Abstract

Objective

ApoC-III glycosylation can predict cardiovascular disease risk. Higher abundance of disialylated (apoC-III2) over monosialylated (apoC-III1) glycoforms is associated with lower plasma triglyceride levels. Yet, it remains unclear whether apoC-III glycosylation impacts TRL clearance and whether apoC-III antisense therapy (volanesorsen) affects distribution of apoC-III glycoforms.

Approach and Results

To measure the abundance of human apoC-III glycoforms in plasma over time, human TRLs were injected into wild-type mice and mice lacking hepatic TRL clearance receptors, namely heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG) or both low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) and LDLR-related protein 1 (LRP1). ApoC-III was more rapidly cleared in absence of HSPG (t1/2= 21.1 min) than in wild-type animals (t1/2= 53.5 min). In contrast, deficiency of LDLR and LRP1 (t1/2= 52.4 min) did not affect clearance of apoC-III. After injection, a significant increase in the relative abundance of apoC-III2 was observed in HSPG-deficient mice while the opposite was observed in mice lacking LDLR and LRP1. In patients, abundance of plasma apoC-III glycoforms was assessed after placebo or volanesorsen administration. Volanesorsen treatment correlated with a statistically significant 1.4-fold increase in the relative abundance of apoC-III2 and a 15% decrease in that of apoC-III1. The decrease in relative apoC-III1 abundance was strongly correlated with decreased plasma triglyceride levels in patients.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that HSPGs preferentially clear apoC-III2. In contrast, apoC-III1 is more effectively cleared by LDLR/LRP-1. Clinically, the increase in the apoC-III2/apoC-III1 ratio upon antisense lowering of apoC-III might reflect faster clearance of apoC-III1 as this metabolic shift associates with improved triglyceride levels.

Keywords: Triglycerides, apolipoprotein, glycoprotein, mass spectrometry, Lipids and lipoprotein metabolism, Lipids and Cholesterol, Metabolism, Genetically Altered and Transgenic Models, Treatment, Clinical Study

INTRODUCTION

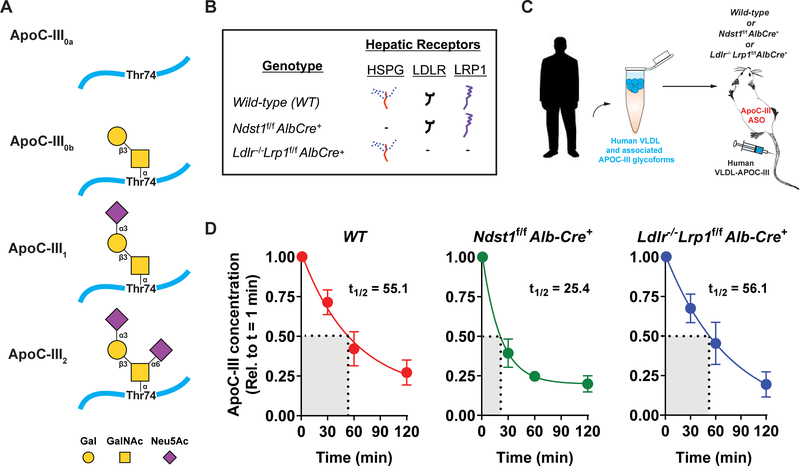

Hypertriglyceridemia is a complex polygenetic trait with multiple causal factors that affects 27% of the general population. One of these factors is apolipoprotein C-III (apoC-III), an 8.8-kDa glycoprotein mainly produced in the liver and to a lesser extent in the intestine.1 It is secreted as a unique glycoprotein devoid of N-glycosylation but having a single core 1 O-N-Acetyl-galactosamine (GalNAc) in a β−3 linkage to galactose (Gal) (Galβ1–3GalNAc) attached to threonine 74 (Fig. 1A). The terminal GalNAc can be modified by up to two sialic acids via α−3 or α−6 linkages to the terminal galactose. Among the multiple apoC-III glycoforms the most abundant forms are apoC-III0, apoC-III1, and apoC-III2, which contain zero, one, and two sialic acid molecules (Fig. 1A), respectively.2–4 Furthermore, non-sialylated apoC-III0 exists as the native (apoC-III0a) and the glycosylated but non-sialylated (apoC-III0b) glycoforms.2 Once secreted, apoC-III is found on triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TRLs) such as chylomicrons and very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) as well as low-density lipoproteins (LDL) and high-density lipoproteins (HDL).1

Figure 1: Changes in human apoC-III concentrations in murine plasma after human TRL injection.

(A) Overview of the most abundant apoC-III glycoforms which are modified with zero (apoC-III0a, apoC-III0b), one (apoC-III1) or two sialic acid molecules (apoC-III2). Gal, galactose; GalNAc, N-acetylgalactosamine; Neu5Ac, N-acetylneuraminic acid. (B) Mutant mice and their representative expression of hepatic TRL-clearance receptors HSPG, Ldlr, and Lrp1. (C) Human VLDL, isolated by ultracentrifugation, was intravenously injected into various mice strains treated with murine apoC-III ASO for 4 weeks (50 mg/kg bodyweight) prior to the experiment. Blood was drawn from the tail and apoC-III concentration and glycosylation status were assessed by ELISA and mass spectrometric immunoassay, respectively. (D) Human apoC-III concentrations in plasma of wild-type (n = 7, WT), Ndst1f/f Alb-Cre+ (n = 7), and Ldlr−/− Lrp1f/f Alb-Cre+ (n = 5) mice 1, 30, 60 and 120 min post-injection showed statistically significant decreases over time in all mouse types (p < 0.001), and the changes significantly differed among the mouse groups (p = 0.04). ApoC-III was cleared much faster in the HSPG deficient mice (t1/2 = 25.4 ± 5.7 min) compared to WT (t1/2 = 55.1 ± 14.8 min) animals but slower in comparison to Ldlr−/−Lrp1f/f Alb-Cre+ mice (t1/2 = 56.1 ±16.3), values represent mean ± SEM.

A growing body of clinical and genetic studies have established that elevated levels of plasma triglyceride (TG) levels represent an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease.5,6 Furthermore, clinical studies found positive correlations between circulating plasma TG levels and circulating apoC-III concentrations and between the latter and cardiovascular disease.7–10 The importance of apoC-III in TRL metabolism was confirmed initially in mice with transgenic expression of human APOC3, which resulted in hypertriglyceridemia, and in ApoC3-deficient mice, which presented with hypotriglyceridemia. In humans this correlation was confirmed by the finding that APOC3-inactivating mutations were shown to be associated with lower plasma TG levels11 and reduced cardiovascular disease risk.8,9,12 In a recent phase II and III placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial, decreased apoC-III synthesis using volanesorsen, an antisense oligonucleotide (ASO), over 13 weeks resulted in dose-dependent and prolonged decreases in both plasma apoC-III and TG levels.13 The FDA dd not yet approved Volanesorsen for the treatment of Familial Chylomicronemia Syndrome patients due to safety concerns, which are currently being addressed. In contrast to apoC-III lowering therapy, elevated circulating apoC-III levels are associated with hypertriglyceridemia as observed in obese and type-2 diabetic patients.14–18

Using a high-throughput mass spectrometric immunoassay (MSIA) we reported that the correlation between apoC-III and TG levels goes well beyond their concentrations as we found a consistent association between apoC-III glycosylation status and plasma TG levels. In three independent cohorts of obese participants having either no diabetes, type-2 diabetes, or impaired glucose tolerance we demonstrated that apoC-III1 had a stronger association with elevated plasma TG levels than apoC-III2.2,19 Higher ratio of apoC-III2 to apoC-III1 was associated with lower TG levels in both cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis.19 We also found that relative abundances of apoC-III0 and apoC-III1, but not apoC-III2, were associated with changes in plasma levels of small dense LDL and TG levels after weight loss or a high carbohydrate diet.20

Evidence exists for multiple mechanisms that could explain the positive association between circulating apoC-III and TG levels, including apoC-III mediated inhibition of lipoprotein lipase-mediated lipolysis21,22,23 and promotion of hepatic very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) secretion.24,25 However, recent studies in mice and humans have established that apoC-III also has an important inhibitory impact on hepatic clearance of TRLs mediated by the LDL receptor (LDLR) and LDLR-related protein 1 (LRP1).26–28 It is unclear how glycosylation of apoC-III can impact TRL metabolism. Neither secretion of apoC-III-containing particles nor preference of apoC-III for binding to one size of lipoprotein over another is affected by its glycosylation status.29 However, the study indicating a lack of these effects of glycosylation was performed in vitro; therefore, they cannot be entirely excluded because in vivo studies might produce different results than cell models. In type-2 diabetes patients, disialylation of apoC-III increased binding of LDL-associated apoC-III to biglycan, a chondroitin or dermatan sulfate proteoglycan that is abundantly present in the arterial wall.30 It was also demonstrated that apoC-III2 and apoC-III1 had differing capacities to inhibit hepatic receptor-mediated TRL uptake.19,31 The liver surface heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG) Syndecan-1 (SDC1) along with LDLR and LRP-1 are the main receptors via which TRL remnants in the liver are cleared.32,33 SDC1 mediates catabolism more slowly and clears smaller TRL particles preferentially compared to LDLR and LRP1.34–36 Furthermore, unlike catabolism by LDLR/LRP1, hepatic TRL catabolism by SDC1 is not accelerated by depletion of murine apoC-III from TRLs.27 It remains unclear, however, whether or not this process is affected by glycosylation status, as murine apoC-III lacks glycosylation due to the absence of a binding site on murine apoC-III for sialic acid transferases.37,38

In this study we set out to test whether differences in apoC-III glycosylation impact the capacity of TRLs to be cleared by the major hepatic lipoprotein clearance receptors. We hypothesized that glycosylation of apoC-III would alter its clearance from the circulation. We anticipated that apoC-III2 would be cleared at a slower rate because of its previously reported increased affinity for proteoglycans. Therapeutically lowering apoC-III concentrations and examining the relative plasma abundances of apoC-III1 and apoC-III2 could provide additional insight into receptor dynamics on clearance of the different apoC-III glycoforms. Lowering of total apoC-III can result in an increased plasma apoC-III2/apoC-III1 ratio due to the delayed clearance of apoC-III2 compared to apoC-III1, which would become more profound under conditions with limited apoC-III production. We tested this hypothesis by injecting mice expressing different hepatic receptors with human TRLs and assessing relative abundances and concentrations of apoC-III glycoforms at baseline and at 30, 60, and 120 min following injection. In humans, we evaluated the relative abundances of apoC-III2 and apoC-III1 before and after ASO-mediated inhibition of apoC-III in the volanesorsen trial.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Disclosure statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Mice

Lrp1f/f, Ldlr−/−, and Alb-Cre+ mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Ndst1f/fAlb-Cre+ mice were generated and genotyped as described.39,40 The generation of Ldlr−/−Lrp1f/fAlb-Cre+ mice is described in Foley et al.33 Cell-specific gene knockout introduced with the Cre recombinase under control of the albumin promoter was validated previously.33 Altering HSPG receptor activity by Ndst1 inactivation or knockout of Ldlr and Lrp1 did not result in any compensatory changes by the remaining receptors.33 The animal studies were performed on different days and, to exclude any influence by sex we opted to use one sex only, i.e. male mice in the current study as no sex difference were observed in previous studies for correlations between apoC-III glycosylation and TG metabolism.2,19,20,27,41 All animals were fully backcrossed on C57Bl/6 background. All animals were housed and bred in vivaria approved by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care located in the School of Medicine, UCSD, following standards and procedures approved by the UCSD Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were weaned at 3 weeks, maintained on a 12-hour light cycle, and fed ad libitum with water and standard rodent diet (PicoLab® Rodent Diet 20 5053). Mice received via intraperitoneal injections ION 440726 (murine apoC-III ASO) at 50 mg/kg/week.

TRL in vivo study

Male mice were administered apoC-III ASO for 2 weeks. Human VLDL particles were isolated from plasma of a single normolipidemic donor by ultracentrifugation at 45,000 x g overnight. After mice were fasted for 5 h, human VLDL (50 μg) was injected intravenously. Plasma was collected by tail bleeding at time points 1, 30, 60 and 120 min after injection.

ELISA

Total human apoC-III concentrations were measured using a sandwich ELISA protocol modified from Fredenrich et al.42 Briefly, human plasma samples were diluted 5000-fold and mouse plasma samples were diluted 1000- to 20,000-fold (dilutions were chosen for each sample based on repeated ELISA readings at different dilutions) in PBS, 0.1% BSA, 0.05% Tween-20 (dilution buffer) and added to wells that had been coated with goat anti-human apoC-III antibody from Academy Biomedical and blocked with PBS containing 0.1% BSA. ApoC-III standard was purchased from Athens Research and Technology, serially diluted in dilution buffer, and plated alongside samples. Next, wells were treated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human apoC-III antibody from Academy Biomedical. The ELISA is specific for human samples and shows no cross-reactivity for murine apoC-III. Color development was achieved by freshly prepared substrate solution (made from the two components of the TMB Microwell Peroxidase Substrate System purchased from KPL) and subsequently stopped by TMB Stop Solution (from SeraCare). Absorbance was measured at 450 nm with a microplate reader (Spectramax M2) and a linear standard curve solved for standard absorbance that fell on a line when plotted against concentrations. Concentrations were calculated for samples whose absorbances landed within this linear range.

Mass Spectrometric Immunoassay (MSIA)

The relative abundances of apoC-III glycoforms were measured by MSIA as previously described.2 In short, after thawing on ice, samples were centrifuged for 5 min at 3,000 rpm. Human plasma samples were diluted 120-fold, mouse plasma samples 1.67- to 5-fold, in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20. Using immunoaffinity columns derivatized with anti-apoC-III antibody (Academy Biomedical Co, Houston, TX), apoC-III protein was captured from the analytical samples during repeated aspiration and dispensing cycles. Captured proteins were then eluted directly onto a 96-well formatted matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) target using a sinapinic acid matrix solution (33% aqueous acetonitrile and 0.4% trifluoroacetic acid saturated with sinapinic acid). Linear mass spectra were acquired from each sample spot using a Bruker’s Ultraflex III MALDI-TOF instrument (Bruker, Billerica, MA) in positive ion mode. Mass spectra were internally calibrated using protein calibration standard-I and further processed with Flex Analysis 3.0 software (Bruker Daltonics). All peaks representing apolipoproteins and their proteoforms, along with a lysozyme (internal reference standard) peak, were integrated baseline-to-baseline using Zebra 1.0 software (Intrinsic Bioprobes Inc.), and the obtained peak area values were tabulated. To distinguish between noise and low intensity signals, the peak areas were corrected individually with baseline noise-bin signals. The corrected apolipoprotein peak areas were then divided by the lysozyme peak area. Relative abundance of each apoC-III proteoform was expressed as relative peak area (RPA). The concentration of each glycoform was obtained by multiplying the RPA obtained by MSIA with total apoC-III concentrations measured by ELISA for the murine study and rate nephelometry for the human study.

Heparin-Sepharose Chromatography

Human VLDL (800 μg) was applied to a 1 mL HiTrap heparin-Sepharose column (GE Healthcare) and eluted with a stepwise salt gradient from 150 mM to 1 M NaCl at pH 7.4 (Tris buffer). The conductivity measurements at the peak of the elution were converted to the respective NaCl concentrations. Pooled fractions were analyzed by MSIA as described above to determine the apoC-III2 to apoC-III1 ratio at different salt concentrations.

Clinical study

This exploratory analysis was performed on a subset of samples from a phase 2 study, in which volanesorsen was evaluated in patients with hypertriglyceridemia (registered as NCT01529424 in clinicaltrials.gov). The volanesorsen study was approved by the IRB at Chicoutimi Hospital in Quebec and by an independent ethics committee (Quorum Review IRB, Seattle). All participants gave written informed consent before enrollment. 17 plasma samples were obtained after overnight fast from participants randomized into either 300 mg of volanesorsen or placebo, respectively (n=11 participants in the treatment group and n=6 in the control group). Patients who were not receiving TG-lowering therapy were considered eligible if they had fasting TG levels between 350 and 2000 mg/dL. Patients who were receiving a stable dose of fibrate were eligible if they had fasting TG levels between 225 and 2000 mg/dL. The study drug was administered as a single subcutaneous injection once a week for 13 weeks. Samples were collected at baseline and on day 85 of the post-treatment follow-up period. Total plasma apoC-III, TG, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol (precipitated), and LDL cholesterol (isolated by ultracentrifugation) were determined at MedPace Reference Labs (Cincinnati, OH). TG and total cholesterol concentrations were measured by standard enzyme-based colorimetric assays. Total apoC-III was measured by rate nephelometry.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism software (version 5, GraphPad Software) and R program (version 3.3, R Core Team). Normality was tested via Shapiro-Wilk test and F-tests were performed to analyze equal variances. Data that passed both tests were analyzed by two-tailed Student’s t-test for two-group comparisons and two-way ANOVA for comparison of multiple groups (> 2) and variables followed by Fisher Least Significant Difference post hoc testing. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. The half-life of apoC-III in plasma was determined by nonlinear interpolation of pooled data. In the human study, the difference in the outcome variables from baseline was computed and the difference between the two treatment groups as a function of the difference in TG levels was compared using linear regression model. Difference in TG levels was also correlated with the difference in apoC-III glycoforms using a Pearson correlation coefficient.

RESULTS

Lack of liver HSPG expression accelerates clearance of TRL-associated human apoC-III

Previous studies revealed a stronger association between plasma TG levels and monosialylated apoC-III (apoC-III1) concentrations than between plasma TG levels and disialylated apoC-III (apoC-III2) levels.2,19 In order to study the impact of apoC-III glycosylation on TRL clearance mediated by LDLR, LRP1 and the HSPG receptor SDC1, we injected human TRLs (50 μg) into wild-type (WT) mice, mice lacking functional liver HSPG receptor SDC1 (Ndst1f/f Alb-Cre+) and mice lacking Ldlr and Lrp1 (Ldlr−/−Lrp1f/fAlb-Cre+) (Fig. 1B). Mice were administered apoC-III ASO for 4 weeks prior to the experiment to reduce interference of murine apoC-III in the analyses (Fig. 1C).37,38 Human apoC-III levels were measured at baseline (1 min) and at 30, 60 and 120 min post injection. ApoC-III concentrations significantly decreased (p < 0.001) over time in all groups, dropping on average from 14.6 to 2.2 μg/mL (Supplemental Figure I). In WT mice, the half-life of apoC-III in plasma was 55.1 ± 14.8 min (Fig. 1D). In contrast, the apoC-III clearance was accelerated in Ndst1f/f Alb-Cre+ mice (t1/2 = 25.4 ± 5.7 min) indicating that most of the apoC-III was rapidly cleared in the absence of hepatic Ndst1 expression. In Ldlr−/−Lrp1f/fAlb-Cre+ mice the clearance rate was much slower (t1/2 = 56.1 ± 16.3 min) than in Ndst1f/f Alb-Cre+ mice, but interestingly very similar to that of WT mice.

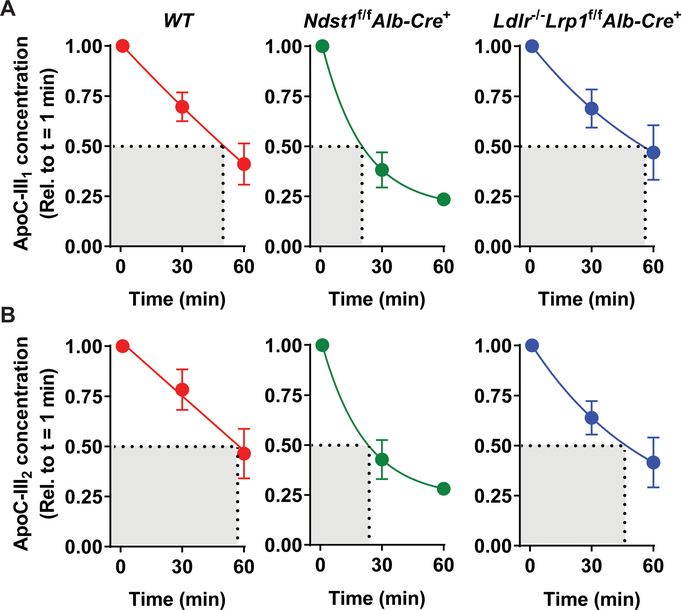

Loss of LDLR and LRP1 reduces clearance of TRLs enriched for monosialylated apoC-III

To further study the impact of apoC-III on TRL metabolism we measured the change in relative concentrations (relative to t = 1 min) of the mono- and disialylated glycoforms, as shown in Fig. 1A, in the different mouse models using our established MSIA method2 (Fig. 2). We could not resolve the glycoforms 120 min after injection due to undetectably low levels and thus measurements are shown for baseline (1 min) and 30- and 60-min post-injection. Comparison of clearance rates of individual glycoforms across mouse models presented similar conclusions to those from total apoC-III measurements. ApoC-III glycoforms in Ndst1f/f Alb-Cre+ mice cleared faster compared to WT (p = 0.002) and Ldlr−/−Lrp1f/fAlb-Cre+ mice (p = 0.0061). Analyzing the difference between glycoforms within each mouse model revealed further insights (Fig. 2A–B). The changes in apoC-III1 (p = 0.02) kinetics were significantly different across all mouse genotypes but this was not the case for apoC-III2 (p = 0.2). In WT mice there was no significant difference between the clearance rates of apoC-III1 and of apoC-III2 (p = 0.49; Fig. 2A–B). Ndst1f/fAlb-Cre+ mice presented with an accelerated clearance rate of apoC-III1-enriched TRLs compared to apoC-III2-enriched TRLs (p = 0.07). The opposite trend was observed in Ldlr−/−Lrp1f/fAlb-Cre+ mice as apoC-III1-enriched TRLs were cleared from the circulation slightly more slowly, but not significantly so, than apoC-III2-enriched TRLs (Fig. 2A–B) (p = 0.32). Overall, the results suggest that different hepatic clearance receptors have differential clearance of apoC-III1.

Figure 2: Changes in apoC-III1 and apoC-III2 concentrations.

Human apoC-III was injected into WT (n = 7), Ndst1f/f Alb-Cre+ (n = 7), and Ldlr−/−Lrp1f/f Alb-Cre+ mice (n = 5) on apoC-III ASO (50 mg/kg bodyweight). Both apoC-III1 (A) and apoC-III2 (B) concentrations significantly decreased with time (p < 0.001). ApoC-III concentrations were normalized to baseline. The time and mouse group effects were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA. Data presented are means ± SEM.

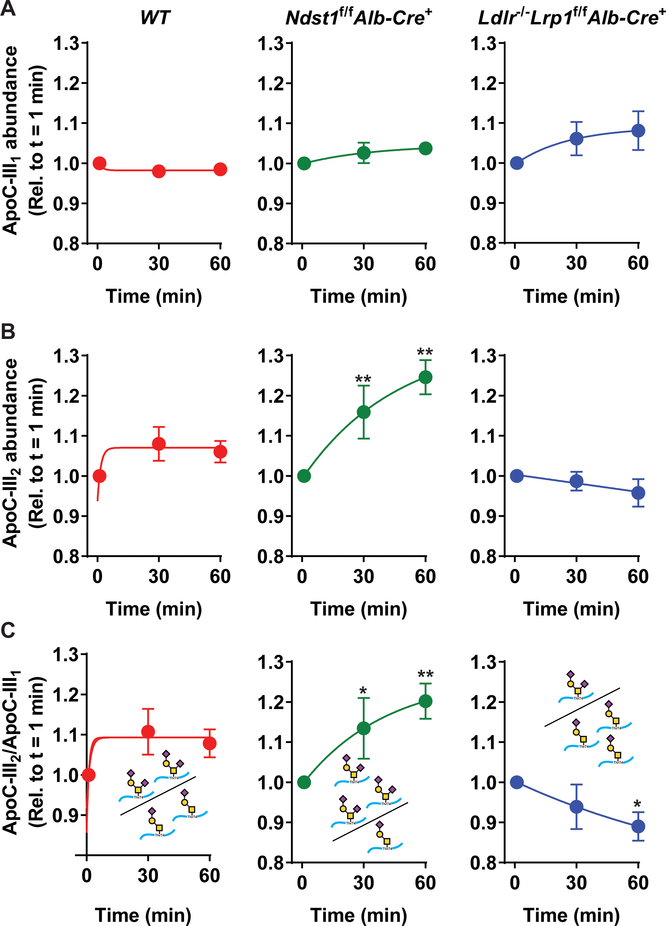

Hepatic SDC1 preferentially clears disialylated apoC-III glycoforms

To address in greater depth whether the efficiency of TRL clearance by hepatic receptors varied by apoC-III glycoform, the relative abundance of human apoC-III1 or apoC-III2 compared to all apoC-III glycoforms in each sample was measured by MSIA. In WT, Ndst1f/f Alb-Cre+ and Ldlr−/−Lrp1f/fAlb-Cre+ mice, the relative abundance of apoC-III1 did not change significantly over time (p = 0.06; Fig. 3A). Similarly, the relative abundance of apoC-III1 did not differ between the mouse groups (p = 0.5). In contrast, the relative abundance of apoC-III2 differed between mouse groups (p < 0.001) and was significantly affected by time (p = 0.03; Fig. 3B). Post-hoc analysis revealed that later difference was driven by the alter relative abundance over time in the Ndst1f/f Alb-Cre+ mice (Fig. 3B). In WT animals, the change in relative abundance of apoC-III2 is similar to the change in apoC-III1 resulting in an apoC-III2 to apoC-III1 ratio of approximately 1 indicating that both the mono- and disialylated apoC-III glycoforms were cleared from the circulation at similar rates (Fig. 3B–C). Interestingly, a difference was detected between the relative abundances of apoC-III2 in Ndst1f/f Alb-Cre+ mice and in Ldlr−/−Lrp1f/fAlb-Cre+ animals. In mice lacking functional liver HSPG receptor SDC1 presented with an increased relative abundance of apoC-III2 resulting in an increase of the apoC-III2 to apoC-III1 ratio from 1.0 at baseline to 1.2 at 60 min after injection of human TRLs (Fig. 3B, p = 0.0006). In contrast, in mice lacking LDLR and LRP1, both the relative abundance of apoC-III2 and the apoC-III2 to apoC-III1 ratio (1.0 at baseline vs. 0.89 after 60 min, p = 0.015) significantly decreased (Fig. 3C). These data suggest that HSPGs preferentially clear the disialylated apoC-III glycoform, whereas monosialylated apoC-III is cleared by LDLR and LRP1. These results are supported by data obtained by heparin-sepharose affinity chromatography separation. Human TRLs with an apoC-III2/apoC-III1 ratio of 0.25 were loaded onto a heparin sepharose column and eluted in a stepwise gradient with NaCl. The apoC-III2/apoC-III1 ratio in the fractions that bound heparin on the column was 0.45 and thus 1.9-fold higher than the apoC-III ratio of the human TRLs loaded onto the column. No significant difference was observed in the apoC-III2/apoC-III1 ratio between the fractions that bound the heparin column with different affinities (data not shown). The results suggest that HSPGs have a higher affinity for TRLs enriched with apoC-III2.

Figure 3: Normalized relative abundances reveal that HSPGs preferentially clear the disialylated apoC-III glycoform.

Human apoC-III was injected into WT (n = 7), Ndst1f/f Alb- Cre+ (n = 7), and Ldlr−/−Lrp1f/f Alb-Cre+ mice (n = 5) on apoC-III ASO (50 mg/kg bodyweight). The abundances of (A) apoC-III1 and (B) apoC-III2 relative to all apoC-III glycoforms in each sample were measured in the indicated mouse strains. Using two-way ANOVA, changes in apoC-III1 relative abundance did not differ by time (p = 0.06) or between mouse group (p=0.5). In contrast, the relative abundance of apoC-III2 differed by time (p = 0.03) and mouse group (p < 0.001). (C) The apoC-III2/apoC-III1 ratios indicate that Ndst1f/f Alb-Cre+ mice accumulate the disialylated apoC-III glycoform whereas WT and Ldlr−/−Lrp1f/f Alb-Cre+ mice do not. The ratio of apoC-III2/apoC-III1 significantly differed by mouse group (p<0.001) but not over time (p = 0.1). Values represent means ± SEM; * p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 compared to t = 0 min.

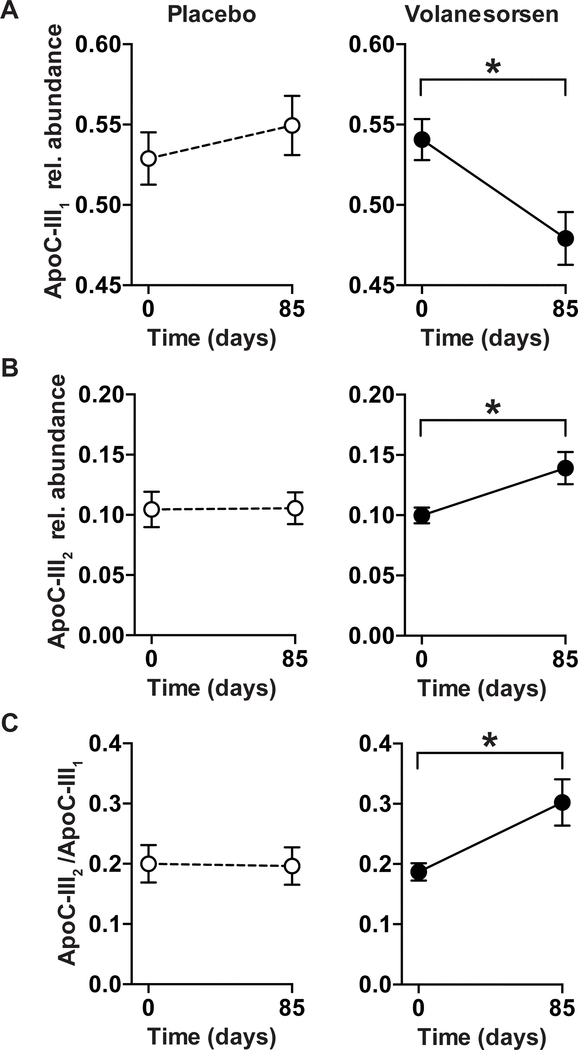

Changes in apoC-III glycoforms upon volanesorsen therapy

We next assessed the impact of apoC-III ASO treatment on apoC-III glycosylation in human patients who are obese by comparing the relative plasma distribution of apoC-III glycoforms in plasma samples from participants receiving volanesorsen (n = 11) or placebo (n = 6) over 13 weeks. Baseline characteristics of the two study cohorts are shown in Table 1. Participants were obese, with a mean BMI of 31.3 ± 3.3 kg/m2 (volanesorsen) or 32.1 ± 3.3 kg/m2 (placebo) respectively. These participants were eligible to participate in the volanesorsen trial based on fasting TG levels > 350 mg/dL; accordingly, their mean TG levels were 382.5 ± 236.3 mg/dL. Additional baseline characteristics of individuals randomized to the volanesorsen or placebo groups are presented in Table 1. The levels of plasma apoC-III concentrations in the placebo arm did not statistically differ between the two study time points (p = 0.3).Volanesorsen treatment after 85 days of the intervention resulted in an 81% decrease in total apoC-III concentration (226.4 ± 62.7 μg/mL to 43.9 ± 20.0 μg/mL), with all apoC-III glycoform concentrations decreasing (Table 2). ApoC-III1 and apoC-III2 concentrations decreased by 84% or 74% respectively. In contrast, only moderate non-significant changes were observed in the placebo group (total apoC-III: −17%). The relative abundances of apoC-III1 and apoC-III2 responded differently to the treatment. After volanesorsen treatment, the relative abundance of apoC-III1 significantly decreased by 15 % (p = 0.007, Fig. 4A), whereas the relative abundance of apoC-III2 significantly increased by 42% (p = 0.05, Fig. 4B). The ratio of apoC-III2/apoC-III1 significantly increased after treatment by 71% (p = 0.03, Fig. 4C). The relative abundances of apoC-III0a and apoC-III0b did not change after treatment (p > 0.1 for both). No significant changes in the relative abundances of apoC-III glycoforms were observed in the placebo group (Fig. 4A–C).

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of study cohorts.

| Characteristic | Volanesorsen (n = 11) | Placebo (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs.) | 52.3 (11.3) | 49.3 (14.0) |

| Sex (females) | 27.3% | 33.3% |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 100% | 66.7% |

| Hispanic | 0% | 16.7% |

| Others | 0% | 16.7% |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.32 (3.33) | 32.10 (3.34) |

| TG (mg/dL) | 559.14 (224.60) | 444.58 (140.39) |

| Total apoC-III (mg/dL) | 226.35 (62.64) | 217.93 (63.12) |

Data are presented as mean (SD).

Table 2.

Effect of volanesorsen treatment on apoC-III glycoforms and lipid levels.

| Measure | Volanesorsen | Placebo | Post treatment p-value (Δ volanesorsen vs. Δ placebo) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | ||

| Total apoC-III (μg/mL) | 226.35 (62.64) | 43.88 (19.95) | 217.93 (63.12) | 180.85 (58.99) | <.001 |

| ApoC-III0a (μg/mL) | 13.25 (7.24) | 2.86 (1.99) | 15.30 (7.42) | 11.74 (4.68) | 0.037 |

| ApoC-III0b (μg/mL) | 52.88 (16.08) | 10.28 (5.54) | 50.89 (18.84) | 39.53 (16.65) | 0.0005 |

| ApoC-III1 (μg/mL) | 123.32 (37.86) | 21.11 (10.00) | 114.00 (30.28) | 100.13 (37.46) | 0.0002 |

| ApoC-III2 (μg/mL) | 21.92 (5.10) | 5.80 (2.56) | 23.31 (10.04) | 18.97 (7.15) | <0.001 |

| ApoC-III2/ ApoC-III1 | 0.187 (0.048) | 0.302 (0.128) | 0.199 (0.076) | 0.196 (0.767) | 0.034 |

| TG levels (mg/dL) | 559.14 (224.60) | 139.45 (36.44) | 444.58 (140.39) | 442.17 (194.01) | 0.001 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 208.91 (58.69) | 192.41 (47.29) | 243.33 (34.16) | 226.17 (37.35) | 0.98 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 33.64 (9.63) | 48.27 (15.09) | 35.08 (5.64) | 32.75 (7.53) | 0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 64.64 (27.74) | 116.50 (53.65) | 107.25 (30.92) | 110.00 (44.98) | 0.0476 |

Data are presented as mean (SD). The p values were obtained by computing the differences pre and post treatment and then comparing these differences using a linear model.

Figure 4: Relative abundances of apoC-III1 and apoC-III2 after apoC-III ASO treatment of a human cohort.

Patients with hypertriglyceridemia were administered volanesorsen (300 mg, once weekly over 13 weeks) and plasma was analyzed at the beginning and the end (d = 85) of the study. (A) The relative abundance of apoC-III1 significantly decreased (p = 0.007) during the treatment period, whereas (B) the relative abundance of apoC-III2 significantly increased (p = 0.05) resulting in an increase in (C) the apoC-III2/apoC-III1 ratio (p = 0.03). Data represent means ± SEM.

Decrease in the relative abundance of apoC-III1 upon volanesorsen therapy correlates with reduction in plasma TGs

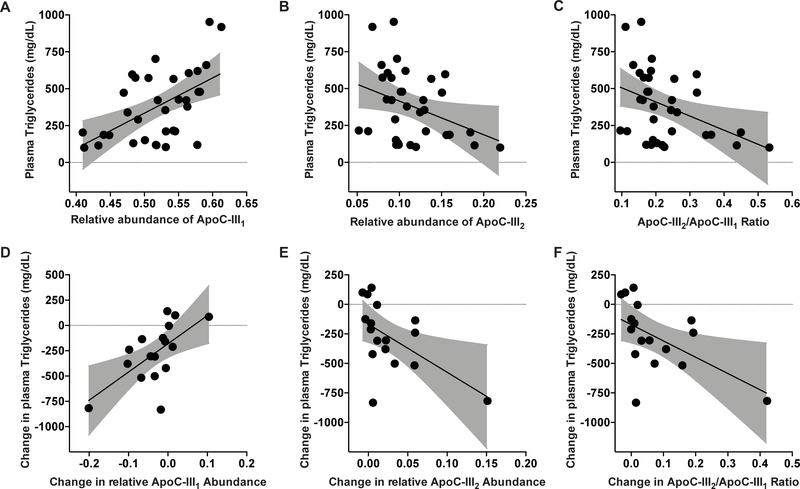

Next, we evaluated whether changes in apoC-III glycoforms are associated with changes in plasma TG levels. At baseline, plasma TGs were 559.1 ± 224.6 mg/mL and 444.6 ± 140.4 mg/mL in the volanesorsen and placebo groups, respectively (Table 2). Baseline apoC-III concentrations positively correlated with plasma TG levels (r = 0.71, p = 0.0015, data not shown). The relative abundance of apoC-III1 was significantly correlated with TG levels (r = 0.54, p = 0.0009, Fig. 5A). In contrast, the relative abundance of apoC-III2 was inversely associated with TG levels (r = −0.36, p = 0.03, Fig. 5B). Similarly, the apoC-III2/apoC-III1 ratio was inversely associated with plasma TG levels (r = −0.41, p = 0.016, Fig. 5C). The relative abundances of apoC-III0a (r = −0.25, p = 0.14) and apoC-III0b (r = 0.12, p = 0.51, data not shown) did not significantly correlate with plasma TG levels at baseline.

Figure 5: Association of apoC-III glycoforms with TG levels before and after volanesorsen treatment.

(A) The relative abundance of apoC-III1 was significantly correlated with TG levels (r= 0.54, p = 0.0009). (B) In contrast, the relative abundance of apoC-III2 was inversely associated with TG levels (r = −0.36, p = 0.03). (C) The ratio of apoC-III2/apoC-III1 was inversely associated with TG levels (r = −0.41, p = 0.016). At 85 days after treatment, (D) change in relative abundance of apoC-III1 was strongly correlated with change in TG levels (r = 0.63, p = 0.006). (E) Change in relative abundance of apoC-III2 was inversely correlated with change in TG levels (r = −0.55, p = 0.02). (F) Change in apoC-III2/apoC-III1 ratio was inversely associated with change in TG levels (r = −0.54, p = 0.02).

The 81% decrease in apoC-III levels after volanesorsen therapy was associated with a 75% decrease in TG levels (559.1 ± 224.6 mg/mL to 139.5 ± 36.4 mg/mL) (Table 2). In line with previous reports, we also observed a significant increase in mean LDL cholesterol and HDL cholesterol levels by 80% and 44%, respectively, after volanesorsen therapy (Table 2).13 The increases in mean LDL cholesterol and HDL cholesterol levels in the volanesorsen group were significant compared to the placebo group (p = 0.0476 and p < 0.001 respectively). The change in relative abundance of apoC-III1 was strongly correlated with reduction in TG levels (r = 0.63, p = 0.006, Fig. 5D), whereas both change in relative abundance of apoC-III2 (r = −0.55, p = 0.02, Fig. 5E) and change in apoC-III2/apoC-III1 ratio were inversely correlated with change in plasma TG levels (r = −0.54, p = 0.02, Fig. 5F). After we removed the outlier in Fig. 5E and 5F, the association between the change in apoC-III2 to total apoC-III (Fig. 5E, p = 0.2) and in apoC-III2/apoC-III1 (Fig. 5F, p = 0.2) with the change in triglyceride levels was no longer significant. However, the change in these two ratios by treatment arm remained statistically significant (p = 0.02 and p = 0.034 respectively).

DISCUSSION

In this study we evaluated the impact of apoC-III glycosylation on hepatic TRL clearance and tested whether therapeutic targeting of apoC-III alters glycoform abundance. Our results indicate that (1) inactivation of HSPGs increase the relative abundance of apoC-III2; (2) LDLR and LRP1 reduce apoC-III1 abundance over apoC-III2; and finally, (3) a clinical study showed reduction in TGs in patients via volanesorsen treatment to be associated with a greater reduction in plasma apoC-III1 than in apoC-III2.

Differential glycosylation of apoC-III may affect secretion or catabolism of apoC-III on TRLs. Thus far, in vitro experiments suggest that there is no evidence to support that glycosylation of apoC-III affects the production of apoC-III or its secretion with VLDL.29 It was shown in humans that the production rates of apoC-III1 and apoC-III2 are comparable.43 Therefore, we studied the more likely possibility that individual apoC-III glycoforms have different clearance pathways. Early studies using radioisotopes showed no differences between the clearance rates of apoC-III1 and of apoC-III2.44 However, another study by Mauger et al. revealed minor but not significant differences between the fractional catabolic rates of the mono- and disialylated apoC-III glycoforms suggesting a possible impact of glycosylation on the clearance mechanism.43 The exact mechanism of how hepatic receptors bind to and interact with different sialylated apoC-III glycoforms remains unknown. One explanation could be that the additional sialic acid molecule in apoC-III2 hinders interaction with the TRL-binding pocket of LDLR and LRP1.

Unfortunately, in mice, apoC-III glycoform abundance and its impact on hepatic TRL clearance cannot be evaluated due to lack of apoC-III glycosylation enzymes.37,38 To overcome this obstacle, we injected mice lacking different combinations of the three predominant TRL clearance receptors (HSPG, LDLR and LRP1) with human postprandial TRLs carrying the expected relative abundances of apoC-III glycoforms. Hepatic clearance of different TRL-associated apoC-III glycoforms is mediated by HSPG, predominantly SDC1, which is a slower but higher capacity metabolizer compared to LDLR and LRP1, which are more rapid and lower capacity clearance receptors.1,45 Our results suggest that sialylation status can affect the catabolic fate of TRL-associated apoC-III as disialylated apoC-III cleared more slowly in the absence of HSPG expression in the liver. The magnitude of the effect is rather small, yet this is comparable to the effects observed in the human studies,2,19. The results suggest that disialylated apoC-III TRLs are preferentially cleared by SDC1 compared to LDLR and LRP1 and is clearly reflected by the opposite trends observed in the relative ratio of monosialylated over disialylated apoC-III in HSPG-deficient versus LDLR and LRP1 compound knockout mice (Fig. 3C).

MSIA was unable to resolve apoC-III0a and apoC-III0b glycoforms from the highly abundant murine apoC-III0a despite our attempt to lower endogenous murine apoC-III levels via apoC-III ASO-mediated knockdown. This did not allow us to directly investigate the relationship between the apoC-III0a and apoC-III0b glycoforms and hepatic TRL-clearance receptors. But it is important to point out that our previous studies have indicated that the ratio between apoC-III2 and apoC-III1 best correlates with TG levels2,19,20 Despite these limitations, it is acceptable to assume that LDLR and LRP1 preferentially clear the apoC-III1 glycoforms as studies in mice showed that murine apoC-III0a predominantly blocks LDLR/LRP1-mediated TRL clearance.27 In contrast, murine and heparin sepharose affinity experiments indicate that SDC1 preferentially clears the less abundant apoC-III2 glycoform. It is unclear whether the apoC-III0a and apoC-III0b glycoforms affect the affinity of TRLs for SDC1, but in previous studies the absence or presence of murine apoC-III0a on TRLs did not seem to affect the capacity of SDC1 to mediate TRL clearance.27 This thus suggests no preferential binding of apoC-III0a to HSPGs.27 Combined, these observations support the idea that the apoC-III0a glycoform (or murine apoC-III) is a very potent inhibitor of TRL binding to LDLR and LRP1 and shifts clearance of apoC-III0a bearing TRLs to SDC1 by default (and not by greater affinity).

Our data show apoC-III2-enriched VLDL particles to bind heparin to a greater extent than apoC-III1-enriched VLDL. This higher affinity to heparin is in line with the observation that the disialylated glycoform is more efficiently cleared compared to the monosialylated glycoform in the absence of LDLR and LRP1. The mechanisms for the increased affinity of apoC-III2 to HSPGs may in part be explained by changes in the overall negative charge of the particle with the addition of the second sialic acid. Sialylation alters the charge of apoC-III on TRL by conferring a negative charge, which could change the affinity of apoC-III for lipid or interact with positively charged lysines on apoE.46 ApoC-III2, as the most negatively charged glycoform, might have a higher affinity for certain TRL particles, such as the smaller ones that are preferentially cleared via the slower proteoglycan-mediated pathways.33

Clinically, the increase in apoC-III2/apoC-III1 ratio upon lowering of apoC-III levels suggested faster clearance of apoC-III1 and associated with improved TG levels. Reducing apoC-III concentrations by apoC-III inhibition disproportionately affected apoC-III glycoforms, with a more pronounced drop in apoC-III1 than in apoC-III2 after treatment with the apoC-III ASO. Our data suggest that the apoC-III ASO volanesorsen may predominantly clear apoC-III1 via the LDLR/LRP1 pathway, whereas apoC-III2 is cleared to a greater extent by the slower internalizing receptor, SDC1, and is therefore less effectively cleared after total apoC-III levels are reduced. Although apoC-III1 and apoC-III2 exhibit similar production rates,43 we cannot fully exclude that lowering apoC-III production and secretion via ASO administration can disproportionally affect the production of different apoC-III glycoforms in humans. In fact, given the subtle differences in impact on apoC-III glycoform clearance that we found across receptors, we cannot exclude the possibility that relative abundances of apoC-III glycoforms are also regulated at the level of glycosylation and sialylation. Taken together, our data support the approach of assessing plasma apoC-III2/apoC-III1 to gain mechanistic insights into TRL clearance by the LDLR/LRP1 pathway.

The trend reflected by decreased TG levels with increased apoC-III2 relative abundance agrees with two previous observational studies; one with participants with obesity, high TG levels and diabetes2,19 and a second with participants undergoing a high carbohydrate or weight loss intervention.20 In these studies, we reported strong cross-sectional and longitudinal inverse relationships between relative abundance of apoC-III2 glycoform and plasma TG concentrations. The present clinical trial data strengthen the inference drawn from the previous results, which were based on observational data. Collectively, our findings suggest that the detrimental effect of apoC-III on TG metabolism stems from high levels of apoC-III1 in proportion to apoC-III2 and that this effect can be mitigated by ASO therapy, which affects apoC-III1 more strongly because it is more efficiently cleared by LDLR/LRP1 than apoC-III2.

Limitations of the current study are the small sample size of patients on ASO (due to availability) and the fact that post-treatment samples were only available at 85 days follow-up. Samples taken at the end of the treatment period were not available to demonstrate whether a similar trend in apoC-III2/apoC-III1 ratio could be observed. Despite these limitations, the changes observed in apoC-III1 and apoC-III2 relative abundances and in the apoC-III2/apoC-III1 ratio were significant. Further, it is worth mentioning that the presented mechanistic insights in our mouse model might not translate to humans.

In conclusion, our study showed more rapid clearance of apoC-III1, driven by LDLR and LRP1, than of apoC-III2, which is preferentially cleared by HSPGs. Clinically, we found a corresponding difference between the responses of these two apoC-III glycoforms to apoC-III silencing therapy, with the relative abundance of disialylated apoC-III increasing and positively associating with a reduction in TG levels. Our data showed for the first time that therapeutic targeting of apoC-III alters relative glycoform abundances and that assessing changes in apoC-III glycoforms can provide mechanistic insights into TRL clearance pathways.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

ApoC-III glycoforms have a differential impact on the capability of hepatic receptors to clear triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TRLs).

Syndecan-1 shows a higher affinity to TRLs containing disialylated apoC-III.

LDLR and LRP1 preferentially clear TRLs containing monosialylated apoC-III.

Reduction in plasma triglycerides by lowering apoC-III with volanesorsen is associated with a reduction in monosialylated apoC-III1 levels and not disialylated apoC-III.

Acknowledgments

We thank James Wang for technical assistance with apoC-III measurements, Dr. Qingqing Yang for statistical analysis and Dr. Veronica J. Alexander for sample procurement.

Sources of support.

Dr. Yassine was supported by 1R21AG056518, 1R01AG055770, 1R01AG054434 from the National Institute of Aging, and USC CTSI pilot UL1TR000130; B. Ramms was supported by AHA Predoctoral Fellowship 17PRE33410619 and Dr. Gordts by AHA grant 15BGIA25550111. Mass spectrometry work was supported by Awards R01DK082542 and R24DK090958 from the National Institute of Diabetes And Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Antisense oligonucleotides were provided by Ionis Pharmaceuticals Inc. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- ApoC-III

Apolipoprotein C-III

- ASO

Antisense oligonucleotide

- Gal

galactose

- GalNAc

N-acetylgalactosamine

- HSPG

Heparan sulfate proteoglycan

- LDLR

Low-density lipoprotein receptor

- LRP-1

Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1

- MSIA

Mass spectrometric immunoassay

- Neu5Ac

N-acetylneuraminic acid

- SDC1

Syndecan-1

- TG

Triglyceride

- TRLs

Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins

Footnotes

Disclosures.

Mark Graham and Richard Lee are employees of Ionis Pharmaceuticals. All other authors have no disclosures to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ramms B, Gordts P. Apolipoprotein c-iii in triglyceride-rich lipoprotein metabolism. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2018;29:171–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yassine HN, Trenchevska O, Ramrakhiani A, Parekh A, Koska J, Walker RW, Billheimer D, Reaven PD, Yen FT, Nelson RW, Goran MI, Nedelkov D. The association of human apolipoprotein c-iii sialylation proteoforms with plasma triglycerides. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0144138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brewer HB Jr., Shulman R, Herbert P, Ronan R, Wehrly K. The complete amino acid sequence of alanine apolipoprotein (apoc-3), and apolipoprotein from human plasma very low density lipoproteins. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:4975–4984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaith P, Assmann G, Uhlenbruck G. Characterization of the oligosaccharide side chain of apolipoprotein c-iii from human plasma very low density lipoproteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;541:234–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dallinga-Thie GM, Kroon J, Boren J, Chapman MJ. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and remnants: Targets for therapy? Curr Cardiol Rep. 2016;18:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nordestgaard BG, Varbo A. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease. Lancet. 2014;384:626–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jorgensen AB, Frikke-Schmidt R, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Loss-of-function mutations in apoc3 and risk of ischemic vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:32–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pollin TI, Damcott CM, Shen H, Ott SH, Shelton J, Horenstein RB, Post W, McLenithan JC, Bielak LF, Peyser PA, Mitchell BD, Miller M, O’Connell JR, Shuldiner AR. A null mutation in human apoc3 confers a favorable plasma lipid profile and apparent cardioprotection. Science. 2008;322:1702–1705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tg, Hdl Working Group of the Exome Sequencing Project NHL, Blood I, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in apoc3, triglycerides, and coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:22–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Capelleveen JC, Bernelot Moens SJ, Yang X, Kastelein JJP, Wareham NJ, Zwinderman AH, Stroes ESG, Witztum JL, Hovingh GK, Khaw KT, Boekholdt SM, Tsimikas S. Apolipoprotein c-iii levels and incident coronary artery disease risk: The epic-norfolk prospective population study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37:1206–1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norum RA, Lakier JB, Goldstein S, Angel A, Goldberg RB, Block WD, Noffze DK, Dolphin PJ, Edelglass J, Bogorad DD, Alaupovic P. Familial deficiency of apolipoproteins a-i and c-iii and precocious coronary-artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:1513–1519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jorgensen AB, Frikke-Schmidt R, West AS, Grande P, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Genetically elevated non-fasting triglycerides and calculated remnant cholesterol as causal risk factors for myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:1826–1833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaudet D, Alexander VJ, Baker BF, Brisson D, Tremblay K, Singleton W, Geary RS, Hughes SG, Viney NJ, Graham MJ, Crooke RM, Witztum JL, Brunzell JD, Kastelein JJ. Antisense inhibition of apolipoprotein c-iii in patients with hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:438–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng C, Khoo C, Furtado J, Sacks FM. Apolipoprotein c-iii and the metabolic basis for hypertriglyceridemia and the dense low-density lipoprotein phenotype. Circulation. 2010;121:1722–1734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SJ, Campos H, Moye LA, Sacks FM. Ldl containing apolipoprotein ciii is an independent risk factor for coronary events in diabetic patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:853–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mendivil CO, Zheng C, Furtado J, Lel J, Sacks FM. Metabolism of very-low-density lipoprotein and low-density lipoprotein containing apolipoprotein c-iii and not other small apolipoproteins. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:239–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng C, Khoo C, Ikewaki K, Sacks FM. Rapid turnover of apolipoprotein c-iii-containing triglyceride-rich lipoproteins contributing to the formation of ldl subfractions. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:1190–1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yao Z Human apolipoprotein c-iii - a new intrahepatic protein factor promoting assembly and secretion of very low density lipoproteins. Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Drug Targets. 2012;12:133–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koska J, Yassine H, Trenchevska O, Sinari S, Schwenke DC, Yen FT, Billheimer D, Nelson RW, Nedelkov D, Reaven PD. Disialylated apolipoprotein c-iii proteoform is associated with improved lipids in prediabetes and type 2 diabetes. J Lipid Res. 2016;57:894–905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mendoza S, Trenchevska O, King SM, Nelson RW, Nedelkov D, Krauss RM, Yassine HN. Changes in low-density lipoprotein size phenotypes associate with changes in apolipoprotein c-iii glycoforms after dietary interventions. J Clin Lipidol. 2017;11:224–233 e222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown WV, Baginsky ML. Inhibition of lipoprotein lipase by an apoprotein of human very low density lipoprotein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1972;46:375–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ginsberg HN, Le NA, Goldberg IJ, Gibson JC, Rubinstein A, Wang-Iverson P, Norum R, Brown WV. Apolipoprotein b metabolism in subjects with deficiency of apolipoproteins ciii and ai. Evidence that apolipoprotein ciii inhibits catabolism of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins by lipoprotein lipase in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1986;78:1287–1295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reyes-Soffer G, Sztalryd C, Horenstein RB, Holleran S, Matveyenko A, Thomas T, Nandakumar R, Ngai C, Karmally W, Ginsberg HN, Ramakrishnan R, Pollin TI. Effects of apoc3 heterozygous deficiency on plasma lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2019;39:63–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yao Z, Wang Y. Apolipoprotein c-iii and hepatic triglyceride-rich lipoprotein production. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2012;23:206–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sundaram M, Zhong S, Bou Khalil M, Links PH, Zhao Y, Iqbal J, Hussain MM, Parks RJ, Wang Y, Yao Z. Expression of apolipoprotein c-iii in mca-rh7777 cells enhances vldl assembly and secretion under lipid-rich conditions. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:150–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Windler E, Havel RJ. Inhibitory effects of c apolipoproteins from rats and humans on the uptake of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and their remnants by the perfused rat liver. J Lipid Res. 1985;26:556–565 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gordts PL, Nock R, Son NH, et al. Apoc-iii inhibits clearance of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins through ldl family receptors. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:2855–2866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaudet D, Brisson D, Tremblay K, Alexander VJ, Singleton W, Hughes SG, Geary RS, Baker BF, Graham MJ, Crooke RM, Witztum JL. Targeting apoc3 in the familial chylomicronemia syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2200–2206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roghani A, Zannis VI. Mutagenesis of the glycosylation site of human apociii. O-linked glycosylation is not required for apociii secretion and lipid binding. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:17925–17932 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hiukka A, Stahlman M, Pettersson C, Levin M, Adiels M, Teneberg S, Leinonen ES, Hulten LM, Wiklund O, Oresic M, Olofsson SO, Taskinen MR, Ekroos K, Boren J. Apociii-enriched ldl in type 2 diabetes displays altered lipid composition, increased susceptibility for sphingomyelinase, and increased binding to biglycan. Diabetes. 2009;58:2018–2026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mann CJ, Troussard AA, Yen FT, Hannouche N, Najib J, Fruchart JC, Lotteau V, Andre P, Bihain BE. Inhibitory effects of specific apolipoprotein c-iii isoforms on the binding of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins to the lipolysis-stimulated receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31348–31354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kowal RC, Herz J, Weisgraber KH, Mahley RW, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Opposing effects of apolipoproteins e and c on lipoprotein binding to low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:10771–10779 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foley EM, Gordts PL, Stanford KI, Gonzales JC, Lawrence R, Stoddard N, Esko JD. Hepatic remnant lipoprotein clearance by heparan sulfate proteoglycans and low-density lipoprotein receptors depend on dietary conditions in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:2065–2074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mortimer BC, Beveridge DJ, Martins IJ, Redgrave TG. Intracellular localization and metabolism of chylomicron remnants in the livers of low density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice and apoe-deficient mice. Evidence for slow metabolism via an alternative apoe-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28767–28776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacArthur JM, Bishop JR, Stanford KI, Wang L, Bensadoun A, Witztum JL, Esko JD. Liver heparan sulfate proteoglycans mediate clearance of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins independently of ldl receptor family members. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:153–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams KJ, Chen K. Recent insights into factors affecting remnant lipoprotein uptake. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2010;21:218–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khetarpal SA, Schjoldager KT, Christoffersen C, et al. Loss of function of galnt2 lowers high-density lipoproteins in humans, nonhuman primates, and rodents. Cell Metab. 2016;24:234–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schjoldager KT, Vakhrushev SY, Kong Y, Steentoft C, Nudelman AS, Pedersen NB, Wandall HH, Mandel U, Bennett EP, Levery SB, Clausen H. Probing isoform-specific functions of polypeptide galnac-transferases using zinc finger nuclease glycoengineered simplecells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:9893–9898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.MacArthur JM, Bishop JR, Wang L, Stanford KI, Bensadoun A, Witztum JL, Esko JD. Liver heparan sulfate proteoglycans mediate clearance of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins independently of ldl receptor family members. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:153–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bharadwaj KG, Hiyama Y, Hu Y, Huggins LA, Ramakrishnan R, Abumrad NA, Shulman GI, Blaner WS, Goldberg IJ. Chylomicron- and vldl-derived lipids enter the heart through different pathways: In vivo evidence for receptor- and non-receptor-mediated fatty acid uptake. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:37976–37986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramms B, Patel S, Nora C, et al. Apoc-iii aso promotes tissue lpl activity in absence of apoe-mediated trl clearance. J Lipid Res. 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fredenrich A, Giroux LM, Tremblay M, Krimbou L, Davignon J, Cohn JS. Plasma lipoprotein distribution of apoc-iii in normolipidemic and hypertriglyceridemic subjects: Comparison of the apoc-iii to apoe ratio in different lipoprotein fractions. J Lipid Res. 1997;38:1421–1432 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mauger JF, Couture P, Bergeron N, Lamarche B. Apolipoprotein c-iii isoforms: Kinetics and relative implication in lipid metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:1212–1218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huff MW, Fidge NH, Nestel PJ, Billington T, Watson B. Metabolism of c-apolipoproteins: Kinetics of c-ii, c-iii1 and c-iii2, and vldl-apolipoprotein b in normal and hyperlipoproteinemic subjects. J Lipid Res. 1981;22:1235–1246 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gordts P, Esko JD. The heparan sulfate proteoglycan grip on hyperlipidemia and atherosclerosis. Matrix Biol. 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lund-Katz S, Zaiou M, Wehrli S, Dhanasekaran P, Baldwin F, Weisgraber KH, Phillips MC. Effects of lipid interaction on the lysine microenvironments in apolipoprotein e. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34459–34464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.