Abstract

The prognosis of women diagnosed with invasive high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma (HGSC) is poor. More information about Serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (STIC) and Serous tubal intraepithelial lesions (STILs), putative precursor lesions of HGSC could inform prevention efforts. We conducted a multicenter study to identify risk/protective factors associated with STIC/STILs and characterize p53 signatures in the fallopian tube.

The fallopian tubes and ovaries of 479 high-risk women ≥ 30 years of age who underwent bilateral risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy were reviewed for invasive cancer/STICs/STILs. Epidemiological data was available for 400 of these women. In 105 women extensive sampling of the tubes for STICs/STILs/p53 signatures were undertaken. Descriptive statistics were used to compare groups with and without lesions.

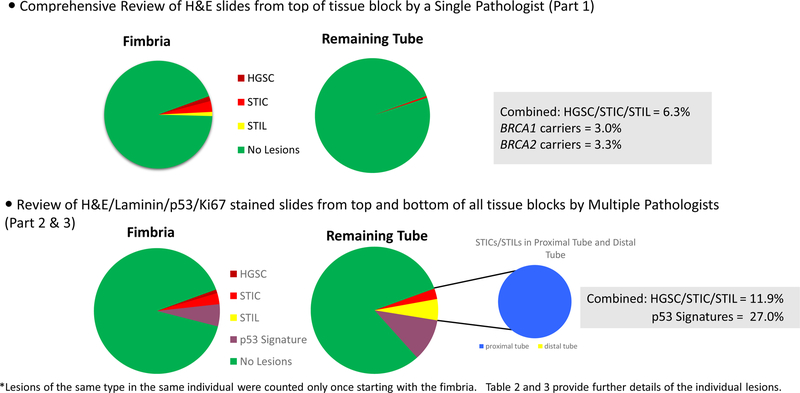

The combined prevalence of unique tubal lesions [invasive serous cancer (n=6) /STICs (n=14) /STILs (n=5)] was 6.3% and this was split equally among BRCA1 (3.0%) and BRCA2 mutation carriers (3.3%). A diagnosis of invasive cancer was associated with older age but no risk/protective factor was significantly associated with STICs/STILs. Extensive sampling identified double the number of STICs/STILs (11.9%), many p53 signatures (27.0%), and multiple lesions in 50% of cases. Women with p53 signatures in the fimbria were older than women with signatures in the remaining tube (p= 0.03).

STICs/STILs may not share the protective factors that are associated with HGSC. It is plausible that these factors are only associated with STICs that progress to HGSC. Having multiple lesions in the fimbria may be an important predictor of disease progression.

BACKGROUND

In the early 2000s closer examination of the fallopian tube in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers undergoing risk reduction salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) informed our understanding of invasive serous carcinomas of the fallopian tube and led to the classification of serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (STIC) a non-invasive lesion believed to be a precursor of high-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC) (1,2). The current theory is that STIC cells detach from their residence at the fallopian tube surface and disseminate to the nearby ovaries and peritoneal soft tissue where they form masses. This theory explains why most HGSC do not present at an early stage and the recent observation that women can develop peritoneal cancer post RRSO (3). Morphologically, STICs are characterized by a combination of nuclear enlargement, loss of polarity, increased nuclear atypia, aberrant p53 expression and increased proliferative activity (4,5). Serous tubal intraepithelial lesions (STILs) and p53 signatures have also been identified in the fallopian tube. STILs are lesions that just fall short of being classified as a STIC due to limited proliferation while p53 signatures have aberrant p53 immunostaining in at least 12 consecutive secretory nuclei in normal appearing non-proliferative tubal epithelium (6). The role if any of p53 signatures in the carcinogenic process has not been elucidated.

Demonstrating that STICs are a precursor of HGSCs has been extremely challenging due to the infeasibility of lesion biopsies and close monitoring of the tube. Compelling molecular evidence described by our research group and others however supports this notion (7–12). STICs have been identified in the fallopian tube of up to 59% of women with HGSC and in primary peritoneal serous carcinomas (13,14). Etiologically important genes and proteins associated with HGSC such as TP53 mutations & protein aberrant expression of p53, p21, cyclin E1, Rsf-1, laminin [gamma] γ1 protein, fatty acid synthase, stathmin1, and p16 have been identified in STICs (7–12). Molecular alterations reflective of DNA damage (expression of γH2AX, a marker of double stranded DNA breaks and pCHK2), oxidative damage (8-OHdG), and short telomere length have also been reported in both STICs and HGSC (8,15,16). By examining for predictors of STICs/STILs and invasive carcinoma in the fallopian tube we believe we can improve risk stratification and personalize preventive strategies in women at high-risk for ovarian cancer.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design:

The source population for this study is cancer-free women who are at high risk of developing ovarian/fallopian tube cancer because of carriage of a BRCA1/2 mutation or having at least 2 first and/or second-degree relatives of the same lineage with ovarian cancer. They also had to have undergone a RRSO at ≥ 30 years of age in one of four academic centers: Johns Hopkins University (JHU), University of Toronto, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), or Yale Cancer Center. Further the fallopian tubes and ovaries had to be processed in their entirety using the SEE-FIM Protocol (17). Women with prior histories of cancer were excluded with the exception of non-melanoma skin cancer or a diagnosis of breast cancer within the previous 10 years. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) at JHU approved the study and each study site obtained local IRB approval.

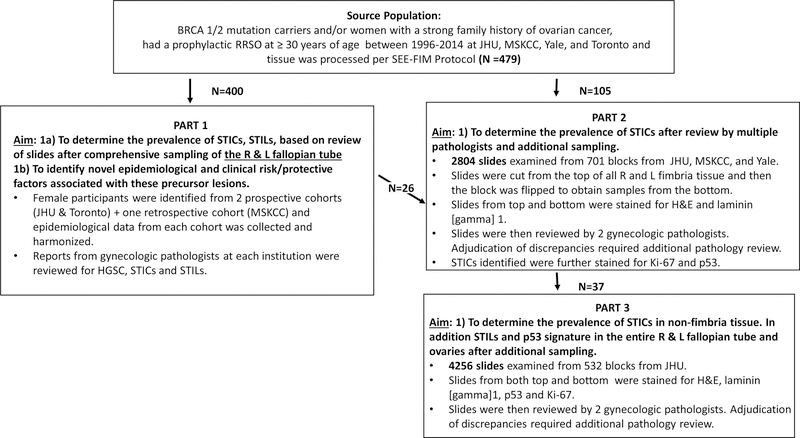

The study was divided into three parts as outlined in Figure 1. All parts involve women from the same source population described above. In part 1, 400 cancer-free women were identified from two prospective epidemiological cohorts at JHU (71 cases) (18) and Toronto (195 cases) and a retrospective cohort at MSKCC (134 cases). Serial sections of each tissue block from both tubes were stained for H&E, and p53 +/− Ki-67 staining was done at their institution on suspicious lesions for confirmation. Slides were reviewed for occult invasive carcinomas and STICs by at least one gynecological pathologist at each of the three sites and often by their tumor board. Yale was not included in this part of the study due to logistical issues regarding data linking. In part 2, 105 cancer-free women were identified from sequential cases undergoing RRSO at JHU (37 cases), MSKCC (33 cases) and Yale (35 cases) between 6/1/11 and 5/31/13. Cases from Toronto were not included because the institutional pathology review committee would not allow flipping of the tissue blocks. A further restriction was added to maximize detection of STICs/STILs and p53 signatures. The tissue blocks of cases could not have previously been used for research. This meant that only 26 cases from part 1 were eligible for part 2. For every case, as shown in supplement 1 the top and bottom of each fimbria block were sampled for STICs/STILs and p53 signatures. In part 3, all 37 cases from JHU were included and underwent extensive staining (top and bottom) of both tubes for STICs/STILs and p53 signatures.

Figure 1:

The consort diagram describing all three related parts of the study.

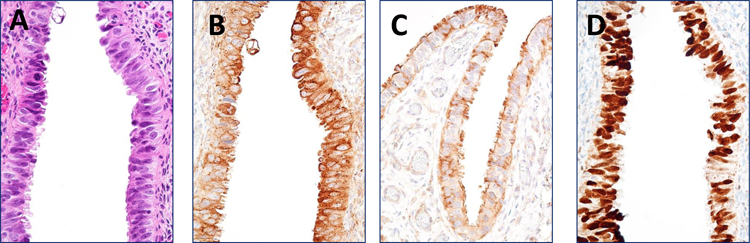

The diagnosis of STIC and STIL was based on a previously validated algorithm (4,5). Slides were initially stained for H&E and laminin γ1 as shown in Figure 2 instead of H&E and p53 to detect STICs and STILs and then cases positive for laminin γ1 and/or suspicious for a STIC/STIL on H&E were further stained for p53 and Ki-67. Laminin γ1 encodes for LAMC1 and has been shown in STICs to be positive when p53 is positive and in STICs that lacked p53 immunoreactivity due to frame shift, nonsense, or splicing junction mutations of TP53 null mutations (19). For p53 signatures we applied the same criteria used in a prior study (5). Two gynecological pathologists reviewed each case (RK, VP, IS, RS, RV) and were blinded to all clinical information. They were not given cases from their own institution. If the review was discordant, additional reviews were conducted by a third pathologist (RS) and if necessary a fourth pathologist (RK) who were blinded to prior reviews and clinical information. Laminin γ1 expression was scored as either positive or negative, p53 was scored as aberrant if diffuse expression (>75% of the cell) was present in at least 12 epithelial cells (with or without intervening ciliated cells) or there was complete absence of staining or non-abnormal pattern, and Ki-67 was categorized as <10% or ≥10% staining. STICs are expected to be laminin γ1 positive, p53 diffuse or completely negative and Ki-67 ≥ 10%. Quality controls were included in every batch.

Figure 2:

Morphological and immunostaining features of a representative STIC. A. H&E shows the atypical STIC cells. B. Laminin C1 staining exhibits an intense and diffuse immunoreactivity on the same STIC. C. Laminin C1 staining on the adjacent normal tubal epithelium. D.p53 staining shows a pattern compatible with a missense TP53 mutation.

Tissue Staining:

Immunohistochemistry for part 2 and 3 was performed at Johns Hopkins Immunopathology Laboratory; to assess the expression levels of p53 (clone Bp53–11, cat # 760–2542; Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ) and Ki-67 (clone 30–9, cat # 760–4286; Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ) in formalin fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections. All sections were immunostained automatically using either Ventana Benchmark Ultra or XT (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.). Immunoreactivity was detected by iView (cat # 760–091, Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.). Immunohistochemistry to assess laminin γ1 polyclonal antibody (cat # HPA001909, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) was performed manually in the Shih laboratory in accordance to manufacturer’s instructions (diluted 1:400) and immunoreactivity was detected by the Dako Liquid DAB+ Substrate Chromogen System (cat # K3468, DAKO North America, Inc., Agilent Technologies).

Epidemiological Data:

A template and code book was developed based on review of participant questionnaires from JHU and Toronto and provided to all sites. De-identified data was then sent to JHU where it was reviewed and checked prior to harmonization to create uniform definition across sites. Variables with significant missing information were not included. Exposures examined included race, Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, BRCA1/2 status, family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer, parity, breast feeding and mean duration, oral contraceptive use and mean duration, hormone therapy use, tubal ligation, hysterectomy, endometriosis, mean age at menarche in years, personal history of breast cancer, fibroids, smoking, talcum powder, and body mass index (BMI). Germ line BRCA1/2 mutation status was confirmed from written reports and all surgical procedures were confirmed from pathology reports.

Statistical Methods:

The proportions and frequencies of the three lesions and p53 signatures were calculated overall and based on location (fimbria vs. non-fimbriated tube), BRCA1/2 status and age. Risk factor associations and their p-values were calculated using descriptive statistics. The categories used were based on prior literature (20,21) and distributions of exposure in women without lesions. Direct age-standardized estimates were calculated to compare characteristics of women with and without lesions (https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/donna-spiegelman/software/table1-for-windows). A number of sensitivity analyses were undertaken with details provided in the results section. Percent agreement and Kappa were calculated for the final diagnosis reported by the first and second pathologist. All tests were considered statistically significant at P<0.05 and performed using STATA version 14.

RESULTS

Table 1 provides a summary of the tubal lesions identified in 400 high-risk women who underwent RRSO overall and by site. Of these women 92% had an identified pathogenic mutation in BRCA1/2. The combined prevalence of Invasive Cancers/ STICs /STILs was 6.3% (1.5% for invasive serous carcinomas, 3.5% for STICs and 1.3% for STILs). The prevalence among BRCA1 mutation carriers was 3% and among BRCA2 mutation carriers was 3.3%. No invasive serous cancers, STICs, or STILs were identified in the 19 high-risk women who tested negative for a pathogenic mutation in BRCA1/2. There was a significant difference in the mean age across the sites (p = 0.02). The mean age for women from JHU was 50 years (SD 8.8), MSKCC was 49 years (SD 9.2) and Toronto was 47 years (SD 7.7).

Table 1:

Summary of lesions identified in the right and left fallopian tubes of 400 high-risk women.

| Lesion | STIC alone (n=12) |

STIC + Invasive Carcinoma (n=2) |

Invasive Carcinoma alone (n=4) |

STIL (n=5) |

No Lesion (n=355) |

Total (n=400) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mean Age at time of RRSO years, (SD) |

50.9 (9.3) | 60.4 (22.9) * | 55.5 (9.7) * | 48.1 (3.1) | 47.9 (8.3) | 48.3 (8.5) |

|

Mean year of RRSO, (SD) |

2004 (3.0) | 2007 (4.9) | 2004 (4.3) | 2005 (2.4) | 2007 (3.0) | 2007 (3.0) |

| BRCA Status, n (%) | ||||||

| BRCA 1 Positive | 7 (58.3) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (25.0) | 2 (40.0) | 165 (46.5) | 188 (47.0) |

| BRCA 2 Positive | 5 (41.7) | 1 (50.0) | 3 (75.0) | 3 (60.0) | 157 (44.2) | 178 (44.5) |

| BRCA 1/2 Negative | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (5.1) | 19 (4.8) |

| BRCA status unknown | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (4.2) | 15 (3.7) |

| Site, n (%) | ||||||

| JHU (2005–2014) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 70 (19.8) | 71 (17.7) |

| MSKCC (2006–2011) | 3 (25.0) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 128 (36.3) | 134 (33.5) |

| Toronto (1996–2009) | 9 (75.0) | 1 (50.0) | 4 (100.0) | 5 (100) | 155 (43.9) | 195 (48.8) |

Table 2 compares selected age-standardized characteristics of women diagnosed with carcinoma (invasive cancer/STICs/STILs; N = 23) to those without carcinoma (N = 377). Additional characteristics are reported in Supplement 2. Older age was the only significant predictor of having a carcinoma (51.9 years vs. 48.1 years; p= 0.036), particularly among women with invasive carcinoma (p=0.009). Other risk/protective factors for HGSC including oral contraceptive (OC) use, parity, and history of hormone therapy were not found to be significantly different between women with and without invasive carcinoma/STICs/STILs (20). On average women with a carcinoma reported a lower mean duration of breast feeding (7.4 months) when compared to women with no lesion (14.5 months) but this difference was not statistically significant. These results did not change in sensitivity analyses limited to the two prospective studies (JHU and Toronto), BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, excluding women with tubal ligation or excluding women with breast cancer within the last 10 years. Risk factors associated with other epithelial ovarian cancer subtypes were also not associated with a diagnosis of carcinoma compared to no lesion.

Table 2:

Characteristics of women with and without STICs and/or invasive carcinoma in the fallopian tubes (N = 400)

| Characteristics | No STIC/STIL and/or invasive Carcinoma (n=377) n (%) |

STIC/STIL and/or invasive Carcinoma (n=23) n (%) |

P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) at RRSO, years | 48.1 (8.4) | 51.9 (9.7) | 0.04 |

| Race(a) | 0.12 | ||

| White | 345 (91.5) | 19 (83.3) | |

| Black | 15 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 16 (4.2) | 3 (12.5) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) | 1 (4.2) | |

| BRCA Status | 0.62 | ||

| BRCA 1/2 Positive | 343 (91.0) | 23 (100.0) | |

| VUS/Negative | 19 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Missing | 15 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Personal History of Breast Cancer | 0.67 | ||

| No | 211 (56.1) | 14 (62.5) | |

| Yes | 166 (43.9) | 9 (37.5) | |

|

Family History of Breast and/or Ovarian Cancer(b) |

1.00 | ||

| No | 72 (19.0) | 4 (16.7) | |

| Yes | 302 (80.2) | 19 (83.3) | |

| Missing | 3 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Parity | 1.00 | ||

| Nulliparous | 41 (10.8) | 2 (8.3) | |

| Parous | 334 (88.6) | 21 (91.7) | |

| Missing | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Breast Feeding (c) | 1.00 | ||

| No | 34 (13.8) | 2 (10.5) | |

| Yes | 165 (66.8) | 11 (57.9) | |

| Missing | 48 (19.4) | 6 (31.6) | |

|

Mean Duration of Breastfeeding, months (SD) (c) |

14.5 (13.2) | 7.4 (6.02) | 0.07 |

| Oral Contraceptive Use | 0.62 | ||

| Never | 82 (21.7) | 4 (16.7) | |

| Ever | 267 (70.9) | 19 (83.3) | |

| Missing | 28 (7.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

|

Mean Duration of Oral Contraceptive use months (SD) (c) |

9.6 (6.7) | 8.5 (2.4) | 0.58 |

| Hormone Therapy Use | 1.00 | ||

| Never | 295 (78.3) | 17 (75.0) | |

| Ever | 51 (13.5) | 3 (12.5) | |

| Missing | 31 (8.2) | 3 (12.5) | |

| Tubal Ligation | 0.55 | ||

| Never | 313 (83.1) | 18 (79.2) | |

| Ever | 54 (14.3) | 4 (16.7) | |

| Missing | 10 (2.6) | 2 (4.2) | |

| Hysterectomy(d) | 0.38 | ||

| Never | 350(92.9) | 22 (95.8) | |

| Ever | 24 (6.3) | 0(0.0) | |

| Missing | 3 (0.8) | 1 (4.2) | |

| Endometriosis | 0.33 | ||

| Never | 338 (89.7) | 18 (79.2) | |

| Ever | 19 (5.0) | 3 (12.5) | |

| Missing | 20 (5.3) | 2 (8.3) |

All values were age standardized. For groups with <10 in one category

Fisher exact test was used. Abbreviations: RRSO, risk reduction salpingo-oophorectomy; SD, standard deviation; BRCA, breast cancer susceptibility gene; VUS, variants of uncertain significance; STIC, serous tubalintraepithelial carcinoma, STIL, serous tubal intraepithelial lesion.

Other includes Hispanic, Asian/pacific islander, and those who are multiracial

Those who reported a 1st and/or 2nd degree family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer

Breast feeding limited to parous women

Collected on closest date prior to RRSO.

Table 3 provides individual level data on the prevalence of fallopian tube lesions and p53 signatures for 105 women extensively sampled in parts 2 and 3. In part 2 the mean number of fimbriae blocks were 1.7 for JHU, 2.3 for MSKCC and 2.6 for Yale. A review by multiple pathologists increased the number of invasive cancers/STICs/STILs detected by 50%. Additional tissue sampling also more than doubled the number of lesions. In total 10 carcinomas were detected in the tubes of 6 women. In only half of the cases were the STICs/STILs limited to the fimbria and in 50% of cases multiple lesions were identified. In two of the 3 individuals where a STIC was identified in the top and bottom of the same tissue block we stained and reviewed every 10th and 11th slide for H&E and laminin γ1 for 90% of the block to determine if they were independent lesions. Based on our evaluation the two STICs appear to be independent. Unlike STICs/STILs and invasive carcinomas, p53 signatures were identified across the entire tube in 10 women. Six p53 signatures were identified in the fimbria (with 5 out of 6 in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers), and 8 p53 signatures in the non-fimbriated tube.

Table 3:

Description of lesions and p53 signatures in the fallopian tube after additional sampling (n = 105)

| STIC5 in the right and left fimbria | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case ID |

Lesson | Year of RRSO |

Age | BRCA status |

Site | Position | Location | Laminin γ1 | p53 | Ki-67 | Fimbria Blocks # |

Tube Blocks # |

Path Report |

Second Reviewer Agreement |

| 1 | STIC | 2011 | 76 | BRCA2 | MSKCC | Top | Right Fimbria | Positive | Diffuse staining | <10% | 2 | 0 | STIC; p53 diffuse & Ki-67 ≥10% | Yes |

| STIC & Cancer | Bottom | Right Fimbria | Positive | Diffuse staining | <10% | |||||||||

| 2 | STIC | 2011 | 49 | BRCA1 | MSKCC | Top | Right Fimbria | Positive | Absence/non-abnormal | ≥10% | 2 | 0 | No histologic lesion | No |

| 3 | STIC | 2011 | 44 | BRCA1 | YALE | Top | Right Fimbria | Positive | Diffuse staining | ≥10% | 2 | 0 | STIC; p53 diffuse & Ki-67 ≤10% | No |

| STIC | Bottom | Right Fimbria | Positive | Diffuse staining | ≥10% | |||||||||

| STIC5 in the non-fimbrial sections of the right and left tube and p53 signatures/STIL5 in the right and left tube | ||||||||||||||

|

Case ID |

Lesson |

Year of RRSO |

Age |

BRCA status |

Site | Position | Location | Laminin γ1 | p53 | Ki-67 |

Fimbria Blocks # |

Tube Blocks # |

Path Report |

Second Reviewer Agreement |

| 1 | STIC | 2012 | 47 | BRCA2 | JHU | Top | Left Distal | Positive | Diffuse | <10% | 1 | 7 | No lession | NO |

| STIC + p53 signature | Bottom | Left Distal | Positive | Diffuse | <10% | |||||||||

| p53 signature | Top | Right Proximal | Negative | Diffuse | <10% | |||||||||

| p53 signature | Top | Right Proximal | Negative | Diffuse | <10% | |||||||||

| 2 | STIL p53 signature |

2010 | 50 | BRCA2 | JHU | Bottom Bottom |

Left Distal Left Fimbria |

Negative Negative |

Diffuse Diffuse |

<10% <10% |

2 | 4 | No lession | NO |

| 3 | STIC | 2011 | 57 | BRCA2 | JHU | Bottom | Left Distal | Positive | Diffuse | <10% | 2 | 4 | No lession | NO |

| p53 signature | Bottom | Right Fimbria | Negative | Diffuse | <10% | |||||||||

| 4 | p53 signature p53 signature |

2012 | 47 | Negative | JHU | Top Bottom |

Right Distal Left Proximal |

Negative Negative |

Diffuse Diffuse |

<10% <10% |

0 | 6 | No lession | NO |

| 5 | p53 signature p53 signature |

2012 | 49 | BRCA1 | JHU | Top Bottom |

Right Fimbria Right Distal |

Negative Negative |

Diffuse Diffuse |

<10% <10% |

2 | 4 | No lession | NO |

| 6 | p53 signature | 2012 | 40 | BRCA2 | JHU | Bottom | Right Distal | Negative | Diffuse | <10% | 2 | 8 | No lession | NO |

| 7 | p53 signature | 2012 | 59 | BRCA2 | JHU | Bottom | Right Fimbria | Negative | Diffuse | <10% | 2 | 2 | No lession | NO |

| 8 | p53 signature | 2013 | 43 | BRCA1 | JHU | Bottom | Left Proximal | Negative | Diffuse | <10% | 1 | 6 | No lession | NO |

| 9 | p53 signature | 2010 | 41 | BRCA2 | JHU | Top | Right Fimbria | Negative | Diffuse | <10% | 2 | 6 | No lession | NO |

| 10 | p53 signature | 2010 | 68 | Negative | JHU | Top | Left Fimbria | Negative | Diffuse | <10% | 6 | 3 | No lession | NO |

Abbreviations: STIC, serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma; RRSO, risk reduction salpingo-oophorectomy; BRCA, breast cancer susceptibility gene; MSKCC, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; STIL, serous tubal intraepithelial lesion; JHU, Johns Hopkins University

Clinical characteristics of the 105 women are described in Supplement 3. The mean age of women with p53 signatures in the fimbria was significantly older when compared to women with signatures in the remainder of the tube (54 years versus 45 years, p = 0.03). Of note, invasive carcinoma/STICs/STILs were only detected in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers while p53 signatures were detected irrespective of mutation status. Figure 3 provides a summary of the prevalence of unique types of lesions per individual for each part of the study. The combined prevalence of invasive cancer/STICs/STILs for part 1 and part 2 was 6.3% and 11.9% respectively after extensive sampling and review by multiple pathologists and 27% for unique p53 signatures from part 2.

Figure 3:

Detection of Fallopian Tube Lesions. A summary of the type of and frequency of unique lesions detected in the fallopian tubes after comprehensive sampling and additional sampling and pathology review.

The percent agreement for the diagnosis of STIC versus non- STIC by the two initial pathologists was 99.3% and the Kappa = 0.61 based on laminin γ1 expression and H&E. The percent agreement for the diagnosis of p53 signature based on H&E, laminin γ1, p53 and Ki-67 was 96.9% and the Kappa = 0.19. Every case of p53 signature required at least a 3rd pathology review and sometimes a 4th to reach consensus.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first multicenter study to extensively examine for risk and/or protective factors associated with STICs/STILs in women at high-risk for ovarian cancer. This is also the first study to conduct sampling of both ends of tumor blocks across the entire tube and have all slides reviewed by multiple pathologists to further characterize the prevalence and location of STICs/STILs and p53 signatures. Comprehensive sampling and screening of the fallopian tube in 400 RRSO cases based on H&E and p53 expression identified invasive serous cancers/STICs/STILs in 6.3% of cases. Older age was associated with having a carcinoma. No other risk/protective factors were significantly associated with Invasive Carcinoma/STICs/STILs. The observation that mean breast feeding was on average 7 months lower in cases with a carcinoma than no lesion deserves further exploration. There has been only one single institution study that has examined for risk factors associated with STICs (22). Vicus et al. observed in 173 BRCA1/2 mutation carriers that older age, tubal ligation and a BMI > 25 kg/m2 were positively associated with STICs and that there was an inverse relationship with increased duration of oral contraceptive use. Some of these women are part of our study. In BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, breast feeding and duration of oral contraceptive use, were associated with between 25% and 40% reduction in ovarian cancer incidence. It is plausible that the association between breast feeding, oral contraceptives and STICs/STILs is not as strong (21) or that known risk/protective factors (21) are associated with progression of STICs to HGSC and not the incidence of STICs. Another possibility is that the development of STICs are related to random mutations occurring by chance that target cancer drivers including TP53 (23).

Additional sampling of the fallopian tube generated some interesting findings. It doubled the detection of STICs/STILs and p53 signatures. The observation that STICs/STILs occur at equal prevalence in the non-fimbriated part of the tube raises the question of whether all STICs have the same propensity to translocate to the ovary or peritoneum. Similarly the observation of multiple STICs in 50% of cases could be indicative of greater risk for STIC migration to occur to the ovary or peritoneum and therefore the development of HGSC when compared to a woman with a single lesion. The role of p53 signatures in the development of HGSC is less clear. P53 signatures occurred at a greater prevalence than STICs (27% versus 11.9%) with only 40% occurring in the fimbria. Further, signatures in the fimbria compared to the remaining tube were more prevalent among older age women suggesting that all p53 signatures may not necessarily lead to HGSC. The increase in the number of detected lesions and p53 signatures after review by multiple pathologists and the low agreement across pathologists particularly for p53 signatures suggests that further work is needed for the development of standard reproducible criteria. It is likely that the imbalance caused by few positive lesions and significant discordance between pathologists is only part of the explanation for the low agreement (24).

Our prevalence of STICs/STILs based on comprehensive processing was 4.8% which is within the range of 2.0% to 6.2% reported by the few studies of more than 200 high-risk women (3, 25–27). Shaw et al. is the only study to report on STICs/STILs and p53 signatures in 176 high-risk women and the tissue processing was similar to what we did for the initial 400 cases. The prevalence of STICs/STILs were much higher than in our study at 10% while the prevalence of p53 signatures was lower at 11% (28 ). Our estimates of invasive cancer was 1.5%. This estimate is lower than the GOG-0199, a screening study that reported a prevalence of 3.4% after review of 966 RRSO cases but similar to three large (N > 200) observational studies which reported a prevalence ranging between 0.9% and 2.0% (25–27, 29). None of the studies did more extensive sampling. The few pilot studies that have examined the impact of deeper sectioning of tissue blocks on the detection of STICs/STILs from the fimbria in cases with cancer (13, 30, 31) have shown an increase in detection of tubal lesions. None of them have performed extensive sectioning across the entire tube in cancer-free individuals.

Strengths of this study include the multicenter design, standardized tissue processing across sites, review of slides with and without lesions by multiple gynecologic pathologists and the ability to link pathology tissue to detailed epidemiological data. In this study, we had adequate power to detect moderate to large differences in exposures between women with and without a lesion. The widespread implementation of standard pathological criteria across hospitals in conjunction with the prospective collection of epidemiological data may help elucidate novel risk/protective factors associated with fallopian tube lesions and better understand their natural history.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Sophia HL George, Ramlogan Sowamber, Noor Salman for retrieval and processing of Toronto Cases (University Health Network, Toronto).

Staff and participants of the BOSS cohort at Johns Hopkins.

FUNDING:

DOD Ovarian Consortium W81XWH-11-2-0230

Breast Cancer Research Foundation (KV)

Richard W. TeLinde Research Fund (I-M S)

NCI P30CA06973 (RS)

NCI P30 CA008748 (KV,I-M S,RK,T-L W)

Footnotes

No conflicts of interest related to the work in this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zweemer RP, van Diest PJ, Verheijen RH, Ryan A, Gille JJ, Sijmons RH, et al. Molecular evidence linking primary cancer of the fallopian tube to BRCA1 germline mutations. Gynecol Oncol 2000;76(1):45–50 doi 10.1006/gyno.1999.5623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cass I, Holschneider C, Datta N, Barbuto D, Walts AE, Karlan BY. BRCA-mutation-associated fallopian tube carcinoma: a distinct clinical phenotype? Obstet Gynecol 2005;106(6):1327–34 doi 10.1097/01.AOG.0000187892.78392.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powell CB, Swisher EM, Cass I, McLennan J, Norquist B, Garcia RL, et al. Long term follow up of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers with unsuspected neoplasia identified at risk reducing salpingo-oophorectomy. Gynecol Oncol 2013;129(2):364–71 doi 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vang R, Visvanathan K, Gross A, Maambo E, Gupta M, Kuhn E, et al. Validation of an algorithm for the diagnosis of serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2012;31(3):243–53 doi 10.1097/PGP.0b013e31823b8831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Visvanathan K, Vang R, Shaw P, Gross A, Soslow R, Parkash V, et al. Diagnosis of serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma based on morphologic and immunohistochemical features: a reproducibility study. Am J Surg Pathol 2011;35(12):1766–75 doi 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31822f58bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee Y, Miron A, Drapkin R, Nucci MR, Medeiros F, Saleemuddin A, et al. A candidate precursor to serous carcinoma that originates in the distal fallopian tube. J Pathol 2007;211(1):26–35 doi 10.1002/path.2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kindelberger DW, Lee Y, Miron A, Hirsch MS, Feltmate C, Medeiros F, et al. Intraepithelial carcinoma of the fimbria and pelvic serous carcinoma: Evidence for a causal relationship. Am J Surg Pathol 2007;31(2):161–9 doi 10.1097/01.pas.0000213335.40358.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sehdev AS, Kurman RJ, Kuhn E, Shih Ie M. Serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma upregulates markers associated with high-grade serous carcinomas including Rsf-1 (HBXAP), cyclin E and fatty acid synthase. Mod Pathol 2010;23(6):844–55 doi 10.1038/modpathol.2010.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarboe E, Folkins A, Nucci MR, Kindelberger D, Drapkin R, Miron A, et al. Serous carcinogenesis in the fallopian tube: a descriptive classification. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2008;27(1):1–9 doi 10.1097/pgp.0b013e31814b191f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salvador S, Rempel A, Soslow RA, Gilks B, Huntsman D, Miller D. Chromosomal instability in fallopian tube precursor lesions of serous carcinoma and frequent monoclonality of synchronous ovarian and fallopian tube mucosal serous carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2008;110(3):408–17 doi 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuhn E, Kurman RJ, Vang R, Sehdev AS, Han G, Soslow R, et al. TP53 mutations in serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma and concurrent pelvic high-grade serous carcinoma--evidence supporting the clonal relationship of the two lesions. J Pathol 2012;226(3):421–6 doi 10.1002/path.3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Novak M, Lester J, Karst AM, Parkash V, Hirsch MS, Crum CP, et al. Stathmin 1 and p16(INK4A) are sensitive adjunct biomarkers for serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2015;139(1):104–11 doi 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.07.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Przybycin CG, Kurman RJ, Ronnett BM, Shih Ie M, Vang R. Are all pelvic (nonuterine) serous carcinomas of tubal origin? Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34(10):1407–16 doi 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181ef7b16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carlson JW, Miron A, Jarboe EA, Parast MM, Hirsch MS, Lee Y, et al. Serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma: its potential role in primary peritoneal serous carcinoma and serous cancer prevention. J Clin Oncol 2008;26(25):4160–5 doi 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.4814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuhn E, Meeker AK, Visvanathan K, Gross AL, Wang TL, Kurman RJ, et al. Telomere length in different histologic types of ovarian carcinoma with emphasis on clear cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol 2011;24(8):1139–45 doi 10.1038/modpathol.2011.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuhn E, Meeker A, Wang TL, Sehdev AS, Kurman RJ, Shih Ie M. Shortened telomeres in serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma: an early event in ovarian high-grade serous carcinogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34(6):829–36 doi 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181dcede7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medeiros F, Muto MG, Lee Y, Elvin JA, Callahan MJ, Feltmate C, et al. The tubal fimbria is a preferred site for early adenocarcinoma in women with familial ovarian cancer syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol 2006;30(2):230–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gross AL, May BJ, Axilbund JE, Armstrong DK, Roden RB, Visvanathan K. Weight change in breast cancer survivors compared to cancer-free women: a prospective study in women at familial risk of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2015;24(8):1262–9 doi 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuhn E, Kurman RJ, Soslow RA, Han G, Sehdev AS, Morin PJ, et al. The diagnostic and biological implications of laminin expression in serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2012;36(12):1826–34 doi 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31825ec07a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wentzensen N, Poole EM, Trabert B, White E, Arslan AA, Patel AV, et al. Ovarian Cancer Risk Factors by Histologic Subtype: An Analysis From the Ovarian Cancer Cohort Consortium. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(24):2888–98 doi 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.8178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kotsopoulos J, Lubinski J, Gronwald J, Cybulski C, Demsky R, Neuhausen SL, et al. Factors influencing ovulation and the risk of ovarian cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Int J Cancer 2015;137(5):1136–46 doi 10.1002/ijc.29386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vicus D, Finch A, Rosen B, Fan I, Bradley L, Cass I, et al. Risk factors for carcinoma of the fallopian tube in women with and without a germline BRCA mutation. Gynecol Oncol 2010;118(2):155–9 doi 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tomasetti C, Vogelstein B. Cancer etiology. Variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions. Science 2015;347(6217):78–81 doi 10.1126/science.1260825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feinstein AR, Cicchetti DV. High agreement but low kappa: I. The problems of two paradoxes. J Clin Epidemiol 1990;43(6):543–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mingels MJ, Roelofsen T, van der Laak JA, de Hullu JA, van Ham MA, Massuger LF, et al. Tubal epithelial lesions in salpingo-oophorectomy specimens of BRCA-mutation carriers and controls. Gynecol Oncol 2012;127(1):88–93 doi 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wethington SL, Park KJ, Soslow RA, Kauff ND, Brown CL, Dao F, et al. Clinical outcome of isolated serous tubal intraepithelial carcinomas (STIC). Int J Gynecol Cancer 2013;23(9):1603–11 doi 10.1097/IGC.0b013e3182a80ac8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zakhour M, Danovitch Y, Lester J, Rimel BJ, Walsh CS, Li AJ, et al. Occult and subsequent cancer incidence following risk-reducing surgery in BRCA mutation carriers. Gynecol Oncol 2016;143(2):231–5 doi 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.08.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaw PA, Rouzbahman M, Pizer ES, Pintilie M, Begley H. Candidate serous cancer precursors in fallopian tube epithelium of BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Mod Pathol 2009;22(9):1133–8 doi 10.1038/modpathol.2009.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finch A, Beiner M, Lubinski J, Lynch HT, Moller P, Rosen B, et al. Salpingo-oophorectomy and the risk of ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal cancers in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 Mutation. JAMA 2006;296(2):185–92 doi 10.1001/jama.296.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahe E, Tang S, Deb P, Sur M, Lytwyn A, Daya D. Do deeper sections increase the frequency of detection of serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (STIC) in the “sectioning and extensively examining the FIMbriated end” (SEE-FIM) protocol? Int J Gynecol Pathol 2013;32(4):353–7 doi 10.1097/PGP.0b013e318264ae09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mehra KK, Chang MC, Folkins AK, Raho CJ, Lima JF, Yuan L, et al. The impact of tissue block sampling on the detection of p53 signatures in fallopian tubes from women with BRCA 1 or 2 mutations (BRCA+) and controls. Mod Pathol 2011;24(1):152–6 doi 10.1038/modpathol.2010.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.