Abstract

Body temperature (Tb) was recorded at 10 min intervals over 2.5 years in female golden-mantled ground squirrels that sustained complete ablation of the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCNx). Animals housed at an ambient temperature (Ta) of 6.5°C were housed in a 12 hr light/dark cycle for 19 months followed by 11 months in constant light. The circadian rhythm ofTb was permanently eliminated in euthermic and torpid SCNx squirrels, but not in those with partial destruction of the SCN or in neurologically intact control animals. Among control animals, some low-amplitude Tb rhythms during torpor were driven by small (<0.1°C) diurnal changes inTa. During torpor bouts in whichTb rhythms were unaffected byTa, Tbrhythm period ranged from 23.7 to 28.5 hr. Both SCNx and control squirrels were more likely to enter torpor at night and to arouse during the day in the presence of the light/dark cycle, whereas entry into and arousal from torpor occurred at random clock times in both SCNx and control animals housed in constant light. Absence of circadian rhythms 2.5 years after SCN ablation indicates that extra-SCN pacemakers are unable to mediate circadian organization in euthermic or torpid ground squirrels. The presence of diurnal rhythms of entry into and arousal from torpor in SCNx animals held under a light/dark cycle, and their absence in constant light, suggest that light can reach the retina of hibernating ground squirrels maintained in the laboratory and affect hibernation via an SCN-independent mechanism.

Keywords: suprachiasmatic nucleus, hibernation, circadian, torpor, body temperature, golden-mantled ground squirrel

Mammals from several orders engage in seasonal heterothermy. Survival during times of food shortages and low winter temperatures is facilitated by marked reductions in metabolic rate and body temperature (Tb). In heterothermic mammals, individual bouts of torpor range in duration from several hours to several days. A hibernation season typically consists of multiday torpor bouts that alternate with brief (<20 hr) intervals of euthermia (Lyman et al., 1982). By contrast, other rodent species engage in daily torpor bouts that are relatively brief (i.e., 2–10 hr) and restricted to the inactive phase of the rest–activity cycle (Lindberg and Hayden, 1974; Ruf et al., 1989; Wollnik and Schmidt, 1995; Körtner et al., 1998). In Siberian hamsters, a circadian pacemaker within the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) synchronizes daily torpor bouts to begin at dawn (Ruby and Zucker, 1992).

The role of the circadian system in timing multiday torpor bouts during hibernation is less clear. Rodent hibernators typically remain in their underground burrows continuously throughout the winter where they are not exposed to daily changes in illumination. Nevertheless, circadian control of entry into and arousal from individual torpor bouts remains a distinct possibility. Tb rhythms persist with a mean circadian period of 22 hr during deep torpor (Tb ∼ 12°C) in golden-mantled ground squirrels (Spermophilus lateralis) (Grahn et al., 1994). Arousals from torpor occur at the same circadian phase regardless of the duration of the torpor bout (Grahn et al., 1994) and are much more frequent in the absence of circadian input (Ruby et al., 1996). Periodic arousals from hibernation are presumed to serve a necessary, even if presently unspecified, physiological function (Lyman et al., 1982). Because the arousal process and subsequent intervals of euthermia are energetically costly and counter some of the energy-saving benefits of hibernation, the circadian system may coordinate timing of arousal from hibernation with other physiological functions and thereby maintain torpor bouts at an optimum duration.

The SCN is a likely candidate for circadian control of torpor bout duration during hibernation. Not only is the SCN the primary circadian pacemaker in mammals (Rusak and Zucker, 1979), but it functions at low tissue temperatures in hibernators (Kilduff et al., 1989; Ruby and Heller, 1996). In golden-mantled ground squirrels, brain metabolic activity decreases markedly as animals enter torpor; this effect is, however, attenuated in the SCN where metabolic activity becomes high relative to most other brain structures (Kilduff et al., 1989). The amplitude of circadian neuronal rhythms within the SCN of hibernating ground squirrels also is buffered from changes in tissue temperature to a much greater extent than it is in nonhibernating species such as rats. A decrease in SCN temperature from 37 to 25°C in vitro, which has little effect on neuronal rhythm amplitude in the squirrel SCN, completely suppressed rhythm expression in the rat SCN (Ruby and Heller, 1996).

Two previous reports documented that ablation of the SCN is associated with marked changes in the duration of individual torpor bouts and also affects the duration of the hibernation season (Ruby et al., 1996,1998). Because circadian Tb rhythms appear to persist during hibernation, and arousals are timed by the circadian system (Canguilhem et al., 1994; Grahn et al., 1994; Wollnik and Schmidt, 1995), we investigated the role of the SCN in circadian timing of Tb rhythms during euthermia and deep torpor. A brief in-progress report of some of these findings was previously published (Zucker et al., 1993).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

The female golden-mantled ground squirrels used in this study were born in the Berkeley laboratory to pregnant females that were trapped near Truckee, CA at an elevation of ≈1800 m. Squirrels were housed individually in a 14:10 light/dark (LD) cycle [lights on from 7:00 A.M. to 9:00 P.M., Pacific standard time (PST)] atTa = 23 ± 2°C. Food (Purina Chow #5012) and water were available ad libitum, and animals were weighed weekly (± 0.1 gm) throughout the study. Squirrels were provided cotton batting for nesting material.

Brain lesions

When animals were 2–3 years of age and at or near their annual body mass nadir they were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (12.5 mg/100 gm body mass + 0.1 mg/each additional 10 gm body mass, administered intraperitoneally) supplemented with methoxyflurane vapors (Metofane) as necessary to maintain deep anesthesia. Squirrels were positioned in a stereotaxic instrument (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA) with the incisor bar 1.0 mm above the interaural line, and a single midline incision was made. Bilateral radiofrequency lesions were made at 8.2 and 8.4 mm anterior to ear bar zero, ±0.3 mm lateral to the midsagittal sinus, and 9.7 mm ventral to dura by passing current (≈10 mA) for 30 sec through an insect pin that was insulated except for 1.0 mm at the tip. The wound was closed with sterile sutures and treated with 0.2% nitrofurazone (Furacin) ointment. An analgesic solution (60 mg of acetaminophen and 6 mg of codeine phosphate/100 ml water) was added to the drinking water for the first 4 d after surgery.

Body temperature and locomotor activity

All squirrels had radiofrequency transmitters (model VM-FH disc; Minimitter Co.) implanted in their abdominal cavities for telemetric recording of Tb 1–2 years after brain surgery. Calibration and implantation of transmitters were as described previously (Dark et al., 1992). All procedures were approved by the University of California Berkeley Animal Care and Use Committee. Two weeks after this second surgery, squirrels were transported to the Stanford laboratory and housed at Ta = 6.5°C in a 12 hr LD cycle (lights on at 8:00 A.M.) for the first 19 months and in constant light (LL; 350 lux) for the next 11 months. Animals were in the body mass loss phase of their circannual cycle when initially exposed to low Ta.Tb data were recorded by computer (Dataquest Co.) at 10 min intervals for the remainder of the study. Food and water were available ad libitum.

Autopsy procedures

At the end of the study squirrels were administered a lethal dose of pentobarbital sodium (intraperitoneally) and perfused with 0.9% saline followed by buffered formalin. Brains were immediately removed, and frozen coronal sections (50 μm) were cut through an area beginning rostral to the optic chiasm and ending caudal to the retrochiasmatic area. Tissue was stained with a Nissl-type stain (cresyl violet), and damage was assessed independently by two investigators without knowledge of the corresponding behavioral or body mass data. Densely stained tissue that had apparently viable neurons along the borders of the damaged area, but within boundaries of the SCN, was considered evidence of possible residual SCN tissue. Complete SCN ablation was strictly defined as the unambiguous absence of any SCN tissue. The extent of damage to non-SCN nuclei was estimated by comparing tissue sections of control animals and those with brain lesions. When interinvestigator assessment of tissue damage to non-SCN nuclei differed by >15%, sections were reexamined until a consensus was reached; re-examination was necessary in <10% of all sections.

Data analysis

Circadian rhythms during euthermia. SCNx squirrels were categorized as either “continuous hibernators” (SCNx-CH) that expressed torpor bouts throughout the year or “noncontinuous hibernators” (SCNx-NCH) that had typical seasonal cycles of hibernation; these designations are retained from earlier studies of these animals (Ruby et al., 1996, 1998). The circadian period (i.e., tau) of Tb rhythms during euthermia was determined by an SD-based periodogram analysis (Dorrscheidt and Beck, 1975); 10 d blocks of data at the beginning, middle, and end of the nonhibernation seasons during both the LD and LL phases of the study were analyzed for control and SCNx-NCH animals. Tau values of SCNx-CH animals were calculated for 5–7 d intervals during calendar dates that corresponded to the same three phases of the nonhibernation season of the other groups. This was necessary because SCNx-CH squirrels rarely remained euthermic for as long as 10 d (Ruby et al., 1996). Peaks in the periodogram were deemed statistically significant if they exceeded the 99% confidence interval limit.Tb rhythms were considered entrained or free running based on periodogram analysis. Because a 10 min sampling interval was used for data acquisition, periodogram analysis occasionally estimated rhythm period to be 23.83 or 24.17 hr (i.e., 24.00 hr ± 1 sampling interval) for entrained animals. Rhythms with periods of 23.83, 24.00, or 24.17 hr that also maintained a stable phase relation to the LD cycle were considered entrained and were considered free running if tau was <23.83 or >24.17 hr. Qvalues (i.e., power) from the periodogram analysis range from 0.0 to 1.0 and quantify rhythm coherence. Oscillations with higherQ values have more stable periods and amplitudes than those with lower Q values.

Circadian rhythms during deep torpor. Circadian organization of Tb rhythms during deep torpor (i.e., Tb < 8.5°C) was evaluated for each torpor bout of each animal. Bouts were excluded from the periodogram analysis if rhythm amplitude or daily meanTb was unstable, if bouts were <3-d-long, or where electrical interference rendered data uninterpretable. A total of 1813 bouts that were expressed by control, SCNx, and PSCNx ground squirrels were analyzed, including 80 bouts from control animals housed in LL. Tau values ofTb rhythms were calculated for individual bouts of deep torpor (meanTb < 8.0°C) by truncating the entry and arousal phases at the same temperature as was reached at the highest point of the Tb oscillation during the bout. To determine whether there were any changes inTa over the course of a bout, periodogram analysis was also performed onTa recorded over the same interval that encompassed the torpor bout. Rhythm amplitude was calculated as the difference between the highest and lowest temperatures recorded during a bout.

Timing of entry into and arousal from torpor, calculated for each animal while it was maintained in an LD cycle and in LL, are expressed relative to zeitgeber time (ZT), where ZT0 is defined as the time of light onset. All torpor bouts were included in this analysis. The times of entry into and arousal from torpor were defined as the first and last time point, respectively, when Tbwas <34°C during a torpor bout. The percentage of bout entries and arousals that occurred in 6 hr intervals between ZT 0–6, 6–12, 12–18, and 18–24 were determined for each animal and used to calculate mean percentages of entry and arousal times for each group of squirrels. The duration of the entry and arousal phases of torpor were calculated for each animal as the means of three randomly selected torpor bouts taken from the middle of the last complete hibernation season. Because circannual rhythms of hibernation were eliminated in SCNx-CH squirrels (Ruby et al., 1996), duration of entries and arousals from torpor were taken from bouts expressed at the same calendar times as for other animals. The duration of entrance into and arousal from torpor was calculated as the interval between the first transition ofTb from <34°C to <14°C, in opposite directions, respectively.

Differences among groups were evaluated using ANOVA, with repeated measures where appropriate, or t tests (SigmaStat); group values are means (±SE). Dunnett's post hoc correction was applied for unplanned pairwise comparisons of experimental versus control animals. Differences were deemed statistically significant ifp < 0.05.

RESULTS

Histological analysis of brain lesions

A detailed histological analysis of brain lesions for animals in this study has been reported (Ruby et al., 1998). Based on that analysis, animals were grouped as controls (n = 6), SCNx-CH (n = 4), SCNx-NCH (n = 4), or PSCNx (n = 4), where SCNx indicates complete bilateral SCN ablation and PSCNx indicates partial (40–90%) SCN ablation.

Circadian Tb rhythms in euthermic squirrels between hibernation seasons

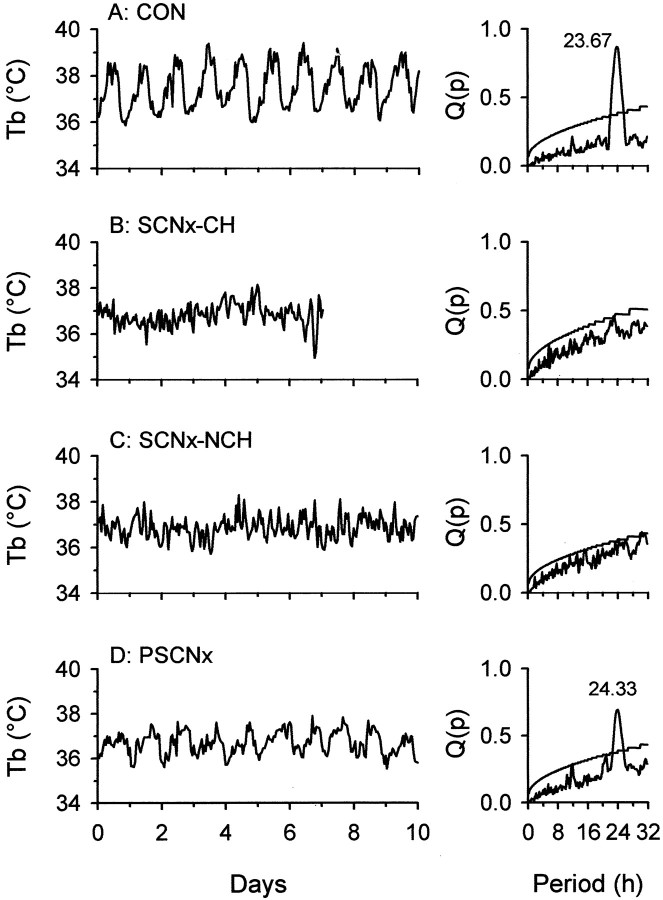

Circadian Tb rhythms were observed in all control animals in the months between hibernation seasons. During housing in the LD cycle, rhythms were always entrained (mean period = 24.05 ± 0.04 hr). At the beginning, middle, and end of each euthermic season in LL, tau ranged from 23.67 to 24.33 hr and was always >24.17 or <23.83 hr in individual animals. Tau never changed by >10 min (i.e., one sampling interval) in individual squirrels within each euthermic season or across successive ones (Fig.1); mean (±SE) Q value = 0.82 ± 0.01.

Fig. 1.

Representative Tb plots from control (A), SCNx-CH (B), SCNx-NCH (C), and PSCNx (D) squirrels. Periodogram results [Q(p)] for each animal are adjacent to their respective plots; tau is given for significant peaks (p < 0.001). Data inA, C, and D were obtained during the middle phase of each squirrel's annual nonhibernation season during housing in constant light. Because annual patterns of hibernation were eliminated in SCNx-CH animals,Tb data (B) were obtained for these squirrels during the single longest euthermic period during housing in constant light.

In contrast to control animals, no significant circadian rhythms inTb were detected in SCNx-NCH animals at any time in either the LD cycle or LL (p > 0.05) (Fig. 1). Euthermic intervals between individual torpor bouts never exceeded 10 d in SCNx-CH squirrels, consequently, periodogram analyses were conducted on data spans of 5–7 d for each of these animals. No significant circadian periodicity was detected in any of these squirrels (p > 0.05) (Fig. 1).Tb rhythms of PSCNx squirrels entrained to the LD cycle and then free-ran during LL with tau values ranging from 23.83 to 24.50 hr (Q value = 0.74) in LL (Fig. 1).

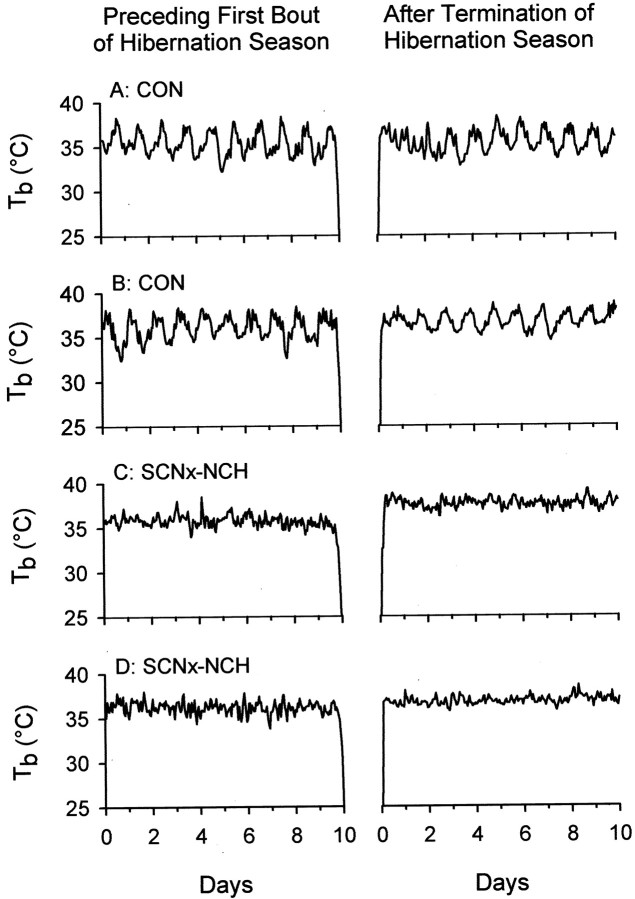

Circadian Tb rhythms before onset and after termination of the hibernation season

Circadian organization for squirrels housed in LD and LL conditions was evaluated during the 5 d periods before the first torpor bout, and after the final torpor bout, of each hibernation season. Normal integrity of Tb rhythms was maintained before the onset of the first hibernation bout in control and PSCNx squirrels, whereasTb rhythms were absent in all SCNx-NCH animals (Fig. 2). In two of six control animals, some loss in rhythm coherence was observed during the first 2–3 d after the terminal arousal from hibernation seasons in the LD cycle and in LL (Fig. 2). Arrhythmia was not observed in the remaining four control animals or in any of the PSCNx squirrels, but all SCNx-NCH and SCNx-CH animals were arrhythmic before and after each hibernation season.

Fig. 2.

Representative Tb plots from different control (A, B) and SCNx-NCH (C, D) squirrels before (left panels) and after (right panels) a hibernation season in LL. CircadianTb rhythms were robust in all control animals in the days immediately preceding the onset of hibernation. Post-hibernation arrhythmicity was observed in two of six control animals and lasted for no more than 3 d (A, right panel). Tb rhythms were undetectable in SCNx-NCH squirrels before and after hibernation.

Circadian Tb rhythms during deep torpor

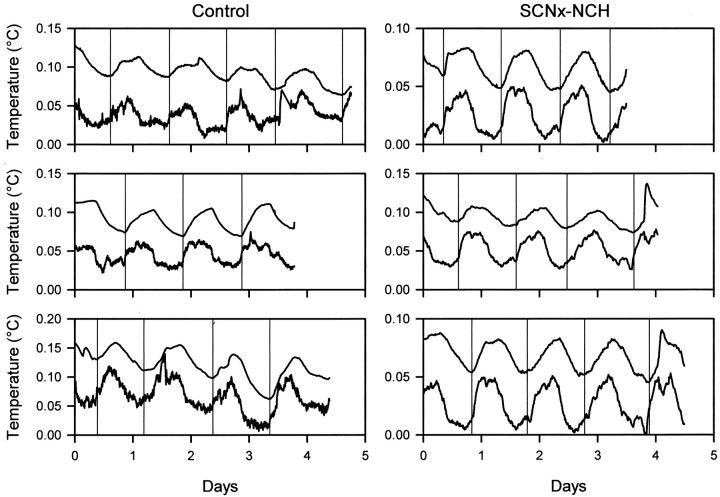

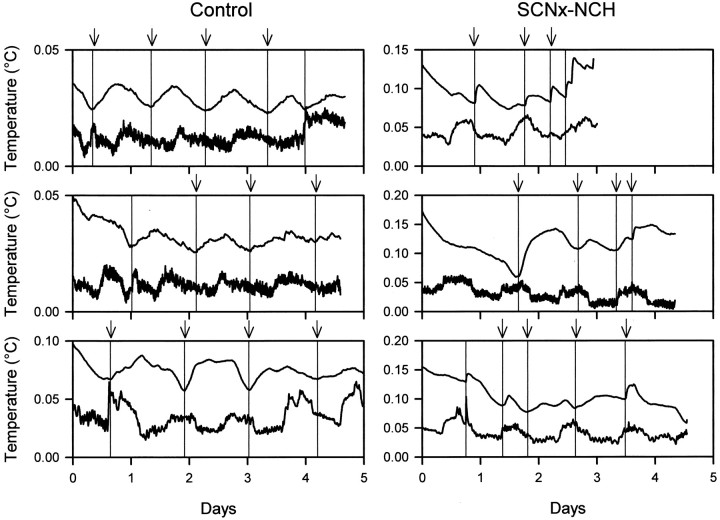

Periodogram analysis confirmed the absence of circadianTb rhythms in 45 of 80 torpor bouts expressed by control animals in LL. No further analyses were performed on those bouts. In the remaining 35 bouts, changes inTb frequently paralleled small changes in Ta. In most cases, the timing and amplitude of these rhythms were similar (Fig.3).

Fig. 3.

Representative plots of relativeTb and Ta values from control (left panels) and SCNx-NCH (right panels) squirrels during deep torpor bouts in which changes inTb closely parallel changes inTa. Tb is thetop, and Ta is thebottom line in each plot. Vertical reference lines indicate Tb nadirs. Data are plotted as relative values because the large difference betweenTb and Ta(2–3°C) and the very small rhythm amplitudes (<0.05°C in many cases) made rhythm synchrony difficult to visualize in the raw data. To facilitate visualization of phase relations betweenTb and Tarhythms, the interval between Tb andTa was reduced by subtracting a different constant from raw Tb andTa values for each torpor bout. This normalization procedure preserves the rhythm phases and amplitudes observed in the raw data. Note that rises inTa after the nadir always precede rises inTb.

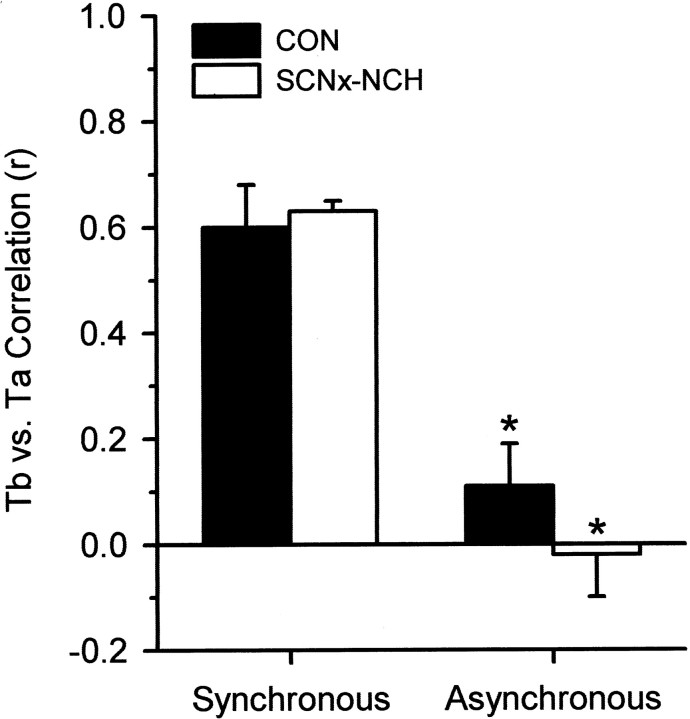

Phase relations between simultaneously recordedTb andTa records were evaluated by visual inspection; they were judged as synchronous if they unambiguously oscillated in unison and as asynchronous if concurrentTb andTa changes were in opposite directions. Records in which Tb andTa rhythms were synchronized for only part of a torpor bout were excluded from the analysis that was performed by an independent investigator not otherwise involved in this study. Pearson's correlation coefficient betweenTb andTa was calculated for each torpor bout to quantify the magnitude of synchronization betweenTb andTa. Correlation coefficients from every bout were statistically significant (p < 0.001) and used to generate mean coefficients for synchronous or asynchronous torpor bouts.

There was a robust correlation for both control and SCNx-NCH animals (r > 0.60) between Tband Ta for bouts in which these rhythms were categorized as synchronous (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4). Mean correlation coefficients for both groups of animals in which the rhythms were judged as asynchronous were weak (r < 0.11) and significantly lower than values obtained for synchronous bouts (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4). In the synchronous bouts, the nadir of the Ta oscillation always preceded the nadir of the Tboscillation in both control and SCNx-NCH squirrels (Fig. 3). The time lag between the nadirs of these two oscillations was over four times greater for SCNx-NCH animals than for control squirrels (p < 0.001) (Table1). In the asynchronous bouts, the nadirs of Tb andTa rhythms were ∼180° out of phase (Fig. 5), and the interval between the nadirs of the Ta oscillation and the subsequent Tb oscillation did not differ between control and SCNx-NCH groups (p > 0.05) (Table 1).

Fig. 4.

Mean (±SE) r values for correlations between Tb andTa for torpor bouts that were judged as synchronous or asynchronous based on visual inspection of the data. *p < 0.001 compared with synchronous bouts.

Table 1.

Period and phase of Tb andTa rhythms during deep torpor in LL

| Group1-a | n | Period (h)1-b | Nadir Interval (hr)1-c | Bout duration (d) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tb | Ta | Tb-Ta | ||||

| Synchronous | ||||||

| CON | 21 | 23.92 ± 0.11 | 23.88 ± 0.15 | 0.04 ± 0.10 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 4.9 ± 1.7 |

| SCNx-NCH | 10 | 23.36 ± 0.28 | 23.11 ± 0.22 | 0.25 ± 0.19* | 4.0 ± 0.6* | 3.9 ± 0.7 |

| Asynchronous | ||||||

| CON | 6 | 24.43 ± 1.09 | 22.84 ± 1.07 | 1.60 ± 0.94* | 10.3 ± 1.1* | 4.5 ± 0.3 |

| SCNx-NCH | 6 | NS | 23.81 ± 0.36 | — | — | 3.5 ± 0.2 |

Torpor bouts were categorized as in phase if cyclic increases in Tb occurred shortly after cyclic increases in Ta and as out of phase if Tb increases occurred asTa decreased or remained stable.

Rhythm periods were determined by periodogram analysis. Absolute differences betweenTb and Ta were calculated for each torpor bout.

Nadir interval represents the time lag between the daily nadirs of Ta andTb rhythms.

p < 0.001 compared with CON for synchronous torpor bouts. NS, No significant circadian periodicity.

Fig. 5.

Representative Tb andTa plots from control (left panels) and SCNx-NCH (right panels) squirrels during deep torpor bouts in which Tb rhythms appear to be independent of changes in Ta. Conventions as in Figure 3. Note that rises inTb occur when Tais declining or stable (indicated by arrows). Absolute values were normalized as in Figure 3.

Significant periodicity (p < 0.001) in the circadian range was evident in the rhythms of control animals in whichTb andTa rhythms were synchronous or asynchronous (Table 1). Rhythm periods ranged from 23.7 to 28.5 hr forTb and 22.4 to 26.9 hr forTa and did not differ between synchronous and asynchronous bouts. The difference betweenTb andTa periods within individual torpor bouts was negligible when these two rhythms were synchronized, but exceeded 90 min when the two rhythms were asynchronous. In the latter case, the mean periods of the Tb andTa rhythms were >24 hr and <23 hr, respectively (Table 1). Significant circadianTb rhythms were detected in SCNx-NCH animals during torpor bouts in whichTb andTa were synchronized (p < 0.001) but not when these two measures were asynchronous (p > 0.05) (Table 1).

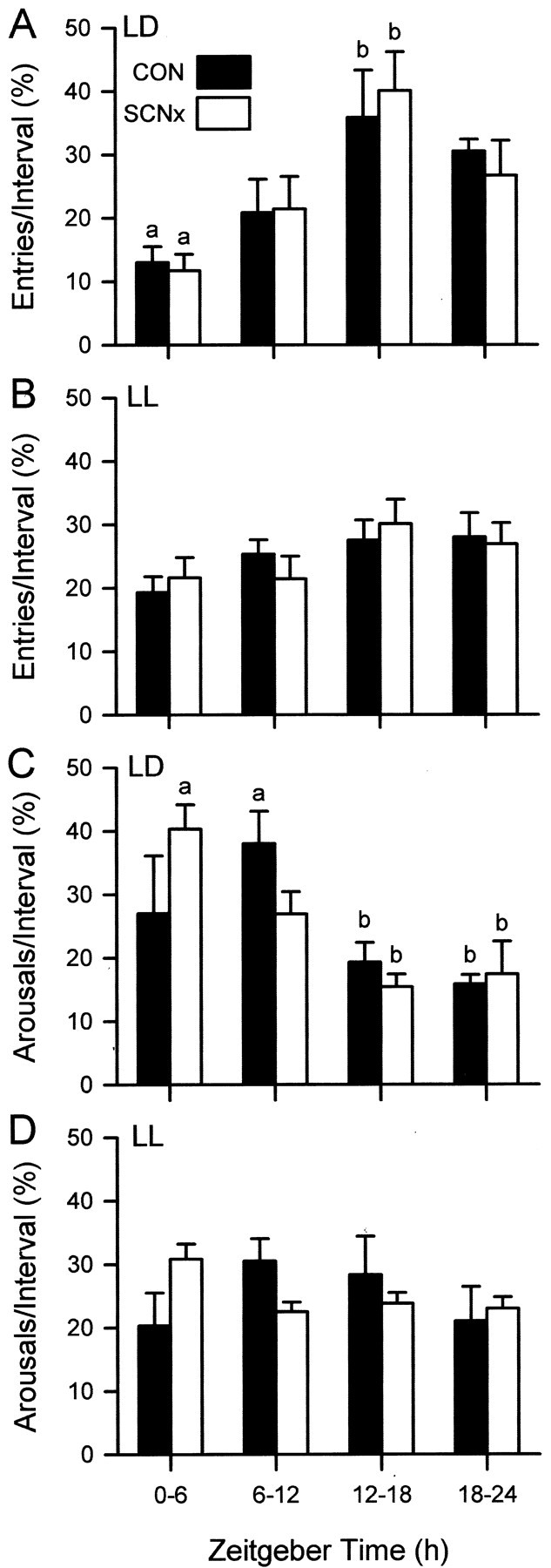

Timing of torpor entry and arousal

Entries into and arousals from torpor were categorized into four 6 hr time bins. Because only two PSCNx animals survived until the end of the study, data for this group were excluded from the statistical analysis. The time bin during which squirrels entered and aroused from torpor did not differ among the SCNx-NCH, SCNx-CH, and control squirrels (p > 0.05). Data from SCNx-NCH and SCNx-CH were combined to form a single SCNx group for subsequent analyses. Entry into torpor occurred more frequently during the first 6 hr of the dark phase (ZT 12–18) for squirrels maintained in the LD cycle (p < 0.05) (Fig.6) but was distributed equally in each 6 hr time bin for animals housed in LL (p > 0.05) (Fig. 6). Arousals from torpor were more likely during the daytime in both control and SCNx animals in LD conditions (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6) but occurred with equal frequency in each time bin for squirrels housed in LL (p > 0.05) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Time of day of entries in an LD cycle (A) and in LL (B) and of arousals from torpor in an LD cycle (C) and in LL (D) for control and SCNx squirrels. Bars with different letters differ significantly from each other (p < 0.05). There were no differences among control and SCNx animals in either lighting condition. Statistical comparisons were not made between LD and LL values. Zeitgeber time 0 = light onset (8:00 A.M. PST) in the 12 hr LD cycle.

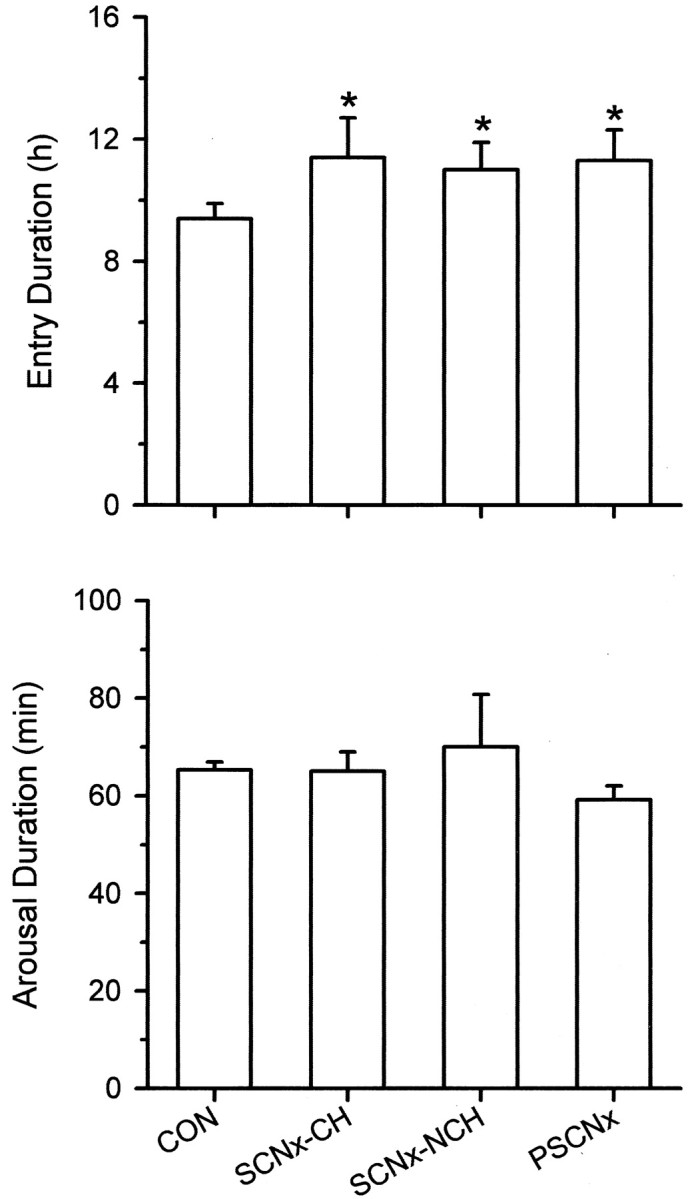

Duration of torpor entry and arousal

Entry into deep torpor (Tb < 8.0°C) was completed in 9.4 ± 0.5 hr by control animals but required an extra 2 hr for SCNx-CH, SCNx-NCH, and PSCNx squirrels (p < 0.05) (Fig.7); there were no significant differences among the latter three groups (p > 0.05). In contrast, the four groups did not differ in the time needed to arouse from torpor (p > 0.05) (Fig. 7), which was 64.9 ± 11.3 min.

Fig. 7.

Torpor entry and arousal durations for all animals. Entries and arousals are defined as the time required forTb to change between 14 and 34°C. *p < 0.05 compared with control value.

DISCUSSION

Circadian Tb rhythms during the nonhibernation season were eliminated in animals that sustained complete ablation of the SCN but persisted in ground squirrels with as little as 10% of the SCN intact. Tbrhythms were robust in control animals during 11 months of exposure to constant light, as previously documented for locomotor activity rhythms in this species (Zucker et al., 1983) and other diurnal mammals (Aschoff, 1981; Fuller et al., 1981; DeCoursey et al., 1997). The absence of circadian Tb rhythms 2.5 years after SCN ablation indicates that extra-SCN structures are insufficient to restore circadian rhythmicity lost after SCN ablation (Ruby et al., 1998). Similar persistent arrhythmicity lasting 7 months was documented in rats that sustained SCN damage a few days after birth (Mosko and Moore, 1979). The histological data, combined with behavioral observations, suggest that the SCNx ground squirrels lacked functional SCN tissue; circadian Tbrhythms persist in animals with <10% of the normal complement of SCN cells (Ruby and Zucker, 1992; Satinoff and Prosser, 1998).

The persistence of Tb rhythms in all control and some SCNx squirrels during some bouts of deep torpor may reflect passive heating and cooling in response to changes inTa or, alternatively, the expression of a weak endogenous Tb rhythm synchronized to Ta oscillations. The sensitivity of Tb to small fluctuations in Ta emphasizes the importance of continuous monitoring ofTa during torpor as a means of distinguishing endogenous from exogenously drivenTb rhythms. The period of theTa rhythm must be assessed separately for each bout, because the Ta rhythm often was not stable but varied by >4 hr. Small-amplitudeTa rhythms were sometimes the result of cyclic activity of the machinery used to cool the animal room and likely are present in the majority of laboratory investigations, although not usually reported. Ground squirrels housed in an environmental chamber in which cyclicTa fluctuations are absent at 9°C, nevertheless continue to express circadianTb rhythms during torpor (J. E. Larkin, P. Franken, and H. C. Heller, unpublished observations). The dependence of Tb on diurnal rhythms in Ta has also been reported for European hamsters and marmots housed in a laboratory (Wollnik and Schmidt, 1995; Florant et al., 2000). Torpid marmots did not express circadian Tb rhythms in the field where burrow temperatures remain constant over the course of several days but did manifest Tb rhythms during torpor in the laboratory whereTa oscillated with a period of ∼24 hr (Florant et al., 2000). European hamsters and marmots are substantially larger than ground squirrels and have a greater thermal mass so the time lag for increases inTb after a rise inTa is greater than it is for ground squirrels (Wollnik and Schmidt, 1995).

The positive masking effects of Ta onTb are temperature-dependent and may explain why circadian rhythms were not observed in many of the torpor bouts in control animals. In a different study of this species, circadian Tb rhythms during deep torpor were uniformly present in all ground squirrels housed at variousTa values between 10 and 27°C, but were only detectable in a minority of animals housed at 5°C (Grahn et al., 1992; Heller et al., 1993). In addition,Tb rhythm amplitude decreased linearly as Ta declined (Heller et al., 1993).Tb may be more sensitive to changes inTa at lowTa values where the gradient betweenTb andTa is relatively small, and the amplitudes of the two rhythms are similar. By contrast, variations inTa do not affectTb of euthermic squirrels, presumably because theTb–Tagradient and amplitude of the Tbrhythm are both much greater. Thus, control animals would likely have consistently expressed Tb rhythms during torpor had they been maintained above 10°C rather than at 6.5°C. The decrease in endogenous rhythm amplitude at lowTa may also explain the absence ofTb rhythms during deep torpor in marmots (Florant et al., 2000) and Arctic ground squirrels (Barnes and Ritter, 1993) observed in the field whereTa values are very low (i.e., −2 to 7°C).

Several features ofTb–Tarelations during asynchronous torpor bouts suggest thatTb rhythms were endogenously generated and not driven by Ta.Tb rhythms free ran with periods >24 hr in LL, whereas Ta rhythms simultaneously oscillated with periods that were <24 hr. The time lag between Tb andTa nadirs was also over 10 times greater for these bouts than for synchronous ones. In many cases, a rise in Tb was coincident with a decline in Ta. These phenomena are characteristic of two independently oscillating rhythms. In addition, SCNx animals never expressed Tbrhythms in the absence of Ta rhythms. In golden-mantled ground squirrels, circadianTb rhythms evidently persist during deep torpor at Ta = 10°C. The periods of these rhythms, although more variable than euthermicTb rhythms, are temperature-compensated (Grahn et al., 1994). Rhythm period and amplitude within the SCN of hibernators studied in vitro are also temperature-compensated and may persist atTb values <10°C even whenTb rhythms are not consistently expressed (Ruby and Heller, 1996).

European and Arctic ground squirrels undergo seasonal circadian arrhythmia under seminatural and field conditions, respectively (Wollnik and Schmidt, 1995; B. M. Barnes, personal communication). None of the ground squirrels in the present study developed circadian arrhythmicity in advance of the hibernation season and only two squirrels were arrhythmic for up to 2–3 d after hibernation ended. Absence of circadian organization before and after the hibernation season was previously reported for only a minority of golden-mantled ground squirrels (Grahn et al., 1994). This species does, however, exhibit other seasonal changes in circadian organization. The period of the locomotor activity rhythm is >24 hr during the winter and <24 hr during the summer months, and the phase angle of activity onset is delayed during winter compared with summer (Zucker et al., 1983; Lee et al., 1986; Lee and Zucker, 1995; Freeman and Zucker, 2000). The functional significance of these seasonal circadian changes and of seasonal arrhythmia are unknown, but their existence suggests a flexibility in circadian organization (Zucker, 2001).

Timing of entry into and arousal from torpor in intact and SCNx animals was influenced by the LD cycle. Both groups of squirrels were more likely to enter torpor during the night and to arouse during the day. This is unlikely to be an artifact of extraneous noise and human disturbances during the daylight hours because the apparent rhythms were absent in animals housed in LL, although laboratory procedures were similar to those in place during the LD cycle. The similarities among control and SCNx squirrels suggests that the LD cycle may have exerted its effects through noncircadian (i.e., masking) mechanisms. Because hibernators enter torpor during slow-wave sleep (Heller et al., 1978), onset of torpor may be delayed until nighttime because light inhibits sleep in this diurnal species. Torpor onset at night has also been reported for other hibernators, although the time of entry can be highly variable both intraspecifically and interspecifically (Strumwasser, 1959; Strumwasser et al., 1967; Daan, 1973; Canguilhem et al., 1994; Wollnik and Schmidt, 1995; Körtner et al., 1998). It is more difficult to explain how the LD cycle affects the timing of arousal from torpor. Each squirrel in this study constructed a nest out of cotton batting, curled up with its head tucked in and eyes close to the bottom of the nest, and covered itself with additional cotton batting. It seems, nevertheless, that light reached the retina and thereby affected the timing of arousal. This would not be expected to occur under natural conditions in which hibernaculum structure and deep snow cover preclude exposure to daylight during hibernation (Bronson, 1979).

The effects of SCN ablation on individual components of hibernation may be unrelated to the attendant loss of circadian organization. Rate of entry into torpor, duration of torpor bouts, intervals between bouts, and duration of hibernation seasons (Ruby et al., 1996) did not differ between SCNx-NCH and PSCNx squirrels, although animals with partial SCN lesions had robust circadian rhythms, and SCNx squirrels were arrhythmic. Modest damage (10–25%) to the SCN that was sufficient to alter hibernation patterns left circadian function intact. The small number of squirrels with partial SCN damage, combined with high variability in the extent of their tissue damage, defy localization of hibernation functions within the SCN. Such an attempt is also complicated by sequelae of SCN damage that may be unrelated to SCN circadian function (cf., Rusak and Zucker, 1979). For example, the failure of Siberian hamsters to express torpor after complete SCN ablation may derive from postoperative hyperprolactinemia rather than to the loss of circadian organization (Bittman et al., 1991; Ruby et al., 1993). Similarly, involvement of the SCN in regulation of blood glucose, glucose tolerance, and fluid intake may be separate from its role as a circadian pacemaker (Nagai et al., 1994; la Fleur et al., 2001). These observations suggest that the SCN influences hibernation in a manner that is independent of its role as a circadian pacemaker. The SCN may have been co-opted to participate in the regulation of hibernation because of its ability to function at low temperatures (Kilduff et al., 1989; Ruby and Heller, 1996) or conversely, because the SCN was essential for timing hibernation, it had to remain functional at low temperatures.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HD-14595, HD-07471, NS30816, and AG-11084. We thank Tom Kang, Kimberly Pelz, Atul Saran, and Christiana Tuthill for their excellent technical assistance.

Correspondence should be addressed to Norman F. Ruby, Department of Biological Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305-5020. E-mail: ruby@stanford.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aschoff J. Freerunning and entrained circadian rhythms. In: Aschoff J, editor. Handbook of behavioral neurobiology, Vol 4. Plenum; New York: 1981. pp. 81–93. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes BM, Ritter D. Patterns of body temperature change in hibernating Arctic ground squirrels. In: Carey C, Florant GL, Wunder BA, Horwitz B, editors. Life in the cold. Westview; Boulder, CO: 1993. pp. 119–130. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bittman EL, Bartness TJ, Goldman BD, DeVries GJ. Suprachiasmatic and paraventricular control of photoperiodism in Siberian hamsters. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:R90–R101. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.260.1.R90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bronson MT. Altitudinal variations in the life history of the golden-mantled ground squirrel (Spermophilus lateralis). Ecology. 1979;60:272–279. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canguilhem B, Malan A, Masson-Pévet M, Nobelis P, Kirsch R, Pévet P, Le Minor J. Search for rhythmicity during hibernation in the European hamster. J Comp Physiol [B] 1994;163:690–698. doi: 10.1007/BF00369521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daan S. Periodicity of heterothermy in the garden dormouse, Eliomys quercinus (L.). Neth J Zool. 1973;23:237–265. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dark J, Ruby NF, Wade GN, Licht P, Zucker I. Accelerated reproductive development in juvenile male ground squirrels fed a high-fat diet. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:R644–R650. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.262.4.R644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeCoursey PJ, Krulas JR, Mele G, Holley DC. Circadian performance of suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN)-lesioned antelope ground squirrels in a desert enclosure. Physiol Behav. 1997;62:1099–1108. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(97)00263-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorrscheidt GJ, Beck L. Advanced methods for evaluating characteristic parameters (τ,α,ρ) of circadian rhythms. J Math Biol. 1975;2:107–121. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Florant GL, Hill V, Ogilvie MD. Circadian rhythms of body temperature in laboratory and field marmots (Marmota flaviventris). In: Heldmaier G, Klingenspor M, editors. Life in the cold. Springer; Berlin: 2000. pp. 223–231. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman DA, Zucker I. Temperature-independence of circannual variations in circadian rhythms of golden-mantled ground squirrels. J Biol Rhythms. 2000;15:336–343. doi: 10.1177/074873000129001341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuller CA, Lydic R, Sulzman FM, Albers HE, Tepper B, Moore-Ede MC. Circadian rhythm of body temperature persists after suprachiasmatic lesions in the squirrel monkey. Am J Physiol. 1981;241:R385–R391. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1981.241.5.R385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grahn DA, Miller JD, Heller HC (1992) Ambient temperature (Ta) effects the amplitude, but not the tau, of circadian body temperature (Tb) rhythms in golden mantled ground squirrels during hibernation. Soc Res Biol Rhythms, 3rd Meeting, Amelia Island, FL, May.

- 14.Grahn DA, Miller JD, Houng VS, Heller HC. Persistence of circadian rhythmicity in hibernating ground squirrels. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:R1251–R1258. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.266.4.R1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heller HC, Walker JM, Florant GL, Glotzbach SF, Berger RJ. Sleep and hibernation: electrophysiological and thermoregulatory homologies. In: Wang LCH, Hudson JW, editors. Strategies in the cold: natural torpidity and thermogenesis. Academic; New York: 1978. pp. 225–265. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heller HC, Grahn DA, Trachsel L, Larkin LE. What is a bout of hibernation? In: Carey C, Florant GL, Wunder BA, Horwitz B, editors. Life in the cold: ecological, physiological, and molecular mechanisms. Westview; Boulder, CO: 1993. pp. 253–264. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kilduff TS, Radeke CM, Randall TL, Sharp FR, Heller HC. Suprachiasmatic nucleus: phase-dependent activation during the hibernation cycle. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:R605–R612. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.257.3.R605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Körtner G, Song X, Geiser F. Rhythmicity of torpor in a marsupial hibernator, the mountain pygmy-possum (Burramys parvus), under natural and laboratory conditions. J Comp Physiol [B] 1998;168:631–638. doi: 10.1007/s003600050186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.la Fleur SE, Kalsbeek A, Wortel J, Fekkes ML, Buijs RM. A daily rhythm in glucose tolerance: a role for the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Diabetes. 2001;50:1237–1243. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.6.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee TM, Carmichael MS, Zucker I. Circannual variations in circadian rhythms of ground squirrels. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:R831–R836. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1986.250.5.R831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee TM, Zucker I. Seasonal variations in circadian rhythms persist in gonadectomized golden-mantled ground squirrels. J Biol Rhythms. 1995;10:188–195. doi: 10.1177/074873049501000302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindberg RG, Hayden P. Thermoperiodic entrainment of arousal from torpor in the little pocket mouse, Perognathus longimembris. Chronobiologica. 1974;1:356–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lyman CP, Willis JS, Malan A, Wang LCH. Hibernation and torpor in mammals and birds. Academic; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mosko SS, Moore RY. Neonatal suprachiasmatic nucleus lesions: effects on the development of circadian rhythms in the rat. Brain Res. 1979;164:17–38. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagai K, Nagai N, Sugahara K, Niijima A, Nakagawa H. Circadian rhythms and energy metabolism with special reference to the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1994;18:579–584. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(94)90014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruby NF, Heller HC. Temperature sensitivity of the suprachiasmatic nucleus of ground squirrels and rats in vitro. J Biol Rhythms. 1996;11:127–137. doi: 10.1177/074873049601100205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruby NF, Zucker I. Daily torpor in the absence of the suprachiasmatic nucleus in Siberian hamsters. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:R353–R362. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.263.2.R353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruby NF, Nelson RJ, Licht P, Zucker I. Prolactin and testosterone inhibit torpor in Siberian hamsters. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:R123–R128. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.264.1.R123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruby NF, Dark J, Heller HC, Zucker I. Ablation of suprachiasmatic nucleus alters timing of hibernation in ground squirrels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9864–9868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruby NF, Dark J, Heller HC, Zucker I. Suprachiasmatic nucleus: role in circannual body mass and hibernation rhythms of ground squirrels. Brain Res. 1998;782:63–72. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruf T, Steinlechner S, Heldmaier G. Rhythmicity of body temperature and torpor in the Djungarian hamster, Phodopus sungorus. In: Malan A, Canguilhem B, editors. Living in the cold II. John Libbey Eurotext; London: 1989. pp. 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rusak B, Zucker I. Neural regulation of circadian rhythms. Physiol Rev. 1979;59:449–526. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Satinoff E, Prosser RA. Suprachiasmatic nuclear lesions eliminate circadian rhythms of drinking and activity, but not of body temperature, in male rats. J Biol Rhythms. 1998;3:1–22. doi: 10.1177/074873048800300101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strumwasser F. Factors in the pattern, timing, and predictability of hibernation in the squirrel, Citellus beecheyi. Am J Physiol. 1959;196:8–14. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1958.196.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Strumwasser F, Schlechte FR, Streeter J. The internal rhythms of hibernators. Mammalian hibernation III Fisher KC, Dawe AR, Lyman CP, Schonbaum E, South FE. 1967, pp110–139. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd.

- 36.Wollnik F, Schmidt B. Seasonal and daily rhythms of body temperature in the Eur hamster (Cricetus cricetus) under semi-natural conditions. J Comp Physiol [B] 1995;165:171–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00260808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zucker I. Circannual rhythms. In: Takahashi JS, Turek FW, Moore RY, editors. Circadian clocks, Handbook of behavioral neurobiology. Plenum; New York: 2001. pp. 509–528. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zucker I, Boshes M, Dark J. Suprachiasmatic nuclei influence circannual and circadian rhythms of ground squirrels. Am J Physiol. 1983;244:R472–R480. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1983.244.4.R472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zucker I, Ruby NF, Dark J. The suprachiasmatic nucleus mediates rhythms of hibernation and daily torpor in rodents. In: Carey C, Florant GL, Wunder BA, Horwitz B, editors. Life in the cold: ecological, physiological, and molecular mechanisms. Westview; Boulder: 1993. pp. 277–289. [Google Scholar]