Abstract

Objective

To compare the risk and severity of prostate cancer between men achieving fatherhood by assisted reproduction and men conceiving naturally.

Design

National register based cohort study.

Setting

Sweden from January 1994 to December 2014.

Participants

1 181 490 children born alive in Sweden during 1994-2014 to the same number of fathers. Fathers were grouped according to fertility status by mode of conception: 20 618 by in vitro fertilisation (IVF), 14 882 by intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), and 1 145 990 by natural conception.

Main outcome measures

Prostate cancer diagnosis, age of onset, and androgen deprivation therapy (serving as proxy for advanced or metastatic malignancy).

Results

Among men achieving fatherhood by IVF, by ICSI, and by non-assisted means, 77 (0.37%), 63 (0.42%), and 3244 (0.28%), respectively, were diagnosed as having prostate cancer. Mean age at onset was 55.9, 55.1, and 57.1 years, respectively. Men who became fathers through assisted reproduction had a statistically significantly increased risk of prostate cancer compared with men who conceived naturally (hazard ratio 1.64, 95% confidence interval 1.25 to 2.15, for ICSI; 1.33, 1.06 to 1.66, for IVF). They also had an increased risk of early onset disease (that is, diagnosis before age 55 years) (hazard ratio 1.86, 1.25 to 2.77, for ICSI; 1.51, 1.09 to 2.08, for IVF). Fathers who conceived through ICSI and developed prostate cancer received androgen deprivation therapy to at least the same extent as the reference group (odds ratio 1.91; P=0.07).

Conclusions

Men who achieved fatherhood through assisted reproduction techniques, particularly through ICSI, are at increased risk for early onset prostate cancer and thus constitute a risk group in which testing and careful long term follow-up for prostate cancer may be beneficial.

Introduction

Prostate cancer and male infertility are both very common disorders, affecting approximately 10% and 8%, respectively, of all men in Western societies.1 2 As prostate cancer and many forms of infertility are androgen related, the possible link between these disorders has been investigated previously. Three American studies have reported an increased risk of prostate cancer in men with impaired semen quality,3 4 5 whereas three Scandinavian studies and one American study indicated a lower risk of prostate cancer in childless men.6 7 8 9 This finding was recently confirmed in a meta-analysis summarising 10 individual studies.10 Others found no relation between fatherhood and the risk of prostate cancer.11 12 13 14

Neither fatherhood status nor sperm parameters represent ideal markers of male infertility. Whereas childlessness may be related to the female partner’s subfertility, the opportunity to start a family, or personal choice, and thus attributable to social rather than biological factors, semen parameters such as sperm concentration, morphology, and motility are subject to both laboratory and intra-individual variation. Nevertheless, for many infertile men, fatherhood is still possible through use of powerful assisted reproductive techniques. For men with very few sperm (oligozoospermia), or spermatozoa with poor progressive motility (asthenozoospermia), the only option for fatherhood is intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), in which a sperm is injected into an egg and the embryo put back into the uterus. This is also the only possibility for men with azoospermia, from whom gametes can be microsurgically gathered from the epididymis or testis. For men who do not have such severely deficient spermatogenesis, conventional in vitro fertilisation (IVF), in which sperm are allowed to fertilise retrieved oocytes in a laboratory dish, is the standard procedure. In Sweden, ICSI treatment is mainly used in cases with significantly impaired semen quality, with male factor infertility being the major indication for ICSI.15 16

The objective of this study was to use compulsory national registries containing information on prostate cancer diagnoses and infertility treatments to investigate whether the risk of prostate cancer in men who became fathers through IVF or ICSI, reflecting the grade of hampered spermatogenesis, differed in terms of incidence, age at onset, and, where applicable, severity from men who achieved fatherhood naturally. Such information could be important for defining clinical routines for follow-up of men undergoing fertility treatment.

Methods

Registers and study populations

We retrieved data on all children born alive in Sweden during the period 1994-2014 (n=2 108 569), as well as their fathers, from the Swedish Medical Birth Register and the Swedish Multi-generation Register. We excluded children with missing paternal identification numbers. We matched the remaining records with the Swedish National Quality Register for Assisted Reproduction. The Swedish Cancer Registry, the Swedish Register of Education, and the Swedish Cause of Death Register supplied the paternal prostate cancer diagnoses, paternal education data, and date of death, respectively. Reporting of cancer diagnoses to the national Swedish Cancer Registry is mandated by law for all newly diagnosed cancers, with an approximated completeness of 96%,17 ensuring a complete assessment of prostate cancer diagnoses. Similarly, reporting of fertility treatments is mandatory, in both private and public clinics, with coverage close to 100%. Data on patients undergoing intrauterine insemination, which is an uncommon procedure in Sweden, was not collected. Thus, in this paper, assisted reproductive techniques refers to ICSI and IVF. As ICSI was first used in 1992, virtually all fathers who conceived through ICSI in Sweden are likely to be included in our cohort.

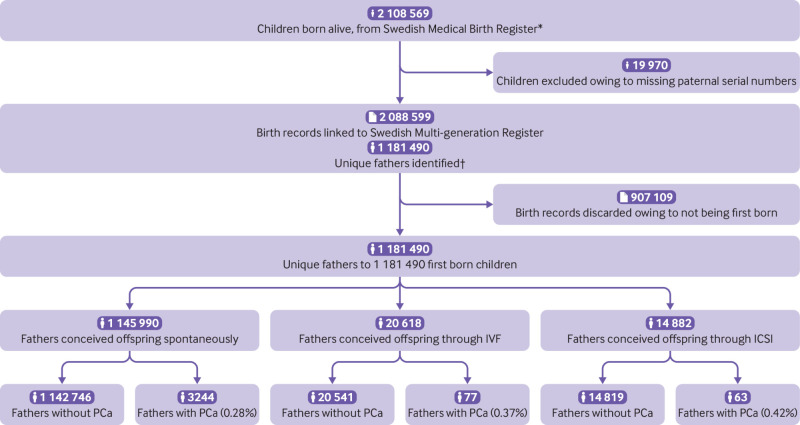

To avoid bias introduced by fathers being counted multiple times, we paired the birth record of the first child born within the cohort interval with the father. This resulted in 1 181 490 children born to the same number of fathers (fig 1). Prostate cancer was defined according to ICD-7 (international classification of diseases, 7th revision) diagnosis code (177) and early onset prostate cancer according to European Association of Urology guidelines18 (that is, diagnosed before the age of 55).

Fig 1.

Flowchart of inclusion process and register linkage. *1 January 1994 to 31 December 31. †Registers linked to Swedish Education Register, Swedish National Quality Register for Assisted Reproduction, and Swedish Cancer Registry. PCa=prostate cancer; ICSI=intracytoplasmic sperm injection; IVF=in vitro fertilisation

Using data from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register, available from July 2005 to November 2016, we identified men who had received androgen deprivation therapy. This is indicated only in cases of locally advanced or metastatic prostate cancer and not in low risk malignancies.19 Thus, androgen deprivation therapy can act as a proxy for the severity and clinical significance of malignancy. We identified men receiving androgen deprivation therapy, with the date of their first prescription, by parsing for the following drugs: abiraterone acetate, buserelin, cyproterone acetate, degarelix, enzalutamide, flutamide, goserelin, histrelin acetate, leuprorelin, megestrol acetate, nilutamide, and triptorelin.

As receiving testosterone replacement therapy has an unknown effect on risk of prostate cancer, we excluded these men identified by data from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register in a sensitivity analysis. Prescription of testosterone at any time led to exclusion (336 ICSI treated fathers, 212 IVF treated fathers, and 7495 reference fathers).

Statistical analysis

We grouped the fathers according to mode of conception of their child; ICSI, IVF, or natural conception (reference group). We constructed Kaplan-Meier survival curves stratified on the aforementioned groups, with accompanying log rank tests. We used Cox regression to estimate hazard ratios. In the Cox regressions analyses, we corrected for paternal age by adjusting for fathers’ age at childbirth (continuous). We followed the fathers from conception of the child until diagnosis of prostate cancer, death, or end of follow-up (31 December 2014). We estimated the date of conception by using gestational length data from the Medical Birth Register. To adjust for socioeconomic status, the Cox model was adjusted for the father’s education level (years of formal education, categorical: ≤10, 11-14, ≥15, or missing data).

We tested the assumption of proportionality of hazards by the significance level of the interaction between prostate cancer and the natural logarithm of time within the full Cox regression model with all covariates. We further investigated any evidence of non-proportionality (P<0.05) by estimating hazard ratios for restricted time intervals.

To investigate whether men achieving fatherhood by assisted means had an altered risk of early onset prostate cancer, we did an analysis in which we defined an event as prostate cancer diagnosed before age 55. Follow-up was as above, with the fathers being right censored when they reached age 55. This analysis was adjusted for the same covariates as before (paternal age and paternal education level). We also combined the fathers treated with ICSI and those treated with IVF into one group so that a combined risk estimate could be obtained for men becoming fathers through assisted reproduction techniques.

As the follow-up for each father started from conception of the child, men with a prostate cancer diagnosis before that point were excluded, leading to nine ICSI treated fathers, one IVF treated father, and 28 naturally conceiving fathers being excluded from the analyses. However, as cancer treatment may cause subsequent fertility problems, we did a separate sensitivity analysis in which fathers who had been diagnosed as having any cancer (ICD-7: 140-207.9) before child conception, not only prostate cancer, were also excluded (ICSI, n=451; IVF, n=171; natural conception, n=5179).

As ICSI is indicated in more severe forms of male infertility (azoospermia, severe oligozoospermia) and IVF is used in female infertility, combined with mild or no male infertility,15 16 we tested for a trend between level of infertility and prostate cancer. This assumed an equidistant stepwise function for the level of infertility among fathers conceiving naturally, via IVF, or via ICSI (continuous variable coded: natural conception=0, IVF=1, ICSI=2).

Among all fathers with prostate cancer, we compared the fathers who conceived through ICSI and IVF with those who conceived naturally, to estimate the risk for receiving androgen deprivation therapy after diagnosis of prostate cancer. As prescriptions for androgen deprivation therapy could not be ascertained before July 2005, only prostate cancer diagnoses after this date were included in this analysis. After these exclusions 52 ICSI treated, 68 IVF treated, and 2967 reference fathers remained. This analysis also serves to detect overdiagnosis of clinically insignificant cases of prostate cancer among men undergoing assisted reproduction, owing to their contacts with the healthcare system. This potential bias would likely lead to these men being diagnosed as having prostate cancer at an earlier age, with lower grade, and therefore generally not being treated with androgen deprivation therapy. Conversely, observing an equal or higher risk of androgen deprivation therapy for men undergoing assisted reproduction would indicate no such bias. For this analysis, we constructed a binary logistic regression model, adjusted for the father’s age at prostate cancer diagnosis (continuous) and paternal educational level, yielding odds ratios, with an odds ratio below 1 indicating possible bias resulting in more diagnoses of low grade prostate cancer among the assisted reproduction groups—for example, due to better access to prostate specific antigen screening. Conversely, an odds ratio of 1 or above points to an increase in prevalence of clinically relevant prostate cancer, which would likely be diagnosed regardless of whether those men were in contact with the healthcare system.

We also did sensitivity analyses in which men receiving testosterone were excluded. We calculated risk estimates for prostate cancer and for early onset prostate cancer by using the same Cox regression method as above.

We used SPSS version 25 and R version 3.5.0 with the ggplot2 package for statistical analyses. All analyses were two sided, and we defined P<0.05 as statistically significant.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in the design of this study, nor were any patients involved in the implementation of it or consulted on the reporting of the results. There are no plans to disseminate the results to the research cohort or to relevant patient communities.

Results

Of 1 181 490 fathers, 20 618 (1.7%) had undergone IVF during the study period, 14 882 (1.3%) had undergone ICSI, and 1 145 990 (97.0%) had conceived children by natural conception. Table 1 shows characteristics of the fathers. The total follow-up time was 14 389 198 person years. The mean age at childbirth of both IVF and ICSI treated fathers was 37 years, whereas the fathers who conceived naturally were 4 years younger on average. Of the men who sired pregnancies naturally, 3244 (0.28%) were diagnosed as having prostate cancer, compared with 77 (0.37%) in the IVF group and 63 (0.42%) in the ICSI group. After exclusion of cases of prostate cancer before conception, 3216 (0.28%), 76 (0.37%), and 54 (0.36%) had been diagnosed as having prostate cancer in the reference, IVF, and ICSI groups. The ICSI treated fathers had the youngest mean age of onset (55.4 years), on average almost 2 years younger than the reference group.

Table 1.

Characteristics of fathers who conceived offspring naturally, through intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), and through in vitro fertilisation (IVF). Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Fathers conceiving naturally (n=1 145 990; 97.0%) | Fathers conceiving by IVF (n=20 618; 1.7%) | Fathers conceiving by ICSI (n=14 882; 1.3%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age at birth of child, years | 32.5 (6.2) | 36.6 (5.3) | 36.9 (6.0) |

| Mean (SD) age at end of follow-up*, years | 44.0 (9.0) | 45.9 (8.1) | 45.2 (7.9) |

| Years of formal education: | |||

| <10 | 139 012 (12.1) | 1549 (7.5) | 1205 (8.1) |

| 10-14 | 648 789 (56.6) | 10 631 (51.6) | 7862 (52.8) |

| ≥15 | 348 081 (30.4) | 8375 (40.6) | 5754 (38.7) |

| Missing | 10 108 (0.9) | 63 (0.3) | 61 (0.4) |

| All prostate cancer: | |||

| Fathers with prostate cancer | 3244 (0.3) | 77 (0.4) | 63 (0.4) |

| Mean (SD) age at diagnosis, years | 57.1 (6.9) | 55.9 (5.9) | 55.1 (7.0) |

| Early onset prostate cancer (diagnosis age <55) | 1274 (39.3) | 39 (51) | 29 (46) |

| Prostate cancer, excluding cases occurring before child conception: | |||

| Fathers with prostate cancer | 3216 (0.3) | 76 (0.4) | 54 (0.4) |

| Mean (SD) age at diagnosis, years | 57.2 (6.9) | 56.1 (5.8) | 55.4 (6.7) |

| Mean (SD) time between child conception and diagnosis, years | 14.5 (4.7) | 13.3 (5.2) | 9.5 (4.6) |

| Early onset prostate cancer (diagnosis age <55) | 1257 (39.1) | 38 (50) | 25 (46) |

| Androgen deprivation therapy†: | |||

| Fathers treated with androgen deprivation therapy | 387§/2967 (13.0) | 8/68 (12) | 10/52 (19) |

| Mean (SD) age at start of therapy, years | 60.2 (7.6) | 57.0 (4.6) | 56.4 (8.8) |

| Early onset prostate cancer (diagnosis age <55 years) | 105 (8.4) | 3 (8) | 5 (20) |

End of follow-up in Cancer Registry (31 December 2014). Deaths not accounted for.

Patients receiving androgen deprivation therapy within 1 year of prostate cancer diagnosis. Excluding cases occurring before child conception or diagnosed before 1 July 2005.

Including 12 cases in which androgen deprivation therapy was prescribed in the week preceding prostate cancer diagnosis date.

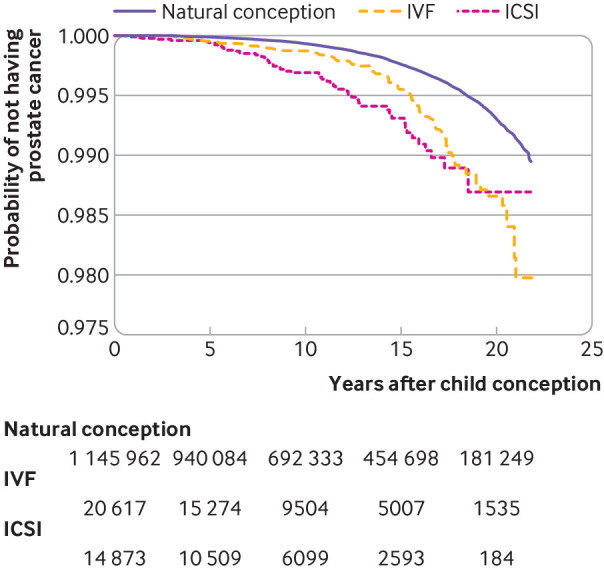

In the entire cohort, men who had undergone ICSI treatment had a statistically significantly increased risk of prostate cancer (hazard ratio 1.64, 95% confidence interval 1.25 to 2.15; P<0.001) compared with natural conception (table 2; fig 2). IVF fathers also had a statistically significantly increased risk, but of a lesser magnitude (hazard ratio 1.33, 1.06 to 1.66; P=0.02) compared with natural conception. We detected evidence of non-proportionality for ICSI, but not IVF, compared with natural conception (interaction with log (time), P=0.01). The adjusted hazard ratios for the first and second halves of follow-up were 2.22 (1.56 to 3.16; P<0.001) and 1.18 (0.78 to 1.80; P=0.44), respectively. In all other Cox models, the P value for the interaction was greater than or equal to 0.05.

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted risk estimates for prostate cancer.

| Outcome | Fathers conceiving by IVF compared with natural conception | Fathers conceiving by ICSI compared with natural conception | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk estimate (95% CI) | P value | Risk estimate (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Prostate cancer: | |||||

| Unadjusted hazard ratio | 2.09 (1.66 to 2.62) | <0.001 | 3.12 (2.38 to 4.08) | <0.001 | |

| Adjusted hazard ratio | 1.33 (1.06 to 1.66) | 0.02 | 1.64 (1.25 to 2.15) | <0.001 | |

| Early onset prostate cancer: | |||||

| Unadjusted hazard ratio | 2.93 (2.12 to 4.05) | <0.001 | 3.66 (2.46 to 5.44) | <0.001 | |

| Adjusted hazard ratio | 1.51 (1.09 to 2.08) | 0.01 | 1.86 (1.25 to 2.77) | 0.002 | |

| Androgen deprivation therapy: | |||||

| Unadjusted odds ratio | 0.89 (0.42 to 1.87) | 0.76 | 1.59 (0.79 to 3.19) | 0.19 | |

| Adjusted odds ratio | 0.99 (0.47 to 2.10) | 0.98 | 1.91 (0.94 to 3.88) | 0.07 | |

ICSI=intracytoplasmic sperm injection; IVF=in vitro fertilisation.

Fig 2.

Kaplan-Meier function for prostate cancer in fathers who conceived through intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) and in vitro fertilisation (IVF), compared with natural conception. Numbers are fathers remaining at risk at 5 year intervals after child conception. Log rank P<0.001

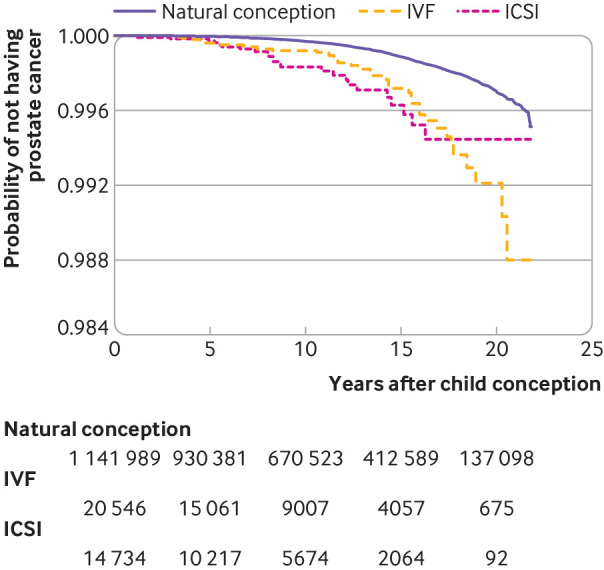

Moreover, both ICSI treated fathers and IVF treated fathers had a statistically significantly increased risk of early onset prostate cancer (hazard ratio 1.86, 1.25 to 2.77 (P=0.002) for ICSI; 1.51, 1.09 to 2.08 (P=0.01) for IVF) (fig 3). Table 2 shows unadjusted risk estimates.

Fig 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival function for early onset prostate cancer in fathers who conceived through intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) and in vitro fertilisation (IVF), compared with natural conception. Numbers are fathers remaining at risk at 5 year intervals after child conception. Log rank P<0.001

Men who became fathers through assisted reproduction techniques (combined ICSI and IVF) had a statistically significantly increased risk of prostate cancer (odds ratio 1.44, 1.21 to 1.71; P<0.001) and early onset prostate cancer (1.63, 1.26 to 1.63, P<0.001) compared with men achieving fatherhood naturally. When we excluded fathers who were diagnosed as having any cancer before their offspring’s conception date, ICSI treated fathers still had a statistically significant increased risk of prostate cancer (hazard ratio 1.70, 1.29 to 2.22; P<0.001) and of early onset prostate cancer (1.92, 1.29 to 2.86; P=0.001). Similarly, IVF treated fathers retained their increased risk for prostate cancer (hazard ratio 1.30, 1.03 to 1.64; P=0.02) and early onset prostate cancer (1.45, 1.04 to 2.02; P=0.03). We detected a statistically significant trend for the association of level of infertility and prostate cancer (odds rationatural, IVF, ICSI 1.29, 1.15 to 1.45; P<0.001). Similarly, we detected a trend for the association between level of infertility and the risk of early onset prostate cancer (odds rationatural, IVF, ICSI 1.40, 1.18 to 1.66; P<0.001).

The ICSI treated fathers with prostate cancer also had the highest rate of receipt of androgen deprivation therapy (19.2%) compared with the reference group (13.0%) and IVF group (11.8%). We saw no indication that men who underwent assisted reproduction were more often diagnosed as having low grade prostate cancer than men who conceived naturally (odds ratio 1.91, 0.94 to 3.88 (P=0.07) for ICSI; 0.99, 0.47 to 2.10 (P=0.98) for IVF). Exclusion of men who received testosterone replacement therapy had a negligible effect on hazard ratios for prostate cancer and for early onset prostate cancer for both the ICSI and IVF groups.

Discussion

The main conclusion of this study, comprising virtually all men fathering a child in Sweden during two decades, is that men who achieved fatherhood through assisted reproduction had a remarkably high risk of prostate cancer. Fathers who used ICSI had a 60% higher risk and those who used IVF had a 30% higher risk, compared with men who conceived naturally. The increase in risk was most pronounced before the age of 55 years and was still present after exclusion of men who had been treated for any cancer and therefore with potentially gonadotoxic treatments before the child’s conception.

Strengths and weaknesses of study

The strengths of this study are access to population based datasets and the completeness of the registries. A drawback is the lack of data in the registries on fertility treatment in men who did not succeed in becoming fathers. Hence, the most severe cases may not have been included. However, our results, specifically the trend showing an increasing risk of prostate cancer and of early onset prostate cancer, may indicate that it is the underlying level of infertility that is associated with the man’s risk of this malignancy. This might indicate that our results could be generalised to men undergoing assisted reproduction techniques without achieving fatherhood or possibly even to infertile men in general. This would align well with previous studies showing increased risk of prostate cancer for men with poor semen parameters.3 4 5

Furthermore, data on prostate specific antigen were not available. Such data could have provided direct evidence as to whether men undergoing ICSI receive closer follow-up than their counterparts, but the registries do not include this information. Finally, data on men who died from prostate cancer before they had a chance to become fathers are lacking. However, with a mean age of only 37 years for the ICSI/IVF treated fathers and 32 years for those who conceived naturally, the effect of such selection bias can be considered small. Men attaining fatherhood through IVF and ICSI were on average older and also more well educated at the birth of their offspring. However, the presented risk estimates were adjusted for these factors.

The evidence of non-proportionality for ICSI treated men indicates a higher risk in the first decade after conception but no elevated risk thereafter. This might be due to an insufficient number of ICSI treated men with long follow-up, because few men were treated with ICSI in the 1990s, yielding uncertain risk estimates. However, as ICSI treated men have an increased risk of early onset prostate cancer, but not of the late onset variety, this is could be reflecting aetiological differences between early and late onset of prostate malignancy.20

Strengths and weaknesses in relation to other studies

The reports indicating a lower risk of prostate cancer in childless or infertile men generally included men with a mean age of 60 years or above,6 7 8 9 10 21 meaning that those with early onset and more aggressive prostate cancer may already have died from their disease. Consequently, studies based on follow-up of younger men with fertility problems,3 4 5 including this report, will tend to include cases of early onset prostate cancer. Studies on older men and their risk of prostate cancer may fail to find this risk increase or even come to the opposite conclusion. However, whereas previous studies relied on smaller datasets, sometimes with self reported childlessness and short follow-up, our study is based on more than one million men and up to 20 years of follow-up.

Men undergoing assisted reproduction owing to an increased risk of hypogonadism may have been candidates for testosterone replacement therapy and may therefore have been tested for prostate specific antigen more frequently to exclude ongoing prostate cancer.22 This bias could lead to a detectable increased risk among IVF and ICSI treated fathers. However, excluding men receiving testosterone had a negligible effect on the risk of prostate cancer, indicating no such bias. Furthermore, few men undergoing assisted reproduction are likely to have prostate specific antigen tests, as these are usually administered only to older men. That said, if such testing, being a consequence of these men being in contact with the health service, is the reason why ICSI treated men are diagnosed as having prostate cancer at younger ages, one would expect a decreased administration of androgen deprivation therapy among ICSI treated men, which is the opposite of what is observed. The same would apply to ascertainment bias, to which the outcome of prostate cancer is particularly prone to. However, increased medical attention for men seeking treatment for infertility can explain neither the almost doubled rate of androgen deprivation therapy among ICSI treated fathers nor the trend seen with the level of infertility.

Meaning of study: possible explanations and implications for clinicians and policy makers

This work shows that men fathering children by assisted reproduction are a high risk group for prostate cancer at early ages. As clinicians have for many years noted that early onset prostate cancer is associated with poor prognosis, even before the era of prostate specific antigen screening, men undergoing assisted reproduction may merit further attention and comprise an easily accessible category of patients who may benefit from early screening. Screening by prostate specific antigen testing seems to be the most appropriate, most cost effective, and least invasive first line method for early detection of prostate cancer, and applying it for men treated with assisted reproduction could be beneficial. We would, therefore, welcome studies in other cohorts investigating the risk of prostate cancer in men being treated for infertility and studies on the efficacy and benefits of screening for this risk group, similarly to what is currently offered for other high risk groups.

Unanswered questions and future research

This study was limited mainly to men with prostate cancer diagnoses early in life. As ICSI has been used only since the 1990s, detecting late onset prostate cancer in these men requires longer follow-up and is a matter for future research.

What is already known on this topic

As prostate cancer and many forms of infertility are androgen related, a possible link between them has been studied, yielding contradictory results

Studies in older men using childlessness as a proxy for infertility show that childless men have a lower risk of prostate cancer

Studies in younger men, assessing fertility by means of semen parameters, indicate a higher risk of prostate cancer

Previous studies have been limited by small numbers of study participants, self reported diagnoses, or short follow-up time

What this study adds

This large register based study show that men fathering children through assisted reproduction have a 30-60% increased risk of prostate cancer compared with men conceiving naturally

They have almost twice the risk of developing early onset prostate cancer, before 55 years of age

Men fathering children through assisted reproduction seem to be at higher risk for prostate cancer, so the benefits of prostate cancer screening should be considered for this group

Contributors: YLG and AG designed and supervised the study. YA, AE, EW, and IS analysed the data. All authors had access to the raw data, interpreted the analysed data, discussed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. YLG is the guarantor.

Funding: The study was funded by the Swedish Cancer Foundation (CAN 2014/360 and 2017/392), an ALF government grant (F2014/354), the Malmö University Hospital Cancer Research Fund, the Swedish Prostate Cancer Federation, and the European Association of Urology (scholarship EUSP/REPRO-02-2017). Funders had no role in study design, results, or write-up or manuscript submission decisions other than to provide funding. The researchers were independent of the funders.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: support for the submitted work as detailed above; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: The Regional Ethical Board in Lund, Sweden, approved the study (No 2015/670).

Transparency: The lead author (the manuscript’s guarantor) affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Data sharing: Medical researchers can, if conditions are met under Swedish law, obtain de-identified data by contacting the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Hill M. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents, Volume VI. Eur J Cancer Prev 1993;2:419 10.1097/00008469-199309000-00010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gannon JR, Walsh TJ. The epidemiology of male infertility In: Carrell DT, Schlegel PN, Racowsky C, Gianaroli L, eds. Biennial Review of Infertility. Springer International Publishing, 2015:1-5. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Walsh TJ, Schembri M, Turek PJ, et al. Increased risk of high-grade prostate cancer among infertile men. Cancer 2010;116:2140-7. 10.1002/cncr.25075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eisenberg ML, Li S, Brooks JD, Cullen MR, Baker LC. Increased risk of cancer in infertile men: analysis of U.S. claims data. J Urol 2015;193:1596-601. 10.1016/j.juro.2014.11.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rosenblatt KA, Wicklund KG, Stanford JL. Sexual factors and the risk of prostate cancer. Am J Epidemiol 2001;153:1152-8. 10.1093/aje/153.12.1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Giwercman A, Richiardi L, Kaijser M, Ekbom A, Akre O. Reduced risk of prostate cancer in men who are childless as compared to those who have fathered a child: a population based case-control study. Int J Cancer 2005;115:994-7. 10.1002/ijc.20963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jørgensen KT, Pedersen BV, Johansen C, Frisch M. Fatherhood status and prostate cancer risk. Cancer 2008;112:919-23. 10.1002/cncr.23230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ruhayel Y, Giwercman A, Ulmert D, et al. Male infertility and prostate cancer risk: a nested case-control study. Cancer Causes Control 2010;21:1635-43. 10.1007/s10552-010-9592-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Eisenberg ML, Park Y, Brinton LA, Hollenbeck AR, Schatzkin A. Fatherhood and incident prostate cancer in a prospective US cohort. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:480-7. 10.1093/ije/dyq163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mao Y, Xu X, Zheng X, Xie L. Reduced risk of prostate cancer in childless men as compared to fathers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2016;6:19210. 10.1038/srep19210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hanson HA, Anderson RE, Aston KI, Carrell DT, Smith KR, Hotaling JM. Subfertility increases risk of testicular cancer: evidence from population-based semen samples. Fertil Steril 2016;105:322-8.e1. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.10.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cox B, Sneyd MJ, Paul C, Skegg DC. Risk factors for prostate cancer: A national case-control study. Int J Cancer 2006;119:1690-4. 10.1002/ijc.22022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Negri E, Talamini R, Bosetti C, Montella M, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C. Risk of prostate cancer in men who are childless. Int J Cancer 2006;118:786-7, author reply 788. 10.1002/ijc.21369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lightfoot N, Conlon M, Kreiger N, Sass-Kortsak A, Purdham J, Darlington G. Medical history, sexual, and maturational factors and prostate cancer risk. Ann Epidemiol 2004;14:655-62. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2003.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hamberger L, Lundin K, Sjögren A, Söderlund B. Indications for intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Hum Reprod 1998;13(Suppl 1):128-33. 10.1093/humrep/13.suppl_1.128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Palermo GD, Neri QV, Rosenwaks Z. To ICSI or Not to ICSI. Semin Reprod Med 2015;33:92-102. 10.1055/s-0035-1546825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barlow L, Westergren K, Holmberg L, Talbäck M. The completeness of the Swedish Cancer Register: a sample survey for year 1998. Acta Oncol 2009;48:27-33. 10.1080/02841860802247664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aus G, Abbou CC, Bolla M, et al. European Association of Urology EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2005;48:546-51. 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sharifi N, Gulley JL, Dahut WL. Androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. JAMA 2005;294:238-44. 10.1001/jama.294.2.238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Salinas CA, Tsodikov A, Ishak-Howard M, Cooney KA. Prostate cancer in young men: an important clinical entity. Nat Rev Urol 2014;11:317-23. 10.1038/nrurol.2014.91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wirén SM, Drevin LI, Carlsson SV, et al. Fatherhood status and risk of prostate cancer: nationwide, population-based case-control study. Int J Cancer 2013;133:937-43. 10.1002/ijc.28057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bobjer J, Bogefors K, Isaksson S, et al. High prevalence of hypogonadism and associated impaired metabolic and bone mineral status in subfertile men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2016;85:189-95. 10.1111/cen.13038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]