Abstract

Micro- and nanoscale robots that can effectively convert diverse energy sources into movement and force represent a rapidly emerging and fascinating robotics research area. Recent advances in the design, fabrication, and operation of micro/nanorobots have greatly enhanced their power, function, and versatility. The new capabilities of these tiny untethered machines indicate immense potential for a variety of biomedical applications. This article reviews recent progress and future perspectives of micro/nanorobots in biomedicine, with a special focus on their potential advantages and applications for directed drug delivery, precision surgery, medical diagnosis and detoxification. Future success of this technology, to be realized through close collaboration between robotics, medical and nanotechnology experts, should have a major impact on disease diagnosis, treatment, and prevention.

Introduction

Robotic systems have dramatically extended the reach of human beings in sensing, interacting, manipulating and transforming the world around us (1). Particularly, the confluence of diverse technologies has enabled a revolution in medical applications of robotic technologies towards improving healthcare. While industrial robots were developed primarily to automate routine and dangerous macroscale manufacturing tasks, medical robotic devices are designed for entirely different environments and operations relevant to the treatment and prevention of diseases. Therefore, unlike conventional “old” robots which are built with large mechanical systems, medical robots require miniaturized parts and smart materials for complex and precise operations and mating with the human body. The rapid growth in medical robotics has been driven by a combination of technological advances in motors, control theory, materials, medical imaging and increased in surgeon/patient acceptance (2–4). For example, robotic surgical systems, such as the da Vinci system, allow translation of the surgeon’s hand movements into smaller, precise movements of tiny instruments within the patient’s body. Despite widespread adoption of robotic systems for minimally invasive surgery, there are still major technical difficulties and challenges (4). In particular, the mechanical parts of existing medical robotic devices are still relatively large and rigid to access and treat major previously inaccessible parts of the human body. Designing miniaturized and versatile robots of a few micrometers or less, would allow access throughout the whole human body, leading to new procedures down to the cellular level, and offering localized diagnosis and treatment with greater precision and efficiency. Advancing the miniaturization of robotic systems at the micro- and nanoscales thus holds considerable promise for enhancing the treatment of a wide variety of diseases and disorders (5,6). The development of the micro/nanoscale robots for biomedical applications, which is the focus of this Review, has been supported by recent advances in nanotechnology and materials science, and been driven largely by the demands from the biomedical community.

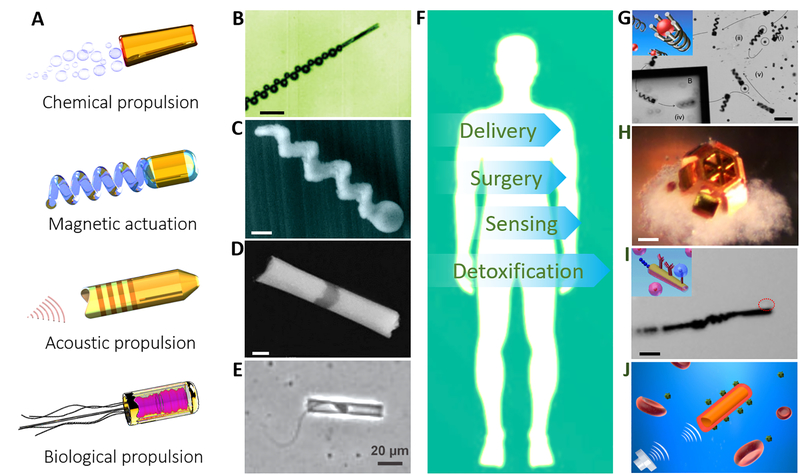

Locomotion represents the first challenge for the miniaturization of robots into micro and nanoscales. When the dimension of the machine is scaled down, the low Reynolds number environment and Brownian motion pose a major challenge to their locomotion (7,8). The design of an efficient nano/microscale machine thus requires a swimming strategy that operates under these low Reynolds number constraints as well as a navigation strategy for overcoming the Brownian motion. As traditional power supplying components and batteries are not possible at these tiny scales, innovative bioinspired design principles are required to meet the challenging powering and locomotion demands. Different types of micro/nanorobots based on distinct actuation principles (Fig. 1A) have been developed in the past decade. Typically, these tiny machines rely on either chemically-powered motors that convert locally supplied fuels to force and movement or externally-powered motors that mostly utilize magnetic and ultrasound energies (and sometime optical, thermal, and electrical energies) to drive their motion (9–20). The fundamental principles of these nanomachines, with rich underlying physics and chemistry, have been discussed in several comprehensive articles (5,9,21–23). Chemically-powered motors can propel themselves through aqueous solution by using surface reactions for generating local gradients of concentration, electrical potential, and gas bubbles (9,21,22). Magnetic swimmers successfully use magnetic actuation to reproduce the motions of natural swimming microorganisms with helical or flexible flagella (5). The proposed propulsion mechanism of acoustic nanomotors suggests that they use asymmetric steady streaming to produce a finite propulsion speed along the axis of the symmetry of the device and perpendicular to the oscillation direction (23). Optical, thermal, and electrical energies can also be harvested to drive the motion of micro/nanostructures with unique principles (24–27). Synthetic micro/nanodevices can also be integrated with motile organisms to build biologically powered hybrid nanorobots (28,29). These different propulsion principles have led to several micro/nanorobotic prototypes, including fuel-powered tubular microrockets (30), magnetically-actuated helical swimmers (31), ultrasound-powered nanowire motors (32), and sperm-powered biohybrid microrobot (33) (Fig. 1B–D).

Fig. 1. Actuation mechanisms and potential biomedical applications of various types of micro/nanorobots.

(A) Typical propulsion mechanisms of micro/nanoscale robots. (B) Chemically powered microrocket (30). Scale bar: 50 μm. (C) Magnetically actuated helical nanoswimmer (31). Scale bar: 200 nm. (D) Acoustically propelled nanowire motor (32). Scale bar: 200 nm. (E) Biologically propelled sperm hybrid microrobot (33). (F) Potential biomedical applications of nanorobots. (G) Magnetic helical microrobot for cargo delivery (38). Scale bar: 50 μm. (H) Micro-grippers for high precision surgery (39). Scale bar: 100 μm. (I) Antibody-immobilized microrobot for sensing and isolating cancer cells (40). Scale bar: 30 μm. (J) Red blood cell (RBC) membrane-coated nanomotor for biodetoxification (41).

Tremendous efforts from the nanorobotic community have greatly improved the power, motion control, functionality versatility, and capabilities of the various micro/nanorobotic prototypes. The growing sophistication of these nano/microscale robots offers great potential for diverse biomedical applications. Many studies have demonstrated that these micro/nanorobots could navigate through complex biological media or narrow capillaries to perform localized diagnosis, remove biopsy samples, take images, and autonomously release their payloads at predetermined destinations. The energy used to actuate these untethered micro/nanorobots does not require any cables, tethers, or batteries. Many of the micro/nanorobots are made of biocompatible materials that can degrade and even disappear upon the completion of their mission. Significantly, the actuation and biomedical function of several micro/nanorobots in a live animal’s body have been carefully characterized in recent studies (34–37). These preliminary in vivo micro/nanorobot operations have demonstrated their enhanced tissue penetration and payload retention capabilities. Such untethered micro/nanorobots represent an attractive alternative to invasive medical robots and passive drug carriers, and are expected to have a major impact on various aspects of medicine. In this review, we summarize potential biomedical applications of micro/nanorobots, as demonstrated in recent proof-of-concept studies, in the following four categories: targeted delivery, precision surgery, sensing of biological targets, and detoxification. Representative examples of such biomedical applications are displayed in Fig. 1F–J (38–41). The immense promise and benefits that these micro/nanorobots bring to the field of biomedicine, along with existing challenges, gaps and limitations, are discussed in the following sections.

Micro/Nanorobots for Targeted Delivery

Existing drug delivery micro/nanocarriers rely on systemic circulation and lack the force and navigation required for localized delivery and tissue penetration beyond their passive mass transport limitation. To achieve precise delivery of therapeutic payloads to targeted disease sites, drug delivery vehicles are desired to possess some unique capabilities, including a propelling force, controlled navigation, cargo-towing and release, and tissue penetration. While these remain unmet challenges for current drug delivery systems, micro/nanorobots represent a new and attractive class of delivery vehicles that can meet these desirable features. The motor-like micro/nanorobots have the potential to rapidly transport and deliver therapeutic payloads directly to disease sites, thereby improving the therapeutic efficacy and reducing systemic side effects of highly toxic drugs.

Numerous initial studies have been conducted to demonstrate the delivery function and performance of these micro/nanorobots in test-tubes and in vitro environments (42–46). For example, Wu et al. reported the preparation of a multilayer tubular polymeric nanomotor encapsulating the anticancer drug doxorubicin via a porous-membrane template-assisted layer-by-layer (LbL) assembly (47). The nanomotor was able to deliver the loaded drug to the vicinity of cancer cells. Ma et al. reported a chemically-powered Janus nanomotor that functioned as an active nanoscale cargo delivery system and enabled a 100% diffusion enhancement when compared to passive targeting without propulsion (48). Mou et al. described a biocompatible drug-loaded magnesium-based Janus micromotor that displayed efficient autonomous motion in simulated body fluid (SBF) or blood plasma (without added fuel) and temperature-triggered release of the drug payload (49). Gao et al. demonstrated the magnetic micromotor vehicle for directed drug delivery by transporting drug-loaded magnetic polymeric particles to HeLa cells (50). Walker et al. recently demonstrated that enzymatically active magnetic micropropellers could effectively penetrate mucin gels (51). Garcia et al. demonstrated that ultrasound-driven nanowire motors could perform rapid drug delivery toward cancer cells followed by a light-triggered release (52). Very recently, Chen et al. reported a hybrid magnetoelectric nanorobotics design for targeted drug delivery, where drug release can also be triggered by magnetic field (53).

The pipeline of developing micro/nanorobots for drug delivery is extremely rich, attested by many emerging systems in the early stages of development. Among these, intracellular delivery represents an active and exciting research area, where the nanorobots penetrate through cellular membranes and directly deliver various therapeutic compounds into the cells. For example, the rapid internalization and movement of ultrasound-powered gold nanowire motors within living cells (54), has been further exploited for accelerated intracellular siRNA delivery (55). These siRNA-loaded nanowires were shown to penetrate rapidly into different cell lines and to dramatically improve the efficiency and speed of gene silencing process as compared to their static nanowire counterparts. Magnetic helical microswimmers have also been used for targeted delivery of pDNA to human embryonic kidney cells (56). The pDNA-loaded motors were steered wirelessly towards the cells and released their genetic cargo into the cells upon contact.

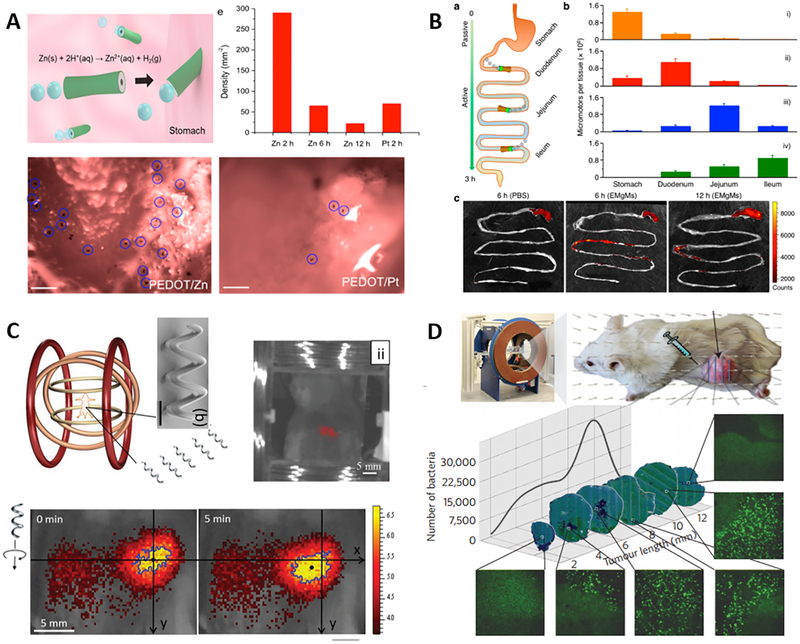

While the majority of these studies have been performed in vitro, initial in vivo studies are already undergoing and have demonstrated encouraging results (34–37,57). Among the various micro/nanorobotic platforms, synthetic motors that are powered by biological fluids such as gastric acid and water are of particular interest for in vivo applications. In addition to efficient propulsion, these motors have the ability to carry a large amount of different cargos, release payloads in a responsive autonomous manner, and eventually degrade themselves to nontoxic byproducts. Recently, Gao et al. conducted the very first in vivo study of chemically-powered micromotors (34). The motors’ distribution, retention, cargo delivery ability and acute toxicity profile in a mouse’s stomach have been evaluated carefully. Using zinc-based micromotors as a model, the acid-driven propulsion in the stomach effectively enhanced the binding and retention of the motors in the stomach wall. The body of the micromotors gradually dissolves in the gastric acid, autonomously releasing their carried payloads, leaving nothing toxic behind (Fig. 2A). Li et al. demonstrated an enteric micromotor capable of precise positioning and controllable retention in desired segments of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract of living mice (Fig. 2B) (35). These motors, consisting of a magnesium-based tubular structure coated with an enteric polymer layer, can act as a robust nanobiotechnology tool for site-specific GI delivery. The in vivo results demonstrate that these motors can safely pass through the gastric fluid and are accurately activated in the GI tract. By simply tuning the thickness of the pH-sensitive polymeric layer, it is possible to selectively activate the propulsion of these motors at desired regions of the GI tract toward localized tissue penetration and retention, without causing noticeable acute toxicity. Very recently, the same team demonstrated that magnesium-based micromotors can autonomously and temporally neutralize gastric acid through efficient chemical propulsion that rapidly depletes localized protons (57). Testing in a mouse model illustrated that such motor-enabled pH change can trigger a responsive payload release. Such pH-neutralizing micromotors can thus combine the functions of proton pump inhibitors and responsive carriers.

Fig. 2. Representative examples of micro/nanorobot-based in vivo delivery.

(A) Acid-powered zinc-based micromotors for enhanced retention in the mouse’s stomach (34). (B) Enteric micromotor, coated with a pH-sensitive polymer barrier (enteric coating) to bypass the acidic stomach environment, to selectively position and spontaneously propel in the gastrointestinal tract (35). (C) Controlled in vivo swimming of a swarm of bacteria-like microrobotic flagella (36). (D) Magneto-aerotactic motor-like bacteria delivering drug-containing nanoliposomes to tumor hypoxic regions (37).

In addition to chemically-powered motors, fuel-free motors powered by external stimuli - such as magnetic or ultrasound fields - also show promise for some important in vivo applications. Servant et al. reported the in vivo imaging and actuation of a swarm of helical microswimmers under rotating magnetic fields in deep tissue (Fig. 2C) (36). Specifically, the magnetically controlled motion of the microswimmers in the peritoneal cavity of an anesthetized mouse was tracked in real time using fluorescence imaging. These results indicate the possibility of using such magnetic motors for optimal delivery of drugs to a targeted site guided by external magnetic field. Moreover, Felfoul et al. demonstrated the use of magneto-aerotactic bacteria, Magnetococcus marinus strain MC-1, to transport drug-loaded nanoliposomes into hypoxic regions of tumors (Fig. 2D) (37). In their natural environment, these bacteria tend to swim along local magnetic field lines and towards low oxygen concentrations. When the MC-1 bacteria bearing the drug-containing nanoliposomes were injected into tumor-bearing mice and magnetically guided towards the tumor, up to 55% of the MC-1 bacteria penetrated into the hypoxic regions of HCT116 colorectal xenograft tumor. Superior penetration depths in xenograft tumors were observed compared to the passive agents. These results suggest that harnessing swarms of microorganisms exhibiting magneto-aerotactic behavior can significantly improve the delivery efficiency of drug nanocarriers to tumor hypoxic regions.

Considering the tremendous progress made recently in the development of micro/nanorobots and their uses toward in vivo delivery, these micro/nanorobots are expected to become powerful active-transport vehicles that may enable a variety of therapeutic applications, which are otherwise difficult to achieve through the exiting passive delivery systems.

Micro/Nanorobots for Precision Surgery

Robotic systems have been introduced for reducing the difficulties associated with complex surgical procedures, and for extending the capabilities of human surgeons. Such robot-assisted surgery is a rapidly evolving field that allows doctors to perform a variety of minimally-invasive procedures with high precision, flexibility and control (58,59). Unlike their large robotic counterparts, tiny robots can potentially navigate throughout human body and operate in many hard-to-reach tissue locations, and hence target many specific health problems.

Recent advances in micro/nanorobots have shown considerable promise for addressing these limitations and for using these tiny devices for precision surgery (3,60). Untethered micro/nanorobotic tools, ranging from nanodrillers to micro-grippers and microbullets (Fig. 3), offer unique capabilities for minimally invasive surgery. With dimensions compatible with those of the small biological entities that they need to treat, micro/nanorobots offer major advantages for high precision minimally-invasive surgery. Powered by diverse energy sources, the moving micro/nanorobots with nanoscale surgical components are able to directly penetrate or retrieve cellular tissues for precision surgery. Unlike their large robotic counterparts, these tiny robots can navigate through the body’s narrowest capillaries and perform procedures down to the cellular level.

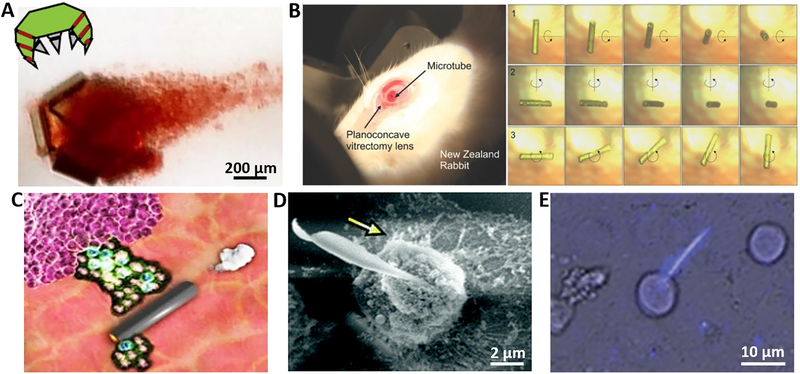

Fig. 3. Representative examples of micro/nanorobot-enabled precision surgery.

(A) Tetherless thermobiochemically-actuated microgrippers capturing live fibroblast cells (17). (B) Electroforming of implantable tubular magnetic microrobots for wireless eye surgery (64). (C) Acoustic droplet vaporization and propulsion of perfluorocarbon-loaded microbullets for tissue ablation (65). (D) Self-propelled nano-driller operating on a single cell (67). (E) Medibots: dual-action biogenic microdaggers for single-cell surgery (69).

Tetherless microgrippers represent an important step towards the construction of autonomous robotic tools for microsurgery (17,61). These mobile microgrippers can capture and retrieve tissues and cells from hard-to-reach places. Conventional microgrippers are usually tethered and actuated by mechanical or electrical signals, generated from control systems, via external connections (e.g., wires, tubes) that restrict their miniaturization and maneuverability. Similar to their large tethered counterparts, the gripping operation of untethered microgrippers commonly involves an opening/closing of the device. Leong et al. have developed a set of responsive microgrippers that can be actuated autonomously by diverse environmental factors and used as minimally invasive microsurgical tools (39). These microgrippers can be mass produced using conventional multilayer photolithography with shapes modeled after biological appendages, in which the jointed digits are arranged in different ways around a central palm (62). By relying on a built-in self-folding actuation response (triggered by their surrounding biological environment), such soft microgrippers obviate the need for external tethers. Different responsive mechanisms - based on temperature, pH, or enzyme stimuli - have been explored for actuating self-folding micro-grippers autonomously in specific environments (63). For example, Fig. 3A illustrates the ability of a tetherless thermobiochemically actuated microgripper to capture a cluster of live fibroblast cells from a dense cell mass in a capillary tube. The microgripper could subsequently move out of the capillary tube with the captured cells in its grasp, demonstrating its strength for performing an in vitro tissue biopsy. The ability to perform additional biomedical functions, such as ablation, has been demonstrated (17).

Magnetically actuated microrobots have also shown considerable promise for minimally-invasive in vivo surgical operations because magnetic fields are capable of penetrating thick biological tissues. Chatzipirpiridis et al. demonstrated that implantable magnetic tubular microrobot was able to perform such surgery at the posterior segment of the eye (Fig. 3B) (64). The electrochemically-prepared microrobot was injected with a 23-gauge needle into the central vitreous humor of the eye and monitored with an ophthalmoscope and integrated camera. Wireless control was used to rotate the intraocular magnetic microrobot around three axes in the vitreous humor of a living rabbit eye. Similar magnetic microtubes can be developed and applied as implantable devices for targeting other diseases in different confined spaces of the human body.

Ultrasound actuation has recently been used to create powerful microrobots with remarkable tissue penetration properties. Kagan et al. demonstrated an ultrasound-triggered high-velocity ‘bullet-like’ propulsion, enabled by the fast vaporization of biocompatible fuel (i.e., perfluorocarbon) (65). Such conically-shaped tubular microbullets, containing the fuel source, display an ultrafast movement with speeds of over 6 m/s (corresponding to 160,000 body lengths per second) in response to an external ultrasound stimulus. Such remarkable speed can provide sufficient thrusts for deep tissue penetration, ablation and destruction (Fig. 3C). Similar acoustically-triggered vaporization of perfluorocarbon fuel was also used for developing tubular microscale cannons capable of loading and firing nanobullets at remarkable speeds (66). These microballistic tools could be used to eject high-speed nanobullets and shoot a wide range of payloads deep into diseased tissues. Recent proof-of-concept studies have demonstrated that the untethered micro/nanorobots can perform surgical operation on a single cell level. Solovev et al. described nanoscale tools in the form of autonomous and remotely guided catalytic InGaAs/GaAs/(Cr)Pt microjets (67). With diameters of 280–600 nm, these self-propelled rolled-up tubes can reach a speed of up to 180 μm/s in hydrogen peroxide solutions. The effective transfer of chemical energy to a translational corkscrew-like motion has allowed these tubes to drill and embed themselves into biological samples such as a single cell (Fig. 3D). While hydrogen peroxide may be incompatible for live cell applications, the same team also described fuel-free rolled-up magnetic microdrillers that could be remotely controlled by a rotational magnetic field (68). The self-folded magnetic microtools with sharp ends enabled drilling and related incision operations of pig liver tissues ex vivo. Srivastava et al. also demonstrated that magnetically-powered microdaggers could create a cellular incision followed by drug release to facilitate highly localized drug administration (Fig. 3E) (69). These studies have demonstrated the great potential of micro/nanorobots for performing precision surgery at the cellular or even subcellular level. The potential of surgical nanorobots will be greatly improved by their ability to penetrate and resect tissues and to sense specific targets, through the choice of propulsion method and use of real-time localization and mapping with a robust control system.

Micro/Nanorobots for Sensing

Owing to their unique features of autonomous motion, easy surface functionalization, effective capture and isolation of target analytes in complex biological media, micro/nanorobots have shown considerable promise for performing various demanding biosensing applications towards precise diagnosis of diseases. The micro/nanorobot sensing strategy relies on the motility of artificial nanomotors, functionalized with different bioreceptors (Fig. 4A), through the sample to realize ‘on-the-fly’ specific biomolecular interactions (12,16). Such receptor-functionalized micro/nanomotors offer powerful binding and transport capabilities that have led to new routes for detecting and isolating biological targets, such as proteins, nucleic acids, and cancer cells, in unprocessed body fluids (32,70–72). The continuous movement of these functionalized synthetic motors leads to built-in solution mixing in microliter clinical samples, which greatly enhances the target binding efficiency and offers major improvements in the sensitivity and speed of biological assays (73). Furthermore, the efficient cargo towing ability of such self-propelled nanomotors, along with their precise motion control within microchannel networks, can lead to new medical diagnostic microchips powered by active transport (74).

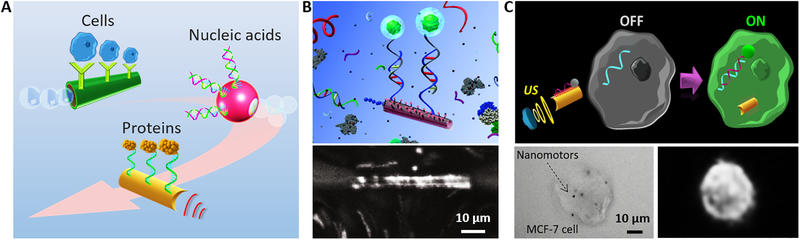

Fig. 4. Strategies and examples of micro/nanorobots for sensing.

(A) Functionalization of micro/nanorobot with different bioreceptors towards biosensing of target analytes, including cells, proteins, and nucleic acids. (B) ssDNA-functionalized microrockets for selective hybridization and isolation of nucleic acids (75). (C) Specific intracellular detection of miRNA in intact cancer cells using ultrasound-propelled nanomotors (80).

Several examples of such bioreceptor-functionalized micro/nanomotors for the detection and isolation of different types of bioanalytes are displayed in Fig. 4B–C. Fig. 4B demonstrates efficient “on-the-fly” DNA hybridization in complex media by using oligonucleotide-probe functionalized micromotors, which allows sensitive and selective detection of nanomolar levels of target DNA sequences (75). A similar strategy using aptamer-functionalized tubular microengines demonstrated the sensitive and selective isolation of thrombin from biological samples (76). Tubular microrockets functionalized with targeting ligands, such as antibodies, offer ‘on-the-fly’ recognition and isolation of specific cancer cells (40). These micromotors provide sufficient propulsive force for efficient transport of the captured target cells in untreated biological media. The micromotor-based target isolation approach can be readily incorporated into lab-on-a-chip diagnostic devices, thus integrating autonomous capture, active transport, release and detection operations within their different reservoirs and narrow microchannels (74,77,78). The significant mixing - induced by the motion of unmodified self-propelled motors - has been shown to greatly enhance analyte–bioreceptor interactions and hence the sensitivity of an immunoassay microarray, as was demonstrated for detecting an Alzheimer biomarker target (79).

Beyond detection and transportation of biological subjects in ambient environments outside of cells, the internalization and movement of nanorobots within cells can also be exploited for intracellular sensing. For example, Esteban et al. introduced an attractive intracellular “Off-On” fluorescence strategy for detecting the endogenous content of target miRNA-21 based on the use of a ultrasound-propelled nanomotor functionalized with ssDNA (Fig. 4C) (80). The presence of the target miRNA resulted in displacement of the dye-ssDNA probe from the surface and a fast fluorescence recovery of the quenched dye-labeled specific ssDNA probe. Such nanomotor biosensing approach could find important applications for profiling miRNAs expression at the single-cell level in a variety of clinical scenarios.

Micro/Nanorobots for Detoxification

Self-propelled micro/nanorobots have been used also as powerful detoxification tools with high cleaning capability. Similar to biosensing, detoxification strategies rely on self-propelled micro/nanorobot that rapidly capture and remove the toxin to render the environment non-toxic. Efficient motion would facilitate the collision and binding of toxins to the motors, which are coated with desired functional materials. For example, nanomotors have been combined with cell-derived natural materials ‒ capable of mimicking the natural properties of their source cells ‒ toward novel nanoscale biodetoxification devices. Among different cell derivatives, red blood cells (RBCs) have shown excellent capability to function as toxin-absorbing nanosponges to neutralize and remove dangerous “pore-forming toxins” (PFTs) from the bloodstream (Fig. 5A) (81). Motivated by the biological properties of RBCs, several different types of cell-mimicking micromotors have been developed for detoxification. Wu et al. presented a cell-mimicking water-powered micromotor based on RBC membrane-coated magnesium microparticles, which were able to effectively absorb and neutralize α-toxin in biological fluids (Fig. 5B) (82). Another detoxification strategy explored the combination of RBC membranes with ultrasound-propelled nanomotors as a biomimetic platform to effectively absorb and neutralize PFTs (41). Another microrobot-based detoxification approach was based on the use of a self-propelled 3D-printed microfish containing polydiacetylene (PDA) nanoparticles (Fig. 5C, top part), which served to attract, capture, and neutralize toxins via binding interactions (83). Self-propelled 3D-microfishes incubated in the toxin solution showed higher fluorescence intensities (Fig. 5C, bottom part) compared to static microfishes, highlighting the importance of active motion for enhancing the detoxification processes.

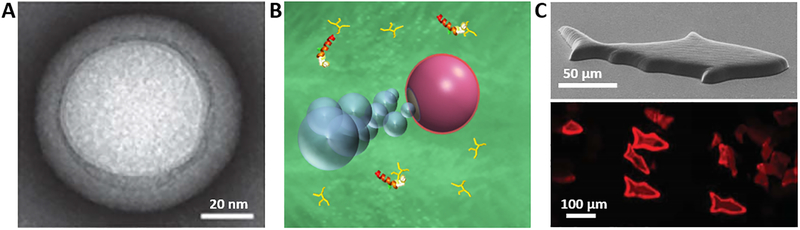

Fig. 5. Representative examples of micro/nanorobots for detoxification.

(A) Transmission electron microscope image of a cell membrane-coated nanosponge used for toxin neutralization (81). (B) Scheme of the RBC-Mg Janus micromotor moving in biological fluid (left), and their capacity for cleanning of α-toxin (82). (C) Scanning electron microscope image of a 3D-printed microfish (top) and fluorescent image of the microfish incubated in melittin toxin solution after swimming (bottom part) (83).

Conclusions, Gaps and Outlook

Over the past decade micro/nanorobotics has emerged as a novel and versatile platform to integrate the advantages of nanotechnologies and robotic sciences. A diverse set of design principles and propulsion mechanisms have thus led to the development of highly capable and specialized micro/nanorobots. These micro/nanorobots possess the unique and multivalent functionalities, including fast motion in complex biological media, large cargo-towing force for directional and long-distance transport, easy surface functionalization for precise capture and isolation of target subjects, and excellent biocompatibility for in vivo operation. These attractive functionalities and capabilities of micro/nanorobots have facilitated biomedical applications, ranging from targeted delivery of payloads and precise surgery on a cellular level to ultra-sensitive detection of biological molecules and rapid removal of toxic compounds. These developments have advanced the micro/nanorobots from chemistry laboratories and test-tubes to whole living systems. Such in vivo studies serve as an important step forward towards clinical translation of the micro/nanorobots.

The ability of micro/nanorobots to address healthcare issues is just in its infancy. Overcoming knowledge gaps in nanorobotics could have a profound impact upon different medical domains. Tremendous efforts and innovations are required for realizing the full potential of these tiny robots for performing complex operations within body locations that were previously inaccessible. Future micro/nanorobots must mimic the natural intelligence of their biological counterparts (e.g., microorganisms and molecular machines) with high mobility, deformable structure, adaptable and sustainable operation, precise control, group behavior with swarm intelligence, sophisticated functions, and even self-evolving and self-replicating capabilities.

A significant challenge is to identify new energy sources for prolonged, biocompatible, and autonomous in vivo operation. Though different chemical fuels and external stimuli have been explored for nanoscale locomotion in aqueous media (8), new alternative fuels and propulsion mechanisms are necessary for safe and sustainable operation in the human body. Most of the catalytic micromotors rely on hydrogen peroxide fuel and hence can only be used in vitro. Micromotors powered by active material propellants (e.g., Mg, Zn, Al, CaCO3) have relatively short lifetimes due to rapid consumption of their propellant during their propulsion. Recent efforts have indicated that enzyme-functionalized nanomotors could be powered by bodily fluid constituents, such as blood glucose or urea (84–86). The power and stability of these enzyme-based motors require further improvements for practical implementation. Magnetic and acoustic nanomotors can provide fuel-free and on-demand speed regulation, which is highly suitable for nanoscale surgery, but may hinder autonomous therapeutic interventions.

Moving nanorobots from test tubes to living organisms would require significant future efforts. The powerful performance of micro/nanorobots has already been demonstrated in viscous biological fluids such as gastric fluid or whole blood (34,35,57,87,88). Operating these tiny devices in human tissues and organs, that impose larger barriers to motion, requires careful examination. Magnetically-powered microswimmers have been successfully actuated in the peritoneal cavity of a mouse using a weak rotating magnetic field of 9 mT (36). Magneto-aerotactic bacteria were able to migrate into tumour hypoxic regions under a focalized directional magnetic field of only 15 G (37). Ultrasound-powered micromotors with powerful ‘ballistic’ capabilities have enabled deep tissue penetration (65). Powering nanorobot within tissues and organs could greatly benefit from their small size. Such “small is better” philosophy has already been verified using nanoscale magnetic propellers, which display a significant advantage for propulsion in viscoelastic hyaluronan gels as they are of the same size range as the openings in the gel’s mesh, compared to the impeded motion of larger propellers (89). These results demonstrate that nanorobots are highly promising for achieving efficient motion in tissues enabled by the nanoscale size and optimized design. The miniaturization advantages of smaller nanorobots have been realized also for overcoming cellular barriers and internalizing into cells (55).

Designing robots to perform tasks at the nanoscale scale is essentially a materials science or surface science problem because the operation and intelligence of tiny robots rely primarily on their materials and surface properties. Biomedical nanorobots are designed for environments involving unanticipated biological events, changing physiological conditions, and soft tissues. Therefore, diverse smart materials, such as biological materials, responsive materials, or soft materials are highly desired to provide the necessary actuation and multi-functionality while avoiding irreversible robotic malfunctions in complex physiologically-relevant body systems. Recent report has shown that the macrophage uptake of rotating magnetic microrobot could be avoided by adjusting the rotational trap stiffness (90). Alternatively, coupling synthetic nanomachines with natural biological materials can minimize undesired immune evasion and biofouling effects experienced in complex biological fluids, leading to enhanced mobility and lifetime in these media (82). Responsive materials are highly desired for designing configurable nanorobots for adaptive operation of micro/nanorobots under rapidly changing conditions. Nanorobots are also desired to be soft and deformable to ensure maneuverability and mechanical compliance to human body and tissues (91,92). Eventually, they should be made of transient biodegradable materials that disappear upon completing their tasks (93). New fabrication and synthesis approaches, such as 3D nanoprinting, should be explored for large-scale, high-quality, and cost-efficient fabrication of biomedical nanorobots. Advancing nanorobots into the next level will thus be accomplished with new smart materials and cutting-edge fabrication techniques.

Biomedical nanorobots are expected to cooperate, with thousands of units moving independently and coordinately to target the disease site. The coordinated action of multiple nanorobots could be used for performing tasks, e.g., effective delivery of large therapeutic payloads or large-scale detoxification processes, which are not possible using a single robot. Though individual navigation and collective behavior of nanorobots have been explored, mimicking the natural intelligence group communication and synchronized coordination, from one to many, is a challenging issue. Advancing the swarm intelligence of nanorobots towards group motion planning and machine learning at the nanoscale is highly important for enhancing their precision treatment capability. Fundamental understanding of “active matter” and related quantitative control theory can guide the realization of such swarming behavior in dynamically changing environments. High-resolution simultaneous localization and mapping of nanorobots in the human body are experimentally difficult using conventional optical microscopy techniques. Future biomedical operation of nanorobots will require their coupling with modern imaging systems and feedback control systems for arbitrary four-dimensional navigation of many-nanorobot systems.

Looking to the future, the development and application of micro/nanorobots in medicine is expected to become a vigorous research area. To realize the full potential of the micro/nanorobots in the medical field, nanorobotic scientists should work more closely with medical researchers for thorough investigations of the behavior and functionality of the robots, including studies on their biocompatibility, retention, toxicity, biodistribution, and therapeutic efficacy. Considering the promising results achieved recently in gastrointestinal delivery and ophthalmic therapies, we strongly encourage nanorobotic scientists to look into the demands and needs of the medical community to design problem-oriented medical device for specific diagnostic or therapeutic functions. Addressing these specific needs will lead to accelerated translation of micro/nanorobots research into practical clinical use. We envision that with close collaboration between the nanorobotic and medical communities, these challenges can be gradually addressed, eventually expanding the horizon of micro/nanorobots in medicine.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Defense Threat Reduction Agency Joint Science and Technology Office for Chemical and Biological Defense (Grant Numbers HDTRA1-13-1-0002 and HDTRA1-14-1-0064) and by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (Award Number R01DK095168).

References

- 1.A roadmap for US robotics: from internet to robotics. 2016. Edition.

- 2.Mack MJ, Minimally invasive and robotic surgery. JAMA 285, 568–572 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beasley RA, Medical robots: current systems and research directions, Journal of Robotics 2012, 401613, 1–14 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alemzadeh H, Iyer RK, Kalbarczyk Z, Leveson N, Raman J, Adverse events in robotic surgery: a retrospective study of 14 years of FDA Data. PLoS ONE 11(4): e0151470 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson BJ, Kaliakatsos IK, Abbott JJ, Microrobots for minimally invasive medicine. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng 12, 55–85 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang J, Gao W, Nano/microscale motors: biomedical opportunities and challenges. ACS Nano 6, 5745–5751 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Purcell EM, Life at Low Reynolds Number. Am. J. Phys 45, 3–11 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang J, Nanomachines: fundamentals and applications. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li J, Rozen I, Wang J, Rocket science at the nanoscale. ACS Nano 10, 5619–5634 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peyer KE, Zhang L, Nelson BJ, Bio-inspired magnetic swimming microrobots for biomedical applications. Nanoscale 5, 1259–1272 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdelmohsen LKEA, Peng F, Tu Y, Wilson DA, Micro- and nano-motors for biomedical applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2, 2395–2408 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guix M, Mayorga-Martinez CC, A. Merkoc,;i, Nano/micromotors in (bio)chemical science applications. Chem. Rev 114, 6285–6322 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palagi S, Mark AG, Reigh SY, Melde K, Qiu T, Zeng H, Parmeggiani C, Martella D, Sanchez-Castillo A, Kapernaum N, Giesselmann F, Wiersma DS, Lauga E, Fischer P, Structured light enables biomimetic swimming and versatile locomotion of photoresponsive soft microrobots. Nat. Mater 15, 647–653 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mei Y, Solovev AA, Sanchez S, Schmidt OG, Rolled-up nanotech on polymers: from basic perception to self-propelled catalytic microengines. Chem. Soc. Rev 40, 2109–2119 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin X, Wu Z, Wu Y, Xuan M, He Q, Self-propelled micro-/nanomotors based on controlled assembled architectures. Adv. Mater 28, 1060–1072 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duan W, Wang W, Das S, Yadav V, Mallouk TE, Sen A, Synthetic nano- and micromachines in analytical chemistry: sensing, migration, capture, delivery, and separation. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem 8, 11–33 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vikram Singh A, Sitti M, Targeted drug delivery and imaging using mobile milli/microrobots: a promising future towards theranostic pharmaceutical design. Curr. Pharm. Des 22, 418–28 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sánchez S, Soler L, Katuri J, Chemically powered micro- and nanomotors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 54, 1414–1444 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang H, Pumera M, Fabrication of micro/nanoscale motors. Chem. Rev 115 (16), 8704–8735 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim K, Guo J, Xu X, Fan DL, Recent progress on man-made inorganic nanomachines. Small 11, 4037–4057 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moran JL, Posner JD, Phoretic self-propulsion. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech 49, 511–40 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang W, Duan W, Ahmed S, Mallouk TE, Sen A, Small power: autonomous nano- and micromotors propelled by self-generated gradients. Nano Today 8, 531–554 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nadal F, Lauga E, Asymmetric steady streaming as a mechanism for acoustic propulsion of rigid bodies. Phys. Fluids 26, 082001 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dai B, Wang J, Xiong Z, Zhan X, Dai W, Li C-C, Feng S-P, Tang J, Programmable artificial phototactic microswimmer. Nat. Nanotechnol 11, 1087–1093 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu M, Zentgraf T, Liu Y, Bartal G, Zhang X, Light-driven nanoscale plasmonic motors. Nat. Nanotechnol 5, 570–573 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan D, Yin Z, Cheong R, Zhu FQ, Cammarata RC, Chien CL, Levchenko A, Subcellular-resolution delivery of a cytokine through precisely manipulated nanowires. Nat. Nanotechnol 5, 545–551 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loget G, Kuhn A, Electric field-induced chemical locomotion of conducting objects. Nat. Comm 2:535 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magdanz V, Guix M, G Schmidt O, Tubular micromotors: from microjets to spermbots. Robot. Biomim 1, 1–10 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hosseinidoust Z, Mostaghaci B, Yasa O, Park B, Vikram Singh A, Sitti M, Bioengineered and biohybrid bacteria-based systems for drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 106, 27–44 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Solovev AA, Mei Y, Bermudez Urena E, Huang G, Schmidt OG, Catalytic microtubular jet engines self-propelled by accumulated gas bubbles. Small 5, 1688–1692 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghosh A, Fischer P, Controlled propulsion of artificial magnetic nanostructured propellers. Nano Lett. 9, 2243–2245 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia-Gradilla V, Orozco J, Sattayasamitsathit S, Soto F, Kuralay F, Pourazary A, Katzenberg A, Gao W, Shen Y, Wang J, Functionalized ultrasound-propelled magnetically guided nanomotors: toward practical biomedical applications. ACS Nano 7, 9232–9240 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Magdanz V, Medina-Sánchez M, Chen Y, Guix M, Schmidt OG, How to improve spermbot performance. Adv. Funct. Mater 25, 2763–2770 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao W, Dong R, Thamphiwatana S, Li J, Gao W, Zhang L, Wang J, Artificial micromotors in the mouse’s stomach: a step toward in vivo use of synthetic motors. ACS Nano 9, 117–123 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li J, Thamphiwatana S, Liu W, Esteban-Ferna'ndez de A'vila B, Angsantikul P, Sandraz E, Wang J, Xu T, Soto F, Ramez V, Wang X, Gao W, Zhang L, Wang J, Enteric micromotor can selectively position and spontaneously propel in the gastrointestinal tract. ACS Nano 10, 9536–9542 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Servant A, Qiu F, Mazza M, Kostarelos K, Nelson BJ, Controlled in vivo swimming of a swarm of bacteria-like microrobotic flagella. Adv. Mater 27, 2981–2988 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Felfoul O,Mohammadi M, Taherkhani S, de Lanauze D, Zhong Xu Y, Loghin D, Essa S, Jancik S, Houle D, Lafleur M, Gaboury L, Tabrizian M, Kaou N, Atkin M, Vuong T, Batist G, Beauchemin N, Radzioch D, Martel S, Magneto-aerotactic bacteria deliver drug-containing nanoliposomes to tumour hypoxic regions. Nat. Nano 137, 1–9 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tottori S, Zhang L, Qiu F, Krawczyk KK, Franco-Obregón A, Nelson BJ, Magnetic helical micromachines: fabrication, controlled swimming, and cargo transport. Adv. Mater 24, 811–816 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leong TG, Randall CL, Benson BR, Bassik N, Sterna GM, Gracias DH, Tetherless thermobiochemically actuated microgrippers. PNAS 106, 703–708 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balasubramanian S, Kagan D, Hu C, Campuzano S, Lobo-Castañon MJ, Lim N, Kang DY, Zimmerman M, Zhang L, Wang J, Micromachine-enabled capture and isolation of cancer cells in complex media. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 50, 4161–4164 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu Z, Li T, Gao W, Xu T, Jurado-Sánchez B, Li J, Gao W, He Q, Zhang L, Wang J, Cell-membrane-coated synthetic nanomotors for effective biodetoxification. Adv. Funct. Mater 25, 3881–3887 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peng F, Tu Y, van Hest JCM, Wilson DA, Self-guided supramolecular cargo-loaded nanomotors with chemotactic behavior towards cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 54, 11662–11665 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu Z, Lin X, Zou X, Sun J, He Q, Biodegradable protein based rockets for drug transportation and light-triggered release. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 250–255 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peters C, Hoop M, Pané S, Nelson BJ, Hierold C, Degradable magnetic composites for minimally invasive interventions: device fabrication, targeted drug delivery, and cytotoxicity tests. Adv. Mater 28, 533–538 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Medina-Sanchez M, Schwarz L, Meyer AK, Hebenstreit F, Schmidt OG, Cellular cargo delivery: toward assisted fertilization by sperm-carrying micromotors. Nano Lett. 16, 555–561 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katuri J, Ma X, Stanton MM, Sánchez S, Designing micro- and nanoswimmers for specific applications. Acc. Chem. Res 50, 2–11 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu Z, Wu Y, He W, Lin X, Sun J, He Q, Self-propelled polymer-based multilayer nanorockets for transportation and drug release. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 52, 7000–7003 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ma X, Hahn K, Sanchez S, Catalytic mesoporous janus nanomotors for active cargo delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc 137, 4976–4979 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mou F, Chen C, Zhong Q, Yin Y, Ma H, Guan J, Autonomous motion and temperature-controlled drug delivery of Mg/Pt-poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) janus micromotors driven by simulated body fluid and blood plasma. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 9897–9903 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gao W, Kagan D, Pak OS, Clawson C, Campuzano S, Chuluun-Erdene E, Shipton E, Fullerton EE, Zhang L, Lauga E, Wang J, Cargo‐towing fuel‐free magnetic nanoswimmers for targeted drug delivery. Small 8, 460–468 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walker D, Käsdorf BT, Jeong H, Lieleg O, Fischer P, Enzymatically active biomimetic micropropellers for the penetration of mucin gels. Sci. Adv 1(11): e1500501 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Garcia-Gradilla V, Sattayasamitsathit S, Soto F, Kuralay E, Yardımcı C, Wiitala D, Galarnyk M, Wang J, Ultrasound-propelled nanoporous gold wire for efficient drug loading and release. Small 10, 4154–4159 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen X-Z, Hoop M, Shamsudhin N, Huang T, Özkale B, Li Q, Siringil E, Mushtaq F, Di Tizio L, Nelson BJ, Pané S, Hybrid Magnetoelectric nanowires for nanorobotic applications: fabrication, magnetoelectric coupling, and magnetically assisted in vitro targeted drug delivery. Adv. Mater 1605458, 1–7 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang W, Li S, Mair L, Ahmed S, Jun Huang T, Mallouk TE, Acoustic propulsion of nanorod motors inside living cells. Angew. Chem 126, 3265–3268 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Esteban-Fernández de Ávila B, Angell C, Soto F, Lopez-Ramirez MA, Baez DF, Xie S, Wang J, Chen Y, Acoustically propelled nanomotors for intracellular siRNA delivery. ACS Nano 10, 4997–5005 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qiu F, Fujita S, Mhanna R, Zhang L, Simona BR, Nelson BJ, Magnetic helical microswimmers functionalized with lipoplexes for targeted gene delivery. Adv. Funct. Mater 25, 1666–1671 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li J, Angsantikul P, Liu W, Esteban-Fernndez de Avila B, Thamphiwatana S, Xu M, Sandraz E, Wang X, Delezuk J, Gao W, Zhang L, Wang J, Micromotors spontaneously neutralize gastric acid for pH-responsive payload release. Angew. Chem 129, 1–7 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lanfranco AR, Castellanos AE, Desai JP, Meyers WC, Robotic surgery a current perspective. Ann. Surg 239, 14–21 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barbash GI, Glied SA, New technology and health care costs — the case of robot-assisted surgery. N. Engl. J. Med 363, 701–704 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ullrich F, Fusco S, Chatzipirpiridis G, Pané S, Nelson BJ, Recent progress in magnetically actuated microrobotics for ophthalmic therapies. Eur. Ophthalmic Rev 8, 120–126 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Diller E, Sitti M, Three-dimensional programmable assembly by untethered magnetic robotic micro-grippers. Adv. Funct. Mater 24, 4397–4404 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gultepe E, Randhawa JS, Kadam S, Yamanaka S, Selaru FM, Shin EJ, Kalloo AN, Gracias DH, Biopsy with thermally-responsive untethered microtools. Adv. Mater 25, 514–519 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Breger JC, Yoon C, Xiao R, Rin Kwag H, Wang MO, Fisher JP, Nguyen TD, Gracias DH, Self-folding thermo-magnetically responsive soft microgrippers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 3398–3405 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chatzipirpiridis G, Ergeneman O, Pokki J, Ullrich F, Fusco S, Ortega JA, Sivaraman KM, Nelson BJ, Pané S, Electroforming of implantable tubular magnetic microrobots for wireless ophthalmologic applications. Adv. Healthcare Mater 4, 209–214 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kagan D, Benchimol MJ, Claussen JC, Chuluun-Erdene E, Esener S, Wang J, Acoustic droplet vaporization and propulsion of perfluorocarbon-loaded microbullets for targeted tissue penetration and deformation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 51, 7519–7522 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Soto F, Martin A, Ibsen S, Vaidyanathan M, Garcia-Gradilla V, Levin Y, Escarpa A, Esener SC, Wang J, Acoustic microcannons: toward advanced microballistics. ACS Nano 10, 1522–1528 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Solovev AA, Xi W, Gracias DH, Harazim SM, Deneke C, Sanchez S, Schmidt OG, Self-propelled nanotools. ACS Nano 28, 1751–1756 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xi W, Solovev AA, Ananth AN, Gracias DH, Sanchez S, Schmidt OG, Rolled-up magnetic microdrillers: towards remotely controlled minimally invasive surgery. Nanoscale 5, 1294–1297 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Srivastava SK, Medina-Sánchez M, Koch B, Schmidt OG, Medibots: dual-action biogenic microdaggers for single-cell surgery and drug release. Adv. Mater 28, 832–837 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Campuzano S, Orozco J, Kagan D, Guix M, Gao W, Sattayasamitsathit S, Claussen JC, Merkoc,; A, Wang J, Bacterial isolation by lectin-modified microengines. Nano Lett. 12, 396–401 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nguyen KV, Minteer SD. DNA-functionalized Pt nanoparticles as catalysts for chemically powered micromotors: toward signal-on motion-based DNA biosensor. Chem. Commun 51, 4782–4784 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yu X, Li Y, Wu J, Ju H, Motor-based autonomous microsensor for motion and counting immunoassay of cancer biomarker. Anal. Chem 86, 4501–4507 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang J, Self-propelled affinity biosensors: moving the receptor around the sample. Biosens. Bioelectron 76, 234–242 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang J, Cargo-towing synthetic nanomachines: towards active transport in microchip devices. Lab Chip 12, 1944–1950 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kagan D, Campuzano S, Balasubramanian S, Kuralay F, Flechsig G, Wang J, Functionalized micromachines for selective and rapid isolation of nucleic acid targets from complex samples. Nano Lett. 11, 2083–2087 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Orozco J, Campuzano S, Kagan D, Zhou M, Gao W, Wang J, Dynamic isolation and unloading of target proteins by aptamer-modified microtransporters. Anal. Chem 83, 7962–7969 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Garcia M, Orozco J, Guix M, Gao W, Sattayasamitsathit S, Escarpa A, Merkoci A, Wang J, Micromotor-based lab-on-chip immunoassays. Nanoscale 5, 1325–1331 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Restrepo-Pérez L, Soler L, Martínez-Cisneros C, Sánchez S, Schmidt OG, Biofunctionalized self-propelled micromotors as an alternative on-chip concentrating system. Lab Chip 14, 2914–2917 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Morales-Narváez E, Guix M, Medina-Sánchez M, Mayorga-Martinez CC, Merkoçi A, Micromotor enhanced microarray technology for protein detection. Small 10, 2542–2548 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Esteban-Fernández de Ávila B, Martin A, Soto F, Lopez-Ramirez MA, Campuzano S, Vasquez-Machado GM, Gao W, Zhang L, Wang J, Single cell real-time miRNAs sensing based on nanomotors. ACS Nano 9, 6756–6764 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hu CJ, Fang RH, Copp J, Luk BT, Zhang L, A biomimetic nanosponge that absorbs pore-forming toxins. Nat. Nanotechnol 8, 336–340 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wu Z, Li J, Esteban-Fernández de Ávila B, Li T, Gao W, He Q, Zhang L, Wang J, Water-powered cell-mimicking janus micromotor. Adv. Funct. Mater 25, 7497–7501 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhu W, Li J, Leong YJ, Rozen I, Qu X, Dong R, Wu Z, Gao W, Chung PH, Wang J, Chen S, 3D-printed artificial microfish. Adv. Mater 27, 4411–4417 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ma X, Jannasch A, Albrecht U-R, Hahn K, Miguel-Lopez A, Schaḟḟ E, Sanchez S, Enzyme-powered hollow mesoporous janus nanomotors. Nano Lett. 15, 7043–7050 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dey KK, Zhao X, Tansi BM, Mendez-Ortiz WJ, Cordova-Figueroa UM, Golestanian R, Sen A, Micromotors powered by enzyme catalysis. Nano Lett. 15, 8311–8315 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Abdelmohsen LKEA, Nijemeisland M, Pawar GM, Janssen G-JA, Nolte RJM, van Hest JCM, Wilson DA, Dynamic loading and unloading of proteins in polymeric stomatocytes: formation of an enzyme-loaded supramolecular nanomotor. ACS Nano 10, 2652–2660 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhao G, Viehrig M, Pumera M, Challenges of the movement of catalytic micromotors in blood. Lab Chip 13, 1930–1936 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lekshmy Venugopalan P, Sai R, Chandorkar Y, Basu B, Shivashankar S, Ghosh A, Conformal cytocompatible ferrite coatings facilitate the realization of a nanovoyager in human blood. Nano Lett. 14, 1968–1975 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schamel D, Mark AG, Gibbs JG, Miksch C, Morozov KI, Leshansky AM, Fischer P, Nanopropellers and their actuation in complex viscoelastic media. ACS Nano 8, 8794–8801 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schuerle S, Avalos Vizcarra I, Moeller J, Selman Sakar M, Özkale B, Machado Lindo A, Mushtaq F, Schoen I, Pané S, Vogel V, Nelson BJ, Robotically controlled microprey to resolve initial attack modes preceding phagocytosis. Sci. Robot 2, eaah6094 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Huang H-W, Selman Sakar M, Petruska AJ, Pane S, Nelson BJ, Soft micromachines with programmable motility and morphology. Nat. Comm 7:12263 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hines L, Petersen K, Zhan Lum G, Sitti M, Soft Actuators for Small-Scale Robotics. Adv. Mater 1603483 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chen C, Karshalev E, Li J, Soto F, Castillo R, Campos I, Mou F, Guan J, Wang J, Transient micromotors that disappear when no longer needed. ACS Nano 10, 10389–10396 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]