Abstract

The induction of synaptic plasticity is known to be influenced by the previous history of the synapse, a process termed metaplasticity. Here we demonstrate a novel metaplasticity in which group I metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR)-dependent long-term depression (LTD) of synaptic transmission is regulated by previous mGluR activation. In these studies, the group I mGluR-dependent LTD induced by the selective agonist (RS)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG-LTD) was inhibited by previous preconditioning brief high-frequency stimulation (HFS), regardless of whether the preconditioning HFS induced long-term potentiation. Blockade of NMDA receptors during the preconditioning HFS did not alter the inhibition of DHPG-LTD by the HFS. However, antagonism of mGluRs during the preconditioning HFS did prevent the inhibition of DHPG-LTD by the HFS. In addition, blocking PKC stimulation during the preconditioning HFS also prevented the inhibitory effect of HFS on DHPG-LTD. The DHPG-LTD itself was not inhibited by blocking PKC stimulation but was inhibited by blocking the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. Thus, whereas the DHPG-LTD is mediated via activation of the p38 MAPK pathway, the inhibitory effects of preconditioning HFS on DHPG-LTD are mediated via stimulation of group I/II mGluRs, activation of PKC, and subsequent blocking of the functioning of group I mGluR.

Keywords: long-term potentiation (LTP), long-term depression (LTD), metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR), p38 MAPK, PKC, metaplasticity, preconditioning

Long-term depression (LTD) of synaptic transmission can be induced by certain types of repetitive stimulation, especially prolonged low-frequency stimulation (LFS) (Dudek and Bear, 1992; Mulkey and Malenka, 1992; Abraham and Bear, 1996). Sustained depression of synaptic transmission can also be induced from the long-term potentiated (LTP) level, a phenomena often referred to as depotentiation (DP) (Barrionuevo et al., 1980; Fuji et al., 1991). The induction of LTD and DP is of two general forms, depending on the activation of either NMDA receptors (NMDARs) (Fuji et al., 1991; Dudek and Bear, 1992; Mulkey and Malenka, 1992; Holland and Wagner, 1998) or metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) (Bolshakov and Siegelbaum, 1994; O'Mara et al., 1995).

Group I mGluR-dependent LTD has been induced in the hippocampus by an increased level of synaptic stimulation (Oliet et al., 1997; Kemp and Bashir, 1999; Huber et al., 2000; Wu et al., 2001). However, such synaptically stimulated group I mGluR-dependent LTD has been difficult to induce reliably in the absence of blockade of NMDAR. An alternative method that has been used frequently to induce group I mGluR dependence is application of the selective group I mGluR agonist (RS)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG) (Palmer et al., 1997;Fitzjohn et al., 1998, 1999, 2001; Camodeca et al., 1999; Huber et al., 2000, 2001; Xiao et al., 2001). Little is known about the mechanisms of induction and the site of expression of DHPG-LTD. Thus, the intracellular signaling transduction mechanism mediating DHPG-LTD has not been identified, and the presynaptic versus the postsynaptic site of expression of the DHPG-LTD is debatable. Certain studies have presented evidence for a postsynaptic site of expression of DHPG-LTD, with DHPG-LTD in CA1 hippocampus involving a rapid postsynaptic protein synthesis (Huber et al., 2000), a long-lasting loss of postsynaptic AMPA receptors (Snyder et al., 2001; Xiao et al., 2001), and a reduction in miniature EPSC amplitude in CA1 (Xiao et al., 2001). In contrast, a presynaptic site of expression has been proposed on the basis that DHPG-LTD was associated with a change in paired-pulse facilitation and coefficient of variation in CA1 (Fitzjohn et al., 2001).

The induction of synaptic activity can be modulated by previous/preconditioning synaptic activity, with the term metaplasticity introduced to encompass such phenomena (Abraham and Bear, 1996). For example, the induction of LTP is inhibited by preconditioning weak high-frequency stimulation (HFS) (Huang et al., 1992). Moreover, the induction of NMDAR-dependent LTD is enhanced by previous HFS (Christie and Abraham, 1992; Wagner and Alger, 1995;Holland and Wagner, 1998). In the present study, we investigated metaplasticity pertaining to group I mGluR-dependent LTD at the medial perforant path to granule-cell synapse in the dentate gyrus of the rat hippocampal formation. We show that DHPG-LTD does not occur after HFS activation of mGluRs, and that although the DHPG-LTD is mediated via activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, the inhibition of DHPG-LTD is mediated via the stimulation of PKC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All experiments were performed on transverse slices of the rat hippocampus (age 3–4 weeks; weight 40–80 gm) (Bioresources Unit, Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland). Animal use was approved by the Bioresources Committee, Trinity College. The brains were rapidly removed after decapitation and placed in a cold oxygenated (95% O2 and 5% CO2) medium. Slices were cut at a thickness of 350 μm using a Campden Vibroslice (Campden Instruments, Loughborough, UK) and placed in a storage container containing an oxygenated medium at room temperature (20–22°C). The slices were then transferred as required to a recording chamber for submerged slices and continuously superfused at a rate of 6–7 ml/min at 30–32°C. The control medium contained (in mm): 120 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2P04, 26 NaHC03, 2.0 MgS04, 2.0 CaCl2, and 10 d-glucose. All solutions contained 50 μm picrotoxin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to block GABAA-mediated activity.

Standard electrophysiological techniques were used to record field potentials. Presynaptic stimulation was applied to the medial perforant pathway of the dentate gyrus, and field EPSPs were recorded at a control test frequency of 0.0167 Hz from the middle third of the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus. The inner (suprapyramidal) blade of the dentate gyrus was used in all studies. In each experiment, an input–output curve (afferent stimulus intensity vs EPSP amplitude) was plotted at the test frequency. For all experiments, the amplitude of the test EPSP was adjusted to one-third of maximum, usually ∼1–1.2 mV. The baseline was considered to be stable if no change in the EPSP occurred for 30 min before application of DHPG. LTP was evoked by HFS consisting of eight trains, each of eight stimuli at 200 Hz, with an intertrain interval of 2 sec; the stimulation voltage was increased during the HFS amplitude so as to elicit an EPSP of double the normal test EPSP amplitude. The drugs used wered(−)-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (d-AP-5) (Sigma), 2S-2amino-2-(1S,2S-2-carboxycyclopropyl-1-yl)-3-(xanth-9-yl)propanoic acid (LY341495) (Tocris Cookson, Bristol, UK), bisindolylmaleimide I (Bis-I) (Sigma), and 4-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-(4-methylsulfonylphenyl)-5-(4-pyridyl) imidazol (SB203580) (Calbiochem, Lucerne, Switzerland). Recordings were analyzed using pClamp (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). Values are the means ± SEM for n slices. The two-tailed Student's t test was used for statistical comparison.

RESULTS

Preconditioning HFS inhibits DHPG-LTD

Group I mGluR-dependent LTD of field EPSPs was induced by the application of DHPG, which is a selective agonist at group I mGluRs (Ito et al., 1992), with the EC50 value of the most active isomer, (S)-DHPG, being 11 μm (Baker et al., 1995). DHPG has been shown previously to induce LTD at the medial perforant path to the granule-cell synapse (Camodeca et al., 1999) in a manner similar to that found in CA1 (Palmer et al., 1997; Fitzjohn et al., 1999; Huber et al., 2000).

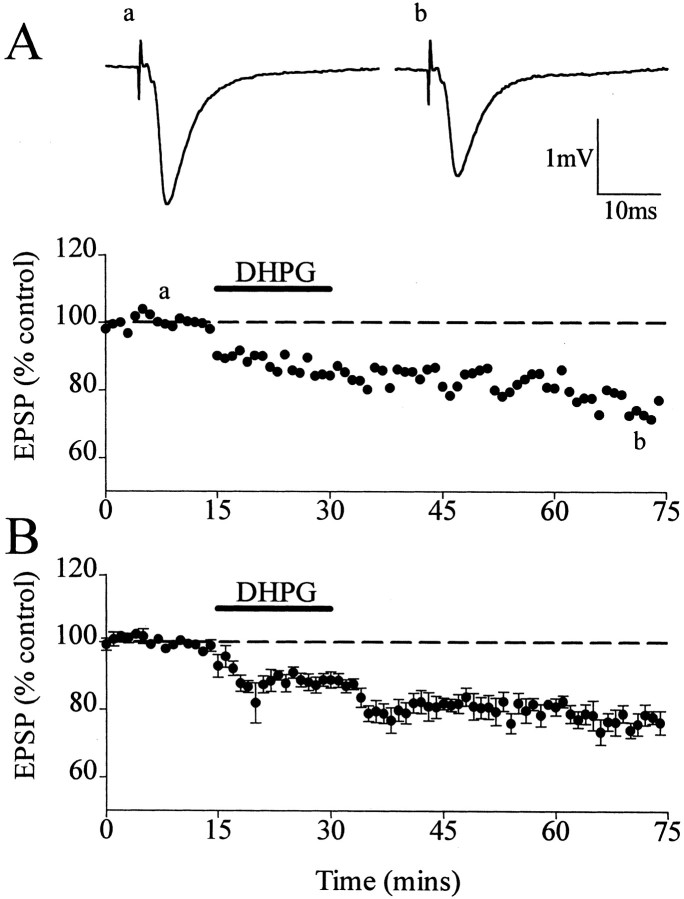

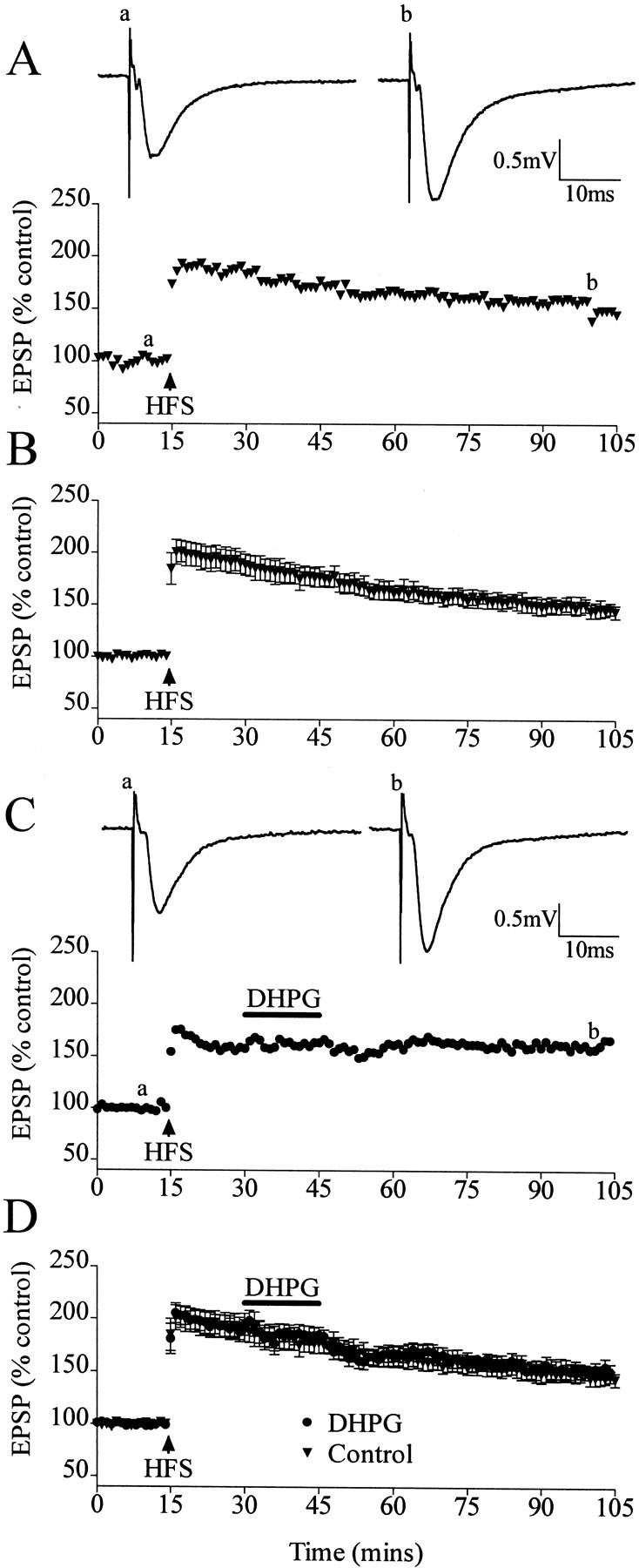

In control experiments, perfusion of DHPG (20 μm) for 15 min induced a depression of field EPSPs that persisted after the washout of DHPG-LTD. The DHPG-induced LTD measured 24 ± 3% (n = 7; p < 0.01) (Fig.1A,B), a value of LTD similar to that obtained in previous experiments (Camodeca et al., 1999). After HFS-induced LTP, DHPG failed to induce LTD from the LTP level when applied at 15 min after HFS. In controls, HFS-induced LTP attained a peak value of 201 ± 10% (n = 7) at 2 min after HFS and then declined very gradually, attaining a value of 148 ± 8% (n = 7) 90 min after stimulation (Fig.2A,B). Perfusion of DHPG 15 min after HFS for 15 min did not result in a significant difference from the control level of LTP, with EPSPs measuring 155 ± 6% (n = 5) in DHPG-treated specimens compared with 148 ± 8% (n = 7) in controls (p > 0.05) (Fig. 2C,D).

Fig. 1.

(S)-DHPG-induced LTD of field EPSPs in the medial perforant path–granule-cell synapse of the dentate gyrus. A, Single experiment showing that application of DHPG (20 μm) for 15 min induced a depression of the EPSPs that persisted after the washout of the DHPG.Traces are EPSPs before (a) and after (b) DHPG-LTD. B, Averaged data of the DHPG-LTD. Dashed lines show level of baseline.

Fig. 2.

DHPG does not induce LTD after HFS induction of LTP. A, Single experiment of induction of LTP by HFS.Traces are EPSPs before (a) and after (b) LTP induction. B, Averaged data of control LTP. C, Single experiment showing that application of DHPG does not induce LTD when applied 15 min after HFS-induced LTP. Traces are EPSPs before (a) and after (b) HFS and application of DHPG. D, Averaged data showing control LTP and with DHPG application.

Antagonism of NMDAR does not reverse the preconditioning HFS inhibition of DHPG-LTD

The initial experiments demonstrating that the preconditioning HFS inhibits the induction of LTD by DHPG suggest that the HFS is altering the signaling of a certain receptor. Because NMDARs are known to be activated by HFS, the involvement of such receptors in the inhibition of DHPG-LTD was investigated by applying the NMDAR antagonistd-AP-5 during the preconditioning HFS.

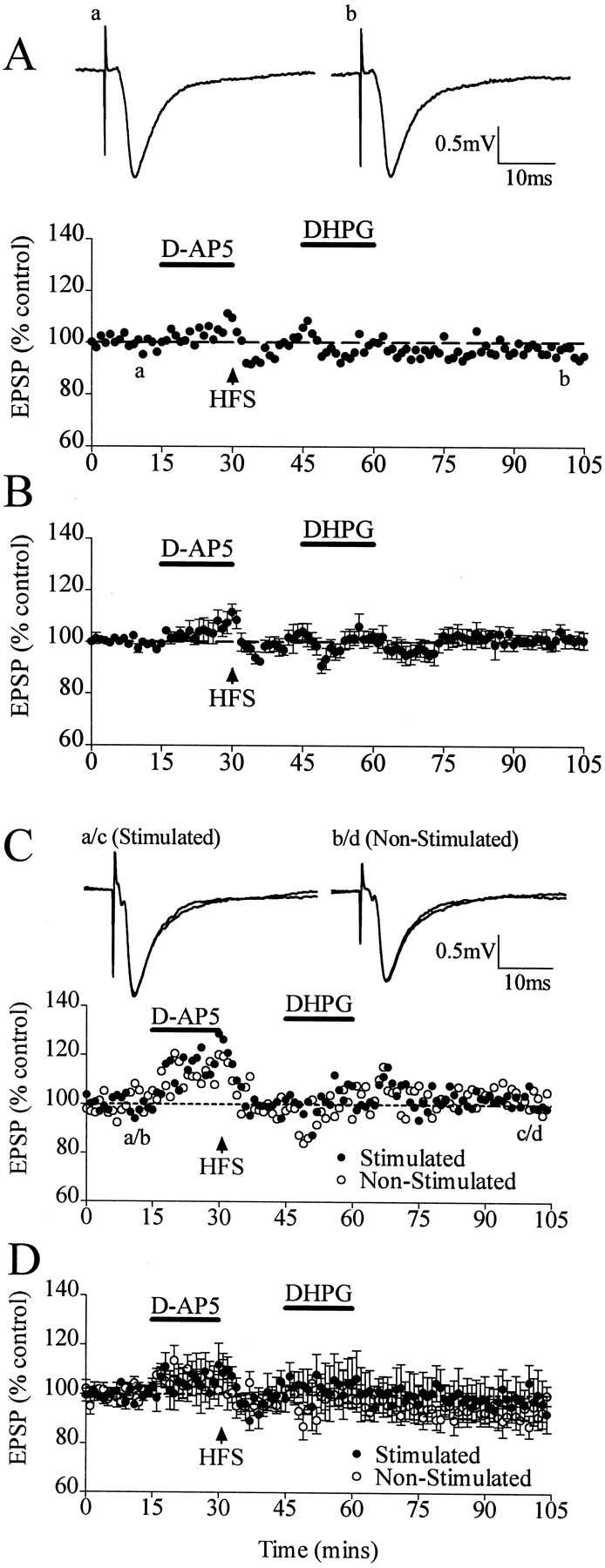

d-AP-5 (100 μm), applied before the HFS and then washed out immediately after it, inhibited the induction of LTP but did not reverse blocking of the DHPG-induced LTD. Thus, after HFS given in the presence of d-AP-5, there was no change in baseline (104 ± 3%; n = 6; p > 0.05). The application of DHPG did not induce LTD under such conditions (i.e., DHPG-LTD from the baseline did not occur after a preconditioning HFS in d-AP-5); the EPSP measured 101 ± 3% (n = 6; p > 0.05) 45 min after DHPG washout (Fig. 3A,B). The absence of DHPG-LTD in these experiments was not attributable to a block of the DHPG-LTD by incomplete washout of thed-AP-5, because DHPG-LTD was found to be independent of NMDAR activation in previous experiments at this synapse (Camodeca et al., 1999), a finding verified in the present study (data not shown). The inability of DHPG to induce LTD from the baseline after preconditioning HFS in the presence of d-AP-5 demonstrates that neither the activation of NMDAR nor the induction of LTP is required for the preconditioning inhibition of the DHPG-LTD.

Fig. 3.

DHPG does not induce LTD after HFS even under conditions in which HFS-induced LTP is blocked by the NMDAR antagonistd-AP-5 (100 μm) and the LTD block is heterosynaptic. A, Single experiment showing the blockade of DHPG-LTD by HFS in which the effect of DHPG was measured from baseline after HFS given in the presence ofd-AP-5. Traces show EPSPs before (a) and after (b) application of DHPG. B, Averaged experiments of HFS blockade of DHPG-LTD in d-AP-5. C, Single experiment showing block of DHPG-LTD by HFS in both the stimulated and nonstimulated pathways simultaneously in the same slice. Traces show EPSPs before (a/b) and after (c/d) application of DHPG. D, Averaged experiments of heterosynaptic HFS blockade of DHPG-LTD in d-AP-5. Dashed linesshow level of baseline.

The input specificity of the inhibition of DHPG-LTD was also investigated in the presence of d-AP-5. In these experiments, two independent pathways were monitored simultaneously in the hippocampal slice, with independence being verified by a lack of interaction between the electrodes in paired-pulse depression experiments. Figure 3C,D demonstrates evidence for a lack of input specificity, with the HFS applied to one pathway inhibiting DHPG-LTD in the heterosynaptic as well as the homosynaptic pathway. DHPG caused no reduction in EPSPs, measuring 97 ± 9% in the stimulated pathway and 93 ± 3% in the nonstimulated pathway (n = 5; p > 0.05).

Antagonism of mGluRs reverses the preconditioning HFS inhibition of DHPG-LTD

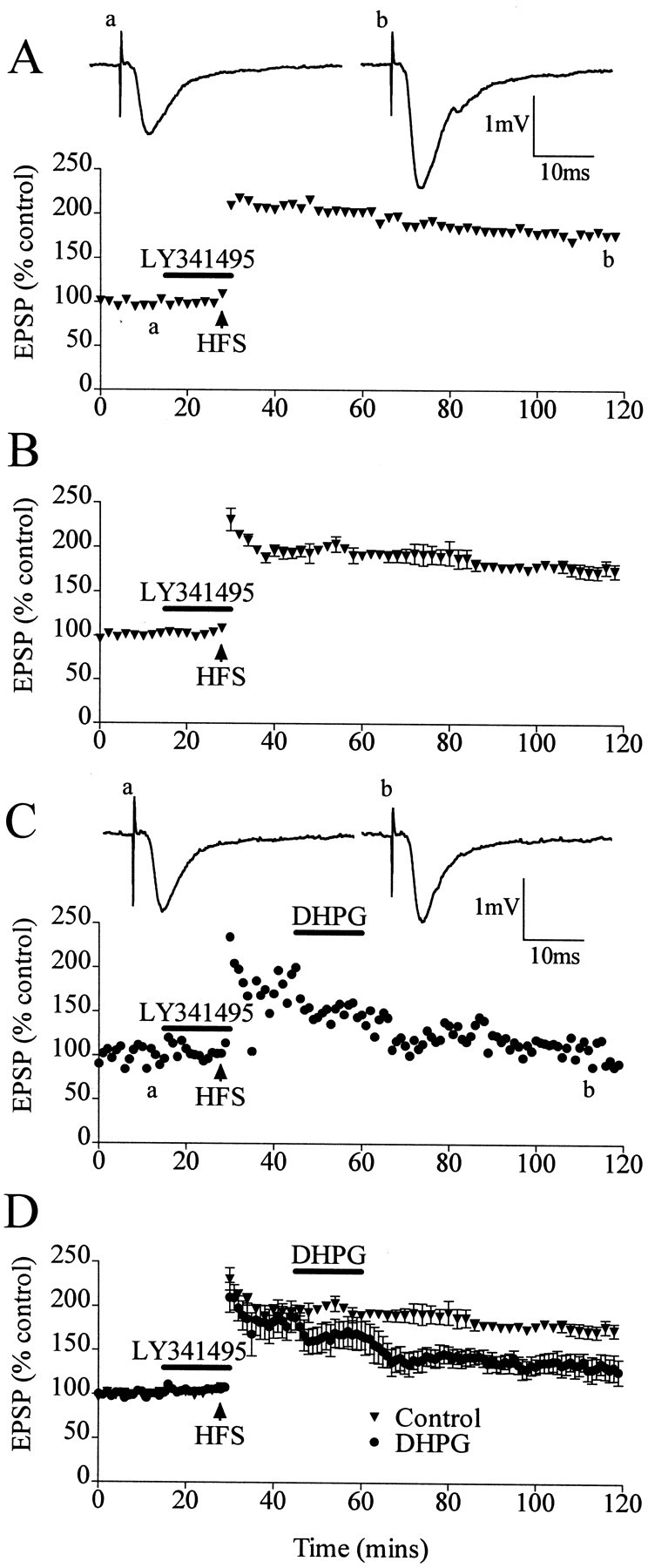

Because mGluRs are also likely to be activated during the preconditioning HFS, their involvement in the inhibition of DHPG-LTD was investigated by applying an mGluR antagonist during the preconditioning HFS. We used the mGluR antagonist LY341495, which is a potent antagonist of group I and group II mGluRs. LY341495 has been shown to inhibit group II mGluRs at low nanomolar concentrations and group I mGluRs at low micromolar concentrations (Fitzjohn et al., 1998;Kingston et al., 1998). LY341495 (20 μm) was found to reverse the preconditioning HFS blockade of DHPG-induced LTD. In control experiments in which LY341495 (20 μm) was applied before the HFS and washed out immediately after the HFS, and in which DHPG was not applied, the induction of LTP was not inhibited, measuring 179 ± 4% (n = 5) (Fig.4A,B). In experiments in which LY341495 (20 μm) was present during the preconditioning HFS and DHPG was applied 15 min after HFS, DHPG application did induce LTD from the LTP level; the DHPG-LTD measured 141 ± 9% (n = 5; p < 0.01) (Fig. 4C,D), an LTD of 23%.

Fig. 4.

DHPG-induced LTD from an LTP level is restored after HFS-induced LTP under conditions in which the HFS is applied in the presence of the mGluR antagonist LY341495 (20 μm).A, Single experiment showing that HFS-induced LTP is not inhibited if HFS is applied in the presence of LY341495.Traces show EPSPs before (a) and after (b) LTP induction. B, Averaged data on lack of inhibition of HFS-induced LTP in the presence of LY341495. C, Single experiment showing DHPG induction of LTD from the LTP level after the application of HFS in the presence of LY341495. Traces show EPSPs before LTP induction (a) and after the application of DHPG-LTD (b). D, Averaged data of restoration of DHPG-LTD after the application of HFS in the presence of LY341495.

These experiments demonstrate that the activation of mGluRs during the preconditioning HFS is involved in the inhibition of DHPG-induced LTD from the LTP level.

Antagonism of mGluR and NMDAR during the preconditioning HFS results in DHPG-LTD from baseline

To further determine whether DHPG-LTD could be induced from the baseline level when the activation of mGluRs was inhibited during the preconditioning HFS, experiments were performed in which both NMDARs and mGluRs were inhibited by the presence of d-AP-5 and LY341495 during the preconditioning HFS. In control experiments, HFS applied in the presence of d-AP-5 (100 μm) and LY341495 (20 μm) evoked a transient depression lasting 5–10 min, followed by a return to baseline (Fig.5A,B). In an additional set of experiments, DHPG was applied 15 min after the preconditioning HFS given in d-AP-5 and LY341495. DHPG-LTD was induced in such experiments, measuring 21 ± 2% (n = 6; p < 0.01) (Fig.5C,D).

Fig. 5.

DHPG-induced LTD from the baseline is restored after HFS applied in the presence of d-AP-5 and LY341495.A, Single experiment showing that HFS given in the presence of d-AP-5 and LY341495 resulted in only a transient short-term depression of 5–10 min duration. Thetraces show EPSPs before (a) and after (b) HFS. B, Averaged data of HFS applied in d-AP-5 and LY341495. C, Single experiment showing that DHPG-induced LTD from the baseline occurred after HFS applied in the presence of d-AP-5 and LY341495. Traces show EPSPs before (a) and after (b) DHPG application. D, Averaged data showing restoration of DHPG-LTD from the baseline level after application of HFS in the presence of d-AP-5 and LY341495. Dashed lineshows level of baseline.

These experiments demonstrate that the activation of mGluRs during the preconditioning HFS is involved in the inhibition of DHPG-stimulated and synaptically stimulated induction of LTD from the baseline level.

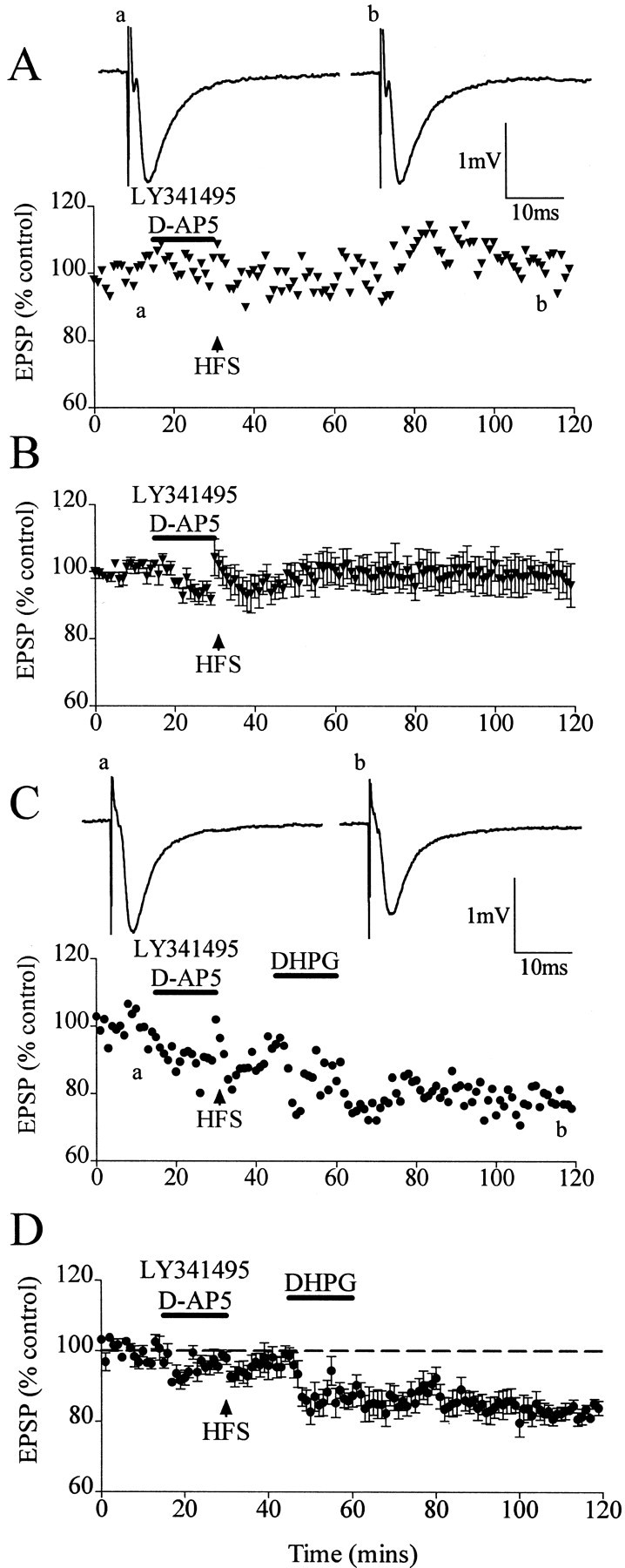

PKC mediates the preconditioning HFS inhibition of DHPG-LTD but not the DHPG-LTD

PKC is widely known to be stimulated after the activation of group I mGluRs (Conn and Pin, 1997). Therefore, we performed a set of experiments designed to investigate whether PKC stimulation mediated the DHPG-LTD and also whether the preconditioning HFS blockade of DHPG-LTD involved PKC stimulation by the preconditioning HFS.

PKC was inhibited with the potent and selective PKC inhibitor Bis-1. This compound has been shown previously to inhibit PKC in enzyme assays with a Ki of 10 nm and to inhibit other kinases only at much higher concentrations, for example, PKA with aKi of 2 mm(Nixon et al., 1992). Because Bis-1 acts competitively with respect to ATP (which is used at a lower concentration than that present in intact cells), Bis-1 was used at 2 μm in the present experiments. The experiments were performed in the presence ofd-AP-5 to prevent the induction of LTP.

We first determined whether DHPG-LTD was mediated via PKC stimulation. Bis-1 (2 μm) was preapplied for 1 hr before, during, and after DHPG application. DHPG-LTD was not inhibited by Bis-1 (2 μm), measuring 18 ± 4% (n = 4;p > 0.05) (Fig.6A,B).

Fig. 6.

Stimulation of PKC during HFS reverses the HFS inhibition of DHPG-LTD, although DHPG-induced LTD itself is not mediated via stimulation of PKC. A, Single experiment showing that the application of DHPG in the presence of the PKC inhibitor Bis-1 induced LTD. Traces show EPSPs before (a) and after (b) application of DHPG. B, Averaged data showing lack of inhibition of Bis-1 on DHPG-LTD. C, Single experiment showing that the application of HFS in the presence of Bis-1 andd-AP-5 restored the subsequent DHPG-LTD. Tracesare EPSPs before (a) and after (b) DHPG application. D, Averaged data of restoration of DHPG-LTD after HFS in Bis-1 andd-AP-5. Dashed lines show level of baseline.

We next determined the involvement of PKC stimulation in the preconditioning HFS inhibition of DHPG-LTD. Thus, Bis-1 was preperfused for at least 1 hr before the preconditioning HFS, followed by the addition of d-AP-5, and then washed out after the preconditioning HFS. DHPG was applied 15 min after the preconditioning HFS had been given in the presence of Bis-1 and d-AP-5. The inhibition of PKC stimulation by Bis-1 during the preconditioning HFS resulted in a reversal of the preconditioning HFS block of the DHPG-induced LTD; the DHPG-LTD measured 28 ± 4% (n = 7; p < 0.01) (Fig.6C,D).

These experiments show that although PKC stimulation is not involved in the induction of DHPG-LTD, the PKC stimulated by the preconditioning HFS does inhibit subsequent DHPG-LTD.

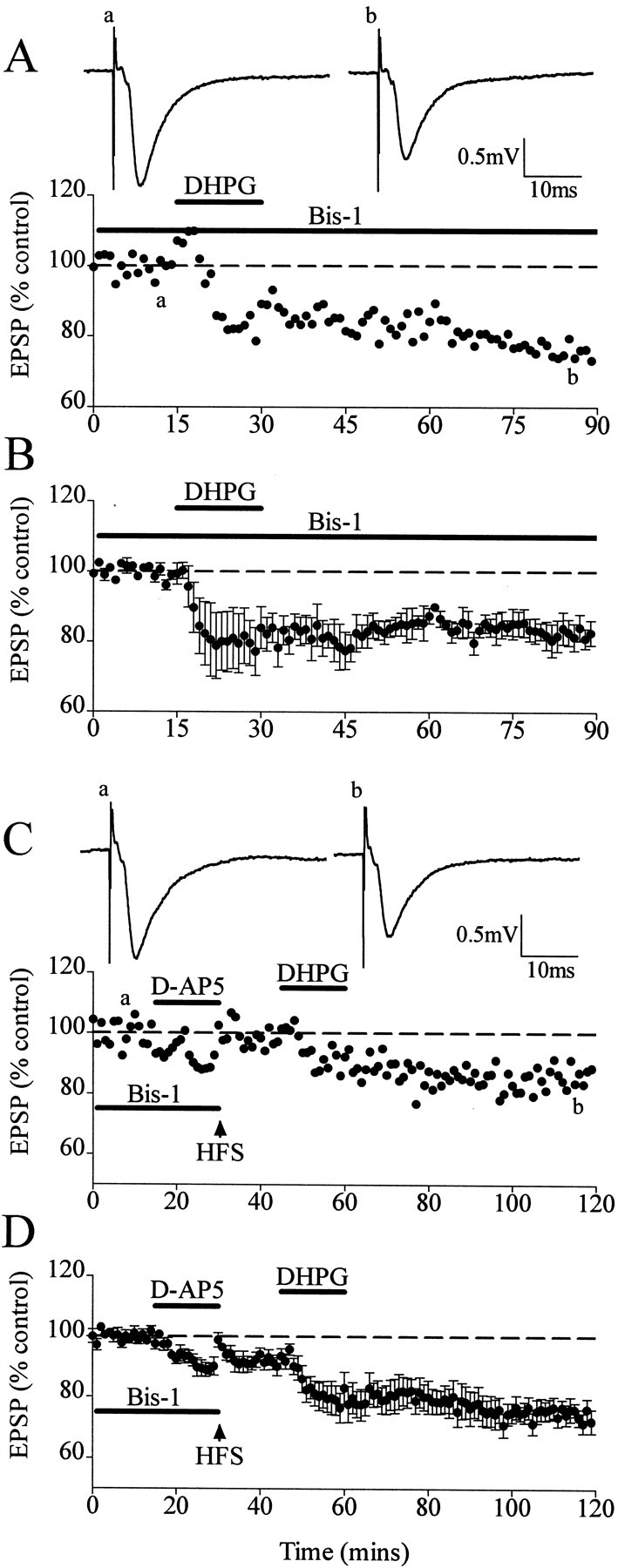

DHPG-LTD is dependent on activation of the p38 MAP kinase

We determined whether DHPG and synaptically induced LTD were dependent on activation of the p38 MAPK pathway with the use of the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580. SB203580 is a highly selective p38 MAPK inhibitor with an IC50 value of 34 nm(Lee et al., 1994).

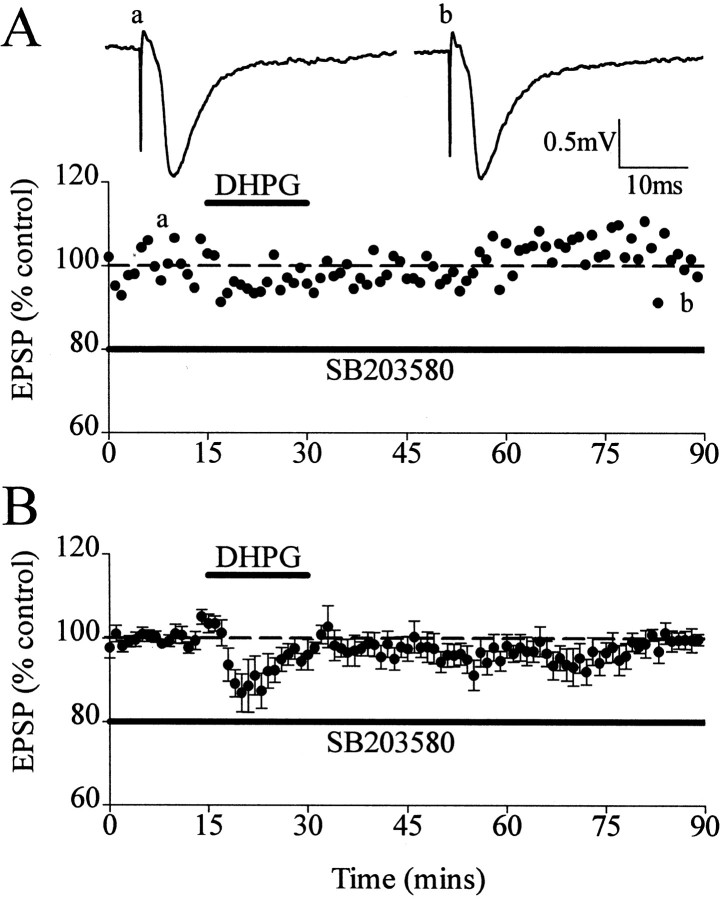

SB203580 (1 μm) was preperfused for at least 1 hr before the application of DHPG. No change in baseline was observed. However, SB203580 did prevent induction of LTD by DHPG. Thus, DHPG-LTD measured 100 ± 1% (n = 6; p > 0.05) in the presence of SB203580, demonstrating that p38 MAPK stimulation is required for DHPG-LTD (Fig.7A,B).

Fig. 7.

DHPG is mediated via the p38 MAPK pathway.A, Single experiment showing that DHPG does not induce LTD in the presence of the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580.Traces are EPSPs before (a) and after (b) application of DHPG. B, Averaged data of absence of DHPG-LTD in SB203580. Dashed lines show level of baseline.

DISCUSSION

In the present studies we have shown that the ability to induce DHPG-LTD is regulated by the previous activation of mGluRs. Evidence is presented that a preconditioning HFS prevents the subsequent induction of DHPG. The inhibition of the mGluR-dependent LTD by the preconditioning HFS involves stimulation of PKC via the activation of mGluRs. The most likely mechanism of such inhibition of LTD induction is a PKC-mediated inactivation of group I mGluRs via a classical feedback loop, with the activation of mGluRs by the preconditioning HFS resulting in stimulation of PKC and subsequent inactivation of the group I mGluRs. One possible way in which this could occur is by desensitization, because desensitization of group I mGluRs by mGluR-mediated stimulation of PKC is a well known phenomenon (Schoepp and Johnson, 1988; Guerineau et al., 1997; Gereau and Heinemann, 1998;Alagarsamy et al., 1999). Moreover, analysis of PKC phosphorylation site mutants has revealed several sites, including most effectively, serine/threonine 881 and 890, at which desensitization of mGluR5 occurs (Gereau and Heinemann, 1998).

A novel aspect of the present study was the ability to produce inactivation of group I mGluR functioning by a very brief physiological stimulation, preconditioning HFS. Previous studies of inactivation/desensitization of mGluRs have involved application of a glutamate agonist, often for prolonged periods of 30 min to several hours in neurochemical experiments, although agonist applications of 1–2 min have been shown recently to be effective at evoking a desensitization of group I mGluRs in physiological experiments (Guerineau et al., 1997; Gereau and Heinemann, 1998).

Evidence for involvement of mGluRs in the preconditioning inhibition of DHPG-LTD was attained using the mGluR antagonist LY341495. LY341495 is a potent group II mGluR antagonist at low nanomolar concentrations (Kingston et al., 1998), but it also inhibits group I mGluRs at low micromolar concentrations (Kingston et al., 1998). In slices, LY341495 inhibits DHPG-stimulated phosphatidylinositol (PI) hydrolysis with a Ki value of 1.4 μm and inhibits DHPG potentiation of NMDAR depolarizations with an IC50 of 1.4 μm (Fitzjohn et al., 1998). Thus, the concentration of LY341495 that was effective in the present study (20 μm) will have inhibited activation of both group I and group II mGluRs. Therefore, it is possible that coactivation of both group I and group II mGluRs is required for HFS inhibition of DHPG-LTD. In support of this theory, neurochemical studies have shown evidence for a strong synergistic interaction between group I and group II mGluRs in the stimulation of PI hydrolysis in the adult hippocampus, with DHPG alone only weakly stimulating PI hydrolysis but coapplication of DHPG with a group II mGluR agonist resulting in a very large stimulation of PI hydrolysis (Schoepp et al., 1996, 1998). Both group I and group II mGluRs are present at high concentrations at the medial perforant path–granule-cell synapses (Shigemoto et al., 1997). Detailed pharmacological identification of the mGluR receptor(s) responsible for the inhibition of DHPG-LTD was attempted but was unsuccessful because of difficulty in pharmacological selectivity and adequate washout of available antagonists. Overall, we favor the theory that the HFS preconditioning stimulation activates both group I and group II mGluRs, resulting in the strong stimulation of PKC and in the subsequent desensitization and inhibition of group I mGluRs.

The present study shows that the DHPG-LTD was mediated via activation of the p38 MAPK pathway. Although the signal transduction pathway underlying DHPG-LTD has not been identified previously, the induction of group I mGluR-LTD by presynaptic stimulation has been shown recently to be mediated via the p38 MAPK pathway in CA3–CA1 synapses (Bolshakov et al., 2000). The finding of an identical signal transduction pathway responsible for DHPG-LTD and presynaptically stimulated group I mGluR-LTD strengthens the similar underlying mechanisms of the LTD induced by these two methods. In agreement with the studies of Schnabel et al. (1999), we found that PKC stimulation was not involved in the mediation of DHPG-LTD. Rather, the role of the stimulated PKC was to exert control on a separate intracellular signaling pathway evoked by stimulation of the group I mGluR, that of p38 MAPK. Previous studies using neurochemical techniques have shown that metabotropic receptors can be linked to a variety of intracellular signaling pathways, and that activation of one pathway can alter stimulation of a separate pathway (Luttrell et al., 1999). However, the present study is a novel physiological demonstration of the interaction between intracellular signaling pathways.

This study emphasizes the importance of activation of mGluRs not only in directly mediating synaptic plasticity but also in modulating subsequent synaptic plasticity via a metaplastic function. The present study clearly demonstrates a type of metaplasticity in which activation of mGluRs modulates a subsequent synaptic plasticity that is dependent solely on mGluR activation (i.e., the preconditioning activation of mGluRs modulated an mGluR-dependent LTD). Previous studies have demonstrated that mGluRs can participate in a second form of metaplasticity in which preconditioning activation of mGluRs modulates subsequent NMDAR-dependent plasticity. Thus, activation of group I and II mGluRs by preconditioning HFS in the medial perforant path of the dentate gyrus resulted in a subsequent induction of NMDAR-dependent LTP by group II mGluR activation (Rush et al., 2001); agonist activation of mGluRs before HFS enhanced the amplitude of subsequent HFS-induced NMDAR-dependent LTP in CA1 (Cohen and Abraham, 1996), and in the amygdala; a preconditioning HFS operating via activation of group II mGluR altered the response to LFS from the induction of NMDAR-dependent LTP to LTD (Li et al., 1998).

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Health Research Board Ireland, Enterprise Ireland, and the Wellcome Trust Name.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. R. Anwyl, Department of Physiology, Trinity College, Dublin 2, Ireland. E-mail: ranwyl@tcd.ie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham WC, Bear MF. Metaplasticity: the plasticity of synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:126–130. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)80018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alagarsamy S, Marino MJ, Rouse ST, Gereau RW, Heinemann SF, Conn PJ. Activation of NMDAR reverses desensitisation of mGluR5 in naive and recombinant systems. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:234–240. doi: 10.1038/6338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker SR, Goldsworthy J, Harden RC, Salhoff CR, Schoepp DD. Enzymatic resolution and pharmacological activity of the enantiomers of 3,5-dihrdroxyphenylglycine, a metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist. Biorg Med Chem. 1995;5:223–228. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrionuevo G, Schottler F, Lynch G. The effects of repetitive low frequency stimulation on control and “potentiated” synaptic responses in the hippocampus. Life Sci. 1980;27:2385–2391. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(80)90509-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolshakov VY, Siegelbaum SA. Postsynaptic induction and presynaptic expression of hippocampal long-term depression. Science. 1994;264:1148–1152. doi: 10.1126/science.7909958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolshakov VY, Carboni L, Cobb MH, Siegelbaum SA, Belardetti F. Dual MAP kinase pathways mediate opposing forms of long-term plasticity at CA3–CA1 synapses. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1107–1112. doi: 10.1038/80624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camodeca N, Breakwell NA, Rowan MJ, Anwyl R. Induction of LTD by activation of group I mGluR in the dentate gyrus in vitro. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1597–1606. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christie BR, Abraham WC. Priming of associative long-term depression in the dentate gyrus by theta frequency synaptic activity. Neuron. 1992;9:79–84. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90222-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen AS, Abraham WC. Facilitation of long-term potentiation by prior activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:953–961. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.2.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conn PJ, Pin J-P. Pharmacology and functions of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;37:205–237. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dudek SM, Bear MF. Bi-directional long-term modification of synaptic effectiveness in the adult and immature hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1992;13:2910–2918. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-07-02910.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fitzjohn SM, Bortolotto ZA, Palmer MJ, Doherty AJ, Ornstein PL, Schoepp DD, Kingston AE, Lodge D, Collingridge GL. The potent mGluR receptor antagonist LY341495 identifies roles for both cloned and novel mGlu receptors in hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:1455–1458. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitzjohn SM, Kingston AE, Lodge D, Collingridge GL. DHPG-induced LTD in area CA1 of juvenile rat hippocampus: characterization and sensitivity to novel mGluR antagonists. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1577–1583. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00123-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzjohn SM, Palmer MJ, May JER, Neeson A, Morris SAC, Collingridge GL. A characterization of long-term depression induced by metabotropic glutamate receptor activation in the rat hippocampus in vitro. J Physiol (Lond) 2001;537:421–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00421.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuji S, Saito KH, Ito K, Kato H. Reversal of long-term potentiation (depotentiation) induced by titanic stimulation of the input to CA1 neurons of guinea pig hippocampal slices. Brain Res. 1991;555:112–122. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90867-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gereau RN, IV, Heinemann SF. Role of protein kinase C phosphorylation in rapid desensitisation of metabotropic glutamate receptor 5. Neuron. 1998;20:143–151. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80442-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guerineau NC, Bossu J-L, Gahwiler BH, Gerber U. G-protein-mediated desensitisation of metabotropic glutamatergic and muscarinic responses in CA3 cells in rat hippocampus. J Physiol (Lond) 1997;500:487–496. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp022035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holland LL, Wagner JJ. Primed facilitation of homosynaptic long-term depression and depotentiation in rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1998;18:887–894. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-03-00887.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang Y-Y, Colino A, Selig DK, Malenka RC. The influence of prior synaptic activity on the induction of long-term potentiation. Science. 1992;255:730–733. doi: 10.1126/science.1346729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huber KM, Kayser MS, Bear MF. Role for rapid dendritic protein synthesis in hippocampal mGluR-dependent long-term depression. Science. 2000;288:1254–1256. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5469.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huber KM, Roder JC, Bear MF. Chemical induction of mGluR5- and protein synthesis-dependent long-term depression in hippocampal area CA1. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:321–325. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.1.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ito I, Kohda A, Tanabe S, Hirose E, Hayashi N, Mitsunga S, Sugiyama H. 3,5-Dihydroxyphenylglycine: a potent agonist of metabotropic glutamate receptors. NeuroReport. 1992;3:1013–1016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kemp N, Bashir ZI. Induction of LTD in the adult hippocampus by the synaptic activation of AMPA/kainate and metabotropic receptors. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:495–504. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kingston AE, Ornstein PL, Wright RA, Johnson BG, Mayne NG, Burnett JP, Belagaje R, Wu S, Schoepp DD. LY341495 is a nanomolar potent and selective antagonist of group II metabotropic glutamate receptors. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00191-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JC, Laydon JT, McDonnell PC, Gallagher TF, Green D, McNulty D, Blumenthal MJ, Heys RJ, Landvatter SW, Stricker JE, McLaughlin MM, Siemens I, Fisher S, Livi GP, White JR, Adams JL, Young PR. Identification and characterization of a novel protein kinase involved in the regulation of inflammatory cytokine biosynthesis. Nature. 1994;372:739–746. doi: 10.1038/372739a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H, Weiss SRB, Chuang D-M, Post RM, Rogawski MA. Bidirectional synaptic plasticity in the rat basolateral amygdala: characterization of an activity-dependent switch sensitive to the presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonist 2S-α-ethylglutamic acid. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1662–1670. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-05-01662.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luttrell LM, Ferguson SS, Daaka Y, Miller WE, Maudsley S, Della Rocca GJ, Kawakatsu H, Owada K, Luttrell DK, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. β-arrestin-dependent formation of β2 adrenergic receptor-Src protein kinase complexes. Science. 1999;283:655–661. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5402.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mulkey RM, Malenka RC. Mechanisms underlying induction of homosynaptic long-term depression in area CA1 of the hippocampus. Neuron. 1992;9:967–975. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90248-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nixon JS, Bishop J, Bradshaw D, Davis PD, Hill CH, Elliot JH, Kumar H, Lawton G, Lewis EJ, Mulqueen M, Westmacott D, Wadsworth J, Wilkinson SE. The design and biological properties of potent and selective inhibitors of protein kinase C. Biochem Soc Trans. 1992;20:419–425. doi: 10.1042/bst0200419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oliet SHR, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. Two distinct forms of long-term depression co-exist in CA1 hippocampal pyramidal cells. Neuron. 1997;18:969–982. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Mara SM, Rowan MJ, Anwyl R. Metabotropic glutamate receptor induced long-term depression and potentiation in the dentate gyrus of the rat hippocampus in vitro. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:983–989. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00062-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palmer MJ, Irving AJ, Seabrook GR, Jane DE, Collingridge GL. The group I mGluR receptor agonist DHPG induces a novel form of LTD in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:1517–1532. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00181-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rush AM, Wu J, Rowan MJ, Anwyl R. Activation of group II metabotropic glutamate receptors results in long-term potentiation following preconditioning stimulation in the dentate gyrus. Neuroscience. 2001;105:335–341. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00191-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schnabel R, Kilpatrick IC, Collingridge GL. An investigation into signal transduction mechanisms involved in DHPG-induced LTD in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1585–1596. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schoepp DD, Johnson BG. Selective inhibition of excitatory amino acid-stimulated phosphoinositide hydrolysis in the rat hippocampus by activation of protein kinase C. Biochem Pharmacol. 1988;37:4299–4305. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90610-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schoepp DD, Salhoff CR, Wright RA, Johnson BG, Burnett JP, Mayne NG, Belagje R, Wu S, Monn JA. The novel metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist 2R,4R-APDC potentiates stimulation of phosphoinositide hydrolysis in the rat hippocampus by 3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine: evidence for a synergistic interaction between group 1 and group 2 receptors. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:1661–1672. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(96)00121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schoepp DD, Johnson BG, Wright RA, Salhoff CR, Monn JA. Potent, stereoselective and brain region selective modulation of second messengers in the rat brain by (+)LY354740, a novel group II metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1998;358:175–180. doi: 10.1007/pl00005240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shigemoto R, Kinoshita A, Wada E, Nomura S, Ohishi H, Takada M, Flor PJ, Neki A, Abe T, Nakanishi S, Mizuno N. Differential presynaptic localization of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtypes in the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7503–7522. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-19-07503.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Snyder EM, Philpot BD, Huber KM, Dong X, Fallon JR, Bear MF. Internalization of ionotropic glutamate receptors in response to mGluR activation. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1079–1085. doi: 10.1038/nn746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wagner JJ, Alger BE. GABAergic and developmental influences on homosynaptic LTD and depotentiation in rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1995;15:1577–1586. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-02-01577.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu J, Rush AM, Rowan MJ, Anwyl R. NMDA receptor- and metabotropic receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity induced by high frequency stimulation in the rat dentate gyrus in vitro. J Physiol (Lond) 2001;533:745–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00745.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiao M-Y, Zhou Q, Nicoll RA. Metabotropic glutamate receptor activation causes a rapid redistribution of AMPA receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2001;41:664–671. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]