|---|

| Farmers Markets and SNAP Incentive Programs |

|

| Providers, Clinics, and Health Systems |

|

| Policymakers |

|

| Researchers |

|

SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; DHS, Department of Human Services; SDH, Social Determinants of Health; MCO, Managed Care Organization

Limitations

Limitations of this study include recruitment at a single health clinic; lack of Spanish-language focus groups;b and a sample limited to participants who remained in the longitudinal portion of the study at five months, were reachable by telephone, and consented to focus group participation. We did, however, capture a range of participant experiences through stratifying focus groups by DUFB use and reached thematic saturation.

Conclusion

A brief waiting room-based informational intervention increased awareness and uptake of a state-wide SNAP incentive program, yet barriers remained for a subset of patients. Building upon clinical-community linkages while increasing the geographic accessibility and ease of incentive redemption may improve food security and healthful food access for vulnerable populations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the patients, staff, and providers of the Ypsilanti Health Center, Washtenaw County Farmers Markets, and our focus group moderators Sharon Murphy and Charo Ledón. We also thank Jason D. Buxbaum for his thoughtful review of the manuscript.

This study was supported in part by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars® program and the W. K. Kellogg Foundation. Study sponsors had no role in study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; writing the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. This study was approved by the University of Michigan Medical School Institutional Review Board, HUM00076630.

Financial disclosure:

Alicia J Cohen has no financial disclosures

Kelsie E. Oatmen has no financial disclosures

Michele Heisler has no financial disclosures

Oran B Hesterman is president and CEO of Fair Food Network, which administers Double Up Food Bucks

Ellen Murphy has no financial disclosures

Suzanna M Zick has no financial disclosures

Caroline R Richardson has no financial disclosures

Glossary

- AJC:

responsible for conception and design of the study, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and manuscript preparation and revision. Had access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis

- KEO

responsible for data analysis, data interpretation, manuscript preparation and revision

- MH:

contributed to study design and data interpretation, and provided assistance with manuscript preparation and revision

- OBH:

contributed to the conception of the study, and provided assistance with manuscript revision

- EM

contributed to study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and provided assistance with manuscript revision

- SMZ

contributed to conception and design of the study, as well as to data interpretation, and provided assistance with manuscript revision

- CRR

contributed to study design and data interpretation, and provided assistance with manuscript preparation and revision

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement:

Alicia J Cohen: no conflicts to disclose

Kelsie E. Oatmen: no conflicts to disclose

Michele Heisler: no conflicts to disclose

Oran B Hesterman: President and CEO of Fair Food Network

Ellen Murphy: no conflicts to disclose

Suzanna M Zick: no conflicts to disclose

Caroline R Richardson: Associate Editor, AJPM

Disclosure of financial conflicts of interest: OBH is president and CEO of Fair Food Network, which administers the Double Up Food Bucks program. No other financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper

Preliminary results were presented at the American Public Health Association annual meeting in November 2016.

Although DUFB has since expanded to grocery stores, at the time of the intervention DUFB was only available at FM in that region. A map with the hours and locations of 8 FM within 1-25 miles of the clinic was provided to all participants as part of the intervention (Appendix A).

Five percent of participants in the quantitative phase of the study preferred communicating in Spanish,5 but none were available to participate in focus groups despite repeated scheduling attempts

References

- 1.Bartlett S, Klerman J, Olsho L, et al. Evaluation of the Healthy Incentives Pilot (HIP) Final Report. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service; 2014. http://www.fns.usda.gov/ops/research-and-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young CR, Aquilante JL, Solomon S, et al. Improving Fruit and Vegetable Consumption Among Low-Income Customers at Farmers Markets: Philly Food Bucks, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013; 10. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Savoie-Roskos M, Durward C, Jeweks M, LeBlanc H. Reducing Food Insecurity and Improving Fruit and Vegetable Intake Among Farmers’ Market Incentive Program Participants. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2016;48(l):70–76.el. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2015.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phipps EJ, Braitman LE, Stites SD, et al. Impact of a Rewards-Based Incentive Program on Promoting Fruit and Vegetable Purchases. Am J Public Health. 2015; 105(1): 166–172. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen AJ, Richardson CR, Heisler M, et al. Increasing Use of a Healthy Food Incentive: A Waiting Room Intervention Among Low-Income Patients. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(2): 154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen AJ, Lachance LL, Richardson CR, et al. “Doubling Up” on Produce at Detroit Farmers Markets: Patterns and Correlates of Use of a Healthy Food Incentive. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(2): 181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olsho LE, Klerman JA, Wilde PE, Bartlett S. Financial incentives increase fruit and vegetable intake among Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participants: a randomized controlled trial of the USDA Healthy Incentives Pilot. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016; 104(2):423–435. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.129320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi SE, Seligman H, Basu S. Cost Effectiveness of Subsidizing Fruit and Vegetable Purchases Through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(5):el47–el55. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mozaffarian D, Liu J, Sy S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of financial incentives and disincentives for improving food purchases and health through the US Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): A microsimulation study. PLOS Med. 2018;15(10):el002661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freedman DA, Flocke S, Shon E-J, et al. Farmers’ Market Use Patterns Among Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Recipients With High Access to Farmers’ Markets. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2017;49(5):397–404.el. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2017.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mustafa Karakus, Keith MacAllum, Roline Milfort, Hongsheng Hao. Nutrition Assistance in Farmers Markets: Understanding the Shopping Patterns of SNAP Participants. US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service; 2014. www.fns.usda.gov/ops/research-and-analysis. Accessed May 12, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olsho LE, Payne GH, Walker DK, Baronberg S, Jernigan J, Abrami A. Impacts of a farmers’ market incentive programme on fruit and vegetable access, purchase and consumption. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(15):2712–2721. doi: 10.1017/S1368980015001056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Creswell JW. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research. Sage Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coyne IT. Sampling in qualitative research. Purposeful and theoretical sampling; merging or clear boundaries? J Adv Nurs. 1997;26(3):623–630. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.t01-25-00999.X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandelowski M. Sample size in qualitative research. Res Nurs Health. 1995; 18(2): 179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005; 15(9): 1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freedman DA, Bell BA, Collins LV. The Veggie Project: a case study of a multi-component farmers’ market intervention. J Prim Prev. 2011;32(3-4):213–224. doi: 10.1007/s10935-011-0245-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cotter EW, Teixeira C, Bontrager A, Horton K, Soriano D. Low-income adults’ perceptions of farmers’ markets and community-supported agriculture programmes. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(8): 1452–1460. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017000088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Savoie Roskos MR, Wengreen H, Gast J, LeBlanc H, Durward C. Understanding the Experiences of Low-Income Individuals Receiving Farmers’ Market Incentives in the United States: A Qualitative Study. Health Promot Pract July 2017:1524839917715438. doi: 10.1177/1524839917715438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grace C, Thomas Grace, Nancy Becker. Barriers to Using Urban Farmers’ Markets: An Investigation of Food Stamp Clients’ Perceptions. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2007;2(1):55–75. doi: 10.1080/19320240802080916 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wetherill MS, Gray KA. Farmers’ markets and the local food environment: identifying perceived accessibility barriers for SNAP consumers receiving temporary assistance for needy families (TANF) in an urban Oklahoma community. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2015;47(2):127–133.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2014.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kolasa KM, Rickett K. Barriers to providing nutrition counseling cited by physicians: a survey of primary care practitioners. Nutr Clin Pract Off Publ Am Soc Parenter Enter Nutr. 2010;25(5):502–509. doi: 10.1177/0884533610380057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heaton PC, Frede SM. Patients’ need for more counseling on diet, exercise, and smoking cessation: results from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. J Am Pharm Assoc JAPhA. 2006;46(3):364–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsai Y-M, Lee-Hsieh J, Turton MA, et al. Nurse preceptor training needs assessment: views of preceptors and new graduate nurses. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2014;45(11):497–505. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20141023-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bell RA, Kravitz RL. Physician counseling for hypertension: what do doctors really do? Patient Educ Couns. 2008;72(1):115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wynn K, Trudeau JD, Taunton K, Gowans M, Scott I. Nutrition in primary care: current practices, attitudes, and barriers. Can Fam Physician Med Fam Can. 2010;56(3):e109–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ammerman AS, DeVellis RF, Carey TS, et al. Physician-based diet counseling for cholesterol reduction: current practices, determinants, and strategies for improvement. Prev Med. 1993;22(1):96–109. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1993.1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kahan S, Manson JE. Nutrition Counseling in Clinical Practice: How Clinicians Can Do Better. JAMA. September 2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.10434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.