Abstract

Background: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is the most reported pathogen in hand infections at urban medical centers throughout the country. Antibiotic sensitivity trends are not well known. The purposes of this study were to examine and determine the drug resistance trends for MRSA infections of the hand and to provide recommendations for empiric antibiotic treatment based on sensitivity profiles. Methods: A 10-year longitudinal, retrospective chart review was performed on all culture-positive hand infections encountered at a single urban medical center from 2005 to 2014. The proportions of all organisms were calculated for each year and collectively. MRSA infections were additionally subanalyzed for antibiotic sensitivity. Results: A total of 815 culture-positive hand infections were identified. Overall, MRSA grew on culture in 46% of cases. A trend toward decreasing annual MRSA incidence was noted over the 10-year study period. There was a steady increase in polymicrobial infections during the same time. Resistance to clindamycin increased steadily during the 10-year study, starting at 4% in 2008 but growing to 31% by 2014. Similarly, levofloxacin resistance consistently increased throughout the study, reaching its peak at 56% in 2014. Conclusions: The annual incidence of MRSA in hand infections has declined overall but remains the most common pathogen. There has been an alternative increase in the number of polymicrobial infections. MRSA resistance to clindamycin and levofloxacin consistently increased during the study period. Empiric antibiotic therapy for hand infections should not only avoid penicillin and other beta-lactams but should also consider avoiding clindamycin and levofloxacin for empiric treatment.

Keywords: hand infection, MRSA, antibiotic resistance, polymicrobial, hand abscess

Introduction

Acute infections of the hand are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality.12 The timeliness of surgical treatment and antibiotic therapy are critical to avoid devastating outcomes. It has been widely reported that Staphylococcus aureus is the most common causative pathogen in hand infections.1-3,6,8,11,13,17,18 Particularly, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is the most commonly cultured organism at urban medical centers.1,2,17 Complications and sequelae of hand infections including stiffness, fibrosis, sepsis, and amputation have been most commonly associated with MRSA infection.6 In addition, MRSA is well known to be associated with increasing health care costs, treatment failure rates, and increased hospital lengths of stay.9,15-17 The correct choice of antibiotic treatment in combination with surgical intervention is critical for the avoidance of such complications.

Traditionally, the treatment for hand infections has included incision and drainage along with empiric antibiotic therapy. Currently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends empiric antibiotics for MRSA if the local resistance is known to be greater than 10% to 15%.5 Common empiric choices for possible MRSA infections include clindamycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, daptomycin, and vancomycin. Antibiotic resistance and sensitivity profiles to MRSA are well documented in the literature, but resistance and antibiotic sensitivity trends over time are not well known. A recent study showed that MRSA is becoming increasingly resistant to clindamycin, which has traditionally been offered to empirically treat hand infections.18 Therefore, the purposes of this study were to examine the epidemiology and determine the drug resistance trends for MRSA infections of the hand to provide recommendations for empiric antibiotic treatment based on current sensitivity profiles.

Material and Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed on all culture-positive hand infections encountered at an urban academic medical center between January 1, 2005, and December 31, 2014. Approval for the study was obtained through the institutional review board. All cases of documented hand infections encountered in the emergency department, outpatient office, and inpatient setting were reviewed. Subjects were obtained using both International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes corresponding to cellulitis, abscess, tenosynovitis, and open wounds of the hands and fingers (Table 1). All demographic and laboratory data were obtained via medical record review.

Table 1.

List of ICD Codes Used for Subject Identification.

| ICD-9 codes | ICD-10 codes |

|---|---|

| 681.00 681.01 681.02 682.4 727.05 727.9 883.00 883.1 882.01 882.00 |

L03.01 M71.04 L02.511 L02.512 L02.519 M65.041 M65.042 M65.049 L02.51 M65.04 L02.5 M65.14 M65.841 M65.842 M65.849 M65.84 S61.4 S61.40 S61.401 S61.402 S61.409 S61.009 S61.209 S61.0 S61.1 S61.2 S61.3 |

All patients between the ages of 18 and 89 years were included in the review, but only those with culture-positive hand infections were included in the final analysis. Any patient with multiple positive culture results during the same hospital stay was identified so that the same organism was not counted twice. Infections were considered nosocomial if the medical record review revealed a history of a surgical procedure, dialysis treatments, catheterizations, hospital admission, or nursing home stay within 1 year prior to positive culture.

We calculated the annual frequencies of the 2 most common organisms (MRSA and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus [MSSA]) and polymicrobial infections. A polymicrobial infection was considered any infection with more than 1 isolate identified on culture. Polymicrobial infections were not considered mutually exclusive of MRSA and MSSA infection, with the frequencies of other organisms (eg, a polymicrobial infection with MRSA was included in both the “MRSA” and “polymicrobial” categories). MRSA infections were then further subanalyzed for their antibiotic sensitivity profiles.

Results

A total of 815 culture-positive hand infections were identified over the 10-year study period. Males accounted for 55% of patients. The most common etiologies for hand infections were trauma (72%) and intravenous drug use (22%). Bite injuries accounted for 5% of cases. The average annual frequency of comorbidities was fairly consistent for patients with diabetes being on average 16.6% (range, 12.6%-30.5%) of the population, and those who were positive for human immunodeficiency virus representing on average 3.7% (range, 0%-6.8%) of the population. Intravenous drug users represented a larger population of patients over the course of the study: starting at 13.8% in 2005, reaching a peak of 37.2% in 2012, and decreasing slightly to 28.8% in 2014. MRSA infections were considered community-acquired in 72% of cases and nosocomial in 28% of cases.

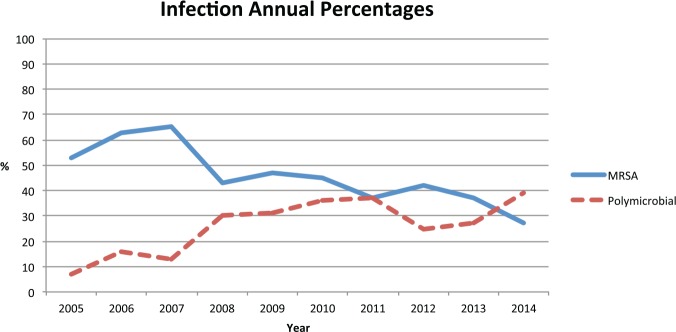

Overall, MRSA was the most common organism grown on culture, followed by MSSA and then group A Streptococcus (Table 2). MRSA was also the most common organism identified in each year of the study period with the following percentages: 53% in 2005, 63% in 2006, 65% in 2007, 43% in 2008, 47% in 2009, 45% in 2010, 37% in 2011, 42% in 2012, 37% in 2013, and 27% in 2014 (Figure 1). There was an overall increase in the number of polymicrobial infections throughout the course of the study with proportions as follows: 7% in 2005, 16% in 2006, 13% in 2007, 30% in 2008, 31% in 2009, 36% in 2010, 37% in 2011, 25% in 2012, 27% in 2013, and 39% in 2014 (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Organisms Identified on Culture.

| Most common organisms |

| MRSA (46%) |

| MSSA (22%) |

| Polymicrobial (22%) |

| Streptococcus pyogenes (8%) |

| Least common organisms |

| Acinetobacter baumannii |

| Acinetobacter calcoaceticus |

| Aeromonas hydrophila |

| Aspergillus species |

| Bacillus species |

| Candida albicans |

| Candida parapsilosis |

| Citrobacter freundii |

| Citrobacter koseri |

| Diptheroid species |

| Eikenella corrodens |

| Enterobacter cloacae |

| Enterococcus faecalis |

| Escherichia coli |

| Fusobacterium species |

| Haemophilus parainfluenzae |

| Klebsiella oxytoca |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| Lactobacillus species |

| Leclercia adecarboxylata |

| Mycobacterium avium complex |

| Pasteurella multocida |

| Peptostreptococcus asaccharolyticus |

| Porphyromonas gingivalis |

| Prevotella species |

| Proteus mirabilis |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| Serratia marcescens |

| Staphylococcus (coagulase-negative) |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis |

| Staphylococcus (alpha-hemolytic) |

| Streptococcus anginosus |

| Streptococcus constellatus |

| Streptococcus (groups B, C, F, and G) |

| Streptococcus intermedius |

| Streptococcus mitis |

| Tissierella praeacuta |

| Veillonella species |

Note. MRSA = methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA = methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus.

Figure 1.

Comparison of annual percentages seen for MRSA and polymicrobial infections.

Note. MRSA = methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

For both intravenous drug users and diabetics, MRSA was the most common organism identified on culture. Intravenous drug users had the highest annual percentages of MRSA infections during each year of the study period; these patients also had variable percentages of polymicrobial infections: 8% of cases in 2005, 35% of cases in 2010, and 29% of cases in 2014. Diabetic patients with hand infections commonly had polymicrobial infections with 36.3% overall (range, 22%-50% per year), with the percentage increasing over time from 33% for 2005-2012 and increasing to 45.7% in 2013-2014. People without comorbidities and intravenous drug users with hand infections also had increasing numbers of polymicrobial infections over time. In 2005, intravenous drug users had polymicrobial infections in 8% of cases, which increased to 29% of cases by 2014.

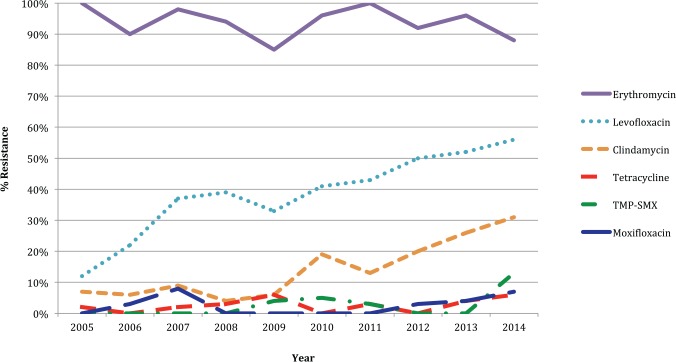

MRSA resistance to clindamycin increased steadily over the 10-year period, reaching its peak in 2014 at 31%. MRSA resistance to levofloxacin also increased over 10 years from 12% in 2005 to 56% by 2014 (Figure 2). Throughout the 10-year period, MRSA was uniformly resistant to ampicillin, oxacillin, and penicillin G. Erythromycin resistance was also very common, ranging from 85% to 100%. There was some sporadic MRSA resistance to tetracycline, moxifloxacin, gentamicin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. There was no resistance seen against gentamicin, rifampin, vancomycin, linezolid, or daptomycin (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Antibiotic resistance to MRSA over time.

Note. MRSA = methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; TMP-SMX = trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Table 3.

MRSA Antibiotic Annual Resistance Percentages.

| Antibiotic | Annual resistance (%) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

| Ampicillin | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Oxacillin | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Penicillin G | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Erythromycin | 100 | 90 | 98 | 94 | 85 | 96 | 100 | 92 | 96 | 88 |

| Levofloxacin | 12 | 22 | 37 | 39 | 33 | 41 | 43 | 50 | 52 | 56 |

| Clindamycin | 7 | 6 | 9 | 4 | 6 | 19 | 13 | 20 | 26 | 31 |

| Tetracycline | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 6 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

| Gentamicin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rifampin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vancomycin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Linezolid | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Daptomycin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Note. MRSA = methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Discussion

MRSA has become an increasing problem in urban hand infections over the last decade as a result of both community-acquired and nosocomial infections.1-3,17,19 Treatment of MRSA hand infections consists of rapid diagnosis, early surgical intervention, and appropriate antibiotic treatment. Appropriate empiric antibiotic selection can be difficult due to rapidly changing sensitivity and resistance profiles. However, the CDC recommends empiric antibiotic treatment if the local rate of MRSA is greater than 10% to 15%.4,5 Therefore, as MRSA has become the predominant organism associated with hand infections in urban medical centers, we sought to examine the epidemiology and antibiotic resistance trends of MRSA hand infections to provide improved and updated recommendations for appropriate antibiotic treatment.

Over the course of our 10-year study, MRSA was grown on culture in 46% of cases, which is well above the level that the CDC uses for recommendation of empiric MRSA antibiotic treatment. This percentage is also consistent with other studies in recent years that have documented MRSA to be found in approximately half of all hand infections.1,7,17,19

Of note, there was increasing MRSA resistance to both clindamycin and levofloxacin over the course of our 10-year review. The resistance to all other antibiotics stayed relatively consistent with consistent resistance to penicillin, ampicillin, oxacillin, and erythromycin. Clindamycin has traditionally been a recommended empiric oral and intravenous agent for the treatment of MRSA hand infections.14 Although we are unable to directly answer why there was increasing clindamycin resistance, we speculate that the increased utilization of clindamycin against MRSA may be the primary cause. Surprisingly, levofloxacin showed linearly increasing resistance to MRSA over the 10-year study period. Traditionally, fluoroquinolones are not selected for treatment of hand infections, but there has been speculation that routine use of fluoroquinolones for other infection including upper respiratory infections may be resulting in increasing resistance to MRSA.10 Our study findings indicate that levofloxacin is also a poor choice in the empiric antibiotic treatment of hand infections. However, moxifloxacin, another agent in the quinolone family, showed only very sporadic resistance to MRSA and could be an effective treatment choice.

MRSA hand infections can be adequately treated with many traditional agents despite resistance to clindamycin and levofloxacin. There was only sporadic resistance seen against tetracycline, moxifloxacin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. There was no resistance seen against gentamicin, linezolid, rifampin, daptomycin, or vancomycin. Vancomycin is the gold standard treatment for MRSA soft tissue infections and remains a first-line agent for empiric intravenous treatment of hand infections.14,17 Linezolid is a newer therapy that is available as both an intravenous and oral formula that is used to treat MRSA; however, its use is limited to selective patients with multidrug resistance MRSA due to its high cost.14

The number of polymicrobial infections increased consistently over the course of the 10-year study, while the number of MRSA infections decreased, presenting a new challenge in the treatment of hand infections. The number of polymicrobial infections surpassed the number of MRSA infections in 2014 with 39% and 27%, respectively. However, this number can be misinterpreted given that MRSA and polymicrobial infections were not mutually exclusive. MRSA was cultured with at least one other organism in 30% of cases. The challenge presented in these cases of hand infections becomes choosing an antibiotic that treats both MRSA and any other associated pathogens, the sensitivity profiles of which may not be routinely tested for in hospital laboratories.

Our study has several limitations. The retrospective design limits the identifiable patients and relies on the accuracy of the medical record for data collection. The pathogens diagnosed by culture are dependent on the quality and accuracy of the aspirate by the provider. Poor technique could result in inaccurate or under-diagnosis of the actual pathogens. In addition, the number of polymicrobial infections may be falsely elevated due to the collection of specimens in unsterile environments or by using poor culture technique. Also, the number of MRSA infections at our institution may be dissimilar to those at nonurban medical centers; therefore, our results may not generalizable to the entire population.

MRSA accounts for about half of all hand infections at urban medical centers throughout the country, including at our urban academic center. As the annual MRSA hand infection prevalence at our center is well above 15%, we routinely avoid empiric antibiotics such as penicillin or its synthetic equivalents, and other beta-lactam antibiotics such as cephalosporins. However, because at our center over the 10-year study period MRSA has become increasingly resistant to clindamycin and levofloxacin, we can no longer recommend these agents for routine empiric treatment of hand infections. However, we do still recommend many other agents for empiric treatment such as vancomycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and daptomycin as no significant resistance of them to MRSA has been documented. Surprisingly, the total number of MRSA hand infections consistently decreased over the past 10 years possibly due to increased vigilance and improved antibiotic treatment based on the best available evidence. Finally, given the increasing number of polymicrobial infections seen over the past 10 years at our center, we believe that more studies are needed for analysis of these infections to further improve antibiotic selection.

Conclusion

Overall, the annual incidence of MRSA hand infections at our urban academic medical center has declined over the study’s 10-year period. However, the overall rate of MRSA hand infections remains high and MRSA also remains the most commonly culture pathogen in hand infections. Also during the 10-year study period, complete resistance to penicillin, ampicillin, oxacillin, and erythromycin did not change, but a large increase in resistance to clindamycin and levofloxacin was noted. Therefore, based on these findings, we would recommend that clindamycin, levofloxacin, along with penicillin and other beta-lactams such as cephalosporins should be avoided for empiric treatment of hand infections. Ultimately, providers should review and consider their local MRSA hand infection prevalence and sensitivity profile to guide empiric antibiotic treatment.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by our institutional review board.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008 (5).

Statement of Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Bach HG, Steffin B, Chhadia AM, et al. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus hand infections in an urban setting. J Hand Surg Am. 2007;32(3):380-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fowler JR, Greenhill D, Schaffer AA, et al. Evolving incidence of MRSA in urban hand infections. Orthopedics. 2013;36(6):796-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fowler JR, Ilyas AM. Epidemiology of adult acute hand infections at an urban medical center. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(6):1189-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gorwitz RJ. A review of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gorwitz RJ, Jernigan DB, Powers JH, et al, et al. Strategies for Clinical Management of MRSA in the Community: Summary of an Experts’ Meeting Convened by the CDC. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Houshian S, Seyedipour S, Wedderkopp N. Epidemiology of bacterial hand infections. Int J Infect Dis. 2006;10(4):315-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Imahara SD, Friedrich JB. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in surgically treated hand infections. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35(1):97-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kowalski TJ, Thompson LA, Gundrum JD. Antimicrobial management of septic arthritis of the hand and wrist. Infection. 2014;42(2):379-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lodise TP, Jr, McKinnon PS. Burden of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: focus on clinical and economic outcomes. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27(7):1001-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. MacDougall C, Powell JP, Johnson CK, et al. Hospital and community fluoroquinolone use and resistance in Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli in 17 US hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(4):435-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. O’Malley M, Fowler J, Ilyas AM. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections of the hand: prevalence and timeliness of treatment. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(3):504-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ong YS, Levin LS. Hand infections. Plast Recontrt Surg. 2009;124(4):225e-233e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Osterman M, Draeger R, Stern P. Acute hand infections. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(8):1628-1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rodvold KA, McConeghy KW. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus therapy: past, present, and future. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(suppl 1):S20-S27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shorr AF. Epidemiology and economic impact of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a review and analysis of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2007;25(9):751-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shorr AF. Epidemiology of staphylococcal resistance [Review]. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(suppl 3):S171-S176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tosti R, Samuelsen BT, Bender S, et al. Emerging multidrug resistance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in hand infections. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(18):1535-1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tosti R, Trionfo A, Gaughan J, et al. Risk factors associated with clindamycin-resistant, methicillin-resistant Staphylo-coccus aureus in hand abscesses. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40(4):673-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wilson PC, Rinker B. The incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in community-acquired hand infections. Ann Plast Surg. 2009;62(5):513-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]