Abstract

Elucidating the molecular mechanism of the low-dose radiation (LDR)-mediated radioadaptive response is crucial for inventing potential therapeutic approaches to improving normal tissue protection in radiation therapy. ATM, a DNA-damage sensor, is known to activate the stress-sensitive transcription factor NF-κB upon exposure to ionizing radiation. This study provides evidence of the cooperative functions of ATM, ERK, and NF-κB in inducing a survival advantage through a radioadaptive response as a result of LDR treatment (10 cGy X-rays). By using p53-inhibited human skin keratinocytes, we show that phosphorylation of ATM, MEK, and ERK (but not JNK or p38) is enhanced along with a twofold increase in NF-κB luciferase activity at 24 h post-LDR. However, NF-κB reporter gene transactivation without a significant enhancement of p65 or p50 protein level suggests that NF-κB is activated as a rapid protein response via ATM without involving the transcriptional activation of NF-κB subunit genes. A direct interaction between ATM and NF-κB p65 is detected in the resting cells and this interaction is significantly increased with LDR treatment. Inhibition of ATM with caffeine, KU-55933, or siRNA or inhibition of the MEK/ERK pathway can block the LDR-induced NF-κB activation and eliminate the LDR-induced survival advantage. Altogether, these results suggest a p53-independent prosurvival network involving the coactivation of the ATM, MEK/ERK, and NF-κB pathways in LDR-treated human skin keratinocytes, which is absent from mutant IκB cells (HK18/mIκB), which fail to express NF-κB activity.

Keywords: ATM, ERK, NF-κB, Low-dose radiation, Keratinocytes, Free radicals

Mammalian cells exposed to certain low levels of radiation show a temporary but significantly enhanced tolerance to a subsequent exposure to relatively higher doses of radiation [1–5]. This radioadaptive phenotype is evidenced by the activation of an efficient defense system to repair and eliminate radiation-mediated DNA injury [6,7] leading to enhanced cell survival [8,9]. Several gene expression profiles have been described for the low-dose radiation (LDR)-mediated adaptive response in human cells [10,11]. Furthermore, a prosurvival pathway initiated by transcription factor NF-κB is linked to an enhanced cell survival of mouse skin epithelial JB6 cells if preexposed to a low dose of X-rays [12]. However, the exact signaling pathways of the LDR-mediated adaptive response remain to be elucidated.

NF-κB is a well-characterized transcription factor that is involved in signaling during critical events of genotoxic stress [5,13,14]. In resting cells, NF-κB is sequestered in the cytoplasm by binding to its specific inhibitors IκBs [15]. Under varied cytotoxic conditions, IκB kinase phosphorylates the NF-κB inhibitory protein IκB-α, resulting in IκB-α degradation and NF-κB activation [16]. The activated NF-κB (mainly the heterodimer of p65/p50) quickly translocates from the cytoplasm into the nucleus where it binds and up-regulates a wide variety of stress-responsive genes (e.g., antiapoptotic and cell cycle regulators) [17]. Although radiation-induced genes are involved in both cell death (i.e., proapoptotic) and cell survival (i.e., antiapoptotic), several NF-κB-controlled effector genes are shown to protect cells from cellular damage [12,18–21]. Inhibition of IκB-α phosphorylation, which blocks NF-κB activation, increases the radiosensitivity of cells [21,22]. However, the specific upstream events required for NF-κB activation, especially in the context of network elements that are required for the LDR-induced adaptive radioresistance in human cells, remain unclear.

It has long been believed that the fate of an irradiated cell is influenced by a complex and highly regulated signaling network [21,23,24], which contains the elements for sensing and repairing damaged DNA [21,24,25]. The ATM (ataxia telangiectasia mutated) protein, a serine–threonine kinase of the family of phosphatidylinositol kinase-related kinases, is proven to be an essential DNA-damage sensor that plays a critical role in the DNA-damage response [26]. In resting cells, ATM forms an inactive dimer. In irradiated cells, ATM induces the rapid intermolecular autophosphorylation of Ser-1981 that leads to dimer dissociation and ATM kinase activation [27]. Cooperation between ATM and NF-κB is supported by the fact that A-T (ataxia telangiectasia) patients exhibit a defect in NF-κB activation. Moreover, ectopic expression of the ATM protein in A-T cells activates NF-κB in response to camptothecin, a DNA-damaging compound [28]. In addition, ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase), a member of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family, is also an essential element in generating a stress response [29–31] and is also required for NF-κB induction [32,33]. Although ATM, ERK, and NF-κB are suggested to participate in the stress response induced by various genotoxic insults [22,32,34], it is unknown whether a cooperative interaction between ATM, MEK/ERK, and NF-κB is responsible for the radioadaptive response induced by LDR in human cells. Following the observation of an adaptive radioprotective response in mouse skin epithelial cells, this study demonstrates a similar radioadaptive response in human skin keratinocytes that is associated with a coactivation ATM, MEK/ERK, and NF-κB. Because human keratinocytes are immortalized by the overexpression of human papillomavirus HPV18 [35,36], which encodes E6 protein that in turn inactivates p53 expression, this study is unique in that it demonstrates a p53-independent LDR-mediated radioadaptive protection process. The finding that ATM is required for the activation of both MEK/ERK and NF-κB, and that it interacts with the NF-κB subunit p65, suggests that an ATM-initiated prosurvival network participates in the LDR-induced adaptive response that is observed in human skin cells.

Experimental procedures

Cells and radiation

The human keratinocyte cell line HK18 was immortalized by transfection with the HVP18 genome. HK18 and the dominant negative mutant of IκB-transfected HK18 (HK18/mIκB) cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone, Logan, UT, USA), penicillin (100 units/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) in a humidified incubator (5% CO2). The culture conditions ensure the growth of HK18 keratinocytes without inducing differentiation or growth arrest. ATM-deficient fibroblasts GM05849 (purchased from Coriell Cell Repositories, Camden, NJ, USA) were maintained in Eagle’s minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics. Exponentially growing cells that reached 70–80% confluence were exposed to ionizing radiation (IR) at room temperature using a Cabinet X-ray System Faxitron Series (dose rate 0.028 Gy/min, 130 kVp; Hewlett Packard, McMinnville, OR, USA) or GR-12 irradiator equipped with a cobalt-60 radiation source (dose rate 2.3 Gy/min; U.S. Nuclear Corp., Burbank, CA, USA). Cells shielded from the IR source were used as a sham-IR control. Radiation sensitivity was measured using both cell proliferation (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide, or MTT) and clonogenic survival assays.

Clonogenic survival assay

The plating efficiency of HK18 cells was determined before clonogenic assays were conducted. Based on the results of plating efficiency, identical numbers of HK18 and HK18/mIκB cells were seeded for each of the treatment groups (10 cGy and 10 cGy+2 Gy) and the control group (sham-IR). Cells were plated into 60-mm cell culture plates and exposed to sham or 10 cGy X-rays and then incubated for 6 h before exposure to 2 Gy γ-rays (GR-12 irradiator). Fourteen days postirradiation, plates were stained with Giemsa solution and colonies ≥3 mm in diameter were counted as surviving colonies and normalized to the clone numbers observed on nonirradiated cells [21,45]. The plating efficiencies for the parental HK18 and HK18/mIκB cells were 18% and 16, respectively. Each experiment was performed in triplicate and repeated at least three times.

Cell viability assay

Exponentially growing HK18 and HK18/mIκB cells were plated at cell densities of 5000 cells per well in 96-well tissue culture plates for 18–24 h. Cells were then exposed to sham or 10 cGy X-rays and incubated for 6 h before exposure to 2 Gy γ-rays. Twenty-four hours postirradiation, cell proliferation was measured by MTT assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated a minimum of three times.

Western blotting

Cells were collected from the 10-cm culture dishes and washed with PBS and lysed on ice in 500 μl of lysis buffer per dish (10 mM Hepes, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 1% NP-40, 1 mM PMSF, 25% glycerol, and 0.2 mM EDTA). Protein concentrations were determined using a BCA Protein Assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Equal aliquots of protein (20 μg/lane) were electrophoresed through 5 or 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel and then transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The blot was first incubated with the appropriate primary antibody at a dilution of 1:200–1000 and then with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary anti-body at a dilution of 1:5000. The ECL system (Amersham Life Science, Arlington Heights, IL, USA) was used to visualize the specific protein. The antibodies to NF-κB p65 and NF-κB p50 and to MEK and phospho-MEK were bought from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY, USA) and Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA), respectively. The antibodies against ERK1/2, p-ERK1/2, p38, p-p38, JNK1, p-JNK, actin, and cyclin D1 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Anti-ATM and anti-p-ATM (Ser-1981) were obtained from Gene Tex (San Antonio, TX, USA) and Rockland (Gilbertsville, PA, USA), respectively.

Chemical inhibitors with or without radiation

The MEK/ERK inhibitors PD98059 and U0126 (Sigma) were dissolved in DMSO. The ATM inhibitors caffeine (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA) and KU-55933 (a generous gift from Dr. David J. Chen at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, TX, USA) were dissolved in acidified water (water:acetic acid 98:2, v/v) and DMSO, respectively. HK18 cells grown to 70–80% confluence in complete growth medium were incubated with vehicle (control) or 50 μM PD98059 or 5 mM caffeine for 2 h and then 10 μM U0126 or KU-55933 for 1 h. Treatments were terminated by replacing the medium with complete medium without inhibitor, and cell pellets were collected at 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, 8 h, and 24 h after exposure to a single dose of 10 cGy X-rays. Cell lysates were prepared from control and inhibitor/IR-treated cells for Western blotting. Inhibitor/IR-treated cells were assessed using a reporter luciferase assay and a clonogenic assay.

Reporter transfection and luciferase activity assay

HK18 and HK18/mIκB cells plated in 24-well plates were cotransfected with the NF-κB luciferase reporter containing an IL-6 promoter region (0.5 μg) [36] along with β-galactosidase reporters (0.05 μg) for a 6-h incubation followed by irradiation with a single dose of 10 cGy X-rays at room temperature. Control cells were sham-irradiated. Luciferase activity was measured at various time intervals postirradiation using 20 μl of total cell lysates and 100 μl of luciferase assay reagent (Promega) as previously described [12,36]. An aliquot of the same cell lysates was used for the measurement of β-galactosidase activity to normalize luciferase activity.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) design and transfection

siRNA designed to target ATM sequence had the sequence 5′-AACATACTACTCAAAGACATT-3′. siRNA was synthesized with the Silencer siRNA construction kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). Cells were seeded to achieve 30–50% confluence. Transfection of siRNA was performed using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in a 24-well dish with antibiotic-free medium for 24 h before transfection with 30 nM siRNA. Scramble RNA duplex (Ambion) was included as control. Inhibition of ATM was determined by Western blotting at 48 h posttransfection. All transfectants were maintained in antibiotic-free complete medium until collection for analysis.

Immunoprecipitation

Whole-cell extracts treated with or without radiation were prepared in lysis buffer containing 10 mM Hepes, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 1% NP-40, 1 mM PMSF, 25% glycerol, and 0.2 mM EDTA. Extracts were centrifuged at 4 °C for 15 min at 12,000 rpm to remove insoluble materials. Before anti-ATM antibody was added to precipitate a specific immunocomplex, extracts were precleared by a 1-h treatment with normal mouse IgG and 20 μl of a 1:1 slurry of protein G–Sepharose beads at 4 °C on a Nutator (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). Immunoprecipitation (4 h at 4 °C) was preceded by 30 min incubation with protein A or G beads. Beads were collected by brief centrifugation, washed four times with 1× PBS buffer containing 137 mM NaCl, boiled in SDS gel loading buffer, fractionated on 5 or 10% SDS–PAGE gel, and then Western blotted using p65 or ATM antibody.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ±SE. Statistical significance among groups was determined using the Student t test and the differences were considered significant at P<0.05.

Results

NF-κB is required for the LDR-induced radioadaptive response in p53-deficient human skin keratinocytes

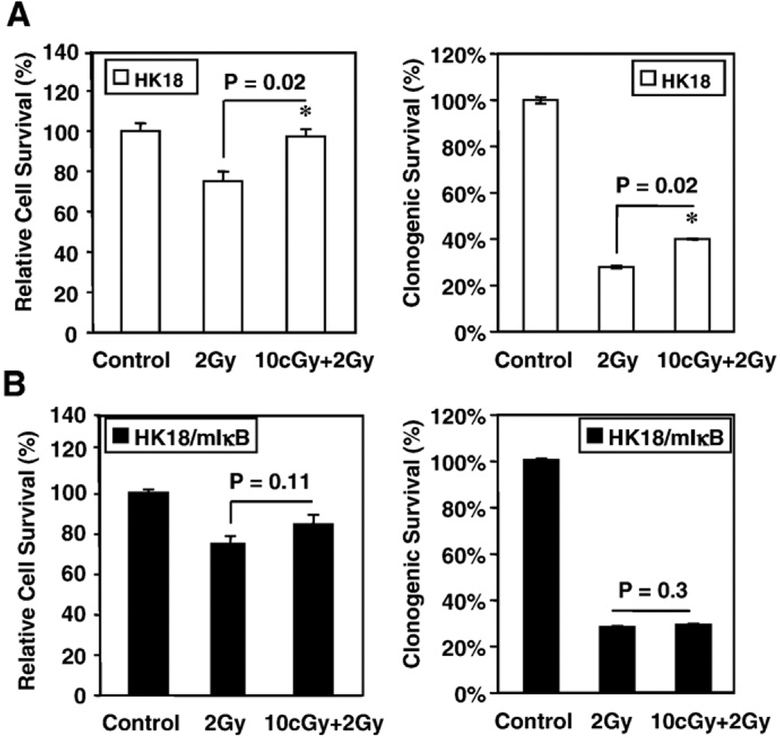

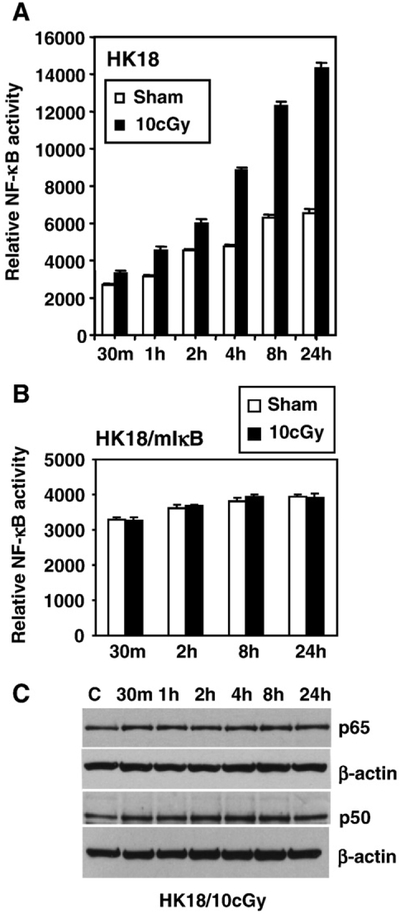

To determine whether NF-κB is involved in the radioadaptive response of human skin cells, we compared the radiosensitivity of an isogenic pair of human skin keratinocytes using HPV18-immortalized wild-type human skin keratinocytes (HK18) versus HK18 stably transfected with mutant IκB to inhibit NF-κB activation (HK18/ mIκB) [37]. Cells were exposed to LDR (10 cGy X-rays) and then incubated for 6 h before exposure to a challenge dose of 2 Gy γ-rays. The 6-h gap after LDR treatment was required to induce the adaptive response in other cell systems [38,39], including our previously reported mouse skin epithelial JB6 cells [12]. Preexposure to LDR significantly enhanced cell survival in wild-type human skin keratinocytes HK18 (Fig. 1A), but failed to induce radioresistance in NF-κB-negative HK18/mIκB cells (Fig. 1B). The potential role of NF-κB activation in this process was further illustrated through the use of a NF-κB-controlled luciferase reporter assay that demonstrated a significant enhancement in activity (Fig. 2A). In contrast, LDR-mediated NF-κB activation was absent from HK18/mIκB cells (Fig. 2B). Moreover, we observed that basal NF-κB activity in the sham-LDR control HK18 cells was increased during the time course of the experiment (Fig. 2A), an effect most likely due to cell proliferation. LDR-treated cells exhibited a significant elevation in NF-κB activity compared to corresponding controls at each time point (Fig. 2A). Immunoblotting results showed a marginally increased p50 level, whereas the NF-κB subunit p65 remained at a relatively constant level 24 h after LDR treatment (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that NF-κB plays an essential role in the radioadaptive response, and the LDR-mediated NF-κB activation in human skin cells is a rapid response that does not involve transcriptional activation of NF-κB subunit genes.

Fig. 1.

NF-κB is involved in LDR-induced radioadaptive response in human skin keratinocytes. (A) Human skin keratinocytes HK18 and (B) HK18/mIκB, the stable transfectants of HK18 cells containing mutant IκB, were irradiated with LDR (10 cGy X-rays) and then incubated for 6 h before exposure to a challenging dose of 2 Gy γ-rays. Cell radiosensitivity was determined by cell proliferation (MTT, left) and clonogenic survival (right) assays after radiation. Cells treated with sham LDR were included as control (n=3/group).

Fig. 2.

NF-κB activation without induction of p65 and p50 in LDR-treated HK18 cells. (A) HK18 and (B) HK18/mIκB cells were cotransfected with the NF-κB luciferase reporter and β-galactosidase reporter for 6 h, and NF-κB luciferase activity was measured at the indicated time points after exposure to sham or a single low dose of 10 cGy X-rays. Luciferase reporter activity was normalized to β-galactosidase (n=3/group). (C) Exponentially growing HK18 cells were irradiated with a single dose of 10 cGy X-rays and NF-κB p50 and p65 levels were measured by Western analysis (C, sham-LDR control; β-actin served as loading control).

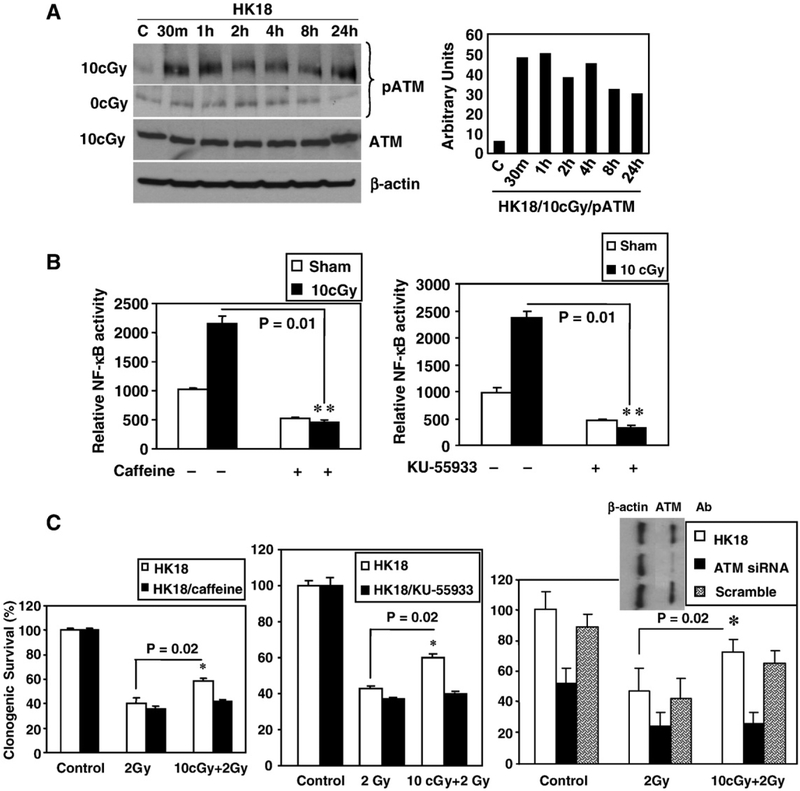

Inhibition of an ATM-blocked, LDR-activated, NF-κB-mediated radioadaptive response

It is known that ATM can play an important role in DNA-damage-induced activation of NF-κB [34]. Western blots were performed to determine whether immediate NF-κB activation by LDR is ATM-dependent. The results showed that a 10-cGy LDR exposure to X-rays induced the phosphorylation of ATM (p-ATM) after 30 min and extended to 24 h postirradiation (Fig. 3A), without affecting total ATM protein levels. To examine whether this LDR-induced ATM phosphorylation was required for NF-κB activation, cells were treated with the ATM inhibitor caffeine (5 mM; for 2 h) before LDR. A complete inhibition of LDR-induced NF-κB activity and adaptive resistance were observed (Fig. 3B). Similar results were obtained with the more specific ATM inhibitor, KU-55933 (10 μM; Fig. 3B, right). The basal activity of NF-κB was moderately reduced by both ATM inhibitors. Suppression of ATM expression by siRNA also eliminated the 10-cGy X-ray-mediated survival advantage after exposure to 2 Gy γ-irradiation (Fig. 3C). These results strongly indicate that ATM plays a critical role in the LDR-induced NF-κB activation and adaptive radioresistance.

Fig. 3.

ATM is required for LDR-induced NF-κB activation and radioadaptive response. (A) LDR-induced ATM phosphorylation (pATM). HK18 cells were irradiated with 10 cGy X-rays; total and phosphorylated ATM (Ser-1981) levels were detected by Western blotting (right shows densitometry data of the relative expression levels of pATM normalized to the expression levels of β-actin; C, sham-LDR control). (B) HK18 cells were cotransfected with NF-κB luciferase and β-galactosidase reporters for 6 h and then incubated with 5 mM caffeine (left) for 2 h or 10 μM KU-55933 (right) for 1 h. Luciferase activity was measured 24 h after exposure to sham-IR or irradiation with a single dose of 10 cGy X-rays and normalized to β-galactosidase (n=3). (C) HK18 cells were treated with caffeine, KU-55933, or ATM siRNA and then exposed to 2 Gy γ-irradiation with or without preexposure to 10 cGy X-rays. Radiosensitivity was determined by clonogenic survival (n=3; inset on the right shows a Western blot of HK18 cells treated with ATM siRNA; Ab, antibody).

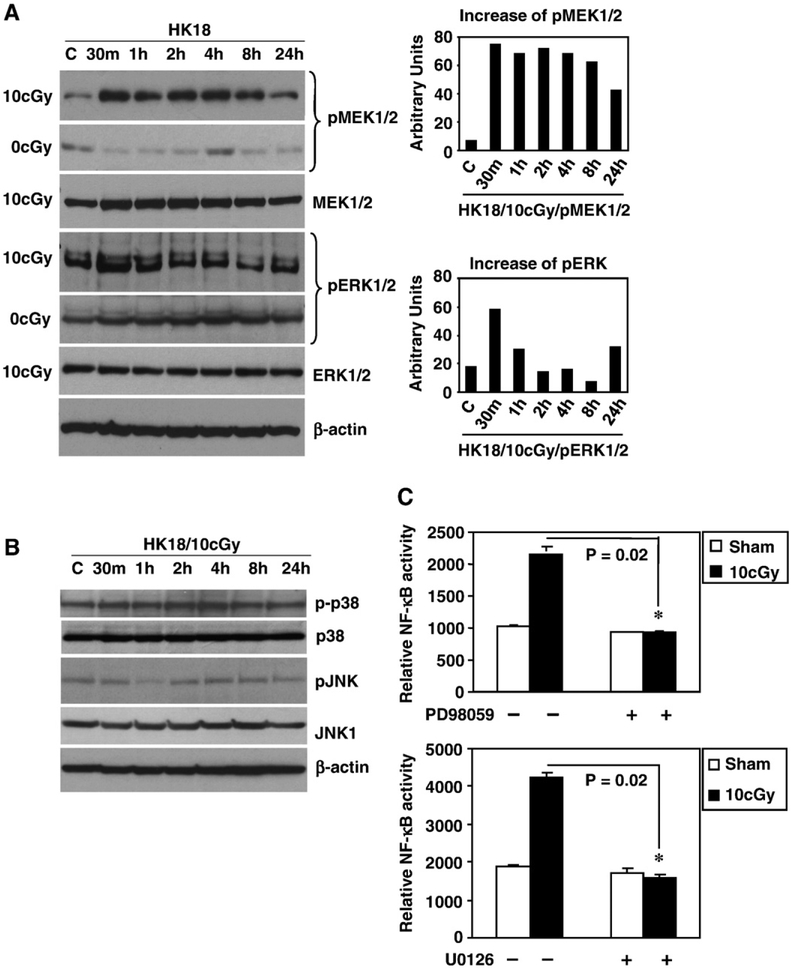

LDR-induced NF-κB activation is mediated through the MEK/ERK pathway

Although the MEK/ERK pathway is linked with NF-κB in a variety of stress-related responses [33], it is unclear whether the LDR-induced adaptive response requires MEK/ERK activation. Fig. 4A shows a striking increase in phosphorylated MEK1/2 detected at 30 min post-LDR (Fig. 4A, top). Phosphorylated ERK1/2, a major substrate of MEK, was also increased. In contrast, phosphorylation of the other two subfamilies of MAPKs, e.g., p38 and JNK, was scarcely affected by LDR (Fig. 4B). These results indicate that LDR-mediated MEK/ERK activation is involved in signaling LDR-mediated adaptive resistance. To determine whether MEK/ERK induction is linked to NF-κB activation, we treated HK18 cells with the MEK/ERK inhibitor PD98059 (Fig. 4C, top) or U0126 (Fig. 4C, bottom) for 2 h before LDR. Both inhibitors completely inhibited the LDR-induced increase in NF-κB activity, suggesting that MEK/ERK is required for NF-κB activation.

Fig. 4.

MEK/ERK activation is required for LDR-induced NF-κB activity. (A) HK18 cells were irradiated with a single dose of 10 cGy X-rays; total and phosphorylated MEK and ERK levels were detected by Western blot at the indicated times. Sham-LDR cells (0 cGy) were collected at the same times as irradiated cells. Right shows densitometry results of p-MEK1/ 2 and p-ERK1/2 normalized to β-actin (C, sham-LDR control, β-actin as a loading control). (B) HK18 cells were treated as in (A), and total and phosphorylated p38 and JNK levels were detected by Western blot. (C) HK18 cells were cotransfected with NF-κB luciferase and β-galactosidase reporters for 6 h and then incubated with 50 μM PD98059 (top) or 10 μM U0126 (bottom) for 2 h, followed by exposure to sham-LDR or a single dose of 10 cGy X-rays. Luciferase reporter activity was measured at 24 h postirradiation and normalized to β-galactosidase (*P=0.02 compared to cells treated with control DMSO; n=3).

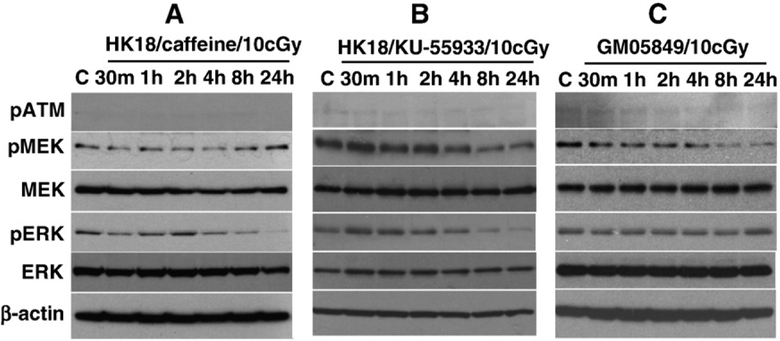

ATM is involved in LDR-induced MEK/ERK activation

The MEK/ERK pathway can be activated by ATM in response to DNA damage [32]. To further understand ATM’s function in LDR-induced activation of MEK/ERK, HK18 cells were incubated with or without the ATM inhibitor caffeine (5 mM) before exposure to a single LDR dose of 10 cGy X-rays. The LDR-mediated MEK/ERK phosphorylation that is described in Fig. 4A was totally eliminated by the addition of caffeine (see Fig. 5A). A similar inhibition was described in HK18 cells treated with the highly specific ATM inhibitor KU-55933 (10 μM, Fig. 5B) and in ATM-null human fibroblasts GM05849 (Fig. 5C). Given that LDR-induced NF-κB activity and MEK/ERK phosphorylation are eliminated by ATM inhibition (Figs. 3B and Fig. 5), we conclude that ATM activation is the initiating event required for a cooperative function between the MEK/ERK/NF-κB pathways that lead to the LDR-induced adaptive response.

Fig. 5.

LDR-induced MEK/ERK phosphorylation was either eliminated by ATM inhibitors or absent from ATM-deficient GM05849 cells. (A) HK18 cells were treated with 5 mM ATM inhibitor caffeine for 2 h or (B) 10 μM KU-55933 for 1 h before exposure to 10 cGy X-rays (C, sham-LDR control). The expression levels of the indicated proteins were detected by Western analysis. No detectable ATM phosphorylation was found in either ATM inhibitor-treated cells (A and B) or (C) the ATM-deficient GM05849 cell line.

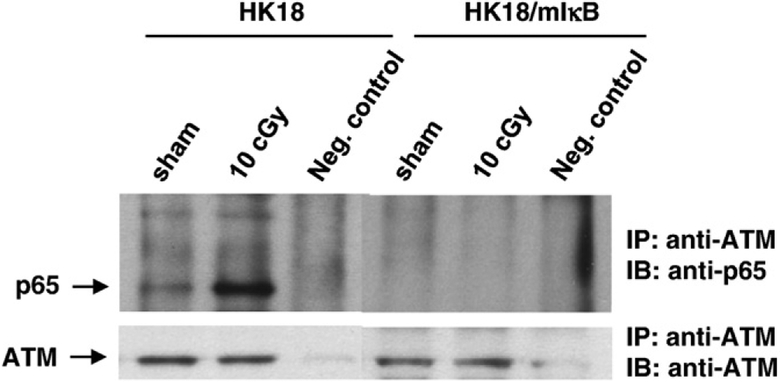

LDR-induced interaction between ATM and NF-κB p65

ATM is shown to directly interact with and phosphorylate specific signaling elements including p53 and BRCA1. Using the p53-inactivated HK18 cells, we questioned whether ATM can directly interact with NF-κB subunits. We found that although a low level of p65/ATM interaction was detectable in sham-irradiated control HK18 cells, a substantial amount of p65/ATM interaction was detected in 10-cGy-treated cells (Fig. 6). No p65/ATM interaction was observed in the NF-κB-inactive HK18 cells that were stably transfected with mIκB (Fig. 6). The blot was also probed with an ATM antibody to ensure that ATM was pulled down in both cell lysates. The results indicate that a p53-independent interaction between ATM and NF-κB p65 present in resting cells can be significantly elevated by the stress induced by low-dose radiation. Because p65 lacks the Ser/Thr-Gln (SQ/TQ) motif that serves as a phosphoacceptor site for ATM kinase, ATM-mediated p65 activation is more likely induced by a direct physical interaction with ATM, which may require an unknown kinase to activate NF-κB. Such a mechanism that accounts for this overriding of the interaction and activation of NF-κB by ATM requires further study.

Fig. 6.

LDR increased ATM/NF-κB p65 complex formation. HK18 and HK18/mIκB cells were irradiated with sham (0 cGy) or 10 cGy X-rays. Whole-cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-ATM antibody followed by immunoblotting (IB) with p65 or ATM antibody. Total lysates extracted from cells treated with 10 cGy and preincubated with ATM antibody served as a negative (Neg.) control.

Discussion

Consistent with previously reported data regarding the adaptive response in mouse skin epithelial cells, we provide additional evidence that exposure to low-dose radiation (10 cGy X-rays) can induce an adaptive radioresistance in human skin keratinocyte cells. Using p53-deficient HK18 cells, the current study further suggests a cooperative function between the DNA-damage sensor protein ATM and stress kinases MEK/ERK along with the transcription factor NF-κB in the development of a low-dose radiation-mediated survival advantage. A novel complex of ATM and NF-κB p65 detected in unirradiated control cells was strikingly increased after exposure to LDR. Expression levels of p65 and p50 were not elevated by LDR and the ATM/p65 complex was not observed in NF-κB-inhibited HK18/ mIκB cells, indicating that the direct interaction between ATM and NF-κB is a predominant feature of LDR-induced NF-κB activation.

Skin is the largest organ in the human body. It is highly susceptible to oxidative stress present in the environment including that induced by exposure to low-dose radiation, which, along with other cytotoxic stress inducers, is a public concern due to its potential risk of gene mutation and carcinogenesis [40]. Accumulating information suggests that exposure to a relatively low level of ionizing radiation can induce a radioadaptive response that leads to a significant reduction of radiation-induced injury. Preexposure of mammalian cells to LDR has been shown to enhance cell growth and survival and, importantly, increase the resistance to radiation-induced carcinogenesis [41,42]. Other reports indicate that human lymphocytes become less susceptible to radiation after exposure to very low doses of X-rays [43]. LDR-induced adaptive radioprotection has also been reported to protect against micronucleus formation and neoplastic transformation in C3H 10T1/2 mouse embryo cells [44,45]. Our present study identifies an adaptive radioprotection that involves the cooperative activation of ATM/ERK/NF-κB pathways induced by a 10-cGy X-ray exposure of human skin keratinocytes (Fig. 1A). Key molecular elements in this adaptive pathway may serve as therapeutic targets with which to mitigate the extent of radiation injury in human skin.

NF-κB is actively involved in signaling responses to oxidative stress and ionizing radiation exposure [4,21]. Several groups have tested the effects of NF-κB inhibitors on cellular radiosensitivity with results that support the concept that NF-κB activity is a necessary element for enhancing cell survival under high-dose radiation [37]. Nontumorigenic cell lines obtained from mouse and human skin epithelial cells are very useful in vitro models for studying skin radioadaptive responses. NF-κB-mediated induction of the mitochondrial antioxidant MnSOD has been previously observed by our group in mouse skin JB6P+ epithelial cells [12]. However, a similar NF-κB-mediated protective function has not been observed in human skin epithelial cells to date. We have reported that NF-κB is responsible for a major portion of the radioresistance observed in the cell population (HK18-IR) derived from human HK18 keratinocytes exposed to fractionated doses of ionizing radiation (2 Gy/fraction; total dose 60 Gy) [37]. Using microarray analysis, a group of stress-responsive genes was found to be activated in HK18-IR cells and about 25% of the up-regulated genes were identified as candidate genes responsive to NF-κB activation. In this study, we show that a single exposure to LDR (10 cGy X-rays) can induce NF-κB-mediated luciferase reporter activity in HK18 cells. However, in contrast to the LDR-induced significant expression of NF-κB subunits in JB6 cells [12], the total protein levels of p65 and p50 were not increased (Fig. 2). These results provide the first evidence that the adaptive response is excluded in the HK18 cells with inactive NF-κB owing to overexpression of mutant IκB (HK18/mIκB), suggesting that NF-κB activation is required for this response. Moreover, the present data demonstrate a potential mechanism that LDR-induced NF-κB activation in human skin cells is mediated via a rapid protein response and that the mode of radiation-induced NF-κB activation varies between human and mouse skin cells.

Another important finding is the observed enhanced phosphorylation of ATM in HK18 cells exposed to LDR (10 cGy X-rays). ATM, a key DNA-damage response protein, plays an essential role in many DNA-damage stress-responsive signaling pathways, including MEK/ERK [46] and NF-κB [47]. Although both ATM and MEK/ERK pathways are shown to be actively involved in the radiation response, their exact function in the LDR-induced radioadaptive response is unknown. We previously reported that ERK phosphorylation down-regulates ATM/ NF-κB-mediated radioresistance in select human breast cancer MCF-7 cells after long-term exposure to therapeutic fractionated doses of radiation [48]. In contrast to these data, this study identifies an ATM-dependent activation of the MEK/ERK pathway after exposure to LDR (Fig. 4). These results provide new evidence that MEK/ERK activity is differentially regulated in human cells (p53-competent breast cancer cells versus p53-inactive keratinocytes) under different stress conditions induced by high or low doses of radiation. The coordinated activation of the ATM/MEK/ERK/NF-κB network by LDR is further supported by the fact that blocking ATM with KU-55933 or caffeine inhibits the phosphorylation of MEK and ERK (Figs. 5A and B). In addition, blocking MEK/ERK activation with PD98059 or U0126 eliminated LDR-induced NF-κB activation (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, the sequence surrounding Ser-218 and Ser-222 within the activation loop domain of MEK fails to meet the criteria of an ATM consensus motif [49]. Therefore, our data cannot confirm a direct activation of the MEK/ ERK pathway by ATM, but rather suggest the involvement of an unknown intermediate kinase(s) that is responsible for MEK phosphorylation in response to LDR. The MEK/ERK pathway is also implicated in NF-κB induction upon ectopic expression of p53 in SAOS osteoblasts [33]. A recent report indicates that activation of NF-κB by DNA damage is induced through the MEK/ERK pathway in p53-null cells in response to doxorubicin treatment [32]. The p53-mediated NF-κB activation after DNA damage is believed to induce a proapoptotic response [33]. Because HK18 cells are p53 inactive [37], this study strongly suggests that ATM-mediated NF-κB activation induces a prosurvival response via the MEK/ERK pathway. Our data also indicate that the DNA-damage sensor protein ATM can form a complex with NF-κB p65 in resting cells and the complex formation can be enhanced by LDR. The possibility that the interaction could be via redox-sensitive modifications of cysteine or methionine residues on the proteins and not phosphorylation events needs to be clarified. Nonetheless, the interaction result suggests an active communication between ATM and NF-κB for enhancing cell survival. In addition, radiation-induced activation of MEK/ERK was ATM-dependent although there is no evidence for a direct interaction between ATM and MEK/ERK. Because the plating efficiency of HK18 cells is low (18%), activation of the ATM/MEK/ERK/NF-κB pathway is expected to occur in a small number of cells capable of forming colonies. This is supported by the fact that siRNA-mediated inhibition of ATM in HK18 cells or NF-κB-inhibited HK18/mIκB cells failed to show a radioadaptive response. The detailed mechanism of the ATM/ERK/NF-κB pathway in radioadaptive cells derived from viable clones after 10 cGy+2 Gy treatment will be determined in future studies.

In summary, this study suggests that an adaptive response can be induced by exposure to 10 cGy X-rays in HPV18-immortalized human skin keratinocytes. Coactivation of the ATM, MEK/ERK, and NF-κB pathways is required for the prosurvival effect exhibited against the cytotoxic effects of 2 Gy γ-irradiation. ATM was found to directly interact with the NF-κB subunit p65 in unirradiated cells, and this interaction was significantly enhanced in irradiated NF-κB wild-type cells but not in NF-κB-inhibited HK18/mIκB cells. Thus, the prosurvival ATM/ERK/NF-κB network in the low-dose radiation-induced radioadaptive response may offer an effective therapeutic approach to enhancing radiation tolerance in human skin cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Shigeki Miyamoto (University of Wisconsin at Madison, WI, USA) for helpful comments and Dr. David Chen (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, TX, USA) for providing the ATM inhibitor KU-55933. This work was supported by Department of Energy Grant DE-FG02–03ER63634 and NIH NCI Grant RO1 101990.

References

- [1].Kelsey KT; Memisoglu A; Frenkel D; Liber HL Human lymphocytes exposed to low doses of X-rays are less susceptible to radiation-induced mutagenesis. Mutat. Res 263:197–201; 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wolff S The adaptive response in radiobiology: evolving insights and implications. Environ. Health Perspect 106 (Suppl. 1):277–283; 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Redpath JL; Short SC; Woodcock M; Johnston PJ Low-dose reduction in transformation frequency compared to unirradiated controls: the role of hyperradiosensitivity to cell death. Radiat. Res 159:433–436; 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Spitz DR; Azzam EI; Li JJ; Gius D Metabolic oxidation/reduction reactions and cellular responses to ionizing radiation: a unifying concept in stress response biology. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 23:311–322; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ahmed KM; Li JJ NF-κB-mediated adaptive resistance to ionizing radiation. Free Radic. Biol. Med 44:1–13; 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Olivieri G; Bodycote J; Wolff S Adaptive response of human lymphocytes to low concentrations of radioactive thymidine. Science 223:594–597; 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Feinendegen LE; Bond VP; Sondhaus CA; Muehlensiepen H Radiation effects induced by low doses in complex tissue and their relation to cellular adaptive responses. Mutat. Res 358:199–205; 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Limoli CL; Kaplan MI; Giedzinski E; Morgan WF Attenuation of radiation-induced genomic instability by free radical scavengers and cellular proliferation. Free Radic. Biol. Med 31:10–19; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ulsh BA; Miller SM; Mallory FF; Mitchel RE; Morrison DP; Boreham DR Cytogenetic dose-response and adaptive response in cells of ungulate species exposed to ionizing radiation. J. Environ. Radioact 74:73–81; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Amundson SA; Do KT; Fornace AJ Jr. Induction of stress genes by low doses of gamma rays. Radiat. Res 152:225–231; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ding LH; Shingyoji M; Chen F; Hwang JJ; Burma S; Lee C; Cheng JF; Chen DJ Gene expression profiles of normal human fibroblasts after exposure to ionizing radiation: a comparative study of low and high doses. Radiat. Res 164: 17–26; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Fan M; Ahmed KM; Coleman MC; Spitz DR; Li JJ Nuclear factor-kappaB and manganese superoxide dismutase mediate adaptive radioresistance in low-dose irradiated mouse skin epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 67:3220–3228; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Li N; Karin M Is NF-kappaB the sensor of oxidative stress? FASEB J.13:1137–1143; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wang T; Zhang X; Li JJ The role of NF-kappaB in the regulation of cell stress responses. Int. Immunopharmacol 2:1509–1520; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ducut Sigala JL; Bottero V; Young DB; Shevchenko A; Mercurio F; Verma M Activation of transcription factor NF-kappaB requires ELKS, an IkappaB kinase regulatory subunit. Science 304:1963–1967; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Li N; Karin M Ionizing radiation and short wavelength UV activate NF-kappaB through two distinct mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:13012–13017; 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lawrence T; Bebien M; Liu GY; Nizet V; Karin M IKKalpha limits macrophage NF-kappaB activation and contributes to the resolution of inflammation. Nature 434:1138–1143; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ahmed KM; Li JJ ATM-NF-kappaB connection as a target for tumor radiosensitization. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 7:335–342; 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kataoka Y; Murley JS; Khodarev NN; Weichselbaum RR; Grdina DJ Activation of the nuclear transcription factor kappaB (NFkappaB) and differential gene expression in U87 glioma cells after exposure to the cytoprotector amifostine. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys 53:180–189; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Jung M; Dritschilo A; NF-kappa B signaling pathway as a target for human tumor radiosensitization. Semin. Radiat. Oncol 11:346–351; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Guo G; Yan-Sanders Y; Lyn-Cook BD; Wang T; Tamae D; Ogi J; Khaletskiy A; Li Z; Weydert C; Longmate JA; Huang TT; Spitz DR; Oberley LW; Li JJ Manganese superoxide dismutase-mediated gene expression in radiation-induced adaptive responses. Mol. Cell. Biol 23:2362–2378; 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wang T; Hu YC; Dong S; Fan M; Tamae D; Ozeki M; Gao Q; Gius D; Li JJ Co-activation of ERK, NF-kappaB, and GADD45beta in response to ionizing radiation. J. Biol. Chem 280:12593–12601; 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Amundson SA; Bittner M; Chen Y; Trent J; Meltzer P; Fornace AJ Jr. Fluorescent cDNA microarray hybridization reveals complexity and heterogeneity of cellular genotoxic stress responses. Oncogene 18:3666–3672; 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sreekumar A; Nyati MK; Varambally S; Barrette TR; Ghosh D; Lawrence TS; Chinnaiyan AM Profiling of cancer cells using protein microarrays: discovery of novel radiation-regulated proteins. Cancer Res. 61:7585–7593; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Amundson SA; Bittner M; Meltzer P; Trent J; Fornace AJ Jr. Induction of gene expression as a monitor of exposure to ionizing radiation. Radiat. Res 156: 657–661; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Meyn MS Ataxia–telangiectasia and cellular responses to DNA damage. Cancer Res. 55:5991–6001; 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bakkenist CJ; Kastan MB DNA damage activates ATM through intermolecular autophosphorylation and dimer dissociation. Nature 421:499–506; 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Westphal CH; Hoyes KP; Canman CE; Huang X; Kastan MB; Hendry JH; Leder P Loss of ATM radiosensitizes multiple p53 null tissues. Cancer Res. 58: 5637–5639; 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Bergmann A; Agapite J; McCall K; Steller H The Drosophila gene hid is a direct molecular target of Ras-dependent survival signaling. Cell 95:331–341; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Impey S; Obrietan K; Storm DR Making new connections: role of ERK/MAP kinase signaling in neuronal plasticity. Neuron 23:11–14; 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kolch W Meaningful relationships: the regulation of the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway by protein interactions. Biochem. J 351 (Pt 2):289–305; 2000. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Panta GR; Kaur S; Cavin LG; Cortes ML; Mercurio F; Lothstein L; Sweatman TW; Israel M; Arsura M ATM and the catalytic subunit of DNA-dependent protein kinase activate NF-kappaB through a common MEK/ extracellular signal-regulated kinase/p90(rsk) signaling pathway in response to distinct forms of DNA damage. Mol. Cell. Biol 24:1823–1835; 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ryan KM; Ernst MK; Rice NR; Vousden KH Role of NF-kappaB in p53-mediated programmed cell death. Nature 404:892–897; 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Wu ZH; Shi Y; Tibbetts RS; Miyamoto S Molecular linkage between the kinase ATM and NF-kappaB signaling in response to genotoxic stimuli. Science 311:1141–1146; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Pei XF; Meck JM; Greenhalgh D; Schlegel R Cotransfection of HPV-18 and v-fos DNA induces tumorigenicity of primary human keratinocytes. Virology 196: 855–860; 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Li JJ; Rhim JS; Schlegel R; Vousden KH; Colburn NH Expression of dominant negative Jun inhibits elevated AP-1 and NF-kappaB transactivation and suppresses anchorage independent growth of HPV immortalized human keratinocytes. Oncogene 16:2711–2721; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Chen X; Shen B; Xia L; Khaletzkiy A; Chu D; Wong JY; Li JJ Activation of nuclear factor kappaB in radioresistance of TP53-inactive human keratinocytes. Cancer Res. 62:1213–1221; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Keyse SM The induction of gene expression in mammalian cells by radiation. Semin. Cancer Biol 4:119–128; 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Le XC; Xing JZ; Lee J; Leadon SA; Weinfeld M Inducible repair of thymine glycol detected by an ultrasensitive assay for DNA damage. Science 280: 1066–1069; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Sowa M; Arthurs BJ; Estes BJ; Morgan WF Effects of ionizing radiation on cellular structures, induced instability and carcinogenesis. EXS (96):293–301; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Feinendegen LE; Bond VP; Sondhaus CA; Altman KI Cellular signal adaptation with damage control at low doses versus the predominance of DNA damage at high doses. C. R. Acad. Sci. Ser III (322):245–251; 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Elmore E; Lao XY; Kapadia R; Giedzinski E; Limoli C; Redpath JL Low doses of very low-dose-rate low-LET radiation suppress radiation-induced neoplastic transformation in vitro and induce an adaptive response. Radiat. Res 169:311–318; 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Shadley JD; Wolff S Very low doses of X-rays can cause human lymphocytes to become less susceptible to ionizing radiation. Mutagenesis 2:95–96; 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Azzam EI; Raaphorst GP; Mitchel RE Radiation-induced adaptive response for protection against micronucleus formation and neoplastic transformation in C3H 10T1/2 mouse embryo cells. Radiat. Res 138:S28–31; 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Klokov D; Criswell T; Leskov KS; Araki S; Mayo L; Boothman DA IR-inducible clusterin gene expression: a protein with potential roles in ionizing radiation-induced adaptive responses, genomic instability, and bystander effects. Mutat. Res 568:97–110; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Suzuki K; Kodama S; Watanabe M Extremely low-dose ionizing radiation causes activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway and enhances proliferation of normal human diploid cells. Cancer Res. 61:5396–5401; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Jung M; Zhang Y; Lee S; Dritschilo A Correction of radiation sensitivity in ataxia telangiectasia cells by a truncated I kappa B-alpha. Science 268:1619–1621; 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Ahmed KM; Dong S; Fan M; Li JJ Nuclear factor-kappaB p65 inhibits mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway in radioresistant breast cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Res 4:945–955; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Kim ST; Lim DS; Canman CE; Kastan MB Substrate specificities and identification of putative substrates of ATM kinase family members. J. Biol. Chem 274:37538–37543; 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]