Abstract

Study Objectives:

This secondary analysis characterized sleep patterns for toddlers born preterm and tested effects of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)+ arachidonic acid (AA) supplementation on children’s caregiver-reported sleep. Exploratory analyses tested whether child sex, birth weight, and caregiver depressive symptomatology were moderators of the treatment effect.

Methods:

Omega Tots was a single-site 180-day randomized (1:1), double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Children (n = 377) were age 10 to 16 months at enrollment, born at less than 35 weeks’ gestation, assigned to 180 days of daily 200 mg DHA + 200 mg AA supplementation or placebo (400 mg corn oil), and followed after the trial ended to age 26 to 32 months. Caregivers completed a sociodemographic profile and questionnaires about their depressive symptomatology (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) and the child’s sleep (Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire). Analyses compared changes in sleep between the DHA+AA and placebo groups, controlling for baseline scores. Exploratory post hoc subgroup analyses were conducted.

Results:

Eighty-one percent (ntx = 156; nplacebo = 150) of children had 180-day trial outcome data; 68% (ntx = 134; nplacebo = 122) had postintervention outcome data. Differences in change between the DHA+AA and placebo groups after 180 days of supplementation were not statistically significant for the entire cohort. Male children (difference in nocturnal sleep change = 0.44, effect size = 0.26, P = .04; sleep problems odds ratio = 0.36, 95% confidence interval = 0.15, 0.82) and children of depressed caregivers (difference in nocturnal sleep change = 1.07, effect size = 0.65, P = .006; difference in total sleep change = 1.10, effect size = 0.50, P = .04) assigned to the treatment group showed improvements in sleep, compared to placebo.

Conclusions:

Although there is no evidence of an overall effect of DHA+AA supplementation on child sleep, exploratory post hoc analyses identified important subgroups of children born preterm who may benefit. Future research including larger samples is warranted.

Clinical Trial Registration:

Registry: ClinicalTrials.gov; Identifier: NCT01576783

Citation:

Boone KM, Rausch J, Pelak G, Li R, Turner AN, Klebanoff MA, Keim SA. Docosahexaenoic acid and arachidonic acid supplementation and sleep in toddlers born preterm: secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(9):1197–1208.

Keywords: docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), preterm birth, randomized clinical trial, sleep

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Children born preterm are at increased risk of developmental delays and medical conditions that may exacerbate poor sleep quality. In animal models, DHA regulates melatonin synthesis and circadian clock functioning. Results in humans are mixed. No placebo-controlled trials have tested DHA+AA supplementation on sleep among toddlers born preterm.

Study Impact: Although no overall treatment effects of DHA+AA supplementation were observed for this preterm cohort, exploratory subgroup analyses identified important subgroups of children—males and children whose caregivers who reported depressive symptomatology—who may benefit from DHA+AA supplementation. If replicated in larger cohorts, results suggest that DHA+AA supplementation may be a readily available, cost-effective intervention for some children at risk for sleep deficiencies. Further exploration in larger samples is necessary to replicate findings.

INTRODUCTION

Children born preterm exhibit sleep disturbances, including reduced sleep duration, more nighttime waking episodes, lower sleep efficiency, sleep-disordered breathing, and more caregiver-reported sleep problems from infancy to middle childhood compared to their peers born at term.1–4 Poor sleep quality is linked to obesity, motor and cognitive impairments, and increased unintentional injuries, whereas longer sleep duration is associated with positive outcomes such as increased executive control and better health throughout early childhood.5–7 In addition to experiencing sleep disturbances, children born preterm are at increased risk of physical, neurological, behavioral, and social-emotional delays and chronic medical conditions that may exacerbate poor sleep quality for these children.8–14 Therefore, sleep interventions aimed at children born preterm may not only improve sleep, but also be beneficial to their short- and long-term developmental and health outcomes.

Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) is the major structural fatty acid in the developing brain and DHA accretion is rapid from birth through age 2 years.15–19 DHA and arachidonic acid (AA) are nutrients found in the pineal gland, a part of the brain that aids in sleep regulation, and lower levels of DHA are associated with poorer sleep.20–22 DHA intake can enhance DHA levels in the membrane of pineal cells and improve synthesis of melatonin, a hormone located in the pineal gland that regulates sleep cycles.20,21 In animal models, omega-3 fatty acids, particularly DHA, regulate melatonin synthesis and circadian clock functioning; however, results related to whether fatty acid supplementation affects sleep in humans are mixed and randomized trials are few.20,21 Children born preterm miss some or all of the rapid acquisition of DHA and other fatty acids that occurs in the third trimester of pregnancy.23 Therefore, DHA supplementation during toddlerhood may help improve brain function, and ultimately sleep quality, for children born preterm.

Although significant improvements in sleep for children aged 7 years to 12 years assigned to DHA supplementation compared to a placebo have been reported, no placebo-controlled trials have tested omega fatty acid supplementation for effects on sleep quality among children born preterm during toddlerhood.22,24 This is an important time to intervene because it is a period of rapid change in sleep patterns and a critical window for establishing good sleep habits. Additionally, evidence suggests that during toddlerhood, especially, sleep is moderated by child sex, birth weight, and caregiver depression such that boys, children born at lower birth weights, and children of depressed caregivers experience poorer sleep.25–30

The objectives of this secondary analysis aimed to characterize sleep patterns for toddlers born preterm and to test the effects of combined DHA and AA supplementation for 180 days on caregiver-reported sleep in a sample of toddlers born at < 35 completed weeks’ gestation, both at the end of the 180-day trial and at postintervention follow-up an average of 8 months after the intervention ended. Exploratory subgroup analyses and interactions tested whether child sex, birth weight (< 1,250 g versus ≥ 1,250 g), and caregiver depressive symptomatology (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale [CES-D] < 16 versus CES-D ≥ 16) were moderators of the treatment effect on sleep outcomes.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

The Omega Tots trial was a single-site, randomized (1:1), double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial (NCT01576783) conducted at Nationwide Children’s Hospital (NCH; Columbus, Ohio, USA). The Institutional Review Board at NCH reviewed and approved the study. Each child’s caregiver provided written informed consent for participation. Enrollment in the 180-day trial took place between April 2012 and September 2016, and data collection was completed in March 2017. A postintervention follow-up study, separately approved by the Institutional Review Board at NCH, examined effects several months after the supplementation period. Eligible children for the postintervention study were between 26 and 32 months of (chronological) age between October 2014 and February 2018, when the postintervention follow-up study was conducted via an online or mailed questionnaire. Examination of sleep in this cohort was not a prespecified primary outcome of the trial, but caregiver-reported sleep measures were included in the study protocol from the beginning to explore treatment effects on this domain. Analysis of the primary outcomes for the Omega Tots trial show that supplementation resulted in no improvement in cognitive development and early measures of executive function and may have resulted in negative effects on language development and effortful control in certain subgroups of children. A detailed report of these findings and the full protocol are presented elsewhere.31

Participants and Sample Size

Participants in the Omega Tots trial were children 10 to 16 months of age (adjusted for prematurity) at enrollment who were (1) born at less than 35 completed weeks’ gestation and (2) admitted to a Columbus, Ohio Neonatal Intensive Care Unit post birth or (3) had a neonatology clinic follow-up visit scheduled at NCH.

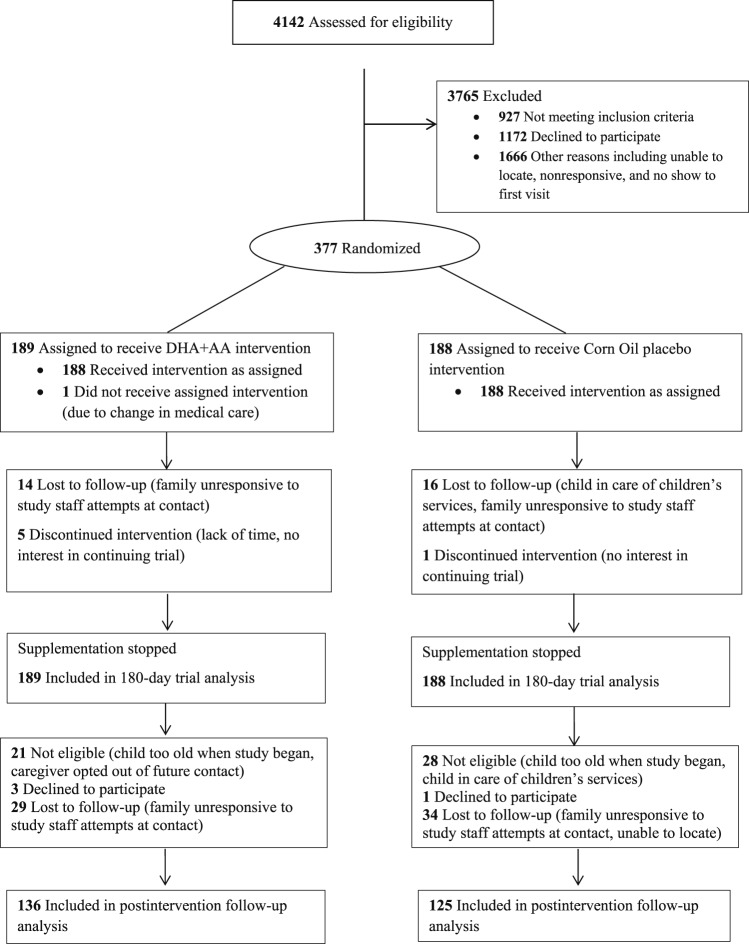

Eligible children weighed between the 5th and 95th percentiles for corrected age and sex per World Health Organization standards,32 had discontinued human milk and formula, and had English as their primary language. Children were excluded for consuming fatty acid supplements, fatty fish, or nutritional support beverages with DHA more than twice weekly; having fish, corn, or soy allergy; planning to relocate; or having a major malformation or feeding, metabolic, or digestive disorder precluding participation or nutrient absorption. In total, 377 children enrolled and were randomized to the 180-day trial, all of whom were included in this analysis (Figure 1). The study was powered based on the primary outcome. An original sample of 448 was planned to achieve > 80% power to detect a 4.2-point difference (0.28-standard deviation [SD]) on the primary outcome (eg, Bayley-III); however, the investigational product manufacturer discontinued production when 377 children were enrolled. Exclusion criteria for the postintervention follow-up study included child chronological age of 33 months or older or child in the care of children's services. Caregivers of 328 children were eligible to participate in the postintervention follow-up study. Caregivers of 261 (80% response) children participated.

Figure 1. Participant CONSORT Flow Diagram, Omega Tots trial and postintervention follow-up (n = 377), 2012–2018.

Randomization, Blinding, and Intervention

Children were allocated to one of four color-coded groups (two groups for treatment, two groups for placebo) using a randomization scheme with a varying block size of 4 and 8 and with 1:1 allocation to treatment (DHA+AA) or placebo. Four randomization groups were used to preserve blinding of treatment assignment as much as possible, should unblinding of a child have been necessary for emergency reasons. A statistician who had no contact with participants prepared the randomization scheme, assigned ID numbers, and prepared opaque, sealed, tamper-resistant envelopes before the study began. Upon enrollment, study staff opened the next sequentially numbered envelope to assign children to DHA+AA or placebo. All investigators, families, and staff remained blinded throughout the trial. Members of sets of twins and triplets were randomized together to the same group to reduce the likelihood of accidental treatment crossover and to increase the consent rate among families with multiples.33

The treatment group was assigned to 180 days of daily oral supplementation with dissolvable, microencapsulated DHA, 200 mg (from Schizochytrium species algal oil), and AA, 200 mg (from fungal Mortierella alpine oil) powder (DSM Nutritional Products USA). The dose was selected to approximate the peak daily DHA consumed per body weight during infancy (ie, for a typical 4-month-old infant, 20 mg/kg/d). Both DHA and AA were included in a 1:1 balance, as this has been shown to support child growth and it mirrors the ratio found in infant formula. The 180-day period ensured significant incorporation of DHA into neuronal cell membranes while maximizing enrollment and retention. The placebo group was assigned to 180 days of matching placebo: 400 mg of a daily microencapsulated corn oil powder. DSM Nutritional Products packaged both products identically in foil packets. The NCH Investigational Drug Services distributed the investigational drug directly to the family. This group advised families, verbally and with written instructions on the foil packets, to have the child consume two packets of powder daily and to dissolve the powder in the child’s milk or food for the duration of the trial.

Data Collection

The baseline study visit (day 0) included a caregiver-completed questionnaire which collected demographics (child’s race and ethnicity, caregiver relationship to the child, age, relationship status, education, insurance status, annual household income), child diet, child sleep, and caregiver depressive symptomatology. Sleep and diet were assessed again at the end of the trial (day 180), and sleep was assessed a third time at postintervention follow-up. The end of the 180-day trial visit was the prespecified timepoint of primary interest. At the last trial study visit, the caregiver was asked to guess their child’s treatment assignment. The child’s electronic medical record was the source of child age, gestational age, and birth weight information.

Caregivers reported the number of servings per month of fatty fish (eg, salmon), moderately fatty fish (eg, tuna), and white fish/shellfish (eg, fish sticks) the child consumed using the DHA Food Frequency Questionnaire (DHA-FFQ).34 Results of this questionnaire provided an estimated DHA and eicosapentaenoic acid (or EPA, a prescursor to DHA) intake (mg/d). Intake as reported on this questionnaire is positively correlated with plasma phospholipid and erythrocyte fatty acid levels.34

Sleep characteristics were obtained using the Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire (BISQ).35 During the 180-day trial the following sleep characteristics were captured and served as the outcomes of interest: nocturnal sleep duration (hours), daytime sleep duration (hours), total sleep duration within a 24-hour period (hours), nocturnal sleep-onset time (minutes), duration of wakefulness during night hours (minutes), number of nighttime waking episodes (none versus one or more waking episodes), method of falling asleep (while being held or rocked versus while feeding or in bed), short sleep duration (less than 11 hours per 24 hours versus 11 hours or more), and caregiver perception of sleep problems (no problem versus small or serious problem). In addition, the BISQ assessed location of sleep and preferred body position during sleep. Postintervention follow-up included caregiver reported nocturnal sleep duration, daytime sleep duration, total sleep duration within a 24-hour period, and nocturnal sleep-onset time. Caregiver reports on the BISQ were validated with actigraphy and sleep logs when the measure was originally developed.3,35

The CES-D scale assessed caregiver depressive symptomatology.36 This 20-item instrument asked caregivers to rate how often they experienced depressive symptomatology in the past week. Participants rated each item on a scale ranging from zero meaning “rarely or none of the time (less than 1 day)” to three meaning “most or all of the time (5 to 7 days).” Higher scores were indicative of more depressive symptomatology, with scores of 16 or higher representing risk for clinical depression, as is recommended by the instrument developers.36

Adherence and Adverse Events

Diaries where caregivers circled the number of packets their child was given each day for the duration of the 180-day trial measured adherence with taking the supplement or placebo. Families were contacted regularly to encourage adherence and address participation barriers. The study doctor reviewed adverse events, defined as any change in health or behavior during the trial, whether or not it was considered to be related to the intervention.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses used SAS software (v9.3, SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, United States) and were conducted according to intent-to-treat methods (all randomized children were included).37 No interim analyses were conducted. Analyses of treatment effects compared the change in sleep characteristics between groups, controlling for baseline characteristics, using a linear mixed model (analogous to analysis of covariance), per the method of Winkens et al., which leverages maximum likelihood estimation to account for missing data for continuous variables.38 Treatment-by-time interaction terms were included as fixed effects and served as estimates of treatment effect. Adjustments for multiple comparisons were not made.39,40 To address statistical nonindependence because of the inclusion of multiple gestation births, analyses included a random effect for the family unit within the mixed model. Group mean differences divided by SD were calculated as standardized effect sizes for each outcome. Analyses for binary outcomes (ie, experiences nighttime waking episode(s), falls asleep while being rocked/held, short sleep duration, sleep problem) were completed using generalized estimating equations and logistic regression, adjusted for baseline scores. Because evidence suggests child sleep is affected by child sex, birth weight, and caregiver depression, we used three-way interaction terms (timepoint × treatment × moderator) to test whether child sex, birth weight (< 1,250 g versus ≥ 1,250 g), and presence of caregiver depressive symptomatology (CES-D < 16 versus CES-D ≥ 16) at the baseline visit were moderators of the treatment effect on sleep outcomes.25,27,28,30,41,42 In cases where the interaction was P ≤ .10, exploratory post hoc subgroup analyses based on these variables were performed. Outcomes with significant moderation of treatment effects from baseline to trial end (ie, day 180) were then examined for postintervention treatment effects from baseline to several months after the trial and supplementation ended.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

The median age of children was 15.7 (interquartile range [IQR]: 13.6, 16.5) months (adjusted for prematurity) at enrollment and 15.5% were born at 28 completed weeks’ gestation or less. On average, children weighed 1,727 g at birth and 48% were female. All but one child received their randomized intervention. Eighty-one percent of enrolled children (ntx = 156; nplacebo = 150) had sleep outcome data at the end of the 180-day trial and 68% of enrolled children (ntx = 134; nplacebo = 122) had sleep outcome data at postintervention follow-up (mean = 8.1 months after the trial ended, SD = 2.8). Caregiver respondents were mostly mothers (96%), with a mean age of 31 (SD = 7.2) years. Two-thirds of caregivers were married or living with a partner, 36% had a bachelor’s degree level education or higher, 50% reported having public or no insurance, 47% reported an annual household income of less than $35,000 USD, and approximately 17% reported depressive symptomatology as measured by having a CES-D score ≥ 16. Baseline characteristics were similar across treatment groups (Table 1). Caregivers who participated in postintervention follow-up had younger children at trial enrollment (15.3 months versus 16.0 months at enrollment) and reported lower rates of having public or no health insurance (46% versus 59%) compared to caregivers of children who did not participate in the postintervention follow-up (Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics at baseline, Omega Tots trial, 2012–2017.

Caregiver-reported Sleep at Baseline

Most children (55%) fell asleep in a bed alone, and 22% fell asleep while being held or rocked (Table 1). Children were reported to sleep 12.5 hours (SD = 1.9) per 24 hours, with approximately 9.8 hours (SD = 1.6) comprising nocturnal sleep duration; 16% of children slept for fewer than 11 hours per day. Caregivers reported that it took 28.9 minutes (SD = 30.9) to put the child to sleep; however, 16% reported that it took 1 hour or longer to put their child to sleep. Approximately 44% of children did not experience any nighttime waking episodes; 24% of the sample woke two or more times per night. Caregivers reported that children experienced about 28.5 minutes (SD = 63.7) of night wakefulness, with 17% of caregivers reporting that their child spent 1 hour or longer in night wakefulness. Seventeen percent of caregivers reported that their child’s sleep was a problem.

180-day Trial Treatment Effects on Caregiver-reported Sleep

Differences in change between the DHA+AA and placebo groups on nocturnal sleep duration (ΔDHA+AA = 0.25 hours, ΔPlacebo = −0.16 hours, effect size = 0.16, P = 0.11), daytime sleep duration (ΔDHA+AA = −0.32 hours, ΔPlacebo = −0.46 hours, effect size = −0.09, P = 0.47), total sleep duration (ΔDHA+AA = −0.07 hours, ΔPlacebo = −0.60 hours, effect size = 0.07, P = 0.32), sleep onset time (ΔDHA+AA = 9.0 minutes, ΔPlacebo = 4.8 minutes, effect size = 0.09, P = 0.35), and night wakefulness (ΔDHA+AA = −3.0 minutes; ΔPlacebo = 6.4 minutes, effect size = −0.01, P = 0.82) were not statistically significant for the full cohort (Table 2A, 2B). Additionally, change in sleep characteristics between DHA+AA and placebo groups were not statistically significant for binary sleep characteristics: nighttime waking episodes (OR = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.51, 1.48), falling asleep while being held or rocked (OR = 0.65, 95% CI = 0.30, 1.40), short sleep duration (OR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.52, 1.75), or caregiver-reported sleep problems (OR = 0.70, 95% CI = 0.38, 1.27) for the entire cohort (Table 3).

Table 2A.

Change in sleep outcomes from baseline to 180-day trial completion, Omega Tots trial, 2012–2017.

Table 2B.

Change in sleep outcomes from baseline to 180-day trial completion, Omega Tots trial, 2012–2017.

Table 3.

Odds of caregiver-reported binary sleep characteristics, Omega Tots trial, 2012–2017.

Significant interactions were observed between treatment group assignment and child sex (nocturnal sleep duration: P = .10) and between treatment group assignment and caregiver depressive symptomatology (nocturnal sleep duration: P = .01; total sleep duration: P = .02). No statistically significant interactions were observed between treatment group assignment and birth weight (Table S2 and Table S3 in the supplemental material for exploratory birth weight subgroup analyses).

Exploratory subgroup analyses based on child sex and caregiver depressive symptomatology suggested possible treatment effects at the conclusion of the 180-day trial. Caregivers of male children randomized to the DHA+AA group reported nearly 30 minutes of increased nocturnal sleep duration, compared to an approximate 15-minute decrease in nocturnal sleep duration reported by caregivers of males randomized to placebo (effect size = 0.26, P = .04, Table 2A, 2B). Additionally, caregivers of male children assigned to DHA+AA reported a dramatic decrease in sleep problems from baseline to the end of the 180-day trial (OR = 0.36, 95% CI = 0.15, 0.82; Table 3), compared to the placebo group. Caregivers who reported depressive symptomatology, defined as scoring ≥ 16 on the CES-D, and whose children were randomized to DHA+AA reported that their children experienced almost 1 full hour of increased nocturnal sleep from baseline to the end of the 180-day trial, compared to an approximate 13-minute decrease in nocturnal sleep duration for children of depressed caregivers randomized to placebo (effect size = 0.65, P = .006, Table 2A, 2B). This subgroup effect was reflected in total sleep duration as well (ΔDHA+AA = 0.30 hours; ΔPlacebo = −1.31 hours, effect size = 0.50, P = .04, Table 2A, 2B).

Postintervention Treatment Effects on Caregiver-reported Sleep

Aspects of sleep that were found to be affected by DHA+AA supplementation at the end of the 180-day trial were further explored to see if the treatment effects persisted at postintervention follow-up, approximately 8 months after the 180-day trial ended. Caregivers of male children randomized to the DHA+AA group reported approximately 8 minutes of increased nocturnal sleep duration from baseline to postintervention follow-up, compared to an approximate 40- minute decrease in nocturnal sleep duration reported for males randomized to placebo (effect size = 0.38, P = .01, Table 2A, 2B). Nocturnal sleep duration did not significantly differ between DHA+AA and placebo at postintervention follow-up for children of caregivers who reported depressive symptomatology (ΔDHA+AA = 0.54 hours, Δplacebo = −0.37 hours, effect size = 0.47, P = .07, Table 2A, 2B). Children of caregivers with depressive symptomatology experienced 15 minutes of increased total sleep from baseline to postintervention follow-up, compared to an approximate 90-minute decrease in total sleep duration for children of depressed caregivers randomized to placebo (effect size = 0.58, P = .01, Table 2A, 2B).

Adherence, Blinding, and Adverse Events

Adherence with taking the daily treatment or placebo was high: children consumed 81% of the total prescribed amount of powder based on caregiver-reported diaries. At the end of the trial, 55% of caregivers in the treatment group and 60% of those in the placebo group guessed their child was assigned to the treatment group, suggesting family-level blinding remained intact (χ2 = 0.65, P = .42). Two hundred fifty-six children experienced at least one adverse event, totaling 683 events (1.7/child in the DHA+AA group, 2.0/child in the placebo group, group difference = −0.37, 95% CI = −0.07, 0.80, P = .10). The most commonly reported adverse events were minor gastrointestinal illness and respiratory tract infections; none were judged to be serious and related to the intervention.

DISCUSSION

This is the first randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial to explore the effect of DHA+AA supplementation on caregiver-reported sleep in a sample of toddlers born at < 35 completed weeks’ gestation. This secondary analysis showed that although supplementation did not significantly affect child sleep in the full cohort, supplementation may have had a positive effect on sleep outcomes for important subgroups of children. Specifically, male children and children whose caregivers reported depressive symptomatology appeared to benefit from DHA+AA supplementation in our exploratory subgroup analyses, and these positive effects were present months after supplementation stopped. The results are encouraging and provide preliminary support for further exploration of omega fatty acid supplementation during toddlerhood to improve sleep among children born preterm.

Caregivers in the Omega Tots trial reported sleep patterns for their children that are consistent with other studies, suggesting that children born preterm may not be sleep deficient relative to their peers.27,28,43,44 Despite these similarities, 16% of caregivers in the Omega Tots trial reported their children slept less than the American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommendation of between 11 and 14 hours per 24-hour period.6 This is problematic because poor sleep quality is linked to poor health and developmental outcomes for children.5–7,27 Because children born preterm experience physical, neurological, behavioral, and social-emotional delays and chronic medical conditions that may exacerbate poor sleep at higher rates than children born at term, identifying reliable, cost-effective sleep interventions for this unique group of children is essential.

Previous work demonstrated that boys experience shorter sleep duration than girls through school age and that risks for poor sleep differ by child sex.25–29 At the end of this 180-day trial and at postintervention follow-up, caregivers of male children randomized to the DHA+AA group reported improvements in their child’s sleep, whereas caregivers of male children randomized to placebo did not. The magnitude of this effect was small.

The relationship between poor child sleep and caregiver depression is well documented. Prior research shows inverse associations between caregiver well-being, inclusive of depression, and optimal child sleep characteristics, particularly for toddlers. For example, increased caregiver depression has been associated with more nighttime waking episodes for children at 18 months of age, but not at 6 months.30 In the current study, there was a moderate effect of DHA+AA supplementation for children of caregivers who reported depressive symptomology and who were randomized to receive DHA+AA, both at the end of the 180-day trial and several months later at postintervention follow-up. The pathway of this association is still a point of debate, and few studies have compared caregiver and child drivers of the effect simultaneously.45 Recent evidence which tested a reciprocal model whereby caregiver depression directly affects child sleep and child sleep directly affects caregiver depression suggests that although both caregiver- and child-driven transactions are at play, the effect of child sleep on caregiver depression is stronger than the effect of caregiver depression on child sleep.41 Additionally, others have shown that omega-3 supplementation is associated with reduced problematic behavior in children and consequent improvements in psychopathology for their caregivers.46 Based on these findings, improvements in child sleep may translate to reduction in caregiver depressive symptomatology; however, this could not be directly tested in this study.

A randomized clinical trial of maternal DHA supplementation (versus placebo) during pregnancy reported better infant sleep outcomes in the first two days of life for infants of mothers randomized to DHA.47 Few studies have supplemented the diets of children to examine effects of DHA on sleep. Those that have are based on non-US general population samples of children, supplemented diets for shorter periods of time (4 months versus 6 months in this study), and reported mixed results, making generalization to US-based pediatric populations, who may have dietary differences, difficult. One UK-based study reported improvements in sleep duration for children age 7 to 9 years randomized to DHA supplementation (versus placebo), based on objective measures of sleep (ie, actigraphy), but not parent-reported sleep measures.22 To date, one randomized clinical trial tested the effects of fatty fish intake (versus meat) on sleep characteristics of preschool-aged children. This Norwegian study found no overall effect of supplementation on caregiver-reported sleep, despite higher biological increases in DHA during the intervention period, however, a post hoc analysis identified positive effects for children who had caregiver-reported sleep problems at baseline.48 Notably, regardless of the population, no study identified overall treatment effects of DHA supplementation on caregiver-reported child sleep, but certain subgroups of children who may be at greatest risk for poor sleep appeared to show benefit from increased DHA intake.

Both DHA and AA aid in sleep regulation, and supplementation may improve synthesis of melatonin, a hormone that regulates sleep cycles, especially for those who are already at risk for poor sleep.20–22 Despite no overall treatment effect of DHA on sleep, findings from our exploratory subgroup analyses show that certain subgroups of children—males and those of caregivers with depressive symptomatology—may benefit. With the established evidence that male children and children of caregivers who report depressive symptomatology experience poorer sleep, supplementation at a critical juncture when children wean off of DHA-containing breastmilk and formula to a low omega-3 diet (ie, toddlerhood) may facilitate the synthesis of melatonin and ultimately serve to promote positive sleep-wake cycles, with benefits lasting beyond toddlerhood. Further exploration and replication in larger samples of male children and children of caregivers with depressive symptomatology are needed.

Because of the importance of good sleep quality for toddlers and the demonstrated associations that child sleep has with child and family health and well-being, many interventions aimed at improving infant and toddler sleep outcomes exist. Of the few experimental studies that have tested the effects of behavioral sleep interventions for children, some show that bedtime routines inclusive of child massage and participation in an online intervention with tailored sleep recommendations have a positive effect on child sleep.49,50 Nutritional support can be administered early and over a long period with minimal cost and inconvenience for the family and may provide additional benefit if proven efficacious in additional larger samples of children, particularly those at high risk of sleep problems. Treatment adherence in this cohort was greater than 80%, illustrating that this is a feasible approach for families with young children born preterm.

There are limitations of this study. This study relied on caregiver-reported sleep; therefore, caregiver bias cannot be ruled out. Caregivers who reported depressive symptomatology may report their children’s sleep characteristics differently than caregivers who do not report depressive symptomatology. However, caregivers who reported depressive symptomatology and whose children were randomized to the placebo group did not report the same large improvements in their child’s sleep characteristics as those whose children were randomized to receive DHA+AA supplementation. Therefore, data from the Omega Tots trial demonstrate that the reports of children’s sleep provided by caregivers who reported depressive symptomatology do not explain this finding. Additionally, we relied on caregiver report of adherence. Although caregivers reported that they mixed > 80% of the prescribed dose in the child’s food, we cannot be certain the child finished the food in which the powder was mixed. Next, within the placebo group 28% of caregivers who reported depressive symptomatology at baseline did not participate in the final study visit at the end of the 180-day trial, compared to only 10% randomized to the DHA+AA group. Although it is possible that this may affect the findings reported within, a post hoc analysis showed that baseline sleep characteristics for children of caregivers who reported depressive symptomatology and who were randomized to the placebo group did not statistically differ between those who participated in the final 180-day trial study visit and those who did not participate in the final 180-day trial study visit (t = 0.28, P = .78). Caregiver depressive symptomatology was assessed at baseline. As such, this study could not evaluate changes in caregiver depressive symptomatology throughout the duration of the study. We did not capture data on the child’s sleep hygiene, bedtime routine, or sleep disorders that may affect sleep onset time or nighttime wakefulness. However, given that children were randomized to DHA+AA or placebo, we expect that the presence of any of these things was evenly distributed across groups. Finally, power for the study was not determined based on power to detect an effect of supplementation on sleep because this was not the primary outcome and the subgroup analyses were exploratory.

In addition, there are several strengths to this work. Because multiple gestation births are common among preterm births, they are often included in clinical trials related to prematurity outcomes. This increases generalizability to the larger preterm population. Because we drew our participants from a roster of all children who required neonatal intensive care, our source population was not subject to some of the participation bias seen in studies that rely purely on volunteers or patients of neonatal follow-up clinics. Finally, because caregivers were poor at correctly guessing their child’s treatment assignment, we can rule out accidental unblinding or caregiver suspicions about their child’s treatment assignment as an influence on caregiver reports of sleep.

Although no overall treatment effect of DHA+AA supplementation on child sleep was identified in the Omega Tots trial, exploratory post hoc subgroup analyses identified important groups of children who may benefit from DHA+AA supplementation. Daily supplementation with 200 mg DHA and 200 mg AA for 180 days compared to placebo resulted in greater improvements in sleep for male children born preterm and children born preterm whose caregivers reported depressive symptomatology, both at the end of the 180-day trial and several months later at postintervention follow-up. However, given the short time frame of this study, the small sample size of the relevant subgroups, and the post hoc design, these findings should be interpreted with caution. The results of this study represent a very positive first step to elucidate readily available, cost-effective interventions with positive effects for children at risk for sleep deficiencies. Future research including larger samples of male children and of children of caregivers with depressive symptomatology are warranted to further explore the effects of DHA+AA supplementation for these important subgroups of families.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This study was supported by grants from the US Health Resources and Services Administration (R40MC28316), the March of Dimes (12-FY14-171), the Allen Foundation, Cures Within Reach, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/National Institutes of Health (UL1TR001070), and internal support from The Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the US Department of Health and Human Services. DSM Nutritional Products provided the investigational products at no cost. This information or content and conclusions are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government, or the other study supporters. All authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript. Work for this study was performed at the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, OH. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the participants; NCH Division of Neonatology; NCH Investigational Drug Service; DSM as well as the entire Omega Tots Research Team: Dkeama Alexis, Seanceray Bellinger, Holly Blei, Ashlea Braun, Anne Brown, Lautaro Cabrera, Chelsea Dillon, Connor Grannis, Nathan Hanna, Chenali Jayadeva, Justin Jackson, Sarah Landry, Julia Less, Melissa Kwitowski, Krista McManus, Emily Messick, Yvette Noah, Grace Pelak, Evan Plunkett, John Rissell, Ashley Ronay, Justin Jackson, Kamma Smith, Katie Smith, Sarah Snyder.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AA

arachidonic acid

- BISQ

Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire

- CES-D

Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression

- DHA-FFQ

DHA Food Frequency Questionnaire

- DHA

docosahexaenoic acid

- NCH

Nationwide Children’s Hospital

REFERENCES

- 1.Yiallourou SR, Arena BC, Wallace EM, et al. Being born too small and too early may alter sleep in childhood. Sleep. 2017;41(2):1–11. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsx193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stangenes KM, Fevang SK, Grundt J, et al. Children born extremely preterm had different sleeping habits at 11 years of age and more childhood sleep problems than term-born children. Acta Paediatr. 2017;106(12):1966–1972. doi: 10.1111/apa.13991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang YS, Paiva T, Hsu JF, Kuo MC, Guilleminault C. Sleep and breathing in premature infants at 6 months post-natal age. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14(1):303. doi: 10.1186/s12887-014-0303-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosen CL, Larkin EK, Kirchner HL, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing in 8- to 11-year-old children: Association with race and prematurity. J Pediatr. 2003;142(4):383–389. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2003.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tham E, Schneider N, Broekman B. Infant sleep and its relation with cognition and growth: a narrative review. Nat Sci Sleep. 2017;9:135–149. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S125992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paruthi S, Brooks LJ, D’Ambrosio C, et al. Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: a consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(6):785–786. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaput JP, Gray CE, Poitras VJ, et al. Systematic review of the relationships between sleep duration and health indicators in the early years (0-4 years) BMC Public Health. 2017;17(Suppl 5):855. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4850-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nilsson PM, Ignell C. Health consequences of premature birth revisited - what have we learned? Acta Paediatr. 2017;106(9):1378–1379. doi: 10.1111/apa.13939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Twilhaar ES, de Kieviet JF, Aarnoudse-Moens CS, van Elburg RM, Oosterlaan J. Academic performance of children born preterm: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2017;103(4):F322–F330. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-312916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luu TM, Rehman Mian MO, Nuyt AM. Long-term impact of preterm birth: neurodevelopmental and physical health outcomes. Clin Perinatol. 2017;44(2):305–314. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhutta AT, Cleves MA, Casey PH, Cradock MM, Anand KJ. Cognitive and behavioral outcomes of school-aged children who were born preterm: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2002;288(6):728–737. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.6.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Kieviet JF, van Elburg RM, Lafeber HN, Oosterlaan J. Attention problems of very preterm children compared with age-matched term controls at school-age. J Pediatr. 2012;161(5):824–829. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caravale BSS, Cannoni E, Marano A, Riolo E, Devescovi A, De Curtis M, Bruni O. Sleep characteristics and temperament in preterm children at two years of age. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(9):1081–1088. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manuel A, Witmans M, El-Hakim H. Children with a history of prematurity presenting with snoring and sleep-disordered breathing. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(8):2030–2034. doi: 10.1002/lary.23999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bazan NG. Cell survival matters: docosahexaenoic acid signaling, neuroprotection and photoreceptors. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29(5):263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitajka K, Puskas LG, Zvara A, et al. The role of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in brain: modulation of rat brain gene expression by dietary n-3 fatty acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(5):2619–2624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042698699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coti Bertrand P, O’Kusky JR, Innis SM. Maternal dietary (n-3) fatty acid deficiency alters neurogenesis in the embryonic rat brain. J Nutr. 2006;136(6):1570–1575. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.6.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salem N, Litman B, Kim HY, Gawrisch K. Mechanisms of action of docosahexaenoic acid in the nervous system. Lipids. 2001;36(9):945–959. doi: 10.1007/s11745-001-0805-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simopoulos AP. Omega-3 fatty acids in inflammation and autoimmune diseases. J Am Coll Nutr. 2002;21(6):495–505. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2002.10719248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zaouali-Ajina M, Gharib A, Durand G, et al. Dietary docosahexaenoic acid-enriched phospholipids normalize urinary melatonin excretion in adult (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acid-deficient rats. J Nutr. 1999;129(11):2074–2080. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.11.2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavialle M, Champeil-Potokar G, Alessandri JM, et al. An (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acid–deficient diet disturbs daily locomotor activity, melatonin rhythm, and striatal dopamine in syrian hamsters. J Nutr. 2008;138(9):1719–1724. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.9.1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montgomery P, Burton JR, Sewell RP, Spreckelsen TF, Richardson AJ. Fatty acids and sleep in UK children: subjective and pilot objective sleep results from the DOLAB study – a randomized controlled trial. J Sleep Res. 2014;23(4):364–388. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Innis SM. Essential fatty acid transfer and fetal development. Placenta. 2005;26(Suppl A):S70–S75. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yehuda S, Rabinovitz-Shenkar S, Carasso RL. Effects of essential fatty acids in iron deficient and sleep-disturbed attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) children. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65(10):1167–1169. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2011.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plancoulaine S, Lioret S, Regnault N, Heude B, Charles MA. Gender-specific factors associated with shorter sleep duration at age 3 years. Sleep Res. 2015;24(6):610–620. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sadeh A, Raviv A, Gruber R. Sleep patterns and sleep disruptions in school-age children. Dev Psychol. 2000;36(3):291–301. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.36.3.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDonald L, Wardle J, Llewellyn CH, van Jaarsveld CH, Fisher A. Predictors of shorter sleep in early childhood. Sleep Med. 2014;15(5):536–540. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blair PS, Humphreys JS, Gringras P, et al. Childhood sleep duration and associated demographic characteristics in an English cohort. Sleep. 2012;35(3):353–360. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bélanger ME, Bernier A, Simard V, Desrosiers K, Carrier J. Sleeping toward behavioral regulation: Relations between sleep and externalizing symptoms in toddlers and preschoolers. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2018;47(3):366–373. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2015.1079782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ystrom E, Hysing M, Torgersen L, Ystrom H, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Sivertsen B. Maternal symptoms of anxiety and depression and child nocturnal awakenings at 6 and 18 months. J Pediatr Psychol. 2017;42(10):1156–1164. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsx066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keim SA, Boone KM, Klebanoff MA, et al. Effect of docosahexaenoic acid supplementation vs placebo on developmental outcomes of toddlers born preterm: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(12):1126–1134. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.3082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group . WHO Child Growth Standards: Growth Velocity Based on Weight, Length and Head Circumference: Methods and Development. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009; [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernardo J, Nowacki A, Martin R, Fanaroff JM, Hibbs AM. Multiples and parents of multiples prefer same arm randomization of siblings in neonatal trials. J Perinatol. 2015;35(3):208–213. doi: 10.1038/jp.2014.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuratko C. Food-frequency questionnaire for assessing long-chain ω-3 fatty-acid intake: Re: Assessing long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids: a tailored food-frequency questionnaire is better. Nutrition. 2013;29(5):807–808. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sadeh A. A brief screening questionnaire for infant sleep problems: validation and findings for an internet sample. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6):e570–e577. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.e570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 37. SAS [computer program]. Version 9.3. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.

- 38.Winkens B, van Breukelen GJ, Schouten HJ, Berger MP. Randomized clinical trials with a pre- and a post-treatment measurement: Repeated measures versus ANCOVA models. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28(6):713–719. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rothman KJ. Six persistent research misconceptions. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):1060–1064. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2755-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rothman KJ. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology. 1990;1(1):43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ystrom H, Nilsen W, Hysing M, Sivertsen B, Ystrom E. Sleep problems in preschoolers and maternal depressive symptoms: An evaluation of mother- and child-driven effects. Dev Psychol. 2017;53(12):2261–2272. doi: 10.1037/dev0000402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gerardin P, Wendland J, Bodeau N, et al. Depression during pregnancy: is the developmental impact earlier in boys? A prospective case-control study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(3):378–387. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05724blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sadeh A, Mindell JA, Luedtke K, Wiegand B. Sleep and sleep ecology in the first 3 years: a web-based study. J Sleep Res. 2009;18(1):60–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Galland BC, Taylor BJ, Elder DE, Herbison P. Normal sleep patterns in infants and children: a systematic review of observational studies. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16(3):213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zuckerman B, Stevenson J, Bailey V. Sleep problems in early childhood: Continuities, predictive factors, and behavioral correlates. Pediatrics. 1987;80(5):664–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Portnoy J, Raine A, Liu J, Hibbeln JR. Reductions of intimate partner violence resulting from supplementing children with omega-3 fatty acids: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, stratified, parallel-group trial. Aggress Behav. 2018;44(5):491–500. doi: 10.1002/ab.21769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Judge MP, Cong X, Harel O, Courville AB, Lammi-Keefe CJ. Maternal consumption of a DHA-containing functional food benefits infant sleep patterning: An early neurodevelopmental measure. Early Hum Dev. 2012;88(7):531–537. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hysing M, Kvestad I, Kjellevold M, et al. Fatty fish intake and the effect on mental health and sleep in preschool children in FINS-KIDS, a randomized controlled trial. Nutrients. 2018;10(10):1478. doi: 10.3390/nu10101478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mindell JA, Lee CI, Leichman ES, Rotella KN. Massage-based bedtime routine: impact on sleep and mood in infants and mothers. Sleep Med. 2018;41:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mindell JA, Du Mond CE, Sadeh A, Telofski LS, Kulkarni N, Gunn E. Efficacy of an internet-based intervention for infant and toddler sleep disturbances. Sleep. 2011;34(4):451–458. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.4.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.