Abstract

Dopamine receptor subtypes have been classified generally as D1-like (e.g., D1, D5) or D2-like (D2, D3, D4), and converging evidence suggests that D2-like receptors may be especially important in mediating the abuse-related effects of cocaine. However, it has been difficult to differentiate the roles of the D2-like receptor subtypes in the behavioral effects of cocaine because of the relatively low selectivity of drugs for D2, D3, and D4 receptors in vivo. The goal of the present series of studies was to investigate the contributions of D2-like receptor subtypes in the reinforcing effects of cocaine using new genetic and pharmacological tools. First, we evaluated cocaine self-administration behavior, and related effects of nonselective D2-like drugs, in mutant mice that lack the D2 receptor but express D3 and D4 receptors. When high doses of cocaine on the descending limb of the cocaine dose–effect function were available, D2 mutant mice self-administered at higher rates than their heterozygous or wild-type littermates, but the ascending limb of the cocaine dose–effect function did not differ between genotypes. Elevated rates of drug intake were not attributable to nonspecific increases in response rate, because response rates maintained by presentation of a range of food concentrations were significantly lower in D2 mutant mice than in wild-type mice. In wild-type mice, pretreatment with the D2-like antagonist eticlopride increased rates of self-administration of high doses of cocaine, and the D2-like agonist quinelorane served as a positive reinforcer when substituted for cocaine. However, these effects of eticlopride and quinelorane were not observed in mice that lacked the D2 receptor. Next, we compared the effects of novel antagonists selective for different D2 receptor subtypes on cocaine self-administration behavior in outbred rats. In rats, a D2 selective antagonist increased rates of self-administration of high doses of cocaine and also combinations of cocaine and the D2-like agonist quinelorane, whereas D3/D4 antagonists were ineffective. Collectively, these findings suggest that the D2 receptor is not necessary for cocaine self-administration, but this receptor subtype is involved in mechanisms that limit rates of high-dose cocaine self-administration. Our results also suggest that D3 and D4 receptors do not play major roles in the modulation of cocaine self-administration by D2-like drugs.

Keywords: dopamine, cocaine, D2, D3, D4, receptor

Cocaine abuse and dependence remain serious public health problems for which there are no uniformly effective treatment medications (Mendelson and Mello, 1996; NIDA, 1999). Much evidence suggests that the reinforcing effects of cocaine are related to blockade of the dopamine transporter and consequent increases in the binding of dopamine to postsynaptic dopamine receptors. For example, destruction of dopamine nerve terminals can lead to extinction of cocaine self-administration behavior (Roberts et al., 1977, 1980), and these effects have been observed even when responding maintained by other reinforcers was preserved (Pettit et al., 1984; Caine and Koob, 1994a). Moreover, dopamine reuptake inhibitors other than cocaine also serve as positive reinforcers, and the relative potency of those compounds in maintaining self-administration behavior generally correlates with their potency in binding to the dopamine transporter (Ritz et al., 1987; Bergman et al., 1989). In addition, direct dopamine receptor agonists maintain self-administration behavior when substituted for cocaine (Baxter et al., 1974; Gill et al., 1978; Yokel and Wise, 1978; Woolverton et al., 1984), and conversely, dopamine receptor antagonists attenuate the behavioral effects of self-administered cocaine (Wilson and Schuster, 1972; deWit and Wise, 1977; De La Garza and Johanson, 1982). Thus, several lines of evidence suggest a prominent role for dopamine receptors in cocaine self-administration behavior.

At least five genes encoding dopamine receptor subtypes have been identified, and their protein products have been classified as “D1-like” (D1, D5) or “D2-like” (D2, D3, D4) based on their pharmacological profiles (Schwartz et al., 1992; Sibley et al., 1993). In general, both D1-like and D2-like agonists served as positive reinforcers (Yokel and Wise, 1978; Woolverton et al., 1984; Self and Stein, 1992; Weed and Woolverton, 1995), and both D1-like and D2-like receptor antagonists attenuated the behavioral effects of self-administered cocaine (Koob et al., 1987; Bergman et al., 1990;Caine and Koob 1994b; for review, see Mello and Negus, 1996). However, under some conditions, D2-like agonists, but not D1-like agonists, produced cocaine-like behavioral effects in animals trained to discriminate cocaine or to self-administer cocaine (Grech et al., 1996;Self et al., 1996; Caine et al., 1999a, 2000a,b). These latter findings suggest that D2-like receptors may be especially important for the abuse-related effects of cocaine. Whether cocaine-like effects of D2-like agonists are attributable to actions of the drugs at the D2, D3, or D4 receptor subtype has been investigated extensively (Caine and Koob, 1993, 1995; Nader and Mach, 1996; Lamas et al., 1996; Spealman, 1996; Caine et al., 1997; Sinnott et al., 1999). Unfortunately, the drugs used in those studies may not bind selectively to a single D2-like receptor subtype in vivo (Burris et al., 1995). As a result, the roles of D2, D3, and D4 receptors in the behavioral effects of cocaine remain unclear.

The goal of the present study was to investigate the roles of the D2-like receptor subtypes in the reinforcing effects of cocaine using new genetic and pharmacological tools. In one series of studies, we used mutant mice that lack the D2 receptor but express D3 and D4 receptors. Complete dose–effect functions for cocaine self-administration were determined to compare the potency and efficacy of cocaine as a reinforcer in mutant and wild-type mice. We also evaluated cocaine-like and cocaine-antagonist effects of a nonselective D2-like agonist and antagonist, respectively, to determine if these effects of D2-like drugs may be mediated through D3 and D4 receptors in the absence of the D2 receptor. In a second series of studies, we used novel antagonists selective for different D2-like receptor subtypes to address these same questions in intact rats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and housing conditions

Mice. For studies designed to establish the behaviorally active dose range of eticlopride in normal mice during cocaine self-administration, C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). For studies with mutant mice, dopamine D2 receptor deficient mice were generated using homologous recombination as previously described (Baik et al., 1995). Briefly, a 0.9 kb Ncol fragment containing exon 2 and flanking intron sequences was removed from a D2 receptor gene cloned from a mouse 129 embryonic stem cell library. The removed fragment was replaced with a 1.4 kb segment of a phosphoglycerate kinase 1-driving neomycin cassette that was inserted in the opposite transcriptional orientation relative to the D2 gene. Embryonic stem cells carrying the disrupted D2 allele were injected into C57BL/6 embryos at the blastocyst stage. Chimeric offspring were mated with C57BL/6 mice, and germline transmission of the mutant allele was assessed by Southern blot analysis of tail DNA isolated from the agouti-coat progeny.

Homozygous mutant mice and their heterozygous and wild-type littermates were bred and genotyped at the Institut de Genetique et de Biologie Moleculaire et Cellulaire (Strasbourg, France). Young adult mice (F3 generation) were shipped to the McLean Hospital (Harvard Medical School, Belmont, MA), where all behavioral tests were conducted. All female mice were shipped together and evaluated in behavioral studies as a cohort. Male mice were sent in a second shipment and subsequently evaluated. Mice were group housed up to four mice per cage (8.8 × 12.1 × 6.4 inches). Water was available ad libitum in the home cage. Food (mouse diet 5015, PMI Feeds, Inc., St. Louis, MO) was available ad libitum except during the initial several days of operant training (see below). Each cage was fitted with a filter top through which HEPA-filtered air was introduced (40 changes per hour). The temperature was maintained at ∼70° F, and illumination was provided for 12 hr/d (beginning at 7:00 A.M.). Mice were tested during the light phase of the diurnal cycle.

Rats. Cocaine self-administration studies were conducted in male Sprague Dawley rats (Charles River, Wilmington, MA). The rats weighed ∼350 gm at the start of the study and were maintained in the range of 400–500 gm with once daily feedings of standard rat chow (rat diet 5012; PMI Feeds). Bacon-flavored biscuits (Bioserve, Frenchtown, NJ) were also provided once or twice weekly, primarily for enrichment purposes. Rats were housed individually in cages (8.8 × 12.1 × 8.8 inches) with air, temperature, and lighting conditions as described above for mice.

Animal health and welfare. Vivarium conditions were maintained in accordance with the guidelines provided by the National Institutes of Health Committee on Laboratory Animal Resources. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Animal experimentation adhered to the guidelines described in the Policy on the Use of Animals in Neuroscience Research for the Society for Neuroscience. The health of the rodents was evaluated by research technicians on a daily basis and was also periodically monitored by consulting veterinarians.

Behavioral test apparatus

Mice. Experimental chambers (6.3 × 5.5 × 5.0 inches) inside sound-attenuating cubicles were equipped with a house light, ventilator fan, drug infusion pump (5 rpm motor; 3 ml syringe) liquid swivel with counterbalance arm, and two manipulanda with cue lights that were located on either side of a liquid dipper. The manipulanda were holes (1.2 cm diameter) equipped with photocells (for nose poke activation). All equipment was obtained from MedAssociates (Georgia, VT) except for the liquid swivel and counterbalance assembly (Instech, King of Prussia, PA). Scheduling of experimental events and data collection were accomplished using a DOS-based microcomputer system equipped with programs written in MedAssociates MedState Notation.

Rats. Experimental chambers (11.5 × 9.5 × 8.3 inches) inside sound-attenuating cubicles were equipped with a house light, ventilator fan, drug infusion pump (3.3 rpm motor; 10 ml syringe), liquid swivel and counterbalance arm, three response levers with cue lights, and a receptacle for food pellet reinforcement. All equipment was obtained from MedAssociates except for the liquid swivels (Lomir Biomedical, Malone, NY). Apparatus for scheduling experimental events and data collection was similar to that described above for mice.

Surgical procedures

Mice. Mice were anesthetized with an isofluorane–oxygen vapor mixture and prepared with chronic indwelling intravenous catheters as previously described (Caine et al., 1993), with minor modifications (Emmett-Oglesby et al., 1993; Deroche et al., 1997). Briefly, a 6 cm length of SILASTIC tubing (0.3 mm inner diameter, 0.6 mm outer diameter) was fitted to a 22 gauge steel cannula that was bent at a right angle and then embedded in a cement disk with an underlying nylon mesh. The catheter tubing was inserted 1.2 cm into an external jugular vein (Barr et al., 1979) and anchored with suture. The remaining tubing ran subcutaneously to the cannula, which exited at the midscapular region. All incisions were sutured and coated with triple antibiotic ointment. Ticarcillin disodium (20 μl of 67 mg/ml in saline) was administered through the catheter immediately after surgery to forestall infection, and buprenorphine was administered (0.032 mg/kg, s.c.) as an analgesic agent. For the next 4 d, mice were allowed to recover from surgery, and ticarcillin disodium was administered as before but with 30 U/ml heparin in the solution. Thereafter, catheters were flushed with saline containing heparin only (30 U/ml).

The patency of intravenous catheters was evaluated periodically (approximately every 10 d) and whenever drug self-administration behavior appeared to deviate dramatically from that observed previously. Approximately 20 μl of a cocktail containing 15% Ketaset (ketamine, 100 mg/ml), 15% Versed (midazolam, 5 mg/ml), and 70% saline was infused through the catheter. If prominent signs of anesthesia were not apparent within 3 sec of infusion, the catheter was surgically removed, and a new catheter was implanted in the left jugular vein using the surgical procedures described above. Catheter evaluations were always performed at least 2 hr or more before or after a drug self-administration test session.

Rats. Surgical procedures for rats were similar to those described above for mice, with the following modifications. SILASTIC catheter tubing was cut to 13 cm in length and inserted 3.7 cm into the vein. For rats, the volume of ticarcillin solution administered was 0.1 ml. Evaluations of catheter patency were infrequent (i.e., only if drug self-administration behavior deviated from that observed previously) and were performed with intravenous injections of 0.1 ml of the Ketaset–Versed cocktail described above.

Operant training and testing procedures

Food maintained responding in mice. Mice were placed in the operant chambers for up to 3 hr/d, 5–7 d per week. Mice were first acclimated to the food that was subsequently used to reinforce operant responding. Mice were deprived of food for 20 hr, which resulted in a mean reduction in body weight of ∼5%. Mice were then placed in test chambers for 2 hr with the fan and house light activated and with a small cup containing 5 ml of vanilla-flavored Ensure (a nutritional supplement, hereafter referred to as “liquid food”; Abbott Laboratories, Columbus, OH). After the acclimation session, mice were given 3 gm each of mouse chow in their home cage. This procedure was repeated until a minimum of 1.5 ml of liquid food was consumed during a 2 hr acclimation session (typically within one or two sessions). Thereafter, mouse chow was available ad libitumin the home cage, and the small cup was removed from the test chamber.

During subsequent 2 hr sessions, liquid food was available under a fixed ratio (FR) 1 schedule of reinforcement. When one manipulandum was activated (the active manipulandum), the adjacent cue light was illuminated, the house light was extinguished, and the dipper containing 17 μl of liquid food was raised into the chamber for 30 sec. Responses on the inactive manipulandum and all responses while the dipper was raised were recorded but were without scheduled consequences. Each session was preceded by presentation of one reinforcer, together with the cue light, for 60 sec. The session was terminated after 100 reinforcers were delivered or after 2 hr, whichever occurred first.

Responding on the active manipulandum was reinforced with various concentrations of food or water in a series of three training phases that have been described previously (Caine et al., 1999b). First, nose pokes in the active manipulandum were reinforced under the FR 1 schedule with 100% liquid food for a minimum of five sessions and until responding met criteria for baseline (acquisition). The criteria for baseline were: (1) stable daily responding (within 20% across two consecutive sessions), (2) a minimum of 20 responses on the active manipulandum, and (3) at least 70% of responses on the active manipulandum. After these baseline criteria were met, responses on the active manipulandum resulted in the presentation of water rather than liquid food for three subsequent sessions (extinction). Finally, responding produced liquid food (100%) or water presentations on alternate days over the next six sessions (alternation). These three training phases were designed to establish nose poke behavior that was related to presentations of a positive reinforcer (i.e., sweetened liquid food but not water in mice that had mouse chow and water available ad libitum in the home cage).

After the training phases of acquisition, extinction, and alternation were completed, responding maintained by various concentrations of liquid food (water or 3, 10, 32, or 100% Ensure in water) was evaluated to assess general operant performance across a range of reinforcer magnitudes. Concentrations of liquid food were presented according to a Latin square design, and all concentrations were tested in each animal at least twice.

Drug self-administration in mice. After training and evaluation of food-maintained behavior was completed, animals were implanted with chronic indwelling jugular catheters. Cocaine self-administration sessions were conducted using the schedule parameters described above for food-maintained responding, with the following exceptions. Responding was maintained by intravenous infusions of cocaine (∼1.0 mg/kg per injection) delivered in 18 μl over two sec. A 28 sec postreinforcer time out period was selected to match the parameters used for food-maintained responding (30 sec presentation). Sessions were initiated with an infusion that filled the catheter volume and then delivered one unit-dose of cocaine that was available for self-administration. In our initial studies, sessions were typically 2 hr in length. However, to facilitate training and complete studies more expeditiously, sessions were lengthened to 3 hr. In addition, although mice typically regulate their drug intake during self-administration tests, and overdose is rare, during our initial studies three D2 homozygous mutant mice self-administered >40 mg/kg of cocaine within 1 hr and died (see Discussion). Therefore limits on drug intake were imposed. Thus, conditions were finalized so that sessions were up to 3 hr in length and were terminated if >30 mg · kg−1 · hr−1or a total of >50 mg/kg cocaine was infused.

Criteria for stable cocaine-maintained responding were identical to those for food-maintained responding. After these criteria were met, saline was substituted for cocaine for several sessions, and then responding maintained by various doses of cocaine (0.03–3.2 mg/kg per injection) or saline was evaluated, according to a Latin square design. In subsequent studies, the effects of pretreatment with the D2-like antagonist eticlopride on cocaine self-administration were evaluated in some mice. Eticlopride was administered intraperitoneally ∼10 min before cocaine self-administration sessions. In additional studies, responding maintained by the D2-like agonist quinelorane was evaluated using the same procedures as in the cocaine self-administration studies.

Food-maintained responding in rats. During preoperative training, responding on either of two levers was maintained by 45 mg food pellets (A/I rodent pellets; P. J. Noyes Co., Lancaster, NH) that were delivered to a food receptacle located between the two levers. A single white stimulus light located above each lever was used to indicate that responding had scheduled consequences. Training of food-maintained responding under a FR 1 schedule continued until rats earned 100 food pellets in a single 2 hr session. Rats were then implanted with an intravenous catheter for drug self-administration studies as described earlier under surgical procedures.

Drug self-administration in rats. One week after surgery, rats were placed in the experimental chambers for daily sessions of up to 3 hr. A cue light above a single lever on the rear wall of the chamber was illuminated, and responding on that lever was maintained by intravenous cocaine injections under a FR 1 timeout 20 sec schedule of reinforcement. For initial training, the unit dose of cocaine was ∼1.0 mg/kg per injection delivered in 56 μl over ∼3.2 sec. Sessions were initiated with an infusion that filled the catheter volume and then delivered one unit-dose of cocaine. In subsequent training sessions the response requirement was gradually increased to a FR 5. Each rat was trained until cocaine self-administration behavior stabilized, and stability was defined as three consecutive sessions during which there was <10% variation in the total number of cocaine reinforcers earned per session. In some rats, pretreatment tests were then conducted, and novel dopamine D2-like antagonists were administered intraperitoneally (1 ml/kg) immediately before the test session in a dose range of 0.1–10.0 mg/kg. Doses of pretreatment drugs were varied according to a Latin square within-subjects design, and each pretreatment test was separated by at least 48 hr and also by self-administration sessions during which behavior within baseline parameters was observed.

In other rats, after criteria for stable cocaine-maintained responding were met, a procedure for rapid assessment of responding maintained by different doses of cocaine was implemented (Caine et al., 1999a). These multiple component sessions consisted of three or four 20 min components separated by timeout periods of 2 min. Dose–effect functions were determined by increasing the volume of cocaine injections in successive components so that 0, 17, 56, or 178 μl injections were delivered in ∼0, 1, 3.2, and 10 sec, respectively. Drug solutions consisted of 0.56 mg/ml cocaine, 1.78 mg/ml cocaine, or 5.6 mg/ml cocaine, yielding unit doses of 0, 0.01, 0.032, 0.10, 0.32, and 1.0 mg total cocaine per injection (∼0.032–3.2 mg/kg per injection). During any one session, different doses of cocaine were always presented in an ascending order, and a single injection of the cocaine dose available during each component was administered noncontingently at the beginning of the component. Pretreatment testing began once drug self-administration behavior stabilized, and stability was defined as three consecutive multiple component sessions during which the dose that maintained peak responding remained stable within a half log-unit range. Pretreatments with the novel dopamine D2-like antagonists were administered intraperitoneally (1 ml/kg) immediately before the test session in a dose range of 0.1–10.0 mg/kg. For each rat, a dose of 5.6 mg/kg of the pretreatment drug was tested at least twice with overlapping cocaine dose ranges. Additional studies were designed to clarify the contributions of the different D2-like receptor subtypes in the effects of D2-like agonists on cocaine self-administration (Caine and Koob, 1993). Quinelorane was dissolved in the cocaine solution to deliver injections that included a combination of cocaine (1.0 mg/kg per injection) and quinelorane (1.0 μg/kg per injection). After responding maintained by cocaine–quinelorane injections stabilized (i.e., <10% variation in the total number of cocaine reinforcers earned across two consecutive test sessions), pretreatment studies were conducted with the dopamine D2-like antagonists (0.3–3.0 mg/kg), as described above for studies with cocaine alone.

Data analysis

Group comparisons. All food- and drug-maintained responding was expressed as the total number of reinforced responses per hour. For each subject, multiple determinations were averaged. Data were analyzed with ANOVA using genotype and gender as between-subjects factors and using repeated measures for food concentration or drug dose. Significant main effects were followed by pair-wise comparisons using Fisher's PLSD. The criterion for significance wasp < 0.05 for all analyses.

Drug pretreatment data. Effects of drug pretreatment were analyzed with ANOVA using repeated measures for pretreatment dose and cocaine dose. Significant main effects were followed by pairwise comparisons (Newman–Keuls) of each cocaine dose under baseline conditions with the same cocaine dose under each pretreatment condition. Criterion for significance was p < 0.05 for all analyses.

Pharmacokinetic and radioligand studies with l-741,626 and l-745,829

Pharmacokinetic studies. CNS penetration of novel compounds was evaluated as described previously forl-745,870 (Patel et al., 1997). Briefly, rats received various doses of the compound, and terminal blood samples were obtained at 0.5 and 1.0 hr after administration. The brain was removed shortly after the blood sample. Plasma was separated from blood by centrifugation, and concentrations of compounds in plasma and brain were determined by HPLC with UV detection. Concentrations were determined from standard curves that were generated by adding known concentrations of the compounds to plasma and brain samples.

Radioligand studies. Competition binding studies were performed as described previously with l-745,870 (Patel et al., 1997). Briefly, cells stably expressing the rat D2, D3, or D4 receptors were lysed and incubated in the presence of 0.2 nm [3H]spiperone and 50 μl of displacing drugs (at a final concentration range of 0.001–10.0 μm). Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 10.0 μmapomorphine. IC50 values were determined in three to four separate experiments, and Ki values were calculated using the equation of Cheng and Prusoff (1973).

Drugs

Cocaine was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). The D2-like antagonist eticlopride and the D2-like agonist quinelorane were obtained from Research Biochemicals (Natick, MA). The D2, D3/D4, and D4 selective antagonists l-741,626, l-745,829, andl-745,870 were synthesized at Merck, Sharp, and Dohme (Harlow, UK). Cocaine and quinelorane were dissolved in physiological saline. Eticlopride was dissolved in ethanol and diluted to 1% ethanol in saline. l-741,626, l-745,829, andl-745,870 were dissolved in ethanol and diluted to <6% ethanol (v/v) and <25% polyethylene glycol (v/v) in sterile water. All doses refer to the weights of the respective salts. Pretreatment doses labeled “zero” indicate administration of the vehicle (1.0 ml/0.1 kg for mice and 1.0 ml/kg for rats).

RESULTS

Food maintained behavior in wild-type and D2 deficient mutant mice

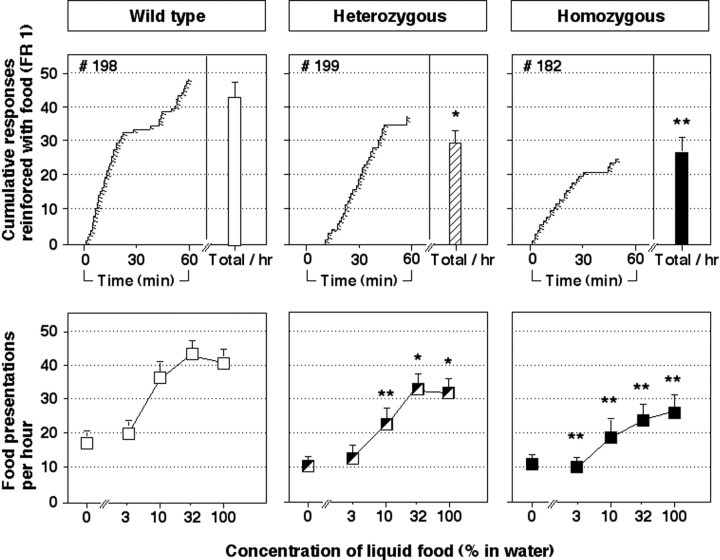

Figure 1 shows behavior maintained by liquid food in wild-type mice and D2 heterozygous and homozygous mutant mice after completion of the operant training procedure. Presentations of liquid food maintained nose poke behavior in all three groups of mice (Fig. 1, top panels). However, the number of food-reinforced nose pokes per hour was significantly lower in heterozygous (p < 0.05) and homozygous mutant mice (p < 0.01) than in wild-type mice (Fig. 1,top panels). Relative to behavior reinforced with food, nose pokes in the inactive manipulandum were low for all three groups of mice (mean levels of 10.5, 8.7, and 6.1 inactive nose pokes per hour in wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous mutant mice, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Behavior maintained by liquid food in wild-type mice (left panels, open symbols), heterozygous mutant mice (middle panels, hatched symbols), and homozygous mutant mice that lack the dopamine D2 receptor (right panels, filled symbols). The top panels show the number of food reinforcers delivered when 100% liquid food was available. The bar on the right side of each top panel shows the mean number of reinforcers per hour in each group of mice. The left side of each top panel shows a representative cumulative record for the first hour of a session from one mouse in each group. For cumulative records, the tracing moved to the right with the passage of time and incremented upward each time a response was emitted. Angled tick marks on the cumulative record indicate the delivery of a reinforcer (under an FR 1 schedule). Thebottom panels show the mean number of food reinforcers per hour as a function of the concentration of liquid food in water. Bars over symbols depict SEM. Asterisks indicate that the number of food reinforcers earned was significantly lower in mutant mice than in wild-type mice by pairwise comparisons following overall main effect by ANOVA (n = 14–17; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01).

When responding was reinforced with water or with various concentrations of food (3, 10, or 32% liquid food in water), rates of nose poke behavior was related to the concentration of the food reinforcer in all three groups of mice (Fig. 1, bottom panels). However, rates of nose poke behavior maintained by 10, 32, and 100% food were significantly lower in heterozygous mutant mice compared with wild-type mice (p < 0.01 or 0.05). Rates of nose poke behavior maintained by all concentrations of food were also significantly lower in homozygous mutant mice compared with wild type mice (p < 0.01).

Cocaine self-administration behavior in wild-type and D2-deficient mutant mice

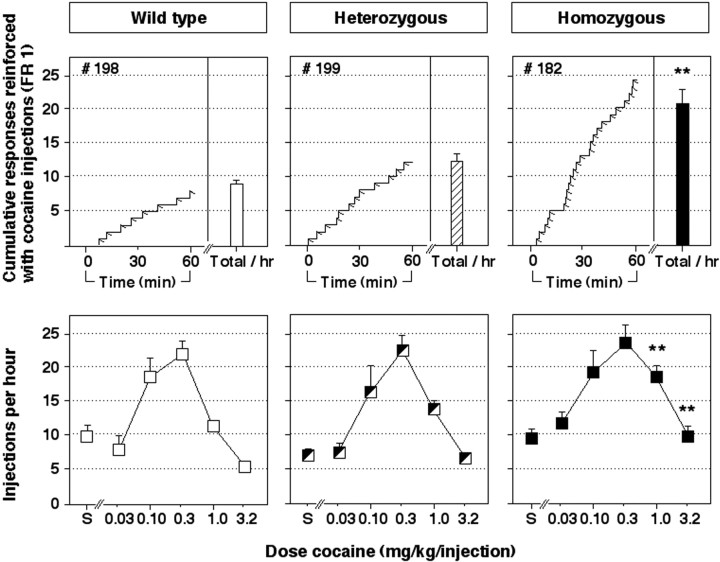

Figure 2 shows cocaine self-administration data in wild-type mice and D2 heterozygous and homozygous mutant mice. Cocaine injections (1.0 mg/kg per injection) maintained nose poke behavior in all three groups of mice, but response rates were significantly higher in homozygous mutant mice than in wild-type mice (Fig. 2, top panels) (p < 0.01). Nose pokes in the inactive manipulandum were infrequent for all three groups of mice (mean levels of 0.4, 1.8, and 1.0 inactive nose pokes per hour in wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous mutant mice, respectively).

Fig. 2.

Behavior maintained by intravenous cocaine injections in wild-type mice (left panels, open symbols), heterozygous mutant mice (middle panels, hatched symbols), and homozygous mutant mice that lack the dopamine D2 receptor (right panels, filled symbols). The top panels show the number of injections delivered when 1.0 mg/kg per injection of cocaine was available. The bar on the right side of each top panel shows the mean number of injections per hour in each group of mice. The left side of each top panel shows a representative cumulative response record for the first hour of a session from one mouse in each group. Bars over symbols depict SEM. In top left, center andright panels, respectively, mean data are shown from groups of 16, 17, and 14 mice after baseline criteria for cocaine self-administration were met. In bottom left, center,and right panels, respectively, mean data are shown from up to 13, 15, and 11 mice that were tested with various cocaine doses.Asterisks indicate that the number of cocaine injections earned was significantly higher in mutant mice than in wild-type mice by pairwise comparisons following overall main effect by ANOVA (analyzed within-subjects in groups of 6, 12, and 7 mice that were tested with every dose of cocaine; **p < 0.01).

When responding was reinforced with saline injections or with various unit doses of cocaine (0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 1.0, 3.2 mg/kg per injection), rates of nose poke behavior were related to the unit dose of cocaine by an inverted U-shaped dose–effect function in all three groups of mice (Fig. 2, bottom panels). However, as observed during initial baseline sessions (see above), rates of self-administration of 1.0 mg/kg per injection cocaine were significantly higher in homozygous mutant mice compared with wild-type mice (p < 0.01). Rates of self-administration in homozygous mutant mice were also higher than in wild-type littermates when 3.2 mg/kg per injection of cocaine reinforced nose poke behavior (p < 0.01). Thus, when high doses of cocaine were available for self-administration (1.0 and 3.2 mg/kg per injection), homozygous mutant mice self-administered cocaine at higher rates compared with their wild-type littermates. At lower unit doses of cocaine (0.032–0.32 mg/kg per injection), there were no significant differences in cocaine self-administration between the three groups. In heterozygous mutant mice, rates of self-administration of the two highest doses of cocaine were not significantly different from wild-type mice (p > 0.05), but values were generally intermediate between those observed in homozygous mutant mice and those observed in wild-type mice.

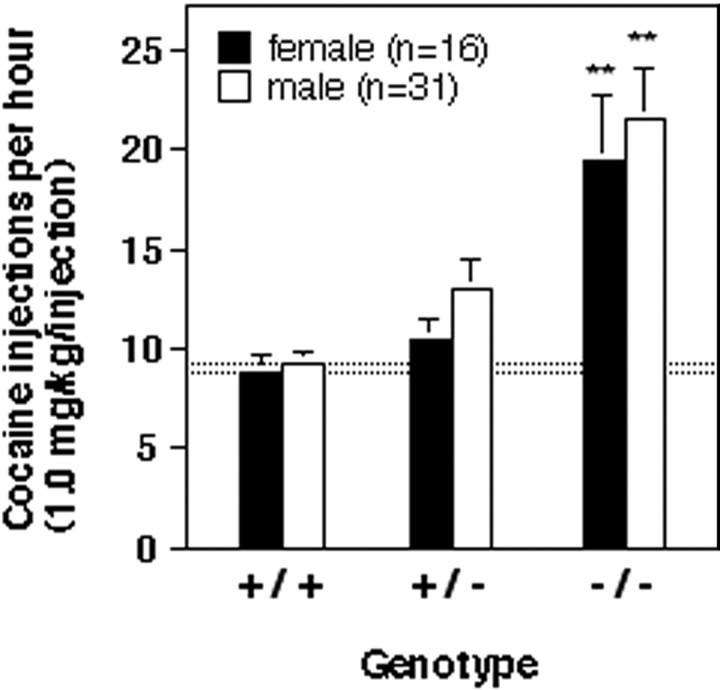

Figure 3 shows that behavior maintained by cocaine injections (1.0 mg/kg per injection) was comparable between female and male mice of each genotype, and no interactions between sex and genotype were observed (p > 0.05). There also were no sex–genotype interactions observed in food maintained responding or in the dose-related effects of cocaine as a reinforcer (p > 0.05; data not shown). Importantly, rates of self-administration of 1.0 mg/kg per injection cocaine were higher in homozygous mutant mice relative to wild-type mice regardless of sex (p < 0.01).

Fig. 3.

Behavior maintained by intravenous cocaine injections (1.0 mg/kg per injection) in wild-type mice (+/+), heterozygous (+/−) mice, and homozygous (−/−) mutant mice that lack the dopamine D2 receptor. Abscissa, Genotype. Ordinate, Mean number of cocaine injections earned per hour. Bars over symbols depict SEM. There were no statistically significant gender differences in cocaine self-administration baseline values.Asterisks indicate that the number of cocaine injections was significantly higher in mutant mice than in wild-type mice by pairwise comparisons following overall main effect by ANOVA (n = 5, 6, 5 for wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous female mice, respectively, and n = 11, 11, 9 for wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous male mice, respectively; **p < 0.01).

Effects of the D2-like antagonist eticlopride on cocaine self-administration behavior in C57BL/6 mice

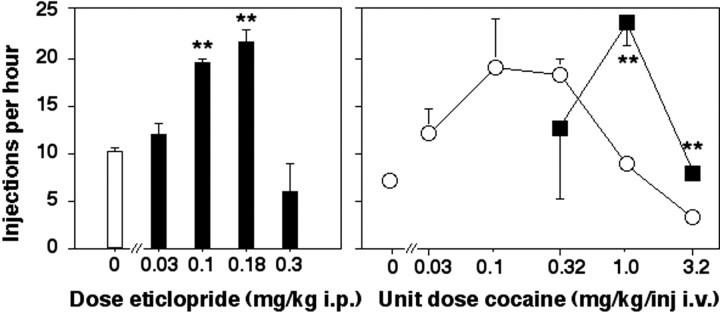

To establish appropriate doses of eticlopride for examining mechanisms underlying the reinforcing effects of cocaine in D2-deficient mutant mice and their wild-type littermates, the effects of eticlopride were examined in C57BL/6 mice. Pretreatment with eticlopride dose-dependently increased rates of self-administration of 1.0 mg/kg per injection of cocaine in C57BL/6 mice (Fig.4, left panel). Rates of cocaine self-administration were significantly increased by pretreatment with 0.1 and 0.18 mg/kg of eticlopride (p < 0.01). A higher dose of eticlopride (0.3 mg/kg) disrupted patterns of cocaine-maintained responding and produced long pauses in responding at various times throughout the test sessions, as well as high rates of cocaine-maintained responding at other times during the test sessions. In many instances, C57BL/6 mice were immobile after pretreatment with the highest dose of eticlopride (0.3 mg/kg), particularly during early portions of the test sessions.

Fig. 4.

Behavior maintained by intravenous cocaine injections in C57BL/6 mice after pretreatment with the D2-like antagonist eticlopride (filled symbols) or vehicle (open symbols). Abscissa, Pretreatment dose of eticlopride (left panel) or unit dose of cocaine per injection (right panel). In the left panel, the unit dose of cocaine was 1.0 mg/kg per injection. In the right panel, the pretreatment dose of eticlopride was 0.18 mg/kg, given intraperitoneally. Ordinate, Mean number of cocaine injections earned per hour. Bars over symbols depict SEM.Asterisks indicate that the number of cocaine injections earned was significantly higher after pretreatment with eticlopride by pairwise comparisons with vehicle pretreatment following overall main effect by ANOVA (n = 5-6; ∗∗p < 0.01).

When the self-administration of a range of unit doses of cocaine was examined, pretreatment with 0.18 mg/kg of eticlopride produced a rightward shift in the dose–effect function for cocaine self-administration in C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 4, right panel). Pretreatment with eticlopride (0.18 mg/kg) significantly increased rates of self-administration of 1.0 and 3.2 mg/kg/injection of cocaine (p < 0.01).

Effects of the D2-like antagonist eticlopride and the D2-like agonist quinelorane in wild-type and D2-deficient mutant mice

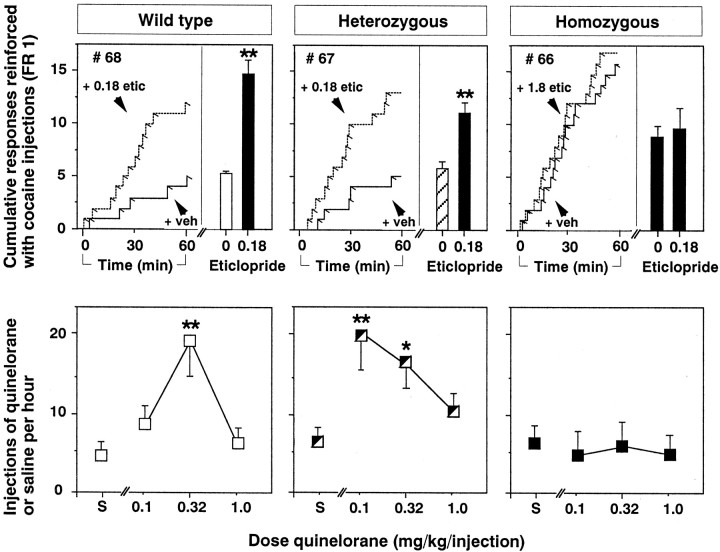

As in the C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 4), eticlopride (0.18 mg/kg) increased rates of self-administration of a high dose of cocaine (3.2 mg/kg/injection) in wild-type mice and in heterozygous D2-deficient mutant mice (Fig. 5, top leftand center panels) (p < 0.01). In contrast, this dose of eticlopride did not alter cocaine self-administration in mice that lacked the D2 receptor (Fig. 5,top right panel). In addition to tests with 0.18 mg/kg eticlopride (Fig. 5, histograms), several D2 receptor mutant mice were pretreated with a 10-fold higher dose of eticlopride before cocaine self-administration tests, and 1.8 mg/kg of eticlopride also did not alter cocaine self-administration in those mice (Fig. 5,top right panel, mouse #66).

Fig. 5.

Effects of the D2-like antagonist eticlopride on cocaine self-administration (top panels) and reinforcing effects of the D2-like agonist quinelorane (bottom panels), in wild-type mice (left panels), heterozygous mutant mice (middle panels), and homozygous mutant mice that lack the dopamine D2 receptor (right panels). Top panels, The bars on the right side of each top panel show the mean number of cocaine injections per hour after vehicle pretreatment or after pretreatment with 0.18 mg/kg eticlopride. The left sideof each top panel shows representative cumulative records for the first hour after vehicle (solid lines) or eticlopride pretreatment (hatched lines) from one mouse in each group. The pretreatment dose of eticlopride was usually 0.18 mg/kg, as shown in cumulative records for wild-type and heterozygous mice. In several D2 mutant mice, a tenfold higher dose of eticlopride was also tested (1.8 mg/kg, shown in cumulative record attop right, mouse #66). Bars over symbols depict SEM. Asterisks indicate that the number of cocaine injections earned was significantly higher after pretreatment with eticlopride by pairwise comparisons with vehicle pretreatment following overall main effect by ANOVA (n = 10, 13, and 8, for wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous mice, respectively; **p < 0.01). Bottom panels,Abscissa, Unit dose of quinelorane. S indicates saline injections. Ordinate, Mean number of quinelorane injections earned per hour. Asterisks indicate that the number of quinelorane injections earned was significantly higher than the number of saline injections earned by pairwise comparisons following overall main effect by ANOVA; (n = 4, 4, 8, for wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous mice, respectively; *p< 0.05, **p < 0.01).

When saline or the direct dopamine D2-like agonist quinelorane (0.1, 0.32, or 1.0 mg/kg per injection) was available, nose poke behavior was related to the unit dose of quinelorane by an inverted U-shaped dose–effect function in wild-type mice and heterozygous mutant mice (Fig. 5, bottom left and center panels). Specifically, a dose of 0.32 mg/kg per injection of quinelorane served as a positive reinforcer in wild-type mice and heterozygous D2 mutant mice (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05 compared with saline, respectively). A lower dose of quinelorane (0.1 mg/kg per injection) also served as a positive reinforcer in heterozygous mutant mice (p < 0.01). In contrast to the effects of quinelorane in wild-type mice and heterozygous D2 mutant mice, across the dose range examined, quinelorane did not function as a positive reinforcer in mutant mice that lacked the D2 receptor (Fig. 5, bottom right panel). In homozygous D2 mutant mice, rates of quinelorane-maintained responding were not different from rates of saline-maintained responding across the dose–range studied.

Receptor binding and pharmacokinetics of novel D2-like receptor ligands

Table 1 showsKi values of novel ligands for the D2-like receptor subtypes as measured in vitro.l-741,626 displayed high affinity for D2 receptors with ∼20-fold and 80-fold selectivity over D3 and D4 receptors, respectively. l-745,829 displayed at least 40-fold selectivity for D3 over D2 receptors, and this ligand had the highest affinity for D3 receptors among the novel compounds. However,l-745,829 also had high-affinity D4 receptors.l-745,870 is a D4-selective ligand with at least 1000-fold selectivity over D2 and D3 receptors (Patel et al., 1997). All three compounds are antagonists based on their reversal of dopamine agonist-mediated inhibition of forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation in clonal cell lines that expressed the appropriate receptor subtype (l-741,626 and l-745,829, K. L. Chapman, R. Marwood, and S. Patel, unpublished observations; l-745,870,Patel et al., 1997).

Table 1.

Inhibition of [3H]-spiperone binding to cloned rat D2, D3, and D4receptors1-a

| l-741,626 | l-745,829 | l-745,870 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| D2 | 7.1 (6.3–8.3) | >1900 | 1600 (1500–1700) |

| D3 | 155 (92–261) | 46.5 (27–79) | 6200 (5100–7000) |

| D4 | 596 (502–707) | 2.7 (2.4–3.1) | 1.5 (1.4–1.6) |

Data are meanKi values (low and high errors of the mean in parentheses) determined from three to four separate experiments as previously described (Patel et al., 1997). Values forl-745,870 were taken from Patel et al. (1997).

Analysis of brain and plasma samples after systemic administration of these compounds indicated excellent CNS penetration with brain concentrations at least seven times higher than plasma concentrations. Thirty minutes after administration of 0.1, 1.0, and 10.0 mg/kg, brain concentrations were 13, 160, and 3800 ng/gm for l-741,626, and 26, 300, and 2700 ng/gm for l-745,829. In a previous study, we determined that 15 min after administration of 3.0 mg/kg, brain concentrations were 5100 ng/gm for l-745,870 and that the elimination half-life of this compound in rat plasma was 2.1 hr (Patel et al., 1997). Thus, these dopamine receptor antagonists have differing binding affinities for rat D2, D3, and D4 receptors in vitro, but all three compounds appear to have CNS bioavailabilityin vivo. We used l-741,626,l-745,829, and l-745,870 to examine the roles of D2, D3/D4, and D4 receptors, respectively, in the reinforcing effects of cocaine in rats.

Effects of novel D2-like antagonists on cocaine self-administration behavior in rats

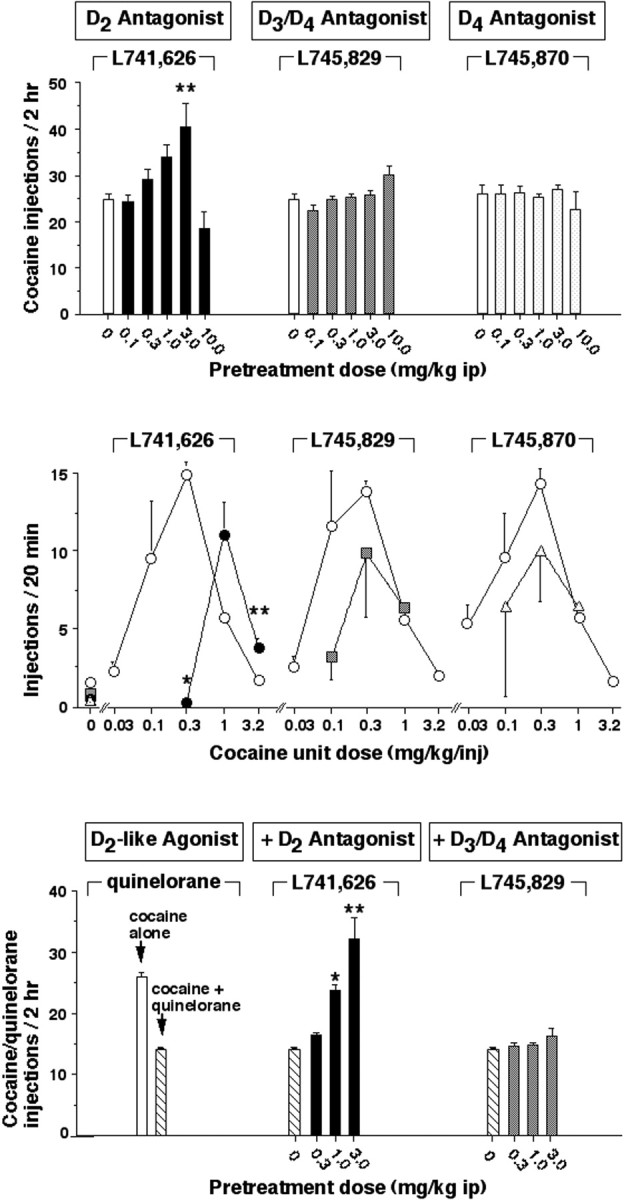

Figure 6 shows the effects of pretreatment with novel D2-like antagonists on the self-administration of cocaine (top and middle panels) or cocaine in combination with the D2-like agonist quinelorane (bottom panel) in rats. Pretreatment with the antagonist with highest affinity and selectivity for the D2 receptor (l-741,626) dose-dependently and significantly increased rates of self-administration of 1.0 mg/kg per injection of cocaine (top panel; 3.0 mg/kg i.p., p < 0.01). The highest dose of l-741,626 (10.0 mg/kg i.p.) disrupted patterns of cocaine-maintained responding. In contrast to the effects of l-741,626, the D3/D4 antagonistl-745,829 and the D4 selective antagonistl-745,870 did not significantly alter self-administration of 1.0 mg/kg cocaine across the dose range tested (0.1–10.0 mg/kg, i.p.)

Fig. 6.

Effects of novel D2-like antagonists on the self-administration of cocaine or cocaine combined with the D2-like agonist quinelorane in male Sprague Dawley rats. Abscissa, Pretreatment dose of novel D2-like antagonists (top and bottom rows) or unit dose of cocaine per injection (center row). In the top and bottom rows, the unit dose of cocaine was 1.0 mg/kg per injection, and in the bottom row this dose of cocaine was combined with 1.0 μg/kg per injection of quinelorane (hatched and filled bars). In the center row, the pretreatment dose of novel D2-like antagonists was 5.6 mg/kg, given intraperitoneally. Ordinate, Mean total number of drug injections earned in 2 hr (top andbottom rows) or 20 min (center row). Bars over symbols depict SEM. Asterisks indicate that the number of drug injections earned was significantly different after pretreatment with the novel D2-like antagonist by pairwise comparisons with vehicle pretreatment following overall main effect by ANOVA (n = 8, 6, and 5, for top, middle,and bottom rows, respectively; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

When the self-administration of various unit doses of cocaine was examined, self-administration behavior was related to the unit dose of cocaine according to an inverted U-shaped dose-effect function (Fig. 6,center row). The effects of various doses of the pretreatment drugs (0.1–10.0 mg/kg) were probed in a few rats, and a dose of 5.6 mg/kg was chosen for further testing because pretreatment with all three drugs at this dose decreased rates of responding maintained by low cocaine doses in some rats. Pretreatment withl-741,626 (5.6 mg/kg, i.p.) significantly decreased rates of self-administration of 0.32 mg/kg per injection of cocaine (p < 0.05) and increased rates of self-administration of a higher dose of cocaine (3.2 mg/kg per injection; p < 0.01). Overall,l-741,626 produced a rightward shift of the dose–effect function for cocaine self-administration. In contrast, pretreatment with the D3/D4 antagonist l-745,829 and the selective D4 antagonist l-745,870 (5.6 mg/kg, i.p.) decreased responding maintained by low doses of cocaine in some rats, but these effects were not statistically significant. Also in contrast to the effects of l-741,626, pretreatment with l-745,829 andl-745,870 (5.6 mg/kg, i.p.) did not significantly increase self-administration of a dose of cocaine on the descending limb of cocaine dose–effect function (1.0 mg/kg per injection).

Because results from previous studies suggested a role for D3 receptors in the effects of D2-like agonists administered in combination with cocaine (Caine and Koob, 1993; Caine et al., 1997), we compared the effects of pretreatment with the D2 antagonist l-741,626 and the D3/D4 antagonist l-745,829 on the self-administration of a combination of cocaine and quinelorane (Fig.6, bottom row). The addition of quinelorane (1.0 μg/kg per injection) to the self-administered cocaine solution (1.0 mg/kg per injection) decreased rates of cocaine self-administration to approximately half those observed with cocaine alone. Pretreatment withl-741,626 (1.0 and 3.0 mg/kg, i.p.) dose-dependently and significantly increased self-administration of the cocaine–quinelorane solution (p < 0.05 andp < 0.01, respectively). In contrast to the effects of the D2 antagonist l-741,626, pretreatment with the D3/D4 antagonist l-745,829 (0.3–3.0 mg/kg per injection) did not alter rates of self-administration of the cocaine–quinelorane solution.

DISCUSSION

There were two major findings in the present study. First, mice lacking the dopamine D2 receptor readily self-administered cocaine, and the ascending limb and peak of the cocaine self-administration dose–effect curves were identical in D2 mutant mice and their wild-type littermates. These results suggest that the D2 receptor subtype is not necessary for the reinforcing effects of cocaine. Second, when high cocaine doses on the descending limb of the cocaine dose–effect curve were available, rates of self-administration were approximately twofold higher in D2 mutant mice compared with wild-type mice. In addition, a D2-like antagonist did not modify cocaine self-administration behavior in mice lacking the D2 receptor but expressing D3 and D4 receptors. Moreover, in intact rats, a D2 antagonist increased rates of high-dose cocaine self-administration, whereas D3 and D4 antagonists were ineffective. These results suggest that the D2 receptor, but not D3 or D4 receptors, is involved in the mechanisms that serve to limit rates of high-dose cocaine self-administration in mice and rats.

Food and cocaine-maintained responding in D2 receptor mutant mice

Responding maintained by food presentation was evaluated in D2 mutant mice and wild-type littermates to assess the influence of the mutation on patterns of responding maintained by a nondrug reinforcer. Food presentation maintained responding in both D2 mutant mice and wild-type mice; however, D2 mutants responded at lower rates and earned fewer food reinforcers than wild-type mice across a broad range of liquid food concentrations. These results are consistent with previous findings suggesting that D2 mutants are less active than wild-type mice (Baik et al., 1995; Kelly et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2000).

Cocaine injections also maintained responding in both D2 mutant mice and wild-type mice. Results from drug self-administration studies in other species suggest that the D2 receptor may be important for the reinforcing effects of cocaine, because blockade of D2 receptors produces rightward shifts in the dose–effect curve for cocaine self-administration, and D2 agonists serve as positive reinforcers when substituted for cocaine (Bergman et al., 1990; Caine and Koob, 1993,1994b; Caine et al., 1999a) (for review, see Woolverton and Johnson, 1992; Mello and Negus, 1996). In agreement with these earlier studies conducted primarily in rats and nonhuman primates, in intact mice in the present study, the D2-like antagonist eticlopride produced a rightward shift in the dose–effect curve for cocaine self-administration, and the D2-like agonist quinelorane maintained drug self-administration behavior. Moreover, quinelorane was not self-administered by D2 mutant mice, which suggests that the D2 receptor was necessary for quinelorane self-administration. In view of this evidence implicating the D2 receptor in psychomotor stimulant self-administration in general and cocaine self-administration in particular, it is surprising that cocaine functioned as a positive reinforcer in mice that lacked the D2 receptor. Overall, these results suggest that although the D2 receptor may be necessary for the self-administration of some drugs (i.e., D2-like agonists), this receptor subtype is not necessary for the initiation or maintenance of cocaine self-administration in mice.

Lack of evidence for major roles of D3 and/or D4 receptors in cocaine self-administration

Because the homozygous D2 mutant mice in this study expressed D3 and D4 receptors (Baik et al., 1995), binding of dopamine to D3 and/or D4 dopamine receptors could have played a role in the reinforcing effects of cocaine. This hypothesis was suggested by previous findings that the relative potencies of D2-like agonists to potentiate or mimic the behavioral effects of cocaine were highly correlated with their relative affinities for D3 receptors (Caine and Koob, 1993; Spealman, 1996; Caine et al., 1997). In addition, a role for D4 receptors in the sensitivity to the psychomotor effects of cocaine was suggested (Rubinstein et al., 1997). However, our findings do not support a major role for D3 and/or D4 receptors in cocaine self-administration for several reasons. First, the D2-like antagonist eticlopride binds with high affinity to both D2 and D3 receptors (Tang et al., 1994), and eticlopride altered the self-administration of cocaine in wild-type mice but not in mice that lacked the D2 receptor. These findings suggest that blockade of D3 receptors by eticlopride in D2 mutant mice was not sufficient to alter cocaine self-administration. Second, the D2-like agonist quinelorane binds with high affinity to D2, D3, and D4 receptors (Gackenheimer et al., 1995; Sautel et al., 1995; Gilliland and Alper, 2000), and quinelorane served as a positive reinforcer in wild-type mice but not in D2 mutant mice. These results suggest that activation of D3 and D4 receptors by quinelorane was not sufficient to maintain drug self-administration behavior in D2 mutant mice. Overall, these findings suggest that D3 and D4 receptors do not play crucial roles in the reinforcing effects of cocaine in mice that lack the D2 receptor. However, it has been suggested that D3 receptors modulate cooperative D1/D2 receptor interactions (Xu et al., 1997). Roles for D3 and/or D4 receptors in the behavioral effects of cocaine that may occur through an interaction with the D2 receptor would not be observed in mice that lack the D2 receptor.

We also conducted complementary studies in intact, outbred Sprague Dawley rats. In rats, the novel D2-like antagonist with the highest affinity and selectivity for the D2 subtype (l-741,626) altered the self-administration of cocaine and quinelorane, whereas other antagonists with the highest affinities and selectivities for D3 and D4 receptors (l-745,829 and l-745,870) did not. Several lines of evidence suggest that the ineffectiveness of the D3 and D4 preferring ligands were not attributable to pharmacokinetic factors. First, all three compounds exhibited excellent brain penetration after systemic administration as measured by HPLC inex vivo brain samples. Second,l-745,829 reversed hypothermia induced by a D2-like dopamine agonist in rats (ED50 1.0 mg/kg; R. Marwood and S. Patel, unpublished observations), suggesting bioactivity of this compound in vivo. Third, estimates of D4 receptor occupancyin vivo suggested that 1.0 mg/kg ofl-745,870 occupies up to 90% of D4 receptors in the mouse brain (Patel et al., 1997). Collectively, these results suggest that D3 and D4 receptors do not play crucial roles in cocaine self-administration behavior. Our findings are in agreement with results from other recent studies suggesting that D3 and D4 receptors do not play prominent roles in various behavioral effects of psychomotor stimulant drugs (Boulay et al., 1999a,b; Ralph et al., 1999; Xu et al., 1999; Bristow et al., 1997; Costanza and Terry, 1998;Millan et al., 1998, 2000; Reavill et al., 2000).

Given that D3 and D4 receptors probably did not mediate the reinforcing effects of cocaine in D2 mutant mice, it is likely that D1-like receptors and/or nondopaminergic mechanisms were important. Evaluation of these alternative mechanisms was beyond the scope of the present study; however, previous findings suggest that both D1 receptors (for review, see Woolverton and Johnson, 1992; Mello and Negus, 1996) and nondopaminergic mechanisms (Rocha et al., 1998a,b; Sora et al., 1998,2001; White, 1998) may contribute to the reinforcing effects of cocaine under at least some circumstances. A critical role for D1 receptors remains to be established, because results of previous studies suggested that D1 receptor mutant mice were abnormal in their psychomotor and conditioned responses to cocaine under some circumstances, but not others (Xu et al., 1994a,b; Caine et al., 1995;Miner et al., 1995; Crawford et al., 1997; Xu et al., 2000). Ongoing studies with D1 receptor mutant mice given access to cocaine self-administration under identical circumstances to those established in this study may provide additional information on this subject (Gabriel et al., 2001).

Increased self-administration of high but not low doses of cocaine in mutant mice

One major finding of the present study was that rates of self-administration were significantly higher in mutant mice than in wild-type mice when high, but not low, doses of cocaine were available for self-administration. Before considering the implications of these findings, it is necessary to consider several caveats of studies with mutant mice that may have contributed to the results. One potential confound arises from the generation of mutants from two parental inbred strains (C57BL/6 and 129/Sv). If there are differences in the cocaine self-administration behavior of the parental strains, then the different phenotypes observed could have resulted from an interplay between various genes, rather than mutation of the D2 receptor gene alone (Gerlai, 1996; Phillips et al., 1999; Lariviere et al., 2001). However, several lines of evidence suggest that the D2 mutation itself was responsible for the increased cocaine self-administration observed in D2 mutant mice in the present study. First, in previous studies of locomotor stimulation, C57BL/6 mice did not differ from 129/Sv mice in their responses to cocaine (Miner, 1997). Second, dose–response curves for cocaine self-administration of wild-type C57BL/6 × 129/Sv mice in the present study were comparable with those observed previously in C57BL/6 inbred mice (Caine et al., 1999b), and this suggests that interbreeding of C57BL/6 and 129/Sv mice itself did not alter the reinforcing effects of cocaine. Finally, both genetic deletion of the D2 receptor and pharmacological blockade of the D2 receptor increased self-administration of high cocaine doses in the present study. Thus, a parsimonious interpretation of the present results is that increased self-administration of high cocaine doses on the descending limb of the cocaine dose–effect curve was related to altered function of the D2 receptor in both mutant mice and intact rodents treated with a D2 antagonist.

Self-administration of high cocaine doses on the descending limb of the cocaine dose–effect curve often occurs with remarkably regular interinjection intervals under fixed ratio schedules of reinforcement (Pickens and Thompson, 1968; Woods and Schuster, 1968; Wilson et al., 1971; Goldberg and Kelleher, 1976). Moreover, as unit dose increases in this dose range, the interinjection intervals also increase. As a result, overall drug intake remains relatively constant, whereas the number of injections per unit time decreases to generate the descending limb of the dose–effect curve. This orderly relationship between self-administration behavior and unit dose suggests that rates of high-dose cocaine self-administration are tightly regulated. It has been suggested that this phenomenon reflects either direct rate-decreasing effects of the drug on responding or titration of drug intake by the organism to achieve optimal brain levels, or both (Balster and Schuster, 1973; Wise et al., 1977; Herling et al., 1979; Ranaldi et al., 1999) (for review, see Woods et al., 1987; Katz, 1989). Although the present study was not designed to directly address the nature of the regulation, it is notable that three mutant mice self-administered cocaine to lethal overdose before experimenter-imposed limits were placed on total drug intake (see Materials and Methods). Lethal cocaine overdose during self-administration tests was also observed in three wild-type mice treated with a D2 antagonist. Collectively, these findings suggest that the D2 receptor plays a role in regulatory processes that normally limit high-dose cocaine intake.

A second major finding of the present study was that mutation of the D2 receptor did not decrease low dose cocaine self-administration or produce a rightward shift in the cocaine dose–effect curve, suggesting that any changes in high-dose cocaine self-administration did not result from an overall reduction in the potency of cocaine as a reinforcer. In a previous report, treatment with a dopamine antagonist also selectively increased self-administration of a high dose of cocaine on the descending limb of the cocaine dose–effect curve, without altering self-administration of lower cocaine doses on the ascending limb of the cocaine dose–effect curve (Woods et al., 1978). However, the range of conditions under which dopamine antagonists produce this selective effect on high-dose cocaine self-administration appears to be limited, and it has been more widely reported that dopamine antagonists decreased self-administration of lower cocaine doses and produced an overall rightward shift in the inverted-U shaped cocaine dose–effect curve (Bergman et al., 1990; Negus et al., 1996; present study). Such rightward shifts have sometimes been interpreted as reflecting attenuation of the reinforcing effects of cocaine. However, an alternative hypothesis is that dopamine antagonist-induced decreases in low dose cocaine self-administration result from direct rate-decreasing effects of the antagonist on operant behavior rather than from blockade of the reinforcing effects of cocaine (Woods et al., 1987). In support of this latter hypothesis, decreased self-administration of low cocaine doses after treatment with dopamine antagonists usually do not resemble patterns of saline self-administration, and doses of dopamine antagonists that decreased low-dose cocaine self-administration also usually decreased responding maintained by food or other reinforcers (Herling and Woods, 1980;Woolverton and Virus, 1989; Caine and Koob, 1994b; Winger, 1994; Negus et al., 1996). One explanation for the fact that dopamine antagonists decrease low-dose but not high-dose cocaine self-administration comes from the reciprocal antagonism between cocaine and dopamine antagonists on rates of responding (Herling and Woods, 1980; Woods et al., 1987). In mechanistic terms, high but not low cocaine doses presumably increase dopamine levels sufficiently to compete with the antagonist for occupation of dopamine receptors, thereby surmounting the rate-decreasing effects of the antagonist. Overall, our findings illustrate an important difference in the effects of genetic mutation of the D2 receptor as opposed to acute pharmacological blockade of the receptor. Specifically, genetic mutation of the receptor produced modest deficits in motor activity that did not impair low-dose cocaine self-administration, whereas dopamine antagonist administration to an organism with functional D2 receptors usually produced profound motor deficits and decreased low-dose cocaine self-administration. One possible explanation for this difference is that mice with lifelong mutations of the D2 receptor may overcome some of the motor deficits induced by D2 receptor disruption through compensatory mechanisms.

Finally, it is important to note that increased rates of high-dose cocaine self-administration in D2 mutant mice are probably not a result of general increases in operant responding. Although D2 mutant mice responded at higher rates than wild types during high-dose cocaine self-administration, they responded at lower rates than wild types during food-maintained responding. In addition, previous studies have found that D2 mutant mice are less active than wild-type mice in tests of locomotor activity (Baik et al., 1995; Kelly et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2000). Taken together, these findings suggest that mutation of the D2 receptor selectively increases high-dose cocaine self-administration and that the D2 receptor may be involved in processes that normally limit high-dose cocaine intake.

Implications for mechanisms underlying cocaine addiction in humans

In humans, D2 receptor levels were correlated with the subjective effects of the drug methylphenidate, and interestingly, low D2 receptor levels were predictive of pleasant subjective responses (Volkow et al., 1999a,b). Moreover, in recent studies with a group of rhesus monkeys, lower levels of D2 receptors predicted higher rates of cocaine self-administration (Nader et al., 2001; Morgan et al., 2002). In addition, cocaine self-administration experience was associated with decreased D2 receptor densities in the basal ganglia and other brain regions of both humans and nonhuman primates (Volkow et al., 1990,1993; Moore et al., 1998; Nader et al., 2001). These findings suggest that D2 receptors are involved in the subjective effects of cocaine in humans and that D2 receptor levels may be inversely correlated with rates of cocaine self-administration in monkeys. Moreover, the observations that D2 receptor levels are decreased by cocaine self-administration experience suggest that a dynamic process involving D2 receptor levels may contribute to altered cocaine self-administration behavior over time.

Prolonged cocaine self-administration behavior leads to escalated cocaine intake in laboratory animals when subjects are given access to high doses of the drug (Ahmed and Koob, 1998). Such escalated drug intake has been proposed as a hallmark of the transition from drug self-administration to drug addiction (Ahmed and Koob, 1998; Koob and LeMoal, 2001). Although speculative, it is possible that escalation of drug intake results at least in part from tolerance to the effects of cocaine that serve to limit high-dose cocaine self-administration. Our findings suggest that D2 receptors are not required for the reinforcing effects of cocaine, but that this receptor is involved in mechanisms that normally limit high-dose cocaine self-administration. The positive reinforcing effects of cocaine, the regulation of cocaine intake and the development of cocaine addiction no doubt involve complex interactions among multiple neural systems. Based on our present findings and previous findings from studies in human and nonhuman primates, we suggest that decreased D2 receptor levels and related neural adaptations may be involved in the escalation of cocaine intake that contributes to the development of cocaine addiction.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grants R29-DA12142, K05-DA00101, and P50-DA04059 and also Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Université Louis Pasteur, Hopitaux Universitaries Strasbourg, Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer, and Mission Interministérielle à la Lutte contre la Drogue et la Toxicomanie. We thank Jennifer M. Dohrmann for outstanding technical assistance.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. S. Barak Caine, McLean Hospital, Alcohol and Drug Abuse Research Center, 115 Mill Street, Belmont, MA 02478. E-mail: barak@mclean.harvard.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed SH, Koob GF. Transition from moderate to excessive drug intake: change in hedonic set point. Science. 1998;282:298–300. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5387.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baik J-H, Picetti R, Saiardi A, Thirlet G, Dierich A, Depaulls A, Le Meur M, Borrelli E. Parkinsonian-like locomotor impairment in mice lacking dopamine D2 receptors. Nature. 1995;377:424–428. doi: 10.1038/377424a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barr JE, Holmes DB, Ryan LJ, Sharpless SK. Techniques for the chronic cannulation of the jugular vein in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1979;11:115–118. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(79)90307-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balster RL, Schuster CR. Fixed-interval schedule of cocaine reinforcement: effect of dose and infusion duration. J Exp Anal Behav. 1973;20:119–129. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1973.20-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baxter BL, Gluckman MI, Stein L, Scerni RA. Self-injection of apomorphine in the rat: Positive reinforcement by a dopamine receptor stimulant. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2 1974. 387 391; 1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergman J, Madras BK, Johnson SE, Spealman RD. Effects of cocaine and related drugs in nonhuman primates. III. Self-administration by squirrel monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;251:150–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergman J, Kamien JB, Spealman RD. Antagonism of cocaine self-administration by selective dopamine D1 and D2 antagonists. Behav Pharmacol. 1990;1:355–363. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199000140-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boulay D, Depoortere R, Rostene W, Perrault G, Sanger DJ. Dopamine D3 receptor agonists produce similar decreases in body temperature and locomotor activity in D3 knock-out and wild-type mice. Neuropharmacology. 1999a;38:555–565. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boulay D, Depoortere R, Perrault G, Borrelli E, Sanger DJ. Dopamine D2 receptor knock-out mice are insensitive to the hypolocomotor and hypothermic effects of dopamine D2/D3 receptor agonists. Neuropharmacology. 1999b;38:1389–1396. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bristow LJ, Collinson N, Cook GP, Curtis N, Freedman SB, Kulagowski JJ, Leeson PD, Patel S, Ragan CI, Ridgill M, Saywell KL, Tricklebank MD. l-745,870, a subtype selective dopamine D4 receptor antagonist, does not exhibit a neuroleptic-like profile in rodent behavioral tests. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:1256–1263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burris KD, Pacheco MA, Filtz TM, Kung M-P, Kung HF, Molinoff PB. Lack of discrimination by agonists for D2 and D3 dopamine receptors. Neuropscyhopharmacology. 1995;12:335–345. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(94)00099-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caine SB, Koob GF. Modulation of cocaine self-administration in the rat through D-3 dopamine receptors. Science. 1993;260:1814–1816. doi: 10.1126/science.8099761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caine SB, Koob GF. Effects of mesolimbic dopamine depletion on responding maintained by cocaine and food. J Exp Anal Behav. 1994a;61:213–221. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1994.61-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caine SB, Koob GF. Effects of dopamine D-1 and D-2 antagonists on cocaine self-administration under different schedules of reinforcement in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994b;270:209–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caine SB, Koob GF. Pretreatment with the dopamine agonist 7-OH-DPAT shifts the cocaine self-administration dose-effect function to the left under different schedules in the rat. Behav Pharmacol. 1995;6:333–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caine SB, Lintz R, Koob GF. Behavioral neuroscience: a practical approach (Sahgal A, ed) Oxford UP; Oxford: 1993. Intravenous drug self-administration techniques in animals. pp. 117–143. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caine SB, Gold LH, Koob GF, Deroche V, Heyser C, Polis I, Robers A, Xu M, Tonegawa S. Intravenous cocaine self-administration in mice: strain differences and effects of D-1 dopamine receptor targeted gene mutation. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1995;21:719. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caine SB, Koob GF, Parsons LH, Everitt BJ, Schwartz JC, Sokoloff P. D3 receptor test in vitro predicts decreased cocaine self-administration in rats. NeuroReport. 1997;8:2373–2377. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199707070-00054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caine SB, Negus SS, Mello NK, Bergman J. Effects of D1-like and D2-like agonists in rats that self-administer cocaine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999a;291:353–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caine SB, Negus SS, Mello NK. Method for training operant responding and evaluating cocaine self-administration behavior in mutant mice. Psychopharmacology. 1999b;147:22–24. doi: 10.1007/s002130051134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caine SB, Negus SS, Mello NK. Effects of D1-like and D2-like agonists on cocaine self-administration in rhesus monkeys: rapid assessment of cocaine dose-effect functions. Psychopharmacology. 2000a;148:41–51. doi: 10.1007/s002130050023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caine SB, Negus SS, Mello NK, Bergman J. Effects of D1-like and D2-like agonists in rats trained to discriminate cocaine from saline: influence of experimental history. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000b;8:404–414. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng KC, Prusoff WH. Relationship between the inhibition constant (Ki) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 percent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Costanza RM, Terry P. The dopamine D4 receptor antagonist l-745,870: effects in rats discriminating cocaine from saline. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;345:129–132. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01603-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crawford CA, Drago J, Watson JB, Levine MS. Effects of repeated amphetamine treatment on the locomotor activity of the dopamine D1A deficient mouse. NeuroReport. 1997;8:2523–2527. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199707280-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De La Garza R, Johanson CE. Effects of haloperidol and physostigmine on self-administration of local anesthetics. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1982;17:1295–1299. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(82)90138-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deroche V, Caine SB, Heyser C, Polis I, Koob GF, Gold LH. Differences in the liability to self-administer intravenous cocaine between C57BL6×SJL and BALB/cByJ mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1997;57:429–440. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(96)00439-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.deWit H, Wise RA. Blockade of cocaine reinforcement in rats with the dopamine receptor blocker pimozide, but not with the noradrenergic blockers phentolamine or phenoxybenzamine. Can J Psychol. 1977;31:195–203. doi: 10.1037/h0081662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emmett-Oglesby MW, Peltier RL, Depoortere RY, Pickering CL, Hooper ML, Gong YH, Lane JD. Tolerance to self-administration of cocaine in rats: timecourse and dose-response determinants using a multi dose method. Drug Alchohol Depend. 1993;32:247–256. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(93)90089-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gackenheimer SL, Schaus JM, Gehlert DR. [3H]-quinelorane binds to D2 and D3 dopamine receptors in the rat brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;274:1558–1565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gabriel KI, Caine SB, Berkowitz KS, Zhang J, Xu M. Evaluation of operant behavior in dopamine D1 receptor knockout mice: implications for cocaine self-administration studies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;63:S51. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerlai R. Gene-targeting studies of mammalian behavior: is it the mutation or the background genotype? Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:177–181. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)20020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gill CA, Holz WC, Zirkle CL, Hill H. Pharmacological modification of cocaine and apomorphine self-administration in the squirrel monkey. In: Deniker P, Radouco-Thomas C, Villeneuve A, editors. Proceedings of the 10th Congress of the Collegium Internationale Neuro-Psycho-Pharmacologicum. Pergamon; New York: 1978. pp. 1477–1484. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilliland SL, Alper RH. Characterization of dopaminergic compounds at hD2short, hD4.2 and hD4.7 receptors in agonist-stimulated [35S]GTPgammaS binding assays. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2000;361:498–504. doi: 10.1007/s002100000224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldberg SR, Kelleher RT. Behavior controlled by scheduled injections of cocaine in squirrel and rhesus monkeys. J Exp Analysis Behav. 1976;25:93–104. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1976.25-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grech DM, Spealman RD, Bergman J. Self-administration of D1 receptor agonists by squirrel monkeys. Psychopharmacology. 1996;125:97–104. doi: 10.1007/BF02249407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herling S, Woods JH. Chlorpromazine effects on cocaine-reinforced responding in rhesus monkeys: reciprocal modification of rate-altering effects of the drugs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1980;214:354–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herling S, Downs DA, Woods JH. Cocaine, d-amphetamine, and pentobarbital effects on responding maintained by food or cocaine in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology. 1979;64:261–269. doi: 10.1007/BF00427508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katz JL. Drugs as reinforcers: pharmacological and behavioural factors. In: Lieberman JM, Cooper SJ, editors. The neuropharmacological basis of reward. Oxford UP; Oxford: 1989. pp. 165–212. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelly MA, Rubinstein M, Phillips TJ, Lessov CN, Burkhart-Kasch S, Zhang G, Bunzow JR, Fang Y, Gerhardt GA, Grandy DK, Low MJ. Locomotor activity in D2 dopamine deficient mice is determined by gene dosage, genetic background, and developmental adaptations. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3470–3479. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03470.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koob GF, Le Moal M. Drug addiction, dysregulation of reward, and allostasis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;24:97–129. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koob GF, Le HT, Creese I. The D1 dopamine receptor antagonist SCH23390 increases cocaine self-administration in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1987;79:315–320. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lamas X, Negus SS, Nader MA, Mello NK. Effects of the putative dopamine receptor agonist 7-OH-DPAT in rhesus monkeys trained to discriminate cocaine from saline. Psychopharmacology. 1996;124:306–314. doi: 10.1007/BF02247435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lariviere WR, Chesler EJ, Mogil JS . Transgenic studies of pain and analgesia: mutation or background genotype? J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;297:467–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mello NK, Negus SS. Preclinical evaluation of pharmacotherapies for treatment of cocaine and opioid abuse using drug self-administration procedures. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14:375–424. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00274-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mendelson JH, Mello NK. Management of cocaine abuse and dependence. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:965–972. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199604113341507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Merchant KM, Gill GS, Harris DW, Huff RM, Eaton MJ, Lookingland K, Lutzke BS, McCall RB, Piercey MF, Schreur PJ, Sethy VH, Smith MW, Srensson KA, Tang AH, Vonvoightlander PF, Tenbrick RE. Pharmacological characterization of U-101387, a dopamine D4 receptor selective antagonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;279:1392–1403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Millan MJ, Newman-Tacredi A, Brocco M, Gobert A, Lejeune F, Audinot V, Rivet J-M, Schreiber R, Dekeyne A, Spedding M, Nicolas J-P, Peglion J-L. S18126, a potent, selective and competitive antagonist at dopamine D4 receptors: an in vitro and in vivo comparison with L745,870 and raclopride. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;287:167–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Millan MJ, Dekeyne A, Rivet J-M, Dubuffet T, Lavielle G, Brocco M. S33084, a novel, potent, selective, and competitive antagonist at dopamine D3 receptors: II. Functional and behavioral profile compared with GR218,231 and L741,626. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293:1063–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miner LL. Cocaine reward and locomotor activity in C57BL/6J and 129Sv/J inbred mice and their F1 cross. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1997;58:25–30. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(96)00465-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miner LL, Drago J, Chamberlain PM, Donovan D, Uhl GR. Retained cocaine conditioned place preference in D1 receptor deficient mice. NeuroReport. 1995;6:2314–2316. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199511270-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moore RJ, Vinsant SL, Nader MA, Porrino LJ, Friedman DP. Effects of cocaine self-administration on dopamine D2 receptors in rhesus monkeys. Synapse. 1998;30:88–96. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199809)30:1<88::AID-SYN11>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morgan D, Grant KA, Gage HD, Mach RH, Kaplan JR, Prioleau O, Nader SH, Buchheimer N, Ehrenkaufer RL, Nader MA. Social dominance in monkeys: dopamine D2 receptors and cocaine self-administration. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:169–174. doi: 10.1038/nn798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nader MA, Mach RH. Self-administration of the dopamine D3 agonist 7-OH-DPAT in rhesus monkeys is modified by previous cocaine exposure. Psychopharmacology. 1996;125:13–22. doi: 10.1007/BF02247388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nader MA, Gage HD, Mach RH, Morgan D (2001) The use of PET imaging to examine the effects of cocaine and socially derived stress on dopamine D2 receptors in nonhuman primates. In: Problems of drug dependence 2001, Proceedings of the 63rd Annual Meeting (Harris LS, ed), NIDA Research Monograph. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.