Abstract

Background

Mastectomy in male transgender patients is an important (and often the first) step toward physical manhood. At our department, mastectomies in transgender patients have been performed for several decades.

Methods

Recorded data were collected and analyzed for all male transgender patients undergoing mastectomy over a period of 24 years at our department.

Results

In total, 268 gender-reassigning mastectomies were performed. Several different mastectomy techniques (areolar incision, n=172; sub-mammary incision, n=96) were used according to patients’ habitus and breast features. Corresponding to algorithms presented in the current literature, certain breast qualities were matched with a particular mastectomy technique. Overall, small breasts with marginal ptosis and good skin elasticity allowed small areolar incisions as a method of access for glandular removal. In contrast, large breasts and those with heavy ptosis or poor skin elasticity often required larger incisions for breast amputation. The secondary correction rate (38%) was high for gender reassignment mastectomy, as is also reflected by data in the current literature. Secondary correction frequently involved revision of chest wall recontouring, suggesting inadequate removal of the mammary tissue, as well as scar revision, which may reflect intense traction during wound healing (36%). Secondary corrections were performed more often after using small areolar incision techniques (48%) than after using large sub-mammary incisions (21%).

Conclusions

Choosing the suitable mastectomy technique for each patient requires careful individual evaluation of breast features such as size, degree of ptosis, and skin elasticity in order to maximize patient satisfaction and minimize secondary revisions.

Keywords: Transgender, Mastectomy, Gender reassigning surgery

INTRODUCTION

According to the most recent findings published by the German Federal Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection, the official number of registered transgender individuals increased significantly from 400 in 1994 to 1,443 in 2014 with a high estimated number of unreported cases, reflecting the rising importance of gender reassignment surgery [1]. As mastectomy is often the first, and in many cases the only, intervention in sex reassignment surgery for female-to-male (FM) patients, the present study aims at contributing to the comprehension and appreciation of mastectomy in FM patients, which ideally results in a male chest contour with no or minor noticeable female attributes and scar residues. Several surgical techniques have been described, often derived from techniques used for reduction mammaplasty in females or mastectomy to treat gynecomastia in males. Furthermore, in order to support surgeons in their choice of a suitable mastectomy technique, algorithms have been established in terms of individual patients’ breast properties. This study aims at presenting a single-center experience of FM mastectomy over the past 24 years at our institution with regard to the surgical technique selected for the respective anatomical particularities of the breast, glandular resection weight, and acute and secondary revision procedures.

METHODS

Patients

All FM patients who underwent gender reassignment mastectomy at our institution from January 1990 to December 2014 were assessed. The following variables were examined: age, surgical technique, glandular resection weight, acute complications, operative revisions, and secondary corrections. Patients’ consent and ethical review committee approval were obtained (IRB No. FF 99/2017).

Surgical techniques

In total, 172 mastectomies (64%) were performed using an areolar approach, while 96 mastectomies (36%) utilized a sub-mammary approach. Seventy-two mastectomies performed using the areolar incision involved simultaneous excess skin removal and breast lifting, of which 18 mastectomies involved contouring liposuction of the chest wall. One hundred mastectomies performed using an areolar approach were performed without removal of breast skin, of which 22 involved combined liposuction of the chest wall.

Eighty-two mastectomies performed using a sub-mammary approach included en bloc glandular and lipodermal resection, of which four involved liposuction, as compared to 14 mastectomies with glandular removal and preservation of a lipodermal nipple-areolar complex (NAC) pedicle (Table 1).

Table 1.

Frequency of surgical techniques used to perform mastectomy

| Areolar incision (n = 172) | Sub-mammary incision (n = 96) |

|---|---|

| Combined breast lift (n = 72)+liposuction (n = 18) | NAC transplant (n = 82)+liposuction (n = 4) |

| No breast lift (n = 100)+liposuction (n = 22) | Lipodermal NAC pedicle (n = 14)+liposuction (n = 0) |

NAC, nipple-areolar complex.

Of the procedures performed using an areolar incision, 116 involved a peri-areolar incision and 56 involved an intra-areolar incision.

RESULTS

During the study period, 268 mastectomies were performed on 134 patients. In 172 mastectomies, surgical access was performed either at the areola rim or through a trans-areolar incision, whereas in 96 mastectomies, access was obtained through a sub-mammary incision (Table 1).

Resection weight

Resection weight was analyzed in comparison with the current literature (Table 2). Resected glandular specimens were weighed immediately after resection and the average unilateral weight for each patient was calculated. Resection weights were evaluated retrospectively for 172 mastectomies performed at our institution.

Table 2.

Average unilateral mastectomy resection weight from different centers according to different surgical techniques

| Incision for access | Our department | University Medical Centre Amsterdam, Cregten-Escobar et al. [2] | Kaiserswerther Diakonie Düsseldorf, Wolter et al. [3]a) | Ghent University Hospital, Monstrey et al. [4] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Areolar incision without breast lift (g) | 199 (n = 100) | 87 (n = 9) | 122 (n = 48) | 149 (n = 40) |

| Areolar incision with breast lift (g) | 186 (n = 72) | 156 (n = 28) | 130 (n = 66) | 284 (n = 108) |

| Sub-mammary+NAC pedicle (g) | 237 (n = 14) | 231 (n = 47) | 427 (n = 170) | - |

| Sub-mammary+NAC transplant (g) | 629 (n = 82) | 570 (n = 53) | 736 (n = 62) | 550 (n = 36) |

| Sum (g) | 338 (n = 172) | 337 (n = 137) | 353 (n = 346) | - |

NAC, nipple-areolar complex.

Average of right and left resection weights.

Our data showed that the average mastectomy weight per side for the areolar incision technique was 199 g in procedures without breast lifting and 186 g with combined breast lifting. An average resection weight of 237 g was observed for mastectomies with a lipodermal NAC pedicle and an average of 629 g for combined lipodermal and glandular mastectomy with free NAC grafting. The overall average weight of the mastectomy specimens was found to be 338 g (Table 2) [2-4].

Secondary corrections

Secondary corrections were necessary in 38% of performed mastectomies. Predominantly, these corrections included revision of scars and/or chest wall contouring (36%), and to a lesser extent NAC revision (2.2%) (Table 3). In mastectomies using an areolar incision, secondary corrections were required more often (48%) than in procedures using a sub-mammary incision (21%).

Table 3.

Overview and comparison of different surgical centers regarding examined variables and outcome parameters

| Variable | Our department | University Medical Centre Amsterdam, Cregten-Escobar et al. [2] | Kaiserswerther Diakonie Düsseldorf, Wolter et al. [3] | Ghent University Hospital, Monstrey et al. [4] | Tampere University Hospital, Kaariainen et al. [5] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time period | 1990–2014 | 2000–2011 | 2008–2013 | 1991–2003 | 2003–2015 |

| Female-to-male patient | 134 | 202 | 173 | 92 | 57 |

| Mastectomy | 268 | 404 | 346 | 184 | 114 |

| Age (yr) | 29 | 31 | 29 | 31 | NA |

| Areolar incision with breast lift (%) | 37 | 9 | 14 | 22 | 51 (sum) |

| Areolar incision without breast lift (%) | 27 | 21 | 19 | 59 | NA |

| Sub-mammary incision (%) | 36 | 62 | 67 | 20 | 49 |

| +NAC transplant (%) | 31 | 37 | 18 | 20 | 39 |

| +lipodermal NAC pedicle (%) | 5 | 32 | 49 | 0 | 11 |

| Acute revision (%) | 7 | 5 | 10 | 4 | 9 |

| Secondary revision (%) | 38 | 40 | 9 | 32 | 63a) |

| Scar revision and/or chest wall recontouring (%) | 36 | 30 | 7a) | 45 | 42 |

| NAC revision (%) | 2 | 9 | 2 | 13 | 21 |

NAC, nipple-areolar complex; NA, not available.

Average of right and left breasts.

Acute complications

Hemorrhage occurred in 7% of mastectomies performed at our department, and was found to be the main cause of acute surgical revision measures (Table 3) [2-5].

DISCUSSION

Various surgical techniques have been established as a means for performing mastectomy in transgender males within the framework of gender reassignment surgery. Depending on the patients’ breast features, different techniques may be utilized to reach an optimized result. As well as a peri-areolar approach, in which the mastectomy is performed through a key-hole procedure and circular peri-areolar mastopexy is simultaneously possible, a technique involving a large incision in the sub-mammary fold is often an option for patients with larger breast volume, skin excess, or impaired skin elasticity [3,4,6]. The latter may be performed by en bloc resection of lipoepidermal and glandular tissue and combined with a completely new positioning of the NAC through free grafting. Alternatively, excess skin may be deepithelialized leaving a lipodermal pedicle of the NAC, which then may be repositioned accordingly, as has also been described for mastectomy in male patients with gynecomastia by Kornstein and Cinelli [7] as an option that “maintain(s) neovascular integrity and form.” Both large incision techniques result in a horizontal scar within the sub-mammary fold.

Hence, the surgical procedure needs to be adapted to the individual patient and breast anatomy. Different surgical techniques have been utilized to perform mastectomies [8-10], but all techniques have been derived from breast surgery for mammaplasty in female patients or gynecomastia treatment in male patients [11-13].

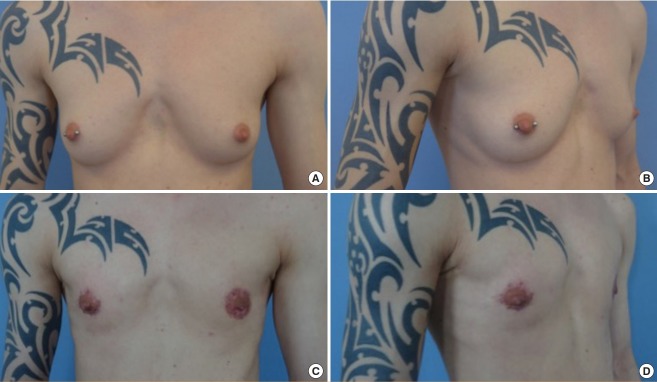

Glandular removal may be performed through a variety of incisions. In small breasts, glandular tissue can be removed through a semi-circular incision at the areolar rim (Fig. 1). Here the glandular tissue is carefully dissected from the surrounding tissue and may be removed on bloc through the semi-circular peri-areolar incision, resulting in minimal scarring. Peri-areolar skin removal may be combined to perform simultaneous lifting of the breast. This minimal incision procedure is challenging due to minimal visual access for gland removal and difficulties involving hemostasis [3].

Fig. 1. A semi-circular incision with periareolar skin removal.

Preoperative images of a transgender male patient with small breasts before mastectomy: frontal view (A) and lateral view (B). Postoperative image of a transgender male patient after mastectomy using the semi-circular incision technique combined with peri-areolar skin removal as a lifting technique: frontal view (C) and lateral view (D).

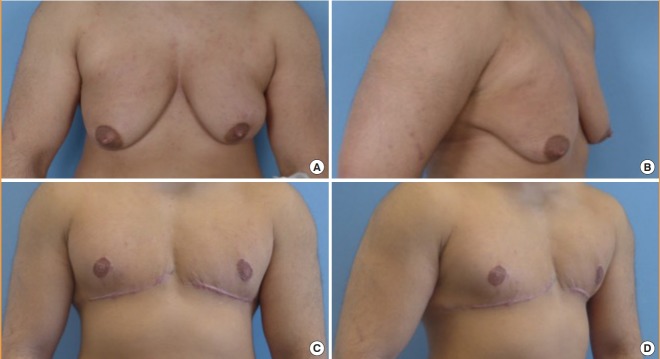

Larger breasts and those with ptosis require larger incisions, which may be achieved by performing a large inframammary incision along the complete width of the caudal breast fold, dissecting the glandular tissue to its cranial, lateral, and medial margins and performing a complete mastectomy including the glandular tissue with overlying skin. The NAC is then repositioned through free grafting [14-16]. This allows a thorough removal of glandular tissue with maximal visual access and safety, but it results in a long inframammary scar, as well as a peri-areolar scar, with a consequent lack of neural innervation of the NAC (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Inframammary incision with free nipple-areola-complex grafting.

Preoperative images of a transgender male patient with large breasts and severe ptosis before mastectomy: frontal view (A) and lateral view (B). Postoperative images of a transgender male patient after mastectomy using the inframammary incision technique combined with free nippleareolar complex grafting: frontal view (C) and lateral view (D).

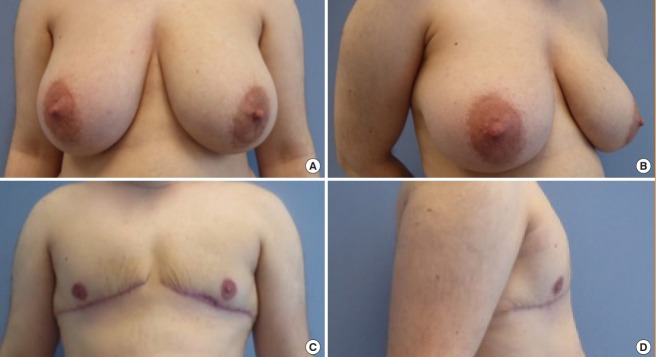

Another method, which also results in the latter scarring pattern, is to leave an inferior pedicled NAC, thereby preserving innervation of the NAC (Fig. 3) [6]. This technique has widely been utilized for female breast reduction [17-20].

Fig. 3. Inframammary incision with inferior pedicled nipple-areola-complex.

Preoperative images of a transgender male patient with large breasts and severe ptosis before mastectomy: frontal view (A) and lateral view (B). Postoperative images of a transgender male patient after mastectomy using the inframammary incision technique combined with inferior pedicled nipple-areolar complex repositioning: frontal view (C) and lateral view (D).

The literature contains several algorithms that allow patient-based decision-making with regards to the surgical technique [2,5,13]. Although slight differences are found between these algorithms, high congruence can be observed overall (Table 4). Thus, small breasts with no or marginal ptosis and overall good skin elasticity are appropriate for areolar access without simultaneous breast skin lifting. Areolar access combined with skin reduction should be considered for medium-sized breasts and those with minimal or moderate ptosis and limited skin elasticity. Combined lipodermal and glandular breast resection or mastectomy with a lipodermal NAC pedicle should be considered for large breasts and those with severe ptosis and/or poor skin elasticity [2,5]. We have found our decision-making process regarding the choice of surgical technique to be consistent with these algorithms, although during the period of data-gathering of the present study a strict algorithm had yet to be established. Furthermore, it should be taken into account that the algorithms presented allow decision-making for optimized results in general, but surgeons will encounter transgender males with breast features not in exact accordance with the established algorithms. These cases benefit from an open and thorough dialogue with the patient regarding the different techniques and the corresponding possible expected outcomes, in order to encourage realistic expectations and to avoid dissatisfaction and disappointment to the extent possible. Furthermore, in our experience, awareness and self-education regarding different mastectomy techniques amongst transgender male patients are widespread. Patients are often well informed about different surgical mastectomy techniques and insist on a specific technique; for instance, they may knowingly opt for a peri-areolar approach despite a high potential risk of requiring revision surgery. In addition, body types are not always easily classified, which makes it difficult to strictly define a single suitable mastectomy technique in terms of a peri-areolar or sub-mammary approach to a certain individual habitus. A blurred transitional zone between different habitus types is not infrequent.

Table 4.

Summary of algorithms according to breast characteristics

| Incision access | University Medical Centre Amsterdam Cregten-Escobar et al. [2] | Kaiserswerther Diakonie Düsseldorf Wolter et al. [3] | Ghent University Hospital Monstrey et al. [4] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Areola incision without skin resection | Small breast (B-cup)+good skin elasticity | Small breast (A-cup)+good skin elasticity, ptosis 0° | Small breast+poor skin elasticity |

| Medium-sized breast (up to B-cup)+good skin elasticity, ptosis I-II° | |||

| Areola incision with skin resection | Medium-sized breast (B-cup)+good skin elasticity | Medium-sized breast (up to B-cup)+moderate/ poor skin elasticity, ptosis I° | Medium-sized breast (B-cup)+poor skin elasticity |

| Small breast+poor skin elasticity | Large breast (C-cup)+moderate skin elasticity | ||

| Sub-mammary (NAC transplant or NAC pedicle) | Medium-sized breast+poor skin elasticity | Large breast (up to D-cup)+moderate/poor skin elasticity, ptosis II° | Large breast (C-cup and above)+poor skin elasticity, ptosis II-III° |

| Large breast (C-cup and above) | D-cup and above+poor skin elasticity, ptosis III° |

NAC, nipple-areolar complex.

Table 3 outlines the differences in outcomes with respect to operative revision frequency in the current literature, as well as an overview of the frequency of the surgical methods used in our study compared to those used by other surgical departments. The differences in outcomes compared to those found in the current literature are small considering the wide range of published data on complication frequency. The occurrence of revisions in our study lies within the range found in the current literature (Table 3).

Several surgical techniques were utilized to perform mastectomy, depending on individual factors, such as breast size and volume, as well as breast skin elasticity and breast ptosis, to obtain the best possible postoperative results. All techniques allow liposuction to be combined as a possible adjunct option for the refinement of chest wall contouring. Additionally, all mastectomy techniques used at our institution allow reshaping and size reduction of the areola in particular. For areolar incision methods, peri-areolar access may be selected and combined with circular peri-areolar reshaping and resizing of the areola, as well as breast lifting through the removal of excess breast skin circularly as described by Benelli [13]. Similarly, trans-areolar access allows reshaping through removal of a central areola area. However, simultaneous breast skin reduction is not possible without creating additional scarring for trans-areolar incisions, and thus it should primarily be performed on patients who do not require simultaneous breast lifting in order to minimize postoperative scarring.

Surgical techniques solely using a peri-areolar incision allow glandular resection with or without skin resection, thereby enabling simultaneous breast lifting without creating additional scarring if performed as described by Benelli [13]. Scarring is held at a minimum, which makes this technique attractive to both patients and surgeons. However, our results show that in procedures using these scar-sparing techniques, secondary corrections were found at a higher rate (48%) than in procedures performed using the sub-mammary incision technique (21%), despite resulting in more visible and greater scarring. By using minimal access techniques, such as an areolar incision, insufficient removal of the mammary gland resulting in a remaining female chest wall contour seems more likely compared to wide-scarring techniques, such as those using a sub-mammary incision to obtain access for glandular removal [16]. Furthermore, skin resection is limited in areolar techniques, as a large amount of circular skin removal may lead to inadequate wound healing, because high circular traction may result in broad, visible, and disturbing scars. For patients with a great excess of skin, but poor skin elasticity, the removal of too little skin may lead to no or incomplete skin retraction, leaving the patient with an “empty”-looking breast that still resembles a female chest. This may explain the higher rate of secondary corrections being required for areolar incision techniques. Furthermore, regarding acute complications, Monstrey et al. [4] found hematoma occurrence to be higher for areolar incisions.

Additionally, sub-mammary access with either combined resection of lipodermal and glandular components and subsequent NAC transplantation, as well as lipodermal NAC pedicle mastectomy, both allow reshaping and size reduction of the areola. In our findings, these two methods were used primarily for large-breasted patients, as reflected by the large average resection weight (Table 2), as well as for patients with severe ptosis and poor skin quality, supporting the algorithms described previously (Table 4). Large-access techniques allow an optimal view of the gland to be removed, which may allow more precise glandular resection and minimize the risk of remnants [4]. However, these techniques result in larger scarring, which may be more noticeable. It has been discussed whether scarring plays an equally important role for FM patients as it does for female patients undergoing breast reduction or mastopexy [4] and the literature as well as the findings of our study indicate that a male chest contour is prioritized above the use of scar-sparing techniques amongst FM patients. Another aspect to consider is NAC sensitivity, which commonly shows incomplete recovery after free NAC grafting, and to a lesser extent also after mastectomy with a NAC pedicle [1]. This should be addressed and taken into consideration preoperatively.

Regarding the data and the timespan analyzed in the presented study, it is important to keep in mind that a strict algorithm had yet to be defined during the study period. At this time, our clinic has implemented the algorithms discussed above in order to obtain optimal results. Additionally, the presented data reflects the experience of a single-center, and hence several surgeons, over a period of 24 years. A strict consistency in the surgeons performing mastectomy cannot be met for this analysis.

As commonly described in the relevant literature, our findings also suggest that hematoma was the main cause for acute surgical revision measures [5]. The literature suggests that hematoma is more frequently found in trans-areolar and semi-circular techniques than in large-access techniques that allow greater exposure [4].

In conclusion, Besides the parameter of breast size, which predominantly determines the operative technique to be selected, surgeons should evaluate and consider skin elasticity as an important factor determining postoperative results and patient satisfaction [4]. The overall frequency of secondary correction measures was high, especially regarding remaining skin excess as well as inadequate scar results, which were found to be the main reasons for secondary revision involving secondary chest wall contouring and scar revision, respectively (Table 3). Remaining skin, and the resultant continued resemblance to a female breast contour or shape, seem to outweigh the length of the scars remaining after large-access surgical methods for FM patients. Hence, the results desired or expected by each individual FM patient and the individual emphasis of male chest wall contouring or low scarring should be addressed explicitly prior to surgery according to the chosen mastectomy method. As stated by Monstrey et al. [4], “…with this group of patients, increasing the length of the scar on a masculine-appearing chest is far preferable to puckering, wrinkling, tethering, and especially excess skin.”

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Hessian State Chamber of Physicians (IRB No. FF 99/2017) and performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consents were obtained.

Patient consent

The patients provided written informed consent for the publication and the use of their images.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: Kühn S, Rieger UM. Data curation: Keval S. Formal analysis: Keval S. Methology: all authors. Project administration: Kühn S, Rieger UM. Visualization: Kühn S, Rieger UM, Kiehlmann M. Writing – original draft: Kühn S. Writing – review & editing: all authors. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed OA, Kolhe PS. Comparison of nipple and areolar sensation after breast reduction by free nipple graft and inferior pedicle techniques. Br J Plast Surg. 2000;53:126–9. doi: 10.1054/bjps.1999.3235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cregten-Escobar P, Bouman MB, Buncamper ME, et al. Subcutaneous mastectomy in female-to-male transsexuals: a retrospective cohort-analysis of 202 patients. J Sex Med. 2012;9:3148–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolter A, Diedrichson J, Scholz T, et al. Sexual reassignment surgery in female-to-male transsexuals: an algorithm for subcutaneous mastectomy. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015;68:184–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monstrey S, Selvaggi G, Ceulemans P, et al. Chest-wall contouring surgery in female-to-male transsexuals: a new algorithm. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:849–59. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000299921.15447.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaariainen M, Salonen K, Helminen M, et al. Chest-wall contouring surgery in female-to-male transgender patients: a one-center retrospective analysis of applied surgical techniques and results. Scand J Surg. 2017;106:74–9. doi: 10.1177/1457496916645964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monstrey SJ, Ceulemans P, Hoebeke P. Sex reassignment surgery in the female-to-male transsexual. Semin Plast Surg. 2011;25:229–44. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1281493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kornstein AN, Cinelli PB. Inferior pedicle reduction technique for larger forms of gynecomastia. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1992;16:331–5. doi: 10.1007/BF01570696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sutcliffe PA, Dixon S, Akehurst RL, et al. Evaluation of surgical procedures for sex reassignment: a systematic review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:294–308. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hage JJ, van Kesteren PJ. Chest-wall contouring in female-to-male transsexuals: basic considerations and review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:386–91. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199508000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hage JJ, Bloem JJ. Chest wall contouring for female-to-male transsexuals: Amsterdam experience. Ann Plast Surg. 1995;34:59–66. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199501000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Webster JP. Mastectomy for gynecomastia through a semicircular intra-areolar incision. Ann Surg. 1946;124:557–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davidson BA. Concentric circle operation for massive gynecomastia to excise the redundant skin. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1979;63:350–4. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197903000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benelli L. A new periareolar mammaplasty: the “round block” technique. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1990;14:93–100. doi: 10.1007/BF01578332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindsay WR. Creation of a male chest in female transsexuals. Ann Plast Surg. 1979;3:39–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGregor JC, Whallett EJ. Some personal suggestions on surgery in large or ptotic breasts for female to male transsexuals. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:893–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson L, Whallett EJ, McGregor JC. Transgender patient satisfaction following reduction mammaplasty. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:331–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2007.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelahmetoglu O, Firinciogullari R, Yagmur C, et al. Combination of Wuringer’s horizontal septum and inferior pedicle techniques to increase nipple-areolar complex viability during breast reduction surgery. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2017;41:1311–7. doi: 10.1007/s00266-017-0933-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mistry RM, MacLennan SE, Hall-Findlay EJ. Principles of breast re-reduction: a reappraisal. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139:1313–22. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000003383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muslu U, Demirez DS, Uslu A, et al. Comparison of sensory changes following superomedial and inferior pedicle breast reduction. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2018;42:38–46. doi: 10.1007/s00266-017-0958-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baslaim MM, Al-Amoudi SA, Hafiz M, et al. The safety, cosmetic outcome, and patient satisfaction after inferior pedicle reduction mammaplasty for significant macromastia. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018;6:e1798. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000001798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]