Abstract

In this study, we report the development of a biologically relevant animal model for evaluation of tissue engineering approaches for repair of volumetric muscle loss (VML) injuries to craniofacial muscles (e.g., cleft lip). We also show that the application of in silico methods provides key mechanistic insights for improved understanding of functional regeneration in complex biological systems. Briefly, implantation of a tissue-engineered muscle repair (TEMR) construct into a surgically created VML injury to the rat latissimus dorsi produced significantly greater contractile force recovery than implantation of bladder acellular matrix (BAM) or no repair (NR). Robust de novo muscle regeneration was observed with TEMR, but not NR or BAM. Furthermore, TEMR implantation modified the passive tissue properties of the remodeled implant area. A novel finite-element model suggests that, at optimal muscle fiber length, most of the force recovery is attributed to the passive mechanical properties of tissue in the TEMR-implanted region, which despite significant muscle regeneration is still largely attributable to the greater volume reconstitution promoted by the TEMR implant compared with BAM implant. However, at shorter muscle fiber lengths as well as in larger injury sizes, the presence of active (i.e., regenerated) tissue is required to achieve consistent force recovery.

Impact Statement

Despite medical advances, volumetric muscle loss (VML) injuries to craniofacial muscles represent an unmet clinical need. We report an implantable tissue-engineered construct that leads to substantial tissue regeneration and functional recovery in a preclinical model of VML injury that is dimensionally relevant to unilateral cleft lip repair, and a series of corresponding computational models that provide biomechanical insight into mechanism(s) responsible for the VML-induced functional deficits and recovery following tissue-engineered muscle repair implantation. This unique combined approach represents a critical first step toward establishing a crucial biomechanical basis for the development of efficacious regenerative technologies, considering the spectrum of VML injuries.

Keywords: volumetric muscle loss, functional recovery, finite-element model, cleft lip, rat latissimus dorsi, revascularization

Introduction

Skeletal muscle is a highly organized tissue comprising bundles of striated multinucleated fibers surrounded by intricate extracellular matrix and neurovascular networks. Although skeletal muscle has a rather robust regenerative capacity, a wide range of traumatic injuries as well as congenital and acquired disorders/diseases are known to lead to destruction/absence of muscle fibers and surrounding components,1 resulting in permanent functional and cosmetic deficits.2 These injuries/conditions are collectively referred to as volumetric muscle loss (VML), and despite significant advances in surgical procedures, VML treatment often requires multiple surgical interventions with generally poor cosmetic and functional outcomes. Clefts of the lip (CL) and/or palate are the most common congenital craniofacial malformation affecting 1 in 700 births3–5 and a typical example of VML defect that currently involves multiple surgeries, but may be imminently addressable with emerging tissue engineering technology.

In that regard, a variety of therapeutic strategies are currently under development for the repair of VML to head, neck, and extremity muscles, and similar injury conditions (e.g., abdominal wall repair).6–12 Despite this increasingly robust level of preclinical activity, there are currently only a few published clinical reports concerning the use of biological matrices for muscle tissue repair in patients. In these reports, the investigators described the use of an acellular matrix (e.g., urinary bladder matrix, porcine intestinal submucosa), a material of broad applications to various injuries, for the treatment of VML injuries caused by extremity trauma to the limbs.13–15 While these initial findings are certainly encouraging, only a relatively modest degree of functional improvement was observed,13,14,16 and the underlying biomechanical mechanisms of the limited functional improvement remain elusive. Not surprisingly, there are still no FDA-approved treatments for VML injuries.

Moreover, few studies have focused on injuries/defects applicable to craniofacial muscles, which involve comparatively thin, sheet-like muscles with fiber composition and architecture that differ from extremity muscles. Such differences may substantially reduce the relevance of many extant preclinical and clinical studies to CL repair. In fact, the orbicularis oris muscle (OOM), a thin, sheet-like muscle that encircles the mouth, is the main target of reconstructive surgeries for CL, but patients often face additional surgeries as a result of an incomplete OOM repair, a condition called secondary lip deformity.17

To this end, we have developed a tissue-engineered muscle repair (TEMR) technology platform that provides a promising approach to treat VML and VML-like injuries,18–20 applicable to CL repair. The TEMR construct combines seeding of muscle progenitor cells (MPCs) on an isotropic biological scaffold derived from a porcine bladder acellular matrix (BAM) with subsequent preconditioning via cyclic mechanical stretch in a bioreactor before implantation. While TEMR implantation significantly improves functional recovery (≈60–70% restoration of muscle function) within 2–3 months of implantation in rodent VML injury models,18–20 the small size of the mouse latissimus dorsi (LD) muscle defects (≈20 mg) that have been studied in immune-incompetent animals, in particular, limits clinical applicability to repair of secondary lip deformity in adults. Therefore, development of more biologically and dimensionally relevant preclinical animal models is warranted—such is a major goal of this report.

The development of more clinically relevant animal models will be accelerated by an enhanced understanding of the mechanism(s) responsible for VML-induced force deficits as well as any treatment-based functional recovery. Although some of the pathophysiologic mechanisms limiting repair of VML injury have recently been investigated,21–23 the biomechanical mechanisms underlying the initial functional deficits, as well as any observed functional recovery, remain poorly understood. The latter is a key point, since the basic goal of any VML treatment is to restore functionally relevant force-generating capacity to the injured muscle(s). However, force capacity of intact, injured, and treated muscles is determined by multiple biomechanical factors, including, but not limited to, muscle architecture,24,25 the relative contributions of longitudinal and lateral force transmission,21,26,27 and fiber operating range on the force/length curve.28,29 To date, these biomechanical factors generally have not been rigorously evaluated in the scenario of VML injury and repair.30 Computational models of muscle have been widely used to simulate functions of muscles in the musculoskeletal system31–35; however, none has been applied to understanding the complex mechanics of VML-injured and/or repaired muscles. To address this important knowledge gap, in this article we describe the development of finite-element (FE) models that are capable of reflecting changes in the geometrical, architectural, and mechanical characteristics of skeletal muscles that are commensurate with VML injury and also applicable to VML repair.

The goals of the present work are threefold. The first goal is to evaluate the efficacy of an implantable TEMR construct for functional recovery in a an immune-competent rat LD VML injury model that is biologically (similar to the human OOM in fiber architecture and composition36–39) and dimensionally (8–10 × the size of the mouse LD tested in previous studies18,20) relevant to secondary repair of cleft lip deformity in patients (Supplementary Fig. S1). The second goal is to develop and validate a series computational FE models that accurately depict the function of the intact LD muscle, as well as the VML-injured LD, in both the absence and presence of repair. The third goal is to use FE models to provide key insights into the biomechanical mechanisms responsible for functional deficits caused by VML injuries. These results demonstrate how the predictive capability of computational models will provide guidance for improving existing therapeutic strategies for treatment of VML injuries.

Materials and Methods

BAM preparation

BAM scaffolds were prepared as previously described.19,20,40,41 A brief description of BAM construct preparation is found in the Supplementary Materials and Methods section.

MPC isolation and culture

Rat MPCs, characterized by MyoD and desmin expression as shown in Machingal et al.,20 were isolated from the soleus and tibialis anterior of 4–6-week-old male Lewis rats (Charles River Laboratories) as previously described.18–20,40,41 Briefly, muscles were harvested, sterilized in iodine, and subsequently submitted to consecutives washes in sterile phosphate-buffered saline. Muscles were minced into small pieces by hand and incubated in 0.2% collagenase (Worthington Biochemicals) solution for 2 h at 37°C. To reduce the fibroblast population, muscle tissue fragments were preplated onto 100 mm collagen-coated tissue culture dishes (Corning) for 24 h in myogenic medium containing Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) high glucose supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10% horse serum, 1% chicken embryo extract, and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic (Hyclone). Cells in suspension were then transferred onto 150 mm tissue culture dishes that were coated with Matrigel (1:50 dilution; BD Biosciences) in myogenic medium. Cells were passaged at 70–80% confluence and cultured in growth media composed of low-glucose DMEM supplemented with 15% FBS and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic.

TEMR construct creation

TEMR constructs were generated as previously described.18–20 Briefly, third passage MPCs were seeded in BAM scaffolds at density of 106 MPCs per square centimeter. Constructs were statically cultured in growth media (low-glucose DMEM supplemented with 15% FBS and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic) for 3 days and in differentiation media (F12/DMEM mixture supplemented with 2% horse serum and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic) for 7 days. Constructs were transferred to a specially designed stretch bioreactor and preconditioned with uniaxial mechanical strain (10% strain, 3 stretches/min for the first 5 min of each hour) in growth media.

Animal care

This study was conducted in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act, the Implementing Animal Welfare Regulations, and in accordance with the principles of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The University of Virginia Animal Care and Use Committee approved all animal procedures. A total of 20 Lewis rats (Charles River Laboratories) weighing 305.2 ± 5.9 g at 12–14 weeks old were individually housed in a vivarium accredited by the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care and provided with food and water ad libitum.

Surgical procedures

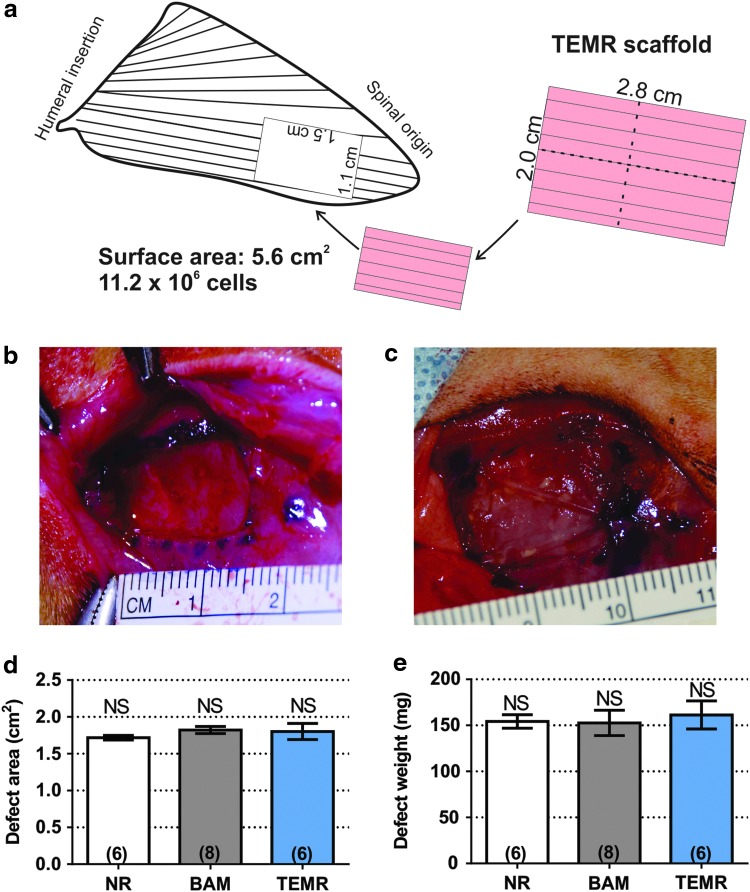

The VML model was created by resecting 1.80 ± 0.04 cm2 area of the LD muscle (dimension: 1.5 × 1.1 cm, muscle thickness: 1–2 mm), which corresponded to 155.6 ± 7.8 mg of tissue and ≈13% of total muscle mass. This injury is closer to the spinal origin and slightly larger than that described previously.42 After the defect creation, animals were assigned to one of the following groups: no repair (NR; n = 6), BAM (n = 8), and TEMR (n = 6). A 7 cm2 scaffold (5.6 cm2 of directly cell seeded area) (acellular for the BAM-implanted group, or MPC seeded and bioreactor preconditioned for the TEMR-implanted group) was folded twice (longitudinally and transversely, see Fig. 1a) and sutured into the wound bed with 6-0 Vicryl sutures (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ).

FIG. 1.

Critically sized VML injury model in the rat LD muscle. (a) Is a schematic representation of LD muscle with a surgically created defect region (injury area: 1.8 cm2) and TEMR construct implantation. TEMR scaffolds (total dimensions: 3.8 × 3 cm) were seeded with 106 MPCs per centimeter of surface area (11.2 × 106 total cells in a 5.6 cm2 area—2 × 2.8 cm), trimmed, and folded twice (once along the short axis and once along the long axis) before implantation. (b) Shows a representative example of an LD VML injury in a male Lewis rat after surgical removal of 1.8 cm2 of muscle, while (c) shows a folded TEMR construct sutured into the wound bed. (d, e) Document that defect area and weight, respectively, were indistinguishable among the treatment groups (p > 0.05 in all cases). Significantly different at the p < 0.05 level after performing a one-way ANOVA. Group sample sizes are listed in parentheses. LD, latissimus dorsi; MPC, muscle progenitor cell; TEMR, tissue-engineered muscle repair; VML, volumetric muscle loss. Color images are available online.

In all groups, fascia and fat pad were sutured over the injury site with 6-0 Vicryl suture, and the skin was sutured with 4-0 Prolene (Ethicon) interrupted sutures, and skin glue was applied between the skin sutures to help prevent the incision opening. Buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg, subcutaneously) was administered for 3 days. At 2 months postimplant, experimental and uninjured contralateral control muscles were removed for ex vivo functional testing and histological analysis. In addition, LD muscle from TEMR-implanted animals (n = 4) and the contralateral control were explanted at 24 weeks postimplant.

Ex vivo muscle function analysis

While under anesthesia, the entire LD muscle of each rat was isolated from the thoracolumbar fascia to the humeral tendon and the tendon and facial ends were tied with 0-0 silk suture (Ethicon). Muscles were transferred to individual chambers of a DMT 750 tissue organ bath system (DMT, Ann Arbor, MI) filled with Krebs–Ringer buffer solution (composition: pH 7.4; concentration in mM: 121.0 NaCl, 5.0 KCl, 0.5 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 24.0 NaHCO3, 0.4 NaH2PO4, and 5.5 glucose; Sigma) at 27°C bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. The muscles were positioned between custom-made platinum electrodes with the proximal tendon attached to a force transducer and the distal tendon to a fixed support. Direct muscle electrical stimulation (0.2 ms pulse at 30 V) was applied across the LD muscle using a Grass S88 stimulator (Grass, Warwick, RI).

Real-time display and recording of all force measurements were performed on a PC with Power Lab/8sp (AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO). Once the LD muscles were mounted in the organ bath, the muscles were used to determine optimal muscle length (Lo) through a series of twitch contractions. Force as a function of stimulation frequency (1, 50, 100, 150, and 200 Hz) was measured during isometric contractions (750 ms trains of 0.2 ms pulses), with 4 min between contractions. The maximal force of contraction, Po, was recorded. Then, the specific force (specific Po) was calculated by normalizing the Po to an approximate physiological cross-sectional area (PCSA), which was calculated using the following equation, where muscle density is 1.06 g/cm3:

Equation 1. Approximate PCSA calculation.

|

Note that the PCSA calculation here is an approximation only appropriate to our force measurement setup for LD. More strict calculations should consider the pennation angle and optimal fiber length.43–45 Consequently, the resulted specific force is also an approximation.

The force/frequency curves were fit to the following dose/response equation:

Equation 2: Dose/response formula

|

where x is the stimulation frequency in Hz, min is the lowest observed force generated, equivalent to the twitch force or Pt, max is the largest observed force or Po, EC50 is the stimulation frequency, which yields half the amplitude of the maximum observed force (Po − Pt), and n is the slope of the linear portion of the force/frequency curve.

Histology, immunofluorescence, and imaging

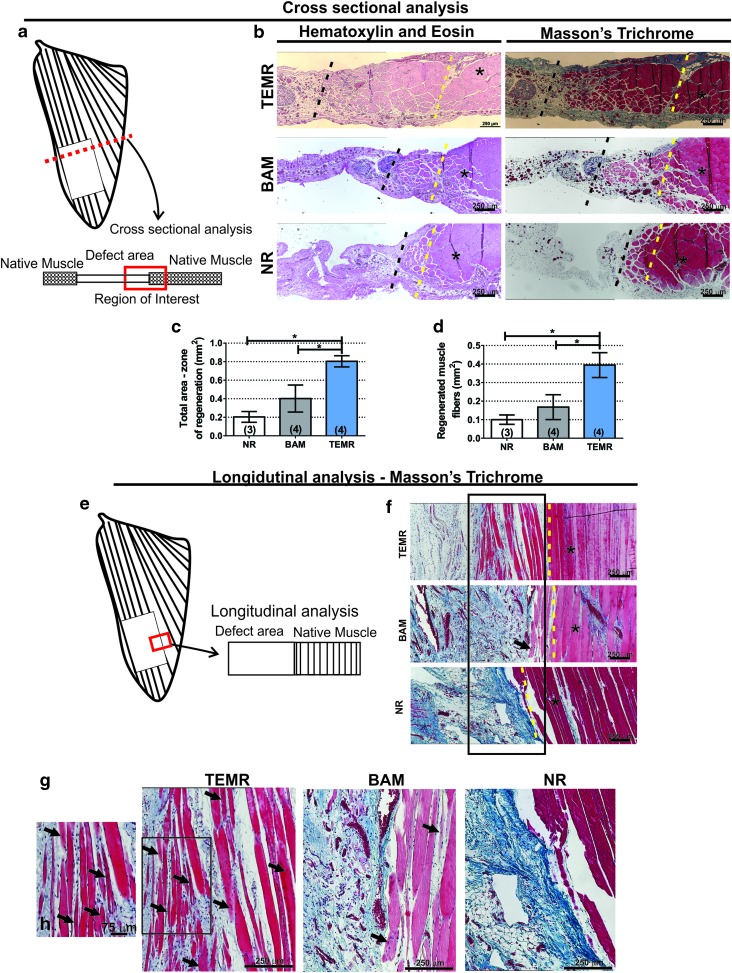

Muscles from all experimental groups were photographed before fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde for 72 h at 4°C. To avoid waterlogging from ex vivo functional testing, muscle samples were treated with a 30% sucrose solution for 72 h at 4°C. For histological analysis, implant area was divided into two portions: the upper half was used for cross-sectional analysis and the lower half was used for longitudinal analysis (Fig. 2a, e). Muscle samples were embedded in paraffin wax and sectioned at 5 μm thickness. Regions of interest for cross-sectional and longitudinal images were taken at interface between native muscle and the implanted area, as shown in Figure 2. Hematoxylin and eosin and Masson's trichrome stains were conducted by standard techniques to determine the basic morphology of cells in and around the implant and to observe any inflammatory response and collagen deposition. Implants retrieved from three to four animals in each treatment group were studied. Images were captured and digitized (Nikon Upright Microscope) at varying magnifications. Zones of regeneration were identified based on morphological changes relative to native, uninjured muscle in the same section (increased fibrosis, reduced fiber diameter, and presence of centrally located nuclei). Quantification of zones of regeneration was performed using ImageJ software (NIH) on cross-sectional images at the interface defect/native tissue. Area containing newly formed muscle fibers (i.e., smaller diameter fibers, with centrally located nuclei and surrounding extracellular matrix) was manually outlined and total area quantified. In addition, individual muscle fibers were also outlined to determine the total area being occupied by muscle fibers.

FIG. 2.

Histological analysis of TEMR-treated LD muscles retrieved 8 weeks postinjury. (a) Depicts the location of the area of interest in the muscle where cross-sectional regions of TEMR-implanted, BAM-implanted, and NR LD muscles were analyzed. (b) Shows cell and tissue morphology in the interface between the native muscle and implant examined through hematoxylin and eosin, in which nuclei are stained blue-purple and cytoplasm and cellular, and Masson's trichrome staining, which stains muscle tissue in red, collagen deposition in blue, and nuclei in black. Dashed yellow line represents the interface between native muscle and VML injury site where the TEMR/BAM was implanted, while dashed black line represents the last point at which detectable myofibers were present (typically within 1–2 mm of the native tissue interface; that is, the yellow line). (c) Depicts quantification of zone of regeneration bounded by the yellow and black dashed lines. (d) Shows total area of muscle fibers comprised between yellow and black dashed lines. Schematic representation of the region in the LD muscle used for longitudinal analysis is shown in (e). (g) Depicts longitudinal sections of retrieved samples from NR, BAM-implanted, and TEMR-implanted treatment groups (n = 3 each) after Masson's trichrome staining. Area enclosed by the rectangle is shown in great detail in (h). *Represents the location of native muscle tissue. Black arrows denote fibers containing centrally located nuclei, and dashed yellow line represents the interface between native muscle and VML injury site/implanted TEMR/BAM. Color images are available online.

Unstained paraffin-embedded slides underwent antigen retrieval protocol (H-3301; Vector Laboratories). Autofluorescence reduction treatment was with 0.3% Sudan black solution for 10 min. Immunofluorescence staining was performed after using antibodies to detect CD31 (anti-rabbit, dilution 1:250; Novus Biologicals NB100-2284), smooth muscle actin (SMA, anti-mouse conjugated to 488 fluorochrome, F3777, dilution 1:250; Sigma Aldrich), and neurofilament 200 (NF200, anti-chicken, dilution 1:1000; EnCor CPCA-NF-H), overnight at 4°C. Secondary antibodies were applied for 2 h at room temperature as follows: Alexa Fluor 647 Fab 2 fragment goat anti-rabbit (dilution 1:500) and Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-chicken (dilution 1:600). Slides were mounted with DAPI containing mounting media and imaged using Leica Inverted Confocal Microscope DMi8, using different magnifications.

Pattern for image acquisition is shown in Supplementary Figure S2. Briefly, analyses were performed in randomly selected animals (n = 3 for each group). For each animal, we acquired six sequential images at the interface muscle/implant and in the center of the implanted area using a 20 × objective for CD31/SMA and NF200 staining (total field of view area = 0.72 mm2). The presence of positive structures was manually quantified in all six fields of view, and therefore, quantification data were normalized by the total replicate measurement (six images). The capillary to fiber ratio (C:F) was calculated by dividing the total number of capillaries by the total number of muscle fibers in the same field of view.

Statistical analysis

Numeric data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. Functional data were statistically analyzed by one-way ANOVA. When significance was found (p < 0.05), a post hoc multiple comparison test was used to compare group means (p < 0.05) using a Fisher least significant difference significance test. Comparison between two groups was performed using t-test (p < 0.05). Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism 6.0 for Windows (La Jolla, CA).

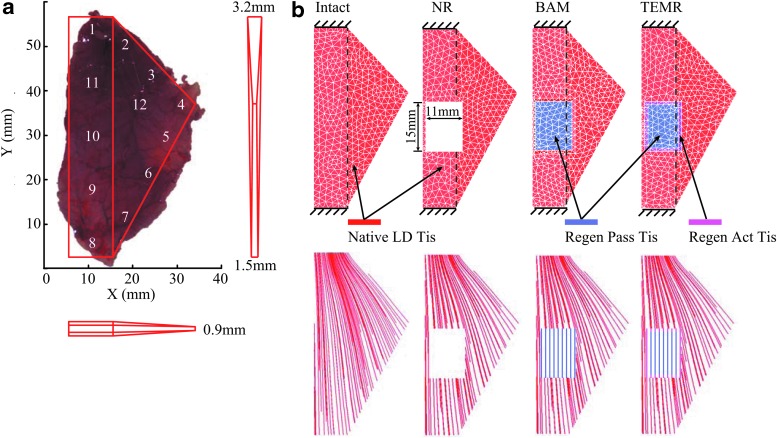

FE model of intact LD

A three-dimensional FE model of the intact rat LD was created based on the average measurements of four dissected LDs from four male Lewis rats (age: 20–22 weeks; weight: 400.4 ± 5.5 g; Charles River Laboratories). The dissected LDs all had similar shapes, areas, and weights. The average area and weight of the LDs are 1117 ± 67 mm2 and 1.74 ± 0.05 g. Therefore, the FE model was built based on one dissected LD and simplified to have a shape of one rectangle plus one triangle to the right in X-Y plane, as shown in Figure 3a. Although the rat LD is a thin, sheet-like muscle, its thickness varies throughout the muscle; therefore, we measured the thickness of the same four dissected LDs with a digital caliper at 12 locations (Supplementary Table S1). In general, the thickness of LD increases from locations 4 to 1, locations 4 to 8, and locations 8 to 1. Thus, to capture this location-dependent thickness of LD while still simplifying the thickness in the Z direction of the FE model, the average thicknesses at locations 1, 4, and 8 were then used to specify the thickness of model at the corresponding locations. The thicknesses of other locations were linearly interpolated (Fig. 3a).

FIG. 3.

FE models of intact LD, NR LD, and BAM- and TEMR-implanted LDs. In (a), three-dimensional shape of the intact LD model was created based on dissected LDs of rat. In (b), FE models of intact LD, NR LD, as well as the BAM-implanted and TEMR-implanted LDs were meshed with four-node-enhanced tetrahedral elements. The fiber directions of native tissue were generated using computational fluid dynamics. The vertical dashed lines indicate the boundaries of rectangular region of the LD models. Color images are available online.

The FE computational mesh of the model was generated using automatic meshing of 4-node-enhanced tetrahedral elements with AMPS software (AMPS Technologies) and included 4149 tetrahedral elements and 1203 nodes. A mesh convergence analysis46 was conducted to ensure that mesh convergence has been reached with the number of elements in the model. The native LD muscle tissue was represented by a hyperelastic material that characterized the nonlinear passive and active force generating abilities of muscles (see the Material Model section).31,47,48

FE models of NR and BAM- and TEMR-implanted LDs in experiments

Three variations of the LD FE model were further developed based on the original model of intact LD to reflect the three experimental groups that were studied following surgical creation of VML defect in the LD, specifically, NR, BAM, and TEMR (Fig. 3b). The FE model for NR was created by cutting out a rectangular space from the intact LD model, consistent with the experimental setup and lack of detectable volume reconstitution in the injured region (only a very thin membrane of connective tissue; Figs. 4f and 2b). The injury had a size of 15 × 11 mm2, and was 17 mm above the bottom end of LD model, which is part of the origin of muscle from the spinal cord. Then, the FE models of BAM- and TEMR-implanted LDs were created by filling the implanted region with materials of different properties.

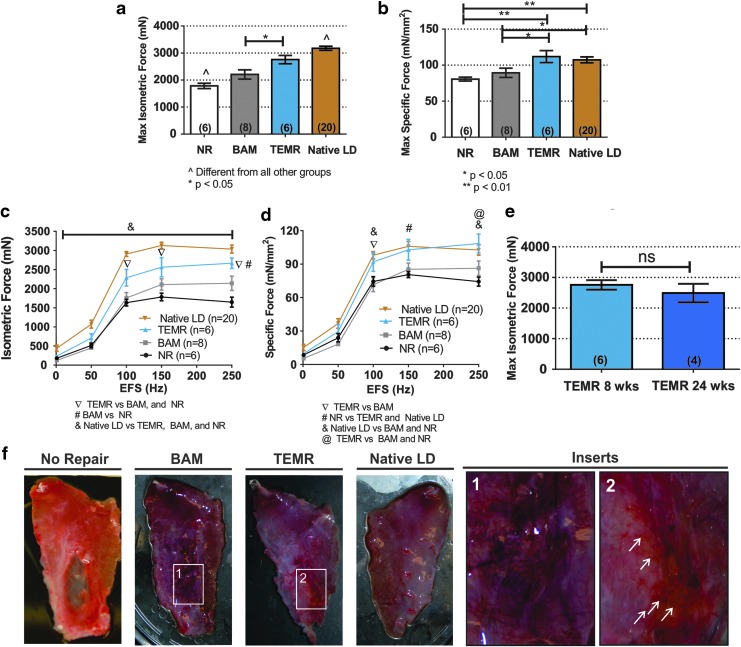

FIG. 4.

LD muscle in vitro force recovery following VML injury and TEMR construct implantation. (a, b) Display maximum isometric contraction force (P0) and specific force (mN/mm2) in response to electrical field stimulation (1–250 Hz, 0.2 ms, 30 V) at 8 weeks postsurgery. The entire dose/response curve for electrical field stimulation of the entire isolated LD muscle is shown in (c, d). (e) Shows maximum isometric force of TEMR-implanted muscle at 8 and 24 weeks, showing durability of contractile response. (f) Provides representative examples of the gross tissue morphology of retrieved LD muscles from the NR, BAM, and TEMR treatment groups 8 weeks postsurgery, compared with their contralateral uninjured LD muscle. White insert provides detailed view of the defect area and its interface with native tissue in (1) BAM-implanted and (2) TEMR-implanted muscles. White arrows highlight the presence of visible vascular network at the implant area. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Significantly different at the p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 level after performing a one-way ANOVA. Group sample sizes are listed in parentheses or in symbol legend. BAM, bladder acellular matrix; NR, no repair; SEM, standard error of the mean. Color images are available online.

Specifically, for the BAM-implanted LD model, the implant region incorporated the experimentally measured passive force generating ability of excised BAM remodeled tissue48 (average of n = 4, see the Material Model section and Supplementary Fig. S3) and had a thickness that was 40% of the implant region of the TEMR-implanted LD, based on the thickness measurements from the histology of retrieved implant samples at 8 weeks postimplantation (BAM: 0.44 ± 0.07 mm [mean ± standard deviation], n = 3; TEMR 0.92 ± 0.11 mm, n = 3). For the TEMR-implanted LD model, the implanted area had two regions: the central region and the peripheral region of 1 mm width (1.33 ± 0.55 mm, n = 3). Both regions had the same passive force generating ability measured from experiments48 (average of n = 4, see the Material Model section and Supplementary Fig. S3). However, the peripheral region had additional active force generating ability equivalent to 60% of active force the native LD can generate, based on muscle fiber measurements from histology (57.6% ± 13.0%, n = 3). The thickness of the remodeled/regenerated implant region of TEMR-treated LD was set to be identical to the portion of the native LD model in the same location.

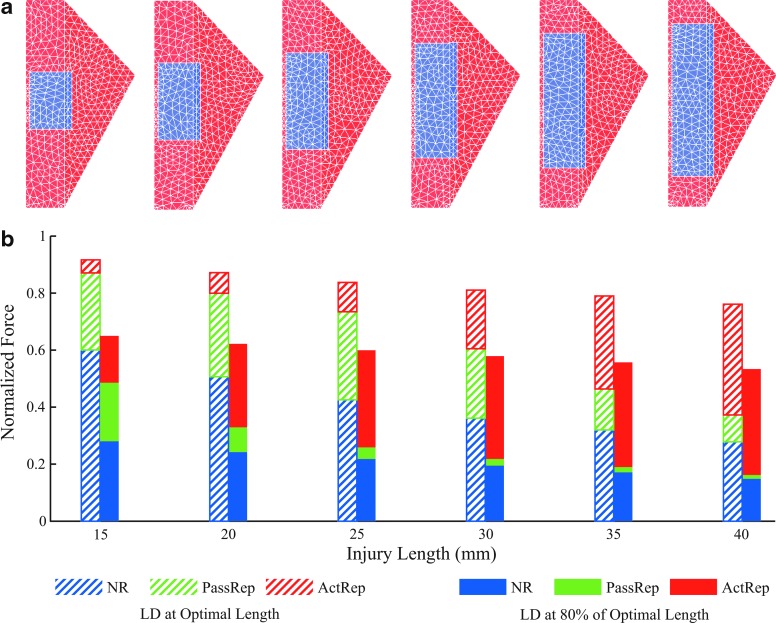

FE models to simulate the influences of injury size on the importance of passive versus active tissue

To explore how the size of injury may influence the relative importance of the regeneration of passive and active tissue on the recovery of muscle with VML injuries, injuries of various sizes were first created in the intact LD and then filled with the same material representing native muscle tissues, in which, however, the maximum activation was set at two different levels. Injuries were centered along the long edge of the rectangular portion of the LD and had a constant width of 11 mm, but various lengths ranging from 15 to 40 mm with an increment of 5 mm. Then, two hypothetical scenarios were simulated, passive repair and active repair, respectively, to look at potential differences in force recovery from purely passive tissue (passive repair; regenerated/remodeled with no evidence of de novo muscle tissue, similar to BAM) compared with the muscle tissue with a combination of passive and active force generating capacity (active repair or muscle regeneration).

Specifically, for the passive repair, the injured muscle region was filled with the same muscle material as intact LD, while its maximum activation was set to 0 so that the filled region can only generate passive force when stretched. Essentially, it was assumed that the regenerated/remodeled tissue had the same passive properties of the native LD. For the active repair, the injured region was also filled with same muscle material as intact LD, but the maximum activation levels were set at 0.5. That is, in addition to the same passive force generating capacity as in the passive repair, the active repair could also actively generate force that was limited to half of the native LD, essentially assuming partial functional regeneration of active muscle tissue.

Material model

The native LD, BAM- and TEMR-remodeled/regenerated tissues, as well as those in the hypothetic scenarios of passive repair and active repair, were all modeled under a transversely isotropic, hyperelastic, and quasi-incompressible material framework that can be used to represent muscle tissue and passive tissue, such as tendon.31,47 This framework assumes a material preferred direction and includes material's response to stretch along, shearing along, and shearing across this direction. The stretch along the preferred direction largely dictates longitudinal force development and transmission in the same direction within material. Shearing along and across the preferred direction are more pertinent to lateral force transmission.26 The constitutive formulation has previously been described in detail,31 and all the material parameters31,32,49 are included in Supplementary Table S2.

For the muscle tissue in the native LD model, the preferred direction of material was along the muscle fiber direction, which was determined using computational fluid dynamics,50 where the fibers traverse from the origin on the spine to the insertion on the humerus (Fig. 3b). These fiber trajectories were then sampled through the mesh to provide the fiber direction for each element on the model. These fiber vectors served as input to the transversely isotopic constitutive model. The response of the material to along-fiber stretch incorporates an active nonlinear force-length relationship of muscle, as given in a study by Zajac,51 and a passive stress-strain relationship measured experimentally from uniaxial tensile testing on native LD muscle tissue48 (average of n = 4, Supplementary Fig. S3), which were scaled by the maximum isometric stress (σmax, obtained from specific force Po measured in our experiments, average of n = 20, see Table 1 and Supplementary Table S2). Specifically, the along-fiber stretch determines where a fiber is on the active force-length and passive stress-strain curves, with value of 1 meaning fiber is at the optimal length (Lo). Passive stress starts to develop, when along-fiber stretch is over 1. Activation level (a), from 0 (no activation) to 1 (maximal activation), was used to scale the active fiber stress.

Table 1.

Summary of Rat Latissimus Dorsi Muscle Functional Measurement Data of Lewis Rat at 8 Weeks After Injury (1.8 cm2) and Folded Construct Implantation*

| Treatment groups | Contralateral control | NR | BAM | TEMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size, n | 20 | 6 | 8 | 6 |

| BW at explant, g | — | 387.3 ± 12.39a | 404.04 ± 9.19a | 408.60 ± 5.05a |

| Wet weight, g | 2.00 ± 0.05a | 1.62 ± 0.07b | 1.69 ± 0.07b | 1.93 ± 0.07a |

| Lo, mm | 63.59 ± 2.00a | 69.72 ± 4.33a | 64.76 ± 2.10a | 73.17 ± 1.89a |

| PCSA, mm2 | 29. 95 ± 0.69a | 22.22 ± 1.35b | 24.81 ± 1.27b | 24.97 ± 1.25b |

| Isometric force parameters | ||||

| Pt, N | 0.44 ± 0.08b | 0.18 ± 0.03a | 0.13 ± 0.03a | 0.24 ± 0.02a,b |

| Po, N | 3.17 ± 0.07a | 1.78 ± 0.10b | 2.21 ± 0.17c | 2.76 ± 0.16d |

| Specific Po, mN/mm2 | 107.33 ± 4.13b | 80.62 ± 2.66a | 89.37 ± 6.47a | 111.86 ± 8.29b |

| ED50, Hz | 56.37 ± 6.55a | 67.60 ± 6.46a | 84.38 ± 4.42a,b | 80.86 ± 5.33a,b |

| n Coefficient | 8.81 ± 0.82c | 6.36 ± 0.61a | 10.40 ± 0.57a,b | 11.02 ± 0.61b,c |

Values are mean ± standard error of the mean. Values denoted with the same letter are not significantly different (p > 0.05), while values without a like letter denotation are significantly different (p < 0.05). Peak twitch response (Pt) and maximal isometric contraction force (P0) were measured by soliciting contractions through direct electric stimuli (0.2 ms, 30 V) in the organ bath setup. Measured Po was normalized to PCSA to determine specific force (Specific Po). The stimulation frequency, which yielded 50% of the absolute maximum amplitude (ED50), and the slope of the linear portion of the force/frequency curves (n coefficient) were determined by fitting the curves to function, described by Equation (2).

See Fig. 1 for details.

BAM, bladder acellular matrix; BW, body weight; L0, muscle length; PCSA, physiological cross-sectional area; NR, no repair; TEMR, tissue-engineered muscle repair.

For the BAM- and TEMR-implanted LD models, the material preferred direction of BAM- and TEMR-regenerated/remodeled tissue was assumed to be straight in the vertical (Y) direction, and the remaining native muscle tissue had the same fiber direction as in the intact LD model (Fig. 3b). The passive material responses of the BAM- and TEMR-regenerated/remodeled tissue to the stretch along the preferred material direction were represented by the stress-strain relationships of corresponding tissue excised from implant region and experimentally measured via uniaxial tensile testing48 (average of n = 4, each group, Supplementary Fig. S3), which were also scaled by the peak isometric stress (σmax). The BAM-regenerated/remodeled tissue was assumed completely passive, while the TEMR-regenerated tissue had a peripheral region of 1 mm width that had ∼60% regenerated muscle fiber based on histological analyses on the zone of regeneration (average of n = 3). This region was modeled to follow the same active force-length relationship of native LD but was limited to have maximum activation of 0.6.

In the simulated passive repair and active repair scenarios, the muscle material of the native LD muscle was used to represent the regenerated/remodeled tissue, but with different settings of maximum activation levels. In the passive repair, the muscle material was set to have maximum activation level of 0, whereas in the active repair, the maximum activation was set at 0.5. The fiber direction was assumed to be straight in the vertical (Y) direction, and the remaining native muscle tissue had the same fiber direction as in the intact LD model (Fig. 3b).

Simulations of isometric contractions

To compare and validate our models with experimental results, simulations of isometric contractions of the models of the intact LD and NR and BAM- and TEMR-implanted groups were performed with two ends of the LDs fixed at the optimal fiber length that replicated the experimental setup during the ex vivo muscle function analysis (Fig. 3b). In the hypothetical passive repair and active repair, first, the same isometric contractions were simulated at the optimal fiber length with models having various sizes of injuries. Then, to further examine the influences of the muscle length on the force generation of NR LD and LDs with passive repair and active repair, respectively, additional simulations of isometric contractions were performed at 80% of optimal fiber length, a physiologically relevant muscle length in humans.52,53 Muscle activation levels were set at maximum activation for all the simulations. We used Sefea™ (Strain-Enriched FEA; AMPS Technologies) solver with explicit strain energy function specification to run the simulations.54 The predicted forces from the models of the intact LD, as well as the LD in the NR, BAM, and TEMR treatment groups, were recorded and compared with the actual experimental data for validation. Then, the predicted forces from models of the NR LD and passive and active repair were also recorded under various injury sizes (injury length from 15 to 40 mm) and at two muscle lengths (100% and 80% of Lo). These recorded forces were then normalized to the force at the optimal length (Fo at Lo) of the intact LD for comparison.

Results

Creation of rat LD VML injury model and ex vivo functional assessment

The weight and area of muscle excised from the animals in each treatment were statistically identical (p > 0.05), reflecting the creation of comparable VML injuries across treatment groups: NR (n = 6, 1.72 ± 0.03 cm2, 153.8 ± 6.6 mg), BAM (n = 8, 1.88 ± 0.07 cm2, 152.6 ± 13.7 mg), and TEMR (n = 6, 1.80 ± 0.11 cm2, 161.3 ± 15.2 mg) (Fig. 1). TEMR constructs and acellular BAM scaffolds were sutured into the wound bed as previously described.18–20 Ex vivo force measurements were performed 2 months postinjury on the experimental and contralateral control muscles from all three treatment groups. Mean values for all parameters of interest derived from measurements are listed in Table 1, and the results for Po and specific Po are displayed in Figure 4.

Of note, 2 months postinjury, both the mean maximal isometric and specific force responses of nonrepaired VML injuries were reduced to 56.2% ± 3.1% and 75.1% ± 2.5% of the contralateral uninjured control responses, respectively (Table 1 and Fig. 4). The impact of BAM implantation on recovery of maximum isometric force and specific force measurements was limited to 69.52% ± 5.43% and 83.27% ± 6.02% of contralateral native control responses, respectively (Fig. 4a, b). However, after TEMR implantation, maximum isometric force and specific force were significantly greater than the NR and BAM groups (p < 0.05), achieving 86.85% ± 4.92% and 104.22% ± 7.72% of contralateral control values, respectively, although there is no statistical difference in specific force between TEMR and contralateral control.

As shown in Table 1 and consistent with previous reports,18,41 at the time of tissue retrieval, the mass of LD muscle from uninjured contralateral control and TEMR-implanted animals was significantly heavier than tissues from the BAM and NR groups. Also detailed in Table 1, analyses of force/frequency fitted curves show an increase in half-maximal effective dose (ED50; the stimulation frequency that yielded 50% of the absolute maximum contraction amplitude) in BAM (84.38 ± 4.42 Hz) and TEMR (80.86 ± 5.33 Hz) groups, compared with uninjured contralateral control (56.37 ± 6.55 Hz). Finally, to better illustrate the magnitude of functional recovery after TEMR treatment, the entire isometric and specific frequency/response curves are shown in Figure 4c and d, highlighting the impact of TEMR implantation on functional recovery relative to BAM and NR. In addition, maximal isometric force of TEMR-implanted muscle was sustained at 6 months postimplantation (Fig. 4e).

Gross tissue morphology

Representative images of retrieved LD muscles from each treatment group are shown in Figure 4f. TEMR constructs were well tolerated and appeared to be integrated with native tissue, with clear macroscopic evidence of vascularization at 8 weeks postimplantation, while the NR group lacked new tissue formation and the BAM group showed signs of fibrosis in the implanted area.

Histological analysis

Three retrieved samples from each treatment group were longitudinally and transversely sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin and Masson's trichrome. A schematic illustration of the regions of interest is provided in Figure 2a and e, and the main focus was to identify and analyze the interface between the implant or injured area and the remaining native muscle tissue. In TEMR-implanted muscles, the interface revealed a “zone of regeneration” that was characterized by the presence of active tissue components (muscle fiber, innervation, and vasculature) as well as hallmark traits of regenerating muscle (i.e., centrally located nuclei and small-diameter fibers).40 As expected, the wound bed was easily identified in the NR, which was marked by the lack of muscle and a very thin membrane of connective tissue that filled the gap created by the surgical removal of tissue; in the absence of any detectable volume reconstitution (Fig. 2). BAM-implanted muscles revealed limited volume reconstitution characterized by the presence of fibrotic tissue, but minimal evidence of new muscle fiber ingrowth into the wound bed. In stark contrast, TEMR-implanted muscles showed not only an even greater volume reconstitution than BAM-implanted muscles but also ingrowth of a considerable amount of small striated muscle fibers containing centrally located nuclei.

In fact, quantitative analysis showed that TEMR-implanted muscles had a significantly greater zone of regeneration when compared with NR and BAM-implanted groups (TEMR: 0.80 ± 0.1 mm2; BAM: 0.40 ± 0.14 mm2; NR: 0.20 ± 0.05 mm2; p < 0.05) (Fig. 2c), as well as a consistently greater muscle fiber containing area (TEMR: 0.40 ± 0.06 μm2; BAM: 0.17 ± 0.07 μm2; NR: 0.10 ± 0.02 μm2; p < 0.05). In addition, the C:F in the “zone of regeneration” in the TEMR-implanted animals was 0.77 ± 0.04 (n = 3), equivalent to previously described C:F ratios for healthy LD muscle across different species,55–57 and also, significantly greater than the C:F ratio observed in BAM-implanted samples of 0.25 ± 0.05 (n = 3, p < 0.05 after Student's t-test) (data not shown).

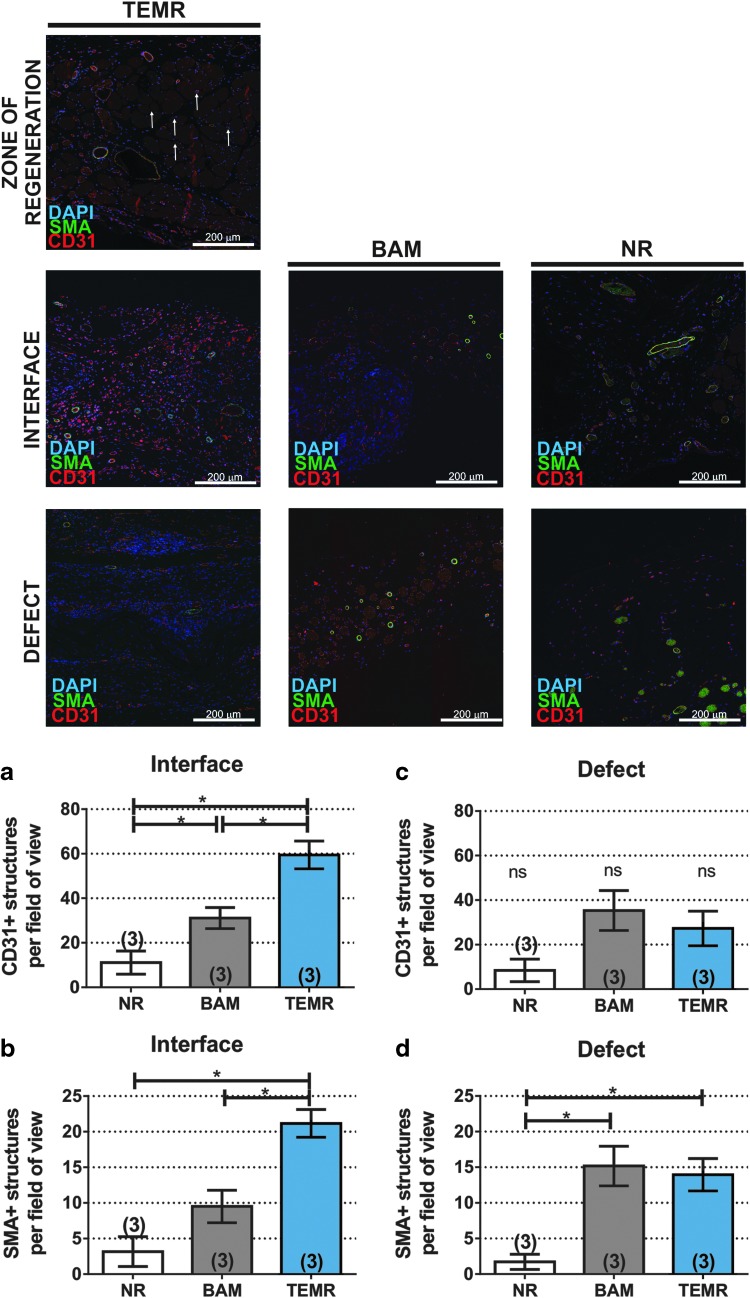

Immunofluorescence analysis

Images at the interface of the muscle/implant and center of the implanted area were also analyzed to assess the neurovascular network supplying the implant/defect area 8 weeks postinjury (see schematic representation of areas of interest shown in Supplementary Fig. S2). TEMR implantation promoted greater vascular network ingrowth into the wound bed, as seen by the augmented presence of CD31+ and SMA+ structures per field of view in the interface with muscle area in TEMR-treated samples compared with the BAM treated and NR (Fig. 5a, b), and qualitatively increased neuron infiltration into the TEMR implant, compared with BAM and NR (Supplementary Fig. S4).

FIG. 5.

Representative CD31 and SMA staining 8 weeks after LD VML injury repair. CD31-positive capillaries are shown in red, SMA-positive cells are shown in green, and DAPI-stained nuclei are shown in blue. See Supplementary Figure S2 for schematic representation of location of each area. Zone of regeneration panel depicts vascularization of newly formed fibers in TEMR-implanted muscles (see text for quantification of C/F). White arrows indicate representative capillaries. Interface panel depicts vascularization in the construct adjacent to native muscle fibers, and defect panel depicts vascularization in the construct 2+ mm away from the muscle fibers. (a–d) Show quantification of CD31-positive and SMA-positive structures in the interface and defect area (see the Materials and Methods section for quantification details). TEMR implantation was associated with augmented vascular network infiltration at the interface between the native muscle and implanted construct in areas adjacent to muscle fibers. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *Significantly different at the p < 0.05 level after performing a one-way ANOVA. Group sample sizes are listed in parentheses. C/F, capillary to fiber ratio; SMA, smooth muscle actin. Color images are available online.

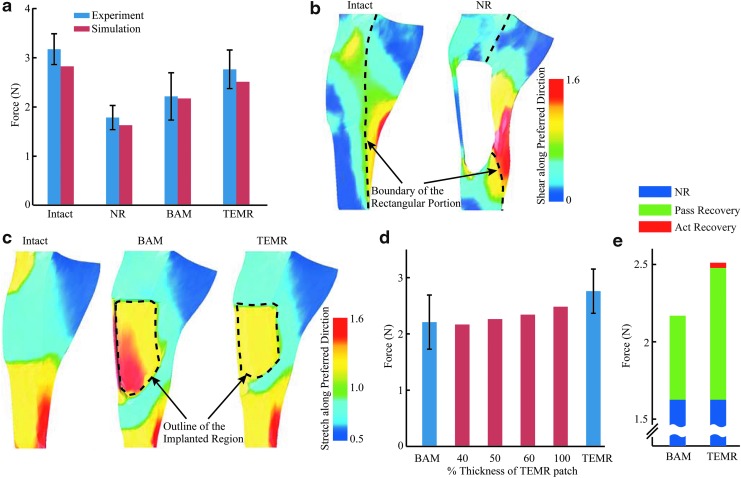

Simulation-predicted LD forces measured from experiments

The simulation-predicted forces were all in good agreement with the experimental results, which validated our models (Fig. 6a). The simulation predicted a maximum isometric force of intact LD model of 2.82 N. When a 165 mm2 area was cut out in the intact LD model to simulate injured LD treated with NR, the simulation-predicted force dropped to 1.62 N. After the injured area was repaired with materials that simulated BAM and TEMR treatments, the simulation-predicted forces recovered to 2.17 and 2.51 N, respectively. The slight differences (roughly 8% on average) could be attributed to a potentially small underestimation of the specific force Po in the experiment, which was then used as a material parameter (σmax) in simulations.

Fig. 6.

FE simulation-predicted LD forces and the associated biomechanical mechanisms. In (a), there was a good agreement between simulation-predicted maximum isometric forces and experimental observations for the intact LD as well as VML injured LDs from the NR, BAM-implanted, and TEMR-implanted groups. In (b), in the NR LD, large shear strain along the preferred material direction in the region to the right side of the injury indicated substantial lateral force transmission. In comparison, much smaller shear strain was observed in the similar region in the intact LD. In (c), regenerated/remodeled tissues in the implanted regions of BAM-implanted and TEMR-implanted LDs were substantially stretched beyond their original length (stretch >1), indicating large longitudinal force transmission. In (d), improved force recovery in the TEMR-implanted LD was primarily caused by a larger thickness of the regenerated/remodeled tissue. In (e), force recoveries in the BAM-implanted and TEMR-implanted LDs were largely resulted from passive force generating ability of the regenerated tissue. All experimental data were shown as mean ± standard deviation. FE, finite-element. Color images are available online.

Simulation reveals biomechanical mechanisms underlying force recoveries

The simulation results demonstrated that different mechanisms contributed to force transmission in NR LD muscles compared with the force recovery observed following BAM and TEMR implantation. Despite an injury encompassing 90% of the fibers in the rectangular portion of LD (see the Materials and Methods section and Fig. 3b) that interrupted longitudinal force transmissions in the injured region, force in the NR LD was more than half of the force generated by intact LD (Fig. 6a). Analysis of the model revealed that much of the residual force can be primarily attributed to lateral force transmission across the remaining native LD tissue surrounding the injury (large shearing along preferred fiber direction in Fig. 6b).26 In contrast, following implantation of BAM and TEMR, recovery of longitudinal force transmission from the increased volume of tissue in the implanted region was associated with an increase in LD contractile force (Fig. 6a). This was evidenced by substantial stretch beyond the original length of the new volume of tissue in the implanted region (stretch >1 in Fig. 6c).

In this setting, the force recovery in the BAM- and TEMR-implanted LDs (at Lo) largely resulted from the passive force generating ability of the increased volume of tissue in the implanted region of LD. Since the BAM-treated tissue was modeled purely as passive tissue, all of the observed force recovery was from improved passive force generating ability of the repaired tissue in the BAM-implanted region of LD muscles (Fig. 6e). In contrast, TEMR-implanted LD muscle was modeled to have passive tissue in the central region and suboptimal active muscle tissue in the peripheral region (i.e., zone of muscle regeneration near the native tissue interface) that was ∼28% of the total injured region. However, when the whole injured region was modeled as completely passive (by setting the activation of muscle tissue to 0.0), the force was recovered to 2.48 N. In this scenario, activating the muscle tissue in the zone of regeneration only provided additional force recovery of 0.03 N (Fig. 6e). Therefore, the passive force-generating ability of the tissue in the implanted region accounted for 96% of the total force recovery following TEMR implantation (at Lo). Furthermore, sensitivity analyses46 conducted by varying the maximum activation level (0.4 ∼ 0.8) and the width (0 ∼ 2 mm) of peripheral active “muscle” tissue in the plausible ranges reflected in histological analysis of TEMR-implanted LD muscles had minimal impact on total force recovery at Lo (Supplementary Fig. S5).

As such, the model suggests that at Lo, improved force recovery following TEMR implantation versus BAM implantation was primarily caused by the increased thickness/volume of the tissue that resulted from the inclusion of cells in the TEMR construct after 8 weeks. More specifically, although the average passive stress-strain relationships of the retrieved BAM- and TEMR-implanted regions of the LD muscle were similar (Supplementary Fig. S3; n = 4, each group), the TEMR-implanted region was more than two times thicker than the BAM-implanted region (TEMR-implanted tissue: 0.92 ± 0.11 mm; BAM-implanted tissue: 0.44 ± 0.07 mm; n = 3, each group; mean ± standard deviation). Thus, as the TEMR-implanted region of the LD became thicker, the increased stiffness resulted in greater longitudinal force transmission from the remaining native tissue, leading to improved force recovery of TEMR-implanted LD, compared with BAM-implanted LD (Fig. 6d). It is worth noting that our simulation results intend to explain main differences in force recoveries in various groups with model parameters based on average experimental measurements. The variations in stress-strain curve (shaded regions in Supplementary Fig. S3) may give rise to slight variations in the model-predicted force output for each individual LD, similar to the experimentally measured variations in LD forces (Fig. 6a).

The importance of active muscle tissue varies with the size of VML injury

At optimal length (Lo), the existence of active muscle tissue becomes increasingly important as the injury size increases. When the injury size increased, the NR LD model predicted forces that decreased from 60% to 28% of maximum isometric force (Po) of intact LD at Lo (Fig. 7b, blue portions of hatched bars). When the injured region was repaired/replaced entirely with passive tissue (passive repair; BAM), force recovery was maintained at about 30% of Po for injury lengths from 15 to 25 mm, but declined with increased injury length (Fig. 7b, green portions of hatched bars). For the largest injury (40 mm), the force recovery from passive-repaired LD was only 9% of Po. As a result, there were drastic changes in force generation (blue+green portions of hatched bars) by the LD in the presence of passive repair only, as reflected by a reduction in Po from 87% to 37%, when the injury size increased. In contrast, the additional force recovery produced by LD models that were repaired by active muscle tissue (active repair or muscle regeneration) grew substantially from 5% to 39% of Po, when the injury length increased from 15 to 40 mm (Fig. 7b, red portions of hatched bars). Furthermore, simulated force generation in LDs in the presence of active repair (blue+green+red portions; TEMR implantation) was much more resistant to the decline in force with increasing injury size (i.e., increased length) than the force generation with passive repair (i.e., BAM implantation); in fact, only a moderate reduction from 92% to 76% of Po was observed for TEMR, compared with from 87% to 37% with BAM.

FIG. 7.

The importance of active muscle tissue varies with the size of VML injury and muscle length. Shown in (a) are VML injuries created with a constant width of 11 mm, but various lengths ranging from 15 to 40 mm with an increment of 5 mm. All the injuries were identically centered along the long edge of the rectangular portion of the LD. (b) Shows normalized forces from injured LDs that were NR, repaired with a passive tissue component (passive repair), or repaired with an active tissue component (active repair) at 100% and 80% of optimal length. The blue bars indicate the forces of NR; the green bars indicate the recovery from NR after passive repair was applied; and the red bars indicate the additional recovery after active repair was applied. Color images are available online.

The importance of active muscle tissue also varies with the muscle length

The importance of active muscle tissue is further elevated at 80% of the optimal length (Lo). Overall, at a shorter length, the simulated forces from NR LDs, and both the passive repair and active repair, were all lower than at Lo. However, the shorter length had much more substantial influences on the passive repair compared with the active repair. For the passive repair, force recovery was markedly reduced from 21% to 9% of Po when the injury length increased from 15 to 20 mm, and little force recovery was achieved (<5% Po) when injury lengths were longer than 20 mm (Fig. 7b, green portions of solid bars). As a result, force generation was reduced from 49% to 16% of Po (blue+green portions of solid bars). In stark contrast, active repair resulted in increased force recovery from 16% to 37% of Po when the injury length increased from 15 to 40 mm (Fig. 7b, red portions of solid bars), resulting in robust force generation above 50% of Po (blue+green+red portions). In this scenario, it is plausible that the degree of TEMR-mediated muscle regeneration observed herein contributes to contractile responses at shorter muscle lengths—that were not measured in this work—thereby enabling improved muscle function over a greater operational range of muscle lengths than NR or implantation of BAM.

Discussion

The ultimate goal of an implantable tissue engineering technology for treatment of VML defects is scarless wound healing with complete functional regeneration. Suffice to say that, despite recent progress, there is still plenty of room for therapeutic improvement. Development of more efficacious therapeutics, in turn, requires not only validated and biologically relevant animal models suitable for the proposed corresponding human clinical applications but as importantly significant increases in our understanding of the putative mechanism(s) responsible for those functional improvements as well. As a first step in this direction, we report that a combination of in silico and in vivo approaches provides unique information and critical biomechanical insights into VML-mediated force deficits, as well as mechanisms of contractile force recovery in a rodent model of VML injury and repair, having a direct clinical application to craniofacial reconstruction in patients, such as secondary revision of unilateral cleft lip (Supplementary Fig. S1).

We demonstrated that implantation of the TEMR construct at the site of VML injury promoted significant tissue reconstitution/regeneration and ∼90% functional recovery in a rat VML defect that is biologically and dimensionally comparable with potential defects seen in the OOM of adults facing reconstructive surgery for secondary lip deformity. Importantly, the size of defects in the current study is eight times bigger compared with those in our previous studies,18,20 which marks a major step toward human clinical applications. In addition, unlike previous studies focusing on limb muscles,7,8,10,11,19 which differ from craniofacial muscles in gross anatomy and physiological properties, our study was selectively designed on the rat LD muscle, a sheet-like and pennate muscle, with parallel fiber orientation along its ventral portion that mimics size, arrangement, fiber type, thickness, and anchoring of human OOM.37–39 In this newly developed, critically sized VML injury model, our results also showed major advantages of a TEMR-based treatment over an acellular BAM-based treatment (Table 2). Moreover, advantages were durable up to 6 months postimplantation (Figure 4e), indicating its applicability for repair of secondary lip deformity in adults.

Table 2.

Summary of Advantages of Tissue-Engineered Muscle Repair Over Bladder Acellular Matrix Scaffold Alone

| Parameter | Treatment | Ratio TEMR/BAM | Figure and Table reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEMR | BAM | |||

| Maximum isometric force of contraction Po, N | 2.76 ± 0.16 | 2.21 ± 0.17 | 1.25 | Fig. 4 and Table 1 |

| % Force deficit recoverya | 71 | 32 | 2.22 | Fig. 4 and Table 1 |

| Specific Pob | 104% | 83% | 1.25 | Fig. 4 and Table 1 |

| Implant thickness, mm | 0.92 ± 0.11 | 0.44 ± 0.07 | 2.1 | Fig. 6 |

| Zone of regeneration,c mm2 | 0.80 ± 0.1 | 0.40 ± 0.14 | 2.0 | Fig. 2c |

| Area filled with muscle fiberd | 0.40 ± 0.06 | 0.17 ± 0.07 | 2.4 | Fig. 2d |

| CD31 expression interface | 59.44 ± 6.23 | 36.83 ± 4.76 | 1.61 | Fig. 5a |

| SMA expression interface | 21.17 ± 1.95 | 9.50 ± 2.28 | 2.22 | Fig. 5b |

| C:F ratio | 0.77 ± 0.04 | 0.25 ± 0.05 | 3.1 | Results—Histological analysis |

Bold reflect improved contractile force, italics reflect improved volume and quality of volume composition, and bold-italics reflect improved vascularization.

Calculated as follows: At 2 months NR had a 44% force deficit relative to contralateral control (56% of control Po), TEMR was 87% of control Po for a 31% recovery of a 44% force deficit, or 71% total force deficit recovery, and BAM 70% of control Po for a 14% recovery of the same 44% force deficit or 32% force recovery.

An assessment of the “quality” of contraction postinjury relative to contralateral control.

The zone of regeneration, defined as the entire area from the native tissue interface to the most distant observable muscle fiber.

Area within the zone of regeneration that comprised muscle fibers.

SMA, smooth muscle actin.

The corresponding FE simulations, which are the first that we are aware of, illustrated the mechanisms of the force deficit induced by a VML injury created in the rat LD. Application of the FE simulations revealed that the apparent discrepancy between the predicted (≈90% if based on the interrupted parallel-align fibers) and observed (≈40% in experiment) reduction in contractile force induced by VML injury was primarily due to the presence of lateral force transmission in the remaining uninjured pennate portion of the muscle. These results are consistent with previous work demonstrating the functional importance of lateral force transmission, as characterized by shearing among fibers.26,27 This observation seems particularly significant in the context of the spectrum of potential VML injuries, in which the longitudinal force transmission is interrupted and the lateral force transmission is utilized by remaining tissue to bypass the injured region.21,58

Coupled with experimental observations, our FE simulations provide mechanistic insights to explain improvement in force recovery after TEMR-based treatment. Based on histological analysis, TEMR-treated muscles showed a greater zone of regeneration (active tissue; Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. S4) as well as a greater volume of reconstitution in the implant region than the BAM-treated muscles (Fig. 2b). However, experimental observations alone could not accurately differentiate which mechanism was primarily responsible for the better recovery in TEMR-treated muscles. In contrast, the FE model and the associated sensitivity analyses based on these experimental observations clearly indicate that, at optimal length (Lo), the observed de novo muscle regeneration (i.e., new active tissue formation) was responsible for only a small percentage of increased functional performance (Fig. 6e). This indication has important implications to the extant literature, where implantation of a BAM scaffold alone in similar sized VML injuries has been shown by us and others, to produce relatively modest degrees of functional recovery; and in some cases none at all.18–20,59–61 As revealed by our FE model, when experiments were performed at the muscle's optimal length, the main driver of better force recovery after a 165 mm2 injury was the significantly greater extent of volume reconstitution promoted by TEMR implantation compared with BAM implantation (Fig. 6e).

Importantly, TEMR implantation altered tissue composition beyond the formation of active tissue. TEMR implant induced a greater volume reconstitution of passive tissue in the defect area and supported improved ingrowth of neural/vascular network (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. S4), which led to better longitudinal force transmission. The insights from the simulation results not only explain the different levels of functional recoveries in BAM and TEMR in the current study but also corroborated previous speculations10,42,61 that improved longitudinal force transmissions by passively remodeled tissue may be responsible for functional recovery.

However, regeneration of active muscle tissue is clearly needed to achieve consistently high degrees of functional recovery to VML injuries, especially for progressively larger injuries and at suboptimal muscle lengths (i.e., below Lo). More specifically, our simulations indicated that as the injury size increases, the contribution of passive tissue (i.e., volume reconstitution) to force recovery decreases. This adverse effect is especially devastating at muscle lengths shorter than optimal length (80% Lo in simulation). These results from our simulations are in agreement with recent experimental studies suggesting that force recovery led by passive tissue alone may not be conserved in larger VML defects23 and that force deficits may be worse when muscle is shortened below Lo.25,30

Obviously, increased injury size translates into a larger area containing passive tissue and a smaller area of remaining active muscle tissue. Under such conditions, the stretch of a larger area of passive tissue causes the remaining active muscle tissue to shorten to a less optimum location on the active force‐length curve, leading, in turn, to a smaller force producing capacity. Parallel shortening of the overall muscle length to 80% of Lo required the remaining active muscle tissue to shorten even more, further reducing the force generating capacity of the remaining active muscle tissue—as passive tissue (non-muscle volume recovery) still had to be stretched beyond its resting slack length to generate force. The major advantage of having a combination of regenerated active and passive tissues (active repair) over passive tissue alone (passive repair) is the added capacity of force generation at suboptimal lengths, which ensures consistent force recoveries across a wide range of injury sizes and operating muscle lengths.

Different roles played by active and passive tissue during tissue regeneration have important implications in the development of more efficacious tissue engineering and regenerative medicine technologies. First, passive tissue alone may be sufficient to treat relatively small injuries. Although de novo muscle tissue regeneration, comparable with native muscle tissue, by definition, results in the best force recovery, volume reconstitution by passive tissue alone may produce physiologically acceptable degrees of force recovery, in the absence of complete muscle regeneration, especially for small injuries. However, note that, as discussed above, the efficacy of passive tissue-mediated repair will drastically decline, when the injury size increases. Second, as muscles work in or beyond the range of 20% shorter than Lo in humans,52,53 this passive tissue-based recovery may contribute to a widespread range of functional outcomes, thus at least partially accounting for mixed clinic trial results following implantation of scaffold alone.15 Therefore, the recovery of muscle force after repair may need to be assessed not only at the optimal length, as currently done in numerous experiments,18,20,42,62 but also at various other lengths, especially at lengths shorter than the optimal length to ensure consistent functional recovery.30 Such future studies may further highlight the importance of the degree of TEMR-mediated muscle regeneration observed herein.

Conclusions

We have established a biologically relevant and scalable animal model for evaluation of tissue engineering approaches for repair of VML injuries/defects to craniofacial muscles (e.g., cleft lip). We illustrate, for the first time we are aware of, how the parallel development of computational FE models provides important insights for improved understanding of mechanisms of functional regeneration in complex physiological systems. In short, following implantation of regenerative therapeutics (e.g., TEMR), volume reconstitution per se is sufficient to elicit improved maximal isometric force (i.e., contractile function) at optimum muscle length—at least for the biologically relevant and clinically applicable VML injuries that were the subject of this study.

However, TEMR implantation was also associated with the presence of robust (compared with BAM and NR), although incomplete, de novo muscle regeneration, and it is plausible that this degree of muscle regeneration contributes to contractile responses at shorter muscle lengths—that were not measured in this work—thereby enabling improved muscle function over a greater operational range of muscle lengths than NR or implantation of BAM. FE models also clearly indicate that functional improvements over the full operational range of muscle lengths, as well as for progressively larger VML injuries, will require that the regenerative therapeutics utilized produce a correspondingly greater degree of de novo skeletal muscle regeneration to ensure recovery of physiologically significant contractile force. The combination of computational approaches with validated animal models of VML defects/injury provides a novel conceptual framework for accelerating development of more efficacious tissue engineering technologies to meet a wider spectrum of unmet clinical needs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the U.S. Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity under contract numbers W81XWH-14-2-004, W81XWH-15-2-0012, W81XWH-15-C-0084, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant U01AR069393, and the Orthopaedics Department at University of Virginia. Authors would like to thank Dr. Phillip N. Freeman for the schematic representation of the cleft lip repair shown in the Supplemental Material.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Grogan B.F., Hsu J.R., and Skeletal Trauma Research Consortium. Volumetric muscle loss. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 19(Suppl 1), S35, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Passipieri J.A., and Christ G.J. The potential of combination therapeutics for more complete repair of volumetric muscle loss injuries: the role of exogenous growth factors and/or progenitor cells in implantable skeletal muscle tissue engineering technologies. Cells Tissues Organs 202, 202, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tanaka S.A., Mahabir R.C., Jupiter D.C., and Menezes J.M. Updating the epidemiology of cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Plast Reconstr Surg 129, 511e, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Woo A.S. Evidence-based medicine: cleft palate. Plast Reconstr Surg 139, 191e, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mossey P.A., Little J., Munger R.G., Dixon M.J., and Shaw W.C. Cleft lip and palate. Lancet 374, 1773, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ayele T., Zuki A.B.Z., Noorjahan B.M.A., and Noordin M.M. Tissue engineering approach to repair abdominal wall defects using cell-seeded bovine tunica vaginalis in a rabbit model. J Mater Sci Mater Med 21, 1721, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rossi C.A., Flaibani M., Blaauw B., et al. In vivo tissue engineering of functional skeletal muscle by freshly isolated satellite cells embedded in a photopolymerizable hydrogel. FASEB J 25, 2296, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Willett N.J., Li M.T., Uhrig B.A., et al. Attenuated human bone morphogenetic protein-2-mediated bone regeneration in a rat model of composite bone and muscle injury. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 19, 316, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wolf M.T., Daly K.A., Reing J.E., and Badylak S.F. Biologic scaffold composed of skeletal muscle extracellular matrix. Biomaterials 33, 2916, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Corona B.T., Wu X., Ward C.L., McDaniel J.S., Rathbone C.R., and Walters T.J. The promotion of a functional fibrosis in skeletal muscle with volumetric muscle loss injury following the transplantation of muscle-ECM. Biomaterials 34, 3324, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grasman J.M., Do D.M., Page R.L., and Pins G.D. Rapid release of growth factors regenerates force output in volumetric muscle loss injuries. Biomaterials 72, 49, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Christ G.J., Passipieri J.A., Treasure T.E., et al.Skeletal muscle tissue engineering. In: Vishwakarma, A., Sharpe, P., Shi, S., and Ramalingam, M., eds. Chapter 43—Stem Cell Biology and Tissue Engineering in Dental Sciences. Boston: Academic Press, 2015, p. 567. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mase V.J., Jr, Hsu J.R., Wolf S.E.6, et al Clinical application of an acellular biologic scaffold for surgical repair of a large, traumatic quadriceps femoris muscle defect. Orthopedics 33, 511, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Han N., Yabroudi M.A., Stearns-Reider K., et al. Electrodiagnostic evaluation of individuals implanted with extracellular matrix for the treatment of volumetric muscle injury: case series. Phys Ther 96, 540, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sicari B.M., Rubin J.P., Dearth C.L., et al. An acellular biologic scaffold promotes skeletal muscle formation in mice and humans with volumetric muscle loss. Sci Transl Med 6, 234ra58, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sicari B.M., Dearth C.L., and Badylak S.F. Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine approaches to enhance the functional response to skeletal muscle injury. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 297, 51, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Farmand M. Secondary lip correction in unilateral clefts. Facial Plast Surg 18, 187, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Corona B.T., Machingal M.A., Criswell T., et al. Further development of a tissue engineered muscle repair construct in vitro for enhanced functional recovery following implantation in vivo in a murine model of volumetric muscle loss injury. Tissue Eng Part A 18, 1213, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Corona B.T., Ward C.L., Baker H.B., Walters T.J., and Christ G.J. Implantation of in vitro tissue engineered muscle repair constructs and bladder acellular matrices partially restore in vivo skeletal muscle function in a rat model of volumetric muscle loss injury. Tissue Eng Part A 20, 705, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Machingal M.A., Corona B.T., Walters T.J., et al. A tissue-engineered muscle repair construct for functional restoration of an irrecoverable muscle injury in a murine model. Tissue Eng Part A 17, 2291, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Corona B.T., Wenke J.C., and Ward C.L. Pathophysiology of volumetric muscle loss injury. Cells Tissues Organs 202, 180, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aguilar C.A., Greising S.M., Watts A., et al. Multiscale analysis of a regenerative therapy for treatment of volumetric muscle loss injury. Cell Death Discov 4, 33, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Greising S.M., Rivera J.C., Goldman S.M., Watts A., Aguilar C.A., and Corona B.T. Unwavering pathobiology of volumetric muscle loss injury. Sci Rep 7, 13179, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lieber R.L., and Fridén J. Functional and clinical significance of skeletal muscle architecture. Muscle Nerve 23, 1647, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Garg K., Ward C.L., Hurtgen B.J., et al. Volumetric muscle loss: persistent functional deficits beyond frank loss of tissue. J Orthop Res 33, 40, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huijing P.A. Muscle as a collagen fiber reinforced composite: a review of force transmission in muscle and whole limb. J Biomech 32, 329, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Street S.F. Lateral transmission of tension in frog myofibers: a myofibrillar network and transverse cytoskeletal connections are possible transmitters. J Cell Physiol 114, 346, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Burkholder T.J., and Lieber R.L. Sarcomere length operating range of vertebrate muscles during movement. J Exp Biol 204, 1529, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gordon A.M., Huxley A.F., and Julian F.J. The variation in isometric tension with sarcomere length in vertebrate muscle fibres. J Physiol 184, 170, 1966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Quarta M., Cromie Lear M.J., Blonigan J., Paine P., Chacon R., and Rando T.A. Biomechanics show stem cell necessity for effective treatment of volumetric muscle loss using bioengineered constructs. NPJ Regen Med 3, 18, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Blemker S.S., Pinsky P.M., and Delp S.L. A 3D model of muscle reveals the causes of nonuniform strains in the biceps brachii. J Biomech 38, 657, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fiorentino N.M., Rehorn M.R., Chumanov E.S., Thelen D.G., and Blemker S.S. Computational models predict larger muscle tissue strains at faster sprinting speeds. Med Sci Sports Exerc 46, 776, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hernández-Gascón B., Grasa J., Calvo B., and Rodríguez J.F. A 3D electro-mechanical continuum model for simulating skeletal muscle contraction. J Theor Biol 335, 108, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wheatley B.B., Odegard G.M., Kaufman K.R., and Haut Donahue T.L. A validated model of passive skeletal muscle to predict force and intramuscular pressure. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 16, 1011, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Odegard G.M., Donahue T.L., Morrow D.A., and Kaufman K.R. Constitutive modeling of skeletal muscle tissue with an explicit strain-energy function. J Biomech Eng 130, 061017, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Millard R., Jr., andCleft D. Craft: the Evolution of Its Surgery, 1st ed. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company, 1976 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stål P., Eriksson P.O., Eriksson A., and Thornell L.E. Enzyme-histochemical and morphological characteristics of muscle fibre types in the human buccinator and orbicularis oris. Arch Oral Biol 35, 449, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Raposio E., Bado M., Verrina G., and Santi P. Mitochondrial activity of orbicularis oris muscle in unilateral cleft lip patients. Plast Reconstr Surg 102, 968, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Delp M.D., and Duan C. Composition and size of type I, IIA, IID/X, and IIB fibers and citrate synthase activity of rat muscle. J Appl Physiol (1985) 80, 261, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Passipieri J.A., Baker H.B., Siriwardane M., et al. Keratin hydrogel enhances in vivo skeletal muscle function in a rat model of volumetric muscle loss. Tissue Eng Part A 23, 556, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Baker H.B., Passipieri J.A., Siriwardane M., et al. Cell and growth factor-loaded keratin hydrogels for treatment of volumetric muscle loss in a mouse model. Tissue Eng Part A 23, 572, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chen X.K., and Walters T.J. Muscle-derived decellularised extracellular matrix improves functional recovery in a rat latissimus dorsi muscle defect model. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 66, 1750, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Powell P.L., Roy R.R., Kanim P., Bello M.A., and Edgerton V.R. Predictability of skeletal muscle tension from architectural determinations in guinea pig hindlimbs. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 57, 1715, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mathewson M.A., Chapman M.A., Hentzen E.R., Fridén J., and Lieber R.L. Anatomical, architectural, and biochemical diversity of the murine forelimb muscles. J Anat 221, 443, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chen X.K., Rathbone C.R., and Walters T.J. Treatment of tourniquet-induced ischemia reperfusion injury with muscle progenitor cells. J Surg Res 170, e65, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Anderson A.E., Ellis B.J., and Weiss J.A. Verification, validation and sensitivity studies in computational biomechanics. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin 10, 171, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Weiss J.A., Maker B.N., and Govindjee S. Finite element implementation of incompressible, transversely isotropic hyperelasticity. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 135, 107, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wallace H., Hu X., Passipieri J.A., Remer D., Christ G.J., and Blemker S.S. Biaxial testing of the passive properties of native and regenerated skeletal muscle tissue. In: The 41st Annual Meeting of the American Society of Biomechanics. Boulder, CO, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 49. Morrow D.A., Haut Donahue T.L., Odegard G.M., and Kaufman K.R. Transversely isotropic tensile material properties of skeletal muscle tissue. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 3, 124, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Inouye J.M., Handsfield G.G., and Blemker S.S. Muscle architecture analysis using computational fluid dynamics. In:39th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Biomechanics. Columbus, OH, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zajac F.E. Muscle and tendon: properties, models, scaling, and application to biomechanics and motor control. Crit Rev Biomed Eng 17, 359, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Arnold E.M., and Delp S.L. Fibre operating lengths of human lower limb muscles during walking. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 366, 1530, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Murray W.M., Buchanan T.S., and Delp S.L. The isometric functional capacity of muscles that cross the elbow. J Biomech 33, 943, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Inouye J.M., and Blemker S.S. Advances in hyperelastic finite element modeling of biological tissues: explicit strain energy function specification. In:39th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Biomechanics. Columbus, OH, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 55. Barron D.J., Etherington P.J., Winlove C.P., Jarvis J.C., Salmons S., and Pepper J.R. Combination of preconditioning and delayed flap elevation: evidence for improved perfusion and oxygenation of the latissimus dorsi muscle for cardiomyoplasty. Ann Thorac Surg 71, 852, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]