Abstract

The SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence) guidelines were published in 2015 to increase the completeness, precision, and transparency of published reports about efforts to improve the safety, value, and quality of health care. The principles and methods applied in work to improve health care are often applied in educational improvement as well. In 2016, a group was convened to develop an extension to SQUIRE that would meet the needs of the education community. This article describes the development of the SQUIRE-EDU extension over a three-year period and its key components. SQUIRE-EDU was developed using an international, interprofessional advisory group and face-to-face meeting to draft initial guidelines; pilot testing of a draft version with nine authors; and further revisions from the advisory panel with a public comment period. SQUIRE-EDU emphasizes three key components that define what is necessary in systematic efforts to improve the quality and value of health professions education. These are a description of the local educational gap; consideration of the impacts of educational improvement to patients, families, communities, and the health care system; and the fidelity of the iterations of the intervention. SQUIRE-EDU is intended for the many and complex range of methods used to improve education and education systems. These guidelines are projected to increase and standardize the sharing and spread of iterative innovations that have the potential to advance pedagogy and occur in specific contexts in health professions education.

In the past decade, publication guidelines have been developed for the many methods of scientific inquiry, the goal being to improve the transparency and completeness of published reports.1 Such reporting structures enable authors, reviewers, editors, and readers to focus on the content of the information exchange, knowing that studies follow well-established guidelines considered critical for scholarly reporting. Reports of scholarly health care improvement work became standardized in 2008 with the initial publication of the Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE)2 guidelines, and these have been superseded by revised guidelines (SQUIRE 2.0) in 2015.3 Here, we describe the developmental process for and introduce SQUIRE-EDU, an extension of the SQUIRE guidelines, applicable for reporting work done to improve health professions education.

Health professions education is a dynamic area where continuous educational improvement is a source for building knowledge. Reporting of such changes in health professions education is often done using the frameworks associated with hypothesis-generating and testing approaches, ranging from case studies to randomized controlled trials.4 Using testing methods is appropriate to answer certain questions, but the improvement that occurs in local educational settings requires, and often uses, an explanatory approach that encourages broader evaluations of the context and lessons learned. Not sharing these approaches in a systematic way can limit the learning from and spread of the work and lead to redundancy as educators repeatedly “reinvent the wheel.”

Many health professions educators use systematic methods to assess, change, and improve their educational curricula and systems. These improvements often follow change cycles that are similar to improvement methodology: having a clear aim, understanding the processes, creating an intervention, assessing the intervention’s success, and modifying it for the next cycle.5 We refer to this work as “educational improvement,” which often focuses on the local needs and problems where the intervention occurred but also generates lessons that can be extrapolated to educational improvement in similar contexts.

Using the SQUIRE 2.0 guidelines as a foundation, we developed, tested, and revised the SQUIRE-EDU extension to increase the completeness, transparency, and replicability of reports that describe systematic efforts to improve the quality and value of health professions education.

Development and Testing of the Guidelines

Between February 2016 and January 2018, a five-person interprofessional leadership team (G.O., G.E.A., M.A.D., M.K.S., L.D.) guided a three-phase process to recruit an advisory group, test a draft version of SQUIRE-EDU, and sharpen the final version of the SQUIRE-EDU extension.

Phase one

The first phase focused on identifying an advisory group within health professions education from education and improvement thought leaders. The group consisted of 27 members representing medicine, nursing, pharmacy, education, and journal editors from the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. As a starting point, advisory group participants identified example articles that could be used to isolate key elements for inclusion as candidate items in SQUIRE-EDU. The advisory group contributed to the drafting and editing of potential items through an iterative process facilitated through asynchronous group communication (to an email mailgroup) punctuated by four conference calls. The feedback and input from the advisory group conference calls were used to create the first five versions (0.1 through 0.5) of SQUIRE-EDU.

At a one-day in-person developmental meeting in Orlando, Florida, in December 2016, the advisory group and leadership team members split into small groups, discussed example articles, and modified candidate concepts and items using SQUIRE-EDU 0.6. Next, in groups of five to six members, the candidate concepts for each section of an article were explored—introduction, methods, results, and discussion. This process clarified the intention and definition of the emerging concepts and items. After the development meeting, the SQUIRE-EDU leadership team collated and distilled the findings from the development meeting into SQUIRE-EDU 0.7. The advisory group subsequently provided comments, which guided the development of version 0.8.

Phase two

The second phase focused on testing SQUIRE-EDU 0.8 using a unique process for end user testing that was created for the development of SQUIRE 2.0.6 We issued invitations to participate to the advisory group members with instructions to extend the invitation to colleagues, fellows, and learners who might be interested in participating. Nine individuals volunteered to participate in this project, which was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of Dartmouth College (the home institution of authors G.O. and L.D.).

We asked participants to complete two tasks within two months. First, they were to use SQUIRE-EDU 0.8 to write a manuscript they were working on, or to rewrite one they had recently finished. With this writing or editing, they were asked to annotate sections of their manuscript, using the “Track Changes” function of Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington) to show which SQUIRE-EDU 0.8 items they had used and to which text the item applied. Second, they completed a confidential survey about their item usage and their interpretation of key concepts in the SQUIRE-EDU 0.8 guidelines.

We collected the survey data and manuscripts electronically using Qualtrics Survey Software (Qualtrics, LLC, Provo, Utah). The survey contained open-ended items on key concepts and potential areas of controversy in SQUIRE-EDU as well as Likert scaled questions to assess comfort with item usage. Quantitative data from the survey were transferred into Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington), and descriptive statistics were interpreted in the context of the item usage in the manuscripts and the qualitative data from the open-ended questions. We evaluated SQUIRE-EDU items 3, 5, 7, 8, 9, and 14–17 (described below) for concordance between the item usage as identified by the respondent and the intended application of the item as defined by the advisory group. Finally, we determined the SQUIRE-EDU core concepts that emerged in the papers. These data guided our work in further refining the SQUIRE-EDU items for version 0.9.

Phase three

In the third phase, we shared version 0.9 with the advisory group for additional feedback and also posted it on the SQUIRE website7 for public comment for two months. Email invitations for public review were extended to the more than 500 individuals who are registered on the SQUIRE website. We also posted an invitation to review version 0.9 on the Quality and Safety Education for Nurses website.8 We received about 40 comments during this third phase, which we used to create the final version, SQUIRE-EDU 1.0.

SQUIRE-EDU Guidelines

About SQUIRE-EDU

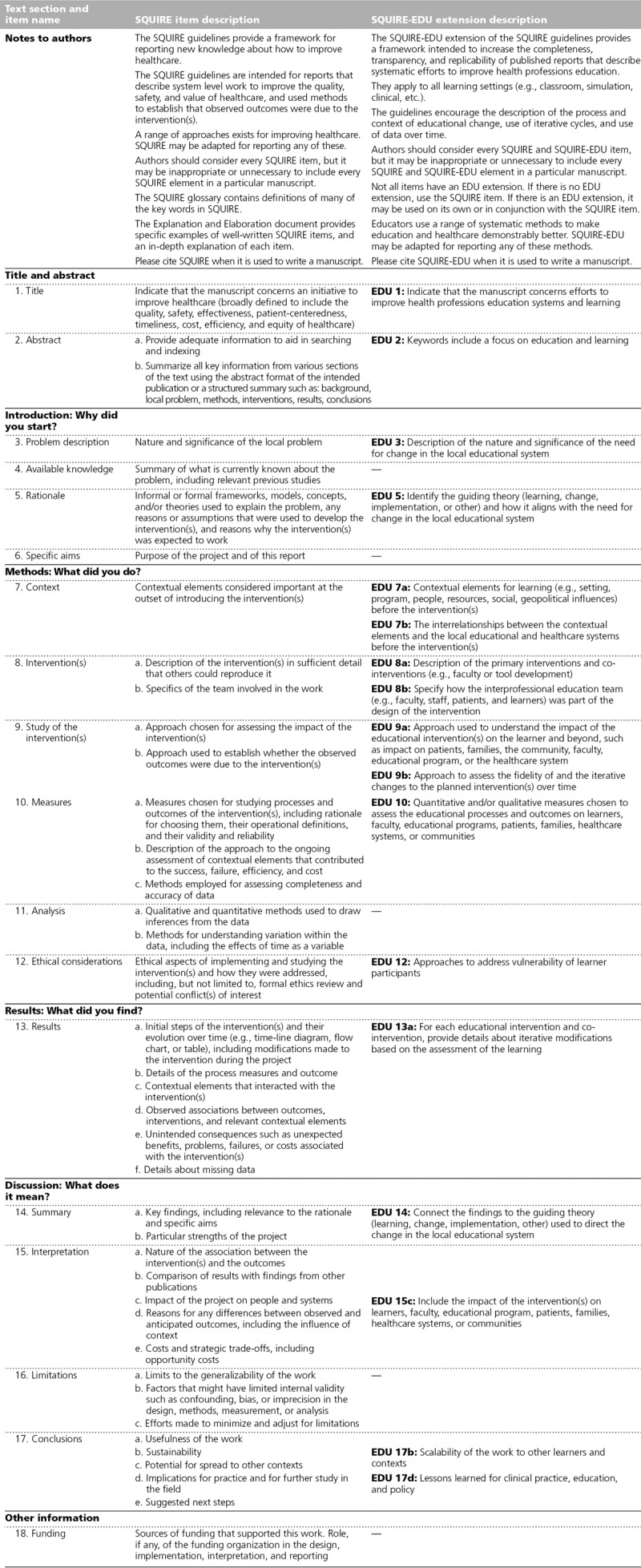

Three core concepts emerged in the development of SQUIRE-EDU (Table 1). First, authors should describe the local educational gap (EDU 3). This description is a vital step as the current functions of the local educational system are compared with the intended future state. For educational improvement, this step requires a clear description of why the improvement was initiated at the site at that point in time.

Table 1.

Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence in Education: SQUIRE-EDU

Second, it is important to consider how the educational improvement affects stakeholders beyond the learners and the learning (EDU 7b, 9a, 10, 15c). Early in phase one, the advisory group expressed clear expectations that health professions education should be deliberate in articulating how educational improvement affects not just learners, faculty, or the educational program but also patients, families, health care systems, communities, or the delivery of care. The latter elements are normally considered distal to educators, but a key goal of SQUIRE-EDU was to create explicit connections between curricula and these elements. SQUIRE-EDU recognizes that such connections may be difficult to establish, but the ultimate goal of health professions education should be to improve the health care system and the health of patients, families, and communities. Thus, efforts to report the improvement and potential impact of educational programs should include these elements.

Third, describing the fidelity of the iterative changes surfaced as an important point of emphasis (EDU 9b, 13a). In research, fidelity is defined as the extent to which an intervention adheres to the planned protocol for that intervention. In improvement work, the intervention is expected to be modified through each cycle of change as the team gains insight into what works, for whom, and in what context. Thus, fidelity specific to SQUIRE-EDU has two components. It refers to the adherence of the intervention to the planned protocol within each cycle of change and to the faithful use of data to inform the next cycle of change, thus ensuring that changes are driven by the findings of the previous iteration.

A combination of quantitative and qualitative data (EDU 10) can often help assess the fidelity, which requires record keeping not just of results but also of the reasoning for changes based on more nuanced observations. Educational improvement is a process of social change within complex systems, and this reporting of how the intervention changes over time provides important contextual knowledge. Simply reporting before-and-after data about course evaluations or exam scores is not enough because readers should know exactly how and why each iteration of the intervention was executed to determine whether and how they might implement similar changes in their local context.

How to use SQUIRE-EDU

SQUIRE-EDU consists of extensions to 13 of the 18 SQUIRE 2.0 items3 (with corresponding numbering). Like SQUIRE, SQUIRE-EDU authors are requested to include a clear rationale and theory (EDU 5 and 14), description of the context of where the work occurred (EDU 7a and 7b), and plan for studying the interventions (EDU 9a and 9b). If there is no EDU extension item (SQUIRE 4, 6, 11, 16, 18), the author should consult the SQUIRE item. If there is an EDU extension, it may be used on its own or in conjunction with the SQUIRE item. Authors should consider every SQUIRE item (Table 1, middle column) and every SQUIRE-EDU item (Table 1, righthand column), but it may be inappropriate or unnecessary to include every SQUIRE and SQUIRE-EDU item in a specific manuscript.

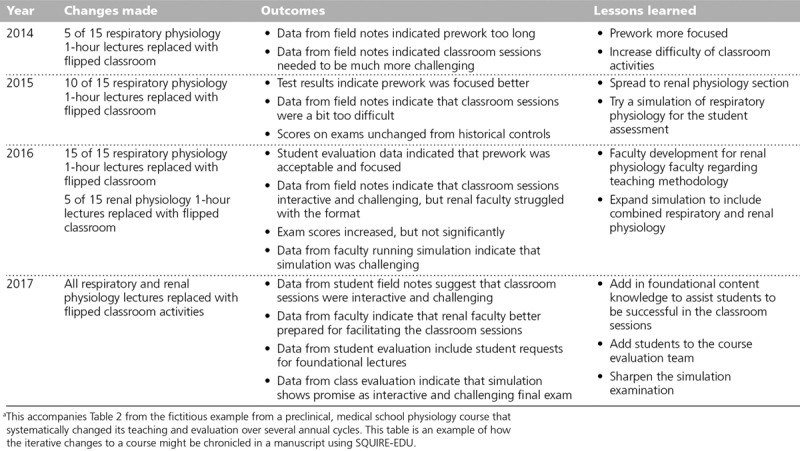

Each of the SQUIRE-EDU items is presented below with brief comments about what was learned in the development and testing phases. Pilot testing in phase two demonstrated which items engendered differing interpretations and which were unfamiliar. These data informed the explanations below. Additionally, Tables 2 and 3 provide a detailed example about how each SQUIRE-EDU item might be written in a manuscript, along with comments about the example.

Table 2.

Example and Explanation of Each SQUIRE-EDU (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence in Education) Itema

Table 3.

Example of Iterative Changes to a Physiology Course, 2014–2017, Using SQUIRE-EDU (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence in Education)a

Notes to authors.

These guidelines are intended to apply to educational improvement that use iterative cycles to test interventions. The guidelines do not prescribe a particular design and may be applied to the many ways educational improvement work is done.

Title and abstract. EDU 1 and EDU 2.

The manuscript should be easy to locate using conventional scholarly literature search strategies—thus the requirement that the title, abstract, and key words specify the educational improvement methodology and note the educational focus.

Problem description. EDU 3.

Educational improvement explicitly focuses on the local need for the work (e.g., Nursing School A has a decreasing national board pass rate). In educational improvement, there should be a clear connection between the local need and the broader considerations outside the local institution. Educational improvement is focused on addressing a specific problem in the local setting. EDU 3 focuses on showing a clear indication of why the described change was needed at the identified locale.

Rationale. EDU 5.

A clear rationale, or theory, has historically not been used in improvement work. Davidoff and colleagues9(p228) describe the need for theory to guide improvement work as follows: “Personal intuition is often biased … formal theory enables maximum exploitation of learning and accumulation of knowledge, and promotes the transfer of learning from one project, one context, one challenge, to the next.” The theory used in educational improvement addresses why the planned intervention would be effective for the specific context at the identified site at that point in time. The rationale for educational improvement may be a straightforward cause–effect statement or a more complex driver diagram showing the anticipated primary and secondary drivers leading to the desired outcome. Formal or informal theory is acceptable, but the key is to make the theory explicit in the planning, the work, and the writing.

For educational improvement work, authors may also, or alternatively, incorporate formal learning theory. Learning theories identify the underlying assumptions about mechanisms of learning and interaction of the learners with the content and context. SQUIRE-EDU strongly encourages the use of a rationale or theory before the educational improvement work begins.

Context. EDU 7a and 7b.

Context is broader than setting because it encompasses an ecological sense and interacts with interventions over time. The EDU items focusing on context recommend identifying the initial contextual elements and relationships that exist. The evolution of these elements over time affects the interventions and the overall educational improvement. SQUIRE and SQUIRE-EDU account for these shifts by including context in subsequent items (SQUIRE: 10a, 13a, 17c; SQUIRE-EDU: 17b). The dynamic relationships between contextual factors mean that the perceptions of the context may shift over time. This shift is to be expected as context is created, manipulated, and controlled by the way the elements are perceived.10

There is no formal instrument or survey to describe the context. Several excellent frameworks exist to support clinical quality improvement work (e.g., MUSIQ,11 PARiHS,12 and CFIR13). A common theme among these frameworks is consideration of internal elements (e.g., faculty, staff, classroom space, champions, quality improvement training), external elements (e.g., accreditation, mandate from the dean), and characteristics of the individuals (e.g., readiness for change). Context must be assessed at the outset and at regular intervals to determine how the elements have evolved, how the perception of these have changed, and how these changes have affected the intervention and outcomes.

Any educational improvement has a wide variety of contextual elements, but authors must decide which are most important. These choices begin with the planning and development of the work and assessing which elements had an impact on the intervention over time. When preparing the manuscript, the authors know the conclusions of the work, so they should take the outcomes into account when describing the context.

Intervention(s). EDU 8a and 8b.

Describe the interventions in sufficient detail (or offer additional detail in an appendix or online) so that others can attempt to replicate. In both clinical and educational improvement, it is expected that the intervention will change over time, so descriptions of the initial intervention provide an important baseline for understanding the modification of the intervention over time. SQUIRE-EDU strongly encourages an interprofessional team to design, assess, and implement interventions (e.g., learning specialist, physician, nurses, respiratory therapist) because education and health care are naturally collaborative undertakings.

Study of the intervention(s). EDU 9a and 9b.

Beyond making changes to improve systems, scholarly work intended for peer-reviewed journals should include a study of the intervention(s). Studying the intervention allows the team to determine whether the system improved because of the intervention(s) or for some other reason, assess for unintended consequences, and determine the associated opportunity costs. This might range from using a specific design to introduce an intervention over time (e.g., step-wedge) or enacting detailed reflection and careful note-taking about the improvement process. Carefully studying the intervention also helps maintain the fidelity of each cycle of change with a clear description. Unlike some research designs where the intervention is intended to remain static over time, interventions in improvement are intended to change; however, implementation of such interventions should not be haphazard. The fidelity of each cycle of change should be reported to explain how the intervention evolved, why certain aspects of the intervention were sustained and others were not, and how and why the final version of the intervention was decided upon.

Measures. EDU 10.

When deciding what to measure, it is often helpful to use a framework, such as the Barr-Kirkpatrick hierarchy of educational outcomes.14 This framework enables a team to consider broadly what needs to be measured to determine whether the changes made to the learning experience result in an improvement. In educational studies, common outcomes include learner reactions, knowledge, skills, and attitudes. Well-done educational improvement must use the higher levels of the framework—namely, behavioral change, organizational change in practice, and benefits to patients.14 The measures will depend on the nature of the initiative, time frame of the improvement, data availability, feasibility, and resources. The higher-level outcomes offer the opportunity to connect educational processes to potential outcomes for patients, families, and communities. At the outset, the team should identify how their educational improvement will affect these stakeholders, even when the impact seems distal to the educational experience.

Ethical considerations. EDU 12.

Learners are a vulnerable population and require protection through approval or exemption of the study by the appropriate institutional ethics review committee, especially addressing the perception of coercion. At many institutions, clinical improvement does not require human subjects IRB approval because it is considered more closely aligned to the clinician–patient therapeutic relationship than to research activities.15 Local IRB practices may vary for educational interventions. SQUIRE-EDU recommends that curricular changes undertaken with improvement methodology be discussed with the local IRB to ensure appropriate oversight for learners, patients, and communities.

Results. EDU 13a.

This item details the inclusion of process and outcomes, context evaluation, interactions, and unintended consequences. EDU 13a emphasizes providing details about the important iterations that occurred. Rather than describing only the final iteration of the educational experience, disclosing details of the successes and failures of changes over time is extremely useful. These descriptions provide information that may guide the educational improvement work of others. Chronicling the iterative changes, whether weekly or yearly, allows readers to determine what occurred, when, and for what reasons. Consider summarizing these in a table, figure, or appendix to the manuscript.

Summary. EDU 14.

After the teaching team has implemented the interventions through multiple cycles of change and assessed the context and outcomes, the accompanying manuscript should comment on the impact of the rationale and guiding theory and how it might be modified for future educational improvement. This section can be a quick reminder of the rationale and theory from EDU 5 with a reflection about why and how the results showed what they did.

Interpretation. EDU 15c.

This section should discuss the impact on the learners, the sustainability of changes within the educational and health care systems, or the impact the educational changes had on health care providers. When measures are designed to assess the impact beyond the immediate learners, the breadth of interpretation of impact will be easier to analyze. Not every project will have a direct and measurable impact on elements external to the educational experience, but SQUIRE-EDU urges educators to consider the impact beyond the classroom.

Conclusions. EDU 17b and 17d.

Because SQUIRE-EDU is focused on improving the local educational system, extrapolation to other contexts may seem more challenging than with context-controlled studies. This EDU item is for describing whether and how the intervention might need to be modified to be implemented in other contexts.

Discussion

SQUIRE-EDU is an extension to the SQUIRE 2.0 publication guidelines, intended to guide the preparation of manuscripts that describe iterative cycles of improvement in health professions education. SQUIRE-EDU encourages expansion of educational science by offering an alternative to using a research design. SQUIRE-EDU incorporates rigorous methods from improvement science, which tests multiple hypotheses and interventions over time and includes a deeper integration of the influence of the local context. This alternative approach leads to discovery that broadens the limitations of traditional research. SQUIRE-EDU can also be useful to assist the design of proposed interventions, the conduct of the work, and the analysis and dissemination of educational innovations. For example, using the SQUIRE-EDU elements in planning educational improvement work facilitates a comprehensive approach to creating and evaluating innovative educational approaches. SQUIRE-EDU may also be used during the peer review process for manuscripts by providing an agreed-upon set of elements for educational improvement reports. SQUIRE-EDU strives to enhance the alignment between health professions education and clinical care through the inclusion of learning outcomes and potential or real impact on the health care system, patients, families, and communities. Finally, the guidelines can increase the uptake and scalability of educational innovations. Standardized reporting will decrease the variation in published educational improvements and enhance the ability of systematic reviews to highlight the strategies and contextual factors that result in high-quality health professions education.

SQUIRE-EDU is different from the recently published educational intervention guidelines called the Guideline for Reporting Evidence-based practice Educational interventions and Teaching (GREET).16 The GREET guidelines apply to educational interventions for teaching the knowledge and skills of evidence-based practice. In contrast, the purpose of SQUIRE-EDU is to report a process of iterative improvement in health professions education and does not limit its application to any one content area or approach. For these reasons, SQUIRE-EDU provides a unique contribution to the standardization of educational improvement reporting. This broader scope is complementary to the GREET guidelines, and both can advance health professions education.

Applying improvement methods to health professions education might be new to health care educators; however, using improvement science methods has already been embraced by K–12 educators. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching has led a movement to improve K–12 education by encouraging and using improvement methods.17 The Carnegie approach identifies educational gaps; attends to context; develops educational innovation informed by stakeholders; and then tests, adapts, and scales up promising interventions. The six core principles of improvement in the Carnegie approach mirror quality improvement principles.17 SQUIRE-EDU provides health professions educators an opportunity to learn, apply, and report their educational improvement work in a way that aligns with Carnegie’s leadership in this area.

If health professions educators want to demonstrate how education has an impact on clinical care and systems, then SQUIRE-EDU may provide opportunities for the design and methods to make these connections. This is a paradigm shift for many health professions educators. Health professions education is unique because of its complex clinical learning environments that demand critical, systems, emotional, and design thinking.18 SQUIRE-EDU encourages innovative approaches to health professions education by emboldening educators not only to improve learner outcomes but also to assess the impact of educational interventions on patient, health care system, and community outcomes. When looking to improve an educational experience, a novice teacher may ask, “How am I doing?” and a more seasoned one may inquire, “How are my students doing?” SQUIRE-EDU urges the health professions educator to inquire, “How are our patients, health care systems, and communities doing?”

Just as the SQUIRE guidelines standardized the reporting of efforts to improve health care, we anticipate that SQUIRE-EDU will have a similar contribution to health professions education. SQUIRE-EDU encourages expansion of educational science by incorporating rigorous methods from the emerging field of improvement science. The improvement science approach tests multiple hypotheses and interventions and includes a deep understanding of the influence of the local context, thus strengthening the evidence of how health professions education contributes to improved health care outcomes. This contemporary approach to change leads to discovery that complements traditional research. Sharing this work through peer-reviewed literature that employs the standardized approach offered by SQUIRE-EDU will allow exploration of applying improvement science methods to health professions education.

Acknowledgments:

The following individuals were members of the SQUIRE-EDU advisory panel. They contributed to the development through participation in conference calls, emails, and an in-person meeting. The authors are indebted to their time, energy, knowledge, passion, and guidance. Gerry Altmiller, College of New Jersey School of Nursing, Health, & Exercise Science; Elizabeth Armstrong, Harvard Medical School; Karyn D. Baum, University of Minnesota School of Medicine; Nicole Borges, University of Mississippi Medical Center; Tina Foster, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth; Kari Franson, University of Colorado Skaggs School of Pharmacy; Daisy Goodman, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth; Linda Headrick, University of Missouri–Columbia School of Medicine; Kimberly Hoffman, University of Missouri–Columbia School of Medicine; Eric Holmboe, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; Summers Kalishman, University of New Mexico School of Medicine; Rebecca Miltner, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Nursing; Shirley Moore, Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University; Brant Oliver, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth; Patricia O’Sullivan, University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine; Patricia Patrician, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Nursing; Susan Reeves, Colby-Sawyer College School of Nursing; John Sandars, Faculty of Health & Social Care, Edge Hill University (U.K.); Glenda Shoop, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth; David Sklar, University of New Mexico School of Medicine; Marion Slack, University of Arizona College of Pharmacy; Anne Tomolo, Atlanta VA Health Care System and Emory University School of Medicine; Terri Wharholak, University of Arizona College of Pharmacy; Brian M. Wong, University of Toronto Department of Medicine; and Robin M. Zavod, Midwestern University Chicago College of Pharmacy.

The authors also extend their deepest gratitude to David Stevens, Frank Davidoff, and Paul Batalden for their vision and development of the initial SQUIRE guidelines, and their continued support of this work.

Footnotes

Funding/Support: This material is based on work supported by the Health Foundation and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and included the use of facilities and material at the White River Junction VA in White River Junction, Vermont, and at the Louise Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: This work was reviewed and approved by the Dartmouth College Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (STUDY00030300).

Disclaimer: The contents do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

References

- 1.Equator Network. Enhancing the quality and transparency of health research. http://www.equator-network.org. Accessed March 14, 2019.

- 2.Davidoff F, Batalden P, Stevens D, Ogrinc G, Mooney S. Publication guidelines for quality improvement in health care: Evolution of the SQUIRE project. BMJ Qual Saf. 2008;17(suppl 1):i3–i9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, Batalden P, Davidoff F, Stevens D. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): Revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:986–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cook DA, Beckman TJ, Bordage G. A systematic review of titles and abstracts of experimental studies in medical education: Many informative elements missing. Med Educ. 2007;41:1074–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogrinc G, Headrick L, Barton A, Dolansky M, Madigosky W, Miltner R. Fundamentals of Health Care Improvement: A Guide to Improving Your Patients’ Care. 20183rd ed Chicago, IL: Joint Commission Resources. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies L, Donnelly KZ, Goodman DJ, Ogrinc G. Findings from a novel approach to publication guideline revision: User road testing of a draft version of SQUIRE 2.0. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:265–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence. Promoting excellence in healthcare improvement reporting. http://www.squire-statement.org. Published 2016. Accessed March 14, 2019.

- 8.QSEN Institute. Quality and safety education for nurses. www.QSEN.org. Published 2018. Accessed March 14, 2019.

- 9.Davidoff F, Dixon-Woods M, Leviton L, Michie S. Demystifying theory and its use in improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24:228–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bate P, Robert G, Fulop N, Øvretveit J, Dixon-Woods M. Perspectives on Context: A Selection of Essays Considering the Role of Context in Successful Quality Improvement. 2014London, UK: The Health Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplan HC, Provost LP, Froehle CM, Margolis PA. The model for understanding success in quality (MUSIQ): Building a theory of context in healthcare quality improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21:13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitson AL, Rycroft-Malone J, Harvey G, McCormack B, Seers K, Titchen A. Evaluating the successful implementation of evidence into practice using the PARiHS framework: Theoretical and practical challenges. Implement Sci. 2008;3:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barr H, Koppel I, Reeves S, Hammick M, Freeth D. Effective Interprofessional Education: Argument, Assumption and Evidence. 2005Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogrinc G, Nelson WA, Adams SM, O’Hara AE. An instrument to differentiate between clinical research and quality improvement. IRB. 2013;35:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phillips AC, Lewis LK, McEvoy MP, et al. Development and validation of the Guideline for Reporting Evidence-based practice Educational interventions and Teaching (GREET). BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bryk A, Gomez L, Grunow A, LeMahieu P. Learning to Improve: How American Schools Can Get Better at Getting Better. 2015Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cabrera D, Cabrera L, Powers E. A unifying theory of systems thinking with psychosocial applications. Syst Res Behav Sci. 2015;32:534–545. [Google Scholar]