Abstract

Natural killer (NK) cells can recognize target cells such as virus infected and tumor cells through integration of activation and inhibitory receptors. Recognition by NK cells can lead to direct lysis of the target cell and production of the signature cytokine IFNγ. Yet it is unclear whether stimulation through activation receptors alone is sufficient for IFNγ production. Here, we show that NK activation receptor-engagement requires additional signals for optimal IFNγ production, which could be provided by IFNβ or IL-12. Stimulation of murine NK cells with soluble antibodies directed against NK1.1, Ly49H, Ly49D, or NKp46 required additional stimulation with cytokines, indicating that a range of activation receptors with distinct adaptor molecules require additional stimulation for IFNγ production. The requirement for multiple signals extends to stimulation with primary m157-Tg target cells, which triggers the activation receptor Ly49H, suggesting that NK cells do require multiple signals for IFNγ production in the context of target cell recognition. Using qPCR and RNA flow cytometry, we found that cytokines, not activating ligands, act on NK cells to express Ifng transcripts. Ly49H engagement is required for IFNγ translational initiation. Results using inhibitors suggest that the Proteasome-Ubiquitin-IKK-TPL2-MNK1 axis was required during activation receptor engagement. Thus, this study indicates that activation receptor-dependent IFNγ production is regulated on the transcriptional and translational levels.

Introduction

Natural killer (NK) cells recognize and attack target cells, including cancer and pathogen-infected cells, through a combination of activation and inhibitory receptor–ligand interactions. Upon recognition of a target cell through such interactions NK cells can directly induce lysis of the target, but also produces the signature cytokine IFNγ. Activation receptor dependent IFNγ production is frequently studied to assess NK cell functionality (1). NK cells can produce IFNγ in response to cytokines as well, in particular IL-12 in combination with IL-18 results in strong IFNγ production (2). Yet, unclear is whether these pathways intersect.

Production of IFNγ by NK cells has been shown to contribute to viral control and tumor rejection. For example, NK cells are the main source of IFNγ during early stages of MCMV infection (3). This IFNγ produced early during infection contributes to MCMV clearance, particularly in the liver (4). A susceptibility locus on mouse chromosome 10 is associated with impaired MCMV control and decreased NK IFNγ production, whereas IFNγ produced by T cells is unaffected (5), providing genetic evidence suggesting NK cell-produced IFNγ is critical for viral control. IFNγ production during MCMV infection requires IL-12 and depends on STAT4 (3, 6). In addition, IL-18 synergizes with IL-12 to induce IFNγ during infection (7). Thus, in the context of MCMV infection the role for cytokines inducing NK cell IFNγ is well established. NK cell IFNγ production has been shown to control metastasis formation of B16 melanoma sub-line (8), implicating a role for NK cell IFNγ in controlling tumors as well.

It is well established that ligation of activation receptors trigger NK cells to produce IFNγ, but there is a body of evidence suggesting that stimulation through an activation receptor alone is insufficient for optimal IFNγ production. Stimulation of mouse NK cells with plate-bound antibodies against activation receptors such NK1.1 or Ly49H triggers IFNγ production (9–11). In contrast, stimulation with soluble antibodies does not induce IFNγ, whereas soluble anti-Ly49D has been reported to induce phosphorylation of SLP76 and ERK (12). This indicates that soluble antibody is capable to induce NK cell activation but not IFNγ production. Plate-bound anti-NKG2D dependent NK cell GM-CSF production requires signaling through CD16 (13), suggesting that plate-bound antibody may also trigger Fc receptors. Moreover, antibodies against different receptors synergize for human NK cell IFNγ and TNFα production when coated on the same beads (14) and a combination of activation receptor ligands and adhesion molecules is required on insect target cells to induce IFNγ by freshly isolated human NK cells (15). Overexpression of activation ligands on certain cell lines induces IFNγ by resting mouse NK cells, including over-expression of m157 and NKG2D ligands (5, 16, 17). In addition, NK cells stimulated with murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV)-infected macrophages produce IFNγ in a Ly49H-dependent manner (17). However, transfer of wildtype NK cells into a naïve host constitutively expressing the Ly49H ligand m157 as a transgene (m157-Tg) did not result in IFNγ production but rather caused NK cell hypo-responsiveness within 24 hours (18, 19), indicating that additional signals may be required for activation receptor-dependent IFNγ production.

Here we show that activation receptor-mediated IFNγ production by NK cells indeed requires additional signals which can be provided by cytokines such as IL-12 and IFNβ. We found that cytokine signaling induces transcription of Ifng mRNA, whereas Ly49H signaling resulted in translation of Ifng mRNA. Furthermore, efficient IFNγ production required a specific order of these stimuli. Taken together, this study provides a molecular basis for the requirements of NK activation receptor-induced IFNγ production.

Materials and Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 (and congenic CD45.1 C57BL/6) mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. IL-12Rβ2−/− and RAG1−/− mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. DAP12 KI mice were kindly provided by E. Vivier (CNRS-INSERM-Universite de la Mediterranee, France). DAP10−/− mice were kindly provided by M. Colonna. IFNAR1−/− were backcrossed on C57BL/6 background as described previously (20). m157-Tg and Ly49H-deficient B6.BxD8 mice were generated and maintained in-house in accordance with institutional ethical guidelines.

Reagents and cell preparation

Fluorescent-labeled antibodies used were anti-NK1.1 (clone PK136), anti-NKp46 (29A1.4), anti-CD3 (145–2C11), anti-CD19 (eBio1D3), anti-CD45.1 (A20), anti-CD45.2(104), anti-Eomes (Dan11mag), anti-TNFα (MP6-XT22), and anti-IFNγ (XMG1.2), all from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Fluorescent-labeled anti-CD49a (Ha31/8) was purchased form BD Biosciences. Biotinylated anti-Ly49H (3D10) was produced in-house. MG-132(Cell Signaling 2094S), Actinomycin D (Sigma A9415), Cycloheximide (Sigma C7698), CGP-57380 (Sigma C0993), ISRIB (Sigma SML0843), Pyr-41 (Sigma N2915), BMS-345541 (Sigma B9935), Tpl2 kinase inhibitor (Santa Cruz sc-204351), PD90859 (Sigma P215) were used at the indicated concentrations. Where indicated, NK cells were enriched to a purity >90% NK1.1+CD3-CD19- cells, verified by flow cytometry for each experiment, from RAG1−/− splenocytes using CD49b microbeads with LS columns (Miltenyi Biotec) or from C57BL/6 mice using EasySep Mouse NK cell isolation kit (StemCell Technologies) according to manufacturer’s instructions. m157-Tg or WT murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were isolated from day 11.5–13.5 embryos.

In vitro stimulation assays

Freshly isolated splenocytes and liver single cell suspensions were prepared as previously described (21). For antibody stimulations, splenocytes were stimulated with 4μg/ml precoated or soluble antibody against NK1.1 (PK136), Ly49H (3D10), Ly49D (4E4) that were produced in-house, or NKp46 (29A1.4) purchased from Biolegend. IFNβ (800 U/ml; PBL Assay Science) and/or IL-12p70 (25 ng/ml; Peprotech) were added where indicated. For co-culture experiments, splenocytes were co-cultured with congenic CD45.½ or CFSE-labeled m157-Tg or littermate control splenocytes at a 1:1 ratio in the presence of 100–200 U/ml IFNβ or 10–20 ng/ml IL-12p70 where indicated. For experiments with MEFs, splenocytes or purified NK cells were co-cultured with m157-Tg or C57BL/6 MEFs at a 30:1 or a 1:1 ratio respectively. Monensin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added after 1 hour and the culture was stopped 5–8 hours hereafter. Samples were subsequently stained with fixable viability dye (Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by surface staining in 2.4G2 hybridoma supernatant with directly conjugated or biotinylated antibodies that were revealed by streptavidin-PE (BD Biosciences). Samples were then fixed and stained intracellularly using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences) or FOXP3/transcription factor staining buffer set (Thermo Scientific) for Eomes staining according to manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were acquired using FACSCanto (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Treestar). Where indicated, representative sample files were combined after acquisition in concatenated files for visualization purposes. Concatenated files were gated for NK cells, Sample ID versus IFNγ is shown in the generated composite plot. NK cells were defined as Viability-NK1.1+CD3-CD19- or Viability-NKp46+CD3-CD19- and gating for IFNγ were based on unstimulated controls. For RNA flow experiments, splenocytes were stimulated with MEFs, and after antibody staining, they were hybridized with Ifng or control scrambled probe using the prime flow kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantitative PCR

RNA was isolated from purified NK cells after indicated stimulation using Trizol (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Contaminating DNA was removed using Turbo DNAse, and cDNA was synthesized using Superscript III (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Quantification was performed for Ifng (Mm.PT.58.30096391; Integrated DNA Technologies) and Gapdh (Mm99999915_g1; Thermo Fisher Scientific) against plasmid standard curves using TAQman universal master mix II on a StepOnePlus real time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Western blot

Stimulated purified NK cells were lysed in RIPA lysis and extraction buffer in the presence of protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Lysates were denatured in Laemmli sample buffer and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes and probed with antibodies specific for Erk½ (137F5), phospho-Erk½ (Thr202/Tyr204; #9102), NF-ΚB p65 (D14E12), phospho-NF-ΚB p65 (Ser536) (93H1), or β-Actin (#4967), which were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology.

Statistical analysis

Statistically significant differences were determined with unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-tests using Prism (Graphpad). Error bars in figures represent SD and p-values from duplicate or triplicate samples as indicated. All experiments shown are representatives from 2 or more independent experiments.

Results

NK cell activation receptor-dependent IFNγ production requires multiple signals

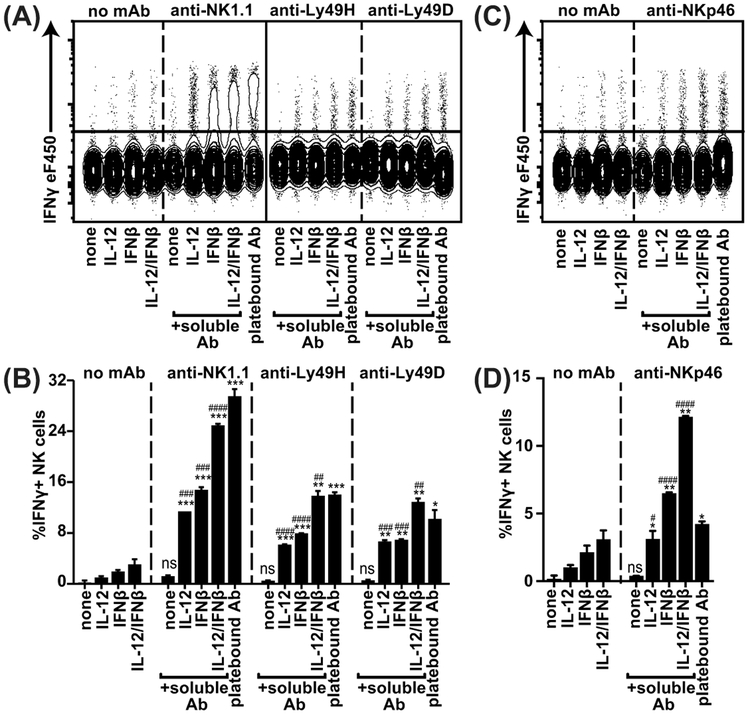

NK cells produce IFNγ in response to stimulation with immobilized plate-bound antibodies against activation receptors such as anti-NK1.1, antiLy49H, anti-Ly49D and anti-NKp46, as shown in composite plots of concatenated representative samples (Figure 1). However, stimulation with soluble antibody alone did not result in significant IFNγ production, suggesting that additional signals are required for IFNγ production. We investigated a potential role for cytokines on activation receptor-mediated IFNγ production, which we and others have previously described to be important for NK cell cytolytic functions during viral infections (6, 20, 22). Stimulation of wildtype (WT) NK cells alone with IL12 and/or IFNβ resulted in low percentages of NK cells producing IFNγ (Figure 1). Strikingly, stimulation of NK cells with soluble anti-NK1.1 in combination with IL12 and IFNβ synergized to induce strong IFNγ production, reaching levels similar to plate-bound antibody (Figure 1A, C). To investigate whether the requirement for multiple signals was applicable to other activation receptors that signal through adaptor molecules other than associated with NK1.1 (FcRγ), we analyzed the response to anti-Ly49H (DAP10/12), anti-Ly49D (DAP10/12), and anti-NKp46 (FcRγ/CD3ζ). Soluble anti-Ly49H, anti-Ly49D, and anti-NKp46 also induced optimal IFNγ production in the presence of IL-12 and IFNβ, suggesting that these receptors have similar requirements. In summary, these results indicate that a wide range of NK activation receptors, signaling through distinct adapter molecules, require synergistic stimulation with cytokines for full IFNγ production.

Figure 1. Soluble antibodies directed against activation receptors are capable of inducing NK cell IFNγ in the presence of IFNβ or IL-12.

Splenocytes from WT mice were stimulated in the presence of soluble or plate-bound antibody and the indicated cytokines. NKp46+ NK cells (A-B) or NK1.1+ NK cells (C-D) were analyzed for IFNγ production. Combined FACS plots of concatenated representative samples are shown in (A, C) and quantification of duplicates is shown in (B,D). Representative experiment of 3 independent experiments is shown. The *-symbols indicate statistical comparison to same condition without antibody, the #-symbols indicate comparison to soluble antibody only within the same group. #### or ****p<0.0001, ### or ***p<0.001, ## or **p<0.01, # or *p<0.05, ns= not significant.

To explore whether the synergy between activation receptor and cytokine stimulation extends to innate lymphoid cells (ILC), we analyzed liver ILC1 for IFNγ and TNFα production in response to anti-NK1.1 under the conditions described above (sFigure 1). ILC1 produced high levels of IFNγ and TNFα in response to plate-bound anti-NK1.1. In contrast to cNK cells ILC1 produced moderate amounts of IFNγ in response to IL-12 alone, which was elevated to some extent by the addition of soluble anti-NK1.1. Taken together, ILC1 cytokine production likely requires distinct mechanisms as compared to cNK cells.

NK cell IFNγ production through stimulation with ligand-expressing cells requires additional signals

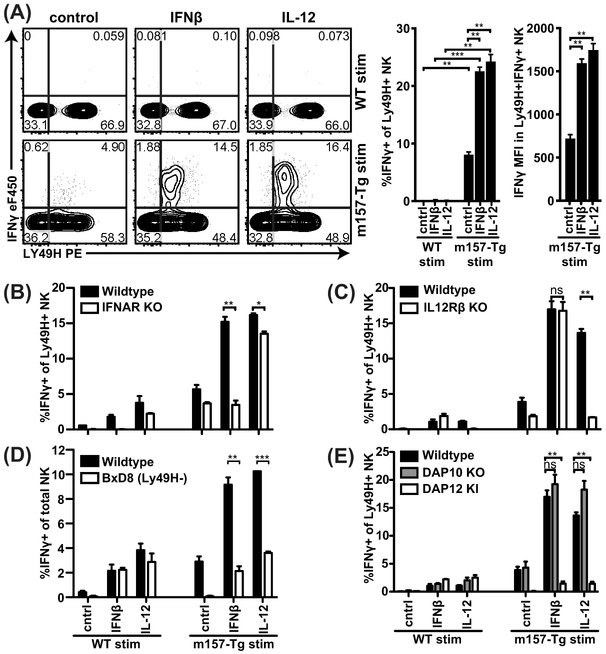

In order to investigate the requirements for activation receptor dependent IFNγ production in the context of activation receptor engagement by ligand rather than antibody cross-linking, we turned to an in vitro model that we previously published (20). Briefly, we stimulated NK cells among freshly isolated splenocytes with freshly isolated m157-Tg or wild type (WT) splenocytes in the presence or absence of cytokines. While Ly49H+ NK cells produce IFNγ in response to MCMV-infected cells, upon recognition of m157 (17, 18), here we observed that Ly49H+ NK cells produced only low levels of IFNγ in response to m157-Tg splenocytes alone in vitro (Figure 2A). These data suggest that in the context of activation receptor engagement by ligand, additional signals are required as well. Indeed, co-culture of NK cells and m157-Tg splenocytes with IFNβ or IL-12 induced substantial levels of IFNγ while stimulation of WT NK cells alone with IFNβ or IL-12 did not (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Ly49H-dependent IFNγ production requires cell-intrinsic cytokine and DAP12 but not DAP10 signaling.

(A) Splenocytes from CD45.2 WT mice were mixed with CD45.½ congenic m157-Tg or WT splenocytes at a 1:1 ratio in the presence of the indicated cytokines. IFNγ production by the CD45.2+ NK cells is shown. (B-E) CD45.2+ Splenocytes deficient for the indicated gene were mixed with congenic CD45.½+ m157Tg or control splenocytes that were not deficient for the indicated genes. Representative experiment of 17 (A), 3 (B), and 2 (C) independent experiments performed in duplicate is shown. ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05, ns= not significant.

To explore whether this cytokine requirement applied to other activation receptors, such as NKG2D, we analyzed NK cell IFNγ production in coculture experiments with SV40-immortalized MEF expressing the NKG2D ligand, Rae1δ (sFigure 2A). Similar to m157-Tg stimulation, NK cells produced more IFNγ upon exposure to Rae1δ-expressing target cells with IFNβ or IL-12. These results strongly suggest that activation receptor engagement by ligand alone is insufficient for optimal IFNγ production and additional signals such as cytokines are required.

To determine if cytokine stimulation acted directly on NK cells, we used mixed cultures involving NK cells deficient in cytokine receptors. When IFNAR-deficient splenocytes were mixed with IFNAR-sufficient m157-Tg or WT splenocytes, IFNAR-deficient NK cells were unable to respond to IFN-I and m157-Tg stimulation but still produced IFNγ in response to IL-12 and m157-Tg targets, indicating that IFNβ acts cell-intrinsically on NK cells (Figure 2B). Conversely, IL-12R-deficient NK cells were unable to respond to IL-12 and IL-12R sufficient m157-Tg splenocytes but did respond to IFNβ and m157-Tg targets (Figure 2C), indicating that IL-12 acts directly on NK cells as well. Furthermore, stimulation of purified NK cells with m157-Tg MEF and cytokines was capable of inducing IFNγ, providing further evidence that these cytokines act directly on NK cells (sFigure 2B).

Interestingly, most IFNγ was produced by Ly49H+ NK cells with lower levels of Ly49H (Figure 2A), suggesting that these cells had directly engaged m157 which modulated Ly49H expression, as previously described (20). To confirm the involvement of Ly49H, we analyzed NK cells from B6.BxD8 mice that selectively lacked Ly49H expression and found that m157-Tg target cells were unable to stimulate IFNγ production even with IFN-I or IL12 (Figure 2D). Since Ly49H has been reported to signal through the signaling adapters DAP10 and DAP12 (11, 23), we investigated which of these molecules was required for Ly49H-dependent IFNγ production by analyzing NK cells deficient in either of these molecules (Figure 2E). DAP10-deficient NK cells were fully capable of producing IFNγ, whereas DAP12-deficient NK cells were unable to produce IFNγ. These data show that signaling through DAP12 but not DAP10 is required for Ly49H-dependent IFNγ production.

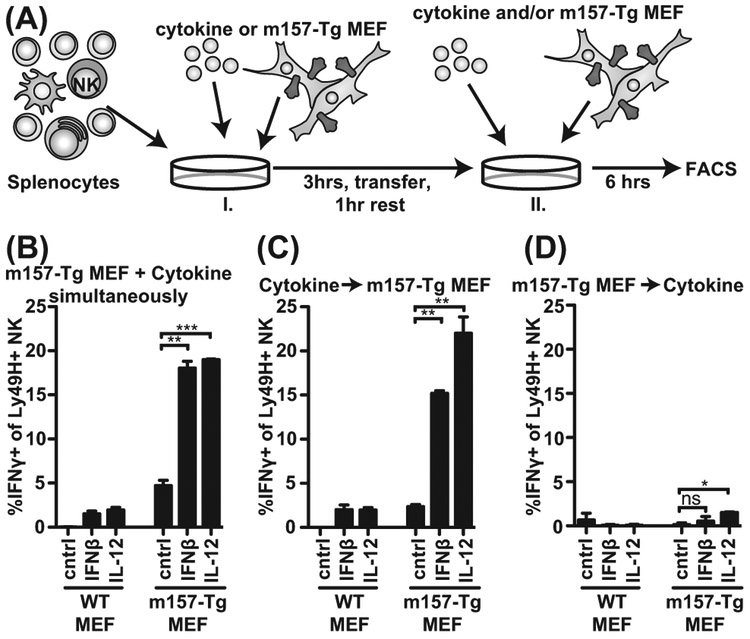

Cytokine signals are required before Ly49H stimulation for optimal IFNγ production

To determine whether cytokine and activation receptor signals were needed simultaneously, we separated cytokine and activation receptor stimulation (Figure 3A). Upon stimulation of NK cells first with cytokine for 3 hours then without cytokine for a 1-hour rest followed by m157-Tg MEF co-culture, we observed IFNγ production similar to stimulation with both cytokines and m157-Tg MEFs throughout the assay (Figure 3B, C). However, when the stimuli were reversed and NK cells were first stimulated with m157-Tg MEF and cytokines second, we did not observe IFNγ production by Ly49H+ NK cells (Figure 3D). These experiments indicate that NK cells do not have to receive cytokine and activation receptor signals simultaneously, but the order by which they receive these signals is important.

Figure 3: Cytokine and activation receptor stimulation is not required simultaneously, but cytokine exposure is needed before activation receptor triggering.

(A) Experimental setup; and (B) IFNγ production after simultaneous stimulation with cytokine and m157-Tg MEF. (C) IFNγ production after pretreatment with cytokine and subsequent stimulation with m157-Tg MEF. (D) IFNγ production after pretreatment with m157-Tg MEF and subsequent stimulation with cytokines. Samples were analyzed as in Figure 2. Representative experiment of 4 independent experiments performed in duplicate is shown. ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05, ns= not significant.

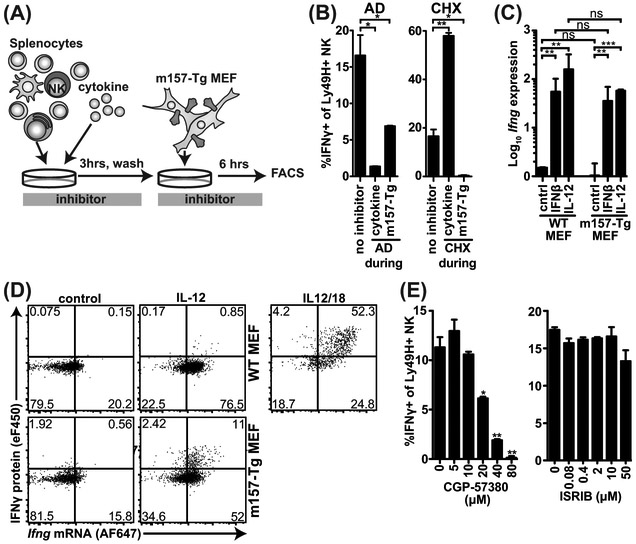

IFNγ production requires transcription during cytokine exposure while translation is required during Ly49H engagement

We assessed the contributions of transcription and translation during cytokine and m157-Tg exposure were assessed (Figure 4A, B). We blocked with either the transcriptional inhibitor actinomycin D (AD) or protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) during each stage. AD exposure during initial cytokine stimulation blocked IFNγ production almost completely, while Ly49H+ NK cells were still able to produce IFNγ when AD was added only during subsequent m157-Tg MEF stimulation (Figure 4B). In contrast, CHX during initial cytokine stimulation did not block IFNγ production while it completely blocked IFNγ production during subsequent m157-Tg stimulation. Taken together, these data suggest that cytokine stimulation induces Ifng transcription, while m157-Tg stimulation induces translation.

Figure 4: IL-12 and IFNβ induce Ifng mRNA whereas signaling through Ly49H initiates IFNγ translation.

(A) Experimental setup. (B) Splenocytes were pretreated with IL-12, hereafter the cells were washed and incubated with m157-Tg MEF in the presence of monensin. During IL-12 (cytokine) or m157-Tg stimulation transcription-inhibitor actinomycin D (AD; 2.5 μg/ml), or translation-inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX; 5 μg/ml) was added. (C) Splenic NK cells were purified by negative selection. 6 hours after stimulation with cytokines and/or m157-Tg MEF RNA was isolated from NK cells. Ifng transcripts were quantified using TAQman qPCR and normalized to Gapdh expression. (D) Purified NK cells were stimulated with IL12 and/or m157-Tg MEF for 6 hours and stained for IFNγ protein and Ifng mRNA using primeflow RNA assay. (E) Splenocytes were pretreated with IL-12, hereafter the cells were washed and stimulated with m157-Tg MEF in the presence of monensin and MNK-1/eIF4 inhibitor CGP-57380 or eIF2 inhibitor ISRIB at the indicated concentration. Representative experiment of 3 independent experiments is shown and each was performed in duplicate (B, E) or triplicate (C). ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05, ns= not significant.

To confirm that cytokine stimulation induces Ifng transcription, we analyzed purified NK cells in response to cytokine and m157-Tg MEF stimulation. Stimulation using purified NK cells resulted in similar IFNγ production as compared to the splenocyte cultures (sFigure 2B). In response to IFNβ or IL-12, Ifng transcripts were increased ~100-fold whereas stimulation with m157-Tg MEF alone did not induce increased Ifng transcript levels in purified NK cells (Figure 4C). The combination of cytokine and m157-Tg MEF resulted in similar Ifng transcripts as with cytokine alone. We used flow cytometry to visualize Ifng mRNA versus IFNγ protein following stimulation with both cytokines and m157-Tg on a single cell level (Figure 4D). Consistent with our quantitative PCR data, we found that IL-12 alone but not m157-Tg MEF alone stimulated Ifng transcription. The combination of IL-12 and m157-Tg MEF did not result in increased Ifng transcript levels compared to IL-12 alone, but NK cells with high Ifng transcript levels produced more IFNγ protein. Incubation with IL-12 and IL-18, which resulted in high Ifng transcript and simultaneous IFNγ protein levels, is shown as a positive control. Thus, cytokine stimulation but not Ly49H activation induces Ifng transcription.

To validate the contribution of IFNγ translation during m157-Tg stimulation, we blocked initiation of translation with inhibitors for 2 potential initiation pathways, i.e., the MNK1-inhibitor CGP57380 for the eIF4 complex and ISRIB for the eIF2 complex. CGP57380 addition during m157-Tg target stimulation prevented IFNγ production in a dose-dependent manner, whereas ISRIB did not (Figure 4E). Neither inhibitor affected NK cell viability at the concentrations used (data not shown). These results suggest that Ly49H-activation initiates IFNγ translation and that the eIF4 but not the eIF2 complex is required. Together, the data presented here indicate that IFNβ or IL-12 induce Ifng transcription, whereas activation receptor stimulation acts post-transcriptionally to induce IFNγ protein production.

Ly49H-dependent IFNγ requires the Proteasome-Ubiquitin-IKK-TPL2 axis

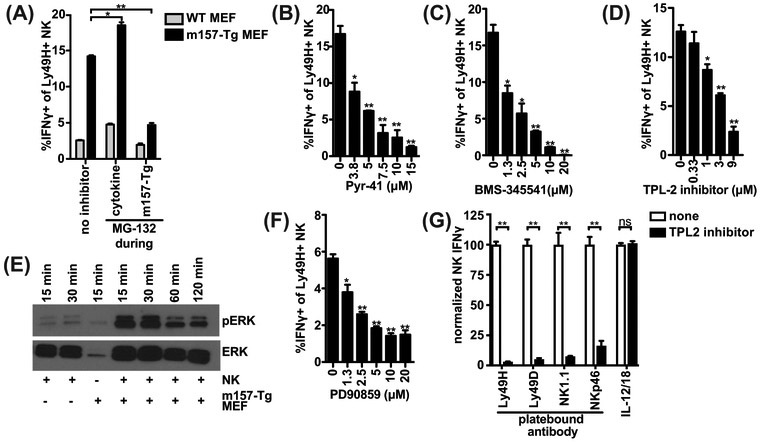

To determine whether IFNγ is produced in response to cytokine stimulation but rapidly degraded by the proteasome, we blocked the proteasome (Figure 5A). Addition of MG-132 during cytokine stimulation did not alter IFNγ induced upon secondary stimulation with WT MEF, suggesting that IFNγ is not continuously degraded by the proteasome during initial cytokine stimulation. Unexpectedly, we observed decreased IFNγ upon MG-132 treatment during subsequent m157-Tg stimulation, indicating that proteasomal degradation was instead required for IFNγ production at the time of Ly49H activation.

Figure 5: Ly49H signaling requires the Proteasome-Ubiquitin-IKK-TPL2-ERK axis to induce IFNγ.

(A) As in Figure 4AB, splenocytes were pretreated with IL-12, hereafter the cells were washed and incubated with m157-Tg MEF in the presence of monensin. During IL-12 (cytokine) or m157-Tg stimulation, the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 (10μM) was added. (B-D,F) as in Figure 4E, splenocytes were pretreated with IL-12, thereafter the cells were washed and stimulated with m157-Tg MEF, in the presence of monensin and E1 inhibitor Pyr-41 (B), IKK-complex inhibitor BMS-345541(C), TPL2 inhibitor (D), or ERK-inhibitor PD90859 (F) at the indicated concentrations. (E) Purified NK cells were pre-stimulated with IL-12, after which the NK cells were stimulated with m157-Tg MEF for the indicated time. ERK and phospho-ERK levels were analyzed by western blot. (G) Splenocytes were stimulated with indicated plate-bound antibody or IL-12 (12.5 ng/ml) and IL-18 (5 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of 9 μM TPL2 inhibitor. Percent of IFNγ producing NK cells were normalized to the condition without inhibitor. Representative experiments of 2 (A, D, E, G) or 3 (B, C, F) independent experiments are shown and were performed in duplicate (A, B, C, F, G) or triplicate (D). **p<0.01, *p<0.05, ns= not significant.

To investigate how proteasomal degradation could be required for IFNγ production we utilized a panel of established inhibitors to examine ubiquitin-dependent signaling pathways requiring the proteasome. To determine involvement of the ubiquitin pathway, we blocked the E1 ubiquitin ligase with Pyr-41 and observed dose-dependent decrease in IFNγ production, suggesting that that ubiquitination is required (Figure 5B). We analyzed if the IKK complex was involved with BMS-345541 that inhibited IFNγ production in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5C). Stimulation of NK cells with m157-Tg cells resulted in modest p65 phosphorylation at early timepoints, suggesting that IFNγ production may be independent of canonical NFΚB (sFigure 2C). The IKK complex has also been implicated in post-transcriptional regulation of TNFα-production by macrophages through activation of TPL2 (24, 25). To investigate whether IFNγ production by NK cells could be similarly regulated, we inhibited TPL2 and detected decreased IFNγ production in a dose-dependent manner, suggesting that Ly49H-signaling through TPL2 is required for IFNγ production (Figure 5D). ERK has been reported to act downstream of TPL2 as well as in a number of immune receptor signaling pathways, indeed we detected NK cell ERK phosphorylation in response to m157-Tg MEF stimulation (Figure 5E). Additionally, blockade of ERK with PD90859 inhibited IFNγ production (Figure 5F). Finally, we analyzed whether this pathway potentially is involved in other means of NK cell stimulation. TPL2 inhibition during stimulation with plate-bound antibodies against NK1.1, Ly49H, Ly49D, and NKp46 resulted in a virtually complete reduction in IFNγ production (Figure 5G and sFigure 2D). Intriguingly, inhibition of TPL2 during stimulation with combination of IL-12 and IL-18 did not result in reduction in IFNγ, even at lower stimulatory cytokine concentrations (sFigure 2E), indicating that it is independent of the TPL2-axis and that the TPL2 inhibitor is not toxic at the concentrations used. Taken together, these data suggest that NK cell IFNγ induced specifically through activation receptors requires the Proteasome-Ubiquitin-IKK-TPL2-ERK axis.

Discussion

While we previously described that dual signaling is required for full NK cytolytic function during MCMV infection (20), herein we uncovered a distinct role for activation receptor-dependent IFNγ production that is regulated at the transcriptional and translational levels. The data presented here support the following model (sFigure 3): Stimulation of NK cells with IFN-I and IL-12 induces Ifng transcription. Subsequently, a second signal through an activation receptor initiates translation of Ifng mRNA into protein. In the case of the DAP12-dependent activation receptor Ly49H, signaling requires the Ubiquitin-IKK-TPL2-MNK1-eIF4 axis to induce IFNγ protein. This pathway likely plays a role downstream of other activation receptors as well, as inhibition of TPL2 blocked IFNγ production in response to anti-NK1.1, anti-Ly49H, and anti-NKp46. Intriguingly, IFNγ in response to IL-12 in combination with IL-18 was not dependent on TPL-2, suggesting that a distinct pathway is involved as compared to activation receptor stimulation.

In this study we found that primary m157-Tg splenocytes and MEFs alone were unable to stimulate robust NK cell IFNγ production. In contrast, cell lines overexpressing m157, such as BAF-m157, are capable of inducing NK cell IFNγ (5, 16, 17). We observed similar expression levels of m157 in m157-Tg MEF and BAF-m157, indicating in both situations the ligand levels are similar. The cell lines overexpressing m157 potentially express additional NK ligands or soluble factors that may bypass the requirement for a second signal. To avoid contributions of such factors, we used primary m157-Tg cells that are the same as WT cells except for transgenic expression of m157.

Resting NK cells have increased Ifng transcript levels compared to naïve T cells as reported in Yeti mice that have the Ifng 3’ UTR replaced by YFP (26). The data presented here suggest that these levels are not enough for optimal activation receptor-dependent IFNγ production. We observed approximately a 100-fold increase in Ifng transcript levels upon treatment with IL-12 or IFNβ, which allowed for IFNγ protein expression upon engagement of Ly49H. Of note, the combination of IL-12 and IL-18 resulted in even higher Ifng transcript levels, presumably partially or completely bypassing the need for activation receptor engagement as shown here. NK cells that are previously exposed to MCMV-infection also have increased Ifng transcripts compared to naïve NK cells as reported in Yeti mice (27), suggesting that target cell recognition by activation receptors without cytokine exposure may be enough for these NK cells to produce IFNγ.

We observed increased IFNγ production upon MG-132 treatment during cytokine stimulation that is followed by m157-Tg stimulation (Figure 5A). Jak2 and STAT4 are downstream of the IL-12 receptor, both these molecules have been described to be degraded by the proteasome as part of negative regulation (28, 29). Thus, blocking the proteasome during cytokine stimulation may potentially lead to sustained cytokine signaling and increased Ifng transcription, which may explain the increase in IFNγ production observed upon MG-132 treatment during cytokine stimulation.

IFNγ production is known to be regulated at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. Transcription is regulated through a number of transcription factors including T-bet and Eomes as well as microRNAs and long non-coding RNAs. The untranslated regions (UTR) have been implicated in post-transcriptional control of IFNγ. The human Ifng 5’UTR contains a pseudoknot that inhibits eIF2-dependent translation through PKR (30). We found a role for eIF4 and not eIF2 for NK cell IFNγ production, suggesting that the observed IFNγ is independent of the pseudoknot. However, deletion of the Ifng 3’ UTR increased IFNγ-producing NK and T cells treated with IL-12 (31), indicating that the Ifng 3’ UTR may play another important role in post-transcriptional control of IFNγ production. The ARE-binding protein ZFP36L2 has recently been identified to bind to the Ifng 3’ UTR in T cells, thereby repressing its translation (32). Our data are consistent with a translational repressor that is released upon activation receptor signaling and perhaps ZFP36L2 may regulate NK IFNγ production as well. Yet unclear is how receptor activation signals would relieve ZFP36L2 from its putative repression of IFNγ translation.

We observed increased IFNγ production upon CHX treatment during cytokine stimulation followed by m157-Tg stimulation (Figure 4B), CHX treatment potentially resulted in decreased levels of molecules that negatively regulate IFNγ production under normal conditions. For example, blocking protein production of ZFP36L2, suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS1), and/or downstream regulatory element antagonist modulator (DREAM) (33) may cause or contribute to increased IFNγ production upon CHX treatment during cytokine stimulation.

TPL-2 has been shown to be involved in post-transcriptional control of TNFα production (24). TPL-2 can be activated by IΚB-dependent ubiquitination and degradation of p105 (25). Our data using established inhibitors blocking the proteasome, E1 ubiquitin ligase, IΚK, and TPL-2 suggest that this pathway may also be involved in Ly49H-dependent IFNγ production. Although inhibitors were used here to outline the Proteasome-Ubiquitin-IKK-TPL2 axis, these pathways have been well established in other systems where inhibitors have been validated. However, follow-up studies with mice (conditionally) deficient in key players will be required to confirm these findings. TPL2-deficient CD4+ T cells are defective in producing IFNγ and controlling Toxoplasma gondii (34), suggesting that IFNγ may be regulated by TPL2 in a similar fashion to TNFα.

In conclusion, we uncovered a stepwise initiation process of NK cell IFNγ transcription versus translation by cytokines and activation receptors as well as by proteasome degradation. These pathways are likely to be subject to regulation at multiple points, potentially allowing for specific IFNγ production during pathogenic infections and tumor surveillance while preventing autoimmunity and immunopathology.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Natural Killer activation receptor-dependent IFNγ requires additional signals

Cytokine, but not activation receptor stimulation induces Ifng transcription

Activation receptor ligation stimulates IFNγ translation through TPL2

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant R01-AI131680 to W.M.Y. and S.J.P. was supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (Rubicon grant 825.11.004).

Abbreviations used in this article:

- AD

actinomycin D

- CHX

cycloheximide

- ILC

innate lymphoid cells

- MCMV

murine cytomegalovirus

- m157-Tg

m157-transgenic

- NK

natural killer

- UTR

untranslated region

- WT

wild type

References

- 1.Long EO, Kim HS, Liu D, Peterson ME, and Rajagopalan S. 2013. Controlling natural killer cell responses: integration of signals for activation and inhibition. Annu Rev Immunol 31: 227–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman BE, Raue HP, Hill AB, and Slifka MK. 2015. Cytokine-Mediated Activation of NK Cells during Viral Infection. J Virol 89: 7922–7931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orange JS, and Biron CA. 1996. Characterization of early IL-12, IFN-alphabeta, and TNF effects on antiviral state and NK cell responses during murine cytomegalovirus infection. J Immunol 156: 4746–4756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loh J, Chu DT, O’Guin AK, Yokoyama WM, and Virgin H. W. t.. 2005. Natural killer cells utilize both perforin and gamma interferon to regulate murine cytomegalovirus infection in the spleen and liver. J Virol 79: 661–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fodil N, Langlais D, Moussa P, Boivin GA, Di Pietrantonio T, Radovanovic I, Dumaine A, Blanchette M, Schurr E, Gros P, and Vidal SM. 2014. Specific dysregulation of IFNgamma production by natural killer cells confers susceptibility to viral infection. PLoS Pathog 10: e1004511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen KB, Salazar-Mather TP, Dalod MY, Van Deusen JB, Wei XQ, Liew FY, Caligiuri MA, Durbin JE, and Biron CA. 2002. Coordinated and distinct roles for IFN-alpha beta, IL-12, and IL-15 regulation of NK cell responses to viral infection. J Immunol 169: 4279–4287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pien GC, Satoskar AR, Takeda K, Akira S, and Biron CA. 2000. Cutting edge: selective IL-18 requirements for induction of compartmental IFN-gamma responses during viral infection. J Immunol 165: 4787–4791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takeda K, Nakayama M, Sakaki M, Hayakawa Y, Imawari M, Ogasawara K, Okumura K, and Smyth MJ. 2011. IFN-gamma production by lung NK cells is critical for the natural resistance to pulmonary metastasis of B16 melanoma in mice. J Leukoc Biol 90: 777–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith HR, Chuang HH, Wang LL, Salcedo M, Heusel JW, and Yokoyama WM. 2000. Nonstochastic coexpression of activation receptors on murine natural killer cells. J Exp Med 191: 1341–1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim S, Poursine-Laurent J, Truscott SM, Lybarger L, Song YJ, Yang L, French AR, Sunwoo JB, Lemieux S, Hansen TH, and Yokoyama WM. 2005. Licensing of natural killer cells by host major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. Nature 436: 709–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orr MT, Sun JC, Hesslein DG, Arase H, Phillips JH, Takai T, and Lanier LL. 2009. Ly49H signaling through DAP10 is essential for optimal natural killer cell responses to mouse cytomegalovirus infection. J Exp Med 206: 807–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.May RM, Okumura M, Hsu CJ, Bassiri H, Yang E, Rak G, Mace EM, Philip NH, Zhang W, Baumgart T, Orange JS, Nichols KE, and Kambayashi T. 2013. Murine natural killer immunoreceptors use distinct proximal signaling complexes to direct cell function. Blood 121: 3135–3146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho EL, Carayannopoulos LN, Poursine-Laurent J, Kinder J, Plougastel B, Smith HR, and Yokoyama WM. 2002. Costimulation of multiple NK cell activation receptors by NKG2D. J Immunol 169: 3667–3675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bryceson YT, March ME, Ljunggren HG, and Long EO. 2006. Synergy among receptors on resting NK cells for the activation of natural cytotoxicity and cytokine secretion. Blood 107: 159–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fauriat C, Long EO, Ljunggren HG, and Bryceson YT. 2010. Regulation of human NK-cell cytokine and chemokine production by target cell recognition. Blood 115: 2167–2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diefenbach A, Jamieson AM, Liu SD, Shastri N, and Raulet DH. 2000. Ligands for the murine NKG2D receptor: expression by tumor cells and activation of NK cells and macrophages. Nat Immunol 1: 119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith HR, Heusel JW, Mehta IK, Kim S, Dorner BG, Naidenko OV, Iizuka K, Furukawa H, Beckman DL, Pingel JT, Scalzo AA, Fremont DH, and Yokoyama WM. 2002. Recognition of a virus-encoded ligand by a natural killer cell activation receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99: 8826–8831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tripathy SK, Keyel PA, Yang L, Pingel JT, Cheng TP, Schneeberger A, and Yokoyama WM. 2008. Continuous engagement of a self-specific activation receptor induces NK cell tolerance. J Exp Med 205: 1829–1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bolanos FD, and Tripathy SK. 2011. Activation receptor-induced tolerance of mature NK cells in vivo requires signaling through the receptor and is reversible. J Immunol 186: 2765–2771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parikh BA, Piersma SJ, Pak-Wittel MA, Yang L, Schreiber RD, and Yokoyama WM. 2015. Dual Requirement of Cytokine and Activation Receptor Triggering for Cytotoxic Control of Murine Cytomegalovirus by NK Cells. PLoS Pathog 11: e1005323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sojka DK, Plougastel-Douglas B, Yang L, Pak-Wittel MA, Artyomov MN, Ivanova Y, Zhong C, Chase JM, Rothman PB, Yu J, Riley JK, Zhu J, Tian Z, and Yokoyama WM. 2014. Tissue-resident natural killer (NK) cells are cell lineages distinct from thymic and conventional splenic NK cells. Elife 3: e01659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fehniger TA, Cai SF, Cao X, Bredemeyer AJ, Presti RM, French AR, and Ley TJ. 2007. Acquisition of murine NK cell cytotoxicity requires the translation of a pre-existing pool of granzyme B and perforin mRNAs. Immunity 26: 798–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sjolin H, Tomasello E, Mousavi-Jazi M, Bartolazzi A, Karre K, Vivier E, and Cerboni C. 2002. Pivotal role of KARAP/DAP12 adaptor molecule in the natural killer cell-mediated resistance to murine cytomegalovirus infection. J Exp Med 195: 825–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dumitru CD, Ceci JD, Tsatsanis C, Kontoyiannis D, Stamatakis K, Lin JH, Patriotis C, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Kollias G, and Tsichlis PN. 2000. TNF-alpha induction by LPS is regulated posttranscriptionally via a Tpl2/ERK-dependent pathway. Cell 103: 1071–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beinke S, Robinson MJ, Hugunin M, and Ley SC. 2004. Lipopolysaccharide activation of the TPL-2/MEK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade is regulated by IkappaB kinase-induced proteolysis of NF-kappaB1 p105. Mol Cell Biol 24: 9658–9667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stetson DB, Mohrs M, Reinhardt RL, Baron JL, Wang ZE, Gapin L, Kronenberg M, and Locksley RM. 2003. Constitutive cytokine mRNAs mark natural killer (NK) and NK T cells poised for rapid effector function. J Exp Med 198: 1069–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun JC, Beilke JN, and Lanier LL. 2009. Adaptive immune features of natural killer cells. Nature 457: 557–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ungureanu D, Saharinen P, Junttila I, Hilton DJ, and Silvennoinen O. 2002. Regulation of Jak2 through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway involves phosphorylation of Jak2 on Y1007 and interaction with SOCS-1. Mol Cell Biol 22: 3316–3326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanaka T, Soriano MA, and Grusby MJ. 2005. SLIM is a nuclear ubiquitin E3 ligase that negatively regulates STAT signaling. Immunity 22: 729–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ben-Asouli Y, Banai Y, Pel-Or Y, Shir A, and Kaempfer R. 2002. Human interferon-gamma mRNA autoregulates its translation through a pseudoknot that activates the interferon-inducible protein kinase PKR. Cell 108: 221–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hodge DL, Berthet C, Coppola V, Kastenmuller W, Buschman MD, Schaughency PM, Shirota H, Scarzello AJ, Subleski JJ, Anver MR, Ortaldo JR, Lin F, Reynolds DA, Sanford ME, Kaldis P, Tessarollo L, Klinman DM, and Young HA. 2014. IFN-gamma AU-rich element removal promotes chronic IFN-gamma expression and autoimmunity in mice. J Autoimmun 53: 33–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salerno F, Engels S, van den Biggelaar M, van Alphen FPJ, Guislain A, Zhao W, Hodge DL, Bell SE, Medema JP, von Lindern M, Turner M, Young HA, and Wolkers MC. 2018. Translational repression of pre-formed cytokine-encoding mRNA prevents chronic activation of memory T cells. Nat Immunol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fenimore J, and A. Y. H 2016. Regulation of IFN-gamma Expression. Adv Exp Med Biol 941: 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watford WT, Hissong BD, Durant LR, Yamane H, Muul LM, Kanno Y, Tato CM, Ramos HL, Berger AE, Mielke L, Pesu M, Solomon B, Frucht DM, Paul WE, Sher A, Jankovic D, Tsichlis PN, and O’Shea JJ. 2008. Tpl2 kinase regulates T cell interferon-gamma production and host resistance to Toxoplasma gondii. J Exp Med 205: 2803–2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.