Abstract

Purpose

Whereas the majority of nasal polyps observed in Western populations are eosinophilic, non-eosinophilic nasal polyps are significantly more frequent in Asian countries. Given the importance of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) in inflammation, this study focused on the role of NF-κB in the pathogenesis of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNPs) in Asian patients.

Methods

A total of 46 patients were enrolled in this study (22 diagnosed with CRSwNPs, 10 with chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps [CRSsNP], and 14 control subjects). Nasal polyps and uncinate tissues (UTs) were collected and the tissues prepared for hematoxylin-eosin staining and immunohistochemistric (IHC) analysis. Total RNA was isolated for real-time polymerase chain reaction for p65, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, intracellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1, IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and eotaxin.

Results

In the CRSwNPs group, 50% of nasal polyps were non-eosinophilic. IHC revealed a significantly higher fraction of NF-κB p65-positive cells in nasal polyps of the CRSwNPs group than in the UTs of control and CRSsNP groups. No difference in NF-κB p65-positive cell fraction was observed between eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic nasal polyps. The mRNA expression of p65, IL-6, IL-8, and eotaxin was significantly higher in nasal polyps of the CRSwNPs than in the UTs of control and CRSsNP group. However, no difference in expression was observed between eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic nasal polyps, with the exception of IL-1β expression.

Conclusions

Elevated expression of NF-κB- and NF-κB-associated inflammatory cytokines suggests NF-κB as the key factor for CRSwNPs pathogenesis in Asian patients. Understanding NF-κB-associated mechanisms will provide a deeper insight into CRSwNPs pathogenesis and ultimately improve therapeutic strategies for CRSwNPs.

Keywords: Nasal polyps, sinusitis, transcription factor, immunohistochemistry, cytokines

INTRODUCTION

Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNPs) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the nasal and paranasal sinus mucosae with a prevalence of 0.5%–4% in the general population.1 CRSwNPs can lead to nasal obstruction, olfactory dysfunction, headache, and posterior nasal drip, which adversely affect patients' quality of life.2

Although exact pathogenesis of nasal polyps is unknown, nasal polyps are generally characterized by edematous masses of inflamed mucosa and abundant inflammatory cells. However, recent studies have suggested that nasal polyps in Asian populations present different immunopathological features from the those in Western populations. Typically, whereas the majority of nasal polyps encountered in Western populations are eosinophilic, non-eosinophilic nasal polyps feature in a significant percentage of CRSwNPs reported in Asian countries.3,4,5,6,7,8

Immunopathological differences between populations should be analyzed, as they may stem from differences in pathogenesis and therefore dictate different therapeutic approaches. However, differences between eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic nasal polyps have not been studied in detail and most nasal polyp studies have so far focused on Western populations.

During chronic inflammation within paranasal sinuses, the growth of nasal polyps is induced and perpetuated by complex interactions of various cytokines produced by structural and infiltrating cells.9 Cytokine production during inflammation is, in turn, induced by transcription factors, most importantly nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB). NF-κB serves as a central inflammatory mediator and regulates multiple pro-inflammatory genes.10 When activated, NF-κB translocates to the cell nucleus and its active subunit, p65, induces the transcription of cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules. However, the role of NF-κB in the pathogenesis of CRSwNPs is still not fully understood, especially in Asian patients.

Given the importance of NF-κB in inflammation and the lack of nasal polyp studies in Asian patients, we investigated the expression of NF-κB, other inflammatory cytokines, and adhesion molecules in Asian patients with CRSwNPs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

A total of 46 patients were enrolled in this study, of which 22 were diagnosed with CRSwNPs and 10 were diagnosed with chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps (CRSsNP). The remaining 14 subjects underwent other rhinological surgical procedures, including septoplasty, showed no evidence of chronic rhinosinusitis in nasal endoscopy and computed tomography (CT) scans, so that they were enrolled as control subjects.

All patients were adults (> 18 years old), with sinus diseases diagnosed based on patient history, clinical examination, nasal endoscopy, and CT scans of the paranasal sinuses. Preoperative CT scans were reviewed to determine the extent of the sinus disease using the Lund-Mackay scoring system. Patients were excluded if they had received systemic or topical steroids and/or were prescribed antibiotics or antihistamine medications for 4 weeks before the study. Patients diagnosed with antrochoanal polyp, fungal sinusitis, and recurrent nasal polyps were excluded from the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and control subjects prior to study enrollment. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital (IRB No. 1504-059-664).

Tissue preparation

For histological analysis, nasal polyp tissues were obtained from 22 patients with CRSwNPs, whereas uncinate tissues (UTs) were obtained from 10 patients with CRSsNP and 14 control subjects. Half of the tissue mass of each sample was fixed with 10% formaldehyde solution, embedded in paraffin, sectioned into 4-μm slices, and subsequently used for hematoxylin-eosin staining and immunohistochemistric (IHC) analysis. The other half of each tissue sample was stored at −80°C in an ultra-low temperature freezer, and later used for real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Hematoxylin-eosin-stained sections were analyzed by 2 blinded physicians. Nasal polyps were classified as eosinophilic (> 10% of inflammatory cells in the studied area identified to be eosinophils) and non-eosinophilic.

NF-κB p65 IHC analysis

IHC staining was performed using the Histostain-Plus Bulk Kit (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA, USA). Briefly, after deparaffinization, the sections were microwave-treated in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for heat-induced epitope retrieval and incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide to inhibit endogenous peroxidases. The sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary mouse anti-human p65 monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA). Bound antibodies were visualized using a 3,3′-diaminobenzidine detection kit (Vector Laboratories) and slides counterstained with hematoxylin. Each tissue slice was photographed 5 times at 400× magnification. The presence of brown-yellowish granules in the cell nucleus was the criterion used to classify cells as p65-positive. Total cell number and number of p65-positive cells in epithelia, glands, and submucosa were determined by 2 independent researchers and the means were calculated. The p65-positive cell ratio was calculated according to the following formula and used as a parameter of NF-κB activity:

| p65-positive cell ratio = (number of NF-κB p65-positive cells/total number of cells) × 100% |

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from the stored frozen tissues using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using amfiRivert Platinum cDNA Synthesis Master Mix (GenDEPOT, Katy, TX, USA). Then, p65, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, intracellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1, IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, eotaxin, and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) cDNA was amplified using an ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) in conjunction with the 2 × SYBR green Master Mix reaction kit (Applied Biosystems). Primers were as follows: p65, 5′-CCACGAGCTTGTAGGAAAGG-3′ for the forward primer and 5′-CTGGATGCGCTGACTGATAG-3′ for the reverse primer; IL-6, 5′-ATGGCTGAAAAAGATGGATGCT-3′ for the forward primer and 5′-GCTCTGGCTTGTTCCTCACTACTC-3′ for the reverse primer; IL-8, 5′-GCCAACACAGAAATTATTGTAAAGCTT-3′ for the forward primer and 5′-AATTCTCAGCCCTCTTCAAAAACTT-3′ for the reverse primer; ICAM-1, 5′-TGTCCCCCTCAAAAGTCATC-3′ for the forward primer and 5′-TAGGCAACGGGGTCTCTATG-3′ for the reverse primer; IL-1β, 5′-ACGAATCTCCGACCACCACTA-3′ for the forward primer and 5′-GGCAGGGAACCAGCATCTT-3′ for the reverse primer; TNF-α, 5′-CCCAGGCAGTCAGATCATCTTC-3′ for the forward primer and 5′-AGCTGCCCCTCAGCTTGA-3′ for the reverse primer; eotaxin, 5′-CAGAGCCTGAGTGTTGCCTA-3′ for the forward primer and 5′-AACCCATGCCCTTTGGACTG-3′ for the reverse primer; and GAPDH, 5′-GAGAAGGCTGGGGCTCAT-3′ for the forward primer and 5′-TGCTGATGATCTTGAGGCTG-3′ for the reverse primer. The average transcript levels of genes were normalized to GAPDH.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean. Mann-Whitney U test and Kruskal-Wallis test were used to compare results between groups. Spearman's rank correlation test was used to assess the relationship between the levels of p65 and mRNA expression of various markers. Correlation coefficients (r) were presented as measures of association for regression relationships. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 18.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Patient data

Age and sex of the 46 enrolled patients can be summarized as follows: 22 CRSwNPs patients (14 male, 8 female; mean age 48.8 years, range 23-79 years), 10 CRSsNP patients (6 male, 4 female; mean age 42.8 years, range 23-67 years), and 14 control patients (8 male, 6 female; mean age 33.2 years, range 19-61 years). Lund-Mackay CT scores for CRSwNPs, CRSsNP, and control group were 8.4, 4.8, and 0.6, respectively. No statistically significant differences in sex and mean age were observed between the groups.

Eosinophilic vs. non-eosinophilic nasal polyps

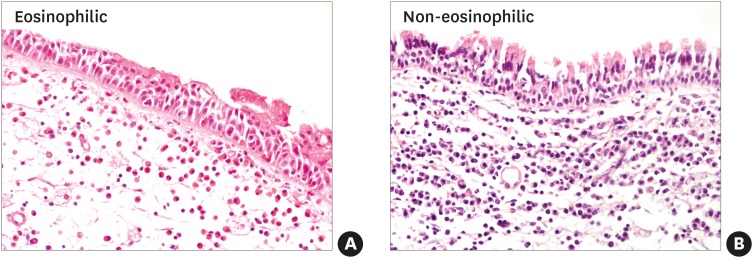

Histologically, in the CRSwNPs group (n = 22), 50% of the patients presented non-eosinophilic nasal polyps (Fig. 1). Eosinophilic nasal polyp patient group included 8 male and 3 female patients (mean age 53.2 years), whereas non-eosinophilic nasal polyp group consisted of 6 male and 5 female patients (mean age 44.5 years). Lund-Mackay CT scores were 7.5 and 9.3 for eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic groups, respectively (P > 0.05).

Fig. 1. Hematoxylin-Eosin staining (magnification × 400). (A) Eosinophilic nasal polyp, (B) non-eosinophilic nasal polyp. In the CRSwNPs group, 50% of the patients showed non-eosinophilic nasal polyps.

NF-κB p65 IHC analysis

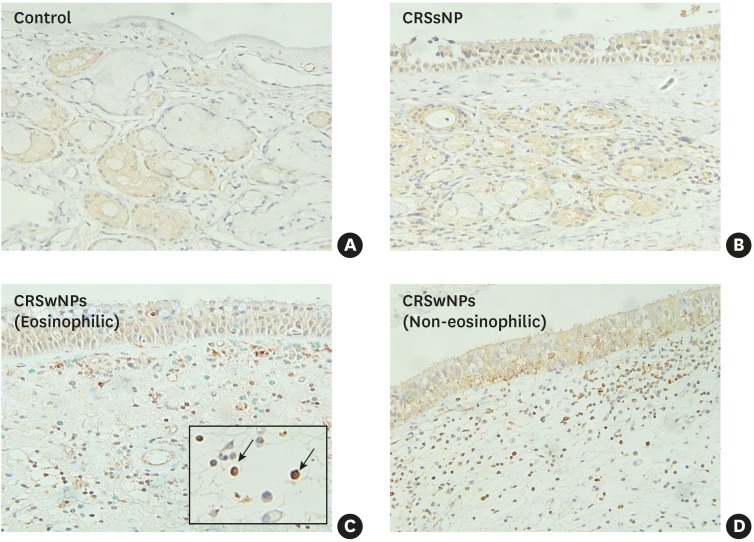

NF-κB p65 IHC showed positive immunoreactivity in the cytoplasm and nucleus of epithelial, sub-epithelial inflammatory as well as vascular and glandular endothelial cells (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Representative IHC results of NF-κB p65 expression in each group (magnification × 400). (A) Control, (B) CRSsNP, (C) CRSwNPs (eosinophilic), (D) CRSwNPs (non-eosinophilic). Examples of p65-positive cells (black arrows in the box).

IHC, immunohistochemistry; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B; CRSsNP, chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps; CRSwNPs, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps.

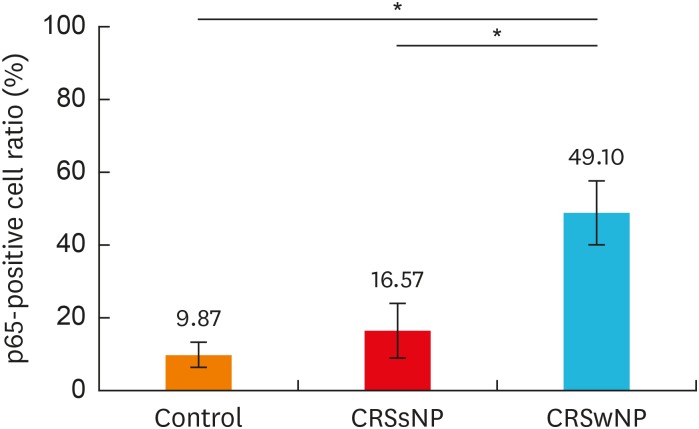

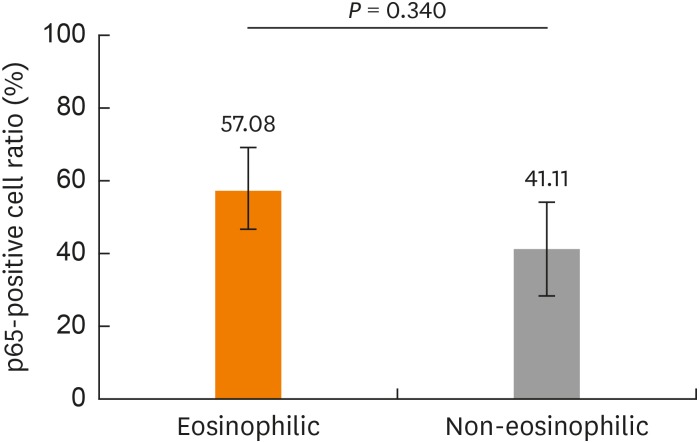

The ratio of NF-κB p65-positive cells was significantly higher in the CRSwNPs group (49.10%) than in control (9.87%) and CRSsNP (16.57%) groups (P = 0.041; Fig. 3). No statistically significant differences were observed between eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic nasal polyp groups (57.08% and 41.11%, P = 0.340; Fig. 4). In addition, there was no correlation between the ratio of NF-κB p65-positive cells and Lund-Mackay CT scores in both groups (r = −0.289, P = 0.464 in eosinophilic nasal polyp group; r = −0.144, P = 0.715 in the non-eosinophilic nasal polyp group).

Fig. 3. NF-κB p65-positive cell ratio in each group. NF-κB p65-positive cell ratio was significantly higher in the CRSwNPs group than in the control and CRSsNP groups. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error mean.

NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B; CRSsNP, chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps; CRSwNPs, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps.

*P < 0.05.

Fig. 4. NF-κB p65-positive cell ratio in eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic nasal polyps. NF-κB p65-positive cell ratio showed no difference between eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic nasal polyp groups. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error mean.

NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B.

Real-time PCR

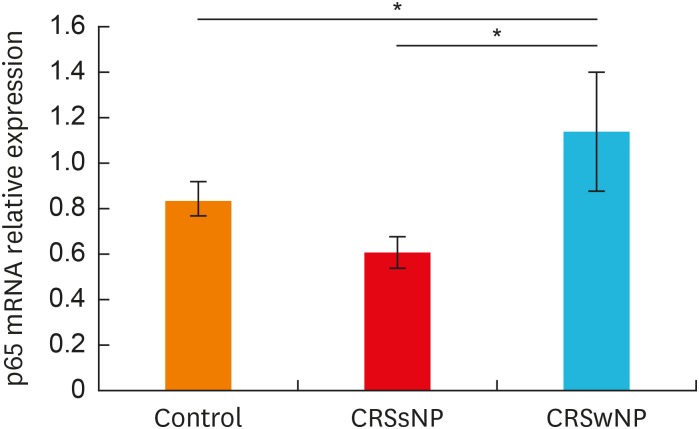

Expression in the nasal tissues of p65 mRNA, IL-6, IL-8, ICAM-1, IL-1β, TNF-α, and eotaxin was examined by real-time PCR. The mRNA expression of p65 in the nasal polyps of the CRSwNPs group was significantly higher than in the UTs of the control and CRSsNP groups (P = 0.034; Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. p65 mRNA expression level in each group. p65 mRNA expression in the nasal polyps was significantly higher in the CRSwNPs group than in the uncinate tissues of the control and CRSsNP groups. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error mean.

CRSsNP, chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps; CRSwNPs, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps.

*P < 0.05.

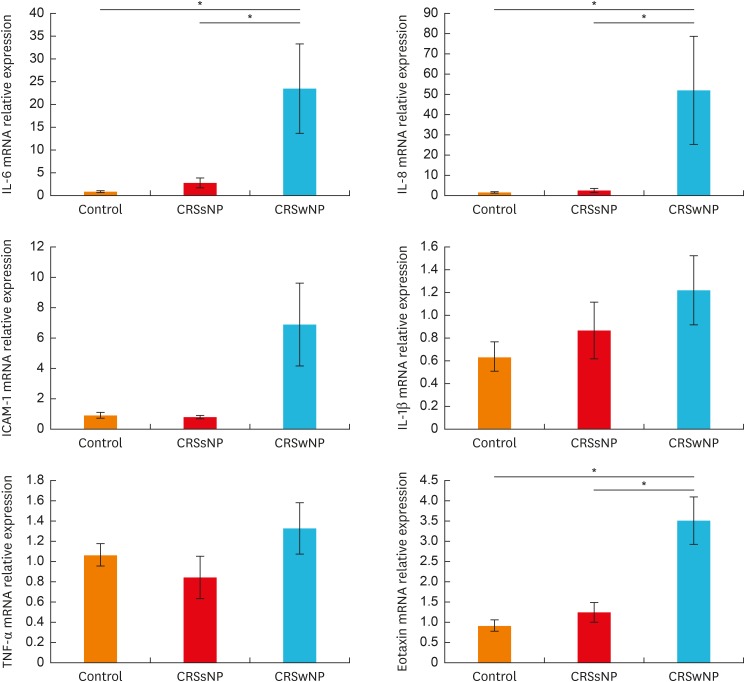

The expression of IL-6, IL-8, and eotaxin was significantly higher in CRSwNPs nasal polyps than in UTs of control and CRSsNP groups (P = 0.035, 0.025, and < 0.001, respectively). ICAM-1 mRNA expression was elevated in the nasal polyps of CRSwNPs patients compared to UTs in control and CRSsNP patients; however, the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.097). IL-1β or TNF-α expression showed no significant difference between the groups (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. IL-6, IL-8, ICAM-1, IL-1β, TNF-α, and eotaxin mRNA expression level in each group. Expression of IL-6, IL-8, and eotaxin was significantly higher in CRSwNPs nasal polyps than in the uncinate tissues of the control and CRSsNP groups. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error mean.

IL, interleukin; ICAM, intracellular adhesion molecule; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; CRSsNP, chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps; CRSwNPs, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps.

*P < 0.05.

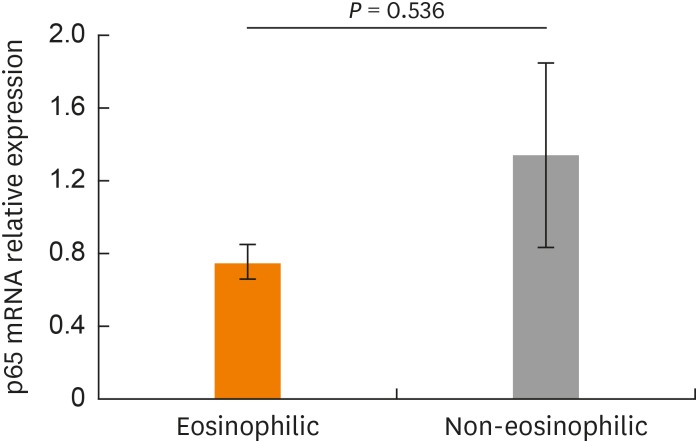

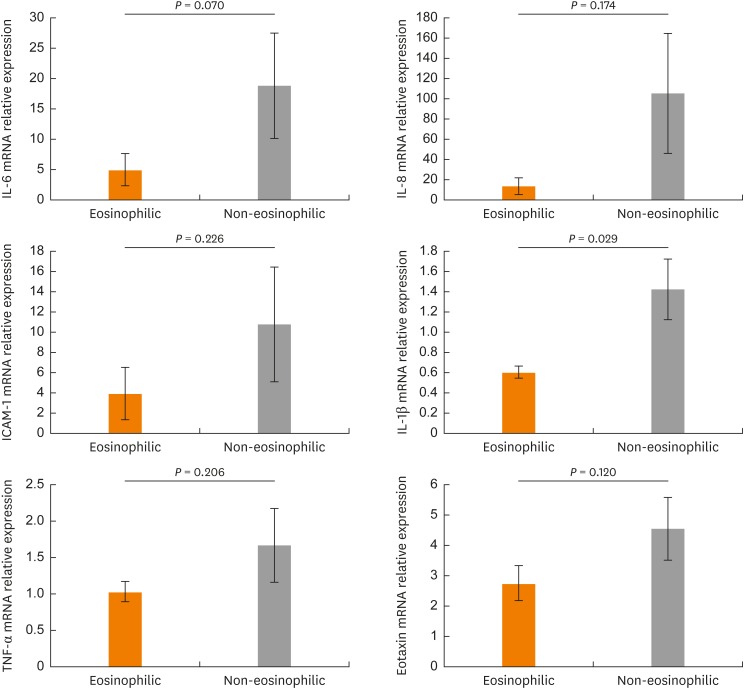

Additionally, no significant differences in p65 expression were observed between the eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic nasal polyp groups (P = 0.536; Fig. 7), nor were any differences observed in the expression of IL-6, IL-8, ICAM-1, TNF-α, and eotaxin. However, expression of IL-1β was significantly higher in the non-eosinophilic group compared to expression in the eosinophilic group (P = 0.029; Fig. 8). Correlation analysis revealed that the level of p65 mRNA expression in either group showed no correlation with IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β, TNF-α, or eotaxin; however, the expression level of ICAM-1 in the non-eosinophilic group showed significant correlation with p65 expression level (r = 0.809; P = 0.022) (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Fig. 7. p65 mRNA expression level in eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic nasal polyps. p65 mRNA expression showed no difference between the eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic nasal polyp groups. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error mean.

Fig. 8. IL-6, IL-8, ICAM-1, IL-1β, TNF-α, and eotaxin mRNA expression level in eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic nasal polyps. No difference in expression was observed between eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic nasal polyps, with the exception of IL-1β expression. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error mean.

IL, interleukin; ICAM, intracellular adhesion molecule; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

DISCUSSION

CRSwNPs is a chronic mucosal inflammatory disease with complex pathogenesis and multiple etiologies. Recently, immunohistological differences in nasal polyps of Asian and Caucasian populations were described. Typically, inflammation patterns in nasal polyps of Asian patients include Th1/Th17 dominance and neutrophilic activation, whereas in Caucasian patients, nasal polyps are often associated with eosinophilic airway inflammation. Except in cystic fibrosis and primary ciliary dyskinesia, in Caucasian CRSwNPs patients, eosinophils comprise 60%–90% of cell population in most nasal polyps.8,11,12,13,14 However, non-eosinophilic nasal polyps are more common in Asian populations,3,4,5,6,7 with 81.9% and 48.75% of non-eosinophilic nasal polyps reported in Thailand15 and Malaysia,16 respectively. In this study, CRSwNPs patients displayed an eosinophilic to non-eosinophilic ratio of 1:1, similar to those reported in previous studies in Asian populations. As histological differences in nasal polyps between Caucasian and Asian populations may indicate differences in pathogenesis and mechanisms of nasal polyp formation, different therapeutic approaches may be required for these patient groups.

Nasal polyps in both Asian and Caucasian populations develop as a result of chronic inflammation of sinonasal mucosa,17 induced and maintained by complex interactions of various cytokines.18 Cytokines stimulate structural cells of nasal mucosa to produce additional cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules, in a process which no longer requires the causal stimulus to perpetuate itself.19,20 Xu et al.21 reported that levels of IL-5, IL-6, and IL-8 were increased in CRSwNPs patients, compared to control group levels. Additionally, in situ hybridization indicated a significant increase in IL-1β and TNF-α expression in nasal polyps compared to the mucosa of the middle turbinate,22 whereas Papon et al.23 observed significantly higher ICAM-1 protein levels in nasal polyps than in control mucosa, using immunochemistry. In this study, real-time PCR indicated significantly higher expression of IL-6, IL-8, and eotaxin genes in patients with nasal polyps compared to expression in the normal control and CRSsNP groups. Higher ICAM-1 levels were also observed in the CRSwNPs group; however, the difference was not statistically significant. These results are in agreement with those of previous studies, possibly suggesting that IL-6, IL-8, eotaxin, and ICAM-1 participate in the development of CRSwNPs, and stress the importance of cytokines and adhesion molecules in polypogenesis. In contrast to previous studies, no significant differences in the expression of IL-1β and TNF-α were observed. Comparable expression levels of IL-6, IL-8, ICAM-1, TNF-α, and eotaxin in eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic nasal polyps (with the exception of IL-1β) suggest shared cytokines-induced mechanisms of polypogenesis regardless of histological types.

During inflammation, transcription factors are activated and translocate to the cell nucleus, inducing transcription of genes associated with inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules.24 NF-κB is a key pro-inflammatory nuclear transcription factor,24,25,26 whose active subunit p65 induces transcription of cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules. Cytokines may in turn activate NF-κB, offering an explanation for the perpetuation of inflammation in nasal polyps.19 NF-κB is known to mediate the transcription of genes for ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and the cytokines GM-CSF, TNF-α, IL-2, IL-6, and IL-8.22,27

Relationship between CRSwNPs and NF-κB has previously been studied. Xu et al.21 reported that NF-κB expression is upregulated in CRSwNPs patients and that NF-κB levels correlate with IL-6 and IL-8 cytokine expression. Wilson et al.28 and Silvestri et al.29 reported that TNF-α induced the expression of ICAM-1 and IL-8 in respiratory epithelial cells via NF-κB. Recently, Takeno et al.20 analyzed 28 patients with nasal polyps using IHC, observed increased NF-κB levels in CRSwNPs patients, and reported that increased p50 levels correlated with increased expression of IL-8, IL-16, and eotaxin. In this study, significantly higher levels of p65 mRNA and p65-positive cell ratio were observed in CRSwNPs patients compared to controls and CRSsNP patients, which indicated the role of NF-κB in the polypogenesis of CRSwNPs. However, no difference in p65 mRNA levels or IHC-determined ratio of NF-κB positive cells was observed between eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic nasal polyps. Additionally, no significant difference observed in the expression of IL-6, IL-8, ICAM-1, TNF-α, and eotaxin, except IL-1β. In correlation analysis, the level of p65 mRNA expression in either group showed no correlation with IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β, TNF-α, or eotaxin, except ICAM-1 in non-eosinophilic NP group. This study has limitations in not examining which specific NF-κB-related pathway affects polypogenesis in Asian patients. The specific role of NF-κB in the polypogenesis of CRSwNPs and the difference between eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic nasal polyps should be evaluated in further studies.

This is the first study to analyze the role of NF-κB in nasal polyps in an Asian population and to examine the differences between eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic polyps. Despite previously identified differences in nasal polyps of Caucasian and Asian populations, shared NF-κB mechanisms suggest that inhibition of NF-κB could be explored as a therapeutic approach for CRSwNPs in both population groups. As Valera et al.30 reported that dehydroxymethylepoxyquinomicin, a NF-κB inhibitor, is effective in treating Caucasian patients with CRSwNPs, this approach may also be effective in Asian CRSwNPs patients; however, further studies are required to evaluate the therapeutic potential of modulating the NF-κB pathway to inhibit polypogenesis in Asian CRSwNPs patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant No. 04-2016-0280 from the Seoul National University Hospital research fund.

Footnotes

Disclosure: There are no financial or other issues that might lead to conflict of interest.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Correlation between p65 and IL-6, IL-8, ICAM-1, IL-1β, TNF-α, and eotaxin mRNA expression level. No significant correlation was observed, with the exception of ICAM-1 in the non-eosinophilic nasal polyp group.

References

- 1.Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Mullol J, Bachert C, Alobid I, Baroody F, et al. European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2012. Rhinol Suppl. 2012;23:1–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pawankar R. Nasal polyposis: an update: editorial review. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;3:1–6. doi: 10.1097/00130832-200302000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim JW, Hong SL, Kim YK, Lee CH, Min YG, Rhee CS. Histological and immunological features of non-eosinophilic nasal polyps. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137:925–930. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang N, Van Zele T, Perez-Novo C, Van Bruaene N, Holtappels G, DeRuyck N, et al. Different types of T-effector cells orchestrate mucosal inflammation in chronic sinus disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:961–968. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soler ZM, Mace JC, Litvack JR, Smith TL. Chronic rhinosinusitis, race, and ethnicity. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2012;26:110–116. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2012.26.3741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hao J, Pang YT, Wang DY. Diffuse mucosal inflammation in nasal polyps and adjacent middle turbinate. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:267–275. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gevaert P, Kaliner MA, Van Cauwenberge P. Global Resources in Allergy™. Chronic rhinosinusitis and nasal polyposis (module 10) Milwaukee (WI): World Allergy Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meltzer EO, Hamilos DL, Hadley JA, Lanza DC, Marple BF, Nicklas RA, et al. Rhinosinusitis: establishing definitions for clinical research and patient care. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:155–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frączek M, Rostkowska-Nadolska B, Kapral M, Szota J, Kręcicki T, Mazurek U. Microarray analysis of NF-κB-dependent genes in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2013;22:209–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henriksson G, Norlander T, Forsgren J, Stierna P. Effects of topical budesonide treatment on glucocorticoid receptor mRNA down-regulation and cytokine patterns in nasal polyps. Am J Rhinol. 2001;15:1–8. doi: 10.2500/105065801781329446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larsen K, Tos M. Clinical course of patients with primary nasal polyps. Acta Otolaryngol. 1994;114:556–559. doi: 10.3109/00016489409126104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lund VJ. Diagnosis and treatment of nasal polyps. BMJ. 1995;311:1411–1414. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7017.1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vento SI, Ertama LO, Hytönen ML, Wolff CH, Malmberg CH. Nasal polyposis: clinical course during 20 years. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:209–214. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62468-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirtsreesakul V. Nasal polyps: the relationship to allergy, sinonasal infection and histopathological type. J Med Assoc Thai. 2004;87:277–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jareoncharsri P, Bunnag C, Muangsomboon S, Tunsuriyawong P, Assanasen P. Clinical and histopathological classification of nasal polyps in Thais. Siriraj Med J. 2002;54:689–697. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tikaram A, Prepageran N. Asian nasal polyps: a separate entity? Med J Malaysia. 2013;68:445–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daines SM, Orlandi RR. Inflammatory cytokines in allergy and rhinosinusitis. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;18:187–190. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e328338206a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phan NT, Cabot PJ, Wallwork BD, Cervin AU, Panizza BJ. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of chronic rhinosinusitis and potential therapeutic strategies: review on cytokines, nuclear factor kappa B and transforming growth factor beta. J Laryngol Otol. 2015;129(Suppl 3):S2–S7. doi: 10.1017/S0022215115001322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adcock IM, Caramori G. Cross-talk between pro-inflammatory transcription factors and glucocorticoids. Immunol Cell Biol. 2001;79:376–384. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2001.01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takeno S, Hirakawa K, Ueda T, Furukido K, Osada R, Yajin K. Nuclear factor-kappa B activation in the nasal polyp epithelium: relationship to local cytokine gene expression. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:53–58. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200201000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu R, Xu G, Shi J, Wen W. A correlative study of NF-κB activity and cytokines expression in human chronic nasal sinusitis. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:644–649. doi: 10.1017/S0022215106001824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lennard CM, Mann EA, Sun LL, Chang AS, Bolger WE. Interleukin-1 beta, interleukin-5, interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in chronic sinusitis: response to systemic corticosteroids. Am J Rhinol. 2000;14:367–373. doi: 10.2500/105065800779954329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papon JF, Coste A, Gendron MC, Cordonnier C, Wingerstmann L, Peynègre R, et al. HLA-DR and ICAM-1 expression and modulation in epithelial cells from nasal polyps. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:2067–2075. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200211000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Necela BM, Cidlowski JA. Mechanisms of glucocorticoid receptor action in noninflammatory and inflammatory cells. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2004;1:239–246. doi: 10.1513/pats.200402-005MS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnes PJ, Karin M. Nuclear factor-κB: a pivotal transcription factor in chronic inflammatory diseases. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1066–1071. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704103361506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawrence T. The nuclear factor NF-κB pathway in inflammation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a001651. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baeuerle PA, Henkel T. Function and activation of NF-κB in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:141–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson SJ, Leone BA, Anderson D, Manning A, Holgate ST. Immunohistochemical analysis of the activation of NF-κB and expression of associated cytokines and adhesion molecules in human models of allergic inflammation. J Pathol. 1999;189:265–272. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199910)189:2<265::AID-PATH415>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silvestri M, Sabatini F, Scarso L, Cordone A, Dasic G, Rossi GA. Fluticasone propionate downregulates nasal fibroblast functions involved in airway inflammation and remodeling. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2002;128:51–58. doi: 10.1159/000058003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valera FC, Umezawa K, Brassesco MS, Castro-Gamero AM, Queiroz RG, Scrideli CA, et al. Suppression of inflammatory cytokine secretion by an NF-κB inhibitor DHMEQ in nasal polyps fibroblasts. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2012;30:13–22. doi: 10.1159/000339042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Correlation between p65 and IL-6, IL-8, ICAM-1, IL-1β, TNF-α, and eotaxin mRNA expression level. No significant correlation was observed, with the exception of ICAM-1 in the non-eosinophilic nasal polyp group.