Abstract

The recently described two-pore-domain K+channels, TASK-1 and TASK-3, generate currents with a unique set of properties; specifically, the channels produce instantaneous open-rectifier (i.e., “leak”) K+ currents that are modulated by extracellular pH and by clinically useful anesthetics. In this study, we used histochemical and in vitroelectrophysiological approaches to determine that TASK channels are expressed in serotonergic raphe neurons and to show that they confer a pH and anesthetic sensitivity to these neurons. By combining in situ hybridization for TASK-1 or TASK-3 with immunohistochemical localization of tryptophan hydroxylase, we found that a majority of serotonergic neurons in both dorsal and caudal raphe cell groups contain TASK channel transcripts (∼70–90%). Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were obtained from raphe cells that responded to 5-HT in a manner characteristic of serotonergic neurons (i.e., with activation of an inwardly rectifying K+ current). In those cells, we isolated an endogenous K+conductance that had properties expected of TASK channel currents; raphe neurons expressed a joint pH- and halothane-sensitive open-rectifier K+ current. The pH sensitivity of this current (pK ∼7.0) was intermediate between that of TASK-1 and TASK-3, consistent with functional expression of both channel types. Together, these data indicate that TASK-1 and TASK-3 are expressed and functional in serotonergic raphe neurons. The pH-dependent inhibition of TASK channels in raphe neurons may contribute to ventilatory and arousal reflexes associated with extracellular acidosis; on the other hand, activation of raphe neuronal TASK channels by volatile anesthetics could play a role in their immobilizing and sedative–hypnotic effects.

Keywords: rat, KCNK, acidosis, anesthetic, hybridization, 5-HT

The resting membrane potential and input resistance of neurons are key determinants of neuronal excitability; these intrinsic properties are determined, in large part, by constitutive activity of K+ selective channels. In recent years, a novel gene family of background K+ channels has been identified, members of which have characteristics that are distinctly different from most other K+ channels and consistent with a role in setting membrane potential and input resistance (e.g., weak voltage dependence, extremely fast kinetics, etc.) (for review, seeLesage and Lazdunski, 2000; Goldstein et al., 2001; Patel and Honore, 2001; Patel et al., 2001). Although these so-called KCNK channels generally show some degree of background activity at normal resting potentials, they are nevertheless also subject to modulation by numerous factors. For example, channel activity is influenced by prevailing physicochemical conditions such as temperature, intracellular or extracellular pH, oxygen tension, and membrane stretch and can be modulated by neurotransmitters, bioactive lipids, and anesthetics (Lesage and Lazdunski, 2000; Goldstein et al., 2001; Patel and Honore, 2001; Patel et al., 2001). Thus, the intrinsic properties conferred by these channels are not fixed, and their modulation can have dramatic effects on neuronal excitability.

The TASK subgroup of KCNK channels currently comprises five members (Kim and Gnatenco, 2001; Patel and Honore, 2001) that can be further subdivided by sequence homology and functional properties. Included in one group are TASK-2 and TASK-4/TALK-2 (Reyes et al., 1998; Gray et al., 2000; Decher et al., 2001; Girard et al., 2001), neither of which is strongly expressed in the brain (Girard et al., 2001; Talley et al., 2001). The other group includes TASK-1, TASK-3, and TASK-5. Of these, TASK-5 is distinct in that it has a very restricted CNS distribution (E. M. Talley and D. A. Bayliss, unpublished observations) and, to this point, has not been found to make a functional channel (Kim and Gnatenco, 2001; Vega-Saenz et al., 2001). In contrast, TASK-1 and TASK-3 are widely expressed throughout the brain, with overlapping distributions in many regions (Talley et al., 2000, 2001; Vega-Saenz et al., 2001). Moreover, they present a constellation of functional properties that is unique among all K+channels cloned to date. They generate essentially instantaneous, non-inactivating currents that have a weakly rectifying I–Vrelationship in asymmetric K+ that is predicted by constant field considerations [i.e., “open” or Goldman–Hodgkin–Katz (GHK) rectification]. Furthermore, they are regulated by extracellular pH in the physiological range, with pK for channel inhibition by protons of ∼7.4 for TASK-1 and ∼6.7 for TASK-3, and they are activated by clinically appropriate concentrations of inhalation anesthetics (Lesage and Lazdunski, 2000; Goldstein et al., 2001; Patel and Honore, 2001).

Thus, TASK-1 and TASK-3 represent neuronal “leak” K+ channels that are sensitive to both extracellular pH and anesthetics. Understanding the neurobiological consequences that follow from the distinct modulatory potential intrinsic to TASK channels will depend, at least in part, on identifying the neurons that functionally express the channels. Here, we show that serotonergic dorsal and caudal raphe neurons express TASK-1 and TASK-3 transcripts and a pH- and anesthetic-sensitive K+ conductance. In those cells, pH-dependent inhibition of TASK channels may contribute to ventilatory and arousal reflexes associated with extracellular acidosis; on the other hand, activation of raphe neuronal TASK channels by anesthetics could play a role in their immobilizing and sleep-inducing effects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Histochemistry

Preparation of histological specimens. For in situ hybridization using radiolabeled cRNA probes, adult rats (Wistar and Sprague Dawley; 200–350 gm) were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine (200 and 14 mg/kg, i.m.) and decapitated, and brains were removed, blocked, and frozen on dry ice. Coronal sections (10 μm) were cut through the brainstem in a cryostat, thaw-mounted onto charged slides (Superfrost Plus; Fisher Scientific, Houston, TX), and stored at −80°C. For non-isotopic hybridization and combined immunohistochemistry, four adult Sprague Dawley rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital (60 mg/kg, i.p.) and perfused transcardially with 200 ml of PBS, pH 7.4, followed by 4% phosphate-buffered paraformaldehyde (0.1 m PB; pH 7.4). The brainstem was removed, post-fixed overnight with the same fixative at 4°C, and then sectioned in the coronal plane (30 μm) on a vibratome. Sections were stored at −20°C in a cryoprotectant solution [30% RNase free sucrose, 30% ethylene glycol, and 1% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP-40) in 100 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4] (Watson et al., 1986).

Preparation of hybridization probes. Hybridization probes were prepared as labeled sense and antisense RNA by in vitrotranscription from cDNA templates by using SP6 or T7 RNA polymerase. The coding region of rat TASK-1 (obtained from A. T. Gray, University of California, San Francisco, CA; GenBank accession numberAF031384) (Leonoudakis et al., 1998) was ligated into pcDNA3 (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) using EcoRI and ApaI and linearized with HindIII for transcription using SP6 RNA polymerase to generate antisense probes; the corresponding sense probes were produced by linearizing with EcoRI and transcribing with T7 RNA polymerase. The coding region of rat TASK-3 was prepared by PCR using TASK-3 cDNA as a template (obtained from D. Kim, The Chicago Medical School, Chicago, IL; GenBank accession number AF192366) (Y. Kim et al., 2000) and ligated into pcDNA3 using BamHI andEcoRI. Antisense probes were generated by cutting the resulting construct with HindIII and transcribing with SP6; the cognate sense probes were made by linearizing with EcoRV and transcribing with T7. Transcription was performed in the presence of [α-33P]UTP for preparation of radioactive probes; radiolabeled RNA was separated from unincorporated nucleotides by ethanol precipitation. For nonradioactive in situ hybridization, the Riboprobe System kit (Promega, Madison, WI) was used to incorporate digoxigenin-11-UTP (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) into in vitro transcripts. Probes were purified with ProbeQuant G-50 Micro Columns (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ), and the amount of digoxigenin-11-UTP incorporation was estimated from a dot blot with a dilution series of riboprobe and control RNA (standards from Boehringer Mannheim). Riboprobes were added directly to the prehybridization solution (see below) at concentrations that were similar in spot density to the control RNA (∼20–100 ng/μl).

Hybridization with [33P]-labeled probes. Radioactive in situ hybridization was performed as described previously (Talley et al., 2001). Slide-mounted sections were fixed briefly (5 min) in 4% paraformaldehyde, rinsed repeatedly in PBS, treated successively with glycine (0.2% in PBS) and acetic anhydride (0.25% in 0.1 m triethanolamine, 0.9% saline, pH 8), and dehydrated in a graded series of ethanols and chloroform. Hybridization was performed overnight at 60°C in a buffer of 50% formamide, 4× SSC (1× SSC: 150 mm NaCl and 15 mm sodium citrate, pH 7), 1× Denhardt's solution (0.02% each of Ficoll, polyvinylpyrrolidone, and bovine serum albumin), 10% dextran sulfate, 100 mm DTT, 250 μg/ml yeast tRNA, and 0.5 mg/ml salmon testes DNA. After hybridization, slides were washed through two changes of 4× SSC, treated with RNase A (50 μg/ml), washed again through two changes each of 2× SSC and 0.5× SSC, and finally subjected to a high-stringency wash of 0.1× SSC. Each of these washes lasted 20–30 min. They were performed at 37°C and included 10 mm sodium thiosulphate, with the exception of the high-stringency wash, which was performed at 55°C without sodium thiosulphate.

Non-isotopic in situ hybridization combined with immunohistochemistry. Sections were removed from cryoprotectant solution, rinsed in sterile saline, and placed free-floating into prehybridization mixture at room temperature for 30 min and then at 37°C for 1 hr. The prehybridization mixture consisted of 0.6 m NaCl, 0.1 mTris-Cl, pH 7.5, 0.002 m EDTA, 0.05% NaPPi, 0.5 mg/ml yeast total RNA, 0.05 mg/ml yeast tRNA, 1× Denhardt's BSA, 50% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, 0.05 mg/ml oligo-dA, 10 μm of the four deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 0.5 mg/ml herring sperm DNA, and 10 mm DTT in an aqueous solution. Digoxigenin-labeled probes were added directly to the prehybridization solution, and sections were incubated at 55–60°C for 16–20 hr. Sections were rinsed through decreasing concentrations of salt solutions, treated with RNase A at 37°C, and then subjected to a final high-stringency wash (0.1× SSC at 55°C for 60 min).

Sections were processed for immunochemical detection of digoxigenin with a sheep polyclonal anti-digoxigenin antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Boehringer Mannheim). After incubation in a blocking solution of 10% goat serum for 30 min, sections were incubated in anti-digoxigenin antibody for 16–20 hr at 4°C. After rinsing, the alkaline phosphatase was reacted with nitroblue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate, 4-toluidine salt in a foil-wrapped container. The reaction was monitored periodically under a dissecting microscope and quenched with three 10 min rinses in 0.1 m Tris and 1 mmEDTA, pH 8.5.

After in situ hybridization, sections were processed for immunohistochemical detection of tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH). At the conclusion of the quenching steps (see above), free-floating sections were rinsed in Tris-buffered saline, pH 7.4, and incubated with primary antibody against TPH (1:1000, mouse monoclonal; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 16–20 hr at 4°C in a solution containing 0.1% Triton X-100, 10% goat serum, and 100 mm Tris-buffered saline. Sections were incubated with biotinylated goat-anti-mouse IgG3 (1:200; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and then with avidin-conjugated Cy3 (1:1000; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA), each for 45 min at room temperature with intervening rinses. Sections were mounted onto microscope slides, air dried, and coverslipped with VectaShield (Vector Laboratories).

Control experiments. The probes used for TASK channelin situ hybridization (Sirois et al., 2000; Talley et al., 2000, 2001) and the antibody used for detection of tryptophan hydroxylase (Bayliss et al., 1997) have been characterized extensively. Additional controls performed in the current context included the use of corresponding sense probes, which gave uniformly low levels of nonspecific (background) labeling (see Figs. 1, 2). The patterns of labeling for TASK-1 and TASK-3 obtained with radioactive and non-isotopic cRNA probes were identical. In addition, the distribution of TPH immunoreactivity was exactly as expected for serotonergic neurons (i.e., strong labeling in midline raphe nuclei) (Jacobs and Azmitia, 1992), with no labeling evident in control tissue in which either the primary or secondary antibody was omitted (data not shown).

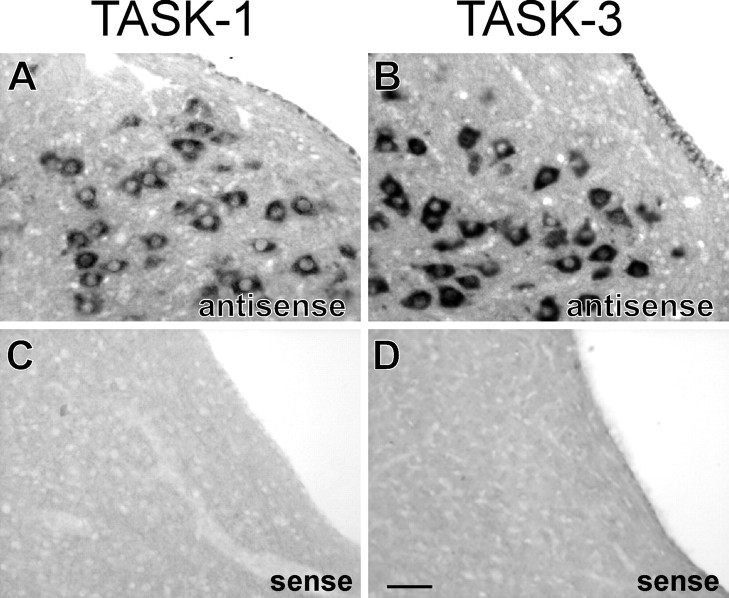

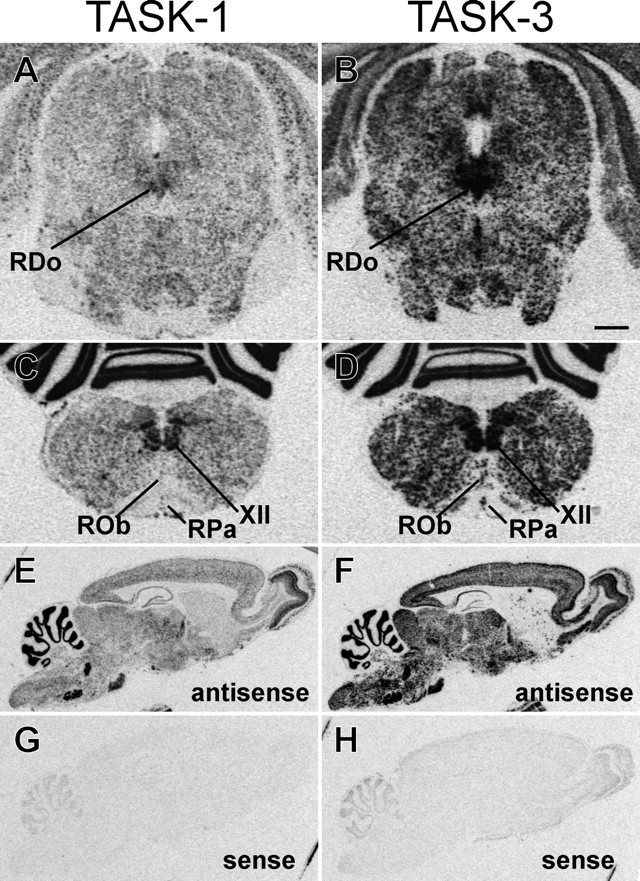

Fig. 1.

Expression of TASK channel transcripts in midline raphe cell groups. In situ hybridization was performed in parallel on sections of rat brainstem using [33P]-labeled RNA probes complementary to TASK-1 and TASK-3. Film autoradiographs from coronal sections of midbrain show moderate levels of TASK-1 expression (A) and high levels of TASK-3 expression (B) in the RDo. In transverse sections from the medulla oblongata, film autoradiographs depict expression of TASK-1 (C) and TASK-3 (D) in the caudal raphe cell groups ROb and RPa. Strong labeling in the hypoglossal motor nuclei (XII) is also apparent. TASK-1 is expressed at lower levels in raphe cell groups than in motoneurons, whereas levels of TASK-3 are more comparable in those two cell types. It also appeared that TASK-1 was expressed at lower levels than TASK-3, although comparisons between probes should be made with caution. Autoradiographs of sagittal rat brain sections from control experiments performed with antisense (E, F) and sense (G, H) probes to TASK-1 (E, G) and TASK-3 (F,H) illustrate differential but overlapping brain distribution of TASK channel transcripts and low levels of background labeling. Scale bar: A–D, 1 mm; E–H, 2.5 mm.

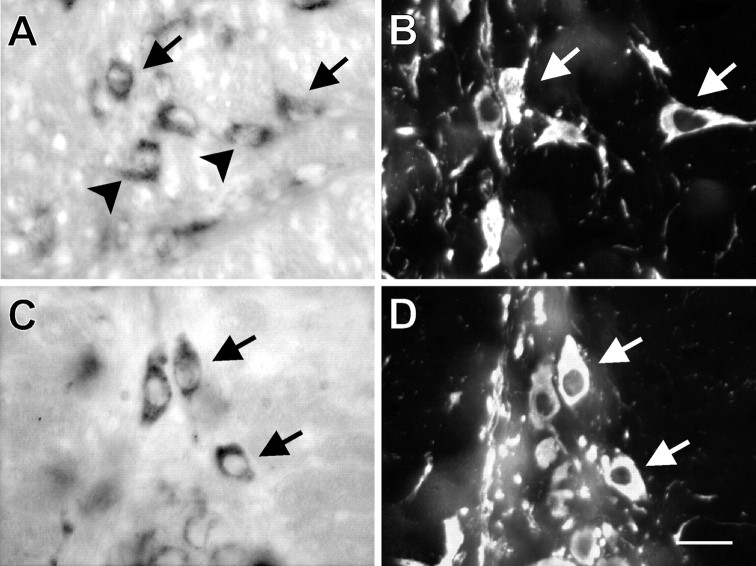

Fig. 2.

Specificity of TASK-3 and TASK-1 labeling using nonradioactive cRNA probes. In situ hybridization with digoxigenin-labeled sense and antisense RNA probes for TASK-1 and TASK-3. Note that high levels of TASK-1 (A) and TASK-3 (B) expression were detected in hypoglossal motoneurons using antisense probes; as expected, there was no labeling in motoneurons in adjacent sections incubated with the corresponding sense probes (C, D). Scale bar, 50 μm.

Brain mapping, quantification, and imaging. All slides from isotopic in situ hybridization experiments were exposed to film (Hyperfilm β-MAX; Amersham Biosciences) for the same length of time (5 d). The resulting autoradiograms were mounted on a light box and imaged using a video camera (CCD-72; Dage-MTI, Michigan City, IN). The same camera settings were used to generate images from each of the different probes. Sections from combined in situhybridization and immunohistochemistry experiments were photographed with color slide film (Fuji Provia 1600; Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan) or black and white film (Kodak TMAX 100; Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). A Nikon (Tokyo, Japan) film scanner at 3000 dpi resolution was used to digitize images for processing in Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). Locations of TPH-immunoreactive (IR) neurons that contain TASK-1 or TASK-3 mRNA were mapped, and cell counts were obtained by using Neurolucida (MicroBrightField, Colchester, VT) and Canvas software (Deneba Software, Miami, FL) in sections containing raphe dorsalis (RDo), magnus (RMg), obscurus (ROb), pallidus (RPa), and the parapyramidal region. Sections were located relative to bregma using landmarks from the atlas of Paxinos and Watson (1997).

Electrophysiology

General preparation. Whole-cell recordings were performed in vitro using brainstem slices, essentially as described previously (Sirois et al., 2000; Talley et al., 2000). Briefly, rats [Sprague Dawley, postnatal day 1 (P1) to P9 for caudal raphe and P15–P29 for dorsal raphe] were anesthetized either by chilling on ice (<P5) or with ketamine–xylazine (as above), and the brainstem was removed after decapitation. Transverse slices (200 μm) were cut with a microslicer (DSK-1000; Dosaka) in an ice-cold solution containing (in mm): 260 sucrose, 3 KCl, 5 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, and 1 kynurenic acid. Slices were incubated for ∼1 hr at 37°C in a solution consisting of (in mm): 130 NaCl, 3 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, and 10 glucose. Slices were maintained in this incubation solution at room temperature (22–25°C) for periods up to 6 hr. Cutting and incubation solutions were bubbled continuously with 95% O2 and 5% CO2.

Recording. Slices were submerged in a chamber mounted on a fixed-stage microscope (Axioskop FS; Zeiss, Thornwood, NY), perfused continuously (∼2 ml/min), and visualized using differential interference contrast optics. Dorsal and caudal raphe neurons were identified visually by their location ventral to the aqueduct or along the midline, respectively, and characterized electrophysiologically by their response to serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) (Jacobs and Azmitia, 1992; Penington et al., 1993; Bayliss et al., 1997). Electrical recordings were performed at room temperature in a bath solution composed of (in mm): 130 NaCl, 3 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose, with pH adjusted using either NaOH or HCl. For voltage-clamp recordings, bath solutions contained tetrodotoxin (0.75–1 μm); for current-clamp recordings, slices were perfused in a bath solution containing bicuculline (10 μm), strychnine (30 μm), and CNQX (10 μm).

Patch electrodes were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) on a two-stage puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) to a DC resistance of ∼3–5 MΩ when filled with internal solution containing (in mm): 120 KCH3SO3, 4 NaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 0.5 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 EGTA, 3 Mg-ATP, and 0.3 GTP-Tris, pH 7.2; electrode tips were coated with Sylgard 184 (Dow Corning, Midland, MI). 5-HT was applied at bath concentrations ranging from 2 to 100 μm. To augment 5-HT current amplitude in caudal raphe neurons, the concentration of KCl was increased to 6 mm during 5-HT application in some experiments (Penington et al., 1993). Osmolarity was maintained by reducing the concentration of NaCl correspondingly. All solutions were bubbled with a room air gas mixture (21%O2/balance N2) and perfused at ∼2 ml/min; solutions containing halothane were equilibrated using a calibrated vaporizer (Ohmeda, Helsinki, Finland) and covered tightly with parafilm to prevent loss of anesthetic to the atmosphere. Aqueous concentrations of anesthetic solutions were determined by gas chromatographic analysis from samples collected at the point of presentation to the preparation (Sirois et al., 2000).

Data acquisition and analysis. Voltage commands were applied via an Axopatch 200B patch-clamp amplifier and digitized with a Digidata 1200 analog-to-digital converter (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA). Cells were held at −60 mV, and membrane currents in response to a hyperpolarizing ramp (−60 to −130 mV) were recorded at a constant interval (0.1 Hz). Current–voltage relationships were determined at steady state for various treatment protocols by hyperpolarizing the cell in −10 mV steps (to −130 mV). Currents were filtered at 2 kHz with a four-pole, low-pass Bessel filter. Series resistance was typically <20 MΩ and was compensated by 65–70%. A liquid junction potential of −10 mV was corrected offline. Data analysis was performed using the pClamp suite of programs (Axon Instruments). Statistical analysis of data were performed using Student's t tests; significance was accepted ifp < 0.05.

RESULTS

Expression of TASK channel transcripts in midline brainstem neurons of rat

We determined sites of TASK channel expression in midline structures of the rat brainstem using in situ hybridization with [33P]-labeled antisense RNA probes. Images from these experiments are shown in Figure1, together with control data from sagittal sections of rat brain hybridized with sense and antisense probes (Fig. 1E–H), which illustrate the low level of background labeling obtained in these experiments. In film autoradiographs of coronal sections through the RDo, TASK-1 mRNA was detected at moderate levels (Fig. 1A), whereas TASK-3 expression was found at high levels (Fig. 1B). In more caudal brainstem sections, film autoradiographs reveal expression of TASK-1 (Fig. 1C) and TASK-3 (Fig. 1D) along the midline, in structures corresponding to ROb and RPa. TASK-1 was expressed at much lower levels in raphe neurons than in the hypoglossal motoneurons that are apparent in the same sections, whereas expression of TASK-3 was more similar in the two cell groups, although at slightly higher levels in motoneurons. In addition, if one assumes similar hybridization efficiencies for the two probes, it appeared that TASK-3 was expressed at higher levels than TASK-1 in both raphe neurons and motoneurons.

Expression of TASK channel transcripts in brainstem serotonergic neurons

The major serotonergic cell groups in the brain are coextensive with midline brainstem raphe nuclei, although a substantial proportion of raphe cells are not serotonergic (Jacobs and Azmitia, 1992). To determine whether TASK channel transcripts are expressed in serotonergic raphe neurons, we used nonradioactive in situhybridization with digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes for TASK channels combined with immunohistochemical localization of tryptophan hydroxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme in serotonin biosynthesis. In control experiments, prominent alkaline phosphatase reaction product was observed in motoneurons from tissue incubated with digoxigenin-labeled TASK channel antisense riboprobes but completely absent in control tissue incubated with sense probes (Fig.2). Moreover, the distribution of TASK-expressing brainstem neurons obtained using nonradioactive probes conformed to previous in situ hybridization examinations (Talley et al., 2000, 2001), again with stronger labeling for TASK-3 than for TASK-1. In addition, the localization of TPH immunoreactivity was exactly as expected for serotonergic neurons (i.e., strong labeling in midline raphe nuclei) (Jacobs and Azmitia, 1992).

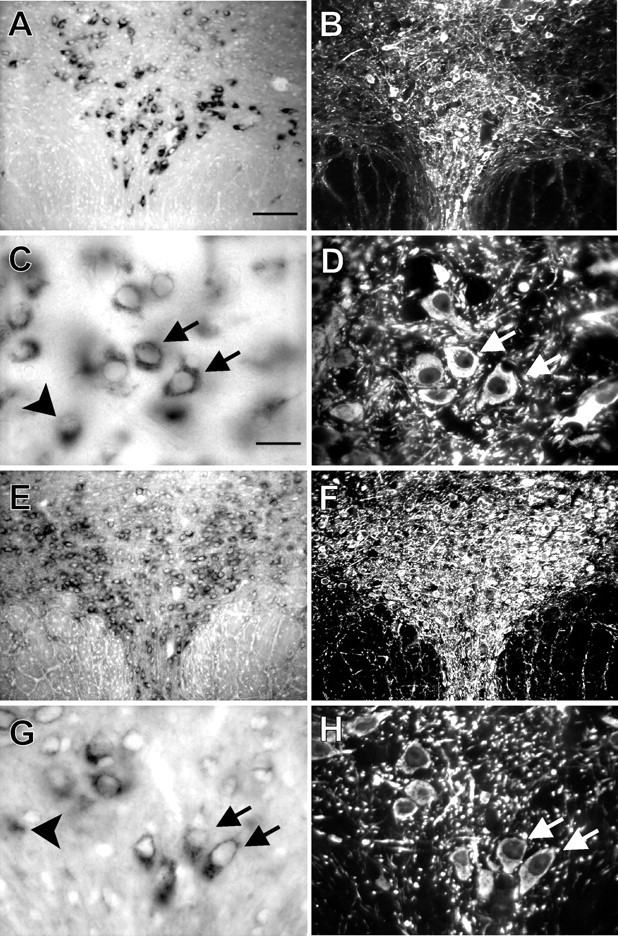

Combined labeling for TASK channel transcripts and TPH in the midbrain dorsal raphe nucleus is shown in Figure3. Low-power photomicrographs reveal labeling in RDo for TASK-1 (Fig. 3A) and TASK-3 mRNA (Fig.3E), with high correspondence to the region of TPH immunoreactivity (Fig.3B,F). At higher magnification, numerous individual cells were evident that contain TASK channel transcripts (Fig. 3C,G) and TPH immunoreactivity (Fig.3D,H), and it was clear that, in most cases, TASK mRNA was coexpressed in the TPH-IR neurons (see arrows), indicating that serotonergic RDo neurons express TASK channel transcripts. Labeling for TASK was seen in a few nonserotonergic neurons (arrowheads), but TPH-IR cells that did not contain TASK mRNA were encountered only infrequently. Colocalization of TASK channel mRNA in serotonergic neurons was not limited to the dorsal raphe but was also evident along the midline of the caudal brainstem within the ROb and RPa (Fig.4). High-power photomicrographs show expression of TASK-1 in TPH-IR cells of ROb (Fig.4A,B) and TASK-3 in TPH-IR cells of RPa (Fig. 4C,D); it is again clear that hybridization signal for TASK mRNA was found in many TPH-IR cells (arrows) and in some apparently nonserotonergic cells (arrowheads).

Fig. 3.

TASK-1 and TASK-3 transcripts are expressed in TPH-IR neurons of the dorsal raphe. In situhybridization with digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes complementary to TASK-1 and TASK-3 was combined with immunohistochemistry for TPH on coronal sections of rat midbrain at the level of RDo. Low-powered bright-field images show labeling for TASK-1 (A) and TASK-3 (E); fluorescence photomicrographs of the same sections reveal immunostaining for TPH (B,F). Note the strong correspondence in localization of TASK-expressing and TPH-immunoreactive (i.e., serotonergic) cells. High-magnification bright-field images show individual TASK-1-labeled neurons (C) and TASK-3-labeled neurons (G); immunofluorescence photomicrographs identify TPH-IR neurons in the same sections (D, H). It is clear that most serotonergic neurons express TASK channels (arrows); some TASK-expressing neurons that are not noticeably TPH-IR were also apparent (see arrowheads in C andG). Scale bars: A, 100 μm;C, 25 μm. Sections in A–D were taken from a slightly different rostrocaudal level than those inE–H.

Fig. 4.

TASK-1 and TASK-3 transcripts are colocalized in serotonergic neurons of the caudal raphe. In situhybridization with digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes complementary to TASK-1 and TASK-3 was combined with immunohistochemistry for TPH on coronal sections of rat brainstem. A, C, TASK-1-expressing neurons of ROb and TASK-3-expressing neurons of RPa are shown in bright-field photomicrographs. B,D, Immunofluorescence photomicrographs of the corresponding sections shows the location of TPH-IR neurons. Many serotonergic neurons contain TASK channel transcripts (arrows); TASK channel expression was also observed in TPH-IR negative neurons (arrowheads). Scale bar, 25 μm.

To quantify these results, we mapped the distribution of TASK channel transcripts within serotonergic raphe neurons. Sections were examined at levels that contain RDo, RMg, ROb, RPa, and the parapyramidal areas; these maps were used to determine the percentage of TPH-IR neurons in which TASK-1 or TASK-3 transcripts were colocalized (Table1). Combining data obtained from all raphe nuclei, cell counts revealed that the majority of the TPH-IR cells contained TASK-1 (73%) or TASK-3 (81%) mRNA. A similar percentage of TPH-IR neurons within the RDo contained transcripts for TASK-1 or TASK-3. In the medulla, it appeared that a higher percentage of TPH-IR cells contained TASK-3 than TASK-1, although this may partly reflect difficulties with detection of TASK-1 as a result of its apparently lower expression.

Table 1.

Colocalization of TASK-1 or TASK-3 mRNA within TPH-IR neurons

| Brain region | Percentage of TPH-IR neurons that express TASK-1 | Percentage of TPH-IR neurons that express TASK-3 |

|---|---|---|

| Parapyramidal region | 66.0 ± 0.5 (n = 12) | 79.2 ± 0.6 (n = 11) |

| Raphe pallidus | 66.7 ± 0.6 (n = 12) | 85.3 ± 1.0 (n = 11) |

| Raphe obscurus | 70.1 ± 0.6 (n = 8) | 95.6 ± 2.0 (n = 7) |

| Raphe magnus | 70.6 ± 0.9 (n = 4) | 72.6 ± 0.8 (n = 4) |

| Raphe dorsalis | 85.5 ± 1.1 (n = 4) | 87.4 ± 1.1 (n = 4) |

n, Number of sections examined.

Dorsal raphe neurons express a pH- and halothane-sensitive K+ conductance with properties of TASK channels

TASK-1 and TASK-3 channels generate instantaneous, open-rectifier K+ currents that are sensitive to extracellular pH and to volatile anesthetics (Lesage and Lazdunski, 2000; Goldstein et al., 2001; Patel and Honore, 2001). Given that TASK-1 and TASK-3 transcripts are expressed in serotonergic raphe neurons, we tested whether those cells exhibit pH- and anesthetic-sensitive currents with the properties expected of TASK channels. To this end, whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were obtained in brainstem slices from neurons in RDo (Figs.5, 6). All cells included in this study generated an inwardly rectifying K+ current in response to bath application of 5-HT, a response characteristic of serotonergic raphe neurons (Jacobs and Azmitia, 1992; Penington et al., 1993; Bayliss et al., 1997). In the representative cell of Figure 5A, this effect is evident as a 5-HT-induced outward shift in current at the holding potential of −60 mV.

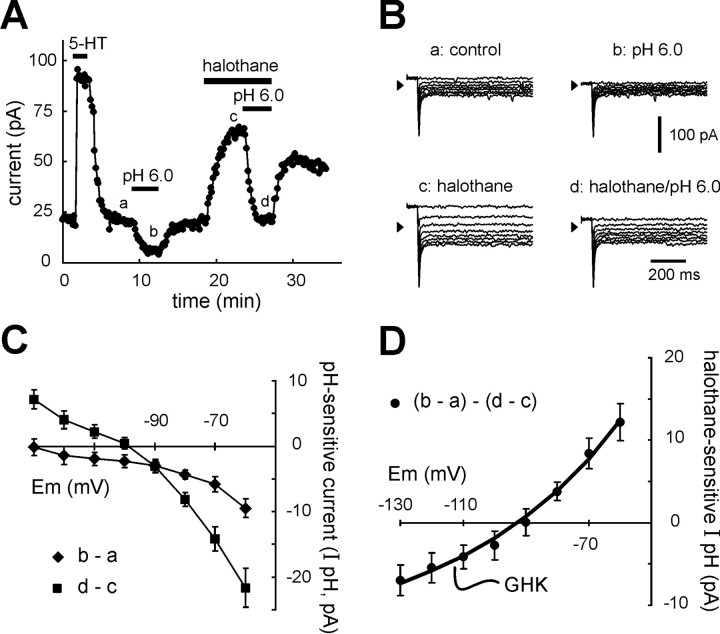

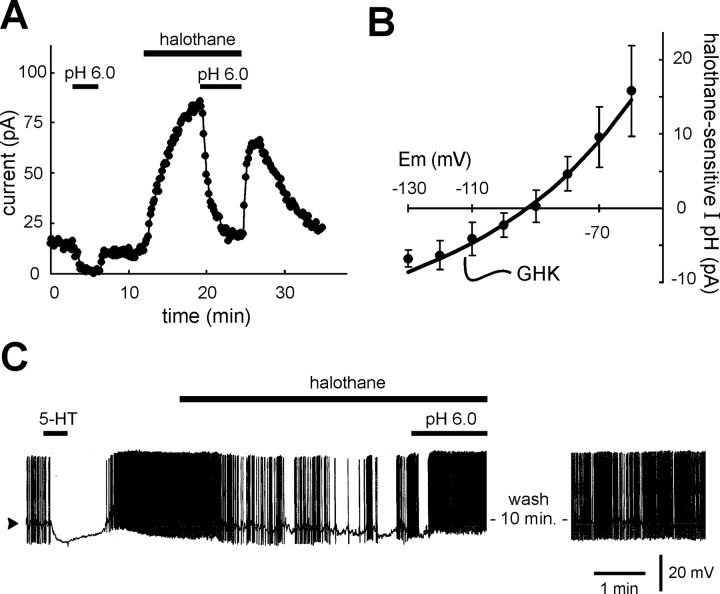

Fig. 5.

Dorsal raphe neurons express a pH- and halothane-sensitive K+ conductance with properties of TASK channels. Dorsal raphe neurons were recorded under whole-cell voltage clamp in slices of rat midbrain. A, As expected for serotonergic dorsal raphe neurons, 5-HT (100 μm) evoked an outward shift in membrane current at holding potential of −60 mV. Extracellular acidification (from pH 7.3 to pH 6.0) evoked an inward shift in holding current. After wash into control pH 7.3 solution, halothane (1.25 mm) evoked an outward shift in current, and, in the presence of halothane, the current shift induced by reacidifying the bath solution was enhanced in amplitude.B, Examples of current responses to incrementing voltage steps (Δ −10 mV) from −60 mV that were used to constructI–V relationships (taken at times corresponding to those indicated in A); note that currents were essentially completely activated before the end of the capacitive transient (i.e., they were instantaneous) and were non-inactivating.C, Averaged I–V relationships of pH-sensitive currents (diamonds) were derived by subtracting currents recorded in the acidified bath (b) from those obtained under control conditions (a); the pH-sensitive current in the presence of halothane (squares) was likewise derived by subtracting currents recorded before (c) and after (d) bath acidification during continued exposure to halothane (±SEM; n = 14). D, Subtracting pH-sensitive currents obtained in the presence of halothane from those obtained under control conditions yielded the averagedI–V relationship of the joint halothane- and pH-sensitive component of dorsal raphe current (±SEM;n = 14). Those I–V data were well fitted to the GHK equation, consistent with involvement of an open-rectifier TASK-like current.

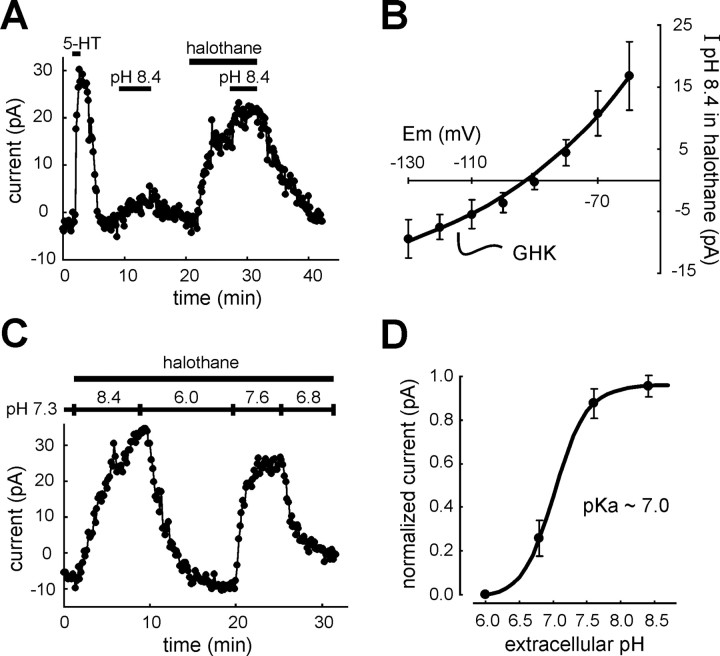

Fig. 6.

The pH- and anesthetic-sensitive current in RDo has a pH sensitivity intermediate between TASK-1 and TASK-3.A, Voltage-clamp recording in a serotonergic dorsal raphe neuron. 5-HT (100 μm) induced an outward shift in membrane current at −60 mV that is characteristic of serotonergic RDo neurons. Bath alkalization (from pH 7.3 to pH 8.4) evoked an outward current under control conditions and in the presence of halothane (1.25 mm). B, Averaged data depicting theI–V relationship of the current evoked by alkalized solution in halothane; these data were well fitted with the GHK constant field equation (±SEM; n = 11).C, To determine the pH sensitivity of currents in RDo neurons, the extracellular pH was varied between pH 6.0 and pH 8.4 in the continued presence of halothane (to enhance the amplitude of pH-sensitive currents). D, For each cell, currents measured under these pH conditions were normalized to the maximum and minimum current, and those normalized data were fitted to a logistic equation that predicted a pK of ∼7.0 for the pH- and halothane-sensitive dorsal raphe current. This value is intermediate between those measured for cloned rTASK-1 and rTASK-3 (∼7.4 and 6.7, respectively).

In these 5-HT-responsive, and thus presumably serotonergic RDo cells, we characterized currents that were sensitive to bath acidification and to halothane, following the protocol illustrated in Figure5A. Bath acidification (from pH 7.3 to pH 6.0) produced a small but reproducible inward shift in holding current. Subsequent application of halothane (1.25 mm) at pH 7.3 evoked an outward current, and, in the continued presence of halothane, bath acidification again induced an inward current shift, but that current was now enhanced in amplitude. Every RDo neuron tested with this protocol showed an enhanced pH-sensitive current in the presence of halothane (n = 14). Averaged data from these cells revealed that the inward shift in holding current obtained during bath acidification was −9.9 ± 1.3 pA under control conditions and −25.6 ± 2.6 pA in the presence of halothane (p < 0.001); the outward current induced by halothane itself was 27.7 ± 3.8 pA.

Current responses to hyperpolarizing voltage steps obtained under these conditions (at points corresponding to those indicated bylowercase letters in Fig. 5A) are depicted in Figure 5B. Note that currents were fully activated within the time needed to charge the membrane and note also the absence of any significant time-dependent current relaxation in these records. Subtracting control currents from those obtained in pH 6.0 yielded the pH-sensitive current; those subtracted currents were obtained in a group of RDo neurons to determine the averaged I–Vrelationship of the pH-sensitive current (Fig. 5C,diamonds). This averaged I–V relationship was associated with a negative slope, consistent with inhibition of a K+ conductance. However, it did not reverse over the voltage range tested, suggesting that additional conductances likely contribute to pH-sensitive currents in RDo neurons. A similar subtraction procedure was used to determine theI–V relationship of the pH-sensitive current obtained in the presence of halothane (Fig. 5C, squares); under these conditions, the pH-sensitive current was associated with a more prominent decrease in conductance. As shown in Figure5D, subtraction of pH-sensitive currents in the presence of halothane from those in the absence of halothane yielded the component of pH-sensitive current that was enhanced by halothane. TheI–V relationship of this subtracted current reversed nearEK and was well fitted by the GHK constant field equation, indicating that like TASK currents, the joint halothane- and pH-sensitive current in RDo displayed properties expected of an open rectifier K+conductance.

TASK-1 and TASK-3 contribute to the dorsal raphe pH- and halothane-sensitive K+ current

We found expression of both TASK-1 and TASK-3 channel mRNA in serotonergic raphe neurons, with apparently higher expression of TASK-3. Although these TASK channels are each modulated by extracellular pH, they exhibit a different range of sensitivity; TASK-1 is activated strongly by bath alkalization from pH 7.3 (Duprat et al., 1997; Leonoudakis et al., 1998; Y. Kim et al., 1999; Lopes et al., 2000; Talley et al., 2000), whereas TASK-3 is nearly fully activated at pH 7.3, and additional alkalization has little effect on TASK-3 currents (Y. Kim et al., 2000; Rajan et al., 2000; Meadows and Randall, 2001). As shown in Figure 6A, and consistent with a contribution of TASK-1 to the pH- and anesthetic-sensitive current in RDo neurons, we found an outward shift in holding current when the pH of the bath solution was increased from 7.3 to 8.4, both under control conditions (6.4 ± 3.3 pA) and in the presence of halothane (16.2 ± 5.8 pA; n = 11). These effects were associated with an increase in conductance, and I–Vrelationships of the current induced by bath alkalization in the presence of halothane displayed properties consistent with activation of an open-rectifier K+ conductance (Fig.6B).

To characterize further the pH sensitivity of the raphe neuronal current, we varied extracellular pH in the continued presence of halothane (i.e., under conditions that maximize the contribution of TASK-like currents to the pH response). As shown in Figure6C, currents were measured in bath solutions titrated to four different pH values in the presence of halothane. Currents were normalized, and a pH curve was generated by a logistic fit to the data (Fig. 6D). The calculated pK for RDo neurons was ∼7.0, intermediate between that reported for rTASK-1 (pK ∼7.4) (Talley et al., 2000) and rTASK-3 (pK ∼6.7) (Y. Kim et al., 2000), suggesting that both channels contribute to the pH- and anesthetic-sensitive current in RDo neurons.

The pH- and anesthetic-sensitive current in caudal raphe neurons has properties of an open-rectifier K+conductance

In addition to TASK-expressing cells in the RDo, we found that a high percentage of medullary serotonergic neurons express TASK channel transcripts. Accumulating evidence indicates that firing activity of serotonergic caudal raphe neurons is modulated by physiological changes in pH (Richerson, 1995; Wang and Richerson, 2000; Wang et al., 2001). Therefore, we tested whether TASK-like currents might also contribute to the pH sensitivity of medullary raphe neurons.

We characterized pH- and anesthetic-sensitive currents in caudal raphe neurons using the same protocol used in RDo neurons. Again, our analysis was limited to those cells that responded to 5-HT with an increase in an inwardly rectifying K+current (data not shown) typical of serotonergic neurons (Bayliss et al., 1997). As exemplified in the records of Figure7, the response of caudal raphe neurons to bath acidification and halothane was essentially identical to that described above for RDo (compare with Fig. 5); acidification produced an inward shift in holding current that was enhanced in the presence of halothane. All caudal raphe neurons tested with this protocol displayed an enhanced pH-sensitive current in the presence of halothane (n = 7). The current induced by bath acidification averaged −8.5 ± 2.0 pA under control conditions and −26.0 ± 8.3 pA in the presence of halothane (p < 0.05), which itself induced a 32.5 ± 9.2 pA current in those same cells. As with RDo neurons, the I–V relationships of pH- and halothane-sensitive current in caudal raphe neurons displayed properties consistent with involvement of an openly rectifying K+ channel, as illustrated in Figure7B. This suggests that TASK channels contribute also to the pH sensitivity of serotonergic caudal raphe neurons.

Fig. 7.

Caudal raphe neurons also express a pH- and halothane-sensitive open-rectifier K+ current.A, Voltage-clamp recording of membrane current in a representative caudal raphe cell held at −60 mV. Extracellular acidification evoked an inward shift in holding current that reversed when the cell was returned to the control bath solution. Addition of halothane (1.25 mm) to the bath then induced an outward current, and, in the continued presence of halothane, the inward shift in current associated with bath acidification was increased in amplitude. This cell responded to a subsequent bath application of 5-HT (2 μm) with an outward current (data not shown) characteristic of serotonergic caudal raphe neurons. B, The averaged I–V relationship of the pH- and halothane-sensitive current (±SEM; n = 7) was determined from cells tested with this same protocol using the subtraction procedure described above (see Fig. 5); these data were well fitted with the GHK equation, indicating that the pH- and halothane-sensitive current in caudal raphe neurons is an open rectifier, as expected for TASK channel currents. C, Current-clamp recording of membrane potential in a spontaneously firing caudal raphe neuron. As expected for serotonergic raphe neurons, the cell hyperpolarized by ∼10 mV and ceased its spike discharge when exposed to 5-HT (2 μm). After recovery from 5-HT, a clinically relevant concentration of halothane (0.35 mm) reduced firing in this cell; the effect on firing was reversed by bath acidification (to pH 6.0) and recovered to near control levels after wash of halothane in a neutral bath solution (pH 7.3). The current-clamp recording was obtained in a bath solution containing bicuculline (10 μm), strychnine (10 μm), and CNQX (10 μm). Arrowhead indicates −60 mV; action potentials were truncated by the chart recorder.

Halothane depresses raphe neuronal firing at clinically relevant concentrations

Our data indicate that the halothane-sensitive current in raphe neurons is sensitive to pH in a physiological range, with a pK intermediate between that of cloned TASK-1 and TASK-3 channels (Fig.6), and previous reports indicate that spike discharge in caudal raphe neurons is steeply sensitive to physiological changes in pH (Richerson, 1995; Wang and Richerson, 2000; Wang et al., 2001). It is also clear that cloned TASK channels are activated by anesthetics in a clinically relevant concentration range (Patel et al., 1999; Meadows and Randall, 2001). Therefore, we tested whether the firing behavior of raphe neurons is modulated by halothane at concentrations appropriate for clinical anesthesia. As depicted in the records from a 5-HT-responsive caudal raphe neuron in Figure 7C, a clinically relevant concentration of halothane (0.35 mm) caused membrane hyperpolarization and a marked decrease in spontaneous firing. This effect was reversed by acidifying the bath despite the continued presence of halothane, as expected if it were mediated by TASK channels (Sirois et al., 2000). Halothane depressed spike discharge in all dorsal raphe neurons (n = 4) and in all but one caudal raphe neuron (n = 10 of 11) tested at this concentration; on average, halothane decreased firing from 0.5 ± 0.1 to 0.1 ± 0.1 Hz in dorsal raphe neurons (p < 0.005) and from 0.5 ± 0.1 to 0.3 ± 0.1 Hz in caudal raphe neurons (p < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

We combined molecular neuroanatomy and cellular electrophysiology to provide evidence that the pH- and anesthetic-sensitive two-pore-domain K+ channels, TASK-1 and TASK-3, are functionally expressed in serotonergic raphe neurons. Thus, by using in situ hybridization, we showed that TASK-1 and TASK-3 transcripts are expressed in brainstem raphe nuclei; within the raphe, immunohistochemical detection of tryptophan hydroxylase in TASK-expressing neurons demonstrated that both TASK-1 and TASK-3 are localized within the majority of serotonergic dorsal and caudal raphe neurons (∼70–90%). Whole-cell recordings of 5-HT-responsive, presumably serotonergic, raphe neurons revealed that those cells express a K+ conductance with properties diagnostic of TASK channels and distinct from all other channels cloned to date (i.e., they display an instantaneous open-rectifier K+ current that is jointly sensitive to pH and inhalational anesthetics). Because both TASK-1 and TASK-3 transcripts were found in a high percentage of serotonergic raphe neurons, it is certain that they must be coexpressed in many of those cells. Accordingly, the pH sensitivity of the raphe neuronal TASK-like current (pK∼7.0) was intermediate between TASK-1 and TASK-3, consistent with contributions from both channels. These data suggest that modulation of TASK channels by extracellular protons and by anesthetics may contribute to neurophysiological mechanisms related to brain pH homeostasis and to clinical effects of inhalational anesthetics mediated by serotonergic raphe neurons.

Methodological considerations

Throughout most of these studies, we used pH conditions and anesthetic concentrations designed to maximize current amplitudes, and this may have activated additional processes that would not be obtained under physiologically or clinically appropriate conditions. However, it is well known that recombinant TASK channels are sharply sensitive to extracellular pH in the physiological range (Duprat et al., 1997; D.Kim et al., 1998; Leonoudakis et al., 1998; Y. Kim et al., 1999, 2000;Lopes et al., 2000; Rajan et al., 2000; Talley et al., 2000; Meadows and Randall, 2001), and, with a pK∼7.0 as we described, the pH-sensitivity of the raphe neuronal TASK-like current indicates that it will be regulated by physiological changes in pH. Likewise, it is clear that TASK channels are sensitive to anesthetics at clinically relevant concentrations (Patel et al., 1999; Meadows and Randall, 2001), and, accordingly, we found that halothane induced a pH-sensitive decrease in raphe neuronal excitability at clinically appropriate concentrations. Although there is no evidence to date for the existence of native heteromeric TASK-1/TASK-3 channels, such as one might expect from their coexpression in serotonergic raphe neurons, we found that concatenated TASK-1/TASK-3 constructs express channels that also respond to extracellular pH and inhalation anesthetics in a physiologically and clinically appropriate range (Talley and Bayliss, unpublished observations).

The protocol we used to isolate a time-independent, open-rectifier TASK-like current took advantage of the joint pH and anesthetic sensitivity of TASK channels. Thus, a contribution of TASK channels to raphe neuronal pH-sensitive currents was readily revealed in the presence of halothane, under conditions when TASK currents were enhanced. In addition, although I–V relationships of the baseline pH current in the absence of anesthetic implied involvement of multiple conductances, the overall decrease in conductance associated with that baseline acid-sensitive current suggests a contribution from inhibition of a background K+ conductance. Moreover, because TASK channels are known to impart a constitutive background K+ conductance in all contexts examined to date (Duprat et al., 1997; D. Kim et al., 1998; Leonoudakis et al., 1998; Y. Kim et al., 1999, 2000; Lopes et al., 2000; Rajan et al., 2000; Talley et al., 2000; Meadows and Randall, 2001), it seems likely that they would also represent a component of the background pH-sensitive current in raphe neurons. Therefore, our data support the conclusion that upmodulation and downmodulation of background TASK channel activity by physiological changes in extracellular pH and by clinically relevant anesthetic concentrations will contribute to dynamic regulation of serotonergic neuronal excitability.

Physiological relevance of a pH-sensitive background K+ current in serotonergic raphe neurons

The physiological relevance of the intrinsic pH sensitivity of serotonergic raphe neurons, including that conferred by TASK channels, remains to be established. In this respect, two important neural reflexes are evoked when brain pH is decreased by hypercapnia: (1) enhanced respiratory output, which serves as a homeostatic mechanism to correct changes in brain pH (Nattie, 1999); and (2) behavioral arousal, which serves a protective function when breathing is excessively depressed during sleep (Phillipson and Bowes, 1986; Davidson Ward and Keens, 1992). These are particularly interesting in the current context because serotonergic raphe neurons are implicated in both chemical control of respiration (Richerson, 1995; Nattie, 1999) and arousal mechanisms (Jacobs and Azmitia, 1992).

There is a growing literature implicating medullary serotonergic neurons of the caudal raphe as a site for respiratory chemosensitivity (for review, see Richerson, 1998; Nattie, 1999); central respiratory chemoreceptors sense changes in brain pH and/or CO2 and adjust the level of excitatory drive to brainstem centers that control breathing (and thus, pH and pCO2) (Nattie, 1999). In vitrostudies, including the present work, indicate that serotonergic caudal raphe neurons are stimulated by changes in pH and/or CO2 (Richerson, 1995; Wang and Richerson, 2000;Wang et al., 2001), and, because local acidification of the raphe region enhances respiratory output in vivo (Bernard et al., 1996), it has been proposed that these cells may indeed provide a locus for central respiratory chemoreception (Richerson, 1998; Nattie, 1999). The ionic mechanisms responsible for pH sensitivity of medullary raphe neurons have not been determined. A brief report suggests that a nonselective cationic conductance contributes to pH-sensitive currents in serotonergic raphe neurons (Tiwari et al., 2000). The present data are consistent with this previous work insofar as they suggest that multiple ionic mechanisms are involved with responses to pH in medullary raphe neurons. In addition, our work implicates TASK channels specifically as molecular substrates for chemosensitivity of serotonergic raphe neurons, and by extension, for central respiratory chemosensitivity.

It is also noteworthy in this respect that TASK channels contribute to a pH-sensitive increase in excitability in locus coeruleus (LC) neurons (Sirois et al., 2000), another candidate region for central respiratory chemosensitivity (Nattie, 1999; Ballantyne and Scheid, 2000), and in carotid body chemoreceptors, which provide afferent input related to arterial pH to medullary respiratory centers from the periphery (Buckler et al., 2000). Moreover, a direct pH-dependent increase in excitability is attributed to TASK channels in respiratory-related motoneurons (Talley et al., 2000), which ultimately convey central respiratory drive to the muscles of breathing. Thus, the pH sensitivity of TASK channels may be exploited at multiple levels to monitor changes in prevailing acid-base status for purposes of homeostatic regulation of breathing. Of course, it is likely that other pH-sensitive processes in different brain regions contribute also to pH-dependent regulation of breathing (Nattie, 1999).

To date, a role for RDo neurons in regulating respiratory output in response to changes in brain pH has not been suggested, although it is known that a population of RDo neurons increase their firing in response to hypercapnic challenge in vivo (Veasey et al., 1997). Unlike caudal raphe neurons, which project primarily to brainstem and spinal neurons, the efferent targets of RDo neurons are primarily cell groups in rostral brain regions, and, accordingly, RDo neurons are thought to participate in a number of higher-order functions (Jacobs and Azmitia, 1992). The activity of RDo neuronsin vivo is tightly coupled to sleep–wake states, an observation that has led to the suggestion that these cells have a key role in behavioral arousal (Jacobs and Azmitia, 1992). Our data indicate that modulation of TASK channels by extracellular hydrogen ions in the RDo contributes to pH-dependent effects on excitability in these neurons, suggesting that this could serve to regulate arousal state in a pH-dependent manner. Interestingly, the LC is another region strongly implicated in control of arousal (Aston-Jones and Bloom, 1981;Aston-Jones et al., 1991), and we found that TASK channels also contribute to increased LC neuron excitability by extracellular acidification (Sirois et al., 2000). A pH-dependent influence of TASK channels on arousal, mediated by RDo and LC neurons, may be particularly important when ventilation becomes excessively depressed during sleep and when the ensuing hypercapnia provokes the waking response necessary to reinstate appropriate levels of ventilation (Phillipson and Bowes, 1986; Davidson Ward and Keens, 1992). Activation of this arousal mechanism is responsible, at least in part, for sleep disturbances associated with obstructive apneas (Horner, 1996), and failure of this waking reflex in neonates may be a contributing factor to sudden infant death syndrome (Hunt, 1992; Richerson, 1997).

Clinical relevance of an anesthetic-sensitive background K+ current in serotonergic raphe neurons

TASK channels are activated by inhalation anesthetics at concentrations that are entirely appropriate for clinically relevant anesthetic effects (Patel et al., 1999; Meadows and Randall, 2001). Our results indicate that halothane activates a TASK-like current in serotonergic raphe neurons, an effect that will drive membrane potential toward more hyperpolarized potentials and decrease activity during anesthesia. At least two main effects always accompany the clinical state of general anesthesia: immobilization and loss of consciousness (Eger, 1993). We suggest that anesthetic modulation of TASK channels in raphe neurons could conceivably contribute to both of these effects.

First, serotonergic medullary raphe neurons project to brainstem motor nuclei and the spinal cord ventral horn, in which 5-HT and coexpressed neuropeptides exert direct facilitatory effects on motoneurons (Rekling et al., 2000). Inhibition of raphe neurons by anesthetic activation of TASK channels will decrease release of these raphe neurotransmitters and, by disfacilitation, depress motoneuronal excitability. These effects would be supported further by anesthetic activation of TASK channels in LC (Sirois et al., 2000), which would similarly decrease facilitating effects of noradrenergic inputs onto motoneurons (Rekling et al., 2000), and also by direct effects of anesthetics acting on TASK channels in motoneurons themselves (Sirois et al., 2000). Thus, activation of TASK channels at a number of central sites may contribute to immobilizing effects of anesthetics.

As mentioned above, RDo neurons have prominent projections to rostral brain regions and a highly state-dependent firing pattern that suggests a role in behavioral arousal (Jacobs and Azmitia, 1992). Thus, a decrease in activity of these neurons mediated by TASK channels could contribute to sleep-inducing effects of anesthetics, a role we suggested previously for the TASK-expressing LC neurons (Sirois et al., 2000) that are also implicated in control of arousal (Aston-Jones and Bloom, 1981; Aston-Jones et al., 1991). Of course, direct effects of anesthetics on other neurons expressing TASK channels (e.g., thalamic and cortical neurons; Talley et al., 2001) could contribute to these and other clinically important actions of the drugs.

In summary, we suggest that expression of TASK channels contributes to the pH sensitivity of serotonergic raphe neurons and thus to respiratory and arousal reflexes associated with hypercapnia and/or acidosis (Richerson, 1998; Nattie, 1999). Activation of TASK channels in these neurons may also contribute to clinically important actions of volatile anesthetics, such as immobilization and sleep induction. Furthermore, opposing regulation of TASK channel activity by acidosis and anesthetics in serotonergic raphe neurons provides a potential mechanism that could account for the well known diminished ventilatory responses to respiratory acidosis (i.e., respiratory depression) during inhalational anesthesia (Pavlin and Hornbein, 1986). These speculations are potentially testable in genetically altered mice because mutations that disrupt either pH (Y. Kim et al., 2000; Rajan et al., 2000; Lopes et al., 2001) or anesthetic modulation (Patel et al., 1999) of otherwise normal TASK channels have been identified.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants F32HL10271 (J.E.S.), F31MH12091 (E.M.T.), HL28785 (P.G.G.), and NS33583 (D.A.B.). We thank Drs. R. L. Stornetta and A. M. Schreihofer for help with the dual-labeling procedures and Dr. C. Lynch for helpful discussions. We also thank Drs. A. T. Gray and D. Kim for gifts of TASK channel cDNAs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aston-Jones G, Bloom FE. Activity of norepinephrine-containing locus coeruleus neurons in behaving rats anticipates fluctuations in the sleep-waking cycle. J Neurosci. 1981;1:876–886. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-08-00876.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aston-Jones G, Chiang C, Alexinsky T. Discharge of noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurons in behaving rats and monkeys suggests a role in vigilance. Prog Brain Res. 1991;88:501–520. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63830-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballantyne D, Scheid P. Mammalian brainstem chemosensitive neurones: linking them to respiration in vitro. J Physiol (Lond) 2000;525:567–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00567.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayliss DA, Li YW, Talley EM. Effects of serotonin on caudal raphe neurons: activation of an inwardly rectifying potassium conductance. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:1349–1361. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.3.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernard DG, Li AH, Nattie EE. Evidence for central chemoreception in the midline raphe. J Appl Physiol. 1996;80:108–115. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.80.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buckler KJ, Williams BA, Honore E. An oxygen-, acid- and anaesthetic-sensitive TASK-like background potassium channel in rat arterial chemoreceptor cells. J Physiol (Lond) 2000;525:135–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davidson Ward SL, Keens TG. Ventilatory and arousal responses. In: Beckerman RC, Brouillette RT, Hunt CE, editors. Respiratory control disorders in infants And Children. Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore: 1992. pp. 112–124. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Decher N, Maier M, Dittrich W, Gassenhuber J, Bruggemann A, Busch AE, Steinmeyer K. Characterization of TASK-4, a novel member of the pH-sensitive, two-pore domain potassium channel family. FEBS Lett. 2001;492:84–89. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02222-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duprat F, Lesage F, Fink M, Reyes R, Heurteaux C, Lazdunski M. TASK, a human background K+ channel to sense external pH variations near physiological pH. EMBO J. 1997;16:5464–5471. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eger EI. What is general anesthetic action? Anesth Analg. 1993;77:408–409. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199308000-00050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Girard C, Duprat F, Terrenoire C, Tinel N, Fosset M, Romey G, Lazdunski M, Lesage F. Genomic and functional characteristics of novel human pancreatic 2P domain K+ channels. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282:249–256. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein SAN, Bockenhauer D, O'Kelly I, Zilberberg N. Potassium leak channels and the KCNK family of two-P-domain subunits. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:175–184. doi: 10.1038/35058574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gray AT, Zhao BB, Kindler CH, Winegar BD, Mazurek MJ, Xu J, Chavez RA, Forsayeth JR, Yost CS. Volatile anesthetics activate the human tandem pore domain baseline K+ channel KCNK5. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:1722–1730. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200006000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horner RL. Motor control of the pharyngeal musculature and implications for the pathogenesis of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 1996;19:827–853. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.10.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunt CE. Sudden infant death syndrome. In: Beckerman RC, Brouillette RT, Hunt CE, editors. Respiratory control disorders in infants and children. Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore: 1992. pp. 190–211. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobs BL, Azmitia EC. Structure and function of the brain serotonin system. Physiol Rev. 1992;72:165–229. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim D, Gnatenco C. TASK-5, a new member of the tandem-pore K+ channel family. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;284:923–930. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim D, Fujita A, Horio Y, Kurachi Y. Cloning and functional expression of a novel cardiac two-pore background K+ channel (cTBAK-1). Circ Res. 1998;82:513–518. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim Y, Bang H, Kim D. TBAK-1 and TASK-1, two-pore K+ channel subunits: kinetic properties and expression in rat heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1999;277:H1669–H1678. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.5.H1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim Y, Bang H, Kim D. TASK-3, a new member of the tandem pore K+ channel family. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9340–9347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leonoudakis D, Gray AT, Winegar BD, Kindler CH, Harada M, Taylor DN, Chavez RA, Forsayeth JR, Yost CS. An open rectifier potassium channel with two pore domains in tandem cloned from rat cerebellum. J Neurosci. 1998;18:868–877. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-03-00868.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lesage F, Lazdunski M. Molecular and functional properties of two-pore-domain potassium channels. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000;279:F793–F801. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.279.5.F793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopes CMB, Gallagher PG, Buck ME, Butler MH, Goldstein SA. Proton block and voltage gating are potassium-dependent in the cardiac leak channel Kcnk3. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:16969–16978. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001948200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopes CMB, Zilberberg N, Goldstein SA. Block of Kcnk3 by protons—evidence that 2-P-domain potassium channel subunits function as homodimers. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:24449–24452. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100184200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meadows HJ, Randall AD. Functional characterisation of human TASK-3, an acid-sensitive two-pore domain potassium channel. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40:551–559. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nattie E. CO2, brainstem chemoreceptors and breathing. Prog Neurobiol. 1999;59:299–331. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel AJ, Honore E. Properties and modulation of mammalian 2P domain K+ channels. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:339–346. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01810-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patel AJ, Honore E, Lesage F, Fink M, Romey G, Lazdunski M. Inhalational anesthetics activate two-pore-domain background K+ channels. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:422–426. doi: 10.1038/8084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patel AJ, Lazdunski M, Honore E. Lipid and mechano-gated 2P domain K+ channels. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:422–428. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pavlin EG, Hornbein TF. Anesthesia and the control of ventilation. In: Fishman AP, Cherniack NS, Widdicombe JG, editors. Handbook of physiology: the respiratory system, Vol 2. American Physiological Society; Bethesda, MD: 1986. pp. 793–813. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic; San Diego: 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Penington NJ, Kelly JS, Fox AP. Whole-cell recordings of inwardly rectifying K+ currents activated by 5-HT1A receptors on dorsal raphe neurones of the adult rat. J Physiol (Lond) 1993;469:387–405. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phillipson EA, Bowes G. Handbook of physiology. the respiratory system. American Physiological Society; Bethesda, MD: 1986. Control of breathing during sleep. pp. 649–689. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rajan S, Wischmeyer E, Xin LG, Preisig-Muller R, Daut J, Karschin A, Derst C. TASK-3, a novel tandem pore domain acid-sensitive K+ channel: an extracellular histidine as pH sensor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:16650–16657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rekling JC, Funk GD, Bayliss DA, Dong XW, Feldman JL. Synaptic control of motoneuronal excitability. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:767–852. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.2.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reyes R, Duprat F, Lesage F, Fink M, Salinas M, Farman N, Lazdunski M. Cloning and expression of a novel pH-sensitive two pore domain K+ channel from human kidney. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30863–30869. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.47.30863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richerson GB. Response to CO2 of neurons in the rostral ventral medulla in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1995;73:933–944. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.3.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Richerson GB. Sudden infant death syndrome: the role of central chemosensitivity. The Neuroscientist. 1997;3:3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richerson GB. Cellular mechanisms of sensitivity to pH in the mammalian respiratory system. In: Kaila K, Ransom BR, editors. pH and brain function. Wiley-Liss; New York: 1998. pp. 509–533. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sirois JE, Lei Q, Talley EM, Lynch C, III, Bayliss DA. The TASK-1 two-pore domain K+ channel is a molecular substrate for neuronal effects of inhalation anesthetics. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6347–6354. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-17-06347.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Talley EM, Lei Q, Sirois JE, Bayliss DA. TASK-1, a two-pore domain K+ channel, is modulated by multiple neurotransmitters in motoneurons. Neuron. 2000;25:399–410. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80903-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Talley EM, Solórzano G, Lei Q, Kim D, Bayliss DA. CNS distribution of members of the two-pore-domain (KCNK) potassium channel family. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7491–7505. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-07491.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tiwari JK, Zaykin AV, Cruadhlaoich MI, Wang W, Richerson GB. A novel pH sensitive cation current is present in putative central chemoreceptors of the medullary raphe. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 2000;26:423. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Veasey SC, Fornal CA, Metzler CW, Jacobs BL. Single-unit responses of serotonergic dorsal raphe neurons to specific motor challenges in freely moving cats. Neuroscience. 1997;79:161–169. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00673-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vega-Saenz DM, Lau DH, Zhadina M, Pountney D, Coetzee WA, Rudy B. Kt3.2, kt3.3, two novel human two-pore K+ channels closely related to TASK-1. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:130–142. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang W, Richerson GB. Chemosensitivity of non-respiratory rat CNS neurons in tissue culture. Brain Res. 2000;860:119–129. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang WG, Tiwari JK, Bradley SR, Zaykin AV, Richerson GB. Acidosis-stimulated neurons of the medullary raphe are serotonergic. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:2224–2235. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.5.2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watson RE, Jr, Wiegand SJ, Clough RW, Hoffman GE. Use of cryoprotectant to maintain long-term peptide immunoreactivity and tissue morphology. Peptides. 1986;7:155–159. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(86)90076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]