Abstract

Study Objectives:

(1) Review the prevalence and comorbidity of sleep disorders among United States military personnel and veterans. (2) Describe the status of sleep care services at Veterans Health Administration (VHA) facilities. (3) Characterize the demand for sleep care among veterans and the availability of sleep care across the VHA. (4) Describe the VA TeleSleep Program that was developed to address this demand.

Methods:

PubMed and Medline databases (National Center for Biotechnology Information, United States National Library of Medicine) were searched for terms related to sleep disorders and sleep care in United States military and veteran populations. Information related to the status of sleep care services at VHA facilities was provided by clinical staff members at each location. Additional data were obtained from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse.

Results:

Among United States military personnel, medical encounters for insomnia increased 372% between 2005–2014; encounters for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) increased 517% during the same period. The age-adjusted prevalence of sleep disorder diagnoses among veterans increased nearly 6-fold between 2000–2010; the prevalence of OSA more than doubled in this population from 2005–2014.

Conclusions:

Most VA sleep programs are understaffed for their workload and have lengthy wait times for appointments. The VA Office of Rural Health determined that the dilemma of limited VHA sleep health care availability and accessibility might be solved, at least in part, by implementing a comprehensive telehealth program in VA medical facilities. The VA TeleSleep Program is an expansion of telemedicine services to address this need, especially for veterans in rural or remote regions.

Citation:

Sarmiento KF, Folmer RL, Stepnowsky CJ, Whooley MA, Boudreau EA, Kuna ST, Atwood CW, Smith CJ, Yarbrough WC. National expansion of sleep telemedicine for veterans: the telesleep program. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(9):1355–1364.

Keywords: telemedicine, telehealth, rural, Veterans Affairs, sleep, Veterans Health Administration

INTRODUCTION

In 2006, the United States National Academy of Sciences published a report titled Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: An Unmet Public Health Problem.1 The report stated that 50 to 70 million Americans had a chronic disorder of sleep and wakefulness, a population that “greatly outstrips” our health care systems’ ability to provide adequate sleep services for these patients. Since 2006, the number of people who experience sleep disorders has increased and United States health care systems remain overwhelmed by the demand for sleep care services.2,3 The prevalence of sleep disorders is particularly high among United States military personnel and veterans and continues to increase in these populations for a variety of reasons. In the following sections, we provide an overview of the types and magnitude of sleep disorders experienced by these groups. The purpose of the overview is to inform readers about, (1) particular sleep disorders and comorbidities experienced by military personnel and veterans; and (2) why the demand for VA sleep services is substantial and continues to increase.

SLEEP DISORDERS AMONG MILITARY PERSONNEL

Only 25% to 35% of United States Service Members routinely attain the recommended daily amount of sleep for adults of 7–8 hours.4,5 Disrupted sleep patterns are not surprising during deployment because of inhospitable or threatening conditions and limited opportunities for sleep, given high operational demands. However, sleep disorders often persist after deployments have ended due to “conditioned hyperarousal” or continued hypervigilance.6

In an ambitious study, Caldwell et al7 analyzed data collected from the entire United States military population (mean = 1,381,406 individuals per year) between 2005-2014. Analysis of International Classification of Disease (ICD-9) codes revealed that medical encounters for insomnia increased from 16 per 1,000 individuals in 2005, to 75 per 1,000 individuals in 2014 – an increase of 372%. Encounters for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) increased from 44 per 1000 individuals in 2005, to 273 per 1,000 individuals in 2014—an increase of 517%. Rates of insomnia and OSA increased linearly over time for every subpopulation except those less than 20 years of age. Caldwell et al7 speculated that the increase in prevalence of sleep disorders among military personnel might be due to comorbid medical conditions such as traumatic brain injury (TBI), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), chronic pain and depression experienced by service members who were deployed to the Middle East during recent conflicts.

Klingaman et al8 analyzed data from 21,499 United States soldiers who completed the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Service Members. The presence of insomnia in this population was determined by Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition criteria using the Brief Insomnia Questionnaire. Insomnia was present in 22.8% of the sample, which is nearly double the rate reported for the general population.2 Klingaman et al8 stated that insomnia among soldiers had global, negative associations with their mental health, social functioning, support, morale, work performance, and Army career intentions.

The studies above provide evidence that OSA and insomnia are more prevalent among military personnel compared to civilian populations. Therefore, it is not surprising that many veterans also experience difficulties sleeping. Caldwell et al7 concluded, “In response to this epidemic-like increase in sleep disorders, their prevention, identification and aggressive treatment should become a health-care priority.”

SLEEP DISORDERS AMONG VETERANS

Alexander et al9 hypothesized that sleep disruption is more common among veterans than in the general population. To assess this, the authors analyzed electronic medical records of > 9.7 million veterans who received care in Veterans Health Administration (VHA) facilities between FY2000–FY2010. Sleep disorders were identified using diagnostic codes specified by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine.10 Results indicated that the age-adjusted prevalence of sleep disorder diagnoses increased nearly 6-fold over the course of the study, from less than 1% in 2000, to nearly 6% in 2010. However, the age-adjusted prevalence of sleep apnea was only 3% in 2010, and the age-adjusted prevalence of insomnia was only 1.5% in 2010, which are both well below estimates for the general population in other studies.2,3 It is likely that Alexander et al’s9 use of diagnostic codes to ascertain the prevalence of sleep disorders among veterans who received care in VHA facilities resulted in underestimation of these conditions—a possibility the authors mention in their article. It is also probable that different methods used by Ford et al2 and Franklin and Lindberg3 (compared to Alexander et al9) to define and identify specific sleep disorders contributed to the disparate results reported by these studies. Additional explanations for underestimates of sleep disorders among veterans include a lack of consistent documentation in medical records by primary care providers11 and under-reporting of sleep problems by patients to providers.12 Martin13 suggested that the number of veterans with a documented diagnosis of a sleep disorder likely represents a small fraction of the total number of veterans who experience these conditions.

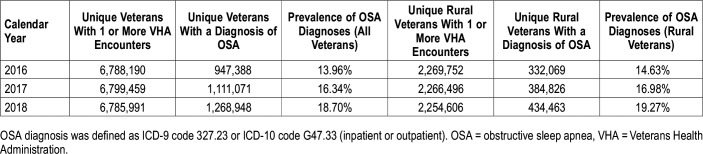

To estimate the prevalence of sleep apnea among United States male military veterans, Jackson et al14 analyzed data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health collected between 2005–2014. In their sample of 20,631 veterans, the prevalence of sleep apnea increased from 3.7% to 8.1% during the study period. The prevalence of sleep apnea was higher among veterans in the 50–64-year age range compared to other age groups. Also, sleep apnea was more common among veterans who experienced serious psychological distress during the previous year (11.4% prevalence of apnea) compared to veterans who did not report serious psychological distress during the previous year (5.4% prevalence of apnea). According to the VA Corporate Data Warehouse—the repository for VHA clinical data—1,268,948 enrolled veterans had a diagnosis of OSA in 2018, which represents a prevalence of 18.7% within the VA patient population (Table 1). Data in Table 1 show that the prevalence of OSA diagnoses among veterans increased by 2.4% each year from 2016 to 2018. Reasons for these increases include the following: (1) While the numbers of unique veterans seen in all VHA facilities remained fairly consistent during this time period, the numbers of appointments in VA sleep medicine clinics increased each year (Figure 1); (2) the use of of home sleep apnea tests (HSAT) at many VA facilities increased during this time period and continues to increase nationally. These two factors reflect veterans’ increased access to and utilization of VA sleep care, and also increased the likelihood of OSA diagnosis. Of the 1,268,948 veterans currently diagnosed with OSA, 434,463 (34%) live in rural or remote regions of the United States. The prevalence of OSA diagnoses among rural veterans in 2018 was 19.3%, which is slightly higher than the value for all veterans who had an OSA diagnosis that year (18.7%). Because a high percentage of veterans exhibit risk factors for OSA, it is probable that these diagnostic data underestimate the numbers of VA patients who have the condition. Diagnoses of OSA among veterans are likely to increase during the next few years if their access to VA sleep care continues to improve and utilization of HSAT increases in VHA facilities.

Table 1.

Numbers of veterans diagnosed with OSA in the VHA (1/1/2016–12/31/2018).

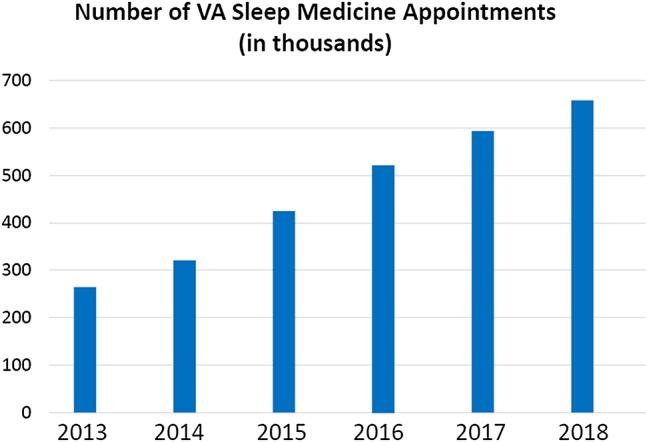

Figure 1. Numbers of appointments for VA sleep care during years 2013–2018.

VA = Veterans Affairs.

Colvonen et al15 investigated the relationship between OSA and PTSD in a group of veterans who served in Iraq or Afghanistan. Of 159 veterans assessed at a VA outpatient PTSD clinic, 69% were identified as high-risk for OSA according to Berlin Questionnaire criteria. Furthermore, greater PTSD severity (as determined by the PTSD Checklist questionnaire) increased the risk of screening positive for OSA, after controlling for risk factors such as patient age, positive smoking status, and use of CNS depressants. The mean age of veterans in this study was 33.4 years, and their mean body mass index was 29.1 kg/m2. Because these values are lower than those of older and overweight veterans typically deemed as high-risk for OSA, Colvonen et al15 suggested that OSA might be under-diagnosed in younger veterans with PTSD. Unfortunately, diagnostic sleep testing results were not reported in this study, so the accuracy of the Berlin Questionnaire in predicting a diagnosis of OSA could not be assessed. On a positive note, Orr et al16 demonstrated that veterans with PTSD and OSA who were treated using positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy exhibited significant reductions in PTSD severity during the 6-month study which used a primary outcome measure of the PTSD checklist (PCL). Veterans in this study who used PAP devices for treatment of OSA also showed improvement in depression (Patient Health Quesionnaire-9), functional outcomes (Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire, short form), sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index), and daytime sleepiness (Epworth Sleepiness Scale). Troxel et al6 and others concluded that the association between sleep disorders and psychiatric disorders (such as depression and PTSD) is bidirectional: sleep difficulties are often symptoms of psychiatric disorders, and sleep problems can increase the likelihood/severity of some psychological conditions. The relationship between sleep disorders and comorbid conditions was also investigated in a study involving 130 veterans who were deployed in Iraq or Afghanistan.17 As the authors predicted, sleep quality (assessed by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index) mediated the effect of TBI history on current suicidal ideation. In this study, the veteran’s history of TBI was associated with worse sleep quality which was, in turn, associated with increased suicidal ideation.

Obviously, sleep disorders are a major problem for many veterans and are therefore a major concern of the VHA. It has been suggested that identification and treatment of sleep disorders in veterans may result in lower health care utilization and improved quality of life.9 Martin13 agreed that improving care for veterans with sleep disorders, particularly sleep apnea and insomnia, has the potential to reduce the impact of comorbid conditions, lower health care costs and improve quality of life for these patients. However, given that a substantial proportion of veterans with sleep disorders likely remain undiagnosed, Martin13 lamented that meeting the VA’s current and future demand for diagnostic testing and treatment presents a daunting task.

VA SLEEP SERVICES

To provide information related to the status of sleep services available in VHA to meet this demand, Sarmiento et al18 reported results of a questionnaire distributed to all VA Sleep programs. One-hundred eleven of 151 VA Medical Centers with sleep services responded (74% response rate). Of those programs that responded, 31 (28%) sites were classified (using VA terminology) as complex sleep programs, 51 (46%) were intermediate sleep programs, 10 sites (9%) were standard sleep programs, and 19 (17%) did not offer any formal sleep services at all. Complex programs required both in-laboratory and home testing capabilities, dedicated sleep staff, sleep and continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) clinics (staffed by sleep physicians or advanced practice providers [APPs], and respiratory therapists or sleep technologists, respectively), and cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia; intermediate programs offered either home testing or in-laboratory polysomnography, had dedicated sleep staff, offered sleep and/or CPAP clinics, and may or may not have had cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia services at their facility; standard programs had limited personnel and infrastructure to manage sleep disorders, offering CPAP clinics but no diagnostic testing, physician- or APP-level clinics. Responses to the questionnaire reflected considerable variability across sleep medicine programs in the VA. In FY2013, nearly 40% of VA Medical Centers (VAMCs) offered very limited or no sleep services at all. The percentage of VAMCs offering sleep care increased to 78% in in FY2015 and to 93% in FY2018.

A follow-up questionnaire was sent by Sarmiento and colleagues to VA sleep programs two years after the initial survey. Of 127 sites that completed the inventory (85% response rate), 53 (42%) were complex, 53 (42%) were intermediate, and 13 (10%) were standard. Seven sites (5%) did not provide enough information to determine their sleep program type, six (5%) did not have organized sleep programs, and two sites indicated they were satellite sites of larger, neighboring VAMCs.

GROWING DEMAND FOR VA SLEEP CARE

Between 2013–2018, use of VA sleep care services increased an average of 16% per year, while the average wait time for an appointment in a VHA sleep clinic remains greater than 40 days (VA Corporate Data Warehouse). Figure 1 illustrates the numbers of appointments for sleep care in VA facilities, which exhibited significant increases between 2013–2018 and exceeded 650,000 in 2018. Given these statistics, it is not surprising that most VA sleep programs are understaffed for their given workload, with many reporting staff burnout and growing wait times for appointments.18 Reasons for increases in the number of veterans requiring sleep care include the following: aging of the population; relatively high rates of comorbid conditions such as obesity, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic pain, depression and PTSD; and increased utilization of VA health care, especially by younger and rural veterans. Also, poor sleep habits that developed during military service sometimes continue for veterans during civilian life.6

TELEMEDICINE AND TELEHEALTH SERVICES FOR SLEEP

To improve access to quality sleep care for veterans, novel approaches and innovations are necessary. Development and implementation of telemedicine and telehealth applications for sleep care is a viable and creative way to address this vital health care need. VA Telehealth Services uses health informatics, disease management and telehealth technologies to target care and case management to improve veterans’ access to care. Telehealth changes the location where health care services are routinely provided and includes both synchronous and asynchronous implementation strategies. Numerous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of telehealth strategies to deliver various sleep care services to patients.19–25

Watson et al26 writing on behalf of the Board of Directors of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, agreed with the Institute of Medicine report1 that the increasing need for sleep services in the United States still greatly outstrips our current health care systems’ ability to provide adequate sleep care for patients. Consequently, Watson et al concluded that “bringing telemedicine into the sleep clinic is the natural next step, with numerous studies suggesting benefits to all parties involved.” The VHA has been in the forefront of developing a variety of telemedicine applications for its ever-growing and widely-dispersed patient population. VA Telehealth includes programs to enhance many services such as TeleMental Health, TeleIntensive Care, TeleRehabilitation, TeleCardiology, TelePrimary Care, TeleOccupational Therapy, TeleDermatology, and more. Within VHA, OSA and insomnia are the primary sleep disorders that have been managed using VA telehealth technologies, although these methods could also be used to deliver a broader spectrum of sleep services to veterans.

While applications of telemedicine for sleep disorders have been the subject of numerous studies, those conducted within the private sector are sometimes limited by the constraints of reimbursable services. Studies conducted within closed health care systems such as the VA or Kaiser Permanente have been able to provide data on the value of telehealth components for sleep disorder evaluation and treatment, and how these components are delivered. For example, Baig et al27 reported that implementation of an electronic consultation program at the VA Medical Center in Milwaukee helped to reduce the time between veteran referral to the sleep program and PAP prescription from an average of 60 days to 7 days. This improvement occurred over a period of 5 years, despite an increase in the volume of sleep consults and sleep studies performed during that time. The Houston VA Sleep Disorder Center has used a combination of home testing, video teleconferencing, store-and-forward technology and telephone consultation for several years to improve the efficiency of sleep service delivery to veterans in their health care system.28 Kuna et al29 reported that adherence to PAP treatment improved significantly when adults with moderate to severe OSA were given computer access to information related to their use of the treatment, which was provided by the device manufacturer. In this study, the participant’s wireless data on the manufacturer’s server were transmitted daily to a participant-facing web site that displayed individual hours of usage. Fields et al20 reported that telemedicine-based management of OSA was successful and well-received by a group of 60 veterans at the VA Philadelphia Medical Center. In this randomized controlled trial, veterans were either seen by video conferencing or in-person; either mailed a home sleep study or instructed on how to use the equipment in person; and received follow-up care either by wireless monitoring with a video conference clinic or in-person. There was no significant difference in adherence to PAP therapy between the telehealth and in-person groups, and patient satisfaction with the telemedicine pathway was high. Previously, Berry et al30 and Kuna et al31 demonstrated that HSAT via portable monitoring was not inferior to polysomnography for CPAP adherence and functional outcomes in veteran patients.

Not only does telehealth technology improve access to sleep services for veterans, it can also improve the efficiency of health care delivery in terms of time and costs. Russo et al32 analyzed the savings associated with a telemedicine program conducted at the VA medical center in White River Junction, Vermont between 2005–2013. This program was associated with average travel savings of 145 miles and 142 minutes per visit. Travel reimbursement payments to veterans utilizing this telehealth program were reduced, while access to health care services was streamlined and made more convenient for patients.

The current dilemma of limited sleep health care availability and accessibility across the VHA might be solved, at least in part, by implementing a comprehensive TeleSleep program in VA medical facilities nationwide.

A NATIONAL TELESLEEP PROGRAM FOR VETERANS

In response to unprecedented and often unmet demand for sleep services by veterans, the VA Office of Rural Health funded an enterprise-wide initiative to develop and implement a national TeleSleep program for the VHA. The goal of this program is to improve the health and well-being of rural veterans by increasing their access to sleep care and services. Of the of 9.1 million veterans currently enrolled in the VHA health care system, 2.8 million veterans live in rural or remote regions of the country.33 Compared to urban areas in the United States, rural communities tend to have higher poverty rates, more elderly residents, residents with poorer health, and fewer health care resources. Consistent with these trends, rural veterans are significantly older than their urban counterparts (56% of rural veterans are over the age of 65 years); and 58% of rural veterans are enrolled in the VA health care system—a significantly higher percentage compared to the 37% percent enrollment rate of urban veterans.33 This greater reliance on VHA health care by rural veterans is a consequence of economic hardship and limited options in many of their communities. As shown in Table 1, a significant percentage of veterans (34%) receiving sleep apnea care at VA facilities live in rural or remote regions.

While the immediate focus of the TeleSleep enterprise-wide initiative is to improve accessibility to and quality of sleep care for veterans in rural areas, implementation of the program’s telehealth elements will benefit patients and clinicians throughout VA by streamlining procedures, improving communication and enhancing diagnostic and treatment capabilities. This program is also likely to benefit other health care systems by generating data that inform policies related to reimbursement and covered services for sleep. Specific goals of the VA TeleSleep Program include: (1) improved accessibility and quality of sleep care, especially for veterans in rural areas; (2) standardization of medical coding used to track sleep services; (3) standardization of patient-generated data using validated questionnaires across participating sites; (4) creation of specific measures enabling longitudinal evaluation of processes employed in the evaluation of patients with sleep disorders; and (5) development of a toolkit available to all VA Medical Centers, enabling initiation or expansion of sleep telemedicine.

The TeleSleep Program is being developed in accordance with recommendations made by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine's Taskforce on Sleep Telemedicine34 using technologies and strategies available through VA Telehealth Services. These services can include both synchronous and asynchronous delivery of care. Synchronous telemedicine involves the use of video teleconferencing (from VA-to-VA facility, or from a VA-facility to a patient at home), Home Telehealth monitoring, and telephone clinics. Asynchronous telemedicine uses Store-and-Forward technologies such as remote data monitoring (eg, review of wireless PAP efficacy and compliance data), and HSAT.

“Hub and Spoke Model” for Program Implementation

The TeleSleep Program utilizes a “hub and spoke” model for the deployment of telemedicine-based services to rural veterans. The “spokes” are community-based outpatient clinics and VA medical centers (VAMCs) with limited sleep services that serve a majority of rural veterans. The “hubs” are established VA Sleep Medicine Programs with the required infrastructure and expertise to provide spokes with reasonably rapid access to sleep services through HSAT, Clinical Video Teleconferencing, electronic consults, Secure Messaging (SM), a web-based care pathway called REVAMP (Remote Veteran Apnea Management Platform), and wireless PAP therapy monitoring.

Program Locations

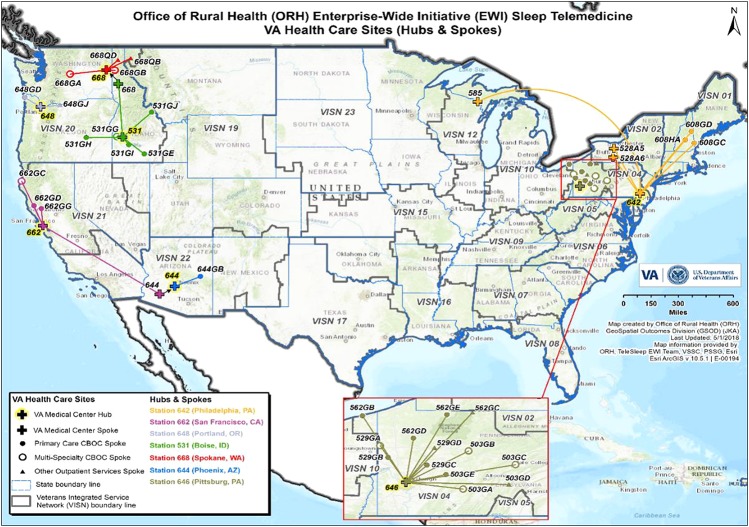

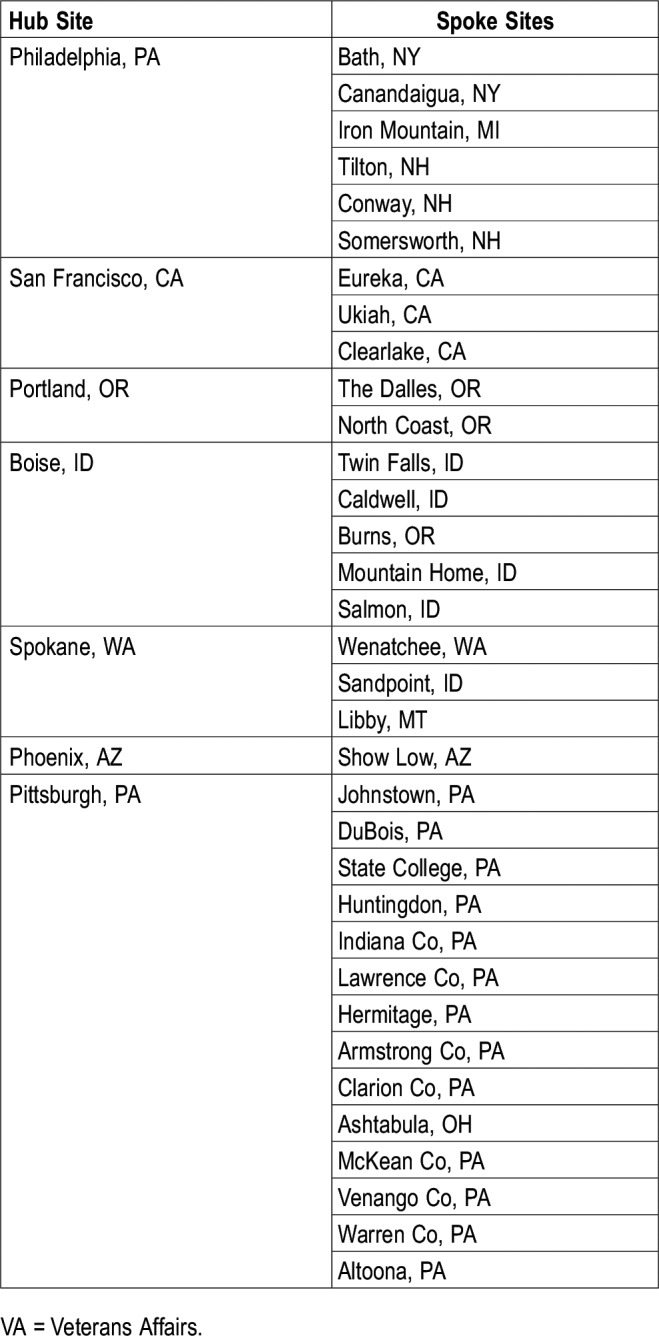

The TeleSleep Program officially began in March 2017 in four Veteran Integrated Service Networks (VISNs): VISN 4 (VA Healthcare); VISN 20 (VA Northwest Health Network), VISN 21 (Sierra Pacific Network); and VISN 22 (Desert Pacific Healthcare Network). Locations of the 7 hub and 34 spoke sites currently participating in the program are listed in Table 2. A map in Figure 2 shows the locations of these sites.

Table 2.

VA facilities participating in the TeleSleep program.

Figure 2. Map showing hub and spoke site locations for the VA TeleSleep enterprise-wide initiative.

VA = Veterans Affairs.

Patient Population

The target patient population for the TeleSleep program includes veterans at designated rural spokes. However, the VA Sleep program office will monitor sleep care provided not only at spoke sites, but also the care provided at hub sites to assess how expansion of services in this hub-and-spoke model impacts access to sleep care for all veterans at the supporting facility. Personnel at each hub tailor delivery of sleep care, including their choice of telemedicine services, based on the characteristics and culture of spoke communities, as well as resources available at the hubs. Prior to initiation of services, an agreement covering credentialing, privileging, and scope of services is established between hub and spoke sites. Veterans may either be new referrals to a hub site, or existing patients within a VA sleep program. The number of “rural” veterans in the program is determined using rurality scores (based on each veteran’s home address) within the VA Corporate Data Warehouse.

TeleSleep Program Elements

TeleSleep focuses on establishing both synchronous and asynchronous telehealth services, but also emphasizes the use of other modalities that reduce the need for in-person visits. These modalities include telephone visits, electronic consultations, and encrypted email messaging.

Synchronous telehealth encompasses all video teleconferencing between patients and care providers, regardless of patient or provider location. In this article, sleep care providers can refer to physicians, psychologists, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, nurses, and respiratory therapists. With the adoption of the “Anywhere-to-Anywhere” policy in 2017, VA providers can now deliver care to patients across state lines, at VA and non-VA facilities, and even into patients’ homes. Video teleconferencing at VA facilities (medical centers and community-based outpatient clinics) is used for initial consultation and follow-up visits. Telehealth technicians assist with these visits and are the “hands of the provider” on the patient side. Assistive devices enable auscultation or examination of the upper airway, when needed. In-home video teleconferencing (or video-on-demand), is a secure, encrypted means of video chatting with patients anywhere their smart device has reception. This technology also enables bringing other providers or family members into the virtual medical room for warm handoffs or family meetings. For sleep-specific visits, in-home Video-on-Demand enables viewing of bedroom environments (presence of a television, windows, lighting, etc.), positioning of PAP or other treatment devices within the bedroom, and other home conditions relevant to improving patients’ sleep. The VA uses an internal system for patient data communication, but PAP data are provided by device manufacturers.

Asynchronous telehealth includes HSAT involving VAMCs and their associated community-based outpatient clinics. This store-and-forward modality allows nonsleep services such as cardiology and mental health to administer sleep studies and upload the raw data to a shared server, after which sleep specialists score and interpret data from these uploads. Interfacility consults for store-and-forward HSAT establishes a model of shared resources, both equipment and personnel, to improve access to sleep diagnostic care at sites that might otherwise be unable to hire a sleep physician to interpret sleep studies. Another asynchronous telehealth modality is remote monitoring of PAP data from a patient’s home. Data provided by PAP device manufacturers can be reviewed monthly, which provides documentation of adherence to and efficacy of therapy. Also, home-based telehealth visits allow both patients and providers to view PAP machine screens so they can talk through setting changes for comfort features such as humidification adjustment.

Provision of care through a VA web-application called REVAMP is another type of asynchronous telemedicine used in the TeleSleep Program. Developed through the VA Center of Innovation, REVAMP enables comprehensive care of a patient referred for sleep apnea evaluation. This application, which resides within the VA cloud environment, requires two-factor authentication for access by both patients and providers. Two-factor authentication is required by VA for all secure communications. Within REVAMP, patients complete initial standardized questionnaires to provide information about their sleep habits, quality, and concerns. Responses to these questionnaires (which are reviewed by a VA sleep provider) and data from the patients’ electronic medical record are incorporated into an initial consultation (e-consultation, telephone visit, or video teleconferencing visit). Using patient-reported data, collected without an in-person visit, to triage patients to sleep testing is highly novel and unprecedented in sleep medicine. This innovation builds on the concept of traditional e-consultation by adding patient-reported data to the initial evaluation, increasing the ability of sleep providers to determine the most appropriate plan of care. The patient is then scheduled for diagnostic sleep testing if they are a new consultation. When appropriate, HSAT devices are mailed to veterans along with instructional materials on how to perform the sleep study themselves at home. The patient will drop off or mail the HSAT device back to the clinic in a prestamped and addressed envelope. Based on the authors’ experience, more than 75% of veterans tested using HSAT devices are likely to have clinically significant apnea. Patients prescribed PAP therapy will have their devices registered within REVAMP, which allows data from device manufacturers to be displayed to both veterans and clinicians. Veterans participating in REVAMP are able to access their PAP data, communicate with their sleep providers via email, and self-manage their PAP treatment using video tutorials and support materials available on the REVAMP platform. Follow-up questionnaires (such as the Insomnia Severity Index, the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and the Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire) are completed periodically to assess changes in symptoms and sleep quality.

Electronic consults (e-consults) are used at four of TeleSleep’s hub sites (Portland, San Francisco, Boise, and Pittsburgh) to perform medical record reviews for new referrals, enabling medical decision making for diagnostic sleep testing that does not require the patient to first be seen in person by a care provider. The goal of this strategy is to reduce veterans’ wait times for diagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders. E-consults are designed to capture health factors measures or data elements determined to be important to sleep providers (eg, patients’ apnea hypopnea index); to track information critical to decision-making about the next step in care that is needed; and to gather information about the reason(s) for consultation, the patient’s risk of having a sleep disorder (based on referring provider input), patient interest in telemedicine services, and access to the internet. The e-consult modules for sleep care are part of a national toolkit developed by the TeleSleep Program and available to all VA Medical Centers.

A potential barrier to transmission of PAP data, participation in REVAMP, and utilization of in-home video-on-demand in this rural-veteran-focused program is cell-tower coverage and wi-fi availability. Without sufficient coverage, the ability to use these technologies is limited. However, rural veterans with no cell tower coverage in VISN 20 have successfully participated in wireless monitoring by periodically bringing their PAP devices into local towns that do have coverage (transmission of batched data is automatic, so connection to wi-fi is not required). To fully participate in the REVAMP application, veterans need internet access by computer, tablet or smartphone. If rural veterans do not have access to the internet or cannot participate in REVAMP, they will be evaluated through telephone clinics, clinical video teleconferencing, or in-person.

Program Evaluation

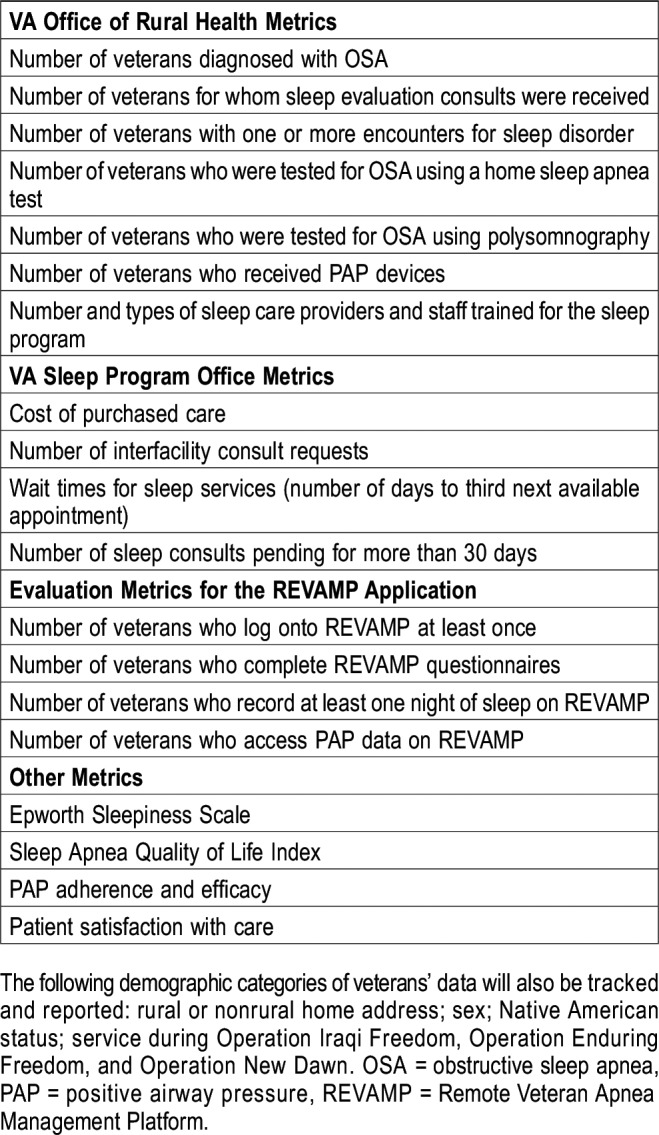

The Measurement Science Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) at the San Francisco VA Health Care System will conduct formative and summative evaluations of the TeleSleep program. The QUERI will determine whether, how, and why the program is or is not working by using rigorous methodology to collect both process and clinical outcome measures. These in-depth evaluations will be conducted using the REAIM framework (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance), a well-established model for guiding and evaluating the implementation and impact of health care programs.35 “Implementation” refers to the extent to which a program is delivered as intended. The Measurement Science QUERI provided input during the design of the TeleSleep program so that key metrics are included in the workflow and are systematically collected throughout the implementation process. QUERI investigators will conduct detailed qualitative analyses that include interviewing key (provider-, patient-, and system-level) informants at all 4 participating VISNs (4, 20, 21 and 22) to determine the intended and unintended consequences of TeleSleep program implementation. This information will be used to modify implementation strategies as needed. Finally, QUERI will conduct quantitative evaluations of the clinical impact of the TeleSleep program at each of the participating VA facilities. Program evaluation measures will be collected under three domains: (1) VA Office of Rural Health; (2) VA Sleep Program Office; and (3) REVAMP implementation. Core Office of Rural Health metrics include numbers of unique patients, numbers of patient encounters, and numbers of rural veterans served. Other important outcome metrics include patient satisfaction, care experience, acceptability, accessibility, comprehension, ease of use, and continuity of care. The following demographic categories of veterans’ data will also be tracked and reported, as required by the VA Office of Rural Health: sex; Native American status; service during Operation Iraqi Freedom, Operation Enduring Freedom, and Operation New Dawn. Table 3 contains a list of specific evaluation measures that will be collected, analyzed and reported for the TeleSleep Program.

Table 3.

Evaluation metrics for the TeleSleep program.

Future Directions / Program Sustainability

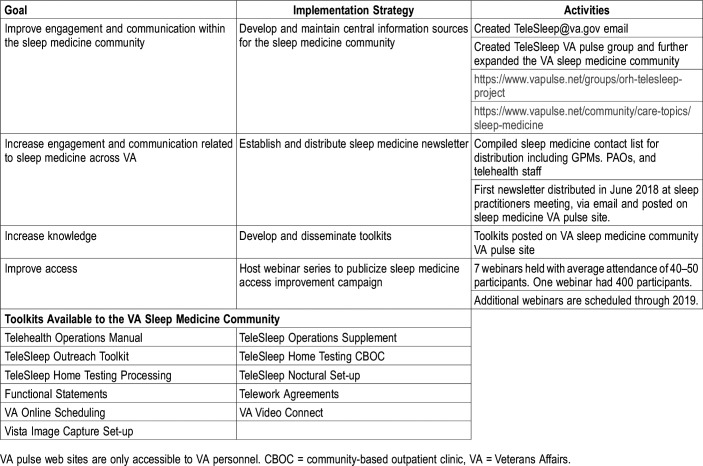

By establishing the infrastructure to capture patient-generated data and to track services that are provided by each provider type (physician, nurse practitioner, physician assistant, respiratory therapist, and sleep technologist), the TeleSleep program has created a framework through which quality improvement/assurance, and research questions related to sleep care can be addressed. The program also aligns with VHA’s recent modernization of its Telehealth Services by providing care across facilities and state lines, and by streamlining the credentialing and privileging processes. These innovations enable the evaluation of VA’s shared resource (personnel and equipment) models. The TeleSleep program also facilitates the growth of a community of sleep medicine providers who are united by common standards and tools that allow them to provide the highest quality care for veterans. Expansion of participating sites within the TeleSleep Program is limited by current funding restraints and by mandates that require spokes to have greater than 50% rurality scores for enrolled veterans. However, partnerships between VAMCs are anticipated to increase as the models outlined by the TeleSleep program are replicated and implemented throughout the VHA. Table 4 summarizes some of the strategies that have been used to promote the TeleSleep Program within the VA and to increase utilization of its various telehealth elements. These activities include: development and maintenance of informational sites on the VA intranet; establishment and distribution of a Sleep Medicine Newsletter to VA care providers and administrators; development of a webinar series to promote utilization of sleep telehealth resources; REVAMP training seminars; development and dissemination of TeleSleep toolkits on a variety of topics.

Table 4.

Strategies, activities and toolkits to promote TeleSleep within VA.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

The VHA has a finite number of sleep care providers and faces sky-rocketing growth in veterans’ need for sleep care. This new, comprehensive TeleSleep program provides strategies and methods that will improve access to, quality and cost-efficiency of sleep care for all veterans. The program leverages innovative telehealth technologies and encourages self-management through patient-initiated interactions that empower veterans by providing them with the information and resources necessary to manage their sleep disorders. The goal of the TeleSleep program is to establish infrastructure within VA to facilitate the delivery of various sleep services via telehealth. This program began with a focus on OSA, but has expanded recently at some sites to include insomnia assessment and treatment. In the future, this framework will be used to deliver a broader spectrum of VA sleep services. Implementation of this program throughout the VA health care system will benefit veterans, care providers and our society in general by improving the quality of life for patients while reducing costs and other barriers associated with sleep medicine services.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government. All authors have seen and approved the manuscript. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a VA Office of Rural Health enterprise-wide initiative, and by the VA Office of Connected Care. The authors thank Justin Ahern and the GeoSpatial Outcomes Division of the Veterans Rural Health Resource Center for generating the map in Figure 2.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CPAP

continuous positive airway pressure

- FY

fiscal year

- HSAT

home sleep apnea test

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnea

- PAP

positive airway pressure

- PCL

PTSD Checklist

- PTSD

posttraumatic stress disorder

- QUERI

Quality Enhancement Research Initiative

- REVAMP

Remote Veteran Apnea Management Platform

- TBI

traumatic brain injury

- VA

Veterans Affairs

- VAMC

VA Medical Center

- VHA

Veterans Health Administration

- VISN

Veteran Integrated Service Network

REFERENCES

- 1.Colten HR, Altevogt BM. Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: An Unmet Public Health Problem. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford ES, Cunningham TJ, Giles WH, Croft JB. Trends in insomnia and excessive daytime sleepiness among U.S. adults from 2002 to 2012. Sleep Med. 2015;16(3):372–378. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franklin KA, Lindberg E. Obstructive sleep apnea is a common disorder in the population-a review on the epidemiology of sleep apnea. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7(8):1311–1322. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.06.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luxton DD, Greenburg D, Ryan J, Niven A, Wheeler G, Mysliwiec V. Prevalence and impact of short sleep duration in redeployed OIF Soldiers. Sleep. 2011;34(9):1189–1195. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mysliwiec V, Gill J, Lee H, et al. Sleep disorders in US military personnel: a high rate comorbid insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2013;144(2):549–557. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Troxel WM, Shih RA, Pedersen E, et al. Sleep in the Military: Promoting Healthy Sleep Among U.S. Servicemembers. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caldwell JA, Knapik JJ, Lieberman HR. Trends and factors associated with insomnia and sleep apnea in all United States military service members from 2005 to 2014. J Sleep Res. 2017;26(5):665–670. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klingaman EA, Brownlow JA, Boland EM, Mosti C, Gehrman PR. Prevalence, predictors and correlates of insomnia in US army soldiers. J Sleep Res. 2018;27(3):e12612. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexander M, Ray MA, Hébert JR, et al. The National Veteran Sleep Disorder Study: descriptive epidemiology and secular trends, 2000-2010. Sleep. 2016;39(7):1399–1410. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thorpy MJ. Classification of sleep disorders. Neurotherapeutics. 2012;9(4):687–701. doi: 10.1007/s13311-012-0145-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ulmer CS, Bosworth HB, Beckham JC, et al. Veterans Affairs primary care provider perceptions of insomnia treatment. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(8):991–999. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shepardson RL, Funderburk JS, Pigeon WR, Maisto SA. Insomnia treatment experience and preferences among veterans affairs primary care patients. Mil. Med. 2014;179(10):1072–1076. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin JL. What to do about the growing number of veterans with diagnosed sleep disorders. Sleep. 2016;39(7):1331–1332. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson M, Becerra BJ, Marmolejo C, Avina RM, Henley N, Becerra MB. Prevalence and correlates of sleep apnea among US male veterans, 2005-2014. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:E47. doi: 10.5888/pcd14.160365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colvonen PJ, Masino T, Drummond SP, Myers US, Angkaw AC, Norman SB. Obstructive sleep apnea and posttraumatic stress disorder among OEF/OIF/OND veterans. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11(5):513–518. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orr JE, Smales C, Alexander TH, et al. Treatment of OSA with CPAP is associated with improvement in PTSD symptoms among veterans. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(1):57–63. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeBeer BB, Kimbrel NA, Mendoza C, et al. Traumatic brain injury, sleep quality, and suicidal ideation in Iraq/Afghanistan era veterans. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2017;205(7):512–516. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarmiento K, Rossettie J, Stepnowsky C, Atwood C, Calvitti A. VA Sleep Network. the state of Veterans Affairs sleep medicine programs: 2012 inventory results. Sleep Breath. 2016;20(1):379–382. doi: 10.1007/s11325-015-1184-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirshkowitz M, Sharafkhaneh A. A telemedicine program for diagnosis and management of sleep-disordered breathing: the fast-track for sleep apnea tele-sleep program. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;35(5):560–570. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fields BG, Behari PP, McCloskey S, et al. Remote ambulatory management of veterans with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2016;39(3):501–509. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gehrman P, Shah MT, Miles A, Kuna S, Godleski L. Feasibility of group cognitive-behavioral treatment of insomnia delivered by clinical video telehealth. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(12):1041–1046. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2016.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munafo D, Hevener W, Crocker M, Willes L, Sridasome S, Muhsin M. A telehealth program for CPAP adherence reduces labor and yields similar adherence and efficacy when compared to standard of care. Sleep Breath. 2016;20(2):777–785. doi: 10.1007/s11325-015-1298-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernstein AM, Allexandre D, Bena J, et al. “Go! to Sleep”: a web-based therapy for insomnia. Telemed J E Health. 2017;23(7):590–599. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2016.0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woehrle H, Ficker JH, Graml A, et al. Telemedicine-based proactive patient management during positive airway pressure therapy: Impact on therapy termination rate. Somnologie (Berl) 2017;21(2):121–127. doi: 10.1007/s11818-016-0098-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hwang D, Chang JW, Benjafield AV, et al. Effect of telemedicine education and telemonitoring on continuous positive airway pressure adherence. The Tele-OSA randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(1):117–126. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201703-0582OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watson NF, Rosen IM, Chervin RD. Board of Directors of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine The past is prologue: the future of sleep medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(1):127–135. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baig MM, Antonescu-Turcu A, Ratarasarn K. Impact of sleep telemedicine protocol in management of sleep apnea: a 5-year VA experience. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(5):458–462. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2015.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cramer TV. A’s “Telesleep” a Breath of Fresh Air. Veterans Health Administration News Feature. Published July 18, 2013. Accessed March 14, 2019.

- 29.Kuna ST, Shuttleworth D, Chi L, et al. Web-based access to positive airway pressure usage with or without an initial financial incentive improves treatment use in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2015;38(8):1229–1236. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berry RB, Hill G, Thompson L, McLaurin V. Portable monitoring and autotitration versus polysomnography for the diagnosis and treatment of sleep apnea. Sleep. 2008;31(10):1423–1431. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuna ST, Gurubhagavatula I, Maislin G, et al. Noninferiority of functional outcome in ambulatory management of obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(9):1238–1244. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1770OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Russo JE, McCool RR, Davies LVA. Telemedicine: an analysis of cost and time savings. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(3):209–215. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2015.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Office of Rural Health, https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/aboutus/ruralvets.asp. Accessed March 14, 2019.

- 34.Singh J, Badr MS, Diebert W, et al. American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) position paper for the use of telemedicine for the diagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11(10):1187–1198. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The re-aim framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–1327. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]