Abstract

Identifying prognostic factors by affordable tools is crucial for guiding gastric cancer (GC) treatments especially at earlier stages for timing interventions. The autonomic function that is clinically assessed by heart rate variability (HRV) is involved in tumorigenesis. This pilot study was aimed to examine whether nonlinear indices of HRV can be biomarkers of GC severity. Sixty-one newly-diagnosed GC patients were enrolled. Presurgical serum fibrinogen (FIB), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA199) were examined. Resting electrocardiogram (ECG) of 5-min was collected prior to surgical treatments to enable the HRV analysis. Twelve nonlinear HRV indices covering the irregularity, complexity, asymmetry, and temporal correlation of heartbeat fluctuations were obtained. Increased short-range temporal correlations, decreased asymmetry, and increased irregularity of heartbeat fluctuations were associated with higher FIB level. Increased irregularity and decreased complexity were also associated with higher CEA level. These associations were independent of age, sex, BMI, alcohol consumption, history of diabetes, left ventricular ejection fraction, and anemia. The results support the hypothesis that perturbations in nonlinear dynamical patterns of HRV predict increased GC severity. Replication in larger samples as well as the examination of longitudinal associations of HRV nonlinear features with cancer prognosis/survival are warranted.

Subject terms: Prognostic markers, Translational research

Introduction

The fact of late-stage presentation and inaccessible treatment is urging an early diagnosis of cancer, the second leading cause of death worldwide. Such a malignancy spreads equally without preference on human beings all over the world but gastric cancer (GC) acts rather eccentrically that has been pushed out as an exception. It is so common in China and other East Asia countries as well, ranking the second in cancer death as opposed to the fifth globally1. To improve GC prognosis and facilitate a better treatment planning, early and sensitive diagnosis with feasible and affordable clinical measurements is essential.

Converging evidence has suggested a pivotal role of the autonomic control in tumor progression, in particular the contribution of the vagal nerve activity through many tumor-inhibiting mechanisms2,3. As a clinical routine, the measurement of electrocardiogram (ECG) or more specifically the analysis of the beat-to-beat ECG RR interval variations – the heart rate variability (HRV) – is an optimal noninvasive biomarker for the autonomic regulation4,5. In previous studies, reduced HRV was found in cancer patients compared to healthy peers6. Lower HRV at baseline was also reported to predict increased carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) months later in a historical-prospective study7. In addition, in a most recent systematic review on HRV and cancer prognosis8, 19 studies that involved various kinds of cancer patients were included and appraised. Regardless of the cancer types, this review concluded an adverse effect of lower HRV towards shorter survival, higher tumor burden, or more advanced metastasis stage. Consistently, in another recent clinical study of GC patients9, lower HRV was found to be associated with advanced clinical stage, increased tumor size, tumor infiltration, lymph node metastasis, and involvement of distant organs.

Surprisingly, all studies reviewed above used only traditional linear HRV measures, albeit a commonly accepted nonlinear nature of HRV10,11. It is considered highly complex owning to the competition between spontaneity and adaptability of the heart beat regulation. Across a variety of studies in the field of cardiovascular diseases, nonlinear dynamical HRV analysis has shown a tremendous advantage over these linear time- and frequency-domain methods10–17. Therefore, we would like to examine the potential of nonlinear HRV measures in cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment planning. At the time of analysis, 61 consecutive patients diagnosed with GC were enrolled. In this pilot phase, we explored the relationships of 12 commonly-used nonlinear HRV measures including (1) six entropy-based measures: approximate entropy (ApEn), sample entropy (SampEn), fuzzy entropy (FuzzyEn), permutation entropy (PermEn), conditional entropy (CE), distribution entropy (DistEn); (2) four asymmetry indices: Porta’s index (PI), Guzik’s index (GI), slope index (SI), area index (AI); and (3) detrended fluctuation analysis (DFA) derived metrics α1 and α2 with serum indices that are highly relevant to cancer prognosis including fibrinogen (FIB)18,19, CEA20, and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA199)21. We hypothesized that patients with nonlinear HRV measures changing towards lower complexity/higher randomness had increased serum FIB, CEA, and CA199 levels.

Results

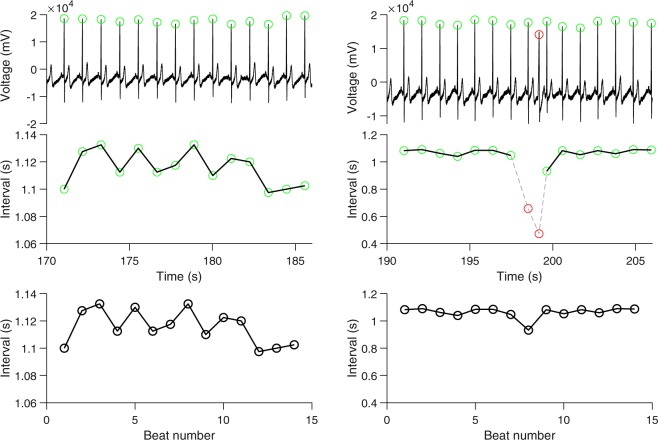

Figure 1 shows examples of RR interval time-series that illustrate the construction of RR interval time-series from ECG without ectopic beats and with ectopic beats, respectively. Table 1 summarizes the demographics and the clinical and HRV measures of patients. Pearson correlation analyses resulted in six nonlinear HRV features, i.e., FuzzyEn, PermEn, DistEn, PI, α1, that had significant (p < 0.1) correlations with at least one of the three clinical GC parameters (Table 2). Based on these results, linear regression models of FIB with separately FuzzyEn, PermEn, PI, or α1 were performed; linear regression models of CEA with PermEn, DistEn, or PI separately were performed; linear regression models of CA199 with PI or GI were separately examined. Results from linear regressions were summarized in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Construction of heart rate variability time-series. Upper panel: shown left an electrocardiogram (ECG) segment (a zoomed-in portion from the complete recording) without ectopic beats and right another ECG segment with ectopic beats (the beat marked in red). Middle panel: the time interval (RR interval) between the current R beat and the following R beat. Two anomaly intervals related to the ectopic beat are shown in red with gray dashed lines on the right-hand side. Bottom panel: the time-series used for analysis. The RR interval time-series on the left-hand side without anomalies is used directly for analysis. The anomalies on the right-hand side are removed and the resulted two pieces are sewed together to make one time-series for analysis.

Table 1.

Demographical, clinical, and HRV measures of patients.

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| N (female/male) | 61 (16/45) |

| Age (years) | 63.6 (10.4) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.6 (3.3) |

| Medical | |

| History of alcohol consumption (yes/no) | 9/52 |

| History of diabetes (yes/no) | 11/50 |

| LVEF | 56.9 (4.0) |

| Hematology | |

| FIB (g/L) | 3.49 (0.84) |

| CEA | 3.32 [4.66] |

| CA199 | 13.6 [48.31] |

| Hb | 125.5 (21.4) |

| HRV | |

| ApEn | 0.98 (0.14) |

| SampEn | 1.82 (0.34) |

| FuzzyEn | 1.35 (0.26) |

| PermEn | 3.12 (0.25) |

| CE | 1.95 (0.28) |

| DistEn | 0.65 (0.08) |

| PI | 0.51 (0.03) |

| GI | 0.50 (0.01) |

| SI | 0.50 (0.01) |

| AI | 0.50 (0.01) |

| α1 | 1.13 (0.23) |

| α2 | 1.05 (0.19) |

Values are expressed as mean (standard deviation) or median [inter-quartile range].

Abbreviations: ApEn = approximate entropy; AI = area index; BMI = body mass index; CA199 = carbohydrate antigen 19-9; CE = conditional entropy; CEA = carcinoembryonic antigen; DistEn = distribution entropy; FIB = fibrinogen; FuzzyEn = fuzzy entropy; GI = Guzik’s index; Hb = hemoglobin; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; PermEn = permutation entropy; PI = Porta’s index; SampEn = sample entropy; SI = slope index.

Table 2.

Bivariate correlation between clinical gastric cancer parameters and nonlinear HRV parameters.

| FIB | CEA | CA199 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ApEn | (−0.09, 0.5) | (−0.05, 0.7) | (0.00, >0.9) |

| SampEn | (−0.09, 0.5) | (0.20, 0.1) | (0.00, >0.9) |

| FuzzyEn | (−0.25, 0.05) | (0.05, 0.7) | (−0.01, >0.9) |

| PermEn | (0.38, 0.003) | (0.35, 0.006) | (0.03, 0.8) |

| CE | (−0.08, 0.5) | (0.05, 0.7) | (0.13, 0.3) |

| DistEn | (−0.21, 0.1) | (−0.32, 0.01) | (0.05, 0.7) |

| PI | (−0.44, 0.0004) | (−0.26, 0.05) | (−0.25, 0.05) |

| GI | (−0.20, 0.1) | (−0.06, 0.6) | (−0.27, 0.04) |

| SI | (−0.17, 0.2) | (−0.15, 0.3) | (−0.20, 0.1) |

| AI | (−0.19, 0.2) | (0.04, 0.8) | (−0.19, 0.1) |

| α1 | (0.49, <0.0001) | (−0.04, 0.8) | (0.05, 0.7) |

| α2 | (0.21, 0.1) | (−0.05, 0.7) | (−0.07, 0.6) |

Values are expressed as (r, p).

Bold indicates statistically significant at p < 0.1. Abbreviations: ApEn = approximate entropy; AI = area index; BMI = body mass index; CA199 = carbohydrate antigen 19-9; CE = conditional entropy; CEA = carcinoembryonic antigen; DistEn = distribution entropy; FIB = fibrinogen; FuzzyEn = fuzzy entropy; GI = Guzik’s index; PermEn = permutation entropy; PI = Porta’s index; SampEn = sample entropy; SI = slope index.

Table 3.

Results from linear regression models (adjusted for age and sex).

| Outcome | Predictor | Coefficient (Estimate ± SE)* | p | FDR-corrected p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FIB | α1 | 0.41 ± 0.10 | 0.0001 | 0.0009 |

| FIB | PI | −0.35 ± 0.10 | 0.0009 | 0.004 |

| FIB | PermEn | 0.30 ± 0.11 | 0.007 | 0.02 |

| CEA | PermEn | 0.36 ± 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| CEA | DistEn | −0.32 ± 0.14 | 0.02 | <0.05 |

| CA199 | GI | −0.65 ± 0.33 | 0.06 | >0.05 |

| CEA | PI | −0.27 ± 0.15 | 0.07 | >0.05 |

| CA199 | PI | −0.44 ± 0.23 | 0.07 | >0.05 |

| FIB | FuzzyEn | −0.19 ± 0.11 | 0.08 | >0.05 |

*Effects for 1-standard deviation increase in the predictor adjusted for covariates.

Abbreviations: CA199 = carbohydrate antigen 19-9; CEA = carcinoembryonic antigen; DistEn = distribution entropy; FDR: false discovery rate; FIB = fibrinogen; FuzzyEn = fuzzy entropy; GI = Guzik’s index; PermEn = permutation entropy; PI = Porta’s index; SE: standard error.

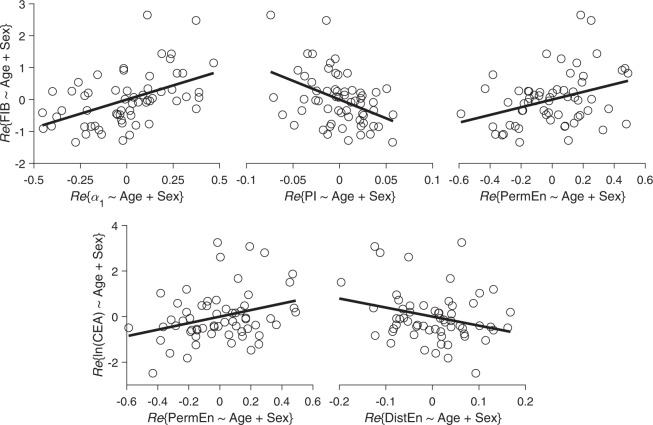

After correcting for multiple comparisons, α1, PI, and PermEn were significantly associated with FIB, specifically, FIB increased by 0.41 ± 0.10, −0.35 ± 0.10, and 0.30 ± 0.11, respectively, for each 1-SD increase in α1, PI, and PermEn (all false discovery rate [FDR]-corrected p < 0.05). PermEn and DistEn were significantly associated with CEA, specifically, CEA increased by 0.36 ± 0.15 and −0.32 ± 0.14, respectively, for each 1-SD increase in PermEn and DistEn (both FDR-corrected p < 0.05). These five significant associations are further explained by the partial correlation plots as shown in Fig. 2 (the corresponding correlation plots without adjust for demographics were shown in Fig. S1 documented in the online Supplemental Materials). No parameters were significantly associated with CA199. After further adjusting for BMI, alcohol consumption, history of diabetes, Hb, and LVEF, all these associations still held with slightly changes in the estimated coefficients as shown in Table 4.

Figure 2.

Partial correlation plots for the significant associations after correcting for FDR. Re{Y ~ X}: the residual for regressing Y against X. Abbreviations: CEA = carcinoembryonic antigen; DistEn = distribution entropy; FIB = fibrinogen; PermEn = permutation entropy; PI = Porta’s index.

Table 4.

Results from the augmented linear regression models (adjusted for age, sex, BMI, alcohol consumption, history of diabetes, Hb, and LVEF).

| Outcome | Predictor | Coefficient (Estimate ± SE)* | p | FDR-corrected p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FIB | α1 | 0.41 ± 0.10 | 0.0002 | 0.002 |

| FIB | PI | −0.34 ± 0.11 | 0.003 | 0.01 |

| FIB | PermEn | 0.33 ± 0.11 | 0.005 | 0.02 |

| CEA | PermEn | 0.38 ± 0.16 | 0.02 | <0.05 |

| CEA | DistEn | −0.34 ± 0.15 | 0.02 | >0.05 |

| CA199 | PI | −0.41 ± 0.25 | 0.1 | >0.05 |

| FIB | FuzzyEn | −0.18 ± 0.12 | >0.1 | >0.05 |

| CEA | PI | −0.24 ± 0.16 | >0.1 | >0.05 |

| CA199 | GI | −0.52 ± 0.37 | >0.1 | >0.05 |

*Effects for 1-standard deviation increase in the predictor adjusted for covariates.

Abbreviations: CA199 = carbohydrate antigen 19-9; CEA = carcinoembryonic antigen; DistEn = distribution entropy; FDR: false discovery rate; FIB = fibrinogen; FuzzyEn = fuzzy entropy; GI = Guzik’s index; Hb = hemoglobin; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; PermEn = permutation entropy; PI = Porta’s index; SE: standard error.

The associations of FIB with α1, PI, and PermEn were also significant in secondary analysis using logistic regression with dichotomized outcomes, specifically, the odds of having higher FIB increased by 168% (95% confidence interval [CI]: [43%, 478%]), −52% (95% CI: [−76%, −14%]), and 79% (95% CI: [2%, 232%]), respectively, with each 1-SD increase in α1, PI, and PermEn (all p < 0.05; Table 5). The associations of CEA with PermEn and DistEn became not significant in the logistic regression models. However, PI showed significant associations with CA199 with an odds ratio of 0.53 (95% CI: [0.27, 0.95]) for 1-SD increase in PI (p = 0.03; Table 5).

Table 5.

Results from Logistic regression models (adjusted for age and sex).

| Outcomea | Predictor | OR (CI 95%)* | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| FIB | α1 | 2.68 (1.43, 5.78) | 0.001 |

| FIB | PI | 0.48 (0.24, 0.86) | 0.01 |

| FIB | PermEn | 1.79 (1.02, 3.32) | 0.04 |

| CEA | PermEn | 1.62 (0.91, 3.03) | 0.1 |

| CEA | DistEn | 0.61 (0.33, 1.06) | 0.07 |

| CA199 | GI | 0.45 (0.17, 1.06) | 0.07 |

| CEA | PI | 0.64 (0.35, 1.14) | 0.1 |

| CA199 | PI | 0.53 (0.27, 0.95) | 0.03 |

| FIB | FuzzyEn | 0.62 (0.34, 1.08) | 0.09 |

Results presented in the same order as in Table 3. Bold p values indicate statistically significant at alpha = 0.05 level.

*Effects for 1-standard deviation increase in the predictor adjusted for covariates.

aOutcomes are each dichotomized with a threshold value: 3.5 for FIB, 5 for CEA, and 37 for CA199.

Abbreviations: CA199 = carbohydrate antigen 19-9; CEA = carcinoembryonic antigen; CI = confidence interval; DistEn = distribution entropy; FIB = fibrinogen; FuzzyEn = fuzzy entropy; GI = Guzik’s index; PermEn = permutation entropy; OR = odds ratio; PI = Porta’s index.

Discussion

With 61 pathologically-diagnosed GC patients in this pilot study, for the first time we demonstrated significant associations between clinical cancer markers and several nonlinear HRV measures after accounting for multiple comparisons. Specifically, the increase of short-range temporal correlations in heartbeat fluctuations (i.e., increase in α1 which was calculated within time scales 4–16 beats), the decrease of the asymmetry in heartbeat acceleration/deceleration patterns (i.e., PI), and the increase of the irregularity of heartbeat fluctuations (i.e., PermEn) were associated with higher serum FIB level. The increase in PermEn as well as the decrease of the complexity of heartbeat dynamics (i.e., DistEn) were also associated with higher serum CEA level. Importantly, these associations were independent of several potential confounding factors including age, sex, BMI, alcohol consumption, history of diabetes, Hb, and LVEF.

Nonlinear HRV measures as markers of autonomic nervous function modulating tumor progression

The autonomic nervous function is an accepted component involved in cancer etiology22. There is mounting evidence supporting the vagal neuromodulation hypothesis in tumorigenesis through its effects of anti-inflammation, antioxidative stress, and sympathetic activity2,3,23 including animal studies24–26 that demonstrated a causal pathway.

Through the analysis of vagal and sympathetic modulation on heartbeat, HRV is a well-known and widely-applied noninvasive tool for assessing the autonomic nervous function. Increased HRV has consistently been associated to better prognosis in cancer patients7,8,22,27–30. There is also an increasing preference in the biomedical science/engineering communities of using nonlinear analysis approaches as complements to the traditional linear methods. Coming from the fields of statistical physics and nonlinear dynamics, these nonlinear approaches could uniquely capture the information content (i.e., entropy-based measures), asymmetry, or scaling invariant properties (i.e., DFA), all of which has been shown to offer additional, valuable knowledge to the underlying control mechanism, i.e., the autonomic regulation12,31–35.

Nonlinear HRV measures for the organisms’ plasticity and adaptability coping with stress

Although being not immediately interpretable with regards to the vagal or sympathetic regulation, there are published pilot studies that have already explored the effects of vagal and sympathetic outflows on several nonlinear measures of heartbeat dynamics including entropy measures and DFA scaling exponents36,37. Using both human and animal models, they have offered the direct evidence of autonomic control influencing the complex behavior of the heart.

A more traditional or systemic level viewpoint is that the nonlinear behavior of HRV is attributed to the competing regulation on the heart coming from the two branches of the autonomic nervous system and the spontaneity of the organism itself. Such competition renders healthy organisms high complexity, enabling daunting plasticity and adaptability to the stresses/perturbations of everyday life38,39. In parallel with this complex physiology hypothesis, aging and disease progressions are usually accompanied by a progressive reduction of the complexity12,34,38,40; and the other way around the degradation of the complexity also predicts future incidence of disease41.

In keeping with the complexity loss theory, our results suggest that GC patients with worse prognosis showed lower autonomic control complexity even though each different nonlinear metric showed different changing directions. Theoretically, the most complex system should be neither too random nor too regular; it should correspond to a critical point in-between42. The departure of α1 from the value 1, whichever direction, both imply a reduced complexity43. In our case, it was a reduction towards the regular side (i.e., increase of α1 towards 1.5). The decrease of PI indicates a loss of time irreversibility, an important property of complex system which suggests an evolution of the system to equilibrium or a loss of hysteresis44. The increase of PermEn indicates higher irregularity which suggests a seemingly controversial behavior as compared with α1. However, the calculation of PermEn focused on the fluctuation motifs composed of 3 heart beats that were not included in the calculation of α1 for sake of a robust fitting. The decrease of DistEn, although it is in nature an entropy metric, directly suggests a decrease in complexity as evidenced by the simulation analysis in the original DistEn study45.

Potential clinical relevance and usefulness

With the rising of global GC epidemic, the assessment of HRV may potentially meet the clinical urgency in three ways:

HRV analysis may offer a sensitive and noninvasive tool targeting an early GC diagnosis. On one hand, the nonlinear approaches used in this study are necessary in the way that they cope well with the nonlinear and nonstationary nature, resulting thus in a more robust assessment as compared with the existing linear methods. On the other hand, it might be possible to leverage these nonlinear indices with the existing linear measures to construct an integrated biomarker for early GC diagnosis. Further studies with larger samples are required to test this hypothesis.

HRV could help with the evaluation of prognosis and treatment planning for GC patients. The link between HRV and survival time suggests a role of HRV in helping screen the general health status and prognosis of cancer patients8,29,30. Previous studies also discovered a link between serum FIB and adjacent organ involvement18. Given the strong associations of serum FIB with HRV nonlinear indices reported in the current study, HRV analysis may thrive as a sensitive tool for the surgical planning of GC patients. Further clinicopathological studies are warranted to formally examine their associations.

HRV might be a target for interventions to prevent the disease or to slow down the progression. Although only cross-sectional associations were reported in this current study, previous animal studies have established a causal link between vagal activity and tumor genesis24–26. A case-control study that focuses on exposure to interventions improving HRV especially in terms of nonlinear properties is required to validate this causal pathway in humans.

Study limitations

There are several notable limitations. First, the sample size is relatively small. Aside from the four indices (i.e., α1, PI, PermEn, DistEn) the other nonlinear HRV measures may also be correlated with the serum markers while their negative observations may simply be due to the power issue. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the study design limits our inference about longitudinal prediction ability of HRV nonlinear measures. It is of great clinical value to examine whether those presurgical HRV indices can predict longer term outcomes including treatment response and survival. Besides, it is also meaningful to check whether degradations of these nonlinear properties in otherwise normal people predict higher risk of developing GC later. Third, although the FIB, CEA, and CA199 are well developed serum markers of cancer severity or prognosis, the gold standard is pathological examination. We are still working to retrieve and pool detailed pathology data together in addition to the final diagnosis and are expecting to scrutinize their interrelationships with HRV nonlinear features in follow-up studies.

Materials and Methods

Patients and data collection

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical College and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. From March 2018 to December 2018, 126 patients were diagnosed with GC based on endoscopy and pathological examinations in The First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical College. Among them, 90 patients provided written informed consent and were enrolled in this study.

Serum FIB, CEA, and CA199 levels were examined before breakfast 1-week before surgical treatments. FIB levels were determined using the Clauss method (Sysmex CS51000, Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan). Chemiluminescent assays were used to determine the CEA and CA199 levels (Architect i2000sr, Abbott Diagnostics, Abbott Park, IL, USA). ECG data were recorded continuously for 5 min one day before treatments with patients lying down for at least 20 min before the formal collection (HeaLink-R211B, HeaLink Ltd., Bengbu, China). The sampling frequency of ECG collection was 400 Hz. The precordial V5 lead was configured and the Ag/AgCl disposable electrodes were used (Junkang Ltd., Shanghai, China).

We further excluded participants with the following conditions: (1) recurrent GC (N = 1), (2) poor ECG quality (N = 2), (3) presence of ectopic beats (>10% of all beats; N = 8), or (4) administering of blood transfusion (N = 15) or chemotherapy (N = 3) prior to ECG collection. Therefore, data of 61 participants were presented and analyzed in this current study. Their demographics and clinical characteristics were shown in Table 1.

Nonlinear HRV analysis

R-wave peaks were located automatically using a template-matching approach46 followed by visual inspections. Ectopic beats were identified manually during the visual inspection (1–3 ectopic beats, either premature atrial contraction or premature ventricular contraction, presented in 14 out of the 61 patients). The final HRV time-series were constructed for each patient by consecutive normal sinus R-R intervals. The normal to ectopic or ectopic to normal intervals were discarded and the corresponding two segments were stitched together to assure a reasonable length of the RR interval time-series. Figure 1 shows examples of the construction of RR interval time-series without and with ectopic beats.

For each RR interval time-series, 12 nonlinear HRV indices covering the irregularity, complexity, asymmetry, and temporal correlation of heartbeat fluctuations were calculated. The 12 indices included (1) six entropy-based measures: approximate entropy (ApEn), sample entropy (SampEn), fuzzy entropy (FuzzyEn), permutation entropy (PermEn), conditional entropy (CE), distribution entropy (DistEn); (2) four asymmetry indices: Porta’s index (PI), Guzik’s index (GI), slope index (SI), area index (AI); and (3) two detrended fluctuation analysis (DFA) derived metrics α1 and α2. The detail algorithms for calculating these indices were summarized in Supplemental Methods documented in the online Supplemental Materials.

The extraction of R-peaks, visual inspections of ectopic beats, and asymmetry analysis were done in MATLAB (Ver. R2018a, The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, US). Entropy analysis was performed using the EZ Entropy software47. The Kubios HRV software was used to perform the DFA48.

Statistical analysis

Histograms of CEA and CA199 both showed an obvious right skewness; they were thus natural-log-transformed prior to further analysis (unless otherwise indicated). Bivariate Pearson correlations of FIB, CEA, and CA199 with each of the 12 nonlinear HRV measures were performed to screen potential predictors. Conservatively, features with p level of <0.1 were considered significant. Linear regressions were then performed for these pairs that passed this screening process with either FIB, CEA, or CA199 as an outcome. These models were adjusted for age and sex. To avoid collinearity, the HRV features were each included in a separate regression model as a predictor. To determine the statistical significance, the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure was used to control for false discovery rate (FDR) within multiple comparisons49. FDR-corrected p < 0.05 is considered statistically significant. These models were then augmented by further adjusting for BMI50, alcohol consumption51, history of diabetes52, LVEF53, and anemia as assessed by Hb54 followed by the same multiple comparison correction procedure. As an exploratory analysis, FIB, CEA, and CA199 were dichotomized each by a separate threshold value19: (1) FIB was considered high if >3.5 mg/mL and low if otherwise; (2) CEA was considered high if the original CEA level ≥ 5 and low if otherwise; and (3) CA199 was considered high if the original CA199 level ≥ 37 and low if otherwise. Logistic regression models were performed with each of the three dichotomized clinical parameters as an outcome and with each feature in the corresponding significant HRV feature set as a predictor while adjusted for age and sex. All statistical analyses were performed using the JMP Pro (ver. 14, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 61601263) and the Key Program on Natural Scientific Research from the Department of Education of Anhui Province, China (grant numbers KJ2018A1023 and KJ2018A1030).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.L. and B.S. Data collection: L.W., B.S., D.C. and M.L. Methodology, All. Formal analysis, P.L. Resources, D.C., M.L. and P.L. Writing—original draft preparation, P.L., B.S. and C.Y. Writing—review and editing, P.L. Supervision, P.L.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

A direct family member of B.S. owns stock in the HeaLink Ltd., Bengbu, China. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-50358-y.

References

- 1.Bray F, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gidron Y, Perry H, Glennie M. Does the vagus nerve inform the brain about preclinical tumours and modulate them? Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:245–248. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Couck M, Mravec B, Gidron Y. You may need the vagus nerve to understand pathophysiology and to treat diseases. Clinical Science. 2012;122:323–328. doi: 10.1042/CS20110299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berntson GG, et al. Heart rate variability: origins, methods, and interpretive caveats. Psychophysiology. 1997;34:623–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldberger J, et al. Relationship of Heart Rate Variability to Parasympathetic Effect. Circulation. 2001;103:1977–1983. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.103.15.1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Couck M, Gidron Y. Norms of vagal nerve activity, indexed by Heart Rate Variability, in cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37:737–741. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2013.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mouton C, et al. The relationship between heart rate variability and time-course of carcinoembryonic antigen in colorectal cancer. Autonomic Neuroscience. 2012;166:96–99. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kloter, E., Barrueto, K., Klein, S. D., Scholkmann, F. & Wolf, U. Heart Rate Variability as a Prognostic Factor for Cancer Survival – A Systematic Review. Front. Physiol. 9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Hu S, Lou J, Zhang Y, Chen P. Low heart rate variability relates to the progression of gastric cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2018;16:49. doi: 10.1186/s12957-018-1348-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andreas V, Steffen S, Rico S, Mathias B, Pere C. Methods derived from nonlinear dynamics for analysing heart rate variability. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 2009;367:277–296. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2008.0232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Godoy MF. de. Nonlinear Analysis of Heart Rate Variability: A Comprehensive Review. Journal of Cardiology and Therapy. 2016;3:528-533–533. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lipsitz LA. Age‐related changes in the ‘“complexity”’ of cardiovascular dynamics: A potential marker of vulnerability to disease. Chaos. 1995;5:102–109. doi: 10.1063/1.166091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huikuri HV, et al. Fractal correlation properties of R-R interval dynamics and mortality in patients with depressed left ventricular function after an acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2000;101:47–53. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.101.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mäkikallio TH, et al. Prediction of sudden cardiac death by fractal analysis of heart rate variability in elderly subjects. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001;37:1395–1402. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mäkikallio AM, et al. Heart rate dynamics predict poststroke mortality. Neurology. 2004;62:1822–1826. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000125190.10967.D5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stein PK, Domitrovich PP, Huikuri HV, Kleiger RE, Cast Investigators Traditional and nonlinear heart rate variability are each independently associated with mortality after myocardial infarction. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2005;16:13–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2005.04358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young H, Benton D. We should be using nonlinear indices when relating heart-rate dynamics to cognition and mood. Scientific Reports. 2015;5:16619. doi: 10.1038/srep16619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee SE, et al. Preoperative Plasma Fibrinogen Level Is a Useful Predictor of Adjacent Organ Involvement in Patients with Advanced Gastric Cancer. J Gastric Cancer. 2012;12:81–87. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2012.12.2.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu, X. et al. Serum fibrinogen levels are positively correlated with advanced tumor stage and poor survival in patients with gastric cancer undergoing gastrectomy: a large cohort retrospective study. BMC Cancer16 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Iwanicki-Caron I, et al. Usefulness of the serum carcinoembryonic antigen kinetic for chemotherapy monitoring in patients with unresectable metastasis of colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:3681–3686. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takahashi Y, et al. The usefulness of CEA and/or CA19-9 in monitoring for recurrence in gastric cancer patients: a prospective clinical study. Gastric Cancer. 2003;6:142–145. doi: 10.1007/s10120-003-0240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arab C, et al. Heart rate variability measure in breast cancer patients and survivors: A systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;68:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cole SW, Sood AK. Molecular Pathways: Beta-Adrenergic Signaling in Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:1201–1206. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erin N, Akdas Barkan G, Harms JF, Clawson GA. Vagotomy enhances experimental metastases of 4THMpc breast cancer cells and alters Substance P level. Regulatory Peptides. 2008;151:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melhem-Bertrandt A, et al. Beta-Blocker Use Is Associated With Improved Relapse-Free Survival in Patients With Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. JCO. 2011;29:2645–2652. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.4441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erin N, Duymuş Ö, Öztürk S, Demir N. Activation of vagus nerve by semapimod alters substance P levels and decreases breast cancer metastasis. Regulatory Peptides. 2012;179:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoffmann J, et al. Prognostic value of heart rate variability analysis in patients with carcinoid syndrome. Digestion. 2001;63:35–42. doi: 10.1159/000051870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiang J-K, Koo M, Kuo TBJ, Fu C-H. Association between cardiovascular autonomic functions and time to death in patients with terminal hepatocellular carcinoma. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:673–679. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fadul N, et al. The association between autonomic dysfunction and survival in male patients with advanced cancer: a preliminary report. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou X, et al. Heart rate variability in the prediction of survival in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2016;89:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peng CK, et al. Fractal mechanisms and heart rate dynamics. Long-range correlations and their breakdown with disease. J Electrocardiol. 1995;28(Suppl):59–65. doi: 10.1016/S0022-0736(95)80017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pincus SM. Approximate entropy in cardiology. Herzschr Elektrophys. 2000;11:139–150. doi: 10.1007/s003990070033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richman JS, Moorman JR. Physiological time-series analysis using approximate entropy and sample entropy. American Journal of Physiology - Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2000;278:H2039–H2049. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.6.H2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldberger AL, et al. Fractal dynamics in physiology: alterations with disease and aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99(Suppl 1):2466–2472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012579499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piskorski J, Guzik P. Compensatory properties of heart rate asymmetry. Journal of Electrocardiology. 2012;45:220–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castiglioni P, et al. Scale exponents of blood pressure and heart rate during autonomic blockade as assessed by detrended fluctuation analysis. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 2011;589:355–369. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.196428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silva LEV, Silva CAA, Salgado HC, Fazan R. The role of sympathetic and vagal cardiac control on complexity of heart rate dynamics. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2017;312:H469–H477. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00507.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldberger AL, Peng C-K, Lipsitz LA. What is physiologic complexity and how does it change with aging and disease? Neurobiol. Aging. 2002;23:23–26. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(01)00266-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lipsitz LA. Physiological complexity, aging, and the path to frailty. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ. 2004;2004:pe16. doi: 10.1126/sageke.2004.16.pe16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li, P. et al. Interaction between the progression of Alzheimer’s disease and fractal degradation. Neurobiology of Aging, 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.08.023 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Li P, et al. Fractal regulation and incident Alzheimer’s disease in elderly individuals. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:1114–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rickles D, Hawe P, Shiell A. A simple guide to chaos and complexity. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:933–937. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.054254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peng CK, et al. Mosaic organization of DNA nucleotides. Phys Rev E Stat Phys Plasmas Fluids Relat Interdiscip Topics. 1994;49:1685–1689. doi: 10.1103/physreve.49.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Costa MD, Peng C-K, Goldberger AL. Multiscale analysis of heart rate dynamics: entropy and time irreversibility measures. Cardiovasc Eng. 2008;8:88–93. doi: 10.1007/s10558-007-9049-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li P, et al. Assessing the complexity of short-term heartbeat interval series by distribution entropy. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2015;53:77–87. doi: 10.1007/s11517-014-1216-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li P, Liu C, Zhang M, Che W, Li J. A real-time QRS complex detection method. Acta Biophys Sin. 2011;27:222–230. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1260.2011.00222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li P. EZ Entropy: a software application for the entropy analysis of physiological time-series. BioMedical Engineering OnLine. 2019;18:30. doi: 10.1186/s12938-019-0650-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tarvainen MP, Niskanen J-P, Lipponen JA, Ranta-aho PO, Karjalainen PA. Kubios HRV – Heart rate variability analysis software. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine. 2014;113:210–220. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2013.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McDonald, J. H. Handbook of biological statistics. (Sparky House Publishing).

- 50.Lee JH, et al. Body mass index and mortality in patients with gastric cancer: a large cohort study. Gastric Cancer. 2018;21:913–924. doi: 10.1007/s10120-018-0818-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ma K, Baloch Z, He T-T, Xia X. Alcohol Consumption and Gastric Cancer Risk: A Meta-Analysis. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:238–246. doi: 10.12659/MSM.899423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miao Z-F, et al. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of gastric cancer: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Oncotarget. 2017;8:44881–44892. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Said R, et al. The prognostic significance of left ventricular ejection fraction in patients with advanced cancer treated in phase I clinical trials. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:276–282. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zamchegk N, Grable E, Ley A, Norman L. Occurrence of Gastric Cancer among Patients with Pernicious Anemia at the Boston City Hospital. New England Journal of Medicine. 1955;252:1103–1110. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195506302522601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.