Abstract

Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex is considered one of the main causes of hospital-acquired infections. Acinetobacter seifertii was recently characterized within this complex and it has been described as an emergent pathogen associated with bacteremia. The emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria, including Acinetobacter sp., is considered a global public health threat and an environmental problem because MDR bacteria have been spreading from several sources. Therefore, this study aimed to characterize an environmental MDR A. seifertii isolate (SAb133) using whole genome sequencing and a comparative genomic analysis was performed with A. seifertii strains recovered from various sources. The SAb133 isolate was obtained from soil of a corn crop field and presented high MICs for antimicrobials and metals. The comparative genomic analyses revealed ANI values higher than 95% of relatedness with other A. seifertii strains than A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex. Resistome and virulome analyses were also performed and showed different antimicrobial resistance determinants and metal tolerance genes as well as virulence genes related to A. baumannii known virulence genes. In addition, genomic islands, IS elements, plasmids and prophage-related sequences were detected. Comparative genomic analysis showed that MDR A. seifertii SAb133 had a high amount of determinants related to antimicrobial resistance and tolerance to metals, besides the presence of virulence genes. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a whole genome sequence of a MDR A. seifertii isolated from soil. Therefore, this study contributed to a better understanding of the genetic relationship among the few known A. seifertii strains worldwide distributed.

Keywords: Acinetobacter seifertii, multidrug-resistant, whole genome sequencing, resistome, virulome

Introduction

Acinetobacter spp. are non-fermenting Gram-negative bacilli (NFGNB) ubiquitous in the environment and considered one of the main causes of hospital-acquired infections. Acinetobacter seifertii was recently characterized as belonging to the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex, which also includes A. calcoaceticus, A. baumannii, Acinetobacter nosocomialis, and Acinetobacter pittii (Nemec et al., 2011, 2015). A. seifertii has been described as an emergent pathogen, being reported in different human infections, including bacteremia (Cayô et al., 2016; Kishii et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2016).

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria, including Acinetobacter sp., carrying antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) have been reported worldwide from different sources, such as soil and water (Hrenovic et al., 2017; Furlan et al., 2018; Higgins et al., 2018; Furlan and Stehling, 2019). Bacterial resistance to antimicrobials has been considered a global public health and an environmental problem since soil and water sources are described as potential reservoirs and disseminators of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria as well as their ARGs, which is worrying (Berendonk et al., 2015).

Besides that, the presence of metals in the environment can co-select antimicrobial-resistant bacteria since efflux systems are a common mechanism for bacterial resistance to heavy metals and to antimicrobials (Seiler and Berendonk, 2012; Wales and Davies, 2015). Due to the importance of emerging environmental pathogens, this study aimed to characterize an environmental MDR A. seifertii isolated from soil and compare it through the whole genome sequencing with previously described A. seifertii strains obtained from different sources (i.e., human, animal, and environment).

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Isolation

Soil samples were collected between 2015 and 2017 from several cities belonging to the five Brazilian regions. For each soil sample, 1 g was added in 5 mL of Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (Oxoid, United Kingdom) and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Then, 100 μL were seeded on MacConkey Agar (Oxoid, United Kingdom) and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Finally, the morphologically different colonies were selected and stocked in LB broth plus 15% glycerol at −80°C. A total of 150 isolates was obtained and identified by sequencing of 16S rDNA (Weisburg et al., 1991). All these isolates have been previously studied and one of them, SAb133 isolate, was identified as A. seifertii and used in this study.

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assay was used to determine the antimicrobial susceptibility profile according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI; M100, 27th ed). The antimicrobials tested were ampicillin-sulbactam, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, ceftazidime cefepime, imipenem, meropenem, gentamicin, tobramycin, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. The pattern of antimicrobial resistance was determined according to Magiorakos et al. (2012).

Metal Tolerance Profile

Metal tolerance profile was determined according to Deredjian et al. (2011) using Trypticase Soy Agar (TSA) diluted 10-fold plus 5, 10, 20, 50 mmol/L of zinc (Zn2+), 0.5, 1, 2, and 5 mmol/L of copper (Cu2+); 9.76 × 10–3, 0.1, 1, and 5 mmol/L of cobalt (Co2+); 10 and 50 μmol/L of mercury (Hg2+); 0.6, 1.25, and 2.5 mmol/L of cadmium (Cd2+); 0.25, 1.25, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 62.5, and 125 mmol/L of selenite (SeO3)2–; 0.25, 1.25, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 62.5, and 125 mmol/L of tellurite (TeO3)2–; 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, and 50 of arsenic (AsO2)–; 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 mmol/L of nickel (Ni2+); 0.05, 0.1, 1, 2, 5, 10, and 15 mmol/L of chromium (Cr2+); 1, 2,5, 5, 7.5, 10, 15, 30, 50, 75, and 100 mmol/L of magnesium (Mg2+). Metal tolerance was considered at the last concentration of bacterial growth.

Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS)

Genomic DNA of SAb133 isolate was extracted using the PuriLinkTM Genomic DNA Mini Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States). Whole genome sequencing was performed using the Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina Inc., EUA) with 250-bp paired-end reads and de novo assembly was performed using SPAdes v.3.9 (Bankevich et al., 2012). The SAb133 genome was annotated using NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline (PGAP) v.3.2 (Tatusova et al., 2016).

Obtaining Genome Data

The full genome annotation of the 11 A. seifertii strains (Table 1) employed in this study for comparative analysis against the prospected A. seifertii SAb133 was downloaded from NCBI GenBank database on 12th August 2019 (Nemec et al., 2015; Roach et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2016; Cerezales et al., 2018). To add contrast in the comparative study were also downloaded the strains A. baumannii AB030 (GenBank accession no. CP009257), A. pittii ATCC 19004 (GenBank accession no. KB849785), A. calcoaceticus DSM 30006 (GenBank accession no. KB849778) and A. nosocomialis 28F (GenBank accession no. CBSD020000001) from the same database in the same date (Loewen et al., 2014).

TABLE 1.

Data of A. seifertii genomes used in this study.

| A. seifertii strains | Source | Sample | Country | Genome size (bp) | GC % | Genes | Proteins | Contigs | GenBank accession no. |

| SAb133a | Environment | Soil | Brazil | 3,882,472 | 38.6 | 3715 | 3566 | 30 | SNSA00000000 |

| KCJK7915 | Environment | Water | United States | 3,950,692 | 38.5 | 3776 | 3621 | 163 | QAYP00000000 |

| KCJK1723 | Cattle | Feces | United States | 3,884,778 | 38.5 | 3649 | 3508 | 120 | LYQI00000000 |

| 1334_ABAU | Human | – | United States | 4,143,123 | 38.6 | 4268 | 3735 | 681 | JVTF00000000 |

| MI421-133 | Human | Catheter | Bolivia | 4,039,753 | 38.5 | 3863 | 3718 | 222 | PHFF00000000 |

| MI30-324 | Human | Abscesse secretion | Bolivia | 4,051,078 | 38.4 | 3842 | 3700 | 113 | PGPD00000000 |

| V1371 | Human | Knee-joint exudate | Bolivia | 3,987,277 | 38.4 | 3932 | 3751 | 261 | PHFG00000000 |

| C917 | Human | Blood | China | 3,900,662 | 38.5 | 3739 | 3681 | 203 | APCT00000000 |

| A354 | Human | Sputum | China | 3,983,262 | 38.5 | 3713 | 3594 | 67 | LFZQ00000000 |

| A360 | Human | Urine | China | 3,948,160 | 38.5 | 3792 | 3632 | 137 | LFZR00000000 |

| A362 | Human | – | China | 4,344,373 | 38.5 | 4125 | 4009 | 114 | LFZS00000000 |

| NIPH973 | Human | Ulcer | Denmark | 4,212,819 | 38.6 | 4180 | 3890 | 26 | APOO00000000 |

aData from this study.

Phylogenetic Analysis

The phylogenetic analyses were conducted based on the bioinformatics workflow performed by Turner et al. (2018). A maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree was drawn based on the full whole-genome sequences annotation available in GenBank to achieve a phylogenetic snapshot of the closed relationship among the A. seifertii strains. Firstly, were captured the single-copy orthologous genes in each strain, including A. baumannii AB030, A. pittii ATCC 19004, A. calcoaceticus DSM 30006, and A. nosocomialis 28F, which were added as out-groups to enhance the power of discrimination in the phylogenetic analysis. The single-copy orthologous genes were identified using the get_homologs pipeline (Contreras-Moreira and Vinuesa, 2013) and choosing as reference genome the first A. seifertii (NIPH973) identified.

The following parameters were selected in the command line options –M, –t, 16, –r NIPH973.gbff -e. The single-copy orthologous search was conducted with the OrthoMCL algorithm (Li et al., 2003) and the orthologous clusters were limited to single-copy orthologous genes present in all 16 genomes. The predicted orthologous clusters were aligned against each other using MUSCLE version 3.8.3 (Edgar, 2004) with default parameters through command line options. The generated alignments were trimmed using trimAl Beta version 1.4 (Capella-Gutiérrez et al., 2009). Next, the quality-processed alignments were concatenated in a one single FASTA file using UNIX command line.

The ML phylogenetic tree was built using the IQ-Tree software version 1.6.10 (Nguyen et al., 2015) based on the concatenated FASTA file as input. Thus, 1.000 ultra-fast bootstraps replicates (Minh et al., 2013) were performed and the best-fit model using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC – TIM2 + F + R10) was determined according to ModelFinder (Kalyaanamoorthy et al., 2017). The phylogenetic tree was visualized using FigTree software version 1.4.4. In regard for possible conflicting phylogenetic signals, a Neighbor-Net phylogenetic network (Bryant and Moulton, 2004) was drawn based on the previous concatenated sequences with SplitsTree software v.4.14.4 (Huson and Bryant, 2006) using default parameters and applying 1.000 bootstraps.

Genome Relatedness and Similarity

The analysis of genetic relatedness among the A. seifertii strains and A. baumannii AB030, A. pittii ATCC 19004, A. calcoaceticus DSM 30006, and A. nosocomialis 28F was performed using the FastANI method that computes the relatedness (Average Nucleotide Identity – ANI) among all orthologous genes in whole-genome sequences, reflecting strains of the same species if they possess ANI ≥95% (Jain et al., 2018). Another way to compare closely related strains is based on the genomic similarity, and to address this aim, all 16 strains were compared through a visual plot of similarity ranging from 90, 96, and 100% using the blast ring image generator tool selecting A. seifertii NIPH973 as reference genome (Alikhan et al., 2011).

Pangenome Analysis and Cloud Genome Determination

The pangenome structure was determined using the get_homologs tool with parameter t = 0 to obtain all orthologous clusters among the nine A. seifertii strains. The constituents of the A. seifertii pangenome were determined: core genome and accessory genomes (shell and cloud) using the script parse_pangenome_matrix.pl. To identify novel putative single-copy regions in these genomes, conceptually related to cloud genome, an accessory composition of the pangenome, the Panseq tool (Laing et al., 2010) was used selecting the “Novel Regions Analysis” pipeline with parameters for minimum region size of 500 bp and percent identity cut-off of 85%, and the A. seifertii NIPH973 was chosen as reference.

The resulting FASTA file containing the DNA sequences of presumptive novel genomic regions of each strain was analyzed on the GO-FEAT platform (Araujo et al., 2018). The output provided by GO-FEAT has comprised the gene ontology (GO) annotation that are categories divided in terms of Molecular Function, Cellular Component and Biological Process (Ashburner et al., 2000). The results regarding novel regions were summarized by biological processes according to GO annotation provided by the GO-FEAT platform.

Whole Genome Sequencing Analysis

Genomic islands were detected using IslandViewer 4 associated with SIGI-HMM algorithm (Waack et al., 2006; Bertelli et al., 2017). Prophage-related sequences were identified using PHAge search tool enhanced release (PHASTER) (Zhou et al., 2011; Arndt et al., 2016). Insertion sequences (ISs) were searched using ISfinder (Siguier et al., 2006). Plasmids were identified using PlasmidFinder 2.0 (Carattoli et al., 2014) and A. baumannii PCR-based replicon typing (AB-PBRT) in silico method (Bertini et al., 2010). Antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) and chromosomal point mutations (CPMs), metal tolerance genes (MTGs), and A. baumannii known virulence genes (ABKVGs) were analyzed using Resfinder 3.1, BacMet database and Virulence Factors database, respectively (Chen et al., 2005; Zankari et al., 2012; Pal et al., 2014). Core genome multi-locus sequence type (cgMLST) was determined using BacWGSTdb (Ruan and Feng, 2016).

Results

Isolate, Resistance Profile to Antimicrobials and Tolerance Profile to Metals

The SAb133 isolate was obtained in 2016 from a soil sample cultivated with corn in Ribeirão Preto City, São Paulo State, Brazil (GPS 21.200133S and 47.872724W). This isolate presented high MICs, being resistant to ampicillin-sulbactam (64 μg/mL), ceftazidime (32 μg/mL), cefotaxime (>256 μg/mL), ceftriaxone (>256 μg/mL), tetracycline (>256 μg/mL), gentamicin (32 μg/mL), and tobramycin (32 μg/mL). The SAb133 isolate was classified as MDR since it presented resistance to ≥1 antimicrobial in ≥3 categories. The SAb133 isolate presented different metal tolerance profiles, including magnesium (>100 mmol/L), arsenic (30 mmol/L), tellurite (6.25 mmol/L), selenite (6.25 mmol/L), copper (5 mmol/L), zinc (5 mmol/L), chromium (2 mmol/L), cobalt (1 mmol/L), nickel (1 mmol/L), and cadmium (0.6 mmol/L).

Genome Sequencing

The draft genome of SAb133 isolate was comprised of 30 contigs totaling of 3,884.033 (2 × 250-bp) paired-end reads reached by a 244× sequencing coverage. A total of 3,566 protein-coding sequences, 69 pseudogenes, 64 tRNAs, 12 rRNAs, and 4 ncRNAs were identified, with GC content of 38.5%. This Whole Genome Shotgun project was deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accession SNSA00000000. The version described in this paper is version SNSA01000000 (Table 1).

Phylogenetic Analyses

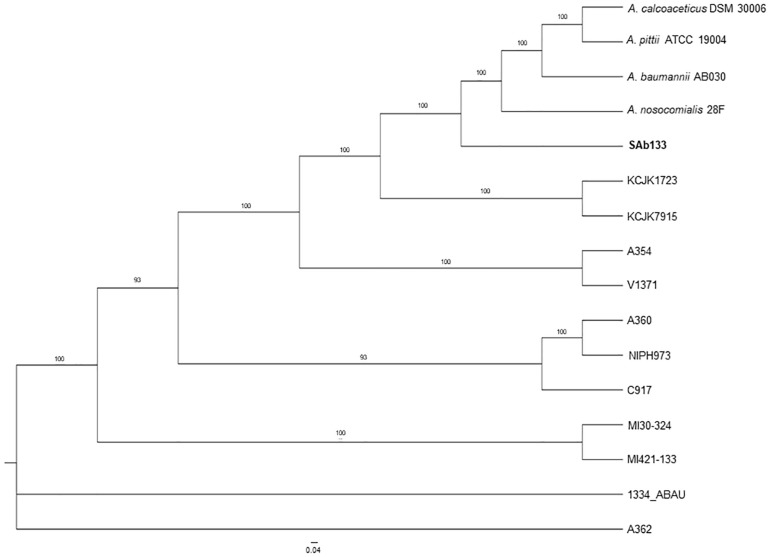

The comparison among the strains pangenomes revealed 2,152 orthologous clusters shared by at least two lineages. These clusters were composed by 59,215 homologous genes (totalizing 1,973,525 bp in length), which were joined end-to-end and concatenated in a unique FASTA file resulting in 73,593 distinct patterns as well as 2,830,60 parsimony-informative sites, 1,749,730 singleton sites and 1,515,492 constant sites used for phylogenetic reconstruction. The ML phylogeny revealed a well-structured dichotomy sand a clear separation in among all the strains (supported by bootstrap values higher than 93%), except for A. seifertii 1334-ABAU and A. seifertii A362 strains, which formed a polytomy. In this analysis, A. baumannii AB030, A. pittii ATCC 19004, A. calcoaceticus DSM 30006 and A. nosocomialis 28F were used as out-groups to improve the power of comparison and their phylogenetic position on the tree showed that the A. seifertii SAb133 strain is closely related to them even it forming a separated clade (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Phylogenetic tree of A. seifertii strains. A maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree representing 12 A. seifertii genomes (i.e., SAb133, KCJK7915, KCJK1723, 1334_ABAU, MI421-133, MI30-324, V1371, A354, A360, A362, C917, and NIPH973), A. baumannii AB030, A. calcoaceticus DSM 30006, A. nosocomialis 28F, and A. pittii ATCC 19004 based on concatenated alignment on 2,739.645 bp. A. seifertii SAb133 was highlighted in bold.

It was also observed that the A. seifertii SAb133 strain appears to be a transition between the A. seifertii clade and A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii clade strains since it forms an intermediate group among the strains belonging to these taxa, being evolutively near to A. baumannii AB030 and the A. seifertii KCJK1723 and A. seifertii KCJK7915 taxa (Figure 1). At the same time, since the tree ramifications were sorted by increase of evolutive distances (mutation rates), the A. seifertii SAb133 strain presented as the lowest derivate strain, being the A. seifertii MI30-324 and A. seifertii MI421-133 the most derivate strains inside the A seifertii species. Unfortunately, for the A. seifertii 1334-ABAU and A. seifertii A360 strains there were not enough phylogenetic signals to uncover their phylogenetic position on the tree, justifying the polytomic position of these two A. seifertii strains on the tree (Figure 1).

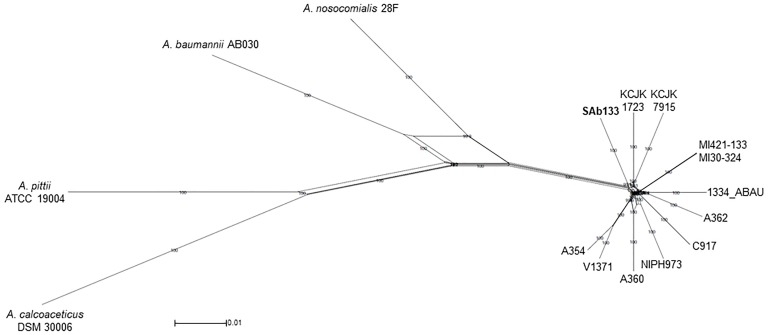

The same concatenated joined end-to-end 1,973,525 bp sequences were used to build a distance-based network using Neighbor-net algorithm. The topology of the network was an equal angle tree that supported the ML tree revealing a close relationship among A. seifertii SAb133 and the other strains (i.e., A. seifertii KCJK1723 and A. seifertii KCJK7915) as already inferred by phylogenetic analysis. Similarly, A. baumannii AB030, A. pittii ATCC 19004, A. calcoaceticus DSM 30006 and A. nosocomialis 28F strains were over again arranged as external groups (Figure 2). In addition, the proximity of clades of the A. seifertii SAb133 and A. seifertii A354/V1371, and A. seifertii MI30-324/MI421-133 to the A. seifertii 1334-ABAU was not coherent to the ML phylogenetic tree obtained (Figures 1, 2). This may indicate that possible conflicting signals shall be present among these strains (i.e., as differential evolutive rates or independent horizontal gene transfer events), which confound the phylogenetic history reconstruction.

FIGURE 2.

Neighbor-Net phylogenetic network of A. seifertii strains. A Neighbor-Net phylogenetic network representing 12 A. seifertii genomes (i.e., SAb133, KCJK7915, KCJK1723, 1334_ABAU, MI421-133, MI30-324, V1371, A354, A360, A62, C917, and NIPH973), A. baumannii AB030, A. calcoaceticus DSM 30006, A. nosocomialis 28F and A. pittii ATCC 19004 based in the concatenated alignment on 2,739.645 bp. A. seifertii SAb133 was highlighted in bold.

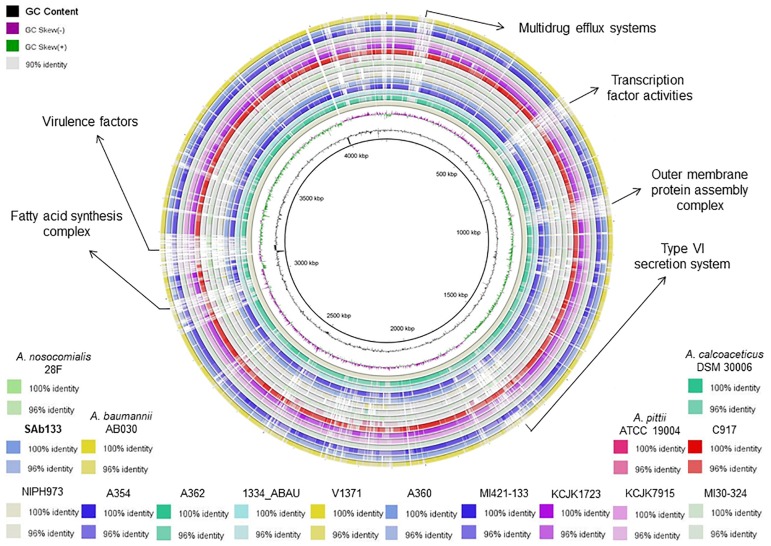

Genome Similarity

The ANI values among coding regions of the 12 A. seifertii strains were higher than 95% with little variations related to the strain-specific features that confer unique traits to a given strain. The comparison with A. baumannii AB030, A. pittii ATCC 19004, A. calcoaceticus DSM 30006 and A. nosocomialis 28F strains enhanced the differentiation of A. seifertii strains relatedness from bacteria belonging to A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex (Table 2). A Blasmap was constructed for visualizing the synonymy in ANI values between those strains and the map showed the high degree of synonymy between A. seifertii strains and the non-synonymy among the A. seifertii strains and A. baumannii AB030, A. pittii ATCC 19004, A. calcoaceticus DSM 30006 and A. nosocomialis 28F strains. Some hypervariable genomic regions were also detected, such as multidrug efflux pumps, transcription factor activities, outer membrane protein assembly complex, type VI secretion system, fatty acid synthesis complex and virulence factors (Figure 3).

TABLE 2.

ANI values among Acinetobacter sp.

| Strains | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) | (15) | (16) | |

| (1) | A. baumannii AB030 | ∗ | |||||||||||||||

| (2) | A. calcoaceticus DSM 30006 | 87.15 | ∗ | ||||||||||||||

| (3) | A. nosocomialis 28F | 91.96 | 87.22 | ∗ | |||||||||||||

| (4) | A. pittii ATCC 19004 | 88.84 | 90.17 | 88.45 | ∗ | ||||||||||||

| (5) | 1334_ABAU | 90.27 | 87.56 | 92.19 | 88.77 | ∗ | |||||||||||

| (6) | A354 | 90.29 | 87.37 | 92.13 | 88.63 | 97.05 | ∗ | ||||||||||

| (7) | A360 | 90.26 | 87.47 | 92.08 | 88.74 | 96.75 | 97.21 | ∗ | |||||||||

| (8) | A362 | 90.25 | 87.37 | 92.43 | 88.68 | 97.11 | 96.94 | 96.73 | ∗ | ||||||||

| (9) | C917 | 90.38 | 87.53 | 92.23 | 88.73 | 96.79 | 96.84 | 96.68 | 96.94 | ∗ | |||||||

| (10) | KCJK1723 | 90.21 | 87.57 | 92.04 | 88.78 | 97.01 | 96.79 | 96.66 | 96.96 | 96.75 | ∗ | ||||||

| (11) | KCJK7915 | 90.28 | 87.51 | 92.11 | 88.71 | 96.93 | 96.74 | 96.73 | 96.99 | 96.66 | 97.19 | ∗ | |||||

| (12) | MI30-324 | 90.39 | 87.51 | 92.16 | 88.86 | 97.09 | 96.97 | 96.82 | 97.13 | 96.91 | 97.06 | 96.93 | ∗ | ||||

| (13) | MI421-133 | 90.45 | 87.51 | 92.20 | 88.86 | 97.07 | 96.92 | 96.84 | 97.12 | 96.91 | 97.05 | 96.95 | 99.95 | ∗ | |||

| (14) | NIPH973 | 90.25 | 87.42 | 92.01 | 88.69 | 96.93 | 96.89 | 96.94 | 96.78 | 96.76 | 96.93 | 96.78 | 96.96 | 96.97 | ∗ | ||

| (15) | SAb133 | 90.34 | 87.57 | 92.25 | 88.85 | 96.78 | 97.01 | 96.83 | 96.82 | 96.83 | 96.90 | 96.79 | 96.77 | 96.77 | 96.73 | ∗ | |

| (16) | V1371 | 90.32 | 87.45 | 92.17 | 88.69 | 96.94 | 98.49 | 97.26 | 96.86 | 96.87 | 96.81 | 96.85 | 96.96 | 96.97 | 96.81 | 97.02 | ∗ |

The values in bold show >95% threshold for species assignment. The asterisk (∗) indicates 100% of similarity as the genomes.

FIGURE 3.

Blastmap comparison of A. seifertii strains. A circular comparison of 12 A. seifertii genomes (i.e., SAb133, KCJK7915, KCJK1723, 1334_ABAU, MI421-133, MI30-324, V1371, A354, A360, A362, C917, and NIPH973), A. baumannii AB030, A. calcoaceticus DSM 30006, A. nosocomialis 28F and A. pittii ATCC 19004. The genomes and sequence similarity (100, 96, and 90%) are demonstrated in different colors. A. seifertii NIPH973 was used as reference genome and A. seifertii SAb133 was highlighted in bold.

Constitution of Pangenomes

The pangenome analysis among the 12 A. seifertii strains (Table 1) returned 6,522 orthologous clusters that are representing the A. seifertii pangenome’s constitution. In the light of these definitions, from the 6,522 orthologous clusters, a total of 2,860 soft-core genes, 2,458 core genes, 2,722 cloud genes, and 940 shell genes were characterized. Novel genomic regions related to biological processes category were detected in A. seifertii strains cloud genomes, such as drug transmembrane transport (i.e., C917, A362, and KCJK1723 – 25% of prevalence), siderophore transport (i.e., 1334-ABAU, A354, and A362 – 25% of prevalence), efflux transmembrane transporter activity (i.e., C917 and KCJK 1723 – 17% of prevalence), and β-lactamase activity and β-lactam antibiotic catabolic process (SAb133 strain only – 8,3% of prevalence). In addition, since the biological process “DNA restriction-modification systems” was found in at least 50% of the strains (i.e., SAb133, C917, 1334-ABAU, A354, A360, A362, and V1371), this process may be more related to the shell genome composition than a cloud genome metabolic process.

Genomic Islands and Phage-Related Sequences

Acinetobacter seifertii SAb133 presented 15 genomic islands ranged in size from 4237 bp to 32680 bp (average 7928 ± 7153 bp). The largest genomic island (32680 bp) identified in A. seifertii SAb133 was related to virulence and antimicrobial resistance mechanisms (Supplementary Table S1). No Phage-related sequence was detected in A. seifertii SAb133 and the other A. seifertii strains had at least one region containing Phage-related sequence, except the KCJK7915 (Supplementary Table S2). Eight genomic islands containing Phage-related sequences were interspersed throughout the genomes of A. seifertii strains (Supplementary Table S1).

Resistome, Virolome and Mobile Elements

Resistome analysis showed antimicrobial resistance genes for β-lactams (blaADC–25 and blaTEM) and multidrug efflux systems (RND, MFS, MATE, and SMR). Among RND and MFS systems, A. seifertii SAb133 presented the families AdeB/AdeJ and MdtB/MuxB, and Bcr/CflA and DHA2, respectively. Mutation in 23S rRNA (A2058G) that confers resistance to erythromycin, azithromycin and telithromycin were also detected. A great diversity of metal tolerance genes were detected, including for copper (copC, copD, corC, and nlpE), arsenic (arsB, arsC, and arsH), magnesium/cobalt (corA and mgtA), cadmium/zinc/cobalt (cusA and czcA), nickel/cobalt (nreB) and tellurite/selenite (ruvB), chromium (chrA), and tellurium (terD). The SAb133 isolate carried ABKVGs, including barA (acinetobactin), pmrB (sensor kinase), ompA (adherence), pbpG (serum resistance), pgaABCD and csu pili (biofilm formation), and galU (immune evasion) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Detection of ARGs, CPMs, multidrug efflux systems, MTGs, ABKVGs, ISs, and plasmids among A. seifertii strains.

| Strains | ARGsa | CPMsb | Multidrug | MTGsc | ABKVGsd | ISse | Plasmids |

| of 23S rRNA | efflux systems | ||||||

| SAb133 | blaADC–25, blaTEM | A2058G | RND, MFS, MATE, SMR | copC, copD, corC, nlpE, arsB, arsC, arsH, corA, mgtA, cusA, czcA, nreB, ruvB, chrA, terD | barA, ompA, pbpG, pgaABCD, csu pili, pmrB, galU | IS3, IS5, Tn3 | GR2, GR6 |

| KCJK7915 | blaADC–25 | A2058G | RND, MFS, MATE, SMR | copB, corC, nlpE, arsB, arsC, arsH, corA, mgtA, cusA, czcA, ruvB, terD | barA, pgaABCD, ompA, galU, csu pili, ptk | IS3 | GR2, GR6 |

| KCJK1723 | blaADC–25 | A2058G | RND, MFS, MATE, SMR | copB, nlpE, ruvB | barA, pgaABD, csu pili, ptk | IS3 | GR2, GR6 |

| 1334_ABAU | blaADC–25 | A2058G | RND, MFS, MATE, SMR | copB, copC, copD, corC, nlpE, arsC, corA, cusA, czcA, nreB, ruvB | pgaABD, ompA, galU | IS5 | GR2, GR6 |

| MI421-133 | blaADC–25 | A2058G | RND, MFS, MATE, SMR | copB, corC, nlpE, arsB, arsC, arsH, corA, mgtA, cusA, czcA, ruvB | barA, pgaABCD, ompA, galU, csu pili, ptk | ISA110 | GR2, GR6 |

| MI30-324 | blaADC–25 | A2058G | RND, MFS, MATE, SMR | copB, corC, nlpE, arsB, arsC, arsH, corA, mgtA, cusA, czcA, ruvB | barA, pgaABCD, ompA, galU, csu pili, ptk | ISA110 | GR2, GR6 |

| V1371 | blaADC–25 | A2058G | RND, MFS, MATE, SMR | copB, corC, nlpE, arsB, arsC, arsH, corA, mgtA, cusA, czcA, ruvB | barA, pgaABCD, ompA, galU, ptk | IS21 | GR2, GR6 |

| C917 | blaADC–25 | A2058G | RND, MFS | copC, corC, nlpE, arsH, corA, mgtA, czcA, ruvB, chrA | ompA, csu pili | IS3, IS5, IS6, IS66, IS256, ISNCY | GR2, GR6, GR7 |

| A354f | blaADC–25 | A2058G | RND, MFS | copB, nlpE, arsB, arsH, ruvB | pgaABCD, ompA, csu pili, lpsB, pmrB, pbpG, eps, ptk | IS3, IS5, IS66, Tn3 | GR2, GR6, GR7, ColRNAI |

| A360f | blaADC–25 | A2058G | RND, MFS | copB, copC, copD, nlpE, arsB, arsC, arsH, czcA, ruvB | pgaABCD, ompA, csu pili, lpsB, pmrB, pbpG, eps, ptk | IS3, IS5, IS66, IS256, ISNCY | GR2, GR6, GR7 |

| A362f | blaPER–1, aacA4, sul1, sul2, aph(3′)-VIa, aac(6′)Ib-cr, msr(E), mph(E), aac(3)-IId, floR, ARR-3 | A2058G | RND, MFS | copB, copC, copD, nlpE, arsB, arsH, ruvB | pgaABCD, ompA, csu pili, lpsB, pmrB, pbpG, eps, ptk | IS1, IS3, IS5, IS30, IS66, IS91, IS256, ISNCY | GR2, GR6, GR7, ColRNAI |

| NIPH973 | blaADC–25 | A2058G | RND, MFS | nlpE, arsH, corA, ruvB | pgaABD | IS1, IS3, IS4, IS5, IS6, IS30, IS66, IS256, IS630, ISNCY | GR2, GR6, GR7 |

aARGs, antimicrobial resistance genes. bCPM, chromosomal point mutations; A, adenine; G, guanine. cMTGs, metal tolerance genes. dABKVGs, A. baumannii known virulence genes. eISs, insertion elements. fData from Yang et al. (2016) expect for chromosomal point mutations, multidrug efflux pump systems, metal tolerance genes, insertion elements, and plasmids.

For comparing, ARGs, CPMs, MTGs, and ABKVGs detected in the A. seifertii SAb133 were analyzed in the 11 A. seifertii strains (i.e., KCJK7915, KCJK1723, 1334_ABAU, MI421-133, MI30-324, V1371, C917, A354, A360, A362, and NIPH973) using the genome annotation available in GenBank (Table 1). All A. seifertii strains presented blaADC–25, mutations in 23S rRNA (A2058G) and multidrug efflux systems (RND and MFS). Among RND efflux systems, the majority of A. seifertii strains (i.e., 1334_ABAU, KCJK7915, KCJK1723, MI421-133, MI30-324, and V1371) presented the AdeA/AdeI family and four A. seifertii strains (i.e., SAb133, 1334_ABAU, MI421-133, and MI30-324) presented the AdeB/AdeJ family. Several MTGs and ABKVGs have also detected in A. seifertii strains, principally in strains obtained from the environment and human (i.e., KCJK7915, MI421-133, MI30-324, V1371, A354, A360, A362, and C917). All A. seifertii strains presented at least ARG, CPM, MTG, and ABKVG (Table 3).

Acinetobacter seifertii SAb133 was the only one that presented blaTEM, RND efflux system (MdtB/MuxB family) and MFS efflux system (Bcr/CflA and DHA2 families) (Table 3). Two MTGs (nreB and terD) were detected only in three A. seifertii strains (i.e., SAb133, KCJK7915, and 1334_ABAU). The SAb133 genome presented three IS elements (i.e., IS3, IS5, and Tn3) and the all other A. seifertii strains had a least one IS element (Table 3). All A. seifertii strains presented GR2 and GR6 plasmids, and five A. seifertii strains (i.e., C917, A354, A360, A362, and NIPH973) presented the GR7. Curiously, the ColRNAI, a plasmid commonly detected in Enterobacteriaceae, was detected in A354 and A362 strains (Table 3). In addition, A. seifertii SAb133 also had the highest amount of genes related to antimicrobial resistance, tolerance to metals, and A. baumannii known virulence factors, except for Chinese clinical isolates (i.e., A354, A360, and A362).

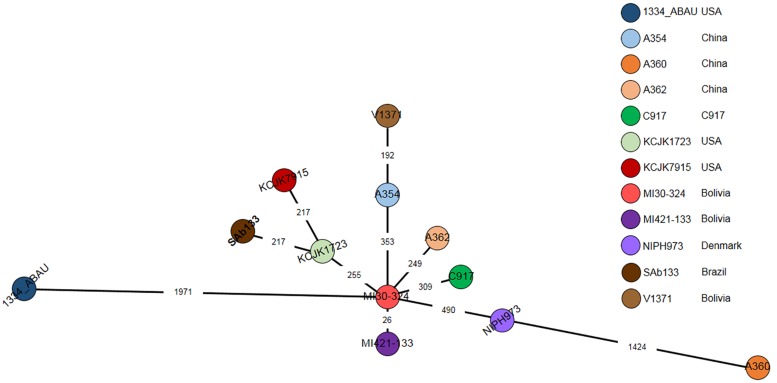

Epidemiological Analysis

A cgMLST based comparison identified from 23 to 1971-loci variant among A. seifertii strains. The smallest difference (26-loci variant) occurred between A. seifertii MI30-324 and A. seifertii MI421-133, both from Bolivia, while the largest difference (1971-loci variant) occurred between A. seifertii MI30-324 (Bolivia) and A. seifertii 1334_ABAU (United States). Five other A. seifertii strains (i.e., KCJK1723, A354, A362, C917, and NIPH973) belonging to China, United States and Dernmark also differed by A. seifertii MI30-324 from 255 to 490-loci variant. A. seifertii SAb133 (Brazil) and A. seifertii KCJK7915 (United States) differed by A. seifertii KCJK1723 (United States) by 213-loci variant and A. seifertii V1371 (Bolivia) differed by A. seifertii A354 (China) by 192-loci variant (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

cgMLST of 12 A. seifertii strains based on BacWGSTdb. Each circle represents an A. seifertii strain. The numbers on the connecting lines show the number of locus mismatches between A. seifertii strains. A. seifertii SAb133 was highlighted in bold.

Discussion

Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex has phenotypic and genotypic similar species and the WGS has proved to be an useful tool for identification of closely related species. To support species assignments, >95% threshold is commonly applied, which was detected in this study, supporting that SAb133 isolate belongs to A. seifertii (Richter and Rosselló-Móra, 2009; Varghese et al., 2015). Phylogenetic analysis showed that all A. seifertii strains were equally distributed when compared with non-A. seifertii strains. Thus, it is possible to suggest a phylogenetic history characterized by several independent evolutive processes (e.g., differential evolution rates among the strains and differential selection by several stress factors), due to the differences in the topologies of the phylogenetic Neighbor-Net tree and the ML tree, high lightening possible conflicts of phylogenetic signals which make harder the evolutive history elucidation of some A. seifertii strains.

The bacterial pangenome is defined as the sum of the core and accessory genomes (i.e., shell and cloud) and the core genome comprises the essential gene families sequenced in all bacterial species of a given clade. In addition, a fraction of the core genome may be split in soft-core, which refer to the set of genes present in at least 95% of all strains. The accessory genomes represent the set of non-essential genes present in a restrict number of strains. The shell genome represents a dispensable set of genes relatively ubiquitous in some taxa, while the cloud genome is related to a restrict set of genes present in very few strains (Contreras-Moreira and Vinuesa, 2013; McInerney et al., 2017). The pangenome results showed differential biological processes associated with survival and adaptation of A. seifertii strains, which can be related to their diverse physiological capabilities due to their ubiquitous distribution (i.e., human, animal, and environment) (Cordero and Polz, 2014).

Antimicrobial resistance is a worldwide public health threat and MDR bacteria have been reported in soil samples, despite the scarce number of papers addressing this topic in this environment. OXA-48-producing A. seifertii strains were recently reported in Brazil, with OXA-type β-lactamases being the most frequent ARG described in Acinetobacter sp., mainly in A. baumannii (Cayô et al., 2016; Narciso et al., 2017). Extended-spectrum AmpC cephalosporinase (ADC-25), and A. baumannii known virulence genes have been described in A. seifertii clinical strains (Yang et al., 2016), and TEM β-lactamase and intrinsic acquired efflux pumps (RND and non-RND) have also been reported in Acinetobacter spp. conferring resistance to different antimicrobials, antiseptics, biocides and detergents (Coyne et al., 2011; Montaña et al., 2016). A. seifertii SAb133 presented different antimicrobial resistance markers, which are closely related to the MDR phenotype found.

Metals are widely used as a growth promoter in animals and, consequently, may be biomagnified in the environment. The presence of metal compounds in the environment can select bacteria with reduced susceptibility to these compounds, leading to co-selection and reduced antimicrobial susceptibility (Wales and Davies, 2015). A. seifertii SAb133 showed several MTGs, which are associated with high MICs for metal compounds. The presence of antimicrobial resistance and metal tolerance genes in several bacterial genera including Acinetobacter sp., have been increasingly reported, which is of concern (Ji et al., 2012; Seiler and Berendonk, 2012).

The WGS has been used in different types of bacterial analysis, including evolution, epidemiology, pathogenicity and antimicrobial resistance (Almeida and De Martinis, 2019), and WGS-based typing of bacteria has been increasingly used for investigation of outbreaks and surveillance studies (Ruan and Feng, 2016). Different relatedness criteria for cgMLST were described for representative clinically relevant bacteria, including NFGNB, Enterococcus sp. and Mycobacterium sp. and enterobacteria. To date, among the species belonging to the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex, the A. baumannii is the only one to have an established relatedness criterion for cgMLST (≤3-loci) (Higgins et al., 2017; Schürch et al., 2018). Therefore, based on relatedness criteria for cgMLST of A. baumannii, the great majority of A. seifertii strains presented large amounts of locus differences, showing the divergence between these species.

Genomic islands are clusters of genes involved in the genome evolution and microbial adaptability, which can be classified into different subtypes, such as metabolic, fitness, symbiotic, antimicrobial resistance, and pathogenicity (Juhas et al., 2009). The mobile genetic elements (e.g., pathogenicity islands, plasmids, transposons, and insertion sequences) are closely related to the rapid development of MDR Acinetobacter sp., mainly A. baumannii. A great diversity of plasmids has been described in A. baumannii, which represent powerful routes for the evolution of antimicrobial resistance (Peleg et al., 2008; Lean and Yeo, 2017).

Conclusion

This study reports the first whole genome sequence of an A. seifertii isolated from a soil sample. To the best of our knowledge, this is the third report in Brazil and the fourth in the Latin America of an A. seifertii, being all the previous reports on isolates recovered from human and animal infections. The comparative genome sequence analysis done in this study showed that SAb133 presented the highest amount of determinants related to antimicrobial resistance and tolerance to metals, beyond the presence of A. baumannii known virulence genes, which demonstrates the great virulence potential derived from environmental A. seifertii strains. Moreover, this study contributes to a better understanding of the genetic relationship among the few known A. seifertii strains worldwide distributed.

Data Availability

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the GenBank accession no. SNSA00000000.

Author Contributions

JF isolated the bacterium and performed the phenotypic analyses. OA performed the phylogenetic analyses. JF and OA conceptualized the study, performed the comparative genomic analyses, and drafted the manuscript. ES and ED coordinated the project and revised the manuscript. All the authors approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Brazilian Bioethanol Science and Technology Laboratory (CTBE) NGS Sequencing Facility for the DNA sequencing and the Multiuser Facility from the Center for Medical Genomics at the Clinics Hospital of the Medical School of Ribeirão Preto, coordinated by Prof. Dr. Wilson Araújo da Silva Jr. who made available the server to perform the bioinformatics analyses. The authors also acknowledge the staff Marcelo Gomes for his valuable technical assistance with the server maintenance.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo – FAPESP (grant no. 2018/19539-0). The authors thank the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) (grant no. 88882.180855/2018-01 and code 001), and the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) (grant nos. 2017/13759-6 and 2018/01890-3) for fellowships.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019.02151/full#supplementary-material

References

- Alikhan N. F., Petty N. K., Ben Zakour N. L., Beatson S. A. (2011). BLAST ring image generator (BRIG): simple prokaryote genome comparisons. BMC Genomics 12:402. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida O. G. G., De Martinis E. C. P. (2019). Relating next-generation sequencing and bioinformatics concepts to routine microbiological testing. Electron. J. Gen. Med. 16:em136 10.29333/ejgm/108690 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo F. A., Barh D., Silva A., Guimarães L., Ramos R. T. J. (2018). GO FEAT: a rapid web-based functional annotation tool for genomic and transcriptomic data. Sci. Rep. 8:1794. 10.1038/s41598-018-20211-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt D., Grant J., Marcu A., Sajed T., Pon A., Liang Y., et al. (2016). PHASTER: a better, faster version of the PHAST phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 W16–W21. 10.1093/nar/gkw387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M., Ball C. A., Blake J. A., Botstein D., Butler H., Cherry J. M., et al. (2000). Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Gene ontology consortium. Nat. Genet. 25 25–29. 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A. A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A. S., et al. (2012). SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 19 455–477. 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendonk T. U., Manaia C. M., Merlin C., Fatta-Kassinos D., Cytryn E., Walsh F., et al. (2015). Tackling antibiotic resistance: the environmental framework. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13 310–317. 10.1038/nrmicro3439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertelli C., Laird M. R., Williams K. P., Simon Fraser University Research Computing Group, Lau B. Y., Hoad G., et al. (2017). IslandViewer 4: expanded prediction of genomic islands for larger-scale datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 W30–W35. 10.1093/nar/gkx343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertini A., Poirel L., Mugnier P. D., Villa L., Nordmann P., Carattoli A. (2010). Characterization and PCR-based replicon typing of resistance plasmids in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54 4168–4177. 10.1128/AAC.00542-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant D., Moulton V. (2004). Neighbor-net: an agglomerative method for the construction of phylogenetic networks. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21 255–265. 10.1093/molbev/msh018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capella-Gutiérrez S., Silla-Martínez J. M., Gabaldón T. (2009). trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25 1972–1973. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carattoli A., Zankari E., García-Fernández A., Voldby Larsen M., Lund O., Villa L., et al. (2014). In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58 3895–3903. 10.1128/AAC.02412-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cayô R., Rodrigues-Costa F., Matos A. P., Carvalhaes C. G., Dijkshoorn L., Gales A. C. (2016). Old clinical isolates of Acinetobacter seifertii in brazil producing OXA-58. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60 2589–2591. 10.1128/AAC.01957-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerezales M., Xanthopoulou K., Ertel J., Nemec A., Bustamante Z., Seifert H., et al. (2018). Identification of Acinetobacter seifertii isolated from Bolivian hospitals. J. Med. Microbiol. 67 834–837. 10.1099/jmm.0.000751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Yang J., Yu J., Yao Z., Sun L., Shen Y., et al. (2005). VFDB: a reference database for bacterial virulence factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 33 D325–D328. 10.1093/nar/gki008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras-Moreira B., Vinuesa P. (2013). GET_HOMOLOGUES, a versatile software package for scalable and robust microbial pangenome analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79 7696–7701. 10.1128/AEM.02411-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero O. X., Polz M. F. (2014). Explaining microbial genomic diversity in light of evolutionary ecology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12 263–273. 10.1038/nrmicro3218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne S., Courvalin P., Périchon B. (2011). Efflux-mediated antibiotic resistance in Acinetobacter spp. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55 947–953. 10.1128/AAC.01388-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deredjian A., Colinon C., Brothier E., Favre-Bonté S., Cournoyer B., Nazaret S. (2011). Antibiotic and metal resistance among hospital and outdoor strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Res. Microbiol. 162 689–700. 10.1016/j.resmic.2011.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32 1792–1797. 10.1093/nar/gkh340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlan J. P. R., Pitondo-Silva A., Stehling E. G. (2018). New STs in multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii harbouring β-lactamases encoding genes isolated from Brazilian soils. J. Appl. Microbiol. 125 506–512. 10.1111/jam.13885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlan J. P. R., Stehling E. G. (2019). Draft genome sequence of a multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli ST189 carrying several acquired antimicrobial resistance genes obtained from Brazilian soil. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 17 321–322. 10.1016/j.jgar.2019.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins P. G., Hrenovic J., Seifert H., Dekic S. (2018). Characterization of Acinetobacter baumannii from water and sludge line of secondary wastewater treatment plant. Water Res. 140 261–267. 10.1016/j.watres.2018.04.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins P. G., Prior K., Harmsen D., Seifert H. (2017). Development and evaluation of a core genome multilocus typing scheme for whole-genome sequence-based typing of Acinetobacter baumannii. PLoS One 12:e0179228. 10.1371/journal.pone.0179228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrenovic J., Durn D., Music M. S., Dekic S., Troskot-Corbic T., Skoric D. (2017). Extensively and multi drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii recovered from technosol at a dump site in Croatia. Sci. Total Environ. 607-608 1049–1055. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.07.108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson D. H., Bryant D. (2006). Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23 254–267. 10.1093/molbev/msj030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain C., Rodriguez-R L. M., Phillippy A. M., Konstantinidis K. T., Aluru S. (2018). High throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat. Commun. 9:5114. 10.1038/s41467-018-07641-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji X., Shen Q., Liu F., Ma J., Xu G., Wang Y., et al. (2012). Antibiotic resistance gene abundances associated with antibiotics and heavy metals in animal manures and agricultural soils adjacent to feedlots in Shanghai. China. J. Hazard. Mater. 235-236 178–185. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.07.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhas M., van der Meer J. R., Gaillard M., Harding R. M., Hood D. W., Crook D. W. (2009). Genomic islands: tools of bacterial horizontal gene transfer and evolution. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33 376–393. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00136.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalyaanamoorthy S., Minh B. Q., Wong T. K. F., von Haeseler A., Jermiin L. S. (2017). ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods. 14 587–589. 10.1038/nmeth.4285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishii K., Kikuchi K., Tomida J., Kawamura Y., Yoshida A., Okuzumi K., et al. (2016). The first cases of human bacteremia caused by Acinetobacter seifertii in Japan. J. Infect. Chemother. 22 342–345. 10.1016/j.jiac.2015.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laing C., Buchanan C., Taboada E. N., Zhang Y., Kropinski A., Villegas A., et al. (2010). Pan-genome sequence analysis using Panseq: an online tool for the rapid analysis of core and accessory genomic regions. BMC Bioinformatics 11:461. 10.1186/1471-2105-11-461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lean S. S., Yeo C. C. (2017). Small, enigmatic plasmids of the nosocomial pathogen, Acinetobacter baumannii: good, bad, who knows? Front. Microbiol. 15:1547. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Stoeckert C. J., Roos D. S. (2003). OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 13 2178–2189. 10.1101/gr.1224503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewen P. C., Alsaadi Y., Fernando D., Kumar A. (2014). Genome sequence of an extremely drug-resistant clinical isolate of Acinetobacter baumannii strain AB030. Genome Announc. 2:e01035-14. 10.1128/genomeA.01035-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magiorakos A. P., Srinivasan A., Carey R. B., Carmeli Y., Falagas M. E., Giske C. G., et al. (2012). Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18 268–281. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInerney J. O., McNally A., O’Connell M. J. (2017). Why prokaryotes have pangenomes. Nat. Microbiol. 2:17040. 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minh B. Q., Nguyen M. A., von Haeseler A. (2013). Ultrafast approximation for phylogenetic bootstrap. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30 1188–1195. 10.1093/molbev/mst024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaña S., Schramm S. T. J., Traglia G. M., Chiem K., Parmeciano Di Noto G., Almuzara M., et al. (2016). The genetic analysis of an acinetobacter johnsonii clinical strain evidenced the presence of horizontal genetic transfer. PLoS One 11:e0161528. 10.1371/journal.pone.0161528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narciso A. C., Martins W. M. B. S., Cayô R., De Matos A. P., Santos S. V., Ramos P. L., et al. (2017). Detection of OXA-58-producing Acinetobacter seifertii recovered from a black-necked swan at a Zoo Lake. Antimicrob. Agents Chemoter. 61:e01360-17. 10.1128/AAC.01360-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemec A., Krizova L., Maixnerova M., Sedo O., Brisse S., Higgins P. G. (2015). Acinetobacter seifertii sp. nov., a member of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex isolated from human clinical specimens. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 65 934–942. 10.1099/ijs.0.000043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemec A., Krizova L., Maixnerova M., van der Reijden T. J., Deschaght P., Passet V., et al. (2011). Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex with the proposal of Acinetobacter pittii sp. nov. (formerly Acinetobacter genomic species 3) and Acinetobacter nosocomialis sp. nov. (formerly Acinetobacter genomic species 13TU). Res. Microbiol. 162 393–404. 10.1016/j.resmic.2011.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L. T., Schmidt H. A., von Haeseler A., Minh B. Q. (2015). IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32 268–274. 10.1093/molbev/msu300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal C., Bengtsson-Palme J., Rensing C., Kristiansson E., Larsson D. G. (2014). BacMet: antibacterial biocide and metal resistance genes database. Nucleic Acids Res. 42 D737–D743. 10.1093/nar/gkt1252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peleg A. Y., Seifert H., Paterson D. L. (2008). Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21 538–582. 10.1128/CMR.00058-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter M., Rosselló-Móra R. (2009). Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 19126–19131. 10.1073/pnas.0906412106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach D. J., Burton J. N., Lee C., Stackhouse B., Butler-Wu S. M., Cookson B. T., et al. (2015). A year of infection in the intensive care unit: prospective whole genome sequencing of bacterial clinical isolates reveals cryptic transmissions and novel microbiota. PLoS Genet. 11:e1005413. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan Z., Feng Y. (2016). BacWGSTdb, a database for genotyping and source tracking bacterial pathogens. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 D682–D687. 10.1093/nar/gkv1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schürch A. C., Arredondo-Alonso S., Willems R. J. L., Goering R. V. (2018). Whole genome sequencing options for bacterial strain typing and epidemiologic analysis based on single nucleotide polymorphism versus gene-by-gene-based approaches. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 24 350–354. 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler C., Berendonk T. U. (2012). Heavy metal driven co-selection of antibiotic resistance in soil and water bodies impacted by agriculture and aquaculture. Front. Microbiol. 3:399. 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siguier P., Perochon J., Lestrade L., Mahillon J., Chandler M. (2006). ISfinder: the reference centre for bacterial insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 34 D32–D36. 10.1093/nar/gkj014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusova T., DiCuccio M., Badretdin A., Chetvernin V., Nawrocki E. P., Zaslavsky L., et al. (2016). NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 6614–6624. 10.1093/nar/gkw569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner J. W., Tallman J. J., Macias A., Pinnell L. J., Elledge N. C., Nasr Azadani D., et al. (2018). Comparative genomic analysis of Vibrio diabolicus and six taxonomic synonyms: a first look at the distribution and diversity of the expanded species. Front. Microbiol. 9:1893. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varghese N. J., Mukherjee S., Ivanova N., Konstantinidis K. T., Mavrommatis K., Kyrpides N. C., et al. (2015). Microbial species delineation using whole genome sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 6761–6771. 10.1093/nar/gkv657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waack S., Keller O., Asper R., Brodag T., Damm C., Fricke W. F., et al. (2006). Score-based prediction of genomic islands in prokaryotic genomes using hidden Markov models. BMC Bioinformatics 7:142. 10.1186/1471-2105-7-142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wales A. D., Davies R. H. (2015). Co-Selection of resistance to antibiotics, biocides and heavy metals, and its relevance to foodborne pathogens. Antibiotics. 4 567–604. 10.3390/antibiotics4040567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisburg W. G., Barns S. M., Pelletier B. A., Lane D. J. (1991). 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J. Bacteriol. 173 697–703. 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Wang J., Fu Y., Ruan Z., Yu Y. (2016). Acinetobacter seifertii isolated from china: genomic sequence and molecular epidemiology analyses. Medicine 95:e2937. 10.1097/MD.0000000000002937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zankari E., Hasman H., Cosentino S., Vestergaard M., Rasmussen S., Lund O., et al. (2012). Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67 2640–2644. 10.1093/jac/dks261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Liang Y., Lynch K. H., Dennis J. J., Wishart D. S. (2011). PHAST: a fast phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 39 W347–W352. 10.1093/nar/gkr485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the GenBank accession no. SNSA00000000.