Abstract

Hyperammonemia in neonates and infants affects brain development and causes mental retardation. We report that ammonium impaired cholinergic axonal growth and altered localization and phosphorylation of intermediate neurofilament protein in rat reaggregated brain cell primary cultures. This effect was restricted to the phase of early maturation but did not occur after synaptogenesis. Exposure to NH4Cl decreased intracellular creatine, phosphocreatine, and ADP. We demonstrate that creatine cotreatment protected axons from ammonium toxic effects, although this did not restore high-energy phosphates. The protection by creatine was glial cell-dependent. Our findings suggest that the means to efficiently sustain CNS creatine concentration in hyperammonemic neonates and infants should be assessed to prevent impairment of axonogenesis and irreversible brain damage.

Keywords: hyperammonemia, axon, creatine, glia, neurofilament, phosphorylation

Liver failure and genetic defects affecting the urea cycle lead to hyperammonemia with reversible and irreversible neurological damage that might be life-threatening (Podolsky and Isselbacher, 1998; Brusilow and Horwich, 2001). Symptoms of irreversible damage include cognitive impairment, seizures, and cerebral palsy (Flint Beal and Martin, 1998). They mainly occur in cases of prolonged hyperammonemic crises, or when blood ammonium reaches levels between 180 and 500 μm, or both during the first 2 years of life (Msall et al., 1984; Uchino et al., 1998;Bachmann, 2002, 2003). In the few reported brain autopsies of pediatric patients, Alzheimer's type II astrocytes, perivascular spongiosis, and cystic necrosis at the junction of cortical gray and white matter have been observed (Harding et al., 1984; Filloux et al., 1986; Dolman et al., 1988). The mechanisms leading to irreversible alterations are not understood.

We have shown previously that mimicking hyperammonemia by adding ammonium in a rat reaggregating brain cell culture model causes a reduction in aggregate size, which could be caused by a deficiency or developmental delay of cellular processes in regions where axons are prevalent (Braissant et al., 1999b). There is substantial evidence that creatine (Cr) and the Cr/phosphocreatine (PCr)/creatine kinase (CK) system are involved in neuronal growth cone activity and axonal elongation (Wang et al., 1998). In addition, the CNS is the main affected target in infants with a creatine deficiency syndrome attributable to guanidinoacetate methyltransferase, arginine:glycine amidinotransferase, or Cr transporter deficiencies. Such patients exhibit delayed psychomotor development or bilateral myelination delay (Stöckler et al., 1994; Schulze et al., 1997; Item et al., 2001;Salomons et al., 2001). We and others have also shown that the synthesis of arginine, the main precursor of creatine, is altered by hyperammonemia (Rao et al., 1995; Braissant et al., 1999b). Together, these findings suggest that hyperammonemia impairs Cr metabolism, transport in the CNS, or both. Cr is used by the CNS Cr/PCr/CK system to buffer and supply ATP, particularly to neurons (Hemmer and Wallimann, 1993). CNS, at least in the rat, seems dependent on its own Cr synthesis (Braissant et al., 2001).

The aim of the present work was to test whether axons were affected by hyperammonemia and whether this could be caused by a Cr loss or decrease in brain cells. We used reaggregated brain cell cultures prepared from the telencephalon of rat embryos, which provide a three-dimensional network of neurons and glial cells that progressively acquire a tissue-specific pattern resembling that of the brain (Honegger et al., 1979; Honegger and Monnet-Tschudi, 2001). We analyzed the axonal expression of the intermediate neurofilament protein (NF-M, 160 kDa) and determined the intracellular levels of Cr, PCr, ATP, ADP, and AMP under NH4Cl exposure. We identified the neurons impaired in axonal growth by ammonium exposure. Finally, we tested the protective effect of Cr on the growth of axons exposed to NH4Cl, and the influence of the brain cell developmental stage on the axonal vulnerability to ammonium.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reaggregated brain cell cultures. Reaggregated brain cell primary cultures were prepared from mechanically dissociated telencephalon of 16 d rat embryos as described previously (Honegger and Monnet-Tschudi, 2001). Cultures were grown in serum-free, chemically defined medium consisting of DMEM with high glucose (25 mm) supplemented with insulin (0.8 μm), triiodothyronine (30 nm), hydrocortisone-21-phosphate (20 nm), transferrin (1 μg/ml), biotin (4 μm), vitamin B12 (1 μm), linoleate (10 μm), lipoic acid (1 μm),l-carnitine (10 μm), and trace elements (Honegger and Monnet-Tschudi, 2001). Gentamycin sulfate (25 μg/ml) was used as an antibiotic. The cultures were maintained under constant gyratory agitation (80 rpm) at 37°C and in an atmosphere of 10% CO2 and 90% humidified air.

Two different kinds of aggregate cultures were grown: (1) regular mixed cell aggregates, developing with neurons and glial cells; and (2) neuron-enriched aggregates, which were obtained by the treatment of the regular mixed cell cultures at days 1 and 2 with cytosine arabinoside (0.4 μm) to eliminate the proliferating glioblasts (Honegger and Monnet-Tschudi, 2001). Previous work has shown that the neuron-enriched cultures contain >90% neurons, <8% astrocytes and very few, if any, oligodendrocytes (Honegger and Pardo, 1999). Neuron-enriched cultures received conditioned medium taken from mixed cell (neuron–glia) sister cultures and diluted 1:1 with fresh medium.

Aggregates were grown for 13 or 28 d. Aggregates harvested at 13 d were treated from day 5 onward with NH4Cl, Cr, or both, with medium replenishment at days 8 and 11 (5 ml replaced of 8 ml total). Aggregates harvested at 28 d were treated from day 20 onward with NH4Cl, Cr, or both, with medium replenishment at days 22, 24, and 26 (5 ml replaced of 8 ml total). On the day of harvest, culture media were recovered, immediately centrifuged to remove cell debris, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Aggregate pellets were washed three times with ice-cold PBS and embedded for histology or frozen in liquid nitrogen. Until analysis, culture media and aggregate pellets were kept at −80°C.

Histology and immunohistochemistry. Aggregates were embedded in tissue-freezing medium (Jung, Nussloch, Germany), frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane, and kept at −80°C until used. For histological staining, 16-μm-thick cryosections were prepared, postfixed 1 hr in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS, and stained by hematoxylin coloration or Bielschowsky's silver impregnation (Cox, 1977). NN-18 (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA; Shaw et al., 1986;Harris et al., 1991) and RMO-44 (Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, CA) (Lee et al., 1987) monoclonal antibodies were used for immunohistochemistry against NF-M. Axonal growth cones were detected with a monoclonal antibody directed against growth cone-associated protein 43 (GAP43; Chemicon International). Astrocytes and oligodendrocytes were labeled using monoclonal antibodies directed against glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; Chemicon International) and myelin basic protein (MBP; Boehringer Ingelheim). Cholinergic, GABAergic, and glutamatergic neurons were characterized by using monoclonal antibodies against choline acetyltransferase (ChAT; Oncogene, Cambridge, MA), glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD, 65/67 kDa; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and neuronal excitatory amino acid transporter 3 (EAAT3; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), respectively (Furuta et al., 1997; Pardo and Honegger, 1999; He et al., 2000). For immunohistochemistry against NF-M, GAP43, GFAP, GAD, and EAAT3, cryosections (16 μm) were fixed for 1 hr in 4% PFA and PBS at room temperature, washed in PBS (three times for 5 min), and permeabilized for 5 min in 0.1% sodium citrate and 0.1% Triton X-100. For immunohistochemistry against ChAT, cryosections (16 μm) were fixed for 1 min in 5% acetic acid and 95% ethanol at 4°C and washed in PBS (three times for 5 min). For immunohistochemistry against MBP, cryosections (16 μm) were fixed for 1 hr in 4% PFA and PBS at room temperature, washed in PBS (three times for 5 min), dehydrated with increasing concentrations of ethanol (EtOH), delipidated in xylene, rehydrated with decreasing concentrations of EtOH, and finally washed in PBS. Sections were then processed for immunohistochemistry using the Histostain-Plus kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Zymed). The primary antibody was diluted in 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS and applied to sections. After washing, sections were incubated with a biotinylated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody followed by a streptavidin-peroxidase conjugate. Peroxidase staining was performed for 10 min using aminoethyl carbazole and H2O2 and stopped in distilled water. Sections were mounted under glycerol and observed and photographed on an Olympus BX50 microscope equipped with a DP-10 digital camera (Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan).

Protein dephosphorylation on cryosections. Cryosections (16 μm thick) were digested for 30 min (37°C) with alkaline phosphatase (200 μg/ml; Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany), in (in mm): 100 Tris, 100 NaCl, and 50 MgCl2, pH 9.5. Sections were washed in PBS, fixed for 30 min in 4% PFA and PBS, and washed three times for 5 min in PBS. Immunohistochemistry against NF-M was then performed as described above.

Quantitative Western blot analysis. Mixed cell and neuron-enriched aggregates were homogenized in 10 mmTris-HCl, pH 7.5, containing 4 m urea, 0.1% SDS, and protease inhibitors (Complete; Roche). Homogenates were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min, and supernatants were recovered. Supernatant proteins were measured by the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and diluted at a final concentration of 1 μg/μl in Laemmli sample buffer (Laemmli, 1970). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (9% total acrylamide). After transfer of the proteins to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Immobilon; Millipore, Bedford, MA), blots were probed with NN-18 and RMO-44 anti-NF-M, anti-GAP43, and anti-GFAP monoclonal antibodies. Western blots were revealed by chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK). The radiographs (X-OMAT AR; Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) were scanned with an ImageScanner (Amersham Biosciences) and processed by image analysis (ImageMaster 1D; Amersham Biosciences).

Measure of intracellular Cr, PCr, ATP, ADP, and AMP. Frozen aggregate pellets were suspended in ice-cold 25 mmphosphate buffer, pH 7.5 containing (in mm): 1 iodoacetate and 0.1 diadenosine pentaphosphate. Cells were extracted with 0.4m perchloric acid and neutralized with 2 mK2CO3 followed by a centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 5 min. Supernatants were assayed for adenine nucleotides (ATP, ADP, and AMP) and creatine compounds (Cr and PCr) according to the isocratic reversed phase HPLC method of Seidl et al. (2000) using HPLC (Agilent) coupled with a dual-absorbance detector. The absorbance at 214 nm (for Cr and PCr) and that at 254 nm (for ATP, ADP, and AMP) were monitored simultaneously. The acid precipitates of the aggregates were solubilized in 0.1m NaOH and 1% SDS, and their protein content was determined by the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce). The concentrations of Cr, PCr, ATP, ADP, and AMP were expressed as nanomoles per milligram of protein.

Measure of NH , glucose, and lactate in culture media. Ammonium was measured on a Cobas FARA II automate (Roche), using a UV enzymatic ammonium kit (61025; Biomérieux). Glucose and lactate were measured on a Hitachi 917 automate (Roche), using the Glucose Ecoline 100 kit (1.14891.0001; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and a lactate kit (1 822 837; Roche).

RESULTS

Net uptake of NH and glucose and net release of lactate by mixed cell aggregate cultures exposed to NH4Cl are shown in Table1. During the whole period of NH4Cl exposure, NH uptake by cultures was dose-dependent. Glucose uptake and lactate release showed highly significant increases at the maximal dose of 5 mmNH4Cl. The extent of metabolic changes observed with increasing NH4Cl concentrations paralleled morphological changes in the aggregates, which were absent or barely detectable at 1 and 2.5 mm NH4Cl (data not shown) but evident at 5 mm (see below). Therefore, morphological and biochemical effects of hyperammonemia were further analyzed by treating aggregate cultures with 5 mmNH4Cl.

Table 1.

NH4Cl dose-dependent uptake and release of ammonium, glucose, and lactate by mixed cell aggregate cultures

| NH4Cl (mm) | Days 5–8 | Days 8–11 | Days 11–13 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | p | p | ||||

| Ammonium | ||||||

| 0 | −26 ± 1 | −4 ± 1 | −2 ± 1 | |||

| 1.0 | −55 ± 13 | <0.001 | −31 ± 4 | <0.001 | −38 ± 1 | <0.001 |

| 2.5 | −113 ± 19 | <0.001 | −96 ± 2 | <0.001 | −114 ± 1 | <0.001 |

| 5.0 | −176 ± 16 | <0.001 | −250 ± 2 | <0.001 | −264 ± 10 | <0.001 |

| Glucose | ||||||

| 0 | −399 ± 19 | −464 ± 12 | −756 ± 4 | |||

| 1.0 | −372 ± 32 | NS | −389 ± 22 | <0.01 | −656 ± 48 | <0.05 |

| 2.5 | −525 ± 32 | <0.01 | −468 ± 7 | NS | −835 ± 17 | <0.01 |

| 5.0 | −672 ± 21 | <0.001 | −623 ± 19 | <0.001 | −1026 ± 7 | <0.001 |

| Lactate | ||||||

| 0 | 137 ± 5 | 166 ± 6 | 685 ± 26 | |||

| 1.0 | 152 ± 18 | NS | 149 ± 39 | NS | 549 ± 21 | <0.01 |

| 2.5 | 269 ± 22 | <0.001 | 153 ± 22 | NS | 696 ± 73 | NS |

| 5.0 | 431 ± 34 | <0.001 | 370 ± 41 | <0.001 | 1137 ± 22 | <0.001 |

Net uptake (net decrease in culture medium) and release (net increase in culture medium) by aggregates, calculated from days 5–8, 8–11, and 11–13 are expressed as nanomoles per hour per milligram of protein. Measures were taken at days 5 (start of treatment), 8 (before and after medium change), 11 (before and after medium change), and 13 (end of treatment). Proteins were measured at day 13. Data are means ± SD of three separate cultures. Statistical pvalues are shown (Student's t test) for comparison with controls (NH4Cl = 0 mm); NS, not significant.

NH4Cl exposure impaired axonal growth in developing mixed cell aggregates

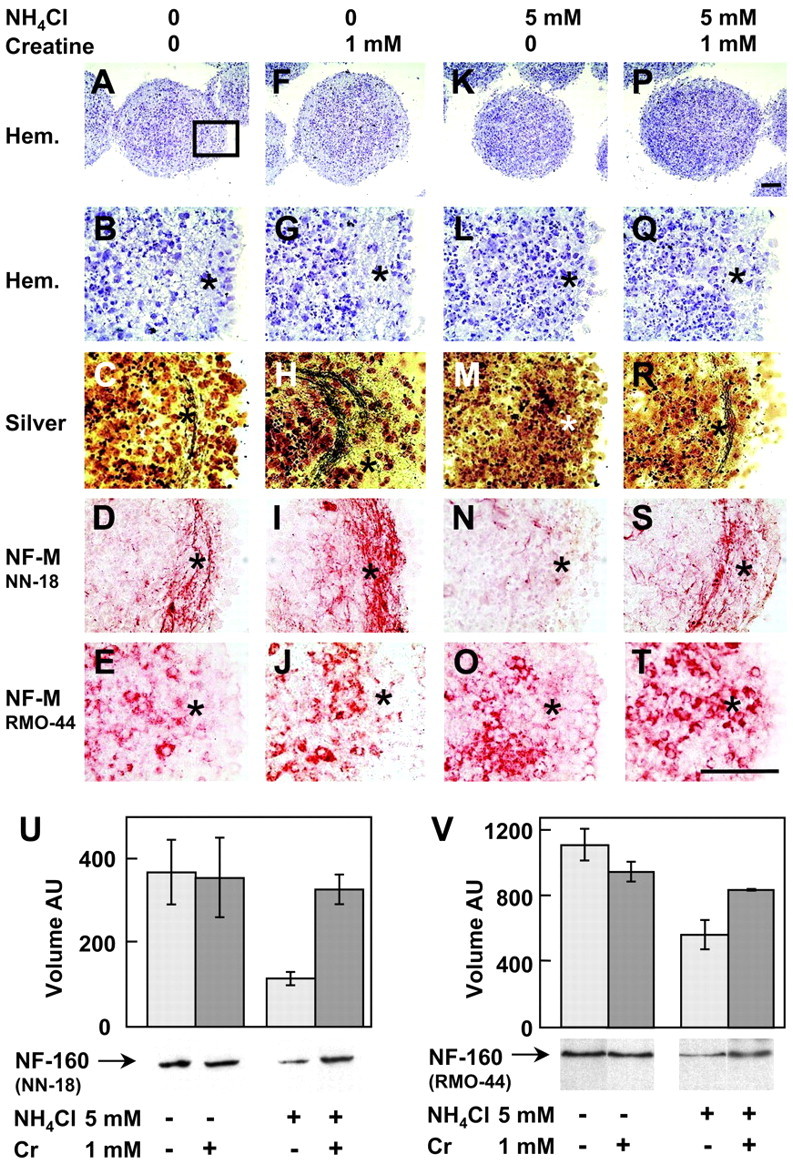

Control mixed cell aggregate cultures at day 13 presented a characteristic distribution of cells, including a peripheral zone with a low density of cell bodies (Fig.1A,B,asterisk) in which fibers were prevalent (Fig.1C). These fibers were NF-M-positive, using the monoclonal anti-NF-M NN-18 antibody, which did not stain neuronal soma (Fig.1D). Aggregates exposed to 5 mmNH4Cl from days 5 to 13 showed more densely packed cell bodies at their periphery (Fig. 1K,L), and the almost complete absence of NF-M-positive fibers (Fig.1M,N). Another monoclonal anti-NF-M antibody, RMO-44, localized NF-M in neuronal cell bodies but not in fibers (Fig.1E). The somatic expression of NF-M was not altered by 5 mm NH4Cl exposure (Fig. 1O). Western blot analysis of NF-M showed that NH4Cl exposure caused a drastic decrease of NF-M (threefold using NN-18, Fig. 1U; and twofold using RMO-44, Fig. 1V).

Fig. 1.

Axons are missing and NF-M is decreased in NH4Cl-exposed day 13 mixed cell aggregates. Creatine, added to NH4Cl exposure, rescues axons and NF-M. Cultures were grown from days 5 to 13 with or without (in mm): 5 NH4Cl, 1 Cr, or both. Cryosections were stained by hematoxylin (Hem.; A, B, F, G, K, L, P, Q), Bielschowsky's silver impregnation (Silver;C, H, M, R), and immunohistochemistry against NF-M (D, I, N, S, NN-18 antibody; E, J, O, T, RMO-44 antibody). A–E, Controls; F–J, Cr; K–O, NH4Cl; P–T, NH4Cl + Cr. B–E, G–J, L–O, Q–T, Higher magnifications of the area depicted in A. The dense peripheral axonal zone is indicated by an asterisk. Scale bar, 100 μm. U, V, NF-M analysis by Western blotting with NN-18 (U; 20 μg of protein/lane) and RMO44 (V; 10 μg of protein/lane) antibodies. Values are means ± SD of three separate cultures.AU, Arbitrary units.

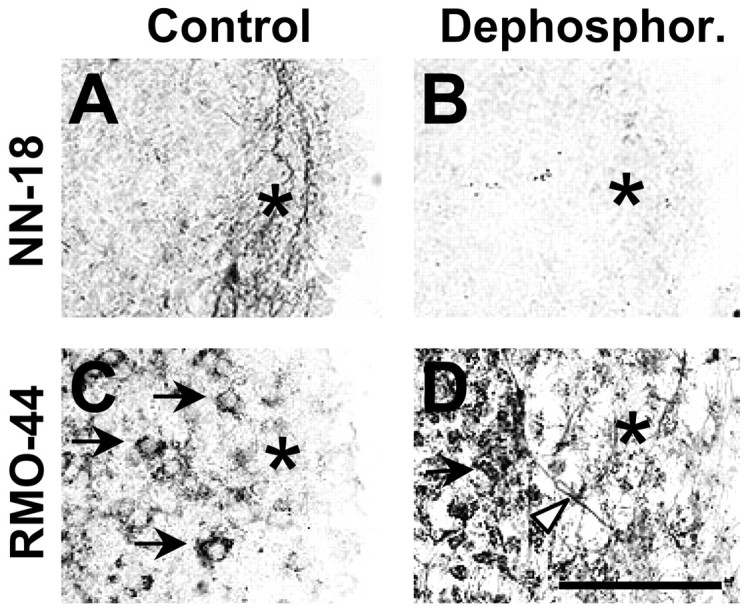

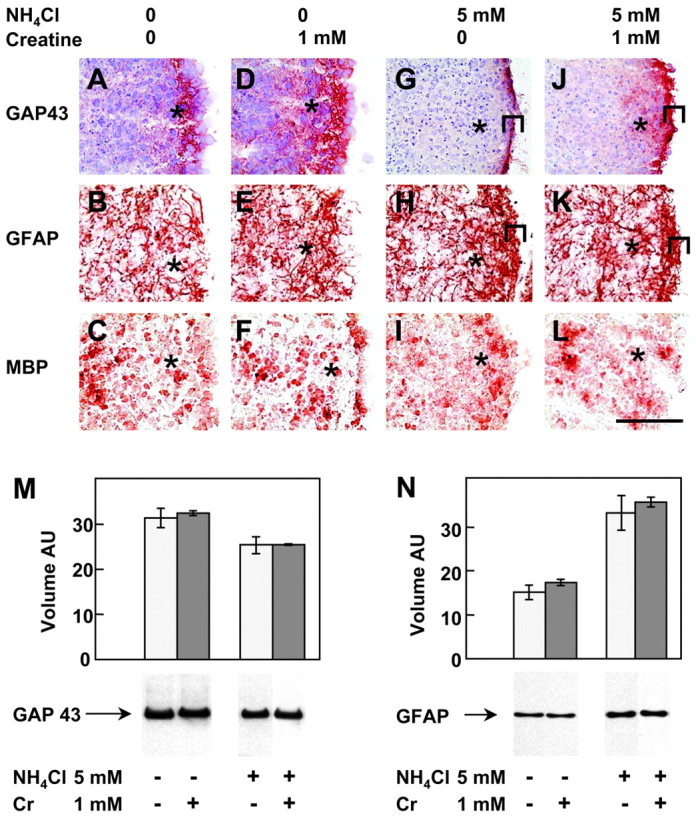

The specificity of NN-18 and RMO-44 antibodies for NF-M recognition was further characterized by dephosphorylation of proteins in situ using alkaline phosphatase. Dephosphorylation abolished most of the NN-18 staining in fibers of the aggregate periphery (Fig.2A,B) and induced RMO-44 NF-M immunoreactivity in distal fibers located at the aggregate periphery and in proximal fibers connecting neuronal cell bodies to the aggregate periphery (Fig. 2C,D). This indicates that NN-18 predominantly recognized phosphorylated NF-M, whereas RMO-44 predominantly recognized nonphosphorylated NF-M. Thus, the absence of NN-18 anti-NF-M staining after NH4Cl exposure (Fig. 1N) suggests that ammonium exposure inhibited NF-M phosphorylation. Fibers located at the aggregate periphery and containing phosphorylated NF-M were most probably axons, as suggested by analyzing the expression of GAP43, an axonal growth cone marker. In control day 13 mixed cell aggregates, GAP43 was highly expressed in the same peripheral zone, exhibiting strong NF-M staining by NN-18 (Fig.3A). As for NF-M, the GAP43 staining was lost in this region after NH4Cl exposure (Fig. 3G). Interestingly, a strongly GAP43-immunoreactive zone appeared at the border of the aggregates (Fig. 3G, bracket). Western blotting analysis of GAP43 after NH4Cl exposure showed a small decrease of the GAP43 signal (−20%) (Fig. 3M).

Fig. 2.

NN-18 and RMO-44 anti-NF-M antibodies recognize phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated NF-M, respectively, in native conformation. Mixed cell aggregates were used at 13 d of culture.A, C, Controls; B, D, dephosphorylation (Dephosphor.) by alkaline phosphatase. Cryosections were stained by immunohistochemistry against NF-M (A, B, NN-18 antibody; C, D, RMO-44 antibody). Arrow, Neuronal cell body;arrowhead, proximal axon, arising from the neuronal cell body and growing toward aggregate periphery; asterisk, peripheral zone enriched in axons. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Fig. 3.

GAP43, an axonal growth cone marker, is decreased by NH4Cl exposure and rescued by Cr cotreatment in the peripheral axonal zone of the aggregates. Ammonium exposure induces GAP43 and increases GFAP in reactive astrocytes of the aggregate border. Cultures were treated from days 5 to 13 with or without (in mm): 5 NH4Cl, 1 Cr, or both. Cryosections were stained by immunohistochemistry against GAP43 (A, D, G, J), GFAP (B, E, H, K), and MBP (C, F, I, L). A, D, G, J were counterstained by hematoxylin. A–C, Controls;D–F, Cr; G–I, NH4Cl;J–L, NH4Cl + Cr. The dense peripheral axonal zone is indicated by an asterisk. Highly GFAP-positive astrocytes in the border of aggregates are shown bybrackets. Scale bar, 100 μm. M,N, GAP43 (M) and GFAP (N) analysis by Western blotting (10 μg of protein per lane). Values are means ± SD of three separate cultures. AU, Arbitrary units.

In day 13 mixed cell aggregates, glial cells were identified by immunohistochemical staining for GFAP (specific for astrocytes) (Fig. 3B) and MBP (specific for oligodendrocytes) (Fig. 3C). NH4Cl exposure increased the number of GFAP-positive astrocytic processes, particularly at the aggregate border (Fig. 3H,bracket), whereas no significant effect was found for oligodendrocytes (Fig. 3I). Western blotting analysis of GFAP after NH4Cl exposure showed a 2.2-fold increase of the GFAP signal (Fig. 3N).

NH4Cl exposure decreased intracellular Cr, PCr, and ADP in developing mixed cell aggregates

To test whether energy-rich phosphates, the Cr/PCr/CK system, or both were involved in ammonium-induced axonal growth impairment, we measured intracellular levels of Cr, PCr, ATP, ADP, and AMP in mixed cell aggregates (Table 2). NH4Cl exposure reduced Cr, PCr, and ADP significantly (83, 75, and 69% of controls, respectively), whereas no significant effect was observed for ATP and AMP content.

Table 2.

Intracellular creatine, phosphocreatine, ATP, ADP, and AMP in mixed cell aggregates at day 13 of culture

| Treatments NH4Cl (mm) Creatine (mm) | Control 0 0 | Cr 0 1 | NH4Cl 5 0 | NH4Cl + Cr 5 1 | Comparisons (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NH4Cl versus controls | NH4Cl + Cr versus NH4Cl | |||||

| Creatine | 178.6 ± 5.8 | 340.2 ± 3.5 | 147.7 ± 4.1 | 255.5 ± 25.6 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Phosphocreatine | 13.0 ± 0.4 | 12.1 ± 0.3 | 9.7 ± 0.8 | 9.8 ± 0.5 | <0.05 | NS |

| ATP | 5.5 ± 0.7 | 7.0 ± 0.9 | 4.5 ± 2.1 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | NS | NS |

| ADP | 39.3 ± 2.3 | 37.6 ± 2.9 | 27.2 ± 1.5 | 29.1 ± 3.8 | <0.01 | NS |

| AMP | 17.2 ± 0.4 | 18.8 ± 1.4 | 19.6 ± 7.3 | 15.3 ± 4.2 | NS | NS |

Data are expressed as nanomoles per milligram of protein and are means ± SD of three separate cultures. Statistical pvalues are shown (Student's t test); NS, not significant.

Creatine prevented NH4Cl-induced axonal growth impairment in developing mixed cell aggregates

Because Cr and PCr were decreased in NH4Cl-exposed aggregates, we examined whether Cr had a protective effect on axonal growth under NH4Cl exposure. By immunohistochemistry with the NN-18 antibody, we found indeed that 1 mm Cr added to NH4Cl-exposed aggregates protected the peripheral axons, their expression of NF-M, and NF-M phosphorylation (Fig.1P–S, see controls, A–D, NH4Cl exposure, K–N), whereas Cr given alone increased the density of NF-M-positive peripheral axons (Fig. 1F–I). Immunohistochemistry with RMO-44 did not reveal any difference in NF-M expression between aggregates treated with Cr and controls (Fig. 1J,E) or between NH4Cl + Cr- and NH4Cl-exposed aggregates (Fig.1O,T). Analysis of NF-M by Western blotting showed that Cr cotreatment maintained NF-M at control levels in mixed cell aggregates exposed to NH4Cl (NN-18) (Fig.1U) or showed partial protection (RMO-44, −25% compared with controls, +50% compared with NH4Cl exposure) (Fig. 1V), whereas Cr exposure alone did not affect the NF-M level compared with controls (Fig.1U,V). A higher concentration of Cr (25 mm) was also tested, which did not improve the protection of axonal growth under ammonium exposure compared with that obtained with 1 mm Cr (data not shown).

GAP43 expression was partially protected in the peripheral NF-M-positive region of NH4Cl-exposed aggregates cotreated with Cr (Fig. 3J, asterisk, see control, A, NH4Cl exposure,G). However, the border of the aggregates was strongly positive for GAP43, as after exposure to NH4Cl alone (Fig. 3J,G, bracket). Compared with controls, Cr given alone increased the GAP43 signal in the center of the aggregates (Fig. 3A,D). By Western blot analysis, no difference was observed for GAP43 expression between Cr-exposed cultures and controls or between NH4Cl + Cr- and NH4Cl-exposed cultures (Fig.3M). Astrocytes and oligodendrocytes presented similar patterns of expression for GFAP and MBP in cultures treated with Cr and in controls (Fig. 3, B,E, GFAP, C,F, MBP) as well as in NH4Cl + Cr- and NH4Cl-treated aggregates (Fig. 3, H,K, GFAP, I,L, MBP).

No restoration of or increase in intracellular PCr, ATP, or ADP could be observed in mixed cell aggregates cotreated with (in mm): 5 NH4Cl and 1 Cr compared with cultures exposed to NH4Cl only (Table 2), whereas intracellular Cr was increased significantly (170% of controls). Cr was efficiently taken up by mixed cell aggregates exposed to 1 mm Cr only (190% of controls; p < 0.001); however, their PCr, ATP, and ADP content was not modified. NH4Cl induced a significant decrease of intracellular Cr in aggregates exposed to 1 mm Cr (75% of Cr-alone exposure; p < 0.005).

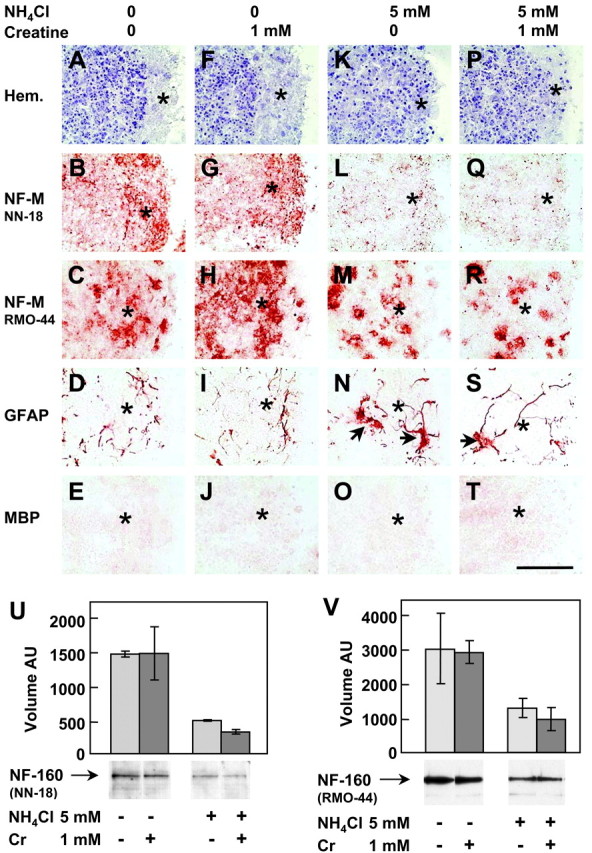

Creatine did not prevent the NH4Cl-induced axonal growth impairment in developing neuron-enriched aggregates

Untreated neuron-enriched aggregate cultures also developed a peripheral zone with a low density of cell bodies but devoid of the glial cell lining found at the border of mixed cell aggregates (Figs.4A vs 1B; also compare staining for GFAP, Figs.4D vs 3B, and MBP, Figs.4E vs 3C). As in mixed cell cultures, the number of axons that developed in the aggregate periphery of day 13 neuron-enriched aggregates (Fig. 4B) was decreased under NH4Cl exposure, as was NF-M phosphorylation (Fig. 4K,L). In contrast to mixed cell cultures, however, Cr cotreatment of neuron-enriched cultures did not prevent the NH4Cl-induced axonal growth impairment or the decrease of NF-M phosphorylation (Fig. 4P,Q, see controls,A,B, and NH4Cl exposure,K,L). In contrast to mixed cell cultures, Cr given alone did not change the density of NF-M positive axons (Fig.4F,G, see controls, A,B). Similar densities of NF-M-positive neuronal cell bodies stained with RMO-44 were found in controls and NH4Cl- and NH4Cl + Cr-exposed, neuron-enriched aggregates (Fig. 4C,M,R). However, exposure to Cr alone caused an increased density of neuronal cell bodies as well as a less intense staining of the nonphosphorylated NF-M around the cell nucleus (Fig.4H). Analysis by Western blotting and staining with either NN-18 or RMO-44 showed that NF-M was quantitatively decreased in NH4Cl-exposed, neuron-enriched aggregates and that Cr cotreatment of NH4Cl-exposed cultures did not protect NF-M expression (Fig.4U,V).

Fig. 4.

Cr added to NH4Cl-exposed day 13 neuron-enriched aggregates does not rescue developing axons and NF-M levels. Cultures were treated from days 5 to 13 with or without (in mm): 5 NH4Cl, 1 Cr, or both. Cryosections were stained by hematoxylin (A, F, K, P) and immunohistochemistry against NF-M (B, G, L, Q, NN-18 antibody; C, H, M, R, RMO-44 antibody), GFAP (D, I, N, S), and MBP (E, J, O, T).A–E, Controls; F–J, Cr;K–O, NH4Cl; P–T, NH4Cl + Cr. The dense peripheral axonal zone is indicated by an asterisk. Arrows point to GFAP-positive giant astrocytes in NH4Cl-exposed cultures. Scale bar, 100 μm. U, V, NF-M analysis by Western blotting with NN-18 (U; 20 μg of protein per lane) and RMO44 (V; 10 μg of protein per lane) antibodies. Values are means ± SD of three separate cultures.AU, Arbitrary units.

The presence of few remaining astrocytes in neuron-enriched cultures was confirmed by anti-GFAP labeling (Fig. 4D; see mixed cell cultures, Fig. 3B). NH4Cl exposure (with or without Cr cotreatment) did not change the density of GFAP-positive astrocytic processes but caused an increase in the size of astrocyte cell bodies, reminiscent of Alzheimer's type II astrocytes (Fig. 4N,S, arrows, see controls,D). Exposure to Cr alone did not modify the GFAP level, the astrocyte soma diameter, or the astrocytic process density (Fig.4I, see controls, D). The complete absence of oligodendrocytes in neuron-enriched aggregates was confirmed by anti-MBP staining in both controls and treated cultures (Fig.4E,J,O,T).

Creatine and phosphocreatine levels in neuron-enriched cultures were not altered by NH4Cl exposure

In control conditions, the Cr concentration found in neuron-enriched aggregates was 10-fold lower than in mixed cell cultures (compare Tables 2, 3), suggesting that neurons had a limited capacity to synthesize Cr. In contrast to mixed cell aggregates, NH4Cl exposure of neuron-enriched cultures did not affect intracellular Cr and PCr (Table 3), but ATP, ADP, and AMP were significantly lower (67, 58, and 50% of controls, respectively). Cr cotreatment did not attenuate the NH4Cl-induced decrease of adenine nucleotides, nor did it modify the PCr concentration (Table 3). Neuron-enriched cultures were able to take up Cr efficiently, because exposure to 1 mm Cr increased intracellular Cr 8.4-fold when compared with control levels (Table 3; p < 0.001; compare with 1.9-fold only in mixed cell cultures, Table 2) and 3.5-fold when comparing NH4Cl + Cr- with NH4Cl-exposed cultures (p< 0.01). NH4Cl caused a significant decrease of Cr in neuron-enriched aggregates exposed to 1 mmCr (40% of Cr-alone exposure; p < 0.005).

Table 3.

Intracellular creatine, phosphocreatine, ATP, ADP, and AMP in neuron-enriched aggregates at day 13 of culture

| Treatments NH4Cl (mm) Creatine (mm) | Control 0 0 | Cr 0 1 | NH4Cl 5 0 | NH4Cl + Cr 5 1 | Comparisons (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NH4Cl versus controls | NH4Cl + Cr versus NH4Cl | |||||

| Creatine | 17.4 ± 2.0 | 138.6 ± 17.9 | 16.3 ± 1.6 | 56.2 ± 9.3 | NS | <0.01 |

| Phosphocreatine | 4.4 ± 1.9 | 6.8 ± 2.1 | 4.1 ± 0.7 | 4.8 ± 1.6 | NS | NS |

| ATP | 6.7 ± 0.9 | 9.1 ± 0.6 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 4.3 ± 0.8 | <0.05 | NS |

| ADP | 3.3 ± 0.4 | 3.7 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | <0.05 | NS |

| AMP | 7.6 ± 1.1 | 9.4 ± 2.0 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 3.7 ± 0.1 | <0.01 | NS |

Data are expressed as nanomoles per milligram of protein and are means ± SD of three separate cultures. Statistical pvalues are shown (Student's t test); NS, not significant.

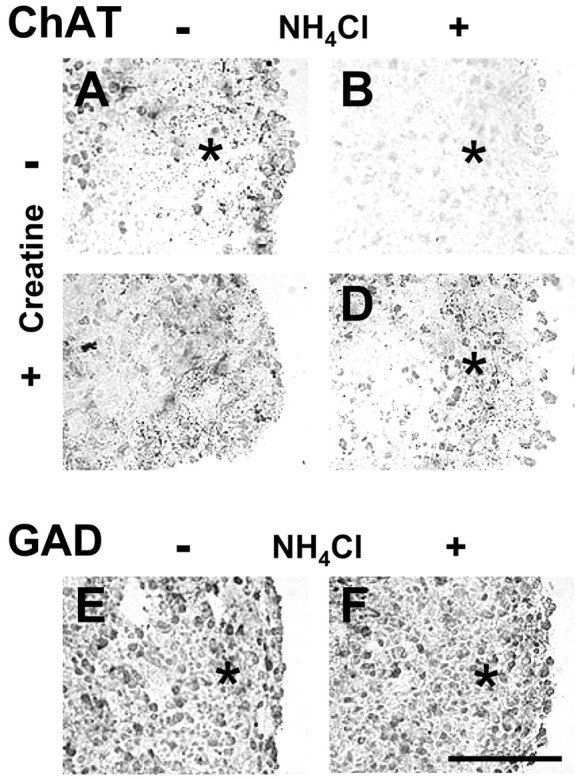

Neurons affected by NH4Cl exposure in day 13 mixed cell aggregates are cholinergic

The neuronal identity of axons affected by NH4Cl was analyzed by immunohistochemistry against ChAT, GAD 65/67 kDa, and EAAT3 to discriminate between cholinergic, GABAergic, and glutamatergic neurons, respectively. ChAT was expressed in neuronal cell bodies of day 13 aggregates as well as in punctuate formations localized in the peripheral zone where axons grow (Fig. 5A). After NH4Cl exposure, ChAT immunostaining decreased in the peripheral axonal region (Fig. 5B) but was maintained in aggregates exposed to NH4Cl + Cr (Fig.5D). Cr alone did not modify the punctuate staining of ChAT in the aggregate periphery but increased it in neuronal cell bodies (Fig. 5C). GAD 65/67 kDa was localized in numerous neuronal cell bodies, and its expression was not modified by NH4Cl (Fig. 5E,F). At day 13, no expression of the glutamate transporter EAAT3 could be detected in the aggregates (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Cholinergic axons of day 13 mixed cell aggregates are affected by NH4Cl exposure and rescued by Cr cotreatment. Aggregates were treated from days 5 to 13 with or without (in mm): 5 NH4Cl, 1 Cr, or both. Immunohistochemistry against ChAT (A–D) and GAD 65/67 kDa (E, F) was performed. A, E, Controls; B, F, NH4Cl;C, Cr; D, NH4Cl + Cr. The dense peripheral axonal zone is indicated by anasterisk. Scale bar, 100 μm.

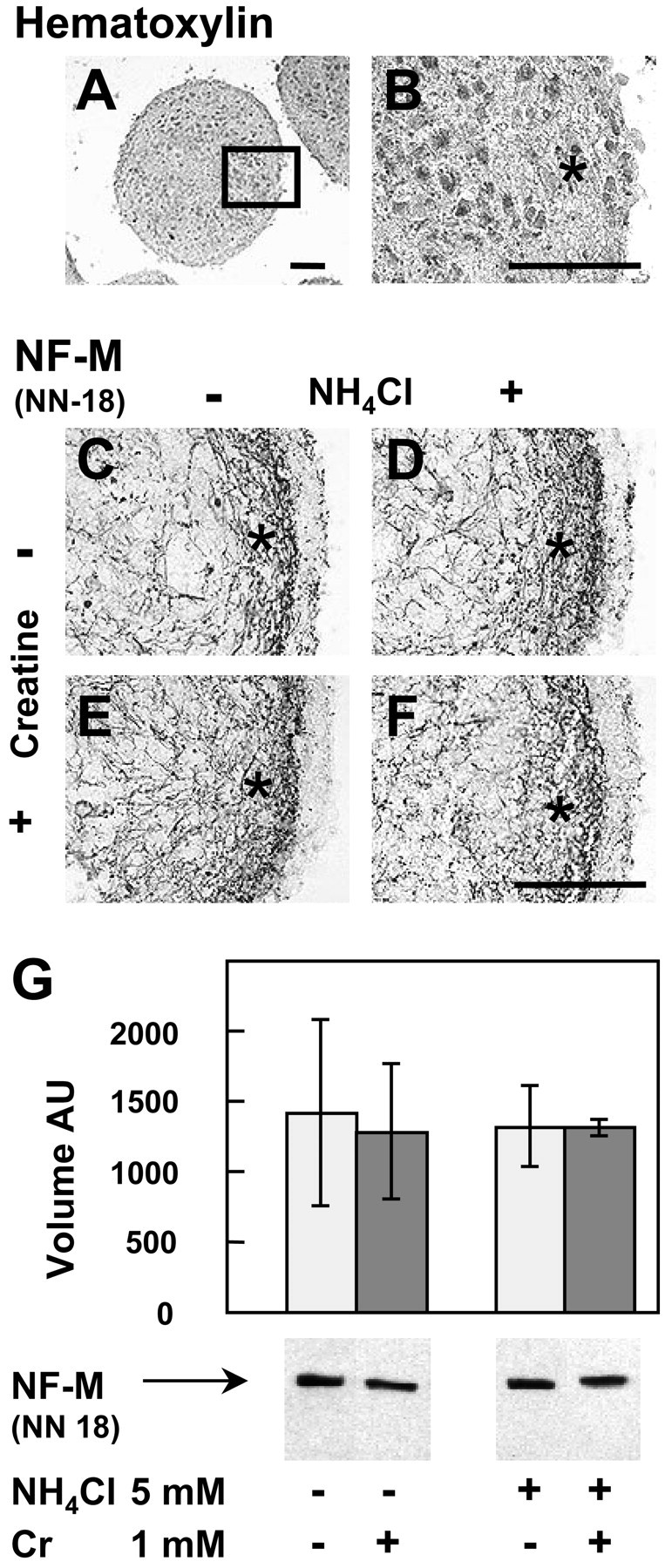

NH4Cl and creatine exposure did not alter axons of mature mixed cell aggregates

To investigate whether NH4Cl also affected axons in mature neurons, aggregates were exposed to (in mm): 5 NH4Cl, 1 Cr, or both from days 20 to 28, i.e., at a stage at which neurons progressively undergo synaptogenesis and myelination (Honegger and Monnet-Tschudi, 2001). At day 28, the peripheral dense fiber zone was clearly visible (Fig.6A,B) and richer in the number of axons expressing NF-M than at day 13 (Fig. 6C; compare with Fig. 1D). NH4Cl (5 mm) exposure did not affect axons of mature aggregates (Fig. 6D). Aggregates treated with 1 mm Cr (Fig. 6E) or with NH4Cl + Cr (Fig. 6F) were also comparable with control aggregates (Fig. 6C). Quantitative analysis of NF-M by Western blotting, using NN-18, did not reveal any significant difference between controls and treated cultures (Fig.6G).

Fig. 6.

NH4Cl and Cr do not affect axons and NF-M in day 28 mature mixed cell aggregates. Cultures were treated from days 20 to 28 with or without (in mm): 5 NH4Cl, 1 Cr, or both. A, B, Hematoxylin staining of day 28 control aggregates at low (A) and high (B) magnification. C–F, Immunohistochemistry against NF-M (NN-18 antibody). C, Control; D, NH4Cl; E, Cr; F, NH4Cl + Cr. B–F, Higher magnifications of the area depicted in A. The dense peripheral axonal zone is indicated by an asterisk. Scale bar, 100 μm.G, NF-M analysis by Western blotting (NN-18 antibody; 15 μg of protein per lane). Values are means ± SD of three separate cultures. AU, Arbitrary units.

DISCUSSION

Ammonium exposure impairs cholinergic axonal growth, decreases NF-M, and inhibits NF-M phosphorylation

We provide the first experimental demonstration of neuronal fiber growth impairment under ammonium exposure, together with a decrease in NF-M protein and an inhibition of NF-M phosphorylation. This is in line with the growing number of recently described neurological pathologies showing abnormal expression or phosphorylation of neuronal cytoskeleton proteins such as NFs or microtubule-associated proteins (Hirokawa and Takeda, 1998; Julien, 1999; Saez et al., 1999; Sanchez et al., 2000). Our results are consistent with clinical findings in hyperammonemic neonates or infants with brain lesions compatible with neuronal fiber loss or defects of neurite outgrowth, such as cortical atrophy, ventricular enlargement, demyelination, or gray and white matter hypodensities (Harding et al., 1984; Msall et al., 1984; Wakamoto et al., 1999), which can be acquired in utero (Filloux et al., 1986).

Understanding ammonium toxicity to neurons implied identification of impaired NF-M-positive fibers. NN-18 and RMO-44 anti-NF-M antibodies are directed against phosphorylation-independent epitopes, and both equally recognize NF-M in denaturing SDS-PAGE conditions (Lee et al., 1987; Harris et al., 1991; this work). On cryosections, however, we showed that NN-18 stained fibers but not neuronal cell bodies, whereas RMO-44 stained neuronal soma but not fibers. Moreover, we showed that protein dephosphorylation on cryosections suppressed the staining of fibers by NN-18 but induced it by RMO-44. Thus, both antibodies recognize nonphosphorylated epitopes that are exposed or not depending on changes of NF-M conformation because of its level of phosphorylation. On histological sections, the epitope recognized by NN-18 appears to be exposed only when NF-M is phosphorylated, whereas that recognized by RMO-44 seems exposed only when NF-M is nonphosphorylated. Accordingly, fibers at aggregate periphery preferentially contain phosphorylated NF-M, whereas neuronal soma essentially contain nonphosphorylated NF-M. Our findings may explain why NN-18 does not stain neuronal soma except in cases of hyperphosphorylated NF-M accumulation (Harris et al., 1991; Nguyen et al., 2001) and why RMO-44 preferentially labels neuronal soma (Lee et al., 1987).

NFs are distributed in neuronal soma, dendrites, and axons. Nonphosphorylated NFs are predominantly found in the somatodendritic compartment, whereas phosphorylated NFs are enriched in axons (Rosenstein and Krum, 1996; Brown, 1998; Ulfig et al., 1998). Moreover, GAP43 and ChAT showed a localization similar to that of NN-18-stained NF-M and reacted like it under exposure to NH4Cl, Cr, or both. GAP43 is found in growth cones of axons exclusively (Goslin et al., 1988), and ChAT is recognized as a presynaptic axonal marker (Phelps et al., 1985). Together, these data suggest that NN-18 stained axons specifically.

Cholinergic, GABAergic, and glutamatergic neurons differentiate in the brain aggregate culture system (Pardo and Honegger, 1999; Honegger and Monnet-Tschudi, 2001). Data presented here suggest that early in development, axons impaired by NH4Cl belong to cholinergic neurons. This does not exclude the possibility that ammonium could also impair axonal growth of glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons later in development, because glutamatergic neurotransmission and GAD activity are altered by hyperammonemia (Albrecht, 1998;Braissant et al., 1999b). Our findings are in line with data obtained in the spf mouse, a model of hyperammonemia caused by ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency, which shows cholinergic neuronal loss in the cerebral cortex (Ratnakumari et al., 1994). Lack of elongation of cholinergic axons during cortical development may provide a basis for understanding some of the severe cognitive defects caused by hyperammonemia.

NH4Cl-induced inhibition of axonal growth depends on intracellular Cr

NH4Cl exposure of day 13 mixed cell aggregates impaired axonal growth and decreased intracellular levels of Cr, PCr, and ADP. Cr cotreatment under NH4Cl exposure protected axonal growth but neither restored nor increased PCr, ATP, and ADP levels. This suggests that under NH4Cl exposure, the rescue of axonal growth by Cr does not depend on high-energy phosphates, which remain lowered under NH4Cl + Cr exposure and are known to decrease in the hyperammonemic CNS (Ratnakumari et al., 1992). We cannot exclude, however, the possibility that concentration changes in specific cell types or in subcellular compartments (e.g., mitochondria) remain undetected. Intracellular Cr was decreased by 60% in neuron-enriched but only by 25% in mixed cell aggregates exposed to NH4Cl + Cr compared with Cr exposure, suggesting that NH4Cl exposure reduced the capacity to accumulate Cr in neurons preferentially.

Glial dependency of axonal protection by creatine under NH4Cl exposure

Cr added to the culture medium was sufficient to protect axonal growth in NH4Cl-exposed mixed cell aggregates but not in neuron-enriched cultures, suggesting that the mechanism of axon protection by Cr depends on glial cells, be it astrocytes or oligodendrocytes. In the case of an astrocyte-dependent mechanism, the very few astrocytes still present in neuron-enriched cultures might suffice for supporting axonal growth in control conditions but not for protecting axons exposed to NH4Cl. The absence of oligodendrocytes in neuron-enriched cultures might also suggest an oligodendrocyte-dependent mechanism. Because Cr is taken up by neuron-enriched cultures without protecting axons exposed to NH4Cl, it is unlikely that Cr per se is the sole glia-derived axonal growth-promoting factor. Our findings preferentially support the hypothesis that a glial factor is needed, which is modified through Cr in glial cells (e.g., by the Cr/PCr/CK system), released, and used by neurons to promote axonal growth. This would still allow axonal growth in control neuron-enriched cultures, because they are grown in a culture medium conditioned by mixed cell cultures (Honegger and Monnet-Tschudi, 2001). Because we have shown that axons do not grow in neuron-enriched aggregates exposed to ammonium, it also implies that NH4Cl has a direct neuronal inhibitory effect on axonal growth that cannot be prevented in the absence of glial cells but is counteracted by Cr cotreatment in mixed cell aggregates.

The glial mechanism of axonal growth protection might involve protein phosphorylation, which is directly linked to cell content in high-energy phosphates and the Cr/PCr/CK system and altered in glial cells under ammonium exposure (Neary et al., 1987; Schliess et al., 2002) and was proposed as a main signaling pathway in axon–glia inter-relationships (Witt and Brady, 2000). Cr-dependent modification of glial protein phosphorylation could support axonal growth, which per se is regulated through phosphorylation of axonal cytoskeleton proteins (e.g., NFs) under direct influence of oligodendrocytes (de Waegh et al., 1992). Such a mechanism is supported by our data, namely, the NH4Cl-induced inhibition of NF-M phosphorylation that is counteracted by a Cr cotreatment.

NH4Cl exposure does not alter axonal morphology in mature aggregates

We have shown that ammonium impaired axons in developing aggregates but did not affect them in mature cultures. The absence of an NH4Cl effect on mature axons could be attributable to fully differentiated astrocytes, which have a higher capacity for ammonium detoxification (Butterworth, 1993). Alternatively, protective factors released by target postsynaptic neurons to their presynaptic counterparts could be involved (Keith and Wilson, 2001). This difference in vulnerability of the brain is also found clinically, because hyperammonemia causes irreversible CNS symptoms compatible with axonal loss in neonates and infants but not in adults (Brusilow and Horwich, 2001). Evidence for direct coupling of the Cr/PCr/CK system to growth cone activity and axonal growth (Wang et al., 1998) and Cr and PCr age dependency of the CNS in the first weeks of postnatal life (Tsuji et al., 1995) also supports the difference we found between developing and mature aggregates. It suggests a higher CNS sensitivity to Cr variations in young children than in adulthood.

The brain cell aggregate culture system as a model to study CNS hyperammonemia

Axonal growth was altered in developing brain cell aggregates by 5 mm NH4Cl exposure. This concentration mimicked the in vivo extracellular ammonium level found in the brain of experimental hyperammonemic rats, which was measured as high as 5 mm (Swain et al., 1992). For human hyperammonemic patients, data are lacking on extracellular brain ammonium concentration. However, serum levels of ammonium leading to irreversible damage to the developing CNS can peak as high as 2 mm, usually after chronic hyperammonemia in the range of 200 μm (Butterworth, 1998; Bachmann, 2002). Brain cell aggregate cultures fulfilled the requirements that irreversible ammonium toxicity to CNS should be studied in models mimicking brain complexity (Butterworth, 1998; Braissant et al., 1999a,b) but devoid of confusing variables attributable to secondary effects of hyperammonemia found in animal studies (Bachmann, 1992). Our findings are in agreement with data showing that hyperammonemia stimulates brain glycolysis with release of lactate into CSF and causes ammonium detoxification through astrocytic glutamine synthesis, which can lead to gliosis and occurrence of Alzheimer's type II astrocytes (Butterworth, 1998). Moreover, GAP43, an exclusive marker of axonal growth cones in physiological conditions, was induced in the GFAP-positive border of NH4Cl-exposed aggregates, as in reactive astrocytes (Sensenbrenner et al., 1997).

Conclusions

We have shown that glial Cr can protect axonal growth under ammonium exposure. This work exemplifies the importance of neuron–glial interactions in the pathophysiology of hyperammonemia. Future work will aim at identifying those factors modified through glial Cr that support axonal growth and are impaired by hyperammonemia and at understanding changes in brain Cr metabolism and transport under ammonium exposure. This study also suggests that one should assess means for sustaining the CNS Cr level of hyperammonemic neonates and infants to prevent irreversible brain damage caused by impairment of axonogenesis.

O.B. and H.H. contributed equally to this work.

This work was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation Grant 31-63892.00. We thank Dr. Marianna Giarrè for critical reading of this manuscript.

Correspondence should be addressed to Olivier Braissant, Clinical Chemistry Laboratory, University Hospital, CH-1011 Lausanne, Switzerland. E-mail: Olivier.Braissant@chuv.hospvd.ch.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albrecht J. Roles of neuroactive amino acids in ammonium neurotoxicity. J Neurosci Res. 1998;51:133–138. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980115)51:2<133::AID-JNR1>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachmann C. Ornithine carbamoyl transferase deficiency: findings, models and problems. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1992;15:578–591. doi: 10.1007/BF01799616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachmann C. Mechanisms of hyperammonemia. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2002;40:653–662. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2002.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bachmann C (2003) Outcome and survival of patients with urea cycle disorders (UCD). Eur J Pediatr, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Braissant O, Gotoh T, Loup M, Mori M, Bachmann C. l-Arginine uptake, the citrulline-NO cycle and arginase II in the rat brain: an in situ hybridization study. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1999a;70:231–241. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braissant O, Honegger P, Loup M, Iwase K, Takiguchi M, Bachmann C. Hyperammonemia: regulation of argininosuccinate synthetase and argininosuccinate lyase genes in aggregating cell cultures of fetal rat brain. Neurosci Lett. 1999b;266:89–92. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00274-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braissant O, Henry H, Loup M, Eilers B, Bachmann C. Endogenous synthesis and transport of creatine in the rat brain: an in situ hybridization study. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2001;86:193–201. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00269-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown A. Contiguous phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated domains along axonal neurofilaments. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:455–467. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.4.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brusilow SW, Horwich AL. Urea cycles enzymes. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, editors. The metabolic and molecular bases of inherited disease. McGraw-Hill; New-York: 2001. pp. 1909–1963. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butterworth RF. Portal-systemic encephalopathy: a disorder of neuron-astrocytic metabolic trafficking. Dev Neurosci. 1993;15:313–319. doi: 10.1159/000111350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butterworth RF. Effects of hyperammonaemia on brain function. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1998;21 [Suppl 1]:6–20. doi: 10.1023/a:1005393104494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox G. Neuropathological techniques. In: Bandcroft JD, Stevens A, editors. Theory and practice of histological techniques. Churchill Livingstone; Edinburgh: 1977. pp. 249–273. [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Waegh SM, Lee VM, Brady ST. Local modulation of neurofilament phosphorylation, axonal caliber, and slow axonal transport by myelinating Schwann cells. Cell. 1992;68:451–463. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90183-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dolman CL, Clasen RA, Dorovini-Zis K. Severe cerebral damage in ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Clin Neuropathol. 1988;7:10–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Filloux F, Townsend JJ, Leonard C. Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency: neuropathologic changes acquired in utero. J Pediatr. 1986;108:942–945. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80935-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flint Beal M, Martin JB. Major complications of cirrhosis. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Isselbacher KJ, Wilson JD, Martin JB, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, editors. Harrison's principles of internal medicine. McGraw-Hill; New-York: 1998. pp. 2451–2457. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furuta A, Martin LJ, Lin CL, Dykes-Hoberg M, Rothstein JD. Cellular and synaptic localization of the neuronal glutamate transporters excitatory amino acid transporter 3 and 4. Neuroscience. 1997;81:1031–1042. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00252-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goslin K, Schreyer DJ, Skene JH, Banker G. Development of neuronal polarity: GAP-43 distinguishes axonal from dendritic growth cones. Nature. 1988;336:672–674. doi: 10.1038/336672a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harding BN, Leonard JV, Erdohazi M. Ornithine carbamoyl transferase deficiency: a neuropathological study. Eur J Pediatr. 1984;141:215–220. doi: 10.1007/BF00572763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris J, Ayyub C, Shaw G. A molecular dissection of the carboxyterminal tails of the major neurofilament subunits NF-M and NF-H. J Neurosci Res. 1991;30:47–62. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490300107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He Y, Janssen WG, Rothstein JD, Morrison JH. Differential synaptic localization of the glutamate transporter EAAC1 and glutamate receptor subunit GluR2 in the rat hippocampus. J Comp Neurol. 2000;418:255–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hemmer W, Wallimann T. Functional aspects of creatine kinase in brain. Dev Neurosci. 1993;15:249–260. doi: 10.1159/000111342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirokawa N, Takeda S. Gene targeting studies begin to reveal the function of neurofilament proteins. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1–4. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Honegger P, Monnet-Tschudi F. Aggregating neural cell culture. In: Fedoroff S, Richardson A, editors. Protocols for neural cell culture. Humana; Totowa, NJ: 2001. pp. 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Honegger P, Pardo B. Separate neuronal and glial Na+, K+-ATPase isoforms regulate glucose utilization in response to membrane depolarization and elevated extracellular potassium. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:1051–1059. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199909000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Honegger P, Lenoir D, Favrod P. Growth and differentiation of aggregating fetal brain cells in a serum-free defined medium. Nature. 1979;282:305–308. doi: 10.1038/282305a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Item CB, Stöckler-Ipsiroglu S, Stromberger C, Muhl A, Alessandri MG, Bianchi MC, Tosetti M, Fornai F, Cioni G. Arginine:glycine amidinotransferase deficiency: the third inborn error of creatine metabolism in humans. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:1127–1133. doi: 10.1086/323765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Julien JP. Neurofilament functions in health and disease. Cur Opinion Neurobiol. 1999;9:554–560. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4388(99)00004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keith CH, Wilson MT. Factors controlling axonal and dendritic arbors. Int Rev Cytol. 2001;205:77–147. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(01)05003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee VM, Carden MJ, Schlaepfer WW, Trojanowski JQ. Monoclonal antibodies distinguish several differentially phosphorylated states of the two largest rat neurofilament subunits (NF-H and NF-M) and demonstrate their existence in the normal nervous system of adult rats. J Neurosci. 1987;7:3474–3488. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-11-03474.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Msall M, Batshaw ML, Suss R, Brusilow SW, Mellits ED. Neurologic outcome in children with inborn errors of urea synthesis: outcome of urea-cycle enzymopathies. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:1500–1505. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198406073102304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neary JT, Norenberg LO, Gutierrez MP, Norenberg MD. Hyperammonemia causes altered protein phosphorylation in astrocytes. Brain Res. 1987;437:161–164. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91538-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nguyen MD, Lariviere RC, Julien JP. Deregulation of Cdk5 in a mouse model of ALS: toxicity alleviated by perikaryal neurofilament inclusions. Neuron. 2001;30:135–147. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00268-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pardo B, Honegger P. Selective neurodegeneration induced in rotation-mediated aggregate cell cultures by a transient switch to stationary culture conditions: a potential model to study ischemia-related pathogenic mechanisms. Brain Res. 1999;818:84–95. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01287-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phelps PE, Houser CR, Vaughn JE. Immunocytochemical localization of choline acetyltransferase within the rat neostriatum: a correlated light and electron microscopic study of cholinergic neurons and synapses. J Comp Neurol. 1985;238:286–307. doi: 10.1002/cne.902380305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Podolsky DK, Isselbacher KJ. Major complications of cirrhosis. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Isselbacher KJ, Wilson JD, Martin JB, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, editors. Harrison's principles of internal medicine. McGraw-Hill; New-York: 1998. pp. 1710–1717. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rao VL, Audet RM, Butterworth RF. Increased nitric oxide synthase activities and l-[3H]arginine uptake in brain following portacaval anastomosis. J Neurochem. 1995;65:677–678. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65020677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ratnakumari L, Qureshi IA, Butterworth RF. Effects of congenital hyperammonemia on the cerebral and hepatic levels of the intermediates of energy metabolism in spf mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;184:746–751. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)90653-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ratnakumari L, Qureshi IA, Butterworth RF. Evidence for cholinergic neuronal loss in brain in congenital ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Neurosci Lett. 1994;178:63–65. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90290-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenstein JM, Krum JM. Cytoskeletal protein immunoexpression in fetal neural grafts: distribution of phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated neurofilament protein and microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP-2). Cell Transpl. 1996;5:233–241. doi: 10.1177/096368979600500212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saez R, Llansola M, Felipo V. Chronic exposure to ammonium alters pathways modulating phosphorylation of microtubule-associated protein 2 in cerebellar neurons in culture. J Neurochem. 1999;73:2555–2562. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0732555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salomons GS, van Dooren SJ, Verhoeven NM, Cecil KM, Ball WS, Degrauw TJ, Jakobs C. X-linked creatine-transporter gene (SLC6A8) defect: a new creatine-deficiency syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:1497–1500. doi: 10.1086/320595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanchez C, Diaz-Nido J, Avila J. Phosphorylation of microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) and its relevance for the regulation of the neuronal cytoskeleton function. Prog Neurobiol. 2000;61:133–168. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schliess F, Gorg B, Fischer R, Desjardins P, Bidmon HJ, Herrmann A, Butterworth RF, Zilles K, Haussinger D. Ammonia induces MK-801-sensitive nitration and phosphorylation of protein tyrosine residues in rat astrocytes. FASEB J. 2002;16:224–248. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0862fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schulze A, Hess T, Wevers R, Mayatepek E, Bachert P, Marescau B, Knopp MV, De Deyn PP, Bremer HJ, Rating D. Creatine deficiency syndrome caused by guanidinoacetate methyltransferase deficiency: diagnostic tools for a new inborn error of metabolism. J Pediatr. 1997;131:626–631. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seidl R, Stöckler-Ipsiroglu S, Rolinski B, Kohlhauser C, Herkner KR, Lubec B, Lubec G. Energy metabolism in graded perinatal asphyxia of the rat. Life Sci. 2000;67:421–435. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00630-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sensenbrenner M, Lucas M, Deloulme JC. Expression of two neuronal markers, growth-associated protein 43 and neuron-specific enolase, in rat glial cells. J Mol Med. 1997;75:653–663. doi: 10.1007/s001090050149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shaw G, Osborn M, Weber K. Reactivity of a panel of neurofilament antibodies on phosphorylated and dephosphorylated neurofilaments. Eur J Cell Biol. 1986;42:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stöckler S, Holzbach U, Hanefeld F, Marquardt I, Helms G, Requart M, Hanicke W, Frahm J. Creatine deficiency in the brain: a new, treatable inborn error of metabolism. Pediatr Res. 1994;36:409–413. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199409000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Swain M, Butterworth RF, Blei AT. Ammonium and related amino acids in the pathogenesis of brain edema in acute ischemic liver failure in rats. Hepatology. 1992;15:449–453. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840150316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsuji M, Allred E, Jensen F, Holtzman D. Phosphocreatine and ATP regulation in the hypoxic developing rat brain. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1995;85:192–200. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(94)00213-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Uchino T, Endo F, Matsuda I. Neurodevelopmental outcome of long-term therapy of urea cycle disorders in Japan. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1998;21 [Suppl 1]:151–159. doi: 10.1023/a:1005374027693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ulfig N, Nickel J, Bohl J. Monoclonal antibodies SMI 311 and SMI 312 as tools to investigate the maturation of nerve cells and axonal patterns in human fetal brain. Cell Tissue Res. 1998;291:433–443. doi: 10.1007/s004410051013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wakamoto H, Manabe K, Kobayashi H, Hayashi M. Subclinical portal-systemic encephalopathy in a child with congenital absence of the portal vein. Brain Dev. 1999;21:425–428. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(99)00049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang YE, Esbensen P, Bentley D. Arginine kinase expression and localization in growth cone migration. J Neurosci. 1998;18:987–998. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-03-00987.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Witt A, Brady ST. Unwrapping new layers of complexity in axon/glial relationships. Glia. 2000;29:112–117. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(20000115)29:2<112::aid-glia3>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]