Abstract

Although corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), a regulator of stress responses, acts through two receptors (CRH1 and CRH2), the role of CRH2 in stress responses remains unclear. Knock-out mice without the CRH2gene exhibit increased stress-like behaviors. This profile could result either directly from the absence of CRH2 receptors or indirectly from developmental adaptations. In the present study, CRH2 receptors were acutely blocked by α-helical CRH (αhCRH, CRH1/CRH2 antagonist; 0, 30, 100, and 300 ng) infusion into the lateral septum (LS), which abundantly expresses CRH2 but not CRH1receptors. Freezing, locomotor activity, and analgesia were tested after infusion. Intra-LS αhCRH blocked shock-induced freezing without affecting activity or pain responses; infusions into lateral ventricle or nucleus of the diagonal band had no effects. The same behavioral profile was obtained with d-Phe-CRH(12–41)(100 ng), another CRH1/CRH2 antagonist. A selective CRH1 antagonist (NBI27914), in doses that reduced freezing on intra-amygdala (central nucleus) infusion (0, 0.2, and 1.0 μg), did not affect freezing when infused into the LS.Ex vivo autoradiography revealed that binding of [125I]sauvagine, a mixed CRH1/CRH2 agonist, was prevented in the LS by previous intra-LS infusion of αhCRH but not NBI27914. In vitro studies demonstrated that [125I]sauvagine binding in the LS could be inhibited by a CRH1/CRH2 antagonist but not by the selective CRH1 receptor antagonist, confirming that in the LS, αhCRH antagonized exclusively CRH2receptors. Acute antagonism of CRH2 receptors in the LS thus produces a behaviorally, anatomically, and pharmacologically specific reduction in stress-induced behavior, in contrast to results of recent knock-out studies, which induced congenital and permanent CRH2 removal. CRH2 receptors may thus represent a potential target for the development of novel CRH system anxiolytics.

Keywords: CRF, anxiety, corticotropin-releasing hormone, corticotropin-releasing factor, defensive behavior, freezing, behavioral inhibition

Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) coordinates various aspects of the stress response (Vale et al., 1981). CRH elicits behaviors normally exhibited in response to stress, whereas CRH receptor antagonists prevent stress-induced behaviors (Koob and Heinrichs, 1999). Patients with stress-related problems such as depression often have alterations in their CRH system, suggesting that it may play an important role in stress-related psychopathology (Nemeroff et al., 1984; Mitchell, 1998).

Recently, CRH receptor antagonists have been developed as a novel class of anxiolytics and antidepressants (McCarthy et al., 1999). A preliminary open-label clinical trial indicated that these compounds alleviate symptoms in depressed patients (Zobel et al., 2000). Although there are two cloned CRH receptors (CRH1 and CRH2α,β,γ), most studies suggesting that CRH receptor antagonists may be psychotherapeutic agents have focused on the CRH1 subtype, perhaps because highly selective nonpeptide antagonists for CRH2αreceptors (splice variant expressed in brain) have not been identified (Perrin and Vale, 1999). Nonetheless, the very recent discovery of endogenous and highly selective CRH2–receptor ligands in rodent and human brain suggests that this receptor may play some intrinsic functional role (Hsu and Hsueh, 2001; Lewis et al., 2001; Reyes et al., 2001). Nonetheless, the role of CRH2α receptors in stress and anxiety remains unclear.

Antisense oligonucleotides have been used to study CRH2α receptor functioning in stress; however, interpretation of these studies is difficult, because they failed to demonstrate an appreciable reduction in CRH2αreceptors after oligonucleotide infusion (Heinrichs et al., 1997;Liebsch et al., 1999). Paradoxically, knock-out studies indicate that deletion of the CRH2α gene produces a phenotype characterized by increased anxiety-like behaviors (Bale et al., 2000;Coste et al., 2000; Kishimoto et al., 2000). One problem with interpreting these studies, however, is that the observed phenotype could be attributable to indirect developmental alterations resulting from the mutation rather than being a direct result of the gene deletion (Gingrich and Hen, 2000). Measurement of stress-related behavior after acute antagonism of CRH2αreceptors circumvents these confounds.

The distributions of CRH1 and CRH2α receptors in rodent brain are mostly nonoverlapping (Chalmers et al., 1995; Primus et al., 1997), suggesting that the role of CRH2α receptors in stress might be determined by antagonizing CRH receptors in a brain region selectively expressing the CRH2α receptor subtype. The lateral septum (LS) contains a high density of CRH2α receptors but is devoid of CRH1 receptors (Chalmers et al., 1995; Primus et al., 1997). Although learning a conditioned fear response involves CRH receptors in the LS (Lee, 1995; Radulovic et al., 1999), a selective role for the CRH2α receptor subtype in stress-induced behavior remains unclear.

The present studies tested the hypothesis that CRH2α receptor blockade in the LS would decrease stress-induced behavior by determining whether intra-LS infusion of αhCRH ord-Phe-CRH(12–41), CRH1/CRH2 receptor antagonists, reduced shock-induced freezing, a CRH-receptor-mediated defensive behavior displayed in response to fear (Kalin et al., 1988;Swiergiel et al., 1992, 1993). Effects of αhCRH on other behaviors or in neighboring regions were measured to assess the behavioral and anatomical specificity of LS-mediated effects. Receptor subtype specificity of LS-mediated effects was determined by comparing the effects of CRH1/CRH2antagonists with those of a selective CRH1antagonist, NBI27914 (Chen et al., 1996). Of particular interest was whether acute antagonism of CRH2α receptors would produce a different behavioral profile than that seen after CRH2α gene knock-out.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

One hundred seventy-four male Sprague Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories) were used in the present studies. Rats were housed in pairs in clear plastic cages in a temperature- and humidity-controlled vivarium and were maintained on an ad libitum diet of lab chow (Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) and water. Lights in the animal colony came on at 7 A.M. and turned off at 7 P.M.; all testing occurred between 11 A.M. and 4 P.M. On arrival, rats were handled gently by the experimenter to minimize stress during the experiments. Animal facilities were approved by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care; protocols were in accordance with the Guiding Principles in the Care and Use of Animals provided by the American Physiological Society and the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health. All efforts were made to prevent animal suffering and minimize the number of animals used for the studies.

Surgery

Within 1 week of arrival, animals were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (65 mg/kg; Butler Co., Columbus, OH), treated with 0.1 ml of atropine sulfate (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, St. Joseph, MO) to minimize respiratory distress, and placed into a stereotaxic apparatus (Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA). Stainless steel cannulas (23 gauge) were implanted bilaterally and affixed to the skull with dental cement (Lang Dental, Wheeling, IL) and skull screws (Small Parts, Miami Lakes, FL). Cannulas were aimed at the LS [coordinates were anteroposterior (AP), +0.4 mm from bregma; lateromedial (LM), ±0.8 mm from midline, and dorsoventral (DV), −3.5 mm from skull surface], the lateral ventricle (LV; coordinates were AP, −0.4 mm from bregma; LM, ±1.5 mm from midline; and DV, −2.2 mm from skull surface), the nucleus of the diagonal band (NDB; coordinates were AP, +0.4 mm from bregma; LM, ±0.8 mm from midline; and DV, −3.5 mm from skull surface), or the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA; coordinates were AP, −2.5 mm from bregma; LM, ±4.2 mm from midline; and DV, −5.2 mm from skull surface) (all coordinates based on the atlas of Paxinos and Watson, 1998). After surgery, rats were allowed 5–7 d to recover, during which time daily health checks were performed by the experimenter.

Drugs

α-Helical CRH (αhCRH) andd-Phe-CRH(12–41) were obtained from Bachem-Peninsula Laboratories (Torrance, CA) and were dissolved in sterile distilled water, pH 6.5. Thus, the vehicle treatment for all experiments in which αhCRH andd-Phe-CRH(12–41) were administered was distilled water, pH 6.5. NBI27914 was synthesized at Neurocrine Biosciences (Chen et al., 1996) and dissolved with sonication in a vehicle solution of 90% distilled water, 5% ethanol, and 5% cremophor EL (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). This vehicle solution was used as the control treatment for all experiments in which NBI27914 was administered into the brain. All doses (see below) were calculated using the HCl salt weight.

Microinfusion procedure

On all test days, animals were gently held, and their stylets were removed and placed into 70% ethanol. Cannulas were cleaned with a dental broach, and stainless steel injectors (30 gauge) were lowered so that they extended 1.5–5 mm below the tips of the cannulas. Thus, the final DV coordinates from skull surface were −6.0 mm for the LS, −3.7 mm for the LV, −8.5 mm for the NDB, and −8.2 mm for the CeA. The injectors were attached to polyethylene tubing, which was connected to 10 μl Hamilton microsyringes (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) that were mounted on a motorized pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). A total of 0.5 μl of vehicle or drug per side was delivered over 93 sec in each infusion. The pump was then shut off, and injectors were kept in place for an additional 60 sec to allow for absorption of the injection bolus into the tissue. Injectors were then removed; stylets were replaced; and animals were placed immediately into chambers for behavioral testing. Two to 3 d before drug testing, all rats received a mock infusion in which injectors were lowered but no solution was delivered to acclimate rats to the infusion procedure and to minimize stress attributable to injections on the test days.

Behavioral Testing

After drug infusions, rats were tested in one of the three following behavioral paradigms. For all studies, rats were placed into the behavioral testing apparatus immediately after drug infusion. The experimenter was blind to the treatment condition of the rats for all testing.

Shock-induced freezing. Rats were placed individually in a black Plexiglas chamber (21 × 11 × 6 inches) with a metal floor grid and overhead houselights (San Diego Instruments, La Jolla, CA). After a 2 min acclimation period to the chamber, three mild foot shocks were delivered (1 sec, 1.5 mA, separated by 20 sec). The onset and duration (in seconds) of freezing behavior (cessation of all body movements except that required for respiration) were rated for 15 min immediately after the final shock. To be counted as a bout of freezing, freezing behavior had to occur continuously for a minimum of 5 sec. This criterion was applied to minimize the possibility of obtaining spurious counts of freezing.

Locomotor activity. Rats were placed individually in clear polycarbonate cages (19 × 10.5 × 8 inches) equipped with computer-interfaced photocells along their long axis and cage top to measure unconditioned locomotor activity (San Diego Instruments). Rearing (vertical activity, total cage top photobeam breaks), ambulation (number of cage crossings), and total activity (total photobeam breaks) were recorded over 20 min to match the time course of the freezing test.

Analgesia. Rats were placed individually on a metal plate (prewarmed to 50°C) within a clear Plexiglas chamber (11 × 11 × 8 inches). The latency (in seconds) for the rat to lick its hindpaws after placement onto the plate was recorded. If licking did not occur, rats were removed by the experimenter after 60 sec had elapsed; these animals were given a score of 60.

Experimental design

Eleven experiments were conducted in separate groups of rats.

Effects of intra-LS CRH1/CRH2antagonists on shock-induced freezing. In experiment 1, rats were given infusions of either vehicle (distilled water; n = 10) or αhCRH (30 ng; n = 10) into the LS and placed into the freezing apparatus. In experiment 2, rats received either vehicle (n = 12) or a higher dose of αhCRH (100 ng;n = 12) into the LS and were tested for shock-induced freezing. In experiment 3, either vehicle (n = 6) or 300 ng of αhCRH (n = 6) was infused into the LS before testing in the freezing apparatus. The doses of αhCRH used in the present experiments were chosen on the basis of previous reports that infusion of 100–200 ng of this antagonist per side into either the locus ceruleus or amygdala reduces shock-induced freezing (Swiergiel et al., 1992, 1993). Finally, an additional experiment was performed to confirm that a different more potent CRH1/CRH2 antagonist would have the same effects on freezing as αhCRH. Thus, in experiment 4, either vehicle (n = 8) or 100 ng ofd-Phe-CRH(12–41) (Menzaghi et al., 1994) (n = 7) was infused into the LS, and rats were then tested for shock-induced freezing. In this experiment, a 1.0 mA shock intensity was used instead of 1.5 mA to ascertain that baseline latency and duration of freezing in vehicle-treated rats were not influenced by this difference in shock intensity.

Effects of intra-LS CRH1/CRH2antagonists on locomotor activity and analgesia. Because potential changes in freezing may not necessarily reflect changes in stress-induced behavior but rather may simply be an artifact of altered motor activity levels or pain responses caused by the drug, the effects of CRH1/CRH2 antagonists on baseline locomotor activity and analgesia were tested. Thus, in experiment 5, rats were given a wide dose range of αhCRH (0, 30, 100, or 300 ng; n = 11) into the LS and placed into photocell cages. All animals received all αhCRH doses in a counterbalanced order over 4 test days. All rats had been habituated to the test cages and infusion procedure a few days before testing; successive tests were separated by 3 d. In a separate set of rats that were naive to the testing chambers, the effects ofd-Phe-CRH(12–41) (0 or 100 ng; n = 6 per group) were evaluated to corroborate αhCRH findings and also to be certain that the rat's level of familiarity with the given testing chamber did not influence the CRH antagonist-induced effects (experiment 6). In this experiment, rats were tested only once, and separate animals were used for the different treatment groups so that all testing would occur on the first day that the rats were introduced to the testing chamber; this protocol was chosen to match that of the freezing experiments. In experiment 7, rats were tested for potential changes in pain sensitivity after receiving intra-LS infusion of αhCRH (0 or 100 ng). Testing was conducted over 2 test days that were separated by 1 week. On the first test day, half of the rats received vehicle, and the other half got αhCRH before being placed onto the hotplate. One week later, this protocol was repeated, balancing the treatments such that animals that had previously received αhCRH got vehicle and rats that previously received vehicle got αhCRH. Three separate sets of rats were used for this experiment: one was tested 3 min after the infusions (n = 7; to correspond to the time point at which shock was delivered in the freezing paradigm); another was tested 10 min after the infusions (n = 6); and the final group was tested 15 min after the infusions (n = 5). These different time points were selected to map out the duration of the freezing test and to determine whether there were any alterations in pain sensitivity produced by αhCRH at any time during this 15 min period.

Effects on shock-induced freezing of αhCRH infusion into regions neighboring the LS. To confirm that the behavioral effects observed after intra-LS infusion of αhCRH were localized specifically to the LS and not attributable to diffusion of the drug to other areas, the effects on freezing of αhCRH infusion into regions neighboring the LS were determined. Because the LS is bordered by the lateral ventricle, experiment 8 was performed to determine whether direct intra-LV infusion of αhCRH in the present dose range would affect freezing. The same protocol as in experiment 2 was used, except that intracranial infusions were made into the LV (vehicle,n = 9; 100 ng of αhCRH, n = 9). Experiment 9 was also identical to experiment 2, except that infusions were delivered into the NDB (vehicle, n = 8; 100 ng of αhCRH, n = 10). The NDB is ventrally adjacent to the LS.

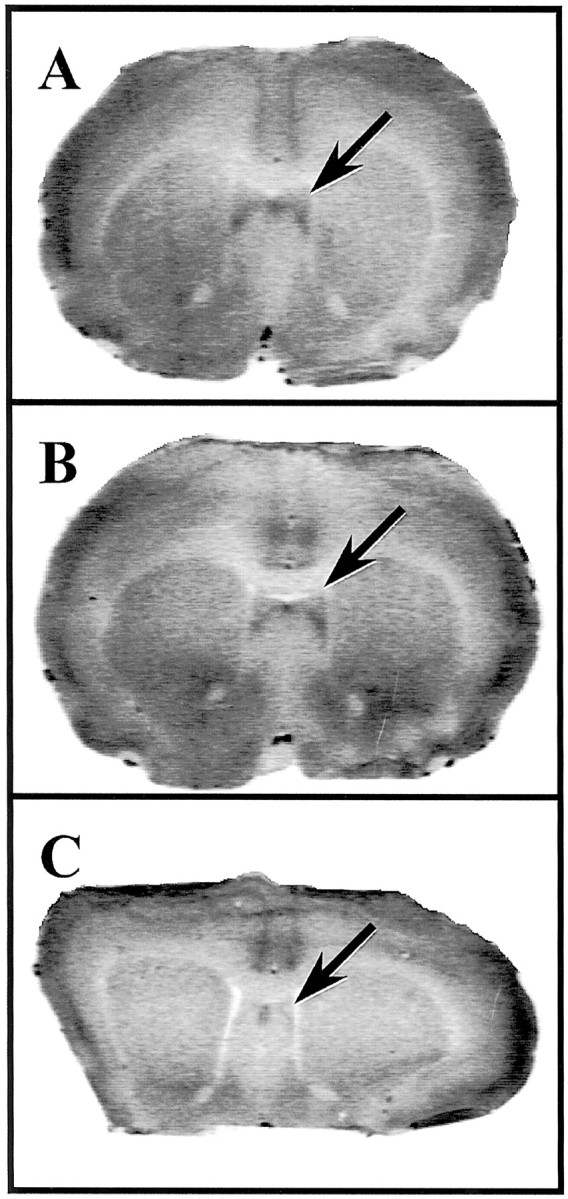

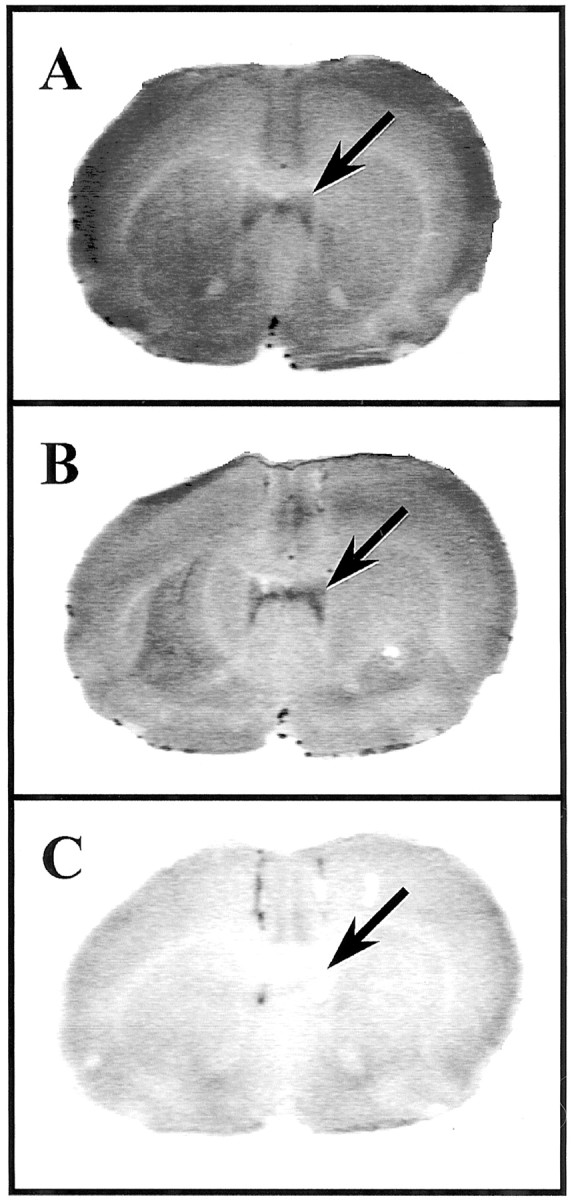

Effects of a selective CRH1 antagonist on shock-induced freezing. To determine the receptor subtype specificity of LS-mediated effects, the effects of intra-LS infusion of a selective CRH1 antagonist (NBI27914; CRH1:CRH2α affinity, >10,000; Chen et al., 1996) were measured. First, to identify a dose of NBI27914 that is sufficient to block shock-induced freezing after intracranial administration, several doses of the CRH1 antagonist were infused into the CeA, a structure that contains high levels of the CRH1receptor subtype and through which αhCRH reduces shock-induced freezing (Swiergiel et al., 1993). Thus, in experiment 10, rats received either vehicle (n = 6) or 0.2 μg (n = 6) or 1.0 μg (n = 7) of NBI27914 into CeA before testing in the freezing apparatus. Because the 1 μg dose was found to potently reduce shock-induced freezing, this dose was used for the LS experiment. Thus, in experiment 11, rats were given either vehicle (n = 7) or 1.0 μg of NBI27914 (n = 7) into the LS and were then placed in freezing chambers. At the end of the shock-induced freezing test in experiment 11, rats were immediately killed, and their brains were prepared for autoradiography of CRH receptors in the LS. In addition, a few rats that received 100 ng of αhCRH into the LS before testing in the freezing chamber (n = 5) were included in experiment 11 to compare brain sections from αhCRH-treated rats with those from NBI27914-treated rats in autoradiographic analyses. Because the behavioral data from these αhCRH-treated rats were identical to those from experiment 2, their freezing data are not displayed for the sake of brevity. Autoradiographic results from these animals are depicted in Figure 6.

Fig. 6.

Ex vivo autoradiography for CRH receptors after intra-lateral septum infusion of CRH receptor antagonists. Autoradiograms show representative coronal sections through the lateral septum from rats that had received vehicle (A), 1.0 μg/side NBI27914 (B), or 100 ng/side α-helical CRH (C) into lateral septum before killing. Note the high level of radioligand binding to CRH receptors in the lateral septum in sections from rats that were treated with either vehicle or NBI27914 and, in contrast, the absence of binding in sections from rats that had received α-helical CRH. Arrows indicate the location of [125I]sauvagine binding within the lateral septum.

Histology

At the end of the experiments (except experiments 8 and 11), rats were given an overdose of pentobarbital (130 mg/kg) and perfused transcardially with isotonic saline followed by 10% formalin. Brains were removed, stored in formalin, and subsequently sectioned into 60 μm coronal sections using a cryostat (Leica Instruments, Deerfield, IL). After staining with cresyl violet, sections were examined under a microscope for the location of injector tip placements. Animals whose injector placements fell outside of the targeted brain regions were excluded from analyses of behavioral data. At the time of histological verification of injector tip placements, the experimenter was blind to the pharmacological treatment as well as the behavioral data for each animal. For experiment 8, rats were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital and were then given a 5 μl infusion of Chicago blue dye (Sigma) through their ventricular cannulas. After a 3 min diffusion period, rats were decapitated, and brains were removed and sectioned into 2 mm slices. The appearance of dye within the ventricular system distal to the injection site was verified for each rat; rats without dye in their ventricles were excluded from analysis of behavioral data.

Autoradiography

For experiment 11, instead of perfusion, rats were killed by rapid decapitation immediately after they were tested in the freezing apparatus, and brains were quickly removed and frozen in chilled 2-methylbutane (−20 to −30°C). Brains were then mounted onto a cryostat block with Tissue-Tek (Hacker Instruments) and sectioned using a Leica cryostat. Twenty micrometer sections were thaw-mounted onto Fisher Scientific “plus-charged” slides, allowed to air dry, and stored at −80°C until use. On the day of assay, slides were thawed to room temperature and allowed to completely dry for a further 20 min. The area around each section was outlined using a grease marker, and 300 μl of [125I]sauvagine (50–100 pm final concentration in PBS containing 10 mmMgCl2 and 2 mm EGTA, pH 7.0) was gently applied directly onto each section. Nonspecific binding was determined in adjacent sections by the addition of 1 μmNBI27914, the selective CRH1 receptor antagonist with a Ki of 2 nm (Chen et al., 1996), for the determination of the CRH1-specific binding, or 1 μmd-Phe-CRH(12–41), which is an antagonist with equal affinity for the CRH1and CRH2 receptors (Ki, ∼30 nm), in the buffer for determination of both CRH1 and CRH2 receptor-specific binding. The slides were placed in a covered humidified chamber to reduce evaporation and incubated at 22°C for 40–45 min. After the incubation, the solution was gently aspirated from the section under vacuum, and the slides were washed using two 5 min dips in ice-cold PBS and Triton X-100 (0.01%), pH 7.0. Slides were then air-dried and apposed to Biomax MR x-ray film (Eastman Kodak Co., Rochester NY) for 4–5 d. Images were captured using a light box and digital camera (Northern Lights, St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada) and visualized using NIH Image (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). One set of adjacent sections from each animal was stained with cresyl violet and used to verify the location of injector tips in the LS.

Data analysis

For all freezing experiments, the interval (in seconds) between the final foot shock and the commencement of freezing (latency to freeze) and the total number of seconds the rat spent freezing during the 15 min test session were calculated for each animal. In the analgesia experiment, the number of seconds (of a maximum of 60) that it took for the rat to lick its hindpaws after being placed on the hot plate was measured for each rat. Because freezing and analgesia data were not normally distributed (there was an upper limit to the scores imposed by the length of the testing session), nonparametric statistics were used to analyze these measures instead of parametric tests. For all freezing data, separate Mann–Whitney U tests (vehicle group vs drug group) were performed for each experiment. In experiment 10, where multiple comparisons were made, the α level for statistical significance was adjusted to p < 0.02. Hot plate data were analyzed with a Wilcoxon matched pairs signed ranks test (vehicle vs drug treatment) because of the within-subjects design of this experiment. For locomotor activity data, the numbers of rears, ambulations (cage crossings), and total activity (total photo beam breaks) were calculated for each 10 min period of a 90 min test session. These data were analyzed with separate two-factor ANOVAs for each activity index, with drug treatment and time point as within-subjects factors.

RESULTS

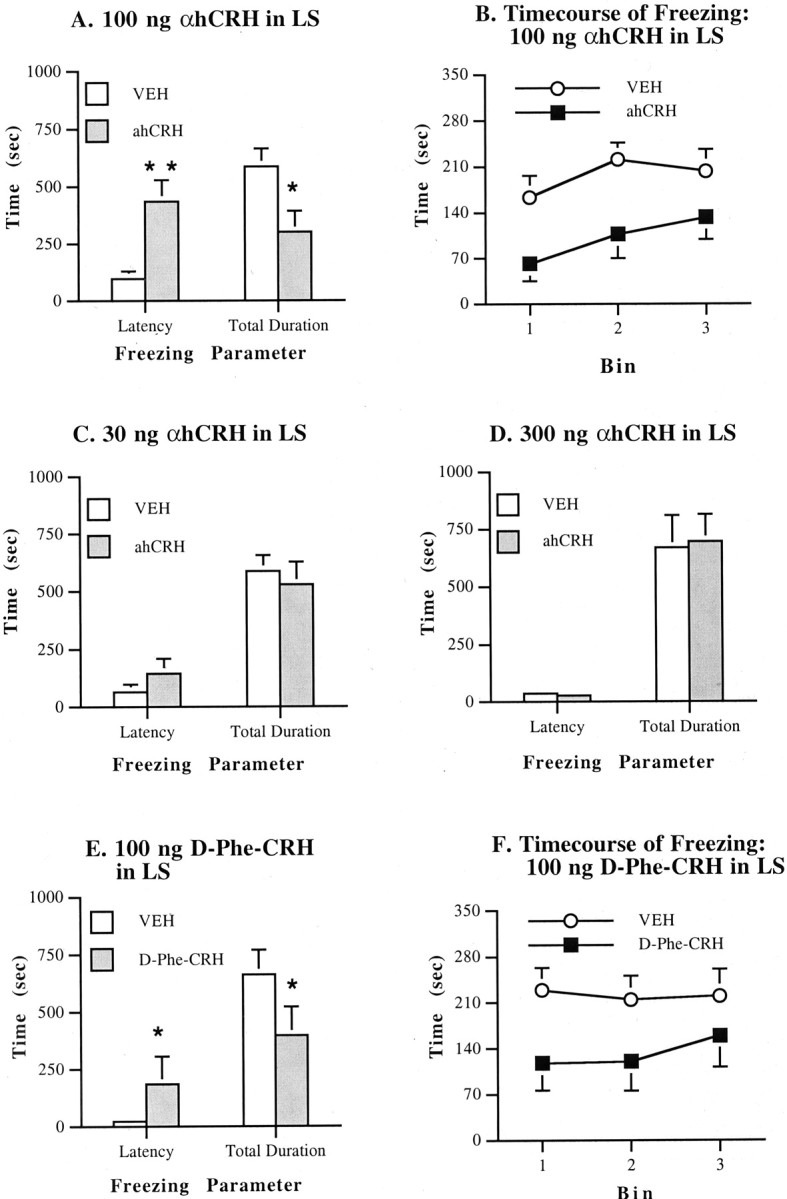

Effects on freezing of CRH1/CRH2receptor antagonist infusion into the LS

The results of experiment 1 are displayed in Figure1C. Infusion of 30 ng of αhCRH into the LS had no effect on either index of freezing behavior (latency to freeze, p = 0.427; total duration of freezing, p = 0.705, Mann–Whitney U test). In contrast, a higher dose of αhCRH (100 ng/side) significantly increased the latency to begin freezing (p < 0.004) and decreased the total duration of freezing (p < 0.018) after infusion into the LS (experiment 2, seen in Fig. 1A). Rats that received 100 ng of αhCRH took approximately three times as long to begin freezing and spent approximately half as much time freezing compared with vehicle-treated controls. As depicted in Figure1B, αhCRH decreased freezing in the first as well as the second and third portions of the test session, indicating that this reduction was not simply attributable to the antagonist-induced increase in the latency to begin freezing. Thus, infusion of 100 ng of αhCRH into the LS significantly reduced this measure of stress-induced behavior. Interestingly, infusion of a higher dose of αhCRH into the LS (experiment 3; 300 ng) failed to affect either the latency to freeze (p = 0.748) or the total duration of freezing (p = 0.521), indicating that αhCRH displays an inverted U-shaped dose–response profile for reducing shock-induced freezing in the LS (Fig. 1D). Finally, Figure 1E illustrates the results of experiment 4, which demonstrated that another more potent CRH1/CRH2 receptor antagonist,d-Phe-CRH(12–41), also increased the latency to freeze (p < 0.011) and decreased the total duration of freezing after infusion into the LS (p < 0.05). This reduction in freezing also occurred throughout the test session (Fig. 1F). It should be noted that this decrease in freezing was identical to that seen with αhCRH and that the latency and total freezing values in vehicle-treated rats in both experiments were similar. This similarity in profile between experiments 2 and 4 indicates that no effect on freezing latency or duration was produced by using a 1.0 versus a 1.5 mA shock intensity. These findings withd-Phe-CRH(12–41) confirm the results with αhCRH and furthermore indicate that behavioral effects of these antagonists in the LS cannot be attributed to indirect actions mediated through the CRH-binding protein, which binds with moderate affinity to αhCRH but has no affinity ford-Phe-CRH(12–41) (Chan et al., 2000).

Fig. 1.

Effects on freezing of α-helical CRH ord-Phe-CRH(12–41) infusion into the lateral septum. Values represent means ± SEM for each group.VEH, Vehicle (distilled water). All doses are in 0.5 μl/side. Bin, Each 5 min portion of the freezing test session. A, Effects of 100 ng of αhCRH on latency and total duration of freezing. B, Time course of freezing with 100 ng of αhCRH. C, Effects of 30 ng of αhCRH.D, Effects of 300 ng of αhCRH. E, Effects of 100 ng of d-Phe-CRH(12–41).F, Time course of freezing with 100 ng ofd-Phe-CRH(12–41). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared with VEHgroup.

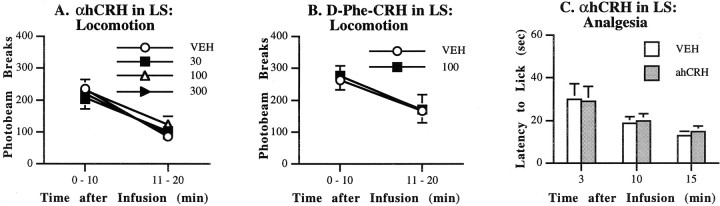

Effects on locomotor activity and analgesia of intra-LS αhCRH infusion

In contrast to the potent effects on shock-induced freezing behavior, αhCRH infusion into the LS produced no changes in locomotor activity (experiment 5). ANOVAs failed to indicate main effects of αhCRH on rearing [F(3,30) = 1.66; NS], ambulation [F(3,30) = 1.01; NS], or total activity [F(3,30) = 0.55; NS]. Moreover, no significant treatment × time interactions were seen. Because the effects were identical for all three indices of locomotor activity, only the data for total activity counts (total photo- beam breaks) are displayed (Fig.2A). Similarly, in experiment 6,d-Phe-CRH(12–41) failed to affect any index of locomotor activity; total activity counts are shown in Figure 2B[F(1,10) = 0.10; NS]. Analysis of data from experiment 7 indicated that pain thresholds were similarly unaffected by infusion of 100 ng of αhCRH into the LS (Fig.2C). A Wilcoxon signed ranks test revealed that the latency to lick hindpaws after being placed on the hot plate did not differ between the vehicle condition and the drug condition 3 min (p = 0.917), 10 min (p = 0.631), or 15 min (p = 0.464) after infusion, thereby mapping out the time course of the freezing test. Thus, intra-LS infusion of αhCRH had no effect on pain thresholds or locomotor activity at any time during the length of the freezing test session, suggesting that changes in shock-induced freezing that were produced by this treatment were not simply an artifact of altered sensitivity to the foot shock or altered baseline activity levels.

Fig. 2.

Effects on other behaviors of α-helical CRH ord-Phe-CRH(12–41) infusion into the lateral septum. Values represent means ± SEM for each group.VEH, Vehicle (distilled water). All doses are in nanograms per 0.5 μl/side. A, Effects of αhCRH on locomotor activity (total photobeam breaks in activity cages).B, Effects of d-Phe-CRH on locomotor activity. C, Effects of αhCRH on pain sensitivity (latency to lick hindpaws in the hotplate test).

Effects on freezing of αhCRH infusion into sites adjacent to the LS

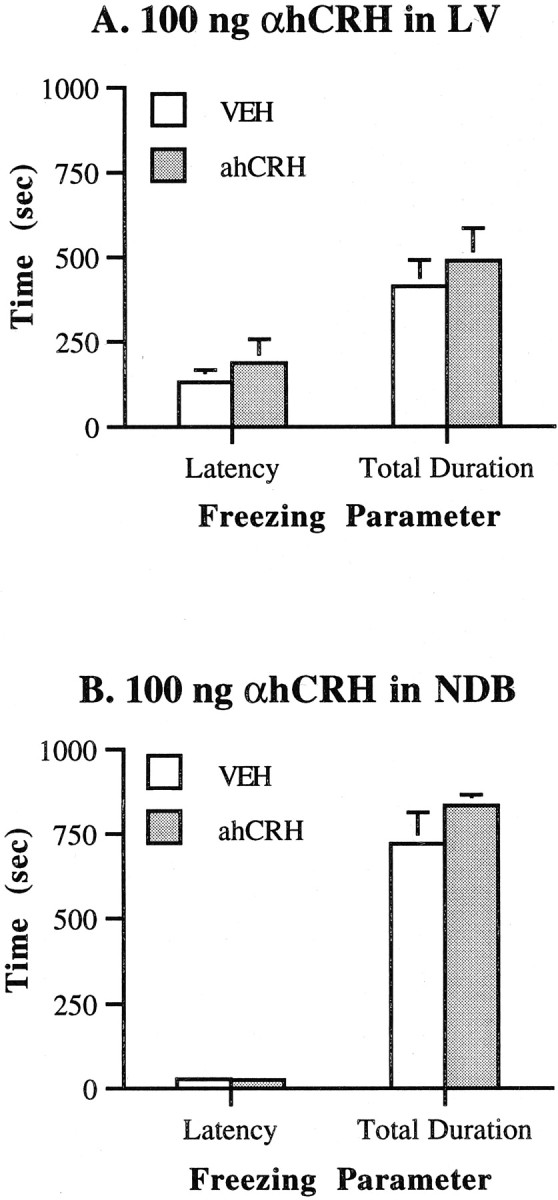

Figure 3 depicts the effects on shock-induced freezing of 100 ng of αhCRH infusion into either the LV or the NDB. Mann–Whitney U tests indicated that for the LV, αhCRH-treated rats performed no differently from vehicle-treated rats on either the latency to begin freezing (p = 0.965) or the total duration of freezing (p = 0.453) (experiment 8, seen in Fig. 3A). Likewise, it is shown in Figure 3B that infusion of αhCRH into the NDB (experiment 9) had no effect on either measure of freezing (p = 0.894 for latency, and p = 0.248 for total duration). Thus, although this dose of αhCRH markedly reduced freezing on intra-LS infusion, it had no effect on shock-induced freezing when delivered into regions that are adjacent to the LS, suggesting that the effects of αhCRH after intra-LS infusion were not mediated by actions at other adjacent brain regions.

Fig. 3.

Effects on freezing of α-helical CRH infusion into regions adjacent to the lateral septum. Values represent means ± SEM for each group. VEH, Vehicle (distilled water); αhCRH is 100 ng/0.5 μl per side.A, Infusion into the lateral ventricle.B, Infusion into the nucleus of the horizontal limb of the diagonal band.

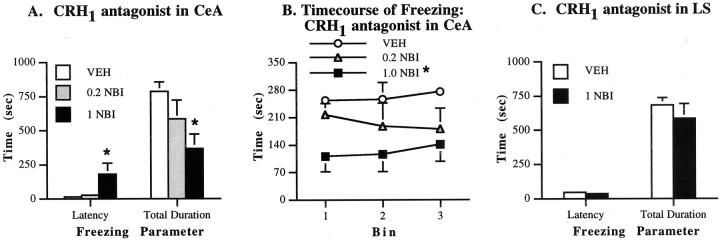

Effects of a selective CRH1 receptor antagonist on freezing

The effects on freezing of NBI27914 (a selective CRH1 antagonist) administration into the CeA were investigated in experiment 10 (Fig.4A). It was found that the 1.0 μg dose (p = 0.015) but not the 0.2 μg dose (p = 0.037) significantly increased the latency to begin freezing after NBI27914 infusion into the CeA. The high (p = 0.010) but not the low (p = 0.150) dose of NBI27914 also decreased the total duration of freezing after intra-CeA infusion; freezing was reduced throughout the test (Fig. 4B). Thus, infusion of a highly selective CRH1 antagonist into the CeA profoundly reduced shock-induced freezing, suggesting that within this structure, the CRH1 receptor subtype at least in part mediates stress-induced behavioral responses. In contrast, when infused into the LS, NBI27914 had no effect on the latency to begin freezing (p = 0.338) or the total duration of freezing (p = 0.655) (experiment 11; Fig. 4C). Thus, a dose of a CRH1 receptor antagonist that markedly reduced freezing on intra-CeA infusion failed to alter this behavior when infused into the LS.

Fig. 4.

Effects on freezing of a selective CRH1 receptor antagonist. Values represent means ± SEM for each group. VEH, Vehicle solution;NBI, NBI27914. Doses are in micrograms per 0.5 μl/side. A, Effects on latency and total duration of freezing after infusions into the central nucleus of the amygdala.B, Time course of freezing with NBI27914 infusion into the CeA. C, Effects of infusions into the lateral septum. *p < 0.02 compared with VEHgroup.

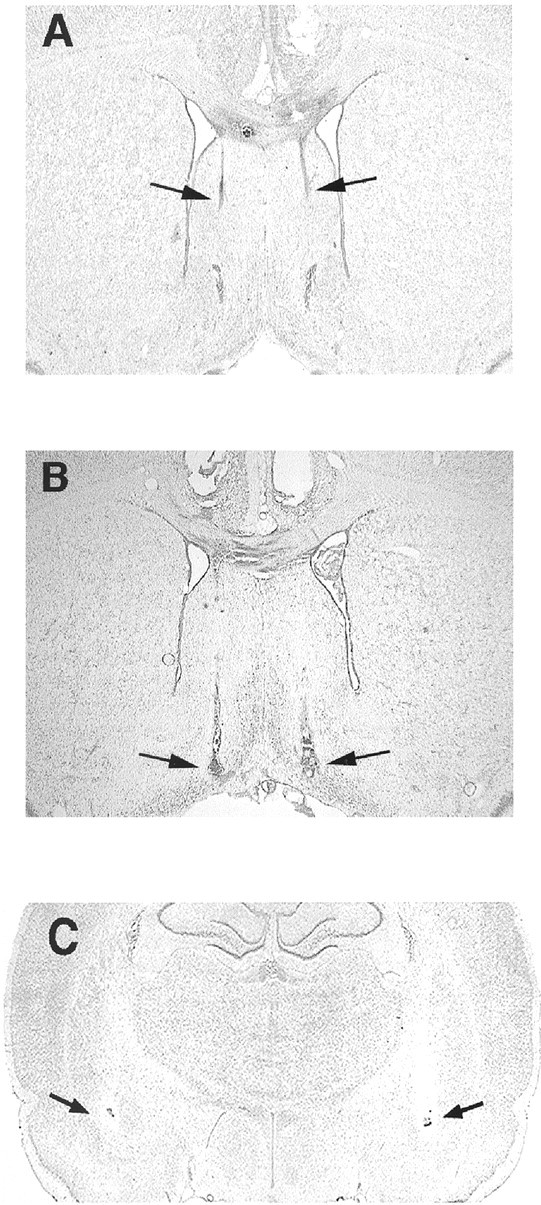

Histological analysis

Figure 5 displays the location of injector tips in the various brain regions that were studied. Injector tips for all animals except two in the LS experiments, one in the NDB experiment, and one in the CeA experiment were found to be within the targeted regions. Data from these anatomical outliers were excluded from statistical analysis; the sample sizes reported in Materials and Methods reflect the omission of these rats. The photomicrographs in Figure 5 depict a section from each brain region under investigation; the location of injector tips in these images is representative of placements within that region. As can be seen in Figure 5, excessive tissue damage was not observed with infusion into any region.

Fig. 5.

Histological verification of injector tip placements. Photomicrographs show Nissl-stained coronal sections through the lateral septum (A), the nucleus of the horizontal limb of the diagonal band (B), and the central nucleus of the amygdala (C).Black arrows indicate the location of injector tips. Sections illustrate representative injector tip placements for each region. Note the absence of necrosis or lesioning at the injection sites after infusions.

Autoradiography for CRH receptors in the LS

Ex vivo receptor autoradiography was used as described above for assessing [125I]sauvagine binding in brain sections from animals that had received either vehicle or CRH receptor antagonists into the LS. This analytical technique was used to provide a qualitative assessment of relative levels of [125I]sauvagine binding in sections from different treatment groups. It should be noted that although there is some unavoidable variability in the precise rostral–caudal location of the selected sections, these differences are small (∼100 μm), and that CRH2α receptors are distributed homogeneously throughout the entire extent of the LS (Chalmers et al., 1995). Thus, the sections displayed in the following figures provide a representative example of receptor labeling within this structure after various CRH antagonist treatments.

Figure 6 displays representative sections from rats that were given vehicle (Fig. 6A), 1 μg of NBI27914 (Fig. 6B), or 100 ng of αhCRH (Fig.6C) directly into the LS before behavioral testing. The binding of [125I]Tyr0sauvagine to CRH receptors in the LS was nearly undetectable in rats that had received the nonselective antagonist αhCRH into this region (Fig. 6C). As can be seen clearly in Figure6B, there was no inhibition of [125I]sauvagine binding in the LS in animals that had received intra-LS NBI27914; the level of binding in NBI27914-treated rats was equivalent to that observed in vehicle-treated rats (Fig. 6A). Thus, the observation that a mixed CRH1/CRH2(αhCRH) antagonist prevented radioligand binding in the LS but a selective CRH1 antagonist did not suggests that the CRH receptor to which the infused αhCRH is binding is of the CRH2α subtype.

Figure 7 demonstrates the pattern of binding of [125I]sauvagine to CRH receptors in representative sections from rats treated with vehicle in the LS. These were consecutive sections from the same animal. Sections were incubated with [125I]Tyr0sauvagine in the absence of antagonists (Fig. 7A) or the presence of 1 μm NBI27914 (Fig. 7B) or 1 μmd-Phe-CRH(12–41) (Fig.7C). In the presence of 1 μmNBI27914, [125I]sauvagine binding was inhibited from CRH1 receptors in the cortex, with no observable inhibition of binding to CRH2receptors in the LS (arrows). In contrast, in the presence of d-Phe-CRH(12–41), the nonselective CRH1/CRH2antagonist, radioligand binding was virtually abolished in both the cortical and septal areas (Fig. 7C). Note the faint intensity of the radioactive signal in Figure 7C; areas that appear light or white indicate that little or no [125I]Tyr0sauvagine bound to this section, suggesting that incubation with the unlabeled d-Phe-CRH(12–41)caused nearly all CRH receptors to become occupied and therefore unavailable for [125I]Tyr0sauvagine binding. These results confirm that the identity of CRH receptors within the LS is of the CRH2 but not the CRH1 receptor subtype. These data are consistent with previous reports indicating that there is a high density of CRH2α receptors in the LS, but that this structure is devoid of CRH1 receptors (Chalmers et al., 1995; Primus et al., 1997). Taken together, these findings indicate that the behavioral actions of intra-LS αhCRH infusion are likely mediated through CRH2α and not CRH1 receptors.

Fig. 7.

In vitro autoradiography for CRH receptors in the lateral septum. Autoradiograms show representative coronal sections through the lateral septum from rats that had received intra-lateral septum infusion of vehicle before killing.A, Total binding of the CRH1/CRH2 radioligand [125I]sauvagine. B, [125I]Sauvagine binding in the presence of excess unlabeled NBI27914. C, [125I]Sauvagine binding in the presence of excess unlabeled CRH1/CRH2 receptor antagonistd-Phe-CRH(12–41). Note the high intensity of signal in the lateral septum in sections that were incubated with NBI27914 but the absence of signal in sections incubated with the CRH1/CRH2 antagonistd-Phe-CRH(12–41). The light appearance of C indicates that [125I]sauvagine binding was virtually absent in this section. Arrows indicate the location of [125I]sauvagine binding within the lateral septum.

DISCUSSION

In the present studies, microinfusion of the CRH1/CRH2 receptor antagonist αhCRH into the LS decreased shock-induced freezing, a measure of stress-induced behavior, without affecting general activity levels or pain sensitivity. The same dose that decreased freezing on intra-LS infusion had no effect after infusion into neighboring regions such as the LV or NDB. An identical pattern of results was obtained with the more potent CRH1/CRH2 receptor antagonist d-Phe-CRH(12–41). In contrast, a highly selective CRH1 receptor antagonist that reduced freezing after intra-CeA infusion failed to affect freezing when infused into the LS. Moreover, intra-LS administration of the CRH1-selective antagonist did not affect ex vivo binding of [125I]sauvagine to CRH receptors in the LS. Infusion of αhCRH into this region, however, completely prevented [125I]sauvagine binding in the LS.In vitro studies demonstrated that [125I]sauvagine binding in the LS was not affected after incubating sections with excess CRH1 antagonist but was abolished after incubating sections with excess CRH1/CRH2 receptor antagonist. These results confirm that on intra-LS infusion, the actions of αhCRH on freezing can be attributed to the interaction of this antagonist with the CRH2α receptor. Taken together, these findings indicate that blockade of CRH2α but not CRH1receptors within the LS decreases stress-induced behavior. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to show that the acute and selective antagonism of CRH2α receptors reduces stress-induced defensive behavior.

The behavioral specificity of the CRH antagonist-induced reduction in freezing is supported by the finding that locomotor activity (irrespective of whether rats were previously habituated to the testing chambers) and pain sensitivity (regardless of the postinfusion time point for testing) were not affected by αhCRH ord-Phe-CRH(12–41). The finding that a separate CRH receptor antagonist,d-Phe-CRH(12–41), produced the exact same behavioral profile as αhCRH provides independent corroboration for the notion that blockade of CRH receptors within the LS causes a reduction specifically in stress-like behavior. CRH receptor blockade caused an increase in the latency to begin freezing and a decrease in the duration of freezing at each time point of the test, indicating that this reduction in stress-induced freezing was long-lasting and occurred throughout the entire extent of the test session. The finding that a selective CRH1 antagonist blocked freezing when infused into the CeA but failed to alter freezing after intra-LS infusion provides novel and clear evidence (in conjunction with the autoradiographic findings) that within the LS, it is the antagonism of specifically the CRH2α receptor subtype that reduces stress-induced behavior.

The present studies thus indicate that the LS is an important site for the regulation of stress-induced freezing. The finding that 100 ng of αhCRH reduced freezing on intra-LS infusion but failed to alter this behavior after intracerebroventricular administration is particularly striking, given that the lateral ventricle borders the LS. Our previous work indicates that 25 μg of this antagonist is required to reduce shock-induced freezing via intracerebroventricular administration (Kalin et al., 1988). Thus, the failure of 100 ng of αhCRH to reduce freezing after intracerebroventricular administration likely indicates that αhCRH-induced effects observed in LS-treated rats were highly anatomically specific to the LS and did not arise from diffusion of the antagonist into the ventricle or other brain regions. One interesting feature of the αhCRH dose–response profile was its inverted U shape with regard to freezing; a middle dose but neither a low nor high dose reduced this stress-induced behavior after infusion into the LS. Although the specific mechanisms underlying this profile remain to be determined, it should be noted that an identical dose–response profile for αhCRH on shock-induced freezing has been observed previously for the CeA (Swiergiel et al., 1993).

The present findings extend previous reports indicating that αhCRH infusion into locus ceruleus or CeA decreases shock-induced freezing behavior (Swiergiel et al., 1992, 1993). CRH receptor antagonism within the CeA also prevents behaviors induced by a variety of other different stressors (Heinrichs et al., 1992; Rassnick et al., 1993). The present results further these findings by indicating that within the CeA, the reduction of stress-induced behavior is likely mediated through blockade of the CRH1 receptor subtype. Moreover, the present findings suggest that decreases in stress-induced behaviors after CRH1 receptor knock-out or systemic CRH1 receptor antagonist administration may involve the CeA (Smith et al., 1998; Timpl et al., 1998; Contarino et al., 1999; Okuyama et al., 1999; Habib et al., 2000). It is thus possible that the recently described clinical efficacy of CRH1 receptor antagonists in depression (Zobel et al., 2000) involves the blockade of CRH1receptors within the CeA. To the best of our knowledge, the present report is the first to identify the specific neuroanatomical substrates through which the different CRH receptor subtypes regulate defensive freezing.

It could be argued that the decreased freezing seen after intra-LS αhCRH infusion may result from diffusion of the drug into the medial septum (MS), a structure devoid of CRH2αreceptors but enriched in CRH1 receptors (Chalmers et al., 1995). This possibility is unlikely, however, given that intra-LS NBI27914 infusion (which could diffuse to the MS and block CRH1 receptors) and intra-NDB αhCRH infusion (which would be equally likely to diffuse to the MS as would intra-LS αhCRH) failed to alter shock-induced freezing. Thus, it seems that although both CRH1 and CRH2α receptors regulate stress-induced behaviors, they act through different brain regions. The present findings are in agreement with a previous report in which intra-LS administration of a putative CRH2-preferring antagonist [anti-sauvagine-30 (AS30)] was found to reverse stress- or CRH-induced decreases in open arm entries in an elevated plus- maze in mice (Ruhmann et al., 1998; Radulovic et al., 1999). High doses of AS30 have also been reported to decrease freezing behavior after intracerebroventricular infusion (Takahashi et al., 2001), further corroborating the findings of the present study, yet there are conflicting reports about the CRH2 selectivity of AS30 (Ruhmann et al., 1998; Higelin et al., 2001). The present studies therefore clarify these previous behavioral findings by systematically demonstrating that reductions in stress-induced behavior caused by CRH antagonist administration into the LS are attributable to the CRH2α and not the CRH1receptor. Furthermore, the present findings indicate that these two receptor subtypes may regulate stress-induced behavior through different anatomical sites.

In contrast to the findings with acute CRH2αreceptor antagonism, CRH2α knock-out mice exhibit higher levels of stress-induced behaviors than wild-type controls, although this profile is not consistent across behavioral paradigms or across different laboratories (Bale et al., 2000; Coste et al., 2000; Kishimoto et al., 2000). A major difficulty in interpreting the results of constitutive gene knock-out studies is that the animal matures without the gene of interest and can develop compensatory alterations that contribute to the final behavioral phenotype (Picciotto and Wickman, 1998; Gingrich and Hen, 2000). Thus, the stress-like behavioral phenotype observed in the CRH2α knock-out mice might not derive directly from the absence of the CRH2α receptor but rather may be caused through indirect compensatory alterations in the CRH and other systems. Increased gene expression of CRH (in the CeA) and the CRH-like ligand urocortin has been reported in CRH2α knock-out mice (Bale et al., 2000; Coste et al., 2000). Urocortin decreases feeding and increases stress-like responding in certain approach–avoidance-based behavioral tests (Spina et al., 1996; Moreau et al., 1997; Jones et al., 1998; Cullen et al., 2001). Likewise, the present findings indicate that stimulation of CRH1 receptors in the CeA would increase stress-like responses. The very novel discovery of CRH2-selective members of the CRH family of endogenous ligands (urocortin II, urocortin III, and stresscopin) offers an even more complex picture of the potential compensatory effects within this system (Hsu and Hsueh, 2001; Lewis et al., 2001; Reyes et al., 2001). Thus, increases in these ligands in response to constitutive CRH2α gene deletion could underlie the putative stress-like phenotype of the CRH2α knock-out mice. Future studies using novel gene-targeting approaches such as virally mediated gene transfer or inducible knock-out techniques (Stark et al., 1998; Simonato et al., 2000) will aid in clarifying the contributions of developmental factors to the phenotype produced by CRH2α receptor knock-out.

One previous report indicates that subchronic exposure to benzodiazepines decreased CRH1 receptor levels but increased CRH2α receptor levels in rat brain, indicating that CRH1 and CRH2α receptors may act in an opposing manner (Skelton et al., 2000). It has been suggested that CRH2α receptors are involved in “coping” with stress rather than in the direct behavioral response to stress, which is hypothesized to be mediated by CRH1receptors (Liebsch et al., 1999). The present results, however, indicate that CRH1 and CRH2α receptors play similar or parallel roles in the regulation of stress-related behavior, and that this regulation may occur through different brain regions. It may be that the CRH receptor subtypes are differentially affected by long-term drug treatment but that their roles in mediating acute stress-induced behavioral effects are similar.

The present finding that acute blockade of CRH2α receptors within the LS decreases stress-induced freezing is not surprising if one considers the electrophysiological role of CRH in the LS and the role of the LS in regulating defensive behaviors. Single-unit recordings from the LS indicate that within this structure, CRH is inhibitory (Siggins et al., 1985); the LS is thought to provide a tonic inhibition over the expression of defensive behaviors (Albert and Walsh, 1982, 1984;Graeff, 1994). Thus, stimulation of CRH receptors within the LS (perhaps through stress-induced CRH or urocortin release) might be expected to disinhibit defensive behaviors such as freezing. Antagonism of these receptors would prevent this disinhibition and would maintain the tonic inhibition over defensive behaviors, thereby reducing the expression of freezing.

The precise circuitry through which CRH1 and CRH2α receptors interact to control stress-related behaviors remains to be determined. The LS is important in modulating defensive behaviors (Graeff, 1994), and the CeA regulates the expression of fear-related responses (Davis and Shi, 1999). The present studies indicate that antagonism of CRH2α receptors within the LS or CRH1 receptors within the CeA decreases the expression of fear-induced defensive behavior. In rats, both the LS and CeA receive CRH- or urocortin-containing terminals (Swanson et al., 1983; Sakanaka et al., 1988; Kozicz et al., 1998; Bittencourt et al., 1999). In addition, anatomical tract-tracing studies indicate reciprocal connections between these two structures (Risold and Swanson, 1997) and also indicate that both structures project to the periaqueductal gray (PAG; Rizvi et al., 1991; Risold and Swanson, 1997), a midbrain structure that, when stimulated, elicits defensive behaviors such as freezing (Bandler et al., 1985; Behbehani, 1995). Because stress-induced freezing is a defensive behavior necessary for an organism's survival, it may be adaptive to have parallel systems involving the two CRH receptor subtypes that can either independently or interactively modulate the expression of this critical form of behavioral inhibition. It is possible that information from the CRH2α–LS system and the CRH1–CeA system converges within the PAG to regulate the expression of freezing. Although further studies must be performed to test this hypothesis, the present findings provide a valuable starting point for identifying the specific role of CRH receptor subtypes in the neuroanatomical circuitry subserving stress-related defensive behaviors.

Because increased CRH activity has been hypothesized to play a role in mediating anxiety and depressive disorders, there has been much emphasis on developing new antidepressant or anxiolytic drugs that antagonize CRH receptors (McCarthy et al., 1999). CRH1 receptor antagonists have shown some preliminary success in an open-label clinical trial as a novel class of antidepressants (Zobel et al., 2000). Anxiety disorders and depression have been conceptualized as an aberrant manifestation of adaptive stress- or fear-related defensive behaviors (Bakshi and Kalin, 2002). The present results indicate that acute antagonism of CRH2α receptors reduces stress-induced defensive behavior. This receptor subtype may thus play an important role in mediating aberrant expressions of fear-related responses that become dysregulated in stress-related disorders such as anxiety or depression. Thus, in addition to the CRH1receptor, attention should also be focused on the development of nonpeptide CRH2α receptor antagonists, which could be useful as therapeutic agents for stress-related psychopathology.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant MH-40855 (N.H.K.), the HealthEmotions Research Institute, and Meriter Hospital. V.P.B. was supported by NIH Grant MH-12360. We thank Dr. Brian Baldo for thoughtful comments on the project and this manuscript.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Vaishali P. Bakshi, Department of Psychiatry, University of Wisconsin, 6001 Research Park Boulevard, Madison, WI 53719. E-mail: vbakshi@facstaff.wisc.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albert DJ, Walsh ML. The inhibitory modulation of agonistic behavior in the rat brain: a review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1982;6:125–143. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(82)90051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albert DJ, Walsh ML. Neural systems and the inhibitory modulation of agonistic behavior: a comparison of mammalian species. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1984;8:5–24. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(84)90017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakshi VP, Kalin NH. Animal models and endophenotypes of anxiety and stress disorders. In: Davis KL, Charney D, Coyle JT, Nemeroff C, editors. Neuropsychopharmacology: the 5th generation of progress. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; New York: 2002. pp. 883–900. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bale TL, Contarino A, Smith GW, Chan R, Gold LH, Sawchenko PE, Koob GF, Vale WV, Lee KF. Mice deficient for corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor-2 display anxiety-like behaviour are hypersensitive to stress. Nat Genet. 2000;24:410–414. doi: 10.1038/74263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bandler R, Depaulis A, Vergnes M. Identification of midbrain neurones mediating defensive behavior in the rat by microinjections of excitatory amino acids. Behav Brain Res. 1985;15:107–119. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(85)90058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behbehani MM. Functional characteristics of the midbrain periaqueductal gray. Prog Neurobiol. 1995;46:575–605. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(95)00009-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bittencourt JC, Vaughan J, Arias C, Rissman RA, Vale WW, Sawchenko PE. Urocortin expression in rat brain: evidence against a pervasive relationship of urocortin-containing projections with targets bearing type 2 CRH receptors. J Comp Neurol. 1999;415:285–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chalmers DT, Lovenberg TW, De Souza EB. Localization of novel corticotropin-releasing factor receptor (CRH2) mRNA expression to specific subcortical nuclei in rat brain: comparison with CRH1 receptor mRNA expression. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6340–6350. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06340.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan RK, Vale WW, Sawchenko PE. Paradoxical activational effects of a corticotropin-releasing factor-binding protein “ligand inhibitor” in rat brain. Neuroscience. 2000;101:115–129. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen C, Dagnino R, Jr, De Souza EB, Grigoriadis DE, Huang CQ, Kim KI, Liu Z, Moran T, Webb TR, Whitten JP, Xie YF, McCarthy JR. Design and synthesis of a series of non-peptide high-affinity human corticotropin-releasing factor1 receptor antagonists. J Med Chem. 1996;39:4358–4360. doi: 10.1021/jm960149e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Contarino A, Dellu F, Koob GF, Smith GW, Lee KF, Vale W, Gold LH. Reduced anxiety-like and cognitive performance in mice lacking the corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 1. Brain Res. 1999;835:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01158-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coste SC, Kesterson RA, Heldwein KA, Stevens SL, Heard AD, Hollis JH, Murray SE, Hill JK, Pantely GA, Hohimer AR, Hatton DC, Phillips TJ, Finn DA, Low MJ, Rittenberg MB, Stenzel P, Stenzel-Poore MP. Abnormal adaptations to stress and impaired cardiovascular function in mice lacking corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor-2. Nat Genet. 2000;24:403–409. doi: 10.1038/74255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cullen MJ, Ling N, Foster AC, Pelleymounter MA. Urocortin, corticotropin releasing factor-2 receptors and energy balance. Endocrinology. 2001;142:992–999. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.3.7989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis M, Shi C. The extended amygdala: are the central nucleus of the amygdala and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis differentially involved in fear versus anxiety? Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;877:281–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gingrich JA, Hen R. The broken mouse: the role of development, plasticity and environment in the interpretation of phenotypic changes in knockout mice. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10:146–152. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)00061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graeff FG. Neuroanatomy and neurotransmitter regulation of defensive behaviors and related emotions in mammals. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1994;27:811–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Habib KE, Weld KP, Rice KC, Pushkas J, Champoux M, Listwak S, Webster EL, Atkinson AJ, Schulkin J, Contoreggi C, Chrousos GP, McCann SM, Suomi SJ, Higley JD, Gold PW. Oral administration of a corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor antagonist significantly attenuates behavioral, neuroendocrine, and autonomic responses to stress in primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6079–6084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.6079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heinrichs SC, Pich EM, Miczek KA, Britton KT, Koob GF. Corticotropin-releasing factor antagonist reduces emotionality in socially defeated rats via direct neurotropic action. Brain Res. 1992;581:190–197. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90708-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinrichs SC, Lapsansky J, Lovenberg TW, De Souza EB, Chalmers DT. Corticotropin-releasing factor CRH1, but not CRH2, receptors mediate anxiogenic-like behavior. Regul Peptides. 1997;71:15–21. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(97)01005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higelin J, Py-Lang G, Paternoster C, Ellis GJ, Patel A, Dautzenberg FM. 125I-Antisauvagine-30: a novel, specific high-affinity radioligand for the characterization of corticotropin-releasing factor type 2 receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40:114–122. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsu SY, Hsueh AJ. Human stresscopin and stresscopin-related peptide are selective ligands for the type 2 corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor. Nat Med. 2001;7:605–611. doi: 10.1038/87936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones DN, Kortekaas R, Slade PD, Middlemiss DN, Hagan JJ. The behavioural effects of corticotropin-releasing factor-related peptides in rats. Psychopharmacology. 1998;138:124–132. doi: 10.1007/s002130050654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalin NH, Sherman JE, Takahashi LK. Antagonism of endogenous CRH systems attenuates stress-induced freezing behavior in rats. Brain Res. 1988;457:130–135. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kishimoto T, Radulovic J, Radulovic M, Lin CR, Schrick C, Hooshmand F. Deletion of Crhr2 reveals an anxiolytic role for corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor-2. Nat Genet. 2000;24:415–419. doi: 10.1038/74271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koob GF, Heinrichs SC. A role for corticotropin releasing factor and urocortin in behavioral responses to stressors. Brain Res. 1999;848:141–152. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01991-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kozicz T, Yanaihara H, Arimura A. Distribution of urocortin-like immunoreactivity in the central nervous system of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1998;391:1–10. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980202)391:1<1::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee EH. Corticotropin-releasing factor injected into the lateral septum improves memory function in rats. Chin J Physiol. 1995;38:125–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis K, Li C, Perrin MH, Blount A, Kunitake K, Donaldson C, Vaughan J, Reyes TM, Gulyas J, Fischer W, Bilezikjian L, Rivier J, Sawchenko PE, Vale WW. Identification of urocortin III, an additional member of the corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) family with high affinity for the CRF-2 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:7570–7575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121165198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liebsch G, Landgraf R, Engelmann M, Lorscher P, Holsboer F. Differential behavioural effects of chronic infusion of CRH1 and CRH2 receptor antisense oligonucleotides into the rat brain. J Psychiatr Res. 1999;33:153–163. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(98)80047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCarthy J, Heinrichs SC, Grigoriadis DE. Recent advances with the CRH1 receptor: design of small molecule inhibitors, receptor subtypes and clinical indications. Curr Pharmaceutical Design. 1999;5:289–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Menzaghi F, Howard RL, Heinrichs SC, Vale W, Rivier J, Koob GF. Characterization of a novel and potent corticotropin-releasing factor antagonist in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;269:564–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitchell AJ. The role of corticotropin-releasing factor in depressive illness: a critical review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1998;22:635–651. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(97)00059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moreau JL, Kilpatrick G, Jenck F. Urocortin, a novel neuropeptide with anxiogenic-like properties. NeuroReport. 1997;8:1697–1701. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199705060-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nemeroff CB, Widerlov E, Bissette G, Walleus H, Karlsson I, Eklund K, Kilts CD, Loosen PT, Vale W. Elevated concentrations of CSF corticotropin-releasing factor-like immunoreactivity in depressed patients. Science. 1984;226:1342–1344. doi: 10.1126/science.6334362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okuyama S, Chaki S, Kawashima N, Suzuki Y, Ogawa SI, Nakazato A, Kumagai T, Okubo T, Tomisawa K. Receptor binding, behavioral, and electrophysiological profiles of nonpeptide corticotropin-releasing factor subtype 1 receptor antagonists CRA1000 and CRA1001. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:926–993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic; San Diego: 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perrin MH, Vale WW. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptors and their ligand family. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;885:312–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Picciotto MR, Wickman K. Using knockout and transgenic mice to study neurophysiology and behavior. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:1131–1163. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.4.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Primus RJ, Yevich E, Baltazar C, Gallager DW. Autoradiographic localization of CRH1 and CRH2 binding sites in adult rat brain. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1997;17:308–316. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Radulovic J, Ruhmann A, Liepold T, Spiess J. Modulation of learning and anxiety by corticotropin-releasing factor (CRH) and stress: differential roles of CRH receptors 1 and 2. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5016–5025. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-12-05016.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rassnick S, Heinrichs SC, Britton KT, Koob GF. Microinjection of a corticotropin-releasing factor antagonist into the central nucleus of the amygdala reverses anxiogenic-like effects of ethanol withdrawal. Brain Res. 1993;605:25–32. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91352-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reyes TM, Lewis K, Perrin MH, Kunitake KS, Vaughan J, Arias CA, Hogenesch JB, Gulyas J, Rivier J, Vale WW, Sawchenko PE. Urocortin II: a member of the corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) neuropeptide family that is selectively bound by type 2 CRF receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2843–2848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051626398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Risold PY, Swanson LW. Connections of the rat lateral septal complex. Brain Res Rev. 1997;24:115–195. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rizvi TA, Ennis M, Behbehani MM, Shipley MT. Connections between the central nucleus of the amygdala and the midbrain periaqueductal gray: topography and reciprocity. J Comp Neurol. 1991;303:121–131. doi: 10.1002/cne.903030111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruhmann A, Bonk I, Lin CR, Rosenfeld MG, Spiess J. Structural requirements for peptidic antagonists of the corticotropin-releasing factor receptor (CRFR): development of CRFR2beta-selective antisauvagine-30. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15264–15269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sakanaka M, Magari S, Shibasaki T, Lederis K. Corticotropin-releasing factor-containing afferents to the lateral septum of the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1988;270:404–415. doi: 10.1002/cne.902700309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siggins GR, Gruol D, Aldenhoff J, Pittman Q. Electrophysiological actions of corticotropin-releasing factor in the central nervous system. Fed Proc. 1985;44:237–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simonato M, Manservigi R, Marconi P, Glorioso J. Gene transfer into neurones for the molecular analysis of behaviour: focus on herpes simplex vectors. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:183–190. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01539-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Skelton KH, Nemeroff CB, Knight DL, Owens MJ. Chronic administration of the triazolobenzodiazepine alprazolam produces opposite effects on corticotropin-releasing factor and urocortin neuronal systems. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1240–1248. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-03-01240.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith GW, Aubry JM, Dellu F, Contarino A, Bilezikjian LM, Gold LH, Chen R, Marchuk Y, Hauser C, Bentley CA, Sawchenko PE, Koob GF, Vale W, Lee KF. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 1-deficient mice display decreased anxiety, impaired stress response, and aberrant neuroendocrine development. Neuron. 1998;20:1093–1102. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80491-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spina M, Merlo-Pich E, Chan RK, Basso AM, Rivier J, Vale W, Koob GF. Appetite-suppressing effects of urocortin, a CRH-related neuropeptide. Science. 1996;273:1561–1564. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5281.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stark KL, Oosting RS, Hen R. Inducible knockout strategies to probe functions of 5-HT receptors. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1998;861:57–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Swanson LW, Sawchenko PE, Rivier J, Vale WW. Organization of ovine corticotropin-releasing factor immunoreactive cells and fibers in the rat brain: an immunohistochemical study. Neuroendocrinology. 1983;36:165–186. doi: 10.1159/000123454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Swiergiel AH, Takahashi LK, Rubin WW, Kalin NH. Antagonism of corticotropin-releasing factor receptors in the locus coeruleus attenuates shock-induced freezing in rats. Brain Res. 1992;587:263–268. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91006-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Swiergiel AH, Takahashi LK, Kalin NH. Attenuation of stress-induced behavior by antagonism of corticotropin-releasing factor receptors in the central amygdala in the rat. Brain Res. 1993;623:229–234. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91432-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takahashi LK, Ho SP, Livanov V, Graciani N, Arneric SP. Antagonism of CRF(2) receptors produces anxiolytic behavior in animal models of anxiety. Brain Res. 2001;902:135–142. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02405-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Timpl P, Spanagel R, Sillaber I, Kresse A, Reul JM, Stalla GK, Blanquet V, Steckler T, Holsboer F, Wurst W. Impaired stress response and reduced anxiety in mice lacking a functional corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1. Nat Genet. 1998;19:162–166. doi: 10.1038/520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vale W, Spiess J, Rivier C, Rivier J. Characterization of a 41-residue ovine hypothalamic peptide that stimulates secretion of corticotropin and β-endorphin. Science. 1981;213:1394–1397. doi: 10.1126/science.6267699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zobel AW, Nickel T, Kunzel HE, Ackl N, Sonntag A, Ising M, Holsboer F. Effects of the high-affinity corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1 antagonist R121919 in major depression: the first 20 patients treated. J Psychiatr Res. 2000;34:171–181. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(00)00016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]