Abstract

It is now well established that sensory neurons and receptors display characteristic morphological and electrophysiological properties tailored to their functions. This is especially evident in the auditory system, where cells are arranged tonotopically and are highly specialized for precise coding of frequency- and timing-dependent auditory information. Less well understood, however, are the mechanisms that give rise to these biophysical properties. We have provided insight into this issue by using whole-cell current-clamp recordings and immunocytochemistry to show that BDNF and NT-3, neurotrophins found normally in the cochlea, have profound effects on the firing properties and ion channel distribution of spiral ganglion neurons in the murine cochlea. Exposure of neurons to BDNF caused all neurons, regardless of their original cochlear position, to display characteristics of the basal neurons. Conversely, NT-3 caused cells to show the properties of apical neurons. These results are consistent with oppositely oriented gradients of these two neurotrophins and/or their high-affinity receptors along the tonotopic map, and they suggest that a combination of neurotrophins are necessary to establish the characteristic firing features of postnatal spiral ganglion neurons.

Keywords: cochlea, auditory, Kv1.1, Kv3.1, Kv4.2, BK

The role of neurotrophins in the development and maintenance of neurons and their connections is multifaceted (Snider, 1994; Lewin and Barde, 1996). Not only do neurotrophins affect distinct classes of neurons differentially, but their effects can change over time (McAllister et al., 1997). For example, a neurotrophin that enhances survival or proliferation at one period of development may regulate electrophysiological phenotype at another (Airaksinen et al., 1996; Lesser et al., 1997; Snider, 1998;Carroll et al., 1998). The subtleties of these interactions can be difficult to study in most areas of the nervous system because of cell heterogeneity, but the precisely ordered spiral ganglion, which innervates the cochlear sensory receptor cells, is an ideal place to evaluate differential effects of neurotrophins on an apparently uniform cellular population. Type I cells predominate and compose ∼95% of the ganglion. Each of these neurons form a single synaptic connection with the tonotopically ordered inner hair cell sensory receptors and, therefore relay specific frequency information into the brainstem nuclei. The type II neurons are much fewer in number, and they form synapses with many outer hair cells in the cochlea (Perkins and Morest, 1975; Liberman, 1982; Ryugo, 1992).

Electrophysiological (Mo and Davis, 1997a,b) and immunohistochemical (Romand et al., 1990; Lopez et al., 1995; Anniko et al., 1995; Salih et al., 1999; Adamson et al., 1999) studies have revealed an unexpected heterogeneity in the firing features and voltage-dependent ionic currents of spiral ganglion neurons that appear to vary as a function of position in the cochlea (Adamson et al., 1999; Davis et al., 2001). To determine whether these electrophysiological features are subject to extrinsic regulation, we evaluated the effects of neurotrophins on neuronal firing patterns and on ion channel distribution of postnatal spiral ganglion neurons placed in tissue culture. We used brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and neurotrophin-3 (NT-3), which act via high-affinity tyrosine kinase receptors, trkB and trkC, respectively (Barbacid, 1994; Patapoutian and Reichardt, 2001), and are known to be present in the peripheral auditory system (Pirvola et al., 1992, 1994; Ylikoski et al., 1993;Knipper et al., 1996; Mou et al., 1997; Cochran et al., 1999; Farinas et al., 2001). To address the issue of cell specificity, neurons from the apex (low frequency region) and base (high frequency region) of the cochlea were studied separately. We found that BDNF and NT-3 had opposite and selective effects on apical and basal neurons, respectively. Under control conditions, the two populations of neurons could be distinguished by accommodation, action potential latency, and duration. After exposure to BDNF, however, these characteristic differences were lost and all cells, regardless of original cochlear location, had the characteristics of basal neurons. NT-3 had the converse action, causing all cells to display features of apical neurons. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed correlated changes in the distribution of four K+ channel types likely to play a role in these firing patterns: KCa, Kv1.1, Kv3.1, and Kv4.2. The first three, KCa, Kv1.1, Kv3.1, are associated with regulating firing frequency, rate of adaptation, and action potential duration, whereas, Kv4.2 can affect the time course of neuronal latency. These data suggest that the postnatal cochlea contains oppositely oriented gradients of neurotrophins or their cognate receptors that play an important role in establishing the distinctive electrophysiological properties of spiral ganglion neurons.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue culture. Experiments were performed on CBA/CaJ mouse spiral ganglion neurons. The spiral ganglion was removed from postnatal day 3–8 (P3–P8) animals. Synaptogenesis of the spiral ganglion neurons with its peripheral targets is complete at this time (Pujol et al., 1998), although the cartilage of the osseous spiral lamina has not yet solidified into bone. This procedure produced the best compromise between working with relatively mature cells while still retaining viability in tissue culture for detailed electrophysiological analysis. To ensure that each experimental condition was equally represented by animals from the postnatal ages examined, only animals of the same age were compared within an experiment. For example, cultures prepared for immunostaining consisted of control, BDNF, and NT-3-supplemented cultures, which were made in duplicate. All cultures prepared in this way were stained simultaneously using the same solutions and protocols. Cultures were prepared in a similar manner for the electrophysiological evaluations, however, recordings often extended over a number of days for all conditions. Therefore, all experiments were matched for age and timein vitro.

Postnatal animals were decapitated, and both inner ears were removed from the base of the cranium. Cochleas were extracted from the outer bony labyrinth. The outer ligament–stria vascularis and organ of Corti were dissected away from the central core of the cochlea that contained the spiral ganglion. The ganglion was divided into thirds; base and apical sections were plated as explants in culture dishes coated with poly-l-lysine. Both cochleas were used from each mouse, and the same region of neurons from each ear were placed into separate portions of the same culture dish. After 1 week in culture, the tissue from each ear was located in separate elongated patches ∼5 mm apart. Cells were kept at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 and maintained in growth medium composed of DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 4 mml-glutamine, and 0.1% penicillin–streptomycin.

In some cultures either 5 ng/ml BDNF (Preprotech, Rocky Hill, NC) or 5 ng/ml NT-3 (Preprotech) was added to the culture media at the time of plating the cells into culture dishes. We used these low concentrations to activate specifically the high-affinity cognate receptors for BDNF and NT-3, trkB, and trkC, respectively (Pirvola et al., 1992, 1994;Ylikoski et al., 1993; Schecterson and Bothwell, 1994; Knipper et al., 1996; Mou et al., 1997; Cochran et al., 1999; Farinas et al., 2001). To confirm that these low concentrations were not also activating the low-affinity, nonspecific p75NTR receptor we also exposed a series of cultures to 5 ng/ml of nerve growth factor (NGF; Preprotech). NGF was chosen because spiral ganglion neurons do not express the cognate high-affinity receptor during the postnatal ages that we evaluated (Ernfors et al., 1992; Ylikoski et al., 1993;Schecterson and Bothwell, 1994; Cochran et al., 1999; Vega et al., 1999), so that if it had an effect it would not be caused by its binding to a high-affinity receptor. Our electrophysiological analysis revealed no differences between the control cultures and those exposed to 5 ng/ml NGF (n = 29; p < 0.01 for latency and duration; p < 0.05 forAPmax).

Electrophysiology. The whole-cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique was used to obtain current-clamp recordings from spiral ganglion neurons in vitro. Electrodes were pulled on a two-stage vertical puller (PP-83; Narishige, Tokyo, Japan), and the shafts were coated with sylgard (Dow Corning, Midland, MI) to reduce capacitance. Just before use, electrode tips were fire-polished (MF-83 microforge; Narishige); electrode resistances typically ranged from 3 to 5 MΩ in standard pipette and bathing solutions (see below). Pipette offset current was zeroed immediately before contacting the cell membrane. Current clamp measurements were made with theIfast circuitry of the Axon Instruments (Foster City, CA) Axopatch 200A amplifier to reduce or eliminate oscillations that may occur during fast afterhyperpolarizations (Magistretti et al., 1996).

A standard set of solutions was used to approximate physiological conditions. The basic internal solution was as follows (in mm): 112 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 0.1 CaCl2, 11 EGTA, and 10 HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.45. Neurons were exposed to the following bath solution (in mm): 137 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.7 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 17 glucose, 50 sucrose, and 10 HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.45. The osmolarity of the solution was adjusted with sucrose to 350 mOsm to match the osmolarity of the growth medium.

Recordings were made at room temperature (19–22°C) from the neuronal cell somata. Data were digitized with an Indec IDA 15125 interface in an IBM-compatible personal computer; the programs for data acquisition and analysis were written in Borland C++and Microsoft Visual Basic (generously contributed by Dr. Mark R. Plummer, Rutgers University). Unless otherwise indicated, each segment of data was digitized at 5 kHz and filtered at 1 kHz. Current-clamp recordings were considered acceptable when they met the following criteria: stable membrane potentials, low noise levels, discernible membrane time constant with step current injection, and overshooting action potentials. If any of these parameters changed during an experiment, indicating compromised cell health or metabolic failure, the remaining data were not analyzed.

Antibodies. Neurofilament 200 (NF200) monoclonal antiserum (Sigma, N-0142, lot #96H-4813) was used to distinguish neurons and processes from background satellite cells (Mou et al., 1998). Confirmation that all NF200-positive neurons also contained neuron-specific enolase epitopes was performed in a previous study (Mou et al., 1997).

Four classes of K+ channel antibodies (against Kv1.1/1.2, Kv3.1, Kv4.2, and KCa) were used to characterize spiral ganglion neurons in tissue cultures and sections. Two subunits from the Shaker family, Kv1.1 and Kv1.2, were examined in this study. Both monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies were obtained for each. The Kv1.1 polyclonal antibody (Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel; APC-009, lot An-01) was made against amino acid residues 416–495 of the C terminus of mouse full-length Kv1.1 protein. The Kv1.1 monoclonal antibody (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY; 05–407, lot 15781) was made from a synthetic peptide corresponding to amino acid residues 458–476 of the C terminus of rat brain Kv1.1. The polyclonal Kv1.2 antibody was made against amino acid residues 417–498 of the C terminus of rat protein and recognized the full-length Kv1.2 protein (Alomone Labs; APC-010, lot An-01). The Kv1.2 monoclonal antibody was made from a bacterially expressed GST-fusion protein corresponding to amino acid residues 428–499 of rat heart Kv1.2 (Upstate Biotechnology; 05–408-MN, lot 17153). Based on Western blotting and immunoprecipitation assays of the polyclonal antibodies, reaction products were specific for each the Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 subunit purified antibodies, and no cross-reactivity occurred between mKv1.1, mKv1.2, or mKv1.3, the three most closely related voltage-gated K+ channel proteins of theShaker-like subfamily (Koch et al., 1997).

Two Kv3.1 polyclonal antibodies used were provided by Dr. Teresa Perney (Rutgers University, Newark, NJ). One antibody was made against the C terminus (C-Kv3.1) of Kv3.1 and recognizes only the longer of the two identified splice variants of the channel (the b variant), whereas the other antibody made against the N terminus (N-Kv3.1) recognizes both splice variants of the Kv3.1 channel (Luneau et al., 1991). The C- and N-Kv3.1 antibodies stained neurons identically; however, the lowest background staining levels were obtained when using C-Kv3.1. Another Kv3.1 polyclonal antibody (Alomone Labs; APC-014) used was raised in rabbit against highly purified peptide (rKv3.1b567–585), corresponding to residues 567–585 of rat Kv3.1b. Anti-Kv3.1b recognizes a full-length Kv3.1b protein. The epitope is specific for Kv3.1b, and it is not present in the alternatively spliced Kv3.1a form (Rettig et al., 1992).

The high-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel (KCa) polyclonal antibody (Alomone Labs; APC-021, lot An-01) was made against residues 1098–1196 of mouse slo protein (Butler et al., 1993). The Kv4.2 antibody (Alomone Labs; APC-023) was raised against a highly purified peptide corresponding to amino acid sequences 454–469 of rat Kv4.2 (Baldwin et al., 1991; Roberds and Tamkun, 1991).

Immunofluorescence. Indirect immunofluorescence was used on cultures fixed in 100% methanol at −20°C for 6 min. Cultures were then incubated for 1 hr in 5% normal goat serum (NGS) + 1% Triton X-100, rinsed thoroughly, and incubated for an additional hour in 5% NGS. The primary antibody was applied and left for 1 hr at room temperature or 24–48 hr at 4°C. A fluorescent-conjugated secondary antiserum was subsequently applied for 1 hr at room temperature. Between each step, except after the application of the blocking solution, the tissue was rinsed 3 times for 5 min with 0.01m PBS, pH 7.4.

Preadsorption experiments were done for Kv1.1, Kv3.1, and KCa. Immunolabeling of each of these antibodies was abolished by preincubation of the antisera with the appropriate synthetic peptide. Additionally, negative controls, where the primary antibody was omitted, were routinely evaluated to assay the specificity of all the secondary antibodies. No specific labeling was detected in any of these control experiments. Another approach to test the specificity of the antibodies was to use more than one antibody for the same channel subunit because there would be little likelihood that nonspecific staining would be identical in differently prepared antibodies. Multiple antibodies were obtained for Kv1.1, Kv1.2, and Kv3.1. The staining patterns that we observed in spiral ganglion neurons did not differ between the different antisera made to a single-channel subunit, thus giving us confidence that the antibodies selectively labeled the ion channel subunits that they were made against.

Image acquisition. Images were acquired with a Hamamatsu C4742–95 charge-coupled digital (CCD) camera using the manual exposure setting; images were acquired with Zeiss Axiovision software and further processed in Adobe Photoshop. Brightness, contrast, and sharpening tools in Adobe Photoshop were used to enhance the contrast between neuronal and background signals. Comparisons of staining were only made between images acquired with identical exposure times that received the same digital enhancements.

Quantification of immunofluorescent data. Each series of immunolabeling experiments were performed on animals with the same birth date that were cultured and stained on the same day so that comparisons between the experimental conditions, control, BDNF, and NT-3, were made from cultures that were treated similarly. Each dish of cultured neurons contained two patches of cells, one from each ear, obtained from the same areas of both cochleas from one animal. Therefore, at least six animals were required for a single immunolabeling experiment because we always included duplicates. Analysis of antibody staining in each dish was accomplished by photographing the central regions of the two patches of cells and quantifying the labeling according to staining intensity. Each neuron was ranked as weakly labeled (+), moderately labeled (++), or strongly labeled (+++) to best reflect the observed differences in staining intensities. The data obtained from each image were then used to calculate a weighted percentage of stained cells using the equation:

Use of a weighted scale allowed us to take the staining intensities of individual cells into account; this was important because quantification of labeling based solely on comparison of the number of stained cells did not accurately represent the data (see legend to Fig. 5). As a control, however, we compared weighted and unweighted values for all conditions and obtained essentially identical results. In the two cases where the comparisons were not the same, however, both sets of numbers are included in Results. For a subset of our experiments we also verified the reliability of our staining intensity evaluations by quantifying average pixel intensity (Adobe Photoshop) from the most intensely stained region of the neuron. We found that our visual ranking correlated well with average pixel intensity levels, thus validating our methods. Furthermore, the investigator was blind with regard to each experimental condition and cochlear location; images were always selected and acquired when visualizing the NF200 antibody rather than the ion channel antibody. We also found that neuronal density was not correlated with staining intensity.

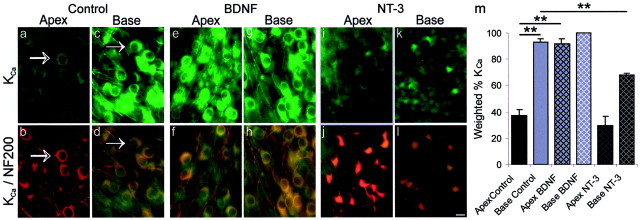

Fig. 5.

Exposure to BDNF increased KCaantibody staining, whereas NT-3 decreased it. a–l, Representative images of spiral ganglion neurons from the apex and base in control, BDNF, and NT-3 conditions. The top panels(a, c, e, g, i, k) show neurons labeled with FITC-conjugated KCa antibody, and the bottom panels (b, d, f, h, j,l) show the overlay of the green FITC-conjugated KCa antibody and the red TRITC-conjugated NF200 antibody. Because a pure count of the number of stained cells would not accurately represent the obvious difference in label intensity that we consistently observed (compare Fig. 6a,b), these results also illustrate the need for a weighted ranking method of analysis. a–d, Spiral ganglion neurons in control cultures label significantly more with anti-KCa in the base compared with the apex.a, The faint profiles of KCa-labeled neurons are discernable; however, they were considerably lighter than those in the base (compare arrow in a witharrow in c). b, The double exposure shows prominent NF200-positive labeling, indicating that neurons were present in the culture, and demonstrating that the faintly stained cells in a were neurons. Thearrows in a and b indicate an NF200-positive neuron that minimally expressed the protein for KCa, therefore in b it retains most of the red (TRITC) color in the overlay.c, Anti-KCa stained a population of neurons removed from the base of the cochlea. The arrowindicates the round profile of a neuron strongly labeled with the anti-KCa. d, A double exposure of KCa (green) and NF200 (red) staining revealed that the majority of neurons were labeled with both antibodies, as indicated by theyellow color of each of the neurons.e–h, Neurons isolated from the cochlea and grown in culture supplemented with 5 ng/ml BDNF showed an increase in KCa antibody labeling. e, Neurons from the apical cochlea stained similarly to those from the base.f, The double exposure shows yellowneuron cell bodies, verifying that the basal neurons exposed to 5 ng/ml BDNF were labeled with both NF200 and KCa antibodies.g, Neurons from the basal, high-frequency region of the cochlea stained similarly to those from the base control.h, The double exposure shows yellowneuron cell bodies, verifying that the basal neurons exposed to 5 ng/ml BDNF are labeled with both NF200 and KCa antibodies.i–l, Cultures of spiral ganglion neurons supplemented with 5 ng/ml NT-3 demonstrated a decrease in KCa antibody labeling in neurons isolated from the base, while preserving the apex–base differences observed in controls. i, Neurons isolated from the apex of the cochlea lightly labeled with the KCa antibody. j, The double exposure shows that every neuron identified with anti-NF200 weakly labeled with anti-KCa, resulting in a predominance of thered NF200 color. k, Neurons isolated from the base of the cochlea stained significantly darker than the apex; there was, however, significantly less staining than that observed in the base control neurons. l, Double exposure of KCa-positive neurons (green) and NF200-positive neurons (red). For a–l, spiral ganglia were isolated from postnatal day 5 CBA/CaJ mice and maintained for 7 d in vitro. Tissues were incubated in a 1:800 dilution of anti-KCa overnight at 4°C.m, Histogram of the weighted percentage of KCa antibody staining of apical and basal spiral ganglion neurons in each condition (Control, BDNF, andNT-3) for three experiments. The error bar is not shown for the base BDNF condition because all three values were 100%. **p < 0.01 for comparisons between the experimental conditions denoted by the solid lines.

The optimal concentration of each ion channel antibody used was determined with serial dilutions and by choosing a range of concentrations that were high enough to detect the neuronal staining and low enough to keep the background staining levels to a minimum. At least two concentrations were used for each antibody tested, and comparisons of the quantification from each concentration series showed that the staining patterns obtained were not concentration dependent (Adamson, 2001). Thus, all data using a particular antibody were combined, and the weighted percentages from each cochlear location were averaged and compared statistically using Student's two-tailedt test.

RESULTS

Neurotrophin effects on spiral ganglion neuron electrophysiology

The results in this study are based on recordings from a total of 251 neurons, 235 of which were analyzed in depth for each of six experimental categories: apex and base neurons not exposed to media supplemented with neurotrophins (N = 34 andN = 47, respectively), apex and base neurons exposed to media supplemented with 5 ng/ml of BDNF (N = 41 andN = 44, respectively), and apex and base neurons exposed to media supplemented with 5 ng/ml NT-3 (N = 39 and N = 30, respectively).

Adaptation

Previous studies from our laboratory showed that the spiral ganglion is composed of an electrophysiologically diverse group of neurons that can be separated into two categories according to whether or not they accommodate in response to maintained depolarization (Mo and Davis, 1997a,b; Davis et al., 2001). With regard to this parameter, apical neurons comprised a relatively nonuniform group, with approximately one-third of the cells being categorized as slowly adapting, a property not found in neurons from the base. Example recordings from five different apical neurons at the voltage at which they fire the greatest number of action potentials (APmax) are shown in the left column of traces in Figure 1 (inset). The lowest trace is from a neuron that had anAPmax of only one, indicating that this cell fired only a single action potential regardless of the amount of depolarization. Other examples (Fig. 1, inset, left column of traces) are from neurons that fired a maximum of 3, 11, 14, and 20 action potentials in response to the 240 msec stimulus. These recordings represent the types of apical neuron firing patterns that we observed. The distribution ofAPmax levels for all the apical neuron recordings under control conditions ranged from 1 to 24 (Fig. 1). Under control conditions, 32% of the apical neurons were classified as slowly adapting, firing ≥6 action potentials in response to a 240 msec step depolarization (Mo and Davis, 1997a).

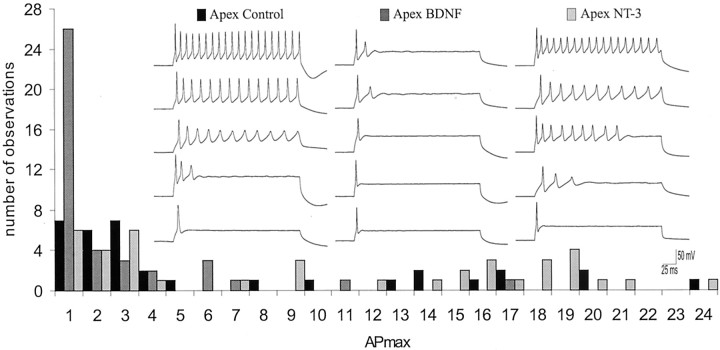

Fig. 1.

The rate of adaptation increased when apical spiral ganglion neurons were exposed to BDNF, yet remained relatively unchanged when exposed to NT-3. APmax for all apical neurons plotted in a frequency histogram for each of the three conditions: control cultures, cultures exposed to BDNF, and cultures exposed to NT-3. Inset, Example traces from five different apical neurons taken at APmax for each of the three conditions: control cultures (left series of sweeps), cultures exposed to 5 ng/ml BDNF (middle series of sweeps), and cultures exposed to 5 ng/ml NT-3 (rightseries of sweeps).

What was striking about apical neurons that were exposed to media supplemented with BDNF was the reduction in the number of slowly adapting cells. Only six of the neurons (15%) showed reduced accommodation (Fig. 1); therefore, the majority of the neurons were rapidly adapting (Fig. 1, inset, middle series of traces). Conversely, NT-3 had the opposite effect, increasing the percentage of slowly adapting cells to 57% (Fig. 1, inset, right columnof traces). Quantitative analysis of the different conditions (Fig.3a) showed that the averageAPmax of apical neurons exposed to BDNF (2.54 ± 0.50) was significantly lower than apical neurons in unsupplemented media (6.65 ± 1.19; p < 0.01). Apical neurons exposed to NT-3 showed an even higher averageAPmax value of 10.0 ± 1.23, and this was significantly different from the BDNF condition but not from the control condition (p < 0.01 andp > 0.06, respectively).

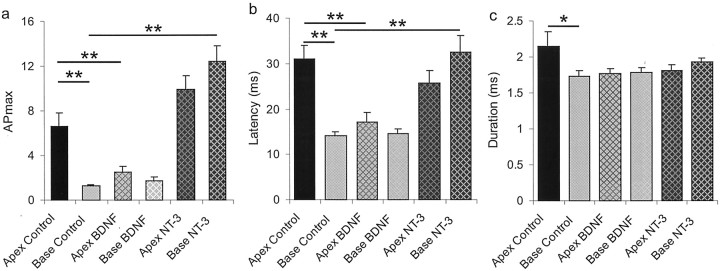

Fig. 3.

APmax and latency were systematically altered by addition of neurotrophins to the neuronal cultures. Action potential durations, which were significantly different between apical and basal neurons in control cultures, were relatively unchanged when cultures were supplemented with either BDNF or NT-3. a, The maximum number of action potentials that an individual neuron is capable of firing (APmax) was significantly different between apical and basal neurons in control cultures. Both apical and basal neurons exposed to BDNF showed APmaxvalues similar to the base control neurons. Apical and basal neurons exposed to NT-3, however, showed APmaxvalues similar to or greater than the apical control neurons. **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05, for comparisons between experimental conditions denoted by the solid lines for this and subsequent bar graphs. The following conditions were compared statistically using Student's two-tailedt test: apex control to base control, apex control to apex BDNF, apex control to apex NT-3, base control to base BDNF, and base control to base NT-3. b, A similar pattern exists for action potential latency measurements. The initial difference in action potential latency between the apical and basal neurons in control conditions at threshold was no longer evident in the presence of each neurotrophin. Both apical and basal neurons exposed to NT-3 had latencies more similar to the apical than basal control neurons. Apical and basal neurons exposed to BDNF had latencies more similar to the basal than the apical control neurons. c, Aside from the significant difference between apical and basal neurons in control cultures, neurotrophins appeared to have no effect on action potential duration. The duration showed a tendency to be decreased by treatment with either BDNF or NT-3 when compared with apex controls but the differences failed to achieve statistical significance.

Very little change was noted in theAPmax levels when basal neurons were exposed to BDNF (Figs. 2,3a). Under control conditions 100% of the basal neurons were rapidly adapting (Fig. 2) having an average APmax value of 1.32 ± 0.08 (Fig. 3a). Basal neurons exposed to BDNF were also predominately rapidly adapting (95%) and had anAPmax value indistinguishable from control (1.70 ± 0.34; p > 0.26). NT-3, however, produced a significant decrease in the percentage of basal neurons that were rapidly adapting (30%) (Fig. 2), yielding a higher averageAPmax (12.4 ± 1.42) that was significantly greater than basal neuron control and basal neuron + BDNF conditions (p < 0.01) (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 2.

The rate of adaptation decreased when basal spiral ganglion neurons were exposed to NT-3, yet remained relatively unchanged when exposed to BDNF. APmax for all basal neurons plotted in a frequency histogram for each of the three conditions: control cultures, cultures exposed to BDNF, and cultures exposed to NT-3. Inset, Example traces from five different basal neurons taken at APmaxfor each of the three conditions: control cultures (leftseries of sweeps), cultures exposed to 5 ng/ml BDNF (middle series of sweeps), and cultures exposed to 5 ng/ml NT-3 (right series of sweeps).

Latency

Another parameter that differs between apical and basal neurons is action potential latency: the time between the onset of the step current injection and the peak of the initial action potential at electrophysiological threshold. The significant difference (p < 0.01) in the latency between the apex (31.06 ± 2.99 msec) and the base neurons (14.21 ± 0.72 msec) under control conditions was eliminated by application of either BDNF or NT-3 (p > 0.25 and p > 0.121, respectively). As with our observations ofAPmax, neurons exposed to NT-3 resembled the apical neurons, displaying longer latencies, regardless of their original location. NT-3 prolonged the latency in the basal neurons (32.61 ± 3.64 msec) to a level that did not substantially differ from the apex control condition (p > 0.73), and was significantly different from the base control neurons (p < 0.01). The latency measurements from the apical neurons exposed to NT-3 (25.66 ± 2.69 msec) were not significantly different from apex controls (p > 0.18). Application of BDNF, on the other hand, would be expected to reduce latency if it is assumed that BDNF has the opposite action on latency when compared with NT-3. Consistent with this expectation, BDNF caused a decrease in apical neuron latency (17.2 ± 1.97 msec;p < 0.01) but did not have a significant effect on basal neuron latency (14.6 ± 1.0 msec; p > 0.75) (Fig. 3). We also determined that the two classes of neurons, rapidly adapting and slowly adapting, that composed the apical control group did not have significantly different latencies (31.9 ± 3.9 msec,n = 23 and 29.3 ± 4.54 msec, n = 11, respectively; p > 0.69). Therefore, much like the regulation of accommodation, latency differences observed between apical and basal spiral ganglion neurons appear to be influenced by BDNF and NT-3.

Duration

Action potential duration, along withAPmax and latency, also differed between apical and basal neurons under control conditions measured at electrophysiological threshold. In the absence of added neurotrophin, apical neurons had prolonged action potential durations (2.15 ± 0.21 msec) compared with basal neurons (1.72 ± 0.08 msec;p < 0.05). Surprisingly, however, neurotrophins appeared to have no obvious impact on action potential duration (Fig.3c). None of the experimental conditions produced significant differences. For example, action potential duration did not change significantly with the addition of NT-3 to the culture medium for the apical (1.81 ± 0.08) or basal neurons (1.93 ± 0.06 msec) compared with those in control conditions (p > 0.12 and p > 0.33, respectively). Furthermore, action potential duration of apical neurons (1.76 ± 0.08) and basal neurons (1.77 ± 0.07 msec) were unaltered when supplemented with BDNF (p > 0.068 and p > 0.07, respectively) (Fig. 3).

As with our analysis of latency, we also compared action potential duration between slowly and rapidly adapting apical neurons. Unlike latency, however, duration was significantly different between the two groups of neurons under control conditions (2.46 ± 0.27 msec,n = 23 vs 1.49 ± 0.18 msec, n = 11; p < 0.05), suggesting that this parameter may be subject to differential regulation. For this reason we evaluated action potential duration for the rapidly and slowly adapting neurons separately (Fig. 4). Interestingly, the same general pattern of neurotrophin effect described for theAPmax and latency was also observed for duration when the rapidly adapting neurons were considered alone (Fig. 4a). Exposure to BDNF caused a significant reduction in action potential duration of apical neurons (1.79 ± 0.08 msec;n = 35) compared with controls (p < 0.01), whereas the basal neurons were unaffected (1.77 ± 0.08 msec; n = 42) compared with controls (p > 0.66). Conversely, NT-3 produced a significant increase in basal neuron action potential duration (2.12 ± 0.14 msec; n = 9;p < 0.05), but did not cause a significant change in duration of action potentials of rapidly adapting apical neurons (1.9 ± 0.13; n = 17; p > 0.19).

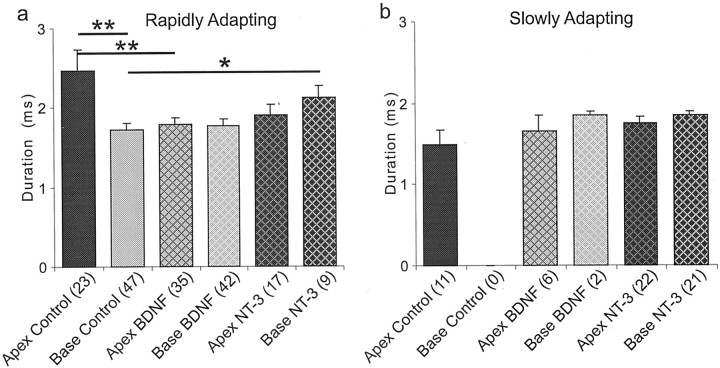

Fig. 4.

Action potential duration is altered by neurotrophins in rapidly adapting, but not slowly adapting neurons.a, Action potential duration differed in rapidly adapting neurons exposed to low concentrations of neurotrophins (5 ng/ml). BDNF decreased this parameter in apical neurons; NT-3 increased it in basal neurons. **p < 0.01 and *p < 0.05 for comparisons between the experimental conditions denoted by thesolid lines. b, Action potential durations in slowly adapting neurons were brief and remained unaltered when exposed to neurotrophins. In apical neurons no significant effects were noted in this parameter between control, BDNF, and NT-3 conditions. The control basal neurons could not be compared because none of the 47 neurons fell within the slowly adapting category; nevertheless there was no significant difference between the BDNF and NT-3 conditions in slowly adapting basal neurons.

In contrast, the slowly adapting neurons appeared to show little, if any, differences in action potential duration across experimental conditions (Fig. 4b). The apical control durations did not differ from the apical BDNF (1.65 ± 0.2 msec; n = 6) or apical NT-3 (1.74 ± 0.09 msec; n = 22) conditions (p > 0.59 and p > 0.18, respectively). Although there were no slowly adapting basal neuron controls for comparison purposes, the small number of measurements from slowly adapting basal neurons seen after exposure to BDNF (1.85 ± 0.05; n = 2) did not differ substantially from slowly adapting neurons exposed to NT-3 (1.84 ± 0.06; n = 21).

Neurotrophin effects on potassium channel distribution

The change in electrophysiological response properties that occurred as a result of neurotrophin exposure indicates that the complement of ion channels expressed by spiral ganglion neurons must have been altered. To test this assumption explicitly, we decided to investigate how KCa, Kv1.1, Kv4.2, and Kv3.1 antibody labeling was affected by neurotrophins. These channel types were chosen for study because of their well known involvement in determining action potential timing and shape (Hille, 2001). We hypothesized that the ion channel types that contributed to increasing the rate of adaptation (KCa, Kv1.1, and Kv3.1) and decreasing the latency (KCa, Kv1.1) would be upregulated with BDNF in accord with our electrophysiological results. We also hypothesized that because NT-3 transformed the rapidly adapting, brief latency basal neurons into slow ones, then the ion channel types that contributed to increasing the rate of adaptation and latency may be downregulated, and/or ion channel types known to increase the latency of response (Kv4.2) could be upregulated. In general our results showed that BDNF increased KCa, Kv1.1, and Kv3.1 antibody labeling, whereas NT-3 decreased KCa and increased Kv4.2 antibody staining. A detailed immunohistochemical analysis of the results is given below.

KCa antibody distribution

The KCa current is associated with regulating action potential latency and firing frequency in a wide variety of neurons (Lancaster and Nicoll, 1987; Storm, 1987; Wang et al., 1998; Shao et al., 1999; Hille, 2001). Moreover, splice variants of this channel type have been found to be differentially distributed in the chick cochlea (Navaratnam et al., 1997). Relative to control cultures (Fig. 5a–d), addition of BDNF resulted in increased KCaantibody labeling in apical neurons to such a degree (91.8 ± 3.6%) that it matched the intensity of basal neuron staining (92.8 ± 2.4) (Fig. 5e–h) and was significantly higher than apex control neurons (37.2 ± 4.8%; p < 0.01), thus eliminating the observed apical–basal gradient found in control cultures. Although there was a slight increase in the amount of staining in the basal neurons with BDNF (100 ± 0.0%), it was not significantly different than either the base control (p > 0.6) or the apex BDNF cultures (p > 0.1) (Fig. 5g, comparec, e) but was significantly higher than apex control cultures (p < 0.01). Spiral ganglion neuron cultures supplemented with NT-3 showed a significant reduction in the intensity of KCa staining in the base (68.3 ± 0.8%) (Fig. 5k,m) (p< 0.01) but not in the apex (29.5 ± 6.8) (Fig.5i) (p > 0.3) compared with control cultures (Fig. 5a,c). However the preferential distribution of KCa in basal cochlear neurons exposed to NT-3 compared with apical neurons exposed to the same concentration of NT-3 (Fig. 5k,i, respectively) (p < 0.01) was maintained, despite a significant reduction in the labeling of base NT-3 neurons compared with base control neurons (Fig. 5k,c, respectively) (p < 0.01). As described in Materials and Methods, we routinely compared results obtained with both weighted and unweighted measurements. For the case of the KCaantibody, however, these two methods lead to different conclusions. Unweighted measurements, which only take the number of labeled neurons into account, did not show the difference between apical and basal neurons in control conditions (80.2 ± 9.7 and 97.5 ± 2.5%, respectively; p > 0.1). They did, however, show a significant decline from control conditions when basal neurons were exposed to NT-3 (78.9 ± 4.6; p < 0.01). We take this as further support of our use of the weighted measurement scales.

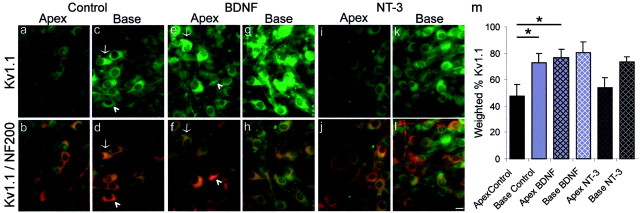

Kv1.1 antibody distribution

Another channel type that also decreases response latency and limits the number of action potentials that fire in response to prolonged stimulation in spiral ganglion neurons is the voltage-activated shaker subunit Kv1.1 (Brew and Forsythe, 1995;Rathouz and Trussell, 1998). This DTX-sensitive channel type is present in spiral ganglion neurons (Tempel et al., 1996; Mo and Davis, 1998) and has the distinction of activating at very low voltage levels (Grissmer et al., 1994; Hopkins et al., 1994). Relative to control cultures (Fig. 6a–d), exogenous addition of BDNF resulted in an increased labeling with Kv1.1 antibody in apical neurons (79.4 ± 5.2%) to such a degree that it was significantly higher than apex control neurons (52.6 ± 9.5; p < 0.05), thus eliminating the observed apical–basal gradient found in control cultures (Fig.6e–h). There was significantly more Kv1.1 antibody in the base control, apex BDNF, and base BDNF cultures (Fig.6c,e,g) each having >75% staining (Fig. 6m). Although there was a slight increase in the amount of staining in the basal neurons with BDNF (89.8 ± 5.3%), it was not significantly different from either the base control (84.5 ± 3.6%;p > 0.06) or the apex BDNF (p> 0.1) cultures. Unlike the reduced labeling of KCa that we observed in NT-3, Kv1.1 staining intensity was unchanged compared with their control apex (Fig.6a) (p > 0.5) and control base (Fig.6c) (p > 0.9) counterparts in spiral ganglion neuron cultures exposed to NT-3 (Fig. 6i,k).

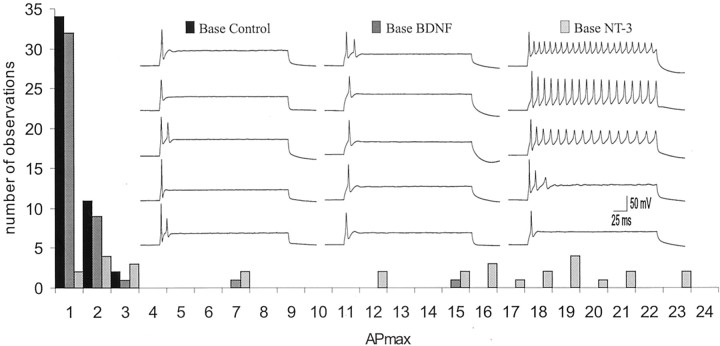

Fig. 6.

Exposure to BDNF increased Kv1.1 antibody staining, whereas NT-3 was relatively ineffective. a–l, Representative images of spiral ganglion neurons from the apex and base in control, BDNF, and NT-3 conditions. The top panels(a, c, e, g, i, k) show neurons labeled with FITC-conjugated Kv1.1 antibody, and the bottom panels(b, d, f, h, j, l) show the overlay of thegreen FITC-conjugated Kv1.1 antibody and thered TRITC-conjugated NF200 antibody.a–d, Spiral ganglion neuron cultures without exogenously added neurotrophins labeled significantly more with anti-Kv1.1 in the basal neurons compared with the apical ones.a, Spiral ganglion neurons labeled lightly with anti-Kv1.1. b, The double exposure shows prominent NF200-positive labeling, indicating that neurons were present in the culture, and demonstrating that the faintly stained cells were neurons.c, Anti-Kv1.1 stained a population of neurons removed from the base of the cochlea. NF200-positive neurons (d) strongly labeled with the anti-Kv1.1 (c). The intensity of Kv1.1 label, however, revealed heterogeneity because neurons from the same cochlear location were either labeled intensely (arrow) or weakly (arrowhead). d, A double exposure of Kv1.1 (green) and NF200 (red) staining showed that the majority of neurons observed ind labeled with anti-Kv1.1 (compare with neurons inc). e–h, Neurons isolated from the cochlea and grown in culture supplemented with 5 ng/ml BDNF. Kv1.1 staining was significantly greater in apical neurons. e,Neurons from the apex and exposed to BDNF showed anti-Kv1.1 staining comparable with that observed in the base control where some were strongly labeled (arrow) and others weakly labeled (arrowhead). f, Kv1.1-positive neurons,green; NF200-positive neurons, red; double-labeled neurons, yellow. g,Neurons from the base of the cochlea and exposed to BDNF stained similarly to base controls. h, The double exposure shows neuron cell bodies that are yellow in color, verifying that the basal neurons exposed to 5 ng/ml BDNF were labeled with antibodies against both NF200 and Kv1.1 antibodies.i–l, Cultures of spiral ganglion neurons supplemented with 5 ng/ml NT-3 did not show significantly changed distributions of Kv1.1 protein in neurons isolated from either the base or the apex, thus the apex–base differences observed in controls was preserved.i, Neurons isolated from the apex of the cochlea labeled lightly with the Kv1.1 antibody. j, The double exposure shows that some of the neurons identified with anti-NF200 labeled weakly with anti-Kv1.1. k, Neurons isolated from the base of the cochlea showed significantly more staining than neurons from the apex. l, Double exposure of Kv1.1-positive neurons, green; NF200-positive neurons,red. For a–l, spiral ganglia were isolated from postnatal day 5 CBA/CaJ mice and maintained for 7 din vitro. Tissues were incubated in a 1:200 dilution of anti-Kv1.1 overnight at 4°C. m, Histogram of the weighted percentage of Kv1.1 antibody staining of apical and basal spiral ganglion neurons in each condition (Control, BDNF, and NT-3) for four experiments. *p < 0.05 for comparisons between the experimental conditions denoted by the solid lines.

In summary, two ion channel proteins, KCa and Kv1.1, both of which are present in spiral ganglion neurons (Tempel et al., 1996; Mo and Davis, 1998; Bowne-English and Davis, 1999) and are associated with accommodation and abbreviated latencies were observed predominately in neurons derived from the base or high frequency coding region of the cochlea. Although the percentage of difference anti-Kv1.1 staining between apex and base neurons was less than that seen with anti-KCa, both antibodies were increased by BDNF and were either unaffected or decreased with NT-3.

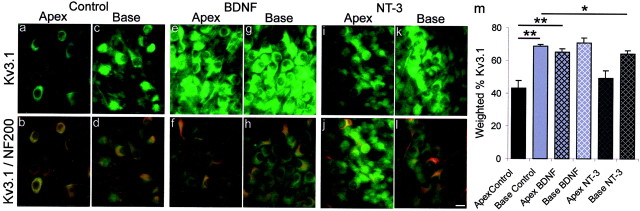

Kv3.1 antibody distribution

Kv3.1, which can contribute to limiting the action potential duration and increasing accommodation (Whim and Kaczmarek, 1998; Rudy et al., 1999), like KCa and Kv1.1, was localized predominately to the basal spiral ganglion neurons in control cultures (Fig. 7). Relative to apical control cultures (43.3 ± 4.2%) (Fig. 7a–d), apical cultures exposed to supplemental BDNF showed a significantly greater Kv3.1 staining intensity (65.2 ± 1.7%; p < 0.01) (Fig. 7e), which was indistinguishable from base BDNF (71.0 ± 2.6%; p > 0.1) (Fig. 7g) and base control cultures (68.9 ± 0.9%; p > 0.1) (Fig. 7c). Apical spiral ganglion cultures supplemented with NT-3 (49.0 ± 5.0) demonstrated no significant changes in the intensity of Kv3.1 staining when compared with their apical cohorts in control cultures (Fig. 7i,a, respectively) (p > 0.2). There was, however, a small but significant decrease (p < 0.05) in the amount of Kv3.1 in NT-3-supplemented base cultures (64.2 ± 1.9) versus base control cultures, suggesting that NT-3 may have downregulated the amount of Kv3.1 protein in the base. This small decrease was not detected in the unweighted measurements between base control (95.6 ± 2.9) and base NT-3 (96.3 ± 1.5; p > 0.8), suggesting that this decline could be attributed to the intensity of label, rather than the numbers of neurons that stained with Kv3.1.

Fig. 7.

Exposure to BDNF increased Kv3.1 antibody staining, whereas NT-3 had relatively little effect.a–l, Representative images of spiral ganglion neurons from the apex and base in control, BDNF, and NT-3 conditions. Thetop panels (a, c, e, g, i, k) show neurons labeled with FITC-conjugated Kv3.1 antibody, and thebottom panels (b, d, f, h, j, l) show the overlay of the green FITC-conjugated Kv3.1 antibody and the red TRITC-conjugated NF200 antibody.a–d, Spiral ganglion neuron cultures without exogenously added neurotrophins. Neurons isolated from the base showed significantly more anti-Kv3.1 label than neurons from the apex.a, A low percentage of spiral ganglion neurons labeled lightly with anti-Kv3.1. b, The double exposure shows NF200-positive labeling, indicating that neurons were present in the culture, but only a small percentage labeled with the Kv3.1 antibody (green). c, Anti-Kv3.1 stained a population of neurons removed from the base of the cochlea.d, A double exposure of Kv3.1 (green) and NF200 (red) staining revealed that the majority of neurons were labeled with both antibodies, as indicated by the yellow color of each of the neurons. e–h, Neurons isolated from the cochlea and grown in media supplemented with 5 ng/ml BDNF. Apical neurons showed a significant increase in Kv3.1 labeling. e, Neurons from the apical cochlea stained similarly to those from the base.f, Kv3.1-positive neurons, green; NF200-positive neurons, red; double-labeled neurons,yellow. g, Neurons from the base of the cochlea stained similarly to those from the base control.h, The double exposure shows neuron cell bodies that areyellow in color, verifying that the basal neurons exposed to 5 ng/ml BDNF were labeled with antibodies against both NF200 and Kv3.1. i–l, Cultures of spiral ganglion neurons supplemented with 5 ng/ml NT-3. Anti-Kv3.1 staining was reduced in neurons isolated from the base. i, Neurons isolated from the apex of the cochlea labeled lightly with the Kv3.1 antibody.j, The double exposure shows that most neurons identified with anti-NF200 only labeled weakly with anti-Kv3.1.k, Neurons isolated from the base of the cochlea were stained significantly more than neurons from the apex.l, Double exposure of Kv3.1-positive neurons,green; NF200-positive neurons, red. Fora–l, spiral ganglia were isolated from postnatal day 5 CBA/CaJ mice and maintained for 7 d in vitro. Tissues were incubated in a 1:400 dilution of anti-Kv3.1 for 48 hr at 4°C. m, Histogram of the weighted percentage of Kv3.1 antibody staining of apical and basal spiral ganglion neurons in each condition (Control, BDNF, and NT-3) for four experiments. **p < 0.01 and *p < 0.05 for comparisons between the experimental conditions denoted by thesolid lines.

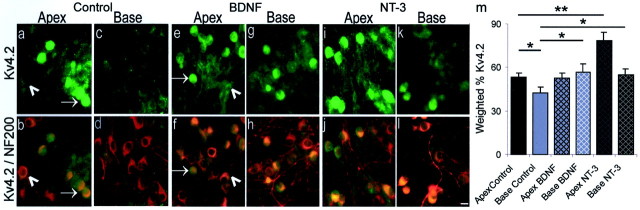

Kv4.2 antibody distribution

The latency differences that we observed between apical and basal neurons could be explained by multiple mechanisms. In addition to KCa and Kv1.1, which are associated with decreased response latency, channel types with slow voltage-dependent inactivation are known to increase latency. If caused by inactivating currents, the prolonged latencies observed in the electrophysiological studies could be a consequence of a wide variety of channel subunits that result from the assembly of α and β subunits in many homomeric and heteromeric K+ channels, giving rise to currents varying in their kinetics of inactivation, all of which affect the time course of neuronal latency (Baldwin et al., 1991;Schroter et al., 1991; Rettig et al., 1994; Serodio et al., 1994, 1996;Sewing et al., 1996; Heinemann et al., 1996; Song et al., 1998; Serodio and Rudy, 1998; Lu and Trussell, 2000). Despite this potential complexity, we chose to evaluate anti-Kv4.2 because of its preferential location in apical neurons (Adamson et al., 1999).

Relative to control cultures (Fig.8a–d), addition of NT-3 resulted in increased Kv4.2 labeling in both apical (78.5 ± 5.7) (Fig. 8i) and basal (55.2 ± 3.6) (Fig. 8k) neurons where each was significantly higher than their respective controls (53.4 ± 3.0; p < 0.01 for apex) (Fig.8a) (42.9 ± 3.8; p < 0.05 for base) (Fig. 8c). Addition of BDNF to the culture medium did not produce a change in Kv4.2 staining in apex neurons (53.0 ± 3.3) compared with controls (Figs. 8e,a, respectively) (p > 0.9). The amount of Kv4.2 staining in base BDNF neurons (56.8 ± 5.8), however, was significantly higher than base control neurons (Fig. 8g,c, respectively) (p < 0.05), therefore eliminating the observed apical–basal gradient found in control cultures.

Fig. 8.

Exposure to NT-3 increased Kv4.2 antibody staining, whereas BDNF had relatively little effect.a–l, Representative images of spiral ganglion neurons from the apex and base in control, BDNF, and NT-3 conditions. Thetop panels (a, c, e, g, i, k) show neurons labeled with FITC-conjugated Kv4.2 antibody, and thebottom panels (b, d, f, h, j, l) show the overlay of the green FITC-conjugated Kv4.2 antibody and the red TRITC-conjugated NF200 antibody.a–d, Spiral ganglion neurons cultured without exogenously added neurotrophins. Apical neurons showed significantly more anti-Kv4.2 label than basal neurons. a, Anti-Kv4.2 stained a population of neurons removed from the apex of the cochlea. The intensity of Kv4.2 label, however, was not uniform. Neurons from the same cochlear location were either intensely labeled (arrow) or weakly labeled (arrowhead).b, A double exposure of Kv4.2 (green) and NF200 (red) staining revealed that not all neurons observed in b labeled with Kv4.2 (compare with neurons in a). c,Spiral ganglion neurons labeled lightly with anti-Kv4.2.d, The double exposure shows NF200-positive labeling, indicating that neurons were present in the culture, however, the intensity of label with the Kv4.2 antibody (green) was lower in basal (c) than apical neurons (a). e–h, Neurons isolated from the cochlea and grown in media supplemented with 5 ng/ml BDNF. Kv4.2 antibody staining was increased in neurons isolated from the basal cochlea but not the apex, therefore eliminating the apex–base difference observed in control cultures. e, The majority of neurons from the apex stained with anti-Kv4.2 with intensities similar to controls where some were strongly labeled (arrow) and others weakly labeled (arrowhead). f, Double exposure of Kv4.2-positive neurons, yellow; NF200-positive neurons,red. g, Neurons from the basal cochlea stained similarly to those from the apex. h, The double exposure shows that not all of the population of neurons identified with NF200 stained with anti-Kv4.2. i–l, Cultures of spiral ganglion neurons supplemented with 5 ng/ml NT-3. The distribution of Kv4.2 protein in neurons isolated from both the base and the apex was significantly increased from controls, and the apex–base difference was preserved. i, Neurons isolated from the apex of the cochlea labeled strongly with the Kv4.2 antibody.j, The double exposure shows that most of the neurons identified with anti-NF200 labeled with anti-Kv4.2. k,The addition of NT-3 significantly increased the amount of Kv4.2 staining in basal neurons compared with controls; however, a large population of neurons remained only lightly labeled. l,The double exposure of Kv4.2-positive neurons (yellow) and unlabeled NF200-positive neurons (red). For a–l, spiral ganglia were isolated from postnatal day 4 CBA/CaJ mice and maintained for 7 din vitro. Tissues were incubated in a 1:400 dilution of anti-Kv4.2 overnight at 4°C. m, Histogram of the weighted percentage of Kv4.2 antibody staining of apical and basal spiral ganglion neurons in each condition (Control, BDNF, and NT-3) for four experiments. **p < 0.01 and *p < 0.05 for comparisons between the experimental conditions denoted by the solid lines.

DISCUSSION

The neurotrophins BDNF and NT-3 have profound effects on spiral ganglion firing properties and the underlying voltage-gated ion channel distribution. Under control conditions, we find that apical neurons show slow adaptation and prolonged latency, and possess high levels of Kv4.2 and low levels of KCa, Kv1.1, and Kv3.1. Exposure to low concentrations of BDNF, however, causes apical neurons to become almost indistinguishable from basal neurons. They show significantly higher levels of KCa, Kv1.1, and Kv3.1 antibody staining and predominately show rapid adaptation and brief response latencies. Basal neurons, on the other hand, respond quite differently and appear to be transformed into apical ones on exposure to NT-3. Instead of their characteristic firing pattern and high levels of KCa and low levels of Kv4.2 found normally, the opposite electrophysiological and staining patterns are observed when basal neurons were exposed to NT-3. It appears, therefore, that a number of features that exemplify basal and apical spiral ganglion neurons are determined by the opposing actions of two neurotrophins. This antagonistic relationship between BDNF and NT-3, which has been shown to regulate growth (McAllister et al., 1997) and cell survival (Giehl et al., 2001) in the CNS, may also work in an opposing manner to modify the electrophysiological phenotype of peripheral auditory neurons.

Although dramatic, the apparent conversion of apical to basal neurons by BDNF, and the opposite changes induced by NT-3, were not always complete, and the “transformed” neurons were not identical in all respects to the control counterparts. An analysis of these differences provides useful insights into the modulatory effects of neurotrophins. For example, apical neurons exposed to NT-3 had a significantly greaterAPmax than apical controls. This may indicate that the in vivo concentration of NT-3 is lower than the 5 ng/ml used in this study. A second example is the restricted effect of neurotrophins on action potential duration. Only the rapidly adapting subpopulation of apical neurons responded to BDNF and NT-3, a result further implicating additional regulation and strengthening our earlier conclusion that rapidly and slowly adapting neurons should be classified separately (Mo and Davis, 1997a).

In general, we found a remarkable correspondence between our antibody staining patterns and our measurements of latency andAPmax. For example, anti-KCa staining intensity increased in cultures exposed to BDNF, but was reduced in basal neuron cultures exposed to NT-3, suggesting that this channel type is associated with the basal, rather than apical-like electrophysiology. Furthermore, anti-Kv1.1 staining changed in cultures exposed to BDNF in a manner similar to KCa, increasing staining intensity from apical control levels. Moreover, despite the relatively low percentage of differences of anti-Kv4.2 labeling between apex and base control cultures, we observed neurotrophin regulation that was opposite to the other voltage-gated antibodies. This was in agreement with reports in the literature demonstrating that Kv4.2 and other A-type currents slow response latency (Bruckner and Hyson, 1998; Kanold and Manis, 1999;Shibata et al., 2000). Consistent with our hypothesis, we found that Kv4.2 staining increased significantly when neurons were cultured in the presence of NT-3, corresponding to an apical-like electrophysiology. One caveat to our predictions, however, was the increase in Kv4.2 staining in apical neurons exposed to BDNF. If this increase in Kv4.2 subunits were the sole contributor to this electrophysiological feature, then we would expect to see an increase in latency in apical BDNF cultures. Because we instead saw the predicted decrease in latency, we must conclude that either the Kv4.2 subunits combine as heteromultimers that have different effects on neuronal latency (Serodio et al., 1994), or that increases in other channel types, such as KCa and Kv1.1, outweigh the increase in Kv4.2 and therefore have a greater impact on the final latency.

Because our electrophysiological observations show a strong correlation with our immunocytochemical data, it is reasonable to suggest that the neurotrophins themselves or their high-affinity receptors may be differentially localized in the peripheral auditory system. In particular, BDNF, and/or its cognate high-affinity receptor, trkB, should be found at higher levels in the base of the cochlea, whereas NT-3, and/or its cognate high-affinity receptor, trkC, should be found preferentially in the apex. Interestingly, this pattern is the opposite of what one would predict from studies of null mutations of these neurotrophins and their high-affinity receptors. These studies indicated that neurotrophins are graded in the cochlea, but they showed that NT-3 supports spiral ganglion neuron survival primarily in the middle and basal cochlea, whereas BDNF supports the survival of spiral ganglion neurons predominately in the middle and apex (Bianchi et al., 1996; Fritzsch et al., 1997a,b, 1998, 1999; Farinas et al., 2001). Based on these studies, therefore, one would have to conclude that during embryogenesis BDNF is localized predominately in the apex of the cochlea, whereas NT-3 is localized in the base, as has been shown in a recent study (Farinas et al., 2001).

There are, however, reports of the distribution of BDNF and NT-3 in the adult cochlea that suggest that neurotrophins in the mature organ have a distribution opposite to that found during development. Our prediction that NT-3 is preferentially distributed in the apex of the cochlea is supported by experiments in which the distribution of the targeted replacement of the NT-3 coding exon with a construct containing lacZ cDNA was examined (Fritzsch et al., 1997b). These data, which show that NT-3 is higher in the apex than the base, is consistent with the results that we present herein and could easily explain our findings. In addition, our prediction that BDNF is preferentially distributed in the base of the cochlea is supported byin situ hybridization studies showing that BDNF mRNA is higher in the basal spiral ganglion neurons than in the apical ones (M. Knipper, personal communication). Because BDNF can work through an autocrine mechanism in the spiral ganglion and other neurons (Schecterson and Bothwell, 1992; Lewin and Barde, 1996; Vega et al., 1999; Zha et al., 2001; Hansen et al., 2001), this finding may also support our observations. Nevertheless, further studies are necessary to evaluate the topologic distribution of neurotrophins and their high-affinity tyrosine kinase receptors, as well as regulators of secretion, such as neuregulin (Morley, 1998), in adult animals and from other sources, such as the central targets (Lefebvre et al., 1994;Hafidi et al., 1996; Hafidi, 1999) and support cells (Pirvola et al., 1992; Qian et al., 1992; Wiechers et al., 1999; Barres and Barde, 2000;Farinas et al., 2001). It is most likely a combination of all of these elements plus intrinsic features of the cells themselves that are required for spiral ganglion neurons to achieve the adult electrophysiological phenotype.

The presence of transient gradients of molecules during development is a well established concept (Wolpert, 1989). They are found not only in the CNS (Levitt et al., 1997) but are also important for pattern formation in structures such as the limbs and thorax (Wolpert, 1994;Tickle, 1999; Vervoort, 2000) and are undoubtedly related to the well established gradients of development in the cochlea (Rubel, 1978;Romand, 1983). Nevertheless, these gradients are thought to be used mainly during growth and differentiation and, until recently (Traiffort et al., 1998, 1999; Potter, 2001), were thought to be rendered superfluous at their conclusion. The concept of a gradient that is retained into adulthood is an intriguing one because it suggests that the control of neurotrophins over the endogenous membrane properties of sensory neurons may not be transient. Related to this is the observation that certain neurotrophins continue to play a role into postnatal times (Maisonpierre et al., 1990; Carroll et al., 1998;Watanabe et al., 2000). There is a precedence for the fact that neurotrophins could continue to affect the auditory system (Hafidi, 1999). It is possible that neurotrophins establish and/or maintain ion channel gradients in various regions of the auditory pathway (Navaratnam et al., 1997; Rosenblatt et al., 1997; Grigg et al., 2000;Zhou et al., 2001; Li et al., 2001), including tonotopic specializations in the peripheral auditory system that could persist into adulthood. Future experiments will be directed toward determining whether the characteristic differences between apical and basal spiral ganglion neurons are maintained in the adult, fully developed auditory system and, if so, how they contribute to auditory function.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant NIDCD01856. We thank Dr. Mark R. Plummer for helpful discussions and for critically reading an earlier version of this manuscript, Dr. Lucy Hsu for expert technical support, and Dr. Teresa Perney for her generous donation of Kv3.1 antibodies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamson CL. PhD thesis. The State University of New Jersey, Rutgers; 2001. Differential distribution of voltage-gated ion channels in spiral ganglion neurons. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adamson CL, Perney TM, Peng L, Davis RL. Immunohistochemical distribution of potassium channel subunits in murine spiral ganglion neurons. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1999;25:667.10. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Airaksinen MS, Koltzenburg M, Lewin GR, Masu Y, Helbig C, Wolf E, Brem G, Toyka KV, Thoenen H, Meyer M. Specific subtypes of cutaneous mechanoreceptors require neurotrophin-3 following peripheral target innervation. Neuron. 1996;16:287–295. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anniko M, Arnold W, Stigbrand T, Strom A. The human spiral ganglion. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1995;57:68–77. doi: 10.1159/000276714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldwin TJ, Tsaur ML, Lopez GA, Jan YN, Jan LY. Characterization of a mammalian cDNA for an inactivating voltage-sensitive K+ channel. Neuron. 1991;7:471–483. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90299-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbacid M. The Trk family of neurotrophin receptors. J Neurobiol. 1994;25:1386–1403. doi: 10.1002/neu.480251107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barres BA, Barde Y. Neuronal and glial cell biology. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10:642–648. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bianchi LM, Conover JC, Fritzsch B, DeChiara T, Lindsay RM, Yancopoulos GD. Degeneration of vestibular neurons in late embryogenesis of both heterozygous and homozygous BDNF null mutant mice. Development. 1996;122:1965–1973. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.6.1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowne-English J, Davis RL. Potassium channel heterogeneity in spiral ganglion neurons. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1999;25:667.9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brew HM, Forsythe ID. Two voltage-dependent K+ conductances with complementary functions in postsynaptic integration at a central auditory synapse. J Neurosci. 1995;15:8011–8022. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-12-08011.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruckner S, Hyson RL. Effect of GABA on the processing of interaural time differences in nucleus laminaris neurons in the chick. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:3438–3450. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butler A, Tsunoda S, McCobb DP, Wei A, Salkoff L. mSlo, a complex mouse gene encoding “maxi” calcium-activated potassium channels. Science. 1993;261:221–224. doi: 10.1126/science.7687074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carroll P, Lewin GR, Koltzenburg M, Toyka KV, Thoenen H. A role for BDNF in mechanosensation. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:42–46. doi: 10.1038/242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cochran SL, Stone JS, Bermingham-McDonogh O, Akers SR, Lefcort F, Rubel EW. Ontogenetic expression of trk neurotrophin receptors in the chick auditory system. J Comp Neurol. 1999;413:271–288. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19991018)413:2<271::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis RL, Adamson CL, Reid MA. Tonotopic distribution of voltage-gated ion currents in spiral ganglion neurons. Abstr Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2001;24:595. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ernfors P, Merlio J-P, Persson H. Cells expressing mRNA for neurotrophins and their receptors during embryonic rat development. Eur J Neurosci. 1992;4:1140–1158. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1992.tb00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farinas I, Jones KR, Tessarollo L, Vigers AJ, Huang E, Kirstein M, de Caprona DC, Coppola V, Backus C, Reichardt LF, Fritzsch B. Spatial shaping of cochlear innervation by temporally regulated neurotrophin expression. J Neurosci. 2001;21:6170–6180. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-06170.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fritzsch B, Silos-Santiago I, Bianchi LM, Farinas I. Effects of neurotrophin and neurotrophin receptor disruption on the afferent inner ear innervation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1997a;8:277–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fritzsch B, Farinas I, Reichardt LF. Lack of neurotrophin 3 causes losses of both classes of spiral ganglion neurons in the cochlea in a region-specific fashion. J Neurosci. 1997b;17:6213–6225. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-16-06213.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fritzsch B, Barbacid M, Silos-Santiago I. The combined effects of trkB and trkC mutations on the innervation of the inner ear. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1998;16:493–505. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(98)00043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fritzsch B, Pirvola U, Ylikoski J. Making and breaking the innervation of the ear: neurotrophic support during ear development and its clinical implications. Cell Tissue Res. 1999;295:369–382. doi: 10.1007/s004410051244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giehl KM, Rohrig S, Bonatz H, Gutjahr M, Leiner B, Bartke I, Yan Q, Reichardt LF, Backus C, Welcher AA, Dethleffsen K, Mestres P, Meyer M. Endogenous brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurotrophin-3 antagonistically regulate survival of axotomized corticospinal neurons in vivo. J Neurosci. 2001;21:3492–3502. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-10-03492.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grigg JJ, Brew HM, Tempel BL. Differential expression of voltage-gated potassium channel genes in auditory nuclei of the mouse brainstem. Hear Res. 2000;140:77–90. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grissmer S, Nguyen AN, Aiyar J, Hanson DC, Mather RJ, Gutman GA, Karmilowicz MJ, Auperin DD, Chandy KG. Pharmacological characterization of five cloned voltage-gated K+ channels, types Kv1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.5, and 3.1, stably expressed in mammalian cell lines. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:1227–1234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hafidi A. Distribution of BDNF, NT-3 and NT-4 in the developing auditory brainstem. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1999;17:285–294. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(99)00043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hafidi A, Moore T, Sanes DH. Regional distribution of neurotrophin receptors in the developing auditory brainstem. J Comp Neurol. 1996;367:454–464. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960408)367:3<454::AID-CNE10>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hansen MR, Zha XM, Bok J, Green SH. Multiple distinct signal pathways, including an autocrine neurotrophic mechanism, contribute to the survival-promoting effect of depolarization on spiral ganglion neurons in vitro. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2256–2267. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-07-02256.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heinemann SH, Rettig J, Graack HR, Pongs O. Functional characterization of Kv channel beta-subunits from rat brain. J Physiol (Lond) 1996;493 (Pt 3):625–633. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hille B. Ionic channels of excitable membranes. Sinauer; Sunderland, MA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hopkins WF, Allen ML, Houamed KM, Tempel BL. Properties of voltage-gated K+ currents expressed in Xenopus oocytes by mKv1.1, mKv1.2 and their heteromultimers as revealed by mutagenesis of the dendrotoxin-binding site in mKv1.1. Pflügers Arch. 1994;428:382–390. doi: 10.1007/BF00724522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanold PO, Manis PB. Transient potassium currents regulate the discharge patterns of dorsal cochlear nucleus pyramidal cells. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2195–2208. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-02195.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knipper M, Zimmermann U, Rohbock K, Kopschall I, Zenner HP. Expression of neurotrophin receptor trkB in rat cochlear hair cells at time of rearrangement of innervation. Cell Tissue Res. 1996;283:339–353. doi: 10.1007/s004410050545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koch RO, Wanner SG, Koschak A, Hanner M, Schwarzer C, Kaczorowski GJ, Slaughter RS, Garcia ML, Knaus HG. Complex subunit assembly of neuronal voltage-gated K+ channels. Basis for high-affinity toxin interactions and pharmacology. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27577–27581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lancaster B, Nicoll RA. Properties of two calcium-activated hyperpolarizations in rat hippocampal neurones. J Physiol (Lond) 1987;389:187–203. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lefebvre PP, Malgrange B, Staecker H, Moghadass M, Van de Water TR, Moonen G. Neurotrophins affect survival and neuritogenesis by adult injured auditory neurons in vitro. NeuroReport. 1994;5:865–868. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199404000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lesser SS, Sherwood NT, Lo DC. Neurotrophins differentially regulate voltage-gated ion channels. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1997;10:173–183. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1997.0656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levitt P, Barbe MF, Eagleson KL. Patterning and specification of the cerebral cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1997;20:1–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lewin GR, Barde YA. Physiology of the neurotrophins. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1996;19:289–317. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.001445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li W, Kaczmarek LK, Perney RM. Localization of two high-threshold potassium channel subunits in the rat central auditory system. J Comp Neurol. 2001;437:196–218. doi: 10.1002/cne.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liberman MC. The cochlear frequency map for the cat: labeling auditory-nerve fibers of known characteristic frequency. J Acoust Soc Am. 1982;72:1441–1449. doi: 10.1121/1.388677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lopez CA, Olson ES, Adams JC, Mou K, Denhardt DT, Davis RL. Osteopontin expression detected in adult cochleae and inner ear fluids. Hear Res. 1995;85:210–222. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu T, Trussell LO. Inhibitory transmission mediated by asynchronous transmitter release. Neuron. 2000;26:683–694. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luneau CJ, Williams JB, Marshall J, Levitan ES, Oliva C, Smith JS, Antanavage J, Folander K, Stein RB, Swanson R, Kaczmarek LK, Buhrow SA. Alternative splicing contributes to K+ channel diversity in the mammalian central nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3932–3936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Magistretti J, Mantegazza M, Guatteo E, Wanke E. Action potentials recorded with patch-clamp amplifiers: are they genuine? Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:530–534. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)40004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maisonpierre PC, Belluscio L, Friedman B, Alderson RF, Wiegand SJ, Furth ME, Lindsay RM, Yancopoulos GD. NT-3, BDNF, and NGF in the developing rat nervous system: parallel as well as reciprocal patterns of expression. Neuron. 1990;5:501–509. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90089-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McAllister AK, Katz LC, Lo DC. Opposing roles for endogenous BDNF and NT-3 in regulating cortical dendritic growth. Neuron. 1997;18:767–778. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mo Z-L, Davis RL. Endogenous firing patterns of murine spiral ganglion neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1997a;77:1294–1305. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.3.1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mo Z-L, Davis RL. Heterogeneous voltage dependence of inward rectifier currents in spiral ganglion neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1997b;78:3019–3027. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.6.3019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mo Z-L, Davis RL. Ionic conductances underlying rapid adaptation in spiral ganglion neurons in vitro. Abstr Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 1998;21:91. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morley BJ. ARIA is heavily expressed in rat peripheral auditory and vestibular ganglia. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;54:170–174. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00355-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mou K, Hunsberger CL, Cleary JM, Davis RL. Synergistic effects of BDNF and NT-3 on postnatal spiral ganglion neurons. J Comp Neurol. 1997;386:529–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mou K, Adamson CL, Davis RL. Time-dependence and cell-type specificity of synergistic neurotrophin actions on spiral ganglion neurons. J Comp Neurol. 1998;402:129–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Navaratnam DS, Bell TJ, Tu TD, Cohen EL, Oberholtzer JC. Differential distribution of Ca2+-activated K+ channel splice variants among hair cells along the tonotopic axis of the chick cochlea. Neuron. 1997;19:1077–1085. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80398-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patapoutian A, Reichardt LF. Trk receptors: mediators of neurotrophin action. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2001;11:272–280. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perkins RE, Morest DK. A study of cochlear innervation patterns in cats and rats with the Golgi method and Nomarski optics. J Comp Neurol. 1975;163:129–158. doi: 10.1002/cne.901630202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pirvola U, Ylikoski J, Palgi J, Lehtonen E, Arumae U, Saarma M. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurotrophin 3 mRNAs in the peripheral target fields of developing inner ear ganglia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:9915–9919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pirvola U, Arumae U, Moshnyakov M, Palgi J, Saarma M, Ylikoski J. Coordinated expression and function of neurotrophins and their receptors in the rat inner ear during target innervation. Hear Res. 1994;75:131–144. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Potter JD. Morphostats a missing concept in cancer biology. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:161–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pujol R, Lavigne-Rebillard M, Lenoir M. Development of sensory and neural structures in the mammalian cochlea. In: Rubel EW, Popper AN, Fay RR, editors. Development of the auditory system. Springer; New York: 1998. pp. 146–192. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Qian JA, Bull MS, Levitt P. Target-derived astroglia regulate axonal outgrowth in a region-specific manner. Dev Biol. 1992;149:278–294. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90284-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rathouz M, Trussell L. Characterization of outward currents in neurons of the avian nucleus magnocellularis. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:2824–2835. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.6.2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rettig J, Wunder F, Stocker M, Lichtinghagen R, Mastiaux F, Beckh S, Kues W, Pedarzani P, Schroter KH, Ruppersberg JP. Characterization of a Shaw-related potassium channel family in rat brain. EMBO J. 1992;11:2473–2486. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05312.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rettig J, Heinemann SH, Wunder F, Lorra C, Parcej DN, Dolly JO, Pongs O. Inactivation properties of voltage-gated K+ channels altered by presence of beta-subunit. Nature. 1994;369:289–294. doi: 10.1038/369289a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roberds SL, Tamkun MM. Cloning and tissue-specific expression of five voltage-gated potassium channel cDNAs expressed in rat heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1798–1802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Romand R. Development of the cochlea. In: Romand R, editor. Development of auditory and vestibular systems. Academic; New York: 1983. pp. 47–88. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Romand R, Sobkowicz H, Emmerling M, Whitlon D, Dahl D. Patterns of neurofilament stain in the spiral ganglion of the developing and adult mouse. Hear Res. 1990;49:119–125. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(90)90099-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rosenblatt KP, Sun ZP, Heller S, Hudspeth AJ. Distribution of Ca2+-activated K+ channel isoforms along the tonotopic gradient of the chicken's cochlea. Neuron. 1997;19:1061–1075. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80397-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rubel EW. Ontogeny of structure and function in the vertebrate auditory system. In: Autrum H, Jung R, Loewenstein WR, McKay DM, Teuber HL, editors. Handbook of sensory physiology. Springer; Berlin: 1978. pp. 135–237. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rudy B, Chow A, Lau D, Amarillo Y, Ozaita A, Saganich M, Moreno H, Nadal MS, Hernandez-Pineda R, Hernandez-Cruz A, Erisir A, Leonard C, Vega-Saenz de Miera E. Contributions of Kv3 channels to neuronal excitability. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;868:304–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ryugo DK. The auditory nerve: peripheral innervation cell body morphology, and central projections. In: Popper AN, Fay RR, editors. The mammalian auditory pathway: neuroanatomy. Springer; New York: 1992. pp. 34–93. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Salih SG, Housley GD, Raybould NP, Thorne PR. ATP-gated ion channel expression in primary auditory neurones. NeuroReport. 1999;10:2579–2586. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199908200-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schecterson LC, Bothwell M. Novel roles for neurotrophins are suggested by BDNF and NT-3 mRNA expression in developing neurons. Neuron. 1992;9:449–463. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90183-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]