Abstract

Social research in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) aging is a rapidly growing field, but an examination of the use of theory has not yet been conducted for its impact on the field’s direction. We conducted a systematic review of empirical articles published in LGBTQ aging in the years 2009–2017 (N 102). Using a typology of theory use in scholarly articles, we analyzed these articles for the types of theories being used, the degree to which theories were used in each article, and the analytical function they served. We found that 52% of articles consistently applied theory, 23% implied or partially applied theory, and 25% presented as atheoretical. A wide range of theories were used and served multiple analytical functions such as concept development and explanation of findings. We discuss the strengths and weaknesses of theory use in this body of literature, especially with respect to implications for future knowledge development in the field.

Keywords: LGBTQ aging, theory, concepts, conceptual frameworks, social research

Social research in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) aging is a rapidly growing field, bridging multiple disciplines and intersecting areas of scholarship. Along with this momentum and dynamism comes a diverse landscape of theories being applied to this substantive area that have not yet been analyzed for their impact on the direction of the field. This article builds upon a previous systematic review of the key substantive topics recently explored in LGBTQ aging research (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Jen, & Muraco, in press), in which the authors called for more in-depth review of the theoretical foundations of the existing body of research. In this article, we systematically explore the degree to which theory is being used in empirical articles on LGBTQ aging and examine the nature and analytic function of these theories in order to assess the current state of theory use in this field and derive implications for future scholarship.

Literature Review

Like the broader field of social gerontology, current concepts and theories in LGBTQ aging are based on social research (i.e., nonbiomedical) that largely emerged in the mid-to-late 20th century. Notable scholarship in lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) aging first garnered attention in the 1970s as the gay-liberationist movement gained increasing breadth and depth in Western societies (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Muraco, 2010; Rosenfeld, 2010). Since then, disciplinary contributions to the field have come from both aging and sexuality/gender-focused scholars as well as others, including social work, psychology, psychiatry, and sociology in early years and nursing and public health more recently. Several 21st century–edited volumes and special journal issues provide insight into the ideas that have garnered the most attention historically and in recent years. One of the earliest collected works in this century examined gay and lesbian issues in aging, highlighting the role of cohort effects, social change, and visibility in the well-being of older gay men and lesbians (Herdt & deVries, 2004). In 2005, the Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services published a special issue on LGBT caregiving and the role of social, historical, and political contexts for the well-being of LGBT older adults and their caregivers (Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2005). Similarly, Kimmel, Rose and David (2006) addressed these topics in the first edited volume on lesgian, gay, bisexual and transgender aging. Building on these substantive areas, Witten and Eyler (2012) introduced an edited volume on LGBTQ aging by framing many of these topics with respect to resilience, stigma, and trauma. In 2013, the Journal of Religion, Spirituality, and Aging focused a special issue on religiosity and spirituality among LGBT older adults (Brennan-Ing, 2013), illuminating diverse spiritual experiences and their connections to well-being.

Following this trend, the Journal of Gerontological Social Work published a special issue on LGBT aging in 2014, incorporating a range of conceptual and theoretical perspectives such as risk and protective factors, resiliency, sexual identity, life review, queer theory, social support, acceptance, relational perspectives, bereavement, and cultural competency (Rowan & Guinta, 2014). In 2015, The Gerontologist published a supplemental issue highlighting issues of health and aging and findings from Aging With Pride: The National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study, the largest national study of LGBTQ older adults to date (Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2017); just prior to this supplemental issue, Generations devoted an issue to the practice and policy implications derived from this study and the field (Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2016). Similarly, LGBT Health published its inaugural special issue on LGBT aging in 2018, highlighting the urgent need for translational research in the field, federal-level policy advocacy, state-level examples of service provision, health outcomes and disparities, and improvement in survey methods for sampling LGBT older adults (Bradford & Cahill, 2017).

In light of these trends, multiple recent reviews have summarized the historical development of the field and needed next steps. Rosenfeld (2010) argued that a primary focus of this literature serves sociological aims (e.g., emphasizing the experiences of LGBTQ older adults in their social relationships and social world) and policy aims (e.g., examining the potential effects and implications of supportive interventions). Concurrently, a systematic 25-year review of literature on sexual orientation and aging (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Muraco, 2010) identified 58 empirical articles published between 1984 and 2008 focused on LGBTQ aging. Both reviews outlined sequential waves of research with the first wave centering on the dispelling of negative cultural myths or stereotypes and emphasizing life satisfaction of LGBTQ individuals in later life. Fredriksen-Goldsen and Muraco (2010) then outline three subsequent waves of literature: psychosocial adjustment to the aging process, identity development, and social and community-based resources, which overlap patterns identified by Rosenfeld (2010), such as increased attention to social arrangements and generational concerns, to which Rosenfeld added health and policy concerns and increasing inclusion of transgender issues.

Fredriksen-Goldsen and Muraco (2010) also organized their review into bodies of literature corresponding to the four dimensions of the life-course perspective (interplay of historical times and individual lives, linked and interdependent lives, timing of lives, and human agency; Elder, 1994) and found that most substantive topics fell into the first two dimensions. A subsequent review (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., in press) identified 66 articles published between 2009 and 2016 and illustrated not only the rapid, sizable growth in published work focusing on LGBTQ aging but also more breadth and complexity in the substantive, theoretical, and methodological dimensions present in the literature in recent years.

While the purpose of these systematic narrative reviews was to provide an analysis of the current state of LGBTQ aging literature and suggest a blueprint for moving the field forward, they also included a brief review of the theoretical frameworks applied within this work. Fredriksen-Goldsen and Muraco (2010) found that 75% of articles published between 1984 and 2008 did not explicitly use theory in their studies, and for the 25% that did use theory, the primary theoretical perspectives used were the life-course perspective (10% of articles), crisis competence (5%), grounded theory (3%), stress and coping (3%), systems theory (2%), and queer theory (2%). In their later review, Fredriksen-Goldsen, Jen, and Muraco (in press) found that conceptual frameworks were indicated in 43.9% of articles published between 2009 and 2016, showing an 18.9% increase since the first review. The most commonly used approaches were critical (11.2%), ecological/ sociocultural (8.5%), and stress (5.6%) theories. Furthermore, they outlined the Iridescent Life Course to encompass the existing literature extending beyond the traditional life-course tenets. However, this second review indicated that theories varied in their level of application and integration, calling for an in-depth analysis of theory use in LGBTQ aging literature in order to advance theoretical development in this field.

Concerns about the lack of theory use in gerontology, which has famously been referred to as “data rich and theory poor” (Birren, 1999), have surfaced continually since the later part of the 20th century (Bengston, Burgess, & Parrot, 1999; Birren & Bengston, 1988). However, a more recent review of theory usage in social gerontology suggests that the field is trending toward the use of more theory in the 21st century (Alley, Putney, Rice, & Bengston, 2010). This trend is valuable for knowledge development in gerontology because theory use facilitates explanatory understandings of empirical observations and contributes to the accumulation and integration of knowledge over time (Bengston & Setterston, 2016). In the case of LGBTQ aging, a rapidly growing field, the degree to which theory is used and the nature of these theories are likely to shape the early integration of knowledge and form a foundation for future social research.

Research Design

The primary aim of this article is to analyze the use of theory in contemporary LGBTQ aging scholarship. More specifically, we aim to provide readers with an assessment of the degree to which theories are utilized in empirical peer-reviewed articles, an overview of the theories being used, and an analysis of their role in knowledge development in LGBTQ aging. To achieve these goals, we first agreed upon a broadly accepted definition of theory put forth in the gerontological literature. Bengston and Settersten (2016) argue that there are two types of theories represented in contemporary gerontology: (1) “theories of explanation of why and how something occurs” and (2) “theories of orientation that provide a worldview and even a set of explicit assumptions or propositions, which lead us to see and interpret aging phenomena in particular ways” (p. 2). In this analysis, we include theories and theoretical models as both serve to explain the how and why, although models are generally more specific and limited in scope. We also include clearly articulated perspectives, conceptual frameworks, and concepts distinctive to influential bodies of theoretical literature because all of these serve the function of framing and interpretation similar to theories of orientation.

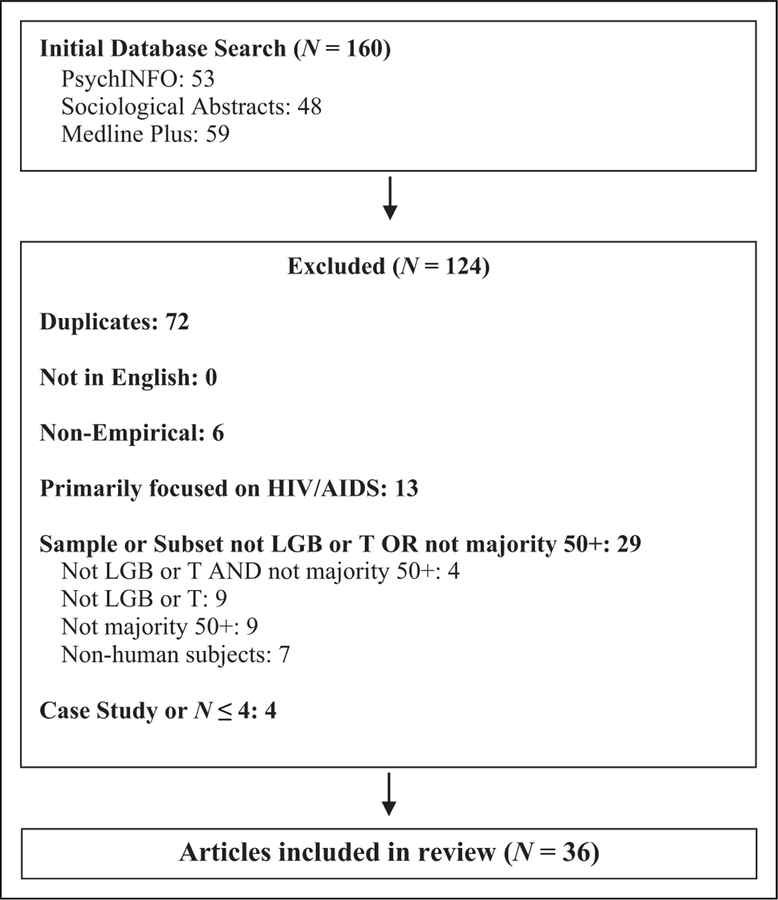

Our next step was to systematically compile a group of peer-reviewed articles in LGBTQ aging to analyze. For this step, we chose to build upon the recent review by Fredriksen-Goldsen et al. (in press) in order to offer a theoretical analysis that would complement their analysis of substantive and methodological issues and trends in the field. This prior review systematically identified 66 articles published between 2009 and 2016 that included LGBTQ adults aged 50 and older or included age-based comparisons between those aged 50 and older with younger counterparts. The search criteria required that articles be published in a peer-review journal, be presented in English, and include original empirical findings with a sample of four or more participants (to exclude case studies). A Boolean phrase search was applied to three databases (PsychInfo, Sociological Abstracts, and Medline PLUS) by combining search terms related to LGBTQ populations (sexuality, sexual minorities, sexual identities, lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, trans*, and gender) with aging-related terms (aging, older adults, elder, and gerontology). For this article, we analyzed the original set of 66 articles, and in addition, to ensure an up-to-date review, we included articles published in 2017 (36 articles) by completing a new search applying the same criteria. In total, we reviewed 102 articles published between 2009 and 2017. See Figure 1 for a flowchart of inclusion/exclusion for the 2017 articles; see Fredriksen-Goldsen et al. (in press) for additional specificity about inclusion/exclusion of 2009–2016 articles.

Figure 1.

Search flow diagram (2017 articles).

Our next step was to devise a method for assessing what theories were used and to what degree they were integrated into the included articles. For this purpose, we turned to Bradbury-Jones, Taylor, and Herber (2014), who proposed a 5-point typology for assessing the degree to which theory informs qualitative research articles, but which is also highly applicable to articles using quantitative methods, as the typology itself is not methodologically oriented. This typology draws attention to five levels of theory use in an article, ranging from seemingly absent to consistently applied, and offers a description of each level to guide its application to an article. See Table 1 (reprinted with permission from Bradbury-Jones, Taylor, and Herber, 2014).

Table 1.

Levels of Theoretical Visibility Typology.

| Level of Theoretical Visibility | Descriptor |

|---|---|

| Level 1: Seemingly absent | Theory is not mentioned at all. |

| Level 2: Implied | Theory may be mentioned or discussed in some detail (mainly in the background and/or introduction sections), and reference might be made to theorists in the field, but no explicit statement is made about the influence of these on the study. |

| Level 3: Partially applied | Researchers explicitly locate their study within a particular theory but then seem to abandon efforts to link, apply, or interpret their findings in that context. Theory is used only partially throughout the research process in relation to the research aims, interview questions, or data analysis. |

| Level 4: Retrospectively applied | Theory is considered at the end of a study as a means of making sense of research findings. Theory may be introduced as an afterthought. |

| Level 5: Consistently applied | Theory is consistently applied throughout the entire research process. Theory guides and directs the various phases of the research process and can be tracked throughout a published article. |

Having established working definitions of theory and concepts based on Bengston and Settersten’s (2016) articulation, a set of articles systematically retrieved from contemporary literature on LGBTQ aging, and a typology for analyzing the degree to which theory is present in and informs an article, we sought to answer the following analytical questions: (1) To what degree is theory used in each article? (2) For articles that do use theory, what theories are being used and what function do they serve in the article? (3) Taken together, how is the current use of theory shaping knowledge development in the field? and (4) What are the strengths, weaknesses, and implications of the state of theory in the field? We conducted this analysis in two phases by posing analytical questions #1 and #2 to each article and then posing analytical questions #3 and #4 to the articles as a whole.

For the first phase, the first and second authors divided up articles and applied the 5-point typology in order to assign a level to each article. We then each recorded the stated name of the theory or concept that was implied or used in the article and wrote a brief topical summary of the role that theory or concept played in the article. For example, we noted whether a theory or concept seemed to be used to provide a background or foundation for the study, was explicitly used to build statistical models and explain relationships between variables, or was used to direct attention to or develop interpretive understandings of a phenomenon. The first author carried out this process for 86 of the articles, and the second author carried out this process for 16 of the articles. We established agreement in this process by reviewing each other’s application of the typology, discussing our application process and ensuring consistency in the analysis, and making joint decisions in a few challenging cases (e.g., if it was difficult to decipher the application of a specific theory and/or its level of use and integration in the article).

We then developed three codes that broadly captured the main functions of theory use noted in our summaries and assigned these codes systematically to all articles. The first code, Background/Context, was assigned when theories or concepts were implied or provided background context for the study. For example, we assigned this code when authors partially applied the theory of minority stress as background and motivation for their examination of mental health usage rates by LGB older adults (Stanley & Duong, 2015). The second code, Conceptual Development, was assigned when an article critiqued or expanded a concept, such as when authors expanded notions of individualization in the end of life (Almack, Seymour, & Bellamy, 2010) or sexual fluidity of older lesbians (Averett, Yoon, & Jenkins, 2011). The third code, Explanation of Findings, was assigned when an article used theory to predict findings or develop explanations for their observations of phenomena, such as using the concept of perceived control to explain aging-related concerns of LGB older adults (Hostetler, 2012). This method yielded results to analytical questions #1 and #2 that we recorded in a spreadsheet, so that we could easily review all aspects of the analytical process to this point.

While posing analytical questions #3 and #4, the first and second authors independently reviewed our spreadsheet of articles, theories, and typology levels and function codes, looking for patterns in the ways that theory use was influencing knowledge development in the field. We recorded our impressions of the data independently in order to bolster rigor. We also documented what we saw as particular strengths and weaknesses of these patterns of knowledge production and what the implications might be for the field based on these assessments. All three authors then reconvened to discuss our analytical impressions and develop consensus on the most salient “takeaway” points from this stage of analysis.

Results

We found that theory or concepts were implied or used to some degree (Levels 2–5 on the Bradbury-Jones et al. typology) in 75% of these articles. Of all the articles, 13% only implied theory or concepts but did not thoroughly define, expand on, or integrate them into the full article. A small number of articles partially applied theory (10%), and no articles seemed to have retrospectively applied theory. We determined that the majority of articles consistently applied a theory or concept (52%). This finding aligns with Fredriksen-Goldsen et al.’s (in press) finding that 43.9% of articles they assessed in their review used some form of a conceptual framework to support the empirical work. Given the expanded parameters of our search that included articles published in 2017, this suggests that a trend may be emerging in which the use of theory in empirical articles in LGBTQ aging is increasing over time. Indeed, if we compare the first half of this time frame with the second half, we see that between 2009 and 2012, 48% of articles consistently applied a theory or concept, and this rose to 53% between 2013 and 2017. Taken together, we feel confident that theories or concepts are being used in contemporary social research in LGBTQ aging about half the time and that this usage is increasing over time.

In terms of the function of the theories and concepts implied or applied, 22% of the articles seemed to use a theory or concept primarily as background or context for the study. This often took the form of providing a motivation or sociohistorical context for the study. For example, several articles used minority stress theory to situate and motivate an investigation into the various lived experiences of LGBT older adults in a heterosexist and transphobic society; however, they did not consistently apply or develop this theory throughout the design, analysis, findings, and discussion of the study (Mock & Schryer, 2017; Periera et al., 2017; Stanley & Duong, 2015). We found that in 25% of these articles, authors used theory or a concept for the purpose of conceptual development or expansion. For example, one article used the concept of coping to motivate and frame a study but also applied the analysis and findings to expand this concept and offer a more nuanced understanding of its meaning and function in the lives of LGB older adults (Seelman, Lewinson, Engelman, Maley, & Allen, 2017). Another used the convoy model of social relations to motivate and design a study of social networks of older gay men and used the empirical material to add substantive and conceptual dimensions to this well-known model in gerontology (Tester & Wright, 2017).

In 28% of articles, authors used theory or concepts to offer explanations of findings to readers, which often took the form of positing an explanation of how and why variables or constructs were associated or offering an explanation of how a phenomenon occurs. For example, Kuyper and Fokkema (2010) used minority stress theory at every stage of their study to explain differences in loneliness outcomes in LGB older adults in the Netherlands. They concluded by arguing for social and political means of intervening to reduce minority stress in this population, demonstrating how a theory can be used consistently to inform every stage of a project. Similarly, Kong (2012) used the poststructuralist power-resistance paradigm as the foundation and theoretical guide for all stages of his study of older gay men’s use of space in Hong Kong, providing a deconstruction of the traditional public/private dichotomy of space based on his data and interpretations. An overview of the distribution of ratings we assigned from the typology and the distribution of functions we assigned to articles is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Typology and Theory Function.

| Typology and Theory Function | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Rating on Bradbury-Jones typology | ||

| Level 1: Seemingly absent | 26 | 25 |

| Level 2: Implied | 13 | 13 |

| Level 3: Partially applied | 10 | 10 |

| Level 4: Retrospectively applied | 0 | 0 |

| Level 5: Consistently applied | 53 | 52 |

| Total | 102 | 100 |

| Theory function | ||

| None | 26 | 25 |

| Background/context | 22 | 22 |

| Conceptual development | 26 | 25 |

| Explanatory findings | 28 | 28 |

| Total | 102 | 100 |

We found a wide range of types of theories or concepts implied or used in these articles, but several dominant approaches stand out. The most commonly used theory or concept implied or consistently applied revolved around notions of stress (16% of all articles); most often, specifically referencing minority stress and the ways in which members of minority groups experience individual-level and community-level stressors (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim, Muraco, & Mincer, 2009; Gardner, de Vries, & Mockus, 2014; Gonzales & Henning-Smith, 2015; Hoy-Ellis & Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2017; Jenkins Morales, King, Hiler, Coopwood, & Wayland, 2014; Kuyper & Fokkema, 2010; Lyons et al., 2017; Mock & Schryer, 2017; Periera et al., 2017; Rowan & Beyer, 2017; Stanley & Duong, 2015; Velduis, Talley, Hancock, Wilsnack, & Hughes, 2017; Woody, 2015), along with conceptualizations of social stress (Kim & Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2017) and combinations of social stress and minority stress (Wight, LeBlanc, deVries, & Detels, 2012). In one case, the concept of minority stress was integrated with a resilience perspective (Woody, 2015).

The second most common theory or concept implied or used in these articles was the Health Equity Promotion Model—9% of all articles); this model appears in more recent literature on LGBTQ aging, incorporating a life-course development perspective to understand pathways and risk and protective factors determining health, aging, and well-being (Bryan, Kim, & Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2017; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2017; Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim, Bryan, Shiu, & Emlet, 2017; Fredriksen-Goldsen, Shiu, Bryan, Goldsen, & Kim, 2017; Goldsen et al., 2017; Hoy-Ellis et al., 2017; Kim, Jen, & Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2017; Kim, Fredriksen-Goldsen, Bryan, & Muraco, 2017; Shiu, Kim, & Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2017). Because the Health Equity Promotion Model integrates a life-course perspective, it has been applied to assess LGBTQ aging over time and across the life span of LGBTQ older adults, as well as to differentiate cohort effects from period and age effects (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Kim, 2017).

The third most common theory or concept implied or used in these articles is resilience (5% of all articles), which emphasized individual-, social-, and community-level means of coping and thriving despite challenges to well-being (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim, Muraco, et al., 2009; Rowan & Butler, 2014), to identify risk and protective factors for health and well-being (Emlet, Fredriksen-Goldsen, & Kim, 2013; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2012; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2014), or to help explain self-efficacy in the face of barriers to well-being (Emlet, Shiu, Kim, & Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2017).

In addition to minority stress, the Health Equity Promotion Model, and resilience, many other theoretical and conceptual approaches were being applied in contemporary social research in LGBTQ aging. For articles that consistently apply a theory or concept (Level 5 on the Bradbury-Jones et al., 2014, typology), we noted two additional theoretical trends that give shape to current knowledge production in the field. First, we noted that some articles used critical perspectives (which challenge social norms and structures in their analysis of individual-level experiences), using theories and concepts such as intersectionality and embodied masculinity (Slevin & Linneman, 2009); queer theory (Fabbre, 2014, 2015; Rosenfeld, 2010), domestic materiality and queer theory (Pilkey, 2014); an integrated framework combining social gerontology, queer theory, and social work theory (Siverskog, 2014); Black feminism (Woody, 2014); a feminist political economy framework (Grigorovich, 2014); a feminist ethic of care perspective (Grigorovich, 2015); positioning theory and intersectionality (Ussher, Rose, & Perz, 2017); a poststructuralist power-resistance paradigm (Kong, 2012); and discourse of the “right to die” movement (Westwood, 2017). While varied, these theories and concepts generally focus on illuminating normative (and often oppressive) social forces, understanding their impact, and highlighting forms of resistance or alternative forces. These articles are shaping the field by foregrounding societal-level critiques of taken-for-granted aspects of gender and sexuality, while also promoting new empirical knowledge about LGBTQ older adults’ lived experiences.

Second, we noted that some articles stemmed from social or nonbiomedical sciences and focused especially on describing and explaining how social and psychological phenomena and processes occur or unfold, using theories and concepts such as the convoy model of social relations (Kim, Fredriksen-Goldsen, Bryan, & Muraco, 2017; Tester & Wright, 2017), communal relationship theory (Muraco & Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2014), social integration theory (Williams & Fredrisksen-Goldsen, 2014), social capital theory (Erosheva, Kim, Emlet, & Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2015), the sailing model of estrangement (deGuzman et al., 2017), defensive othering (Suen, 2017), the individualization thesis (Almack et al., 2010), a framework explaining long-term care strategies of older lesbians (Gabrielson, 2011), sexual fluidity (Averett et al., 2011), normative creativity (Parslow & Hegarty, 2013), aging capital (Simpson, 2013), successful aging (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim, Shiu, Goldsen, & Emlet, 2014; Porter, Ronneberg, & Witten, 2013; Van Wagenen, Driskell, & Bradford, 2013), subjective well-being (Sagie, 2015), internalized ageism (Wight, LeBlanc, Meyer, & Harig, 2015), agency in the life course (Fabbre, 2017), coping and coping strategies (Seelman et al., 2017), perceived control (Hostetler, 2012), the Andersen Model (Brennan-Ing, Seidel, London, Cahill, & Karpiak, 2014), Ryff and Singer’s conceptualization of psychological well-being (Putney, 2014), socioemotional selectivity theory (Sullivan, 2014), social practice theory (SPT; Cohen & Cribbs, 2017), and internalized and enacted sexual identity stigma (Emlet, Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim, & Hoy-Ellis, 2017). While examining different processes, these approaches “dig deep” into the complex ways that social forces and psychological functioning inform identity and well-being. These diverse and detailed analyses may also directly inform therapeutic and policy interventions, contributing pragmatic and useful knowledge for the field.

Discussion

The goal of this review was to provide an overview of the state of theory use in LGBTQ aging research, and we conclude by considering the impact of articles that utilized theory to different degrees, discussing strengths and weaknesses in this usage, and drawing conclusions about what this means for the field moving forward.

In terms of knowledge development, while Level 1 articles (theory use seemingly absent) did not use theory or concepts explicitly, we interpret these as “setting the stage” for additional work, often by identifying characteristics of distinct groups within the larger LGBTQ older adult population, providing descriptive statistics to fill gaps in foundational empirical knowledge, calling attention to key issues, or addressing methodological concerns. For example, Michaels et al. (2017) analyze the limitations of common survey questions (in both English and Spanish) used to determine the gender and sexual identity of older survey respondents and through the use of cognitive interviewing, propose more valid measures of these constructs for survey research. This example provides a necessary contribution to the field and demonstrates the usefulness of articles whose purpose is not to advance theory but rather to advance modes of empiricism such as sampling, measurement, or statistical modeling.

We found that Level 2 articles (implied use of theory) begin to use theoretical language, particularly in introductions or literature reviews, to set up the precedent or context of a study. Many of these articles refer to stress, coping, and resilience with respect to constraining sociohistorical contexts as the motivation for a study but do not advance these ideas conceptually throughout the article. In comparison to Level 1 articles, many of these Level 2 articles move beyond empirical-only goals and reference theory or concepts in an effort to situate LGBTQ older adults with respect to socioecological considerations of aging. Many of these articles might have easily been categorized with a Level 3 rating (partial application of theory) by integrating a relevant theory or concept mentioned in the introduction of the article into more aspects of design, analysis, findings, and discussion sections. This pattern suggests that many articles illustrate potential for additional theoretical development and contribution if theory were more consistently applied across the study design and throughout the research process. Similarly, we found that Level 3 articles also used theory or concepts to provide background or context for a study, though with a stronger emphasis on conceptual orientation and more attention to the theoretical landscape in social gerontology. For instance, Brennan-Ing, Seidel, Larson & Karpiak (2014) use of Hierarchical Compensatory Theory places LGBTQ aging within the broader conversation in gerontological literature around accessing social support, and Orel’s (2014) use of the life-course perspective offers an application of a broadly used theory to the specific life-course considerations of LGBT older adults. Level 3 articles in this review move beyond providing sociohistorical context for empirical work and offer theoretical context as well. We did not find any articles that fit Level 4 characteristics (retrospectively applied theory); however, it is possible that retrospectively applied theories were written into the introduction and following sections of an article, making it difficult to ascertain the actual process through which they were applied.

The majority of articles in this review (52%) were rated as Level 5 (consistent application of theory or concepts) as they either contributed significantly to the development of a concept or provided an in-depth explanation of findings. These articles were much more varied in the theories and concepts used and serve to both expand and deepen the theoretical nature of LGBTQ aging as a field. Interestingly, among articles that consistently applied a theory or concept, about half contributed to conceptual development and about half provided explanations of findings. For example, Slevin and Linneman (2009) developed the concept of embodied masculinity by investigating the ways in which older gay men experience their bodies and social identities in later life, finding that men embody multiple and sometimes contradictory aspects of masculinity as they age and that intersecting identities shape how they perceive their aging bodies in the social world. In this way, the concept of embodied masculinity is further developed in order to account for multiplicity and contradiction in lived experience. Cohen and Cribbs (2017), writing from a public health perspective, use SPT to design a study of the everyday food practices of community-dwelling LGBT older adults in the context of risk for malnutrition. They find that LGBT older adults’ daily food practices are more than expressions of individual choice but rather are socially constructed and acquired across their lives in ways that are explained by social contexts. The authors use SPT to explain the food practices of study participants and generate implications for senior nutrition programs. In summary, we found that Level 5 articles engaged in a more in-depth process of utilizing theory, and at times critiquing or expanding theory, in ways that advance the theoretical landscape of LGBTQ aging.

In terms of strengths of the field, we perceive an emerging trend toward increased use of theory and believe this will strengthen the field by extending empirical articles’ relevance and contributions to the broader field of gerontology. While both theoretical and nontheoretical articles can contribute to the substantive knowledge development and growth of LGBTQ aging literature in critical ways, when scholars apply theories and concepts often used in gerontology, such as stress, coping, and resilience, to a unique subgroup of older adults, they create a conceptual bridge that holds potential for greater integration between research on minority groups and research on older adults more broadly. We also found in this review that scholars in LGBTQ aging are utilizing or developing theories that fill conceptual gaps left by mainstream gerontology. For example, Rosenfeld (2010), Fabbre (2014, 2015), and Pilkey (2014) all use queer theory (which earlier had not been used in gerontology) to understand the ways in which heteronormative social forces influence the aging experiences and well-being of LGBTQ older adults. Similarly, Fredriksen-Goldsen and colleagues generated the Health Equity Promotion Model in order to conceptualize life-course developmental influences and the complex pathways to health and well-being that move beyond the limitations of previous models, such as minority stress, that emphasized deficits and may have overlooked resources and strengths in these communities (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Kim, 2017).

We think that the wide range of theories used (especially those used in Level 5 articles) constitutes both strength and weakness. The diversity of theories being used may function similarly to ecological diversity, wherein multiple paths for development, adaptation, and evolution are possible to advance an ecosystem when you have a diversity of organisms and subsystems. A diversity of theories may also better reflect the unique experiences of various subgroups within the broader LGBTQ aging population. Given the relative early stage of LGBTQ aging relative to gerontology as a whole, this may provide a particularly generative foundation for future scholarship. However, it may also serve to fragment the field and limit theoretical advancement if scholars are not consistently critiquing and improving clearly established theoretical paths, particularly in terms of their relevance for and application to research with various subgroups of LGBTQ older adults. In this regard, we observed that very few articles explicitly critique theories or suggest ways to improve them. This was true even among articles that consistently applied theory, meaning that even when articles are using theory, they may not necessarily be improving or advancing theory for future use.

Our review also generated several questions. First, the nature of the theoretical landscape made us wonder: Are we fully taking advantage of theories and concepts from areas like women, gender and sexuality studies, and queer studies? We saw some use of critical perspectives from these domains (e.g., queer theory, embodied masculinity, feminist political economy framework), but they accounted for about 10% of theoretical contributions, which is surprising given their direct relation to marginalized populations and power dynamics that many authors in LGBTQ aging research consider. Scholarly work on gender and sexuality in the humanities has generated theoretical perspectives that challenge many normative, taken-for-granted aspects of contemporary societies that could be applied to aging and later life to develop alternative understandings of the human life course. For example, Ahmed’s (2010) argument that happiness in heteronormative societies is often contingent on peoples’ willingness to live their lives according to cultural norms could be used to critique constructions of successful aging and their application to LGBTQ older adults. Critical perspectives, such as Ahmed’s, may also be useful as scholars seek to attend to bisexual, transgender, and queer perspectives on aging, which may challenge constructions of sexuality and gender based only on lesbian and gay identities.

In addition, we think increased use of critical theories and perspectives holds the potential to transcend disciplinary boundaries. This is already taking place as aging studies become an increasingly multidisciplinary field where scholars from areas like literature and sociology come together through their use of similar theoretical perspectives on aging and later life (North American Network in Aging Studies [NANAS], 2018). Our findings suggest that social researchers in LGBTQ aging are moving in the direction of more theory use and therefore might benefit from further engagement with organizations such as NANAS. In addition, as attention to health equity increases in the field, there may be more potential to utilize concepts and theories from the biomedical sciences, especially as they pertain to pathways to well-being in later life. Although the Bradbury-Jones et al. (2014) typology of theory use does not attend to the disciplinary backgrounds of authors and theories, this information would also provide a useful means for examining the overall trends, major influences, and fruitful future directions for theory use in this body of literature.

Another concern that arose as we reflected on our findings was that while about 50% of articles are consistently applying theory, about half of contemporary articles are virtually atheoretical. If the majority of these articles are primarily empirical in nature, we worry that they will have a short “shelf life” and quickly become historical artifacts, documenting or providing a snapshot of characteristics or needs of LGBTQ older adults at one point in time without offering conceptual tools for future scholars to use and refine. While some historical record and empirical landscape is important, especially in articles that illuminate previously unknown characteristics of a population, there is also a need to think collectively about what kind of balance between theoretical and empirical work is best suited for stimulating future work.

These findings hold important implications for the field of LGBTQ aging. Currently, theory use is moving forward on multiple paths and while the field currently relies about equally on description and theory building for knowledge development, there is potential for greater leaps in application, integration, and expansion. Theory is also serving several functions in empirical work, providing significant breadth in sociohistorical context, conceptual development, and explanatory findings. Stress and resilience are still common approaches but are being complemented by newer life-course perspectives such as the Health Equity Promotion Model. This means our collective attention is still being drawn to the impact of minority status and the resilience generated by LGBTQ older adults but also with an eye to life-course risk and protective factors that may guide improved interventions. Notably, the field is using critical theories and challenging social structures, but this usage is somewhat outweighed by a focus on social and psychological phenomena and processes. This means that while we may understand how and why LGBTQ older adults age the way they do, we may be missing opportunities to challenge and change oppressive social forces in society through the use of critical and transformative approaches. Further, attention to bisexual, transgender, and queer identities could be bolstered by achieving more balance in these theoretical domains.

Conclusion

Social research in LGBTQ aging is a rapidly evolving field with a dynamic and promising theoretical landscape. We found that the majority of empirical articles in this field use theory or concepts to some degree and that about 50% consistently apply theories or concepts throughout. While a few influential theoretical trends stand out, there is also a wide range of conceptual tools being used in the field, which may facilitate diverse directions for theory development but runs the risk of fragmenting the field as it grows. Scholars in LGBTQ aging research should work collectively to nurture theoretical work in the field in ways that offer depth and continuity to inform future waves of gerontological scholarship in this substantive domain.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Biographies

Vanessa D. Fabbre is an assistant professor at the Brown School at Washington University in St. Louis, where she is also affiliate faculty in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and a faculty scholar at the Institute for Public Health.

Sarah Jen is an assistant professor at the School of Social Welfare at the University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS.

Karen Fredriksen-Goldsen is a professor at the School of Social Work, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, where she is also Director of the Healthy Generations Hartford Center of Excellence and Director of the Institute for Multigenerational Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ahmed S (2010). The promise of happiness Durham, NC: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alley DE, Putney NM, Rice M, & Bengston V (2010). The increasing use of theory in social gerontology: 1990–2004. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 65B, 583–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almack K, Seymour J, & Bellamy G (2010). Exploring the impact of sexual orientation on experiences and concerns about end of life care and on bereavement for lesbian, gay, and bisexual older people. Sociology, 44, 908–924. [Google Scholar]

- Averett P, Yoon I, & Jenkins CL (2011). Older lesbians: Experiences of aging, discrimination and resilience. Journal of Women & Aging, 23, 216–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengston VL, Burgess EO, & Parrott TM (1999). Theory, explanation, and a third generation of theoretical development in social gerontology. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 52B, S72–S88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengston VL, & Setterston RA Jr. (2016). Theories of aging: Developments within and across disciplinary boundaries. In Bensgton VL & Setterston RA Jr. (Eds.), Handbook of theories of aging (3rd ed.) (pp. 1–6). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Birren JE (1999). Theories of aging: A personal perspective. In Bengtson VL & Schaie KW (Eds.), Handbook of theories of aging (pp. 459–471). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Birren JE, & Bengston VL (Eds.). (1988). Emergent theories of aging New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury-Jones C, Taylor J, & Herber O (2014). How theory is used and articulated in qualitative research: Development of a new typology. Social Science and Medicine, 120, 135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford JB, & Cahill SR (Eds.). (2017). LGBT aging [Special issue]. LGBT Health, 4, 241–314.28708449 [Google Scholar]

- Brennan-Ing M (Ed.). (2013). Spirituality and religion among older lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender adults [Special issue]. Journal of Religion, Spirituality, and Aging, 25(2), 67–204. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan-Ing M, Seidel L, Larson B, & Karpiak SE (2014). Social care networks and older LGBT adults: Challenges for the future. Journal of Homosexuality, 61, 21–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan-Ing M, Seidel L, London AS, Cahill S, & Karpiak SE (2014). Service utilization among older adults with HIV: The joint association of sexual identity and gender. Journal of Homosexuality, 61, 166–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan AEB, Kim H, & Fredriksen-Goldsen KI (2017). Factors associated with high-risk alcohol consumption among LGB older adults: The roles of gender, social support, perceived stress, discrimination, and stigma. The Gerontologist, 57, S95–S104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen N, & Cribbs K (2017). The everyday food practices of community-dwelling lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) older adults. Journal of Aging Studies, 41, 75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deGuzman AB, Valdez LP, Orpiana MB, Orantia NAF, Oledan PVE, & Cenido KM (2017). Against the current: A grounded theory study on the estrangement experiences of a select group Filipino gay older persons. Educational Gerontology, 43, 329–340. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH (1994). Time, human agency, and social change: Perspectives on the life course. Social Psychology Quarterly, 57, 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Emlet CA, Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, & Kim HJ (2013). Risk and protective factors associated with health-related quality of life among older gay and bisexual men living with HIV disease. The Gerontologist, 53, 963–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emlet CA, Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim H, & Hoy-Ellis CP (2017). The relationship between sexual minority stigma and sexual health risk behaviors among HIV-positive older gay and bisexual men. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 36, 931–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emlet CA, Shiu C, Kim H, & Fredriksen-Goldsen KI (2017). Bouncing back: Resilience and master among HIV positive older gay and bisexual men. The Gerontologist, 57, S40–S49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erosheva EA, Kim H, Emlet C, & Fredriksen-Goldsen KI (2015). Social networks of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender older adults. Research on Aging, 1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fabbre VD (2014). Gender transitions in later life: The significance of time in queer aging. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 57, 161–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbre VD (2015). Gender transitions in later life: A queer perspective on successful aging. The Gerontologist, 55, 144–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbre VD (2017). Agency and social forces in the life course: The case of gender transitions in later life. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 72, 479–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI (Ed.). (2005). GLBT Caregiving [Special issue]. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services, 18(3–4), 1–145. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI (Ed). (2017). Aging with pride: National health, aging, and sexuality/gender study (NHAS) [Supplemental issue]. The Gerontologist, 57, S1–S114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI (Ed.). (2016, Summer). LGBT aging. Generations, 40(2) 6–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Bryan AEB, Jen S, Goldsen J, Kim H, & Muraco A (2017). The unfolding of LGBT lives: Key events associate with health and well-being in later life. The Gerontologist, 57, S15–S29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Cook-Daniels L, Kim HJ, Erosheva EA, Emlet CA, Hoy-Ellis CP, … Muraco A (2014). Physical and mental health of transgender older adults: An at-risk and underserved population. The Gerontologist, 54, 488–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Emlet CB, Kim H, Muraco A, Erosheva EA, Goldsen J, & Hoy-Ellis CP (2012). The physical and mental health of lesbian, gay male, and bisexual (LGB) older adults: The role of key health indictors and risk and protective factors. The Gerontologist, 53, 664–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Jen S, & Muraco A (in press). Iridescent life course: LGBTQ aging research and blueprint for the future—A systematic review. Gerontology [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, & Kim HJ (2017). The science of conducting research with LGBT older adults—An introduction to aging with pride: National health, aging, and sexuality/gender study (NHAS). The Gerontologist, 57, S1–S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim H, Bryan AEB, Shiu C, & Emlet CS (2017). The cascading effects of marginalization and pathways of resilience in attaining good health among LGBT older adults. The Gerontologist, 57, S72–S83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim H, Muraco A, & Mincer S (2009). Chronically ill midlife and older lesbians, gay men and bisexuals and their informal caregivers: The impact of the social context. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 6, 52–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim HJ, Shiu C, Goldsen J, & Emlet CA (2014). Successful aging among LGBT older adults: Physical and mental health-related quality of life by age group. The Gerontologist, 55, 154–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, & Muraco A (2010). Aging and sexual orientation: A 25-year review of the literature. Research on Aging, 32, 372–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Shiu C, Bryan AEB, Goldsen J, & Kim H (2017). Health equity and aging of bisexual older adults: Pathways of risk and resilience. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 73, 468–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielson ML (2011). “I will not be discriminated against”: Older lesbians creating new communities. Advances in Nursing Science, 34, 357–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner AT, de Vries B, & Mockus DS (2014). Aging out in the desert: Disclosure, acceptance and service use among midlife and older lesbians and gay men. Journal of Homosexuality, 61, 129–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsen J, Bryan AEB, Kim H, Muraco A, Jen S, & Fredriksen-Goldsen KI (2017). Who says I do: The changing context of marriage and health and quality of life for LGBT older adults. The Gerontologist, 57, S50–S62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales G, & Henning-Smith C (2015). Disparities in health and disability among older adults in same-sex cohabiting relationships. Journal of Aging and Health, 27, 432–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigorovich A (2014). Restricted access older lesbian and bisexual women’s experiences with home care services. Research on Aging, 37, 763–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigorovich A (2015). The meaning of quality of care in home care settings: Older lesbian and bisexual women’s perspectives. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 30, 108–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdt G, & deVries B (Eds.). (2004). Gay and lesbian aging: Research and future directions New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hostetler AJ (2012). Community involvement, perceived control, and attitudes toward aging among lesbians and gay men. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 75, 141–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoy-Ellis CP, & Fredriksen-Goldsen KI (2017). Depression among transgender older adults: General and minority stress. American Journal of Community Psychology, 59, 295–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoy-Ellis CP, Shiu C, Sullivan KM, Kim H, Sturges AM, & Fredriksen-Goldsen KI (2017). Prior military service, identity stigma, and mental health among transgender older adults. The Gerontologist, 57, S63–S71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins Morales M, King MD, Hiler H, Coopwood MS, & Wayland S (2014). The greater St. Louis LGBT health and human services needs assessment: An examination of the Silent and Baby Boom Generations. Journal of Homosexuality, 61(1), 103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, & Fredriksen-Goldsen KI (2017). Disparities in mental health quality of life between Hispanic and non-Hispanic white LGB midlife and older adults and the influence of lifetime discrimination, social connectedness, socioeconomic status, and perceived stress. Research on Aging, 39, 991–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Bryan AEB, & Muraco A (2017). Social network types and mental health among LGBT older adults. The Gerontologist, 57, S84–S94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Jen S, & Fredriksen-Goldsen KI (2017). Race/ethnicity and health-related quality of life among LGBT older adults. The Gerontologist, 57, S30–S39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel D, Rose T, & David S (Eds.). (2006). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and trans-gender aging New York, NY: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kong TSK (2012). A fading Tongzhi heterotopia: Hong Kong older gay men’s use of spaces. Sexualities, 15, 896–916. [Google Scholar]

- Kuyper L, & Fokkema T (2010). Loneliness among older lesbian, gay and bisexual older adults: The role of minority stress. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 1171–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons A, Alba B, Heywood W, Fileborn B, Minichiello V, Barrett C, … Dow B (2017). Experiences of ageism and the mental health of older adults. Aging and Mental Health Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Michaels S, Milesi C, Stern M, Voix MH, Morrison H, Guerino P, … Haffer SC (2017). Improving measures of sexual and gender identity in English and Spanish to identify LGBT older adults in surveys. LGBT Health, 4, 412–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mock SE, & Schryer E (2017). Perceived support and the retirement expectations of sexual minority adults. La revue Canadienne du vieillissement [Canadian Journal on Aging], 36, 170–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraco A, & Fredriksen-Goldsen KI (2014). The highs and lows of caregiving for chronically ill lesbian, gay, and bisexual elders. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 57, 251–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North American Network in Aging Studies (2018). Retrieved from http://agingstudies.org/NANAS/

- Orel NA (2014). Investigating the needs and concerns of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults: The use of qualitative and quantitative methodology. Journal of Homosexuality, 61, 53–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parslow O, & Hegarty P (2013). Who cares? UK lesbian caregivers in a heterosexual world. Women’s Studies International Forum, 40, 78–86. [Google Scholar]

- Periera H, Serrano JP, de Vries B, Esgalhado G, Afonso RM, & Monteiro S (2017). Aging perceptions in older gay and bisexual men in Portugal: A qualitative study. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pilkey B (2014). Queering heteronormativity at home: Older gay Londoners and the negotiation of domestic materiality. Gender, Place & Culture, 21, 1142–1157. [Google Scholar]

- Porter KE, Ronneberg CR, & Witten TM (2013). Religious affiliation and successful aging among transgender older adults: Findings from the Trans MetLife Survey. Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging, 25, 112–138. [Google Scholar]

- Putney JM (2014). Older lesbian adults’ psychological well-being: The significance of pets. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 26, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld D (2010). Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender ageing: Shattering myths, capturing lives. In Dannefer D & Phillipson C (Eds.), The Sage handbook of social gerontology (pp. 226–238). London, England: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Rowan NL, & Beyer K (2017). Exploring the health needs of aging LGBT adults in the Cape Fear Region of North Carolina. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 60, 569–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan NL, & Butler SS (2014). Resilience in attaining and sustaining sobriety among older lesbians with alcoholism. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 57, 176–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan NL, & Giunta N (Eds.). (2014). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender aging: The role of gerontological social work [Special issue]. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 57(2–4), 75–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagie O (2015). Predictors of well-being among older gays and lesbians. Social Indicators Research, 120, 859–870. [Google Scholar]

- Shiu C, Kim H, & Fredriksen-Goldsen KI (2017). Health care engagement among LGBT older adults: The role of depression diagnosis and symptomatology. The Gerontologist, 57, S105–S114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seelman KL, Lewinson T, Engelman L, Maley OR, & Allen A (2017). Coping strategies used by LGB older adults in facing and anticipating health challenges: A narrative analysis. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 29, 300–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson P (2013). Alienation, ambivalence, agency: Middle-aged gay men and ageism in Manchester’s gay village, 283–299.

- Siverskog A (2014). “They just don’t have a clue”: Transgender aging and implications for social work. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 57, 386–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slevin KF, & Linneman TJ (2009). Old gay men’s bodies and masculinities. Men and Masculinities, 12, 483–507. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley IH, & Duong J (2015). Mental health service use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults. Psychiatric Services, 66, 743–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suen YT (2017). Older single gay men’s body talk: Resisting and rigidifying the aging discourse in the gay community. Journal of Homosexuality, 64, 397–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan KM (2014). Acceptance in the domestic environment: The experience of senior housing for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender seniors. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 57, 235–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tester G, & Wright ER (2017). Older gay men and their support convoys. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 72, 488–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ussher JM, Rose D, & Perz J (2017). Mastery, isolation, or acceptance: Gay and bisexual men’s construction of aging in the context of sexual embodiment after prostate cancer. The Journal of Sex Research, 54, 802–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wagenen A, Driskell J, & Bradford J (2013). “I’m still raring to go”: Successful aging among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults. Journal of Aging Studies, 27, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velduis CB, Talley AE, Hancock DW, Wilsnack SC, & Hughes TL (2017). Alcohol use, age, and self-rated mental and physical health in a community sample of lesbian and bisexual women. LGBT Health, 4, 419–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westwood S (2017). Older lesbians, gay men and the “Right to Die” Debate: “I always keep a lethal dose of something, because I don’t want to become an elderly isolated person.” Social and Legal Studies, 26, 606–628. [Google Scholar]

- Wight RG, LeBlanc AJ, de Vries B, & Detels R (2012). Stress and mental health among midlife and older gay-identified men. American Journal of Public Health, 102, 503–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wight RG, LeBlanc AJ, Meyer IH, & Harig FA (2015). Internalized gay ageism, mattering, and depressive symptoms among midlife and older gayidentified men. Social Science & Medicine, 147, 200–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams ME, & Fredriksen-Goldsen KI (2014). Same-sex partnerships and the health of older adults. Journal of Community Psychology, 42, 558–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witten TM, & Eyler AE (Eds.). (2012). Gay, lesbian, bisexual & transgender aging: Challenges in research, practice & policy Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Woody I (2014). Aging out: A qualitative exploration of ageism and heterosexism among aging African American lesbians and gay men. Journal of Homosexuality, 61, 145–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody I (2015). Lift every voice: Voices of African-American lesbian elders. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 19, 50–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]