Abstract

Objective

The clinical impact of anti-drug antibodies (ADAbs) in paediatric patients with JIA remains unknown. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to summarize the prevalence of ADAbs in JIA studies; investigate the effect of ADAbs on treatment efficacy and adverse events; and explore the effect of immunosuppressive therapy on antibody formation.

Methods

PubMed, Embase and the Cochrane Library were systematically searched to identify relevant clinical trials and observational studies that reported prevalence of ADAbs. Studies were systematically reviewed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses and appropriate proportional and pairwise meta-analyses were performed.

Results

A total of 5183 references were screened; 28 articles, involving 26 studies and 2354 JIA patients, met eligibility criteria. Prevalence of ADAbs ranged from 0% to 82% across nine biologic agents. Overall pooled prevalence of ADAbs was 16.9% (95% CI, 9.5, 25.9). Qualitative analysis of included studies indicated that antibodies to infliximab, adalimumab, anakinra and tocilizumab were associated with treatment failure and/or hypersensitivity reactions. Concomitant MTX uniformly reduced the risk of antibody formation during adalimumab treatment (risk ratio 0.33; 95% CI 0.21, 0.52).

Conclusion

The association of ADAbs with treatment failure and hypersensitivity reactions indicates their clinical relevance in paediatric patients with JIA. Based on our findings, we recommend a preliminary course of action regarding immunogenicity of biologic agents in patients with JIA. Further strategies to predict, prevent, detect and manage immunogenicity could optimize treatment outcomes and personalize treatment with biologic therapies.

Keywords: juvenile idiopathic arthritis, immunogenicity, biologic therapies, biologic agents, methotrexate, anti-drug antibodies

Rheumatology key messages

Immunization to biologic therapies is common in JIA patients and varies considerably across biologic agents.

Anti-drug antibodies in JIA patients are frequently associated with treatment failure and hypersensitivity events.

Strategies to predict, prevent, detect and manage immunogenicity of biologics could optimize outcomes in JIA.

Introduction

JIA is the most common rheumatic disease during childhood, with a prevalence of 16–150 per 100 000, affecting over 60 000 children in Europe alone [1, 2]. JIA is defined as arthritis of unknown aetiology that begins prior to the age of 16 years and persists for at least 6 weeks, while other causes of arthritis have been excluded [3]. JIA comprises a heterogeneous group of diseases divided into seven categories according to the distribution of arthritis, systemic manifestations and laboratory features [3, 4]. If left untreated, this disease can lead to severe short-term and long-term disability [4].

Biologic therapies have drastically improved treatment outcomes of JIA over the past two decades [5]. Nevertheless, up to 50% of JIA patients do not respond to initial biologic agents (primary failure), lose efficacy over time (secondary failure), or develop adverse events resulting in treatment discontinuation [6–8]. Recent studies of chronic inflammatory diseases in adult patients have investigated the ability of biologic agents to induce antibody formation, termed immunogenicity, in relation to treatment failure and adverse events. These studies demonstrated that the presence of anti-drug antibodies (ADAbs) was indeed associated with primary failure, secondary failure and hypersensitivity reactions [9, 10].

Two mechanisms have been suggested for how ADAbs are able to reduce treatment efficacy. First of all, neutralizing ADAbs (i.e. antibodies that bind to the target-binding region of a biologic agent) can directly prevent binding of biologic agents to their therapeutic target [11]. Secondly, both neutralizing and non-neutralizing ADAbs can result in the formation of immune complexes by binding to the drug, which increase drug clearance and result in lower effective drug concentrations [12, 13]. The pathogenic mechanisms of ADAbs involved in adverse events are not yet fully understood [14].

The presence of ADAbs may also affect clinical efficacy and safety of biologic therapies in JIA patients. However, knowledge on ADAbs in JIA remains scarce and guidelines on the detection and management of immunogenicity do not exist. Therefore, the main objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to summarize the prevalence of ADAbs in patients with JIA across different biologic agents. Furthermore, we investigated the clinical relevance of ADAbs regarding their effect on treatment efficacy, safety and the effect of immunosuppressive therapy on the formation of ADAbs.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis guidelines [15].

Eligibility criteria

Briefly, the following criteria were used to select articles for inclusion in this review: patients with a diagnosis of JIA according to the ILAR classification criteria; treatment with any biologic or biosimilar agent; and ADAb measurements. We included randomized clinical trials, non-randomized clinical trials and observational studies (both prospective and retrospective) published in peer-reviewed journals. We excluded articles with multiple disease states when the prevalence of ADAbs could not be determined for patients with JIA only. Full eligibility criteria with rationale are provided in Supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online.

Information sources

A comprehensive search strategy was developed to identify relevant studies from published literature in PubMed (MEDLINE), Embase and Cochrane Library up to 16 July 2018. The majority of studies on efficacy, safety and pharmacokinetics report immunogenicity data without including key terms such as ‘ADAbs’ or ‘immunogenicity’ in their title or abstract. Therefore, the search strategy was only limited by synonyms for JIA and any biologic or biosimilar agent (search terms and search strategies are provided in Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Material, section Full Search Strategy, available at Rheumatology online). In addition to the database search, reference lists of included articles were searched to identify additional relevant studies. Study protocols and trial registration databases (clinicaltrials.gov and clinicaltrialsregister.eu) were searched for additional information on included studies.

Study selection

Records were screened on title and abstract by one author (M.D.). Original research that addressed efficacy, safety or pharmacokinetics of biologic agents was independently reviewed in full-text by two authors (M.D. and J.S.) and publications that met all eligibility criteria were included in the review. Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two authors. In case of identical study data across publications, only the most recent article was included.

Data collection

Authors extracted relevant data into tabulated summaries. Data collected from each article included publication details: authors, year, study design and follow-up duration; patient characteristics: JIA subtype, age, gender and disease duration; intervention: biologic agent, treatment duration, exposure, dosage, schedule, route of administration and concomitant therapy; outcomes: ADAb prevalence, therapeutic response, drug concentrations, adverse events and ADAb detection method.

The primary outcome was the prevalence of ADAbs. Secondary outcomes were the association of ADAbs with efficacy, the association of ADAbs with drug concentration, the association of ADAbs with adverse events and the effect of immunosuppressive therapy on the formation of ADAbs.

Quality assessment

The validity of ADAb detection of included studies was assessed based on individual components of the Cochrane risk of bias tool and the STROBE checklist [16, 17]. The following characteristics of included studies were taken into consideration to address (risk of) bias influencing development of ADAbs: eligibility criteria resulting in a study population with a specific drug response (selection bias), not accounting for variables (i.e. concomitant therapy) that could influence development of ADAbs (effect modification), incomplete reporting of ADAb detection method or timing of antibody measurements (detection method), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) and selective reporting of outcomes (reporting bias).

Statistical analysis

In order to provide a meaningful review, meta-analyses were only performed when studies were sufficiently homogeneous with regard to outcome criteria. Proportional and pairwise meta-analyses were performed using the ‘meta’ package (version 4.9–2) in ‘R’ version 3.5.1. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Studies that restricted ADAb measurements to a specific subset of the study population were excluded from the meta-analysis of prevalence. Prevalence estimates of ADAbs were reported as percentages, stratified by biologic agent and variance was calculated using double arcsine transformation [18]. Where possible, secondary outcomes were analysed by meta-analysis of risk ratios. Assuming methodological and clinical heterogeneity across studies, all meta-analyses were performed using random effects methods. Variance was expressed as 95% confidence interval. Heterogeneity was examined by calculating I2 for inconsistency (Der Simonian-Laird). Forest plots were generated and sorted by sample size to assess publication bias. Meta-analyses were stratified by important study variables including ADAb detection method, concomitant immunosuppressive therapy, age and follow-up duration to assess substantial (I2> 40%) heterogeneity between studies.

Results

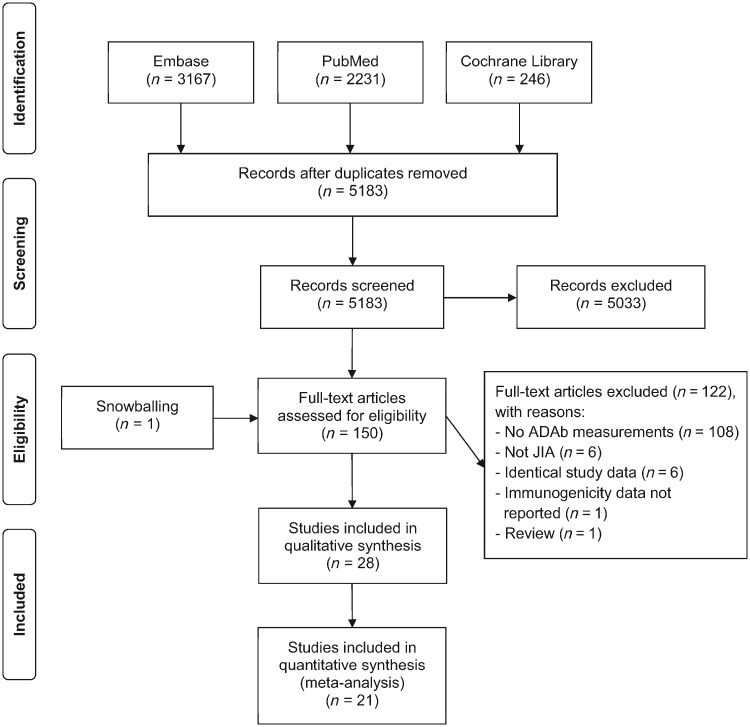

The flow-chart of the selection of studies is presented in Fig. 1. The database search generated 5183 records after duplicates were removed. After screening on title and abstract, 150 full-text articles reporting efficacy, safety, pharmacokinetics or immunogenicity of biologic agents in JIA patients remained. Primarily, 108 articles were excluded because ADAb measurements were not included. A total of 28 full-text articles, involving 26 studies, met eligibility criteria and were included in the qualitative analysis. In addition, 21 studies were included in the meta-analysis of prevalence and six studies were evaluated for the effect of immunosuppressive therapy on the formation of ADAbs.

Fig. 1.

Flow-chart of the selection of studies

ADAb: anti-drug antibody.

Overall, 26 studies provided data of 2354 individual JIA patients receiving the following biologic agents: four TNF inhibitors (etanercept, n = 268 [19–22]; infliximab, n = 122 [23, 24]; adalimumab, n = 355 [25–31]; golimumab, n = 173 [32]), one anti-IL6 (tocilizumab, n = 716 [33–38]), one anti-CTLA4 (abatacept, n = 409 [39–41]) and three anti-IL1 (anakinra, n = 86 [42]; canakinumab, n = 201 [43–45]; rilonacept, n = 24 [46]). Longitudinal studies with multiple publications were available for treatment with etanercept (up to 96 weeks) [22], infliximab (up to 204 weeks) [24], tocilizumab (up to 168 weeks) [35], abatacept (up to 7 years) [40] and canakinumab (at least 104 weeks) [45]. Immunogenicity data and baseline patient characteristics of canakinumab studies were described in separate articles. Therefore, Sun et al. [45] was included in the meta-analysis of prevalence and Ruperto et al. [43, 44] were included for patient characteristics at baseline. Characteristics of all included studies and patients at baseline are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies and patients at baseline

| Study | JIA subtype | Drug | Dosage | Design | Primary outcome | Patients (n) | Female (%) | Follow- up, weeks | Age, yearsa | Disease duration, yearsa | MTX (%) | Other DMARDs (%) | CS (%) | ADAb detection method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lovell et al. 2000 [19] | pcJIA | ETN s.c. | 0.4 mg/kg, 2xw | OL–RCT | Efficacy | 69 | 62 | 28 | 10.5 | 5.9 | 0 | 0 | 36 | NA |

| Mori et al. 2012 [20] | pcJIA | ETN s.c. | 0.2 mg/kg, 0.4 mg/kg, 2xw | LTE | Efficacy | 32 | 88 | 96 | 13.7 | 6.1 | 0 | 0 | 81 | NA |

| Alcobendas et al. 2016 [21] | oJIA, pJIA, ERA, PsA | ETN s.c. | 0.8 mg/kg, qw | RO | ADAbs | 40 | 68 | NA | 11.3 (3.5) | NA | 20 | NA | NA | ELISA |

| Constantin et al. 2016 [22] | oJIA, ERA, PsA | ETN s.c. | 0.8 mg/kg, qw | OL | Efficacy | 127 | 57 | 96 | 11.7 (4.5) | 2.23 (2.2) | 68 | 18 | 13 | NA |

| Ruperto et al. 2007/2010 [23, 24] | pcJIA | IFX i.v. | 6 mg/kg, q8wb | OL–RCT–LTE | Efficacy | 62 | 79 | 204 | 11.1 (4.0) | 3.6 (3.4) | 100 | 0 | 34 | ELISA |

| 3mg/kg, q8wc | 60 | 88 | 204 | 11.3 (4.0) | 4.2 (3.6) | 100 | 0 | 43 | ||||||

| Lovell et al. 2008 [25] | pcJIA | ADA s.c. | 24 mg/m2, q2w | OL–RCT | Efficacy | 85 | 80 | 48 | 11.4 (3.3) | 4.0 (3.7) | 100 | 0 | 5 | NA |

| 86 | 78 | 48 | 11.1 (3.8) | 3.6 (4.0) | 0 | 0 | 2 | |||||||

| Imagawa et al. 2012 [26] | pcJIA | ADA s.c. | 20 mg (<30 kg), 40 mg (≥30 kg), q2w | OL | Efficacy | 25 | 80 | 60 | 13.0 (3.38) | 4.7 (3.72) | 80 | 0 | 72 | ELISA |

| Kingsbury et al. 2014 [27] | pcJIA | ADA s.c. | 24 mg/m2, q2w | OL | Safety | 32 | 88 | 24 | 3.0 (0.72) | 1.0 (0.78) | 84 | 3 | 63 | ELISA |

| Burgos-Vargas et al. 2015 [28] | ERA | ADA s.c. | 24 mg/m2, q2w | RCT–LTE | Efficacy | 46 | 33 | 52 | 12.9 (2.9) | 2.6 (2.3) | 52 | 20 | NA | NA |

| Skrabl-Baumgartner et al. 2015 [29] | oJIA, pJIA, ERA | ADA s.c. | 24 mg/m2, q2w | PO | Efficacy | 23 | 87 | 208 | 14.2 (7.9–17.2) | NA | 74 | NA | NA | ELISA |

| Leinonen et al. 2017 [30] | JIA-uveitis | ADA s.c. | 24 mg/m2, q2w | RO | ADAbs | 9 | NA | 104 | 9.3 [3.7–14.9] | NA | 29 | NA | NA | NA |

| 22 | NA | 104 | 9.8 [4.4–16.8] | NA | 91 | NA | NA | |||||||

| Marino et al. 2018 [31] | oJIA, pJIA, ERA | ADA s.c. | 24 mg/m2, q2w | PO | ADAbs | 27 | NA | 64 | 9.5 (3.3) | 4.79 (3.0) | 59 | 0 | 0 | SPR |

| Brunner et al. 2018 [32] | pcJIA | GLM s.c. | 30 mg/m2, q4w | OL–RCT | Efficacy | 173 | 76 | 48 | 11.2 (4.4) | NA | 100 | 0 | 24 | ELISA |

| De Benedetti et al. 2012 [33] | sJIA | TCZ i.v. | 8 mg/kg (<30 kg), 12 mg/kg (≥30 kg), q2w | RCT–LTE | Efficacy | 37 PCB | 46 | 52 | 9.1 (4.4) | 5.1 (4.4) | 70 | 0 | 84 | NA |

| 75 TCZ | 52 | 52 | 10.0 (4.6) | 5.2 (4.0) | 69 | 0 | 93 | |||||||

| Imagawa et al. 2012 [34] | pcJIA | TCZ i.v. | 8mg/kg, q4w | OL | Efficacy | 19 | 79 | 48 | 12 [3–9] | 4.7 [1–17] | 0 | 0 | NA | NA |

| Yokota et al. 2014 [35] | sJIA | TCZ i.v. | 8 mg/kg, q2w | OL–RCT–LTE | Safety | 67 | 57 | 168 | 8.3 (4.3) | 4.4 (3.5) | 0 | 0 | 100 | ELISA |

| Brunner et al. 2015 [36] | pcJIA | TCZ i.v. | 8 mg/kg (≥30 kg),8–10 mg/kg (<30 kg), q4w | OL–RCT | Efficacy | 188 | 77 | 40 | 11.0 (4.01) | 4.2 (3.67) | 79 | 0 | 46 | NA |

| Yokota et al. 2016 [37] | sJIA | TCZ i.v. | 8 mg/kg, q2w | OL | Safety | 417 | 48 | 52 | 11.2 (7.2) | 5.8 (5.9) | 26 | 18 | 88 | NA |

| Yasuoka et al. 2018 [38] | sJIA | TCZ i.v. | 8 mg/kg, q2w | RO | Safety | 35 ISR− | 60 | 12 | 7.4 [2.8–25.9] | 1.3 [0–14.4] | NA | NA | 100 | ELISA |

| 5 ISR+ | 100 | 12 | 2.5 [2.1–10.5] | 0.17 [0.1–1.8] | NA | NA | 100 | |||||||

| Ruperto et al. 2010 [39] / Lovell et al. 2015 [40] | pcJIA | ABA i.v. | 10 mg/kg, q4w | LTE | Efficacy | 190 | 72 | 270 (91)d | 12.4 (3.0) | 4.4 (3.8) | 74 | 0 | 28 | ELISA |

| Brunner et al. 2018 [41] | pcJIA | ABA s.c. | 50 mg (<25 kg),87.5 mg (<50 kg),125 mg (≥50 kg), qw | OL | PK | 173 | 79 | 104 | 13.0 (10.0–15.0) | 2.0 (0.0–4.0) | 79 | NA | 32 | NA |

| 46 | 61 | 104 | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) | 0.5 (0.0–1.0) | 80 | NA | 20 | |||||||

| Ilowite et al. 2009 [42] | pcJIA | ANA s.c. | 1 mg/kg, qd | OL–RCT–LTE | Safety | 86 | 73 | 80 | 12 (3–17)e | 4.7 (1–16)e | 78 | 29 | 58 | SPR |

| Ruperto et al. 2012 [43] | sJIA | CNK s.c. | Stage 1 (15 days): 0.5 mg/kg, 1.5 mg/kg, 4.5 mg/kg, SD or DD.Stage 2: 4 mg/kg, q4w | OL–LTE | Efficacy | 23 | 48 | 104 | 10 [4–19] | 3.2 [0.6–17] | 26 | 0 | 83 | SPR |

| Ruperto et al. 2012 [44] | sJIA | CNK s.c. | 4 mg/kg, SD | RCT | Efficacy | 41 PCB | 56 | 4 | 9.0 (6.0–14.0) | 2.0 (1.2–5.2) | 59 | 0 | 68 | ECL |

| 43 CNK | 63 | 4 | 8.0 (4.0–13.0) | 2.3 (1.0–4.7) | 67 | 0 | 72 | |||||||

| Ruperto et al. 2012 [44] | sJIA | CNK s.c. | 4 mg/kg, q4w | OL–RCT–LTE | Efficacy | 177 CNK | 55 | 104 | 8.0 (5.0–12.0) | 2.1 (0.8–4.3) | 53 | 0 | 72 | |

| Lovell et al. 2013 [46] | sJIA | RLN s.c. | 2.2 mg/kg, 4.4 mg/kg, qwf | RCT–LTE | Safety | 24 | 67 | 104 | 12.6 (4.3) | 3.1 | NA | 0 | NA | NA |

Age and disease duration are presented as mean, mean (s.d.), median (interquartile range), or median [range].

Placebo at week 0, 2 and 6; induction with 6 mg/kg at 14, 16 and 20 weeks.

Induction with 3 mg/kg at 0, 2, 6, 14 weeks, placebo at 16 weeks and 3 mg/kg at 20 weeks.

Data are presented as mean (s.d.).

Data are presented as mean (range).

Induction with same dose of rilonacept on day 0, 3, 7, 14 and 21. ABA: abatacept; ADA: adalimumab; ADAb: anti-drug antibody; ANA: anakinra; CNK: canakinumab; DD: double dose; ECL: electrochemiluminescence; ERA: enthesitis-related arthritis; ETN: etanercept; GLM: golimumab; IFX: infliximab; ISR: infusion site reaction; LTE: long-term extension study; NA: not available; OD: on demand dose-escalation; OL: open-label study; (e)oJIA: (extended) oligoarticular JIA; PCB: placebo; pcJIA: polyarticular-course JIA (defined as ≥5 inflamed joints at enrolment or in patient history, without systemic symptoms); pJIA: polyarticular JIA; PK: pharmacokinetics; PO: prospective observational study; PsA: psoriatic arthritis; qd: every day; qw: every week; qxw: every x weeks; RCT: randomized clinical trial; RLN: rilonacept; RO: retrospective observational study; SD: single dose; SPR: surface plasmon resonance; sJIA: systemic JIA; TCZ: tocilizumab; 2xw: twice weekly.

Risk of bias within individual studies was assessed using predefined criteria. ADAb detection methods or timing of immunogenicity assessments were not available for 12 out of 26 studies [19, 20, 22, 25, 28, 30, 33, 34, 36, 37, 41, 46]. Studies that did report timing of immunogenicity assessments, measured ADAbs at baseline, at the end of an open-label phase, at the end of a placebo-controlled phase and at several visits during an open-label extension phase (simultaneously with visits for efficacy and safety assessments). In nine studies, an ELISA was used to detect ADAbs [21, 26, 27, 29, 32, 35, 38–40]. Three studies used surface plasmon resonance-based assays [31, 42, 43] and two studies used electrochemiluminescence to detect ADAbs [44]. Few studies were completely without risk of bias influencing ADAb detection. A full summary of the risk of bias assessment is provided in Supplementary Table S3, available at Rheumatology online.

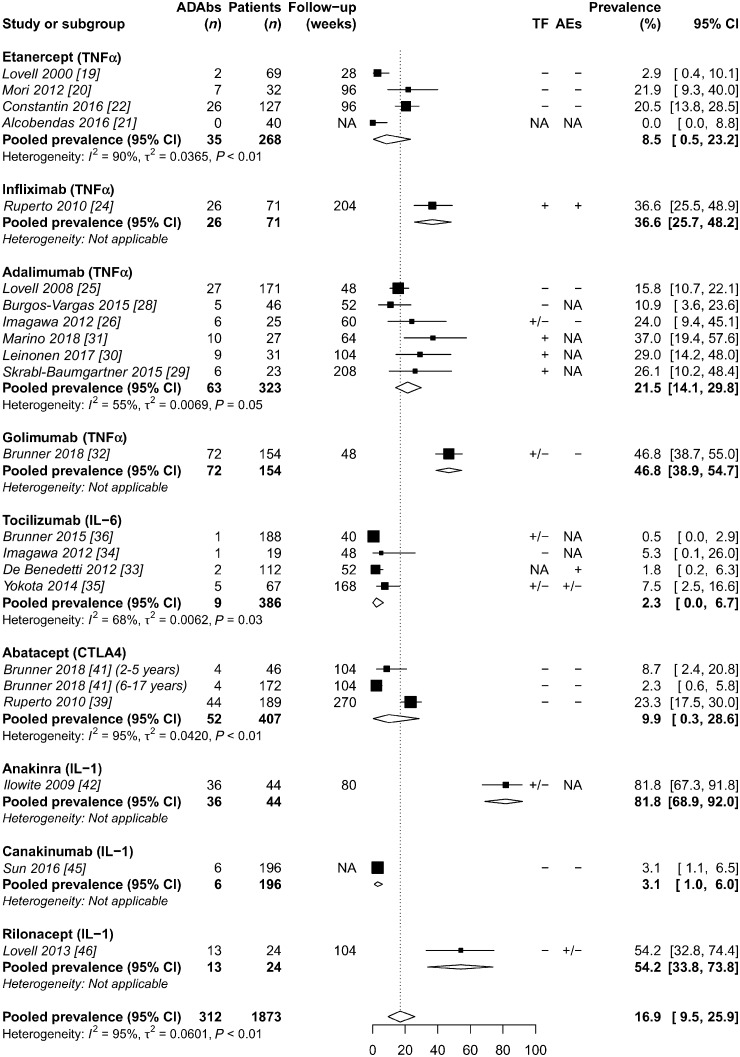

Prevalence of ADAbs in JIA

The prevalence of ADAbs varied considerably from 0% to 82% with an overall pooled prevalence of 16.9% (95% CI 9.5, 25.9) (Fig. 2). Proportional meta-analysis of ADAb prevalence demonstrated high heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 95%) (Supplementary Fig. S1, available at Rheumatology online). After studies were grouped by biologic agent, remaining heterogeneity between studies was substantially reduced through subgroup analyses of important study variables including ADAb detection method, the use of concomitant MTX and follow-up duration (Supplementary Figs S2–S5, available at Rheumatology online). Forest plots showed no evidence of publication bias.

Fig. 2.

Random effects meta-analysis of ADAb prevalence in JIA stratified by biologic agent

ADAbs: anti-drug antibodies; AEs: adverse events; NA: not available; TF: treatment failure; +: strong association with ADAbs; +/−: possible association with ADAbs; −: no association with ADAbs.

Four studies reported additional point prevalence of ADAbs at different time points [22–24, 26, 42]. Treatment of 127 patients with etanercept resulted in ADAb development in 5% at 12 weeks, 12% at 48 weeks, 13% at 96 weeks and in 21% of patients overall, while only 38% (10/26) with ADAbs tested positive more than once [22]. In infliximab-treated patients, ADAbs were detected in 25% at 52 weeks, increasing to 37% at 204 weeks [23, 24]. For adalimumab, ADAbs were detected in 8% at 8 weeks, increasing to 24% having at least one and 8% having at least two ADAb-positive samples at 60 weeks [26]. Marino et al. [31] reported that 30% of patients with ADAbs tested positive more than once. Prevalence of antibodies to anakinra increased from 75% at 12 weeks to 82% at 12 months [42]. Although antibodies to tocilizumab were also detected within 12 weeks, prevalence of ADAbs did not appear to increase with longer treatment duration [33–36]. During treatment with intravenous and subcutaneous abatacept, the majority of ADAb-positive patients tested positive only once (59% and 50%, respectively) [39–41]. Studies of golimumab and rilonacept did not report ADAb testing at different time points [32, 46]. For canakinumab, only one patient demonstrated persistent immunogenicity (⩾2 ADAb-positive samples), which resolved after continued treatment [45].

Treatment failure and ADAbs

Although treatment with etanercept induced ADAbs in some patients, detected ADAbs were non-neutralizing and none of the etanercept studies reported an association between treatment failure and the presence of non-neutralizing ADAbs (Supplementary Table S4, available at Rheumatology online) [19–22]. Similarly, studies of abatacept and rilonacept also did not report an association between the presence of ADAbs and treatment failure [39, 40, 46]. In contrast, clinical response to infliximab was less frequently achieved by patients with ADAbs compared with patients without ADAbs (67% vs 79%, respectively). Moreover, patients treated with 6 mg/kg infliximab achieved better maintenance of drug concentrations and exhibited lower rates of ADAbs compared with patients treated with 3 mg/kg (12% vs 38%, respectively) [23]. In adalimumab studies, increasing median disease activity scores and significantly lower adalimumab concentrations were observed in patients with ADAbs (1.63 mg/l vs 14.13 mg/l) [29, 31]. Likewise, in patients with JIA-associated uveitis, antibodies to adalimumab were associated with a significant higher grade of uveitis and lower median trough concentration (<0.01 mg/l vs 9.4 mg/l) [30]. Nevertheless, two adalimumab studies did not observe an association between the presence of ADAbs and treatment failure but these analyses were not published [25, 28]. Neutralizing potential of antibodies to infliximab or adalimumab was not determined. In patients treated with golimumab, neutralizing ADAbs were detected in 46% (30/66) of ADAb-positive patients. Although high titres (>1: 1000) neutralizing antibodies to golimumab were associated with lower trough concentrations, seven out of eight patients with high antibody titres achieved clinical response to golimumab [32]. Three studies of tocilizumab reported on ADAbs and treatment efficacy. Despite low immunogenicity of tocilizumab overall, 43% (3/7) of patients with neutralizing ADAbs discontinued treatment due to primary or secondary failure compared with 6% (17/267) of ADAb-negative patients [34–36]. Antibodies to anakinra were also associated with lack of efficacy in all (4/64) patients who tested positive for neutralizing antibodies at 12 weeks [42]. However, none of the remaining patients tested positive for neutralizing ADAbs during 12 months of extended treatment with anakinra and non-neutralizing antibodies to anakinra were not associated with treatment failure [42]. All antibodies to canakinumab lacked neutralizing potential and none of the ADAb-positive patients experienced treatment failure or exhibited decreased drug concentrations [45].

Adverse events and ADAbs

During infliximab treatment, infusion reactions were observed in 58% (15/26) of infliximab-treated patients with ADAbs compared with 19% (5/26) in those without (Supplementary Table S4, available at Rheumatology online). Among those with ADAbs, infusion reactions occurred in 60% (12/20) of patients treated with 3 mg/kg infliximab vs 50% (3/6) of patients treated with 6 mg/kg infliximab. Moreover, 20% (4/20) of patients with ADAbs experienced a possible anaphylactic reaction vs none without ADAbs [23]. Overall, tocilizumab studies detected ADAbs in 68% (15/22) of patients with infusion reactions [33, 35, 37, 38]. Furthermore, all patients (9/23) who experienced ⩾3 injection site reactions to rilonacept also tested positive for ADAbs [46]. None of the ADAb-positive patients experienced injection site reactions in studies of canakinumab and subcutaneous abatacept [41, 45]. Although limited data were available, studies of etanercept, adalimumab, golimumab and intravenous abatacept did not report an association between the presence of ADAbs and adverse events [22, 25, 26, 32, 39, 40]. The association between antibodies to anakinra and adverse events was not analysed [42].

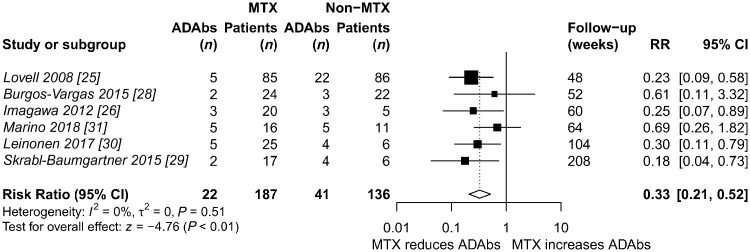

Concomitant immunosuppressive therapy

Six studies reported ADAb prevalence and stratified patients according to concomitant MTX therapy during treatment with adalimumab. The addition of MTX therapy reduced the risk of ADAb development with 67% in these studies (risk ratio 0.33; 95% CI 0.21, 0.52) [25, 26, 28–31] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Random effects meta-analysis of concomitant MTX and the risk of ADAb development during adalimumab treatment

ADAbs: anti-drug antibodies; RR: risk ratio.

Patients who received concomitant MTX were also included in studies of other biologic agents (i.e. anakinra, rilonacept, etanercept, abatacept and tocilizumab). However, patients were not stratified according to immunosuppressive therapy and thus other pairwise meta-analyses were not performed [22, 37, 39–42, 46].

Discussion

The percentage of patients with JIA that developed ADAbs varied widely across nine different biologics (0–82%) with a pooled prevalence of 16.9% (95% CI 9.5, 25.9). Although prevalence of ADAbs within studies generally increased with longer treatment duration, ADAbs appeared transient in most patients [22, 31, 39–41]. Nevertheless, the presence of antibodies against biologic agents was associated with primary failure, secondary failure or hypersensitivity-associated events, which was most evident in studies of infliximab and adalimumab [23, 24, 29, 31]. Although detected in a small number of patients, neutralizing antibodies to tocilizumab or anakinra were also associated with primary or secondary failure. Furthermore, a much higher prevalence of antibodies to tocilizumab was observed in patients with hypersensitivity-associated events. These results indicate the clinical relevance of ADAbs in JIA patients treated with these biologic agents. In contrast, antibodies to etanercept, abatacept or canakinumab did not appear to be associated with treatment failure or adverse events.

Heterogeneity was high in the meta-analysis of ADAb prevalence and pooled results over all studies should be interpreted with caution. However, stratification of meta-analysis by biologic agent and subgroup analyses by ADAb detection method, concomitant immunosuppressive therapy and follow-up duration significantly reduced the amount of unexplained variability. However, immunogenicity of biologic therapies is affected by many more factors, both intrinsic (e.g. foreign or T cell epitopes, aggregation, post-translational modifications and target molecules) and extrinsic (e.g. route of administration, concomitant immunosuppressive therapy and underlying pathology) [47]. Therefore, we acknowledge that the observed heterogeneity of ADAb prevalence between studies could also be explained by other variables.

Receptor constructs, such as etanercept and abatacept, might offer an advantage over humanized and fully human antibodies regarding clinical impact of ADAbs on efficacy and safety. This might be explained by the fact that only the linker region of receptor constructs contains foreign epitopes and receptor constructs do not express an idiotope (i.e. antigen-binding region), resulting in a lack of neutralizing antibodies [12]. Furthermore, low immunogenicity of some biologics might also be associated with inhibition of their target molecule. For example, tocilizumab and canakinumab inhibit IL-6 and IL-1β respectively, which are both essential for T cell-dependent antibody production [48, 49].

The detection of ADAbs is technically challenging and the large variation between assays influences results of immunogenicity assessments. Three studies used surface plasmon resonance-based assays, which allows for a more accurate detection of low-affinity ADAbs than ELISA or electrochemiluminescence. Antibodies to adalimumab were indeed more frequently detected by Marino et al. using a surface plasmon resonance-based assay compared with studies of adalimumab using ELISAs (37% vs 7–26%) [26, 27, 29, 31, 50]. Therefore, standardization of assay methods is necessary to provide consequent immunogenicity assessments across studies and biologic agents.

Nonetheless, the association of ADAbs with treatment failure and adverse events indicates the importance of strategies to manage immunogenicity in paediatric patients with JIA. Lower drug concentrations were associated with the presence of ADAbs and thus maintenance of therapeutic drug concentrations appears to be of importance. This is in agreement with the ‘discontinuity theory’ of the immune system, in which the intermittent appearance of an antigen promotes a long-lasting immune response [51]. In addition to maintenance of drug concentrations, concomitant therapy with MTX significantly reduced the risk of ADAbs in paediatric patients, as well as in adults, indicating that both strategies are valuable to prevent the development of ADAbs [9, 10, 52].

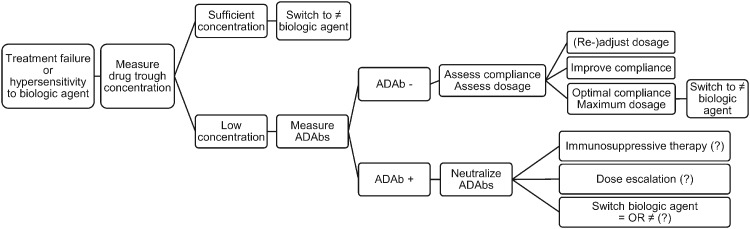

Considering technical challenges and the association of drug concentrations with the presence of ADAbs, regular measurements of drug trough concentrations may be preferred over immunogenicity assessments in clinical practice. Furthermore, antibodies to biologic agents frequently affect clinical efficacy and safety in a small number of patients. Therefore, we recommend a preliminary course of action using trough concentration measurements in patients who experience primary failure, secondary failure or hypersensitivity-associated events, based on previously reported algorithms for patients with RA [53–55] (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Course of action for treatment failure or hypersensitivity during JIA treatment with biologic agents

Treatment failure (primary or secondary) or hypersensitivity-associated events: assess serum drug trough concentration. (i) Sufficient drug concentration: switch to a biologic agent of a different class. (ii) Insufficient drug concentration: measure ADAbs. (a) ADAb-negative: (1) assess and (re-)adjust dosage to patient’s weight; (2) assess and optimize therapeutic compliance; (3) optimal compliance and maximum dosage: switch to a biologic agent of a different class. (b) ADAb-positive: neutralize ADAbs: (1) immunosuppressive therapy, (2) dose escalation, (3) switch to another biologic agent – identical or different class. ADAb: anti-drug antibody; ?: research question for future research.

Current guidelines recommend switching to another biologic agent in case of treatment failure or discontinuation due to adverse events. However, studies of drug survival in patients with JIA have demonstrated reduced efficacy of second (and third) biologics, especially after switching due to primary failure [6, 8]. In case of treatment failure and the presence of ADAbs, strategies to counteract ADAbs could prevent switching to a second biologic with potentially reduced efficacy. ADAbs may disappear after dose escalation or continued treatment [26, 45]. However, De Benedetti et al. [33] reported severe adverse events after continued tocilizumab treatment in patients with ADAbs. More studies are warranted that address whether dose escalation is a safe strategy and which dose increase is required to counteract the presence of ADAbs. Moreover, the ability of immunosuppressive therapies to prevent antibody formation and to neutralize antibody formation after ADAbs have developed needs to be further investigated. Whether a biologic agent of the same class or a different class is more effective after discontinuation due to antibody formation is also not known.

There are some limitations to the interpretation of our results. A total of 12 studies did not include assay methods or timing of ADAb measurements, which could have influenced ADAb detection. Four studies found little correlation between ADAbs and reduced treatment efficacy or adverse events but did not report effect measures, indicating a high risk of selective outcome reporting in these studies and possible underestimation of the clinical impact of ADAbs [22, 32, 39, 40, 46]. Furthermore, outcomes were often not specifically reported for patients with or without ADAbs, which prevented pairwise meta-analyses of the association of ADAbs with treatment failure or adverse events.

Nevertheless, the prevalence of antibodies to infliximab, adalimumab, tocilizumab and canakinumab appeared similar in paediatric patients with JIA compared with adults with other chronic inflammatory diseases [53, 56, 57]. In contrast, antibodies to anakinra (0–3% vs 6%), rilonacept (35% vs 54%), golimumab (0–7% vs 47%), etanercept (0–18% vs 0–26%) and abatacept (1–3% vs 2–23%) were less frequently detected in adult patients with chronic inflammatory diseases [53, 55, 58, 59]. Brunner et al. [41] included two age groups (2–5 years vs 6–17 years) and detected a higher prevalence of antibodies to abatacept in the younger age group (2% vs 9%). Nonetheless, definite patient-related factors influencing immunogenicity have yet to be identified.

Conclusion

This comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis on immunogenicity of biologic therapies in JIA highlights that the presence of ADAbs is sometimes transient but can be associated with treatment failure and adverse events. Furthermore, standardization of immunogenicity assays is necessary to provide consistent results across studies and biologic agents. Immunogenicity of biologic therapies is of high clinical relevance and should be considered in case of treatment failure or hypersensitivity to biologic agents. Future research should focus on additional strategies to prevent the development of ADAbs and to maintain or restore clinical efficacy after ADAb development. Strategies to predict, prevent, detect and manage immunogenicity can potentially improve treatment outcomes and lead to a more personalized treatment with biologic therapies.

Funding: This study was sponsored by the Dutch Arthritis Foundation (Reumafonds) grant RF 901.

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Ravelli A, Martini A.. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet 2007;369:767–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thierry S, Fautrel B, Lemelle I, Guillemin F.. Prevalence and incidence of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a systematic review. Joint Bone Spine 2014;81:112–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P. et al. International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol 2004;31:390–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Prakken B, Albani S, Martini A.. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet 2011;377:2138–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Davies R, Gaynor D, Hyrich KL, Pain CE.. Efficacy of biologic therapy across individual juvenile idiopathic arthritis subtypes: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2017;46:584–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Otten MH, Prince FHM, Anink J. et al. Effectiveness and safety of a second and third biological agent after failing etanercept in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from the Dutch National ABC Register. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:721–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Woerner A, Uettwiller F, Melki I. et al. Biological treatment in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: achievement of inactive disease or clinical remission on a first, second or third biological agent. RMD Open 2015;1:e000036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tynjala P, Vahasalo P, Honkanen V, Lahdenne P.. Drug survival of the first and second course of anti-tumour necrosis factor agents in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:552–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maneiro JR, Salgado E, Gomez-Reino JJ.. Immunogenicity of monoclonal antibodies against tumor necrosis factor used in chronic immune-mediated inflammatory conditions: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1416–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Garces S, Demengeot J, Benito-Garcia E.. The immunogenicity of anti-TNF therapy in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: a systematic review of the literature with a meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1947–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. van Schouwenburg PA, van de Stadt LA, de Jong RN. et al. Adalimumab elicits a restricted anti-idiotypic antibody response in autoimmune patients resulting in functional neutralisation. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:104–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van Schouwenburg PA, Rispens T, Wolbink GJ.. Immunogenicity of anti-TNF biologic therapies for rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2013;9:164–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rojas JR, Taylor RP, Cunningham MR. et al. Formation, distribution, and elimination of infliximab and anti-infliximab immune complexes in cynomolgus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2005;313:578–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kalden JR, Schulze-Koops H.. Immunogenicity and loss of response to TNF inhibitors: implications for rheumatoid arthritis treatment. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2017;13:707–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J. et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:W65–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Higgins J, Green S. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 510, 2011. www.handbook.cochrane.org (1 August 2018, date last accessed).

- 17. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M. et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007;370:1453–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Barendregt JJ, Doi SA, Lee YY, Norman RE, Vos T.. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Community Health 2013;67:974–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lovell DJ, Giannini EH, Reiff A. et al. Etanercept in children with polyarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group. N Engl J Med 2000;342:763–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mori M, Takei S, Imagawa T. et al. Safety and efficacy of long-term etanercept in the treatment of methotrexate-refractory polyarticular-course juvenile idiopathic arthritis in Japan. Mod Rheumatol 2012;22:720–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Alcobendas R, Rodriguez-Vidal A, Pascual-Salcedo D. et al. Monitoring serum etanercept levels in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a pilot study. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2016;34:955–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Constantin T, Foeldvari I, Vojinovic J. et al. Two-year efficacy and safety of etanercept in pediatric patients with extended oligoarthritis, enthesitis-related arthritis, or psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2016;43:816–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ruperto N, Lovell DJ, Cuttica R. et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of infliximab plus methotrexate for the treatment of polyarticular-course juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:3096–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ruperto N, Lovell DJ, Cuttica R. et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of infliximab plus methotrexate for the treatment of polyarticular-course juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: findings from an open-label treatment extension. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:718–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lovell DJ, Ruperto N, Goodman S. et al. Adalimumab with or without methotrexate in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2008;359:810–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Imagawa T, Takei S, Umebayashi H. et al. Efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and safety of adalimumab in pediatric patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis in Japan. Clin Rheumatol 2012;31:1713–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kingsbury DJ, Bader-Meunier B, Patel G. et al. Safety, effectiveness, and pharmacokinetics of adalimumab in children with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis aged 2 to 4 years. Clin Rheumatol 2014;33:1433–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Burgos-Vargas R, Tse SML, Horneff G. et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study of adalimumab in pediatric patients with enthesitis-related arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2015;67:1503–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Skrabl-Baumgartner A, Erwa W, Muntean W, Jahnel J.. Anti-adalimumab antibodies in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: frequent association with loss of response. Scand J Rheumatol 2015;44:359–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Leinonen ST, Aalto K, Kotaniemi KM, Kivela TT.. Anti-adalimumab antibodies in juvenile idiopathic arthritis-related uveitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2017;35:1043–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Marino A, Real-Fernandez F, Rovero P. et al. Anti-adalimumab antibodies in a cohort of patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: incidence and clinical correlations. Clin Rheumatol 2018;37:1407–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brunner HI, Ruperto N, Tzaribachev N. et al. Subcutaneous golimumab for children with active polyarticular-course juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results of a multicentre, double-blind, randomised-withdrawal trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:21–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. De Benedetti F, Brunner HI, Ruperto N. et al. Randomized trial of tocilizumab in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. N Engl J Med 2012;367:2385–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Imagawa T, Yokota S, Mori M. et al. Safety and efficacy of tocilizumab, an anti-IL-6-receptor monoclonal antibody, in patients with polyarticular-course juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Mod Rheumatol 2012;22:109–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yokota S, Imagawa T, Mori M. et al. Longterm safety and effectiveness of the anti-interleukin 6 receptor monoclonal antibody tocilizumab in patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis in Japan. J Rheumatol 2014;41:759–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brunner HI, Ruperto N, Zuber Z. et al. Efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in patients with polyarticular-course juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from a phase 3, randomised, double-blind withdrawal trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1110–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yokota S, Itoh Y, Morio T. et al. Tocilizumab in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis in a real-world clinical setting: results from 1 year of postmarketing surveillance follow-up of 417 patients in Japan. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:1654–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yasuoka R, Iwata N, Abe N. et al. Risk factors for hypersensitivity reactions to tocilizumab introduction in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Mod Rheumatol 2018;1–4. doi: 10.1080/14397595.2018.1457490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ruperto N, Lovell DJ, Quartier P. et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of abatacept in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:1792–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lovell DJ, Ruperto N, Mouy R. et al. Long-term safety, efficacy, and quality of life in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis treated with intravenous abatacept for up to seven years. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:2759–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brunner HI, Tzaribachev N, Vega-Cornejo G. et al. Subcutaneous abatacept in patients with polyarticular-course juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from a phase III open-label study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018;70:1144–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ilowite N, Porras O, Reiff A. et al. Anakinra in the treatment of polyarticular-course juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: safety and preliminary efficacy results of a randomized multicenter study. Clin Rheumatol 2009;28:129–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ruperto N, Quartier P, Wulffraat N. et al. A phase II, multicenter, open-label study evaluating dosing and preliminary safety and efficacy of canakinumab in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis with active systemic features. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:557–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ruperto N, Brunner HI, Quartier P. et al. Two randomized trials of canakinumab in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. N Engl J Med 2012;367:2396–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sun H, Van LM, Floch D. et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of canakinumab in patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Clin Pharmacol 2016;56:1516–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lovell DJ, Giannini EH, Reiff AO. et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of rilonacept in patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:2486–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Scott DW, Groot ASD.. Can we prevent immunogenicity of human protein drugs? Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:i72–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nakae S, Asano M, Horai R, Sakaguchi N, Iwakura Y.. IL-1 enhances T cell-dependent antibody production through induction of CD40 ligand and OX40 on T cells. J Immunol 2001;167:90–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dienz O, Eaton SM, Bond JP. et al. The induction of antibody production by IL-6 is indirectly mediated by IL-21 produced by CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med 2009;206:69–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lofgren JA, Dhandapani S, Pennucci JJ. et al. Comparing ELISA and surface plasmon resonance for assessing clinical immunogenicity of panitumumab. J Immunol 2007;178:7467–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pradeu T, Jaeger S, Vivier E.. The speed of change: towards a discontinuity theory of immunity? Nat Rev Immunol 2013;13:764–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Krieckaert CLM, Bartelds GM, Lems WF, Wolbink GJ.. The effect of immunomodulators on the immunogenicity of TNF-blocking therapeutic monoclonal antibodies: a review. Arthritis Res Ther 2010;12:217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Vincent FB, Morand EF, Murphy K. et al. Antidrug antibodies (ADAb) to tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-specific neutralising agents in chronic inflammatory diseases: a real issue, a clinical perspective. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:165–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Garcês S, Antunes M, Benito-Garcia E. et al. A preliminary algorithm introducing immunogenicity assessment in the management of patients with RA receiving tumour necrosis factor inhibitor therapies. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1138–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schaeverbeke T, Truchetet M-E, Kostine M. et al. Immunogenicity of biologic agents in rheumatoid arthritis patients: lessons for clinical practice. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2016;55:210–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.European Medicines Agency. Ilaris® (canakinumab). Product Information. 2018. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/ilaris (11 September 2018, date last accessed).

- 57.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Actemra® (tocilizumab). Printed Labeling. 2018. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2017/125276Orig1s114lbl.pdf (11 September 2018, date last accessed).

- 58.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Arcalyst® (rilonacept). Printed Labeling. 2008. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2008/125249s000_LBL.pdf (11 September 2018, date last accessed).

- 59.European Medicines Agency. Kineret® (anakinra). Product Information. 2018. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/kineret (11 September 2018, date last accessed).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.